Abstract

N-Glycosylation starts in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) where a 14-sugar glycan composed of three glucoses, nine mannoses, and two N-acetylglucosamines (Glc3Man9GlcNAc2) is transferred to nascent proteins. The glucoses are sequentially trimmed by ER-resident glucosidases. The Glc3Man9GlcNAc2 moiety is the substrate for oligosaccharyltransferase; the Glc1Man9GlcNAc2 and Man9GlcNAc2 intermediates are signals for glycoprotein folding and quality control in the calnexin/calreticulin cycle. Here, we report a novel membrane-anchored ER protein that is highly conserved in animals and that recognizes the Glc2-N-glycan. Structure determination by nuclear magnetic resonance showed that its luminal part is a carbohydrate binding domain that recognizes glucose oligomers. Carbohydrate microarray analyses revealed a uniquely selective binding to a Glc2-N-glycan probe. The localization, structure, and binding specificity of this protein, which we have named malectin, open the way to studies of its role in the genesis, processing and secretion of N-glycosylated proteins.

INTRODUCTION

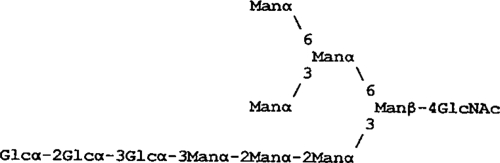

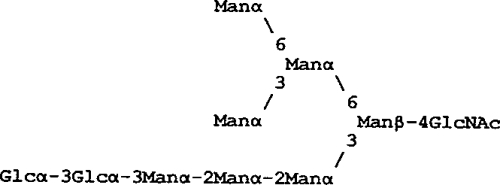

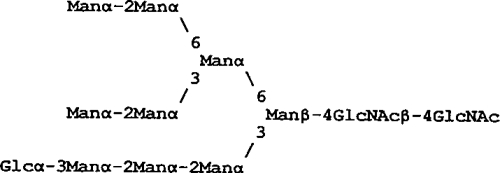

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) contains a battery of proteins with essential roles in the biogenesis of glycoproteins most of which are N-glycosylated (Apweiler et al., 1999). Despite the high diversity of N-glycans in mature glycoproteins, protein glycosylation starts in the ER with a series of steps conserved in the majority of eukaryotes. It is here that a 14-sugar glycan composed of three glucoses, nine mannoses, and two N-acetylglucosamines, Glc3Man9GlcNAc2 (see Figure 4E), is transferred by oligosaccharyltransferase (OST) from the lipid-linked sugar donor Glc3Man9GlcNAc2-diphosphate dolichol to selected asparagines at canonical sequons N-X-T/S of the nascent proteins (Dejgaard et al., 2004; Helenius and Aebi, 2004). The terminal glucoses and one mannose residue of the N-glycan are sequentially trimmed by glycosidases in the ER. Thereafter, the N-glycan is differentially processed in the Golgi apparatus by a series of glycosidases and glycosyltransferases, giving rise to a diversity of cell-, tissue-, and species-specific sequences of glycoprotein N-glycans. These bear a range of intra- and extracellular recognition motifs and, in addition, they contribute to solubility and stability of the proteins.

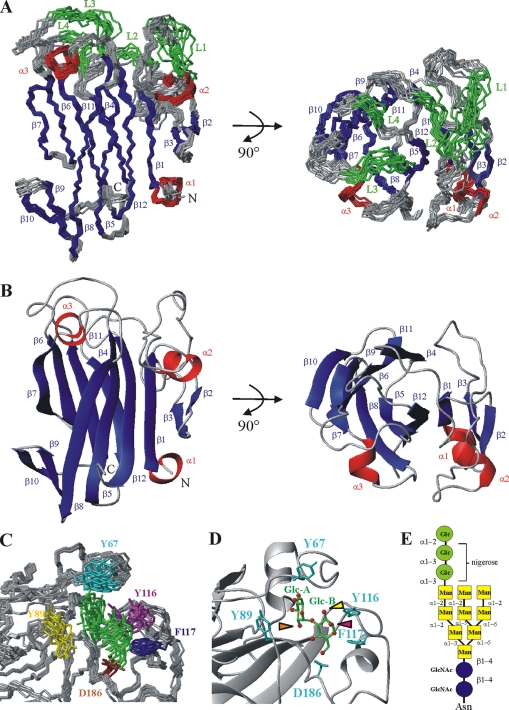

Figure 4.

Structure of the main domain of malectin and of the malectin–nigerose complex. (A) Ensemble of the 10 lowest energy structures (out of 100 calculated) after water refinement. The four loops (L1–L4), which could only be assigned in the presence of a carbohydrate ligand, are highlighted in green: L1, G62-G68; L2, T86-N90; L3, E114-A118; and L4, Y185-N187. (B) Ribbon representation of malectin. Secondary structure elements are colored in red and blue for α-helices (α1–α3) and β-strands (β1–β12), respectively. (C) Ensemble of the 10 lowest energy structures of the malectin–nigerose complex. Only the ligand-binding pocket is shown. The four aromatic residues and D186 mediating the interaction are relatively well defined. Yellow, Y89; cyan, Y67; magenta, Y116; blue, F117; and brown, D186. Nigerose is presented in green (D). Detailed view of the malectin–nigerose interaction. Nigerose is sandwiched by Y67, Y89, Y116, and F117. The nonreducing and reducing residues of nigerose are labeled Glc-A and Glc-B, respectively. Oxygen atoms of the carbohydrate are highlighted as red spheres. The orange arrow points to the oxygen atom of the C-2 hydroxyl group of Glc-A, where the outermost glucose residue of Glc3-N-glycan would be attached. The magenta arrow highlights the oxygen atom of the C-1 hydroxyl group of Glc-B (α-form), where the polymannose part of the Glc2-N-glycan would be continued. The oxygen atom of the equatorial C-2 hydroxyl group of Glc-B is marked by the yellow arrow. If at the Glc-B position there was a mannose residue, as in Glc1-N-glycan, the stacking interaction would be hindered as there would be an axial hydroxyl group pointing toward Y116 and F117. (E) Schematic drawing of the Glc3-Man9-N-glycan. Glucose is depicted as green circles, mannose as yellow squares, and GlcNAc as blue circles.

