Abstract

Testicular steroids during midgestation sexually differentiate the steroid feedback mechanisms controlling GnRH secretion in sheep. To date, the actions of the estrogenic metabolites in programming neuroendocrine function have been difficult to study because exogenous estrogens disrupt maternal uterine function. We developed an approach to study the prenatal actions of estrogens by coadministering testosterone (T) and the androgen receptor antagonist flutamide, and tested the hypothesis that prenatal androgens program estradiol inhibitory feedback control of GnRH secretion to defeminize (advance) the timing of the pubertal increase in LH. Pregnant sheep were either untreated or treated with T, dihydrotestosterone (DHT) (a nonaromatizable androgen), or T plus flutamide from d 30–90 of gestation. To study the postnatal response to steroid negative feedback, lambs were gonadectomized and estradiol-replaced, and concentrations of LH were monitored in twice-weekly blood samples. Although T and DHT produced penile and scrotal development in females, the external genitalia of T plus flutamide offspring remained phenotypically female, regardless of genetic sex. Untreated females and females and males treated with T plus flutamide exhibited a pubertal increase in circulating LH at 26.4 ± 0.5, 26.0 ± 0.7, and 22.4 ± 1.6 wk of age, respectively. In females exposed to prenatal androgens, the LH increase was advanced (T: 12.0 ± 2.6 wk; DHT: 15.0 ± 2.6 wk). These results demonstrate the usefulness of combining T and antiandrogen treatments as an approach to increasing prenatal exposure to estradiol. Importantly, the findings support our hypothesis that prenatal androgens program sensitivity to the negative feedback actions of estradiol and the timing of neuroendocrine puberty.

IN FEMALE MAMMALS, GnRH secretion is intricately controlled by the feedback actions of ovarian steroid hormones to produce the patterns of pituitary gonadotropin secretion underlying the maintenance of ovarian cyclicity and fertility. According to our working hypothesis (1), four feedback mechanisms operate in the female: 1) the negative feedback action of estradiol regulating the tonic secretion of GnRH, 2) the positive feedback action of estradiol that produces a preovulatory surge of GnRH, 3) the negative feedback action of progesterone controlling tonic secretion of GnRH, and 4) the blocking action of progesterone to inhibit the positive feedback action of estrogen on GnRH secretion. Furthermore, we propose that sexual differentiation of reproductive neuroendocrine function parallels the process by which components of the internal and external genitalia are either masculinized by fetal testosterone (T) or defeminized by other testicular factors. In the absence of testicular secretions (i.e. in the female), the androgen-dependent portion of the internal genitalia regresses, and the remaining internal and external genitalia develop into those of the female. Central to the hypothesis is that the neural circuits associated with the four steroid feedback controls of GnRH secretion are inherent in the developing female, but, in the male, their sensitivity is reduced during development by the organizing actions of testicular steroids. Thus, the male hypothalamus is defeminized, and only the negative feedback action of estradiol remains to regulate tonic secretion of GnRH and reproductive function in the male. For clarity, we consider the male GnRH neuronal system to be defeminized (rather than masculinized) because the preexisting, default circuits have been rendered insensitive or less sensitive to steroid hormones, but no other circuits appear to have been added.

In precocial mammalian species like the sheep, sexual differentiation of reproductive neuroendocrine function and differentiation of the internal and external genitalia occur before birth. In the sheep, the broad critical period for this differentiation is between d 30 and 90 of the 147-d gestation (2,3,4). This is based on several studies in which administration of excess androgens during this portion of pregnancy results in female offspring with varying degrees of anatomical virilization and reproductive neuroendocrine and ovarian dysfunction. Females exposed to T prenatally exhibit a precocial decrease in sensitivity to the negative feedback action of estradiol (5,6), reduced sensitivity to the negative feedback control of GnRH secretion by estradiol (7), disruption of the positive feedback control of the GnRH surge mechanism by estradiol (1,5,6,8,9,10,11,12,13,14), decreased sensitivity to the progesterone negative feedback control of tonic LH secretion (15), multifollicular ovaries (16), depletion of ovarian follicle reserves (17) and follicular persistence (18), and deterioration of ovarian function with increasing age (13,19).

Exposure of females in utero to exogenous T is often referred to as prenatal “androgenization,” but this is a misnomer because T can be metabolized to estrogens as well as to other androgens. Thus, it is necessary to examine the effects of each type of metabolite both individually and in combination to understand fully which steroid or steroid combination is responsible for programming various aspects of reproductive function. To date, the role of estrogens (or the estrogenic metabolites of androgens) in programming neuroendocrine feedback controls has not been studied directly in the sheep model because of the difficulty in delivering sufficient quantities of estradiol to the developing fetus without disrupting maternal uterine function (Foster, D. L., unpublished data).

The organizational actions of estrogens in programming neuroendocrine function have been studied in altricial species, such as the rat, in which a portion of the critical period for sexual differentiation is known to occur after birth (20). In the rat, administration of T or estradiol to female rats within a few days after birth masculinizes brain morphology (21), sexual behavior (22), and the LH surge response to estradiol (23,24). Similarly, removal of T by neonatal castration prevents differentiation of sexual behavior and the GnRH surge mechanism in males (24). More recent evidence suggests that during the period of prenatal development in the rat that is characterized by increased T production in male fetuses, administration of T or dihydrotestosterone (DHT) will defeminize the GnRH surge mechanism in female offspring and increase the frequency of LH pulses in ovariectomized adults (25). Foecking et al. (25) suggest that activation of either androgen receptors during late gestation or estrogen receptors (ERs) during early postnatal life results in disruption of the estradiol positive feedback mechanism, perhaps via different signaling pathways. Thus, even in the rat model, our current understanding of the role of androgens and estrogens in organizing one of the steroid feedback controls of GnRH secretion (i.e. the surge response to estradiol) is still evolving.

In the sheep model, the complexity of the androgens vs. estrogens question is further compounded by expanding studies of the organizational actions of prenatal steroids on neuroendocrine function to include other steroid feedback controls. Inferences about the steroid(s) responsible for defeminization of the GnRH surge mechanism have been made using the subtractive approach in which the consequences of prenatal T treatment on female reproductive function are compared with those of prenatal treatment with DHT, a nonaromatizable androgen. Prenatal treatment of females with T (androgenic and estrogenic actions) disrupts or abolishes the LH surge response to late follicular phase concentrations of estradiol, but prenatal DHT treatment (androgenic actions only) does not (12). Thus, it is reasonable to conclude that the positive feedback control of GnRH secretion by estradiol is programmed by prenatal estrogens occurring from T exposure, but not DHT exposure. However, it remains possible that organizing actions of both androgens and estrogens are required to defeminize the GnRH surge mechanism.

