Abstract

Recognition of temperature is a critical element of sensory perception and allows mammals to evaluate both their external environment and internal status. The respiratory epithelium is constantly exposed to the external environment, and prolonged inhalation of cold air is detrimental to human airways. However, the mechanisms responsible for adverse effects elicited by cold air on the human airways are poorly understood. Transient receptor potential melastatin family member 8 (TRPM8) is a well-established cold- and menthol-sensing cation channel. We recently discovered a functional cold- and menthol-sensing variant of the TRPM8 ion channel in human lung epithelial cells. The present study explores the hypothesis that this TRPM8 variant mediates airway cell inflammatory responses elicited by cold air/temperatures. Here, we show that activation of the TRPM8 variant in human lung epithelial cells leads to increased expression of several cytokine and chemokine genes, including IL-1α, -1β, -4, -6, -8, and -13, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and TNF-α. Our results provide new insights into mechanisms that potentially control airway inflammation due to inhalation of cold air and suggest a possible role for the TRPM8 variant in the pathophysiology of asthma.

Keywords: transient receptor potential melastatin family member 8, menthol

temperature regulation is fundamental for survival of warm-blooded animals (36). The perception of cold, which ranges from innocuous (cool) to painful (noxious) cold (28), occurs when the skin is cooled as little as 1°C from normal body temperature (7). This cold sensation arises from the activation of cutaneous receptors when the skin is exposed to decreases in temperatures. TRPM8 (also known as Trp-p8), a member of the transient receptor potential (TRP) superfamily of ion channels, is a ligand-gated, nonselective cation channel (29) that functions as a transducer of innocuous cold stimuli (8–22°C, activation threshold ∼22°C) in the somatosensory system. In addition to being activated by changes in ambient temperature, TRPM8 is also activated by several exogenous ligands, including the cooling agents, menthol and icilin (8, 17, 24, 29, 31, 39). Compounds such as N-(4-tertiarybutylphenyl)-4-(3-chloropyridin-2-yl)tetrahydropyrazine-1(2H)-carboxamide (BCTC), thio-BCTC, and capsazepine are potent inhibitors of TRPM8 responses (4).

The respiratory tract maintains a constant interaction with the external environment. Acute or chronic exposure to cold air elicits several effects on the respiratory system (20, 21), including bronchoconstriction, airway congestion, increased mucous secretions, and decreased mucociliary clearance. Prolonged exposure to cold air increases the number of inflammatory cells (11), elevates concentrations of leukotrienes (LTs), and alters the cytokine profile in lungs of otherwise healthy subjects (12, 20, 21). Unfortunately, cold air also initiates asthma attacks. Hyperventilation with cold air may predispose individuals to airway diseases, and short-term, repetitive hyperventilation with cool (18–20°C) air may cause the development of asthma or an asthma-like state (11, 21), characterized by airway hyperreactivity, bronchial narrowing, airway obstruction, increased airflow resistance, airway mucosal damage, and chronic inflammation (11, 12, 21, 25).

The molecular and biochemical pathways in lung cells that regulate cold-induced responses are largely unknown. It has been proposed that increased smooth muscle tone may not be the sole determinant of cold-induced bronchial constriction and hyperactivity (11). Alterations in the production or release of epithelial cell-derived factors (e.g., cytokines, chemokines, LTs, etc.) that have paracrine functions may directly contribute to airway hyperreactivity observed in many respiratory disorders (16, 21). Thus it is logical to speculate that airway responses elicited by cold air might be in part regulated by airway epithelial cells.

We recently identified and characterized a novel cold- and menthol-activated TRPM8 variant in lung epithelial cells (32a). Activation of the TRPM8 variant receptor within respiratory epithelial cells promoted Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) of cells, cellular uptake of Ca2+, and an increase in transcription of IL-8. We propose that this variant TRPM8 receptor could provide an effective mechanism for modulation of physiological responses of the airways to cold air. Furthermore, aberrant function of the TRPM8 variant could account for increases in diagnostic markers of disease states such as cold-induced asthma. The present study explores the possibility that cold-mediated activation of the TRPM8 variant in lung epithelial cells is responsible for the enhanced expression of several regulatory cytokines and chemokines that are implicated in a variety of human respiratory disorders, including asthma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

Oligonucleotides were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). BCTC was synthesized using published protocols (34). Briefly, BCTC was prepared by reacting 4-(tert-butylphenyl)-carbamic acid phenyl ester with 1-(3-chloropyridin-2-yl)piperazine and collecting the precipitate. The product structure was confirmed with 1H-nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) by comparing the NMR values to those in published literature (34).

Cell culture.

Human bronchial epithelial (BEAS-2B) cells (CRL-9609) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Rockville, MD) and cultured in serum-free LHC-9 media, prepared by fortifying Lechner and LaVeck LHC-8 media (BioSource, Camarillo, CA) with retinoic acid (33 nM) and epinephrine (2.75 μM). Normal human bronchial epithelial (NHBE) cells, a primary bronchial epithelial cell line, was purchased from ATCC and cultured in serum-free bronchial epithelial growth media (Clonetics/Lonza, Walkersville, MD). Culture flasks (Corning, Corning, NY) for the cells were precoated at 37°C with LHC-basal medium (BioSource) fortified with collagen (30 μg/ml), fibronectin (10 μg/ml), and BSA (10 μg/ml). Cells were maintained at 37°C, between 30–90% confluence, in an air-ventilated and humidified incubator with 5% carbon dioxide. For subculturing, cells were trypsin-dissociated and passaged every 2–4 days.