Trimming of the two outer glucoses from the Glc3-N-glycan gives rise to the monoglucosylated Glc1-N-glycan; this enables the nascent glycoproteins to bind to the chaperone proteins calnexin and calreticulin, which assist in the maturation and quality control of glycoproteins before they exit the ER. Cleavage of the remaining glucose residue releases the glycoproteins from these chaperones. Provided folding is complete, the glycoproteins are transferred to the Golgi apparatus. If not, uridine 5′-diphosphate-Glc:glycoprotein glucosyltransferase reglucosylates the glycoprotein and starts a new round of chaperone-assisted folding (Sousa et al., 1992).

After transfer of the Glc3-N-glycan to a polypeptide chain, glucosidase I cleaves immediately the outermost glucosidic bond (Deprez et al., 2005). The middle glucose is excised by glucosidase II (GII). Despite the recruitment of GII to the nascent polypeptide chain as soon as a Glc2-N-glycan intermediate is available, the cleavage of the middle glucose residue was found to be delayed until a second glycan was attached to the nascent polypeptide (Deprez et al., 2005). Helenius and coworkers have proposed that the delay is related to the need for an activation of GII elicited by its binding at least transiently to a second N-glycan that is later added to the same polypeptide. In this model GII binds to the 6′pentamannosyl branch of the second glycan via a domain that has homology with the mannose-6-phosphate receptors; the two glycans must be close enough for GII to bind to one glycan and trim the other (Deprez et al., 2005).

Here, we report on a type I membrane-anchored ER protein, which we initially identified in Xenopus laevis pancreas, but later found to be widely distributed in various tissues. The protein (UniProt accession no. Q6INX3) is homologous to the product of the human gene KIAA0152 of hitherto unknown function and is well conserved in animals. We describe nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) studies revealing a close structural similarity to carbohydrate binding modules (CBMs) of bacterial glycosylhydrolases, and NMR-based ligand-screening studies showing binding of the protein to maltose and related oligosaccharides, on the basis of which we designated the protein “malectin.” Insight was gained into the endogenous ligand for malectin from carbohydrate microarray analyses that contained diverse glycans of mammalian types. These revealed an intense and selective binding to a Glc2-high-mannose N-glycan.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Whole Mount In Situ Hybridization

The X. laevis malectin full-length cDNA clone was isolated from an adult pancreas cDNA library (Afelik et al., 2004). Whole mount in situ hybridization to determine the spatial distribution of malectin transcripts in X. laevis embryos was carried out by standard procedures as described in Supplemental Material. Images of embryos were taken with an Olympus SZX12 camera (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and processed with Adobe Photoshop CS (Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA).

Semiquantitative Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

To obtain a temporal malectin gene expression profile in X. laevis total RNA was extracted from embryos of different developmental stages and adult tissues by using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Paisley, United Kingdom) according to the manufacturer's protocol. After DNaseI digestion, reverse transcription using PowerScript reverse transcriptase (Clonetech, Mountain View, CA) and random hexamer primer (Invitrogen), gene expression levels were analyzed by PCR using gene-specific primers designed on the basis of the X. laevis sequence NM_001091743 (Xp150-RT for 5′-ACGACAACCCCAAAGTATG-3′, Xp150-RT rev: 5′-CCGAAGGCCACCAGGAT-3′; 60°C; 30 cycles). Malectin gene expression was compared with pancreas-specific protein disulfide isomerase xPDIp (xPDIp-for: 5′-GGAGGAAAGAGGGACCAA-3′, xPDIp-rev: 5′-GCGCCAGGGCAAAAGTG-3′; 60°C; 30 cycles; Afelik et al., 2004) and X. laevis histone H4 (H4-for: 5′-CGGGATAACATTCAGGGTATCACT-3′, H4-rev: 5′-ATCCATGGCGGTAACTGTCTTCCT-3′; 56°C; 26 cycles; Niehrs et al., 1994).

Transient Transfection Experiments

U-2 OS cells (ATCC HTB-96) were transfected with 0.5 μg of plasmid encoding the FLAG-tagged X. laevis malectin proteins by using FuGENE6 (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol. After 24 h, cells were fixed for 20 min with 3% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) followed by quenching with 30 mM glycine before permeabilization with 0.1% (wt/vol) Triton X-100. Antibody incubations were carried out in PBS for 20 min with mouse anti-FLAG M2 (1:500; Sigma Chemical, Poole, Dorset, United Kingdom) and rabbit-anti-calnexin (1:500; Stressgen) antibodies. Anti-mouse-Cy3 (1:800; GE Healthcare, Chalfont St. Giles, United Kingdom) and anti-rabbit-Alexa 488 (1:800; Invitrogen) were used as secondary antibodies, respectively. After mounting samples in Mowiol, images were acquired on an Axiovert 200 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) with standard filter sets and processed with Adobe Photoshop CS.

Expression Constructs for Structure Determination and Interaction Studies

The globular segment of malectin (amino acids [AA] 27-213) was used for structural analysis and interaction studies. It was cloned into a modified pET-24d vector containing an N-terminal His6-tag fused to a Z-tag removable through cleavage with tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease for NMR-related studies. The malectin construct was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 [DE3] and purified on nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA)-agarose. Purification step on a Superdex-200 gel filtration was omitted when initial studies showed that the protein did not elute from the column. The fusion tag was cleaved by TEV-protease, and a second purification step was carried out on Ni-NTA-agarose to remove both the fusion tag and the His6-tagged TEV protease. For carbohydrate microarray analysis, the malectin construct was subcloned into a modified pET-24d with a noncleavable His6-tag.

NMR Experiments

E. coli BL21 [DE3] cells were grown in either LB, 15N-enriched minimal medium or 15N–13C-enriched minimal medium. Protein spectra were acquired at 22°C in 20 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 6.8, 150 mM KCl, and 2 mM dithiothreitol at a protein concentration of 0.8 mM. Standard triple resonance backbone and side chain experiments [HNCA, HNCACB, CBCA(CO)NH, H(CCO)NH-TOCSY, (H)C(CO)NH-TOCSY, HCCH-TOCSY] were acquired on a DRX600 spectrometer (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany) equipped with a cryoprobe. 15N-Heteronuclear single quantum correlation (HSQC)-nuclear Overhauser enhancement spectroscopy (NOESY) and 13C-HMQC-NOESY spectra were recorded at 900 MHz, with 80-ms mixing times. Data were processed with NMRPIPE (Delaglio et al., 1995) and analyzed using NMRVIEW (Johnson and Blevins, 1994).

The resonances of the sugars were assigned using a combination of HSQC, TOCSY, HSQC-TOCSY, and HMBC experiments on samples in D2O. The resonance assignment of the free ligands could be directly used for group epitope mapping by using the saturation transfer difference (STD) spectra and assignment of the intermolecular NOESY experiment for the complex structure calculation due to fast exchange conditions and the high sugar excess used with the protein samples (five-fold excess). All spectra were referenced according to Wishart et al. (1995).

