Abstract

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is a kinetically and thermodynamically stable molecule. It is easily formed by the oxidation of organic molecules, during combustion or respiration, but is difficult to reduce. The production of reduced carbon compounds from CO2 is an attractive proposition, because carbon-neutral energy sources could be used to generate fuel resources and sequester CO2 from the atmosphere. However, available methods for the electrochemical reduction of CO2 require excessive overpotentials (are energetically wasteful) and produce mixtures of products. Here, we show that a tungsten-containing formate dehydrogenase enzyme (FDH1) adsorbed to an electrode surface catalyzes the efficient electrochemical reduction of CO2 to formate. Electrocatalysis by FDH1 is thermodynamically reversible—only small overpotentials are required, and the point of zero net catalytic current defines the reduction potential. It occurs under thoroughly mild conditions, and formate is the only product. Both as a homogeneous catalyst and on the electrode, FDH1 catalyzes CO2 reduction with a rate more than two orders of magnitude faster than that of any known catalyst for the same reaction. Formate oxidation is more than five times faster than CO2 reduction. Thermodynamically, formate and hydrogen are oxidized at similar potentials, so formate is a viable energy source in its own right as well as an industrially important feedstock and a stable intermediate in the conversion of CO2 to methanol and methane. FDH1 demonstrates the feasibility of interconverting CO2 and formate electrochemically, and it is a template for the development of robust synthetic catalysts suitable for practical applications.

Keywords: electrocatalysis, formate dehydrogenase, formate oxidation, protein film voltammetry, carbon dioxide reduction

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is a kinetically and thermodynamically stable molecule that is difficult to chemically activate. As the unreactive product of the combustion of carbon-containing molecules, such as fossil fuels, and biological respiration, it is accumulating in the atmosphere and is a major cause of concern in climate-change scenarios (1, 2). Consequently, catalysts that are able to sequester CO2 from the atmosphere rapidly and efficiently, to generate reduced carbon compounds for use as fuels or chemical feedstocks, have long been sought after. Organometallic complexes that insert CO2 into an M–H bond and the use of supercritical CO2 to facilitate its hydrogenation are two promising approaches to the development of a homogeneous catalytic process (3–5). Extensive efforts to develop electrode materials for the direct, electrochemical reduction of CO2 have been made also, but so far, they require the application of extreme potentials (are inefficient energetically) or they are nonspecific and produce mixtures of products (4, 6, 7). An efficient and specific method for reducing CO2 electrochemically has obvious applications in a future energy economy based on the cyclic reduction and oxidation of simple carbon compounds, as an alternative to the well-known hydrogen economy model.

Here, we focus on the two-electron reduction of CO2 to formate (see Fig. 1). Formate is the first stable intermediate in the reduction of CO2 to methanol or methane, but it is increasingly recognized as a viable energy source in its own right. Thermodynamically, formate and hydrogen are oxidized at similar potentials (the reduction potential for the reduction of CO2 to formate is close to that for the reduction of protons to hydrogen, see below), and fuel cells that use formate are being developed (8). It is not possible, at present, to reduce CO2 to formate efficiently and specifically at an electrode surface.

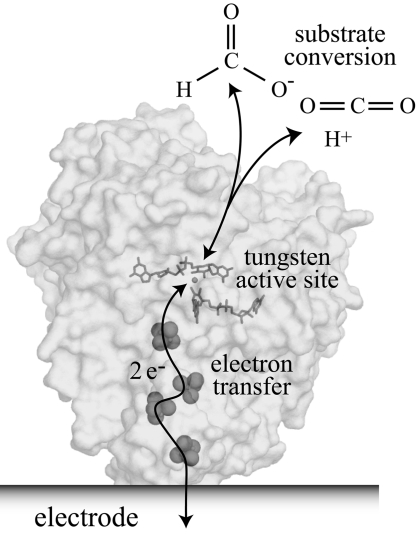

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the electrocatalytic interconversion of CO2 and formate by a formate dehydrogenase adsorbed on an electrode surface. Two electrons are transferred from the electrode to the active site (buried inside the insulating protein interior) by the iron–sulfur clusters, to reduce CO2 to formate, forming a C–H bond. Conversely, when formate is oxidized, the two electrons are transferred from the active site to the electrode. The structure of FDH1 (which contains at least nine iron–sulfur clusters) is not known, so the structure shown is that of the tungsten-containing formate dehydrogenase from Desulfovibrio gigas [PDB ID code 1H0H (12)].

