Abstract

Prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed and the second leading cause of cancer death in men. The androgens-androgen receptor signaling plays an important role in normal prostate development, as well as in prostatic diseases, such as benign hyperplasia and prostate cancer. Accordingly, androgen ablation has been the most effective endocrine therapy for hormone-dependent prostate cancer. Here, we report a novel nuclear receptor-mediated mechanism of androgen deprivation. Genetic or pharmacological activation of the liver X receptor (LXR) in vivo lowered androgenic activity by inducing the hydroxysteroid sulfotransferase 2A1, an enzyme essential for the metabolic deactivation of androgens. Activation of LXR also inhibited the expression of steroid sulfatase in the prostate, which may have helped to prevent the local conversion of sulfonated androgens back to active metabolites. Interestingly, LXR also induced the expression of selected testicular androgen synthesizing enzymes. At the physiological level, activation of LXR in mice inhibited androgen-dependent prostate regeneration in castrated mice. Treatment with LXR agonists inhibited androgen-dependent proliferation of prostate cancer cells in a LXR- and sulfotransferase 2A1-dependent manner. In summary, we have revealed a novel function of LXR in androgen homeostasis, an endocrine role distinct to the previously known sterol sensor function of this receptor. LXR may represent a novel therapeutic target for androgen deprivation, and may aid in the treatment and prevention of hormone-dependent prostate cancer.

PROSTATE IS AN androgen-regulated exocrine gland of the male reproductive system (1). Androgens, including testosterone (T) and dihydrotestosterone (DHT), play an important role in the morphogenesis and physiology of normal prostate (1,2,3). In addition to its normal function, androgen is a risk factor for prostate cancer, the most commonly diagnosed and the second leading cause of cancer death in men (4).

It is generally believed that most of the androgen actions are mediated by the androgen receptor (AR), a member of the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily (5,6). Upon activation by androgens, AR translocates from cytoplasm into the nucleus where it binds to the androgen responsive element (ARE) on target genes and recruits coactivators to facilitate gene regulation. The androgens-AR signaling stimulates a cascade of events that are required for prostate cancer development and progression. As such, the most effective endocrine therapy for prostate cancer has been the androgen ablation. These include surgical or medical castration, as well as the use of antiandrogens (2). Upon androgen withdrawal or antiandrogen treatment, the growth of androgen-dependent prostate cancer cells is reduced, and the cells undergo apoptosis, leading to tumor regression (1).

Other than castration and the use of antiandrogens, an important pathway to metabolically deactivate androgens is through the sulfotransferase (SULT)-mediated sulfonation. SULTs, a family of Phase II drug metabolizing enzymes, catalyze the transfer of a sulfonyl group from the co-substrate 3′-phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphosulfate (PAPS) to the acceptor substrates to form sulfate (SULF) or sulfamate conjugates (7,8,9,10). Sulfonation plays an important role in steroid hormone deactivation because sulfonated hormones often fail to bind to their cognate receptors and, thus, lose their hormonal activities (7,11). Sulfoconjugation also converts lipophilic steroid hormones to amphiphiles, which promotes their excretion. The primary SULT isoform responsible for androgen sulfonation at physiological concentration is believed to be the hydroxysteroid SULT (SULT2A1) (7,12). In humans, SULT2A1 is expressed in steroidogenic organs (adrenal and ovary), androgen-dependent tissue (prostate), tissues of the alimentary tract (stomach, small intestine, and colon), and liver (7). In rodents, Sult2a1/2a9 is predominantly expressed in the liver, although a lower level of its expression is also observed in several other tissues (13).

The potential effect of SULT2A1 on androgen metabolism has been alluded to in previous reports. For instance, the androgen insensitivity in the livers of prepuberty or aged rats was associated with an elevated hepatic expression of Sult2a1 (14), suggesting an important role for Sult2a1 in androgen homeostasis. On the other hand, the expression of SULT2A1 has been down-regulated by androgens (13,15), which may represent a regulatory mechanism to maintain a proper androgenic activity. Despite the potential role of SULT2A1 in androgen metabolism, the implication of SULT2A1 expression and regulation in prostate regeneration and prostate cancer have not been systemically evaluated. In addition to SULT2A1, other androgen metabolizing enzymes have also been implicated in prostate cancer. For example, increased expression of enzymes converting adrenal androgens to T, such as the aldo-keto reductase family 1, member C3, was detected in androgen-independent prostate cancer, which has been proposed to be a potential mechanism by which prostate cancer cells adapt to androgen deprivation (16).

Other than SULT2A1, SULT2B1b may also contribute to androgen sulfation. It has been reported that recombinant SULT2B1b showed sulfonating activity toward T and DHT, although adrenal androgens such as androstenediol and DHEA are better substrates for this enzyme (7,17). The steroid sulfatase (STS) also plays a role in androgen homeostasis. It is believed that the sulfonated androgens could be desulfonated within target tissues, such as the prostate, to be converted into active metabolites. Indeed, STS inhibitors have been explored as anticancer drugs for prostate cancer (18).

The liver X receptors (LXRs), both the α and β-isoforms, are nuclear receptors that can be activated by endogenous cholesterol metabolite oxysterols, such as the 22(R)-hydroxycholesterol (19), as well as synthetic agonists, such as T0901317 (TO1317) (20) and GW3965 (21). LXRs have possessed diverse functions, ranging from cholesterol efflux to lipogenesis and antiinflammation (19,22). For these reasons, LXRs have been explored as a therapeutic target for atherosclerosis, diabetics, and Alzheimer’s disease in animal models (19,22,23,24). More recently, we showed that LXR can promote bile acid detoxification and alleviate cholestasis (25). The anticholestatic effect of LXR was associated with LXR-mediated activation of Sult2a1/2a9, which is also capable of sulfonating and detoxifying bile acids. However, whether or not LXR plays a role in androgen homeostasis is unknown.

In this study we showed that activation of LXR lowered the circulating androgen level in vivo, and inhibited androgen-dependent prostate regeneration and prostate cancer cell growth. We also showed that sulfonated androgens failed to activate AR, and expression of SULT2A1 is both necessary and sufficient to deactivate androgens. We propose that LXR-mediated SULT2A1 activation represents a novel mechanism of androgen deprivation, which may have its utility in developing therapies for hormone-dependent prostate cancers.

Materials and Methods

Animals and prostate regeneration experiment

The creation of fatty acid binding protein (FABP)-viral protein 16 (VP)-LXRα transgenic (TG) mice has been previously described in detail (25). TG mice and their wild-type (WT) littermates have a mixed background of C57BL/6J and 129/SvImJ. For the prostate regeneration experiment, mice were surgically castrated at 8 wk of age. Ten days after castration, mice received daily ip injection of testosterone propionate (TP) (5 mg/kg) for 10 d to allow the prostate to regenerate (26). Mice were ip injected with bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) (10 mg/kg) 6 h before being killed. When necessary, WT mice received TO1317 treatment (daily gavage at 50 mg/kg) beginning 2 d before the TP treatment and continued until the completion of the experiment. The urogenital complex was removed, and the anterior (AP), ventral, lateral (LP), and dorsal prostate (DP) lobes were separated under a dissecting microscope and weighed. Ventral prostate lobes were processed for paraffin sections and subjected to immunostaining for BrdU or proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA). Prostate lobes from each mouse were pooled for RNA extraction and gene expression analysis. Animals were killed in a CO2 chamber. The use of mice in this study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

SULT assay

SULT assay using [35S]PAPS (PerkinElmer, Inc., Wellesley, MA) as the SULF donor was performed as previously described (27,28,29). In brief, 20 μg/ml total liver cytosolic extract was incubated with 5 μm T substrate at 37 C. Reaction was terminated by the addition of ethyl acetate. Unconjugated substrate and free [35S]PAPS were extracted by vigorous mixing followed by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 5 min. The amount of radioactivity in the aqueous phase was determined by liquid scintillation. Each reaction was run in triplicate.

