Abstract

RNA editing in African trypanosomes is characterized by a uridylate-specific insertion and/or deletion reaction that generates functional mitochondrial transcripts. The process is catalyzed by a multi-enzyme complex, the editosome, which consists of approximately 20 proteins. While for some of the polypeptides a contribution to the editing reaction can be deduced from their domain structure, the involvement of other proteins remains elusive. TbMP42, is a component of the editosome that is characterized by two C2H2-type zinc-finger domains and a putative oligosaccharide/oligonucleotide-binding fold. Recombinant TbMP42 has been shown to possess endo/exoribonuclease activity in vitro; however, the protein lacks canonical nuclease motifs. Using a set of synthetic gRNA/pre-mRNA substrate RNAs, we demonstrate that TbMP42 acts as a topology-dependent ribonuclease that is sensitive to base stacking. We further show that the chelation of Zn2+ cations is inhibitory to the enzyme activity and that the chemical modification of amino acids known to coordinate Zn2+ inactivates rTbMP42. Together, the data are suggestive of a Zn2+-dependent metal ion catalysis mechanism for the ribonucleolytic activity of rTbMP42.

INTRODUCTION

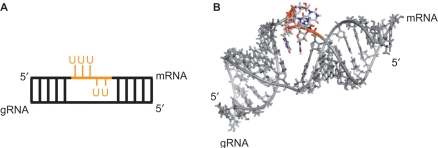

The insertion/deletion-type RNA editing in kinetoplast protozoa such as African trypanosomes is a unique posttranscriptional modification reaction. The process is characterized by the site-specific insertion and/or deletion of exclusively U nucleotides into otherwise incomplete mitochondrial pre-messenger RNA (pre-mRNA). RNA editing relies on small, noncoding RNAs, termed guide RNAs (gRNAs), which act as templates in the process. The reaction is catalyzed by a high molecular mass enzyme complex, the editosome, which represents a reaction platform for the individual steps of the processing cycle (1–3). An editing cycle starts with the annealing of a pre-edited mRNA to a cognate gRNA molecule. The hybridization is facilitated by matchmaking-type RNA/RNA annealing factors (4–8) that generate a short intermolecular gRNA/pre-mRNA duplex located proximal to an editing site. The pre-mRNA is then endoribonucleolytically cleaved at the first unpaired nucleotide (9–11) and in insertion editing, a 3′ terminal uridylyl transferase (TUTase) adds U nucleotides to the 3′ end of the 5′ pre-mRNA cleavage fragment (12,13). In deletion editing, Us are exonucleolytically (exoUase) removed from the 5′ cleavage fragment with a 3′-5′ directionality (14,15). Lastly, the two pre-mRNA fragments are re-sealed by an RNA ligase activity (16–18).

Over the past years our knowledge of the protein inventory of the editosome has significantly increased. Depending on the enrichment protocol, active RNA editing complexes contain as little as 7 (19), 13 (20) or up to 20 polypeptides (21). Protein candidates for every step of the minimal reaction cycle have been identified, thereby confirming the general features of the above-described enzyme-driven reaction mechanism. However, many of the enzyme activities are present in pairs or in even higher numbers of protein candidates (22). This redundancy is not understood but has been used to suggest that insertion and deletion editing are executed by separate subcomplexes (23). Within this context, several candidate proteins have been suggested to account for the different ribonucleolytic activities of the editosome. TbMP90, TbMP67, TbMP61, TbMP46 and TbMP44 all contain RNase III consensus motives and TbMP100 and TbMP99 possess endo–exo-phosphatase (EEP) domains (24). TbMP90 seems to play a role in deletion editing (25), while TbMP61 was suggested to contribute to insertion editing as demonstrated by gene knockout studies (26). However, none of the candidate proteins has been shown to execute nuclease activity in vitro. TbMP100 and TbMP99 were shown to possess a U nucleotide-specific exoribonuclease activity in vitro, but gene knockout or RNA interference (RNAi)-mediated knockdown studies remained elusive (27,28).

TbMP42 is a component of the editosome that does not contain any typical nuclease motif (29). The protein has two C2H2-Zn-finger domains at its N-terminus and a putative oligonucleotide/oligosaccharide binding (OB)-fold at its C-terminus. Recombinant (r) TbMP42 has been shown to execute both, endo- and exo-ribonuclease activity in vitro. Gene ablation of TbMP42 using RNAi is lethal to the parasite and mitochondrial extracts lacking the protein have reduced endo/exoribonuclease and diminished RNA editing activity. Adding back recombinant TbMP42 can restore these activities (30). Here, we provide experimental evidence that rTbMP42 acts as a structure-sensitive ribonuclease. Chelation of Zn2+ cations inhibits the ribonucleolytic activities of the protein as does the chemical modification of amino acids known to coordinate Zn2+. The results are suggestive of a Zn2+-dependent, metal ion catalysis mechanism for TbMP42.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

rTbMP42 preparation

Recombinant TbMP42 was prepared at denaturing conditions as described (30). Protein preparations were dialyzed against 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 30 mM KCl, 10 mM Mg(OAc)2, 5 mM CaCl2, 0.1 mM ZnSO4 and 2M urea, except for modification reactions when urea was omitted. The Leishmania orthologue of TbMP42 (LC-7b) was purified as a C-terminal maltose-binding peptide (MBP) fusion protein expressed in Escherichia coli DH5α containing plasmid pMalc2x_Lt7b. Cells were lysed in 20 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.4, 0.2 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA and 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol using repetitive freeze/thaw cycles and sonication. The lysate was incubated with 0.5 ml amylose resin for 2 h at 4°C. The resin was washed with 12 ml buffer and the recombinant protein was eluted with the same buffer containing 10 mM maltose. Eluted LC-7b/MBP was dialyzed to assay conditions.