STD Experiments

For STD experiments (Mayer and Meyer, 1999) protein samples of 20 μM were used with a 100-fold excess of sugar. The on-resonance frequency used for presaturation of the protein signals was set to 0.8 ppm, whereas the off-resonance irradiation was applied at −40 ppm where no NMR resonances were present. For the suppression of background protein signals, a 30-ms T1ρ spinlock as a relaxation filter was used with field strength of 5 KHz. For the epitope mapping analysis, STD signals were assigned using the assignment of the free ligands (Supplemental Table S4) as described above. In addition STD-TOCSY and STD-HSQC spectra were acquired when necessary. The strong overlap in the ring proton region precluded quantitative evaluation of the STD signals.

Structure Calculation

Structures were calculated with ARIA1.2/CNS (Linge et al., 2001) on the basis of 4426 experimentally derived nuclear Overhauser effect (NOE) restraints. Additional 99 dihedral restraints derived from TALOS (Cornilescu et al., 1999) analysis of the chemical shifts, and 66 hydrogen bonds identified on the basis of characteristic NOE patterns were added. Parameters (bond lengths, angles, and dihedrals) describing the complex of nigerose with malectin were generated based on the general carbohydrate parameter and topology files of CNS (Linge et al., 2001), and dihedral and improper angles were modified according to needs. α-Nigerose was attached to malectin in the course of the calculation through 31 NOEs that were determined in 13C-edited half-filtered experiments, with a mixing time of 150 ms. The φ (H1-C1-O-Cx) and ϕ (C1-O-Cx-Hx) angles of the glycosidic bond were not specifically defined.

Carbohydrate Microarray Analyses

Isolation and purification of the Glc1-, Glc2-, and Glc3-N-glycans, and the preparation and characterization of the probes generated from them for arraying are described in the Supplemental Materials and Methods. Microarrays of a total of 335 lipid-linked oligosaccharide probes, neoglycolipids (NGLs) and glycolipids (Supplemental Table S6), were robotically generated, and microarray analyses with His-tagged malectin were performed essentially as described (Palma et al., 2006), except that the protein was pre-complexed with mouse monoclonal anti-poly-histidine and biotinylated anti-mouse IgG antibodies. Details are in Supplemental Materials and Methods.

RESULTS

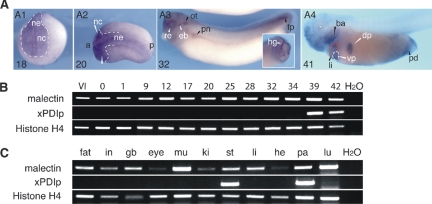

Wide Distribution of the Malectin Gene in X. laevis Tissues

We identified the malectin gene during a cDNA library screen of the X. laevis pancreas aimed at finding novel marker genes. By whole mount in situ hybridization, we observed that in the X. laevis embryo, malectin mRNA was expressed in numerous tissues throughout development (Figure 1A). Moreover, by semiquantitative RT-PCR, we detected malectin mRNA in the X. laevis oocyte, indicating that it is maternally expressed (Figure 1B), and in the adult, in all tissues tested (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Broad expression of malectin in embryonic and adult X. laevis. (A) Analysis of embryos by whole mount in situ hybridization showing malectin expression in the anterior neuroectoderm (ne) and neural crest (nc) at stages 18 and 20 (A1, A2), and at later stages, e.g., 32, in the hatching gland (hg), retina (re), otic vesicle (ot), epibranchial placodes (eb), pronephros (pn), and the tail tip (tp); anterior (a); posterior (p). At stage 41 (A4), transcripts are detected in the liver (li), dorsal and ventral pancreas (dp and vp), branchial arches (ba), and the proctodeum (pd). (B) Analysis of embryonic expression of malectin by RT-PCR showing expression in the oocyte (stage VI) and continued expression throughout development, and the contrasting expression of protein disulfide isomerase, xPDIp, only from late tadpole stage 39 onward. Abbreviations: stage VI oocyte (VI); unfertilized egg (0) and fertilized egg (1). (C) The expression analysis in adult tissue by semiquantitative RT-PCR showing a broad distribution of malectin in comparison with xPDIp, which is detected in pancreas and stomach only. Additional abbreviations not defined in A: gall bladder (gb); heart (he); intestine (in); kidney (ki); lung (lu); muscle (mu); pancreas (pa); stomach (st).

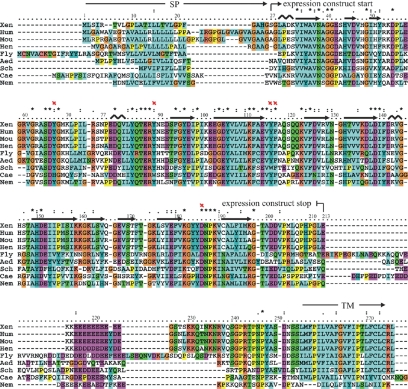

Conservation of Malectin Sequence in Animals

A database search annotated the malectin protein (UniProt accession no. Q6INX3) to a hypothetical human gene of unknown function KIAA0152. In a quest for structure–function insight, the deduced X. laevis malectin protein sequence and that for the human homologue were subjected to a range of bioinformatics tools (see Supplemental Material). Protein domain databases such as SMART (Letunic et al., 2006) and Pfam (Finn et al., 2006) predict a type I membrane protein: an N-terminal signal peptide (AA 1-26) and a C-terminal transmembrane helix (AA 255-274). Immediately preceding the C-terminal membrane anchor, the segment in the residue range ∼210–250 is predicted by IUPRED (Dosztányi et al., 2005) to be a natively disordered polypeptide, coinciding with a highly charged sequence segment. The remainder of the protein has a strong globular signature, implying the presence of an ∼190 residue globular domain (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Sequence alignment of malectin proteins in animals. Malectin proteins are composed of an N-terminal signal peptide (SP, AA 1-26), a C-terminal transmembrane helix (TM; AA 255-274) and a highly conserved central part of ∼190 residues followed by an acidic, glutamate-rich region. The secondary structure elements derived from the experimental structure (see Figure 4A) are shown on top of the amino acid sequence; and the four aromatic residues (Y67, Y89, Y116, and F117) and D186 mediating the carbohydrate interaction are marked by red crosses (Xen, Xenopus laevis [100/100]; Hum, Homo sapiens [89/95]; Mou, Mus musculus [86/94]; Hen, Gallus gallus [84/96], Fly, Drosophila melanogaster [41/58]; Aed, Aedes aegyptii [44/62]; Cae, Caenorhabditis elegans [36/58]; Sch, Schistosoma japonicum [42/59]; Nem, Nematostella vectensis [51/69]). The bracketed numbers represent the percentage amino acid conservation in comparison with the X. laevis malectin protein (identities/similarities).