TRPM8shRNA design and cloning.

Short hairpin RNA (shRNA) were used to silence TRPM8 expression in lung cells via RNA interference (27). The following template oligonucleotides were designed to target exon 18 of TRPM8, using the siRNA Target Finder tools (Ambion, Austin, TX): sense 5′-GAT CCG AAA CCT GTC GAC AAG CAC TTC AAG AGA GTG CTT GTC GAC AGG TTT CTT A-3′ and antisense 5′-AGC TTA AGA AAC CTG TCG ACA AGC ACT CTC TTG AAG TGC TTG TCG ACA GGT TTC G-3′. The sense and antisense oligonucleotide pairs were annealed, and the resulting duplex DNA was ligated into the pSilencer 4.1 mammalian expression vector (Ambion) using the BamHI and HindIII sites. A scrambled, nontargeting shRNA was also prepared as a negative control. Vector constructs were transformed into Escherichia coli cells and selected by ampicillin resistance. Plasmid DNA was isolated from individual colonies using QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and the sequence of the shRNA insert was verified by sequencing the PCR products generated from the plasmid DNA.

STABLE TRANSFECTION OF BEAS-2B CELLS WITH TRPM8SHRNA.

Plasmid DNA (1 μg), containing either the TRPM8shRNA or ScrambleshRNA inserts, was transfected into BEAS-2B cells using Effectene Transfection Reagent (10:1 reagent-to-DNA, Qiagen) for 24 h at 37°C. Stably transfected cells were selected by resistance to G418/Geneticin (300 μg/ml, Gibco). Resistant colonies were visible ∼2–3 wk posttransfection. Individual colonies were harvested, expanded, and screened for reduced expression of TRPM8 mRNA by RT-PCR using the following sense and antisense primers: sense 5′-CAG ACC CCT GGG TAC ATG GTG GAT G-3′ and antisense 5′-GCC TTT CAA GGT TGC ATT TTG GGC GAC-3′. The anticipated product size was 593 bp, derived from a region spanning the 3′-UTR of the TRPM8 gene. A 180-bp portion of β-actin cDNA was simultaneously amplified by PCR using the following primers: sense 5′-GAC AAC GGC TCC GGC ATG TGC A-3′ and antisense 5′-TGA GGA TGC CTC TCT TGC TCT G-3′. β-Actin was used as an internal standard to normalize PCR product intensities between samples. A single colony exhibiting decreased TRPM8 expression was used for these studies.

RT-PCR analysis of cytokine gene expression.

NHBE, BEAS-2B cells, and BEAS-2B cells stably transfected with TRPM8shRNA targeted to TRPM8 exon 18 or ScrambleshRNA were subcultured into 25-cm2 flasks and grown to ∼95% confluence. The cells were either exposed to cool temperature (18°C) at various time points (0–4 h), followed by a recovery time of 2 h at 37°C, or treated with menthol (2.5 mM) at multiple time points (0–24 h). Inhibition by a TRPM8 antagonist was evaluated by cotreating NHBE and BEAS-2B cells with BCTC (100 μM). Total RNA was extracted from treated cells using the RNeasy total RNA isolation kit (Qiagen). Five micrograms of total RNA was transcribed into cDNA using an oligo(dT) primer and a cDNA synthesis kit containing Superscript II RT enzyme (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). cDNA corresponding to human IL-1α, -1β, -4, -6, -8, -10, and -13, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), TNF-α, and β-actin were amplified by PCR from 1 μl of the cDNA synthesis reaction using the primers listed in Table 1 and GoTaq Green Master Mix (Promega, Madison, WI). PCR products were resolved on 1% agarose gels, and images were captured using a Gel Doc imaging system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Product quantification was achieved by determining the band intensities for each PCR product relative to the β-actin product using the Gel Doc density analysis tools in the Quantity One software (Bio-Rad). Data are expressed as mean band densities normalized to β-actin, relative to the untreated controls and SD (n = 3). Experiments were reproduced a minimum of three times with different passages of cells.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for RT-PCR analysis of selected cytokine genes

| Gene Name (NCBI Acc. No.) | Product Size, bp | Primer Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| IL-1α | 238 | Sense: 5′-GATGGCCAAAGTTCCAGACATG-3′ |

