Abstract

Background

The use of ice as a supplement to an exercise programme has been recommended for the management of lateral elbow tendinopathy (LET). No studies have examined its effectiveness.

Objectives

To investigate whether an exercise programme supplemented with ice is more successful than the exercise programme alone in treating patients with LET.

Methods

Patients with unilateral LET for at least four weeks were included in this pilot study. They were sequentially allocated to receive five times a week for four weeks either an exercise programme with ice or the exercise programme alone. The exercise programme consisted of slow progressive eccentric exercises of wrist extensors and static stretching of the extensor carpi radialis brevis tendon. In the exercise programme/ice group, the ice was applied after the exercise programme for 10 minutes in the form of an ice bag to the facet of the lateral epicondyle. Patients were evaluated at baseline, at the end of treatment, and three months after the end of treatment. Outcome measures used were the pain visual analogue scale and the dropout rate.

Results

Forty patients met the inclusion criteria. At the end of treatment there was a decline in visual analogue scale of about 7 units in both groups compared with baseline (p<0.0005, paired t test). There were no significant differences in the magnitude of reduction between the groups at the end of treatment and at the three month follow up (p<0.0005, independent t test). There were no dropouts.

Conclusions

An exercise programme consisting of eccentric and static stretching exercises had reduced the pain in patients with LET at the end of the treatment and at the follow up whether or not ice was included. Further research to establish the relative, absolute, and cost effectiveness as well as the mechanism of action of the exercise programme is needed.

Keywords: lateral elbow tendinopathy, tennis elbow, exercise programme, eccentric training, stretching, cryotherapy

Lateral elbow tendinopathy (LET) commonly referred to as lateral epicondylitis and/or tennis elbow, is one of the most common lesions of the arm. The origin of the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) is the most commonly affected structure.1 LET is usually defined as a syndrome of pain in the area of the lateral epicondyle2,3,4 and is a degenerative or failed healing tendon response characterised by the increased presence of fibroblasts, vascular hyperplasia, increased amounts of proteoglycans and glycosaminoglycans, and disorganised collagen.1,4 It is generally a work related or sport related pain disorder usually caused by excessive quick, monotonous, repetitive motions of the wrist.5 The dominant arm is commonly affected, with a prevalence of 1–3% in the general population.6 The peak prevalence of LET is between 30 and 60 years.4,7 The disorder appears to be of longer duration and severity in women.4,7,8

The main symptoms are pain and decreased function, both of which may affect activities of daily living. Diagnosis can be confirmed by tests that reproduce the pain, such as palpation over the facet of the lateral epicondyle, resisted wrist extension, resisted middle finger extension, and passive wrist flexion.3

However, no ideal treatment has emerged for the management of LET. Many clinicians advocate a conservative approach as the choice of treatment for LET.9,10,11,12 Physiotherapy is a conservative treatment that is usually recommended.11,13,14 A wide array of physiotherapy treatments has been recommended for the management of LET such as electrotherapeutic modalities, exercise programmes, soft tissue manipulation, and manual techniques.11,15,16,17 These treatments have different theoretical mechanisms of action, but all have the same aim, to reduce pain and improve function. Such a variety of treatment options suggests that the optimal treatment strategy is not known, and more research is needed to discover the most effective treatment in patients with LET.

One of the most common physiotherapy treatments for LET is an exercise programme.10,12,13 One consisting of eccentric and static stretching exercises has shown good clinical results in LET18 as well as in conditions similar to LET in clinical behaviour and histopathological appearance, such as patellar19,20 and Achilles 21,22,23,24,25,26 tendinopathy. Such an exercise programme is used as the first treatment option for our patients.27 Some clinicians recommend the use of ice for 10–15 minutes as a supplement to the exercise programme.28,29 To our knowledge, there have been no studies of the latter. The aim of this study was to compare the clinical results of the use of ice after the exercise programme with those of the exercise programme alone in patients with LET.

Materials and methods

A controlled, monocentre trial was conducted in a clinical setting over 21 months to assess the effectiveness of an exercise programme alone or with ice in patients with LET. A parallel group design was used because crossover designs are limited in situations where patients are cured by the intervention and do not have the opportunity to receive the other treatments after crossover.30 One investigator (PM) administered the treatments, evaluated the patients to confirm the LET diagnosis, performed all baseline and follow up assessments, and obtained informed consent.

