Abstract

Asthma exacerbations can be triggered by viral infections or allergens. The Th2 cytokines IL-13 and IL-4 are produced during allergic responses and cause increases in airway epithelial cell mucus, electrolyte and water secretion into the airway surface liquid (ASL). Since ASL dehydration can cause airway inflammation and obstruction, ion transporters could play a role in pathogenesis of asthma exacerbations. We previously reported that expression of the epithelial cell anion transporter pendrin is markedly increased in response to IL-13. Here we show that pendrin plays a role in allergic airway disease and in regulation of ASL thickness. Pendrin-deficient mice had less allergen-induced airway hyperreactivity and inflammation than control mice although other aspects of the Th2 response were preserved. In cultures of IL-13-stimulated mouse tracheal epithelial cells, pendrin deficiency caused an increase in ASL thickness, suggesting that reductions in allergen-induced hyperreactivity and inflammation in pendrin-deficient mice result from improved ASL hydration. To determine whether pendrin might also play a role in virus-induced exacerbations of asthma, we measured pendrin mRNA expression in human subjects with naturally occurring common colds caused by rhinovirus and found a 4.9-fold-increase in mean expression during colds. Studies of cultured human bronchial epithelial cells indicated that this increase could be explained by the combined effects of rhinovirus and IFN-γ, a Th1 cytokine induced during virus infection. We conclude that pendrin regulates ASL thickness and may be an important contributor to asthma exacerbations induced by viral infections or allergens.

Keywords: Allergy, Inflammation, Infections-Viral, Transgenic/Knockout Mice, Lung

Introduction

Asthma is a common chronic disease of children and adults which is characterized by airway inflammation, hyperreactivity, mucus overproduction and airway obstruction (1). Asthma exacerbations are commonly triggered by infections with respiratory viruses, especially rhinovirus, and can also be triggered by other environmental factors, including allergens (2-4). The airway epithelial cell is a prominent participant in asthma exacerbations. Epithelial cell mucus production is increased in asthma (5) and plugging of the airways with mucus is a prominent and sometimes fatal feature of severe asthma exacerbations (6). Rhinovirus infects airway epithelial cells directly, inducing changes in gene expression (7), and also induces leukocyte production of IFN-γ (8), which has effects on epithelial and other cells in the airway (9). Airway epithelial cells also play central roles in the response to allergens. In this setting, Th2 cells and other cells produce IL-13 and IL-4, cytokines that act directly on airway epithelial cells to induce mucus production and airway hyperreactivity (10, 11). A recent clinical trial found that inhalation of an inhibitor of IL-13 and IL-4 reduced the late asthmatic response to allergen challenge (12), suggesting that these mechanisms discovered in mouse models are relevant to humans with asthma.

Changes in the airway surface liquid (ASL) which covers the epithelium can cause airway disease. ASL is comprised of a mucus layer and a periciliary layer (13). Ciliary beating and coughing propel ASL toward the upper airways thereby removing mucus and inhaled pathogens and particles (14). ASL thickness is regulated by active ion transport across epithelial cells (15). In cystic fibrosis, mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene (CFTR) result in decreased chloride secretion, ASL dehydration, impaired mucus clearance, and airway inflammation and obstruction (16). Similar pathology was seen in mice with ASL dehydration resulting from transgenic overexpression of the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) (17). Changes in ion transport have also been implicated in asthma pathogenesis. IL-13 or IL-4 stimulation alters chloride conductance and converts human bronchial epithelial cells from an absorptive to a secretory phenotype, which may help to “flush” particulates and mucus from the airway lumen (18). In a recent genome-wide analysis, CLCA1 (calcium-activated chloride channel 1) was the most highly upregulated gene in bronchial epithelial cells of asthmatics compared with healthy controls (19). Despite its name, CLCA1 is not a channel but CLCA1 does affect chloride conductance by an unknown mechanism (20). Increased expression of CLCA1 may be important in asthma pathogenesis since overexpression of its mouse ortholog (known as Gob-5 or Clca3) was reported to cause airway inflammation and airway hyperreactivity (21), although the precise contributions of CLCA1 and other CLCA family members are still controversial (22-24). Other molecules involved in the transport of ions, including the Na+-K+-Cl- cotransporter NKCC1 (25), may also play a role but the contributions of these molecules to asthma pathogenesis is unknown.

We previously reported that mRNA encoding the anion transporter pendrin (solute carrier family 26 member 4, Slc26a4) is increased in acute allergic airway disease (26), suggesting that pendrin could contribute to allergic airway disease and might play a role in asthma. Pendrin is a 780-amino acid anion transporter that is expressed in the inner ear, the kidney and the thyroid (27). Pendrin can exchange chloride for other anions, including bicarbonate, oxalate, and hydroxyl ions (28). In Pendred syndrome, a common form of hereditary hearing loss caused by mutations in SLC26A4 (29), impaired anion and water uptake in the inner ear results in endolymphatic swelling and structural aberrations (30). Relatively little is known about the role of pendrin in the lung. We found 10-40-fold increases in mouse pendrin (Slc26a4) mRNA in the lung after allergen challenge or transgenic overexpression of IL-13 (26) and a >200-fold increase in SLC26A4 mRNA following IL-13 stimulation of cultured normal human bronchial epithelial (NHBE) cells (31). It has recently been shown that IL-4 increases expression of both SLC26A4 mRNA and pendrin protein in NHBE cells resulting in increased secretion of thiocyanate, an anion with antimicrobial properties (32). A very recent report found that overexpression of pendrin in the airway resulted in mucus overproduction, airway hyperreactivity and inflammation (33). However, the contributions of pendrin to allergic airway disease have not yet been directly addressed.

We hypothesized that allergen-induced increases in pendrin contribute to altered airway function by affecting ASL hydration. To address this issue, we took advantage of the availability of pendrin-deficient (Slc26a4-/-) mice (30). Although these mice are deaf, thyroid function is unimpaired and kidney function is normal except during sodium restriction (30, 34). We used Slc26a4-/- mice to study the role of pendrin in the in vivo response to allergen and Slc26a4-/- mouse tracheal epithelial cells (MTEC) to investigate how pendrin affects ASL thickness. To determine whether pendrin is also induced by viral infection, the most common precipitant of asthma exacerbations, we also analyzed the expression of SLC26A4 in nasal epithelium from human subjects with naturally occurring rhinovirus infections and in cultured NHBE cells infected with rhinovirus. The results of these studies indicate that pendrin is induced by stimuli that provoke asthma exacerbations and contributes to airway inflammation and hyperreactivity.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Pendrin-deficient (Slc26a4-/-) mice on a 129Sv/Ev genetic background were generously provided by E. Green (30). Mice were bred and maintained under pathogen-free conditions. Slc26a4+/+ and Slc26a4+/- littermates were used as controls for the in vivo allergen challenge model. All experiments were performed according to the guidelines of the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Committee on Animal Research.

Sensitization and challenge with OVA

Age- and sex-matched 6-8-week-old mice were sensitized by i.p. injection of OVA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) on days 0, 7 and 14 as reported previously (26). The sensitizing emulsion consisted of 50 μg OVA and 10 mg of aluminum potassium sulfate in 200 μl of saline. On days 21, 22, and 23, the sensitized mice were lightly anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation and challenged with 100 μg OVA in 30 μl of saline administered intranasally. Control mice were treated in the same way, except that OVA was omitted during both the sensitization and challenge phases.

