Abstract

Despite having remarkably similar three-dimensional structures and stabilities, IL-1β promotes signaling, whereas IL-1Ra inhibits it. Their energy landscapes are similar and have coevolved to facilitate competitive binding to the IL-1 receptor. Nevertheless, we find that IL-1Ra folds faster than IL-1β. A structural alignment of the proteins shows differences mainly in two loops, a β-bulge of IL-1β and a loop in IL-1Ra that interacts with residue K145 and connects β-strands 11 and 12. Bioassays indicate that inserting the β-bulge from IL-1β confers partial signaling capability onto a K145D mutant of IL-1Ra. Based on the alignment, mutational assays and our computational folding results, we hypothesize that functional regions are not central to the β-trefoil motif and cause slow folding. The IL-1β β-bulge facilitates activity and replacing it by the IL-1Ra β-turn results in a hybrid protein that folds faster than IL-1β. Inserting the β11–β12 connecting-loop, which aids inhibition, into either IL-1β or the hybrid protein slows folding. Thus, regions that aid function (either through activity or inhibition) can be inferred from folding traps via structural differences. Mapping functional properties onto the numerous folds determined in structural genomics efforts is an area of intense interest. Our studies provide a systematic approach to mapping the functional genomics of a fold family.

Keywords: interleukin-1β, interleukin-1Ra, protein folding, protein function, structure-based models

The folded structure of a protein contains information about both its function and its folding (1–8). One must decouple the effects of the two to control folding (9) and design fast folding scaffolds. These scaffolds can then be programmed for specific function (10). The decoupling of folding and function requires a detailed understanding of how functional regions and binding sites affect protein folding. Evolutionary pressure is toward conserving protein function and evidence has been accumulating that the functional regions of natural proteins do not significantly aid folding and might in fact interfere with it. Early mutation studies showed that binding site residues are not optimized for protein stability (11, 12), and protein stability is partially correlated with folding rates (13). More recent evidence from WW domains shows that there exist independent networks of residues that contribute either to function or to structural integrity (14, 15) and likely to folding. Folding simulations (16) and experiments (17, 18) on these domains have shown that folding rates can be increased at the expense of function. In fact, the folding barrier for these small domains can be removed altogether through functional loop mutations (18). In this article, we systematically mutate the functional residues of two structurally similar proteins to computationally examine the connections between structure, function, and folding of complex proteins.

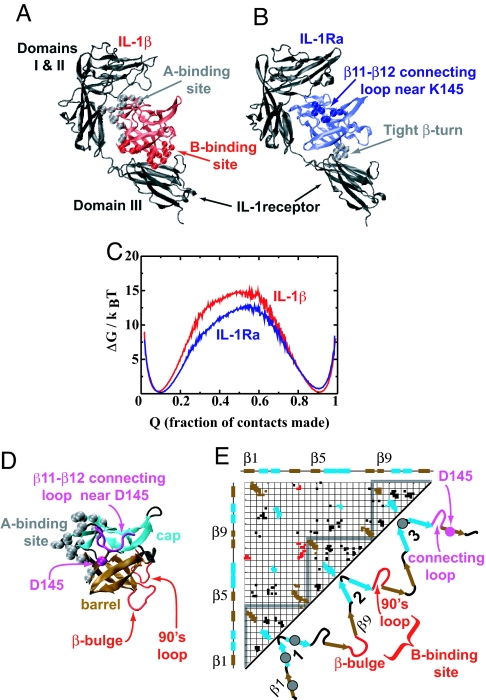

Proteins with similar native structures fold similarly (19). The cytokines interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and interleukin-1Ra (IL-1Ra) have coevolved to competitively bind the IL-1 receptor (20–22). Despite having a similar number of residues (23), the same stability (23) and the same global fold (21, 22) (Fig. 1 A and B), IL-1Ra folds faster than IL-1β (experiments by K. Hailey and P.A.J., unpublished results, and MD simulations: Fig. 1C). Their fold, the β-trefoil, is characterized by 12 β-strands folded into three similar β–β–β-loop–β (trefoil) units (25). The overall fold has a pseudo threefold symmetry and consists of a six-stranded-barrel capped by a triangular hairpin triplet (25, 26) (Fig. 1 C and D). Proteins that fold to this structure are known to fold slowly (9, 26–29).