BLAST searches (Altschul et al., 1997) of protein databases revealed well conserved homologues of malectin in animals (Figure 2). There is generally a single copy per proteome, except in polyploids. The aligned animal proteins seem to be colinear with the same modular architecture, including the hydrophobic N and C termini and the charged segment.

PSI-BLAST searches were undertaken with the sequence region 28-210. These revealed homologous proteins in some ciliates and apicomplexans and identified a highly divergent but clearly homologous domain in certain plant receptor like kinases (RLKs; Shiu and Bleecker, 2003). This novel domain was found in two locations, either membrane juxtaposed or remote (Supplemental Figure S1).

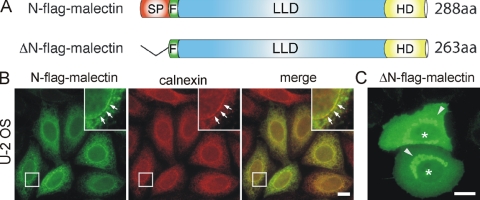

Transient Transfection Experiments with FLAG-tagged Malectin Show ER Localization of the Protein

To characterize the subcellular localization of malectin, transient transfection experiments in U-2 OS cells were performed using FLAG-tagged malectin constructs (Figure 3A). Malectin was observed to localize in a reticular pattern (Figure 3B, green) reminiscent of the ER. Costaining the cells with antibodies against the ER-resident protein calnexin (Figure 3B, red) indicated a strong degree of overlap between the two proteins, suggesting malectin to be localized to the ER. Transfection of a malectin construct lacking the first 26 AA corresponding to the predicted signal peptide, ΔN-FLAG-malectin, resulted in a cytoplasmic distribution of the protein (Figure 3C), indicating that this sequence is likely to be responsible for targeting the protein to the ER. The truncated version ΔN-FLAG-malectin seemed to diffuse also into the nucleus, probably due to its small size (∼28 kDa). In addition, protein aggregates were visible, most likely due to the presence of the hydrophobic C-terminal domain (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

ER localization of malectin. (A) Schematic drawing of the FLAG-tagged malectin constructs used for transient transfection experiments. N-FLAG-malectin represents the full-length protein including a FLAG-tag (F) between the predicted N-terminal signal peptide (red, SP; AA 1-26) and the conserved lectin-like domain (blue, LLD; AA 27-213) that is followed by a hydrophobic C-terminal domain (yellow, HD; AA 255-274). The deletion construct ΔN-FLAG-malectin lacks the N-terminal SP. (B) Immunofluorescence analysis of U-2 OS cells for FLAG-tagged malectin (green) and the ER marker calnexin (red) showing that malectin and calnexin colocalize in ER structures (arrows indicate presence of both markers in the nuclear envelope). (C) Cytoplasmic localization of ΔN-FLAG-malectin after deletion of the predicted N-terminal signal peptide. Note that ΔN-FLAG-malectin also diffuses to the nucleus (asterisks) and can be found in protein aggregates (arrow heads). Bar, 10 μm.

Structure Determination of the Globular Domain of Malectin Reveals Similarity to Prokaryotic CBMs

The predicted globular segment in malectin and its striking conservation in animals prompted us to determine its structure by NMR spectroscopy. The construct showed a highly dispersed 1H-15N HSQC spectrum typical of a globular folded domain. Structure calculation showed that the globular segment (AA 28-201) forms a compact domain with two elongated β-sheets packed onto each other. Three short α-helices flank the core β-sandwich (Figure 4, A and B). Several neighboring loop residues exhibited marked line-broadening of HN resonances possibly because of some motion of these long loops. Interestingly, these regions are all localized at one site of the domain (Figure 4A, loops are highlighted in green), and they were subsequently identified as the carbohydrate binding region. Structural statistics are in Supplemental Table S1.

A search with MSD-Fold (www.ebi.ac.uk/msd-srv/ssm/) identified the most similar structures in the PDB data bank. Top hits were the structures of a number of prokaryotic CBMs (Boraston et al., 2004; RmsD ∼3 Å, Z-score ∼7; Supplemental Table S2) as well as that of the carbohydrate recognition domain of Fbs1, a ubiquitin ligase (Mizushima et al., 2004). The β-sandwich fold in the central domain of malectin is also predominant among CBMs and a variety of other lectins, prominent members being the galectins and calnexin (Schrag et al., 2001). Malectin differs from the currently known lectins, however, in having α-helices and extensions of the β-sandwich arrangement, which would classify it as a new type of carbohydrate recognition domain.

NMR- and Isothermal Calorimetry-based Ligand Screening Reveals Interaction with Glucose Oligomers

Considering the aforementioned structural similarities of the central domain of malectin to CBMs and other lectins, and the tight binding of the protein to a gel filtration column containing dextran (see Supplemental Material), we performed ligand-screening experiments by NMR, with various common mono- and oligosaccharides (Supplemental Table S3). Through chemical shift perturbation experiments, we determined that di- or higher oligomers of glucose were bound by malectin. Results are summarized in Supplemental Table S3. These included maltose (Glcα1-4Glc), maltotriose, maltotetraose and maltoheptaose, nigerose (Glcα1-3Glc), kojibiose (Glcα1-2Glc), cellobiose (Glcβ1-4Glc), isomaltose [(Glcα1-6Glc) (the main building block of dextran], all of which caused similar secondary chemical shifts. Binding was not detectable to glucose monomer or to the other mono and disaccharides tested (Supplemental Table S3).

For further insight into malectin–ligand interactions, we performed STD NMR experiments with glucose and five glucose disaccharides individually in the presence of malectin (Figure 5). This experiment relies on the transfer of magnetization from protons located in the protein binding pocket to those protons of the ligand, which are in the immediate proximity of the binding site. Thus, characterization of the binding epitopes (reviewed by Meyer and Peters, 2003) is possible. Provided the ligand has a relatively fast off-rate (normally the case at KD values ranging from 0.1 μM to 10 mM), the relative height of the STD signals reflects the strength of the interaction.

