Abstract

Chronic allograft nephropathy accounts for the loss of approximately 40% of allografts at 10 yr. Currently, no biomarker is available to detect interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy in the renal graft at an early stage, when intervention may be beneficial. Because tubular epithelial cells have been shown to exhibit phenotypic changes suggestive of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, we studied whether these changes predict the progression of fibrosis in the allograft. Eighty-three kidney transplant recipients who had undergone a protocol graft biopsy at both 3 and 12 mo after transplantation were enrolled. De novo vimentin expression and translocation of β-catenin into the cytoplasm of tubular cells were detected on the first biopsy by immunohistochemistry. Patients with expression of these markers in ≥10% of tubules at 3 mo had a higher interstitial fibrosis score at 1 yr and a greater progression of this score between 3 and 12 mo. The intensity of these phenotypic changes positively and significantly correlated with the progression of fibrosis, and multivariate analysis showed that their presence was an independent risk factor for this progression. In addition, the presence of early phenotypic changes was associated with poorer graft function 18 mo after transplantation. In conclusion, early phenotypic changes indicative of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition predict the progression toward interstitial fibrosis in human renal allografts.

Progressive renal fibrosis leading to the loss of renal function remains a major challenge in nephrology.1,2 To date, no effective treatment to revert established fibrosis is available, and its diagnosis is often late in the course of the causal disease because of a lack of early markers. Similarly, chronic allograft nephropathy has become the main cause for the loss of renal function in kidney transplant recipients. In France, approximately 40% of graft are lost at 10 yr.3 The observed lesions of chronic allograft nephropathy, namely interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy (IF/TA), are actually the end result of immune or nonimmune injury to the graft.4–7 One large prospective study demonstrated that IF/TA appear early in the course of transplantation and progress rapidly during the first year.8

Because myofibroblasts are the main source of renal interstitial extracellular matrix (ECM), many studies have strived to identify molecular markers of these activated fibroblasts in the kidney and their origin.9,10 Interestingly, under pathologic conditions, some mesenchymal markers may be abnormally expressed by tubular epithelial cells, along with a decreased expression of epithelial markers. Such epithelial phenotypic changes (EPC) have been previously described in a complex phenomenon called epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT).11–14 EMT plays a key role in embryogenesis and tissue repair and in cancer growth, invasion, and metastasis.15,16 Although it has been demonstrated that EMT could also contribute to renal, lung, and liver fibrogenesis in animal models,2,12,17–19 it is debatable whether the complete process (i.e., resulting in migration of epithelial cells into the renal interstitium) actually occurs in human diseases. Admittedly, however, EPC have been detected in tubular cells in several human native kidney diseases,20,21 in late human sclerotic grafts,22,23 and during acute cellular rejection.24,25 In a recent study,26 we demonstrated that some EPC were present in one third of protocol biopsies from graft kidneys with stable renal function 3 mo after transplantation. Specifically, we used two markers: The localization of β-catenin in tubular cells and their de novo expression of vimentin. β-Catenin is a membrane component of adherens junctions that normally co-localizes with E-cadherin and mediates its contact with actin cytoskeleton,27 but if β-catenin is diverted from the plasma membrane as a result of the loss of expression of E-cadherin, then it can feed into the Wnt signaling pathway and act as a transcriptional co-activator by binding to members of the T cell factor/lymphoid enhancer family of transcription factors.28,29 In tubular epithelial cells, β-catenin is a key component of the contact-dependent regulation of EMT.30 Vimentin is an intermediate filament typically expressed by mesenchymal cells. Its abnormal expression by epithelial cells is considered as a relevant marker of EMT31; we and other groups previously reported that in renal grafts, vimentin expression could be detected in a significant proportion of tubules.22,26,32 In this study, we demonstrated a strong association between these early EPC (i.e., the cytoplasmic translocation of β-catenin and the expression of vimentin, detected at 3 mo after renal transplantation) and the late IF/TA lesions observed 1 yr after transplantation. In addition, these changes are predictive of the progression of IF/TA lesions between 3 and 12 mo after transplantation.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

From June 2004 to June 2005, in the two centers participating in the study, 94 kidney transplant recipients successfully (i.e., resulting in an adequate biopsy specimen) underwent a protocol renal graft biopsy at both 3 and 12 mo. Among them, 11 were excluded because they already had mild to severe IF/TA at 3 mo (3-Mo IF/TA ≥2). Thus, 83 patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria (mean age 44.2 ± 11 yr; 53 men and 30 women), 63 (75.9%) of whom were engrafted with a kidney from a deceased donor (Table 1). All patients had received a biologic induction agent, either polyclonal antibodies (rabbit ATG, Thymoglobulin; Genzyme, Lyon, France; n = 20) or a monoclonal anti-CD25 antibody (basiliximab, Simulect; Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Rueil Malmaison, France; n = 63). The routine immunosuppressive regimen mostly consisted of a triple therapy including steroids, with a calcineurin inhibitor (cyclosporine A [Neoral; Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland; n = 52] or tacrolimus [Prograf; Astellas, Tokyo, Japan; n = 23]) and an inhibitor of nucleotide synthesis (mycophenolate mofetil, Cellcept; Roche Pharmaceuticals, Basel, Switzerland). Eight patients were on a calcineurin inhibitor–free regimen and treated with a mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor (sirolimus, Rapamune; Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Madison, WI). Thirty-three patients were on angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers. By 1 yr, the mean creatinine clearance value was 59.8 ± 2.2 ml/min. Nineteen (23%) patients had biopsy-proven acute rejection, 14 of which were clinically silent and detected by the 3-mo (n = 11) or 12-mo (n = 3) protocol biopsy (in six cases, it was retrospectively attributed to an insufficient or recently alleviated immunosuppression).