| (NM_000575) | Antisense: 5′-CCTTCCCGTTGGTTGCTACTACC-3′ | |

| IL-1β | 561 | Sense: 5′-GTGTCTGAAGCAGCCATGGCAG-3′ |

| (NM_000576) | Antisense: 5′-CAACACGCAGGACAGGTACAG-3′ | |

| IL-4 | 381 | Sense: 5′-CACCTATTAATGGGTCTCACCTCC-3′ |

| (NM_000589) | Antisense: 5′-CAGGACAGGAATTCAAGCCCGCC-3′ | |

| IL-6 | 328 | Sense: 5′-CTTCTCCACAAGCGCCTT-3′ |

| (NM_000600) | Antisense: 5′-GGCAAGTCTCCTCATTGAATC-3′ | |

| IL-8 | 410 | Sense: 5′-GTGGCTCTCTTGGCAGCCTTC-3′ |

| (NM_000584) | Antisense: 5′-CAGGAATCTTGTATTGCATCT-3′ | |

| IL-10 | 327 | Sense: 5′-ACAGCTCACCACTGCTCTGT-3′ |

| (NM_000572) | Antisense: 5′-AGTTCACATGCGCCTTGATG-3′ | |

| IL-13 | 467 | Sense: 5′-GCCACCCAGCCTATGCATCCGC-3′ |

| (NM_002188) | Antisense: 5′-GATGCTTTCGAAGTTTCAGTTG-3′ | |

| GM-CSF | 390 | Sense: 5′-GAGCATGTGAATGCCATCCAGGAG-3′ |

| (NM_000758) | Antisense: 5′-CTCCTGGACTGGCTCCCAGCAGTCAAA-3′ | |

| TNF-α | 444 | Sense: 5′-GAGTGACAAGCCTGTAGCCCATGTTGTAGC-3′ |

| (AF043342) | Antisense: 5′-GCAATGATCCCAAAGTAGACCTGCCCAGACT-3′ |

NCBI, National Center for Biotechnology Information; GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA and Dunnett's multiple comparisons posttest with a confidence interval of P ≤ 0.05. The paired t-test with a confidence interval of P ≤ 0.05 was also used where appropriate.

RESULTS

TRPM8 variant-induced alterations in cytokine gene expression in lung epithelial cells.

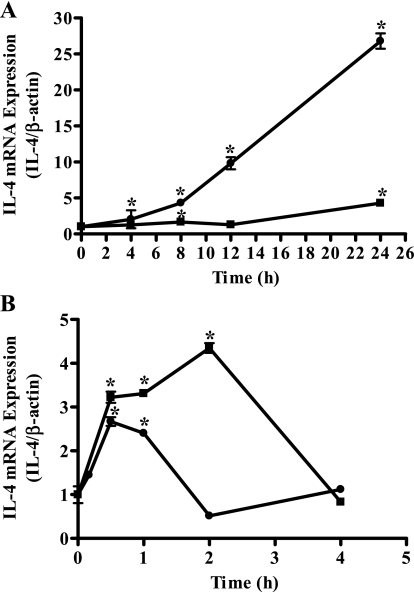

Semiquantitative RT-PCR was used to quantify changes in mRNA for IL-1α, -1β, -4, -6, -8, -10, and -13, GM-CSF, and TNF-α following activation of the TRPM8 variant in NHBE and BEAS-2B cells with menthol (2.5 mM) or exposure to cold (18°C). To ensure that the transcriptional machinery of the cells had ample recovery time following cold exposures, the cells were maintained at 37°C for a period of 2 h after cold treatment. TRPM8 variant activation by menthol (2.5 mM) led to significant increases in mRNA for IL-1α, -1β, -4, -6, -8, and -13, GM-CSF, and TNF-α following treatment of NHBE and BEAS-2B cells up to 24 h (Table 2). Substantial increases in mRNA expression for IL-1α, -1β, -4, -6, -8, -10, and -13, GM-CSF, and TNF-α were also detected following TRPM8 variant activation by cold (18°C) treatment using exposure times of 0–4 h in both NHBE and BEAS-2B cells (Table 3). Figure 1, A and B, illustrates the kinetics of IL-4 mRNA expression in NHBE (solid squares) and BEAS-2B cells (solid circles) following menthol and cold (18°C) treatments, respectively. Maximum changes in gene expression following menthol and cold (18°C) treatment for all of the cytokines tested as well as the time at which maximum mRNA induction was observed are also presented in Tables 2 and 3. Increased expression of IL-6 and IL-8 mRNA by NHBE and BEAS-2B cells following TRPM8 activation by cold (18°C) treatment were shown by the quantitative real-time RT-PCR technique (data not shown).

Table 2.

Menthol-induced increases in cytokine mRNA levels

| Gene |

NHBE Cells |

BEAS-2B Cells

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time of Maximum Increase, h | Maximum Response, fold control ±SD | Time of Maximum Increase, h | Maximum Response, fold control ±SD | |

| IL-1α | 24 | 2.2±0.1* | 8 | 3.2±0.1* |

| IL-1β | 8 | 2.5±0.1* | 4 | 2.30±0.03* |

| IL-4 | 24 | 4.3±0.2* | 24 | 27±2* |

| IL-6 | 24 | 2.8±0.5* | 12 | 7.9±0.2* |

| IL-8 | 4 | 2.0±0.1* | 24 | 21.4±0.3* |

| IL-13 | 8 | 2.3±0.5* | 4 | 4.9±0.1* |

| GM-CSF | 24 | 7.4±0.1* | 12 | 8.0±0.1* |

| TNF-α | 12 | 3.9±0.2* | 4 | 4.6±0.5* |

Statistically significant increase relative to untreated control (ANOVA, P ≤ 0.05; n = 3). PCR products corresponding to IL-10 mRNA were not detected after menthol treatment. NHBE cells, normal human bronchial epithelial cells; BEAS-2B cells, human bronchial epithelial cells.

Table 3.

Cold (18°C)-induced increases in cytokine mRNA levels

| Gene |

NHBE Cells |

BEAS-2B Cells

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time of Maximum Increase, h | Maximum Response, fold control ±SD | Time of Maximum Increase, h | Maximum Response, fold control ±SD | |

| IL-1α | 4 | 2.3±0.1* | 4 | 3.8±0.1* |

| IL-1β | 0.017 | 4.6±0.6* | 0.17 | 4.4±0.4* |

| IL-4 | 2 | 4.4±0.2* | 0.5 | 2.7±0.2* |

| IL-6 | 4 | 2.2±0.4* | 4 | 17±1* |

| IL-8 | 1 | 3.10±0.01* | 4 | 28.0±5.0* |

| IL-10 | 4 | 4.4±0.2* | 4 | 3.9±0.6* |

| IL-13 | 0.17 | 13.3±0.5* | 0.083 | 1.5±0.1 |

| GM-CSF | 0.5 | 4.9±0.2* | 2 | 3.1±0.3* |

| TNF-α | 4 | 4.0±0.2* | 4 | 12±1* |

Statistically significant increase relative to untreated control (ANOVA, P ≤ 0.05; n = 3).