Protein modification

To modify aspartic acid and glutamic acid residues, renatured rTbMP42 was incubated for 1 h at 27°C in the above described buffer adjusted to pH 6.2. 1-Ethyl-(3,3-dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide (EDC) and glycine ethyl-ester were added up to a 275-fold molar excess. Histidine residues were derivatized in the same buffer at pH 7.5 with a 50-fold molar excess of diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC) for 1 h at 27°C. Arginines were modified with phenylglyoxal in a 50-fold molar excess and cysteines with N-ethylmaleimide in a 80-fold molar excess. Following incubation, 50 mM solutions of the different amino acids were added to stop the reactions. Finally, modified rTbMP42 was dialyzed to assay conditions.

Endo/exoribonuclease assay

RNA and DNA substrates were synthesized using solid phase phosphoramidite chemistry. The following sequences were synthesized: pre-mRNAs—U5-ds13: GGGAAAGUUGUGAUUUUUGCGAGUUAUAGCC, U5-ds10: GGGAAUGUGA-UUUUUGCGAGUAGCC, U3-ds10: GGGAAUGUGAUUUGCGAGUAGCC, U1-ds10: GGGAAUGUGAUGCGAGUAGCC. U5-ds7: GGGGUGAUUUUUGCGA-GCC, T5-ds10: d(GGGAATGTGATTTTTGCGAGTAGCC), dU5-ds10: GGG-AAUGUGAdUdUdUdUdUGCGAGUAGCC. gRNA sequences—gU5-ds13: GGC-UAUAACUCGCUCACAACUUUCC, g(U5,dU5,U3) and gU1-ds10: GGCUACU-CGCUCACAUUCCC, gU5-ds7: GGCUCGCUCACCCC, gT5-ds10: GGCTA-CTCGCTCACATTCCC. Oligonucleotide concentrations were determined by UV absorbency measurements at 260 nm using extinction coefficients (ε260, l mol−1 cm−1) calculated from the sum of the nucleotide absorptivity as affected by adjacent bases (31). RNAs were radioactively labeled, purified and annealed as in ref. (30). Annealed RNAs (50 fmol, specific activity 0.3 μCi/pmol) were incubated with 50–80 pmol of rTbMP42 or 10 pmoles of rLC-7b/MBP in 30 μl 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 30 mM KCl, 10 mM Mg(OAc)2, 5 mM CaCl2, 0.1 mM ZnSO4, 0.2 mM DTT, 0.5 mM ATP, 0.04 mM UTP and 1 M urea for up to 3 h at 27°C. Competition binding assays were performed for 2 h at 27°C in a 30 μl reaction volume. Samples contained 50 pmol refolded rTbMP42, 0.5 pmoles radiolabeled U5-ds10 and increasing amounts (30 fmol to 7 μmol) of nonradioactive U5-ds10 or U1-ds10. Reaction products were analyzed as above.

Structure probing and RNA modeling

Radioactively labeled U5-ds10 was subjected to RNase A (0.03 ng/µl) or RNase P (2 mU/µl) treatment for up to 30 min. Reaction products were separated in denaturing polyacrylamide gels (18% w/v, 8M urea) and analyzed by phosphorimaging. RNA modeling was performed using JUMNA—junction minimization of nucleic acids (32). Images were rendered using PyMOL (http://www.pymol.org).

RESULTS

The size of the pre-mRNA ‘U-loop’ is a determinant for cleavage activity

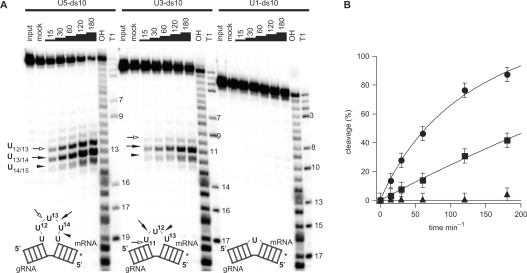

U insertion and deletion RNA editing can be reproduced in vitro using short, synthetic RNA molecules that mimic the essential structural features of gRNA/pre-mRNA hybrid molecules (10,33,34). rTbMP42 has been shown to bind and cleave synthetic gRNA/pre-mRNA pairs (30) and as an initial step to characterize the ribonucleolytic mechanism of TbMP42, we aimed at determining the substrate recognition specificity of the protein. For that, we generated a set of synthetic gRNA/pre-mRNA hybrid molecules. The RNAs differ in the number of single stranded (ss) Us (1U, 3Us, 5Us) within the editing domain of the pre-mRNA sequence, while the two flanking double-stranded (ds) domains were kept constant at 10 bp. The RNAs were termed U5-ds10; U3-ds10 and U1-ds10 (Figure 1A). Radioactive preparations of the three molecules (radiolabeled at the 3′ end of the pre-mRNA) were incubated with rTbMP42 and the generated hydrolysis fragments were separated by gel electrophoresis. Figure 1A shows a representative time course experiment. After an incubation period of 15 min endonucleolytic cleavage of U5-ds10 and U3-ds10 can be detected. U1-ds10 RNA was not cleaved even after 3 h of incubation. Of the six internucleotide bonds that connect the U5 sequence in U5-ds10 only three are cleaved: U12/U13, U13/U14 and U14/U15. The same holds true for the four phosphodiester bonds in the U3 sequence of U3-ds10. Cleavage only occurred at U10/U11, U11/U12 and U12/U13. All other phosphodiester linkages were never cleaved even after prolonged incubation times. Cleavage at the described nucleotides increased over time in the order U13/U14>U12/U13>U14/U15 in U5-ds10 and in the order U11/U12>U10/U11>U12/U13 in U3-ds10. Figure 1B shows a plot of the percentage of cleavage over time for all three gRNA/pre-mRNA pairs. Cleavage of U5-ds10 follows a saturation function and the reaction is >90% complete after 3 h. Half-maximal cleavage is achieved after ∼60 min. For U3-ds10, a value of 40% is reached after 3 h.

Figure 1.

