Abstract

PTH binding to the PTH/PTHrP receptor activates adenylate cyclase/protein kinase A (PKA) and phospholipase C (PLC) pathways and increases receptor phosphorylation. The mechanisms regulating PTH activation of PLC signaling are poorly understood. In the current study, we explored the role of PTH/PTHrP receptor phosphorylation and PKA in PTH activation of PLC. When treated with PTH, LLCPK-1 cells stably expressing a green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged wild-type (WT) PTH/PTHrP receptor show a small dose-dependent increase in PLC signaling as measured by inositol trisphosphate accumulation assay. In contrast, PTH treatment of LLCPK-1 cells stably expressing a GFP-tagged receptor mutated in its carboxyl-terminal tail so that it cannot be phosphorylated (PD-GFP) results in significantly higher PLC activation (P < 0.001). The effects of PTH on PLC activation are dose dependent and reach maximum at the 100 nm PTH dose. When WT receptor-expressing cells are pretreated with H89, a specific inhibitor of PKA, PTH activation of PLC signaling is enhanced in a dose-dependent manner. H89 pretreatment in PD-GFP cells causes a further increase in PLC activation in response to PTH treatment. Interestingly, PTH and forskolin (adenylate cyclase/PKA pathway activator) treatment causes an increase in PLCβ3 phosphorylation at the Ser1105 inhibitory site and that increase is blocked by the PKA inhibitor, H89. Expression of a mutant PLCβ3 in which Ser1105 was mutated to alanine (PLCβ3-SA), in WT or PD cells increases PTH stimulation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate formation. Altogether, these data suggest that PTH signaling to PLC is negatively regulated by PTH/PTHrP receptor phosphorylation and PKA. Furthermore, phosphorylation at Ser1105 is demonstrated as a regulatory mechanism of PLCβ3 by PKA.

THE BIOLOGICAL RESPONSES to many extracellular signaling molecules are mediated via activation of signaling pathways downstream of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs).

PTH, an important regulator of Ca ion homeostasis and bone remodeling, exerts its effects by binding to the PTH/PTHrP receptor (or PTH1R) in bone and kidney. The PTH/PTHrP receptor is a member of GPCR family, which couples mainly to Gs to activate adenylate cyclase/cAMP/protein kinase A (PKA). PTH/PTHrP receptor also stimulates phospholipase C (PLC)/diacylglycerol, inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3), and Ca/protein kinase C pathways (1,2).

The PTH/PTHrP receptor undergoes agonist-dependent phosphorylation (3). Mutation of seven serine phosphorylation sites in the carboxyl-terminal of the PTH/PTHrP receptor resulted in a mutant PTH/PTHrP receptor that is not phosphorylated after PTH stimulation (4). The phosphorylation-deficient mutant PTH/PTHrP receptor, stably expressed in LLCPK-1 cells is impaired in PTH-dependent internalization and exhibits exaggerated cAMP signaling (4).

In the current study, LLCPK-1 renal tubular cells stably expressing a wild-type (WT), WT-green fluorescent protein-tagged (WT-GFP), phosphorylation-deficient (PD) or PD-GFP-tagged PTH/PTHrP receptor (4,5) were used to elucidate the role of receptor phosphorylation and PKA in PTH activation of the PLC/IP3 response. Our results suggest that PTH-activated PLC is controlled by receptor phosphorylation and PKA. The two mechanisms seem, however, to act independently.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

[Nle8,18,Tyr34]bPTH(1–34)NH2 (PTH) and Gly1Arg19 hPTH (1–28) NH2 were synthesized by a solid-phase method (Endocrine Unit, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA), purified by HPLC, and characterized by amino acid hydrolysis, N-terminal sequencing, and mass spectrography. Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was from Sigma (St. Louis, MO), bovine growth serum was from Hyclone (Logan, UT), and streptomycin-penicillin was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Tissue culture flasks, plates and other supplies were from Corning (Oneonta, NY) and Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). X-tremegene and Lipofectamine LTX transfection reagents were from Roche Applied Science (Indianapolis, IN) and Invitrogen, respectively. Forskolin was from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), H89 was from Biomol Research Laboratories Inc. (Plymouth Meeting, PA), and G418 was from Invitrogen. Immobilon membranes were from Millipore Corp. (Bedford, MA). The chemiluminescence kit was from PerkinElmer (Boston, MA). Antiphospho-specific PLCβ3 (Ser1105) antibody (no. 2484) was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against Gq (no. SC-393), G11 (no. SC-394), Gq/11 (no. SC-392), and PLCβ3 (no. SC-13958) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin (no. A2228) antibody and peroxidase-labeled goat antimouse and goat antirabbit antisera were from Sigma-Aldrich.

Stealth select control (scrambled), Gq and G11 small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) were from Invitrogen.

Cell culture

LLCPK-1 porcine renal tubular cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS or bovine growth serum. All media contained 1 μg/ml streptomycin and 100 U/ml penicillin. The cells were incubated in a humidified atmosphere containing 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37 C. Media were replaced every other day.

siRNA transfection

Stealth select siRNAs are 25-bp duplex oligoribonucleotides. The sense strand sequences of Gq, G11, and PLCβ3 siRNAs are 5′-UAA ACG UAC UCU UGC CAC UCU CUC C-3′, 5′-ACU GCU UUG AGA ACG UGA CAU CCA U-3′ and 5′-UAU GCU UUG CGC AGG AAG GUG UUC C-3′, respectively.

