Abstract

Background

Achilles tendinopathy is a common condition, which can become chronic and interfere with athletic performance. The proteinase inhibitor aprotinin (as injection) has been found to improve recovery in patellar tendinopathy1 (evidence level 1b2) and Achilles tendinopathy.3 Internationally this therapy is being used based on this limited knowledge base.

Aim

To evaluate whether aprotinin injections decrease time to recovery in Achilles tendinopathy.

Method

A prospective, randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial was performed comparing saline (0.9%) plus local anaesthetic injections and eccentric exercises with aprotinin (30 000 kIU) plus local anaesthetic injection and eccentric exercise. Three injections were given, each a week apart. In total, 26 patients, with 33 affected tendons, were enrolled for this study.

Results

At no follow up point (2, 4, 12, or 52 weeks) was there any statistically significant difference between the treatment group and placebo. This included VISA‐A scores4 and secondary outcome measures. However, a trend for improvement over placebo was noted.

Conclusion

In this study on Achilles tendinopathy, aprotinin was not shown to offer any statistically significant benefit over placebo. Larger multicentre trials are needed to evaluate the efficacy of aprotinin in Achilles tendinopathy.

Keywords: Achilles, tendinopathy

Achilles tendinopathy is a common condition in the running athlete, accounting for 15–18% of running injuries.5 With 10% of the American adult population involved in running activities, Achilles tendinopathy is therefore a common presentation in sports medicine,6 and is difficult to manage successfully, with a high rate of failure with conservative management.7 The duration of symptoms is often >12 months.8

The evidence base for management of Achilles tendinopathy is not comprehensive,9 although trials in recent years have shown that some treatments are effective. Patients undertaking an eccentric exercise programme, show an 82% return to their previous level of activity in 3 months (level 1b2).10 Topical nitrates reduce pain levels at 6 months compared with placebo, and 78% of patients are asymptomatic with activities of daily living at 6 months (level 1b2).11 Polidocanol injections to the neo‐vessels show reduced pain levels with activity if the vessels have been sclerosed (level 1b2).12,13 There is no good evidence supporting the use of piroxicam14 and corticosteroid injections.15 In animal models corticosteroid injection in and around the Achilles tendon leads to a decreased failure stress.16

Heel pads are also ineffective (level 1b2).17 We found no controlled studies up to September 2005 on a PubMed search for stretching and Achilles tendinopathy. Orthotic use in Achilles tendinopathy does not have any conclusive benefit (level 1b2).18,19,20

Tallon et al21 have reviewed papers on the success rates of surgery for Achilles tendinopathy. Most papers quote a success rate of >70% (level 2a2). Ohberg et al22 showed that 50% returned to a high level of sport (level 42) and Paavola et al23 showed that 67% returned to sport at the same level (level 42). Ultrasound guided percutaneous tenotomy showed that 75% had returned to their sport at their desired level (level 42)24 and the technique may offer a reduced complication rate with similar success rates to open surgery.

Aprotinin is a natural serine proteinase inhibitor obtained from bovine lung,25 which may therefore act in tendinopathy as a collagenase inhibitor. In a double blind, placebo controlled trial on patellar tendons, aprotinin injections showed significant improvements over corticosteroid injections and saline injections at 12 months.1 A number of uncontrolled or poorly controlled studies have shown high rates of success in treating Achilles tendinopathy with peritendinous aprotinin injections.3,26,27,28 In one semirandomised study there was a prompt resumption of sports by 78% of patients who received aprotinin compared with 30% who received placebo. The regimen was between four and six injections.3 In uncontrolled studies, the success rate of aprotinin treatment has been approximately 80%,26,27 although 2.6–11% of patients have suffered allergic reactions to the drug (which has been the only consistent side effect reported and usually upon re‐exposure).26,28

METHODS

Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the ethics committee of the University of New South Wales. Patients were enrolled through private practice (RB and JO). Eligible patients were those with >6 weeks of mid‐substance Achilles tendinopathy, without any of the following exclusion criteria: (a) acute condition, bursitis, previous surgery, or enthesopathy; (b) allergy to aprotinin; (c) pregnancy or lactation; (d) anti‐coagulant therapy; (e) significant cardiovascular, renal, or hepatic disease; (f) age <17 years old; and (g) inability to fulfill the follow up criteria.