The actions of androgens alone in programming sensitivity to estradiol negative feedback and the control of tonic secretion of GnRH in the sheep have also been examined using this subtractive approach. Prenatal treatment of developing females with either T or DHT results in a reduction in sensitivity to estradiol negative feedback that occurs earlier in postnatal life than in untreated females (12). An important role for this feedback control in regulating tonic secretion of GnRH during development is to time the pubertal increase in circulating LH that initiates puberty. In the sheep, sensitivity to estradiol negative feedback decreases much earlier in males than females (26). More specifically in the male, this results in an increased frequency of LH pulses, higher circulating concentrations of gonadotropins, and increased gonadal activity beginning at 10 wk of age. In contrast, in the female these indices of puberty do not begin until 25–35 wk of age (27). Thus, in females treated with the pure androgen (DHT), the precocial reduction in sensitivity to estradiol negative feedback and increase in circulating LH provide initial evidence that this developmental aspect of reproductive neuroendocrine function is programmed by prenatal androgens. Yet, the timing of the increase in DHT-treated females was not identical to that of T-treated females, raising the possibility that some estrogen action is required, as we have mentioned could be the case for defeminization of the GnRH surge mechanism.

Additional approaches are needed as a method of increasing the availability of prenatal estrogens alone. One method is to eliminate the androgenic actions of T and DHT while sparing T availability for aromatization to estradiol. This was done in the present study, in which we evaluated the prenatal actions of estrogens alone by coadministration of T and the nonsteroidal androgen receptor antagonist flutamide during the critical period for sexual differentiation. This combination of treatments was designed to provide T that can be aromatized to estradiol by the developing female fetus, while blocking the androgenic actions of the exogenous T (or its DHT metabolite) by concomitant treatment with flutamide. In addition, other experimental groups were added for a more complete study. Untreated females and females exposed to excess prenatal T or DHT were included, and males born to mothers treated with T plus the antiandrogen were also included to evaluate the effectiveness of flutamide treatment. Validating this new approach to increasing exposure to estrogens in the developing female requires that we both confirm the inhibition of the androgenic actions of the exogenous T and that we provide evidence for exposure to the estrogenic metabolites. Because the organizational effects of prenatal androgens are readily observed early in postnatal life in the morphology of the external genitalia and the timing of the pubertal decrease in sensitivity to estradiol negative feedback control of GnRH secretion, the first requirement regarding the effectiveness of the antiandrogen treatment is addressed in this initial report. Experimental evidence for prenatal exposure to estrogens is not yet available because these studies are being conducted later in development, and will include postmortem tissue collection and analysis.

To assess developmental changes in sensitivity to inhibitory steroid feedback, we used an experimental model that is well characterized in our laboratory, one in which the gonads are removed, and steroid feedback is maintained at a constant level by an estradiol implant. This model reveals the marked increase in circulating concentrations of LH when sensitivity to estradiol negative feedback decreases at puberty. Based on our working hypothesis that androgens program the negative feedback control of tonic GnRH secretion by estradiol, and the critical role this feedback mechanism plays in the timing of puberty in the sheep, we predicted that the pubertal increase in LH secretion (due to decreased sensitivity to estradiol negative feedback) would not be defeminized in either male or female lambs with prenatal exposure to estrogen alone (T plus flutamide). Prenatal exposure to excess androgens from either T or DHT would advance the age of the pubertal increase in LH. As an indicator of the efficacy of the antiandrogenic action of flutamide, the external genitalia of T plus flutamide-treated males and females were evaluated to assess if the antiandrogen treatment was sufficient to prevent virilization by endogenous and exogenous androgens.

Materials and Methods

Animals and prenatal treatments

Female Suffolk sheep (n = 48, proven breeders, at least 2 yr of age) were maintained outdoors at the Reproductive Sciences Program Sheep Research Facility at the University of Michigan with access to both open and covered pen areas. The sheep were fed a daily ration of alfalfa hay and pellets; water was available ad libitum. Breeder males were housed with the females; marking paint was applied daily to the males’ chests, and mating was detected by the presence of paint marks transferred to the females during copulation. Mated females were stratified by body weight (BW) and were then randomly assigned to one of four treatment groups such that the distributions of BW were similar in all groups. The four groups were control [no treatment, n = 11, BW (mean ± sem) = 86.3 ± 5.1 kg], T treated [100 mg T propionate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) twice a week, n = 14, BW = 83.9 ± 4.5 kg], DHT treated [100 mg DHT (Steraloids, Newport, RI), twice a week, n = 13, BW = 83.4 ± 3.6 kg], and T plus flutamide treated [100 mg T twice a week plus 15 mg/kg flutamide (Sigma-Aldrich) daily, n = 12, BW = 81.2 ± 3.8 kg]. T and DHT were dissolved in corn oil (50 mg/ml) and injected im; flutamide was dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (400 mg/ml) and injected sc. Treatments were administered from d 30–90 of the 147-d gestation period. The dose and route of administration of flutamide were based on a similar study of prenatal treatments in the monkey (30 mg/kg twice daily) (28) with adjustments made for the larger body size and expected lower clearance rate of the drug in the sheep. The University Committee for the Use and Care of Animals at the University of Michigan approved the protocol for all animal care and experimental procedures.

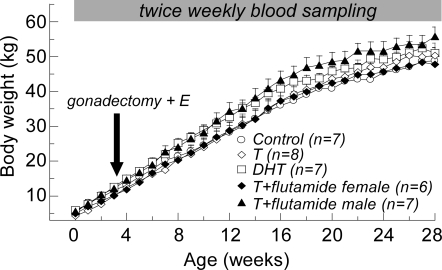

Lambs (eight control females, ten T females, eight DHT females, eight T plus flutamide females, and eight T plus flutamide males) were born in the spring between March 25 and April 11, 2006 (mean ± sem: April 2 ± 0.7 d). All lambs were weighed and measured within 2 d of birth. Body measurements included spinal column length, femur length, head circumference, dorsal head length (nose to base of skull), chest circumference, shoulder height, anonavel distance, anogenital distance, and scrotal length and width (29). BWs were measured weekly throughout the study (Fig. 1). Before the completion of the study, one or two lambs from each treatment group died due to disease or injury; the final number of individuals in each group was seven control, nine T, seven DHT, and six T plus flutamide females, and seven T plus flutamide males. None of the females in the control or T-treated groups were siblings, the DHT group included one set of female twins, and the T plus flutamide groups included one set of female twins and one set of male twins.

