Abstract

All but two genes involved in the ergosterol biosynthetic pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae have been cloned, and their corresponding mutants have been described. The remaining genes encode the C-3 sterol dehydrogenase (C-4 decarboxylase) and the 3-keto sterol reductase and in concert with the C-4 sterol methyloxidase (ERG25) catalyze the sequential removal of the two methyl groups at the sterol C-4 position. The protein sequence of the Nocardia sp NAD(P)-dependent cholesterol dehydrogenase responsible for the conversion of cholesterol to its 3-keto derivative shows 30% similarity to a 329-aa Saccharomyces ORF, YGL001c, suggesting a possible role of YGL001c in sterol decarboxylation. The disruption of the YGL001c ORF was made in a diploid strain, and the segregants were plated onto sterol supplemented media under anaerobic growth conditions. Segregants containing the YGL001c disruption were not viable after transfer to fresh, sterol-supplemented media. However, one segregant was able to grow, and genetic analysis indicated that it contained a hem3 mutation. The YGL001c (ERG26) disruption also was viable in a hem 1Δ strain grown in the presence of ergosterol. Introduction of the erg26 mutation into an erg1 (squalene epoxidase) strain also was viable in ergosterol-supplemented media. We demonstrated that erg26 mutants grown on various sterol and heme-supplemented media accumulate nonesterified carboxylic acid sterols such as 4β,14α-dimethyl-4α-carboxy-cholesta-8,24-dien-3β-ol and 4β-methyl-4α-carboxy-cholesta-8,24-dien-3β-ol, the predicted substrates for the C-3 sterol dehydrogenase. Accumulation of these sterol molecules in a heme-competent erg26 strain results in an accumulation of toxic-oxygenated sterol intermediates that prevent growth, even in the presence of exogenously added sterol.

Keywords: fungi/carboxylic acid sterol

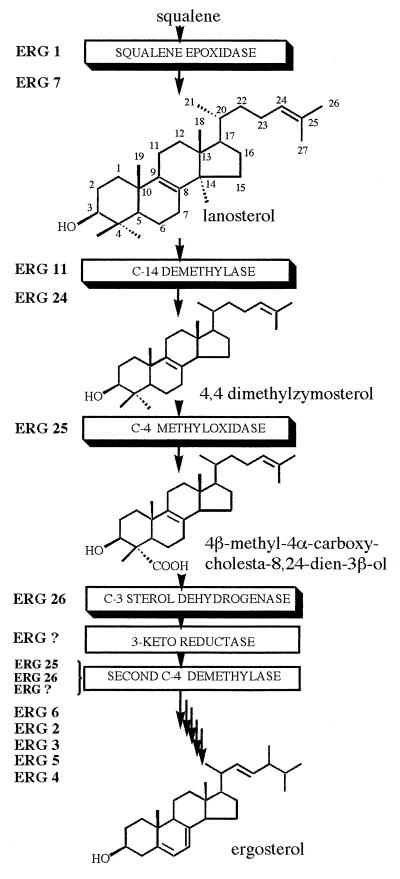

The yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae has been used extensively as a model system for studying sterol biosynthesis (1, 2). Yeast accumulates ergosterol, the sterol equivalent of cholesterol in animals (3) and sitosterol in plants (4), as the end-product sterol. Squalene, the first dedicated sterol precursor in the ergosterol pathway, is converted to the end-product sterol through a sequence of 15 enzymatic reactions (Fig. 1). Only two genes in the ergosterol pathway have neither been cloned nor had their gene products characterized. These two genes encode enzymes involved in C-4 demethylation (Fig. 2). Two consecutive rounds of C-4 demethylation in yeast and animals cells are required to demethylate 4,4-dimethylzymosterol. However, in higher plants, the sequence of C-4 demethylation is interrupted by the removal of the C-14 methyl group as suggested by differences in substrate specificity of the plant demethylating enzymes (5). C-4 methyl or 4,4-dimethyl sterols cannot substitute for end-product sterols in yeast (6, 7).

Figure 1.

S. cerevisiae late ergosterol pathway.

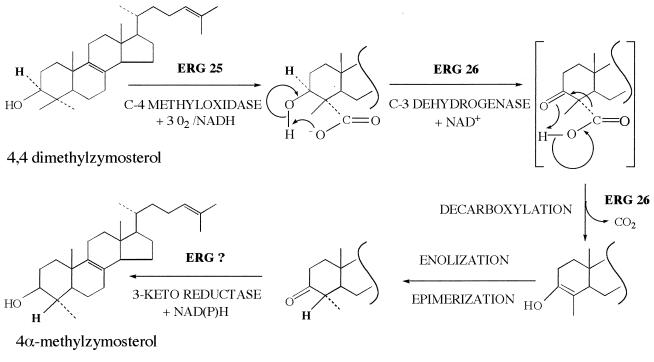

Figure 2.