Assessment of airway reactivity, inflammation, OVA-specific IgE, and mucus

Airway reactivity was measured as previously reported (35). Briefly, on day 24, mice were anesthetized, intratracheally intubated, mechanically ventilated and paralyzed and airway resistance was measured at baseline and following intravenous administration of increasing doses of acetylcholine (0.03, 0.1, 0.3, 1 and 3 μg/g body weight). Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid leukocytes and serum OVA-specific IgE levels were measured as previously described (26). Paraffin-embedded 5 μm lung sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and with periodic acid-Schiff for evaluation of mucus production. The severity of peribronchial inflammation was scored by a blinded observer using the following features: 0, normal; 1, few cells; 2, a ring of inflammatory cells 1 cell layer deep; 3, a ring of inflammatory cells 2-4 cells deep; 4, a ring of inflammatory cells of > 4 cells deep (36). Epithelial cell mucus content was determined using stereology as previously reported (11).

Analysis of mouse gene expression by quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA from mouse lungs was isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA) and purified using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA). First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using the SuperScript First-Strand cDNA Synthesis System (Invitrogen). Total RNA from MTEC cells was isolated using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen) and first-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen). Mouse Slc26a4 primers were 5′-CATCTGCAGAACCAGGTCAA-3′ and 5′-GCATTCATCTCTGCCTCCAT-3′. Mouse sodium channel, nonvoltage-gated, type I, α (Scnn1a) primers were 5′-CGGAGTTGCTAAACTCAACATC-3′ and 5′-TGGAGACCAGTACCGGCT-3′. Mouse Scnn1b primers were 5′-CTGCAGTCATCGGAACTTCA-3′ and 5′-CCGATGTCCAGGATCAACTT-3′. Mouse Scnn1g primers were 5′-CTTCTTCACTGGTCGGAAGC-3′ and 5′-CTGAAGGTGTAGGTGGCACA-3′. Mouse cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (Cftr) primers were 5′-AAGGCGGCCTATATGAGGTT-3′ and 5′-GGACGATTCCGTTGATGACT-3′. Mouse Clca3 primers were 5′-GCCCTCTAGGCAATGATGAG-3′ and 5′-CCTGTCTTGTGGCCCATACT-3′. Mouse β-actin (Actb) primers were 5′-TGTTACCAACTGGGACGACA-3′ and 5′-GGGGTGTTGAAGGTCTCAAA-3′. Mouse Gapd primers were 5′-GCCTTCCGTGTTCCTACCC-3′ and 5′-TGCCTGCTTCACCACCTTC-3′. Sequences of other primers and probes used here have been previously reported (31). SYBR Green real-time PCR was performed using the 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The threshold cycle (Ct) of each transcript was normalized to the average Ct for Actb and Gapd. Fold differences were determined by the 2-ΔΔCt method (37).

Culture of MTEC

MTEC were isolated from age-matched 6-14-week-old pendrin-deficient mice and wild type littermate controls and cultured as previously described (38). Cells were considered to be confluent when transepithelial resistance was >1000 Ω·cm2. After reaching confluence, MTEC were cultured at air-liquid interface for 14-17 days in the absence or presence of 20 ng/ml murine IL-13 (PeproTech Inc., Rocky Hill, NJ) as indicated in the text.

Measurement of ASL thickness

ASL thickness was measured using previously reported methods (39). Briefly, dextran-conjugated BCECF (Invitrogen) was suspended in FC-72 (3M, St. Paul, MN) at a concentration of 10 mg/ml and 20-50 μl of the suspension was deposited onto the ASL 3 min before measurement. ASL thickness was measured with a Nikon EZ-C1 laser scanning confocal system and a Nikon ECLIPSE FN1 upright microscope. Fluorescent images were obtained using a 10× objective (Plan Fluor, numerical aperture 0.30, working distance 15.8 mm). ASL thickness was determined from the fluorescence peak width (width at half-maximal fluorescence) along the z-axis. Standards made using known volumes of BCECF-containing solution sandwiched between coverglasses were used for calibration. ASL was exposed to a fully humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere, and air and a stage were maintained at 37°C using a Tempcontrol heating system (PeCon GmbH, Germany).

Collection of human nasal samples during common colds

The clinical study was approved by the UCSF Committee of Human Research and all subjects signed a written informed consent. Asthmatic and non-asthmatic control subjects were recruited within 3 days of onset of common colds through advertisements on the internet and campus flyers and by contacting subjects from previous studies. Subjects were characterized by spirometry, allergy skin testing and methacholine bronchial reactivity as we previously described (40). Subjects had 3 visits at 1-3 d (visit 1), 5-7 d (visit 2) and ∼ 42 d (visit 3, baseline) after cold symptom onset. In visit 1, nasal lavage was used to identify rhinovirus and other viruses as previously described (41). Subjects recorded nasal and chest symptoms during the week after visit 1 and the week before visit 3. Nasal cold symptoms were scored by adding together daily scores for each of 8 symptoms (nasal discharge, nasal congestion, sneezing, throat discomfort, tiredness, cough, fever/chills and headache; each scored from 0-3) over one week (yielding a possible weekly range of 0-168). The final nasal cold symptom score was calculated as the difference between score for the week after visit 1 (cold) and the score for the week before visit 3 (baseline). Chest symptoms were the change of scores for 5 symptoms (shortness of breath, chest tightness, wheezing, cough and sputum production; each scored 0-10; possible weekly range, 0-350). At each visit, 3 nasal lavages with 10 ml of normal saline solution each were performed before collecting nasal mucosal samples using Rhino-Probe curettes (Arlington Scientific Inc., Springville, UT). Mucosal samples were collected from the infero-medial aspect of the inferior turbinate on one side at visit 1, from the other side at visit 2, and from either side at visit 3. Nasal mucosal samples were immediately placed in RNeasy kit solution with β-mercaptoethanol, frozen at bedside in dry ice and stored at -80°C. Nasal mucosal samples had >95% epithelial cells.

Evaluation of SLC26A4 mRNA in human nasal mucosal samples

After RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis, SLC26A4 mRNA was quantified using a validated two-step real-time PCR method (25). Primer and probe sequences have been previously reported (26).

In vitro infection of NHBE cells with rhinovirus

NHBE cells from normal individuals (Lonza Inc., Allendale, NJ, passage 1-4) were seeded onto 6.5 mm Transwell inserts (BD Biosciences) at 5 × 104 cells/insert and grown to 100% confluence and then cultured at air-liquid interface for 2 weeks to promote epithelial differentiation. Rhinovirus serotype 16 (RV16) was grown in HeLa cells, purified by sucrose gradient and quantified by a plaque forming unit assay using standard virological methods. NHBE cells were infected on the apical side with RV16 (multiplicity of infection: 5) for 6 h at 35°C with mild agitation at 2 rpm, after which virus was washed off with PBS and the cells were cultured for 24 h. Some cells were pre-stimulated with 10 ng/ml human IFN-γ (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) for 24 h before RV16 infection. Control cells received a sham inoculum. SLC26A4 mRNA expression was measured using the same primer and probe sequences used for analysis of the nasal mucosal samples and changes in gene expression were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method.

Statistical analyses

With the exception of the pendrin measurements from nasal epithelial cells from human subjects, data are presented as means ± SEM and significance testing was done using Student’s t-test, Tukey’s test or Tukey-Kramer’s test after ANOVA, or Kruskal-Wallis’s test. P values below 0.05 were considered significant. For comparing characteristics of asthmatic and non-asthmatic subjects, we used the Mann-Whitney’s rank test for continuous variables or Fisher Exact test for categorical variables. Levels of SLC26A4 mRNA among the three visits were analyzed using generalized estimating equations (xtgee command of Stata). Pairwise comparisons between two visits were then analyzed using Wilcoxon’s signed-rank test. KaleidaGraph (Ver. 3.6, Synergy Software, Reading, PA) and Stata (Ver. 8, StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) software packages were used for statistical analyses.