Figure 1.

Postnatal experimental treatments and body growth (mean + sem) in female sheep treated prenatally with T, DHT, or T plus flutamide, and male lambs treated prenatally with T plus flutamide.

Postnatal treatments

Lambs were weaned at 8 wk of age, and thereafter maintained outdoors with access to water ad libitum and a diet of alfalfa hay and commercial alfalfa pellets (Shur-Gain, Elma, NY) supplemented by vitamins and minerals. To standardize the hormonal milieu, females and T plus flutamide males were gonadectomized at 3–4 wk of age under ketamine (20 mg/kg, im) and xylazine (0.1–0.2 mg/kg, im) anesthesia. Ovaries were removed via a midline abdominal incision; testes were removed via a cutaneous incision in the mammary region (see Results for description of testes location in T plus flutamide males). At the time of surgery, animals were implanted with a small sc capsule containing crystalline estradiol to maintain a constant steroid feedback signal. The capsule consisted of SILASTIC brand silicon tubing (OD = 0.46 cm, id = 0.34 cm; Dow Corning Corp., Midland, MI) packed with a 3-cm column of crystalline 17β-estradiol (Sigma-Aldrich), and sealed with SILASTIC brand adhesive Type A (Dow Corning Corp.) Implants of this size produce chronic low-circulating concentrations of estradiol (<3–5 pg/ml) (26). This neuroendocrine model allows for detection of the developmental increase in LH secretion reflecting the decrease in sensitivity to estradiol negative feedback during puberty (27) that coincides with the onset of gametogenesis and steroidogenesis in gonad-intact males and females (30).

Blood sampling and LH assay

Jugular blood samples (2–3 ml) were collected twice weekly by venipuncture into heparinized tubes. Plasma was separated by centrifugation and stored at −20 C until assayed for LH. Circulating concentrations of LH were measured in duplicate 20- to 200-μl aliquots of serum using modifications (31,32) of an RIA developed by Niswender et al. (33). Assay sensitivity, defined as two sd values from the buffer control, averaged 0.48 ± 0.03 ng/ml National Institutes of Health LH-S12 for 200 μl serum (n = 10 assays). Intraassay coefficients of variation calculated from six replicates of three standard sera binding at 29, 50, and 83% of buffer controls averaged 2.8, 3.6, and 14.6%, respectively. Interassay coefficients of variation for the same standards were 1.8, 4.2, and 8.4%, respectively. The limit of assay sensitivity was assigned to those samples in which the concentration of LH was below the assay sensitivity.

Data analysis

For analysis of morphometric data, the mother was defined as the experimental unit, and measures from same sex siblings (twins) were averaged before being included in the analysis for the treatment group. A ratio of the anogenital distance to the anonavel distance was used to quantify virilization of the external genitalia. Differences among treatment groups in the mean of this ratio and other body measures were compared using ANOVA.

Maturation of the reproductive neuroendocrine system was evaluated using a criterion previously established in our laboratory (34). The onset of the pubertal increase in LH was defined as the first of at least six consecutive twice-weekly samples in which the concentration of LH was greater than 1 ng/ml. Differences in the age of the pubertal increase in LH were compared using ANOVA. All data are expressed as mean ± sem; statistical significance for all analyses was defined as P < 0.05.

Results

Reproductive anatomy and morphometrics

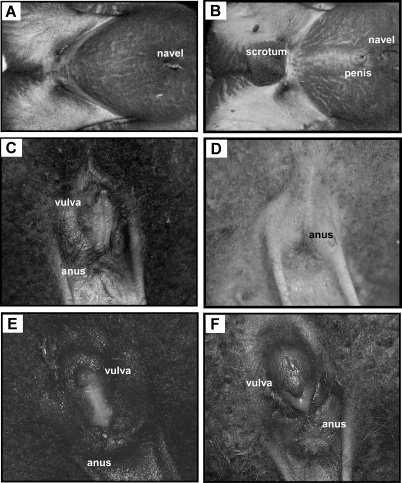

The external genitalia of all females prenatally treated with T or DHT were virilized having a fully developed penis and empty scrotum, and closely resembling the genitalia of a normal male (Fig. 2B). However, some variability was noted in DHT-treated females in which the scrotal tissue was partially split into a heart-shaped sac (one of eight females), or completely divided into left and right sacs (seven of eight females). For quantifying scrotal length and width in females with split scrota, the lengths of the two halves were averaged, and the widths were summed. Additional variability in DHT-treated females was evident in three lambs born to two different mothers (i.e. includes one set of twins) in which the penis was located caudal to the scrotum.

Figure 2.

Photographs of the ventral abdomen of untreated female (A) and male (B) lambs showing the location of the navel (with umbilical remnant attached) and male external genitalia (B). Close-up views of the perineal region (the top of the photograph is ventral) of the untreated female (C) and male (D) showing the location of the female external genitalia (C). The perineal regions of a female (E) and male (F) lamb treated prenatally with T plus flutamide are similar to that of an untreated female, with no evidence of virilization of the external genitalia. The slightly bulbous appearance of the clitoris and surrounding tissue in F was noted in both males and females in the T plus flutamide treatment group.

The external genitalia of all male and female lambs treated prenatally with T plus flutamide were phenotypically female (Fig. 2, A, C, E, and F) with no evidence of any penile or scrotal development. In some of the T plus flutamide lambs, the clitoris and surrounding vulva appeared swollen or bulbous, but this was observed in both males (two of eight) and females (four of eight), and was not indicative of genetic sex. Testes in T plus flutamide males had descended through the body wall, but they were not immediately evident due to the lack of a scrotum. However, they could be palpated beneath the skin in the mammary area, slightly medial to the teat (Fig. 3). Unexpected deaths of one male (1 d after birth) and one female (at 26 wk of age) in this treatment group provided only a limited opportunity for gross examination of the internal genitalia. In the female there was no evidence at necropsy of the development of androgen-dependent Wolffian duct structures. In the necropsied male, the epididymides and vasa deferentia were present, although the length of the spermatic cords and urethra were considerably shorter than normal due to the absence of a scrotum or penis. Similar observations were made at the ovariectomies and castrations, although the full extent of the reproductive tracts was not exposed during surgery.

