Abstract

Mineralocorticoid receptors (MRs) are classically known to be expressed in the distal collecting duct of the kidney. Recently it was reported that MR is identified in the heart and vasculature. Although MR expression is also found in the brain, it is restricted to the hippocampus and cerebral cortex under normal condition, and the role played by MRs in brain remodeling after cerebral ischemia remains unclear. In the present study, we used the mouse 20-min middle cerebral artery occlusion model to examine the time course of MR expression and activity in the ischemic brain. We found that MR-positive cells remarkably increased in the ischemic striatum, in which MR expression is not observed under normal conditions, during the acute and, especially, subacute phases after stroke and that the majority of MR-expressing cells were astrocytes that migrated to the ischemic core. Treatment with the MR antagonist spironolactone markedly suppressed superoxide production within the infarct area during this period. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR revealed that spironolactone stimulated the expression of neuroprotective or angiogenic factors, such as basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), whereas immunohistochemical analysis showed astrocytes to be cells expressing bFGF and VEGF. Thereby the incidence of apoptosis was reduced. The up-regulated bFGF and VEGF expression also appeared to promote endogenous angiogenesis and blood flow within the infarct area and to increase the number of neuroblasts migrating toward the ischemic striatum. By these beneficial effects, the infarct volume was significantly reduced in spironolactone-treated mice. Spironolactone may thus provide therapeutic neuroprotective effects in the ischemic brain after stroke.

MINERALOCORTICOID RECEPTORS (MRS) are classically known to be expressed in the distal collecting duct of the kidney, in which they are involved in the regulation of water and electrolyte balance. However, recent studies suggest that MRs are also expressed in other organs, including the vasculature, heart, and limited area of the brain, and investigations into the functions of MRs in these organs have been proceeding. For example, cardiac myocytes reportedly express MRs (1), and their activation is associated with myocardial hypertrophy and fibrosis (2,3). Moreover, MR inhibition appears to mitigate the adverse cardiac remodeling caused by chronic pressure overload, including increased left ventricular dimension and myocardial fibrosis, which are related in part to oxidative stress and apoptosis (4). In the vasculature, the endothelial dysfunction and increased media/lumen ratios seen in the resistance arteries of angiotensin II-infused rats are reportedly diminished by MR antagonists (5). And in the kidney, aldosterone acts directly to induce generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) through activation of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase in mesangial cells, and MR blockade suppresses the resultant oxidative stress, which has been associated with glomerular mesangial injury (6). In addition to these in vivo animal studies, clinical trials have demonstrated the survival benefit of aldosterone inhibition in patients with heart failure (7,8), and addition of a MR antagonist to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors markedly reduces urinary protein excretion in patients with chronic renal failure (9) or early diabetic nephropathy (10). Taken together, these studies suggest that MR blockade exerts a protective effect on the vasculature and target organs that is separate from its blood pressure lowering effect.

Some recent studies have focused on the effects of MR activation or inhibition on neuroprotection after cerebral ischemia. In stroke-prone spontaneous hypertensive rats, for instance, MR blockade by spironolactone was found to reduce infarct size via reduction of epidermal growth factor receptor expression (11). Those investigators suggested that spironolactone treatment improved the ability of blood vessels to dilate, which led to a reduction in infarct size. Eplerenone also reportedly exerts a protective effect against ischemic brain damage, in part through improvement of cerebral blood flow in the penumbra and reduction of oxidative stress (12). Conversely, MR activation with deoxycorticosterone acetate induced an increase in wall thickness and the wall to lumen ratio in the middle cerebral artery (MCA), which led to inward hypertrophic remodeling and an increase in infarct volume after cerebral ischemia (13). Under normal conditions, however, MR expression is not found in the brain except the hippocampus; basomedial, central nucleus of the amygdala; cortical layers II, III, and V; and paraventricular nucleus in the hypothalamus (14,15,16). So it remains unclear how MR antagonists produce their beneficial effects after cerebral ischemia and whether MR activation/inhibition has a direct effect on ischemic neural cells.

With that as background, our study presented here focused on the activities of MRs under ischemic conditions in the brain and examined the therapeutic potential of MR blockade after ischemia. After inducing 20-min MCA occlusion (MCAo) to produce a nonfatal stroke in mice, we examined changes in the expression of MRs in the ischemic area during the acute, subacute, and chronic phases after stroke and the long-term effects of spironolactone on the ischemic brain up to postoperative d 14. Moreover, we immunohistochemically examined the ischemic striatum in these mice to determine the effects of spironolactone on infarct area, the incidence of apoptosis, oxidative stress, vascular regeneration, and the number of neuroblasts migrating toward the ischemic area. During the acute and subacute phases, we also used quantitative real-time RT-PCR to assess expression of such neuroprotective factors as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), nerve growth factor (NGF), glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) and an angiogenic factor, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), in the ischemic brain, with and without administration of spironolactone. Finally, we immunohistochemically examined the ischemic area to confirm the expression of these neuroprotective and angiogenic factors and to identify the cells expressing them.

Materials and Methods

Animals and induction of MCAo

All experimental procedures were performed in accordance with Kyoto University guidelines for animal experiments. Adult male C57BL/6J mice weighting 20–22 g (8 wk old) were housed in an air-conditioned room at 25 C with a 12-h light, 12-h dark cycle. We performed nonfatal 20-min MCAo using the standard trans-luminal method, which has been described previously (17,18). Briefly, after anesthetizing mice with 5% halothane and maintaining them on 1% halothane, an 8-0 nylon monofilament coated with silicone was inserted from the left common carotid artery to the base of the left MCA. After 20 min of occlusion, the filament was withdrawn, and the arteries were reperfused. The left common carotid artery was ligated to prevent bleeding. We confirmed both occlusion and reperfusion of the MCA using a fiber-shaped laser Doppler perfusion imager (Omegawave, Tokyo, Japan). To exclude the effect of ligating the left common carotid artery, we also prepared sham-operated control mice in which MCAo was not performed, but the left common carotid artery was ligated.

Drug administration

An osmotic pump (model 2002; Alzet Osmotic Pumps Co., Cupertino, CA) containing either spironolactone (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) dissolved in propylene glycol or vehicle propylene glycol only (control) was implanted in the back of each mouse 48 h before the MCAo. The osmotic pump was used to continuously administer spironolactone at 300 μg/d, a dosage greater than that previously reported to substantially reduce the specific binding of endogenous aldosterone in rat tissues (19), but that had no effect on blood pressure (11). The administration was continued for 7 or 14 d after MCAo.

Immunohistochemical examination of the ischemic striatum

After the induction of 20-min MCAo, vehicle- and spironolactone-treated mice were killed on postoperative d 2–28, and the harvested brains were subjected to immunohistochemical examination using a standard procedure described previously (20). In all of our experiments, a free-floating 30-μm coronal section at the level of the anterior commissure (bregma), which was obtained from each mouse, was immunostained and examined under a confocal microscope (LSM5 PASCAL; Carl Zeiss SMT AG, Oberkochen, Germany). The sections were subjected to immunohistochemical analysis with following antibodies: mouse antineuron-specific nuclear protein (Neu-N) antibody, a neuronal marker (1:100; Chemicon, Temecula, CA); mouse antiglia fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) antibody, an astrocyte marker (1:200; Chemicon); purified rat monoclonal antibody against mouse platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule (PECAM)-1, an endothelial cell marker (1:100; PharMingen, San Diego, CA); goat polyclonal antibody against MR (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); rabbit polyclonal antibody against ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule 1 (Iba1), a specific microglial marker (1:200; Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd., Osaka, Japan); goat polyclonal antibody against double-cortin (Dcx), a marker of migrating neuroblasts (1:100; Santa Cruz); goat polyclonal antibody against bFGF (1:100; Santa Cruz); and VEGF (1:100; Santa Cruz). The anti-Neu-N antibody was labeled with Alexa-647 (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA) and the anti-GFAP antibody with Alexa-488 at our laboratory. The fluorescent secondary antibodies used for antimouse PECAM-1, MR, Iba1, Dcx, bFGF, and VEGF were Alexa Fluor 546-labeled antirat IgG, Alexa Fluor 546-labeled antigoat IgG, and Alexa Fluor 488-labeled antirabbit IgG (1:200; Invitrogen). In our stroke model, the infarct area, in which loss of Neu-N antigenicity was observed, was confined to the striatum, and the ischemic striatum at the level of the anterior commissure was photographed from d 0 to d 28 after MCAo.