LLCPK-1 cells stably expressing rat WT (National Center for Biotechnology Information accession number NM_020073, GenBank) or PD PTH/PTHrP receptor (in pCDNA1) were transfected with siRNA using X-tremegene transfection reagent using the manufacturer’s protocol with some modifications. The cells were grown until they reached 50% confluency (24 h). X-tremegene (7 μl) reagent was mixed with 250 μl serum-free DMEM for 10 min at room temperature. siRNA (50 nm) was mixed in 250 μl serum-free DMEM. The two preparations were mixed and incubated for 20 min at RT. The complex was then added to cells grown in 6-well plate, prewashed once with 2 ml serum-free DMEM, and left with 1.5 ml serum-free DMEM (final volume is 2 ml/well). FBS at a final concentration of 10% was added 24 h after transfection, and incubation was continued for another 24 h. The cells were split and grown for 48 h before they were used for the experiments. Transfection efficiency was determined to be about 90% using fluorescein-labeled control siRNA.

Development of stable cell lines expressing mutant PLCβ3 in which Ser1105 was mutated to alanine (PLCβ3-SA): WT or PD cells were transfected with human WT (6) or mutant PLCβ3-SA (6) in pCR3.1 plasmid vector (provided by Dr. Barbara Sanborn, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO), which also encodes a neomycin resistance gene. Transfection was performed using Lipofectamine LTX. The plasmid DNA (1 μg) was mixed with a 100 μl serum-free DMEM and 7 μl of Lipofectamine LTX and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The complex was then added to cells grown in 12-well plate, prewashed once with 1 ml serum-free DMEM, and left with 800 μl serum-free DMEM (final volume is 900 μl/well). After 24 h of incubation, the medium was replaced with full growth medium containing 1.5 mg/ml G418 selection antibiotic. The cells that survived in the presence of G418 (G418 resistant cells) were then reseeded at very low density to select individual colonies. Individual colonies were picked, expanded, and then tested for PLCβ3 expression using Western blot analysis. G418 was omitted from the growth medium after 1 month. Three independent colonies for each cell line with similar expression levels were characterized by Western blot and were expanded for use in the study. Control cells were cells that underwent the whole process of transfection and antibiotic selection but did not show expression of PLCβ3-SA at final screening by Western blot analysis.

Measurement of intracellular IP3 accumulation

Cells were seeded in 12-well plates and incubated for 24 h at 37 C. Accumulated inositol phosphate (IPs) were measured as described previously (7). Full growth medium was removed and cells were radiolabeled at 37 C for 12 h with 2 μCi/ml [3H]myoinositol in 1 ml inositol- and serum-free DMEM supplemented with 0.1% BSA and 20 mm HEPES. Cells were then washed twice with PBS and preincubated with 20 mm LiCl for 60 min in serum-free DMEM containing 20 mm HEPES and 0.1% BSA. PTH or vehicle (10 mm acetic acid) was added, and the incubation was continued for the indicated time at 37 C. The incubation was terminated by placing the cells on ice, discarding the incubation medium, rinsing two times with ice-cold PBS and adding 0.5 ml of ice cold 5% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) for 20 min at room temperature. TCA extract was collected and the cells were rinsed with 1 ml double-distilled H2O. TCA extract was made to a final volume of 2 ml by adding 0.5 ml double-distilled H2O (final conc of TCA is 1.25%). Separation of the IPs in 1 ml of the TCA extract was performed by AG 1 × 8 anion exchange column chromatography (formate form, 100–200 mesh, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Free [H]inositol and glycerophosphate inositol fractions were washed and eluted with 10 ml of 10 mm inositol and 5 ml of 5 mm Borax/60 mm sodium formate, respectively. Inositol monophosphate) and inositol biphosphate were eluted with 5 ml of 0.7 m ammonium formate/0.1 m formic acid (8,9). The IP3 fraction was collected after elution with 5 ml of 1.05 ammonium formate/0.1 m formic acid.

Radioactivity in the 5 ml IP3 fraction mixed with 10 ml of scintillation liquid was counted using a liquid scintillation counter (model LS 6000IC; Beckman, Coulter, Inc., Fullerton, CA). Specific phosphoinositide hydrolysis was determined as percent of PTH-stimulated IP3/basal IP3 values.

Western blot analysis

Cells seeded in 12-well plates were grown as a monolayer until they reached 100% confluency (48 h). Cells were rinsed (two times) with PBS and then treated as indicated in serum-free DMEM containing 20 mm HEPES buffer and 0.1% BSA at 37C in a CO2 incubator. The medium was removed and the cells were placed on ice and rinsed (two times) with ice-cold PBS. The cells were lysed on ice using lysis buffer [62.5 mm Tris (pH 6.8), 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 1 mm EDTA (pH 8), 1 mm EGTA (pH 7.4), 0.5% aprotinin, 5 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride], and the lysates were resolved on 8% SDS-PAGE.

The proteins were transferred from the gel onto Immobilon membrane (Millipore); the membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk/0.2% Tween 20 in PBS. After incubation with appropriate primary rabbit (1:1000) or mouse (1:10,000) antibodies for 3 h at room temperature and secondary goat antirabbit (1:5000) or goat antimouse (1:10,000) peroxidase-labeled antibodies for 2 h at room temperature, the immunoreactive bands were detected with chemiluminescence and visualized using autoradiography.

Statistical analysis

The results are represented as the means ± sd of at least three experiments. Each condition was carried out in duplicates. One-way ANOVA was used for data analysis and significance was considered when P < 0.05.

