Abstract

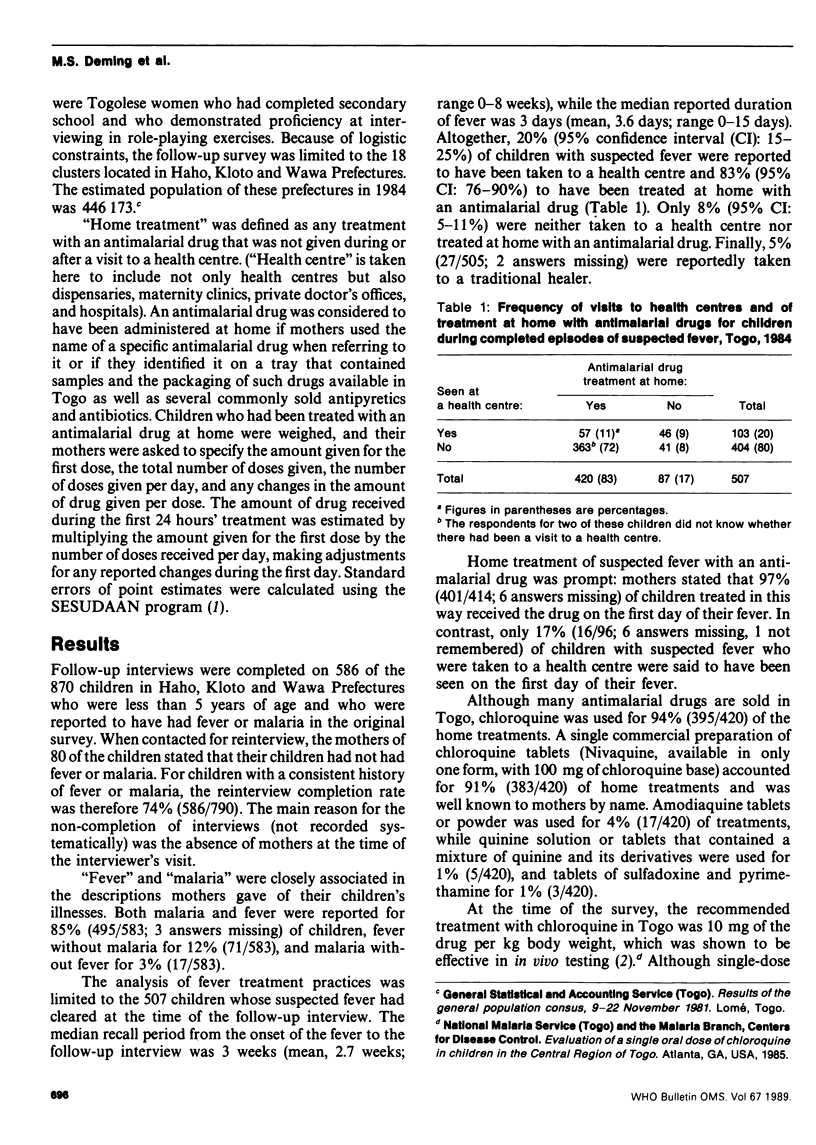

In Togo, the principal strategy for preventing death from malaria in children is prompt treatment of fever with antimalarial drugs. A household survey was conducted in a rural area of south-central Togo in which information was collected from mothers on the treatment received by 507 children under 5 years of age who, according to their mothers, had recently had fever. Altogether, 20% of the children (95% confidence interval (Cl): 15-25%) were seen at a health centre during their illness, while 83% (95% Cl: 76-90%) were treated at home with an antimalarial drug. Of the children in the latter group, 97% received the drug on the first day of fever. In contrast, only 17% of children who attended a health centre were seen on the first day of their fever. Chloroquine, usually obtained from a street or market vendor, was used for 94% of the treatments given at home. Based on children's weights and treatment histories provided by their mothers, the median total dosage of chloroquine given at home was 12.8 mg per kg body weight--more than that recommended and known to be fully effective in Togo at the time of the survey (10 mg per kg) and less than the total dosage recommended at present (25 mg per kg). The dosage administered was considered to be inadequate for 70% of home treatments, because less than 10 mg per kg was given during the first 24 hours of treatment. In the study area, parents were the main providers of antimalarial drug treatment to children with fever and need guidance on the correct dosage of chloroquine.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Dabis F., Breman J. G., Roisin A. J., Haba F. Monitoring selective components of primary health care: methodology and community assessment of vaccination, diarrhoea, and malaria practices in Conakry, Guinea. ACSI-CCCD team. Bull World Health Organ. 1989;67(6):675–684. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood B. M., Greenwood A. M., Bradley A. K., Snow R. W., Byass P., Hayes R. J., N'Jie A. B. Comparison of two strategies for control of malaria within a primary health care programme in the Gambia. Lancet. 1988 May 21;1(8595):1121–1127. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)91949-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood B. M., Greenwood A. M., Bradley A. K., Tulloch S., Hayes R., Oldfield F. S. Deaths in infancy and early childhood in a well-vaccinated, rural, West African population. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1987 Jun;7(2):91–99. doi: 10.1080/02724936.1987.11748482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon A., Joof D., Rowan K. M., Greenwood B. M. Maternal administration of chloroquine: an unexplored aspect of malaria control. J Trop Med Hyg. 1988 Apr;91(2):49–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne D., Grab B., Fontaine R. E., Hempel J. H. Impact of control measures on malaria transmission and general mortality. Bull World Health Organ. 1976;54(4):369–377. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]