Formate dehydrogenases are enzymes that catalyze the oxidation of formate to CO2. The most common class catalyze the direct transfer of a hydride moiety from formate to NAD(P)+, but it is difficult to drive them in reverse because the reduction potential of NAD(P)+ is more positive than that of CO2 (9). In some prokaryotes, however, the formate dehydrogenases are complex enzymes that contain molybdenum or tungsten cofactors to transfer the electrons from formate oxidation to an independent active site, to reduce quinone, protons, or NAD(P)+ (10–13). These enzymes are suitable for adsorption onto an electrode, so that the electrode accepts the electrons from formate oxidation, and it may also donate electrons and drive CO2 reduction. Therefore, they are potential electrocatalysts for the reduction of CO2 (see Fig. 1). Tungstoenzymes catalyze low-potential reactions (14), so tungsten-containing formate dehydrogenases [in which the tungsten is coordinated by two pyranopterin guanosine dinucleotide cofactors and a selenocysteine (12)] are those most associated with CO2 reduction. Here, we focus on FDH1, one of the tungsten-containing formate dehydrogenases from Syntrophobacter fumaroxidans, an anaerobic bacterium that oxidizes propionate to acetate, CO2, and six reducing equivalents (15). The reducing equivalents are used to reduce protons to hydrogen or to reduce CO2 to formate. During syntrophic growth S. fumaroxidans optimizes its metabolism by transferring the formate (and/or the hydrogen) to its syntrophic partner (16). Therefore, the tungsten-containing formate dehydrogenases of S. fumaroxidans must be both thermodynamically and kinetically efficient, and so they are good candidate electrocatalysts for the electrochemical reduction of CO2.

Results

Molecular Properties of FDH1 from S. fumaroxidans.

FDH1, tungsten-containing formate dehydrogenase 1 isolated from S. fumaroxidans, comprises three different subunits [see supporting information (SI) Figs. S1 and S2]. The C-terminal domain of the largest subunit contains the conserved selenocysteine that ligates the tungstopterin active site (17), and it belongs to a large family of structurally related molybdo- and tungstoenzymes, including nitrate reductase (18), DMSO reductase (19), and the structurally characterized formate dehydrogenases (10–12). Between them, the N-terminal domain of the largest subunit and the other two subunits contain binding motifs for at least nine iron–sulfur clusters (see Fig. S2), deduced from their homology to proteins of known structure, in particular three subunits of the hydrophilic domain of respiratory NADH ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) (20). Despite the conservation of residues that bind (or are predicted to bind) the flavin and NADH in complex I, purified FDH1 does not catalyze the reduction of NAD(P)+ by formate (15). However, it does catalyze the rapid interconversion of formate and CO2 in catalytic activity assays using methyl viologen (MV) as the artificial redox partner; our preparations of FDH1 exhibited turnover rates of up to 3,380 s−1 for formate oxidation at pH 8, and 282 s−1 for CO2 reduction at pH 7.5. Thus, considering FDH1 as a homogeneous catalyst alone, it exhibits a rate of CO2 reduction that is more than two orders of magnitude higher than any known nonbiological catalyst for the same reaction (see below). Note that, for simplicity, we use the term “CO2” to encompass the pH-dependent equilibrium of dissolved CO2, H2CO3, HCO3−, and CO32− formed in aqueous solution under gaseous CO2, or upon the addition of sodium carbonate (21).

FDH1 Adsorbed on an Electrode Surface Catalyzes the Reversible Interconversion of CO2 and Formate.

Fig. 1 illustrates our experimental strategy (22) for the electrochemical interconversion of CO2 and formate. Molecules of FDH1 are adsorbed to a freshly polished pyrolytic graphite edge electrode to activate the surface. When the electrode is placed into an electrochemical cell containing the enzyme's substrates, catalysis can be driven and controlled by applying a potential and quantified by measuring the current flowing. Thus, the catalytic properties and capability of the adsorbed enzyme are defined under precisely controlled conditions. Ideally, substrate supply to the activated surface and electron transfer between the enzyme's active site and the electrode are fast and efficient and do not hinder turnover. Fig. 1 highlights how the many iron–sulfur clusters in FDH1 may enable efficient electron transfer through the insulating protein interior to the buried active site.