Cell proliferation assay

LNCaP and DU145 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Cells were seeded onto 12-well cell culture plates at the density of 3 × 104 per well. After 24-h incubation, cells were replaced with RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% charcoal/dextran-stripped FBS, in the absence or presence of androgens (T or DHT, 10 nm each) and/or LXR ligands [22(R)-hydroxycholesterol, GW3965, or TO1317, 10 μm each]. Cells were replaced with fresh medium daily. After 4-d treatment, cells were trypsinized and counted with a hematocytometer. When necessary, cells were cotreated with 10 μm dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA).

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine 5-triphosphate-biotin end labeling of fragmented DNA (TUNEL) assay

LNCaP cells were seeded onto chamber slides (catalog no. 154526) from Nalge Nunc International (Naperville, IL) at the density of 2.5 × 104 per well and incubated overnight before treatment with various LXR agonists (10 μm each) for 3 d. Cells were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (pH 7.4) for 30 min. TUNEL assays were performed using an assay kit (catalog no. 11 684 795 910) from Roche Diagnostics (Indianapolis, IN). Apoptotic cells were detected by fluorescein staining, and the nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

Measurement of serum levels of T and LH

The WT and TG mice were castrated at 8 wk. Ten days after castration, mice received a single ip injection of TP (5 mg/kg) 24 h before being killed, and serum T levels were measured. When necessary, WT mice received GW3965 treatment (daily gavage at 20 mg/kg) beginning 2 d before the TP treatment and continued until the completion of the experiment. Serum T levels were determined using a T enzymatic immunoassay (EIA) kit from Cayman Chemical Co. (Ann Arbor, MI). According the manufacturer’s specification, this EIA assay is highly specific for T (100%), whereas its specificity for estered T and T SULF is 0.11 and 0.03%, respectively. The specificity of this EIA assay to T and its lack of specificity to TP, T SULF, and T glucuronide (Gluc) were experimentally confirmed by us (data not shown). The mouse blood samples were not extracted before assay. Noninterference was excluded by serial dilution (data not shown). The LH levels were commercially measured by the University of Virginia Center for Research and Reproduction (www.healthsystem.virginia.edu/internet/crr/ligand.cfm).

Plasmid construct and transfection assay

Expression vector for AR (pcDNA-AR) and the prostate-specific antigen (PSA)-Luc and ARE-Luc reporter genes were generous gifts from Dr. Hongwu Chen (Department of Biological Chemistry, University of California at Davis Cancer Center/Basic Science, University of California at Davis, Sacramento, CA) (30). The human SULT2A1 cDNA was cloned by RT-PCR using the following pair of oligonucleotides: 5′-CCGGAATTCATGTCGGACGATTTCTTATGG-3′, and 5′-CTAGCTAGCTTATTCCCATGGGAACAGCTC-3′. The SULT2A1 cDNA was digested and inserted into the pCMX expression vector. The identity of the cDNA was verified by DNA sequencing. HepG2 and DU145 cells were transfected on 48-well cell culture plates using the polyethyleneimine polymer transfection agent and Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA), respectively. For each triplicate transfection of HepG2 cells, 0.8 μg reporter, 0.4 μg pcDNA-AR, and 0.25 μg pCMX-β-gal were used. For DU145 cell transfection, the amounts of reporter, AR, and β-gal were 0.15, 0.1, and 0.25 μg, respectively. Transfected cells were then treated with vehicle or androgens in medium containing 10% charcoal/dextran-stripped FBS for 24 h before harvesting for luciferase and β-gal assays. The transfection efficiency was normalized against the β-gal activity.

Northern blot and real-time RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated from tissues or cell cultures using the Trizol reagent from Invitrogen. Northern hybridization using 32P-labeled cDNA probe was performed as described (23). In the real-time RT-PCR analysis, RT was performed with the random hexamer primers and the Superscript RT III enzyme from Invitrogen following the manufacturer’s instruction. SYBR Green-based real-time PCR was performed with the ABI 7300 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Data were normalized against the control of cyclophilin signals. Sequences of the real-time PCR probes are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sequences of real-time PCR primers

| Gene | Primer sequences

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Forward | Reverse | |

| Ar | CAGTGGATGGGCTGAAAAAT | CTTGAGCAGGATGTGGGATT |

| 3β-Hsd | GCTTCCTGCTACGTCCAGTC | CCAGATCTCGCTGAGCTTTC |

| 17β-Hsd | GTTATGAGCAAGCCCTGAGC | AAGCGGTTCGTGGAGAAGTA |

| 5α-Reductase | ACCTTTGTCTTGGCCTTCCT | GGGTTACCCAGTCTTCAGCA |

| Sult2a9 | CTGGCTGTCCATGAGAGAAT | GGCTTGGAAAGAGCTGTACT |

| Lxrα | AGGAGTGTCGACTTCGCAAA | CTCTTCTTGCCGCTTCAGTTT |

| Lxrβ | AAGCAGGTGCCAGGGTTCT | TGCATTCTGTCTCGTGGTTGT |

| Lhβ | ATCACCTTCACCACCAGCAT | GTAGGTGCACACTGGCTGAG |

| Sts | AGCACGAGTTCCTGTTCCAC | GTTGGGCGTGAAGTAGAAGG |

| Sult2b1 | TGCTGGGCAATTAAAGGACC | AGCCCTTGATGTGGTCAAAC |

| Sult2b1b | CTGTGGAGCTCGTCTGAGAA | GTGAGTACATGCCGACAGGA |

| VP-LXRα | GGCCGACTTCGAGTTTGAGC | GCAGAATCAGGAGAAACATC |

| Cyclophilin | TGGAGAGCACCAAGACAGACA | TGCCGGAGTCGACAATGAT |

| AR | GAATTCCTGTGCATGAAAGCA | CGAAGTTGATGAAAGAATTTTTGATT |

| LXRα | CCCTTCAGAACCCACAGAGAT | GCTCCTTCCCCAGCATTTT |

| LXRβ | CGCTAAGCAAGTGCCTGGTT | GCCTGGCTGTCTCTAGCAGC |

| SULT2A1 | GGTGTATCTGGGGACTGGAA | GGAACAGCTCTCGAGGAAGA |

| SULT2B1 | GGAGCTGCAGCAGGACTTAC | GCGTGTAGTTGGACATGGTG |

| PSA | CATCAGGAACAAAAGCGTGA | ATATCGTAGAGCGGGTGTGG |

| Cyclophilin | TTTCATCTGCACTGCCAAGA | TTGCCAAACACCACATGCT |

LXR RNA interference experiment

The small interfering RNA (siRNA) transfection was performed using Lipofectamine 2000. The human LXRs and SULT2A1 siRNAs were added to the final concentration of 5 nm in transfection. The sequences of siRNAs are: LXRα 5′-AGCAGGGCUGCAAGUGGAA-3′ (corresponding to nucleotides 1017–1039), LXRβ 5′-CAGAUCCGGAAGAAGAAGA-3′ (corresponding to nucleotides 746–768), and SULT2A1 5′-CCCGAAGAACUGAACUUAA-3′ (corresponding to nucleotides 699–721). All siRNAs, including the control scrambled siRNA, were ordered from QIAGEN Inc. (Valencia, CA). Cell were transfected for 5 h before being replaced with medium containing 10% FBS.

