Abstract

Dr. James Knight's death in 1887 resulted in a change of course for the Hospital for the Ruptured and Crippled (renamed the Hospital for Special Surgery in 1940). The Board of Managers appointed Dr. Virgil Pendleton Gibney as the second Surgeon-in-Chief. The hospital's professional staff was expanded with introduction of surgical procedures. Gibney, raised in Kentucky, was trained under Lewis H. Sayre, M.D., a prominent orthopaedic surgeon at Bellevue Hospital. Dr. Gibney introduced the first residency training, expanded the physical plant, and continued to care for the disabled children in the hospital while maintaining a private practice outside the hospital. He was one of the founding members of the American Orthopaedic Association and served as its first president. He was the only member ever to serve as president twice, the second time in 1912.

Key words: Hospital for the Ruptured and Crippled, Hospital for Special Surgery, William T. Bull, William Bradley Coley, Virgil P. Gibney, John Ridlon, James Knight, Newton M. Shaffer

Introduction

With the death of the founder and first Surgeon-in-Chief, James Knight, in October 1887, the Hospital for the Ruptured and Crippled (R&C) took on a new and expanding course when the Board of Managers appointed Virgil Pendleton Gibney as their second Surgeon-in-Chief. The first 24 years of the hospital's origin and development have previously been described in my earlier published reports [1, 2]. Although Gibney was named the second Surgeon-in-Chief, for all practical purposes he was truly the first surgeon to hold this title for Knight was not a surgeon. Trained at Bellevue Medical College, under Dr. Lewis A. Sayre, the first Professor of Orthopaedic Surgery in this country, Gibney introduced surgical treatment for the first time at the Ruptured and Crippled.

Born and raised in Kentucky

Virgil Pendleton Gibney was born September 29, 1847 on a farm in Jassamine County, KY, the elder son of a general practitioner, Robert A Gibney, M.D. (Fig. 1) and his second wife Amanda Weagley. His first wife, Pamela Pendleton, after 3 years of marriage, had died along with Virgil Gibney's baby brother. The two women had been very good friends, and Virgil Gibney's middle name was taken from Pamela Pendleton. While there is no record why he was named Virgil, a youngest brother was named Homer.

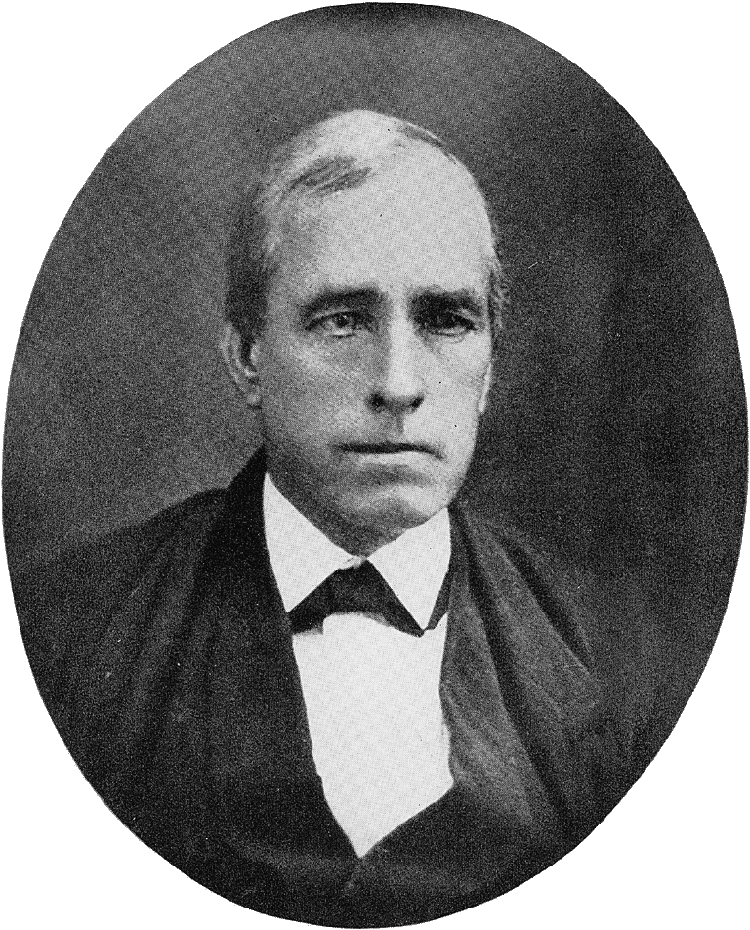

Fig 1.