Loop size is critical for cleavage efficiency. (A) Reaction kinetic of the rTbMP42-mediated cleavage of gRNA/pre-mRNA hybrids U5-ds10, U3-ds10 and U1-ds10. Cartoons of the three RNAs are shown below the autoradiograms: top strand—pre-mRNA; bottom strand—gRNA. Radiolabeled RNA preparations (at the 3′ end of the pre-mRNA as shown by the *) were incubated with rTbMP42 for up to 180 min and reaction products were resolved electrophoretically. Cleavage positions and efficiencies are marked by arrows: filled arrow—most efficient cleavage site; open arrow—medium efficiency cleavage site; arrow head—least efficient cleavage site). ‘Input’ represents an untreated RNA sample and ‘mock’ a sample that was incubated in the absence of rTbMP42. ‘T1’ represents an RNase T1 hydrolysis ladder and ‘OH’ an alkaline hydrolysis ladder. (B) Plot of the percentage of cleavage over time (circles: U5-ds10, squares: U3-ds10, triangles: U1-ds10). Data points are fitted to the Langmuir isotherm f(x) = (a*x)/(1 + b*x). Error bars represent SDs derived from at least five individual experiments.

Lastly, we determined that the three hybrid RNAs bind to rTbMP42 with similar affinity. This was done by binding competition experiments and confirmed that the observed cleavage preference of rTbMP42 for the three gRNA/pre-mRNA hybrids is a reflection of the structural characteristics of the RNAs and not a consequence of different binding affinities (data not shown).

The helix length of the gRNA/pre-mRNA hybrid affects the cleavage rate

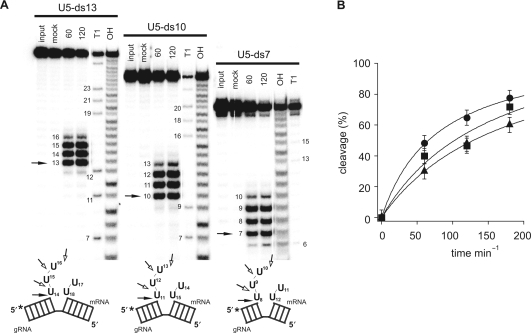

Based on the described results, we generated a second, complementary set of gRNA/pre-mRNA hybrid molecules. The three RNAs are characterized by five ss U nucleotides within the pre-mRNA sequence and are flanked by short-stem structures (13, 10, 7 bp) typical for gRNA/pre-mRNA hybrid molecules in vivo. The molecules were termed U5-ds13, U5-ds10 and U5-ds7 (Figure 2A). In order to analyze the initial endoribonucleolytic cleavage and the subsequent exoribonucleolytic trimming reaction of rTbMP42 simultaneously, the pre-mRNA sequence of the hybrid RNAs was 5′ radioactively labeled. For U5-ds13 RNA, initial cleavage was observed at position U16/U17. U5-ds10 and U5-ds7 were cleaved at the same phosphodiester bond, which in these two RNAs corresponds to positions U13/U14 (U5-ds10) and U10/U11 (U5-ds7) (Figure 2A). Following endoribonucleolytic cleavage, the ss 3′ U overhangs of all three RNAs become degraded in a 3′ to 5′ direction and the reaction stops at the adjacent double strand irrespective of its length (13, 10 or 7 bp). None of the three RNAs was cleaved to completion within 3 h of incubation. However, the cleavage rates are different for the three RNAs. For U5-ds13, 50% cleavage was achieved after 75 min. For U5-ds10 half-maximal cleavage was reached at 120 min, for U5-ds7 at 150 min (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Stem size influences the cleavage rate. (A) rTbMP42-mediated cleavage of gRNA/pre-mRNA hybrids U5-ds13, U5-ds10 and U5-ds7. Cartoons of the three RNAs are shown below the autoradiograms: top strand—pre-mRNA; bottom strand—gRNA. Radiolabeled RNA preparations (at the 5′ end of the pre-mRNA as shown by the *) were incubated with rTbMP42 and reaction products were resolved electrophoretically. Cleavage positions are marked by arrows: filled arrows—cleavage site at the ss/ds RNA junction; open arrows—cleavage sites within the U5-loop sequence. Numbers indicate pre-mRNA nucleotide positions. ‘Input’ represents an untreated RNA sample and ‘mock’ a sample that was incubated in the absence of rTbMP42. ‘T1’ represents an RNase T1 hydrolysis ladder and ‘OH’ an alkaline hydrolysis ladder. (B) Plot of the percentage of cleavage over time (circles: U5-ds13, squares: U5-ds10, triangles: U5-ds7). Data points are fitted to the Langmuir isotherm f(x) = (a*x)/(1 + b*x). Error bars represent SDs derived from at least five individual experiments.

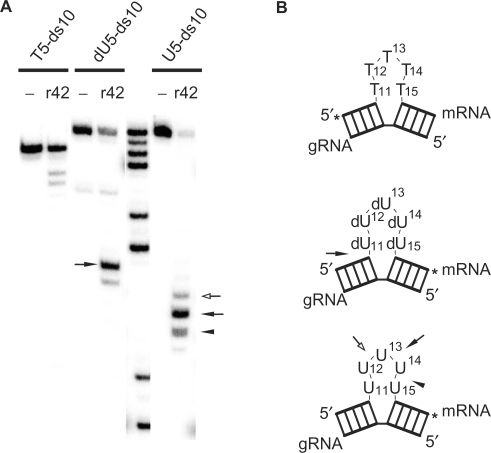

Cleavage requires a 2′-OH group

To further analyze the structural and chemical requirements of gRNA/pre-mRNA hybrid molecules for a rTbMP42-driven cleavage reaction, two derivatives of U5-ds10 RNA were synthesized: T5-ds10 and dU5-ds10 (Figure 3B). While T5-ds10 represents a DNA molecule, dU5-ds10 consists of mainly ribose-moieties except within the ‘U-loop’, which was synthesized from dU-phosphoramidites. As shown in Figure 3A, rTbMP42 was not able to cleave T5-ds10 even after 3 h of incubation. In contrast, dU5-ds10 was cleaved, however, at an ‘unusual’ position. Cleavage occurred predominately at the 5′ junction of the dU5-loop to the first ribonucleotide within the stem sequence (position A10/dU11). With the exception of a very weak cleavage site at dU11/dU12, no dU nucleotide within the ‘U-loop’ was cleaved. This suggests a requirement for a 2′ hydroxyl group, likely within a defined distance and sterical orientation 5′ to the cleavage site.

