Abstract

External guide sequences (EGSs) targeting virulence genes from Yersinia pestis were designed and tested in vitro and in vivo in Escherichia coli. Linear EGSs and M1 RNA-linked EGSs were designed for the yscN and yscS genes that are involved in type III secretion in Y. pestis. RNase P from E. coli cleaves the messages of yscN and yscS in vitro with the cognate EGSs, and the expression of the EGSs resulted in the reduction of the levels of these messages of the virulence genes when those genes were expressed in E. coli.

Keywords: pathogenic bacteria, random EGSs

INTRODUCTION

Inhibition of expression of genes can be accomplished with the use of external guide sequences (EGSs) and RNase P. EGSs are oligonucleotides that target complementary mRNAs by hydrogen bonding to the target mRNAs, thus making a complex that resembles natural substrates for RNase P (Forster and Altman 1990; Yuan et al. 1992; Guerrier-Takada et al. 1995; Guerrier-Takada and Altman 2000). RNase P recognizes the complex and cleaves the target mRNA, which acts as a 5′-proximal sequence of precursor tRNA, whereas the EGS acts as a 3′-proximal sequence of a precursor tRNA. Different types of EGS have been reported with which target mRNAs were converted into recognizable substrates that are parts of tRNAs (Forster and Altman 1990; Yuan et al. 1992). Since RNase P is an ubiquitous enzyme, studies with EGSs have been performed on genes from bacteria and human tissue culture cells (Guerrier-Takada et al. 1995, 1997; Liu and Altman 1995).

Yersinia pestis is a Gram-negative bacterium that has been responsible for widespread devastation (Black Death). To escape from phagocytic killing of host cells, Y. pestis delivers a set of virulence proteins, called Yops, across the cell membrane. The Yops are the core of the Yersinia pathogenicity arsenal (Cornelis 2000). A set of ysc (Yop secretion) genes encode the proteins of a type III secretion apparatus. The injected Yops inhibit phagocytosis by disturbing events in the host cell response such as actin polymerization and apoptosis (Cornelis 2000).

We targeted two virulence genes, yscN and yscS. The yscN gene encodes a 47.8-kDa protein that contains ATPase activity (Woestyn et al. 1994). The secretion process in Y. pestis absolutely requires YscN, and recently it was reported that YscN recognizes a secretion signal (Sorg et al. 2006). The yscS gene is a component of the type III secretion apparatus (Fields et al. 1994). Here, we show that the EGSs targeting yscN and yscS can inhibit the expression of those Yop secretion genes in vitro and in vivo in Escherichia coli. The methods we describe are useful for testing any virulence gene of pathogenic bacteria in E. coli under safe conditions.

RESULTS

Selection of target sites and design of EGSs against the virulence genes

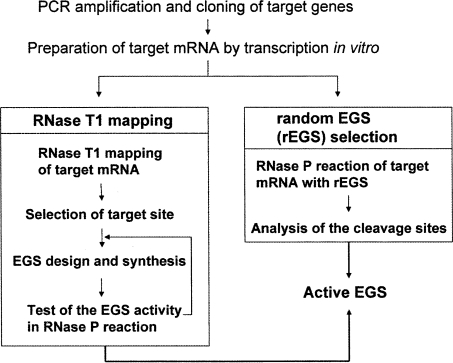

The target sites of EGS were selected by two methods (Fig. 1): cleavage assay by random EGSs (rEGSs), and detailed mapping of accessibility of sites by RNase T1 (Guerrier-Takada and Altman 2000; Lundblad et al. 2008). In a prior study using the rEGS method, we selected an EGS that cleaved at the G+3 position of yscN mRNA (Lundblad et al. 2008). The first nucleotide of the translation start codon of yscN is numbered +1. RNase P could cleave the yscN mRNA at the expected position when a specific EGS derived from the rEGS mixture, named EGS-N3, was added to the reaction in vitro (Lundblad et al. 2008). From the detailed RNase T1 mapping, two additional EGSs targeting G+13 (EGS-N1), in a supposed helical structure, and G+50 (EGS-N2) of yscN mRNA (Fig. 2A), in an internal loop, were designed.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic overview of selection of active EGSs. The accessible region of target mRNA is determined by mild digestion with RNase T1. An EGS targeting the region is then designed and tested. In random EGS selection, the RNase P reaction is performed by using target mRNA and a pool of random EGSs. Through an analysis of the reaction products, the cleavage site for active EGSs can be determined.