Robert A. Gibney, M.D. (1816–1874), father of Virgil P. Gibney, M.D.

Much of Virgil Gibney's personal life was recalled by his loving son Robert A. Gibney in a book published in 1969 and edited by Alfred R. Shands, Jr., M.D., Medical Director of the Alfred I. Dupont Institute for Crippled Children in Wilmington, DE. Dr. Shands' father, Alfred R. Shands, M.D., had trained under Gibney at R&C from 1892 to 1894 and was a good friend of his.

As described in the forward by Dr. Philip D. Wilson, the book was to be distributed to all graduates of the hospital's training program. Dr. Wilson called upon Dr. T. Campbell Thompson, a former Surgeon-in-Chief, and Dr. Robert Lee Patterson, Jr., the then current Surgeon-in-Chief, to help find funding for this publication [3].

Virgil Gibney had lost his ring and little finger of his right hand in 1858 when he was 11 years old, supposedly in an accident in Nicholasville, KY. This did not stop him from proceeding to study surgery, eventually to become a great surgeon in this country. He was a student of Latin, Greek, and German, but was less talented in mathematics. Consequently, in later years he relied on others to manage his business affairs and investments.

Gibney's father immigrated from the north of Ireland in the eighteenth century. As a physician, Dr. Robert A. Gibney needed to supplement his income, which he did by owning part of a retail store. He rented a small house on 5 acres of a farm belonging to James H. McCampbell. His rent was providing medical care for the McCampbell family.

In 1860, the Gibneys bought a 200-acre farm for $110 per acre11 near Lexington. It was reported to be a nice piece of land, well located with a pond. It was the time of the Civil War and while Robert A. Gibney was a staunch Unionist, his son, Virgil, was a young rebel, too young to enlist.

The story told was when Morgan's Raiders came riding through, they heard of father Gibney's Union favoritism, and they would raid the farm. Likewise, when a troop of Illinois or Ohio cavalry came storming through, they heard of Virgil's rebel sympathies and also raided the farm. A cloud of horsemen along the path would always mean trouble whether the uniforms were blue or gray.

The farmhouse was eventually burned and the family moved into the slave quarters. When that, too, was burned, they moved into empty chicken houses, finally moving to Lexington. As a result, the young Gibney was eager to move from a farm and never ever return.

In 1869, Gibney obtained his A.B. degree from Kentucky University22 in Lexington. The first year of his medical education was at Louisville University, after which he studied at Bellevue Medical College, receiving his M.D. degree in 1871.

Appointed to R&C staff

Virgil Gibney's first appointment after medical school was Assistant Physician and Surgeon at R&C. It was just a year after the hospital had moved from its first site, James Knight's residence on Second Avenue, into its new 200-bed building located on the corner of Lexington Avenue and 42nd Street. Gibney was to live in the hospital for the next 13 years as assistant to Knight [3].

In 1878, Dr. Knight's title was changed from Resident Physician Surgeon to Surgeon-in-Chief, whereas Gibney's title as Assistant Physician and Surgeon became House Surgeon.

Dr. Knight held Gibney in great trust. In 1874, Knight wrote to the Board of Managers: “It is with pleasure I inform you of the very able assistance that has been rendered by my senior assistant, V.P. Gibney by his indefatigable attention to Hospital duties and scientific researches into the pathological conditions of patients, and especially to microscopical investigations.”

Dr. Knight was becoming fatigued, and in 1878 at the age of 68 he took a few months off to regain his health. He turned over the leadership of the hospital to Dr. Gibney. Knight spent time in Europe, visiting hospitals similar to his but seemed unimpressed of what he saw and returned with no new ideas or treatment methods.