Fig. 1.

Menthol and cold (18°C) induced increases in IL-4 mRNA in lung epithelial cells. A: induction of IL-4 mRNA expression by menthol (2.5 mM) in normal human bronchial epithelial (NHBE; solid squares) and human bronchial epithelial (BEAS-2B) cells (solid circles). B: induction of IL-4 mRNA expression by cold (18°C) treatment in NHBE (solid squares) and BEAS-2B cells (solid circles). Data are presented as PCR product intensity normalized to β-actin and are standardized to untreated control with SD (n = 3). *Time points at which statistically significant (ANOVA, P ≤ 0.05) increases in IL-4 mRNA were observed.

Induction of cytokine gene transcription required unusually high concentrations of menthol, but the structure of the truncated TRPM8 protein in lung cells provides an explanation for a lack of receptor sensitivity. The variant TRPM8 possesses the requisite fourth and fifth transmembrane domains that are required for menthol-dependent activation (2, 38) but lacks the second transmembrane domain that is necessary for menthol activation of the full-length TRPM8 receptor at submicromolar concentrations (2). Therefore, we expected the truncated TRPM8 variant to require higher concentrations of menthol for activation. Extended exposures to cold (18°C) were required to induce cytokine gene transcription in the lung epithelial cells. Therefore, cytotoxicity assays were performed to examine cellular susceptibility to high concentrations of menthol and long cold temperatures. Treatment of NHBE and BEAS-2B cells with menthol (2.5 mM) for up to 24 h was essentially nontoxic to cells, and ∼98–100% cell viability was maintained. Likewise, no cell death (∼95–100% cell viability maintained) was observed following 24-h exposure to cold (18°C) in both NHBE and BEAS-2B cells (data not shown). These results clearly suggest that cytokine gene induction was the consequence of enhanced gene transcription elicited by the activation of the TRPM8 variant in cells and not due to alterations in cell membrane integrity or overt damage to cells.

Inhibition of TRPM8 variant-induced cytokine alterations in cells stably overexpressing TRPM8shRNA.

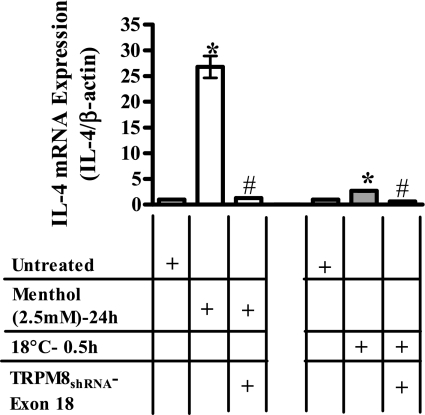

To substantiate that the menthol- and cold (18°C)-stimulated increases in cytokine mRNA were a direct consequence of TRPM8 variant stimulation, BEAS-2B cells stably expressing TRPM8shRNA targeted to TRPM8 exon 18 were treated with menthol (2.5 mM) or cold (18°C) for various time points (0–24 h), and cytokine gene expression was quantified. Both menthol- and cold-induced increases in mRNA for IL-1α, -1β, -4, -6, -8, and -13, GM-CSF, and TNF-α were attenuated in cells overexpressing shRNA targeted to exon 18 of the TRPM8 gene (Tables 4 and 5). Figure 2 demonstrates the effect of TRPM8 gene knockdown on changes in IL-4 mRNA following treatment with menthol (2.5 mM, 24 h) or exposure to cold (18°C, 0.5 h). Tables 4 and 5 provide inhibition data for all cytokines evaluated.

Table 4.

Effect of TRPM8 knockdown on menthol-induced cytokine levels

| Gene |

BEAS-2B Cells |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Time of Maximum Increase, h | Maximum Response, fold control ±SD | TRPM8shRNA + Menthol (2.5 mM) | |

| IL-1α | 8 | 3.2±0.1* | 0.80±0.03# |

| IL-1β | 4 | 2.30±0.03* | 0.20±0.03# |

| IL-4 | 24 | 27±2* | 1.30±0.02# |

| IL-6 | 12 | 7.9±0.2* | 1.20±0.04# |

| IL-8 | 24 | 21.4±0.3* | 1.50±0.04# |

| IL-13 | 4 | 4.9±0.1* | 0.20±0.01# |

| GM-CSF | 12 | 8.0±0.1* | 0.20±0.04# |

| TNF-α | 4 | 4.6±0.5* | 0.20±0.01# |

Statistically significant increase relative to untreated control (paired t-test, P ≤ 0.05; n = 3);

statistically significant decrease relative to menthol (paired t-test, P ≤ 0.05; n = 3). Treatments consisted of untreated controls and menthol (2.5 mM) treatment for various time points (0–24 h) with and without transient receptor potential melastatin family member 8 (TRPM8) knockdown using TRPM8shRNA targeted to exon 18. Effect of TRPM8shRNA on IL-10 mRNA levels was not tested, as PCR products corresponding to IL-10 gene were not evident, following menthol treatments.

Table 5.