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (yr, mean ± SD) | 44.2 ± 11.6 |

| Gender (%) | |

| male | 64.0 |

| female | 36.0 |

| Cause of ESRD (%) | |

| glomerulopathy | 43.3 |

| polycystic kidney disease | 13.3 |

| interstitial nephritis | 12.0 |

| diabetes | 6.0 |

| hypertension | 2.4 |

| other | 22.9 |

| Deceased donor (%) | 75.9 |

| Mean duration of cold ischemia time (min, mean ± SD) | 1075 ± 672 |

| Most recent panel reactive antibody titer ≥20% (%) | 11.0 |

| ≥1 previous transplant (%) | 23.0 |

| >3 HLA mismatches (%) | 31.0 |

Detection of EPC in 3-Mo Biopsies

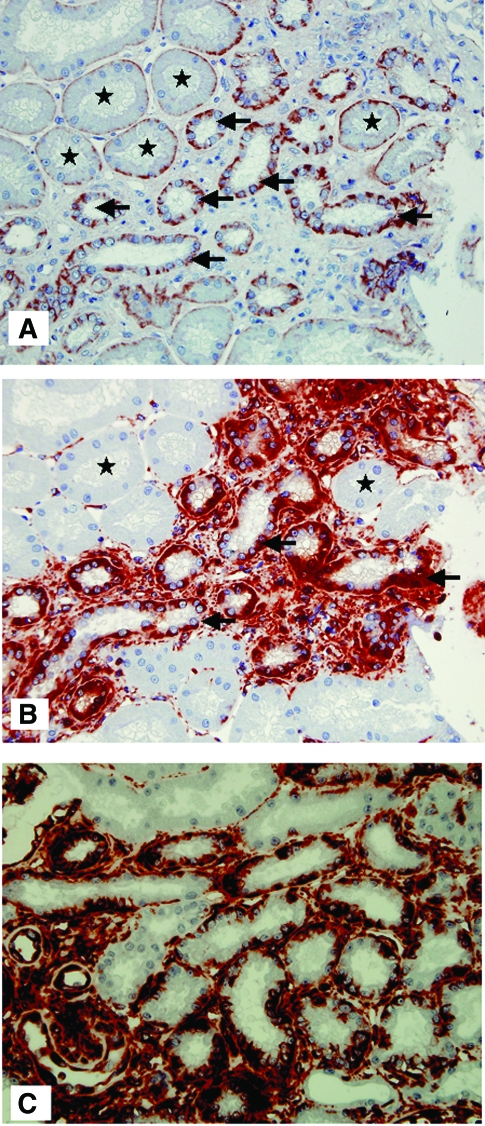

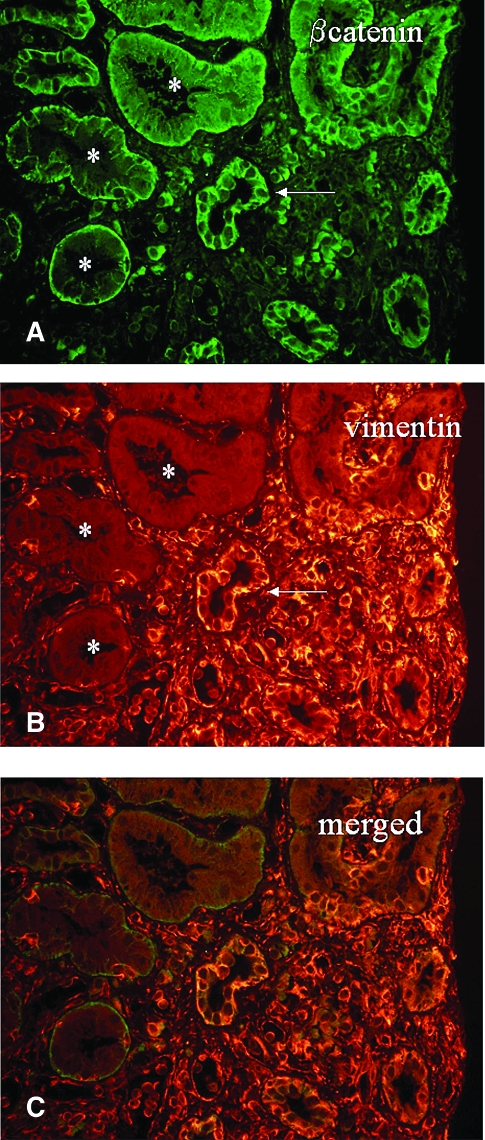

In normal tubules, as observed previously in implantation biopsies,26 β-catenin expression was found at the basal pole of proximal tubules and at the basolateral surface of distal tubules and collecting ducts; and no vimentin expression could be detected. Compared with that, we found an increased expression and a translocation of β-catenin from the basal or basolateral pole of some epithelial cells to the cytoplasm in the 3-mo graft kidneys. Serial sections demonstrated that a de novo vimentin expression was also observed in these cells (Figure 1, A and B). Importantly, EPC were not confined to fibrotic areas but also were present in nonatrophic tubules surrounded by a normal amount of matrix (Figure 1C). Serial sections also revealed frequent good co-localization of these two markers in the same tubules. As a proof of concept, double staining of β-catenin and vimentin is shown in Figure 2. In addition, the correlation analysis showed a highly significant association between the proportion of tubules expressing vimentin and the proportion in which β-catenin was translocated to the cytoplasm (r = 0.9, P < 0.0001, data not shown).

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical staining of β-catenin and vimentin in 3-mo biopsy. (A) A regular expression of β-catenin was found at the basal surface of normal proximal tubular epithelial cells (★, tubules in which β-catenin staining is interpreted as normal, i.e., not suggestive of EPC). An upregulation and intracellular translocation of β-catenin was observed in the epithelial cells of some proximal and distal tubules, especially in flat epithelial cells: The expression near the basal membrane was reduced or absent, whereas an intense, granular and irregular staining was found in the cytoplasm (arrows indicate tubules in which this translocation is suggestive of EPC). (B) Vimentin staining was negative in the epithelial cells of normal tubules (★) but was observed in flat epithelial cells or atrophic tubules (arrow) surrounded by interstitial fibrosis. The serial sections revealed that in the epithelial cells expressing vimentin, an upregulation and intracellular translocation of β-catenin expression was present. (C) Vimentin staining was also observed in nonatrophic tubules without excessive surrounding matrix.