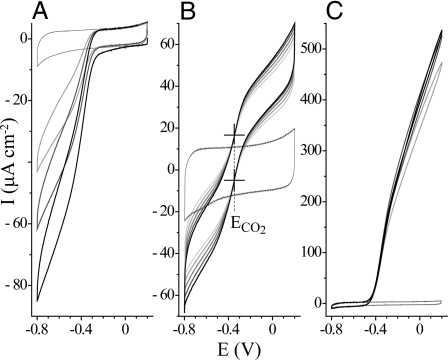

Voltammograms of FDH1 catalyzing the interconversion of formate and CO2 are presented in Fig. 2. Both CO2 reduction and formate oxidation are initiated at approximately −0.4 V, close to the reduction potential (see below), and then their rates increase sharply as the driving forces increase. Qualitatively, the voltammograms resemble those exhibited by Allochromatium vinosum NiFe hydrogenase, a focus of research in the development of biohydrogen fuel cell technology (23). The voltammetric waveshapes display a sigmoidal onset that changes into a linear dependency as the driving force (overpotential) is increased. This reflects the influence of the interfacial electron transfer process that, even at the highest driving force applied, lags behind the rapid active-site turnover (24). CO2 reduction reaches 0.08 mA cm−2 at −0.8 V (pH 5.9), whereas formate oxidation increases to 0.5 mA cm−2 at +0.2 V (pH 8.0) (Fig. 2 A and C).

Fig. 2.

Electrocatalytic voltammograms showing CO2 reduction and formate oxidation by FDH1. Shown are the reduction of 10 mM CO2 (pH 5.9) (A); electrocatalysis in 10 mM CO2 and 10 mM formate (pH 6.4) (B), showing the points of intersection (marked with crosses) that define the reduction potential for the interconversion of CO2 and formate; and the oxidation of 10 mM formate (pH 7.8) (C). The first voltammetric cycles are shown in black, subsequent cycles are in gray; background cycles recorded in the absence of substrate are also shown (gray). Note that the background cycle in B is offset slightly from the catalytic scans because of variation in the electrode capacitance. Substrates were added as sodium formate or sodium carbonate. For A and C, 25 mV s−1, for B, 100 mV s−1; 37°C, electrode rotation 1,000 rpm.

Fig. 2B displays formate oxidation and CO2 reduction in a single experiment. The electrocatalytic activity gradually decreases, because of enzyme desorption or denaturation, so that a potential at which all of the catalytic voltammograms intersect is a potential of zero net catalytic current. Net formate oxidation occurs at all potentials above the intersection, and net CO2 reduction occurs at all potentials below it. The potentials of zero net catalytic current are the same in both scan directions, and they define the reduction potential for the interconversion of CO2 and formate in the solution. Importantly, the current varies continuously across the reduction potential, showing that catalysis is thermodynamically reversible (even the smallest displacement in potential drives turnover) and that the system interconverts electrical and chemical bond energy efficiently.

The pH-Dependent Reduction Potential of CO2.

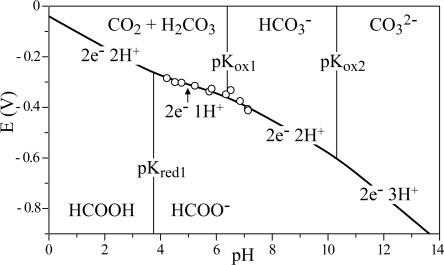

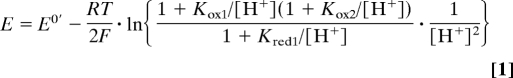

Fig. 3 shows how the reduction potential of CO2, measured as the potential of zero net catalytic current in 10 mM CO2 and 10 mM formate, varies between pH 4 and pH 8 (the region in which both oxidation and reduction are observed). The data have been fit by using the Nernst equation (Eq. 1). Because the total concentration of solution carbonate species (CO2(T) = CO2(aq) + H2CO3 + HCO3− + CO32−) present under 1 atm of CO2 increases dramatically at higher pH, Eq. 1 has been calculated by using a closed system containing 1 M CO2(T) instead. It includes the pK values for both the oxidized and reduced states, defined in Fig. 3.