Proposed mechanism of 4,4-dimethylzymosterol C-4 demethylation. The end product 4α-methylzymosterol is the substrate of a second round of oxidation–decarboxylation-reduction reactions leading to zymosterol.

C-4 demethylation can be separated into three reactions: (i) a C-4 methyloxidase reaction in which the 4α-methyl group is converted to an alcohol, then an aldehyde, and finally to a carboxylic acid; (ii) a C-3 sterol dehydrogenase that removes the 3α-hydrogen (8) resulting in the decarboxylation of the 3-ketocarboxylic acid sterol intermediate (the mechanism for this reaction is illustrated in Fig. 2); and (iii) a 3-keto reductase that converts the 3-keto to the 3β-hydroxy.

The ERG25 gene that encodes the C-4 methyloxidase leading to accumulation of C-4 carboxylic acid sterols was cloned recently from yeast (7, 9) and from a human cDNA library (9). Several groups have demonstrated the accumulation of carboxylic acid sterol intermediates by incubating radiolabeled substrates with microsomes depleted in NAD cofactors (10, 11). An attempt to identify the enzyme involved resulted in the partial purification of the rat sterol decarboxylase from microsomal liver preparations (12). Additionally, a Chinese hamster ovary cell line selected for cholesterol auxotrophy (13) was found to accumulate carboxylic acid sterols (14).

Many of the genes encoding sterol biosynthesis enzymes in yeast are not essential (such as those encoding the enzymes that convert zymosterol to ergosterol; Fig. 1). Genes responsible for the conversion of lanosterol to zymosterol are essential, and loss of function mutations results in an ergosterol requirement for growth. Here we describe the cloning of the C-3 sterol dehydrogenase gene and demonstrate by gene disruption the essential nature of this enzyme. The growth deficiency in erg26 mutants is not merely remedied by an exogenous supply of sterol but additionally requires a second mutation in a gene encoding a heme biosynthetic enzyme. This suggests that accumulation of ERG26 intermediates (carboxylic acid sterols) is toxic to growing heme-competent yeast cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and Plasmids.

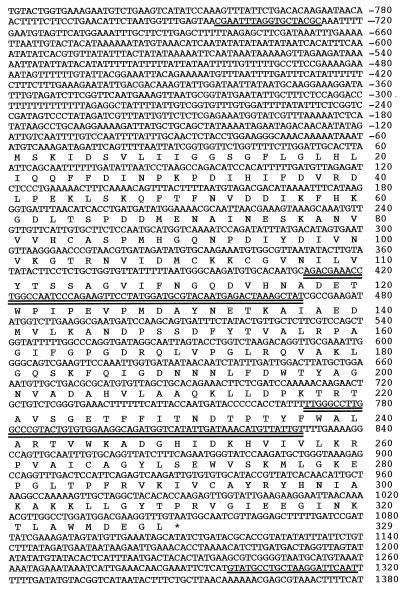

The genotypes of the strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. The ERG26 heterozygote, SDG274, was obtained in a diploid strain, YPH274, by the one-step PCR deletion–disruption (15). The positions of all primers are shown in Fig. 3. Briefly, the primers DB17 (AGACGAAACCTGGCCAATCCCAGAAGTTCCTATGGATGCGTACAATGAGACTAAAGCTATtggcgggtgtcggggctggc) and DB18 (ACAATAACATGTTTATCAATATGACCATCTGCCTTCCACACAGTACGGGCCAAGGCCCAAttgccgatttcggcctattg) were used to generate a 1.3-kb erg26 recombinogenic DNA fragment containing TRP1 as a selectable marker and using the pRS304 (16) vector as template. Lowercase bases correspond to conserved regions bordering the TRP1 marker gene in the pRS304 vector, and uppercase bases refer to the ERG26 DNA gene sequence. The 1.3-kb DNA PCR fragment used to transform YPH274 strain contains a 0.297-kb deletion of the ERG26 coding region (99 aa residues). A third primer, DB19 (GATGTTAGAGATCTCCCTGAA), 0.3 kb upstream of the deletion–substitution, was used in combination with DB18 to verify the disruption. SDG301, containing essentially the same disruption, was made by using the same primers, DB17 and 18, but using pRS303 as the template with HIS3 as the selectable marker. CP3, erg1∷URA3 upc2 (capable of aerobic sterol uptake), was transformed with this DNA fragment and His+ transformants able to grow on ergosterol but not lanosterol supplemented media were obtained.

