Abstract

Objectives

Although walking is a common physical activity, scientifically based training guidelines using standardised tests have not been established. Therefore this explorative study investigated the cardiovascular and metabolic load resulting from different walking intensities derived from maximal velocity (Vmax) during an incremental treadmill walking test.

Methods

Oxygen uptake, heart rate (HR), blood concentrations of lactate and catecholamines, and rating of perceived exertion were recorded in 16 recreational athletes (mean (SD) age 53 (9) years) during three 30 minute walking trials at 70%, 80%, and 90% of Vmax (V70, V80, and V90) attained during an incremental treadmill walking test.

Results

Mean (SD) oxygen uptake was 18.2 (2.3), 22.3 (3.1), and 29.3 (5.0) ml/min/kg at V70, V80, and V90 respectively (p<0.001). V70 led to a mean HR of 110 (9) beats/min (66% HRmax), V80 to 124 (9) beats/min (75% HRmax), and V90 to 152 (13) beats/min (93% HRmax) (p<0.001). Mean (SD) lactate concentrations were 1.1 (0.2), 1.8 (0.6), and 3.9 (2.0) mmol/l at V70, V80, and V90 respectively (p<0.001). There were no significant differences between catecholamine concentrations at the different intensities. Rating of perceived exertion was 10 (2) at V70, 12 (2) at V80, and 15 (2) at V90. Twelve subjects reported muscular complaints during exercise at V90 but not at V70 and V80.

Conclusions

Intensity and heart rate prescriptions for walking training can be derived from an incremental treadmill walking test. The cardiovascular and metabolic reactions observed suggest that V80 is the most efficient workload for training in recreational athletes. Further studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Keywords: walking test, velocity, oxygen uptake, heart rate, lactate

Over the last few decades, walking has been established as one form of endurance training for preventive purposes. Sufficient training effects with little risk of overstrain have been suggested.1,2,3,4 Data on appropriate training intensities for walking vary in the literature, and published test procedures only partly allow training recommendations to be derived. With regard to intensity, many authors refer to maximal heart rate or maximal oxygen uptake.5,6,7 For efficient cardiocirculatory training, the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) recommends 55/65–90% of maximal heart rate (HRmax) or 40/50–85% of maximal oxygen uptake reserve (V̇o2R) or HRmax reserve (HRR).8 However, approaches that use an incremental treadmill walking test (ITWT) as the basis for individual training recommendations are rare.9,10,11

The purpose of this study was to check whether an ITWT is applicable for the derivation of individual training recommendations. A secondary aim was to investigate if walking allows middle aged people to reach sufficient training intensity at comfortable speeds.

Methods

This study was approved by the institution's review board and complies with the Declaration of Helsinki. Each participant gave written informed consent.

Subjects

Sixteen healthy subjects (10 men, six women) took part in the study. Their mean (SD) age was 53 (9) years, height 169 (8) cm, and weight 67 (11) kg. They were familiar with the walking technique and had been participating in recreational sport for an average of 34 months. Mean (SD) Pmax obtained from an incremental cycling test was 2.6 (0.6) W/kg.

Study design

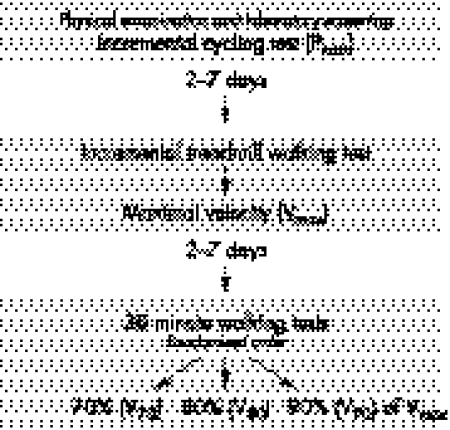

Firstly, all subjects had a clinical and laboratory routine examination and performed an incremental cycling test to rule out any health risks. Two to seven days later an ITWT was conducted followed by three walking tests at constant velocities: 70%, 80%, and 90% of the maximal velocity (Vmax) obtained during the ITWT. Figure 1 shows the course of the study. The test period ranged between two and four weeks for each subject. The participants were told to neither change their normal training load during the study nor perform intensive or prolonged physical exercise on the day before the tests.