|

The Pourbaix diagram (see Fig. 3) shows that at low pH the pH-dependence reflects the two-electron, one-proton interconversion of CO2 (or H2CO3) and formate and, at higher pH, the two-electron, two-proton interconversion of HCO3− and formate. Thus, the data define an effective pKox1 of 6.39 for the equilibrium between CO2 (or H2CO3) and HCO3−, matching the known value (21). The reduction potential at pH 7 is −0.389 V, a value that is consistent with that commonly adopted at neutral pH (−0.42 or −0.43 V, for example, refs. 6 and 25). By using the known value of pKred1 (3.75) and Eq. 1, the measured reduction potentials extrapolate to −0.042 V at pH 0. Previously, values for the standard reduction potential for CO2 to formic acid (pH 0, 1 atm CO2, 289 K) have been calculated from calorimetric data (because irreversible electrochemical responses preclude direct measurements). Perhaps surprisingly, given the current level of interest in CO2 reduction, no consensus has been reached, and two different values are quoted, −0.199 V (26) and −0.11 V (4). By using 34 mM atm−1 for Henry's constant (21), the two standard potentials are redefined as −0.157 V (26) and −0.067 V (4) for 1 M CO2(T) instead of 1 atm of CO2. By using the published pK values (21), they give −0.496 and −0.406 V at pH 7, respectively. The values reported here were recorded under nonstandard conditions, in 10 mM formate and 10 mM CO2(T), at 310 K. They are most consistent with the standard potential of −0.11 V under 1 atm of CO2 (equivalent to −0.067 V in 1 M CO2(T) or −0.406 V at pH 7). Note that experimental measurement of the standard reduction potential is complicated by the highly imperfect behavior of CO2 (particularly at high pH) and by the impracticality of measuring at pH 0 by using an enzyme-based system.

Fig. 3.

The pH-dependent reduction potential of CO2, measured by using the electrocatalytic voltammetry of FDH1. The reduction potentials (open circle, measured as illustrated in Fig. 2B), were recorded in 10 mM formate and 10 mM CO2 at 310 K. They have been fitted to the Nernst equation for the reduction potential of CO2 (Eq. 1) by using the parameters pKred1 = 3.75, pKox1 = 6.39, pKox2 = 10.32 (21) and E0′ = −0.042 V The pH-dependent reduction potential is superimposed on the Pourbaix diagram, showing which species are most stable thermodynamically at different pH values and potentials.

Rate of Catalysis by FDH1.

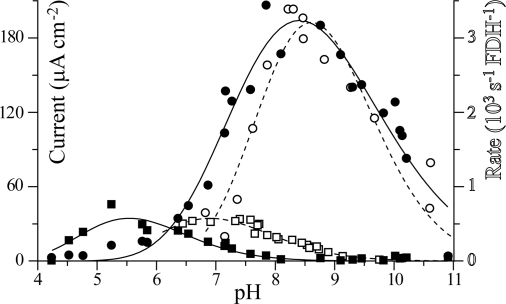

The rate of formate oxidation by FDH1 is greatest at pH 8.4, both in conventional solution assays and on the electrode surface (see Fig. 4). In conventional assays, the rate of CO2 reduction increases at lower pH but cannot be measured below pH 6.5 because the absorption coefficient of the MV radical decreases significantly. Electrocatalytic CO2 reduction is greatest at pH 5.5. These observations are consistent with CO2 being the species that is reduced (rather than HCO3− or CO32−) (27). Direct comparisons of the rates of catalysis in solution and on the electrode are difficult. They may be confounded by kinetic limitations from the artificial redox partner and from interfacial electron transfer, respectively. Furthermore, the amount of electrocatalytically active adsorbed enzyme is too low to be detected in the absence of substrate and may vary with pH. During a 1-hour incubation in a graphite electrocatalysis pot, the total amount of FDH1 that adsorbed to the electrode surface (whether in an electrocatalytically active conformation or not) was estimated from the FDH1 activity lost from solution, and it corresponded to a densely packed monolayer (3.7 ± 0.5 × 10−12 mol cm−2, calculated value 3.5 × 10−12 mol cm−2, assuming a protein density of 1.4 g cm−3). Using the turnover numbers from conventional assays suggests that a monolayer of electrocatalytically active FDH1 should produce limiting current densities of 0.2 mA for CO2 reduction at pH 7.5 and 2.4 mA for formate oxidation at pH 8 [comparable with the current density from H2 oxidation at either platinum or hydrogenase-modified electrodes (23)]. The maximum current densities observed so far in the voltammetric experiments (as shown in Fig. 2) are significantly lower (0.015 and 0.5 mA cm−2, respectively), showing that the number of electrocatalytically active molecules adsorbed on the surface is much lower than that required to constitute a complete monolayer. The low currents observed also reflect the need to optimize the interfacial electron transfer characteristics, to contract the potential-dependent domain and realize the true limiting current.