Table 1.

Genotypes of strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype |

|---|---|

| SDG274 | MATa/α ade2-101/ade2-101 his3-Δ200/his3-Δ200 leu2-Δ1/leu2-Δ1 lys2-801/lys2-801 trp1-Δ1/trp1-Δ1 ura3-52/ura3-52 erg26Δ∷TRP1/ERG26 |

| SDG274–6 | MATa ade2-101 his3-Δ200 leu2-Δ1 lys2-801 trp1-Δ1 ura3-52 erg26Δ∷TRP1 hem3 |

| SDG274–16 | MATα ade2-101 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 hem3 |

| SDGH2 | MATα ade −his7 leu2 ura3-52 trp1∷hisG Δhem1 |

| SDG200 | MATa ade −his −leu2 erg26Δ∷TRP1 trp1∷hisG Δhem1 ura3-52 |

| SDG226 | MATa ade −his −leu2 erg26Δ∷TRP1 trp1∷hisG Δhem1 ura3-52∷pRS 306-ERG26 |

| SDG225 | MATα ade −his7 leu2 ura3-52 trp1∷hisG Δhem1 erg25∷LEU2 |

| SDG301 | MATα erg1∷URA3 upc2 ade2-11 his3 ura3-52 erg26∷HIS3 |

Figure 3.

Nucleotide sequence of the ERG 26 (YLR001c) gene and deduced amino acid sequence. Single- and double-underlined sequences are the amplifying primer sequences used for the cloning of the functional ERG26 gene and for the disrupted-integrating fragment, respectively.

Strain SDG225 was made by transforming SDGH2 with a 2.6-kb DraI DNA fragment containing the erg25∷LEU2 recombinogenic sequence from the plasmid described earlier (7). The resulting Leu+ transformants were grown anaerobically on ergosterol containing medium, then selected by their inability to utilize lanosterol.

For the construction of pRS306-ERG26 and pRS316-ERG26, a 2-kb DNA fragment (Fig. 3) containing the ERG26 ORF flanked by a 0.7-kb promoter and 0.27-kb terminator sequence was amplified by PCR using primers DGNOC I (GCGGATCCCGAATTTAGGTGCTACGC) and DGNOC II (ATTGAATTCTTAGCAGGCATAC) and using genomic DNA from W303 wild type as the template (17). All plasmids were maintained in Escherichia coli DH5α cultured in Luria–Bertani medium supplemented with ampicillin at 50 μg/ml. The PCRs were performed on a Thermocycler apparatus by using the Promega Taq polymerase Kit.

Media and Chemicals.

Yeast sterol auxotrophs were grown aerobically at 30°C on yeast complete medium (YPD, 1% yeast extract/2% bacto-peptone/2% glucose) supplemented with sterol (0.002%, wt/vol) dissolved in ethanol-Tween 80 (1:1, vol/vol). Transformants were grown on complete synthetic-dropout media containing 0.67% yeast nitrogen base, 2% glucose, and amino acid and nitrogenous base supplements at 0.8% (Bio 101).

Ergosta-7,22-dien-3-one and 4,4-dimethyl-cholesta-8,14-dien-3β-ol were gifts from L. Frye (Rennsaulear Polytechnic Institute, Troy, NY). All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma unless specified otherwise. Hemin chloride was dissolved in an ethanol/water (1:1, vol/vol) solution containing 0.01 M sodium hydroxide at a concentration of 130 mg/ml. Diazomethane was generated from N-methyl-nitroso urea (obtained from S. Sen, Indiana University–Purdue University at Indianapolis) in a 40% KOH (wt/vol) solution and extracted with ethyl ether. All solvents were GC grade and were from Fisher.

Complementation and Sequencing.

Yeast transformations were performed as described in the instructions of the Bio 101 kit. A genomic library of S. cerevisiae fragments inserted into the vector YCp50 (18) was used to complement the hem3 mutation. The complementing plasmid was isolated and expressed in DH5α by standard methods (19). DNA sequencing was performed by the Biochemistry Biotechnology Facility at the Indiana University School of Medicine by using the Applied Biosystems model 373 automated DNA sequencer.

Sterol Extraction and Separation.