FIGURE 2.

Determination of the EGS-targeting sites in the mRNAs. (A) A putative structure of yscN mRNA and RNase T1 susceptible sites. The structure was determined by the Mfold program (Zuker 2003). The cleavages at G sites from a previous report (Lundblad et al. 2008) are indicated for strong signals (filled circles) and weak signals (open circles). (B) Analysis of the cleavage products of 5′ end-labeled yscS mRNA using random EGS and RNase P. rEGSx is a random EGS library with a shortened 3′ end (Lundblad et al. 2008). (Filled triangles) Increasing concentrations of the random EGS mixture (10-, 50-, and 100-fold molar excess to yscS mRNA). (T1) Reaction product of partial RNase T1 digestion, (OH) alkaline ladder, (P) reaction product with E. coli RNase P holoenzyme, (con) untreated RNA sample. (C5) Reaction product with C5 protein. The same yscS mRNA samples were loaded twice on the 8% polyacrylamide/7 M urea gel at different points of time. (pSupS1) Internally labeled SupS1 precursor tRNA that was used as a substrate for confirming the activity of the RNase P fraction, (arrows) cleavage sites by RNase P. Note in the lefthand part of the figure, which has more resolution, the bottom band cleaved by RNase P has moved off the gel. (C) A putative structure of yscS mRNA and RNase T1 susceptible sites. (Circles) Cleavages within the coding sequence.

The rEGS method was also used to determine accessible and cleavable sites of yscS mRNA, but we could not identify a candidate site in the gel that was used to analyze the reaction, probably because only the first few hundred nucleotides of the target mRNA were used as a potential substrate. A larger test fragment that might have contained an accessible structure could have made this possible. However, RNase P alone cuts the yscS mRNA (Fig. 2B). The addition of a random EGS mixture led to reduction of the cleavage, and in this case the rEGS seemed to act as a competitor of the RNase P reaction. We designed two EGSs targeting G+44 (EGS-S1) and G+73 (EGS-S2) of yscS mRNA based on RNase T1 mapping. We selected G+44 because the region was not only near an RNase T1 cleavage site, but RNase P alone seemed to access the region. The G+73 position is in a small internal loop in the putative structure (Fig. 2C). Both linear EGSs and an M1 RNA-linked EGS (M1-EGS) were designed for each case using this information on accessible sites provided by the RNase T1 method (Guerrier-Takada and Altman 2000).

EGS activities in vitro

RNase P from E. coli could cleave the yscN mRNA with either EGS-N1 or EGS-N2 in PA buffer (see Materials and Methods). The cleavage at the predicted positions could be seen in the case of either linear EGS or M1-EGS (Fig. 3A,B). The cleavage sites were confirmed by comparing them with partial RNase T1 cleavage products and a partial alkaline ladder (data not shown). When RNase P alone was used for the reaction without the addition of a specific EGS, additional cleavages appeared. These regions might have secondary structure that renders them substrates for RNase P.

FIGURE 3.

RNase P cleavage reactions with the EGS in vitro. (A) RNase P reaction on yscN mRNA using EGS-N1. The reaction was performed as described in the Materials and Methods. (M1) Reaction product with M1 RNA in PA100 buffer. (E) Linear EGS, (M1E) M1-EGS, (ME2) 50-fold molar excess of M1-EGS. (Arrows) 5′- and 3′-proximal products of cleavage. The RNA samples were separated on a 5% polyacrylamide/7 M urea gel. (B) RNase P reaction on yscN mRNA using EGS-N2. (C) RNase P reaction on yscS mRNA using EGS-S1. (D) RNase P reaction on yscS mRNA using EGS-S2. No specific cleavage with the EGS can be seen here.