Patients over 18 years old with lateral elbow pain were examined and evaluated in a private outpatient physiotherapy clinic in Ithaki between January 2003 and June 2004. All patients lived in Ithaki, Greece, were native Greek speakers, and were either self referred or referred by their doctor or physiotherapist.

Patients were included in the study if, at the time of presentation, they had been evaluated as having clinically diagnosed LET for at least four weeks. Patients were included in the trial if they reported (a) pain on the facet of the lateral epicondyle when palpated, (b) less pain during resistance supination with the elbow in 90° of flexion rather than in full extension,1 and (c) pain in at least two of the following four tests:3

Tomsen test

Resisted middle finger test

Mill's test

Handgrip dynamometer test

Patients were excluded from the study if they had one or more of the following conditions: (a) dysfunction in the shoulder, neck and/or thoracic region; (b) local or generalised arthritis; (c) neurological deficit; (d) radial nerve entrapment; (e) limitations in arm functions; (f) the affected elbow had been operated on; (g) had received any conservative treatment for the management of LET in the four weeks before entering the study.3,5,31

All patients received a written explanation of the trial before entry into the study and then gave signed consent to participate. They were allocated to two groups by sequential allocation. For example, the first patient with LET was assigned to the exercise programme/ice group, the second patient with LET to the exercise programme alone group, and so on.

All patients were instructed to use their arm during the course of the study but to avoid activities that irritated the elbow such as shaking hands, grasping, lifting, knitting, handwriting, driving a car, and using a screwdriver. They were also told to refrain from taking anti‐inflammatory drugs throughout the course of study. Patient compliance with this request was monitored using a treatment diary.

The exercise programme consisted of slow progressive eccentric exercises of the wrist extensors and static stretching exercises of the ECRB tendon. Three sets of 10 repetitions of slow progressive eccentric exercises of the wrist extensors at each treatment session were performed, with one minute rest interval between each set. Static stretching exercises of the ECRB tendon were repeated six times at each treatment session, three times before and three times after the eccentric exercises, with a 30 second rest interval between each repetition. Eccentric exercises of the wrist extensors were performed with the elbow on the bed in full extension, the forearm in pronation, the wrist in an extended position (as high as possible), and the hand hanging over the edge of the bed. From this position, patients flexed their wrist slowly while counting to 30, then returned to the starting position with the help of the other hand. Patients were told to continue with the exercise even if they experienced mild pain. However, they were told to stop the exercise if the pain became disabling. When patients were able to perform the eccentric exercises without experiencing any minor pain or discomfort, the load was increased using free weights. Static stretching exercises of the ECRB tendon were performed with the help of the therapist (PM). The therapist placed the elbow of the patient in full extension, the forearm in full pronation, and the wrist in flexion and ulnar deviation according to the patient's tolerance. This position was held for 30–45 seconds each time and then released. The exercise programme was given five times a week for four weeks and was individualised on the basis of the patient's description of pain experienced during the procedure. In the exercise programme/ice group, the ice was applied after the exercise programme for 10 minutes in the form of an ice bag to the painful area (facet of lateral epicondyle).

Pain and dropout rate were measured in this study. Each patient was evaluated at the baseline (week 0), at the end of treatment (week 4), and three months (week 16) after the end of treatment in order to see the intermediate effects of the treatments.

Pain was measured on a visual analogue scale (VAS), where 0 (cm) was “least pain imaginable” and 10 (cm) was “worst pain imaginable”. The pain VAS was used to measure the patient's worst level of pain over the 24 hours before each evaluation, and this approach has been shown to be valid and sensitive.32

The dropout rate was also used as an indicator of treatment outcome. Dropouts were categorised as follows: (a) withdrawal without reason; (b) did not return for follow up; (c) request for an alternative treatment.

The change from baseline was calculated for each follow up. Differences between groups were determined using the independent t test. The difference within groups between baseline and end of treatment was analysed with a paired t test. A 5% level of probability was adopted as the level for statistical significance. SPSS 11.5 statistical software was used for the statistical analysis.