Fig. 4.

The kinetics of catalysis by FDH1 as a function of pH. Electrocatalytic current densities from the first voltammetric scan in 10 mM formate and 10 mM CO2 at 0.25 V overpotential (left-hand axis) are compared to data from conventional assays in solution in 10 mM formate or 10 mM CO2 (monitored by formation or consumption of the methyl viologen radical, right-hand axis). Lines are guidelines only (dashed lines and open symbols, and solid lines and filled symbols). Open circle, rate of formate oxidation in solution; filled circle, electrocatalytic formate oxidation; open square, rate of CO2 reduction in solution; filled square, electrocatalytic CO2 reduction.

Importantly, electrocatalytic CO2 reduction is observed to increase 6-fold from pH 7.5 to 5.5 (see Fig. 4). The highest current density attained so far in a single experiment (0.080 mA cm−2 at pH 5.9 at −0.8 V) corresponds to an average turnover number of 112 s−1 from a monolayer of FDH1. This value is a known underestimate for the true rate of electrocatalysis by FDH1 (much less than a monolayer of electrocatalytically active enzyme is actually present (see above), and the current at −0.8 V has not achieved its potential independent limit). Nevertheless, it is still more than two orders of magnitude faster than CO2 hydrogenation by ruthenium complexes in supercritical CO2 (5) and 10 times faster than photosynthetic CO2 activation during the carboxylation of d-ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate by rubisco (28).

Formate Is the Only Product of CO2 Reduction by FDH1.

To establish the products of electrochemical CO2 reduction by FDH1, a graphite “pot” working electrode was used for bulk electrocatalysis. FDH1 was adsorbed from the solution [containing 20 mM sodium carbonate (pH 6.5)] during electrocatalysis. This method sustained a small population of adsorbed electroactive molecules but provided a lower maximum current (typically 15 μA cm−2 after 15 min.) than direct application of a concentrated solution. The overpotential and time of electrocatalysis were varied; typically, in a 1-hour experiment the current at −0.8 V averaged 8.5 μA cm−2 (30.4 mC cm−2 h−1), and the FDH1 molecules present catalyzed, on average, 42,500 transformations. The total charge passed was defined by integrating the current–time curve, and the formate produced was quantified by ion-exclusion chromatography. The data (see Table 1) reveal that formate is the sole product of electrocatalytic CO2 reduction by FDH1, with a measured Faradaic efficiency of ≈100% at modest overpotentials. At higher overpotentials, the efficiency decreases slightly (to 97% at 0.45 V overpotential) because nonspecific electrode reactions begin to contribute.

Table 1.

Quantitative electrochemical reduction of CO2 to formate catalyzed by FDH1

| Applied potential, V | Faradaic efficiency, % | Thermodynamic efficiency, % |

|---|---|---|

| −0.41 | 102.1 ± 2.2 | 96.6 |

| −0.51 | 98.6 ± 3.6 | 89.5 |

| −0.61 | 98.0 ± 1.7 | 83.4 |

| −0.81 | 97.3 ± 1.1 | 73.3 |

The Faradaic efficiency is the ratio of the formate detected to the charge consumed (accounting for two electrons per formate). The thermodynamic efficiency is the ratio of the chemical bond energy formed (EH2O–ECO2) to the potential difference applied (EH2O–Eapp), assuming that the oxidation of H2O to O2 is 100% efficient [EH2O = 0.844 V, ECO2 = −0.368 V (pH 6.5)]. Experimental conditions: 20 mM sodium carbonate (pH 6.5).