Results

A PD PTH/PTHrP receptor mutant stably expressed in LLCPK-1 cells has increased IP3 accumulation in response to PTH treatment

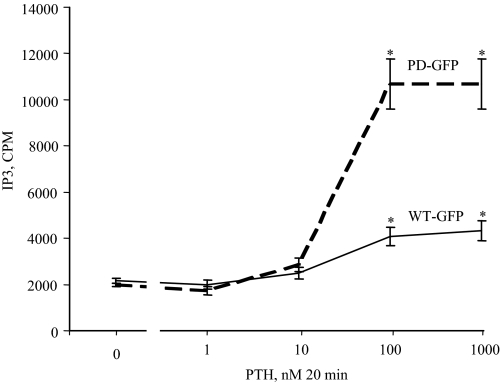

Development and characterization of LLCPK-1 cell lines stably expressing similar numbers of rat WT or PD PTH/PTHrP receptor that are tagged or not on the extracellular domain (exon E2) with green fluorescent protein (WT-GFP, PD-GFP, WT, and PD cells, respectively) were described previously (4,5). WT-GFP and PD-GFP cells were treated with PTH (0–1000 nm for 20 min) at 37 C in the presence of 20 mm Li Cl (to inhibit IP degradation) and PLC activation was assessed by measuring IP3 generation (Fig. 1). WT-GFP cells exhibited a small dose-dependent (Fig. 1) increase in IP3 accumulation (Fig. 1). PD-GFP cells, however, showed a dramatic increase in IP3 accumulation when compared with WT-GFP cells and the maximum IP3 increase was observed at the 100 nm PTH dose (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

LLCPK-1 stably expressing a PD-GFP tagged PTH/PTHrP receptor has enhanced PTH stimulation of IP3 accumulation. LLCPK-1 cells stably expressing a WT-GFP or PD-GFP PTH/PTHrP receptor were treated with PTH (0–1000 nm for 20 min at 37 C). The cells were then placed on ice, washed two times with ice-cold PBS, and assayed for IP3 as described in Materials and Methods. *, P < 0.001 vs. WT.

To ensure the consistency of the results, we tested other independent LLCPK-1 subclones stably expressing WT-GFP or PD-GFP. The results showed that PTH treatment (100 nm for 20 min at 37 C) causes higher PLC activation in all PD-GFP cells than WT-GFP cells (data not shown).

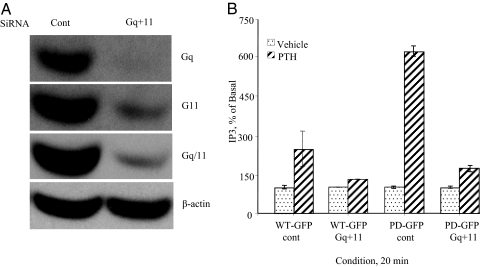

Gq and G11 siRNAs attenuate PTH activation of IP3 accumulation

WT-GFP or PD-GFP cells were transfected with control, Gq, G11, or Gq+11 siRNAs using X-tremegene transfection reagent. Effects of Gq and G11 siRNAs on Gq and G11 gene knockdown were examined by measuring expression of Gq and G11. Western blot analysis using anti-Gq, anti-G11, and anti-Gq/11 antibodies revealed that individual Gq or G11 siRNA transfection causes a small reduction in Gq/11 expression and only partially inhibit PTH stimulation of IP3 accumulation (data not shown). A combination of Gq and G11 siRNAs were then tested. A combination of Gq and G11 siRNAs markedly reduced Gq and 11 expression (Fig. 2A). Expression of β-actin in the same immunoblot, using β-actin antibody, was used as a control for sample loading and transfer (Fig. 2A, lower panel).

Figure 2.

Effects of Gq and G11 siRNAs on PTH activation of IP3 accumulation. A, LLCPK-1 stably expressing WT-GFP PTH/PTHrP receptor were transfected with control or Gq+11 siRNAs using X-tremegene transfection reagent as described in Materials and Methods. The cells were placed on ice, washed two times with ice-cold PBS, and lysed in SDS lysis buffer. The cell lysates were analyzed on 8% SDS-PAGE. The samples were transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane and blotted and reblotted with antibodies against Gq, G11, Gq/11, or β-actin and appropriate peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies. Detection was performed with chemiluminescence and the membranes were exposed to a film for 0.5 min. B, LLCPK-1 stably expressing WT-GFP or PD-GFP PTH/PTHrP receptor were transfected with control or Gq+11 siRNAs using X-tremegene transfection reagent as described in Materials and Methods. Cells were then treated with PTH (100 nm for 20 min at 37 C), placed on ice, washed two times with ice-cold PBS, and assayed for IP3 as described in Materials and Methods.

Cells were then treated with PTH (100 nm for 20 min at 37 C), and IP3 assay was performed. When a combination of both Gq and G11 siRNAs was used, PTH stimulation of IP3 accumulation was almost completely inhibited in both WT-GFP and PD-GFP cells (Fig. 2B).