BrdU and PCNA immunostaining

Tissues were fixed in 4% formaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5 μm, and subjected to immunostaining with a rat monoclonal anti-BrdU antibody (catalog no. OBT0030) from Accurate (Westbury, NY) (1:20) or an anti-PCNA antibody (catalog no. VP-P980) from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA) (1:100) using the Vectastain Elite ABC Kit from Vector Laboratories. Diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride was used as the chromogen, and sections were counterstained with Gill’s hematoxylin.

Results

Activation of LXR in mice inhibited androgen-dependent prostate regeneration

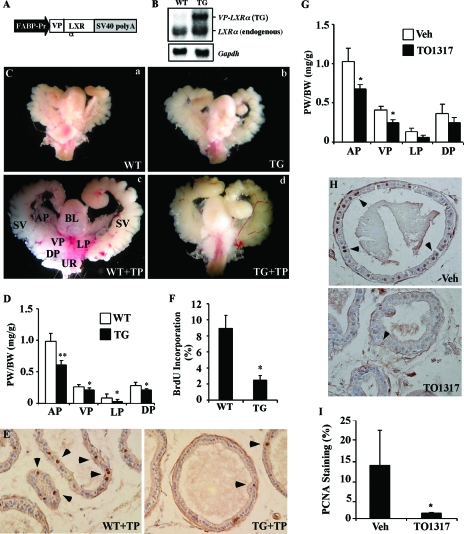

We have recently created the FABP-VP-LXRα TG mice that express the activated LXRα (VP-LXRα) in the liver under the control of the rat liver FABP promoter (25). Figure 1A shows the schematic representation of the transgene. The expression of the transgene in the liver was confirmed by Northern blot analysis (Fig. 1B). Created by fusing the VP16 activation domain of the herpes simplex virus to the amino-terminal of mouse LXRα, VP-LXRα activates LXR responsive genes in a constitutive manner (25). The creation of this TG line also led to our recent identification of Sult2a1/2a9 as a novel LXR target gene.

Figure 1.

Activation of LXR in mice inhibited androgen-dependent prostate regeneration. A, Schematic representation of the FABP-VP-LXRα TG construct. B, Expression of the transgene in the liver of WT and TG male mice was measured by Northern blot analysis. Membrane was probed with a LXRα cDNA probe that detects both the TG and endogenous LXRα. Each lane represents RNA samples pooled from five mice of the same genotype. C, Urogenital complex of WT and TG mice. D–F, PW normalized to BW (D), prostate luminal epithelial cell proliferation was measured by BrdU immunostaining with the positive nuclei (arrowheads) (E), and quantification of BrdU labeling index (F) in the WT and TG mice. In A–F, all mice, except those in C-a and C-b, were castrated at 8 wk old, rested for 10 d, and then treated with TP (5 mg/kg) for 10 d. Mice were labeled with BrdU (10 mg/kg) 6 h before being killed. Mice in C-a and C-b were castrated but not TP treated. Each group has seven to eight mice. G–I, WT mice were castrated at 8 wk old, rested for 10 d, and then treated with TP for 10 d, in the presence of vehicle (Veh) or TO1317 (50 mg/kg, daily gavage). The TO1317 treatment started 2 d before the TP treatment and continued until the completion of the experiment. Shown are PW normalized to BW (G), prostate luminal epithelial cell proliferation was measured by PCNA immunostaining with the positive nuclei (arrowheads) (H), and quantification of PCNA-positive cells (I). In G–I, each group contains three mice. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01, compare the WT (A–F) or vehicle (G–I). BL, Bladder; FABP-Pr, FABP promoter; SV, seminal vesicle; SV40, SV40 poly(A) sequences; UR, urethra; VP, ventral prostate.

The potential effect of Sult2a1/2a9 on androgen metabolism prompted us to examine whether activation of LXR affects androgen homeostasis. We first evaluated the effect of LXR activation on androgen-dependent prostate regeneration. In this experiment, WT or VP-LXRα TG mice were castrated at 8 wk of age. Ten days after castration, when the prostates have been degenerated (Fig. 1C) (31,32), mice were treated with TP (5 mg/kg·d, ip) for 10 d to allow the prostate to regenerate. Six hours before being killed, mice were labeled with BrdU (10 mg/kg, ip). The urogenital complexes were removed, and the AP, ventral prostate, LP, and DP lobes of prostate were dissected under a dissecting microscope and weighed. As shown in Fig. 1C, the prostate lobes in TP-treated WT mice were notably larger that their TG counterparts. Indeed, the average weights of all prostate lobes, when measured as ratios of prostate weight (PW) to body weight (BW), were significantly lower in the TG mice than the WT mice (Fig. 1D). It appeared that LXR had most profound effect on the AP. The retarded prostate regeneration in the TG mice was accompanied by a decrease in prostate epithelial proliferation as measured by BrdU immunostaining (Fig. 1E). The BrdU labeling index in the ventral prostate of TG mice was 28% of the WT mice (Fig. 1F).

The inhibition of androgen-dependent prostate regeneration was also observed in WT mice treated with the LXR agonist TO1317. In this experiment, 8-wk-old WT male mice were castrated. Ten days after castration, mice were randomly divided into two groups, with one group receiving daily gavage of TO1317 (50 mg/kg) and the control group receiving vehicle until the completion of the experiments. Our pilot experiment showed that the 50 mg/kg dose of TO1317 is optimal to show the effect on prostate regeneration. Beginning at 12 d after castration, all mice received daily ip injection of TP (5 mg/kg) for 10 d before being killed and were analyzed for prostate regeneration. As shown in Fig. 1G, the regeneration of all lobes was inhibited in the TO1317-treated mice. Immunostaining of PCNA, another indicator of cell proliferation, showed that the percentage of PCNA-positive cells in the ventral prostate was higher in the vehicle-treated than the TO1317-treated mice (Fig. 1, H and I). Treatment of WT mice with GW3965, another synthetic LXR agonist, resulted in a similar inhibition of androgen-dependent prostate regeneration (data not shown).

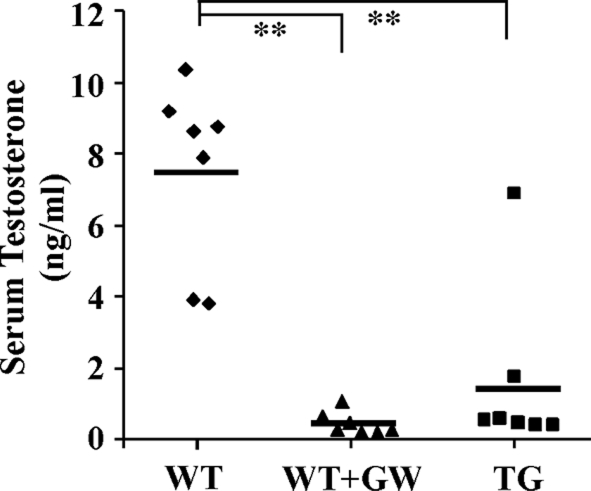

Activation of LXR lowered the circulating concentration of T

To understand the mechanism by which LXR inhibits prostate regeneration, we measured the levels of T in the serum of TG mice and GW3965-treated WT mice. In this experiment, mice were castrated at 8 wk. Ten days after castration, mice were treated with a single dose of TP (5 mg/kg, ip), and the mice were killed 24 h after the TP injection. When the LXR ligand was used, the GW3965 treatment started 2 d before the TP treatment and continued until the completion of the experiment. As shown in Fig. 2, the average serum T concentration in TP-treated castrated WT mice was 7.4 ng/ml, similar to what has been reported (33). In a sharp contrast, the genetic (TG) or pharmacological (GW3965) activation of LXR resulted in significantly decreased serum concentrations of T.

