Abstract

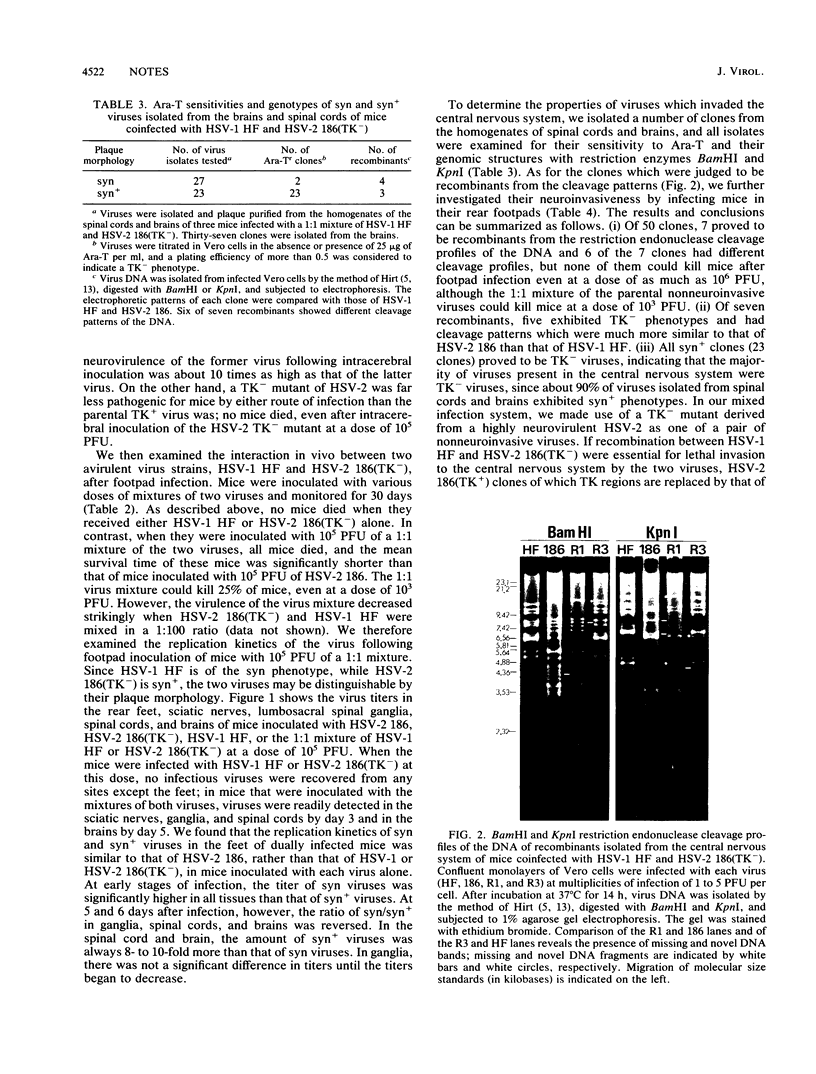

It is well-known that viral thymidine kinase (TK) expression is important for the maximum demonstration of virulence of herpes simplex virus (HSV). In this study, we have investigated interactions of a TK- mutant of virulent HSV type 2 (HSV-2) (syn+) and a nonneuroinvasive HSV-1 (syn) in mice. When the mice were inoculated with each virus alone in their rear footpads, no mice were killed even after infection with high doses of viruses (greater than 10(6) PFU per mouse), whereas 100% of the mice died when inoculated with 10(5) PFU of a 1:1 mixture of HSV-2 TK- mutant and nonneuroinvasive HSV-1. The 1:1 mixture exhibited even more virulence than the parental HSV-2; the mean survival time of coinfected mice was significantly shorter than that of mice inoculated with 10(5) PFU of the virulent HSV-2. We have also examined the genotypes and phenotypes of viruses isolated from the central nervous system of coinfected mice. Of 50 isolates, 7 were judged to be recombinants from their restriction endonuclease cleavage patterns, but all were nonneuroinvasive. In addition, all syn+ viruses (23 clones) tested were found to have TK- phenotypes, indicating that the majority of viruses present in the central nervous system were TK- viruses, since about 90% of viruses detected in spinal cords and brains exhibited syn+ phenotypes. These results strongly suggest that the lethal invasion of the central nervous system by HSV-2 TK- and nonneuroinvasive HSV-1 was the consequence of in vivo complementation between the two viruses.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Chou J., Kern E. R., Whitley R. J., Roizman B. Mapping of herpes simplex virus-1 neurovirulence to gamma 134.5, a gene nonessential for growth in culture. Science. 1990 Nov 30;250(4985):1262–1266. doi: 10.1126/science.2173860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crumpacker C. S., Schnipper L. E., Marlowe S. I., Kowalsky P. N., Hershey B. J., Levin M. J. Resistance to antiviral drugs of herpes simplex virus isolated from a patient treated with acyclovir. N Engl J Med. 1982 Feb 11;306(6):343–346. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198202113060606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day S. P., Lausch R. N., Oakes J. E. Evidence that the gene for herpes simplex virus type 1 DNA polymerase accounts for the capacity of an intertypic recombinant to spread from eye to central nervous system. Virology. 1988 Mar;163(1):166–173. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90243-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dix R. D., McKendall R. R., Baringer J. R. Comparative neurovirulence of herpes simplex virus type 1 strains after peripheral or intracerebral inoculation of BALB/c mice. Infect Immun. 1983 Apr;40(1):103–112. doi: 10.1128/iai.40.1.103-112.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirt B. Selective extraction of polyoma DNA from infected mouse cell cultures. J Mol Biol. 1967 Jun 14;26(2):365–369. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(67)90307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javier R. T., Sedarati F., Stevens J. G. Two avirulent herpes simplex viruses generate lethal recombinants in vivo. Science. 1986 Nov 7;234(4777):746–748. doi: 10.1126/science.3022376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javier R. T., Thompson R. L., Stevens J. G. Genetic and biological analyses of a herpes simplex virus intertypic recombinant reduced specifically for neurovirulence. J Virol. 1987 Jun;61(6):1978–1984. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.6.1978-1984.