Total lipids were extracted from freshly grown cells in the presence of washed glass beads according to the method of Bligh and Dyer (20). The sterol fraction was isolated and fractionated from 1 ml of hexane on hexane preequilibrated silica Sep-Pack columns (Waters division of Millipore) as described in Plemenitas et al. (14). Each fraction was dried under nitrogen. Carboxylic acid sterols in the total sterol extract or the Sep-Pak-purified fraction IV were collected by evaporation of solvent, and the residue was dissolved in ethyl ether containing diazomethane. The solution was allowed to stand for 2 h at 0°C and evaporated under nitrogen. Acetylation of the methyl ester carboxylic acid sterols was carried out as described by Miller and Gaylor (21). Sterol derivatives were resolved on 60 TLC F254 precoated Silica Gel plates (E. Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) with methylene chloride as the solvent system (two sequential migrations). Organic compounds were detected after spraying with a 0.1% berberin sulfate ethanolic solution and exposure to short-wavelength UV light. Sterol derivatives were eluted from scraped silica by using methylene chloride.

Sterol Analyses.

GC analysis of sterol extracts was conducted on a HP5890 series II equipped with the Hewlett–Packard chemstation software package. The capillary column (DB-5) was 15 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm film thickness and was programmed from 195°C to 300°C (3 min at 195°C, then an increase at 5.5°C/min until the final temperature of 300°C was reached, then held for 10 min). The linear velocity was 30 cm/sec using nitrogen as the carrier gas, and all injections were run in the splitless mode. GC/MS analysis of sterols was carried out on two separate instruments. In the first analysis, GC separations were obtained by using a Varian 3400 gas chromatograph interfaced to a Finnigan MAT SSQ 7000 mass spectrometer. The GC separations were done on a fused silica column, DB-5 (15 m × 0.32 mm × 0.25 μm film thickness) programmed from 50°C to 250°C at 20°C/min after a 1-min hold at 50°C. The oven temperature then was held at 250°C for 10 min before programming the temperature to 300°C at 20°C/min. Helium was the carrier gas with a linear velocity of 50 cm/sec in the splitless mode. The mass spectrometer was operated in the electron impact ionization mode at an electron energy of 70 eV, an ion source temperature of 150°C, and scanning from 40 to 650 atomic mass units. In the second analysis, GC separations were obtained by using a Shimadzu GC/MS QP-5000 in which a 30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm Restak XTI-5 column was programmed from 195°C to 300°C at 20°C/min after a 3-min hold at 195°C and a 30-min hold at the final temperature. Helium was the carrier gas with a flow of 1.9 ml/min run in the splitless mode. The mass spectrometer was in the electron impact ionization mode at an electron energy of 70 eV, an ion source temperature of 260°C, and scanning from 50 to 700 atomic mass units.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Identification of a C-3 Sterol Dehydrogenase.

Demethylation of 4,4-dimethylzymosterol, in cholesterol or ergosterol biosynthesis, involves oxidation of the 4α-methyl group to a carboxylic acid, followed by dehydrogenation of the C-3α- hydrogen leading to a 3-keto sterol (sterol dehydrogenase) and finally by decarboxylation at the C-4 position (Fig. 2). A 3-ketoreductase is then required to reduce the 3-keto to a 3-hydroxy sterol. A cholesterol dehydrogenase isolated from Nocardia is a NAD(P)-dependent cholesterol dehydrogenase, which oxidizes the 3-hydroxyl group to a 3-ketone (22). We surmised that this reaction is exactly what would be required for the removal of C-4 carboxylic acid during sterol synthesis. The deduced amino acid sequence of the Nocardia enzyme indicated 30% sequence similarity to an uncharacterized yeast ORF, YGL001c. The YGL001c (ERG26) nucleotide sequence and the deduced 329-aa sequence are shown in Fig. 3.

Disruption of the YGL001c.

