Abstract

Cells with functional DNA mismatch repair (MMR) stimulate G2 cell cycle checkpoint arrest and apoptosis in response to N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG). MMR-deficient cells fail to detect MNNG-induced DNA damage, resulting in the survival of “mutator” cells. The retrograde (nucleus-to-cytoplasm) signaling that initiates MMR-dependent G2 arrest and cell death remains undefined. Since MMR-dependent phosphorylation and stabilization of p53 were noted, we investigated its role(s) in G2 arrest and apoptosis. Loss of p53 function by E6 expression, dominant-negative p53, or stable p53 knockdown failed to prevent MMR-dependent G2 arrest, apoptosis, or lethality. MMR-dependent c-Abl-mediated p73α and GADD45α protein up-regulation after MNNG exposure prompted us to examine c-Abl/p73α/GADD45α signaling in cell death responses. STI571 (Gleevec™, a c-Abl tyrosine kinase inhibitor) and stable c-Abl, p73α, and GADD45α knockdown prevented MMR-dependent apoptosis. Interestingly, stable p73α knockdown blocked MMR-dependent apoptosis, but not G2 arrest, thereby uncoupling G2 arrest from lethality. Thus, MMR-dependent intrinsic apoptosis is p53-independent, but stimulated by hMLH1/c-Abl/p73α/GADD45α retrograde signaling.

Loss of DNA mismatch repair (MMR)3 leads to a mutator phenotype (1). MMR-deficient cells lack G2 arrest responses (2) and are resistant (3), in terms of cell death and long-term survival, to alkylating agents. MMR-proficient cells respond to N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG) by inducing G2 arrest and cell death, typically through apoptosis (4). Thus, along with correcting DNA mismatches and 1–2-bp loops, MMR also acts to arrest cells in G2, presumably preventing mutation “fixation” through cell division. Furthermore, MMR acts to eliminate damaged cells by signaling apoptosis. The signaling responses leading from MMR-dependent detection of DNA damage to G2 arrest, as well as to downstream alterations in extrinsic or intrinsic apoptotic signals resulting in mitochondrial dysfunction, remain ill defined. Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancers are a result of genetic deletion of MMR genes, typically human (h) MSH2 (mutShomolog-2) or MLH1 (mutLhomolog-1) (5, 6). Notably, many sporadic human colon cancers also have defective MMR as a result of epigenetic changes such as hMLH1 promoter hypermethylation and loss of expression (7). These cancers have hallmark microsatellite instability (8) and are resistant (sometimes ≥100-fold) to alkylating agents (9).

Apoptosis is a distinct cell death process that occurs under various physiological and pathological situations. Initiation of apoptosis can occur by extrinsic or intrinsic pathways. Both pathways typically culminate in caspase activation. Caspases are cysteine protease zymogens that cleave specific cellular substrates and dismantle the cell, leading to specific morphologic features of apoptosis, including nuclear blebbing, DNA fragmentation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and specific proteolyses of DNA repair proteins.

Intrinsic apoptosis is initiated by release of apoptogenic factors such as cytochrome c, apoptosis-inducing factor, and Smac/DIABLO. Once released into the cytosol from mitochondria, cytochrome c interacts with Apaf-1 and activates caspase-9 (10). Caspase-9 then activates other effector caspases (e.g. caspase-3, -6, and -7) that dismantle and “clean up” the cell.

Extrinsic apoptosis is initiated by stimulation of death receptors of the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, such as CD95 (APO-1/Fas) and TRAIL receptors. In contrast to intrinsic apoptosis that activates caspase-9 from mitochondrial dysfunctional processes (10), stimulation of the extrinsic apoptotic pathway initially activates caspase-8, which, in turn, propagates the apoptotic signal by direct cleavage of downstream effector caspases such as caspase-9 and caspase-3. Although activated caspase-8 is fairly specific to the extrinsic apoptotic pathway, once activated, it eventually triggers intrinsic apoptotic processes, causing cytochrome c release and caspase-9 activation (11). Reciprocally, once caspase-9 is activated, it can stimulate caspase-8 activation. Thus, the temporal kinetics of initial caspase-9 versus caspase-8 activation can be used to differentiate intrinsic versus extrinsic apoptotic signaling pathways, respectively.

Alkylating agents are commonly used cancer chemotherapeutic agents that can kill cells by apoptotic processes (12). Monofunctional alkylating agents can be divided into two major groups, Sn1 and Sn2. Sn2-type alkylating agents include methyl methanesulfonate and dimethyl sulfate. Sn1-type alkylating agents include temozolomide, MNNG, and N-methyl-N′-nitrosourea and are cytotoxic to cancer cells at lower concentrations than Sn2-type agents. Sn1-type compounds have therefore been used more often as antitumor agents with limited success. Treatment of cancer cells with Sn1-type agents such as MNNG and temozolomide gives rise to N7-methylguanine, N3-methyladenine, O4-methylthymine, and O6-methylguanine DNA lesions. N7-Methylguanine and N3-methyladenine DNA lesions are removed by base excision repair. O6-Methylguanine can be repaired by O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase, which removes the methyl group from guanine in a single step and transfers it to an internal cysteine residue (Cys145) on O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (as reviewed in Ref. 13). This reaction inactivates O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase, but directly restores guanine in DNA without DNA incision, synthesis, or ligation steps. Cells that do not express detectable O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase levels or are treated with O6-benzylguanine (a selective O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase inhibitor) are hypersensitive to O6-methylguanine-inducing agents (13). Other DNA repair pathways such as nucleotide excision repair and MMR may also process O6-methylguanine lesions (4). A hallmark of MMR-mediated response to these DNA lesions is prolonged G2 arrest and lethality. In contrast, MMR-deficient cells are highlighted by “damage tolerance” with heightened mutation rates (14). Defining the exact retrograde signaling events from MMR-specific DNA lesion detection to G2 arrest and apoptosis remains important in understanding the efficiency of mutational avoidance of the MMR system.

Numerous studies have attempted to elucidate the signaling events that occur between MMR detection of DNA lesions in the nucleus and those involved in programmed cell death. Alkylation-induced signaling and apoptotic responses require MutSα (the hMSH2-hMSH6 heterodimer) and MutLα (the hMLH1-hPMS2 heterodimer) protein complexes (9, 15) and human exonuclease I (16). A significant number of signaling molecules, including p53, Chk1, Chk2, ATR, ATM, and p38α mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), were reported to regulate MMR-dependent signaling cascades, culminating in G2 arrest and apoptosis (15, 17, 18). A recent study suggested that ATR, and not ATM, is activated in the presence of MutSα and MutLα protein complexes (19), although this evidence was derived from cell-free extracts.