Figure 3.

Location of the testes in the mammary area of a male lamb treated prenatally with T plus F (the top of the photograph is the anterior direction). The testis on the right is displaced by pressure applied to the skin anterolateral to the nipple. The photograph was taken at orchidectomy at 4 wk of age during which a small (∼2.5 cm) incision was made in the skin just lateral to each nipple, and each testis was exteriorized and removed after ligation of the spermatic cord.

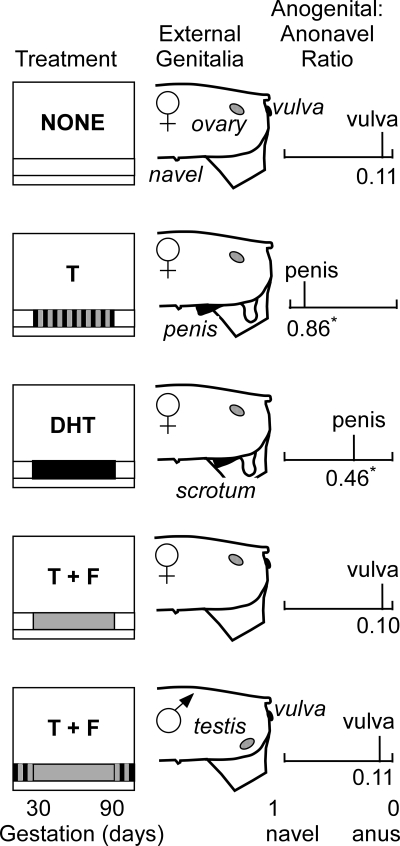

Anonavel distance did not differ relative to prenatal treatment. Anogenital distance was significantly (P < 0.001) greater in T- and DHT-treated females than in control females or T plus flutamide females and males. Thus, the ratio of anogenital distance to anonavel distance was significantly greater in T- and DHT-treated females (0.86 ± 0.01 and 0.46 ± 0.08) than in control females (0.10 ± 0.01) (Fig. 4). The mean ratio for DHT-treated females includes data from the three females with a penis located posterior to the base of the scrotum (mean anogenital to anonavel ratio for these three females was 0.16 ± 0.04). The anogenital to anonavel distance ratio in T plus flutamide females (0.10 ± 0.01) and males (0.11 ± 0.01) was not different from control females. Based on length and width measures, the scrotum was smaller (P < 0.02) in the prenatally DHT-treated group (length = 2.09 ± 0.31 cm, width = 1.86 ± 0.20 cm) than in the prenatally T-treated females (length = 2.92 ± 0.08 cm, width = 2.53 ± 0.09 cm). There were no differences among treatment groups in any of the other neonatal measures.

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of prenatal treatments (left panel), gonads and external genitalia (center panel), and the mean anogenital to anonavel distance ratio (right panel) for control female lambs (no prenatal treatment), female lambs treated prenatally with T, DHT, and T plus flutamide (T + F), and male lambs treated prenatally with T plus flutamide. The striped bar for the T treatment represents exposure to both androgenic and estrogenic metabolites; the solid black bar for the DHT treatment represents exposure to only androgens. The solid gray bar for the T plus flutamide treatment groups represents exposure to only the estrogenic metabolites of the exogenous T. The striped bars before and after the prenatal treatment period for T plus flutamide males represent their exposure to both androgens and estrogens from endogenous, testicular sources. Asterisks (*) signify differences (P < 0.05) in the anogenital to anonavel distance ratio compared with control females.

Neuroendocrine puberty

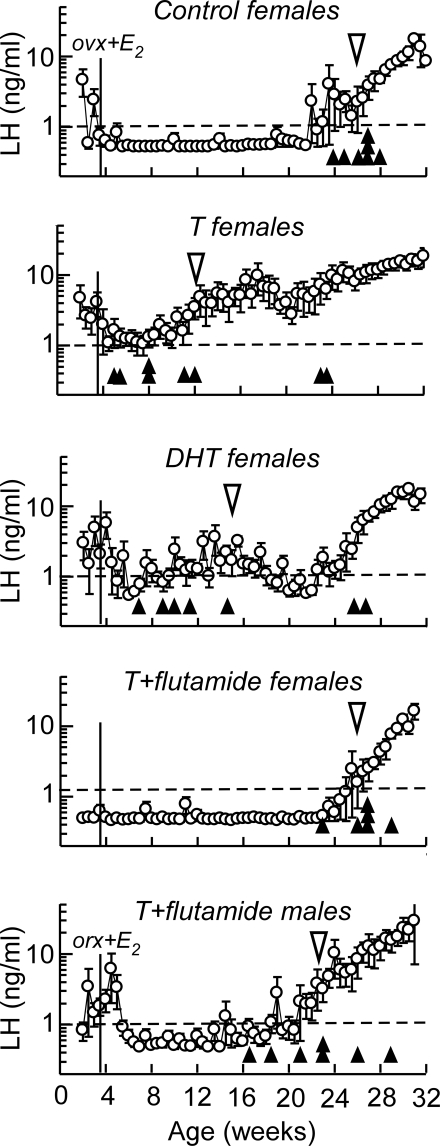

In control females, increasing resistance to estradiol negative feedback and the resultant pubertal increase in circulating concentrations of LH occurred beginning at 26.4 ± 0.5 wk of age (Fig. 5). In T- and DHT-treated females, the onset of the pubertal increase in LH was advanced (P < 0.05) to 12.0 ± 2.6 and 15.0 ± 3.1 wk of age, respectively. Treatment with the antiandrogen prevented this advance, and the timing of neuroendocrine puberty in T plus flutamide-treated females (26.0 ± 0.7 wk of age) and males (22.4 ± 1.6 wk of age) was not different from control females. The age at the pubertal increase in circulating LH was more variable among individuals in the T and DHT treatment groups than the control or T plus flutamide groups. Two females in each of the T or DHT treatment groups did not maintain elevated LH secretion for six consecutive twice-weekly samples until 22–26 wk of age.

Figure 5.

