Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Retinol-binding protein 4 (RBP4), originally known for retinol transport, was recently identified as an adipokine affecting insulin resistance. The RBP4 −803GA promoter polymorphism influences binding of hepatic nuclear factor 1α and is associated with type 2 diabetes in case–control studies. We hypothesised that the RBP4 −803GA polymorphism increases type 2 diabetes risk at a population-based level. In addition, information on retinol intake and plasma vitamin A levels enabled us to explore the possible underlying mechanism.

Methods

In the Rotterdam Study, a prospective, population-based, follow-up study, the −803GA polymorphism was genotyped. In Cox proportional hazards models, associations of the −803GA polymorphism and retinol intake with type 2 diabetes risk were examined. Moreover, the interaction of the polymorphism with retinol intake on type 2 diabetes risk was assessed. In a subgroup of participants the association of the polymorphism and vitamin A plasma levels was investigated.

Results

Homozygous carriers of the −803A allele had increased risk of type 2 diabetes (HR 1.83; 95% CI 1.26–2.66). Retinol intake was not associated with type 2 diabetes risk and showed no interaction with the RBP4 −803GA polymorphism. Furthermore, there was no significant association of the polymorphism with plasma vitamin A levels.

Conclusions/interpretation

Our results provide evidence that homozygosity for the RBP4 −803A allele is associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes in the Rotterdam population. This relationship was not clearly explained by retinol intake and vitamin A plasma levels. Therefore, we cannot differentiate between a retinol-dependent or -independent mechanism of this RBP4 variant.

Keywords: Polymorphism, RBP4, Retinol, Type 2 diabetes, Vitamin A

Introduction

Insulin resistance and beta cell failure are major components of the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes [1]. In the past years, it has become apparent that adipose tissue is an endocrine organ that secretes adipokines affecting insulin sensitivity [2]. Recently, retinol-binding protein 4 (RBP4) was identified as a new adipokine that links glucose uptake in adipocytes to systemic insulin resistance [3].

Originally, RBP4 was known as the only transport protein for retinol [4], but Yang et al. [3] demonstrated a new function, by showing that adipose tissue-specific Glut4 (also known as Slc2a4) knockout mice have increased serum levels of RBP4. Downregulation of GLUT4 in adipose tissue is an important feature of insulin resistance [5]. RBP4 may be an important mechanistic link between downregulated GLUT4 in adipose tissue and systemic insulin resistance. This was confirmed in humans as well: RBP4 levels and the level of insulin resistance were correlated in people with obesity and impaired glucose tolerance, and in patients with type 2 diabetes [6]. Moreover, RBP4 correlated with the level of insulin resistance in normoglycaemic men with a positive family history of type 2 diabetes, suggesting an underlying genetic predisposition. [6]

In a Mongolian case–control study, four single nucleotide polymorphisms in the RBP4 gene were associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes [7]. The −803GA polymorphism, located near an hepatic nuclear factor 1α (HNF1α)-binding motif, affects serum RBP4 levels and influences transcription efficiency and binding of HNF1α [7]. So far, the relationship between genetic variants in the RBP4 gene and type 2 diabetes risk has not been studied prospectively.

The mechanisms by which RBP4 affects insulin sensitivity are largely unknown. Yang et al. [3] showed that RBP4 impaired muscle insulin signalling and increased the levels of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) in mouse liver. Whether these effects are based on retinol-dependent or -independent mechanisms is unclear.

The findings so far suggest that variation in the RBP4 gene is involved in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes and that RBP4 is a candidate gene for type 2 diabetes susceptibility. In a large prospective population-based study, we investigated the effect of the RBP4 −803GA polymorphism on type 2 diabetes risk. In addition, we assessed the association of retinol intake with risk of type 2 diabetes and its interaction with the RBP4 polymorphism. Finally, we analysed the effect of the RBP4 polymorphism on plasma vitamin A levels.

Methods

Study population

Details of the Rotterdam Study have been described previously [8]. In short, the Rotterdam Study is an ongoing prospective, population-based, cohort study in 7,983 inhabitants of a suburb in Rotterdam, designed to investigate determinants of chronic diseases in the elderly. Participants were aged 55 years or older. Baseline examinations were performed from 1990 until 1993. Follow-up examinations took place in 1993–1994, 1997–1999 and 2002–2004. Continuous surveillance on major disease outcomes was conducted between these examinations. Information on vital status was derived from municipal health authorities. The medical ethics committee of the Erasmus Medical Center approved the study protocol and all participants gave their written informed consent.