Results

Allergen-induced airway hyperreactivity and inflammation are attenuated in pendrin-deficient mice

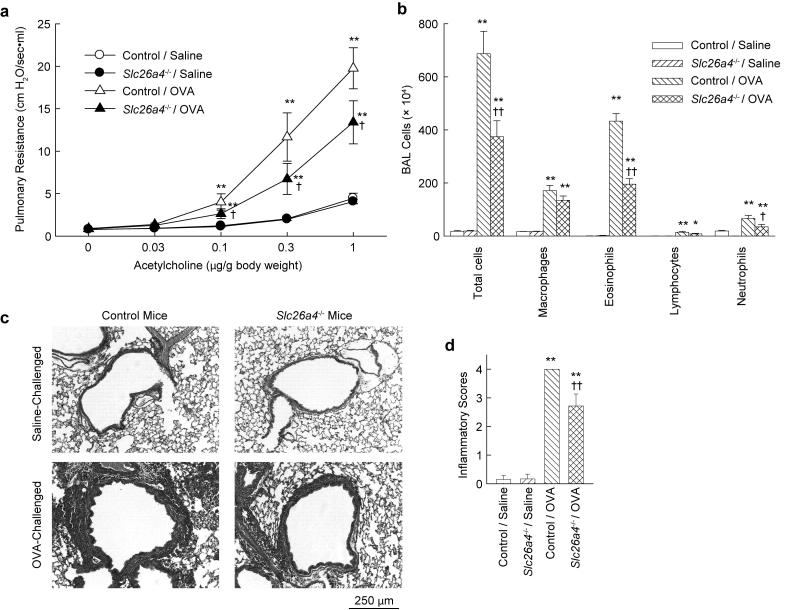

Pendrin-deficient mice and control mice were sensitized and then challenged by intranasal administration of OVA to produce an allergic response in the lung and airway. Respiratory system resistance was measured in sedated and mechanically ventilated mice after intravenous administration of acetylcholine (Fig. 1a). OVA challenge increased airway reactivity in control mice, as expected. Airway hyperreactivity was also observed in OVA-challenged pendrin-deficient mice, but the degree of hyperreactivity was significantly less than in OVA-challenged control mice. There were no differences in airway reactivity to acetylcholine between saline-challenged control and saline-challenged pendrin-deficient mice. BAL fluid was collected to assess the effects of OVA sensitization and challenge on inflammatory cell recruitment (Fig. 1b). Cells retrieved from saline-challenged mice were mostly macrophages. There were large increases in macrophages, eosinophils, lymphocytes and neutrophils in OVA-challenged control mice. Increases were also observed in OVA-challenged pendrin-deficient mice but the numbers of total cells, eosinophils and neutrophils were significantly less than in OVA-challenged control mice. Histological analysis revealed large numbers of inflammatory cells around the conducting airways in OVA-challenged control mice, but inflammation was significantly reduced in OVA-challenged pendrin-deficient mice (Fig. 1c,d).

FIGURE 1.

Allergen-induced airway hyperreactivity and inflammation are attenuated in pendrin-deficient (Slc26a4-/-) mice. a, Airway hyperreactivity to acetylcholine. b, BAL fluid cell counts. Results are means ± s.e.m., n = 12-14 mice per group. c, Representative hematoxylin and eosin stained lung sections. d, Inflammatory scores of lung sections, n = 6-8 mice per group. *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 vs. saline-challenged control mice (“Control / Saline”); † p < 0.05, †† p < 0.01 vs. OVA-challenged control mice (“Control / OVA”).

Allergen-induced IgE production, mucus metaplasia, and Th2 cytokine mRNA production are unaffected by pendrin deficiency

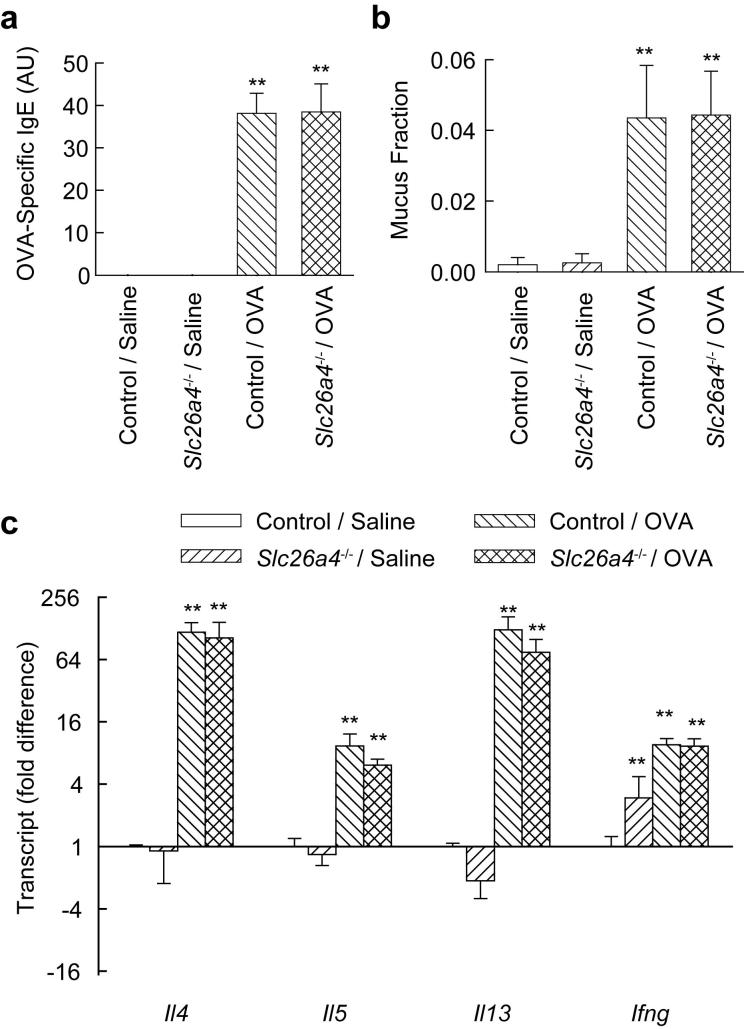

We measured OVA-specific IgE in serum to determine whether reduced airway hyperreactivity in pendrin-deficient mice might be explained by a generalized impairment in the allergic response. OVA challenge led to production of similar amounts of OVA-specific IgE in control and pendrin-deficient mice (Fig. 2a), indicating that this aspect of the allergic response was preserved. We also found that there was no difference in allergen-induced mucus metaplasia between control and pendrin-deficient mice (Fig. 2b). Since mucus metaplasia depends upon Th2 cytokines, especially IL-13, this result indicates that Th2 responses were intact in pendrin-deficient mice. Analysis of expression of mRNAs encoding the Th2 cytokines IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 and the Th1 cytokine IFN-γ in lungs from OVA-challenged mice revealed no significant differences between control and pendrin-deficient mice (Fig. 2c).

FIGURE 2.

Pendrin-deficiency does not affect allergen-induced OVA-specific IgE, epithelial mucus content or lung expression of Th2 cytokine mRNAs. a, Serum OVA-specific IgE in saline- and OVA-challenged control and pendrin-deficient (Slc26a4-/-) mice. OVA-specific IgE was not detectable in the saline challenged groups. b, Mucus content, represented as the volume of mucus divided by the total volume of airway epithelial cells. Results are means and error bars represent s.e.m., n = 6-8 mice per group. c, Gene transcript expression, measured by quantitative RT-PCR with fold differences normalized to saline-challenged control mice (“Control / Saline”), n = 4 mice per group. ** p < 0.01 vs. Control / Saline.