Earlier in the history of the R&C, school classes in the hospital had been established by the Board of Education after Dr. Knight insisted that his inpatients needed daily learning in books, religion, and morals. Among the regular teachers employed was a Charlotte L. Chapin from Springfield, MA. Her mother and father had died when she was 6 years old, and she went to live with her aunt eventually attending Mount Holyoke Female Seminary where another aunt had been principal and from where her mother had graduated.

After 2 years at Mt. Holyoke, Charlotte Chapin left college and moved to New York where she accepted a position as a schoolteacher at R&C. There she met the young, handsome surgeon, Virgil Gibney, and the two were married in 1883. Unfortunately, in 1889 a tragedy in Gibney's life occurred when both his wife and older son died of diphtheria. A second son from this marriage, Robert A. Gibney, the collector of his father's history for this book, had been born only a month prior to this unfortunate event. (Strangely, Gibney's father's first wife had also died 3 years after their marriage [3].)

Four years later, Virgil Gibney at age 46, married for the second time, 24-year-old Julia A. Trubee of Bridgeport, CT. This marriage produced two daughters.

At Ruptured and Crippled, Gibney studied over 2,000 cases of tuberculosis of the hip, all treated by expectant treatment as prescribed by Dr. Knight. Gibney was an excellent observer and took voluminous notes. He formulated his own approach to treating this condition. He advocated traction for mild cases and surgery for advanced cases. He never discussed these principles with his chief. Although very respectful of Knight and his conservative approach to treating patients, Gibney published a book on tuberculosis of the hip advocating surgery. James Knight discovered this publication and was astonished by its recommendations. Abruptly, in 1884, he asked for Dr. Gibney's resignation [4].

Establishing a private practice

When Gibney left the Hospital for the Ruptured and Crippled in 1884, he established a private practice and opened an office in his home at 23 Park Avenue, seeing his first private patient February 3, 1884. For the next 3 years, he had no formal association with R&C, but the Board of Managers was so fond of him that they often would ask him his opinion on hospital matters. Gibney referred to this period from 1884 to 1887 as the Inter-regnum [2].

His daily routine was to have morning office hours with his secretary taking notes and making outside visits in the afternoon. He had a phenomenal memory for names of his patients and kept careful notes on them. In his biography, his son, Robert A. Gibney, wrote: “For years he carried a bright red leather cover into which was fitted his current memorandum book, changed every month and then filed. When he was unoccupied, he had a habit of taking out this memo book for reference as he thought things over, irrespective where he happened to be at the time. My stepmother, with long experience, was particularly careful when she and my father were in church, and she sensed he was losing interest in the sermon. She would build up 4 or 5 hymnals and prayer books on the pew between them, and when the memo book had come out, and he would start to raise it to the level of his eyes, she would topple over the books against his leg. He understood the message, and with an apologetic shake of his head the memo book would go back into his pocket, and his attention turn again to the sermon” [3].

James Knight's health was failing, and he died on October 24, 1887. The Board immediately contacted Gibney to offer him the position of Surgeon-in-Chief. Dr. Gibney was visiting surgical clinics in England and Scotland with his wife and son when he received the wire from a Board member, Cornelius Vanderbilt, informing him of Knight's death and asking him to take charge of the hospital.

Gibney's European visit was very rewarding as he met a number of notable surgeons. He made rounds with Hugh Owen Thomas (1834–1891) of Liverpool and became intimately acquainted with him at as his home. Gibney also got to know his nephew, Sir Robert Jones (1857–1933), who was to become the most famous orthopaedic surgeon in England.

Second Surgeon-in-Chief

With the appointment of the new Surgeon-in-Chief (Fig. 2), major changes followed. Gibney established that the Surgeon-in-Chief's residence would move out of the hospital. His assistants would continue to live inside the hospital.