Diabetes

In accordance with the guidelines of the World Health Organization [9] and the American Diabetes Association [10], diabetes was diagnosed at fasting plasma glucose levels ≥7.0 mmol/l and/or a non-fasting plasma glucose levels ≥11.0 mmol/l and/or treatment with antidiabetic medication (oral medication or insulin) and/or a diagnosis of diabetes as registered by a general practitioner. At baseline, prevalent cases of diabetes were diagnosed by a non-fasting or post-load glucose level (after OGTT) ≥11.1 mmol/l and/or treatment with antidiabetic medication (oral medication or insulin) and the diagnosis diabetes as registered by a general practitioner.

In the current study, patients diagnosed with type 1 diabetes according to the general practitioners’ records were excluded. For the present study, baseline data were collected between 1990 and 1993.

Genotyping

DNA material was available for genotyping of 6,571 participants. The −803GA polymorphism (rs3758539) in the RBP4 gene was genotyped by means of a Taqman allelic discrimination assay. The assay was designed and optimised by Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA, USA; http://store.appliedbiosystems.com). We genotyped 90 blood bank samples to test for adequate cloud separation. In the Rotterdam Study samples, 325 samples were genotyped in duplo, of which one gave an inconsistent result. To monitor contamination, 650 blank samples were incorporated on the plates, of which all gave a blank result. Reactions were performed on the Taqman Prism 7900HT platform. Genotyping was successful in 6,366 participants.

Assessment of dietary and plasma levels of vitamin A

Dietary intake was assessed by means of an extensive, validated semiquantitative food-frequency questionnaire (SFFQ) [11]. A trained dietitian interviewed the participants. The food and drink intake from the SFFQ were converted to energy and nutrient intake according to the Dutch Food Composition Table [12]. In the current study, we used data on dietary intake of α-carotene (μg/day) and β-carotene (μg/day), β-cryptoxanthin (μg/day) and total energy (kJ/day). Alpha-carotene, β-carotene and β-cryptoxanthin were converted to retinol equivalents (RE; amount of RE = [μg retinol] + [μg β-carotene/6] + [μg α-carotene/12] + [μg β-cryptoxanthin/12] per day). Data on retinol intake were available for 5,642 participants.

Plasma levels of vitamin A were measured in a subgroup of 395 genotyped participants. At the second follow-up examination, blood samples were drawn after an overnight fast. Citrate plasma was immediately frozen and stored at −80°C. Total vitamin A plasma levels (retinol) were determined by a previously described method [13]. Briefly, reversed-phase HPLC with UV detection was performed using an RP C18 Column 100 × 4.6 mm (Merck Lichrospher 100RP-18e; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Vitamin A was detected at 324 nm. The inter-assay CV was 4.0%.

Statistical methods

Analyses were performed with SPSS software version 12.0.1. Continuous variables are expressed as means ± SEM. Comparisons between groups were performed with ANOVA and χ 2 testing for normally distributed continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium was assessed by means of χ 2 testing.

We tested the association of the RBP −803GA polymorphism, RE intake and their interaction with type 2 diabetes risk in Cox proportional hazards models. Participants with prevalent type 2 diabetes at baseline were excluded from the analyses, since they may contain selection biases such as survival bias. For the polymorphism the additive, dominant or recessive model was chosen based on the genotypic test and the best-estimated log-likelihood statistic in univariate Cox proportional hazards regression. For the interaction analysis an interaction term was created by entering the product of the −803GA polymorphism and retinol intake to a model with both independent variables. All models were adjusted for year of birth and sex. Additional models were adjusted for BMI.

RE intake was adjusted for energy intake by saving the standardised residuals of a linear regression model with RE intake as dependent variable and total energy intake as independent variable. These standardised residuals represent the remaining variation in RE intake after correcting for energy intake. These standardised residuals were entered as an independent variable in subsequent models.

Results

Baseline characteristics In 6,320 successfully genotyped people, diabetes status was available. Of these, 658 had prevalent diabetes at baseline. Individuals whose DNA was not available or in whom genotyping did not succeed were 5.8 years older and contained 8.5% more women than the successfully genotyped group. This is explained by the fact that mostly elderly women in nursing homes did not provide DNA material for the study at baseline. Still, the genotyped and non-genotyped groups had similar distributions of BMI, waist circumference and presence of type 2 diabetes.

Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Incident cases with type 2 diabetes were significantly younger, had higher BMI and waist circumference, lower HDL-cholesterol and more often hypertension than individuals without type 2 diabetes. As expected, prevalent cases were significantly older at baseline compared with incident cases (73.5 ± 0.35 vs 68.1 ± 0.32 years, p < 0.001) and people without diabetes (73.5 ± 0.35 vs 69.0 ± 0.13 years, p < 0.001). They were excluded from further analyses.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of all genotyped participants, participants without diabetes and incident cases of type 2 diabetes

| Characteristic | All participants (n = 6,320) | Individuals without type 2 diabetes (n = 5,080) | Incident cases with type 2 diabetes (n = 582) | p valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 69.3 ± 0.11 | 69.0 ± 0.13 | 68.1 ± 0.32 | 0.02 |

| Men (%) | 40.6 | 40.5 | 44.0 | 0.10 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.3 ± 0.05 | 26.0 ± 0.05 | 28.0 ± 0.16 | <0.001 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 90.5 ± 0.15 | 89.6 ± 0.16 | 94.7 ± 0.46 | <0.001 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 139.4 ± 0.3 | 138.0 ± 0.3 | 143.5 ± 0.9 | <0.001 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 73.8 ± 0.2 | 73.7 ± 0.2 | 75.5 ± 0.5 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension (%) | 33.6 | 30.7 | 46.7 | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/l) | 6.6 ± 0.02 | 6.6 ± 0.02 | 6.6 ± 0.05 | 0.86 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mmol/l) | 1.34 ± 0.005 | 1.37 ± 0.005 | 1.25 ± 0.01 | <0.001 |

| Current smoker (%) | 22.2 | 22.5 | 25.5 | |

| Former smoker (%) | 40.8 | 42.2 | 42.1 | 0.18 |

Continuous data are expressed as means ± SEM

a p value for comparison between incident cases and individuals without diabetes

The polymorphism was in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium in the total population and in individuals without type 2 diabetes (χ 2 < 1.02, df = 2, p > 0.33). In the total population, we found 27.8% heterozygotes for the −803GA polymorphism, while 2.8% were homozygous for the A allele. These percentages were 26.1% and 5.0% and 28.1% and 2.6% in individuals with and without incident type 2 diabetes, respectively; −803AA 5.0% vs 2.6% for incident cases vs individuals without type 2 diabetes, p = 0.01.

The polymorphism was not associated with BMI, total cholesterol or HDL-cholesterol (data not shown).

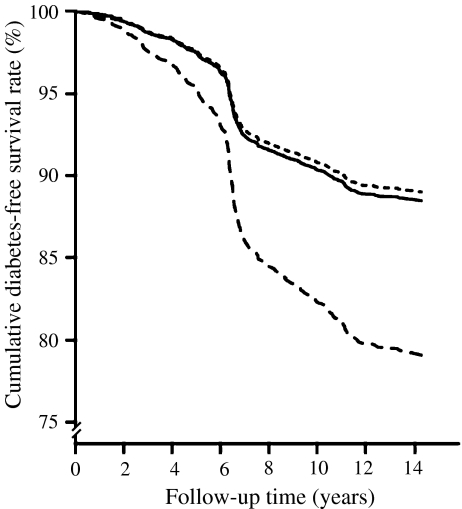

Cox proportional HRs for type 2 diabetes of the −803GA polymorphism Based on the −log-likelihood values and genotype frequencies in individuals with and without type 2 diabetes, the recessive model of inheritance was the best-fitting model. Homozygosity for the A allele was associated with an HR of 1.83 (95% CI 1.26–2.66, p = 0.001) for type 2 diabetes compared with the reference group (−803GG/GA) adjusted for year of birth and sex. Figure 1 shows the effect of the RBP4 −803GA genotypes on type 2 diabetes-free survival in our population. The association remained similar after additional adjustment for BMI (−803AA HR 1.81; 95% CI 1.25–2.64, p = 0.002; Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Diabetes-free survival rate according to RBP4 −803GA genotypes. Solid line, GG; dotted line, GA; dashed line, AA

Table 2.