Mean (±sem) circulating concentrations of LH in twice-weekly blood samples collected from gonadectomized and estradiol (E2)-replaced control females, females treated prenatally with T, DHT, and T plus flutamide, and males treated prenatally with T plus flutamide. The open triangle indicates the mean age of puberty characterized by a sustained increase in circulating LH above 1 ng/ml (dotted line). Solid triangles represent the age of puberty for individual animals within each treatment group. The solid, vertical line indicates the age at which the gonads were removed surgically and steroids replaced by a sc estradiol implant. ovx, Ovariectomized; orx, orchidectomized.

Discussion

Steroid hormones play a crucial role during mammalian development to organize the brain, gonads, and internal and external genitalia, such that they function appropriately as either male or female in adult life. Disturbance of the normal, developmental program occurs under natural conditions of the uterine environment, as illustrated by the freemartin effect in which a female calf is masculinized in utero by the presence of a male twin (35), and by uterine positional effects in litter-bearing species (36), whereby females flanked by males in utero are exposed to greater concentrations of testicular steroids than females gestating next to other females. Natural disruptions also stem from genetic variations or mutations associated with pathologies such as maternal or fetal congenital adrenal hyperplasia, androgen receptor insensitivity, or deficiencies in other steroidogenic enzymes. More recently, endocrine disruptors and endocrine mimics have been identified as environmental substances that, when present in sufficient quantities in the maternal circulation, interfere with the process of sexual differentiation or development of the reproductive system (37,38). The brain is arguably the most sensitive and complex target for steroid hormones throughout development, and is essential for driving hypophyseal and gonadal function, and sexual behavior. Therefore, identifying the separate organizing actions of estrogens and androgens (and their potential interactions) is of critical importance to understand fully sexual differentiation of the steroid feedback controls of GnRH secretion, as well as the impact of genetic conditions or environmental contaminants on programming other aspects of adult reproductive function.

The organizing actions of androgens alone have been described from studies using prenatal treatment with the nonaromatizable androgen DHT, and a subtractive approach comparing the consequences of T treatment with those of DHT has been useful in identifying those aspects of sexual differentiation that require estrogens as well as androgens. The present study used T treatment with and without simultaneous antiandrogen as another subtractive approach to characterize the organizing actions of estrogens alone. Previous studies of the effects of the antiandrogen flutamide during prenatal development in large animals have been limited to monkeys (28,39) and hyenas (40,41). This is the first report of prenatal flutamide treatment in sheep, as well as the first developmental study in a large mammalian species that combined the antiandrogen with exogenous T to characterize the role of estrogens in programming neuroendocrine function. Because we lacked information about flutamide in sheep, we adjusted the dose used in the monkey (28) for the larger body size and lower weight-specific metabolic rate of the sheep, and used a dose (15 mg/kg·d) that was slightly less than the amount of flutamide (18–26 mg/kg·d) administered orally in the hyena (40), a species in which naturally high levels of prenatal androgens of maternal origin result in female offspring with masculinized genitalia (42). Some perspective on the endogenous and exogenous concentrations of T present during the prenatal treatment can be gained from a recent study in sheep using the same prenatal T treatment used in the present study. Roselli et al. (43) reported that prenatal treatment produced an average maternal concentration of T of 13.5 ng/ml, with much lower concentrations of T (0.57 ng/ml) measured in umbilical artery samples collected from T-treated fetuses on d 85 of gestation. The concentration of T in samples from untreated male fetuses (0.28 ng/ml) was approximately half of that measured in the T-treated group. Thus, we were optimistic that if our selected dose of flutamide blocked the actions of exogenous T, it would be sufficient to block endogenous androgens in the male as well. The morphology of the external genitalia provided the initial evidence that the flutamide treatment we selected did effectively block the action of both exogenous and endogenous androgens.

The effects of the prenatal treatments on the external genitalia were clear at birth. As expected from earlier studies (4,6,12), the external genitalia of females treated with prenatal T or DHT were masculinized with a well-developed penis and scrotum. The development of these structures was more variable in females treated with DHT than in T-treated females. The majority of the DHT-treated females had an incompletely fused scrotum, and there were three females with the penis located caudal to the scrotum. This suggests that the two androgen treatments are not equivalent in their actions on the undifferentiated tissue. The different anatomical consequences of the two treatments could be related to the increased androgenic potency of DHT, or a possible role for estradiol that was available in T-treated but not DHT-treated females, but neither of these explanations is consistent with the DHT-treated females being less virilized than the T-treated females. A more likely explanation is that there are differences in the way the two steroids are metabolized by the placenta and transferred into the fetal circulation. Finally, it is possible that estrogenic metabolites of DHT exert organizational effects on the genitalia. DHT is a nonaromatizable androgen, but it can be converted to 5α-androstane-3β,17β-diol (or 3βAdiol) by several steroid-metabolizing enzymes (44). Pak et al. (45) recently reported that in a neuronal cell line, DHT and 3βAdiol stimulated the promoter for the neuropeptide arginine vasopressin through the ERβ. Thus, exogenous DHT may not act as a pure androgen in all tissues, particularly those expressing ERβ and capable of converting DHT to 3βAdiol. This possibility should be considered when interpreting the consequences of DHT treatment on masculinization of the genitalia and defeminization of neuroendocrine function.

The external genitalia of all females and males treated prenatally with T plus flutamide were phenotypically female, and the only way to determine sex at birth was by palpating for testes in the mammary area of males. This was our first confirmation of the effectiveness of the flutamide treatment in females at blocking the androgenic actions of the same dose of prenatal T that fully virilized the external genitalia of T-treated females. Furthermore, the antiandrogen treatment also prevented any masculinization of the external genitalia of males in this treatment group. This finding is important because it relates to flutamide blocking the actions of endogenous as well as exogenous androgens during the treatment period. However, treatment with T plus flutamide did not obliterate subsequent testicular function. Although we did not measure circulating concentrations of T in the male lambs, testicular size at neonatal gonadectomy (∼3 cm long and 2 cm in diameter) and the presence of developed, coiled epididymides were indications of steroidogenic activity in the gonads. T plus flutamide males were exposed to their own testicular steroids for the latter portion of gestation (d 91–147) and early postnatal life, which could have supported some testicular and Wolffian duct development. However, androgens during this period did not masculinize the external genitalia. This confirms an earlier study that reported that the critical period for this aspect of sexual differentiation is closed after d 90 of gestation (46).