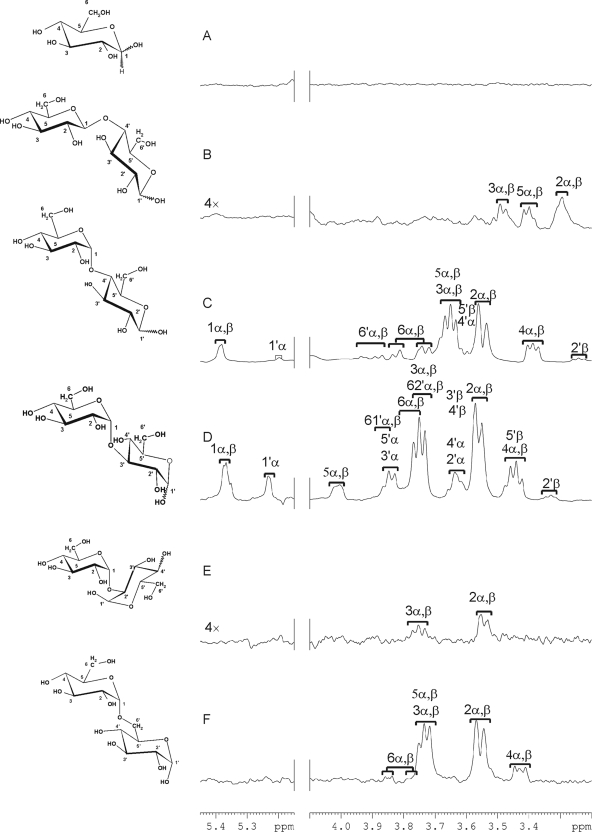

Figure 5.

One dimensional STD spectra for glucose and glucose disaccharides: glucose (A), cellobiose (B), maltose (C) nigerose (D), kojibiose (E), and isomaltose (F). Structures of the tested carbohydrates are depicted on the left of the corresponding spectra. α and β denote the stereoisomers of the anomeric center of the reducing-end glucose ring. The ring protons of the nonreducing residues are labeled 1–6, and those of the reducing residues 1′–6′. Assignment tables of the carbohydrate ligands are in Supplemental Table S4.

In the STD spectra (Figure 5), strong signals were detected for maltose (Figure 5C), nigerose (Figure 5D), and isomaltose (Figure 5F), whereas the signals detected with cellobiose and kojibiose were relatively weak (Figure 5, B and E). In general, resonances of glucose residues at the nonreducing ends of the disaccharides were two- to threefold higher than those at the reducing ends, implying that these made closer contacts with the protein. Glucose did not give any STD signals (Figure 5A), which is in agreement with the chemical shift perturbation experiments, suggesting a lack of binding of malectin to the monosaccharide.

Isothermal titration calorimetry was performed with maltose, nigerose, kojibiose, and glucose as an independent analysis method that enables a precise measurement of dissociation constants (Supplemental Figure S2). The order of KD values was 26.3 ± 0.7 μM for nigerose, 50 ± 0.5 μM for maltose, and 210 ± 6 μM for kojibiose. The KD value of glucose could not be determined due to its low affinity.

Among the ligands identified in this way neither maltose nor isomaltose seem to have a physiological role, because they do not occur in the ER. However, glucose residues do occur on the precursors and early forms of N-glycans in the ER and the sequence of the diglucose cap of the Glc2-N-linked glycan corresponds to that of nigerose (Figure 4E). This hinted at the possibility that malectin recognizes one or other of the Glc1-3-N-glycans.

The Structure of the Malectin–Nigerose Complex Explains the Specificity for Glucose Oligosaccharides

To better understand the specificity of interaction between malectin and nigerose, we sought to determine the structure of the complex (structural statistics are in Supplemental Table S5). Several contacts (NOEs) between the central domain of malectin and nigerose could be identified in NOESY spectra. These involved four aromatic systems, Y67, Y89, Y116, and F117 (Supplemental Figure S3), and both glucose rings of nigerose. Structure calculations including these protein–ligand NOEs revealed that nigerose was sandwiched by the four aromatic residues (Figure 4, C and D).

Y89 stacks against the A face of the nonreducing end glucose residue; the A face is defined as the face on which the carbons are numbered in clockwise arrangement. Y67 is in contact with the C6-CH2 group of this glucose ring. F117 makes hydrophobic contacts with the edge of the A face of the reducing end glucose, Y116 stacks against the A face of the reducing end glucose, but also has weak contacts with the B face of the nonreducing end glucose; the B face is defined as the face on which the carbons are numbered in anticlockwise arrangement. The side chain of D186 complements the interface through hydrogen bonding with the hydroxyl groups of the reducing end glucose.

The mode of ligation of malectin is reminiscent of prokaryotic carbohydrate binding modules (Boraston et al., 2004). Families 4, 6, 9, and 22 of the prokaryotic carbohydrate binding modules likewise use aromatic residues to interact with their respective carbohydrate ligands. Several structures of these families were among the best hits in our structure comparison search (Supplemental Table S2).

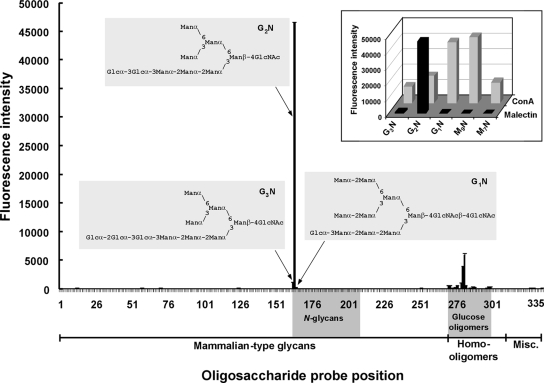

Carbohydrate Microarray Analyses Reveal the Glc2-N-Glycan As the Preferred Ligand for Malectin

To gain further insight into the range of carbohydrate sequences recognized by the central domain of malectin, microarray analyses were carried out with 335 natural and synthetic oligosaccharide probes, 268 of them representative of mammalian type sequences (Supplemental Table S6). These encompassed diverse N-glycans (high-mannose-type, the Glc1-3, and neutral and sialylated complex-type), O-glycans, blood group-related sequences (A, B, H, Lewisa, Lewisb, Lewisx, and Lewisy) on linear or branched backbones and their sialylated and/or sulfated analogs, gangliosides, and oligosaccharide fragments of glycosaminoglycans and polysialic acid. Also included were homo-oligomers of glucose and of other monosaccharides. The microarray analyses were performed at a range of malectin concentrations, 0.5–20 μg/ml, not only to identify the preferred ligand(s) but also to examine details of the binding specificity toward gluco-oligosaccharides, which gave relatively low binding signals.