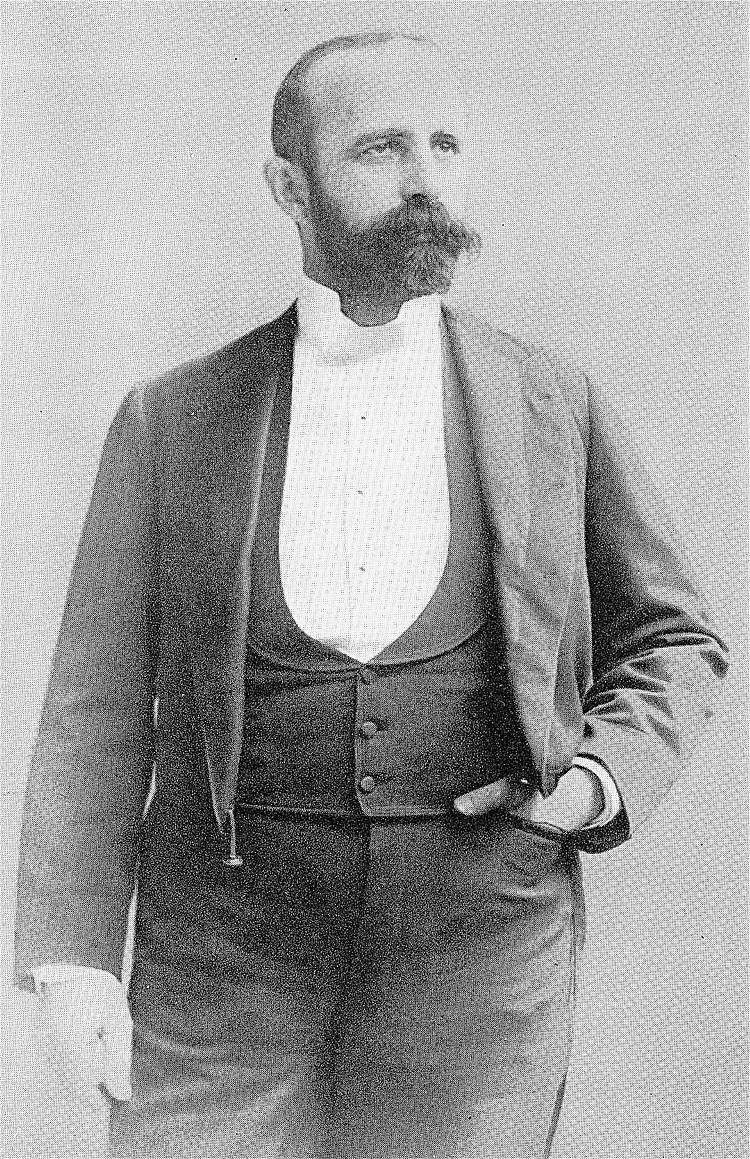

Fig 2.

Virgil Pendleton Gibney, M.D., at age 40 in 1887 when he became Surgeon-in-Chief

In 1888, he created the house staff as we know it today. Young doctors in training would apply for a 1-year position as House Surgeon, Senior Assistant, and Junior Assistant. They became known as residents, a term now universally recognized in this country as a doctor in training. The term resident doctor was probably used for the first time in this country at R&C.

Candidates for these positions were required to be graduates in medicine. Depending on their hospital experience, they were assigned to different positions. The Junior Assistant was appointed January, May, and September. He served 4 months as Junior, 4 months as Senior, and 4 months as House Surgeon. This procedural tract persisted into the 1960s. When I was a resident in 1961, a new resident was appointed in January, April, June, and September for a period of 3 and 1/2 years after 1 year of internship and 1 year of surgical residency. It was unique to the Hospital for Special Surgery and a few other training programs.

The house staff assisted both the orthopaedic and hernia surgical staff (to be described).

Hospital Fire

In January 1888, a young girl who had been an inpatient for 2 years and obsessed with fire, succeeded in setting fire to the northwest wing of the hospital. All 120 children were safely relocated to the Vanderbilt Hotel, where they were received free of charge. Seven others were taken into private homes. Unfortunately, there was one fatality. The cook, Mary Donnelly, suffocated in her room [5].