Figure 2.

Double staining of β-catenin and vimentin in tubular epithelial cells. *Normal tubules with basal localization of β-catenin (A) and no expression of vimentin (B); the arrow indicates a tubule with phenotypic changes: Translocation of β-catenin and de novo expression of vimentin. (C) Merged image.

In the EPC-positive population, subclinical acute cellular rejection was more frequently observed (22 versus 9.8%), and interstitial and tubular cellular infiltration scores (i and t score, respectively) were significantly higher when compared with the EPC negative population (i score 0.71 ± 0.2 versus 0.2 ± 0.1 [P = 0.004]; t score 0.86 ± 0.3 versus 0.39 ± 0.1 [P = 0.02]). Likewise, arterial hyalinosis score was higher in the EPC-positive population (1.1 ± 0.2 versus 0.6 ± 0.1; P = 0.01). The presence of EPC did not seem to be significantly influenced by the cold ischemia time or by a history of delayed graft function in the whole population study.

Association of 3-Mo EPC with 12-Mo Graft Fibrosis, Progression of Fibrosis, and Deterioration of Graft Function

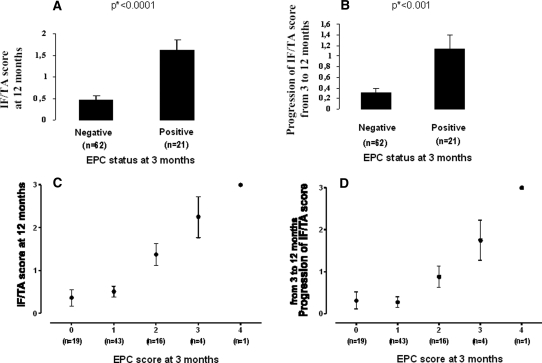

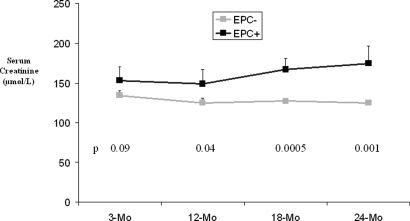

As shown in Figure 3, the 21 patients with a 3-mo EPC-positive graft (≥10% tubules showing EPC staining) had significantly higher 12-Mo IF/TA scores (1.62 ± 0.24 versus 0.47 ± 0.10; P < 0.0001; Figure 3A) as well as IF/TA progression scores (1.14 ± 0.25 versus 0.30 ± 0.1; P = 0.0003; Figure 3B) compared with those with EPC-negative grafts (n = 62). The statistical significance of the differences between the groups was confirmed by nonparametric, Mann-Whitney test. Individual 3-mo EPC scores were positively correlated with the 12-Mo IF/TA scores (n = 83, r = 0.51, P < 0.0001 with 3-mo vimentin scores, Figure 3C; and n = 75, r = 0.47, P < 0.0001 with 3-mo β-catenin scores) and with the IF/TA progression scores (n = 83, r = 0.39, P = 0.0003 with 3-mo vimentin scores, Figure 3D; and n = 75, r = 0.35, P = 0.0021 with 3-mo β-catenin scores). In the EPC-positive cohort, patients with intense EPC seemed to progress faster than those with moderate EPC (Figure 3D). Patients with grafts showing EPC had a statistically higher serum creatinine from 12 mo after transplantation (Figure 4) and a significantly lower creatinine clearance (estimated by Gault and Cockcroft index) from 18 mo after transplantation (EPCpos 49.4 ± 4.5 versus EPCneg 61.1 ± 2.3 ml/min; P = 0.01).