For yscS mRNA, the same reactions were performed. EGS-S1 successfully guided RNase P to cleave yscS mRNA, whereas EGS-S2 did not produce the specific cleavage (Fig. 3C,D).

The EGS activities in vivo

To test further the activity of EGSs in E. coli that had previously shown activities in vitro, we constructed an assay system based on the pUC19 plasmid (Fig. 4A; see Materials and Methods). In this system, both the target mRNA and the EGS are transcribed in the same plasmid using different promoters. BL21(DE3) was transformed with the plasmid, and the total RNAs were collected and analyzed with Northern blots. We inactivated the lacZ promoter on the plasmid by mutagenesis because IPTG added to induce the expression of EGS might affect the expression of the target mRNA. An active fragment of the β-galactosidase gene was attached to the lacZ promoter. We confirmed that in the cells that contained the mutated plasmid, pMlac, the β-galactosidase activity substantially decreased when IPTG was added (data not shown).

FIGURE 4.

Analysis of EGS activity in vivo. (A) Schematic representation of a plasmid for expressing target mRNAs and EGSs. (PM1) rnpB promoter of E. coli, (PT7) T7 promoter, (M1T) rnpB transcription terminator, (HH) sequence of hammerhead ribozyme, (T7T) T7 transcription terminator. The NdeI site was no longer available after completing the construction of the plasmid. (B) Northern analysis of yscN mRNA with EGS expression. RNAs were prepared from E. coli cells either with (+) or without (−) the addition of IPTG for induced expression of the EGS listed. The RNA samples were separated on a 2% agarose gel. (Linear EGS+T7T) Transcript extending to the T7 transcription terminator of the plasmid containing the linear EGS sequence, (M1-EGS+T7T) transcript extending to the T7 transcription terminator of the plasmid containing the M1-EGS sequence. 5S rRNA was probed with 5′-end-labeled 5S1 on the same membrane. This is an example of gene expression independent of EGS expression. (C) Northern analysis of yscS mRNA with EGS expression.

When IPTG (2 mM) was added to the medium in which E. coli grows to induce the expression of the linear EGS targeting G+13 (RNase T1-designed), the yscN mRNA decreased to 37% compared to that without the EGS (Fig. 4B). In the absence of IPTG, the yscN mRNA decreased to 39% of control in the case of linear EGS-N1. This may arise from the fact that the T7 promoter is somewhat leaky, which is supported by the fact that the EGS bands were seen in the lane without IPTG (Fig. 4B). M1-EGS was also effective, but the effect was weaker than the stem EGS, i.e., up to 38% reduction of the target mRNA (Fig. 4B) in the absence of IPTG.

EGS-N3 that targets G+3 was also tested. The G+3 EGS was selected from the rEGS method, and the activity in vitro was determined in a previous report (Lundblad et al. 2008). The linear EGS reduced the expression of yscN mRNA to 68% of control. The effect of M1-EGS was very low and was not statistically different from the control. We previously had noted that frequently M1-EGS constructs were less active than linear EGS constructs in E. coli (C. Guerrier-Takada, pers. comm.). We note that the values of inhibition of mRNAs were virtually the same with IPTG absent or present. We ascribe this result to leakiness of the T7 promoter, as stated above. The values of inhibition of gene expression from Northern analysis are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

The effect of EGSs on yscN and yscS mRNAs

Two major bands of yscN mRNA were detected on membranes that were probed in Northern blots. Considering the mobility of the bands, the upper band is likely to be the transcript that resulted from transcription termination at the rnpB terminator. The lower band is probably from an earlier termination of transcription before the rnpB terminator, or possibly cleavage of the longer transcript by the hammerhead ribozyme at the end of the EGS sequence in E. coli. All these bands were considered when calculating the amounts of yscN mRNA.

