Abstract

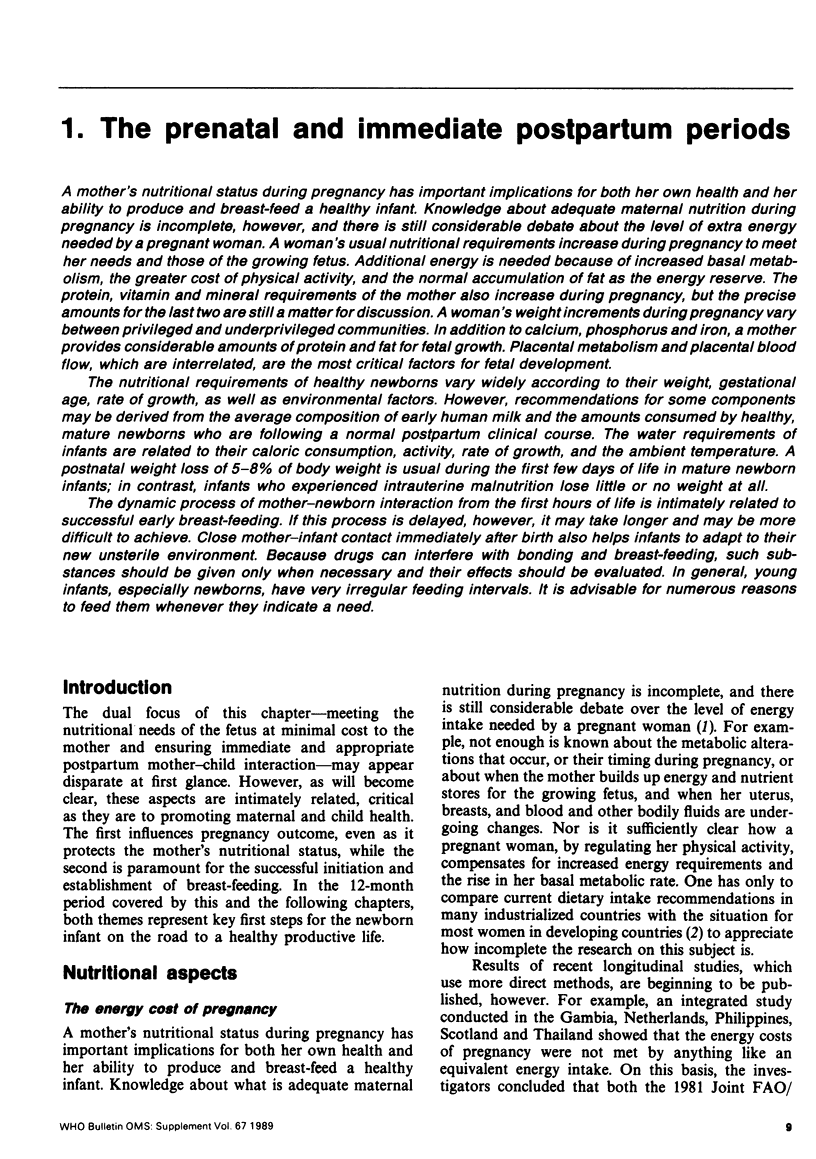

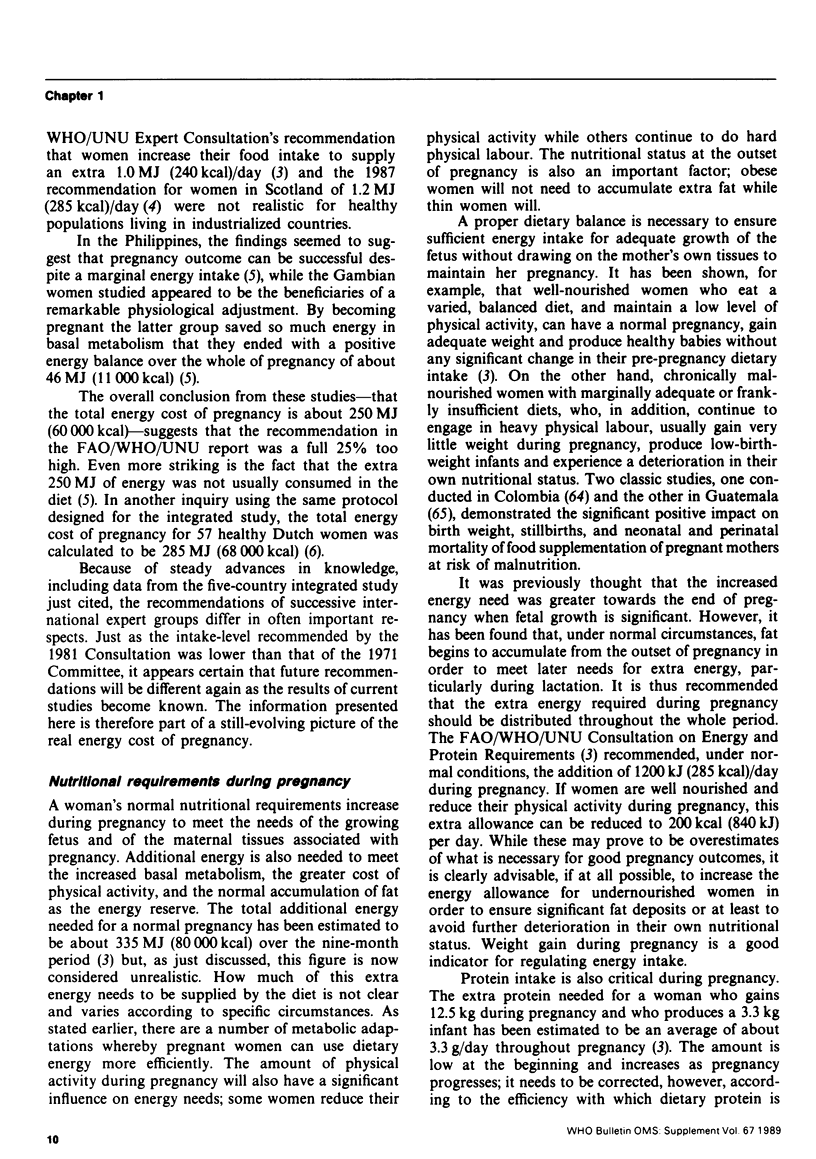

A mother's nutritional status during pregnancy has important implications for both her own health and her ability to produce and breast-feed a healthy infant. Knowledge about adequate maternal nutrition during pregnancy is incomplete, however, and there is still considerable debate about the level of extra energy needed by a pregnant woman. A woman's usual nutritional requirements increase during pregnancy to meet her needs and those of the growing fetus. Additional energy is needed because of increased basal metabolism, the greater cost of physical activity, and the normal accumulation of fat as the energy reserve. The protein, vitamin and mineral requirements of the mother also increase during pregnancy, but the precise amounts for the last two are still a matter for discussion. A woman's weight increments during pregnancy vary between privileged and underprivileged communities. In addition to calcium, phosphorus and iron, a mother provides considerable amounts of protein and fat for fetal growth. Placental metabolism and placental blood flow, which are interrelated, are the most critical factors for fetal development.