HRs for type 2 diabetes according to RBP4 −803GA genotype

| Genotype | HR1a | 95% CI | p value | HR2b | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −803GG/GA | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| −803AA | 1.83 | 1.26–2.66 | 0.001 | 1.81 | 1.25–2.64 | 0.002 |

aAdjusted for year of birth and sex

bAdjusted for year of birth, sex and BMI

RE intake, vitamin A plasma levels, the RBP4 polymorphism and risk of type 2 diabetes RE intake corrected for energy intake was not associated with risk of type 2 diabetes (HR 1.0; 95% CI 1.0–1.0, p = 0.16) and did not interact with the RBP4 −803GA polymorphism on type 2 diabetes risk (HR 1.0; 95% CI 0.99–1.00, p for interaction = 0.35).

Vitamin A plasma level measurements were available in a subgroup of 395 genotyped participants. We did not observe significant differences between individuals with and without vitamin A plasma measurements with regards to BMI, waist circumference, sex and type 2 diabetes status. Individuals with measured vitamin A plasma levels were on average 4.3 years younger than those without vitamin A plasma measurements (65.4 ± 0.34 vs 69.7 ± 0.12 years, p < 0.001), which is explained by the fact that they survived and participated until the second follow-up measurement. In this subgroup, the RBP4 polymorphism was not significantly associated with vitamin A plasma levels (Table 3).

Table 3.

Plasma vitamin A levels according to RBP4 −803GA genotype

| −803GA | n | Vitamin A (μmol/l) |

|---|---|---|

| GG | 256 | 1.61 ± 0.02 |

| GA | 129 | 1.59 ± 0.03 |

| AA | 10 | 1.64 ± 0.09 |

Discussion

RBP4 is a recently discovered adipokine that is thought to link adipocyte glucose metabolism to systemic insulin resistance [3]. In the present study, we demonstrated that homozygosity for a promoter variant in the RBP4 gene was associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes at a population-based level. Vitamin A intake was not associated with type 2 diabetes and did not influence the relationship of the polymorphic variant with type 2 diabetes risk. In a subgroup analysis, the RBP4 polymorphism was not significantly associated with vitamin A plasma levels.

Munkhtulga et al. [7] were the first to describe the relationship between RBP4 genetic variants and type 2 diabetes risk. Genotype frequencies for the −803GA polymorphism in this Mongolian population were approximately equal to the genotype frequencies in our white population. Similarly to our results, the −803A allele was associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes. However, a dominant mode of inheritance was found as opposed to our finding of a recessive pattern. The difference in race and differences in exposure to environmental factors between the populations may explain the discrepancy. In two separate studies, white carriers of an RBP4 haplotype had a significantly increased risk of type 2 diabetes [14, 15]. However, the individual RBP4 polymorphisms were not related to risk of type 2 diabetes. In both studies, the haplotype associated with increased risk contained the −803G allele. This seems to contradict our findings, but the associated haplotype was not determined by the −803GA variant. The majority of the haplotypes found (four out of five) contained the −803G allele and were not associated with an increased risk, which makes it unlikely that the G allele contributed to the observed effect. The relatively small sample size of the study by Craig et al. [14] and the presence of considerably younger controls than cases in the study by Kovacs et al. [15] might have hidden the effect of the individual polymorphism. Hence, the findings in our large follow-up study do not necessarily contradict the two previous case–control studies: multiple RBP4 variants may affect type 2 diabetes risk, including variants captured by the haplotypes described in the other references [14, 15], or by the −803GA polymorphism itself.

Since RBP4 is the only known retinol transport protein, a retinol-dependent mechanism underlying its effect on type 2 diabetes risk seems a reasonable assumption. Within tissues, retinol is activated to retinoic acid isomers, which have a wide array of pleiotropic effects through interaction with retinoid acid X receptors (RXRs) and retinoic acid receptors [16], regulating transcription of over 300 target genes [17]. Consistent with a retinol-dependent mechanism Yang et al. [3] found that RBP4 increased PEPCK expression in mouse liver and cultured hepatocytes. PEPCK is a gluconeogenic enzyme and retinoids regulate its transcription [18]. All retinoids in the body originate from the diet [19, 20]. We did not find an association of retinol intake with type 2 diabetes risk. Conflicting results concerning this relationship have been published [21–25]. We did not observe interaction between retinol intake and the RBP4 polymorphism on type 2 diabetes risk, nor did we find an association of the polymorphism with vitamin A plasma levels. However, since the effect on type 2 diabetes risk was confined to the −803A homozygotes and the analyses with vitamin A plasma levels contained only a small number of −803A homozygotes (n = 10), these results should be interpreted with caution. Compared with the other genotypes, the −803A homozygotes had a slightly higher mean plasma vitamin A level, although not significant. Therefore we cannot exclude the possibility that a retinol-dependent mechanism underlies the effect on type 2 diabetes risk. Moreover, the relationship between metabolites of retinol and insulin sensitivity may be complex, as some retinoic acids are thought to cause insulin resistance [26, 27], whereas others seem protective through RXR–peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ-activated pathways [28]. Based on our results we cannot exclude that RBP4 alters the amount of specific retinoic acid isomers locally or systemically. However, a number of retinol-independent mechanisms may operate: RBP4 may increase type 2 diabetes risk by binding of cell surface receptors [29, 30], such as megalin and Stra6. Recently, it was shown that RBP4 can directly affect insulin signalling by blocking the insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of IRS-1 [31]. Furthermore, RBP4 may modulate transthyretin function. Transthyretin was recently shown to be involved in beta cell stimulus–secretion coupling [32, 33].