Figure 1 Overview of the study design.

ITWT

One ITWT was performed for training purposes two to seven days before the second ITWT which served as the basis for the later tests of constant velocity. Starting at 4.3 km/h, the velocity was increased by 0.7 km/h every three minutes until exhaustion or Vmax was reached with the appropriate walking technique (no race walking or running). The test was carried out without treadmill inclination to simulate as close as possible walking in the field. After two to seven days, a second identical ITWT was performed. During these tests, HR was measured and recorded continuously with a portable device (Accurex‐Plus; Polar, Kempele, Finland). For the determination of the blood lactate concentration (Super GL; Greiner, Flacht, Germany), capillary blood was taken from the hyperaemised earlobe at rest and after each stage during a break of about 20 seconds. From the lactate curve, the individual anaerobic threshold (IAT) was determined by the method of Hagberg and Coyle,12 which was evaluated with race walkers. For the radioenzymatic determination of catecholamines13 before and immediately after exercise, 300 μl arterialised capillary blood was taken from the hyperaemized earlobe. In addition, gas exchange parameters (Meta‐Max; Cortex, Leipzig, Germany) were continuously measured, and the rating of perceived exertion (RPE) recorded.14

With reference to Vmax, individual intensities for three constant velocity exercises were determined (70%, 80%, and 90% of Vmax = V70, V80, and V90).

Walking endurance exercises

The subjects walked at the three intensities (V70, V80, and V90) on the same treadmill for 30 minutes in random order. Before the 30 minute exercise, each subject walked for three minutes at V70 to warm up. During the exercise and for three minutes after it had finished, HR and oxygen uptake (V̇o2) were continuously measured. With reference to V̇o2 and respiratory exchange ratio, energy output was calculated; 3.5 ml/min/kg was considered to be 1 MET. Capillary samples for determination of lactate and catecholamine as well as the recording of RPE were carried out after 10 and 20 minutes of exercise during a 30 second break. Technical abnormalities and physical complaints were only recorded; no quantification was performed.

Statistical analysis

After normal distribution of data had been confirmed with the Kolmogoroff‐Smirnov test, descriptive statistical analysis was performed; mean (SD) values were calculated. In the case of normally distributed data, a two factorial (intensity and time) analysis of variance was performed. The Scheffé test was used for post hoc comparisons. For ordinally scaled values (RPE), calculations were performed by non‐parametric procedures (rank correlation according to Spearman). The significance level for the α error was set at p<0.05.

Results

ITWT

During the ITWT, the subjects reached a mean (SD) Vmax of 8.3 (0.6) km/h, and a mean (SD) V̇o2max of 33.2 (5.1) ml/min/kg. Table 1 gives the ITWT results.

Table 1 Results from the incremental treadmill walking test.

| Variable | Max | IAT |

|---|---|---|

| Velocity (km/h) | 8.3 (0.6) | 6.9 (0.6) (83% Vmax) |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 166 (14) | 131 (14) |

| Lactate (mmol/l) | 6.1 (1.8) | 2.0 (0.3) |

| V̇o2max (ml/min/kg) | 33.2 (5.1) | 23.4 (4.8) |

| Energy cost (kJ/min) | 46.7 (7.1) | 32.9 (6.8) |

| MET | 9.5 (1.5) | 6.7 (1.4) |

Values are maximal performance (Max) and individual anaerobic threshold (IAT) during walking and are expressed as mean (SD) (n = 16).