In addition to the above-mentioned signaling pathways, a role for p53 in MMR-dependent apoptosis was also suggested. Our laboratory was the first to demonstrate a differential MMR-dependent p53 stabilization after 6-thioguanine (6-TG) or IR exposure (14). Results from other laboratories suggested that MMR-dependent apoptosis in human colon cancer cells after MNNG or N-methyl-N′-nitrosourea treatment is dependent on p53 and hMLH1, although isogenic cells were not used (20). Furthermore, temozolomide-induced apoptotic responses were reported to be dependent on p53 (21), although these responses were not examined for MMR dependence. In contrast, MNNG- or temozolomide-induced apoptosis was observed in TK6 cells that express viral E6 protein, making cells functionally null for p53 (22). Other studies suggested that p73, a homolog of p53, is activated in response to cisplatin in an MMR-specific manner (23–25). Indeed, hPMS2 (a binding partner of hMLH1 and component of the hMutLα complex) may directly interact with stabilized p73α after cisplatin exposure (26). A role for p73α in MMR-dependent apoptosis was not, however, mechanistically explored. Thus, to date, an in-depth study of MMR-dependent retrograde (nucleus-to-cytoplasm) signaling that culminates in cell death (apoptosis) has not been performed.

Using isogenic hMLH1-deficient versus hMLH1-corrected human colon cancer cells, we elucidated the hMLH1/c-Abl/p73α/GADD45α (growth arrest- and DNA damage-inducible-45α) signaling pathway that controls apoptosis in response to MNNG treatment. We demonstrate functional roles for c-Abl and GADD45α in MMR-dependent G2 arrest, apoptosis, and lethality. We also demonstrate a specific role for c-Abl-induced p73α stabilization in apoptotic responses and survival after MNNG treatment, although this p53 homolog plays no role in G2 arrest responses. Thus, we provide the first evidence that MMR-dependent G2 arrest responses can be uncoupled from apoptosis initiation. G2 arrest may therefore be required for mutational avoidance, but not for apoptosis or lethality. Finally, we show that although p53 is differentially stabilized in an MMR-dependent manner, this signaling response plays no apparent role(s) in G2 arrest responses, apoptosis, or lethality after MNNG treatment. Clinically, our data strongly suggest that inhibitors of c-Abl such as Gleevec™ are ill suited for combination therapy with temozolomide and cisplatin, which depend on functional MMR responses for efficacy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and Chemicals—MNNG, staurosporine, propidium iodide, puromycin, and RNase A were purchased from the Sigma. MNNG was dissolved in Me2SO at 100 mm and stored at -20 °C. STI571 (Gleevec™, Novartis, East Hanover, NJ) was dissolved in water at 5 mm and stored at -20 °C. Stock concentrations were determined by spectrophotometric analyses.

Plasmids and Short Hairpin RNA (shRNA)—Full-length hMLH1 cDNA was generously provided by Drs. A. Buermeyer and R. M. Liskay (Oregon Health Sciences University, Portland, OR). Human DD1 transcriptionally inactive, dominant-negative p53 mutant cDNA was a kind gift from Dr. George Stark (Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH). Human p73α and p73β isoforms were kind gifts from Dr. Meredith Irwin (Hospital for Sick Children Research Institute, Ontario, Canada). Human papillomavirus E6 cDNA was obtained from Dr. C. Reznick (University of Wisconsin Medical School, Madison, WI), cloned into a mammalian cytomegalovirus expression vector, and used to transfect RKO or HCT116 cells as indicated (14). Human scrambled shRNA (shSCR) sequence and p53 shRNA (shp53) were obtained from Dr. M. Jackson (Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland) (27).

Cell Culture, Transfections, Treatments, and Colony-forming Ability Assays—HCT116 and HCT116 3-6 cells were generously provided by Dr. C. R. Boland (Baylor College of Medicine, Dallas, TX). MMR-deficient RKO6 and MMR-proficient RKO7 clones were generated by transfecting cytomegalovirus-driven vector-only plasmid DNA or cytomegalovirus-directed plasmid expressing full-length hMLH1 cDNA using Lipofectamine 2000™ (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Stable clones were selected with G418 by limiting dilution. The human SK-N-AS neuroblastoma cell line was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Mouse MEF1-1 (Gadd45α+/+) and MEF11-1 (Gadd45α-/-) cells were provided by Dr. A. J. Fornace (Georgetown University, Washington, D. C.) and grown as described (28). All other human cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Cambrex Bio Science, Walkersville, MD) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone, Logan, UT) supplemented with penicillin (10 units/ml) and streptomycin (10 units/ml). For stable shp53, c-Abl shRNA (shABL), p73α shRNA (shp73), and GADD45α shRNA (shGADD45α) knockdown clones, RKO6 and RKO7 cells were infected with Polybrene-supplemented medium obtained from Phoenix and 293T packaging cells transfected with lentiviral vector pSUPER-p53, retroviral vector pShag2-c-Abl, lentiviral vector pLKO2-p73α, and lentiviral vector pLKO2-GADD45α as described in the accompanying article (46).

All drug treatments were performed in medium lacking antibiotics or selective agents. For alkylation exposure, cells were incubated with MNNG (2–10 μm, 1 h). Where indicated, cells were pretreated with 25 μm STI571 for 2 h prior to MNNG exposure. Cells were then washed and scraped, and whole cell extracts were harvested at 24–96 h as indicated. Cells were also pretreated as indicated with the caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-fmk (caspase inhibitor I, EMD Biosciences, La Jolla, CA) or Z-DEVD-fmk (caspase-3 inhibitor II, EMD Biosciences) at 20 or 50 μm, respectively. Colony-forming assays were then performed (14) three or more times in triplicate, and statistics were completed as described below.

Flow Cytometry—For cell cycle distribution assays, adherent and floating cells were treated with 50 μg/ml propidium iodide and 100 μg/ml RNase A at 4 °C and analyzed for DNA content and apoptotic populations using TUNEL assays (29). Cells were then analyzed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences), and 10,000 events were plotted using CellQuest software.

Immunoblot Analyses—Whole cell extracts and Western blots were prepared as described (30). For Western blots, primary antibodies against the following proteins were used at the indicated dilutions: caspase-8 (1C12; Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA), 1:1000; cleaved caspase-9 (Asp315; Cell Signaling), 1:1000; PARP-1 (Cell Signaling), 1:1000; Bax (Cell Signaling), 1:1000; hMLH1 (Ab-2; Oncogene Research Products, Boston, MA), 1:1000; hMSH2 (Ab-1; Oncogene Research Products), 1:500; hPMS2 (Pharmingen), 1:1000; c-Abl (Ab-3; Oncogene Research Products), 1:1000; p53 (DO-1; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), 1:5000; GADD45α (H-165; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), 1:1000; glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; 6C5; EMD Chemicals, Inc., San Diego, CA), 1:50,000; p21 (Ab-1; EMD Chemicals, Inc.), 1:1000; p73α (5B429; Imgenex Corp., San Diego, CA), 1:2000; and phospho-specific p53 (Ser15; Cell Signaling), 1:1,000. Detection was performed using appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and SuperSignal chemiluminescence substrate (Pierce) on Fuji RX medical x-ray film.