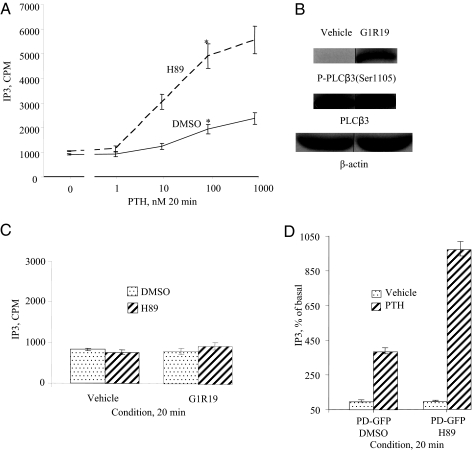

Inhibition of PKA in LLCPK-1 cells stably expressing WT PTH/PTHrP receptor enhances PTH stimulation of IP3 accumulation

Development and characterization of LLCPK-1 cell lines stably expressing WT PTH/PTHrP receptor (WT cells) were described previously (4,5). WT cells were treated with PTH (0–1000 nm for 20 min at 37 C) in the presence or the absence of PKA inhibitor (H89, 25 μm, 60 min) and IP3 accumulation was measured. WT cells pretreated with H89 had higher dose-dependent PTH stimulation of IP3 generation when compared with WT cells pretreated with vehicle (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

Effects of PKA inhibition on PTH stimulation of IP3 generation. A, PKA inhibition in LLCPK-1 cells stably expressing wild-type PTH/PTHrP receptor (WT cells) causes enhancement of PTH stimulation of IP3 accumulation: WT cells were treated with PTH (0–1000 nm for 20 min at 37 C) in the presence or absence of PKA inhibitor (H89, 25 μm, 30 min). The cells were then placed on ice, washed two times with ice-cold PBS, and assayed for IP3 as described in Materials and Methods. *, P < 0.02 vs. dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO)-treated cells. B, Treatment of LLCPK-1 stably expressing WT-PTH/PTHrP receptor with Gs-signal selective peptide Gly1Arg19 hPTH (1–28) causes an increase in PLCβ3 phosphorylation at Ser1105. WT cells were treated with Gs-signal selective peptide Gly1Arg19 hPTH (1–28) (G1R19) (1000 nm) for 5 min at 37 C. The cells were placed on ice, washed two times with ice-cold PBS, and lysed in SDS lysis buffer. The cell lysates were analyzed on 8% SDS-PAGE. The samples were transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane and blotted with anti-phospho-PLCβ3 (Ser1105) antibody and a peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. Detection was done with chemiluminescence, and the membranes were exposed to a film for 0.5 min (upper panel). The blots were stripped and reprobed with antitotal (phosphorylated and unphosphorylated) PLCβ3 antibody and a peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (middle panel). The blots were stripped and reprobed with a mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin antibody and a peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (lower panel). C, Inhibition of PKA in LLCPK-1 cells stably expressing wild-type PTH/PTHrP receptor (WT) does not increase stimulation of IP3 accumulation by Gs-signal selective peptide Gly1Arg19 hPTH (1–28). WT cells were treated with Gs-signal selective peptide Gly1Arg19 hPTH (1–28) (G1R19) (1000 nm) for 20 min at 37 C in the presence or absence of PKA inhibitor (H89, 25 μm, 30 min). The cells were then placed on ice, washed two times with ice-cold PBS, and assayed for IP3 as described in Materials and Methods. D, Inhibition of PKA causes a further increase in PTH stimulation of IP3 accumulation in LLCPK-1 stably PD-GFP PTH/PTHrP receptor. PD-GFP cells were treated with PTH (100 nm for 20 min at 37 C) in the presence or absence of PKA inhibitor (H89, 25 μm, 30 min). The cells were then placed on ice, washed two times with ice-cold PBS, and assayed for IP3 as described in Materials and Methods.

A Gs-signal selective peptide Gly1Arg19 hPTH (1–28) (100 nm, 5 min) that does not activate PLC pathway efficiently phosphorylates PLCβ3 and that phosphorylation is abolished by H89 (25 μm, 60 min) pretreatment (Fig. 3B and data not shown). Pretreatment of WT cells with H89, however, did not increase PLC activation by Gly1Arg19 hPTH (1–28) (1000 nm, 20 min) (Fig. 3C). The selectivity of Gly1Arg19 hPTH (1–28) has been demonstrated previously and has been confirmed in our cell system by finding that Gly1Arg19 hPTH (1–28) stimulation of IP3 accumulation in PD-GFP cells was much smaller than that induced by PTH and was detectable only at highest dose of 1000 nm (data not shown). The doses of PTH and Gly1Arg19 hPTH (1–28) used in our current study (100 and 1000 nm, respectively) have, however, induced comparable cAMP accumulation and PLCβ3 phosphorylation (data not shown).

Inhibition of PKA causes a further increase in PTH stimulation of IP3 accumulation in LLCPK-1 stably expressing a PD-GFP-PTH/PTHrP receptor

PD-GFP cells were treated with PTH (100 nm for 20 min at 37 C) in the presence or absence of PKA inhibitor (H89, 25 μm, 60 min) and assayed for IP3 accumulation. Pretreatment with H89 of PD-GFP cells further enhances PTH stimulation of IP3 accumulation (Fig. 3D) when compared with PD-GFP control cells pretreated with vehicle (Fig. 3D).