Walking trials

Oxygen uptake

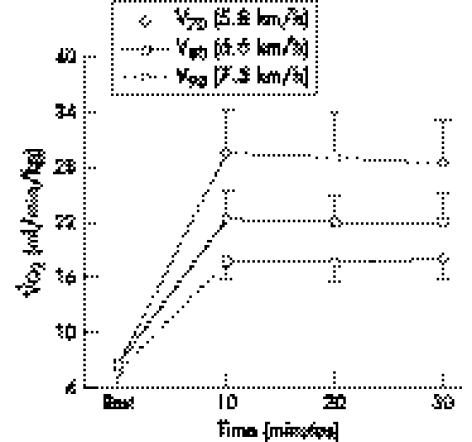

The subjects reached a V̇o2 of 18.2 (2.3) ml/min/kg (55% V̇o2max) at V70, 22.3 (3.1) ml/min/kg at V80 (67% V̇o2max), and 29.3 (5.0) ml/min/kg at V90 (88% V̇o2max). There was a significant effect of intensity on V̇o2. Figure 2 gives the results from post hoc testing. At V80, V90, and VIAT all subjects were above 60% V̇o2max.

Figure 2 Oxygen uptake (V̇o2) during the 30 minute walking trials at 70%, 80%, and 90% of the maximal velocity obtained in the incremental treadmill walking test (V70, V80, and V90). Values are mean (SD) (n = 16). All three values at each time point are significantly different from each other (p<0.001).

HR

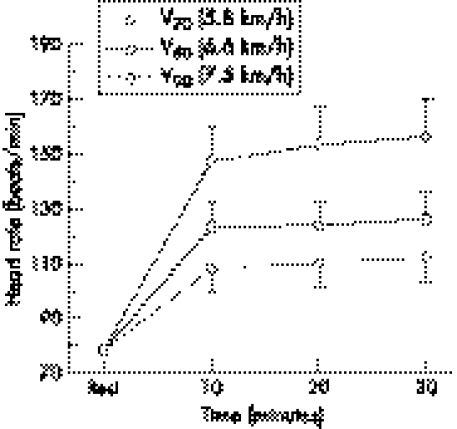

Mean HR reached 110 (9) beats/min during V70 (66% HRmax), 124 (9) beats/min during V80 (75% HRmax), and 152 (13) beats/min during V90 (93% HRmax) (fig 3). During V80 and V90 all subjects were above 65% HRmax. HR during the 80% endurance exercise was significantly (p<0.05) lower than HR at IAT (131 (14) beats/min, 79% HRmax). There was a significant effect of intensity on HR. Figure 3 shows different results from post hoc testing.

Figure 3 Heart rate during the 30 minute walking trials at 70%, 80%, and 90% of the maximal velocity obtained in the incremental treadmill walking test (V70, V80, and V90). Values are mean (SD) (n = 16). All three values at each time point are significantly different from each other (p<0.001).

Lactate concentration

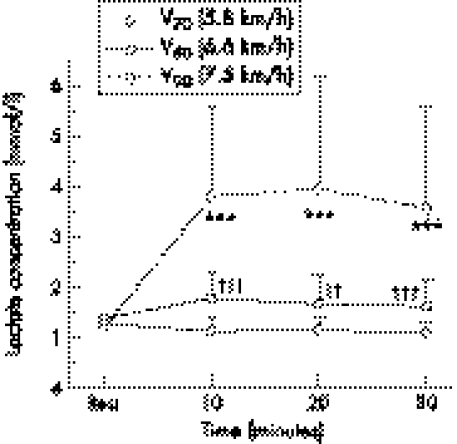

During the 30 minute walking tests, mean lactate concentration reached 1.1 (0.2), 1.8 (0.6), and 3.9 (2.0) mmol/l at V70, V80, and V90 respectively. There was a significant effect of intensity on lactate between V70 and V80 as well as between V80 and V90 (fig 4).

Figure 4 Lactate concentration during the 30 minute walking trials at 70%, 80%, and 90% of the maximal velocity obtained in the incremental treadmill walking test (V70, V80, and V90). Values are mean (SD) (n = 16). ***Significantly different from V80 and V70 (p<0.001), ††,††† significantly different from V70 (p<0.01, p<0.001 respectively).

Energy consumption

The total energy consumption during the 30 minute walking tests was 744 (93) kJ (177 (22) kcal or 5.2 (0.7) MET) at V70, 930 (129) kJ (221 (31) kcal or 6.3 (2.5) MET) at V80, and 1224 (207) kJ (291 (49) kcal or 8.4 (1.4) MET) at V90. There was a significant effect of intensity (p<0.001).