Statistics—All studies were performed in triplicate at a minimum. The Western blots presented are data from experiments performed three times with similar results. Quantification of protein levels was performed by scanning x-ray films and analyzing the scans using NIH Image J software. Statistical significance was determined using paired Student's t tests.

RESULTS

Lethality Correlates with Apoptosis in MNNG-treated MMR-corrected RKO Cells—Human RKO cells are MMR-deficient due to hMLH1 promoter hypermethylation and are incapable of forming the hMutLα complex (i.e. hMLH1-hPMS2 heterodimer), rendering them deficient in both hMLH1 and hPMS2 protein expression. A prior study reported that hMLH1 overexpression is toxic (31); however, we selected RKO clones that express hMLH1 at levels comparable to endogenous protein amounts in wild-type cells. Selection of clones with hMLH1 levels comparable to endogenous levels in wild-type cells was critical for long-term stability. Various RKO clones were established, and all showed increased sensitivity to MNNG or 6-TG (Fig. 1) (46). However, no clone demonstrated polyploidy in 3 or more years in culture, unlike previous reports of RKO clones in which hMLH1 expression was driven to abnormally high levels (32).

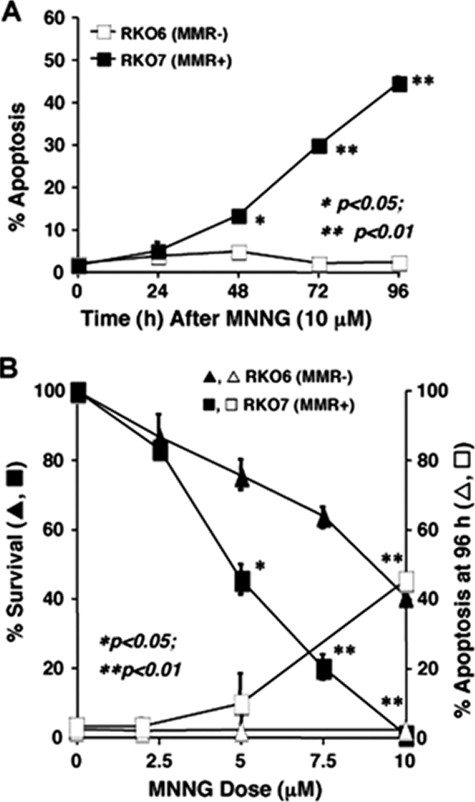

FIGURE 1.

Enhanced apoptosis in MMR-proficient cells after MNNG exposure. A, stable RKO6 (hMLH1-/MMR-) and genetically matched, hMLH1-transfected RKO7 (hMLH1+/MMR+) cells were generated and analyzed (46). MMR- RKO6 versus MMR+ RKO7 cells were then exposed to MNNG (10 μm, 1 h) and monitored for apoptosis using TUNEL and G1 subpopulations. Apoptosis was dramatically increased in RKO7 (MMR+) cells versus RKO6 (MMR-) cells at 48 h. B, RKO6 (MMR-) and RKO7 (MMR+) cells were treated with increasing MNNG doses (μm, 1 h), and apoptosis and survival end points were analyzed. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

MMR+ clone RKO7 was chosen to further explore the role of hMLH1 expression in apoptotic responses after MNNG treatment. A dramatic but delayed MMR-dependent apoptotic response in RKO7 cells after a single dose of MNNG (10 μm, 1 h) was observed, with peak levels appearing at 72–96 h post-exposure (Fig. 1A). Apoptosis gradually declined in RKO7 cells at times >96 h, until few cells remained. MMR+ RKO7 cells showed a strong correlation between lethality (i.e. loss of colony-forming ability) and apoptosis induction at 96 h (Fig. 1B). In contrast, MMR- RKO6 cells were not responsive to MNNG in terms of apoptosis (Fig. 1B), even at doses ≥10 μm, where loss of survival was noted. In fact, RKO cells exposed to 20 μm MNNG did not elicit appreciable apoptotic responses, but did show an enlarged and “flattened out” morphology. Cell death in MMR- RKO6 cells after high dose MNNG exposure was not caused by apoptosis. To determine that this MMR-dependent apoptosis response was unique to MNNG treatment, we treated MMR-proficient and MMR-deficient cells with cisplatin. Using TUNEL as an output for apoptosis, we found that there was no appreciable difference in the amount of apoptosis measured in MMR-proficient and MMR-deficient cells (supplemental Fig. 1).

MMR-dependent Apoptosis Induced by MNNG Occurs via the Intrinsic Pathway—To determine whether MMR-dependent apoptosis in response to MNNG (10 μm, 1 h) occurred through intrinsic or extrinsic apoptotic pathways, we monitored the kinetics of caspase-8 and caspase-9 as well as PARP-1 proteolyses in RKO6 (MMR-) versus RKO7 (MMR+) cells. Significant caspase-9 activation cleavage (35 kDa) occurred at 48 h post-treatment in RKO7 cells at a time concomitant with significant levels of apoptosis (Fig. 2A, arrow). Notably, caspase-9 cleavage was noted at 48 h post-treatment, nearly 20 h prior to the activation cleavage of caspase-8 (43 kDa; arrow) observed at 72 h. Activation of caspase-9 prior to caspase-8 strongly suggested that the intrinsic apoptotic pathway was activated by MMR in response to MNNG. Pretreatment of MNNG-treated RKO7 cells with the caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-fmk or Z-DEVD-fmk prevented PARP-1 cleavage and abrogated apoptosis (Fig. 2B), suggesting that MMR-mediated apoptosis is caspase-dependent. In contrast, RKO6 (MMR-) cells did not undergo apoptosis in response to MNNG. Exposure of MMR+ and MMR- cells to staurosporine caused apoptosis equally in both cells independent of MMR function (Fig. 2A). Thus, RKO6 (MMR-) cells are functionally capable of inducing apoptosis in response to staurosporine and do not lack the capacity to die by this mechanism.

FIGURE 2.

MMR-dependent apoptotic proteolysis of caspase-8, caspase-9, and PARP-1. A, RKO6 and RKO7 cells were treated with MNNG, and apoptotic proteolysis of caspase-8 and caspase-9 as well as PARP-1 was assessed by Western blot analyses. Caspase-9 cleavage (beginning at 48 h) occurred ∼20 h earlier than caspase-8 cleavage, initially observed at 72 h. MNNG-treated RKO6 cells showed no apoptotic proteolyses. B, pretreatment with the caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-fmk (20 μm) or Z-DEVD-fmk (50 μm) abrogated PARP-1 proteolytic cleavage induced by 10 μm MNNG treatment. GAPDH served as a loading control. Arrows indicate activating proteolytic cleavage fragments for caspase-9 (35 kDa), caspase-8 (43 kDa), and PARP-1 (89 kDa). UT, untreated.