The diploid strain, YPH274, was transformed with a 1.3-kb DNA fragment containing the TRP1 gene flanked by 0.06 kb of erg26 recombinogenic ends. Only 1 of 15 recombinant colonies contained the correct erg26 disruption, as determined by PCR analyses. This transformant (SDG274) was sporulated and segregants were plated onto ergosterol supplemented media under anaerobic culture conditions. Surprisingly, Trp+ segregants were not viable upon being transferred to fresh ergosterol-supplemented media. However, one segregant derived from SDG274, SDG 274–6, was able to grow both aerobically and anaerobically on ergosterol media, suggesting that disruption of YGL001c gives rise to sterol auxotrophy and that a second mutation may have arisen in this strain. GC analyses of this strain indicated that only lanosterol accumulated in addition to the ergosterol that was added as a growth supplement. SDG274–6 then was crossed to the wild-type strain to identify the uncharacterized mutation. From a total of four four-spored tetrads, four types of segregants were observed: Trp+ segregants that could not grow when transferred to fresh ergosterol medium, Trp+ segregants that could grow when transferred, Trp− segregants that were wild type, and Trp− segregants that grew only on ergosterol-supplemented medium or heme-supplemented medium, indicating that a heme mutation was responsible for viability of the erg26 strain. SDG274–6 transformed with the pRS316-ERG26 complementing plasmid required either ergosterol-Tween 80 or heme supplementation for growth on YPD medium and subsequently was shown to be a hem3 erg26 double mutant (see below). Mutations in heme biosynthesis often accompany lesions in ergosterol biosynthesis. Gollub et al. (23) isolated a erg7 hem3 double mutant (GL7) and failed to observe erg7 segregants from a cross of GL7 to wild type. Gachotte et al. (24) demonstrated that erg11 in conjunction with a leaky heme mutation could suppress the lethality of erg25. GC analyses of the heme requiring segregants growing on ergosterol-Tween 80-supplemented media gave sterol profiles consistent with a heme lesion, i.e., accumulation of C-14 sterols (25).

Cloning the Heme Mutation.

A segregant from erg26 hem3 crossed to wild type containing the heme mutation (SDG274–16) was transformed by using a YCp50-based Saccharomyces genomic library (18). A heme-complementing plasmid containing a 10.5-kb genomic DNA insert was subcloned into pRS316 as individual HindIII fragments (5-, 2.5-, 1.1-, 1-, and 0.9-kb). The 1-kb DNA subclone was sequenced and shown to contain a partial HEM3 gene. A 1.6-kb EcoRI fragment containing the entire HEM3 gene (which encodes porphobilinogen deaminase) was subcloned into pRS316, and it complemented SDG274–16.

Construction of hem1 erg26 and erg1 erg26 Double Mutants.

To determine whether other heme mutations would allow growth of erg26 strains, SDG274–6 was crossed to SDGH2 (Δhem1, δ-aminolevulinic synthase) to replace the hem3 mutation with the nonrevertible Δhem1. The hem1 erg26 strain was viable when grown on medium supplemented with ergosterol-Tween 80 but not viable when it was grown on medium supplemented with ergosterol-Tween 80 plus δ-aminolevulinic acid (100 μg/ml). This again revealed that absence of heme is essential to the viability of erg26 strains. Growth in the absence of heme suggested that perhaps a toxic lanosterol derivative was forming in erg26 strains and that the heme lesion slowed the conversion of lanosterol to downstream intermediates. We surmised that, since it is unable to accumulate lanosterol, an erg1 erg26 strain would not be able to synthesize these toxic intermediates because the erg1 mutation is epistatic to erg26. ERG26 was disrupted in an erg1-containing strain, CP3 (7), to generate the erg26 erg1 heme-competent double mutant that grew on ergosterol-supplemented medium.

Sterol Growth Responses of Ergosterol and Heme Mutant Strains.

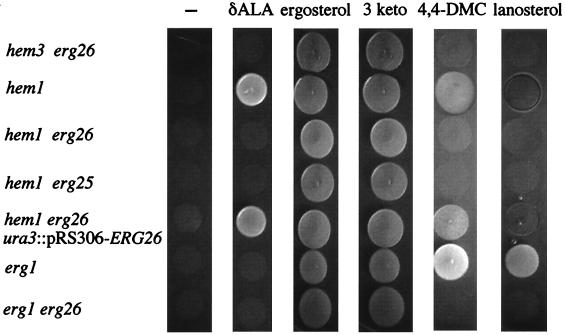

Fig. 4 shows growth responses of various heme- and ergosterol-deficient strains. SDG274–6 (hem3 erg26) grows on ergosterol and a 3-keto ergosterol derivative, ergosta-7,22-dien-3-one (3 keto), but not on lanosterol or 4,4-dimethyl-cholesta-8,14-dien-3β-ol (4,4-DMC)-supplemented YPD media. The latter two sterols are C-4 methylated sterols, indicating that the erg26 lesion involves C-4 demethylation. SDGH2 (hem1), as expected, grows on 4,4-DMC, since hem1 strains are able to demethylate C-4 sterols. The hem3 erg26 strain behaves identically to hem1 erg26 and hem1 erg25 and also is unable to demethylate C-4 sterols. SDG226 is otherwise identical to hem1 erg26 but contains wild-type ERG26 integrated at the ura3 locus and is able to grow on 4,4-DMC. Whereas erg1 grows on 4,4-DMC and lanosterol, erg1 erg26 does not, reflecting the inability to further metabolize C-4 methylated sterols. These results indicate that erg26 strain is incapable of demethylating C-4 methyl sterols.