Figure 3.

Cleavage requires a proximal 2′-OH. (A) rTbMP42 (r42)-mediated cleavage of gRNA/pre-mRNA hybrids T5-ds10, dU5-ds10 and U5-ds10 RNA. The molecules were radiolabeled (*) and incubated with rTbMP42 for 3 h. Reaction products were resolved in denaturing polyacrylamide gels. ‘-’ represent mock treated samples. (B) Graphical representations of T5-ds10, dU5-ds10 and U5-ds10 (top to bottom). Cleavage positions/efficiencies are marked by arrows (filled arrows—most efficient cleavage site; open arrow—cleavage site of medium efficiency; arrow heads—least efficient cleavage site). T5-ds10, the ‘all DNA’ molecule, shows an increased electrophoretic mobility.

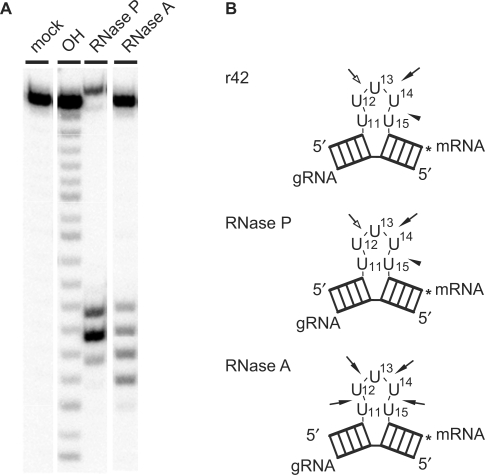

Structure probing demonstrates a defined ‘U5-loop’ topology

In order to rationalize the selective cleavage patterns of the different synthetic gRNA/pre-mRNA hybrid molecules by rTbMP42, we analyzed the 3D folding of the ‘U-loop’ sequence by enzymatic structure probing. For that we used the two ribonucleases RNase A and RNase P in conjunction with U5-ds10 as the RNA substrate. While both enzymes are single strand-specific (35,36), RNase P has been shown to be unable to cleave stacked nucleotides (37). In contrast, RNase A is known to resolve solvent-exposed as well as stacked nucleotides (38). Figure 4A shows a representative result of the probing data. RNase A cleaves all possible U-loop positions (U11/12, U12/13, U13/14 and U14/15) with equal intensity (Figure 4B). RNase P, however, cleaves U5-ds10 at only three positions and with different intensities: U13/U14>U12/U13>U14/U15 (Figure 4B). This indicates that the U5-sequence is indeed ss but two of the Us (U14 and U15) display base stacking characteristics (Figure 5A). rTbMP42 has the same cleavage specificity as RNase P and thus is able to distinguish between solvent-exposed and stacked nucleotides. Figure 5B shows an energy minimized 3D model of U5-ds10 (32) that integrates the enzyme probing data. The five-membered ‘U-loop’ is folded back on itself and creates a topology that exposes three of the nucleotides to the solvent. The remaining two Us are stacked between the two helical elements of the gRNA/pre-mRNA hybrid thereby minimizing entropic costs. Thus, the main scissile phosphodiester bond is mapped to a conformation that resembles a ss/ds-junction rather than a ss, looped-out organization. rTbMP42, similar to RNase P, is unable to resolve stacked nucleotides and cleaves the first unstacked U position within the U-loop of gRNA/pre-mRNA hybrid.

Figure 4.

Structure probing of U5-ds10 RNA. Radiolabeled (*) U5-ds10 RNA was subjected to cleavage reactions with RNase P and RNase A. (A) Electrophoretic separation of the cleavage products. ‘mock’—incubation in the absence of rTbMP42; ‘OH’—alkaline hydrolysis ladder. (B) Cartoons of U5-ds10 illustrating the cleavage positions by the different enzymes. Filled arrows: most efficient cleavage site(s); open arrows: medium efficiency cleavage sites; arrow heads: least efficient cleavage sites. The decreased electrophoretic mobility of full length U5-ds10 RNA in the RNase P lane is due to a loss in charge caused by digestion of the 3′-terminal phosphate group.

Figure 5.

3D representation of U5-ds10 RNA. (A) Cartoon of the 2D structure of the U5-ds10 pre-mRNA/gRNA hybrid illustrating the stacked and looped-out positions of the five-membered U-loop (orange). (B) 3D model of U5-ds10 RNA. Helices—gray; stacked/looped-out Us–color.

Zn2+ chelation and chemical modification of Zn2+-coordinating amino acids

TbMP42 contains no canonical nuclease motif and is only related to three other RNA editing proteins of unknown function (TbMP81, TbMP24 and TbMP18) (29). However, TbMP42 is highly homologous to a protein known as LC-7b in Leishmania. The two polypeptides share 51% identity on the amino acid level and based on that, we analyzed whether recombinant LC-7b has ribonucleolytic activity. The protein was expressed in E. coli as a MBP fusion protein and was purified to near homogeneity. Although the affinity tag could not be cleaved off after purification, rLC-7b/MBP showed an identical nucleolytic activity and cleavage specificity as rTbMP42 (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

Zn2+ ion chelation and protein modification. (A) Comparison of the rTbMP42 (r42)- and rLC-7b/MBP (r7b)-mediated cleavage reaction using radiolabeled U5-ds10 RNA. ‘Mock’—incubation in the absence of rTbMP42. Cleavage positions are marked by arrows. (B) Concentration-dependent cleavage inhibition by chelation of Zn2+ with 1,10 phenanthroline (pha). Half-maximal inhibition is achieved at a concentration of 0.12 mM. (C) U5-ds10 RNA (3′ radiolabeled at the pre-mRNA) cleavage using chemically modified rTbMP42 preparations: R, arginine modified; C, cysteine modified; H, histidine modified; D/E, aspartate/glutamate modified and ‘-’, unmodified. Cleavage positions are marked by arrows. The inhibition is concentration dependent as shown for the modification of D and E residues (D). Half-maximal inhibition is achieved at a 6-fold molar excess of modification reagent over rTbMP42.