To investigate the time course of the MR expression and identify the cells expressing MRs in the ischemic striatum, brain coronal sections harvested from mice subjected to 20-min MCAo were stained with anti-Neu-N, anti-GFAP, anti-PECAM-1 and anti-MR antibodies. Then on d 1, 2, 7, 14, or 28 after MCAo, the ischemic striatum from the mice was photographed at ×20 magnification, and the MR-positive area (square millimeters) was calculated. To assess apoptosis, we stained brain sections with a rabbit polyclonal antibody against single-strand DNA (ssDNA; Dako, Carpinteria, CA) as described previously (21). Coronal sections from each mouse were incubated first with the anti-ssDNA antibody (1:50) for 60 min and then with a secondary antibody (Alexa-Flour 488-labeled antirabbit IgG, 1:200; Invitrogen). In the vehicle- and spironolactone-treated mice, the numbers of apoptotic (ssDNA positive) cells in the ischemic core (∼0.2 mm2) of the striatum, which was photographed at ×20 magnification on d 7 after MCAo, were manually counted, as previously described (18). Apoptotic cell numbers were then expressed as cells per square millimeters. We also evaluated the production of ROS in the ischemic core in both vehicle- and spironolactone-treated mice at ×20 magnification using the oxidative fluorescent dye dihydroethidium (diHE; 2 × 10−6 m; Sigma) on d 7 after MCAo. Upon reaction with superoxide, diHE is oxidized to ethidium, which binds to DNA in the nucleus and fluoresces red. As described previously, brain sections were immediately incubated in diHE in PBS for 30 min at 37 C (22). The samples were then examined under a confocal microscope, and fluorescence intensities in the nonischemic striatum and ischemic striatum of vehicle- and spironolactone-treated mice were analyzed and quantified using computer-imaging software. The data are expressed as relative intensities normalized to the intensity in the nonischemic striatum, as previously described (6). To examine the expression of bFGF and VEGF, brain coronal sections prepared from vehicle- and spironolactone-treated mice on d 7 after MCAo were immunostained. The areas (square millimeters) immunostained by anti-bFGF or anti-VEGF were examined at ×20 magnification and quantified in the nonischemic contralateral and ischemic ipsilateral striatum. Vascular density was quantified as previously described, with slight modification (23). On d 7 or 14 after MCAo, vascular density in the ischemic striatum was examined at ×20 magnification by determining the number of pixels depicting PECAM-1 positivity per microscope field (512 × 512 pixels): this ratio was expressed as percent area. The number (counts per square millimeter per mouse) of Dcx-positive cells migrating from the subventricular zone (SVZ) toward the ischemic striatum also was calculated at ×20 magnification on d 7 after MCAo.

Microsphere analysis

We estimated blood flow in the ischemic striatum by delivering fluorescent microspheres as described previously, with some modifications (24,25). When appropriate-sized microspheres are used, regional blood flow is proportional to the number of microspheres trapped in the region of interest. On d 14 after 20-min MCAo, red fluorescent microspheres (15 μm; Invitrogen) were injected into the left common carotid artery (100,000 microspheres per mouse). The injection was made over a period of 1 min to avoid the streaming of beads that can occur with bolus injections. Five minutes after the injection, the mice were killed and their brains harvested. Two serial 50-μm frozen sections cut at the level of the bregma were prepared from each mouse. One was immunostained with anti-Neu-N antibody to identify ischemic striatum after fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde, and the other was used to observe microspheres trapped in vessels within the corresponding ischemic core of the striatum. The numbers of microspheres in the ischemic cores photographed at ×20 magnification were visually counted under a confocal microscope (LSM PASCAL; Carl Zeiss). The relative blood flow in the ischemic striatum of vehicle- and spironolactone-treated mice was then expressed as the ratio of the number of fluorescent microspheres in the ischemic core to that in the nonischemic striatum of sham-operated mice (set as 100%).

Analysis of the integrity of the vasculature formed after MCAo

To assess the maturity of newly formed vessels, we evaluated the extravasation of Evans Blue dye. Evans Blue (0.1 ml of 2% in saline) was injected into vehicle- and spironolactone-treated mice via the tail vein on d 14 after 20-min MCAo, as previously described, with a slight modification (26). Six hours after injection, the mice were killed, their brains were removed, and coronal sections at the bregma were prepared and observed to confirm Evans Blue leakage into the ischemic striatum. In addition, mice injected with Evans Blue 18 h after MCAo and killed 6 h after injection served as a positive control.

Analysis of infarct size after 20-min MCAo in vehicle- or spironolactone-treated mice

On d 14 after MCAo, infarct size was quantified in vehicle- and spironolactone-treated mice. The infarct area (square millimeters per field/mouse) at the level of the anterior commissure (the bregma) was defined and quantified as the region in which Neu-N antigenicity disappeared from the striatum observed at ×5 magnification, as previously described (17,27). Measurement of infarct volume was carried out as previously described with slight modification (27). Five coronal sections (approximately −1, −0.5, ± 0, +0.5, and +1 mm from the bregma) were prepared from each mouse, and infarct area (square millimeters) was measured in each. Thereafter the infarct areas were summed among the slices and multiplied by the slice thickness to provide the infarct volume (cubic millimeters3).

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR

In sham-operated, vehicle-treated, and spironolactone-treated mice, the region of the ipsilateral hemisphere extending from +2 to +7 mm from the tip of the frontal lobe, which includes the entire striatum, was harvested on d 2 or 7 after MCAo, after which total RNA was extracted. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was then performed using Premix Ex TaqTM (Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan). The PCR primers used were: BDNF (NM 007540), CTGAATGAATGGACCCAATGAGAAC (forward) and CTGATGCTCAGGAACCCAGGA (reverse); NGF (NM013609), TTTCTATACTGGCCGCAGTGA (forward) and TGATCAGAGTGTAGAACAACATGGA (reverse); GDNF (NM 010275), CCCACGTTTCGCATGGTTC (forward) and TGGGCAGCTGAGGTTGTCAC (reverse); bFGF (NM 008006), GGACGGCTGCTGGCTTCTAA (forward) and CAGTTCGTTTCAGTGCCACATAC (reverse); VEGF (NM 001025250), GAGGATGTCCTCACTCGGATG (forward) and GTCGTGTTTCTGGAAGTGAGCAA (reverse); and β-actin (NM 007393), CATCCGTAAAGACCTCTATGCCAC (forward) and ATGGAGCCACCATCCACA (reverse). All primers were produced by Takara Bio. Levels of BDNF, NGF, GDNF, bFGF, and VEGF mRNA are presented after normalization to the level of β-actin mRNA.

Neurological functional test

To assess recovery of motor function after 20-min MCAo, we used a rota-rod machine as previously described, with slight modifications (28). The rota-rod test is a well-established procedure for testing the balance and coordination aspects of motor performance in rats and mice (29). And it has been also reported that the accelerating rota-rod test is available for the assessment of the impaired motor function induced by transient cerebral ischemia (28,30). We therefore used this test to assess the recovery of motor function in sham-operated (n = 5), vehicle-treated (n = 8), and spironolactone-treated mice (n = 9). The mice were trained until they were able run on a rod rotating at 9 rpm (second speed) for more than 60 sec. After the training was complete, we placed each mouse on the rod and changed the rotation speed incrementally every 10 sec from 6 rpm (first speed) to 30 rpm (fifth speed) over the course of 50 sec and monitored the time until the mouse fell off. The mice were given three sequential trials, and the values were averaged to obtain the exercise times of the mice. These exercise times (seconds) were recorded just before induction of MCAo and on postoperative d 2, 7, 10, and 14.

Measurement of blood pressure and heart rate

To assess the effects of spironolactone on systemic circulation, blood pressures, and heart rates were measured in vehicle- and spironolactone-treated mice using a noninvasive tail-cuff system before and on d 14 after MCAo, as previously described (31). All measurements were made between 1700 and 1800 h. After taking five sequential measurements, readings with the highest and lowest systolic pressures were discarded. The remaining three readings, including the corresponding diastolic pressures and heart rates, were averaged to obtain single session values.

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as the mean ± se. Comparison of means between two groups was done using Student’s t test. When more than two groups were compared, ANOVA was used to evaluate significant differences among groups and, if there was one, a post hoc multiple comparison test was carried out. Values of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Expression of MR in the brain under normal conditions

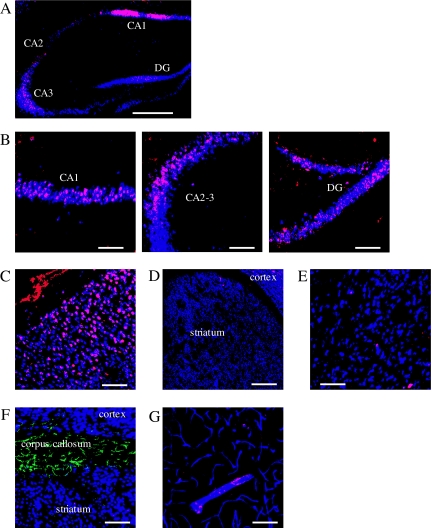

We initially examined MR expression in the hippocampus, cortex, striatum, and corpus callosum in mice under normal basal conditions (Fig. 1). Some reports have shown that MRs are expressed in the CA1–3 areas and the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus, cerebral cortex, and amygdala (14,32). We also detected MR expression in the CA1–3 areas and the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus (Fig. 1, A and B, red) and found that almost all of the MR-expressing cells were Neu-N-positive neurons (blue). Likewise, some MR-positive neurons (red + blue = purple) were observed in the cerebral cortex (Fig. 1C). On the other hand, MR expression was extremely low in the striatum, in which only a few MR-positive neurons were detected (Fig. 1, D and E). Under these conditions, GFAP-positive astrocytes (green) were detected in the corpus callosum, which is adjacent to the striatum, but few astrocytes were observed within the striatum. Astrocytes in the corpus callosum did not express MRs (Fig. 1F). Within the vasculature (blue) of the lateral part of the striatum, adjacent to the corpus callosum, MR were weakly expressed in some areas of large vessels, but no expression was detected in the microvessels (Fig. 1G).