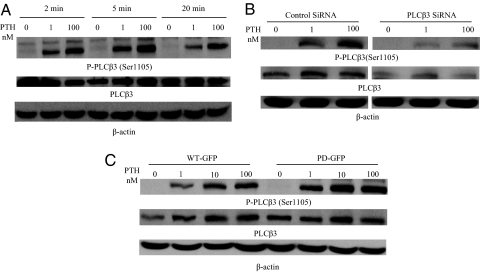

PTH treatment of WT-GFP or PD-GFP cells stimulates PLCβ3 phosphorylation on Ser1105

To study the PTH effects on phosphorylation of PLCβ3, WT cells were serum starved for 1 h and then treated with PTH for different times and using different concentrations (Fig. 4A, upper panel). PTH effects on PLCβ3 phosphorylation were then examined using Western blot analysis with anti-phospho PLCβ3 (Ser1105) antibody. PTH treatment causes a dose- and time-dependent increase in PLCβ3 phosphorylation at Ser1105 (Fig. 4A, upper panel) as shown by an immunoreactive band at the expected molecular mass (150 kDa) of PLCβ3. Reblotting using antitotal (phosphorylated and unphosphorylated) PLCβ3 shows expression of an immunoreactive band at the same molecular mass (150 kDa) of the phosphorylated PLCβ3 of (Fig. 4A, middle panel). The specificities of the antibodies for both the total and phosphorylated PLCβ3 were confirmed by transfecting WT cells with siRNA for PLCβ3 (Fig. 4B). Western blot analysis on cell lysates from PTH-treated (5 min, 0–100 nm) cells shows a corresponding reduction of both total and phosphorylated PLCβ3 150 kDa-immunoreactive bands (Fig. 4B upper and middle panels). Expression of β-actin in the same immunoblot was used as a control (Fig. 4B, lower panel).

Figure 4.

PTH effects on PLCβ3 phosphorylation. A, Treatment of LLCPK-1 stably expressing WT-PTH/PTHrP receptor causes a dose- and time-dependent increase in PLCβ3 phosphorylation at Ser1105. Upper panel, WT cells were serum starved for 1 h and then treated with PTH for different times or using different concentrations. The cells were placed on ice, washed two times with ice-cold PBS, and lysed in SDS lysis buffer. The cell lysates were analyzed on 8% SDS-PAGE. The samples were transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane and blotted with anti-phospho-PLCβ3 (Ser1105) antibody and a peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. Detection was done with chemiluminescence and the membranes were exposed to a film for 0.5 min. Middle panel, The blots were stripped and reprobed with antitotal (phosphorylated and unphosphorylated) PLCβ3 antibody and a peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. Lower panel, The blots were stripped and reprobed with a mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin antibody and peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. B, LLCPK-1 cells stably expressing WT-GFP PTH/PTHrP receptor were transfected with control or PLCβ3 siRNAs using X-tremegene transfection reagent as described in Materials and Methods. The cells were serum starved for 1 h and then treated with different concentrations PTH for 5 min. The cells were placed on ice, washed two times with ice-cold PBS, and lysed in SDS lysis buffer. The cell lysates were analyzed on 8% SDS-PAGE. The samples were transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane and blotted with antiphospho-PLCβ3 antibody and a peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (upper panel). Detection was performed with chemiluminescence and the membranes were exposed to a film for 0.5 min. The blots were stripped and reprobed with antitotal (phosphorylated and unphosphorylated) PLCβ3 antibody as described above (middle panel). The blots were stripped and reprobed with anti-β-actin antibody as described above (lower panel). C, LLCPK-1 stably expressing a PD-PTH/PTHrP receptor stimulates phosphorylation of PLCβ3 normally. Upper panel, WT-GFP and PD-GFP cells were serum starved for 1 h and then treated with different concentrations PTH for 5 min. The cells were placed on ice, washed two times with ice-cold PBS, and lysed in SDS lysis buffer. The cell lysates were analyzed on 8% SDS-PAGE. The samples were transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane and blotted with antiphospho-PLCβ3 (Ser1105) antibody and a peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. Detection was done with chemiluminescence and the membranes were exposed to a film for 0.5 min (upper panel). Middle panel, The blots were stripped and reprobed with antitotal (phosphorylated and unphosphorylated) PLCβ3 antibody as described above. Lower panel, The blots were stripped and reprobed with anti-β-actin antibody as described above.

We also tested PLCβ3 phosphorylation in PD-GFP cells. PTH treatment (0–100 nm for 5 min at 37 C) in PD-GFP cells stimulates PLCβ3 phosphorylation in a similar manner to that of WT-GFP cells (Fig. 4C, upper panel). Expression of total PLCβ3 in the same immunoblot was similar under all conditions (Fig. 4C middle panel). β-Actin antibody was used as a control (Fig. 4C, lower panel).

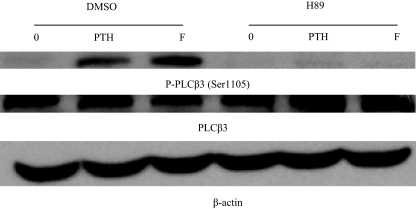

Effects of PKA activators and inhibitors on PLCβ3 phosphorylation

WT cells were serum starved for 1 h and then treated with PTH (100 nm) or forskolin (20 μm) for 5 min at 37 in the absence or presence of H89 PKA inhibitor. The effects on PLCβ3 phosphorylation were examined using Western blot with anti-phospho-PLCβ3 (Ser1105) antibody. Similar to PTH, forskolin treatment efficiently increased PLCβ3 phosphorylation and that phosphorylation was abolished by H89 (Fig. 5, upper panel). Expression of total PLCβ3 in the same immunoblot was similar under all conditions (Fig. 5, middle panel). β-Actin antibody was used as a control (Fig. 5, lower panel).

Figure 5.

Effect of PKA activators and inhibitors on PLCβ3 phosphorylation. Upper panel, LLCPK-1 cells stably expressing WT-PTH/PTHrP receptor were serum starved for 1 h and then treated with PTH (100 nm) or forskolin (20 μm) for 5 min at 37 in the absence or presence of H89 PKA inhibitor. The cells were placed on ice, washed two times with ice-cold PBS, and lysed in SDS lysis buffer. The cell lysates were analyzed on 8% SDS-PAGE. The samples were transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane and blotted with anti-phospho-PLCβ3 (Ser1105) antibody and a peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. Detection was done with chemiluminescence. Middle panel, The blot was stripped and reprobed with antitotal (phosphorylated and unphosphorylated) PLCβ3 antibody as described above. Lower panel, The blot was stripped and reprobed with anti-β-actin antibody as described above. DMSO, Dimethylsulfoxide.