The relationship between genetic variation in the RBP4 gene and type 2 diabetes had not previously been investigated prospectively at a population-based level. We identified all incident cases of type 2 diabetes in this our large population-based study during a long period of follow-up. The availability of data on retinol intake in all individuals and vitamin A plasma levels in a subgroup allowed us to investigate potential associations and interactions between RBP4 genetic variation and these parameters. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine this interaction.

In a previous study −803GA polymorphism was identified as a functional variant that affects HNF1α binding, RBP4 transcription efficiency and RBP4 plasma levels. Unfortunately, RBP4 plasma levels in the Rotterdam Study are not available because of limitations in sample availability and lack of a readily available and reliable method to measure these levels in large populations and people with insulin resistance [34]. Kovacs et al. did not find an effect of the −803GA polymorphism on serum RBP4 levels in a case–control study [15]. Future studies are needed to obtain insight in the relationship between RBP4 serum levels and the genetic variation in the RBP4 gene.

In conclusion, we have shown prospectively that a promoter polymorphism in the RBP4 gene is associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes in the Rotterdam population. Along with previous functional data our finding increases the confidence that the promoter polymorphism is a causal variant. Dietary intake of retinol did not influence type 2 diabetes risk or the association of the RBP4 polymorphism with type 2 diabetes risk. Moreover, the RBP4 polymorphism was not significantly associated with circulating vitamin A levels. However, we could not exclude a retinol-dependent mechanism underlying the association with type 2 diabetes.

Acknowledgements

The Rotterdam Study is supported by the Erasmus Medical Center and Erasmus University Rotterdam; the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research; the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw); the Research Institute for Diseases in the Elderly; the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science; the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sports; the European Commission; and the Municipality of Rotterdam.