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical examination for MR expression in the brain under normal conditions. A–E, Immunostaining of Neu-N (blue) and MR (red) in the hippocampus (A), CA1, CA2–3 region of the dentate gyrus (B), cerebral cortex (C), and striatum (D and E). Neu-N-positive neurons expressing MR are shown in purple (blue + red). F, Immunostaining of Neu-N (blue), MR (red), and GFAP (green) in the corpus callosum. G, Immunostaining of PECAM-1 (blue), MR (red), and GFAP (green) in the striatum. Scale bar, 500 μm (A and D), magnification, ×5; scale bar, 100 μm (B and C, E and G), magnification, ×20.

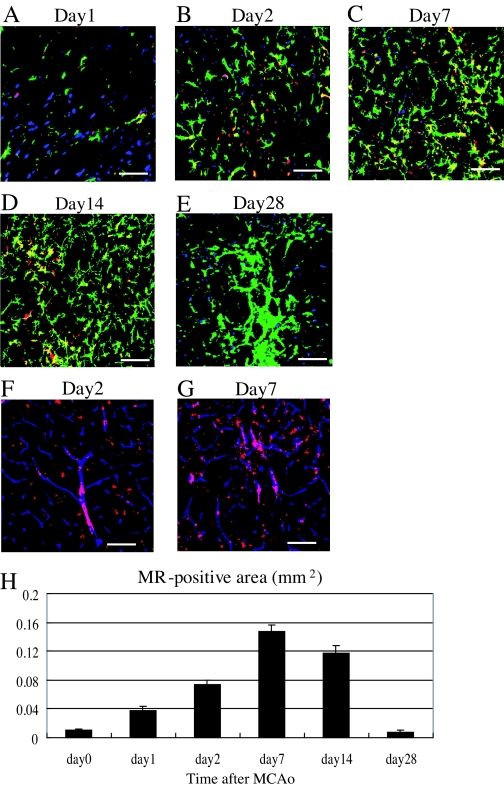

Time course of MR expression in the ischemic striatum and identification MR-expressing cells

When we subjected mice to 20-min MCAo to induce a nonfatal stroke, the infarct area was confined entirely to the striatum. After inducing a stroke, we examined the ischemic striatum on postoperative d 1, 2, 7, 14, and 28 to determine the time course of MR expression in the ischemic striatum and identify the MR-expressing cells at several time points (Fig. 2). On d 1 after MCAo, the number of MR-positive neurons (red + blue = purple) was slightly higher in the ischemic boundary zone than in the nonischemic contralateral striatum (Fig. 2A). Some of the astrocytes (green) migrating toward the ischemic core of striatum were also positive for MR (Fig. 2A). By d 2 after MCAo, the numbers of astrocytes expressing MRs (green + red = yellow) had increased, whereas the number of MR-positive neurons had declined, compared with d 1 (Fig. 2B). Still larger numbers of MR-positive astrocytes were detected in the ischemic core on d 7 and 14, whereas few MR-positive neurons were detected (Fig. 2, C and D). From d 2 to 14 after MCAo, MR-expressing astrocytes (yellow) accounted for more than 80% of the entire MR-positive area (red). Notably, even greater numbers of astrocytes were detected in the ischemic core on d 28 after MCAo, but MR expression was considerably diminished (Fig. 2E). We also detected a slight increase of MR expression in the large vessels (red + blue = purple) present within the ischemic striatum on d 2 and 7 after MCAo but not in the small vessels (Fig. 2, F and G). Apparently the ischemic insult caused by the 20-min MCAo had little effect on MR expression in endothelial cells. As with astrocytes, many microglia were observed migrating into the ischemic striatum on postoperative d 2 and 7, whereas few were detected in the nonischemic striatum. The majority of microglia were observed on the outside of PECAM-1-positive endothelial tubes, including large vessels. The number of MR-expressing microglia was very small on postoperative d 2, and none were seen on postoperative d 7 (data not shown). We therefore think that the cells expressing MR in large endothelial tubes are PECAM-1-positive endothelial cells, and those expressing MR outside or adjacent to the vessels might be astrocytes (Fig. 2G). Moreover, on d 7 and 14 after MCAo, we observed no significant change of MR expression in the cerebral cortex or the hippocampus, which were not affected in our nonfatal stroke model (data not shown). From these results, we calculated the MR-expressing areas (square millimeters per field) in the ischemic striatum on d 1, 2, 7, 14, and 28 after MCAo (Fig. 2H). The MR-expressing area (square millimeters per field) was greatest on d 7 after MCAo (nonischemic striatum: 0.011 ± 0.001; ischemic striatum: d 1, 0.038 ± 0.005; d 2, 0.073 ± 0.006; d 7, 0.147 ± 0.010; d 14, 0.117 ± 0.011; and d 28, 0.008 ± 0.002 mm2; n = 5/each point) but had nearly disappeared by d 28. In summary, MR expression was clearly enhanced in the ischemic striatum during the acute and, especially, subacute phase after nonfatal stroke, and the majority of cells expressing MR in the ischemic striatum were astrocytes.

Figure 2.

Evaluation of the MR-positive area in the ischemic striatum during the acute, subacute, and chronic phases after MCAo. A–E, Representative fluorescence photomicrographs showing immunostaining of Neu-N (blue), MR (red), and GFAP (green) in the ischemic striatum on d 1 (A), 2 (B), 7 (C), 14 (D), and 28 (E) after induction of 20-min MCAo. F and G, Detection of vascular endothelial cells expressing MR by immunostaining PECAM-1 (blue) and MR (red) in the ischemic striatum on d 2 (F) and 7 (G) after MCAo. H, Time-dependent changes in the size of the MR-positive area (square millimeters) in the ischemic striatum. Scale bar, 100 μm (A–G); magnification, ×20.

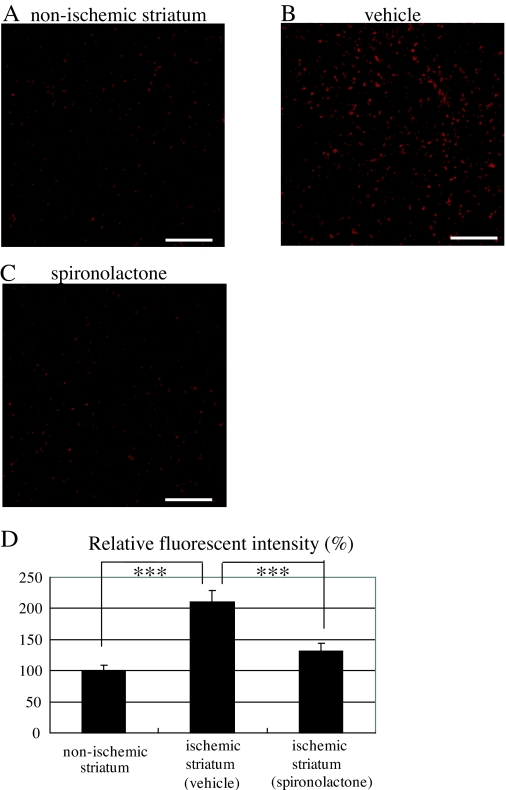

Effect of MR antagonism on production of ROS in the ischemic striatum

To begin to clarify the functions of the MRs expressed after transient cerebral ischemia, we investigated the effects of the MR antagonist spironolactone on ROS production by staining the ischemic striatum of vehicle- and spironolactone-treated mice with diHE on d 7 after MCAo. Figure 3, A–C, shows ROS production in the nonischemic striatum (Fig. 3A) and the ischemic core of the striatum in vehicle-treated (Fig. 3B) and spironolactone-treated (Fig. 3C) mice. Quantitative analysis of the relative diHE fluorescence intensities indicates that, compared with the nonischemic striatum (n = 10), ROS production was increased throughout the ischemic striatum in vehicle-treated mice (n = 10) (210.2 ± 18.2%, P < 0.001 vs. control). There was markedly less ROS production in the spironolactone-treated mice (n = 9), however (131.1 ± 13.4%, P < 0.001 vs. vehicle) (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

Effects of spironolactone on ROS production in the ischemic striatum on d 7 after 20-min MCAo. A–C, Representative photomicrographs of diHE fluorescence (red), revealing ROS in the nonischemic striatum under normal condition (A) and in the ischemic striatum in vehicle- (B) and spironolactone-treated (C) mice. D, Quantitative analysis of diHE fluorescence intensities in the nonischemic striatum (n = 10) and the ischemic striatum of vehicle- (n = 10) and spironolactone-treated mice (n = 9). ***, P < 0.001. Scale bar, 100 μm (A–C); magnification, ×20.