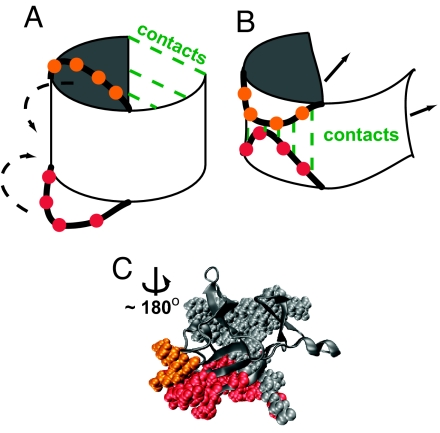

Fig. 1.

A comparison of IL-1β and IL-1Ra. (A and B) IL-1β and IL-1Ra bound to the IL-1 receptor. IL-1β binds domains I and II of the receptor through site A, induces a conformational change, and binds domain III. In contrast, IL-1Ra binds only domains I and II. (C) Free-energy barriers for IL-1β and IL-1Ra near the folding temperature (see Methods). Higher barriers imply slower folding rates. (D) A view of IL-1β showing the cap (cyan) and barrel (brown) of the β-trefoil fold. A-site residues are marked as gray spheres. Loops that make up the B-site are in red, and the β11–β12 connecting-loop and D145 are shown in purple. Other loops and turns are colored black. (E) The contact map of IL-1β and a cartoon of the extended protein showing the three trefoils with the β-strands numbered 1–12. Each trefoil has four β-strands and a long loop connecting the last two strands. The color scheme is the same as in D. Gray circles indicate regions that contain residues from the A-site. The contact map is a two-dimensional representation of the structure of the protein. Every colored square on the contact map represents a contact between the corresponding residues on the horizontal and vertical axes. Contacts are colored according to whether they are cap contacts (cyan) or barrel contacts (brown). B-site contacts are in red. All other contacts are colored black. The gray triangles in the contact map contain contacts within the corresponding trefoil. All protein figures are made by using the software VMD (24).

IL-1β, a natural activator, has two known binding sites, A and B. Both sites bind the IL-1 receptor, but only the B-site triggers a signal cascade (21, 22, 30, 31). The inhibitor, IL-1Ra, has only the A-site (22, 30, 31) (Fig. 1B), so it binds the receptor and blocks further signaling (22, 30). Most of the B-site can be extracted from structural differences between the two proteins. In fact, a structural alignment (24, 32, 33) of the proteins shows that the largest loop insertion in IL-1β is a β-bulge located in the B-site (Fig. 1 D and E). β-bulges are formed because of a mismatch of hydrogen bonds in a β-sheet and are usually functional (34). The alignment also shows that the only insertion in IL-1Ra is in the connecting loop between β-strand 11 and β-strand 12 (Fig. 1 D and E). This longer loop makes contact with K145 only in IL-1Ra (35). It has been experimentally observed (36) that replacing the corresponding tight β-turn of IL-1Ra with the functional β-bulge partially restores signaling activity in a K145D IL-1Ra mutant. In the present article, we explore the effect of functional loops on folding by making the opposite mutations (replacing the IL-1β β-bulge with the IL-1Ra β-turn and inserting the IL-1Ra β11–β12 connecting loop) in folding simulations of IL-1β.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of a coarse-grained structure-based model of IL-1β have uncovered backtracking along the folding route (29). Backtracking is the formation, breaking, and refolding of a subset of native contacts as the protein proceeds from the unfolded to the folded state. IL-1β folds slowly in simulations in part because of this backtracking. The first contacts formed after backtracking are between the β-bulge (residues 48–53) and a cap loop (residues 92–4: the 90s loop) (29). We replace the β-bulge with the tight β-turn from IL-1Ra and create a hybrid model of IL-1β (HYBβ). This mutation reduces the tertiary interactions between the turn and the long cap loop in HYBβ, simplifies the shape of the protein, and possibly disrupts the B-site (21). Backtracking and the barrier to folding also reduce significantly. Thus, the existence of the B-site complicates folding.

The mutation K145D in IL-1Ra is known to restore partial signaling activity in cell assays (36, 37). Although residue 145 is well aligned in both proteins, the K145 of IL-1Ra makes contacts with the longer β11–β12 connecting loop, whereas the D145 of IL-1β has no corresponding interactions (35). As stated earlier, the longer connecting loop is a structural difference between the proteins (Fig. 1 D and E). Inserting this loop and its associated contacts with K145 into IL-1β and the hybrid, HYBβ, decreases the folding rate and changes the folding route. The longer connecting loop and K145 improve inhibition, which is the function of IL-1Ra. Thus, our results indicate that within proteins of a fold family, structurally different regions not only interfere with folding but are also involved in function. The conserved structural regions likely facilitate protein folding.