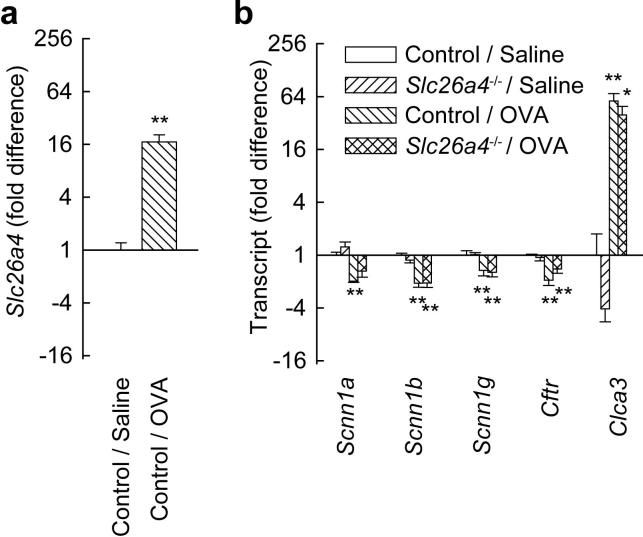

Allergen challenge induces changes in pendrin and ion channel mRNA expression in vivo

Allergen challenge increased the pendrin transcript Slc26a4 (Fig. 3a), as we reported previously (26). We also investigated the expression of five other mRNAs encoding proteins involved in epithelial cell ion transport. Allergen challenge significantly reduced transcripts encoding all three epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) subunits (Scnn1a, Scnn1b, and Scnn1g) and CFTR (Fig. 3b). Allergen challenge also led to a large increase in expression of Clca3 mRNA, as previously reported (21). There were no significant differences in expression of the three ENaC transcripts, Cftr, or Clca3 between OVA-challenged control and OVA-challenged pendrin-deficient mice.

FIGURE 3.

Allergen challenge affects lung expression of Slc26a4 and mRNAs encoding other proteins involved in ion transport. a, Effects of allergen on Slc26a4 expression in control mice. b, Effects of allergen on expression of ENaC mRNAs (Scnn1a, b, and g), Cftr and Clca3 in control and pendrin-deficient (Slc26a4-/-) mice. Results are means and error bars represent s.e.m., n = 4 mice per group. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 vs. saline-challenged control mice (“Control / Saline”).

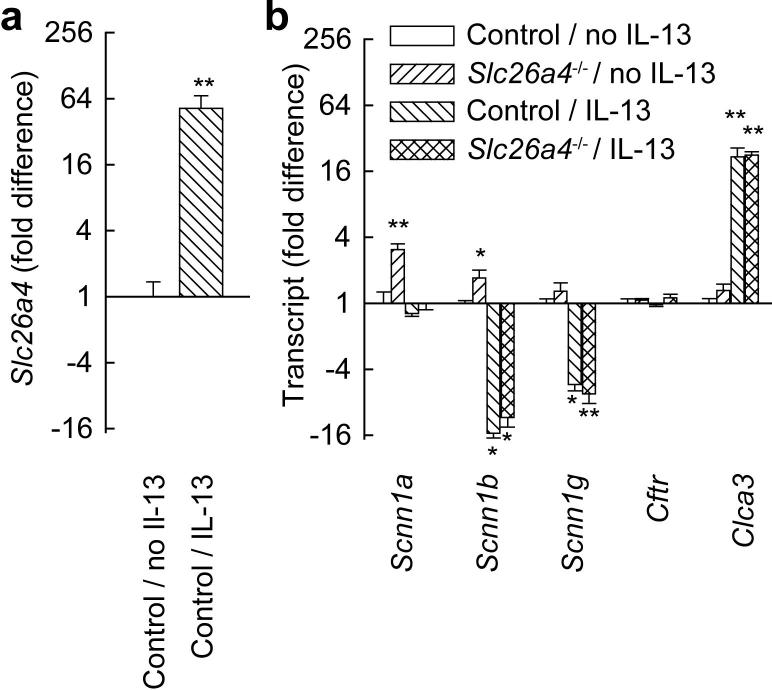

IL-13 stimulation of MTEC induces changes in pendrin and ion channel mRNA expression in vitro

To identify effects of pendrin on ASL, we studied MTEC cultures from control and pendrin-deficient mice. Cells were cultured at air-liquid interface, a method that allows cells to differentiate, polarize, and form an ASL layer. We first investigated how IL-13 stimulation of MTEC affected expression of transcripts encoding proteins involved in ion transport. IL-13 markedly upregulated Slc26a4 and Clca3 mRNAs in MTEC (Fig. 4a). We previously reported similar effects of IL-13 on the human orthologs of these mRNAs (SLC26A4 and CLCA1) in NHBE cells (31). Although Scnn1a expression was not affected by IL-13, Scnn1b and Scnn1g were both substantially decreased. Decreases in these 2 ENaC subunit mRNAs were substantially more marked than the decreases measured after in vivo allergen challenge (Fig. 4b). It is possible that the dose or duration of IL-13 stimulation used in the MTEC experiments accounts for this difference. Alternatively, since the whole lung samples analyzed in the allergen challenge model contain large numbers of ENaC-expressing alveolar epithelial cells (42), it seems likely the effects of IL-13 on Scnn1b and Scnn1g expression in airway epithelial cells were underestimated by the analysis of whole lung RNA. We did not identify any significant differences in expression of ENaC mRNAs, Cftr or Clca3 between IL-13-stimulated control MTEC and IL-13-stimulated pendrin-deficient MTEC (Fig. 4b). Muc5ac expression was similar in control and pendrin-deficient MTECs (not shown).

FIGURE 4.

IL-13 stimulation affects expression of Slc26a4 and mRNAs encoding other proteins involved in ion transport in MTEC cultures. a, Effects of 20 ng/ml IL-13 on Slc26a4 expression in MTEC cultures. b, Effects of IL-13 on expression of ENaC mRNAs (Scnn1a, b, and g), Cftr and Clca3 in MTEC cultures from control and pendrin-deficient (Slc26a4-/-) mice. Results are means and error bars represent s.e.m., n = 4 wells/group. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 vs. MTEC cultures from control mice that were not stimulated with IL-13 (“Control / No IL-13”).

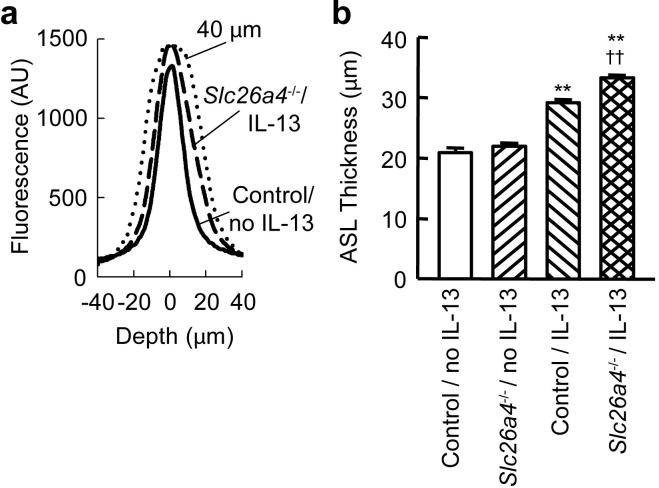

Pendrin deficiency results in increased ASL thickness

We measured ASL thickness of control and pendrin-deficient MTEC cultures stimulated with or without IL-13 using a confocal microscope. Typical z-axis fluorescence traces obtained from cultures of unstimulated and IL-13-stimulated control MTEC cells are shown in Fig. 5a. In the absence of IL-13, there was no significant difference in ASL thickness between control and pendrin-deficient MTEC cultures (Fig. 5b). IL-13 stimulation increased ASL thickness in both control and pendrin-deficient MTEC cultures. ASL in IL-13-stimulated pendrin-deficient MTEC cultures was significantly thicker than that in IL-13-stimulated control MTEC cultures, indicating that the effect of IL-13 on ASL was exaggerated in pendrin-deficient MTEC cultures.