Catecholamine concentration

The catecholamine concentrations did not differ significantly between the three intensity levels. After 30 minutes of walking, the mean maximal free noradrenaline concentrations were 6.48 (2.17), 5.47 (1.34), and 6.26 (1.76) nmol/l at V70, V80, and V90 respectively. The corresponding adrenaline concentrations were 1.17 (0.28), 1.00 (0.27), and 1.10 (0.31) nmol/l.

RPE

A mean RPE of 10 (2) (“very easy” to “quite easy”), 12 (2) (“quite easy” to “a little difficult”), and 15 (2) (“difficult”) was recorded at V70, V80, and V90 respectively. There was a significant effect of intensity on RPE (p<0.001). An RPE of 19 (“very, very difficult”) was reported by one subject during V90. At the end of the endurance test, 12 subjects felt that walking at V80 was more comfortable than at V70 or V90.

Complaints

At V90, 12 out of 16 subjects reported physical problems mainly in the lower legs. During V70 and V80, no problems were reported by the subjects.

Discussion

It has been shown that V̇o2 during V70 corresponds to the minimum intensity (55% V̇o2max) for training as recommended by ACSM, whereas V90 approaches the upper limit (88% V̇o2max).8 Thus, low intensity walking at V70 may lead to health benefits when it is performed frequently and for long enough.15 However, V80 (67% of V̇o2max) may be more appropriate for efficient endurance training. All subjects were above 60% V̇o2max or 50% V̇o2R during V80. In contrast, V90 seems quite often to induce muscle pain in the lower legs even after only 30 minutes.

The mean maximal HR reached 220 minus age, indicating sufficient maximal effort on a treadmill.16 If the mean HR response of the three walking endurance exercises is considered, at V70 the subjects are at the minimum HR, and at V80 and V90 they are within the recommended HR range. At V80 and V90, all subjects are above the minimum HR described by ACSM.8

The mean lactate concentration during V70 was similar to resting concentrations, suggesting that the exercise intensity is low. During V90 the mean lactate concentration indicates intense physical performance. The mean lactate concentration during V80 was close to the IAT and within the range of extensive endurance training and17 and thus compatible with appropriate recreational intensity.

According to Morris and Hardman,3 in people with a body weight of about 70 kg, the energy consumption during walking on even ground at a velocity of 6.4–8.0 km/h corresponds to 25–36 kJ/min. In 40–56 year old men, Pollock et al7 measured an energy consumption of 28.3–36.5 kJ/min for a velocity range of 6.8–7.6 km/h. The results of our study (5.8–7.5 km/h and 25–40 kJ/min) correspond well to these results.

The catecholamine concentrations did not differ significantly between intensities. Therefore this variable may not be suitable for defining efficient walking intensities. If the observed concentrations of noradrenaline and adrenaline are compared with those from earlier studies for cardiac patients during a strength endurance circuit and badminton training, they fall in the same range.18,19

Another variable that suggests that V80 is an adequate exercise intensity is the mean RPE (12 (2)). Dishman20 recommends the same RPE for endurance training with appropriate intensity. Spelman et al21 recommended an RPE of “quite easy” (Borg scale 11) for walking training with 50% of V̇o2max. Also, the 70% walking endurance performance was subjectively perceived as too low (“very easy”) and V90 was too intense and described as “very difficult”.

What is already known on this topic

Data on appropriate training intensities for walking vary in the literature, and published test procedures only partly allow training recommendations to be derived

Approaches using an incremental treadmill walking test (ITWT) as the basis for individual training recommendations are rare

What this study adds

An ITWT is applicable for deriving individual intensity recommendations for walking training

The most promising intensity is 80% of the maximal velocity reached during ITWT

Furthermore, orthopaedic problems occurred during the highest exercise intensity, mainly with pretibial muscles, as in earlier studies with recreational athletes.22,23 Although symptoms in most cases disappeared quickly after exercise, straining beyond the pain limit should be avoided, as irreversible damage such as neurological disorders and muscle necroses has been described.24,25

In conclusion, an ITWT is appropriate for deriving individual intensity recommendations for walking training. The most promising intensity is 80% of the maximal velocity reached during ITWT.