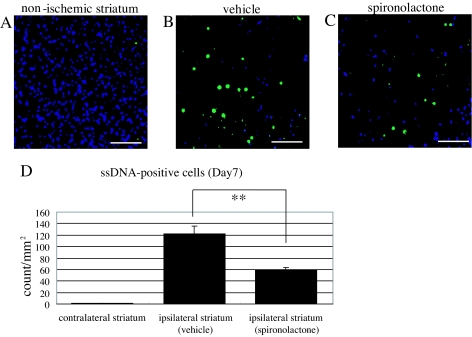

Incidence of apoptosis in the ischemic striatum

To evaluate effect of MR blockade on the incidence of apoptosis among damaged cells including neurons in the ischemic striatum on d 7 after MCAo, we immunostained the ischemic cores in vehicle- and spironolactone-treated mice using anti-ssDNA (green) and anti-Neu-N (blue) antibodies, after which the apoptotic cells were quantified as the number (counts per square millimeters per mouse) of ssDNA-positive cells. Apoptotic cells were readily detected in the ischemic striatum, although very few were detected in the nonischemic contralateral striatum (Fig. 4, A and D) (1.2 ± 0.1, n = 10). Notably, significantly fewer apoptotic cells were detected in spironolactone-treated mice (n = 11) than vehicle-treated mice (n = 10) (Fig. 4, B, C, and D) (58.7 ± 4.9 vs. 122.3 ± 13.3, P < 0.01).

Figure 4.

Antiapoptotic effect of spironolactone on d 7 after 20-min MCAo. A–C, Representative photomicrographs showing immunostaining of ssDNA (green) and Neu-N (blue) in the nonischemic contralateral striatum (A) and in the ischemic ipsilateral striatum in vehicle- (B) and spironolactone-treated (C) mice. D, Quantification of ssDNA-positive apoptotic cells in the nonischemic (n = 10) and ischemic striatum in the vehicle- (n = 11) and spironolactone-treated (n = 10) mice. **, P < 0.01. Scale bar, 100 μm (A–C); magnification, ×20.

Effect of MR blockade on expression of neuroprotective and angiogenic factors in the ischemic striatum

We also examined the effect of spironolactone on the expression of several neuroprotective and angiogenic factors (BDNF, NGF, GDNF, bFGF, and VEGF) in the ischemic striatum during the acute and subacute phases after 20-min MCAo. In our preparation, the left common carotid artery was permanently ligated after induction of 20-min MCAo, reducing cerebral blood flow by about 15–20% in the ipsilateral hemisphere, compared with the contralateral side. Therefore, to exclude the influence of left common carotid artery ligation on the expression of the aforementioned neuroprotective and angiogenic factors, we prepared sham-operated mice in which MCAo was not carried out, but the left common carotid artery was ligated. Subsequent quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis showed that there were no significant differences in the gene expression of these molecules in the ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres of sham-operated mice (data not shown).

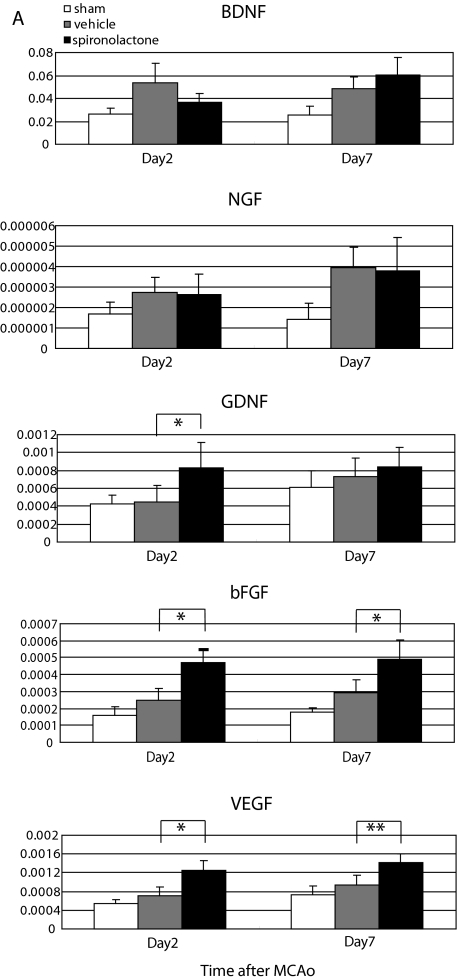

We then evaluated expression of BDNF, NGF, GDNF, bFGF, and VEGF mRNA in the ipsilateral hemisphere of sham-operated (n = 8), vehicle-treated (n = 12), and spironolactone-treated (n = 12) mice on d 2 and 7 after MCAo (Fig. 5A). We found that expression of all five molecules tended to be higher in the vehicle- and spironolactone-treated mice than in sham-operated mice on both days. No significant difference in the expression of BDNF and NGF was observed between vehicle- and spironolactone-treated mice, and expression of GDNF was significantly higher in spironolactone-treated than vehicle-treated mice only on d 2 after MCAo. On the other hand, expression of bFGF and VEGF was significantly higher in the spironolactone group on both d 2 and 7.

Figure 5.

Effects of spironolactone on the expression of neuroprotective and angiogenic factors in the ischemic brain on d 2 and 7 after 20-min MCAo. A, Quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis of BDNF, NGF, GDNF, bFGF, and VEGF levels in the ipsilateral hemisphere in sham-operated (n = 8) and vehicle- (n = 12) and spironolactone-treated (n = 12) mice on d 2 and 7 after MCAo. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 spironolactone vs. vehicle. B–D, Representative photomicrographs showing immunostaining of bFGF (red), Neu-N (blue), and GFAP (green) on d 7 after MCAo in the nonischemic striatum (B) and the ischemic striatum of vehicle- (C) and spironolactone-treated (D) mice. E–G, Representative photomicrographs showing immunostaining of VEGF (red), Neu-N (blue), and GFAP (green) on d 7 after MCAo in the nonischemic striatum (E) and the ischemic striatum of the vehicle- (F) and spironolactone-treated (G) mice. H, Measurement of the area (square millimeters) of bFGF and VEGF positivity in the nonischemic (n = 3) and ischemic striatum of the vehicle- and spironolactone-treated mice (n = 8–11). **, P < 0.01. Scale bar, 100 μm (B–G); magnification, ×20.

Given those findings, we carried out an immunohistochemical analysis of bFGF and VEGF expression in the ischemic striatum of vehicle- and spironolactone-treated mice. In the nonischemic striatum, a few cells stained positively for bFGF or VEGF, and almost all were neurons (bFGF: 0.0079 ± 0.0007 mm2, n = 3; VEGF: 0.0119 ± 0.0008 mm2, n = 3) (Fig. 5, B, E, and H). In the vehicle-treated mice, expression of bFGF (Fig. 5C) and VEGF (Fig. 5F) were enhanced in the ischemic ipsilateral striatum on d 7, and the majority of cells expressing these factors were astrocytes. Moreover, as was seen in the RT-PCR assays, treatment with spironolactone significantly increased the expression of both bFGF (Fig. 5D) and VEGF (Fig. 5G), compared with vehicle [bFGF: 0.0564 ± 0.0039 mm2 (n = 8) vs. 0.1335 ± 0.0098 mm2 (n = 10), P < 0.01; VEGF: 0.0516 ± 0.0045 mm2 (n = 10) vs. 0.1186 ± 0.0067 mm2 (n = 11), P < 0.01] (Fig. 6L).

Figure 6.