Among the diverse repertoire of oligosaccharide sequences included in the microarrays, malectin binding was detected only to those terminating with glucose, as predicted from the NMR data. By far the most prominent binding, however, was to the diglucosylated, Glc2-N-glycan probe. Results at 5 μg/ml malectin are in Figure 6, Table 1, and Supplemental Table S6. Results with glucose-terminating oligosaccharides using different malectin concentrations are compared in Table 1 and Supplemental Figure S4.

Figure 6.

High selectivity of malectin binding to the Glc2-N-glycan revealed by carbohydrate microarray analyses. In total, 335 oligosaccharide probes (Supplemental Table S6) were printed as duplicate spots. Malectin binding was assayed at 5 μg/ml. Numerical scores are shown of the binding signals (means of duplicate values at 7 fmol/spot, with error bars; the error bars represent half of the difference between the two values). The glucosylated N-glycan sequences are annotated. Inset, expanded region of the microarray highlighting the selective binding of malectin to the Glc2-N-glycan probe in contrast with the broad binding profile of ConA. Abbreviations for the probes: G3N, Glc3Man7(D1)GlcNAc; G2N, Glc2Man7(D1)GlcNAc; G1N, Glc1Man9GlcNAc2; M9N, Man9GlcNAc2; and M7N, Man7(D1)GlcNAc2. These five probes were arrayed at positions 162–165 and at position 168, respectively.

Table 1.

Comparison of the binding signals elicited by glucose disaccharide and glucosylated-high-mannose N-glycan probes in carbohydrate microarrays with malectin at 20, 5, 1 and 0.5 μg/ml

| Oligosaccharide | Sequence | Fluorescent signals at 7 fmol of malectin (μg/ml) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 5 | 1 | 0.5 | ||

| Kojibiose | Glcα1-2Glc | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 |

| Nigerose | Glcα1-3Glc | 8,355 | 555 | <1 | <1 |

| Maltose | Glcα1-4Glc | 6,470 | 507 | <1 | <1 |

| Isomaltose | Glcα1-6Glc | 381 | 42 | <1 | <1 |

| Laminaribiose | Glcβ1-3Glc | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 |

| Cellobiose | Glcβ1-4Glc | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 |

| Gentiobiose | Glcβ1-6Glc | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 |

| Glc3Man7(D1)GN1 |  |

6,836 | 1,077 | <1 | <1 |

| Glc2Man7(D1)GN1 |  |

>>50,000 | 46,454 | 19,207 | 5,929 |

| Glc1Man9GN2 |  |

1,432 | 182 | <1 | <1 |

The strong preference of malectin binding to the Glc2-N-glycan among high-mannose N-glycans is further highlighted in the inset of Figure 6, which is an expanded region of the microarray analysis at 5 μg/ml malectin, and a comparison can be made with the binding profile of concanavalin A (ConA). The binding signals with Glc3- and Glc1-N-glycans with malectin were negligible, only ∼2 and ∼0.4%, respectively, of those for the Glc2-N-glycan (also see Table 1). In contrast, ConA had a broad binding profile, giving strong signals with all of the high-mannose N-glycans, the strongest being with the Man9- and Glc1Man9-N-glycans.

The very weak malectin binding signals with the Glc3- and Glc1-N-glycan probes in the microarrays could represent the presence of trace amounts of Glc2-N-glycan, below limit of mass spectrometric detection; alternatively, the Glc3- and Glc1-N-glycans may weakly cross-react. At lower concentrations of malectin, 1 and 0.5 μg/ml, binding signals detected were exclusively to the Glc2-high-mannose N-glycan probe (Table 1 and Figure S4). The size of the “epitope” that malectin recognizes on this oligosaccharide sequence requires investigation; suffice it to say that the binding signals elicited by this probe were strong despite the absence of the D2 and D3 mannoses (Petrescu et al., 1997) and the innermost N-acetylglucosamine of the Glc2Man9GlcNAc2 glycan.

At 20 μg/ml malectin the binding to the Glc2-N-glycan probe was too high to be accurately quantified (Table 1 and Supplemental Figure S4), but the binding signals with the gluco-oligosaccharide probes were in overall accord with the NMR data.

DISCUSSION

Our structural and ligand–recognition studies culminated in the demonstration that malectin is a novel carbohydrate-binding protein with a unique selectivity for the Glc2-N-glycan ER intermediate among the 268 mammalian-type saccharide sequences examined.

To our knowledge, only two other proteins have thus far been described to recognize the Glcα1-3Glc “epitope.” One is the catalytic site of GII, which cleaves Glc2-N-glycan to produce the Glc1-form (Grinna and Robbins 1980; Kaushal et al., 1990; Alonso et al., 1993). Indeed, GII was shown to bind to a nascent glycoprotein (Deprez et al., 2005), but this association was suggested to be primarily mediated via the high-mannose moiety. This is further supported by studies with chemically synthesized high-mannose N-glycan analogs (Totani et al., 2006).

The other recognition system for the Glc2-high-mannose sequence in the ER operates before the transfer to the nascent protein, at the final steps of the biosynthesis of the lipid-linked core oligosaccharide. Here, the Glc2Man9GlcNAc2 moiety is the acceptor substrate for α1-2 glucosyltransferase, Alg10p, which adds the outermost glucose to form the Glc3Man9GlcNAc2 moiety (Burda and Aebi, 1998).

Consistent with the interaction of malectin with Glc2-N-glycan demonstrated in vitro, we have observed that it resides in the ER. The ER localization of malectin is consistent with a recent proteomic screen of intracellular membrane compartments in rat renal collecting duct cells (see supplement of Barile et al., 2005). In that study, a homologue of malectin (XP_222228 in supplemental of Barile et al., 2005; Q5FVQ4, Supplemental Figure S1 in this study) was detected among 180 proteins that could be coimmunoprecipitated with aquaporin 2. Many of these were ER-resident including key proteins of the early N-glycosylation and N-glycoprotein processing steps such as a subunit of OST, GI, GII α and β chains, calnexin and calreticulin. Because malectin lacks the well-known dilysine-based ER retention sequence (Cosson and Letourneur, 1994), it most likely binds to other molecules containing an ER retention signal.