Figure 3.

Score of IF/TA at 12 mo and progression of IF/TA score (ΔIF/TA) between 3 and 12 mo among patients with or without EPC at 3 mo. (A and B) Grafts with EPC at 3 mo (n = 21) had a higher IF/TA score at 12 mo (A) and had significantly more progressed toward IF/TA (B) than grafts without EPC (n = 62). *P values are based from the Mann Whitney rank test. (C and D) A linear relation is shown between the score of EPC at 3 mo and the score of IF/TA at 12 mo (C) and the progression of the IF/TA score between 3 and 12 mo (D). •, Mean values with SEM.

Figure 4.

Long-term follow-up of serum creatinine in the two groups (EMT+, EMT−). P values are indicated at each time point. The presence of EPC is associated with a slow decline of graft function with time.

Risk Factors for Renal Graft Fibrosis

Donor age, 3-mo EPC, 3-mo IF/TA, and 12-mo i or t scores were significantly higher in patients with fibrotic lesions at 1 yr (12-Mo IF/TA scores ≥2) than in those with no or little fibrosis (Table 2), and these parameters were significantly and positively correlated with graft fibrotic scores at 1 yr (data not shown). Only 3-mo EPC scores and 12-mo t scores were significantly higher in progressors as compared with nonprogressors (Table 2). Three-month EPC scores, 12-mo graft i or t scores, and donor age were significantly correlated with the fibrosis progression scores (data not shown). Logistic regression analysis showed that both 3-mo EPC and 12-mo i or t scores were independently associated with 12-mo graft fibrosis with an odds ratio (OR) of 3.03 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.14 to 8.05) per additional 3-mo EPC score (P = 0.026) and an OR of 3.02 (95% CI: 1.25 to 7.3) per additional 12-mo i score (P = 0.014) after adjustment for 3-mo mild graft fibrosis (3-mo IF/TA), 3-mo and 12-mo i or t scores, and donor age (Table 3). Importantly, 3-mo EPC score was an independent risk factor for the progression of IF/TA lesions with an OR of 3.16 (95% CI 1.48 to 6.74) per additional 3-mo EPC score (P = 0.003; Table 3).

Table 2.

Comparison of clinical, biological, and histologic data between patients with or without moderate to severe graft fibrosis (IF/TA) at 12 mo and between progressors and nonprogressorsa

| Parameter | Graft Fibrosis at 12 Mo

|

Progression of Graft Fibrosis

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IF/TA <2(n = 67) | IF/TA ≥2(n = 16) | Pb | Nonprogressors(n = 50) | Progressors(n = 33) | P | |

| Donor age | 42.60 ± 1.90 | 55.90 ± 3.20 | 0.0003 | 43.50 ± 2.20 | 47.90 ± 2.80 | 0.2200 |

| Donor serum creatinine at kidney retrieval | 101.40 ± 10.00 | 91.90 ± 7.00 | 0.6900 | 98.00 ± 10.00 | 100.00 ± 13.00 | 0.8800 |

| Cold ischemia time (min) | 1028 ± 80 | 1244 ± 138 | 0.1700 | 987 ± 96 | 1198 ± 98 | 0.1400 |

| 3 Mo | ||||||

| GFR | 56.90 ± 2.00 | 48.70 ± 5.00 | 0.1100 | 56.80 ± 2.70 | 53.30 ± 3.00 | 0.4000 |

| proteinuria (mg/mmol urinary creatinine) | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.10 ± 0.05 | 0.1800 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.03 | 0.2800 |

| Banff score at 3 mo | ||||||

| interstitial inflammation score | 0.30 ± 0.08 | 0.56 ± 0.27 | 0.5500 | 0.34 ± 0.10 | 0.36 ± 0.15 | 0.8900 |

| tubulitis score | 0.46 ± 0.11 | 0.69 ± 0.30 | 0.5400 | 0.52 ± 0.14 | 0.49 ± 0.16 | 0.8700 |

| chronic interstitial fibrosis score | 0.25 ± 0.05 | 0.56 ± 0.13 | 0.0200 | 0.30 ± 0.07 | 0.33 ± 0.08 | 0.7500 |

| tubular atrophy score | 0.31 ± 0.06 | 0.69 ± 0.12 | 0.0060 | 0.32 ± 0.07 | 0.48 ± 0.09 | 0.1300 |

| EPC | ||||||

| vimentin | 0.93 ± 0.08 | 1.81 ± 0.28 | 0.0010 | 0.80 ± 0.09 | 1.55 ± 0.17 | <0.0001 |

| β-catenin | 0.84 ± 0.09 | 1.69 ± 0.31 | 0.0040 | 0.74 ± 0.10 | 1.38 ± 0.18 | 0.0010 |

| 12 Mo | ||||||

| GFR | 62.90 ± 2.40 | 47.40 ± 4.90 | 0.0100 | 61.70 ± 2.70 | 56.90 ± 3.90 | 0.3000 |

| proteinuria (mg/mmol urinary creatinine) | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.14 ± 0.10 | 0.3700 | 0.03 ± 0.06 | 0.09 ± 0.05 | 0.2200 |

| Banff score at 12 mo | ||||||

| interstitial inflammation score | 0.21 ± 0.07 | 0.94 ± 0.30 | 0.0010 | 0.22 ± 0.09 | 0.55 ± 0.17 | 0.0600 |

| tubulitis score | 0.31 ± 0.08 | 0.81 ± 0.25 | 0.0200 | 0.26 ± 0.09 | 0.64 ± 0.15 | 0.0200 |