Although insurance covered the extensive damages, the Board of Managers decided to bring hospital facilities up-to-date, and expand the ward capacity and the outpatient facilities. It annexed the original building expanding to 43rd Street. Included was the introduction of the first operating room in the hospital that met the requirements of antiseptic surgery in those days.

Department of Hernia

Gibney realized the importance of separating patients with hernia conditions from orthopaedic problems. He gave his reasons as follows: “With a house staff which, of necessity, must change, it is difficult to command the kind of skill necessary for the treatment of hernia, even from a mechanical standpoint. However simple, it may seem to apply a truss, it must be remembered that there are many cases present where a truss should not be applied. I must congratulate the Board, therefore, on having secured the services of Dr. William T. Bull as Attending Surgeon to the Department of Hernia.”

William Tillinghouse Bull, M.D. (1849–1909), an 1869 graduate of Harvard who received his MD degree from New York College of Physician and Surgeons in 1872, was one of the first in this country to devote himself entirely to surgery. He joined the surgical staff of the New York Hospital in 1883 and became renown in surgical techniques. In 1884 he was said to be the first to perform an emergency exploratory operation for an abominable gunshot wound. He was a close colleague of Dr. Gibney, who shared a private office with him.

Gibney's visit to Edinburgh and Glasgow was particularly eye opening as he was exposed to the antiseptic techniques introduced by Lister in 1866. Such principles were slow to be accepted in America. Now that he was in charge of his own hospital with surgical patients, he needed advice and expertise in the field of surgery. Thus, Dr. Bull was an excellent choice to advise and direct the hospital's surgical service. Even though Gibney represented the progressive group promoting surgery in contrast to others of the conservative group, his own qualifications hardly would have qualified him as an expert surgeon.

Orthopaedic Department established

Dr. Gibney created a separate orthopaedic staff, appointing Dr. Wisner R. Townsend Assistant Surgeon with six clinical assistants in the Outpatient Department.

Royal Whitman

In 1889, Dr. Royal Whitman (1857–1946) was appointed Assistant Surgeon of the Outpatient Department. Whitman, a graduate of Harvard Medical School in 1882, served a surgical internship at Boston City Hospital and had further training in England. He was author of one of the most comprehensive orthopaedic text books in English history, A Treatise on Orthopaedic Surgery, first published in 1901 and revised six times with the seventh edition published in 1923 [6]. He was an accomplished surgeon whose knowledge of anatomy, meticulous technique, and carefully planned operations led to excellent results with rare infections.

As a teacher, Dr. Whitman expected his house staff to be well read on the subject; otherwise, he could be harsh and critical. He was likewise harsh on visitors, but his motives were not malicious—he only strove to stimulate knowledge in the field of orthopaedics. He did the most to foster surgical treatment in contrast to the conservative approach of James Knight and others [the American Orthopaedic Association (AOA), founded in 1887, encouraged this change in attitude]. Samuel Kleinberg [7] (1885–1957) considered him to be “the most accomplished orthopaedic surgeon of his day in our country.” Kleinberg had studied scoliosis under Whitman at R&C, joining its staff until Whitman's retirement in 1929. Dr. Kleinberg then became affiliated with the Hospital for Joint Diseases.

William Bradley Coley

William Bradly Coley, M.D. (1862–1936) was appointed Clinical Assistant to the Hernia Clinic in 1889 just 1 year after graduating Harvard Medical School. He had studied at the New York Hospital under Dr. Bull, who considered him to be a unique physician. At that time, the New York Hospital was located on 16th Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues.

Coley's career at Ruptured and Crippled spanned 40 years, including appointment as the third Surgeon-in-Chief in 1925. During his early career, Dr. Coley treated a young patient, Bessie Dashiell, who had injured her hand between the seats of a train in 1889. Dashiell had befriended John D. Rockefeller, Jr., in his youth. The management of the hand injury became challenging with persistent pain for the young lady. Coley performed surgery, and pathological examination diagnosed a sarcoma. The patient died of her malignancy.