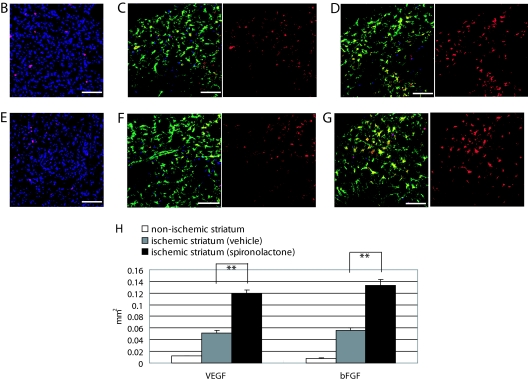

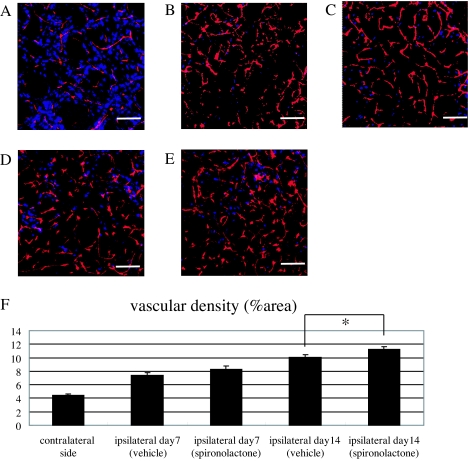

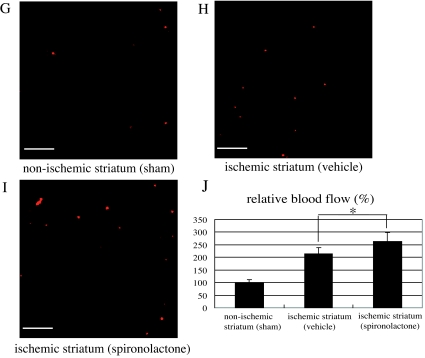

Effects of spironolactone on vascular regeneration and blood flow in the ischemic striatum after 20-min MCAo. A–E, Histological examination of the vasculature in the ischemic core stained with mouse PECAM-1 (red) and Neu-N (blue). Shown are representative photomicrographs in the nonischemic striatum (A) and the ischemic striatum of vehicle- (B and D) and spironolactone-treated (C and E) mice on d 7 (B and C) and 14 (D and E) after MCAo. F, Quantitative analysis of the relative area of PECAM-1 positivity (percent area) in the nonischemic striatum (n = 5) and ischemic striatum of vehicle- and spironolactone-treated mice (n = 9–10) on d 7 and 14 after MCAo. G–I, Representative photomicrographs of sections of the nonischemic striatum of a sham-operated mouse (G) and the ischemic core of the striatum in vehicle- (H) and spironolactone-treated (I) mice on d 14 after MCAo. J, Quantitative analysis of the relative blood flow in the nonischemic striatum of sham-operated mice (n = 5) and ischemic core of the striatum in vehicle- (n = 11) and spironolactone-treated mice (n = 11) on d 14 after MCAo. The relative blood flow in the ischemic striatum in vehicle- and spironolactone-treated mice was expressed as the ratio of number of fluorescent microspheres in the ischemic core to that in the nonischemic striatum of sham-operated mice (set as 100%). *, P < 0.05 spironolactone vs. vehicle. Scale bar, 100 μm (A–E, G–I); magnification, ×20.

Vascular density and blood flow in the infarct area after stroke

Because treatment with spironolactone appeared to increase the expression of angiogenic factors, we next examined the extent to which spironolactone could induce an increase in vascular density within the ischemic striatum. We found that by d 7 after MCAo, the PECAM-1-positive vascular density was clearly higher in the ischemic core of both vehicle- (Fig. 6B) and spironolactone-treated (Fig. 6C) mice than in the nonischemic striatum (Fig. 6A). At that point there was no significant difference in the vascular density (percent area) between the vehicle- and spironolactone-treated mice, however (vehicle: 7.4 ± 0.4%, n = 10; spironolactone: 8.3 ± 0.5%, n = 10) (Fig. 6F). By contrast, on d 14 after MCAo, the vascular density in the spironolactone-treated mice (n = 10) was significantly greater than in the vehicle-treated mice (n = 9) (11.2 ± 0.4 vs. 10.1 ± 0.4%, P < 0.05) (Fig. 6, D, E, and F). As shown in the representative photomicrographs (Fig. 6, G–I), the number of microspheres (red) in the ischemic core in vehicle- and spironolactone-treated mice was markedly higher than in the nonischemic striatum. Moreover, the relative blood flow in the spironolactone-treated mice (n = 11) was significantly higher than in the vehicle-treated mice (n = 11) (262.2 ± 36.8 vs. 215.1 ± 24.3%, P < 0.05) (Fig. 6J). Evans Blue leakage was clearly seen within the ischemic lesion in the striatum (n = 4) 24 h after MCAo but was not seen in any of the vehicle- (n = 7) or spironolactone-treated mice (n = 9) on d 14 after MCAo (data not shown). This suggests that the maturity of newly formed vessels in the ischemic striatum in both vehicle- and spironolactone-treated mice had been fully constructed at least on postoperative d 14 after cerebral ischemia, and spironolactone might have a potential to promote endogenous angiogenesis without attenuating the integrity of the vasculature.

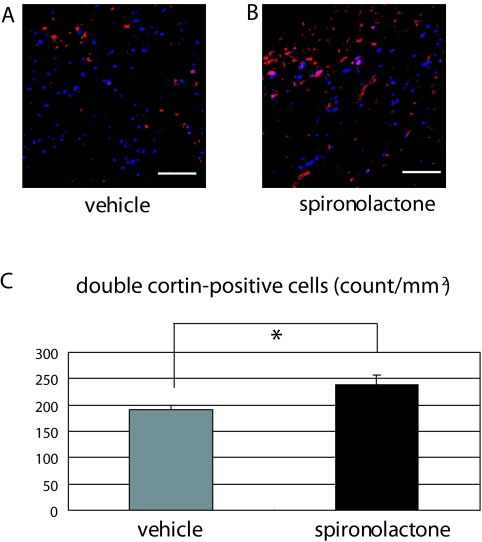

Effect of MR blockade on neurogenesis

To examine the effect of MR antagonism on neurogenesis under ischemic conditions, we quantified the number of Dcx-positive neuroblasts migrating from the SVZ to the ischemic area on d 7 after MCAo. We detected no neuroblasts in the nonischemic striatum. On the other hand, we detected numerous migrating neuroblasts in the ischemic striatum, and there were significantly greater numbers in spironolactone-treated than vehicle-treated mice (237.9 ± 19.3 vs. 191.1 ± 8.4 counts/mm2 (n = 6 in each group), P < 0.05) (Fig. 7, A–C).

Figure 7.

Effects of spironolactone on migration of neuroblasts toward the ischemic striatum after 20-min MCAo. A and B, Immunostaining of Neu-N (blue) and Dcx (red) in the ischemic striatum of vehicle- (A) and spironolactone-treated (B) mice on d 7 after MCAo. C, Quantitative analysis of the numbers (counts per field) of Dcx-positive neuroblasts in the ischemic striatum of vehicle- and spironolactone-treated mice (n = 6/each group). *, P < 0.05. Scale bar, 100 μm (A and B); magnification, ×20.

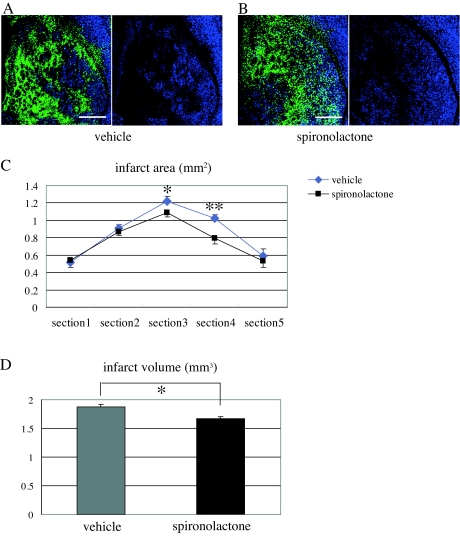

Effect of MR blockade on infarct size after MCAo

Finally, we examined the effect of spironolactone treatment on infarct size on d 14 after MCAo. We found that, compared with vehicle, spironolactone reduced infarct area, especially at the level of bregma (section 3) and + 0.5 mm from bregma (section 4), which were seriously affected by ischemic damage in our stroke model (Fig. 8, A–C). As a result, the infarct volume in spironolactone-treated mice was significantly (∼10%) smaller than in vehicle-treated mice (spironolactone: 1.673 ± 0.032 mm3, n = 8; vehicle: 1.87 ± 0.050 mm3, n = 7; P < 0.01) (Fig. 8D).

Figure 8.

Effects of spironolactone on infarct size after 20-min MCAo. A and B, Representative fluorescence photomicrographs showing the ischemic striatum of vehicle- (A) and spironolactone-treated (B) mice on d 14 after MCAo. The black area, in which Neu-N-positive neurons are not observed, is the infarcted area. C, Measurement of the infarct areas (square millimeters) in the ischemic striatum in five coronal sections (−1, −0.5, ± 0, +0.5, and +1 mm from bregma) in vehicle- (n = 7) and spironolactone-treated (n = 8) mice. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 spironolactone vs. vehicle in the corresponding section. D, Measurement of the infarct volume (cubic millimeters) in the two treatment groups. *, P < 0.05. Scale bar, 500 μm (A and B); magnification, ×5.

Effect of MR blockade on recovery of motor function after MCAo

The exercise times of the sham-operated mice did not change during the 2-wk period of the experiment. By contrast, the exercise times of the vehicle- and spironolactone-treated mice were markedly reduced on d 2 after MCAo, after which time-dependent recovery of motor function was observed. Spironolactone-treated mice tended to have longer exercise times than vehicle-treated mice, but the difference was not significant (data not shown).