Results

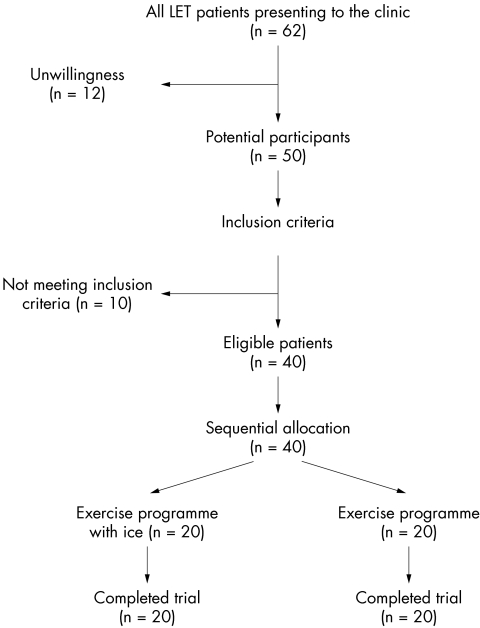

Sixty two patients eligible for inclusion visited the clinic within the trial period. Twelve were unwilling to participate in the study, and 10 did not meet the inclusion criteria described above. The other 40 patients were sequentially allocated to one of the two possible groups: (a) exercise programme and ice (n = 20; seven men, 13 women; mean (SD) age 43.14 (6.15) years); (b) exercise programme alone (n = 20; six men, 14 women; mean (SD) age 42.57 (6.31) years). Patient flow through the trial is summarised in a CONSORT flow chart (fig 1).

Figure 1 Flow chart of the study.

At baseline there were more women in the groups (14 more in total). The mean age of the patients was about 40 years, and the duration of LET was about four months. LET was in the dominant arm in 85% of patients. There were no significant differences in mean age (p>0.0005, independent t test) or the mean duration of symptoms (p>0.0005, independent t test) between the groups. Patients had received a wide range of previous treatments (table 1). Drug therapy had been tried by 55%. All patients were manual workers.

Table 1 Previous treatments of participants.

| Exercise programme and ice | Exercise programme | |

|---|---|---|

| Drugs | 12 (60) | 11 (55) |

| Physiotherapy | 4 (20) | 4 (20) |

| Injection | 4 (20) | 5 (25) |

Values are number (%).

Baseline pain on VAS was 8.70 (95% confidence interval 8.42 to 8.98) for the whole sample (n = 40) (table 2). There were no significant differences between the groups for baseline pain (p>0.05 independent t test; table 2). At week 4 there was a decline in VAS of about 7 units in both groups compared with the baseline (p<0.0005, paired t test; table 3). There were no significant differences in the magnitude of reduction between the groups at week 4 and week 16 (p<0.0005 independent t test; table 3).

Table 2 Pain over the 24 hours before each evaluation.

| Week 0 | Week 4 | Week 16 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exercise programme and ice | 8.60 (8.22 to 8.98) | 1.70 (0.99 to 2.41) | 1.50 (0.94 to 2.06) |

| Exercise programme | 8.80 (8.35 to 9.25) | 1.90 (1.08 to 2.72) | 1.60 (0.83 to 2.37) |

Values are mean (95% confidence interval) visual analogue scores where 0 = least pain imaginable and 10 = worst pain imaginable.

Table 3 Change in pain over the 24 hours before each evaluation from baseline.

| Exercise programme and ice | Exercise programme | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Week 4 | −6.90 | −6.90 | >0.0005 |

| Week 16 | −7.10 | −7.10 | >0.0005 |

Values are mean visual analogue scores where 0 = least pain imaginable and 10 = worst pain imaginable. p Values for independent t test on change in VAS from baseline are shown.

There were no dropouts and all patients successfully completed the study.

Discussion

The results obtained from this pilot trial are novel, as to date there have been no data comparing the effectiveness of an exercise programme with ice and an exercise programme alone for the reduction of pain in LET.

The ice may decrease the extravasation of blood and protein from new capillaries found in tendinopathy as well as decreasing the metabolic rate of the tendon.33 Both mechanisms promote healing of LET. In addition, ice can be used for symptomatic relief of pain. However, the findings of this trial indicate that ice as a supplement to the exercise programme offers no benefit in patients with LET. Therefore the reduction in pain at the end of the treatment and at the follow up was due to the exercise programme consisting of eccentric and static stretching exercises.