Figure 4.

Growth responses on YPD media supplemented with δ-aminolevulinic acid (δ-ALA) or various sterols. 3 keto, ergosta-7,22-dien-3-one; 4,4-DMC, 4,4-dimethyl-cholesta-8,14-dien-3β-ol. All strains were pregrown on ergosterol supplemented media.

Biochemical Characterization of the erg26 Mutant.

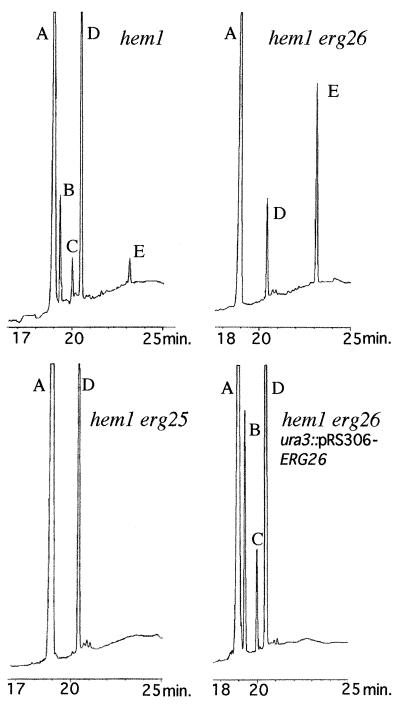

We demonstrated previously that the erg25 mutant also was unable to utilize C-4 methyl sterols. To complete C-4 demethylation, a C-3 sterol dehydrogenase and a 3-ketoreductase also are required (Fig. 2). Since the hem1 erg26 strain was not able to grow on media supplemented with C-4 methylsterols (4,4-dimethyl-cholesta-8,14-dien-3β-ol and lanosterol) but was able to utilize ergosta-7,22-dien-3-one (Fig. 4), we surmised that the lesion in erg26 resulted from an inability to metabolize C-4 carboxylic acid sterols (Fig. 2). To isolate and identify sterol intermediates, including carboxylic acid sterols accumulated in hem1 erg26, the total sterol extract was separated into four fractions on Sep-Pak columns. Fraction IV containing acidic sterols was treated with diazomethane to stabilize and decrease the polarity of these compounds. This fraction was purified by TLC and analyzed by GC/MS analysis. The GC/MS fragmentation data indicated the presence of a carboxylic group at the C-4 position and a nonmethylated but unsaturated side chain. These intermediates are very similar to compounds isolated in vitro by Miller and Gaylor (10, 21) and Plemenitas et al. (14) from an animal cell line cholesterol auxotroph. The position of unsaturation in the B ring cannot be assessed by the fragmentation pattern but is probably at the C-8 position since Δ7-sterols have not been detected as ergosterol intermediates in strains blocked in the removal of the C-14 (25, 26) or C-4 methyl groups (7). These intermediates were found in the free sterol fraction but were not found in Sep-Pak fraction I, which contains steryl-esters. In the presence of δ-aminolevulinic acid, hem1 erg26 strains accumulate two carboxylic acid sterols (M+ = 470 and M+ = 456 methyl esters) differing by an extra methyl at the C-14 position. The conversion of the 3β-hydroxy function into a 3-keto derivative by the ERG26 gene product creates a β-ketocarboxylic acid sterol intermediate. Whether decarboxylase and epimerase activities occur on the same or different proteins cannot be determined until the ERG26 gene product has been isolated and its enzymatic activity has been reconstituted in vitro. Lastly, sterol profiles of a hem1, hem1 erg26, hem1 erg26 ura3∷pRS306-ERG26, and hem1 erg25 demonstrated that carboxylic acid sterols accumulated only in erg26 strains (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

GC analyses of diazomethane-treated sterols extracted from various sterol mutants. The strains were grown in YPD complete media supplemented with ergosterol. Sterols were identified by GC/MS analysis. Peak A, ergosterol; peak B, C-14 methylfecosterol [14α-methyl-ergosta-8,24(28)-dien-3β-ol]; peak C, obtusifoliol [4α,14α-dimethyl-ergosta-8,24(28)-dien-3β-ol]; peak D, lanosterol; peak E, methyl ester derivative of 4β,14α-dimethyl-4α-carboxy-cholesta-8,24-dien-3β-ol.