Expression of PLCβ3-SA in WT or PD cells increases PTH stimulation of IP3 formation

WT or PD cells stably expressing PLCβ3-SA were developed as described in Materials and Methods. Consistent with expression of PLCβ3-SA that is not phosphorylated on Ser1105, PTH treatment (100 nm, 5 min) does not cause a corresponding increase in PLCβ3 phosphorylation in WT or PD cells expressing PLCβ3-SA mutant (Fig. 6A, upper and middle panels). PLCβ3 phosphorylation was instead similar to that observed in WT or PD control cells (Fig. 6A, upper and middle panels) that express only endogenous PLCβ3.

Figure 6.

Characterization of WT or PD LLCPK-1 cells stably expressing a mutant PLCβ3-SA. A, PLCβ3-SA mutant is not phosphorylated in response to PTH treatment. WT or PD cells control or stably expressing PLCβ3-SA were serum starved for 1 h and then treated with PTH (100 nm for 5 min at 37 C). The cells were placed on ice, washed two times with ice-cold PBS, and lysed in SDS lysis buffer. The cell lysates were analyzed on 8% SDS-PAGE. The samples were transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane and blotted with antiphospho-PLCβ3 (Ser1105) antibody and a peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (upper panels). Detection was done with chemiluminescence. The blots were stripped and reprobed with antitotal (phosphorylated and unphosphorylated) PLCβ3 antibody as described above (middle panels). The blot was stripped and reprobed with anti-β-actin antibody as described above (lower panels). B, Expression of PLCβ3-SA in WT or PD cells increases PTH stimulation of IP3 formation. Upper panels, WT cells control or stably expressing PLCβ3-SA were treated with PTH (0–100 nm for 5–60 min at 37 C). The cells were then placed on ice, washed two times with ice-cold PBS, and assayed for IP3 as described in Materials and Methods. Lower panels, PD cells control or stably expressing PLCβ3-SA were treated with PTH (0–100 nm for 5–60 min at 37 C). The cells were then placed on ice, washed two times with ice-cold PBS, and assayed for IP3 as described in Materials and Methods.

WT cells expressing PLCβ3-SA were treated with PTH (0–100 nm for 5–60 min at 37 C) and assayed for IP3 accumulation. IP3 accumulation was remarkably higher in PLCβ3-SA-expressing cells (Fig. 6B, upper right panel), compared with control cells (Fig. 6B, upper left panel). PTH effects on IP3 accumulation in both cell lines were dose and time dependent.

Likewise, expression of PLCβ3-SA in PD cells causes profound dose- and time-dependent increase in PTH stimulation of IP3 accumulation (Fig. 6B, lower right panel) that was higher than that observed in PD control cells (Fig. 6B, lower left panel).

The results were reproducible in three independent cell lines (data not shown). Additionally, expression of similar levels of WT PLCβ3 in WT cells caused only a small increase in PTH stimulation of IP3 formation, which was greatly smaller than that observed in WT cells expressing PLCβ3-SA mutant (data not shown).

Discussion

Under normal conditions, continuous receptor stimulation does not result in continuous increase in downstream effector activation and biological responses. Receptor signaling is, instead, rapidly and tightly controlled by a process termed desensitization.

Occupancy of the PTH/PTHrP receptor by PTH stimulates receptor coupling to G proteins mainly Gs/cAMP/PKA and increases receptor phosphorylation on seven serines on the carboxyl-terminal tail of the receptor (3,4,5). One of the consequences of PTH/PTHrP receptor activation is the PLC-mediated hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate leading to the activation of protein kinase C and mobilization of intracellular Ca2+ (1,2,7). The mechanisms regulating PTH/PTHrP receptor signaling to PLC are poorly understood. The goal of the current study is to asses the role of receptor phosphorylation and PKA in PTH activation of PLC signaling.

Treatment of LLCPK-1 cells stably expressing a phosphorylation-deficient PTH/PTHrP receptor with PTH results in increased PLC/IP3 accumulation in dose- and time-dependent manners. The increase in PLC/IP3 signaling is significantly higher than that observed in LLCPK-1 cells stably expressing wild-type PTH/PTHrP receptor (P < 0.001). These results suggest that PTH/PTHrP receptor phosphorylation controls receptor signaling via the PLC/IP3 pathway. This finding is consistent with those reported for other GPCRs. For example, elimination of phosphorylation of GPCRs by deleting the C-terminal domain, which contains the phosphorylation sites for the Gq-coupled neurokinin (10), α1B-adrenergic (11), and platelet-activating factor receptors (12) or by specifically mutating the phosphorylation sites for the Gq-coupled α1B-adrenergic (13) and platelet-activating factor receptors (12) and the Gi-coupled IL-8 receptor and chemokine receptor A (14) causes impaired desensitization of the PLC response.