Abrogating p53 Function Does Not Affect MMR-dependent Apoptosis—Our laboratory was the first to report differential MMR-dependent stabilization of p53 in cells after 6-TG or IR treatment, and we hypothesized that MMR-dependent cell death and lethality may be p53-dependent (14). We confirmed differential p53 stabilization and phosphorylation (Ser15) in RKO7 (MMR+) versus RKO6 (MMR-) cells in response to MNNG (Fig. 3A), a signaling pathway that would be consistent with the activation of ATM, ATR, or DNA-dependent protein kinase (33–36). Furthermore, significant increases in Bax and p21 expression, known downstream p53 target genes, were observed in RKO7 cells in a prolonged manner compared with transient responses in RKO6 cells (Fig. 3A). As with G2 arrest responses (see Fig. 2 in the accompanying article) (46), RKO6 cells responded initially to MNNG by stabilizing and phosphorylating p53 (Ser15) from 4–12 h, with accompanying minor increases in p21 and Bax; however, the responses rapidly declined as noted (14). Thus, elevated transcriptionally functional p53 levels may be involved in MMR-dependent apoptosis after MNNG exposure. To examine its role in MMR signaling, we functionally inactivated p53 using several different methods in MMR- versus MMR+ RKO cells. p53 was functionally inactivated in RKO cells by E6 expression or stable shRNA-mediated p53 knockdown. E6-expressing RKO7 clones (i.e. B2, B4, B5, and B9) were isolated and expressed significantly less p53 protein compare with vector alone RKO7 (MMR+) cells (Fig. 3B). RKO7 cells that expressed E6 and were functionally depleted of p53 protein levels showed similar levels of apoptosis as vector alone containing RKO7 cells in response to MNNG (Fig. 3B). In contrast, RKO6 cells expressing or lacking E6 did not elicit apoptosis after MNNG exposure. Expression of E6 in HCT116 3-6 cells did not affect MNNG-induced apoptosis (Fig. 2A and supplemental Fig. 2).

FIGURE 3.

Functional abrogation of p53 does not affect MMR-dependent apoptosis. A, MMR- RKO6 and MMR+ RKO7 were treated as described in the legend to Fig. 1, and Western blot analyses of total p53, phospho-p53 (Ser15), Bax, and p21 were performed. p53 was preferentially stabilized and phosphorylated in MMR+ RKO7 cells. GAPDH levels were monitored for equal loading. UT, untreated. B and C, stable MMR- RKO6 and MMR+ RKO7 clones expressing human papillomavirus E6 or vector alone (B) or infected with lentiviral vectors containing shp53 or shSCR sequences (C) were treated with MNNG (10 μm, 1 h) and analyzed for apoptosis at 72 and 96 h. Survival confirmed that HCT116 3-6 and RKO7 cells were equally sensitive to MNNG regardless of p53 status (supplemental Fig. 4, A and B).

To further confirm that p53 was not required for MMR-mediated apoptosis, we generated stable knocked down p53 using shp53 (Fig. 3C). Stable clones showed no detectable p53 protein levels in either RKO6 or RKO7 cells after stable infection with the shp53 lentiviral vector versus cells infected with the shSCR lentiviral vector (Fig. 3C). When RKO7-shp53 cells were treated with MNNG (10 μm, 1 h), apoptosis occurred at 72 and 96 h with similar kinetics, and the extent of cell death observed was not statistically different from apoptosis in MNNG-treated RKO7-shSCR cells. Low levels of apoptosis were observed in both RKO6-shp53 and RKO6-shSCR cells (Fig. 3C), with no statistical differences noted. The same results were also observed upon stable expression of dominant-negative p53 (also noted as DD1) clones (Fig. 2B and supplemental Fig. 3).

To confirm loss of functional p53 in the cells described above, we treated human papillomavirus E6-, shp53-, and dominant-negative p53-expressing stable RKO cells with IR (8 Gy) and noted significant loss of G1 arrest responses with respect to vector alone or shSCR counterparts (Fig. 3 and supplemental Fig. 4). Loss of functional p53 in cells was also accompanied by subsequent loss of MNNG-induced Bax expression (Fig. 3 and supplemental Fig. 5). Finally, loss of p53 function in MMR+ HCT116 or RKO cells did not affect the survival of cells exposed to various MNNG doses (see Fig. 5, A and B, and supplemental Fig. 6) or MNNG-induced MMR-dependent G2 arrest responses in asynchronous or synchronized cells (supplemental Fig. 5, C and D). Collectively, these data strongly suggest that MMR-dependent cell death and G2 arrest responses are not mediated by p53.

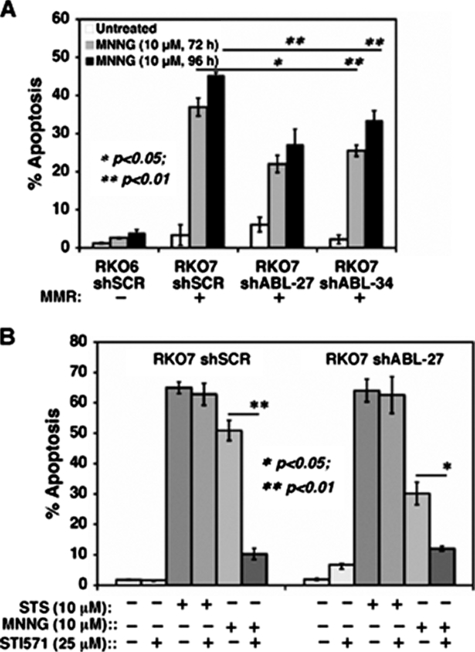

FIGURE 5.

Pharmacological or shABL inhibition dramatically decreases MMR-dependent apoptosis after MNNG exposure. A, RKO6-shSCR, RKO7-shSCR, RKO7-shABL-27, and RKO7-shABL-34 clones were exposed to MNNG (10 μm, 1 h), and apoptosis was monitored at 72 and 96 h. Specific knockdown of p73α decreased apoptosis. B, mock-, MNNG (10 μm, 1 h)-, or staurosporine (STS;10 μm, 24 h)-treated RKO7-shSCR versus RKO7-shABL-27 cells were analyzed for apoptosis. Half of the cells were pretreated with STI571 (25 μm, 2 h) prior to MNNG treatment. RKO7-shABL-27 knockdown cells were more resistant to apoptosis than RKO7-shSCR cells. Both cells were sensitive to staurosporine. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

Enhanced p73α Stabilization in MMR+ Cells after MNNG Treatment—A role for p73 in stimulating apoptosis after cisplatin exposure was reported (23–25). We therefore examined p73 expression in RKO7 (MMR+) versus RKO6 (MMR-) cells before and after MNNG exposure (10 μm, 1 h). Increases in p73α (but not p73β) expression were noted at 24–48 h in both RKO7 (MMR+) and RKO6 (MMR-) cells after MNNG treatment (Fig. 4, A and B). However, in a response apparently concomitant with p53 stabilization and G2 arrest responses, p73α (but not p73β) levels were elevated to a greater extent and in a more prolonged manner (at least to 72 h) (Fig. 4, A and B) in MMR+ RKO7 compared with MMR- RKO6 cells. Interestingly, we noted the consistent loss of p73α and p73β in RKO6 cells over time after MNNG treatment. Loss of p73 isoforms was consistent with a lack of apoptosis and may be indicative of loss of c-Abl activity (see below), growth arrest, or cell death (senescence) in RKO6 cells after MNNG treatment.