Accumulation of Carboxylic Acid Sterols in erg26.

To gain insight into the accumulation of carboxylic acid sterols, isogenic strains hem1 erg26 ura3 (SDG200) and hem1 erg26 ura3∷pRS306-ERG26 (SDG226), which differed only in that the latter has a wild-type ERG26 copy integrated at the ura3 locus, were grown on YPD medium containing ergosterol. Table 2 demonstrates that in the absence of δ-aminolevulinic acid, both strains give approximately the same growth yield and contain the same level of cellular ergosterol derived from the growth medium. In hem1 erg26 (SDG200) grown under these conditions, the percentage of carboxylic acid sterols is 27%. No carboxylic acid sterol accumulates in SDG226 that has ERG26 integrated at the ura3 locus. However, as δ-aminolevulinic acid is added to this same media there is a sharp decrease in the growth yield of SDG200. This is partly because of an inability to accumulate ergosterol from the growth medium as these cells are becoming heme-competent, and also partly because of a marked increase in carboxylic acid sterols in this strain (52%). The increase in carboxylic acid sterols in SDG200 is accompanied by a sharp increase in the 4-methyl carboxylic acid sterol (M+ = 456 methyl ester, see Table 2) that accumulates only in heme-competent cells after C-14 demethylation (Fig. 1). It is tempting to speculate that accumulation of carboxylic acid sterols is toxic to cells because (i) as oxygenated intermediates, they are poor candidates for insertion into plasma and internal membranes and (ii) they may not be good substrates for esterification and, therefore, cannot be stored in microlipid droplets along with excess sterol intermediates and excess ergosterol. However, it is also possible that the C-14 demethylated carboxylic acid sterol, which accumulates only in heme-competent cells, may be even more toxic than the C-14 methylated carboxylic acid sterols.

Table 2.

Carboxylic acid sterols accumulating in erg26 hem1 and ERG26 hem1 mutants grown in supplemented YPD complete media containing various amounts of δ-aminolevulinic acid

| Genotype | Sterol compound | δ-aminolevulinic acid*

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 100 | ||

| hem1 erg26 | Ergosterol | 1,277† | 1,377 |

| Lanosterol | 377 | 1,031 | |

| 14-Methylfecosterol, obtusifoliol | 0 | 0 | |

| 4,14-Dimethyl-4-carboxy-sterol | 607 | 389 | |

| 4-Methyl-4-carboxy-sterol | 0 | 2,241 | |

| Cell dry weight, mg | 190.5 | 33.7 | |

| hem1 ERG26‡ | Ergosterol | 1,489 | 1,634 |

| Lanosterol | 349 | 10 | |

| 14-Methylfecosterol, obtusifoliol | 98 | 0 | |

| 4,14-Dimethyl-4-carboxy-sterol | Trace | 0 | |

| 4-Methyl-4-carboxy-sterol | 0 | 0 | |

| Cell dry weight, mg | 218 | 242 | |

Grown 20 h in YPD media supplemented with ergosterol (10 μg/ml) and δ-aminolevulinic acid in μg/ml.

Expressed in μg/g of dry weight.

hem1 erg26 with pRS306-ERG26 integrated at the ura3 locus.

Additionally, the requirement for the heme mutation may also reflect the fact that endogenously synthesized carboxylic acid sterols must compete with exogenous ergosterol in cell membranes. The heme mutation may be required to ensure that exogenous ergosterol enters the cell quickly and in sufficient quantities. The phenomenon in which sterol uptake occurs anaerobically (little or no heme synthesized) or in heme-deficient strains has been called aerobic sterol exclusion (27) and is not understood. We hypothesize that semianaerobic conditions (anaerobic jars using GasPak plus; BBL) are not equivalent to heme-deficient strains with regard to sterol uptake. Clearly, this is not the case for erg11, erg24, or erg25 strains that take up ergosterol anaerobically without the requirement of an auxiliary heme mutation. Therefore, the heme mutation may play a dual role in that it is required to facilitate sterol uptake and directly limit the production of carboxylic acid sterols.