For rTbMP42, it was shown that Zn2+ is required for folding and RNA ligand binding (30). Metal ions can serve as catalysts in active sites of nucleases such as in the large superfamily of nucleotidyl transferases including RNase H, transposase, retroviral integrase and Holliday-junction resolvase (39–41). In these examples, acidic amino acids and histidines coordinate one or two metal ions, mostly Zn2+, that activate a hydroxyl ion and position the phosphate backbone in close proximity to facilitate the inline attack of the nucleophile. DNA polymerase and alkaline phosphatase have been suggested to follow a two metal ion catalysis mechanism (42,43) and metal ions have also been proposed to be involved in the nucleolytic activity of catalytic RNAs (44).

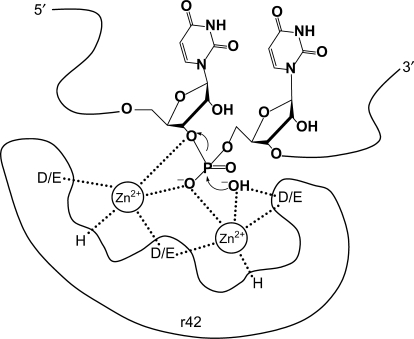

In order to analyze whether Zn2+ cations play a role in the cleavage reaction of rTbMP42, we tested whether the Zn2+-specific chelator 1,10 phenanthroline is able to inhibit the activity. Figure 6B shows a representative result. The enzyme activity is inhibited in a concentration-dependent fashion with a half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 0.12 mM. At concentrations ≥2 mM 1,10 phenanthroline completely blocks the cleavage reaction. This indicates a role for Zn2+ ions in the catalytic mechanism and further suggests that the blockage of amino acids known to coordinate Zn2+ ions (glutamic acid, aspartic acid and histidine) should impact the cleavage reaction as well. To test this hypothesis, we covalently modified Asp and Glu residues in rTbMP42 through a carbodiimide-mediated amide bond formation to glycine ethyl esters (45,46). Histidines were modified by carbethoxylation with DEPC (47) and as controls, we modified arginines and cysteines with phenylglyoxal and N-ethylmaleimide (48–50). The results are summarized in Figure 6C and D. As expected, the modification of arginines and cysteines had no effect on the cleavage activity and specificity of rTbMP42. In contrast, the modification of Asp/Glu and of His blocked the cleavage activity of rTbMP42 in a concentration dependent fashion. At a 100-fold molar excess of modification reagent complete inhibition (≥95%) was achieved.

DISCUSSION

TbMP42 is a component of the editosome that was characterized as an endo/exoribonuclease in vitro (30). The protein contains two zinc fingers and a putative OB-fold, but lacks typical nuclease motives. Here, we aimed at providing a first picture of the putative reaction mechanism of TbMP42 by studying the RNA recognition and cleavage modality of recombinant TbMP42 using synthetic RNA editing model substrates. The ss extra-helical Us were identified as determinants for an efficient cleavage reaction, while unpaired, stacked U nucleotides escape the cleavage reaction. Furthermore, Zn2+ ions play a critical role. Zn2+ chelation blocks enzyme function and chemical modification of metal ion-coordinating amino acids abolishes the activity. Thus, we propose that TbMP42 acts as a structure-sensitive ribonuclease that involves Zn2+ ions in its reaction pathway.

Although rTbMP42 has been shown to bind to short ssDNA and dsDNA molecules (30), the ‘all DNA’ substrate (T5-ds10) was not cleaved by the protein. This indicates a general nucleic acid binding capacity for rTbMP42, which likely is mediated by its C-terminal OB-fold. OB-folds are characterized by a barrel-shaped 3D structure of five β-sheets, which provide a nonsequence specific interaction platform for nucleic acids (51). However, the cleavage activity of rTbMP42 is RNA-specific. This was confirmed by utilizing a partial RNA/DNA hybrid molecule (dU5-ds10). With the exception of a very weak cleavage site at dU11/dU12, none of the dU nucleotides within dU5-ds10 was cleaved upon incubation with rTbMP42. Instead, cleavage was directed towards the first phosphodiester linkage that involves a ribose moiety at the 5′ RNA/DNA junction. This suggests a general requirement for a 2′ hydroxyl group in the cleavage reaction. It further indicates a defined directionality in positioning the OH-group, since the corresponding 3′ DNA/RNA junction was never cleaved. The data also point towards a defined structural flexibility within the catalytic pocket. The cleavage site in the RNA/DNA hybrid is some distance away from the cleavage position in the ‘all RNA’ U5-ds10 molecule. Lastly, we cannot exclude that the effect involves a kinetic difference. The ‘preferred’ cleavage positions could be processed much more rapidly than the cleavage sites at the base of the stem. Only in the absence of the fast processing sites (as in dU5-ds10) can the ‘slowly’ hydrolyzed positions be identified.