The diagnosis of Achilles tendinopathy was made on clinical grounds. The history included Achilles pain that was activity related and of gradual onset. Physical examination revealed non‐insertional tenderness of the Achilles tendon that corresponded to the site of pain. If there was a nodule present, it would elevate with plantarflexion of the ankle, indicating no paratendonitis.

Eligible patients could choose to either enter into the study (the benefit of which was free treatment and follow up) or be treated as a private patient with the active agent. In order not to discourage patients from choosing to be part of the study, they were permitted to use other non‐surgical treatments as they wished, such as nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs and orthotics.

Patients were randomised to receive either an exercise programme and placebo injection, or an exercise programme and aprotinin injection. Patients and examiners were blinded to their allocation. Allocation of patients was organised by AH, using random number selection.

Three injections were given in total, one per week, by RB or JO. The active injections consisted of 3 ml (30 000 kIU) of aprotinin and 1 ml xylocaine 1% plain. The placebo injection consisted of 3 ml of normal saline and 1 ml of xylocaine 1% plain. The solutions were both clear to direct vision. The injections were placed peritendinously.

The exercise programme was based on eccentric loading as described by Alfredson et al 1998.29 Patients were instructed by RB or JO on their exercises and received a handout. Eccentric exercise compliance was checked at the review appointments.

RB or JO evaluated patients at 2 weeks, 3 months, and 12 months. At 1 month, patients were evaluated using the Victoria Institute of Sport Assessment‐Achilles (VISA‐A) questionnaire only, via e‐mail. The evaluating authors were blinded to the treatment group. The VISA‐A rating scale4 was the primary outcome measure to evaluate the results of treatment. At each visit an assessment of tenderness (0–10 pain scale), number of hops to pain, number of single leg heel raises to pain, return to previous level of sport, and patient rating (0 (unusable tendon) to 10 (completely pain free tendon)) was performed. Side effects arising from the injections or the exercise programme were recorded.

Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. One way analysis of variance was performed for statistical significance on the primary outcome factor, the VISA‐A score. The Mann‐Whitney U test was performed for statistical significance on the following outcome factors: hops to pain, heel raises to pain, tenderness, patient rating, postinjection pain, and postinjection itch. Fisher's exact test was performed for statistical significance on the outcome factor of return to sport.

RESULTS

Between March 2003 and April 2004, 26 patients with 33 affected tendons were enrolled (17 men and nine women; mean age 46 years (range 30–73); mean weight 83 kg (range 54–13); mean height 1.75 m (range 1.57–1.91 m); mean duration of symptoms 10 months (range 1.5–36)). There were 18 left tendons and 15 right tendons, of which 17 tendons were noted to have a nodule.

The groups were similar for weight, height, age, hours of training per week, and duration of symptoms (table 1). In the aprotinin group, 33% of the tendons were in women, compared with 39% in the placebo group. In the aprotinin group, 73% of the tendons were injured in high intensity sports (such as running, football, or tennis) compared with 66% in the placebo group.

Table 1 Patient characteristics.

| Placebo | Aprotinin | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | 81.5 | 84.3 | 0.655 | |||

| Height (m) | 1.75 | 1.75 | 0.853 | |||

| Age (years) | 46.3 | 44.9 | 0.981 | |||

| Hours training (/week) | 7.2 | 7.3 | 0.714 | |||

| Duration symptoms (months) | 10.9 | 8.1 | 0.353 | |||

| VISA‐A (/100) | 62.2 | 59.1 | 0.507 |

There were 18 tendons randomised to the placebo group and 15 tendons to the aprotinin group. Seven tendons were lost or excluded during the study period. One patient (one tendon) was non‐compliant with the exercise programme, two patients (three tendons) were dissatisfied with the results, one patient (one tendon) suffered a broken leg, one patient (one tendon) was placed in an orthopaedic walking boot by another practitioner, and one patient (one tendon) had moved away. The two patients who were dissatisfied with the results dropped out of the study after the third injection (two tendons: one placebo, one aprotinin) and after the 3 month follow up (one tendon: placebo), respectively.