Results

Structural Differences Coincide with Residues Used to Activate the Inhibitor, IL-1Ra.

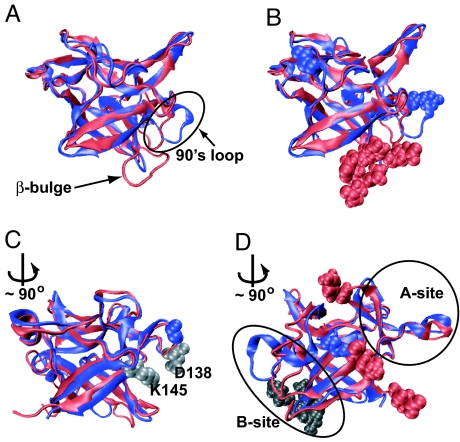

We use the structural alignment algorithm, STAMP (32), to align IL-1β and IL-1Ra and examine the local structural differences between them. Fig. 2 shows different views of this alignment. Despite a low sequence similarity (26%) (23), the two proteins are remarkably similar and the A-site (21, 22, 31) common to both, aligns well and has no insertions or major structure changes (Fig. 2D). In this article, we focus on those regions that are the most different, namely gaps in the structural alignment (red and blue spheres in Fig. 2 B, C, and D). We find that there are two main structural differences.

Fig. 2.

Different views of the structure alignment of the proteins IL-1β (red) and IL-1Ra (blue). Residues shown as red (IL-1β) and blue (IL-1Ra) spheres mark regions with the largest differences in structure. The rotation, when shown, is about the barrel axis and transforms the previous figure into the current one. (A) The two aligned proteins in approximately the same orientation as Fig. 1 A and B. The proteins are remarkably similar but an increased loop length is clearly visible in the β-bulge region. (B) The same orientation as in A. The structure of the loops in the 90s region is different even though the lengths of the loops are the same in the two proteins. The residue (G140) in the longer β11–β12 connecting loop of IL-1Ra is marked at the top left of the figure. (C) The gray spheres depict the interacting residues D138 and K145 that pin the connecting loop to the barrel. The loop is longer and has increased flexibility because of the insertion of G140 (shown as a blue sphere). (D) The three remaining structurally different residues are marked as red spheres. The cap residue is Y24. Residue 63 is on the cap/barrel interface and shows up as a change in structure in both proteins. In IL-1Ra, residue 63 interacts with the 90s loop. The terminal residue is S153. The β-bulge is shown (gray spheres) in the background for reference.

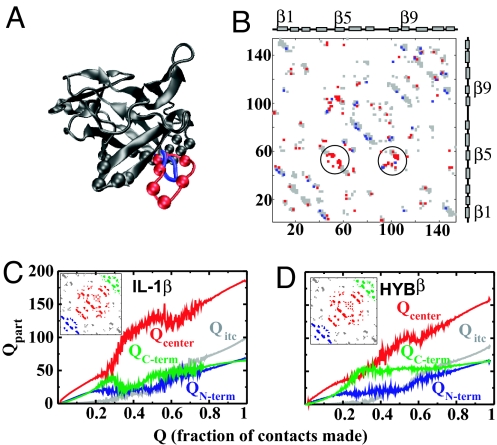

The B-site region, (21, 31), present only in IL-1β, has the largest structural differences. The β-bulge (21, 31), one of two loops that make up the B-site, is the longest insertion in the structure of IL-1β. To reduce the differences between the structures of the proteins, we replace the β-bulge (residues 46–57) in IL-1β by the tight β-turn (residues 50–55) of IL-1Ra. The structure and contact map of the hybrid protein, HYBβ are given in Fig. 3 A and B.

Fig. 3.

A comparison of IL-1β and HYBβ. (A) Aligned structures of HYBβ and IL-1β. The gray regions are common to both proteins. The differences are in red (IL-1β: the β-bulge) and blue (HYBβ: tight β-turn). The gray and red spheres depict the Cα atoms of the residues in the B-site. (B) Contact maps of IL-1β (422 contacts) and HYBβ (384 contacts). The map is symmetric about the diagonal, and both triangles are shown for clarity. Gray contacts are common to both proteins. The red contacts are present only in IL-1β and the blue ones only in HYBβ. The circled contacts involve the β-bulge. The x and y axes give residue numbers, and the index is of the larger protein, here, IL-1β. (C and D) How different parts of the protein fold. The Insets show the different regions into which the two proteins are partitioned. The color of the parts matches the color of the Qparts. (C) IL-1β. The initial rise and fall of the green QC-term denotes the backtracking. The red Qcenter shows a marked increase with a reduction in the structure of the green region. (D) HYBβ. The C-terminal region forms early and stays formed. The red region increases almost linearly with Q.