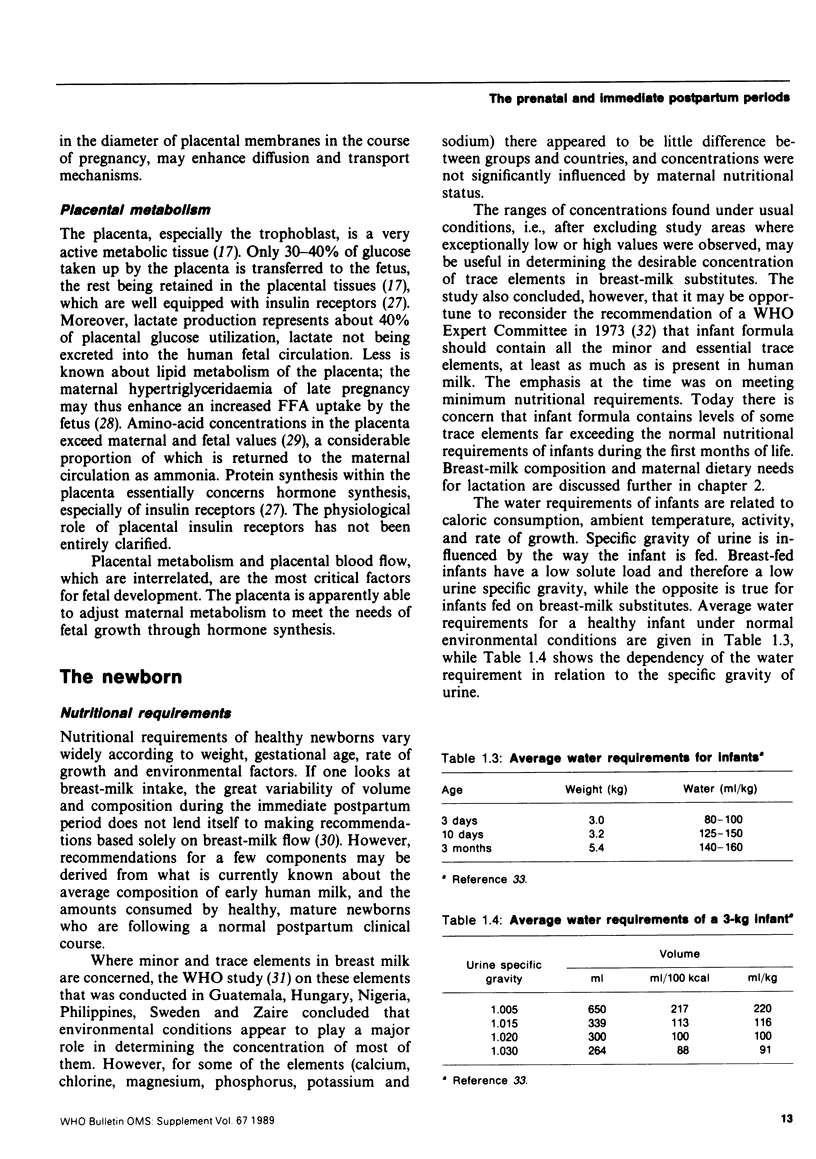

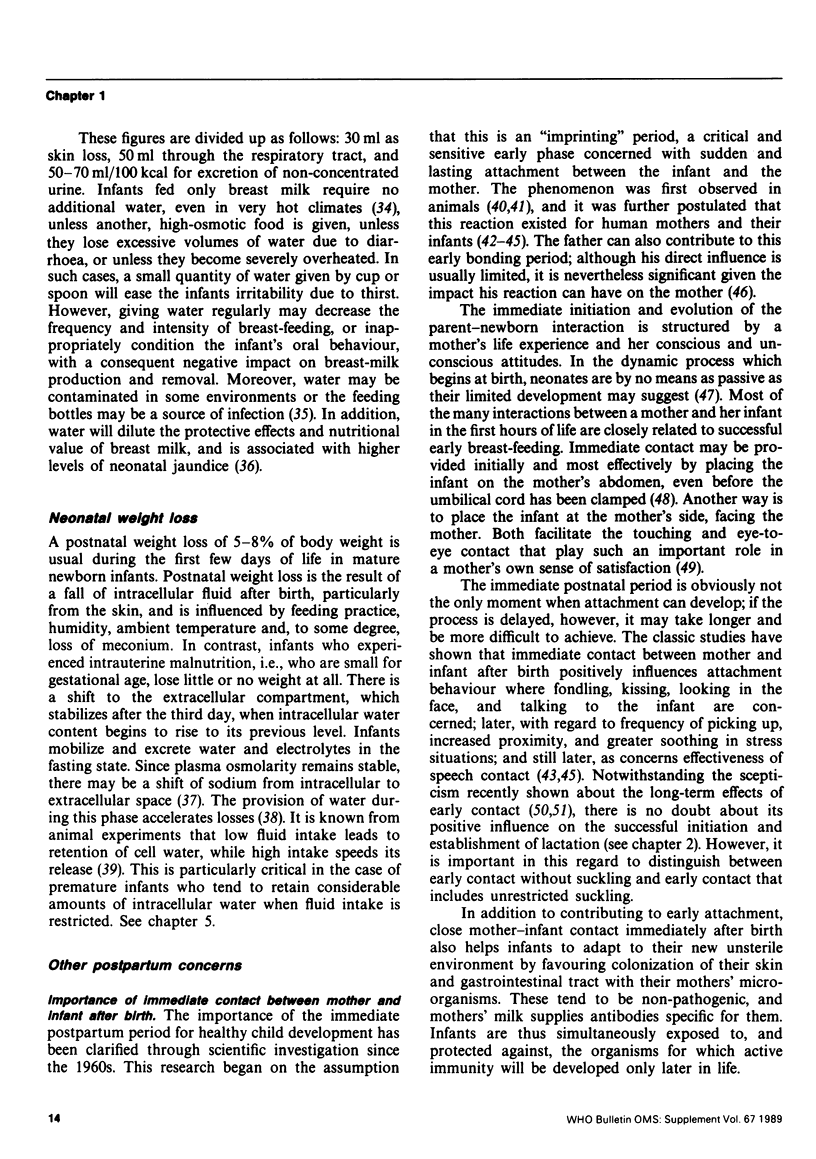

The nutritional requirements of healthy newborns vary widely according to their weight, gestational age, rate of growth, as well as environmental factors. However, recommendations for some components may be derived from the average composition of early human milk and the amounts consumed by healthy, mature newborns who are following a normal postpartum clinical course. The water requirements of infants are related to their caloric consumption, activity, rate of growth, and the ambient temperature. A postnatal weight loss of 5-8% of body weight is usual during the first few days of life in mature newborn infants; in contrast, infants who experienced intrauterine malnutrition lose little or no weight at all.