Standard eccentric exercises offer adequate rehabilitation for tendon disorders, but many patients with tendinopathies do not respond to this prescription alone.34 The load of eccentric exercises was increased according to the patients' symptoms because the opposite has shown poor results.35 Eccentric exercises were performed at a low speed in every treatment session because this allows tissue healing.1,21

Exercise programmes appear to reduce the pain and improve function, reversing the pathology of LET,36,37,38,39 as supported by experimental studies on animals.40 The way that an exercise programme achieves the goals remains uncertain as there is a lack of good quality evidence to confirm that physiological effects translate into clinically meaningful outcomes and vice versa.

There are two types of exercise programme: home exercise programmes and exercise programmes carried out in a clinical setting. A home exercise programme is commonly advocated for patients with tendinopathies such as LET because it can be performed any time during the day without requiring supervision from a physiotherapist. Our clinical experience, however, has shown that patients fail to comply with the regimen of home exercise programmes.27 This problem can be solved by exercise programmes performed in a clinical setting under the supervision of a physiotherapist. For the purposes of this report, “supervised exercise programme” will refer to such programmes.

This exercise programme has been used in previous clinical trials on LET.18,31,41,42,43,44,45,46 However, it was the sole treatment in only two previous trials.18,31 A home exercise programme was the sole treatment in one of these two,31 and was administered in a totally different manner from the supervised exercise programme used in the present controlled clinical trial and the study of Stasinopoulos et al.18 The differences were not only in the environment in which the exercise programmes were administered, but also in the development of the treatment protocol (type of exercises, intensity, frequency, duration of treatment). There is clearly a need for a clinical trial that would compare the effects of the supervised exercise programme treatment protocol, consisting of eccentric and static stretching exercises, with the home exercise programme treatment protocol used by Pienimaki et al.31

Previous trials have found that a home exercise programme reduced the pain in patellar19,20 and Achilles 21,22,23,24,25,26 tendinopathy. However, it was performed for about three months in all previous studies. In contrast, in the present controlled clinical trial and the studies of Stasinopoulos and colleagues,18,20 a supervised exercise programme was administered for a month. Thus it seems that the supervised exercise programme may give good long term clinical results in a shorter period of time than the home exercise programme. The most likely explanation for this difference is that a supervised exercise programme achieves a higher degree of patient compliance. Studies to compare the effects of these two exercise programmes are required to confirm the findings of the present controlled clinical trial.

What is already known on this topic

Many clinicians use ice as a supplement to an exercise programme consisting of eccentric and static stretching exercises for the management of lateral elbow tendinopathy

What this study adds

The findings of this trial indicate that supplementing the exercise programme with ice offers no benefit to patients with LET

Therefore the reduction in pain at the end of the treatment and at the three month follow up was due to the exercise programme alone

The present findings suggest that an exercise programme consisting of eccentric and static stretching exercises is adequate treatment for patients with LET. However, this trial does have some shortcomings. Firstly, a power analysis was not performed. Secondly, the samples were small and therefore the study was susceptible to lack of internal validity. Thirdly, although this study was not a randomised controlled trial because a genuine randomisation procedure was not followed, the use of sequential allocation to allocate patients to treatment groups allowed a true cause and effect relation to be demonstrated. Fourthly, the absence of a placebo/no treatment group meant that the study could not allow for normal fluctuations in the patients' symptoms, although LET is not a self limiting condition.5,47 Fifthly, the compliance of patients was not monitored when they were away from the clinic. Finally, the lack of blinding of patients, therapists, and assessor may be a reason for the effectiveness of the exercise programme. However, the blinding of patients and therapists would be problematic, if not impossible, because patients know if they are receiving the exercise programme treatment and therapists need to be aware of the treatment in order to administer it appropriately.

In addition to the weaknesses discussed, structural changes in the tendon related to treatment interventions were not shown; improvement in grip strength after the treatment interventions was not measured, and the long term effects (six months or more after the end of treatment) of these treatments were not investigated. Further research is needed to establish the effectiveness of an exercise programme in the management of LET.