Discussion

There have been many attempts to drive the electrochemical reduction of CO2 to formate (4, 6, 7). However, excessive overpotentials were required so that a significant proportion of the potential applied was dissipated as heat. Furthermore, mixtures of products were formed, resulting from the formation of the CO2− radical and from competing reactions such as hydrogen formation. Notably, the direct reduction of aqueous CO2 at lead, mercury, indium, and thallium electrodes produces formate with >90% Faradaic efficiency but only at potentials below −1.5 V. Table 1 reports the “thermodynamic efficiency” of CO2 reduction (coupled to H2O oxidation) at the overpotentials used here. For comparison, at −1.5 V, ≈50% of the potential is dissipated as heat. Preliminary attempts to use a ruthenium catalyst to reduce CO2 to formate electrochemically required similarly high overpotentials and also led to a mixture of products (29). Formate dehydrogenase from Pseudomonas oxalaticus was applied also to the electrochemical reduction of CO2 (25). However, it was present in solution at high concentration, and electron transfer between the enzyme and the electrode was mediated by millimolar concentrations of methyl viologen (comparable with the concentrations of formate generated), with variable Faradaic efficiency. The only previous demonstration of efficient electrocatalytic CO2 reduction is from another adsorbed enzyme, CO dehydrogenase I from Carboxydothermus hydrogenoformans, which catalyzes the rapid and reversible interconversion of CO2 and CO (not CO2 and formate) (30).

Virtually nothing is known about the mechanism of CO2 activation and reduction in enzymes such as FDH1. A number of rudimentary bis(dithiolene)tungstenIV,VI thiolate and selenolate compounds have been synthesized to mimic the active sites of formate dehydrogenases (31), but, perhaps unsurprisingly, they exhibit no catalytic activity. However, although molybdenum and tungsten are not generally associated with biological hydride transfer reactions (14, 32), CO2 is known to insert into the W–H bond in [HW(CO)5]− to form a stable formate adduct (33), and considerable progress has been made in developing homogeneous organometallic catalysts based on M–H insertion reactions (3, 4). For example, CO2 insertion into Ru(terpy)(bpy)H+ proceeds at 8.5 s−1 in 10 mM CO2 (although displacement of the formate by H2O to complete a catalytic cycle is significantly slower) (34).

FDH1 is the first example of a molecular structure that can activate an electrode to reduce CO2 (and form a C–H bond) specifically, rapidly, reversibly, and under thoroughly mild conditions. Although, as a large and oxygen-sensitive protein complex it is not itself a realistic target for technical exploitation, FDH1 establishes an important paradigm. It is accessible to electrochemical, spectroscopic and structural studies, to provide detailed mechanistic information and elucidate structure-function relationships. It is hoped that these will aid in the rational evaluation and development of robust synthetic compounds that host similar chemical and electrochemical capabilities to FDH1 and that would be suitable for future applications in carbon capture, energy storage, and fuel cell devices.

Materials and Methods

All procedures were carried out under strictly anaerobic conditions. FDH1 was isolated from S. fumaroxidans cells grown on 20 mM propionate and 60 mM fumarate by using the protocol described (15) with minor modifications, except that FDH1 eluted from the hydroxyapatite column (40 μm type II CHT ceramic; Bio-Rad) in a linear gradient of sodium phosphate (pH 7). In conventional activity assays at 37°C, oxidation was initiated by 10 mM sodium formate, after a 2-min incubation of FDH1 in 1 mM MV, 10 μM dithionite, 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8), and reduction was initiated by adding 10 mM sodium carbonate to FDH1 in 100 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.5), 0.1 mM MV, 0.045 mM dithionite. The reactions were followed spectrometrically by the reduction of MV or by the oxidation of the MV radical, respectively (ε578 = 9.7 mM−1 cm−1). pH values were checked after experimentation.