Figure 2.

Activation of LXR lowered the circulating level of active T. WT and VP-LXRα TG mice were castrated at 8 wk, rested for 10 d, and then treated with a single ip injection of TP (5 mg/kg) 24 h before being killed. When applicable, the GW3965 (GW) treatment (20 mg/kg, daily gavage) started 2 d before the TP treatment and continued until the completion of the experiment. Diamonds represent individual mice. Lines represent average T levels in each group. **, P < 0.01.

Treatment with LXR agonists inhibited androgen-dependent prostate cancer cell growth

The inhibition of androgen-dependent prostate regeneration led us to determine whether activation of LXR affects androgen-dependent human prostate cancer cell growth. In this experiment, the AR-positive and androgen-dependent LNCaP cells seed in charcoal/dextran-stripped FBS were treated with 22(R)-hydroxycholesterol, GW3965, or TO1317, in the absence or presence of the supplemented androgens, including T and DHT. As expected, treatment with T or DHT induced 2- to 3-fold increases in cell numbers (Fig. 3A, left panel). All three LXR agonists, when applied at 10 μm concentration, inhibited the androgen dependent-LNCaP cell proliferation with TO1317 had the most dramatic inhibition. In the absence of androgens, 22(R)-hydroxycholesterol and GW3965 had little effect on LNCaP cell growth, but TO1317 has a modest but significant inhibitory effect. Under the same cell culture condition, TO1317 had little effect on the growth of the AR-negative and androgen-independent DU145 cells, regardless of the androgen treatment (Fig. 3A, right panel).

Figure 3.

Treatment with LXR agonists inhibited androgen-dependent prostate cancer cell growth. A, Left panel, Treatment with LXR agonist 22(R)-hydroxycholesterol (22R), GW3965 (GW), and TO1317 (TO) inhibited T and DHT induced LNCaP cell proliferation as measured by cell number counting. Cells were maintained in medium supplemented with 10% charcoal/dextran-stripped FBS during the 4-d treatment period. A, Right panel, Neither androgens nor TO1317 had an effect on the growth of DU145 cells using the same culture conditions. B and C, LNCaP cells were maintained in medium containing 10% FBS for 3 d in the presence of vehicle (Veh), 22(R)-hydroxycholesterol, GW3965 or TO1317. B, Total RNA was isolated, and the mRNA expression of PSA was measured by real-time PCR. C, Apoptosis was measured and quantified by TUNEL assay. D, Down-regulation of LXRα and LXRβ by siRNAs abolished the growth inhibitory effect of GW3965 on LNCaP cells. The treatment conditions after siRNA transfection were identical to those described in B and C. The LXR ligand concentration is 10 μm. The concentration for T or DHT is 10 nm. E, The efficiencies of LXR knockdowns were confirmed by real-time PCR. Knockdown efficiency was presented as expression relative to that observed in the Lipofectamine alone control (arbitrarily set at one). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. Ctrl, Lipofectamine alone control; si, small interfering; UD,undetectable.

The TO1317- and GW3965-induced LNCaP growth inhibition was accompanied by a suppression of the mRNA expression of the PSA (Fig. 3B) and increased apoptosis as revealed by TUNEL assay (Fig. 3C). Consistent with the result of cell proliferation, TO1317 showed the most dramatic effect in inhibiting PSA expression and triggering apoptosis. The inhibitory effect of LXR agonists on LNCaP cells was LXR dependent because this inhibition was abolished when both LXRα and LXRβ were knocked down by siRNAs (Fig. 3D). The down-regulation of LXR expression in siRNA-transfected cells was confirmed by real-time PCR analysis (Fig. 3E).

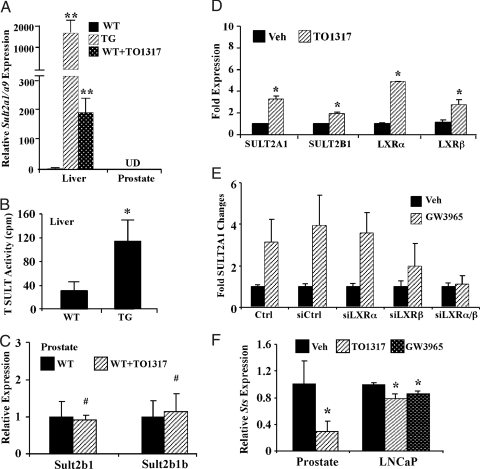

Activation of LXR induced the expression of SULT2A1 and suppressed the expression of STS in mouse liver and LNCaP cells

The TG and TO1317-treated WT male mice showed markedly increased expression of Sult2a1/2a9 in the liver (Fig. 4A), consistent with our previous report (25). The liver cytosol extracts of the TG mice also exhibited a significantly higher sulfation activity toward T, a known Sult2a1/2a9 substrate (7,12) (Fig. 4B). The basal expression of Sult2a1/2a9 in the prostate is nearly undetectable (Ct number was greater than 34, or the signals were undetermined in real-time PCR analysis), consistent with the notion that Sult2a1/2a9 is predominantly expressed in the liver in rodents (13). The expression of Sult2a1/2a9 in the prostate also failed to be induced in LXR ligand-treated mice (Fig. 4A). Sult2b1 and Sult2b1b are expressed in the prostate, but their expression was not altered in response to TO1317 (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Activation of LXR induced the expression of SULT2A1 and suppressed the expression of STS in the mouse liver and LNCaP cells. A, Activation of hepatic Sult2a9 gene expression in VP-LXRα TG mice and WT mice treated with TO1317 as shown by real-time PCR. Each group contains three to five mice. B, Increased T SULT activity in TG mice. Cytosolic liver extracts from WT and TG mice were incubated with T as the substrate and [35S]PAPS as the SULF donor. Radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation. C, Expression of Sult2b1 and Sult2b1b in the prostate of WT mice mock treated or treated with TO1317 as shown by real-time PCR. Mice were treated with TO1317 (50 mg/kg, gavage) for 10 d. Each group contains three mice. D, Effect of TO1317 on the mRNA expression of SULT2A1 and 2B1 in LNCaP cells. Cells were treated with vehicle (Veh) (dimethylsulfoxide) or 10 μm TO1317 for 2 d before RNA extraction and real-time PCR analysis. LXRα and LXRβ are included as positive controls of LXR target genes. E, Knocking down both LXRα and LXRβ abolished SULT2A1 activation in response to GW3965 in LNCaP cells as shown by real-time PCR analysis. F, Effect of LXR ligands on the mRNA expression of STS in the mouse prostate and LNCaP cells as shown by real-time PCR. The same mice in C were used. LNCaP cells were treated with vehicle (dimethylsulfoxide), TO1317, or GW3965 (10 μm each) for 3 d. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; #, P > 0.05 (not significant). Ctrl, Lipofectamine alone control; si, small interfering; UD, undetectable.