Effect of TRPM8 knockdown on cold (18°C)-induced cytokine levels

| Gene |

BEAS-2B Cells |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Time of Maximum Increase, h | Maximum Response, fold control ±SD | TRPM8shRNA + Cold (18°C) | |

| IL-1α | 4 | 3.8±0.1* | 1.10±0.02# |

| IL-1β | 0.17 | 4.4±0.4* | 1.00±0.02# |

| IL-4 | 0.5 | 2.7±0.2* | 0.60±0.02# |

| IL-6 | 4 | 16.5±1.3* | 1.2±0.1# |

| IL-8 | 4 | 28±5* | 1.9±0.2# |

| IL-10 | 4 | 3.9±0.6* | 0.8±0.3# |

| IL-13 | 0.083 | 1.5±0.1 | 0.9±0.3 |

| GM-CSF | 2 | 3.1±0.3* | 1.10±0.03# |

| TNF-α | 4 | 12±1* | 1.3±0.1# |

Statistically significant increase relative to untreated control (paired t-test, P ≤ 0.05; n = 3);

statistically significant decrease relative to cold (paired t-test, P ≤ 0.05; n = 3). Treatments consisted of untreated controls and cold (18°C) exposure for various time points (0–4 h) with and without TRPM8 knockdown using TRPM8shRNA targeted to exon 18.

Fig. 2.

Effect of transient receptor potential melastatin family member 8 (TRPM8) silencing on menthol- and cold (18°C)-induced IL-4 transcription. Inhibition of menthol (2.5 mM, white bars) and cold (18°C, gray bars) induced IL-4 mRNA induction in cells stably overexpressing TRPM8shRNA targeted to exon 18. Data represent PCR product intensities normalized to β-actin and standardized to untreated control with SD (n = 3). Values significantly (paired t-test, P ≤ 0.05) different from untreated and menthol- or cold-treated cells are represented by * and #, respectively.

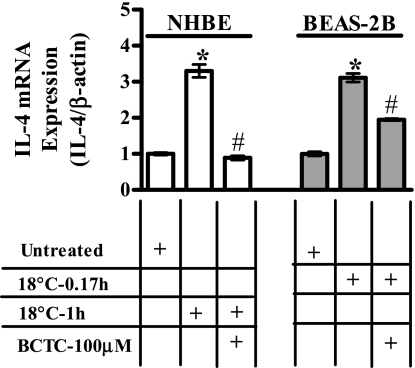

Inhibition of TRPM8 variant-induced cytokine alterations by BCTC.

NHBE and BEAS-2B cells were exposed to cold (18°C) with and without cotreatment with the TRPM8 antagonist, BCTC (100 μM). Increases in the expression of mRNA for IL-1α, -1β, -4, -6, -8, and -13, GM-CSF, and TNF-α following cold (18°C) exposure were attenuated by BCTC (100 μM) in both NHBE and BEAS-2B cells (Table 6). Figure 3 illustrates the effect of BCTC on the expression of mRNA for IL-4 following exposure to cold (18°C) for 1 h in NHBE cells and for 0.17 h in BEAS-2B cells. Table 6 presents inhibition data for all cytokine genes evaluated.

Table 6.

Effect of BCTC on cold (18°C)-induced cytokine levels

| Gene |

NHBE Cells |

BEAS-2B Cells

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time of Maximum Increase, h | Maximum Response, fold control ±SD | BCTC (100 μM) + cold (18°C) | Time of Maximum Increase, h | Maximum Response, fold control ±SD | BCTC (100 μM) + Cold (18°C) | |

| IL-1α | 4 | 2.3±0.1* | 1.20±0.02# | 4 | 2.7±0.2* | 1.0±0.02# |

| IL-1β | 0.5 | 2.2±0.1* | 0.50±0.04# | 0.17 | 4.4±0.4* | 0.60±0.02# |

| IL-4 | 2 | 4.4±0.2* | 0.7±0.1# | 0.5 | 3.1±0.2* | 1.5±0.1# |

| IL-6 | 4 | 2.2±0.4* | 0.30±0.03# | 4 | 17±1* | 1.10±0.04# |

| IL-8 | 1 | 3.10±0.01* | 1.10±0.02# | 4 | 28±5* | 1.80±0.04# |

| IL-13 | 0.5 | 5.1±0.1* | 0.6±0.1* | |||

| GM-CSF | 0.5 | 4.9±0.2* | 1.0±0.1# | 2 | 3.1±0.3* | 1.50±0.02# |

| TNF-α | 4 | 4.0±0.2* | 2.1±0.2* | 4 | 12±1* | 2.8±0.1# |

Statistically significant increase relative to untreated control (paired t-test, P ≤ 0.05; n = 3);

statistically significant decrease relative to cold (paired t-test, P ≤ 0.05; n = 3). Treatments consisted of untreated controls and cold (18°C) exposure for various time points (0–4 h) with and without N-(4-tertiarybutylphenyl)-4-(3-chloropyridin-2-yl)tetrahydropyrazine-1(2H)-carboxamide (BCTC; 100 μM) cotreatment. The effects of BCTC (100 μM) on cold-induced IL-10 and -13 mRNA levels were inconsistent and hence not reported.

Fig. 3.

Effect of N-(4-tertiarybutylphenyl)-4-(3-chloropyridin-2-yl)tetrahydropyrazine-1(2H)-carboxamide (BCTC) on cold (18°C)-induced IL-4 transcription. Inhibition of cold (18°C)-induced IL-4 mRNA induction by BCTC (100 μM) in NHBE (white bars) and BEAS-2B cells (gray bars). Data represent PCR product intensities normalized to β-actin and standardized to untreated control with SD (n = 3). Values significantly (paired t-test, P ≤ 0.05) different from untreated and cold-treated cells are represented by * and #, respectively.