FIGURE 5.

ASL thickness is increased in IL-13-stimulated pendrin-deficient MTEC cultures. a, Typical traces of fluorescence along the z-axis (and through the ASL) in unstimulated wild type MTEC cultures (Control / No IL-13, solid line) and IL-13-stimulated pendrin-deficient MTEC cultures (Slc26a4-/- / IL-13, dashed line). A trace generated using a calibration sample of known thickness (40 μm, dotted line) is shown for comparison. b, Effects of IL-13 on ASL thickness in control and pendrin-deficient (Slc26a4-/-) MTEC cultures. Results are means determined from all wells analyzed in 3 separate experiments that each produced similar results (n = 14-15 wells per condition). Error bars represent s.e.m. ** p < 0.01 vs. Control / No IL-13; †† p < 0.01 vs. Control / IL-13.

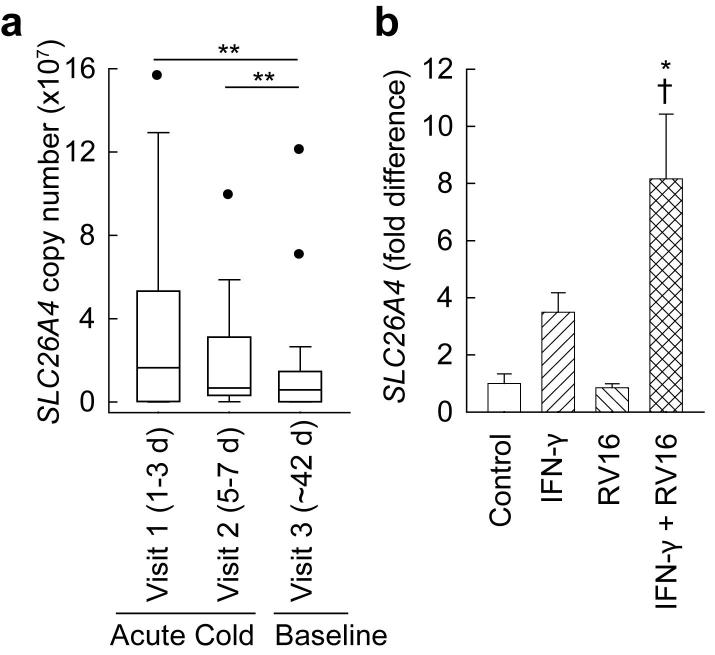

SLC26A4 expression in nasal epithelial cells is increased during common colds

Nasal mucosa samples were collected from asthmatic and non-asthmatic human subjects at three time points after onset of cold symptoms. Samples from 22 subjects with confirmed rhinovirus infection were analyzed for this study. The characteristics of the subjects are shown in Table 1.

Table I.

Subject characteristics

| Characteristic | Non-asthmatics (n = 7) | Asthmatics (n = 15) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 30.3 ± 3.3 | 33.7 ± 2.5 | 0.25 |

| Female:male | 4:3 | 13:2 | 0.16 |

| FEV1a (liters) | 3.6 ± 0.2 | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 0.05 |

| FEV1 (% predicted) | 98.1 ± 1.5 | 94.2 ± 2.8 | 0.40 |

| Methacholine PC20b (mg/ml) | 15.7 ± 8.0 | 4.8 ± 1.6 | 0.02 |

| Atopic by skin test (%) | 43% | 66% | 0.28 |

| Nasal cold symptom score | 65.2 ± 11.6 | 45.0 ± 8.6 | 0.09 |

| Chest cold symptom score | 44.3 ± 16.3 | 66.9 ± 14.6 | 0.37 |

FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s.

PC20: provocative dose of methacholine causing a 20% fall in FEV1.

There were no obvious differences between non-asthmatic and asthmatic subjects or between non-atopic and atopic, but there were relatively small numbers of subjects in these subgroups. When data from all 22 subjects were analyzed together (Fig. 6a), we found that SLC26A4 mRNA expression was significantly increased during acute colds (at visit 1, 1-3 d after onset of symptoms and visit 2, 5-7 d after onset of symptoms) compared with a later time long after resolution of symptoms (visit 3, ∼42 d after onset of symptoms). Mean SLC26A4 expression was 4.9-fold higher at visit 1 and 2.2-fold higher at visit 2 compared with visit 3.

FIGURE 6.

SLC26A4 is increased in nasal epithelial cells during common colds. a, Boxplots representing SLC26A4 expression during common colds (1-3 d and 5-7 d after onset) and at baseline (∼42 days after onset). Normalized gene copy number was determined by quantitative RT-PCR. Data are from n = 22 subjects, including 15 subjects with asthma. ** p < 0.01 vs. Visit 3. b, Effects of RV16 and IFN-γ on SLC26A4 expression in NHBE cells. Cells were infected with RV16 and/or stimulated with 10 ng/ml IFN-γ for 24 h as indicated. Results are means and error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3 wells per condition.* p < 0.05 vs. Control, † p < 0.05 vs. RV16 alone.

The combination of RV16 and IFN-γ increases SLC26A4 mRNA in NHBE cells

To determine whether rhinovirus directly increases SLC26A4 mRNA expression in human airway epithelial cells, we infected NHBE cells with RV16 in vitro. Under the conditions we used, RV16 infection alone had no effect on SLC26A4 mRNA expression (Fig. 6b). We considered the possibility that cytokines produced by other cells during rhinovirus infection contribute to SLC26A4 mRNA induction in vivo. Rhinovirus stimulates production of IFN-γ by mononuclear cells (8, 43-45) and we found that many genes known to be induced by IFN-γ were markedly upregulated in nasal epithelial cells during common colds (unpublished data). IFN-γ alone had a small but non-significant effect on SLC26A4 mRNA expression. However, the combination of RV16 infection and IFN-γ stimulation caused a larger and statistically significant effect on SLC26A4 expression in NHBE cells.

Discussion

The results of our studies of a mouse allergic airway disease model and of human subjects with rhinovirus infection implicate pendrin in airway dysfunction during asthma exacerbations. In the allergic model, we previously showed that Slc26a4 mRNA expression was markedly increased in response to Th2 cytokines (26). Here we show that pendrin makes a significant contribution to allergen-induced airway hyperreactivity and airway inflammation in this model. Both airway hyperreactivity and inflammation have been shown to be influenced by ASL hydration in other models (17), and we found that pendrin expression affects ASL thickness in MTEC cultures. Furthermore, we demonstrated that SLC26A4 mRNA was upregulated in human subjects during naturally-occurring colds caused by rhinovirus, suggesting that changes in pendrin expression may be important not only for allergen-induced exacerbations but also for viral infections, the most common triggers of asthma exacerbations.