A role for internalization has been described for other Gq-coupled receptors (15). The receptor for Neuromedin B, for example, undergoes rapid homologous desensitization consequent to agonist stimulation, which is mediated by receptor internalization (15). Our previous studies have demonstrated that PD-PTH/PTHrP receptor stably expressed in LLCPK-1 cells is impaired in internalization. PTH activation of PLC has been shown to be directly proportional to the PTH/PTHrP cell surface receptor density in LLCPK-1 cells (16). The enhanced PLC signaling of the PD-PTH/PTHrP receptor may hence be mediated by the increased PTH/PTHrP cell surface receptor (4) in the PD-PTH/PTHrP receptor-expressing cells. Further studies will be needed to evaluate these mechanisms.

GPCRs activate PLC via coupling to Gq, G11, Gi, and/or Gβγ (17,18,19,20). Although the PTH/PTHrP receptor has been reported to activate PLC, the G protein(s) that mediate this activation are not known. Using siRNA for Gq and G11 proteins, the current study demonstrates for the first time that PTH/PTHrP receptor activation of PLC is mediated by both Gq and G11 and that enhanced PLC signaling in the PD cells is due to impaired regulation of the same pathways. The ability of Gq and G11 siRNAs, in combination but not individually, to effectively attenuate PTH activation of PLC suggests a functional redundancy between Gq and G11 G-proteins and that they can compensate for each other.

The formylpeptide chemoattractant receptor, which couples to a pertussis toxin-sensitive G protein, activates both PLC and cAMP/PKA pathways. The resulting PKA activation phosphorylates PLCβ3 and seemingly reduces the ability of Gβγ to activate PLC (21). The effects of PTH-activated PKA on PLC signaling are not known. Using H89, a specific PKA inhibitor, we show that inhibition of PTH activation of PKA results in increased PTH activation of PLC/IP3 signaling. These results suggest that PTH activation of PKA acts as a negative regulator of PLC signaling. Activation of the Gs-coupled β2-adrenoceptor expressed in HEK-293 cells or the endogenous receptor for prostaglandin E1 in N1E-115 neuroblastoma cells induced PLC stimulation, which was caused by cAMP formation (22). The inability of H89 pretreatment to stimulate PLC activation by Gly1Arg19 hPTH (1–28), a Gs signal-selective peptide, which weakly stimulates PLC signaling (22), suggests that PKA influences a PLC pathway that is not downstream of the Gs/cAMP pathway.

PLCβ3 has been reported to undergo phosphorylation on Ser1105 by PKA and that this phosphorylation down-regulates PLC activation (6,23). Interestingly, we report that the PKA activators, PTH and forskolin, increase phosphorylation of PLCβ3 on Ser1105; this phosphorylation is inhibited by H89. These findings suggest that the inhibitory effects of PKA on PLC/IP3 signaling may be mediated by PKA phosphorylation of PLCβ3. This hypothesis has been verified by demonstrating that expression, in WT cells, of a mutant PLCβ3-SA, which cannot be phosphorylated at Ser1105 due to replacement of Ser1105 with alanine results in great amplification of PTH stimulation of IP3 accumulation. Expression of similar levels of WT PLCβ3 results in only a small increase in PTH stimulation of IP3 accumulation ensuring that the response obtained in the mutant PLCβ3 expressing cells is due to the elimination of Ser 1105 phosphorylation rather than the overall increase in PLCβ3 expression (data not shown).

Finally, we investigated whether the role of receptor phosphorylation and PKA on PLC signaling are dependent or independent. The further enhancement of PLC signaling in PD cells after pretreatment with H89 or after expression of the mutant PLCβ3-SA demonstrates that the two mechanisms are regulating PLC independently. Whereas PKA controls PTH generation of IP3 via PLCβ3, receptor phosphorylation seems to prevent excessive and/or prolonged coupling to Gq and G11 and consequently controls signaling via multiple PLC isoforms. Consistent with our previous findings, the efficient PTH phosphorylation of PLCβ3 exhibited in the PD cells is a reflection of the exaggerated cAMP response, compared with WT-expressing cells (4). It is interesting to note that receptor phosphorylation may therefore have some positive regulatory role on PLCβ3 and that may explain the detectable PTH stimulation of IP3 accumulation in WT cells.

The PTH/PTHrP receptor is therefore a model of GPCRs in which PLC activation is tightly regulated by receptor phosphorylation and by a negative cross-talk via the Gs/PKA pathway. The dominance of the Gs/PKA over the tightly regulated Gq-11/PLC pathway likely results in differential downstream biological effects of PTH. Changing the Gs/Gq-11 signaling ratio by receptor phosphorylation and PKA may therefore be particularly physiologically important for the PTH/PTHrP receptor.

Taken together, the current study demonstrates that PTH activation of PLC signaling is mediated by coupling to Gq and G11 and that PLC signaling is negatively regulated by receptor phosphorylation and PKA. Phosphorylation of PLCβ3 on Ser1105 by PKA is further suggested as a mechanism mediating, at least partly, the attenuation of PLC signaling by PKA.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Henry Kronenberg and Dr. Harald Jueppner for their helpful comments and suggestions. We also thank Dr. Barbara M. Sanborn (Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO) for generously providing us with the WT and PLCβ3-SA plasmids.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health-National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants 1 K01 DK64073, RO1 DK062285, and PO1 DK45485.

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online May 1, 2008

Abbreviations: FBS, Fetal bovine serum; GFP, green fluorescent protein; GPCR, G protein-coupled receptor; IP, inositol phosphate; IP3, inositol triphosphate; PD, phosphorylation deficient; PKA, protein kinase A; PLC, phospholipase C; SDS, sodium dodecyl sulfate; siRNA, small interfering RNA; TCA, trichloroacetic acid; WT, wild type.