There were 18 placebo and 15 aprotinin tendons available for follow up at 2 weeks; 16 placebo and 14 aprotinin tendons at 1 month; 16 placebo and 13 aprotinin tendons at 3 months; and 13 placebo and 13 aprotinin tendons at 12 months.

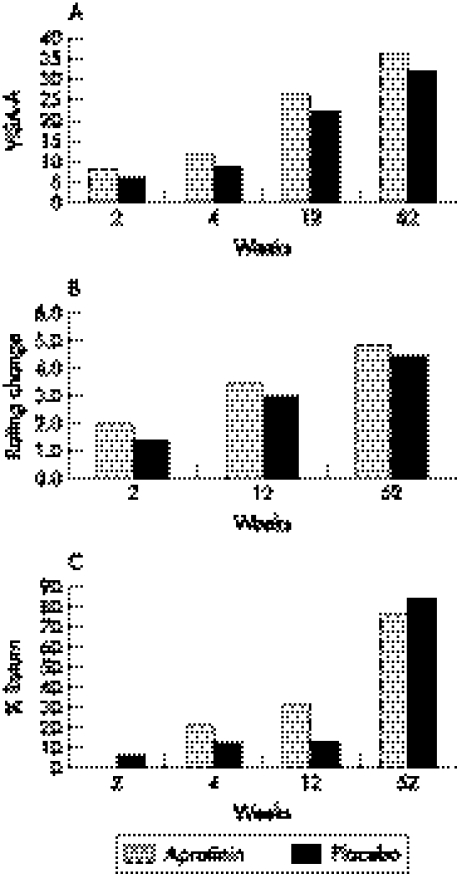

Absolute improvements in VISA‐A scores were greater in the aprotinin group than the placebo group at all reviews (table 2; fig 1A) but the differences between groups were not statistically significant: 2 weeks p<0.627, 4 weeks p<0.648, 12 weeks p<0.733 and 52 weeks p<0.946.

Table 2 Amount of change on average from the initial rating or score.

| VISA‐ A | Tender‐ ness | Patient rating | Return to sport | Hops | Heel raise | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aprotinin | ||||||||||||

| 2 week | 8.5 | −1.0 | 2.0 | 0% | 1.5 | 0.7 | ||||||

| 4 week | 11.8 | 2.5 | 21% | |||||||||

| 12 week | 26.3 | −1.7 | 3.5 | 31% | 5.6 | 2.8 | ||||||

| 52 week | 36.3 | −4.4 | 4.9 | 77% | 7.4 | 4.3 | ||||||

| Placebo | ||||||||||||

| 2 week | 6.1 | −0.9 | 1.4 | 6% | 0.6 | 0.7 | ||||||

| 4 week | 9.0 | 1.0 | 13% | |||||||||

| 12 week | 22.1 | −3.0 | 3.0 | 13% | 4.1 | 2.6 | ||||||

| 52 week | 32.3 | −4.1 | 4.4 | 85% | 5.5 | 3.1 |

Return to sport is a percentage of tendons at full activity.

Figure 1 (A) VISA‐A change; (B) patient rating: improvement; (C) return to full activities.

The secondary outcome measures did not reveal any statistically significant differences between groups. The strongest trends towards better results with aprotinin were number of hops to pain at 2 weeks (p<0.221), change in patient rating at 2 weeks (p<0.290) (fig 1B), and return to sport at 12 weeks (p<0.364) (fig 1C). The placebo group generally did not have superior outcomes under most secondary outcome measures, although there was a trend towards greater reduction in tenderness at 12 weeks (p<0.190).

There was a trend towards a greater number of injections producing an itch in the aprotinin group (p<0.07) (table 3). There was no statistical difference in the number of painful injections between each group (p<0.330) (table 3). No allergic reactions were noted in either injection group. Only one patient noted headache, after two of the three injections. This patient received bilateral injections (one aprotinin injection and one placebo injection). No infections, ruptures, or other side effects were encountered.