The dynamic process of mother—newborn interaction from the first hours of life is intimately related to successful early breast-feeding. If this process is delayed, however, it may take longer and may be more difficult to achieve. Close mother—infant contact immediately after birth also helps infants to adapt to their new unsterile environment. Because drugs can interfere with bonding and breast-feeding, such substances should be given only when necessary and their effects should be evaluated. In general, young infants, especially newborns, have very irregular feeding intervals. It is advisable for numerous reasons to feed them whenever they indicate a need.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Almroth S. G. Water requirements of breast-fed infants in a hot climate. Am J Clin Nutr. 1978 Jul;31(7):1154–1157. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/31.7.1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach K. G., Gartner L. M. Breastfeeding and human milk: their association with jaundice in the neonate. Clin Perinatol. 1987 Mar;14(1):89–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia F. C., Meschia G. Principal substrates of fetal metabolism. Physiol Rev. 1978 Apr;58(2):499–527. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1978.58.2.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgstedt A. D., Rosen M. G. Medication during labor correlated with behavior and EEG of the newborn. Am J Dis Child. 1968 Jan;115(1):21–24. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1968.02100010023004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll M. J., Young M. The relationship between placental protein synthesis and transfer of amino acids. Biochem J. 1983 Jan 15;210(1):99–105. doi: 10.1042/bj2100099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter D. M., Avery M. E. Paradoxical reduction in tissue hydration with weight gain in neonatal rabbit pups. Pediatr Res. 1980 Oct;14(10):1122–1126. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198010000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durnin J. V. Energy requirements of pregnancy. An integrated study in five countries: background and methods. Lancet. 1987 Oct 17;2(8564):895–896. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91382-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser C. M. Selected perinatal procedures. Scientific basis for use and psycho-social effects. A literature review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand Suppl. 1983;117:1–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg N. M., Adams E. Supplementary water for breast-fed babies in a hot and dry climate--not really a necessity. Arch Dis Child. 1983 Jan;58(1):73–74. doi: 10.1136/adc.58.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grünberger W., Leodolter S., Parschalk O. Schwangerschafts-Hypotension und "Fetal outcome". Fortschr Med. 1979 Jan 25;97(4):141–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HANSEN J. D., SMITH C. A. Effects of withholding fluid in the immediate postnatal period. Pediatrics. 1953 Aug;12(2):99–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUGHES J. G., HILL F. S., GREEN C. R., DAVIS B. C. Electroencephalography of the newborn. V. Brain potentials of babies born of mothers given meperidine hydrochloride (demerol hydrochloride), vinbarbital sodium (delvinal sodium) or morphine. Am J Dis Child. 1950 Jun;79(6):998–1007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hales D. J., Lozoff B., Sosa R., Kennell J. H. Defining the limits of the maternal sensitive period. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1977 Aug;19(4):454–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1977.tb07938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay W. W., Jr, Sparks J. W., Wilkening R. B., Battaglia F. C., Meschia G. Fetal glucose uptake and utilization as functions of maternal glucose concentration. Am J Physiol. 1984 Mar;246(3 Pt 1):E237–E242. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1984.246.3.E237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill E. P., Longo L. D. Dynamics of maternal-fetal nutrient transfer. Fed Proc. 1980 Feb;39(2):239–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaus M. H., Jerauld R., Kreger N. C., McAlpine W., Steffa M., Kennel J. H. Maternal attachment. Importance of the first post-partum days. N Engl J Med. 1972 Mar 2;286(9):460–463. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197203022860904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaus M. H., Kennell J. H., Plumb N., Zuehlke S. Human maternal behavior at the first contact with her young. Pediatrics. 1970 Aug;46(2):187–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kron R. E., Stein M., Goddard K. E. Newborn sucking behavior affected by obstetric sedation. Pediatrics. 1966 Jun;37(6):1012–1016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kübler W. Ernährung während der Schwangerschaft. Gynakologe. 1987 Jun;20(2):83–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maclaurin J. C. Changes in body water distribution during the first two weeks of life. Arch Dis Child. 1966 Jun;41(217):286–291. doi: 10.1136/adc.41.217.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro H. N., Pilistine S. J., Fant M. E. The placenta in nutrition. Annu Rev Nutr. 1983;3:97–124. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.03.070183.000525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner B. I. Insulin receptors in human and animal placental tissue. Diabetes. 1974 Mar;23(3):209–217. doi: 10.2337/diab.23.3.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosa R., Kennell J. H., Klaus M., Urrutia J. J. The effect of early mother-infant contact on breast feeding, infection and growth. Ciba Found Symp. 1976;(45):179–193. doi: 10.1002/9780470720271.ch11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuazon M. A., van Raaij J. M., Hautvast J. G., Barba C. V. Energy requirements of pregnancy in the Philippines. Lancet. 1987 Nov 14;2(8568):1129–1131. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91555-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young M. Placental factors and fetal nutrition. Am J Clin Nutr. 1981 Apr;34(Suppl 4):738–743. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/34.4.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]