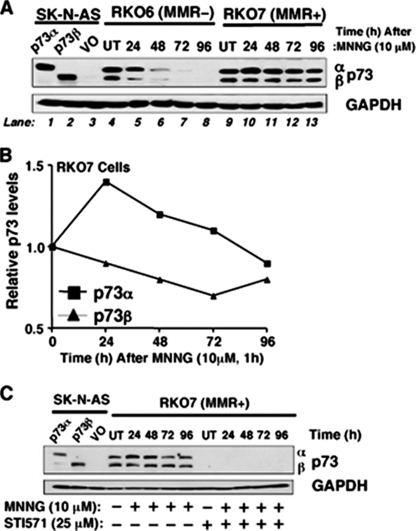

FIGURE 4.

MMR-dependent stabilization of p73α after MNNG exposure. A, MMR- RKO6 and MMR+ RKO7 cells were exposed to MNNG (10 μm, 1 h), and the kinetics of p73 expression was examined by Western blot analyses. VO, vector only; UT, untreated. B, p73α levels were preferentially stabilized in RKO7 (MMR+) cells after MNNG treatment. Relative p73α and p73β levels before and after MNNG treatment were quantified from Western blots using NIH Image J software. C, c-Abl tyrosine kinase inhibition by STI571 (Gleevec™) abrogated p73α and p73β levels with or without MNNG (10 μm, 1 h). RKO6 and RKO7 cells were pretreated with a nontoxic dose of STI571 (25 μm, 2 h) and exposed to MNNG (10 μm, 1 h), and p73α or p73β expression was examined by Western blot assays. p73α/β-deficient human SK-N-AS neuroblastoma cells transfected with exogenous p73α or p73β were used as controls for expression. GAPDH levels were monitored for loading.

Given the role of c-Abl in MMR-dependent G2 arrest and lethality (46), we examined the effect of STI571 (Gleevec™), a c-Abl tyrosine kinase inhibitor, on MMR-dependent p73α stabilization and apoptosis. Interestingly, MNNG-induced MMR-dependent p73α increases, as well as basal p73β expression, were blocked by STI571 (Fig. 4C). Extracts from SK-N-AS cells that lack p73 expression and from cells separately expressing p73α or p73β were used to define the locations of p73 isoforms (Fig. 4, A and C). Collectively, these data strongly suggest that p73α expression is MMR-dependent and regulated by c-Abl activation after MNNG exposure.

MMR-dependent Apoptosis Is Dependent on c-Abl Signaling—We stably knocked down c-Abl expression in RKO6 and RKO7 cells using retrovirus-mediated shRNA expression (see Fig. 5A in the accompanying article) (46). Significantly diminished c-Abl protein levels and enzymatic activities in response to cisplatin or MNNG were noted in c-Abl knockdown cells versus cells expressing nonsense (or scrambled) shRNA (46). Consistent with its abrogation of survival and G2 arrest responses (46), apoptosis was partially but significantly (p < 0.01) decreased in RKO7-c-Abl knockdown clones (shABL-27 and shABL-34) compared with scrambled shRNA-expressing RKO7-shSCR cells (Fig. 5A). At 72 h, MNNG-exposed MMR+ RKO7-shSCR cells exhibited 37 ± 2% apoptosis compared with 22 ± 2% and 26 ± 1% apoptosis in RKO7-shABL-27 and RKO7-shABL-34 cells, respectively (Fig. 5A). Thus, c-Abl down-regulation significantly abrogated MMR-dependent apoptotic responses to MNNG. In contrast, c-Abl knockdown in RKO6 cells did not appreciably affect apoptosis versus RKO6-shSCR cells after MNNG exposure (data not shown).

We then exposed MMR+ RKO7-shSCR versus RKO7-shABL-27 knockdown cells to STI571 (Gleevec™). STI571 significantly decreased apoptosis (Fig. 5B) and increased survival (46) of MNNG-exposed RKO7 cells. Addition of STI571 did not significantly affect staurosporine-induced apoptosis in RKO7 or RKO7-shABL-27 knockdown cells (Fig. 5B).

Abrogating p73α Function Prevents MMR-dependent Apoptosis—p73α is a known downstream gene regulated by c-Abl (23–25). To determine whether MMR-dependent increases in p73α expression (Fig. 4, A and C) were dependent on c-Abl, we examined its expression in RKO7-shABL clones before and after MNNG treatment (10 μm, 1 h). p73α (but not p73β) levels decreased in RKO7-shABL versus RKO7-shSCR cells after MNNG exposure (compare p73α increases at 72 h post-MNNG treatment in shSCR cells (Fig. 6A, lane 5) with lower levels in shABL-27 and shABL-34 cells (lanes 8 and 11, respectively). These data strongly suggest that MMR-dependent c-Abl-mediated signaling in response to MNNG acts to control p73α stabilization and levels.

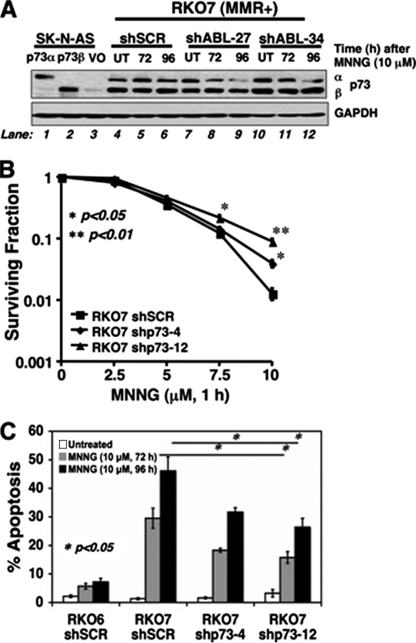

FIGURE 6.