Effect of menthol pretreatment on cold-induced cytokine responses.

In neurons and TRPM8-overexpressing human embryonic kidney HEK-293 cells, menthol potentiates cold-evoked responses (24). To evaluate whether menthol enhanced cold-induced cytokine responses in lung epithelial cells, BEAS-2B cells were pretreated with menthol (2.5 mM) for 8 h followed by exposure to cold (18°C) for 0.5 or 1 h. Cellular content of mRNA for five cytokines, IL-4, -6, -8, and -13, and GM-CSF, was determined. Menthol pretreatment exaggerated the typical cellular response to cold for IL-4, -6, and -8, and GM-CSF in an additive manner (Table 7). Interestingly, menthol pretreatment inhibited the induction of IL-13 mRNA by cold treatment. Figure 4 illustrates the effect of menthol pretreatment on cold (18°C)-induced mRNA induction for IL-4 in BEAS-2B cells. Table 7 shows the effects of menthol pretreatment for all cytokines tested except IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-10, and TNF-α.

Table 7.

Effect of menthol pretreatment on cold (18°C)-induced cytokine levels

| Gene |

BEAS-2B Cells |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time of Maximum Increase, h | Cold (18°C)-Induced Response, fold control ±SD | Menthol (2.5 mM, 8 h)-Induced Response, fold control ±SD | Menthol (2.5 mM, 8 h) Pretreatment + Cold (18°C), fold control ±SD | |

| IL-4 | 1 | 4.3±0.3* | 2.2±0.3* | 6.2±0.2# |

| IL-6 | 0.5 | 2.7±0.2* | 6.2±0.4* | 10.7±0.8# |

| IL-8 | 0.5 | 2.1±0.1* | 6.0±0.8* | 10.7±0.4# |

| IL-13 | 1 | 1.4±0.1 | 4.9±0.1* | 0.90±0.09 |

| GM-CSF | 0.5 | 2.8±0.1* | 12.1±0.5* | 14.3±0.6# |

Statistically significant increase relative to untreated control (paired t-test, P ≤ 0.05; n = 3);

statistically significant increase relative to cold and menthol (paired t-test, P ≤ 0.05; n = 3). Treatments consisted of untreated controls, menthol (2.5 mM) treatment for 8 h, and cold (18°C) exposure for either 0.5 or 1 h, with and without menthol (2.5 mM, 8 h) pretreatment.

Fig. 4.

Effect of menthol pretreatment on cold (18°C)-induced IL-4 transcription. Potentiation of cold (18°C, 0.5 h)- induced IL-4 mRNA expression by menthol (2.5 mM) pretreatment (8 h, black bars) vs. that of menthol (light gray bars) and cold (medium gray bars) treatments alone in BEAS-2B cells. Data represent PCR product intensities normalized to β-actin and standardized to untreated control with SD (n = 3). Values significantly (paired t-test, P ≤ 0.05) different from untreated cells are represented by *, whereas values significantly (paired t-test, P ≤ 0.05) different from menthol- and cold-treated cells are represented by #.

DISCUSSION

Epithelial cells of the trachea and bronchi are constantly exposed to inspired air. Human airways exhibit a complex pattern of responses when exposed to cold air, including altered cytokine and chemokine profiles and an increase in the number of inflammatory cells in the lungs. Repeated or chronic exposures to cold air often lead to asthma or asthma-like symptoms in susceptible subjects and are most commonly accompanied by chronic airway inflammation. The precise mechanism by which cold air promotes an inflammatory response in normal healthy subjects is not well-understood. Even less well-understood is how cold air exposure promotes airway pathologies such as cold-induced asthma.

The airway epithelium is in a unique position to interpret and respond to changes in inspired air (19). Human bronchial epithelial cells are capable of synthesizing and releasing a multitude of biochemical mediators, including cytokines and chemokines, on stimulation (5, 19, 22). These include colony-stimulating factors (CSFs) such as GM-CSF, granulocyte (G-CSF), macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF), cytokines such as TNF-α, interleukins like IL-1 (-α and -β), IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-11, IL-13, LTs B4 and C4 (LTB4 and LTC4), prostanoids such as prostaglandins D2, E2, and F2α (PGD2, PGE2, and PGF2α), etc. (3, 5, 6, 9, 18, 22, 23, 26, 30, 32, 33). A significant number of these mediators are present at higher concentrations in bronchial epithelial cells isolated from symptomatic asthmatics (23, 30). Pleiotropic effects exhibited by these mediators modulate signaling cascades and associated responses in cells throughout the lungs, including airway epithelial cells, resident immune cells, sensory neurons, smooth muscle cells, etc. Thus the airway epithelium serves as both a target and a regulator of inflammatory processes (30). However, the precise role of the bronchial epithelium in human airway diseases such as asthma remains undefined (26).

TRPM8 is a nonselective cation channel activated by innocuous cold temperatures (8–22°C) and menthol (29). Besides its conventional role in temperature perception, the presence of TRPM8 in various nonneuronal tissues such as the prostate, urinary bladder, testes, etc. (1, 35, 37, 39) suggests a much broader role for TRPM8 in mammalian physiology. We recently identified and characterized an NH2-terminally truncated variant of the TRPM8 ion channel expressed in human lung epithelial cells (32a). The variant TRPM8 was preferentially localized to the ER and was functional in regulating cold- and menthol-induced ER Ca2+ release, cellular uptake of Ca2+, and Ca2+-dependent increases in the expression of mRNA for IL-8 mRNA in lung epithelial cells. Based on these results, the hypothesis that activation of the functional TRPM8 variant receptor in human airway epithelial cells controls cellular responses to cold air/temperature-induced inflammation was investigated.