Effect of drug treatment on blood pressure and heart rate

The data summarized in Table 1 show that there were no differences between blood pressure and heart rate in vehicle- (n = 8) and spironolactone-treated (n = 8) mice and no change in blood pressure over the course of the 14-d follow-up after MCAo. Thus, the dose of spironolactone used had no effect on blood pressure. A significant increase of heart rate was observed in both groups on d 14. We assume that this is an effect of invasion itself.

Table 1.

Blood pressures (mm Hg) and heart rates (counts per minute) in vehicle- and spironolactone-treated mice before (d 0) and 14 d after MCAo

| Vehicle | Spironolactone | |

|---|---|---|

| Blood pressure (d 0) | 111.7 ± 3.6/75.1 ± 1.9 | 109.4 ± 4.1/74.1 ± 3.3 |

| Blood pressure (d 14) | 110.1 ± 2.3/67.9 ± 3.1 | 107.9 ± 3.3/68.3 ± 2.6 |

| Heart rate (d 0) | 563.9 ± 17.1 | 587.5 ± 15.2 |

| Heart rate (d 14) | 643.4 ± 11.7 | 658.3 ± 12.2 |

Values are means ± se; n = 8 in each group.

Discussion

In the present study, we examined the time course of MR expression after transient cerebral ischemia, using a mouse nonfatal stroke model (20 min MCAo). In the brain, MR is generally expressed in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex but not in the striatum under normal conditions. In this study, however, we found that MR expression in the striatum was markedly increased under ischemic condition during the acute and, especially, subacute phases after MCAo. The majority of the cells expressing MR in the ischemic striatum were astrocytes, although a slight increase of the number of MR-positive neurons was detected during the acute phase. In addition, vascular endothelial cells in large vessels expressed MR, but only a small number of such vessels were detected in the nonischemic striatum, and that number was not increased under ischemic conditions. We therefore suggest that astrocytes are the key cell type involved in MR-mediated brain remodeling after cerebral ischemia.

Astrocytes, which are known to migrate to ischemic areas in the brain, are activated by chemokines and cytokines secreted from necrotic tissues and/or leukocytes infiltrating the infarct area. Once activated, astrocytes support tissue repair processes by removing debris (33) and secreting a number neurotrophic factors, including BDNF, GDNF, NGF, bFGF, ciliary neurotrophic factor and neutrotrophins 3, 4, and 5. On the other hand, they also produce various cytotoxic mediators and inflammatory cytokines, including nitric oxide (NO), TNF-α and IL-1, -6, and -8 (34). Consequently, whereas it is well recognized that astrocytes play an important role in brain remodeling after ischemia, it is less clear whether their activities are ultimately beneficial or harmful. Our present findings indicate that blockade of the up-regulated MRs on astrocytes during the acute and subacute phases after transient cerebral ischemia effectively reduces infarct size. We suggest that the neuroprotection provided by the MR antagonist spironolactone was meditated via four mechanisms: 1) reduction of ROS production; 2) induction of bFGF and VEGF expression by astrocytes; 3) prevention of the apoptosis of neurons; and 4) enhancement of angiogenesis.

MR activation promotes oxidative stress by stimulating nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase to increase ROS generation (35). In the heart, MR activation also stimulates activation of a number of downstream signaling pathways, leading to expression of inflammatory mediators (e.g. TNF-α, monocyte chemotactic protein-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1), fibrosis, and vascular endothelial and myocardial dysfunction. In addition, Edarabone, a potent scavenger of hydroxyl radicals, reportedly exerts an early neuroprotective effect and suppresses oxidative DNA damage in the ischemic brain (36). In the present study, ROS generation was markedly increased in the ischemic striatum after MCAo, and MR blockade by spironolactone effectively attenuated that generation. This suppression of oxidative stress led to a significant reduction in the incidence of apoptosis in the ischemic striatum of spironolactone-treated mice.

It is well known that aldosterone and cortisol (corticosterone in mice) bind to MRs with equal affinity and that MRs have a 10-fold higher affinity for corticosterone than glucocorticoid receptors (GRs) (37). It is also accepted that 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type II (11β-HSD2) metabolizes cortisol to cortisone (11-dehydroxycorticosterone in mice), preventing it from binding to and activating MRs. In the brain, however, 11β-HSD2 activity is limited to the subcommissural organ, nucleus tractus solitarius, and amygdala (38). Because cells of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) have the ability to pump aldosterone back across the barrier, levels of aldosterone are normally low in brain tissue (39). Due to transient destruction of the BBB caused by the cerebral ischemia, however, aldosterone may enter the ischemic striatum and bind to MR. Spironolactone may thus provide neuroprotection in the damaged ischemic striatum, in part by suppressing MR activation by aldosterone until the BBB can be restored. On the other hand, adrenalectomy promotes neurogenesis in the hippocampus (40), which suggests glucocorticoid released from the adrenal glands readily enters the brain and exerts effects in the hippocampus via MRs and/or GRs. It therefore seems plausible to us that because 11β-HSD2 is not present in the striatum, and because MR expression is markedly up-regulated in the ischemic striatum, cortisol is able to exert effects in the ischemic striatum via formation of glucocorticoid-MR complexes. Furthermore, elevation of ROS levels reportedly leads to activation of the glucocorticoid-MR complex (41). Thus, by reducing ROS levels, spironolactone may also contribute to neuroprotection after cerebral ischemia by suppressing both oxidative DNA damage and activation of the cortisol-MR complex.

It is well known that cerebral ischemia up-regulates the expression of bFGF (42,43). Recent studies suggest that bFGF supports the survival of brain neurons in culture and protects them from anoxia, hypoglycemia, and ROS (44,45,46). In addition, one report suggests bFGF is expressed by activated astrocytes in brain (47), whereas another suggests bFGF reduces DNA fragmentation and prevents down-regulation of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 in the ischemic hemisphere after permanent MCA occlusion (48). In the present study, we detected numerous bFGF-positive astrocytes in the ischemic striatum on postoperative d 7 and found that bFGF antigenicity was up-regulated by spironolactone. This suggests spironolactone may act to protect damaged neurons from apoptosis, at least in part, by increasing of bFGF-expression in the ischemic core.

It also has been shown that that the angiogenic factor VEGF (49) is increased in the ischemic striatum (43). Consistent with those findings, we observed that after induction of MCAo in mice, expression of VEGF was clearly increased in the ischemic striatum, mainly in migrating astrocytes, and that spironolactone further enhanced VEGF expression in astrocytes on postoperative d 7. The up-regulated expression of both bFGF and VEGF would be expected to promote angiogenesis in the ischemic striatum, as was observed in spironolactone-treated mice on postoperative d 14. Increased vascularity is reportedly associated with improved neurological recovery in human stroke patients (50). Given that neovascularization provides trophic support to and removes toxic products from damaged cells, including neurons, we suggest that astrocytes also exert a neuroprotective effect in the ischemic brain by expressing VEGF and bFGF and that spironolactone enhances that effect, in part by promoting neovascularization via up-regulated expression of these angiogenic/neuroprotective factors. Moreover, the relative blood flow in the ischemic striatum was significantly increased in spironolactone-treated mice on d 14 after MCAo, which suggests spironolactone effectively increases the size of the vascular bed formed after cerebral ischemia.

Throughout the life of adult animals, neurogenesis occurs primarily in the SVZ of the lateral ventricle and in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus (51,52). In addition, one recent study demonstrated that after induction of transient ischemia, Dcx-positive neuroblasts migrate into damaged striatum and differentiate into mature neurons to replace the dead ones (53). However, it was further shown that more than 80% of these newly formed neurons ultimately die, most likely because of unfavorable environmental conditions, including a lack of trophic support and exposure to toxic products from damaged tissues. It was also shown that bFGF can increase the number of neuroblasts migrating from the SVZ (54). Perhaps the notable increase of the expression of bFGF and the promotion of neovascularization induced by MR suppression might contribute to protect Dcx-positive neuroblasts from ischemic damage until they are able to differentiate into new neurons.

Although the neuroprotective effects provided by spironolactone may contribute to a reduction in infarct volume after MCAo, significantly better recovery of motor function was not seen in spironolactone-treated mice after MCAo. We think that because the infarct area was confined to the striatum in our stroke model and the volume of the infarct induced by 20-min MCAo was not large, the significant reduction in infarct volume seen in spironolactone-treated mice was not sufficient to enable evaluation of neurological changes during the acute and subacute phases after MCAo.

It has been reported that aldosterone receptor blockade prevents up-regulation of vascular endothelin-1 and restores endothelial function after disruption by NO in the 11β-HSD2-deficient hypertensive rat (55). A more recent study using spontaneously hypertensive rats also suggests that treatment with eplerenone normalizes the aortic media to lumen ratio and acetylcholine-induced relaxation by enhancing expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and reduces oxidative stress. In addition, aldosterone reportedly contributes to alterations in vessel structure and function by reducing NO availability (56). Because in the present study MR expression in the ischemic striatum was already up-regulated during the acute phase after transient cerebral ischemia, we treated mice with spironolactone 48 h before induction of MCAo to fully examine its effects on brain remodeling during the that phase. However, large vessels, a small number of which are present in the striatum, express MR under normal conditions. Consequently, there is the possibility that spironolactone administered before MCAo might increase cerebral blood flow after transient cerebral ischemia, in part by enhancing production of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in blood vessels, thereby influencing brain remodeling.