The Northern blots for yscS mRNA with EGS-S1 as an agent inside the cell were also evaluated. Linear EGS-S1 was effective in reducing the amount of yscS mRNA to 40% of the control (Fig. 4C). In this case, M1-EGS-S1 reduced the amount of yscS mRNA to 43% of the control (Fig. 4C). The latter results were obtained in the absence of IPTG. In the presence of IPTG, the values were similar but somewhat higher than in the absence of IPTG. Most of the EGSs contained the T7 transcription terminator, implying that the hammerhead enzyme did not work well on the primary transcript (Fig. 4C).

DISCUSSION

We designed EGSs targeting virulence genes of Y. pestis They successfully inhibited the expression of the target genes in vitro and in vivo. Although the EGSs worked well in E. coli, further studies are necessary in Y. pestis to see whether they would retain the inhibitory activity on gene expression. For this, it would be necessary to construct an EGS-expressing plasmid in Y. pestis. The PBAD promoter could be a candidate for transcription of the EGS because the promoter is available in Y. pestis (Nilles et al. 1998). For the formation of the 3′ end, the hammerhead ribozyme that we used here can be used in Y. pestis because it works in a protein-independent manner (Forster and Symons 1987). One advantage of using an RNase P-derived gene regulating system is that RNase P is ubiquitous among all kingdoms of life, and, therefore, the EGS technology should also work in Y. pestis.

It has been reported that extended sequences at the 3′ end of tRNA reduce the cleavage activity of RNase P (Altman et al. 1987). For example, the rate of cleavage for a substrate containing a 46-nucleotide (nt) extra sequence at the 3′ end of precursor tRNA was 1% of the precursor to wild-type tRNA. The primary transcript from the T7 promoter in the plasmid has ∼153 nt of extra sequence at the 3′ end of EGS. Therefore, the cleavage at the 3′ end of EGS sequence by a hammerhead ribozyme would be important for the activity of EGS, especially for linear EGSs. For the linear EGS against yscN mRNA, most of the EGS-N3 was present as the uncleaved form (Fig. 4B). This could explain why the linear EGS-N3 showed relatively low activity compared with the EGS-N1.

A previous study showed that an EGS against a pathogenic gene, invC, encoding an ATPase from Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, could inhibit the invasion of mammalian cells by the bacterium, although the inhibition was less compared with that in a knockdown study (McKinney et al. 2004). InvC is also essential for the type III secretion mechanism, probably by providing the ability of virulence proteins to pass through a membrane channel. If the EGSs against yscN and yscS are effective for inhibiting the virulence of Y. pestis, other genes encoding the virulence type III protein secretion system could be selected as good targets for EGSs because this system has been identified in many animal and plant pathogens (Hueck 1998).

The rEGS method enables the rapid identification of accessible and cleavable sites of target mRNA (Lundblad et al. 2008). In some cases, such as yscS mRNA, the selection of an rEGS was not feasible with our methods. We designed EGSs by using the older RNase T1 mapping method, and these EGSs worked successfully in vitro and in vivo. The two complementary methods are useful to get candidate sites for targeting of mRNAs of pathogenic bacteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of target mRNAs

Restricted genomic DNA of Yersinia pestis was obtained from the Armed Forced Institute, Washington, DC. The template for yscN mRNA was prepared as described previously (Lundblad et al. 2008). The plasmid was named pBSK-yscN, which contained the region from −29 to +1352 of yscN. The first nucleotide of translation start codon of yscN is numbered +1. The template for yscS mRNA was prepared by PCR of the Y. pestis DNA with primers of YPF1 (5′-cggggtaccgacacgactcacgcatg-3′) and YPR2 (5′-ccggaattcgcgatgagtaaaggagcagc-3′). The PCR product that was cut with KpnI and EcoRI was cloned into pBluescript II SK(+) plasmid. The plasmid was named pBSK-yscS.