Rockefeller had been very supportive of young Bessie Dashiell, through which he had met Dr. Coley. From treating this young patient, Coley started studying tumors, eventually leading to uncover a new treatment for cancer (to become known as Coley's toxins). With Rockefeller, Dr. Coley collaborated in the founding of the Rockefeller Institute and Memorial Sloan Kettering Hospital. It is a fascinating story described by the medical historian Stephen S. Hall [8].

The Board recognized in Gibney an accomplished physician with excellent administrative skills and the wisdom to be able to choose outstanding staff to work with him.

Founding of the American Orthopaedic Association

The AOA, the prestigious organization of the leaders of orthopaedic surgery in this country, was founded in New York in 1887. Depending on various sources, the preliminary meetings of organization differ. As written by Dr. John Ridlon (1852–1936) and published in 1918 as “The Beginnings of the Transactions and Journal of the American Orthopaedic Association,” he quoted Dr. Virgil Gibney, the first President of the AOA as follows: “My memory is that the late Dr. Steele, of St. Louis (Aaron J. Steele, 1835–1917), and Dr. Shaffer, of this city, met at my house, 23 Park Avenue, and we organized the association. Dr. Steele was the prime mover, and the one who suggested the necessity for such an organization. I was chosen the first president” [9].

Newton Melman Shaffer (1846–1928), trained by James Knight and on staff at R&C until 1870, was appointed chief of the orthopaedic service at St. Luke's Hospital in 1872, the first orthopaedic service in a general hospital. He became the second surgeon-in-chief of the New York Orthopaedic Dispensary and Hospital (founded in 1866) in 1876, succeeding Dr. Charles Fayette Taylor (1827–1899). In 1900, Shaffer became the first Professor of Orthopaedic Surgery at Cornell Medical College. He was a proponent of the conservative group and would often become adversely involved with Dr. Gibney at medical meetings.

In 1880, Dr. Shaffer appointed Dr. John Ridlon as his assistant in orthopaedics at St. Luke's Hospital. Ridlon, born in Vermont, had earned his M.D. degree from the College of Physicians and Surgeons in 1878. He was one of the first doctors in this country to be attracted to the work of Hugh Owen Thomas, whom he visited in Liverpool in 1887 when he was 35 years old. When he returned to St. Luke's Hospital, he introduced the first Thomas splint to be applied for tuberculosis of the hip. Shaffer ordered the splint removed, but Ridlon refused. At the end of the year Shaffer prevented Ridlon's reappointment to the staff of St. Luke's. In 1889 Dr. Ridlon left New York for Chicago, where he became Professor of Orthopaedic Surgery at Northwestern University in 1890. He served as President of the AOA in 1895 [10].

Dr. Gibney served a second time as AOA President in 1912, the only person ever to serve twice in that position. Dr. Royal Whitman was elected AOA President in 1896 and relished his membership in the AOA. He was also inducted as an honorary fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons and Royal Medical Society. In 1899, Dr. Wisner Townsend served as president of the AOA.

Tragedy and expansion

Gibney continued to maintain a private practice and bought a brownstone in 1888 at 16 Park Avenue across the street from his previous residence. On the first floor was his office, which he shared with Dr. Townsend and at various times with other colleagues and even his two brothers, who were also practicing physicians (Fig. 3).

Fig 3.

Virgil P. Gibney (right) and Wisner Townsend in the Gibney dining room at 16 Park Avenue in 1895

It was in May 1889 that Gibney suffered the tragic loss of his first son and, 5 days later, his wife from diphtheria. His second son, Robert A. Gibney, was only 6 weeks old. It was about the time that the hospital was annexed with the new five-story building. The addition almost doubled the floor space with an operating suite on the fifth floor, additional wards for the children, an isolation room, gymnasium, and mortuary (Fig. 4).

Fig 4.