In this study, it was demonstrated that activation of the TRPM8 variant in the bronchial epithelial cells by cold treatment and menthol produced significant increases in the expression of several critical regulatory cytokine and chemokine genes, including IL-1α, -1β, -4, -6, -8, -10, and -13, GM-CSF, and TNF-α (Fig. 1, A and B, and Tables 2 and 3). All of these factors are known to play distinct roles in normal respiratory function, innate immunity, and in the pathophysiology of bronchial hyperreactivity and asthma. Both the menthol- and cold-induced release of these cytokines was attenuated by the TRPM8 antagonist BCTC as well as by shRNA-mediated knockdown of TRPM8 mRNA expression in the lung cells.

Under conditions of short-term cold exposures, activation of cytokine response pathways might have detrimental effects on the airways. Airway epithelial cells may initiate short-term compensatory mechanisms to counteract the effects of short-term cold exposures; e.g., stimulation and release of anti-inflammatory and cyto-protective mediators such as IL-6, which has the ability to contribute to humoral and cellular defense mechanisms and to diminish tissue inflammation and injury (10, 13, 14, 33). Similarly, IL-10 has the potential to downregulate both T helper type 1 (Th1) and Th2-driven inflammatory processes and has beneficial effects on airway remodeling (14, 18). Activation of such counteractive mechanisms would be an obvious advantage to the respiratory system because they would ameliorate proinflammatory cytokine-mediated damage to the respiratory tract. However, prolonged exposure to cold is deleterious to the airways. In this case, the short-term compensatory responses would be overwhelmed, leading to substantial induction of proinflammatory cytokines and activation of subsequent inflammatory response pathways; e.g., activation of the multifunctional cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1 (-α and -β), IL-4, and IL-13, exert pleiotropic, proinflammatory effects on several target cells, including inflammatory and structural airway cells (18, 33). Recruitment of chemokines such as IL-4 and IL-8 and CSFs like GM-CSF to the local airway environment is known to promote and prolong the survival, activation, and differentiation of inflammatory cells such as eosinophils, neutrophils, and macrophages (5, 14, 18, 32, 33), which enhances airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness by augmented cytokine production (10, 15).

Increased expression of several proinflammatory cytokines induced by activation of the TRPM8 variant in lung epithelial cells, as suggested by our study, raises the intriguing possibility that this TRPM8 variant functions to maintain lung homeostasis under normal circumstances. However, prolonged exposure to cold air and activation of the TRPM8 variant in lung epithelial cells may contribute to various respiratory pathologies such as cold-induced asthma.

In conclusion, this study highlights a novel function for the TRPM8 variant in nonneuronal responses to cold temperature. The regulatory role of the TRPM8 variant in inflammatory responses in the lung will have significant implications in understanding molecular mechanisms of cold-induced inflammation and airway diseases, such as asthma, and will subsequently aid in development of viable drug targets to treat these diseases.