The PvuII–BstNI fragment of pBSK-yscN and the PvuII–HindIII fragment of pBSK-yscS were used as the templates for yscN and yscS mRNA, respectively. The transcripts, 179 nt in length for yscN mRNA and 180 nt for yscS mRNA, were obtained by in vitro transcription using T7 RNA polymerase (Lundblad et al. 2008). They contained the extra nucleotides originated from pBluescript II SK(+) as well as the corresponding coding sequences. For internally labeled transcripts, [α-32P]GTP (Amersham) was used during the transcription reaction. For the mapping of cleavage sites, transcripts were labeled at the 5′ end using [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs).

Mapping of accessible sites in target mRNAs

A partial RNase T1 reaction was performed as previously described (Guerrier-Takada and Altman 2000). After the reaction, the RNAs were separated on an 8% polyacrylamide sequencing gel that contained 7 M urea. Partial alkaline ladder digests were carried out (Lundblad et al. 2008). Cleavage sites were determined by comparing partial RNase T1 cleavage products to partial alkaline ladder results. The rEGS assay for yscS mRNA was performed as described previously (Lundblad et al. 2008). The yeast suppressor precursor tRNASer (SupS1) was internally labeled with [α-32P]GTP and used as a substrate in control reaction (Ko and Altman 2007).

Preparation of EGS against target mRNAs

The specific EGS was designed based on the rEGS assay according to previous reports (Guerrier-Takada and Altman 2000; Lundblad et al. 2008). For EGS-N1, YN1UP (5′-gtgaggtatctgatcaccag-3′) and YN1DW (5′-gtgacctggtgatcagatacctcactgca-3′) were phosphorylated at their 5′ ends and then annealed together by heating for 10 min at 65°C and cooling down slowly. The annealed product was subcloned into the region between PstI and BstEII of pUCT7/AEFRNAHHT7T (for linear EGS) or pUC/T7M1AEFRNAHHT7T (for M1-EGS). The resultant plasmids, pUCT7/yscN1HHT7T and pUC/T7M1yscN1HHT7T, were used as templates for transcription after being cut with BstEII and PvuII. For EGS-N2, EGS-S1, and EGS-S2, the same method was used except the set of oligonucleotides. Oligonucleotides of YN2UP (5′-ggattaggcggctacaccag-3′) and YN2DW (5′-gtgacctggtgtagccgcctaatcctgca-3′) were used for EGS-N2. YS1UP (5′-gactagcaccagccaccag-3′) and YS1DW (5′-gtgacctggtggctggtgctagtctgca-3′) were used for EGS-S1. YS2UP (5′-ggcagccactaacacaccag-3′) and YS2DW (5′-gtgacctggtgtgttagtggctgcctgca-3′) were used for EGS-S2.

EGS activity assays in vitro

EGS activity assays were performed according to a previous report (Lundblad et al. 2008). The EGS in 100-, 50-, or 10-fold molar excess was incubated with 10 nM of 5′ end-labeled or internally labeled target mRNAs in PA buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NH4Cl) for 5 min at room temperature. Subsequently, 10 nM of M1 RNA and 100 nM of C5 protein were added to the mixture and further incubated for 30 min at 37°C. For reactions with M1 RNA alone, 100 nM of M1 RNA was used in PA100 buffer (PA buffer that contained 100 mM MgCl2). Reactions in a 10-μL volume were performed for 30 min at 37°C and terminated by adding 10 μL of 10 M urea/10% phenol solution. The product was separated on 5% polyacrylamide/7 M urea gels.