Table 3 Number of injections causing pain or itch.

| Treatment | Pain | Itch | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aprotinin | 3 | 18 | ||

| Placebo | 9 | 4 |

DISCUSSION

We believe that this is the only double blind, randomised, placebo controlled trial evaluating aprotinin in Achilles tendinopathy. We compared aprotinin and exercises with placebo and exercises in order to see if aprotinin offered a benefit in both the short and long term. We used the VISA‐A scale as a functional grade of severity as the primary outcome measure.

Our results do not indicate any statistically significant improvement in the aprotinin group over placebo at any follow up visit for either the primary or secondary outcome measures. Despite this, there was a consistent trend towards improvement in the aprotinin group as measured by the VISA‐A and secondary outcome measures.

The lack of statistical significance may be due to the small sample size. In order to detect a difference in VISA‐A score of 60–70, with standard deviation of 13, power of 80%, and a significance level of 5%, approximately 28 patients per group would be required. It was difficult to recruit patients to this study involving a placebo injection, because all patients were given the choice between active treatment or enrolment in the study, and the majority chose active treatment.

Our results at 3 months are not as good as previous studies for eccentric exercises.10,29Only 13% of the placebo group and 31% of the aprotinin group had returned to their previous level of sport. It is not apparent whether the low levels of return to sport at 3 months compared with the previous studies were due to chance, different methods of subject recruitment, negative effects of using injections, or poorer compliance with eccentric training because an injection was used. However, at 12 months, the overall results were markedly better, as 85% in the placebo and 77% in the aprotinin group had returned to their previous levels of sport.

Four patients with bilateral tendon involvement received placebo on one side and aprotinin on the other. One patient did very well, with both tendons scoring 100 on the VISA‐A 100 at 12 months. One patient was similar at all follow up points, except at 12 months, with VISA‐A of 87 for the aprotinin treated tendon and 76.5 for the placebo treated tendon. This patient did not elect to have the aprotinin injection following the study. One patient was similar at all follow up points except 12 months, when VISA‐A was 100 for the aprotinin treated tendon and 81 for the placebo treated tendon. This patient elected to have an aprotinin injection following the study period due to dissatisfaction with the placebo treated tendon. One patient did poorly with both tendons and withdrew from the study after the third injection. These observations of randomly allocated tendons within the same patient suggest a trend towards better results with aprotinin than placebo.

Of the two patients (three tendons) that withdrew from the study because of dissatisfaction, two tendons were treated with placebo and one with aprotinin. One patient with a placebo allocated tendon elected to have the aprotinin following withdrawal from the study, and returned to full activities after the crossover aprotinin injection.

The dosing regimen used was 30 000 IU in three injections spaced 1 week apart. The literature shows a range of doses (20 000–62 500 IU),1,3,26,28 and there seems to be no standard number of injections. The doses used in this study were the same as we had previously used successfully in private practice.28 It may be that the lack of statistical significance was due to an insufficient aprotinin dose.

We note that a significant problem with aprotinin is the risk of allergic reaction. Aprotinin is derived from bovine lung and possesses antigenic properties in humans.30 Hypersensitivity and anaphylaxis are <0.1% with no prior exposure and 2.7% with re‐exposure.25 Anaphylaxis upon re‐exposure in cardiac patients was confirmed in 2.5% of patient's.31 In the two previous studies with aprotinin and in our study there were no anaphylactic reactions.1,3 Orchard et al reviewed 422 injections, and showed a systemic allergy rate of 2.6% upon re‐exposure.28 The described regimen of aprotinin therapy in the literature is three injections spaced 1–2 weeks apart.1,3 The risks of systemic allergic reaction on re‐exposure may mean that a preferable regimen is to space the injections further apart.25 In our study, no patient had any clinically significant allergic reaction, nor was there any infection or tendon rupture during the study period. No statistically significant difference for postinjection itch or for injection pain was shown.

What is already known on this topic?