c-Abl-mediated stabilization of p73α regulates apoptosis in MMR+ cells after MNNG exposure. A, RKO7-shSCR, RKO7-shABL-27, and RKO7-shABL-34 clones were generated and exposed to MNNG (10 μm, 1 h), and p73α and p73β levels were analyzed before and after MNNG treatment (10 μm, 1 h). p73α/β-deficient SK-N-AS cells and p73α and p73β stable transfectants were analyzed along with GAPDH levels for loading. VO, vector only; UT, untreated. B, RKO7-shSCR, RKO7-shp73-4, and RKO7-shp73-12 cells were treated with or without various MNNG doses (μm, 1 h), and changes in survival were noted. Loss of p73α levels in RKO7-shp73-4 and RKO7-shp73-12 clones resulted in a significant reduction of MNNG-induced lethality. C, RKO6-shSCR, RKO7-shSCR, RKO7-shp73-4, and RKO7-shp73-12 clones were exposed to MNNG (10 μm, 1 h) and assessed for apoptosis. Specific knockdown of p73α decreased apoptosis. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

To explore the functional role of p73α in MMR-dependent apoptosis and survival in response to MNNG, we generated knockdown cells using shRNA lentivirus specific for p73α (shp73) (46). Silencing p73α levels in all clones examined (shp73-4 and shp73-12 clones shown) (Fig. 6B) significantly abrogated MMR-dependent lethality at MNNG doses ≥7.5 μm, as measured by survival assays (Fig. 6B). Concomitantly, MNNG-induced apoptosis was also significantly lower in RKO7-shp73 versus RKO7-shSCR cells. RKO7-shSCR cells exposed to MNNG (10 μm, 1 h) resulted in 47 ± 4% apoptosis at 96 h (Fig. 6C), levels equivalent to those in parental RKO7 cells (Fig. 1B). In contrast, MNNG-exposed RKO7-shp73 clones shp73-4 and shp73-12 exhibited 32 ± 1% and 26 ± 3% apoptosis, respectively (Fig. 6C). Thus, MMR-dependent c-Abl/p73α signaling mediated apoptosis (Fig. 6C) and survival (Fig. 6B) in response to MNNG. However, MMR-dependent G2 arrest responses were not dependent on p73α function (46).

GADD45α Regulates MMR-dependent Apoptosis and Lethality—Because we noticed MMR-dependent GADD45α induction in cells after 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine treatment, we hypothesized that MMR-dependent cell death and lethality may be regulated by GADD45α (29). To examine the role of GADD45α in MMR-dependent apoptosis and survival responses to MNNG, we generated knockdown cells using shRNA lentivirus specific for GADD45α (shGADD45α) (46). Silencing GADD45α levels in all clones (shGADD45α-2 and shGADD45α-3 clones shown) (Fig. 7A) significantly abrogated MMR-dependent lethality at MNNG doses ≥10 μm, as measured by survival assays (Fig. 7A). Concomitantly, MNNG-induced apoptosis was also significantly lower in RKO7-shGADD45α versus RKO7-shSCR cells. RKO7-shSCR cells exposed to MNNG (10 μm, 1 h) resulted in 47 ± 2% apoptosis at 96 h (Fig. 7B), levels equivalent to those in RKO7 parental cells (Fig. 1B). In contrast, MNNG-exposed RKO7-shGADD45α clones shGADD45α-2 and shGADD45α-3 exhibited 34 ± 2% and 35 ± 3% apoptosis, respectively (Fig. 7B). We noticed hMLH1/c-Abl-dependent p73α and shGADD45α regulation, but did not find any link between p73α and shGADD45α. We also found the same MMR-dependent c-Abl/shGADD45α signaling-mediated apoptosis and survival response in murine wild-type Gadd45α (MEF1-1, Gadd45α+/+) versus Gadd45α knock-out (MEF11-1, Gadd45α-/-) cells (supplemental Fig. 6). Thus, MMR-dependent c-Abl/GADD45α signaling mediated apoptosis (Fig. 7B) and survival (Fig. 7A) in response to MNNG.

FIGURE 7.

c-Abl-mediated stabilization of GADD45α regulates apoptosis in MMR+ cells after MNNG treatment. A, RKO7-shSCR, RKO7-shGADD45α-2, and RKO7-shGADD45α-3 clones were treated with or without various MNNG doses (μm, 1 h), and changes in survival were noted. B, RKO6-shSCR, RKO7-shSCR, RKO7-shGADD45α-2, and RKO7-shGADD45α-3 clones were exposed to MNNG (10 μm, 1 h) and assessed for apoptosis. Specific knockdown of GADD45α decreased apoptosis. *, p < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

The major goal of this and our accompanying study (46) was to elucidate the mechanism by which retrograde MMR-dependent signaling induces G2 arrest and apoptosis in response to MNNG-induced DNA lesions. In light of prior reports using cisplatin (23–25), our studies using MNNG strongly suggest a common signaling pathway involving hMLH1/c-Abl/GADD45α for G2 arrest and p73α activation and stabilization for apoptosis (Fig. 8). Our data strongly suggest that 6-TG responses involve identical signaling pathways (data not shown), rejecting the theory that signaling from different lesions detected by MMR might be agent-specific.

FIGURE 8.

hMLH1/c-Abl/p73α/GADD45α signaling controls G2 arrest, apoptosis, and survival. Shown is the MMR detection of O6-methylguanine (O6-MeG) DNA lesions created after MNNG signals through c-Abl to increase p73α and GADD45α expression. c-Abl/GADD45α controls G2 arrest, apoptosis, and survival, whereas c-Abl/p73α is needed in apoptosis and survival.

Using genetic and pharmacological approaches, we have shown that exposure of cells to MNNG induced MMR-dependent (i) apoptosis via intrinsic apoptotic signaling, (ii) cell death processes that are not dependent on functional p53, and (iii) apoptosis signaled through the hMLH1/c-Abl/p73α or hMLH1/c-Abl/GADD45α pathway. Our data supply the first evidence that MMR-dependent apoptosis and G2 arrest can be uncoupled. Down-regulation of either c-Abl or GADD45α blocked both apoptosis and G2 arrest stimulated by MMR, whereas p73α knockdown affected only apoptosis, suggesting that MMR specifically detects MNNG-induced DNA lesions and signals directly to c-Abl, as confirmed in the accompanying article (46). c-Abl activation appears to be downstream from hMLH1 but upstream from p73α and GADD45α expression because shRNA-mediated knockdown of this tyrosine kinase or addition of STI571 (Gleevec™) dramatically decreased expression of GADD45α and p73α, two proteins whose activities appear to regulate apoptosis as well as cell lethality.

For the first time, we have shown that MMR-dependent apoptosis occurs by delayed activities (after 48 h) of the intrinsic pathway. Caspase-9 was activated significantly earlier (∼20 h) than caspase-8. Caspase-9 is specifically activated by mitochondrial catastrophe, release of cytochrome c, and engagement of Apaf-1 (10). Its activation through hMLH1/c-Abl/p73α/GADD45α signaling must ultimately lead to expression of pro-apoptotic factors that mediate mitochondrial permeability transition.