Allergen-induced airway hyperreactivity and inflammation were reduced in pendrin-deficient mice. These effects cannot be explained by a generalized defect in the allergic response, since production of OVA-specific IgE, mucus, and Th2 cytokine mRNAs was unaffected by pendrin deficiency. Instead, it seems likely that pendrin deficiency affects hyperreactivity and inflammation due to its effects on ASL. A causal association between ASL dehydration and airway inflammation and obstruction has been established in cystic fibrosis (16) and in transgenic mice overexpressing ENaC (17). In allergic airway disease, IL-13 stimulation causes increased production of mucus (11) along with increased secretion of ions and water (18). We found that pendrin-deficient MTEC cultures were better hydrated (had thicker ASL) than control cells following IL-13 stimulation, and this may facilitate mucus clearance and improve airway function. Mechanistic relationships between ASL hydration, airway inflammation, and airway obstruction and hyperreactivity are complex and incompletely understood despite extensive analysis of various asthma and cystic fibrosis models. It is clear that airway epithelial cells can affect inflammation by producing cytokines that affect maturation and recruitment of eosinophils and other leukocytes (46). We examined expression of mRNAs encoding cytokines that are induced in the allergic model and are known to play a role in eosinophil recruitment, including IL-5 (Fig. 2c) and the chemokines CCL2 (MCP-1), CCL11 (eotaxin-1), and CCL24 (eotaxin-2) (data not shown), but found no differences in pendrin-deficient mice. We cannot formally exclude the possibility that other pendrin-expressing cells in the lung are involved in allergic airway disease, but we are not aware of reports of pendrin expression in cells other than epithelial cells and we detected minimal if any Slc26a4 mRNA in BAL fluid inflammatory cells (not shown). Our findings are consistent with the hypothesis that pendrin’s effects on inflammation and airway reactivity are due to direct effects on ASL, although other explanations for these effects cannot be excluded.

Nakao and colleagues have very recently described the results of other, complementary approaches to studying the role of pendrin in airway disease (33). These investigators found that forced expression of pendrin using a Sendai virus vector led to increased expression of mucus. We found no effect of pendrin deficiency on levels of mucus in response to allergen challenge using a highly quantitative stereology-based approach, indicating that pendrin expression is not required for allergen-induced mucus production in this model. Similar results were reported in studies of another allergen-induced epithelial cell gene, Clca3 (Gob-5): overexpression led to increased mucus production (21, 24) but gene deletion had no effect on mucus production in response to allergen challenge (22, 24). This may be explained by the existence of redundant pathways leading to mucus production (24). Nakao and colleagues also found that forced expression of pendrin caused airway inflammation and hyperreactivity (33). Our findings of decreased inflammation and hyperreactivity in allergen-challenged pendrin-deficient mice provide additional evidence for the involvement of pendrin in these processes and show that pathological responses to allergen are diminished when pendrin is absent.

We found that pendrin deficiency affected ASL in a manner consistent with what is known about pendrin function outside the lung. Heterologous expression of pendrin in Xenopus oocytes (47), Sf9 insect cells (47), HEK-293 kidney cells (48), and Fischer rat thyroid cells (32) has been shown to increase transport of chloride and other ions. Studies of pendrin-deficient mice established that pendrin contributes to absorption of chloride and water in the ear and the kidney. In the inner ear, pendrin is expressed at high levels and deficiency of pendrin results in impaired chloride and water uptake from endolymph (30). In the kidney, pendrin has no detectable effects on renal function or fluid or electrolyte balance under normal conditions (49). However, mineralocorticoid administration results in a substantial increase in pendrin expression by cortical collecting duct cells (50). Mineralocorticoids caused hypertension and weight gain in wild type mice but not in pendrin-deficient mice, indicating that mineralocorticoid-induced pendrin expression leads to increased chloride and water absorption in the kidney (50). Similarly, we found that the effect of pendrin on ASL thickness in MTEC cultures was only apparent after stimulation with IL-13, which substantially increased pendrin expression. IL-13 increased ASL thickness in both control and pendrin-deficient MTEC cultures, likely due to multiple effects on expression of ion transporters including reduced expression of ENaC. The increase in ASL was significantly larger in pendrin-deficient MTEC cultures, which is consistent with the hypothesis that pendrin, which localizes to the apical membrane of airway epithelial cells (33), increases total chloride uptake and water absorption in these cells. However, other direct or indirect effects of pendrin on absorption or secretion of ions and water might also account for our findings. In any case, our findings demonstrate that pendrin expression has a significant effect on ASL thickness after IL-13 stimulation.

We found that naturally-occurring colds caused by rhinovirus, a very common trigger of exacerbations, were associated with increased expression of SLC26A4. Our in vitro studies of NHBE cells indicate that the combination of direct effects of rhinovirus on NHBE cells and indirect effects mediated by IFN-γ, a cytokine produced by leukocytes during rhinovirus infections, could account for this increase. In addition, the present study confirms that allergen, another trigger of asthma exacerbations, increases Slc26a4 mRNA expression in mice. We have also reported that lung expression of Slc26a4 is increased in mouse models of bacterial infection (51), where the recently reported (32) ability of pendrin to secrete thiocyanate, an anion with a role in antimicrobial defense, may be important. These results suggest that increases in pendrin expression could contribute to inflammation and airway dysfunction in viral infections, thought to be the predominant cause of asthma exacerbations, as well as in bacterial infections and allergen-induced exacerbations. We previously reported that bronchial epithelial expression of SLC26A4 was not increased in human subjects with stable, mild to moderate asthma compared to healthy, non-asthmatic controls (26). This suggests that pendrin plays a more important role in airway dysfunction during asthma exacerbations than during stable asthma.

Inhibition of pendrin could be an effective strategy for treatment of asthma exacerbations. General evidence in support of strategies designed to augment ASL comes from a recent demonstration that inhalation of hypertonic saline had beneficial effects in cystic fibrosis (52). Pendrin is one of several molecules which regulate ASL and represent possible therapeutic targets in asthma and other airway diseases. For treatment of cystic fibrosis and chronic bronchitis, considerable efforts have been made to develop therapies designed to increase ASL by inhibiting ENaC (53) or stimulating Cl- channels (54), although these compounds have not yet succeeded in clinical trials (13). Niflumic acid, an inhibitor of calcium-activated chloride channels, had beneficial effects in both allergic (55) and IL-13-induced (56) models of asthma, but it is not yet clear whether effects of niflumic acid are due to inhibition of chloride channels or other effects of this drug (23). Pendrin presents a potential alternative therapeutic target for asthma exacerbations. Inhibition of pendrin in the ear, kidney, or thyroid might have undesirable effects, but these could likely be minimized by delivering aerosolized drug directly to the airway. Since pendrin is involved in thiocyanate secretion (32), it will also be important to examine whether pendrin inhibition impairs host defense. The results reported here provide a basis for future studies aimed at developing and testing pendrin inhibitors for use in asthma exacerbations.

Acknowledgements

We thank Alan S. Verkman (UCSF) for advice; Eric D. Green (National Institutes of Health) for providing pendrin-deficient mice; Koret Hirschberg (Tel Aviv University) for critical comments; Steven L. Brody (Washington University School of Medicine) for MTEC protocols; Kurt Thorn (UCSF Nikon Imaging Center) for supporting confocal microscopy experiments; Rebecca Barbeau, Andrea Barczak, Lucy Bernstein, Rosemary Garrett-Young, Xin Ren, Yanli Wang, and Weihong Xu for technical support; Theresa Ward, Hofer Wong and Peggy Cadbury for recruiting the subjects; Amy Kistler, Joseph DeRisi and Hyun-Do Jo for virus identification in clinical samples; and Jane Liu, Samantha Donnelly and Junquing Shen for processing clinical samples and assisting with NHBE cell experiments.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HL085089 and AI50496, the UCSF Sandler Asthma Basic Research Center and the Ernest S. Bazley Grant to Northwestern University.