Our microarray analyses showed that the malectin binding signals with Glc2-N-glycan were substantially higher than with nigerose, which constitutes the capping sequence, Glcα1-3Glc, of the N-glycan. This suggests that the additional mannose residues on the glycan have a strong cooperative effect, although interaction was not detectable with uncapped high-mannose N-glycans. Previous studies have shown that the triglucosyl cap, Glcα1-2Glcα1-3Glc-, has a relatively rigid conformation (Petrescu et al., 1997). The adjacent oligomannose part of the N-glycan seems to have significant conformational freedom (Woods et al., 1998), which could allow additional contacts between the mannose residues and malectin.

From a closer inspection of the NMR structure of the malectin–nigerose complex (Figure 4, C and D), one can deduce the basis for the strong interaction of malectin with the Glc2-N-glycan compared with the Glc1-and Glc3-forms, observed in the microarray analysis. The Glc1-N-glycan contains the Glcα1-3Man sequence at the terminus of the oligosaccharide chain (Figure 4E). The mannose residue has an axial C-2 hydroxyl group (the position is shown by the yellow arrow in Figure 4D) instead of the equatorial C-2 hydroxyl group, as in glucose. This would hinder the stacking interaction of the sugar pyranose ring with Y116 and F117 in malectin. The interaction with the Glc3-N-glycan via the outermost and middle glucose residues is not favored as the terminal sequence Glcα1-2Glc (Figure 4E) corresponds to that of the very low affinity ligand kojibiose. Moreover, interaction with the middle and innermost glucose residues (corresponding to nigerose sequence) would be sterically hindered in the Glc3-N-glycan by the outermost glucose residue (position indicated by orange arrow in Figure 4D), which could not be accommodated in the malectin pocket. In contrast, once the two glucose residues on the Glc2-N-glycan are docked in the malectin binding site, the flexible high-mannose moiety (Petrescu et al., 1997; Woods et al., 1998) would have enough conformational freedom to make contacts with the protein surface and increase the affinity of binding (the position of the mannose joined to the inner glucose is indicated by the magenta arrow in Figure 4D).

The remarkable selectivity for the Glc2-N-glycan points to a role for malectin in the pathway of N-glycosylation. Helenius and coworkers showed that the Glc2-N-glycan polypeptide intermediate associates with an as yet “nonactivated” GII (Deprez et al., 2005). During this time, malectin could interact with the nascent polypeptide chain via the Glc2-N-glycan and could be released only after cleavage of the glucosidic bond by GII. By analogy with calnexin and calreticulin, which are released upon cleavage of the inner glucose residue, malectin may function as a chaperone or may recruit chaperones to protect the nascent polypeptide against aggregation during the sensitive early synthesis period.

Although an evolutionary link could not be detected between bacterial CBMs and malectin, the structural similarity to CBMs and the common hydrophobic sandwiching mode of binding point to another possible function for malectin as follows. CBMs are primarily found in polysaccharide hydrolases where they are combined—often in tandem—with a single catalytic module. Their role is to promote the association of the enzymes with the substrates. We suggest that malectin may recruit GII to the Glc2-N-glycan on the nascent polypeptide. Such an association may account for the report that GII, which is a soluble enzyme, is loosely associated with the luminal side of the ER membrane (Brada and Dubach, 1984). Thus, malectin could be a part of the apparently carefully regulated mechanism of cleavage of the second glucose by GII, contributing to the observed delay in the hydrolysis (Deprez et al., 2005) and preventing the premature formation of the Glc1-N-glycan and entry to the calnexin– calreticulin cycle.

The malectin sequence is well conserved in animals. In plants, malectin-like domains are found with a low sequence homology in a subfamily of RLK, but the malectin-like domains are embedded in a different modular context (Supplemental Figure S2; Shiu and Bleecker, 2003). The external leucine-rich region in RLKs is frequently augmented by inserted domains, some of which are lectins or lectin-like domains; one among them is a homologue of the sweet-tasting protein thaumatin, which mimics carbohydrates (reviewed by Shiu and Bleecker, 2003). The presence of a malectin homology domain in RLKs provides a hint that these domains may also have a carbohydrate binding activity although sequence similarities are restricted to residues determining the fold, whereas the loops constituting the carbohydrate-binding site in malectin diverge in composition and length (Supplemental Figure S1).

N-Glycosylation is found as well in plants, fungi, and protozoa. The glycan processing and quality control steps in the ER are essentially the same as in animals, although the majority of protozoa and some fungi assemble oligosaccharide donors that lack the full complement of glucose residues and/or mannose residues (Banerjee et al., 2007). The presence of a malectin homologous protein only in a subset of the protozoa (some ciliates and apicomplexans), a highly diverged plant homologue and a complete absence of malectin homologues in sequenced fungal proteomes is intriguing. We can only speculate that a protein with no obvious sequence homology fulfills the role of malectin or that a malectin function is not essential in those organisms.

Our studies provide a platform that opens the way to detailed studies of the role of malectin in the genesis, processing and secretion of N-glycosylated proteins, including also the penultimate stage of the biosynthesis of the lipid linked core oligosaccharide.

PDB Accession Numbers

The PDB coordinates have been deposited with the Brookhaven data bank under accession number 2JWP (free protein) and 2K46 (complex with nigerose).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Vladimir Rybin for help with the isothermal titration calorimetry measurement and Bernd Simon for acquiring initial NMR spectra on malectin, Michael Sattler for measurement time on the NMR spectrometers, Wengang Chai for many of the oligosaccharide probes and critical reading of the manuscript, Terry Butters and Mark Wormald for generating and NMR analyses of the Glc2-N-glycan, Yibing Zhang for the mass spectrometric analyses of oligosaccharide probes, Robert Childs and Maria Campanero-Rhodes for the microarrays, and Mark P Stoll for the software for the microarray analyses. The Glycosciences laboratory acknowledges with gratitude colleagues and collaborators over the years with whom our microarray probes were studied. C.M.-G. has been an Emmy-Noether-fellow of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Mu1606/1-5) and A.S.P a fellow of the Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (SFRH/BPD/26515/2006, Portugal). This work was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft to T. P. (Pi 159/8-3), the UK Medical Research Council, and UK Research Councils' Basic Technology grant GR/S79268 (to T. F.).

Abbreviations used:

- CBM

carbohydrate binding module

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- GII

glucosidase II

- RLK

receptor like kinase

- STD

saturation transference difference.

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E08-04-0354) on June 4, 2008.