Conclusions

Ice as a supplement to an exercise programme offers no benefit to patients with LET. The exercise programme, consisting of eccentric and static stretching exercises, had reduced the pain in patients with LET at the end of the treatment and at follow up. Controlled studies are needed to establish the effects and the mechanism of action of such an exercise programme in LET. A cost effectiveness analysis should be incorporated into the analysis of the effectiveness of the exercise programme in a future trial.

Abbreviations

ECRB - extensor carpi radialis brevis

LET - lateral elbow tendinopathy

VAS - visual analogue scale

Footnotes

Competing interests: none declared

This paper was presented at the 10th Symposium in Lixouri, Kefalonia entitled Athletic exercise doping, 3 September 2005.

References

- 1.Kraushaar B, Nirschl R. Current concepts review: tendinosis of the elbow (tennis elbow). Clinical features and findings of histological immunohistochemical and electron microscopy studies. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 199981259–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Assendelft W, Green S, Buchbinder R.et al Tennis elbow. BMJ 20037410327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haker E. Lateral epicondylalgia: diagnosis, treatment and evaluation. Critical Reviews in Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine 19935129–154. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vicenzino B, Wright A. Lateral epicondylalgia. I. Epidemiology, pathophysiology, aetiology and natural history. Phys Ther Rev 1996123–34. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vasseljen O. Low‐level laser versus traditional physiotherapy in the treatment of tennis elbow. Physiotherapy 199278329–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allander E. Prevalence, incidence and remission rates of some common rheumatic diseases and syndromes. Scand J Rheumatol 19743145–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verhaar J. Tennis elbow: Anatomical, epidemiological and therapeutic aspects. Int Orthop 199418263–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waugh E, Jaglal S, Davis A.et al Factors associated with prognosis of lateral epicondylitis after 8 weeks of physical therapy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 200485308–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noteboom T, Cruver S, Keller A.et al Tennis elbow: a review. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 199419357–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pienimaki T. Conservative treatment and rehabilitation of tennis elbow: a review article. Critical Reviews in Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine 200012213–228. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trudel D, Duley J, Zastrow I.et al Rehabilitations for patients with lateral epicondylitis: a systematic review. J Hand Ther 200417243–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wright A, Vicenzino B. Lateral epicondylalgia. II. Therapeutic management. Phys Ther Rev 1997239–48. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Selvier T, Wilson J. Methods utilized in treating lateral epicondylitis. Phys Ther Rev 20005117–124. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stasinopoulos D, Johnson M I. Physiotherapy and tennis elbow/lateral epicondylitis. Letter. Rapid response to Assendelft et al (2003) article tennis elbow. BMJ 6 Sep 2004

- 15.Smidt N, Assendelft W, Arola H.et al Effectiveness of physiotherapy for lateral epicondylitis: a systematic review. Ann Med 20033551–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stasinopoulos D, Johnson M I. Effectiveness of extracorporeal shock wave therapy for tennis elbow: a review. Br J Sports Med 200539132–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trinh K V, Phillips S D, Ho E.et al Acupuncture for the alleviation of lateral epicondyle pain: a systematic review. Rheumatology 2004431085–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stasinopoulos D, Stasinopoulos I, Johnson M I. Comparison of effects of Cyriax physiotherapy, a supervised exercise programme and polarised polychromatic non‐coherent light (Bioptron light) for the treatment of lateral epicondylitis. Clin Rehabil 2006: in press [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Purdam C R, Johnsson P, Alfredson H.et al A pilot study of the eccentric decline squat in the management of painful chronic patellar tendinopathy. Br J Sports Med 200438395–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stasinopoulos D, Stasinopoulos I. Comparison of effects of exercise programme, pulsed ultrasound and transverse friction in the treatment of chronic patellar tendinopathy. Clin Rehabil 200418347–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alfredson H, Pietila T, Johnson P.et al Heavy‐load eccentric calf muscle training for the treatment of chronic Achilles tendinosis. Am J Sports Med 199826360–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mafi N, Lorentzon R, Alfredson H. Superior short‐term results with eccentric calf muscle training compared to concentric training in a randomized prospective multicenter study on patients with chronic Achilles tendinosis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2001942–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Niesen‐Vertommen S L, Taunton J E, Clement D B.et al The effect of eccentric versus concentric exercise in the management of Achilles tendonitis. Clin J Sports Med 19922109–113. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohberg L, Lorentzon R, Alfredson H. Eccentric training in patients with Achilles tendinosis: normalized tendon structure and decreased thickness at follow up. Br J Sports Medic 2004388–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roos E M, Engstrom M, Lagerquist A.et al Clinical improvement after 6 weeks of eccentric exercises in patients with mid‐portion Achilles tendinopathy: a randomised trial with 1‐year follow‐up. Scand J Med Sci Sports 200414286–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silbernager K G, Thomee R, Thomee P.et al Eccentric overload training with chronic Achilles tendon pain: a randomized controlled study with reliability testing of the evaluation methods. Scand J Med Sci Sports 200111197–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stasinopoulos D, Johnson M I. Treatment/management for tendinopathy. Rapid response to Khan et al (2002) article Time to abandon the ‘tendinitis' myth. BMJ 22 Sep 2004