We have previously shown that the expression of SULT2A1 was induced in primary human hepatocytes treated with TO1317 (25). Here, we showed that the expression of SULT2A1 was also induced in LNCaP cells treated with TO1317 (Fig. 4D). The human SULT2B1 was also modestly but significantly induced by TO1317, consistent with a previous report on keratinocytes (34). Although recombinant SULT2B1 is capable of sulfonating T and DHT, this enzyme has been more effective in sulfonating adrenal androgens, such as androstenediol and DHEA (7,17). In TO1317-treated LNCaP cells, the expression of both LXR isoforms, known LXR target genes (20,35,36), was induced as expected (Fig. 4D). The activation of SULT2A1 by TO1317 in LNCaP cells was LXR dependent because knocking down both LXR isoforms abolished the SULT2A1 activation (Fig. 4E).

We also measured the effect of LXR activation on the expression of STS. As shown in Fig. 4F, treatment with LXR agonists inhibited the expression of STS in both the mouse prostate and LNCaP cells. Interestingly, the effect of LXR on Sts expression appeared to be prostate specific because the VP-LXRα transgene had little effect on the hepatic expression of Sts (data not shown).

Sulfonated T failed to activate AR and activation of SULT2A1 was sufficient to deactivate androgens and required for the growth inhibitory effect of LXR agonists

We used transient transfection and reporter gene assay to determine whether the sulfonated T is indeed hormonally inactive. In this experiment, HepG2 cells were transiently transfected with AR, together with the AR-responsive natural PSA promoter reporter gene (PSA-Luc) or a synthetic report gene (ARE-Luc) that contains five copies of the AR response element (ARE) derived the PSA gene promoter. Transfected cells were then treated with T, T Sulf, or T Gluc for 24 h before luciferase assay. As shown in Fig. 5A, treatment with T induced the reporter gene activities as expected. In a sharp contrast, the activation of both reporter genes was largely abolished in T Sulf-treated cells. T Gluc was also ineffective to activate AR (Fig. 5A). The lack of T Sulf and T Gluc effect may also be a result of these two compounds not being internalized by cells.

Figure 5.

Sulfonated T failed to activate AR and activation of SULT2A1 was sufficient to deactivate androgens and required for the growth inhibitory effect of LXR agonists. A, SULF conjugated T (T-Sult) failed to activate AR in transient transfection and reporter gene assay. HepG2 cells were transfected with expression vector for AR and AR responsive PSA-Luc or ARE-Luc reporter gene as indicated. Cells were then treated with vehicle (Veh), T, T Sulf, or T Gluc (10 nm each) for 24 h before luciferase assay. B and C, Ectopic expression of SULT2A1 in DU145 (B) or HepG2 (C) cells was sufficient to abolish the activity of the exogenously added T. Cells were transfected with AR, PSA-Luc, and increasing concentrations of SULT2A1. The SULT2A1 to AR plasmid DNA ratios are labeled. Cells were then treated with T (1 nm) for 24 h before luciferase assay. Insets in B and C show that the expression of the endogenous and/or transfected AR and SULT2A1 mRNA was confirmed by RT-PCR. Cyclophilin (Cyc) is included as a loading control. Lane 0 represents control CMX vector-transfected cells, and Lane 1 represents cells transfected with both AR and SULT2A1 at a 1:1 ratio. D, The growth inhibitory effect of TO1317 on T-induced LNCaP cell proliferation was inhibited in the presence of the SULT2A1 inhibitor DHEA (10 μm). Proliferation was measured by cell countering. E, Knocking down SULT2A1 by siRNA abolished the growth inhibitory effect of GW3965 in LNCaP cells. The treatment conditions after siRNA transfection were identical to those described in Fig. 3, B and C. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; #, P > 0.05 (not significant). Si Ctrl, Small interfering control.

To determine whether activation of SULT2A1 is sufficient to deactivate androgens, DU145 (Fig. 5B) and HepG2 (Fig. 5C) cells were transfected with AR and PSA-Luc, together with increasing concentrations of expression vector for SULT2A1, before being treated with T for 24 h. As shown in Fig. 5, B and C, cotransfection of SULT2A1 inhibited T-induced reporter gene activation in a dose-dependent manner in both cell lines.

To determine whether SULT2A1 activity is required for the growth inhibitory effect of LXR agonists, we repeated the experiment to examine the effect of TO1317 on LNCaP cell proliferation in the absence or presence of DHEA, a known SULT2A1-specific enzyme inhibitor (37,38). As shown in Fig. 5D, the inhibitory effect of TO1317 on T-stimulated cell proliferation was largely abolished, whereas DHEA treatment alone had little effect on the cell growth. Knocking down the endogenous SULT2A1 in LNCaP cells was also efficient to abolish the growth inhibitory effect of GW3965 (Fig. 5E). The efficiency of SULT2A1 knockdown was confirmed by real-time PCR (data not shown).

Effect of LXR activation on androgen synthesis, AR expression, and pituitary hormone

We have measured the expression of androgen synthesizing enzymes in the testis and prostate. We have previous shown that the VP- LXRα transgene is expressed in the testis (29), which was confirmed by real-time PCR (Fig. 6A). Among testicular androgen synthesizing enzymes, the expression of 3β- and 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases (Hsds) was modestly but significantly increased in the TG mice. In the prostate, TO1317 treatment had no significant effect on the expression of either AR or 5α-reductase (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

Effect of LXR activation on androgen synthesis, AR expression, and pituitary hormone. A, The VP-LXRα transgene is expressed in the testis and induced the testicular expression of 3β-Hsd and 17β-Hsd. Each group contains four to five mice. Inset shows the expressions of VP-LXRα in the liver and testis of TG mice as shown by RT-PCR. Cyclophilin (Cyc) is included as a loading control. B, Prostatic mRNA expression of AR and 5α-reductase in WT mice treated with vehicle (Veh) or TO1317. Each group contains three mice. C, Serum LH levels in castrated mice treated with TP for 24 h. The mice are from those described in Fig. 2. D, Pituitary expression of Lhβ, LXRα, and LXRβ in WT male mice treated with GW3965 (GW) for 7 d. Each group contains six mice. *, P < 0.05; #, P > 0.05 (not significant).

The synthesis of androgens is also under the influence of pituitary LH. We showed that, in castrated mice that have been treated with TP for 24 h, neither GW3965 nor the transgene had a significant effect on the serum level of LH (Fig. 6C). In intact WT male mice, treatment with GW3965 modestly but significantly induced the pituitary mRNA expression of Lhβ (Fig. 6D). Both LXRα and LXRβ are expressed in the pituitary, but their expression was not affected by GW3965.

Discussion

In this report we revealed a novel LXR-controlled and SULT2A1-mediated pathway of androgen deprivation. Genetic or pharmacological activation of LXR was sufficient to inhibit androgen-responsive prostate regeneration and prostate cancer cell proliferation. It remains to be determined whether the LXR agonist effect on androgens will be abolished in the LXR null mice.

Consistent with the notion that androgens play an important role in the initiation and progression of prostate cancer, androgen ablation has been an effective therapy for hormone-dependent prostate cancers. Strategies to lower T level in prostate cancer patients include orchiectomy and the use of LHRH agonists or antagonists. Orchiectomy is invasive and nonreversible. LHRH agonist therapy is widely used as a medical and reversible castration. Another strategy to inhibit androgenic effect is to use the antiandrogens. A clinical concern for the use of LHRH agonists and antiandrogens is the potential effect of these agents on the hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis after the cessation of the therapy. In several studies the serum T levels increased gradually upon long-term LHRH agonist therapy (39,40). It was also reported that antiandrogens may eventually cross the blood-brain barrier, which will promote the release of LH into the circulation, leading to a subsequent increase in serum T level (2). Therefore, it is necessary to continue to develop novel and effective androgen deprivation therapies for prostate cancer with fewer side effects. Here, we show that activation of LXR is sufficient to inhibit androgenic activity both in vivo and in cultured prostate cancer cells. The inhibition of prostate regeneration in LXR-activated mice was in agreement with the marked decrease in serum T levels in these animals. The activation of SULT2A1, a known LXR target gene, is required for the androgen deprivation effect of LXR agonists. We propose that the LXR-SULT2A1 pathway represents a novel mechanism of androgen deprivation.