Duality of interest

The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Abbreviations

- HNF1α

hepatic nuclear factor 1α

- PEPCK

phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase

- RBP4

retinol-binding protein 4

- RE

retinol equivalent

- RXR

retinoid acid X receptor

References

- 1.Stumvoll M, Goldstein BJ, van Haeften TW. Type 2 diabetes: principles of pathogenesis and therapy. Lancet. 2005;365:1333–1346. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)61032-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hutley L, Prins JB. Fat as an endocrine organ: relationship to the metabolic syndrome. Am J Med Sci. 2005;330:280–289. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200512000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang Q, Graham TE, Mody N, et al. Serum retinol binding protein 4 contributes to insulin resistance in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2005;436:356–362. doi: 10.1038/nature03711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quadro L, Blaner WS, Salchow DJ, et al. Impaired retinal function and vitamin A availability in mice lacking retinol-binding protein. EMBO J. 1999;18:4633–4644. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.17.4633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shepherd PR, Kahn BB. Glucose transporters and insulin action—implications for insulin resistance and diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:248–257. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907223410406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graham TE, Yang Q, Bluher M, et al. Retinol-binding protein 4 and insulin resistance in lean, obese, and diabetic subjects. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2552–2563. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Munkhtulga L, Nakayama K, Utsumi N, et al. Identification of a regulatory SNP in the retinol binding protein 4 gene associated with type 2 diabetes in Mongolia. Hum Genet. 2007;120:879–888. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0264-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hofman A, Breteler MM, van Duijn CM, et al. The Rotterdam Study: objectives and design update. Eur J Epidemiol. 2007;22:819–829. doi: 10.1007/s10654-007-9199-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med. 1998;15:539–553. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199807)15:7<539::AID-DIA668>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anonymous Report of the expert committee on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:1183–1197. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.7.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klipstein-Grobusch K, den Breeijen JH, Goldbohm RA, et al. Dietary assessment in the elderly: validation of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1998;52:588–596. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beemster CJM, Stichting NEVO. Dutch food composition table. The Hague: Netherlands Bureau of Nutrition Education; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Catignani GL. An HPLC method for the simultaneous determination of retinol and alpha-tocopherol in plasma or serum. Methods Enzymol. 1986;123:215–219. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(86)23025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Craig RL, Chu WS, Elbein SC. Retinol binding protein 4 as a candidate gene for type 2 diabetes and prediabetic intermediate traits. Mol Genet Metab. 2007;90:338–344. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kovacs P, Geyer M, Berndt J, et al. Effects of genetic variation in the human retinol binding protein-4 gene (RBP4) on insulin resistance and fat depot-specific mRNA expression. Diabetes. 2007;56:3095–3100. doi: 10.2337/db06-1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chambon P. A decade of molecular biology of retinoic acid receptors. FASEB J. 1996;10:940–954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gudas LJ. Retinoids, retinoid-responsive genes, cell differentiation, and cancer. Cell Growth Differ. 1992;3:655–662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGrane MM. Vitamin A regulation of gene expression: molecular mechanism of a prototype gene. J Nutr Biochem. 2007;18:497–508. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodman DS. Overview of current knowledge of metabolism of vitamin A and carotenoids. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1984;73:1375–1379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goodman DS. Vitamin A and retinoids in health and disease. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:1023–1031. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198404193101605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sasaki H, Iwasaki T, Kato S, Tada N. High retinol/retinol-binding protein ratio in noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Am J Med Sci. 1995;310:177–182. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199511000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ylonen K, Alfthan G, Groop L, Saloranta C, Aro A, Virtanen SM. Dietary intakes and plasma concentrations of carotenoids and tocopherols in relation to glucose metabolism in subjects at high risk of type 2 diabetes: the Botnia Dietary Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:1434–1441. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.6.1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ford ES, Will JC, Bowman BA, Narayan KM. Diabetes mellitus and serum carotenoids: findings from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149:168–176. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shoff SM, Mares-Perlman JA, Cruickshanks KJ, Klein R, Klein BE, Ritter LL. Glycosylated hemoglobin concentrations and vitamin E, vitamin C, and beta-carotene intake in diabetic and nondiabetic older adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993;58:412–416. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/58.3.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Basu TK, Tze WJ, Leichter J. Serum vitamin A and retinol-binding protein in patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989;50:329–331. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/50.2.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koistinen HA, Remitz A, Gylling H, Miettinen TA, Koivisto VA, Ebeling P. Dyslipidemia and a reversible decrease in insulin sensitivity induced by therapy with 13-cis-retinoic acid. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2001;17:391–395. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodondi N, Darioli R, Ramelet AA, et al. High risk for hyperlipidemia and the metabolic syndrome after an episode of hypertriglyceridemia during 13-cis retinoic acid therapy for acne: a pharmacogenetic study. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:582–589. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-8-200204160-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kliewer SA, Xu HE, Lambert MH, Willson TM. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: from genes to physiology. Recent Prog Horm Res. 2001;56:239–263. doi: 10.1210/rp.56.1.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sivaprasadarao A, Findlay JB. The interaction of retinol-binding protein with its plasma-membrane receptor. Biochem J. 1988;255:561–569. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blaner WS. STRA6, a cell-surface receptor for retinol-binding protein: the plot thickens. Cell Metab. 2007;5:164–166. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ost A, Danielsson A, Liden M, Eriksson U, Nystrom FH, Stralfors P. Retinol-binding protein-4 attenuates insulin-induced phosphorylation of IRS1 and ERK1/2 in primary human adipocytes. FASEB J. 2007;21:3696–3704. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8173com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Monaco HL, Rizzi M, Coda A. Structure of a complex of two plasma proteins: transthyretin and retinol-binding protein. Science. 1995;268:1039–1041. doi: 10.1126/science.7754382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Refai E, Dekki N, Yang SN, et al. Transthyretin constitutes a functional component in pancreatic beta-cell stimulus-secretion coupling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17020–17025. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503219102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Graham TE, Wason CJ, Bluher M, Kahn BB. Shortcomings in methodology complicate measurements of serum retinol binding protein (RBP4) in insulin-resistant human subjects. Diabetologia. 2007;50:814–823. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0557-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]