References

- Abou-Samra AB, Jüppner H, Force T, Freeman MW, Kong XF, Schipani E, Urena P, Richards J, Bonventre JV, Potts Jr JT, Kronenberg HM, Segre GV 1992 Expression cloning of a common receptor for parathyroid hormone and parathyroid hormone-related peptide from rat osteoblast-like cells: a single receptor stimulates intracellular accumulation of both cAMP and inositol trisphosphates and increases intracellular free calcium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89:2732–2736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jüppner H, Abou-Samra AB, Freeman M, Kong XF, Schipani E, Richards J, Kolakowski Jr LF, Hock J, Potts Jr JT, Kronenberg HM, Segre GV 1991 A G protein-linked receptor for parathyroid hormone and parathyroid hormone-related peptide. Science 254:1024–1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian F, Leung A, Abou-Samra AB 1998 Agonist-dependent phosphorylation of the parathyroid hormone/parathyroid hormone-related peptide receptor. Biochemistry 37:6240–6246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tawfeek HA, Qian F, Abou-Samra AB 2002 Phosphorylation of the receptor for PTH and PTHrP is required for internalization and regulates receptor signaling. Mol Endocrinol 16:1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tawfeek HA, Che J, Qian F, Abou-Samra AB 2001 Parathyroid hormone receptor internalization is independent of protein kinase A and phospholipase C activation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 281:E545–E557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue C, Dodge KL, Weber G, Sanborn BM 1998 Phosphorylation of serine 1105 by protein kinase A inhibits phospholipase Cβ3 stimulation by Gαq. J Biol Chem 273:18023–18027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida-Klein A, Guo J, Xie LY, Jüppner H, Potts Jr JT, Kronenberg HM, Bringhurst FR, Abou-Samra AB, Segre GV 1995 Truncation of the carboxyl-terminal region of the rat parathyroid hormone (PTH)/PTH-related peptide receptor enhances PTH stimulation of adenylyl cyclase but not phospholipase C. J Biol Chem 270:8458–8465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebecchi MJ, Pentyala SN 2000 Structure, function, and control of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C. Physiol Rev 80:1291–1335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takasu H, Gardella TJ, Luck MD, Potts Jr JT, Bringhurst FR 1999 Amino-terminal modifications of human parathyroid hormone (PTH) selectively alter phospholipase C signaling via the type 1 PTH receptor: implications for design of signal-specific PTH ligands. Biochemistry 38:13453–13460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alblas J, van Etten I, Khanum A, Moolenaar WH 1995 C-terminal truncation of the neurokinin-2 receptor causes enhanced and sustained agonist-induced signaling. Role of receptor phosphorylation in signal attenuation. J Biol Chem 270:8944–8951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lattion AL, Diviani D, Cotecchia S 1994 Truncation of the receptor carboxyl terminus impairs agonist-dependent phosphorylation and desensitization of the α1B-adrenergic receptor. J Biol Chem 269:22887–22893 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano T, Honda Z, Sakanaka C, Izumi T, Kameyama K, Haga K, Haga T, Kurokawa K, Shimizu T 1994 Role of cytoplasmic tail phosphorylation sites of platelet-activating factor receptor in agonist-induced desensitization. J Biol Chem 269:22453–22458 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diviani D, Lattion AL, Cotecchia S 1997 Characterization of the phosphorylation sites involved in G protein-coupled receptor kinase- and protein kinase C-mediated desensitization of the α1B-adrenergic receptor. J Biol Chem 272:28712–28719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson RM, Ali H, Pridgen BC, Haribabu B, Snyderman R 1998 Multiple signaling pathways of human interleukin-8 receptor A. Independent regulation by phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 273:10690–10695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benya RV, Kusui T, Shikado F, Battey JF, Jensen RT 1994 Desensitization of neuromedin B receptors (NMB-R) on native and NMB-R-transfected cells involves down-regulation and internalization. J Biol Chem 269:11721–11728 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J, Iida-Klein A, Huang X, Abou-Samra AB, Segre GV, Bringhurst FR 1995 Parathyroid hormone (PTH)/PTH-related peptide receptor density modulates activation of phospholipase C and phosphate transport by PTH in LLC-PK1 cells. Endocrinology 136:3884–3891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer JL, Graber SG, Waldo GL, Harden TK, Garrison JC 1994 Selective activation of phospholipase C by recombinant G-protein α- and βγ-subunits. J Biol Chem 269:2814–2819 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry Y, Niederhoffer N, Sick E, Gies JP 2006 Heptahelical and other G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) signaling. Curr Med Chem 13:51–63 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park D, Jhon DY, Lee CW, Lee KH, Rhee SG 1993 Activation of phospholipase C isozymes by G protein βγ subunits. J Biol Chem 268:4573–4576 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee SG 2001 Regulation of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C. Annu Rev Biochem 70:281–312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali H, Fisher I, Haribabu B, Richardson RM, Snyderman R 1997 Role of phospholipase Cβ3 phosphorylation in the desensitization of cellular responses to platelet-activating factor. J Biol Chem 272:11706–11709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M, Evellin S, Weernink PA, von Dorp F, Rehmann H, Lomasney JW, Jakobs KH 2001 A new phospholipase-C-calcium signalling pathway mediated by cyclic AMP and a Rap GTPase. Nat Cell Biol 3:1020–1024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haribabu B, Richardson RM, Fisher I, Sozzani S, Peiper SC, Horuk R, Ali H, Snyderman R 1997 Regulation of human chemokine receptors CXCR4. Role of phosphorylation in desensitization and internalization. J Biol Chem 272:28726–28731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]