The expression of SULT2A1 is known to subject to androgen regulation. It has been shown that activation of AR suppressed SULT2A1 expression, and the level of SULT2A1 expression is lower in androgen-dependent prostate cancer cells (14). These results suggest that decreased expression of SULT2A1 may contribute to unchecked androgen stimulation and cancerous transformation. It is also conceivable that reactivation of SULT2A1 may represent a novel therapeutic strategy to inhibit androgen-dependent prostate cancer growth. Indeed, we showed that treatment with LXR agonists inhibited androgen-dependent prostate cancer cell growth in a LXR- and SULT2A1-dependent manner. Interestingly, SULT2A1 regulation exhibits both tissue and species specificity. It appears that Sult2a1/2a9 activation by LXR in mice is liver specific. The mouse prostate has little basal or inducible expression of this Sult isoform, suggesting that the liver-mediated systemic androgen deprivation plays the major role in the prostate regeneration phenotype. In contrast, the human SULT2A1 regulation can be seen in both the liver and prostate cells. We have previously shown that treatment with LXR agonist induced the expression of SULT2A1 in primary cultures of human hepatocytes (25). In the current study, we showed that LNCaP cells exhibited both basal and inducible expression of SULT2A1 (Fig. 4D).

Interestingly, activation of LXR also decreased the expression of STS in the mouse prostate and LNCaP cells (Fig. 4F). The prostate is a major peripheral tissue in which STS plays an important role in producing biologically active androgens from sulfonated metabolites (18). Our results suggest that activation of Sult2a1 in the liver and suppression of Sts in the prostate may function in concert to ensure the LXR-mediated androgen deprivation.

The adrenal glands express both Sult2a (41) and LXR (42). It remains to be determined whether activation of LXR induces the adrenal expression of the Sult2a gene; and if so, increased adrenal Sult2a may keep DHEA in the sulfated form, and this, in turn, may help to lower the level of adrenal androgens in the prostate, especially because sulfatase expression in the prostate is suppressed in response to activated LXR. Decreased adrenal androgens may impact negatively on the prostate growth in castrated mice.

Glucuronidation is another important metabolic pathway to deactivate and eliminate androgens (43). We have previously reported that activation of LXR in mice had little effect on the expression and activity of some hepatic uridine 5′-diphosphate-glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs), such as Ugt1a1 (29). It is known that the hepatic UGT2Bs play a role in androgen glucuronidation (43,44). It remains to be determined whether the expression of hepatic Ugt2bs is altered in our LXR mouse models.

Other than SULT2A1, other SULT isoforms, including the estrogen SULT (EST or SULT1E1), are also capable of sulfonating steroid hormones. We have recently shown that activation of LXR induced the expression of EST and, thus, promoted estrogen deprivation. The expression of EST is required for the LXR effect on estrogens because the estrogen deprivation phenotype was completely abolished in the EST null mice (29). EST is also expressed in the prostate (data not shown) (45). We showed that GW3965 was efficient to inhibit prostate regeneration and lower the serum level of T in the EST null mice (data not shown), suggesting that EST is not required for the androgen deprivation effect of LXR. Our results suggested that LXR affects androgen and estrogen metabolism through regulating distinct target genes. Nevertheless, the combined effect of LXR on androgen and estrogen metabolism suggests that LXR may function as a master regulator of steroid hormone homeostasis, an endocrine role distinct to the previously known sterol sensor role of this receptor (46).

Activation of LXR has been implicated in apoptosis. Interestingly, LXR could have an opposite effect on apoptosis depending on the cellular context. It was reported that activation of LXR prevented bacterial-induced macrophage apoptosis by regulating pro-apoptotic and antiapoptotic regulators and effectors (47,48). In two other independent studies, LXR was found to induce β-cell apoptosis through LXR-mediated lipotoxicity (49,50). We have recently shown that TO1317 had little effect on apoptosis in the MCF-7 xenograft tumors (29). Using cells maintained in complete serum, Fukuchi and colleagues (51,52) reported that TO1317 inhibited the growth of both androgen-dependent and independent prostate cancer cells, and this inhibition was associated with increased expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27Kip−1. The growth inhibitory effect of LXR agonists on androgen-independent prostate cancer cells, such as DU145 cells, was not observed in our experiments. Instead, using culture conditions of charcoal/dextran-stripped serum and the addition of exogenous androgens, we showed clearly that the inhibitory effect of LXR agonists on LNCaP cells is androgen dependent (Fig. 3). We also showed that treatment with GW3965 and TO1317 suppressed the expression of CDK4 protein in LNCaP cells, but not in DU145 cells (data not shown), consistent with the selective growth inhibition.

In vivo control of circulating androgens is subjected to the effect of the hypothalamic-pituitary-reproductive axis. No significant changes in serum LH were detected despite significant reduction in circulating T levels in GW3965-treated WT and VP-LXRα TG mice. It is possible that the LH secretion is not rapidly suppressed after T treatment in castrated animals (53). In contrast, a significantly higher mRNA expression of Lhβ was found in the pituitary of GW3965 treated mice, consistent with a previous report that a combined loss of LXRs α and β in mice lowered plasma LH concentration and decreased the expression of androgen synthesizing enzymes (54). We can also not exclude the possibility that adrenal androgens may have contributed to the overall homeostasis of circulating androgens.

We recognize that there are several challenges in developing LXR as a therapeutic target for prostate cancer. It is known that intracellular conversion of T to DHT is important for prostatic cell proliferation. Several studies have demonstrated that a high expression of androgen-producing enzymes, such as the 17β-Hsd and 5α-reductase, is correlated with poor clinical outcome of prostate cancer (55). It has also been reported that castration decreases plasma concentration of T by more than 90%, however, androgen levels in prostate cancer tissues decreases by only 50–60% due to the conversion of adrenal androgens into DHT in prostate cancer cells (56). Our results showed that LXR activated 17β-Hsd but had little effect on 5α-reductase. The lipogenic effect of LXR is another potential concern. Androgens stimulate lipogenesis by activating lipogenic enzymes (57,58). Sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c and -2 genes, key lipogenic transcription factors, are up-regulated in LNCaP xenograft tumors (59), suggesting that aberrant regulation of lipid metabolism may play a role in prostate cancer. It remains to be seen whether LXR promotes lipogenesis in the prostate. It has also been reported that some LXR agonists could have partial or gene-specific activity to avoid the unwanted lipogenic side effect (60,61).

It has been reported that nonhepatic cells, including prostatic cells, can eliminate cholesterol by CYP27-mediated formation of 27-cholesterol and cholestenoic acid (62). 27-hydroxycholesterol is an endogenous LXR ligand (63), and the expression of CYP27 decreased during the progression of prostate cancer (52). These results suggest that a decreased production of endogenous LXR ligands and attenuation of LXR signaling may contribute to the progression of prostate cancer.