- 28.Stanish D, Curwin S, Mandell S.Tendinitis: its etiology and treatment. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000

- 29.Stanish D, Rubinovich M, Curwin S. Eccentric exercise in chronic tendinitis. Clin Orthop 198620865–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johannsen F, Gam A, Hauschild B.et al Rebox: an adjunct in physical medicine? Arch Phys Med Rehabil 199374438–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pienimaki T, Tarvainen T, Siira P.et al Progressive strengthening and stretching exercises and ultrasound for chronic lateral epicondylitis. Physiotherapy 199682522–530. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stratford P, Levy D, Gauldie S.et al Extensor carpi radialis tendonitis: a validation of selected outcome measures. Physiotherapy Canada 198739250–255. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rivenburgh D W. Physical modalities in the treatment of tendon injuries. Clin Sports Med 199211645–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cannell L, Taunton J, Clement D.et al A randomized clinical trial of the efficacy of drop squats or leg extension/leg curls to treat clinically diagnosed jumper's knee in athletes: a pilot study. Br J Sports Med 20013560–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jensen K, Di Fabio R. Evaluation of eccentric exercise in treatment of patellar tendinitis. Phys Ther 198969211–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hawary R, Stanish W, Curwin S. Rehabilitation of tendon injuries in sport. Sports Med 199724347–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khan K M, Cook J L, Kannus P.et al Time to abandon the “tendonitis” myth. BMJ 2002324626–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khan K, Cook J, Taunton J.et al Overuse tendinosis, not tendinitis: a new paradigm for a difficult clinical problem. Phys Sportsmed 20002838–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ohberg L, Lorentzon R, Alfredson H. Neovascularisation in Achilles tendons with painful tendinosis but not in normal tendons: an ultrasonographic investigation. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 20019233–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vilarta R, Vidal B D C. Anisotropic and biomechanical properties of tendons modified by exercise and denervation: aggregation and macromolecular order in collagen bundles. Matrix 1989955–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Drechsler W, Knarr J, Mackler L. A comparison of two treatment regimens for lateral epicondylitis: a randomised trial of clinical interventions. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation 19976226–234. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kochar M, Dogra A. Effectiveness of a specific physiotherapy regimen on patients with tennis elbow. Physiotherapy 200288333–341. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smidt N, Windt D, Assendelft W.et al Corticosteroids injections, physiotherapy, or a wait and see policy for lateral epicondylitis: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2002359657–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Struijs P A A, Kerkhoffs G M M J, Assendelft W J J.et al Conservative treatment of lateral epicondylitis: brace versus physical therapy or a combination of both: a randomized clinical study. Am J Sports Med 200432462–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Struijs P A A, Damen P J, Bakker E W P.et al Manipulation of the wrist for the management of lateral epicondylitis: a randomised pilot study. Phys Ther 200383608–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Svernlov B, Adolfsson L. Non‐operative treatment regime including eccentric training for lateral humeral epicondylalgia. Scand J Med Sci Sports 200111328–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Verhaar J, Walenkamp H, Mameren H.et al Local corticosteroid injection versus Cyriax‐type physiotherapy for tennis elbow. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 199678128–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]