GRANTS

Support for this work was provided by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-069813.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mohammed Shadid for synthesizing BCTC. We also acknowledge Dr. Mark Johansen for helpful suggestions and insightful comments and Diane Lanza for technical assistance with these studies.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abe J, Hosokawa H, Okazawa M, Kandachi M, Sawada Y, Yamanaka K, Matsumura K, Kobayashi S. TRPM8 protein localization in trigeminal ganglion and taste papillae. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 136: 91–98, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bandell M, Dubin AE, Petrus MJ, Orth A, Mathur J, Hwang SW, Patapoutian A. High-throughput random mutagenesis screen reveals TRPM8 residues specifically required for activation by menthol. Nat Neurosci 9: 493–500, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes PJ, Chung KF, Page CP. Inflammatory mediators of asthma: an update. Pharmacol Rev 50: 515–596, 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Behrendt HJ, Germann T, Gillen C, Hatt H, Jostock R. Characterization of the mouse cold-menthol receptor TRPM8 and vanilloid receptor type-1 VR1 using a fluorometric imaging plate reader (FLIPR) assay. Br J Pharmacol 141: 737–745, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell AM Bronchial epithelial cells in asthma. Allergy 52: 483–489, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell AM, Vignola AM, Chanez P, Godard P, Bousquet J. Low-affinity receptor for IgE on human bronchial epithelial cells in asthma. Immunology 82: 506–508, 1994. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campero M, Serra J, Bostock H, Ochoa JL. Slowly conducting afferents activated by innocuous low temperature in human skin. J Physiol 535: 855–865, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chuang HH, Neuhausser WM, Julius D. The super-cooling agent icilin reveals a mechanism of coincidence detection by a temperature-sensitive TRP channel. Neuron 43: 859–869, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chung KF, Barnes PJ. Cytokines in asthma. Thorax 54: 825–857, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cromwell O, Hamid Q, Corrigan CJ, Barkans J, Meng Q, Collins PD, Kay AB. Expression and generation of interleukin-8, IL-6 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor by bronchial epithelial cells and enhancement by IL-1 beta and tumour necrosis factor-alpha. Immunology 77: 330–337, 1992. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis MS, Freed AN. Repeated hyperventilation causes peripheral airways inflammation, hyperreactivity, and impaired bronchodilation in dogs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 164: 785–789, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis MS, Malayer JR, Vandeventer L, Royer CM, McKenzie EC, Williamson KK. Cold weather exercise and airway cytokine expression. J Appl Physiol 98: 2132–2136, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elias JA, Zhu Z, Chupp G, Homer RJ. Airway remodeling in asthma. J Clin Invest 104: 1001–1006, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feghali CA, Wright TM. Cytokines in acute and chronic inflammation. Front Biosci 2: d12–d26, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hallsworth MP, Soh CP, Lane SJ, Arm JP, Lee TH. Selective enhancement of GM-CSF, TNF-alpha, IL-1 beta and IL-8 production by monocytes and macrophages of asthmatic subjects. Eur Respir J 7: 1096–1102, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hay DW, Farmer SG, Raeburn D, Robinson VA, Fleming WW, Fedan JS. Airway epithelium modulates the reactivity of guinea-pig respiratory smooth muscle. Eur J Pharmacol 129: 11–18, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang J, Zhang X, McNaughton PA. Modulation of temperature-sensitive TRP channels. Semin Cell Dev Biol 17: 638–645, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kips JC Cytokines in asthma. Eur Respir J Suppl 34: 24s–33s, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knight DA, Holgate ST. The airway epithelium: structural and functional properties in health and disease. Respirology 8: 432–446, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koskela HO Cold air-provoked respiratory symptoms: the mechanisms and management. Int J Circumpolar Health 66: 91–100, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larsson K, Tornling G, Gavhed D, Muller-Suur C, Palmberg L. Inhalation of cold air increases the number of inflammatory cells in the lungs in healthy subjects. Eur Respir J 12: 825–830, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levine SJ Bronchial epithelial cell-cytokine interactions in airway inflammation. J Investig Med 43: 241–249, 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mattoli S, Marini M, Fasoli A. Expression of the potent inflammatory cytokines, GM-CSF, IL6, and IL8, in bronchial epithelial cells of asthmatic patients. Chest 101: 27S–29S, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKemy DD, Neuhausser WM, Julius D. Identification of a cold receptor reveals a general role for TRP channels in thermosensation. Nature 416: 52–58, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McLane ML, Nelson JA, Lenner KA, Hejal R, Kotaru C, Skowronski M, Coreno A, Lane E, McFadden ER Jr. Integrated response of the upper and lower respiratory tract of asthmatic subjects to frigid air. J Appl Physiol 88: 1043–1050, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michel FB, Bousquet J, Godard P. [Bronchial epithelium and asthma]. Bull Acad Natl Med 176: 683–692, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paddison PJ, Caudy AA, Bernstein E, Hannon GJ, Conklin DS. Short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) induce sequence-specific silencing in mammalian cells. Genes Dev 16: 948–958, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patapoutian A, Peier AM, Story GM, Viswanath V. ThermoTRP channels and beyond: mechanisms of temperature sensation. Nat Rev Neurosci 4: 529–539, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peier AM, Moqrich A, Hergarden AC, Reeve AJ, Andersson DA, Story GM, Earley TJ, Dragoni I, McIntyre P, Bevan S, Patapoutian A. A TRP channel that senses cold stimuli and menthol. Cell 108: 705–715, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raeburn D, Webber SE. Proinflammatory potential of the airway epithelium in bronchial asthma. Eur Respir J 7: 2226–2233, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reid G, Babes A, Pluteanu F. A cold- and menthol-activated current in rat dorsal root ganglion neurones: properties and role in cold transduction. J Physiol 545: 595–614, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Renauld JC New insights into the role of cytokines in asthma. J Clin Pathol 54: 577–589, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32a.Sabnis AS, Shadid M, Yost GS, Reilly CA. Human lung epithelial cells express a functional cold-sensing TRPM8 variant. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Shelhamer JH, Levine SJ, Wu T, Jacoby DB, Kaliner MA, Rennard SI. NIH conference. Airway inflammation. Ann Intern Med 123: 288–304, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tafesse L, Sun Q, Schmid L, Valenzano KJ, Rotshteyn Y, Su X, Kyle DJ. Synthesis and evaluation of pyridazinylpiperazines as vanilloid receptor 1 antagonists. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 14: 5513–5519, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thebault S, Lemonnier L, Bidaux G, Flourakis M, Bavencoffe A, Gordienko D, Roudbaraki M, Delcourt P, Panchin Y, Shuba Y, Skryma R, Prevarskaya N. Novel role of cold/menthol-sensitive transient receptor potential melastatine family member 8 (TRPM8) in the activation of store-operated channels in LNCaP human prostate cancer epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 280: 39423–39435, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thut PD, Wrigley D, Gold MS. Cold transduction in rat trigeminal ganglia neurons in vitro. Neuroscience 119: 1071–1083, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsavaler L, Shapero MH, Morkowski S, Laus R. Trp-p8, a novel prostate-specific gene, is up-regulated in prostate cancer and other malignancies and shares high homology with transient receptor potential calcium channel proteins. Cancer Res 61: 3760–3769, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Voets T, Owsianik G, Janssens A, Talavera K, Nilius B. TRPM8 voltage sensor mutants reveal a mechanism for integrating thermal and chemical stimuli. Nat Chem Biol 3: 174–182, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang L, Barritt GJ. TRPM8 in prostate cancer cells: a potential diagnostic and prognostic marker with a secretory function? Endocr Relat Cancer 13: 27–38, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]