In vivo, TbMP42 must recognize and cleave a wide array of different gRNA/pre-mRNA substrate molecules. They are characterized by varying numbers of looped-out U-nucleotides and based on the described results we propose that rTbMP42 indiscriminately interacts with these RNAs. However, the protein cleaves only solvent-exposed Us located proximal to an RNA helix. Stacked Us on top of helical elements are not cleaved. The 3D model of U5-ds10 illustrates these characteristics. RNase structure probing established that the U-loop in U5-ds10 has defined conformational characteristics: three U nucleotides are extra-helical and solvent-exposed, while two Us adopt an intra-helical, stacked conformation. This is an expected result since bulge regions have been shown to form well-defined structures. The precise topology depends on the chemical nature of the bulged residue(s), the identity of the nucleotides flanking the bulge, and the length of the helical elements (52–55). Some proteins have been shown to bind and stabilize defined conformers out of an ensemble of different RNA foldings (56–58). However, from the presented data, we cannot conclude whether that applies to rTbMP42 as well. Furthermore, due to the fact that the length of the adjacent stem regions contributes to the cleavage rate of the reaction, we also cannot exclude that subtle structural differences induced by the accommodation of unpaired Us into the stems propagate through the entire RNA and represent a recognition signal for the protein (52). Importantly, rTbMP42 is not able to resolve stacked positions and thus, the two Us in U5-ds10 remain uncleaved. In vivo, they likely will be ‘re-edited’ during a subsequent reaction cycle, provided they are in a solvent-exposed, i.e. extrahelical conformation. Possibly, this type of structural limitation contributes to the frequent occurrence of re- and mis-editing events that have been observed in vivo (59,60). Although U1-ds10 RNA was not cleaved in our assay, depending on the sequence context it is energetically possible that single nucleotides adopt an extra-helical conformation as shown for single-base bulges as part of short model A-form RNAs (54). In that case, we would predict that even a single nucleotide bulge will be cleaved by rTbMP42.

Due to the absence of an archetypical nuclease motif in TbMP42, the catalytic reaction center is difficult to trace. However, the absence of primary sequence homology does not preclude proteins from sharing 3D structural elements and as a consequence from functional homology (61). Exoribonuclease superfamilies in general show very limited sequence homology (62). For enzymes that rely on metal ion-driven catalysis mechanisms (63), a large number of structural arrangements of acidic amino acids or electron donating groups can be combined to accommodate the complexation of bivalent cation(s). For TbMP42, we identified Zn2+ ions as being crucial for the activity of the protein. Chelation of Zn2+ completely abolished nuclease activity. If one or multiple Zn2+ ions are held in place within the catalytic pocket of TbMP42, only certain amino acids are candidates for coordinating the metal ion(s). This includes D and E residues or amino acids capable of donating a free electron pair (H, N, Q). Glutamate and aspartate are the most obvious choices for a direct involvement. Indeed, a conserved Asp residue in conjunction with the scissile phosphate has been identified in all polymerases and nucleases to date to jointly coordinate two metal ions (63). Asp seems to be preferred for the coordination of metal ions, probably because it has fewer rotamer conformations than Glu and as a consequence is more rigid. Covalently modifying D and E residues in rTbMP42 resulted in a complete loss of the nuclease activity supporting the above-described scenario. The modification of histidines abolished function as well. This could be due to a direct involvement of histidines in the metal ion coordination as shown in the RNase H family (39,64) or because of a proton shuttle function of a His residue (65). Since the modification of cysteines did not affect the activity of rTbMP42, this confirms that functional Zn-finger motifs are not required for the activity of the protein as previously suggested by Brecht et al. (30). Similarly, the modification of arginines did not affect the activity of rTbMP42. This excludes a contribution of the positive side chain of arginines in compensating the polyanionic properties of the bound gRNA/pre-mRNA ligand (6). Figure 7 shows a model of the putative catalytic pocket of rTbMP42 integrating the above-described experimental data. Although we cannot exclude that the modification reactions induced long-range effects within TbMP42, our model finds remarkable support in the recently determined 3D structure of RNase J from Thermus thermophilus. RNase J is an endo/exoribonuclease and the dual activity has been shown to be carried out by a single active site. The catalytic pocket of RNase J contains two zinc ions, that are coordinated by Asp and His residues (66). The C-terminal domain of TbMP42, which holds the ribonuceolytic activities of the protein (30) contains 19 D and E residues and seven histidines. Site-directed mutagenesis experiments should be able to identify the crucial residues within the catalytic pocket of the protein.

Figure 7.

The putative metal ion reaction center. Model of the hypothetical catalytic pocket of TbMP42 (r42) with two Zn2+ ions coordinated (dashed lines) by D, E and H residues in concert with a non-bridging oxygen of the scissile phosphate (adopted from ref. 44). (OH−) represents a nucleophilic hydroxyl anion derived from a deprotonated water molecule.

Taken together, the described data provide a first understanding on how rTbMP42 catalyzes the cleavage of gRNA/pre-mRNA hybrid molecules. The protein interacts with dsRNA domains and recognizes unpaired, looped-out uridylate residues. rTbMP42 acts as a structure-sensitive, U-specific endo/exoribonuclease likely following a Zn2+ ion-dependent catalysis mechanism. Acidic amino acids and histidines play a role in the formation of the putative catalytic pocket.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are thankful to Larry Simpson for plasmid pMalc2x_Lt7b, and to Ralf Ficner and Jóhanna Arnórsdóttir for dU5-ds10. H.U.G. is supported as an International Research Scholar of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) and by the German Research Council (DFG-SFB579). Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by the German Research Council (DFG-SFB579).