Surprisingly, p53 stabilization and function are irrelevant to G2 arrest, apoptosis, or survival in RKO or HCT116 cells (Fig. 3 and supplemental Figs. 2–5). We anticipated that MMR-dependent stabilization of p53 (Fig. 3A) (14) would mediate apoptosis. Our data definitely show that p53 does not play a functional role in any MMR-dependent signaling responses triggered by detection of MNNG-induced DNA lesions. The p53 tumor suppressor has been implicated in several critical damage-induced pathways, including p21-mediated G1 arrest, Bax induction, and pro-apoptotic protein expression. p53 induction also mediates GADD45α-induced DNA repair and p21- and/or p16-mediated cellular senescence (37–39). Interestingly, we concomitantly noted p21 and Bax protein accumulation in MNNG-treated MMR+ cells, consistent with downstream transactivation by p53. It is surprising that such responses play no role in cell death because a major function of Bax and other known downstream pro-apoptotic p53-responsive genes (e.g. PUMA) are reported to translocate to mitochondria and to mediate cytochrome c and Apaf-1 release, activating Apaf-1/caspase-9 (40). MMR-dependent MNNG-induced G2 arrest was not affected by abrogation of ATM, ATR, Chk1, or Chk2. Thus, detection of MNNG-induced DNA lesions by MMR leads to phosphorylation, stabilization, and transactivation of p53; however, its functions are not required for apoptosis and G2 arrest. Similar conclusions were drawn using 6-TG or IR (14).

The exact mechanism and functional significance of MMR-dependent phosphorylation and stabilization of p53 after MNNG exposure are unknown. We suspect that prolonged p53 response in MMR+ cells plays a major role in the control of subsequent G1 arrest. Cells that escape G2 arrest after MNNG exposure would be halted in G1 before proceeding through another round of DNA synthesis, avoiding further amplification of mutations. DNA damage signaling is a major mechanism by which p53 becomes functionally activated (41). The exact mechanism by which p53 becomes activated by hMLH1/c-Abl signaling remains unknown. The majority of DNA lesion sensors in the cell (i.e. DNA-dependent protein kinase, ATM, and ATR) are serine/threonine kinases that target p53 for phosphorylation and act to promote tetramerization (34, 36). The mechanisms by which c-Abl might cross-talk through such enzymes is currently being explored.

Because p73α, a p53 homolog, is activated and induced apoptosis in response to cisplatin (23–25), we examined and noted an involvement of MMR-specific p73α stabilization in apoptosis after MNNG treatment. Significant decreases in apoptosis and survival increases were noted when p73α was silenced (Fig. 6). These data strongly support the hypothesis that p73α plays a major role in MMR-dependent MNNG-induced apoptosis. A prior study showed enhanced p73α stabilization after cisplatin treatment in hPMS2-corrected cells, suggesting that hPMS2 and p73α may interact (26). Our data suggest that c-Abl activation is upstream from p73α stabilization because STI571 and c-Abl knockdown prevented p73α stabilization and apoptosis. These data are consistent with the observation that c-Abl can phosphorylate and stabilize p73α in response to cisplatin (25, 42). Indeed, STI571 pretreatment of cells abrogates MMR-dependent apoptosis, long-term survival, and G2 arrest induced by MNNG (46). Because STI571 can inhibit other tyrosine kinases (e.g. c-Kit and platelet-derived growth factor receptor), we used genetic silencing by shRNA to knock down c-Abl expression. Stabilization of p73α (but not p73β) was significantly decreased in response to functional c-Abl knockdown in MMR-proficient cells. c-Abl knockdown using shABL or use of STI571 (46) prevented MMR-inducible p73α and GADD45α protein levels, but we did not observe that either p73α or GADD45α was changed in shGADD45α and shp73 knockdown clones (data not shown). Together with expression and functional analyses of MMR-dependent GADD45α responses (see Fig. 6A in the accompanying article) (46), our data support the theory that MMR-dependent detection and signaling of DNA lesions trigger hMLH1/c-Abl/p73α and hMLH1/c-Abl/GADD45α signaling to induce cell death (Fig. 8). Our data do not suggest a functional role for p73β in MMR-dependent apoptosis, even though this protein has been linked to apoptosis in non-small cell lung cancer cells induced by other agents (43).

MNNG-induced cell death does not always occur through apoptosis. In MMR+ RKO7 cells, apoptosis does appear to be the predominant means of cell death and loss of long-term survival. However, we noted that in MMR-proficient HCT116 3-6 colon cancer cells, only ∼20–30% apoptosis was noted, even though >99.9% lethality was induced by high dose MNNG exposure. These data suggest that other cell death mechanisms function after MNNG exposure. A recent study reported that autophagy (a process whereby cells catabolize intracellular damaged organelles for turnover) may play a role in 6-TG-induced sensitivity in HCT116 cells (44). Thus, it is possible that HCT116 cells that express low levels of Bax die by alternative pathways such as autophagy or replicative senescence after MNNG treatment. The mechanism of cell death in MNNG-exposed MMR- RKO cells has yet to be defined.

In general, MMR triggers apoptosis in response to MNNG-induced DNA lesions, which, along with long-term survival, is completely abrogated by the c-Abl kinase inhibitor STI571 (Gleevec™). Recently, STI571 also abrogated cell death responses following oxidative stress, presumably by inhibiting c-Abl tyrosine kinase activity (45). Our data strongly suggest that Gleevec™ may be ill suited in conjunction with temozolomide or cisplatin or other clinically used alkylating agents for efficacious cancer therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. James K. V. Willson, George Stark, Lindsey Mayo, Marty Veigl, Stanton Gerson, and David Sedwick for helpful discussions.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant CA102792-01 from NCI (to D. A. B.). This work was also supported by Grant DE-FG022179-16-18 from the Department of Energy. This is Manuscript CSCN 020 from the Program in Cell Stress and Cancer Nanomedicine, Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1–6.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: MMR, DNA mismatch repair; MNNG, N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine; h, human; 6-TG, 6-thioguanine; shRNA, short hairpin RNA; shSCR, scrambled shRNA; shp53, p53 shRNA; shABL, c-Abl shRNA; shp73, p73α shRNA; shGADD45α, GADD45α shRNA; Z, benzyloxycarbonyl; fmk, fluoromethyl ketone; TUNEL, terminal deoxynucleotidyl-transferase dUTP nick end labeling; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