Banff scores range from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating more severe abnormalities.

P values are based from the Mann Whitney rank test.

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of the risk factors for moderate to severe graft fibrosis (IF/TA ≥2) at 12 mo and for graft fibrosis progression (ΔIF/TA ≥1) between 3 and 12 mo

| Parameter | 12-Mo IF/TA ≥2

|

ΔIF/TA ≥1

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Donor agea | 1.070 (0.990 to 1.140) | 0.055 | 1.000 (0.970 to 1.040) | 0.720 |

| 3-Mo EPCb | 3.030 (1.143 to 8.050) | 0.026 | 3.160 (1.480 to 6.740) | 0.003 |

| 3-Mo IF/TA | 2.740 (0.580 to 12.940) | 0.203 | 0.380 (0.100 to 1.460) | 0.161 |

| 3-Mo interstitial infiltrate Banff scoreb | 1.000 (0.390 to 2.540) | 0.990 | 0.830 (0.410 to 1.700) | 0.620 |

| 12-Mo interstitial infiltrate Banff scoreb | 3.020 (1.250 to 7.300) | 0.014 | 2.050 (1.020 to 4.120) | 0.045 |

Per additional year of age.

Per additional score.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates a strong association between 3-mo EPC and 12-mo IF/TA after renal transplantation. This association is independent from the mild IF/TA already present at 3 mo and from donor age. More important, the presence of EPC was an early and independent marker to predict the progression of IF/TA lesions between 3 and 12 mo after transplantation, and it was associated with a poorer graft function from the time point of 18 mo and thereafter.

In several animal models, EMT has been demonstrated to be an effective mechanism for renal fibrogenesis.13,33–36 Antagonizing EMT with bone morphogenic protein-7 or with hepatocyte growth factor has been shown to prevent the progression of renal fibrosis or even to induce its regression.35,36 Before migrating into the interstitium, tubular epithelial cells are thought to switch from an epithelial to a mesenchymal phenotype.37 These phenotypic changes are detectable by immunohistochemistry, indicating the beginning of the EMT process; however, in this human study, we may not track these epithelial cells and are thus unable to confirm that they do actually migrate into the interstitium, become myofibroblasts, and produce ECM components. This fibrogenic mechanism in the graft kidney therefore remains speculative. In other words, the phenotypic changes we observed in tubular cells are suggestive (but not necessarily reflective) of an EMT process. Other mechanisms of renal fibrosis may be involved: When appropriately stimulated, tubular epithelial cells not only can express mesenchymal markers but also can produce TGF-β,38 PDGF,39 and connecting tissue growth factor,40 which could stimulate the proliferation of interstitial fibroblasts and the production of ECM components by a paracrine mechanism. The tubular epithelial cells can also produce chemokines,39 promoting the recruitment of monocytes, macrophages, or lymphocytes, which will stimulate interstitial fibroblasts to produce more ECM through growth factors and cytokines. Finally, stimulated tubular epithelial cells can also produce some ECM components themselves. Whatever the mechanism of renal fibrogenesis in the kidney graft, our results suggest that the presence of EPC in the kidney graft represents an activated state of tubular cells, which can be promoted by immune or nonimmune injuries and lead to graft fibrosis.

Our study does have limitations. First, in this retrospective study, only patients with two adequate sequential protocol biopsies at 3 and 12 mo and with an IF/TA score <2 on the 3-mo biopsy were included; therefore, the percentage of EPC-positive grafts at 3 mo and of IF/TA score ≥2 at 1 yr may not reflect the actual prevalence of these events in the general population of kidney transplant recipients. Still, this selected group of patients should not represent a major bias in that it does not alter the close link between early EPC and subsequent graft fibrosis. Second, we used a semiquantitative method for EPC score assessment because of the uncertainty in counting the true number of tubular epithelial cells. Banff scores are also based on semiquantitative assessment of the pathologic parameters and have been shown to be useful to classify the renal allograft lesions. In addition, to minimize the subjectivity during the analysis, the EPC scores were always quantified in a blinded manner by two morphologists and repeated three times without any knowledge of the clinical or morphologic data of the patients. Third, we studied only one mesenchymal marker, namely the expression of vimentin, which we preferred to the more conventional fibroblast-specific protein-1 (FSP-1), for technical reasons: The method of fixation of the renal core was an issue to detect FSP-1 by immunohistochemistry (our efforts were unsuccessful in routine conditions, i.e., alcohol formalin acetic acid); moreover, we had previously reported that in a few samples fixed with formaldehyde, FSP-1 was detectable but barely expressed by the time of 3 mo in the graft.26 Finally, this is an observational rather than a causation study. Even though we found a strong association between early EPC and late IF/TA or IF/TA progression, this does not prove a direct role of these phenotypically changed epithelial cells in the process of IF/TA, and it should be interpreted cautiously.

