Abstract

Quadrilateral space syndrome (QSS) is a rare condition in which the posterior humeral circumflex artery and the axillary nerve are entrapped within the quadrilateral space. The main causes of the entrapment are abnormal fibrous bands and hypertrophy of the muscular boundaries. Many other space-occupying causes such as a glenoidal labral cyst or fracture hematoma have been reported in the literature. However, we could not find a report on classical QSS caused by an osteochondroma. The aim of this case report is to attract attention to an unusual etiology of shoulder pain, and to emphasize the importance of physical examination and x-ray imaging before performing more complex attempts for differential diagnosing.

Key words: quadrilateral space syndrome, osteochondroma, axillary nerve

Quadrilateral space syndrome (QSS) is a rare cause of shoulder pain in which the posterior humeral circumflex artery (PHCA) and the axillary nerve are entrapped within the anatomic space bounded by long head of triceps medially, proximal humerus laterally, teres minor superiorly, and teres major inferiorly [1]. Abnormal fibrous bands and hypertrophy of the muscular boundaries are the main etiological factors [2]. However, many conditions occupying the space in this area may cause QSS [1, 3, 4]. We represent a case with QSS caused by a humeral osteochondroma.

Case report

An 18-year-old girl with a complaint of left shoulder pain radiating to arm and forearm, which was present for about a year, and a complaint of hypoesthesia on lateral shoulder was admitted to our clinic. There was no history of trauma or sports activities involving the shoulder. She complained of a palpable, painless mass posterior to axilla. The pain worsened with abduction of the arm above 100° and diminished with rest. Physical examination revealed a 4 × 3 × 4 cm3 palpable mass on the posterior aspect of shoulder. There was no tenderness and the boundaries of the lesion were well defined. The mass was immobile with palpation. There was no pulsation or thrill with occultation. The muscle functions of the arm, forearm, and shoulder were normal. The peripheral pulses were maintained both on adduction and abduction of the shoulder. Shoulder range of motion was full. The Adson's maneuver was negative bilaterally. Blood pressure was 110/70 mm Hg on both arms at rest. The dynometric measurements (grip strength, lateral pinch, terminal pinch, and tripod grip) were normal when compared with the other side. On both hands, the Sammes Weinstein monofilament and two-point discrimination tests were normal, suggesting normal ulnar and median nerve functions.

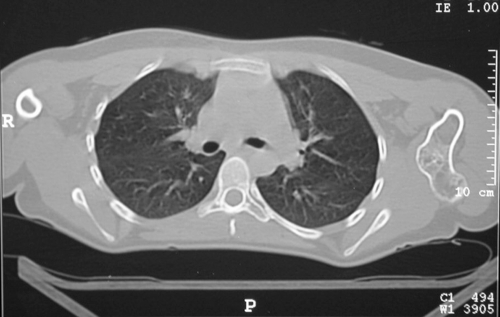

X-ray revealed an osteochondroma of the proximal humerus extending posteriorly (Fig. 1). Computed tomography (CT) revealed a broad-based, irregular osteochondroma extending to QS (Fig. 2). Electroneuromyogram (ENMG) of the left arm was normal.

Fig 1.

Preoperative anteroposterior humerus radiography demonstrating an osteochondroma

Fig 2.

Preoperative view of the lesion on computed tomography slices

On surgical intervention, a curved posterior shoulder incision extending posteriorly to the humerus was used. Posterior fibers of deltoid and teres minor were detached. The axillary nerve and the PHCA were exposed. The nerve was entrapped by teres major muscle, which was pushed up by the osteochondroma. This osteochondroma was removed with an osteotome and the QS was decompressed (Fig. 3). The arm was maintained in a shoulder sling postoperatively. The patient was pain-free at postoperative second day. Active pendulum shoulder exercises were begun at first postoperative week. The result of histopathological examination was reported as an osteochondroma. The patient was pain-free and the shoulder range of motion was full 6 weeks after the operation.

Fig 3.

Radiographic appearance of the humerus postoperatively

Discussion

QSS syndrome is an unusual cause of shoulder pain, caused by the entrapment of axillary nerve in the region described as quadrilateral space. This clinical entity was first recognized and described by Cahill and Palmer [2], who investigated the outcomes of thoracic outlet surgery. The entrapment is usually attributable to fibrous bands, or secondary to hypertrophy of muscles enclosing the region. Glenoid labral cysts, direct crush injuries or traction-stretch trauma to the shoulder, soft tissue hematoma secondary to humeral fracture, and glenohumeral instabilities may play a role in the etiology of QSS [1, 3, 4]. Osteochondroma is a common benign tumor and frequently arises from the humerus. Although intermittent axillary nerve palsy caused by a proximal humeral exostosis was previously reported [5], osteochondroma as an etiological factor of classical QSS was not diagnosed.