In summary, we have revealed a novel function of LXR in androgen deprivation, which may establish this nuclear receptor as a therapeutic target for hormone-dependent prostate cancer. Our results also suggest that SULT2A1 is likely the LXR target gene responsible for the androgen deprivation effect. We anticipate that the development of LXR agonists that have more specific SULT2A1 activation property may have future clinical potentials to treat hormone-dependent prostate cancer.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Hongwu Chen (University of California at Davis) for androgen receptor expression vector and reporter genes, and Drs. Jelavkar Uddhav and Malabika Sew (University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute) for sharing their expertise in prostate dissection.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health Grant ES014626. H.G. is supported by a Postdoctoral Fellowship (PDF0503458) from the Susan G. Komen for the Cure.

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online May 1, 2008

Abbreviations: AP, Anterior prostate; AR, androgen receptor; ARE, androgen responsive element; BrdU, bromodeoxyuridine; BW, body weight; DHEA, dehydroepiandrosterone; DHT, dihydrotestosterone; DP, dorsal prostate; EIA, enzymatic immunoassay; EST, estrogen sulfotransferase; FABP, fatty acid binding protein; FBS, fetal bovine serum; Gluc, glucuronide; Hsd, hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase; LP, lateral prostate; LXR, liver X receptor; PAPS, 3′-phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphosulfate; PCNA, proliferating cell nuclear antigen; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; PW, prostate weight; siRNA, small interfering RNA; STS, steroid sulfatase; SULF, sulfate; SULT, sulfotransferase; T, testosterone; TG, transgenic; TP, testosterone propionate; TUNEL, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine 5-triphosphate-biotin end labeling of fragmented DNA; UGT, uridine 5′-diphosphate-glucuronosyltransferase; VP, viral protein 16; WT, wild type.

References

- Chatterjee B 2003 The role of the androgen receptor in the development of prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer. Mol Cell Biochem 253:89–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denmeade SR, Isaacs JT 2002 A history of prostate cancer treatment. Nat Rev Cancer 2:389–396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long RM, Morrissey C, Fitzpatrick JM, Watson RW 2005 Prostate epithelial cell differentiation and its relevance to the understanding of prostate cancer therapies. Clin Sci (Lond) 108:1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society 2006 Cancer facts and figures. New York: American Cancer Society [Google Scholar]

- Trapman J, Brinkmann AO 1996 The androgen receptor in prostate cancer. Pathol Res Pract 192:752–760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinlein CA, Chang C 2004 Androgen receptor in prostate cancer. Endocr Rev 25:276–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strott CA 2002 Sulfonation and molecular action. Endocr Rev 23:703–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata K, Yamazoe Y 2000 Pharmacogenetics of sulfotransferase. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 40:159–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strott CA 1996 Steroid sulfotransferases. Endocr Rev 17:670–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glatt H, Boeing H, Engelke CE, Ma L, Kuhlow A, Pabel U, Pomplun D, Teubner W, Meinl W 2001 Human cytosolic sulphotransferases: genetics, characteristics, toxicological aspects. Mutat Res 482:27–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raftogianis RB, Zalatoris JJ, Walther SF 1998 The role of pharmacogenetics in cancer therapy, prevention, and risk. Fox Chase Cancer Center Scientific Report 243–247 [Google Scholar]