It is noteworthy that despite the observed beneficial effects of spironolactone, some evidence suggests that MR activation is necessary for neuroprotection. For instance, MR blockade beginning 1 h before induction of transient global ischemia resulted in increased cell death (57). Moreover, overexpression of human MR in PC12 cells prevented staurosporine- and oxygen/glucose deprivation-induced cell death, and spironolactone attenuated that effect (58). Lai et al. (59) also demonstrated that, compared with wild-type mice, transgenic mice overexpressing MR specifically in their forebrain show significantly reduced neuronal death in the hippocampus, improved spatial memory retention, reduced anxiety, and altered behavioral responses to novelty after transient global cerebral ischemia. Our observation that some neurons in the ischemic striatum were expressing MR 1 d after MCAo suggests MR blockade may have some direct negative effect on ischemic neurons during the hyperacute phase. On postoperative d 2–28, however, the number of MR-expressing neurons declined, and the majority of the cells expressing MR in the ischemic striatum were astrocytes. In addition, our findings indicate that blockade of MR in astrocytes migrating to the ischemic core after MCAo appear to protect damaged neurons via indirect effects. Consequently, although our finding might seem to be inconsistent with that of Lai et al., we think the significance of MR activation to brain remodeling differs in neurons and astrocytes.

There is an interesting report that suggests synaptic function and cellular integrity in the hippocampus can be preserved after unilateral cerebral hypoxia/ischemia (HI) by preventing an ischemia-induced rise in plasma corticosteroid levels (60). HI-induced impairment of synaptic transmission in the CA1 area of the hippocampus is exacerbated by concomitant corticosteroid treatment and alleviated by treatment with the steroid synthesis inhibitor metyrapone. Similarly, degenerative changes in the hippocampus seen after HI are exacerbated by corticosterone but reduced by metyrapone. Kloet and Derijk (61) suggested that although MRs maintain neuronal homeostasis and limit stress-induced disruption, GRs promote recovery after a challenge and storage of the experience, which aids in coping with future encounters. Imbalance in MR/GR-mediated actions compromises homeostatic processes in these neurons, which is thought to lead to maladaptive behavior and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal dysregulation that may, in turn, lead to aberrant metabolism, impaired immune function, and altered cardiovascular control. Our experiments are focused on the effects of MR suppression, mainly in the damaged ischemic striatum. Because GR is more widely expressed in the brain, even under normal conditions, there is a possibility that administration of spironolactone might promote formation of a glucocorticoid-GR complex, which could lead to an imbalance in MR/GR-mediated actions in neurons within nonischemic lesions in areas such as hippocampus. In future experiments, it would be useful to clarify the effects of spironolactone in nonischemic lesions in areas other than the striatum in this animal stroke model.

In conclusion, our findings provide evidence that expression of MR is enhanced during the acute and subacute phases after transient cerebral ischemia, especially in the astrocytes that migrate into the ischemic core. Suppression of MR-mediated signaling by spironolactone induces several beneficial effects on brain remodeling, which appears to significantly reduce infarct size. Spironolactone thus appears to exert potentially therapeutic neuroprotective effects in the ischemic brain.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staffs of Institute of Laboratory Animals, Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto University for animal care, Ms. Akane Nonoguchi for technical assistance, and Ms. Ayumi Ishida and Ms. Shiho Takada for secretarial assistance.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Kyoto University 21st Century Centers of Excellence (COE) Program “Integration of Transplantation Therapy and Regenerative Medicine,” Kyoto University Start-up Grant-in-Aid for young scientists, Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, and the Japan Smoking Foundation, Grant of Regenerative Medicine Realization Project of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, the Health and Labour Sciences Research Grant, Research on intractable diseases from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, and the Research Grant for Cardiovascular Diseases (19C-7) from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare.

Disclosure Statement: The authors of this manuscript have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online April 24, 2008

Abbreviations: BBB, Blood-brain barrier; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; bFGF, basic fibroblast growth factor; Dcx, double-cortin; diHE, dihydroethidium; GDNF, glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor; GFAP, glia fibrillary acidic protein; GR, glucocorticoid receptor; HI, hypoxia/ischemia; 11β-HSD2, 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type II; MCA, middle cerebral artery; MCAo, MCA occlusion; MR, mineralocorticoid receptor; Neu-N, neuron-specific nuclear protein; NGF, nerve growth factor; NO, nitric oxide; PECAM, platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule; ROS, reactive oxygen species; ssDNA, single-strand DNA; SVZ, subventricular zone; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