Aprotinin is a well documented collagenase inhibitor

Previously there have been two randomised trials using aprotinin, one on patellar tendinopathy showing a significant improvement over placebo and one semi‐randomised trial on Achilles tendinopathy showing a significant improvement over placebo

What this study adds

Using a functional grade of severity and a functional outcome measure in a double blind placebo controlled trial we failed to confirm the benefit of aprotinin in tendinopathy

The typical histopathological changes of tendinopathy include degenerated and disordered collagen, hypercellularity, vascular ingrowth and an increase in ground substance.8 The exact pathogenesis of these changes and the source of the pain are still not well understood.

A proposed mechanism for tendinopathy is a change in the balance between matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases (TIMP).32,33,34 MMPs and TIMP are responsible for tissue remodelling.34 Recent studies suggest that there are alterations in these levels in diseased tendons.32,33,34,35 Specifically, MMPs may increase and TIMP decrease, leading to excess collagen degradation33,35 and thus tendinopathy.

MMPs are endopeptidases that cleave constituents of the extracellular matrix.30 Specifically, MMP‐1 cleaves collagen type 130 the main collagen found in tendons. In a study comparing diseased and control patellar tendons, the diseased tendons showed an increased expression of MMP‐1 and a decreased expression of TIMP.35 It is still not clear whether increased expression of MMPs is responsible for causing tendinopathy.

Aprotinin has level 1b evidence as a treatment for patellar tendinopathy.1 There is also level 2b and level 3b evidence for aprotinin in Achilles tendinopathy.3,26 The histological appearance of patellar and Achilles tendinopathies is indistinguishable.36 We propose that a larger trial would be required to adequately assess the efficacy for aprotinin in achilles tendinopathy.

CONCLUSION

In this study, aprotinin did not show any statistically significant benefit over placebo. There was a trend to improved results across primary and secondary outcome measures, which included an earlier return to sport rate. There is previous level 1b evidence for its efficacy in patellar tendinopathy and we propose a larger trial to increase power. The optimal dosing regimen is yet to be established, because of the risk of anaphylactic reaction in the weeks following re‐exposure. It may be preferable in the future to test a single dose regimen or have multiple doses spread over many months.

Abbreviations

VISA‐A - Victoria Institute of Sport Assessment‐Achilles

MMP - matrix metalloproteinase

TIMP - tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases

Footnotes

Competing interests: none

References

- 1.Capasso G, Testa V, Maffulli N.et al Aprotinin, corticosteroids and normosaline in the management of patellar tendinopathy in athletes: a prospective randomised study. Sports Exer Inj 19973111–115. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Phillips B, Ball C, Sackett D.et alLevels of evidence. Oxford: Oxford Centre for Evidence‐based Medicine, 2001