- ASL

- airway surface liquid

- CLCA1

- chloride channel calcium activated 1

- Slc26a4

- solute carrier family 26 member 4

- NHBE

- normal human bronchial epithelial

- MTEC

- mouse tracheal epithelial cells

- BAL

- bronchoalveolar lavage

- Scnn1a

- sodium channel, nonvoltage-gated, type I, α

- Cftr

- cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

- Ct

- threshold cycle

- RV16

- rhinovirus serotype 16

- ENaC

- epithelial sodium channel

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is an author-produced version of a manuscript accepted for publication in The Journal of Immunology (The JI). The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. (AAI), publisher of The JI, holds the copyright to this manuscript. This version of the manuscript has not yet been copyedited or subjected to editorial proofreading by The JI; hence, it may differ from the final version published in The JI (online and in print). AAI (The JI) is not liable for errors or omissions in this author-produced version of the manuscript or in any version derived from it by the U.S. National Institutes of Health or any other third party. The final, citable version of record can be found at www.jimmunol.org.

References

- 1.Bousquet J, Jeffery PK, Busse WW, Johnson M, Vignola AM. Asthma. From bronchoconstriction to airways inflammation and remodeling. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2000;161:1720–1745. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.5.9903102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green RM, Custovic A, Sanderson G, Hunter J, Johnston SL, Woodcock A. Synergism between allergens and viruses and risk of hospital admission with asthma: case-control study. Bmj. 2002;324:763. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7340.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Papadopoulos NG, Papi A, Psarras S, Johnston SL. Mechanisms of rhinovirus-induced asthma. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2004;5:255–260. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray CS, Poletti G, Kebadze T, Morris J, Woodcock A, Johnston SL, Custovic A. Study of modifiable risk factors for asthma exacerbations: virus infection and allergen exposure increase the risk of asthma hospital admissions in children. Thorax. 2006;61:376–382. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.042523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ordonez CL, Khashayar R, Wong HH, Ferrando R, Wu R, Hyde DM, Hotchkiss JA, Zhang Y, Novikov A, Dolganov G, Fahy JV. Mild and moderate asthma is associated with airway goblet cell hyperplasia and abnormalities in mucin gene expression. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2001;163:517–523. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.2.2004039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuyper LM, Pare PD, Hogg JC, Lambert RK, Ionescu D, Woods R, Bai TR. Characterization of airway plugging in fatal asthma. Am. J. Med. 2003;115:6–11. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00241-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mallia P, Johnston SL. How viral infections cause exacerbation of airway diseases. Chest. 2006;130:1203–1210. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.4.1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gern JE, Vrtis R, Grindle KA, Swenson C, Busse WW. Relationship of upper and lower airway cytokines to outcome of experimental rhinovirus infection. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2000;162:2226–2231. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.6.2003019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sauty A, Dziejman M, Taha RA, Iarossi AS, Neote K, Garcia-Zepeda EA, Hamid Q, Luster AD. The T cell-specific CXC chemokines IP-10, Mig, and I-TAC are expressed by activated human bronchial epithelial cells. J. Immunol. 1999;162:3549–3558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuperman DA, Huang X, Nguyenvu L, Holscher C, Brombacher F, Erle DJ. IL-4 receptor signaling in Clara cells is required for allergen-induced mucus production. J. Immunol. 2005;175:3746–3752. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuperman DA, Huang X, Koth LL, Chang GH, Dolganov GM, Zhu Z, Elias JA, Sheppard D, Erle DJ. Direct effects of interleukin-13 on epithelial cells cause airway hyperreactivity and mucus overproduction in asthma. Nat. Med. 2002;8:885–889. doi: 10.1038/nm734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wenzel S, Wilbraham D, Fuller R, Getz EB, Longphre M. Effect of an interleukin-4 variant on late phase asthmatic response to allergen challenge in asthmatic patients: results of two phase 2a studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1422–1431. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61600-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boucher RC. Relationship of airway epithelial ion transport to chronic bronchitis. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2004;1:66–70. doi: 10.1513/pats.2306018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blouquit-Laye S, Chinet T. Ion and liquid transport across the bronchiolar epithelium. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2007;159:278–282. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tarran R, Grubb BR, Gatzy JT, Davis CW, Boucher RC. The relative roles of passive surface forces and active ion transport in the modulation of airway surface liquid volume and composition. J. Gen. Physiol. 2001;118:223–236. doi: 10.1085/jgp.118.2.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boucher RC. Airway surface dehydration in cystic fibrosis: pathogenesis and therapy. Annu. Rev. Med. 2007;58:157–170. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.58.071905.105316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mall M, Grubb BR, Harkema JR, O’Neal WK, Boucher RC. Increased airway epithelial Na+ absorption produces cystic fibrosis-like lung disease in mice. Nat. Med. 2004;10:487–493. doi: 10.1038/nm1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Danahay H, Atherton H, Jones G, Bridges RJ, Poll CT. Interleukin-13 induces a hypersecretory ion transport phenotype in human bronchial epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2002;282:L226–236. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00311.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woodruff PG, Boushey HA, Dolganov GM, Barker CS, Yang YH, Donnelly S, Ellwanger A, Sidhu SS, Dao-Pick TP, Pantoja C, Erle DJ, Yamamoto KR, Fahy JV. Genome-wide profiling identifies epithelial cell genes associated with asthma and with treatment response to corticosteroids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:15858–15863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707413104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loewen ME, Forsyth GW. Structure and function of CLCA proteins. Physiol. Rev. 2005;85:1061–1092. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00016.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakanishi A, Morita S, Iwashita H, Sagiya Y, Ashida Y, Shirafuji H, Fujisawa Y, Nishimura O, Fujino M. Role of gob-5 in mucus overproduction and airway hyperresponsiveness in asthma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:5175–5180. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081510898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robichaud A, Tuck SA, Kargman S, Tam J, Wong E, Abramovitz M, Mortimer JR, Burston HE, Masson P, Hirota J, Slipetz D, Kennedy B, O’Neill G, Xanthoudakis S. Gob-5 is not essential for mucus overproduction in preclinical murine models of allergic asthma. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2005;33:303–314. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0372OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erle DJ, Zhen G. The asthma channel? Stay tuned. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2006;173:1181–1182. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2603006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel AC, Morton JD, Kim EY, Alevy Y, Swanson S, Tucker J, Huang G, Agapov E, Phillips TE, Fuentes ME, Iglesias A, Aud D, Allard JD, Dabbagh K, Peltz G, Holtzman MJ. Genetic segregation of airway disease traits despite redundancy of calcium-activated chloride channel family members. Physiol. Genomics. 2006;25:502–513. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00321.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dolganov GM, Woodruff PG, Novikov AA, Zhang Y, Ferrando RE, Szubin R, Fahy JV. A novel method of gene transcript profiling in airway biopsy homogenates reveals increased expression of a Na+-K+-Cl- cotransporter (NKCC1) in asthmatic subjects. Genome Res. 2001;11:1473–1483. doi: 10.1101/gr.191301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuperman DA, Lewis CC, Woodruff PG, Rodriguez MW, Yang YH, Dolganov GM, Fahy JV, Erle DJ. Dissecting asthma using focused transgenic modeling and functional genomics. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2005;116:305–311. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Everett LA, Morsli H, Wu DK, Green ED. Expression pattern of the mouse ortholog of the Pendred’s syndrome gene (Pds) suggests a key role for pendrin in the inner ear. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:9727–9732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soleimani M. Molecular physiology of the renal chloride-formate exchanger. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2001;10:677–683. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200109000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Everett LA, Glaser B, Beck JC, Idol JR, Buchs A, Heyman M, Adawi F, Hazani E, Nassir E, Baxevanis AD, Sheffield VC, Green ED. Pendred syndrome is caused by mutations in a putative sulphate transporter gene (PDS) Nat. Genet. 1997;17:411–422. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Everett LA, Belyantseva IA, Noben-Trauth K, Cantos R, Chen A, Thakkar SI, Hoogstraten-Miller SL, Kachar B, Wu DK, Green ED. Targeted disruption of mouse Pds provides insight about the inner-ear defects encountered in Pendred syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:153–161. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhen G, Park SW, Nguyenvu LT, Rodriguez MW, Barbeau R, Paquet AC, Erle DJ. IL-13 and epidermal growth factor receptor have critical but distinct roles in epithelial cell mucin production. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2007;36:244–253. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0180OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pedemonte N, Caci E, Sondo E, Caputo A, Rhoden K, Pfeffer U, Di Candia M, Bandettini R, Ravazzolo R, Zegarra-Moran O, Galietta LJ. Thiocyanate transport in resting and IL-4-stimulated human bronchial epithelial cells: role of pendrin and anion channels. J. Immunol. 2007;178:5144–5153. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.5144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakao I, Kanaji S, Ohta S, Matsushita H, Arima K, Yuyama N, Yamaya M, Nakayama K, Kubo H, Watanabe M, Sagara H, Sugiyama K, Tanaka H, Toda S, Hayashi H, Inoue H, Hoshino T, Shiraki A, Inoue M, Suzuki K, Aizawa H, Okinami S, Nagai H, Hasegawa M, Fukuda T, Green ED, Izuhara K. Identification of pendrin as a common mediator for mucus production in bronchial asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Immunol. 2008;180:6262–6269. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.6262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim YH, Pech V, Spencer KB, Beierwaltes WH, Everett LA, Green ED, Shin W, Verlander JW, Sutliff RL, Wall SM. Reduced ENaC protein abundance contributes to the lower blood pressure observed in pendrin-null mice. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2007;293:F1314–1324. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00155.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen C, Huang X, Sheppard D. ADAM33 is not essential for growth and development and does not modulate allergic asthma in mice. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;26:6950–6956. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00646-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Myou S, Leff AR, Myo S, Boetticher E, Tong J, Meliton AY, Liu J, Munoz NM, Zhu X. Blockade of inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness in immune-sensitized mice by dominant-negative phosphoinositide 3-kinase-TAT. J. Exp. Med. 2003;198:1573–1582. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.You Y, Richer EJ, Huang T, Brody SL. Growth and differentiation of mouse tracheal epithelial cells: selection of a proliferative population. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2002;283:L1315–1321. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00169.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jayaraman S, Song Y, Vetrivel L, Shankar L, Verkman AS. Noninvasive in vivo fluorescence measurement of airway-surface liquid depth, salt concentration, and pH. J. Clin. Invest. 2001;107:317–324. doi: 10.1172/JCI11154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Avila PC, Abisheganaden JA, Wong H, Liu J, Yagi S, Schnurr D, Kishiyama JL, Boushey HA. Effects of allergic inflammation of the nasal mucosa on the severity of rhinovirus 16 cold. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2000;105:923–932. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.106214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kistler A, Avila PC, Rouskin S, Wang D, Ward T, Yagi S, Schnurr D, Ganem D, DeRisi JL, Boushey HA. Pan-viral screening of respiratory tract infections in adults with and without asthma reveals unexpected human coronavirus and human rhinovirus diversity. J. Infect. Dis. 2007;196:817–825. doi: 10.1086/520816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Matsushita K, McCray PB, Jr., Sigmund RD, Welsh MJ, Stokes JB. Localization of epithelial sodium channel subunit mRNAs in adult rat lung by in situ hybridization. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;271:L332–339. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1996.271.2.L332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gern JE, Vrtis R, Kelly EA, Dick EC, Busse WW. Rhinovirus produces nonspecific activation of lymphocytes through a monocyte-dependent mechanism. J. Immunol. 1996;157:1605–1612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Konno S, Grindle KA, Lee WM, Schroth MK, Mosser AG, Brockman-Schneider RA, Busse WW, Gern JE. Interferon-gamma enhances rhinovirus-induced RANTES secretion by airway epithelial cells. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2002;26:594–601. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.26.5.4438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brooks GD, Buchta KA, Swenson CA, Gern JE, Busse WW. Rhinovirus-induced interferon-gamma and airway responsiveness in asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2003;168:1091–1094. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200306-737OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schleimer RP, Kato A, Kern R, Kuperman D, Avila PC. Epithelium: at the interface of innate and adaptive immune responses. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2007;120:1279–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.08.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scott DA, Wang R, Kreman TM, Sheffield VC, Karniski LP. The Pendred syndrome gene encodes a chloride-iodide transport protein. Nat. Genet. 1999;21:440–443. doi: 10.1038/7783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Soleimani M, Greeley T, Petrovic S, Wang Z, Amlal H, Kopp P, Burnham CE. Pendrin: an apical Cl-/OH-/HCO3- exchanger in the kidney cortex. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2001;280:F356–364. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.280.2.F356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Royaux IE, Wall SM, Karniski LP, Everett LA, Suzuki K, Knepper MA, Green ED. Pendrin, encoded by the Pendred syndrome gene, resides in the apical region of renal intercalated cells and mediates bicarbonate secretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:4221–4226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071516798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Verlander JW, Hassell KA, Royaux IE, Glapion DM, Wang ME, Everett LA, Green ED, Wall SM. Deoxycorticosterone upregulates PDS (Slc26a4) in mouse kidney: role of pendrin in mineralocorticoid-induced hypertension. Hypertension. 2003;42:356–362. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000088321.67254.B7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lewis CC, Yang JY, Huang X, Banerjee SK, Blackburn MR, Baluk P, McDonald DM, Blackwell TS, Nagabhushanam V, Peters W, Voehringer D, Erle DJ. Disease-specific gene expression profiling in multiple models of lung disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2008;177:376–387. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200702-333OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Donaldson SH, Bennett WD, Zeman KL, Knowles MR, Tarran R, Boucher RC. Mucus clearance and lung function in cystic fibrosis with hypertonic saline. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;354:241–250. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hirsh AJ, Molino BF, Zhang J, Astakhova N, Geiss WB, Sargent BJ, Swenson BD, Usyatinsky A, Wyle MJ, Boucher RC, Smith RT, Zamurs A, Johnson MR. Design, synthesis, and structure-activity relationships of novel 2-substituted pyrazinoylguanidine epithelial sodium channel blockers: drugs for cystic fibrosis and chronic bronchitis. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:4098–4115. doi: 10.1021/jm051134w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Singh S, Syme CA, Singh AK, Devor DC, Bridges RJ. Benzimidazolone activators of chloride secretion: potential therapeutics for cystic fibrosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2001;296:600–611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou Y, Shapiro M, Dong Q, Louahed J, Weiss C, Wan S, Chen Q, Dragwa C, Savio D, Huang M, Fuller C, Tomer Y, Nicolaides NC, McLane M, Levitt RC. A calcium-activated chloride channel blocker inhibits goblet cell metaplasia and mucus overproduction. Novartis Found. Symp. 2002;248:150–165. discussion 165-170, 277-182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nakano T, Inoue H, Fukuyama S, Matsumoto K, Matsumura M, Tsuda M, Matsumoto T, Aizawa H, Nakanishi Y. Niflumic acid suppresses interleukin-13-induced asthma phenotypes. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2006;173:1216–1221. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200410-1420OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]