References

- Sheppard KE, Autelitano DJ 2002 11β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1 transforms 11-dehydrocorticosterone into transcriptionally active glucocorticoid in neonatal rat heart. Endocrinology 143:198–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda Y, Yoneda T, Demura M, Usukura M, Mabuchi H 2002 Calcineurin inhibition attenuates mineralocorticoid-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Circulation 105:677–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brilla CG, Matsubara LS, Weber KT 1993 Anti-aldosterone treatment and the prevention of myocardial fibrosis in primary and secondary hyperaldosteronism. J Mol Cell Cardiol 25:563–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuster GM, Kotlyar E, Rude MK, Siwik DA, Liao R, Colucci WS, Sam F 2005 Mineralocorticoid receptor inhibition ameliorates the transition to myocardial failure and decreases oxidative stress and inflammation in mice with chronic pressure overload. Circulation 111:420–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virdis A, Neves MF, Amiri F, Viel E, Touyz RM, Schiffrin EL 2002 Spironolactone improves angiotensin-induced vascular changes and oxidative stress. Hypertension 40:504–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata K, Rahman M, Shokoji T, Nagai Y, Zhang G-X, Sun G-P, Kimura S, Yukimura T, Kiyomoto H, Kohno M, Abe Y, Nishiyama A 2005 Aldosterone stimulates reactive oxygen species production through activation of NADPH oxidase in rat mesangial cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 16:2906–2912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt B, Zannad F, Remme WJ, Cody R, Castagne A, Perez A, Palensky J, Wittes J, for the Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study Investigators 1999 The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. N Engl J Med 341:709–717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt B, Remme W, Zannad F, Neaton J, Martinez F, Roniker B, Bittman R, Hurley S, Kleiman J, Gatlin M 2003 Eplerenone, a selective aldosterone blocker, in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 348:1309–1321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrysostomou A, Becker G 2001 Spironolactone in addition to ACE inhibition to reduce proteinuria in patients with chronic renal disease. N Engl J Med 345:925–926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato A, Hayashi K, Naruse M, Saruta T 2003 Effectiveness of aldosterone blockade in patients with diabetic nephropathy. Hypertension 41:64–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorrance AM, Osborn HL, Grekin R, Webb RC 2001 Spironolactone reduces cerebral infarct size and EGF-receptor mRNA in stroke-prone rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 281:944–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwanami J, Mogi M, Okamoto S, Gao X-Y, Li J-M, Min L-J, Ide A, Tsukuda K, Iwai M, Horiuchi M 2007 Pretreatment with eplerenone reduces stroke volume in mouse middle cerebral artery occlusion model. Eur J Pharmacol 566:153–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorrance AM, Rupp NC, Nogueira EF 2006 Mineralocorticoid receptor activation causes cerebral vessel remodeling and exacerbates the damage caused by cerebral ischemia. Hypertension 47:590–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roland BL, Krozowski ZS, Funder JW 1995 Glucocorticoid receptor, mineralocorticoid receptors, 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-1 and -2 expression in rat brain and kidney: in situ studies. Mol Cell Endocrinol 111:R1–R7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reul JMHM, Gesing A, Droste S, Stec ISM, Weber A, Bachmann C, Bilang-Bleuel A, Holsboer F, Linthorst ACE 2000 The brain mineralocorticoid receptor: greedy for ligand, mysterious in function. Eur J Pharmacol 405:235–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han F, Ozawa H, Matsuda KI, Lu H, De Kloet ER, Kawata M 2007 Changes in the expression of corticotrophin-releasing hormone, mineralocorticoid receptor and glucocorticoid receptor mRNAs in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus induced by fornix transection and adrenalectomy. J Neuroendocrinol 19:229–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longa EZ, Weinstein PR, Carlson S, Cummins R 1989 Reversible middle cerebral artery occlusion without craniectomy in rats. Stroke 20:84–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyashita K, Itoh H, Arai H, Suganami T, Sawada N, Fukunaga Y, Sone M, Yamahara K, Yurugi-Kobayashi T, Park K, Oyamada N, Sawada N, Taura D, Tsujimoto H, Chao T-H, Tamura N, Mukoyama M, Nakao K 2006 The neuroprotective and vasculo-neuro-regenerative roles of adrenomedullin in ischemic brain and its therapeutic potential. Endocrinology 147:1642–1653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Gasparo M, Joss U, Ramjoue HP, Whitebread SE, Haenni H, Schenkel L, Kraehenbuehl C, Biollaz M, Grob J, Schmidlin J, Wieland P, Wehrli HU 1987 Three new epoxy-spironolactone derivatives: characterization in vivo and in vitro. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 240:650–656 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teramoto T, Qiu J, Plumier JC, Moskowitz MA 2003 EGF amplifies the replacement of parvalbumin-expressing striatal interneurons after ischemia. J Clin Invest 111:1125–1132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akishima Y, Akasaka Y, Ishikawa Y, Lijun Z, Kiguchi H, Ito K, Itabe H, Ishii T 2005 Role of macrophage and smooth muscle cell apoptosis in association with oxidized low-density lipoprotein in the atherosclerotic development. Mod Pathol 18:365–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwai M, Liu H-W, Chen R, Ide A, Okamoto S, Hata R, Sakanaka M, Shinichi T, Horiuchi M 2004 Possible inhibition of focal cerebral ischemia by angiotensin II type 2 receptor stimulation. Circulation 110:843–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Jun K, Xie L, Childs J, Mao XO, Logvinova A, Greenberg DA 2003 VEGF-induced neuroprotection, neurogenesis, and angiogenesis after focal cerebral ischemia. J Clin Invest 111:1843–1851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobi J, Tam BYK, Wu G, Hoffman J, Cooke JP, Kuo CJ 2004 Adenoviral gene transfer with soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptors impairs angiogenesis and perfusion in a murine model of hindlimb ischemia. Circulation 110:2424–2429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montandon G, Kinkead R, Lomenech A-M, Bairam A, Guenard H 2005 Heterogeneity of brainstem blood flow response to hypoxia in the anesthetized rat. Respir Physiol Neurol 147:117–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZG, Zhang L, Croll SD, Chopp M 2002 Angiopoietin-1 reduces cerebral blood vessel leakage and ischemic lesion volume after focal cerebral embolic ischemia in mice. Neuroscience 113:683–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai T, Johnson KJ, Murozono M, Sakai K, Magnuson MA, Wieloch T, Cronberg T, Isshiki A, Erickson HP, Fassler R 2001 Plasma fibronectin supports neuronal survival and reduces brain injury following transient focal cerebral ischemia but is not essential for skin-wound healing and hemostasis. Nat Med 7:324–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers DC, Campbell CA, Stretton JL, Mackay KB 1997 Correlation between motor impairment and infarct volume after permanent and transient middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat. Stroke 28:2060–2066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BJ, Roberts DJ 1968 The quantitative measurement of motor incoordination in native mice using an accelerating rotarod. J Pharm Pharmacol 20:641–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Wang H, Xu L, Rozanski DJ, Sugawara T, Chan PH, Trzaskos JM, Feuerstein GZ 2003 Significant neuroprotection against ischemic brain injury by inhibition of the MEK1 protein kinase in mice: exploration of potential mechanism associated with apoptosis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 304:172–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitesall SE, Hoff JB, Vollmer AP, D'Alecy LG 2004 Comparison of simultaneous measurement of mouse systolic arterial blood pressure by radiotelemetry and tail-cuff methods. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 286:2408–2415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, Weiss JM, Schwartz LS 1968 Selective retention of corticosterone by limbic structures in rat brain. Nature 220:911–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreutzberg GW 1996 A sensor for pathological events in the CNS. Trends Neurosci 19:312–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trendelenberg George, Dirnagl Ulrich2005 Neuroprotective role of astrocytes in cerebral ischemia: focus on ischemic preconditioning. Glia 51:307–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopalan S, Duquaine D, King S, Pitt B, Patel P 2002 Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonism in experimental atherosclerosis. Circulation 105:2212–2216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N, Komine-Kobayashi M, Tanaka R, Liu M, Mizuno Y, Urabe T 2005 Edaravone reduces early accumulation of oxidative products and sequential inflammatory responses after transient focal ischemia in mice brain. Stroke 36:2220–2225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reul JM, de Kloet ER 1985 Two receptor systems for corticosterone in rat brain: microdistribution and differential occupation. Endocrinology 117:2505–2511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes MC, Yau JLW, Kotelevtsev Y, Mullins JJ, Seckl JR 2003 11β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases in the brain: two enzymes two roles. Ann NY Acad Sci 1007:357–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis E, MacKenzie SM 2003 Extra-adrenal production of corticosteroids. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 30:437–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong EYH, Herbert J 2005 Roles of mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptors in the regulation of progenitor proliferation in the adult hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci 22:785–792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funder JW 2005 RALES, EPUHESUS and redox. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 93:121–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speliotes EK, Caday CG, Do T, Weise J, Kowall NW, Flinklestein SP 1996 Increased expression of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) following focal cerebral infarction in the rat. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 39:31–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Li Y, Zhang R, Katakowski M, Gautam SC, Xu Y, Lu M, Zhang Z, Chopp M 2004 Combination therapy of stroke in rats with a nitric oxide donor and human bone marrow stromal cells enhances angiogenesis and neurogenesis. Brain Res 1005:21–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akaneya Y, Enokido Y, Takahashi M, Hatanaka H 1993 In vitro model of hypoxia: basic fibroblast growth factor can rescue cultured CNS neurons from oxygen derived cell death. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 13:1029–1032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng B, Mattson MP 1991 NGF and bFGF protect rat hippocampal and human cortical neurons against hypoglycemic damage by stabilizing calcium homeostasis. Neuron 7:1–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark R, Keller J, Kruman I, Mattson M 1997 Basic FGF attenuates fl-peptide-induced oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and impairment of Na+/K+ ATP activity in hippocampal neurons. Brain Res 756:205–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho A, Blum M 1997 Regulation of astroglial-derived dopaminergic neurotrophic factors by interleukin-1β in the striatum of young and middle-aged mice. Exp Neurol 148:348–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ay I, Sugimori H, Finklestein SP 2001 Intravenous basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) decreases DNA fragmentation and prevents downregulation of Bcl-2 expression in the ischemic brain following middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. Mol Brain Res 87:71–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman J, Shing Y 1992 Angiogenesis. J Biol Chem 267:10931 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupinsky J, Kaluza J, Kumar P, Kumar S, Wang JM 1994 Role of angiogenesis in patients with cerebral ischemic stroke. Stroke 25:1794–1798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage FH, Ray J, Fisher LJ 1995 Isolation, characterization, and use of stem cells from the CNS. Annu Rev Neurosci 18:159–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luskin MB, Zigova T, Soteres BJ, Stewart RR 1997 Neuronal progenitor cells derived from the anterior subventricular zone of the neonatal rat forebrain continue to proliferate in vitro and express a neuronal phenotype. Mol Cell Neurosci 8:351–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvidsson A, Collin T, Kirik D, Kokaia Z, Lindvall O 2002 Neuronal replacement from endogenous precursors in the adult brain after stroke. Nat Med 8:963–970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn GH, Winkler J, Kempermann G, Thal LJ, Gage FH 1997 Epidermal growth factor and fibroblast growth factor-2 have different effects on neural progenitors in the adult rat brain. Neuroscience 17:5820–5829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quaschning T, Ruschitzka F, Shaw S, Lüscher TF 2001 Aldosterone receptor antagonism normalized vascular function in liquorice-induced hypertension. Hypertension 37:801–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz-Rosa D, Oubina MP, Cediel E, De las Heras N, Araquoncillo P, Bajfaqon G, Cachofeiro V, Lahera V 2005 Eplerenone reduces oxidative stress and enhances eNOS in SHR: vascular functional and structural consequences. Antioxid Redox Signal 7:1294–1301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macleod MR, Johansson I-M, Soderstrom I, Lai M, Gido G, Wieloch T, Seckl JR, Olsson T 2003 Mineralocorticoid receptor expression and increased survival following neuronal injury. Eur J Neurosci 17:1549–1555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai M, Seckl J, Macleod M 2005 Overexpression of the mineralocorti-coid receptor protects against injury in PC12 cells. Mol Brain Res 135:276–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai M, Horsburgh K, Bae S-E, Carter RN, Stenvers DJ, Fowler JH, Yau JL, Gomez-Sanchez CE, Holmes MC, Kenyon CJ, Seckl JR, Macleod MR 2007 Forebrain mineralocorticoid receptor overexpression enhances memory, reduces anxiety and attenuates neuronal loss in cerebral ischaemia. Eur J Neurosci 25:1832–1842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krugers HJ, Maslam S, Korf J, Joels M 2000 The corticosterone synthesis inhibitor metyrapone prevents hypoxia/ischemia-induced loss of synaptic function in the rat hippocampus. Stroke 31:1162–1172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Kloet ER, Derijk R 2004 Signaling pathways in brain involved in predisposition and pathogenesis of stress-related disease: genetic and kinetic affecting the MR/GR balance. Ann NY Acad Sci 1032:14–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]