The addition to the Hospital for the Ruptured and Crippled, a five-story building on Lexington Avenue and 43rd Street was connected to the old building along the front of the avenue by a low structure (left) serving as the new outpatient department that opened in 1898

The office of Superintendent was created in 1898 with Mr. Sherman H. Le Roy filling this new position and relieving Dr. Gibney of many administrative duties. This office did not become a full-time position until 1902, when it was separated from the duties of the surgeon-in-chief.

Two neurologists were appointed and Dr. Walter Truslow took on the task of treating scoliosis. In 1899, a pathology laboratory was opened and the first x-ray machine was installed. With all these improvements in facilities, the annual number admissions to the wards nearly doubled and expenses rose proportionally. There were only enough inpatient beds for children, and no available funding for inpatient adults at this time. The number of surgical procedures rose significantly. In 1894, Dr. Gibney was appointed the first Professor of Orthopaedic Surgery at the College of Physicians and Surgeons.

Medicine in contrast

With the changes introduced by the second Surgeon-in-Chief, the increased number of patients being treated in the outpatient department increased significantly, and long waiting lists resulted. Bed capacity was always full but inpatients were all children with no limitation on length of stay. They were only discharged when they got better. In 1894 Gibney reported to the Board of Managers: “We are obliged to retain a child in the Hospital from two to five years, in order that little details of management can be attended to” [3]. To relieve this strain, children were moved to summer homes whenever possible. In 1892 Gibney made his plea to the Board that the Hospital have its own summer home. The Board was sympathetic to these suggestions, but did not have the funds to do this.

Even when the new addition on 43rd Street was completed, no adult patient beds were provided because of lack of funds; besides, there were no accommodations for private patients.

Gibney and the physicians on staff continued treating private wealthy patients outside of the hospital. If they were outpatients, they would be examined in the physicians' private offices. If they needed to be admitted, Gibney and other physicians had established small private hospitals to fill this void. Together with Dr. Bull and Dr. John T. Walker, Gibney took over six houses on East 33rd Street between Madison and Park, where they established a Private Hospital Association equipped for medical and surgical care.

The wealthy in New York were treated differently from the indigent. Gibney had no reservations in charging the wealthy a healthy fee for his services; however, he was known to have high morals and excellent medical ethics.

The country in contrast

Not too far up the road from the tenements of Mulberry and Hester Streets were the mansions of Fifth Avenue above 59th Street facing Central Park. Cornelius Vanderbilt lived in a large home on the corner of 57th Street. Mrs. John Jacob Astor had given a ball where only invitations for 400 were sent. It was she who decided that there were only 400 eligible in the social register who should be invited (the origin of the Four Hundred) [11].

Immigrants flooded this country with over 2 million arriving between 1885 and 1895 (25 million between 1866 and 1915). Large groups of Italians and Jews settled in the lower East Side. There were many from other countries including England, Russia, Poland, Germany, and Scandinavia. At one time there were more Irish in New York City than in Ireland. Poverty, unemployment, and disease were rampant. Tenement slums took on the names of Hell's Kitchen or Poverty Gap. However, from these destitute areas came many who were eventually successful and even famous. One of these was Alfred E. Smith, four times Governor of New York and presidential candidate in 1928.

Parts of New York were festering sources of disease and deplorable public health conditions. Milk was sold from cows in the city never to leave their stalls. Chalk was used to whiten the product.

Jacob Riis, a police reporter for the New York Tribune wrote about slum life in New York in his famous book, How the Other Half Lives. “All the fresh air that enters these stairs comes from the hall door that is forever slamming.... The sinks are in the hallway, that all tenants may have access—and all be poisoned alike by the summer stenches...” [12].33