Construction of plasmids for the EGS activity assay in E. coli

To test the activity of the specific EGS in vivo, a plasmid, based on pUC19, was designed as shown in Figure 4A. The rnpB promoter and terminator of E. coli were adopted for transcription of the target mRNA. For the transcription of the EGS, a T7 promoter and terminator were used. Between the EGS and T7 terminator sequences, the core sequence of a hammerhead ribozyme was inserted. Once the RNA is transcribed, the hammerhead ribozyme cuts the transcript producing the EGS. Since the plasmid contains the lac promoter downstream of the EGS-expressing unit, and IPTG, when added, also induces the transcription of the promoter, the lac promoter sequence was mutated to inactivate its transcription activity. A T−36 to C change was introduced in the −35 region of lacZ on the plasmid in order to inactivate the transcription from the lacZ promoter by making a StuI site. To do this, site-directed mutagenesis was performed by using the QuickChange kit (Stratagene) as well as the primers of lacM1 (5′-ggcaccccaggccttacactttatgcttcc-3′) and lacM2 (5′-ggaagcataaagtgtaaggcctggggtgcc-3′). To test the inactivation of the lac promoter, DH5α containing the mutated plasmid, pMlac, was cultured on a plate with X-gal and IPTG. The color of the colonies was a less intense blue compared with that of colonies that contained the original plasmid, pUC19, implying that the transcriptional activity of the mutated lac promoter substantially decreased (data not shown). BL21(DE3) was transformed with the plasmid, and IPTG was added to induce expression of the EGS.

Target mRNAs were subcloned into the region of pKB283 between the rnpB promoter and its transcriptional terminator (Guerrier-Takada and Altman 2000). The pBSK-yscN was cut with XhoI, blunt-ended with Klenow fragment (New England Biolabs), and cut with EcoRI. The fragment was subcloned into the SmaI–EcoRI site of pUC19 to get a BamHI site at the 5′ end of the yscN fragment. The plasmid was cut with NlaIV and BamHI, and the fragment was subcloned into the BamHI–SnaBI site of pKB283.

After subcloning it, the resultant plasmid was cut with HindIII, blunt-ended with Klenow fragment, and cut again with EcoRI. The fragment was subcloned into the EcoRI–NdeI site of pMlac, in which the NdeI site was blunt-ended by treating with Klenow fragment. The region containing the EGS fraction was prepared by cutting the same plasmid as the one used for preparation of EGS in vitro with EcoRI and HindIII, and the fragment was subcloned into the EcoRI–HindIII site of pMlac at the same time as the subcloning of target mRNA fragments. The resultant plasmid was named pMlac-yscN-EGS.

For yscS mRNA, pBSK-yscS was cut with KpnI and EcoRI, and the fragment was subcloned into the same sites of pMlac. The resultant plasmid was cut with BglI, blunt-ended with Klenow fragment, and then cut with BamHI. The fragment containing yscS sequence was subcloned into the BamHI–SnaBI site of pKB283. For the rest of the procedure, the same method as for yscN mRNA was used.

Northern analysis

Freshly transformed cells were used for Northern analysis. BL21(DE3) competent cells (150 μL) were mixed with 0.1 μg of the appropriate plasmid and transformed for 90 sec at 42°C. The transformed cells were cultured overnight at 37°C on an LB plate with 100 μg/mL ampicillin. It is essential to use freshly transformed cells: When the cells were cultured from the glycerol stock of transformed cells, the expression of EGS was poor very often. A colony was picked from the LB plate and was cultured overnight in LB media containing 100 μg/mL carbenicillin and 0.5% glucose at 37°C.

The overnight culture was diluted 1:50 and incubated at 37°C to OD600 = 0.6. The cells were split into two tubes, and 2 mM IPTG was added into one of the tubes. The cells were further incubated for 1.5 h, and total RNA was prepared as described previously (Baer et al. 1990). The RNAs (4 μg) were separated on a 2% agarose gel.