In conclusion, using sequential protocol biopsies in a cohort of renal transplant recipients, we demonstrate the predictive value of EPC for renal graft fibrosis. This early profibrogenic marker is more accurate and has a more dynamic value than any other classical marker for predicting the progression of graft fibrosis. If this result is confirmed in a general population, then we could use this well-reproductive, cheap, easily realizable biomarker on early renal protocol biopsies to screen kidney transplant patients for their potential fibrogenic risk. This biomarker could also be useful for studies designed to test the antifibrotic properties of current or new drugs.

CONCISE METHODS

Patients

Eligible patients were adults (≥18 yr of age) who received a kidney from a living or deceased donor between June 2004 and June 2005 in two Parisian centers (Hôpital Necker and Hôpital Saint-Louis). Both of these centers perform routine protocol biopsies at 3-mo and 12-mo after transplantation. Exclusion criteria were (1) the absence of available renal biopsy at both 3-mo and 12-mo as a result of a contraindication (mandatory long-term anticoagulation, morbid obesity, or high risk for bowel perforation as judged by the position of the graft by ultrasonography); (2) biopsy specimens inadequate for histologic diagnosis (<10 glomeruli and two arteries); and (3) patients who had moderate to severe lesions of IF/TA (grade ≥2 according to the Banff ’05 working classification of renal allograft pathology41) on the 3-mo biopsy sample. Routine clinical data were obtained for all patients. Proteinuria level, serum creatinine, and creatinine clearance (assessed by the Cockcroft-Gault formula) were obtained until 24 mo after transplantation.

The 3 and 12 mo, kidney graft biopsies were obtained using a biopsy gun (Monopty Bard, Covington, UK) with a 16-G needle. Renal histopathologic analysis was performed by two pathologists (J.V. and N.B.), and findings were classified according to Banff.41,42 C4d staining was not part of our routine practice during the whole length of the study, so we did not include this specific analysis.

Immunohistochemistry

EPC were detected and quantified by immunohistochemical staining of intracellular translocation of β-catenin and de novo vimentin expression by tubular epithelial cells, as described previously.26 Briefly, kidney specimens were fixed in alcohol-formalin-acetic acid. After dehydration with a graded series of ethanol and xylene, tissues were embedded in paraffin and cut into 3-μm sections. All samples were then deparaffinized; endogenous peroxidase was inactivated by incubation for 10 min at room temperature in 0.03% H2O2. Antigen retrieval was performed for 20 min at 97°C in citrate buffer (pH 6). Next, the sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with PBS containing 1 μg/ml anti–β-catenin (rabbit polyclonal antibody; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Tebu, Le-Perray-en-Yvelines, France) or 1:400 anti-vimentin (mAb V9; Zymed, In Vitrogen, Cergy-Pontoise, France). The sections were then incubated with anti-rabbit or anti-mouse antibody conjugated with peroxidase-labeled polymer (Dako, Trappes, France). Immunoreactive proteins were visualized with a 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole-containing peroxidase substrate (H2O2; Dako). Finally, the tissue sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. For negative controls, the primary antibodies were replaced by an equal concentration of rabbit or mouse IgG (Dako). For double-staining experiments, the concentration of primary antibodies was doubled, and secondary antibodies conjugated to conventional fluorochromes were used (FITC for β-catenin and TRIC for vimentin).

Semiquantitative Analysis of Immunohistochemical Staining

Semiquantitative analysis of vimentin expression and of the translocation of β-catenin from the membrane to the cytoplasm was performed in a blinded manner by Y.-C.X.-D. and J.V. and repeated three times. Sections were graded according to the proportion of tubules showing EPC as follows, as described previously26: 0, none; 1, <10%; 2, 10 to 24%; 3, 25 to 50%; and 4, >50%.

Definition of EPC, Graft Fibrosis, or Fibrosis Progression Status

As previously, we defined a positive or negative EPC graft status as being ≥10 or <10% of tubules showing EPC at 3 mo, respectively.26 We measured the IF/TA score according to the Banff ’05 report: Grade I for mild IF/TA (<25% of cortical area), grade II for moderate IF/TA (25 to 50%), and grade III for severe IF/TA (>50%).