REFERENCES

- Afelik S., Chen Y., Pieler T. Pancreatic protein disulfide isomerase (XPDIp) is an early marker for the exocrine lineage of the developing pancreas in Xenopus laevis embryos. Gene Expr. Patterns. 2004;4:71–76. doi: 10.1016/s1567-133x(03)00150-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso J. M., Santa-Cecilia A., Calvo P. Effect of bromoconduritol on glucosidase II from rat liver. A new kinetic model for the binding and hydrolysis of the substrate. Eur. J. Biochem. 1993;215:37–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S. F., Madden T. L., Schäffer A. A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W., Lipman D. J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apweiler R., Hermjakob H., Sharon N. On the frequency of protein glycosylation, as deduced from analysis of the SWISS-PROT database. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1473:4–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(99)00165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S., Vishwanath P., Cui J., Kelleher D. J., Gilmore R., Robbins P. W., Samuelson J. The evolution of N-glycan-dependent endoplasmic reticulum quality control factors for glycoprotein folding and degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:11676–11681. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704862104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barile M., Pisitkun T., Yu M. J., Chou C. L., Verbalis M. J., Shen R. F., Knepper M. A. Large scale protein identification in intracellular aquaporin-2 vesicles from renal inner medullary collecting duct. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:1095–1106. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500049-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boraston A. B., Bolam D. N., Gilbert H. J., Davies G. J. Carbohydrate-binding modules: fine-tuning polysaccharide recognition. Biochem. J. 2004;382:769–781. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brada D., Dubach U. C. Isolation of a homogeneous glucosidase II from pig kidney microsomes. Eur. J. Biochem. 1984;141:149–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1984.tb08169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burda P., Aebi M. The ALG10 locus of Saccharomyces cerevisiae encodes the alpha-1,2 glucosyltransferase of the endoplasmic reticulum: the terminal glucose of the lipid-linked oligosaccharide is required for efficient N-linked glycosylation. Glycobiology. 1998;8:455–462. doi: 10.1093/glycob/8.5.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosson P., Letourneur F. Coatomer interaction with di-lysine endoplasmic reticulum retention motifs. Science. 1994;263:1629–1631. doi: 10.1126/science.8128252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornilescu G., Delaglio F., Bax A. Protein backbone angle restraints from searching a database for chemical shift and sequence homology. J. Biomol. NMR. 1999;13:289–302. doi: 10.1023/a:1008392405740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Vuister G. W., Zhu G., Pfeifer J., Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejgaard S., Nicolay J., Taheri M., Thomas D. Y., Bergeron J. J. The ER glycoprotein quality control system. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2004;6:29–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deprez P., Gautschi M., Helenius A. More than one glycan is needed for ER glucosidase II to allow entry of glycoproteins into the calnexin/calreticulin cycle. Mol. Cell. 2005;19:183–195. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosztányi Z., Csizmok V., Tompa P., Simon I. IUPred: Web server for the prediction of intrinsically unstructured regions of proteins based on estimated energy content. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3433–3434. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn R. D., et al. Pfam: clans, web tools and services. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:247–251. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinna L. S., Robbins P. W. Substrate specificities of rat liver microsomal glucosidases which process glycoproteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1980;255:2255–2258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helenius A., Aebi M. Roles of N-linked glycans in the endoplasmic reticulum. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2004;73:1019–1049. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson B. A., Blevins R. A. NMR View: a computer program for the visualization and analysis of NMR data. J. Biomol. NMR. 1994;4:603–614. doi: 10.1007/BF00404272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letunic I., Copley R. R., Pils B., Pinkert S., Schultz J., Bork P. SMART 5, domains in the context of genomes and networks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D257–D260. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linge J. P., O'Donoghue S. I., Nilges M. Automated assignment of ambiguous nuclear Overhauser effects with ARIA. Methods Enzymol. 2001;339:71–90. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(01)39310-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushal G. P., Pastuszak I., Hatanaka K., Elbein A. D. Purification to homogeneity and properties of glucosidase II from mung bean seedlings and suspension-cultured soybean cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:16271–16279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer M., Meyer B. Characterization of ligand binding by saturation transfer difference NMR spectra. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1999;38:1784–1788. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990614)38:12<1784::AID-ANIE1784>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer B., Peters B. NMR spectroscopy techniques for screening and identifying ligand binding to protein receptors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2003;42:864–890. doi: 10.1002/anie.200390233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima T., Hirao T., Yoshida Y., Lee S. J., Chiba T., Iwai K., Yamaguchi Y., Kato K., Tsukihara T., Tanaka K. Structural basis of sugar-recognizing ubiquitin ligase. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004;11:365–370. doi: 10.1038/nsmb732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niehrs C., Steinbeisser H., De Robertis E. M. Mesodermal patterning by a gradient of the vertebrate homeobox gene goosecoid. Science. 1994;263:817–820. doi: 10.1126/science.7905664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palma A. S., et al. Ligands for the beta-glucan receptor, Dectin-1, assigned using “designer” microarrays of oligosaccharide probes (neoglycolipids) generated from glucan polysaccharides. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:5771–5779. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511461200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrescu A. J., Butters T. D., Reinkensmeier G., Petrescu S., Platt F. M., Dwek R. A., Wormald M. R. The solution NMR structure of glucosylated N-glycans involved in the early stages of glycoprotein biosynthesis and folding. EMBO J. 1997;16:4302–4310. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.14.4302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrag J. D., Bergeron J. J., Li Y., Borisova S., Hahn M., Thomas D. Y., Cygler M. The structure of calnexin, an ER chaperone involved in quality control of protein folding. Mol. Cell. 2001;8:633–644. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiu S. H., Bleecker A. B. Expansion of the receptor-like kinase/Pelle gene family and receptor-like proteins in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2003;132:530–543. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.021964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa M. C., Ferrero-Garcia M. A., Parodi A. J. Recognition of the oligosaccharide and protein moieties of glycoproteins by the UDP-Glc:glycoprotein glucosyltransferase. Biochemistry. 1992;31:97–105. doi: 10.1021/bi00116a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Totani K., Ihara Y., Matsuo I., Ito Y. Substrate specificity analysis of endoplasmic reticulum glucosidase II using synthetic high mannose-type glycans. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:31502–31508. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605457200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wishart D. S., Bigam C. G., Yao J., Abildgaard F., Dyson H. J., Oldfield E., Markley J. L., Sykes B. D. 1H, 13C and 15N chemical shift references in biomolecular NMR. J. Biomol. NMR. 1995;6:135–140. doi: 10.1007/BF00211777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods R. J., Pathiaseril A., Wormald M. R., Edge C. J., Dwek R. A. The high degree of internal flexibility observed for an oligomannose oligosaccharide does not alter the overall topology of the molecule. Eur. J. Biochem. 1998;258:372–386. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2580372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.