In stark contrast, manufacturing in this country rose over 600% in the latter part of the nineteenth century. The growth of the railroad system was unbelievable with over 100,000 miles of track being laid from 1870 to 1890. In the latter year, freight revenues totaled $1 billion, more than twice the annual revenue of our government. Steel, originally expensive and rare, was produced at the rate of 4 million tons/year in 1890 as a result of a new cost-effective process in refining it from iron ore. Andrew Carnegie made 70% of the country's steel in his Pittsburgh plants. In 1870, John D. Rockefeller from Cleveland merged five oil companies he owned into the Standard Oil Company. He controlled 90% of refineries in 1892. Known to be a ruthless but brilliant businessman, he drove up the price of oil by buying out his competitors. He was said to have been worth $800 million by 1892.44 Such accumulation of money by a few, promoted fraud, political graft, and crime. But also this was the land of opportunity. In 1879, Frank W. Woolworth opened the great first 5-cent store in Utica, NY. By 1913, he had accumulated enough wealth to build the Woolworth Building in New York, the tallest building in the world. Then there was Robert Cheesbrough, a young chemist from Brooklyn who in the 1870s invented petroleum jelly as a by-product of petroleum oil. He made much of it in his home, storing it in his wife's flower vases. From vase and line he coined the name Vaseline. In 1893 at the Chicago World's Fair, Whitcomb Judson, a Chicago inventor, exhibited the clasp locker, later to be called zipper by B.F. Goodrich who used it in overshoes.

As the Hospital for the Ruptured and Crippled entered the twentieth century, medicine was changing rapidly. The hospital kept pace in growth, development, and expansion with its new addition on East 43rd Street (Fig. 4), its first operating room (Fig. 5) and new wards (Fig. 6). R&C was financially secure under the able leadership of Virgil Pendleton Gibney and a supportive Board of Managers. It was ready to face the challenges of the 20th Century.

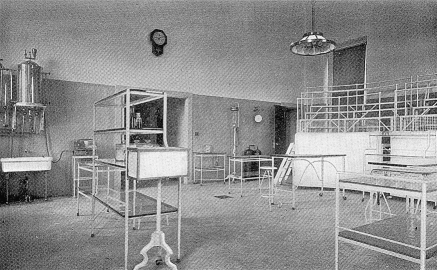

Fig 5.

This was the first operating room in R&C (1898)

Fig 6.

(1898) A new ward for children in the annex but no adult beds were provided in the hospital at this time

Footnotes

In today's dollars, $2,444.

The name was changed to Transylvania University (1799–1861) and then closed at the beginning of the Civil War.

Jacob Riis immigrated from Denmark in 1870 and was confronted with extreme poverty and unemployment until 1877, when he finally found a position in the New York Tribune. Along with other reformers, he brought about change for thousands of immigrants suffering from poverty and disease in New York. He continued his work through photography and became famous for his unique photojournalistic documentary approach for social reform. He died in 1914.

In today's dollars, $16.6 billion.

References

- 1.Levine DB (2005) Hospital for Special Surgery: Origin and early history. HSS J 1:3–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Levine DB (2006) The Hospital for the Ruptured and Crippled: Knight to Gibney. 1870–1887. HSS J 2:1–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Gibney RA (1969) In: Shands AF Jr. (ed) Gibney of the ruptured and crippled. Meredith Corporation, New York

- 4.Beekman F (1939) Hospital for the Ruptured and Crippled. A historical sketch written on the occasion of the seventy-fifth anniversary of the hospital. Privately printed, New York

- 5.Osborn WH (1888) Twenty-fifth annual report of the New York Society for the Relief of the Ruptured and Crippled. New York, pp 5–6

- 6.Wilson PD Jr., Levine DB (2000) Hospital for Special Surgery. A brief review of its development and current position. Clin Orthop 374:90–105 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Kleinberg S (1960) Royal Whitman (1857–1946). Orthopedics 1960:16:1–4 [PubMed]

- 8.Hall SS (1982) A Commotion in the blood, life, death and the immune system. Henry Holt, New York

- 9.Brown T (1987) The American Orthopaedic Association, A centennial history. AOA Publications, Boston

- 10.Orr HW (1949) On the contributions of Hugh Owen Thomas, Sir Robert Jones, John Ridlon to modern orthopaedic surgery. Charles C. Thomas, Springfield, IL

- 11.Lyman SL (1975) The story of New York. Crown Publishers, New York

- 12.Riis JA (reprinted 1997) How the other half lives. Penguin Group, New York