Cyclic voltammetry was performed at 37°C as described (24), by using a rotating disk pyrolytic graphite edge (PGE) electrode. pH was controlled by using a mixed-buffer system [10 mM potassium acetate, 2-morpholinoethane sulfonic acid (Mes), N-cyclohexyl-2-aminoethane sulfonic acid (Hepes), and N-tris(hydroxymethyl)methyl-3-aminopropanesulfonic acid (TAPS)] and checked following experimentation. All potentials are reported relative to the standard hydrogen electrode. Electrocatalysis was carried out at 25°C in 100 mM Mes (final pH 6.5), 1 M NaCl, 20 mM sodium carbonate, and ≈5 μg FDH1, in a PGE pot working electrode (0.75 ml, surface area 3.94 cm2) and monitored amperometrically. The Ag/AgCl reference electrode and platinum mesh counter electrode were behind a Vycor glass frit. Formate concentrations were determined by ion-exclusion chromatography (using a Dionex AS15 column (2 × 250 mm), IonPac AG15 guard column (2 × 50 mm), and suppressed-conductivity ICS-2000 detector). Formate was eluted isocratically in 20 mM KOH, and concentrations >0.25 ppm (5.4 μM) were determined with a standard deviation of 0.5%.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Michael Harbor (Dunn Proteomics Group) for tandem mass spectrometry, Susan Foord (British Antarctic Survey) and Paul Dewsbury (Dionex) for assistance with formate analyses, and Frank de Bok for advice on preparing FDH1. This work was supported by The Medical Research Council.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0801290105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.United Nations Development Programme, United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, and World Energy Council. World Energy Assessment: Energy and the Challenge of Sustainability. New York: United Nations Development Programme; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Fourth Assessment Report: Climate Change 2007. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keene FR, Sullivan BP. Mechanisms of the electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide catalyzed by transition metal complexes. In: Sullivan BP, Krist K, Guard HE, editors. Electrochemical and Electrocatalytic Reactions of Carbon Dioxide. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1993. pp. 118–144. [Google Scholar]