In addition to directing the development of the internal and external genitalia, prenatal steroids exert an organizing action on the neural circuitry involved with the activational actions of steroid hormones on reproductive neuroendocrine function. Organization of the positive feedback action of estradiol to produce a GnRH and LH surge has been studied extensively, and the current consensus for nonprimate species is that exposure to testicular steroids during a critical period of development renders the surge mechanism inoperative in the male (47). However, studies in the female sheep treated prenatally with lower doses of T (6) report a delay in the surge response to estradiol, rather than its elimination, and a dose-dependent advance in the pubertal increase in LH. These findings suggest that prenatal steroids organize the timing of neuroendocrine responses to steroid feedback, and with anatomical evidence for a block of androgen action in animals treated prenatally with T plus flutamide, we further explored the role of prenatal androgens in programming the timing of puberty. Puberty is the initial time in postnatal life when the coordinated function of the entire reproductive system is first manifest. In many species, including sheep (27), rat (48), human, and rhesus monkey (49), the timing of puberty is sexually differentiated, although whether sexual maturation is earlier in the male or the female is a species-specific phenomenon. Puberty occurs at a younger age in male sheep than female sheep, but this pattern is reversed in the rat, human, and rhesus monkey, in which puberty in females generally occurs earlier in life than in males. These considerations raise the possibility that the default time line for a species is that of the female, and changing the time line to that of a male requires the organizational actions of steroid hormones. One of the earliest indicators of puberty is an increase in the secretion of gonadotropins associated with a decrease in sensitivity of the GnRH system to estradiol negative feedback. With respect to the foregoing hypothesis regarding the default time line for puberty, our previous studies have demonstrated that prenatal T defeminizes the female pattern and results in a precocial increase in LH secretion, similar to that of a normal male (27). In contrast to the precocial increase in LH secretion in the female sheep, a study of female rhesus monkeys exposed to excess T early in gestation shows that menarche is delayed by 4–6 months (50), which is consistent with the later puberty in male primates.

In view of the effects of in utero exposure of females to a nonaromatizable androgen (DHT), one would conclude that defeminization of the timing of puberty is purely an androgenic effect. Thus, one would predict that blocking androgenic actions during development in the male would prevent defeminization of the timing of puberty by testicular steroids. Indeed, in the monkey, in which puberty occurs earlier in the female, prenatal treatment with the antiandrogen flutamide early in gestation accelerated pubertal development in the male based upon several indices: the LH response to a GnRH challenge, circulating concentrations of LH and T during the pubertal breeding season, and earlier testicular development (39). In our present study of the sheep model, prenatal flutamide treatment alone was not studied because our objective was to examine the potential for differential programming effects of androgens and estrogens in the female. According to our working hypothesis, the development of the steroid feedback mechanisms required for female reproductive function does not require organizational actions of androgens, so an antiandrogen-only treatment would be of little value in achieving our objectives in the female. However, males treated prenatally with an antiandrogen would yield important information regarding the timing of puberty, and one would expect that their own endogenous testicular steroids could not defeminize puberty in the presence of an antiandrogen. Indeed, we included males born in the T plus flutamide treatment group in the present study to test simultaneously the efficacy of the antiandrogen treatment and the role of prenatal androgens in the timing of puberty. This design obviated the need for an antiandrogen-only treatment group. The results from the male treated with T plus flutamide provide further evidence for the conclusion that prenatal androgens program hypothalamic sensitivity to the negative feedback actions of estradiol because the timing of puberty was delayed.

In the female, neuroendocrine puberty was advanced in ovariectomized, estradiol-replaced T- and DHT-treated females, indicating that prenatal androgens defeminized the timing of puberty. This confirmed earlier findings (4,12). The precocial increase in secretion of LH in these two groups also supports our hypothesis that estradiol negative feedback regulation of tonic secretion of LH is defeminized by prenatal androgens, although we did not characterize pulsatile patterns of LH secretion in response to increasing concentrations of estradiol in this study. Higher concentrations of LH in twice-weekly samples between 3 and 5 wk of age from prepubertal T- and DHT-treated females, and T plus flutamide-treated males (Fig. 5) raise the possibility that sensitivity to estradiol negative feedback was lower in these groups. However, the highly pulsatile nature of LH secretion, infrequent sampling, and the fact that these samples encompassed the time of gonadectomy and steroid replacement may explain these transient increases. When T treatment was combined with an antiandrogen, the pubertal increase in LH in both males and females was not advanced, indicating that the negative feedback control of GnRH secretion was not defeminized. However, the timing of puberty in individual males (Fig. 5, solid triangles) was more variable than in untreated females or T plus flutamide females, which raises the possibility that endogenous androgens (or estrogenic metabolites of androgens) had some organizational actions outside of the known critical period once flutamide treatment was discontinued.

Based on these findings, prenatal treatment with T plus flutamide is a viable and valuable approach to assessing the role of prenatal estrogens alone in sexual differentiation of reproductive neuroendocrine function in a precocial species. At this stage of understanding, we cannot be entirely certain that the T plus antiandrogen treatment increases the availability of estradiol in the developing female. The finding that prenatal T exposure defeminizes the GnRH surge response to estradiol (11), but prenatal treatment with the nonaromatizable androgen DHT does not (12), provides evidence that exogenous T is aromatized to estradiol in the developing female. However, it is possible that concomitant administration of flutamide interferes with aromatization of T to estradiol. In the rat the neural distribution of aromatase is sexually dimorphic, with higher levels in males than females, and the difference is associated with up-regulation of aromatase activity by T via the androgen receptor (51,52). However, aromatase activity in some areas of the brain is androgen independent (53), and in the female or castrated male, expression of aromatase mRNA in the preoptic area and hypothalamus is reduced by approximately 25–50% of that in an intact or T-replaced male, but it is not eliminated (54). In the sheep, high levels of aromatase have been measured in the fetal hypothalamus on d 50 of gestation, but no sex differences were detected (55). Thus, blocking the androgenic actions of T with flutamide could limit aromatase activity, but it is unlikely that all aromatization was prevented during the prenatal treatment period.