- 3.Capasso G, Maffulli N, Testa V.et al Preliminary results with peritendinous protease inhibitor injections in the management of Achilles tendinitis. J Sports Traumatol Rel Res 19931537–43. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robinson J, Cook J, Purdam C.et al The VISA‐A Questionnaire: A valid and reliable index to the clinical severity of Achilles tendinopathy. Br J Sports Med 200135335–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brunet M, Cook S, Brinker M.et al A survey of running injuries in1505 competitive and recreational runners. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 199030307–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schepsis A, Jones H, Haas A. Achilles tendon disorders in athletes. Am J Sport Med 200230287–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paavola M, Kannus P, Paakkala T.et al Long term prognosis of patients with Achilles tendinopathy. An observational 8‐year follow‐up study. Am J Sport Med 200028634–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Astrom M, Rausing A. Chronic Achilles tendinopathy. A survey of surgical and histopathological findings. Clin Orth Rel Res 1995316151–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McLauchlan G, Handoll H. Interventions for treating acute and chronic Achilles tendinitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 200511–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mafi N, Lorentzon R, Alfredson H. Superior short term results with eccentric calf muscle training compared to concentric training in a randomized prospective multicenter study on patients with chronic Achilles tendinosis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2001942–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paoloni J, Appleyard R, Nelson J.et al Topical glyceryl trinitrate treatment of chronic noninsertional achilles tendinopathy. J Bone Joint Surg 200486A916–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohberg L, Alfredson H. Ultrasound guided sclerosis of neovessels in painful chronic Achilles tendinosis: pilot study of a new treatment. Br J Sports Med 200236173–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alfredson H, Ohberg L. Sclerosing injections to areas of neo‐vascularisation reduce pain in chronic Achilles tendinopathy: a double‐blind randomised controlled trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 200513338–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Astrom M, Westlin N. No effect of piroxicam on achilles tendinopathy. Acta Orthop Scand 199263631–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shrier I, Matheson G, Kohl H. Achilles tendonitis: are corticosteroid injections useful or harmful? Clin J Sport Med 19966245–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hugate R, Pennypacker J, Saunders M.et al The effects of intratendinous and retrocalcaneal intrabursal injections of corticosteroid on the biomechanical properties of rabbit Achilles tendons. J Bone Joint Surg 200486A794–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lowdon A, Bader D, Mowat A. The effect of heel pads on the treatment of Achilles tendinitis: A double blind trial. Am J Sport Med 198412431–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Larsen K, Weidich F, Leboeuf‐Yde C. Can custom‐made biomechanic shoe orthoses prevent problems in the back and lower extremities? A randomized, controlled intervention trial of 146 military conscripts. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 200225326–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D'Ambrosia R. Orthotic devices in running injuries. Clin Sports Med 19854611–618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Subotnick S, Sisney P. Treatment of Achilles tendinopathy in the athlete. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 198676552–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tallon C, Coleman B, Khan K.et al Outcomes of surgery for chronic Achilles tendinopathy. A critical review. Am J Sport Med 200129315–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohberg L, Lorentzon R, Alfredson H. Good clinical results but persisting side‐to‐side differences in calf muscle strength after surgical treatment of chronic Achilles tendinosis. A 5 year follow‐up. Scand J Med Sci Sports 200111207–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paavola M, Kannus P, Orava S.et al Surgical treatment for chronic Achilles tendinopathy: a prospective seven month follow up study. Br J Sports Med 200236178–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Testa V, Capasso G, Benazzo F.et al Management of Achilles tendinopathy by ultrasound‐guided percutaneous tenotomy. Med Sci Sports Exerc 200234573–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals Trasylol® (aprotinin injection). www.trasylol.com

- 26.Aubin F, Javaudin L, Rochcongar P. Case reports of aprotinin in Achilles tendinopathies with athletes. J Pharmacie Clinique 199716270–273. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rochongar P, Thoribe B, Le Beux P.et al Peritendinous aprotinin injections in the management of achilles tendinosis in sports medicine. Sci Sports 2005. (in press)

- 28.Orchard J, Hofman J, Brown R. The risks of local aprotinin injections for treatment of chronic tendinopathy. Sports Health 20052324–28. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alfredson H, Pietila T, Jonsson P.et al Heavy load eccentric calf muscle training for the treatment of chronic Achilles tendinosis. Am J Sports Med 199826360–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Birkedal‐Hansen H, Moore W, Bodden M.et al Matrix metalloproteinse: a review. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 19934197–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dietrich W, Spath P, Zuhlsdorf M.et al Anaphylactic reactions to aprotinin reexposure in cardiac surgery. Anesthesiology 20019564–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dalton S, Cawston T, Riley G.et al Human shoulder tendon biopsy samples in organ culture produce procollagenase and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases. Ann Rheum Dis 199554571–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ireland D, Harrall R, Curry V.et al Multiple changes in gene expression in chronic human Achilles tendinopathy. Matrix Biol 200120159–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lo I, Marchuck L, Hollinshead R.et al Matrix metalloproteinase and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase MRNA levels are specifically aletred in torn rotator cuff tendons. Am J Sports Med 2004321223–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fu S, Chan B, Wang W.et al Increased expression of matrix metalloproteinase 1 (MMP‐1) in 11 patients with patellar tendinosis. Acta Orthop Scand 200273658–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maffulli N, Testa V, Capasso G.et al Similar histopathological picture in males with achilles and patellar tendinopathy. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2004361470–1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]