- 4.DuBois DL. Electrochemical reactions of carbon dioxide. In: Bard AJ, Stratmann M, editors. Encyclopaedia of Electrochemistry. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley–VCH; 2006. pp. 202–225. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jessop PG, Ikariya T, Noyori R. Homogeneous catalytic hydrogenation of supercritical carbon dioxide. Nature. 1994;368:231–233. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hori Y. CO2-reduction catalyzed by metal electrodes. In: Vielstich W, Gasteiger HA, Lamm A, editors. Handbook of Fuel Cells. Vol 2. Chichester, UK: Wiley; 2003. pp. 720–733. Fundamentals, Technology and Applications. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frese KW. Electrochemical reduction of CO2 at solid electrodes. In: Sullivan BP, Krist K, Guard HE, editors. Electrochemical and Electrocatalytic Reactions of Carbon Dioxide. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1993. pp. 145–216. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ha S, Dunbar Z, Masel RI. Characterization of a high performing passive direct formic acid fuel cell. J Power Sources. 2006;158:129–136. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thauer RK. CO2-reduction to formate by NADPH. The initial step in the total synthesis of acetate from CO2 in Clostridium thermoaceticum. FEBS Lett. 1972;27:111–115. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(72)80421-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyington JC, Gladyshev VN, Khangulov SV, Stadtman TC, Sun PD. Crystal structure of formate dehydrogenase H: Catalysis involving Mo, molybdopterin, selenocysteine, and an Fe4S4 cluster. Science. 1997;275:1305–1308. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5304.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jormakka M, Törnroth S, Byrne B, Iwata S. Molecular basis of proton motive force generation: structure of formate dehydrogenase-N. Science. 2002;295:1863–1868. doi: 10.1126/science.1068186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raaijmakers H, et al. Gene sequence and the 1.8 Å crystal structure of the tungsten-containing formate dehydrogenase from Desulfovibrio gigas. Structure (London) 2002;10:1261–1272. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00826-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vorholt JA, Thauer RK. Molybdenum and tungsten enzymes in C1 metabolism. In: Siegel A, Siegel H, editors. Metal Ions in Biological Systems. Vol 39. New York: Dekker; 2002. pp. 571–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kletzin A, Adams MWW. Tungsten in biological systems. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1996;18:5–63. doi: 10.1016/0168-6445(95)00025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Bok FAM, et al. Two W-containing formate dehydrogenases (CO2-reductases) involved in syntrophic propionate oxidation by Syntrophobacter fumaroxidans. Eur J Biochem. 2003;270:2476–2485. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Bok FAM, Luijten MLGC, Stams AJM. Biochemical evidence for formate transfer in syntrophic propionate-oxidizing cocultures of Syntrophobacter fumaroxidans and Methanospirillum hungatei. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:4247–4252. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.9.4247-4252.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zinoni F, Birkmann A, Stadtman TC, Böck A. Nucleotide sequence and expression of the selenocysteine-containing polypeptide of formate dehydrogenase (formate-hydrogen-lyase-linked) from Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:4650–4654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.13.4650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bertero MG, et al. Insights into the respiratory electron transfer pathway from the structure of nitrate reductase A. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:681–687. doi: 10.1038/nsb969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schindelin H, Kisker C, Hilton J, Rajagopalan KV, Rees DC. Crystal structure of DMSO reductase: Redox-linked changes in molybdopterin coordination. Science. 1996;272:1615–1621. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5268.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sazanov LA, Hinchliffe P. Structure of the hydrophilic domain of respiratory complex I from Thermus thermophilus. Science. 2006;311:1430–1436. doi: 10.1126/science.1123809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palmer DA, van Eldik R. The chemistry of metal carbonato and carbon dioxide complexes. Chem Rev. 1983;83:651–731. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Léger C, et al. Enzyme electrokinetics: Using protein film voltammetry to investigate redox enzymes and their mechanisms. Biochemistry. 2003;42:8653–8662. doi: 10.1021/bi034789c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vincent KA, Parkin A, Armstrong FA. Investigating and exploiting the electrocatalytic properties of hydrogenases. Chem Rev. 2007;107:4366–4413. doi: 10.1021/cr050191u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reda T, Hirst J. Interpreting the catalytic voltammetry of an adsorbed enzyme by considering substrate mass transfer, enzyme turnover, and interfacial electron transport. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:1394–1404. doi: 10.1021/jp054783s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parkinson BA, Weaver PF. Photoelectrochemical pumping of enzymatic CO2 reduction. Nature. 1984;309:148–149. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Inzelt G. Standard, formal, and other characteristic potentials of selected electrode reactions. In: Bard AJ, Stratmann M, editors. Encyclopaedia of Electrochemistry. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley–VCH; 2006. pp. 17–76. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thauer RK, Käufer B, Fuchs G. The active species of ‘CO2’ utilized by reduced ferredoxin:CO2 oxidoreductase from Clostridium pasteurianum. Eur J Biochem. 1975;55:111–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1975.tb02143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tcherkez GGB, Farquhar GD, Andrews TJ. Despite slow catalysis and confused substrate specificity, all ribulose bisphosphate carboxylases may be nearly perfectly optimized. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:7246–7251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600605103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pugh JR, Bruce MRM, Sullivan BP, Meyer TJ. Formation of a metal-hydride bond and the insertion of CO2. Key steps in the electrocatalytic reduction of carbon dioxide to formate anion. Inorg Chem. 1991;30:86–91. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parkin A, Seravalli J, Vincent KA, Ragsdale SW, Armstrong FA. Rapid and efficient electrocatalytic CO2/CO interconversions by Carboxydothermus hydrogenoformans CO dehydrogenase I on an electrode. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:10328–10329. doi: 10.1021/ja073643o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Groysman S, Holm RH. Synthesis and structures of bis(dithiolene)-tungsten(IV,VI) thiolate and selenolate compounds: approaches to the active sites of molybdenum and tungsten formate dehydrogenases. Inorg Chem. 2007;46:4090–4102. doi: 10.1021/ic062441a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kisker C, Schindelin H, Rees DC. Molybdenum-cofactor-containing enzymes: Structure and mechanism. Annu Rev Biochem. 1997;66:233–267. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Darensbourg DJ, Rokicki A, Darensbourg MY. Facile reduction of carbon dioxide by anionic group 6B metal hydrides. Chemistry relevant to catalysis of the water–gas shift reaction. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:3223–3224. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Creutz C, Chou MH. Rapid transfer of hydride ion from a ruthenium complex to C1 species in water. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:10108–10109. doi: 10.1021/ja074158w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.