Northern blot analysis was performed as described previously (Guerrier-Takada et al. 1995). Oligonucleotides of YN-N2 (5′-gccatgacgaatatgatgagg-3′), YN1DW (5′-gtgacctggtgatcagatacctcactgca-3′), YN3DW (5′-gtgacctggtgctctcactagatcctgca-3′), YS-N1 (5′-gataccaaagttcctaccaccg-3′), YS1DW (5′-gtgacctggtggctggtgctagtctgca-3′) and 5S1 (5′-taccatcggcgctacggcgtttcacttc-3′) were labeled at their 5′ ends by using [γ-32P]ATP and were then used as probes for yscN mRNA, EGS-N1, EGS-N3, yscS mRNA, EGS-S1, and 5S rRNA, respectively.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the members of our laboratory for helpful discussions. This research was supported by Defense Threat Reduction Agency Grant W81XWH-06-2-0066.

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.1120508.

REFERENCES

- Altman S., Baer M., Gold H., Guerrier-Takada C., Kirsebom L., Lawrence N., Lumelsky N., Vioque A. Cleavage of RNA by RNase P from Escherichia coli . In: Inouye M., Dudock B., editors. Molecular biology of RNA: New perspectives. Academic Press; New York: 1987. pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Baer M.F., Arnez J.G., Guerrier-Takada C., Vioque A., Altman S. Preparation and characterization of RNase P from Escherichia coli . Methods Enzymol. 1990;181:569–582. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)81152-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelis G.R. Molecular and cell biology aspects of plague. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2000;97:8778–8783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.8778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields K.A., Plano G.V., Straley S.C. A low-Ca2+ response (LCR) secretion (ysc) locus lies within the lcrB region of the LCR plasmid in Yersinia pestis . J. Bacteriol. 1994;176:569–579. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.3.569-579.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster A.C., Altman S. External guide sequences for an RNA enzyme. Science. 1990;249:783–786. doi: 10.1126/science.1697102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster A.C., Symons R.H. Self-cleavage of plus and minus RNAs of a virusoid and a structural model for the active sites. Cell. 1987;49:211–220. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90562-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrier-Takada C., Altman S. Inactivation of gene expression using ribonuclease P and external guide sequences. Methods Enzymol. 2000;313:442–456. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)13028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrier-Takada C., Li Y., Altman S. Artificial regulation of gene expression in Escherichia coli by RNase P. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1995;92:11115–11119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrier-Takada C., Salavati R., Altman S. Phenotypic conversion of drug-resistant bacteria to drug sensitivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1997;94:8468–8472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hueck C.J. Type III protein secretion systems in bacterial pathogens of animals and plants. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1998;62:379–433. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.2.379-433.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko J.H., Altman S. OLE RNA, an RNA motif that is highly conserved in several extremophilic bacteria, is a substrate for and can be regulated by RNase P RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2007;104:7815–7820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701715104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F., Altman S. Inhibition of viral gene expression by the catalytic RNA subunit of RNase P from Escherichia coli . Genes & Dev. 1995;9:471–480. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.4.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundblad E.W., Xiao G., Ko J.H., Altman S. Rapid selection of accessible and cleavable sites in RNA by E. coli RNase P and random external guide sequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008;105:2354–2357. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711977105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney J.S., Zhang H., Kubori T., Galán J.E., Altman S. Disruption of type III secretion in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium by external guide sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:848–854. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilles M.L., Fields K.A., Straley S.C. The V antigen of Yersinia pestis regulates Yop vectorial targeting as well as Yop secretion through effects on YopB and LcrG. J. Bacteriol. 1998;180:3410–3420. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.13.3410-3420.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorg J.A., Blaylock B., Schneewind O. Secretion signal recognition by YscN, the Yersinia type III secretion ATPase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2006;103:16490–16495. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605974103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woestyn S., Allaoui A., Wattiau P., Cornelis G.R. YscN, the putative energizer of the Yersinia Yop secretion machinery. J. Bacteriol. 1994;176:1561–1569. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.6.1561-1569.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y., Hwang E.S., Altman S. Targeted cleavage of mRNA by human RNase P. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1992;89:8006–8010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.17.8006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuker M. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3406–3415. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]