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larder B. A., Cheng Y. C., Darby G. Characterization of abnormal thymidine kinases induced by drug-resistant strains of herpes simplex virus type 1. J Gen Virol. 1983 Mar;64(Pt 3):523–532. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-64-3-523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez C. Resistance to herpes simplex virus - type 1 (HSV-1). Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1981;92:15–24. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-68069-4_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaren C., Chen M. S., Ghazzouli I., Saral R., Burns W. H. Drug resistance patterns of herpes simplex virus isolates from patients treated with acyclovir. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985 Dec;28(6):740–744. doi: 10.1128/aac.28.6.740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama Y., Rapp F. Repair replication of viral and cellular DNA in herpes simplex virus type 2-infected human embryonic and xeroderma pigmentosum cells. Virology. 1981 Apr 30;110(2):466–475. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(81)90077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama Y., Suzuki S., Yamauchi M., Maeno K., Yoshida S. Characterization of an aphidicolin-resistant mutant of herpes simplex virus type 2 which induces an altered viral DNA polymerase. Virology. 1984 May;135(1):87–96. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(84)90119-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pater M. M., Hyman R. W., Rapp F. Isolation of herpes simplex virus DNA from the "hirt supernatant". Virology. 1976 Dec;75(2):481–483. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(76)90046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards J. T., Kern E. R., Overall J. C., Jr, Glasgow L. A. Differences in neurovirulence among isolates of Herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 in mice using four routes of infection. J Infect Dis. 1981 Nov;144(5):464–471. doi: 10.1093/infdis/144.5.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedarati F., Javier R. T., Stevens J. G. Pathogenesis of a lethal mixed infection in mice with two nonneuroinvasive herpes simplex virus strains. J Virol. 1988 Aug;62(8):3037–3039. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.8.3037-3039.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenser R. B., Edris W. A. Trigeminal ganglion infection by thymidine kinase-negative mutants of herpes simplex virus after in vivo complementation. J Virol. 1987 Jul;61(7):2171–2174. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.7.2171-2174.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenser R. B., Miller R. L., Rapp F. Trigeminal ganglion infection by thymidine kinase-negative mutants of herpes simplex virus. Science. 1979 Aug 31;205(4409):915–917. doi: 10.1126/science.224454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenser R. B., Ressel S., Dunstan M. E. Herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase expression in trigeminal ganglion infection: correlation of enzyme activity with ganglion virus titer and evidence of in vivo complementation. Virology. 1981 Jul 15;112(1):328–341. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(81)90638-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R. L., Cook M. L., Devi-Rao G. B., Wagner E. K., Stevens J. G. Functional and molecular analyses of the avirulent wild-type herpes simplex virus type 1 strain KOS. J Virol. 1986 Apr;58(1):203–211. doi: 10.1128/jvi.58.1.203-211.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshino K., Taniguchi S. Isolation of a clone of herpes simplex virus highly attenuated for newborn mice and hamsters. Jpn J Exp Med. 1969 Jun;39(3):223–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]