Patients were also classified into two groups according to the presence or absence of progression of the Banff IF/TA score between 3 and 12 mo: Progressors and nonprogressors were defined by a ΔIF/TA ≥1 or <1, respectively (ΔIF/TA = 12-mo IF/TA − 3-mo IF/TA scores). All of the statuses were defined before any statistic analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Clinical, biologic, and histologic (3-mo EPC and Banff scores) data were compared between 3-mo EPC+ and EPC−, 12-mo IF/TA+ and IF/TA−, or ΔIF/TA+ and ΔIF/TA− status patients using unpaired t test. Significant differences between the groups were confirmed by Mann-Whitney rank nonparametric test when the number of patients in a group was <30. Results are presented as mean ± SE values together with P values generated by two-sided t test or by Mann-Whitney rank test. Individual 12-mo IF/TA and ΔIF/TA scores were also analyzed with clinical, biologic, and histologic data (3-mo EPC and Banff scores), assessed by linear correlation and/or spearman rank-order correlations test when the number of patients was <30. A χ2 test was used to analyze the association between certain clinical qualitative data and the 12-mo IF/TA or the progression of IF/TA. Logistic regression was used to estimate adjusted OR and 95% CI of potential risk factors on 12-mo IF/TA or on IF/TA progression. Statistical analysis was carried out using Stata 8 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX). Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

DISCLOSURES

None.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Arthur Haustant, former director of Tenon Hospital, for strong support to our research activity and the Agence de Biomédecine for financial contribution to this research work.

We thank Felicity Neilson (Matrix Consultants) for the English editing.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cornell LD, Colvin RB: Chronic allograft nephropathy. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 14: 229–234, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harris RC, Neilson EG: Toward a unified theory of renal progression. Annu Rev Med 57: 365–380, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Annual report. Agence Biomedecine, Paris, 2006, p 153. Available at: http://www.agence-biomedecine.fr/fr/experts/doc/rapp-synth2006.pdf. Accessed August 20, 2007