The ERG26 gene is essential for sterol synthesis in plants, animals, and fungi. We noted three amino acid sequences from Schizosaccharomyces pombe, human, and Arabidopsis (GenBank database) with 35% or greater identity to the Saccharomyces ERG26 gene. The percentage identity and accession numbers for these three sequences are 50% (AL022019), 38% (AF027974), and 35% (AC004484), respectively. It would not be surprising, therefore, that these proteins are the C-3 sterol dehydrogenases in these organisms.

With the completion of this study, two of the genes encoding C-4 demethylase enzymes now have been characterized. It is possible that identification of the third gene, the 3-keto reductase, will complete the characterization of the ergosterol biosynthetic pathway at the genetic level. However, while this yeast pathway is nearing completion at the DNA level, little is known regarding the biochemistry of the individual enzymes beyond substrate specificity. Clearly, sterol biosynthesis occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum but the organization of the enzymes into a multienzyme complex has yet to be demonstrated. For example, the Erg26 protein (like the Erg6 and Erg7 proteins) does not contain a predicted transmembrane domain, suggesting a peripheral association with the endoplasmic reticulum. The biochemical characterization and enzymatic interactions of a possible large, multienzyme complex surely will be interesting.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Amanda Schleper for technical assistance and the Purdue University GC/MS facility for preliminary sterol analyses. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant 1R01 AI38598 to M.B.

ABBREVIATIONS

- YPD

yeast extract/peptone/glucose

- ergosterol

ergosta-5,7,22-trien-3β-ol

- 4

4-dimethylzymosterol, 4,4-dimethyl-cholesta-8,24-dien-3β-ol

- 14-methylfecosterol

14-methyl-ergosta-8,24(28)-dien-3β-ol

- lanosterol

4,4,14-trimethyl-cholesta-8,24-dien-3β-ol

- obtusifoliol

4,14-dimethyl-ergosta-8,24(28)-dien-3β-ol

References

- 1.Bach T J, Benveniste P. Prog Lipid Res. 1997;36:197–226. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(97)00009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lees N D, Bard M, Kirsch D R. In: Biochemistry and Function of Sterols. Parish E J N, Nes D W, editors. Boca Raton, FL: CRC; 1997. pp. 85–99. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trazskos J M, Gaylor J L. In: The Enzymes of Biological Membranes. Martinosi A N, editor. Vol. 2. New York: Plenum; 1985. pp. 177–204. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benveniste P. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1986;37:275–308. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taton M, Salmon F, Pascal S, Rahier A. Plant Physiol Biochem. 1994;32:751–760. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuchta T, Bartkova K, Kubinec R. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;189:85–91. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)91529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bard M, Bruner D A, Pierson C A, Lees N D, Biermann B, Frye L, Koegel C, Barbuch R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:186–190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bloxham D P, Wilton D C, Akhtar M. Biochem J. 1971;125:625–634. doi: 10.1042/bj1250625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li L, Kaplan J. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:16927–16933. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.28.16927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller W L, Gaylor J L. J Biol Chem. 1970;245:5375–5381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pascal S, Taton M, Rahier A. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:11639–11654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rahimtula A D, Gaylor J L. J Biol Chem. 1972;247:9–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berry D J, Chang T Y. Biochemistry. 1982;21:573–580. doi: 10.1021/bi00532a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Plemenitas A, Havel C M, Watson J A. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:17012–17017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baudin A, Ozier-Kalogeropoulos O, Denouel A, Lacroute F, Cullin C. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:3329–3330. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.14.3329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sikorski R S, Hieter P. Genetics. 1989;122:19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ausubel F, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K. Short Protocols in Molecular Biology. New York: Wiley; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rose M D, Novick P, Thomas J H, Botstein D, Fink G R. Gene. 1987;60:237–243. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90232-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular Cloning. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bligh E G, Dyer W J. Can J Biochem. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller W L, Gaylor J L. J Biol Chem. 1970;245:5369–5374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horinouchi S, Ishizuka H, Beppu T. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:1386–1393. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.5.1386-1393.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gollub E G, Kuo-Peing L, Dayan J, Adlersberg M, Sprinson D B. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:2846–2854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gachotte D, Pierson C A, Lees N D, Barbuch R, Koegel C, Bard M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:11173–11178. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trocha P J, Jasne S J, Sprinson D B. Biochemistry. 1977;16:4721–4726. doi: 10.1021/bi00640a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalb V K, Woods C W, Turi T G, Dey C R, Sutter T R, Loper J C. DNA. 1987;6:529–537. doi: 10.1089/dna.1987.6.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shinabarger D L, Keesler G A, Parks L W. Steroids. 1989;53:607–623. doi: 10.1016/0039-128x(89)90035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]