Abbreviations

HR - heart rate

IAT - individual anaerobic threshold

ITWT - incremental treadmill walking test

RPE - rating of perceived exertion

V̇o2 - oxygen uptake

Footnotes

Competing interests: none declared

References

- 1.Duncan J J, Gordon N F, Scott C B. Women walking for health and fitness. How much is enough? JAMA 19912663295–3299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manson J E, Greenland P, LaCroix A Z.et al Walking compared with vigorous exercise for the prevention of cardiovascular events in woman. N Engl J Med 2002347716–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morris J M, Hardman A E. Walking to health. Sports Med 199723306–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rippe J M, Ward A, Porcari D D.et al Walking for health and fitness. JAMA 19882592720–2724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jetté M, Sidney K, Campbell J. Effects of a twelve‐week walking program on maximal and sub maximal work output indices in sedentary middle‐aged men and women. J Sport Med 19882859–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kline G M, Porcari J P, Hintermeister R.et al Estimation of VO2max from a one‐mile track walk, gender, age, and body weight. Med Sci Sports Exerc 198719253–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pollock M, Caroll J, Graves J.et al Injuries and adherence to walk/ jog and resistance training programs in the elderly. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1991231194–1200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American College of Sports Medicine The recommended quantity and quality for exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness, and flexibility in healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc 199830975–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oja P, Laukkanen R, Pasanen M.et al A 2‐km walking test for assessing cardiorespiratory fitness in healthy adults. Int J Sports Med 199112356–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Porcari J P, Ebbeling C B, Ward A.et al Walking for exercise testing and training. Sports Med 19898189–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santiago M, Alexander J, Stull G.et al Physiological responses of sedentary women to a 20‐week conditioning program of walking or jogging. Scand J Sports Sci 1987933–39. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hagberg J M, Coyle E F. Physiological determinants of endurance performance as studied in competitive race walkers. Med Sci Sports Exerc 198315287–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Da Prada M, Zürcher G. Simultaneous radio enzymatic determination of plasma and tissue adrenaline, noradrenalin and dopamine within the femtomole range. Life Science 1976191161–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borg G. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med Sci Sports Exerc 198214377–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blair S N, Kohl H W, Paffenbarger R S.et al Physical fitness and all‐cause mortality: a prospective study of healthy men and woman. JAMA 19892622395–2401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kindermann W. Recommendations for ergometry in medical practice. Dtsch Z Sportmed 198738244–268. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Urhausen A, Coen B, Weiler B.et al Individual anaerobic threshold and maximum lactate steady state. Int J Sports Med 199312134–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwarz M, Urhausen A, Leukens S.et al Cardio circulatory and metabolic strain in patients with coronary heart disease during Badminton as part of their ambulatory kinetotherapy. Int J Sports Med 199617(suppl 1)P8 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Urhausen A, Schwarz M, Stefan S.et al Cardiovascular and metabolic strain during a strength‐endurance circle training in out‐patient cardiac rehabilitation. Dtsch Z Sportmed 200051130–136. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dishman R K. Prescribing exercise intensity for healthy adults using perceived exertion. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1994291087–1094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spelman C C, Russel R, Pate C A.et al Self‐selected exercise intensity of habitual walkers. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1993251174–1179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwarz M, Schwarz L, Urhausen A.et al Standards of sportsmedicine: walking. Dtsch Z Sportmed 200253292–293. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwarz M, Schwarz L, Urhausen A.et al Characteristic strain of walking as compared to jogging and cycle ergometry in persons with different aerobic performance capacity. Dtsch Z Sportmed 200152136–141. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lennart S, Forsberg A, Westlin N. Anterior tibial compartment pressure during race walking. Am J Sports Med 19862136–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Logan J G, Rorabaeck Ch, Castle G S. The measurement of dynamic compartment pressure during exercise. Am J Med 198311220–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]