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Madison-Antenucci S, Grams J, Hajduk SL. Editing machines: the complexities of trypanosome RNA editing. Cell. 2002;108:435–438. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00653-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simpson L, Aphasizhev R, Gao G, Kang X. Mitochondrial proteins and complexes in Leishmania and Trypanosoma involved in U-insertion/deletion RNA editing. RNA. 2004;10:159–170. doi: 10.1261/rna.5170704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stuart KD, Schnaufer A, Ernst NL, Panigrahi AK. Complex management: RNA editing in trypanosomes. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2005;30:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Müller UF, Lambert L, Göringer HU. Annealing of RNA editing substrates facilitated by guide RNA-binding protein gBP21. EMBO J. 2001;20:1394–1404. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.6.1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blom D, Burg J, Breek CK, Speijer D, Muijsers AO, Benne R. Cloning and characterization of two guide RNA-binding proteins from mitochondria of Crithidia fasciculata: gBP27, a novel protein, and gBP29, the orthologue of Trypanosoma brucei gBP21. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:2950–2962. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.14.2950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Müller UF, Göringer HU. Mechanism of the gBP21-mediated RNA/RNA annealing reaction: matchmaking and charge reduction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:447–455. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.2.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aphasizhev R, Aphasizheva I, Nelson RE, Simpson L. A 100-kD complex of two RNA-binding proteins from mitochondria of Leishmania tarentolae catalyzes RNA annealing and interacts with several RNA editing components. RNA. 2003;9:62–76. doi: 10.1261/rna.2134303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schumacher MA, Karamooz E, Zíková A, Trantírek L, Lukes J. Crystal structures of T. brucei MRP1/MRP2 guide-RNA binding complex reveal RNA matchmaking mechanism. Cell. 2006;126:701–711. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seiwert SD, Heidmann S, Stuart K. Direct visualization of uridylate deletion in vitro suggests a mechanism for kinetoplastid RNA editing. Cell. 1996;84:831–841. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81062-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kable ML, Seiwert SD, Heidmann S, Stuart K. RNA editing: a mechanism for gRNA-specified uridylate insertion into precursor mRNA. Science. 1996;273:1189–1195. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5279.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Piller KJ, Rusché LN, Cruz-Reyes J, Sollner-Webb B. Resolution of the RNA editing gRNA-directed endonuclease from two other endonucleases of Trypanosoma brucei mitochondria. RNA. 1997;3:279–290. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aphasizhev R, Aphasizheva I, Simpson L. A tale of two TUTases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:10617–10622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1833120100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ernst NL, Panicucci B, Igo R.P., Jr, Panigrahi AK, Salavati R, Stuart K. TbMP57 is a 3' terminal uridylyl transferase (TUTase) of the Trypanosoma brucei editosome. Mol. Cell. 2003;11:1525–1536. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00185-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aphasizhev R, Simpson L. Isolation and characterization of a U-specific 3'-5'-exonuclease from mitochondria of Leishmania tarentolae. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:21280–21284. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100297200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Igo RP, Jr, Weston DS, Ernst NL, Panigrahi AK, Salavati R, Stuart K. Role of uridylate-specific exoribonuclease activity in Trypanosoma brucei RNA editing. Eukaryot. Cell. 2002;1:112–118. doi: 10.1128/EC.1.1.112-118.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McManus MT, Shimamura M, Grams J, Hajduk SL. Identification of candidate mitochondrial RNA editing ligases from Trypanosoma brucei. RNA. 2001;7:167–175. doi: 10.1017/s1355838201002072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schnaufer A, Panigrahi AK, Panicucci B, Igo R.P., Jr, Wirtz E, Salavati R, Stuart K. An RNA ligase essential for RNA editing and survival of the bloodstream form of Trypanosoma brucei. Science. 2001;291:2159–2162. doi: 10.1126/science.1058955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang CE, Cruz-Reyes J, Zhelonkina AG, O'Hearn S, Wirtz E, Sollner-Webb B. Roles for ligases in the RNA editing complex of Trypanosoma brucei: band IV is needed for U-deletion and RNA repair. EMBO J. 2001;20:4694–4703. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rusché LN, Cruz-Reyes J, Piller KJ, Sollner-Webb B. Purification of a functional enzymatic editing complex from Trypanosoma brucei mitochondria. EMBO J. 1997;16:4069–4081. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.13.4069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aphasizhev R, Aphasizheva I, Nelson RE, Gao G, Simpson AM, Kang X, Falick AM, Sbicego S, Simpson L. Isolation of a U-insertion/deletion editing complex from Leishmania tarentolae mitochondria. EMBO J. 2003;22:913–924. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Panigrahi AK, Gygi SP, Ernst NL, Igo R.P., Jr, Palazzo SS, Schnaufer A, Weston DS, Carmean N, Salavati R, Aebersold R, et al. Association of two novel proteins, TbMP52 and TbMP48, with the Trypanosoma brucei RNA editing complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:380–389. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.2.380-389.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carnes J, Stuart K. Göringer HU. RNA Editing. Springer Verlag, Heidelberg: 2008. Working Together: the RNA Editing Machinery in Trypanosoma brucei; pp. 143–164. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schnaufer A, Ernst NL, Palazzo SS, O'Rear J, Salavati R, Stuart K. Separate insertion and deletion subcomplexes of the Trypanosoma brucei RNA editing complex. Mol. Cell. 2003;12:307–319. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00286-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Worthey EA, Schnaufer A, Mian IS, Stuart K, Salavati R. Comparative analysis of editosome proteins in trypanosomatids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:6392–6408. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trotter JR, Ernst NL, Carnes J, Panicucci B, Stuart K. A deletion site editing endonuclease in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Cell. 2005;20:403–412. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carnes J, Trotter JR, Ernst NL, Steinberg A, Stuart K. An essential RNase III insertion editing endonuclease in Trypanosoma brucei. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:16614–16619. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506133102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kang X, Rogers K, Gao G, Falick AM, Zhou S, Simpson L. Reconstitution of uridine-deletion precleaved RNA editing with two recombinant enzymes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:1017–1022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409275102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rogers K, Gao G, Simpson L. Uridylate-specific 3′ 5′-exoribonucleases involved in uridylate-deletion RNA editing in trypanosomatid mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:29073–29080. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704551200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Panigrahi AK, Schnaufer A, Carmean N, Igo R.P., Jr, Gygi SP, Ernst NL, Palazzo SS, Weston DS, Aebersold R, Salavati R, et al. Four related proteins of the Trypanosoma brucei RNA editing complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:6833–6840. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.20.6833-6840.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brecht M, Niemann M, Schlüter E, Müller UF, Stuart K, Göringer HU. TbMP42, a protein component of the RNA editing complex in African trypanosomes, has endo-exoribonuclease activity. Mol. Cell. 2005;17:621–630. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Puglisi JD, Tinoco I., Jr Absorbance melting curves of RNA. Method. Enzymol. 1989;180:304–325. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(89)80108-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lavery R, Zakrzewska K, Sklenar H. JUMNA (junction minimisation of nucleic acids) Comput. Phys. Commun. 1995;91:135–158. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seiwert SD, Stuart K. RNA editing: transfer of genetic information from gRNA to precursor mRNA in vitro. Science. 1994;266:114–117. doi: 10.1126/science.7524149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alatortsev VS, Cruz-Reyes J, Zhelonkina AG, Sollner-Webb B. Trypanosoma brucei RNA editing: coupled cycles of U deletion reveal processive activity of the editing complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008;28:2437–2445. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01886-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raines RT. Ribonuclease A. Chem. Rev. 1998;98:1045–1066. doi: 10.1021/cr960427h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marquez SM, Chen JL, Evans D, Pace NR. Structure and function of eukaryotic Ribonuclease P RNA. Mol. Cell. 2006;24:445–456. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Desai NA, Shankar V. Single-strand-specific nucleases. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2003;26:457–491. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2003.tb00626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parés X, Nogues MV, de Llorens R, Cuchillo CM. Structure and function of ribonuclease A binding subsites. Essays Biochem. 1991;26:89–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nowotny M, Gaidamakov SA, Crouch RJ, Yang W. Crystal structures of RNase H bound to an RNA/DNA hybrid: substrate specificity and metal-dependent catalysis. Cell. 2005;121:1005–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rice PA, Baker TA. Comparative architecture of transposase and integrase complexes. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2001;8:302–307. doi: 10.1038/86166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ariyoshi M, Vassylyev DG, Iwasaki H, Nakamura H, Shinagawa H, Morikawa K. Atomic structure of the RuvC resolvase: a Holliday junction-specific endonuclease from E. coli. Cell. 1994;78:1063–1072. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90280-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beese LS, Steitz TA. Structural basis for the 3′-5′ exonuclease activity of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I: a two metal ion mechanism. EMBO J. 1991;10:25–33. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07917.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim EE, Wyckoff HW. Reaction mechanism of alkaline phosphatase based on crystal structures. Two-metal ion catalysis. J. Mol. Biol. 1991;218:449–464. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90724-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Steitz TA, Steitz JA. A general two-metal-ion mechanism for catalytic RNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:6498–6502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoare DG, Koshland D.E., Jr A procedure for the selective modification of carboxyl groups in proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1966;88:2057. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hoare DG, Koshland D.E., Jr A method for the quantitative modification and estimation of carboxylic acid groups in proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1967;242:2447–2453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miles EW. Modification of histidyl residues in proteins by diethylpyrocarbonate. Method Enzymol. 1977;47:431–442. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(77)47043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takahashi K. The reaction of phenylglyoxal with arginine residues in proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1968;243:6171–6179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smyth DG, Nagamtsu A, Fruton JS. Reactions of N-ethylamine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1960;82:4600. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smyth DG, Blumenfeld OO, Konigsberg W. Reactions of N-ethylmaleimide with peptides and amino acids. Biochem. J. 1964;91:589–595. doi: 10.1042/bj0910589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Theobald DL, Mitton-Fry RM, Wuttke DS. Nucleic acid recognition by OB-fold proteins. Ann. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2003;32:115–133. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.32.110601.142506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Popenda L, Adamiak RW, Gdaniec Z. Bulged adenosine influence on the RNA duplex conformation in solution. Biochem. 2008;47:5059–5067. doi: 10.1021/bi7024904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Luebke KJ, Landry SM, Tinoco I., Jr Solution conformation of a five-nucleotide RNA bulge loop from a group I intron. Biochem. 1997;36:10246–10255. doi: 10.1021/bi9701540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zacharias M, Sklenar H. Conformational analysis of single-base bulges in A-form DNA and RNA using a hierarchical approach and energetic evaluation with a continuum solvent model. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;289:261–275. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barthel A, Zacharias M. Conformational transitions in RNA single uridine and adenosine bulge structures: a molecular dynamics free energy simulation study. Biophys. J. 2006;90:2450–2462. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.076158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Valegard K, Murray JB, Stockley PG, Stonehouse NJ, Liljas L. Crystal structure of an RNA bacteriophage coat protein-operator complex. Nature. 1994;371:623–626. doi: 10.1038/371623a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Long KS, Crothers DM. Characterization of the solution conformations of unbound and Tat peptide-bound forms of HIV-1 TAR RNA. Biochem. 1999;38:10059–10069. doi: 10.1021/bi990590h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Al-Hashimi HM. Dynamics-based amplification of RNA function and its characterization by using NMR spectroscopy. ChemBioChem. 2005;6:1506–1519. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Decker CJ, Sollner-Webb B. RNA editing involves indiscriminate U changes throughout precisely defined editing domains. Cell. 1990;61:1001–1011. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90065-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sturm NR, Maslov DA, Blum B, Simpson L. Generation of unexpected editing patterns in Leishmania tarentolae mitochondrial mRNAs: misediting produced by misguiding. Cell. 1992;70:469–476. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weaver LH, Grutter MG, Remington SJ, Gray TM, Isaacs NW, Matthews BW. Comparison of goose-type, chicken-type, and phage-type lysozymes illustrates the changes that occur in both amino acid sequence and three-dimensional structure during evolution. J. Mol. Evol. 1984;21:97–111. doi: 10.1007/BF02100084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zuo Y, Deutscher MP. Exoribonuclease superfamilies: structural analysis and phylogenetic distribution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:1017–1026. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.5.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang W, Lee JY, Nowotny M. Making and breaking nucleic acids: two-Mg2+-ion catalysis and substrate specificity. Mol. Cell. 2006;22:5–13. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rivas FV, Tolia NH, Song JJ, Aragon JP, Liu J, Hannon GJ, Joshua-Tor L. Purified Argonaute2 and an siRNA form recombinant human RISC. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005;12:340–349. doi: 10.1038/nsmb918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Christianson DW, Cox JD. Catalysis by metal-activated hydroxide in zinc and manganese metalloenzymes. Ann. Rev. Biochem. 1999;68:33–57. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.de la Sierra-Galley IL, Zig L, Jamalli A, Putzer H. Structural insight into the dual activity of RNase J. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:206–212. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]