QSS is characterized by poorly localized posterior shoulder pain, paresthesia over the lateral aspect of the shoulder and arm, distributing nondermatomally to forearm. The symptoms are aggravated by flexion and/or abduction and external rotation of the humerus. There is point tenderness over the quadrilateral space on posterior shoulder region [1, 6]. In the presented case, there was a palpable mass in the posterior axillary region accompanying the previously mentioned symptoms.

X-rays may reveal bony abnormalities, such as those observed in the subject. On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the shoulder, atrophy of the teres minor and/or deltoid muscles, innervated by the axillary nerve, are suggestive of QSS. Other causes, such as glenoid lesions, may also be demonstrated on MRI [4, 7, 8]. However, CT may be more helpful in cases with bony abnormalities.

On ENMG studies, decreased amplitudes along axillary nerve and abnormal findings for deltoid muscle were found in some patients [3]. However, in the presented case ENMG was normal. We can speculate that the relatively indirect compression effect of osteochondroma and the intermittent dynamic compressive effect of teres major with muscle contraction may be the cause of normal ENMG findings.

The occlusion of PHCA is controversial in QSS. The arteriography is considered to be diagnostic, but the prevalence of false-positive artriographies in normal population is unknown [1, 3]. In addition, MR angiography was found to have no value in the diagnosis of QSS [9]. Patients with QSS usually have a history of being treated conservatively with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, local steroid injections, or physical therapy without resolving symptoms. Therefore, the treatment is surgical decompression of the axillary nerve by sectioning of the fibrous bands, drainage of the hematoma, or excision of the lesions such as an osteochondroma or glenoidal labral cysts [1, 2, 4, 6].

A posterior approach, detaching posterior fibers of deltoid from scapular spine and teres minor from its insertion, and decompressing the space by blunt and sharp dissection [10] and an operative technique, using a curved or S-shaped incision over the area of maximum tenderness without dividing the deltoid [3] were defined by some authors. Most of the patients reported had complete relief of symptoms with either surgical technique. We also used a posterior approach without dividing the deltoid and the teres minor. With the incision extending down to proximal humerus longitudinally, the axillary nerve and PHCA were satisfactorily exposed and the ostechondroma was also excised.

Conclusion

In conclusion, QSS must be kept in mind when evaluating refractory shoulder pain. Clinicians must remember the characteristic clinical findings of poorly localized posterior shoulder pain, paresthesia over the lateral aspect of the shoulder and arm, and point tenderness over the quadrilateral space. Thoracic outlet syndrome, cervicalgies, rotator cuff tears, and impingement syndrome must be evaluated as differential diagnosis [6]. However, when the patient is diagnosed with QSS, the shoulder must be carefully palpated and routine shoulder x-rays must be obtained to determine other causes rather than fibrous bands and muscle hypertrophy.

Footnotes

An erratum to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11420-006-9040-1

Contributor Information

Meric Cirpar, Email: drmeric@yahoo.com.

Eftal Gudemez, Email: eftalgudemez@hotmail.com.

Ozgur Cetik, Email: ocetik@yahoo.com.

Murad Uslu, Email: mruslu@hotmail.com.

Fatih Eksioglu, Email: feksioglu@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Perlmutter GS (1999) Axillary nerve injury. Clin Orthop Relat Res 386:28–36 [PubMed]

- 2.Cahill BR, Palmer RE (1983) Quadrilateral space syndrome. J Hand Surg (Am) 8(1):65–69 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Francel TJ, Dellon AL, Campbell JN (1991) Quadrilateral space syndrome: diagnosis and operative decompression technique. Plast Reconstr Surg 87:911–916 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Robinson P, White LM, Lax M et al (2000) Quadrilateral space syndrome caused by glenoid labral cyst. AJR 175:1103–1105 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Witthaut J, Steffens KJ, Koob E (1994) Intermittant axillary nerve palsy caused by a humeral exostosis. J Hand Surg 19B:422–423 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Chautems RC, Glauser T, Waeber-Fey MC et al (2000) Quadrilateral space syndrome: case report and review of literature. Ann Vasc Surg 4:673–676 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Helms CA (2002) The impact of MR imaging in sports medicine. Radiology 224(3):631–635 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Linker CS, Helms CA, Russell CF (1993) Quadrilateral space syndrome: findings at MR imaging. Radiology 188:675–676 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Mochizuki T, Isoda H, Masui T et al (1994) Occlusion of the posterior humeral circumflex artery: detection with MR angiography in healthy volunteers and in a patient with quadrilateral space syndrome. AJR 163:625–627 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Azar MF (2003) Shoulder and elbow injuries. In: Canale ST (ed) Campbell's operative orthopaedics. Mosby, St. Louis, pp 2339–2375