- 4.Mannon RB: Therapeutic targets in the treatment of allograft fibrosis. Am J Transplant 6: 867–875, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chapman JR, O'Connell PJ, Nankivell BJ: Chronic renal allograft dysfunction. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 3015–3026, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roos-van Groningen MC, Scholten EM, Lelieveld PM, Rowshani AT, Baelde HJ, Bajema IM, Florquin S, Bemelman FJ, de Heer E, de Fijter JW, Bruijn JA, Eikmans M: Molecular comparison of calcineurin inhibitor-induced fibrogenic responses in protocol renal transplant biopsies. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 881–888, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li B, Hartono C, Ding R, Sharma VK, Ramaswamy R, Qian B, Serur D, Mouradian J, Schwartz JE, Suthanthiran M: Noninvasive diagnosis of renal-allograft rejection by measurement of messenger RNA for perforin and granzyme B in urine. N Engl J Med 344: 947–954, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nankivell BJ, Borrows RJ, Fung CL, O'Connell PJ, Allen RD, Chapman JR: The natural history of chronic allograft nephropathy. N Engl J Med 349: 2326–2333, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neilson EG: Mechanisms of disease: Fibroblasts—A new look at an old problem. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol 2: 101–108, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rossini M, Cheunsuchon B, Donnert E, Ma LJ, Thomas JW, Neilson EG, Fogo AB: Immunolocalization of fibroblast growth factor-1 (FGF-1), its receptor (FGFR-1), and fibroblast-specific protein-1 (FSP-1) in inflammatory renal disease. Kidney Int 68: 2621–2628, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iwano M, Neilson EG: Mechanisms of tubulointerstitial fibrosis. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 13: 279–284, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalluri R, Neilson EG: Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and its implications for fibrosis. J Clin Invest 112: 1776–1784, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Y: Epithelial to mesenchymal transition in renal fibrogenesis: Pathologic significance, molecular mechanism, and therapeutic intervention. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 1–12, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strutz F, Neilson EG: New insights into mechanisms of fibrosis in immune renal injury. Springer Semin Immunopathol 24: 459–476, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thiery JP: Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer 2: 442–454, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thiery JP: Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and pathologies. Curr Opin Cell Biol 15: 740–746, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iwano M, Plieth D, Danoff TM, Xue C, Okada H, Neilson EG: Evidence that fibroblasts derive from epithelium during tissue fibrosis. J Clin Invest 110: 341–350, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim KK, Kugler MC, Wolters PJ, Robillard L, Galvez MG, Brumwell AN, Sheppard D, Chapman HA: Alveolar epithelial cell mesenchymal transition develops in vivo during pulmonary fibrosis and is regulated by the extracellular matrix. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 13180–13185, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeisberg M, Yang C, Martino M, Duncan MB, Rieder F, Tanjore H, Kalluri R: Fibroblasts derive from hepatocytes in liver fibrosis via epithelial to mesenchymal transition. J Biol Chem 282: 23337–23347, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rastaldi MP, Ferrario F, Giardino L, Dell'Antonio G, Grillo C, Grillo P, Strutz F, Müller GA, Colasanti G, D'Amico G: Epithelial-mesenchymal transition of tubular epithelial cells in human renal biopsies. Kidney Int 62: 137–146, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishitani Y, Iwano M, Yamaguchi Y, Harada K, Nakatani K, Akai Y, Nishino T, Shiiki H, Kanauchi M, Saito Y, Neilson EG: Fibroblast-specific protein 1 is a specific prognostic marker for renal survival in patients with IgAN. Kidney Int 68: 1078–1085, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vongwiwatana A, Tasanarong A, Rayner DC, Melk A, Halloran PF: Epithelial to mesenchymal transition during late deterioration of human kidney transplants: The role of tubular cells in fibrogenesis. Am J Transplant 5: 1367–1374, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Djamali A: Oxidative stress as a common pathway to chronic tubulointerstitial injury in kidney allografts. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F445–F455, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tyler JR, Robertson H, Booth TA, Burt AD, Kirby JA.: Chronic allograft nephropathy: Intraepithelial signals generated by transforming growth factor-beta and bone morphogenetic protein-7. Am J Transplant 6: 1367–1376, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robertson H, Ali S, McDonnell BJ, Burt AD, Kirby JA: Chronic renal allograft dysfunction: The role of T cell-mediated tubular epithelial to mesenchymal cell transition. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 390–397, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hertig A, Verine J, Mougenot B, Jouanneau C, Ouali N, Sebe P, Glotz D, Ancel PY, Rondeau E, Xu-Dubois YC: Risk factors for early epithelial to mesenchymal transition in renal grafts. Am J Transplant 6: 2937–2946, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frenette PS, Wagner DD: Adhesion molecules: Part 1. N Engl J Med 334: 1526–1529, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Behrens J, von Kries JP, Kuhl M, Bruhn L, Wedlich D, Grosschedl R, Birchmeier W: Functional interaction of beta-catenin with the transcription factor LEF-1. Nature 382: 638–642, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bienz M: Beta-catenin: A pivot between cell adhesion and Wnt signalling. Curr Biol 15: R64–R67, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Masszi A, Fan L, Rosivall L, McCulloch CA, Rotstein OD, Mucsi I, Kapus A: Integrity of cell-cell contacts is a critical regulator of TGF-beta 1-induced epithelial-to-myofibroblast transition: Role for beta-catenin. Am J Pathol 165: 1955–1967, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grunert S, Jechlinger M, Beug H: Diverse cellular and molecular mechanisms contribute to epithelial plasticity and metastasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 4: 657–665, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muramatsu M, Miyagi M, Ishikawa Y, Aikawa A, Mizuiri S, Ohara T, Ishii T, Hasegawa A: Estimation of damaged tubular epithelium in renal allografts by determination of vimentin expression. Int J Urol 11: 954–962, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang G, Kernan KA, Collins SJ, Cai X, López-Guisa JM, Degen JL, Shvil Y, Eddy AA: Plasmin(ogen) promotes renal interstitial fibrosis by promoting epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition: Role of plasmin-activated signals. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 846–859, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang J, Shultz RW, Mars WM, Wegner RE, Li Y, Dai C, Nejak K, Liu Y: Disruption of tissue-type plasminogen activator gene in mice reduces renal interstitial fibrosis in obstructive nephropathy. J Clin Invest 110: 1525–1538, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang J, Liu Y: Delayed administration of hepatocyte growth factor reduces renal fibrosis in obstructive nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 284: F349–F357, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zeisberg M, Hanai J, Sugimoto H, Mammoto T, Charytan D, Strutz F, Kalluri R: BMP-7 counteracts TGF-beta1-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and reverses chronic renal injury. Nat Med 9: 964–968, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neilson EG: Plasticity, nuclear diapause, and a requiem for the terminal differentiation of epithelia. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 1995–1998, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang XL, Selbi W, de la Motte C, Hascall V, Phillips A: Renal proximal tubular epithelial cell transforming growth factor-beta1 generation and monocyte binding. Am J Pathol 165: 763–773, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burton CJ, Combe C, Walls J, Haris KP: Secretion of chemokines and cytokines by human tubular epithelial cells in response to proteins. Nephrol Dial Transplant 14: 2628–2633, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Okada H, Kikuta T, Kobayashi T, Inoue T, Kanno Y, Takigawa M, Sugaya T, Kopp JB, Suzuki H: Connective tissue growth factor expressed in tubular epithelium plays a pivotal role in renal fibrogenesis. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 133–143, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Solez K, Colvin RB, Racusen LC, Sis B, Halloran PF, Birk PE, Campbell PM, Cascalho M, Collins AB, Demetris AJ, Drachenberg CB, Gibson IW, Grimm PC, Haas M, Lerut E, Liapis H, Mannon RB, Marcus PB, Mengel M, Mihatsch MJ, Nankivell BJ, Nickeleit V, Papadimitriou JC, Platt JL, Randhawa P, Roberts I, Salinas-Madriga L, Salomon DR, Seron D, Sheaff M, Weening JJ: Banff ’05 Meeting Report: Differential diagnosis of chronic allograft injury and elimination of chronic allograft nephropathy (′CAN′). Am J Transplant 7: 518–526, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Racusen LC, Solez K, Colvin RB, Bonsib SM, Castro MC, Cavallo T, Croker BP, Demetris AJ, Drachenberg CB, Fogo AB, Furness P, Gaber LW, Gibson IW, Glotz D, Goldberg JC, Grande J, Halloran PF, Hansen HE, Hartley B, Hayry PJ, Hill CM, Hoffman EO, Hunsicker LG, Lindblad AS, Yamaguchi Y: The Banff 97 working classification of renal allograft pathology. Kidney Int 55: 713–723, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]