- Meloche CA, Sharma V, Swedmark S, Andersson P, Falany CN 2002 Sulfation of budesonide by human cytosolic sulfotransferase, dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfotransferase (DHEA-ST). Drug Metab Dispos 30:582–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song CS, Jung MH, Kim SC, Hassan T, Roy AK, Chatterjee B 1998 Tissue-specific and androgen-repressible regulation of the rat dehydroepiandrosterone sulfotransferase gene promoter. J Biol Chem 273:21856–21866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J, Song CS, Matusik RJ, Chatterjee B, Roy AK 1998 Inhibition of androgen action by dehydroepiandrosterone sulfotransferase transfected in PC-3 prostate cancer cells. Chem Biol Interact 109:267–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee B, Song CS, Jung MH, Chen S, Walter CA, Herbert DC, Weaker FJ, Mancini MA, Roy AK 1996 Targeted overexpression of androgen receptor with a liver-specific promoter in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:728–733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanbrough M, Bubley GJ, Ross K, Golub TR, Rubin MA, Penning TM, Febbo PG, Balk SP 2006 Increased expression of genes converting adrenal androgens to testosterone in androgen-independent prostate cancer. Cancer Res 66:2815–2825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geese WJ, Raftogianis RB 2001 Biochemical characterization and tissue distribution of human SULT2B1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 288:280–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed MJ, Perohit A, Woo LWL, Newman SP, Potter BVL 2005 Steroid sulfatase: molecular biology, regulation, and inhibition. Endocr Rev 26:171–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repa JJ, Mangelsdorf DJ 2002 The liver X receptor gene team: potential new players in atherosclerosis. Nat Med 8:1243–1248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz JR, Tu H, Luk A, Repa JJ, Medina JC, Li L, Schwendner S, Wang S, Thoolen M, Mangelsdorf DJ, Lustig KD, Shan B 2000 Role of LXRs in control of lipogenesis. Genes Dev 14:2831–2838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins JL, Fivush AM, Watson MA, Galardi CM, Lewis MC, Moore LB, Parks DJ, Wilson JG, Tippin TK, Binz JG, Plunket KD, Morgan DG, Beaudet EJ, Whitney KD, Kliewer SA, Willson TM 2002 Identification of a nonsteroidal liver X receptor agonist through parallel array synthesis of tertiary amines. J Med Chem 45:1963–1966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelcer N, Tontonoz P 2006 Liver X receptors as integrators of metabolic and inflammatory signaling. J Clin Invest 116:607–614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barish GD, Evans RM 2004 PPARs and LXRs: atherosclerosis goes nuclear. Trends Endocrinol Metab 15:158–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass CK, Ogawa S 2006 Combinatorial roles of nuclear receptors in inflammation and immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 6:44–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uppal H, Saini SP, Moschetta A, Mu Y, Zhou J, Gong H, Zhai Y, Ren S, Michalopoulos GK, Mangelsdorf DJ, Xie W 2007 Activation of LXRs prevents bile acid toxicity and cholestasis in female mice. Hepatology 45:422–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukai M, Dong Q, Hardy MP, Kiyokawa H, Peterson RE, Cooke PS 2005 Altered prostatic epithelial proliferation and apoptosis, prostatic development, and serum testosterone in mice lacking cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors. Biol Reprod 73:951–958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uppal H, Toma D, Saini SP, Ren S, Jones TJ, Xie W 2005 Combined loss of orphan receptors PXR and CAR heightens sensitivity to toxic bile acids in mice. Hepatology 41:168–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saini SP, Sonoda J, Xu L, Toma D, Uppal H, Mu Y, Ren S, Moore DD, Evans RM, Xie W 2004 A novel constitutive androstane receptor-mediated and CYP3A-independent pathway of bile acid detoxification. Mol Pharmacol 65:292–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong H, Guo P, Zhai Y, Zhou J, Uppal H, Jarzynka MJ, Song WC, Cheng SY, Xie W 2007 Estrogen deprivation and inhibition of breast cancer growth in vivo through activation of the orphan nuclear receptor liver X receptor. Mol Endocrinol 21:1781–1790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louie MC, Yang HQ, Ma AH, Xu W, Zou JX, Kung HJ, Chen HW 2003 Androgen-induced recruitment of RNA polymerase II to a nuclear receptor-p160 coactivator complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:2226–2230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English HF, Santen RJ, Isaacs JT 1987 Response of glandular versus basal rat ventral prostatic epithelial cells to androgen withdrawal and replacement. Prostate 11:229–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karhadkar SS, Bova GS, Abdallah N, Dhara S, Gardner D, Maitra A, Isaacs JT, Berman DM, Beachy PA 2004 Hedgehog signalling in prostate regeneration, neoplasia and metastasis. Nature 431:707–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellwood-Yen K, Wongvipat J, Sawyers C 2006 Transgenic mouse model for rapid pharmacodynamic evaluation of antiandrogens. Cancer Res 66:10513–10516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang YJ, Kim P, Elias PM, Feingold KR 2005 LXR and PPAR activators stimulate cholesterol sulfotransferase type 2 isoform 1b in human keratinocytes. J Lipid Res 46:2657–2666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repa JJ, Liang G, Ou J, Bashmakov Y, Lobaccaro JM, Shimomura I, Shan B, Brown MS, Goldstein JL, Mangelsdorf DJ 2000 Regulation of mouse sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c gene (SREBP-1c) by oxysterol receptors, LXRα and LXRβ. Genes Dev 14:2819–2830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laffitte BA, Joseph SB, Walczak R, Pei L, Wilpitz DC, Collins JL, Tontonoz P 2001 Autoregulation of the human liver X receptor α promoter. Mol Cell Biol 21:7558–7568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehse PH, Zhou M, Lin SX 2002 Crystal structure of human dehydroepiandrosterone sulphotransferase in complex with substrate. Biochem J 364(Pt 1):165–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KA, Fuda H, Lee YC, Negishi M, Strott CA, Pedersen LC 2003 Crystal structure of human cholesterol sulfotransferase (SULT2B1b) in the presence of pregnenolone and 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphate. Rationale for specificity differences between prototypical SULT2A1 and the SULT2B1 isoforms. J Biol Chem 278:44593–44599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morote J, Esquena S, Abascal JM, Trilla E, Cecchini L, Raventos CX, Catalan R, Reventos J 2006 Failure to maintain a suppressed level of serum testosterone during long-acting depot luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonist therapy in patients with advanced prostate cancer. Urol Int 77:135–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinouchi T, Maeda O, Ono Y, Meguro N, Kuroda M, Usami M 2002 Failure to maintain the suppressed level of serum testosterone during luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonist therapy in a patient with prostate cancer. Int J Urol 9:359–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saner KJ, Suzuki T, Sasano H, Pizzey J, Ho C, Strauss 3rd JF, Carr BR, Rainey WE 2005 Steroid sulfotransferase 2A1 gene transcription is regulated by steroidogenic factor 1 and GATA-6 in the human adrenal. Mol Endocrinol 19:184–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins CL, Volle DH, Zhang Y, McDonald JG, Sion B, Lefrancois-Martinez AM, Caira F, Veyssiere G, Mangelsdorf DJ, Lobaccaro JM 2006 Liver X receptors regulate adrenal cholesterol balance. J Clin Invest 116:1902–1912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turgeon D, Carrier JS, Levesque E, Hum DW, Belanger A 2001 Relative enzymatic activity, protein stability, and tissue distribution of human steroid-metabolizing UGT2B subfamily members. Endocrinology 142:778–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley DB, Klaassen CD 2007 Tissue- and gender-specific mRNA expression of UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs) in mice. Drug Metab Dispos 35:121–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takase Y, Luu-The V, Poisson-Pare D, Labrie F, Pelletier G 2007 Expression of sulfotransferase 1E1 in human prostate as studied by in situ hybridization and immunocytochemistry. Prostate 67:405–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tontonoz P, Mangelsdorf DJ 2003 Liver X receptor signaling pathways in cardiovascular disease. Mol Endocrinol 17:985–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph SB, Bradley MN, Castrillo A, Bruhn KW, Mak PA, Pei L, Hogenesch J, O'Connell R M, Cheng G, Saez E, Miller JF, Tontonoz P 2004 LXR-dependent gene expression is important for macrophage survival and the innate immune response. Cell 119:299–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valledor AF, Hsu LC, Ogawa S, Sawka-Verhelle D, Karin M, Glass CK 2004 Activation of liver X receptors and retinoid X receptors prevents bacterial-induced macrophage apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:17813–17818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe SS, Choi AH, Lee JW, Kim KH, Chung JJ, Park J, Lee KM, Park KG, Lee IK, Kim JB 2007 Chronic activation of liver X receptor induces β-cell apoptosis through hyperactivation of lipogenesis: liver X receptor-mediated lipotoxicity in pancreatic β-cells. Diabetes 56:1534–1543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wente W, Brenner MB, Zitzer H, Gromada J, Efanov AM 2007 Activation of liver X receptors and retinoid X receptors induces growth arrest and apoptosis in insulin-secreting cells. Endocrinology 148:1843–1849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuchi J, Kokontis JM, Hiipakka RA, Chuu CP, Liao S 2004 Antiproliferative effect of liver X receptor agonists on LNCaP human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res 64:7686–7689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuu CP, Hiipakka RA, Kokontis JM, Fukuchi J, Chen RY, Liao S 2006 Inhibition of tumor growth and progression of LNCaP prostate cancer cells in athymic mice by androgen and liver X receptor agonist. Cancer Res 66:6482–6486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindzey J, Wetsel WC, Couse JF, Stoker T, Cooper R, Korach KS 1998 Effects of castration and chronic steroid treatments on hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone content and pituitary gonadotropins in male wild-type and estrogen receptor-α knockout mice. Endocrinology 139:4092–4101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volle DH, Mouzat K, Duggavathi R, Siddeek B, Dechelotte P, Sion B, Veyssiere G, Benahmed M, Lobaccaro JM 2007 Multiple roles of the nuclear receptors for oxysterols liver X receptor to maintain male fertility. Mol Endocrinol 21:1014–1027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y, Suzuki T, Nakabayashi M, Endoh M, Sakamoto K, Mikami Y, Moriya T, Ito A, Takahashi S, Yamada S, Arai Y, Sasano H 2005 In situ androgen producing enzymes in human prostate cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer 12:101–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizokami A, Koh E, Fujita H, Maeda Y, Egawa M, Koshida K, Honma S, Keller ET, Namiki M 2004 The adrenal androgen androstenediol is present in prostate cancer tissue after androgen deprivation therapy and activates mutated androgen receptor. Cancer Res 64:765–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman MR, Solomon KR 2004 Cholesterol and prostate cancer. J Cell Biochem 91:54–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinnen JV, Brusselmans K, Verhoeven G 2006 Increased lipogenesis in cancer cells: new players, novel targets. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 9:358–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hager MH, Solomon KR, Freeman MR 2006 The role of cholesterol in prostate cancer. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 9:379–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song C, Liao S 2001 Hypolipidemic effects of selective liver X receptor α agonists. Steroids 66:673–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko E, Matsuda M, Yamada Y, Tachibana Y, Shimomura I, Makishima M 2003 Induction of intestinal ATP-binding cassette transporters by a phytosterol-derived liver X receptor agonist. J Biol Chem 278:36091–36098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repa JJ, Mangelsdorf DJ 1999 Nuclear receptor regulation of cholesterol and bile acid metabolism. Curr Opin Biotechnol 10:557–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu X, Menke JG, Chen Y, Zhou G, MacNaul KL, Wright SD, Sparrow CP, Lund EG 2001 27-hydroxycholesterol is an endogenous ligand for liver X receptor in cholesterol-loaded cells. J Biol Chem 276:38378–38387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]