References

- 1.Jiricny, J. (2006) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7 335-346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hawn, M. T., Umar, A., Carethers, J. M., Marra, G., Kunkel, T. A., Boland, C. R., and Koi, M. (1995) Cancer Res. 55 3721-3725 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kat, A., Thilly, W. G., Fang, W., Longley, M. J., Li, G., and Modrich, P. (1993) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90 6424-6428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyers, M., Hwang, A., Wagner, M. W., and Boothman, D. A. (2004) Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 44 249-264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fishel, R., Lescoe, M. K., Rao, M. R. S., Copeland, N. G., Jenkins, N. A., Garber, J., Kane, M., and Kolodner, R. (1993) Cell 75 1027-1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bronner, C. E., Baker, S. M., Morrison, P. T., Warren, G., Smith, L. G., Lescoe, M. K., Kane, M., Earabino, C., Lipford, J., Lindblom, A., Tannergard, P., Bollag, R. J., Godwin, A. R., Ward, D. C., Nordenskjld, M., Fishel, R., Kolodner, R., and Liskay, R. M. (1994) Nature 368 258-261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim, H., Kim, Y. H., Kim, S. E., Kim, N.-G., Noh, S. H., and Kim, H. (2003) J. Pathol. 200 23-31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li, L. S., Kim, N.-G., Kim, S. H., Park, C., Kim, H., Kang, H. J., Koh, K. H., Kim, S. N., Kim, W. H., Kim, N. K., and Kim, H. (2003) Am J. Pathol. 163 1429-1436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karran, P. (2001) Carcinogenesis 22 1931-1937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bao, Q., and Shi, Y. (2007) Cell Death Differ. 14 56-65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wajant, H. (2002) Science 296 1635-1636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patenaude, A., Deschesnes, R. G., Rousseau, J. L. C., Petitclerc, E., Lacroix, J., Cote, M.-F., and C.-Gaudreault, R. (2007) Cancer Res. 67 2306-2316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerson, S. L. (2002) J. Clin. Oncol. 20 2388-2399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis, T. W., Patten, C. W.-V., Meyers, M., Kunugi, K. A., Cuthill, S., Reznikoff, C., Garces, C., Boland, C. R., Kinsella, T. J., Fishel, R., and Boothman, D. A. (1998) Cancer Res. 58 767-778 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stojic, L., Mojas, N., Cejka, P., di Pietro, M., Ferrari, S., Marra, G., and Jiricny, J. (2004) Genes Dev. 18 1331-1344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schaetzlein, S., Kodandaramireddy, N. R., Ju, Z., Lechel, A., Stepczynska, A., Lilli, D. R., Clark, A. B., Rudolph, C., Kuhnel, F., Wei, K., Schlegelberger, B., Schirmacher, P., Kunkel, T. A., Greenberg, R. A., Edelmann, W., and Rudolph, K. L. (2007) Cell 130 863-877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duckett, D. R., Bronstein, S. M., Taya, Y., and Modrich, P. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96 12384-12388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirose, Y., Katayama, M., Stokoe, D., Haas-Kogan, D. A., Berger, M. S., and Pieper, R. O. (2003) Mol. Cell. Biol. 23 8306-8315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshioka, K.-i., Yoshioka, Y., and Hsieh, P. (2006) Mol. Cell 22 501-510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yanamadala, S., and Ljungman, M. (2003) Mol. Cancer Res. 1 747-754 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roos, W. P., and Kaina, B. (2006) Trends Mol. Med. 12 440-450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hickman, M. J., and Samson, L. D. (2004) Mol. Cell 14 105-116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agami, R., Blandino, G., Oren, M., and Shaul, Y. (1999) Nature 399 809-813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gong, J., Costanzo, A., Yang, H.-Q., Melino, G., Kaelin, W. G., Levrero, M., and Wang, J. Y. J. (1999) Nature 399 806-809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yuan, Z.-M., Shioya, H., Ishiko, T., Sun, X., Gu, J., Huang, Y., Lu, H., Kharbanda, S., Weichselbaum, R., and Kufe, D. (1999) Nature 399 814-817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shimodaira, H., Yoshioka-Yamashita, A., Kolodner, R. D., and Wang, J. Y. J. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100 2420-2425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brummelkamp, T. R., Bernards, R., and Agami, R. (2002) Science 296 550-553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hollander, M. C., Sheikh, M. S., Bulavin, D. V., Lundgren, K., Augeri-Henmueller, L., Shehee, R., Molinaro, T. A., Kim, K. E., Tolosa, E., Ashwell, J. D., Rosenberg, M. P., Zhan, Q., Fernandez-Salguero, P. M., Morgan, W. F., Deng, C.-X., and Fornace, A. J. (1999) Nat. Genet. 23 176-184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meyers, M., Wagner, M. W., Hwang, H.-S., Kinsella, T. J., and Boothman, D. A. (2001) Cancer Res. 61 5193-5201 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choi, Y. R., Kim, H., Kang, H. J., Kim, N.-G., Kim, J. J., Park, K.-S., Paik, Y.-K., Kim, H. O., and Kim, H. (2003) Cancer Res. 63 2188-2193 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang, H., Richards, B., Wilson, T., Lloyd, M., Cranston, A., Thorburn, A., Fishel, R., and Meuth, M. (1999) Cancer Res. 59 3021-3027 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yan, T., Berry, S. E., Desai, A. B., and Kinsella, T. J. (2003) Clin. Cancer Res. 9 2327-2334 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burma, S., Kurimasa, A., Xie, G., Taya, Y., Araki, R., Abe, M., Crissman, H. A., Ouyang, H., Li, G. C., and Chen, D. J. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274 17139-17143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Canman, C. E., Lim, D.-S., Cimprich, K. A., Taya, Y., Tamai, K., Sakaguchi, K., Appella, E., Kastan, M. B., and Siliciano, J. D. (1998) Science 281 1677-1679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim, W.-J., Beardsley, D. I., Adamson, A. W., and Brown, K. D. (2005) Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 202 84-98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tibbetts, R. S., Brumbaugh, K. M., Williams, J. M., Sarkaria, J. N., Cliby, W. A., Shieh, S.-Y., Taya, Y., Prives, C., and Abraham, R. T. (1999) Genes Dev. 13 152-157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dimri, G. P. (2005) Cancer Cell 7 505-512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harms, K., Nozell, S., and Chen, X. (2004) CMLS Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 61 822-842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levine, A. J. (1997) Cell 88 323-331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gross, A., McDonnell, J. M., and Korsmeyer, S. J. (1999) Genes Dev. 13 1899-1911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ashcroft, M., Kubbutat, M. H. G., and Vousden, K. H. (1999) Mol. Cell. Biol. 19 1751-1758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsai, K. K. C., and Yuan, Z.-M. (2003) Cancer Res. 63 3418-3424 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nyman, U., Sobczak-Pluta, A., Vlachos, P., Perlmann, T., Zhivotovsky, B., and Joseph, B. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 34159-34169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zeng, X., Yan, T., Schupp, J. E., Seo, Y., and Kinsella, T. J. (2007) Clin. Cancer Res. 13 1315-1321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kumar, S., Mishra, N., Raina, D., Saxena, S., and Kufe, D. (2003) Mol. Pharmacol. 63 276-282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wagner, M. W., Li, L. S., Morales, J. C., Galindo, C. L., Garner, H. R., Bornmann, W. G., and Boothman, D. A. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283 21382-21393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.