Further studies of the relative roles of androgens and estrogens in programming the positive feedback action of estradiol on the GnRH surge, and the progesterone feedback controls of the tonic and surge modes of GnRH secretion, are in progress in these animals. In addition, morphometric analysis of the ovaries collected at neonatal gonadectomy, sexual behavior during an artificial, hormonally induced estrous cycle, and the consequences of prenatal steroids and flutamide on the GnRH neuronal system and its inputs are currently being investigated. Such studies will not only increase our understanding of the organizing actions of steroid hormones during prenatal development; they will expand the knowledge base for interpreting reproductive dysfunctions in humans and other mammals that may occur spontaneously, or occur as the result of exposure to environmental compounds exerting steroid-like or antisteroidal effects on the developing individual.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. Doug Doop for his conscientious and expert animal care and facility management, Dr. Kim Wallen for his guidance in designing the flutamide treatment, Ms. Judy Ch’ang for her help with gonadectomies and blood sampling, and Ms. Eila Roberts, Ms. Erica LaVire, Ms. Carol Herkimer, Mr. Paul Slotten, Dr. Mohan Manikkam, Ms. Christin Siegele, and Ms. Jodie Woznica for assistance with prenatal treatments and blood sampling.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant P01 HD-44232.

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online May 1, 2008

Abbreviations: 3βAdiol, 5α-Androstane-3β,17β-diol; BW, body weight; DHT, dihydrotestosterone; ER, estrogen receptor; T, testosterone.

References

- Foster DL, Jackson LM, Padmanabhan V 2006 Programming of GnRH feedback controls timing puberty and adult reproductive activity. Mol Cell Endocrinol 254–255:109–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short RV 1974 Sexual differentiation of the brain of the sheep. In: Forest MG, Bertrand J, eds. Endocrinologie sexuelle de la periode perinatale. Vol 32. Paris: INSERM; 121–142 [Google Scholar]

- Clarke IJ, Scaramuzzi RJ, Short RV 1976 Effects of testosterone implants in pregnant ewes on their female offspring. J Embryol Exp Morph 36:87–99 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood RI, Foster DL 1998 Sexual differentiation of reproductive neuroendocrine function in sheep. Rev Reprod 3:130–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood RI, Ebling FJ, I'Anson H, Bucholtz DC, Yellon SM, Foster DL 1991 Prenatal androgens time neuroendocrine sexual maturation. Endocrinology 128:2457–2468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosut SS, Wood RW, Herbosa-Encarnacion CG, Foster DL 1997 Prenatal androgens time neuroendocrine puberty in sheep: effects of dose. Endocrinology 38:1072–1077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarma HN, Manikkam M, Herkimer C, Dell'Orco J, Welch KB, Foster DL, Padmanabhan V 2005 Fetal programming: excess prenatal testosterone reduces postnatal luteinizing hormone, but not follicle-stimulating hormone, responsiveness to estradiol negative feedback in the female. Endocrinology 146:4281–4291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke IJ, Scaramuzzi RJ, Short RV 1976 Sexual differentiation of the brain: endocrine and behavioral response of androgenized ewes to estrogen. J Endocrinol 71:175–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke IJ, Scaramuzzi RJ 1978 Sexual behaviour and LH secretion in spayed androgenized ewes after a single injection of testosterone or estradiol. J Reprod Fertil 52:313–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood RI, Mehta V, Herbosa CG, Foster DL 1995 Prenatal testosterone differentially masculinizes tonic and surge modes of LH secretion in the developing sheep. Neuroendocrinology 62:238–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbosa CG, Dahl GE, Evans NP, Pelt J, Wood RI, Foster DL 1996 Sexual differentiation of the surge mode of gonadotropin secretion: prenatal androgens abolish the gonadotropin-releasing hormone surge in the sheep. J Neuroendocrinol. 8:627–633 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masek KS, Wood RI, Foster DL 1999 Prenatal dihydrotestosterone differentially masculinizes tonic and surge modes of luteinizing hormone secretion in sheep. Endocrinology 140:3459–3466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma TP, Herkimer C, West C, Ye W, Birch R, Robinson JE, Foster DL, Padmanabhan V 2002 Fetal programming: prenatal androgen disrupts positive feedback actions of estradiol but does not affect timing of puberty in female sheep. Biol Reprod 4:924–933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unsworth WP, Taylor JA, Robinson JE 2005 Prenatal programming of reproductive neuroendocrine function: the effect of prenatal androgens on the development of estrogen positive feedback and ovarian cycles in the ewe. Biol Reprod 72:619–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JE, Forsdike RA, Taylor JA 1999 In utero exposure of female lambs to testosterone reduces the sensitivity of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuronal network to inhibition by progesterone. Endocrinology 140:5797–5805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West C, Foster DL, Evans NP, Robinson J, Padmanabhan V 2001 Intrafollicular activin availability is altered in prenatally-androgenized lambs. Mol Cell Endocrinol 185:51–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steckler T, Wang J, Bartol FF, Roy SK, Padmanabhan V 2005 Fetal programming: prenatal testosterone treatment causes intrauterine growth retardation, reduces ovarian reserve and increases ovarian follicular recruitment. Endocrinology 146:3185–3193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steckler T, Manikkam M, Inskeep EK, Padmanabhan V 2007 Developmental programming: follicular persistence in prenatal testosterone-treated sheep is not programmed by androgenic actions of testosterone. Endocrinology 148:3532–3540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch RA, Padmanabhan V, Foster DL, Unsworth WP, Robinson JE 2003 Prenatal programming of reproductive neuroendocrine function: fetal androgen exposure produces progressive disruption of reproductive cycles in sheep. Endocrinology 144:1426–1434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLusky NJ, Naftolin F 1981 Sexual differentiation of the central nervous system. Science 211:1294–1302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breedlove SM 1992 Sexual dimorphism in the vertebrate nervous system. J Neurosci 12:4133–4142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whalen RR, Rezek DL 1974 Inhibition of lordosis in female rats by subcutaneous implant of testosterone, androstenedione or dihydrotestosterone in infancy. Horm Behav 5:125–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, Lieberburg I, Chaptal V, Krey LC 1977 Aromatization: important for sexual differentiation of the neonatal rat brain. Horm Behav 9:249–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz DR, Fleming DE, Rhees RW 1995 The hormone-sensitive early postnatal periods for sexual differentiation of feminine behavior and luteinizing hormone secretion in male and female rats. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 86:227–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foecking EM, Szabo M, Schwartz NB, Levine JE 2005 Neuroendocrine consequences of prenatal androgen exposure in the female rat: absence of luteinizing hormone surges, suppression of progesterone receptor gene expression, and acceleration of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulse generator. Biol Reprod 72:1475–1483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claypool LE, Foster DL 1990 Sexual differentiation of the mechanism controlling pulsatile secretion of luteinizing hormone contributes to sexual differences in the timing of puberty in sheep. Endocrinology 126:1206–1215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster DL, Jackson LM 2006 Puberty in the sheep. In: Neill JD, ed. Knobil and Neill’s physiology of reproduction. 3rd ed. Boston: Elsevier Science; 2127–2176 [Google Scholar]

- Herman RA, Jones B, Mann DR, Wallen K 2000 Timing of prenatal androgen exposure: anatomical and endocrine effects on juvenile male and female rhesus monkeys. Horm Behav 38:52–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manikkam M, Crespi EJ, Doop DD, Herkimer C, Lee JS, Yu S, Brown MB, Foster DL, Padmanabhan V 2004 Fetal programming: prenatal testosterone excess leads to fetal growth retardation and postnatal catch-up growth in sheep. Endocrinology 145:790–798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster DL, Ryan KD 1979 Endocrine mechanisms governing transition into adulthood: a marked decrease in inhibitory feedback action of estradiol on tonic secretion of luteinizing hormone in the lamb during puberty. Endocrinology 105:896–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauger RL, Karsch FJ, Foster DL 1977 A new concept for control of the estrous cycle of the ewe based upon temporal relationships between luteinizing hormone, estradiol, and progesterone in peripheral serum and evidence that progesterone inhibits tonic LH secretion. Endocrinology 101:807–817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebling FJP, Wood RI, Karsch FJ, Vannerson LA, Suttie JM, Bucholtz DC, Schall RE, Foster DL 1990 Metabolic interfaces between growth and reproduction III. Central mechanisms controlling pulsatile luteinizing hormone secretion in the nutritionally growth-limited female lamb. Endocrinology 126:2719–2727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niswender GD, Reicher Jr LE, Midgley AR, Nalbandov AV 1969 Radioimmunoassay for bovine and ovine luteinizing hormone. Endocrinology 84:1166–1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebling FJ, Foster DL 1988 Photoperiod requirements for puberty differ from those for the onset of the adult breeding season in female sheep. J Reprod Fertil 84:283–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padula AM 2005 The freemartin syndrome: an update. Anim Reprod Sci 87:93–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vom Saal FS 1989 Sexual differentiation in litter bearing mammal: influence of sex of adjacent fetuses in utero. J Anim Sci 67:1824–1840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colburn T, vom Saal FS, Soto AM 1993 Developmental effects of endocrine-disrupting chemicals in wildlife and humans. Environ Health Perspect 10:378–384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson CA, Davies DC 2007 The control of sexual differentiation of the reproductive system and brain. Reproduction 133:331–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman RA, Zehr JL, Wallen K 2006 Prenatal androgen blockade accelerates pubertal development in male rhesus monkeys. Psychoneuroendocrinology 31:118–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drea CM, Weldele ML, Forger NG, Coscia EM, Frank LG, Licht P, Glickman SE 1998 Androgens and masculinization of genitalia in the spotted hyaena (Crocuta crocuta). 2. Effects of prenatal antiandrogens. J Reprod Fertil 113:117–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Place J, Holekamp KE, Sisk CL, Weldele ML, Coscia EM, Drea CM, Glickman SE 2002 Effects of prenatal treatment with antiandrogens on luteinizing hormone secretion and sex steroid concentrations in adult spotted hyenas, Crocuta crocuta. Biol Reprod 67:1405–1413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licht P, Frank LH, Pavgi S, Yalcinkaya TM, Siiteri PK, Glickman SE 1992 Hormonal correlates of “masculinization” in female spotted hyaenas (Crocuta crocuta). 2. Maternal and fetal steroids. J Reprod Fertil 95:463–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roselli CE, Stadelman H, Reeve R, Bishop CV, Stormshak F 2007 The ovine sexually dimorphic nucleus of the medial preoptic area is organized prenatally by testosterone. Endocrinology 148:4450–4457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steckelbroeck S, Jin Y, Gopishetty S, Oyesanmi B, Penning TM 2004 Human cytosolic 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases of the aldo-keto reductase superfamily display significant 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase activity: implications for steroid hormone metabolism and action. J Biol Chem 279:10784–10795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pak TR, Chung WC, Hinds LR, Handa RJ 2007 Estrogen receptor-β mediates dihydrotestosterone-induced stimulation of the arginine vasopressin promoter in neuronal cells. Endocrinology 148:3371–3382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbosa CG, Foster DL 1996 Defeminization of the reproductive response to photoperiod occurs early in prenatal development in the sheep. Biol Reprod 54:420–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J 2006 Prenatal programming of the female reproductive neuroendocrine system by androgens. Reproduction 132:529–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda SR, Skinner MK 2006 Puberty in the rat. In: Neill JD, ed. Knobil and Neill’s physiology of reproduction. 3rd ed. Boston: Elsevier Science; 2061–2126 [Google Scholar]

- Plant TM, Witchel S 2006 Puberty in non-human primates and humans. In: Neill JD, ed. Knobil and Neill’s physiology of reproduction. 3rd ed. Boston: Elsevier Science; 2177–2230 [Google Scholar]

- Goy RW, Bercovitch FB, McBrair MC 1988 Behavioral masculinization is independent of genital masculinization in prenatally androgenized female rhesus macaques. Horm Behav 22:552–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roselli CE, Horton, LE, Resko JA 1985 Distribution and regulation of aromatase activity in the rat hypothalamus and limbic system. Endocrinology 117:2471–2477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roselli CE, Resko JA 1984 Androgens regulate brain aromatase activity in adult male rats through a receptor mechanism. Endocrinology 114:2183–2189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roselli CE, Salisbury RL, Resko JA 1987 Genetic evidence for androgen-dependent and independent control of aromatase activity in the rat brain. Endocrinology 121:2205–2210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roselli CE, Abdelgadir SE, Resko JA 1997 Regulation of aromatase gene expression in the adult rat brain. Brain Res Bull 44:351–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roselli CE, Resko JA, Stormshak F 2003 Estrogen synthesis in fetal sheep brain: effect of maternal treatment with an aromatase inhibitor. Biol Reprod 68:370–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]