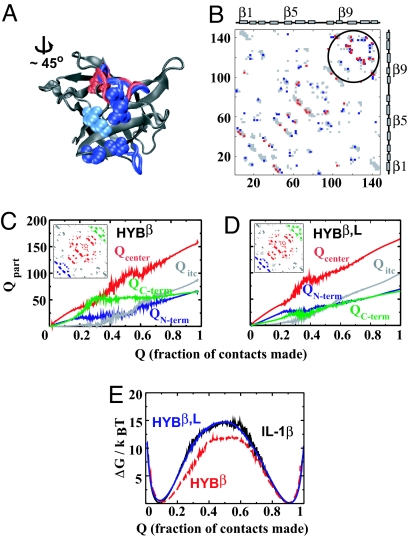

IL-1Ra is longer than IL-1β in only one region, a β11–β12 connecting loop that interacts with K145. The inserted residue, G140, makes the loop longer and more flexible and allows for interaction with K145. There are no interactions (35) between the corresponding loop and the D145 of IL-1β, and a K145D mutation restores partial activity in IL-1Ra (36). We introduce the longer connecting-loop of IL-1Ra (residues 125–136 of HYBβ are replaced by residues 130–142 of IL-1Ra) with its associated contacts with K145 into HYBβ to create a new mutant, HYBβ,L (Fig. 4 A and B). We start and end replacements from Cα atoms of residues that align within 0.5 Å of each other (see Methods for a detailed description). Thus, a longer region of the β11–β12 connecting loop is replaced. It should be noted that both the mutated loops are surface loops and not part of the core of the protein. For detailed structure and contact map pairs of IL-1Ra, HYBβ, and HYBβ,L similar to Fig. 1 D and E see supporting information (SI) Fig. S1.

Fig. 4.

A comparison of IL-1β, HYBβ and HYBβ,L. (A) The aligned structures of HYBβ and HYBβ,L. Common regions are in gray. The tight β-turn common to both hybrids is shown at the bottom right as a blue tube. The blue β11–β12 connecting loop from IL-1Ra replaces the one residue shorter red loop of HYBβ. Residues of IL-1Ra that make contact with residue 145 (pale blue) are shown as blue spheres. A residue whose contact is present in HYBβ but not in IL-1Ra is depicted by red spheres. (B) Contact maps of HYBβ (384 contacts) and HYBβ,L (398 contacts). Gray contacts are present in both structures. The red contacts are present only in HYBβ, and the blue ones are present only in HYBβ,L. The largest differences in the contacts are in the third or C-terminal trefoil. (C) The HYBβ data are reproduced from Fig. 3D. (D) HYBβ,L. The central trefoil (red) forms and stabilizes earlier than in HYBβ. The C-terminal region (green) forms late along with the N-terminal trefoil (blue). The stiffer C-terminal trefoil is harder to fold to. (E) Free-energy barriers for IL-1β and the two hybrids. Removal of the β-bulge reduces the barrier, whereas the addition of the stiffer third trefoil restores it.

HYBβ Folds Faster than IL-1β and Has Significantly Reduced Backtracking.

To study the effect of replacing the β-bulge on folding, we compare MD simulations of a structure-based Cα model (38) (see Methods) of IL-1β with those of HYBβ. We use Q, the fraction of native contacts formed, as a reaction coordinate (38) (see Methods). Q varies from 0 to 1 as the protein folds. We partition (29) the IL-1β and HYBβ contacts into four parts and examine the dynamics of each of these as the protein folds. The average number of contacts formed in a given part is denoted by Qpart and calculated by averaging over all protein snapshots that have a given Q. The parts approximately correspond to intratrefoil contacts of the three trefoil regions (the N-terminal trefoil: QN-term, the C-terminal trefoil: QC-term, the central trefoil region: Qcenter) and intertrefoil contacts (Qitc). The exact contacts included in each of the Qparts for IL-1β and HYBβ are given in the Insets of Fig. 3 C and D.

Fig. 3 C and D show that the C-terminal contacts are formed early in both proteins. However, in IL-1β, as Q increases, the C-terminal contacts break (QC-term decreases), whereas Qcenter increases (Fig. 3C). The C-terminal contacts are reformed at higher Q values. We term this formation, unraveling, and reformation of the C-terminal contacts backtracking. IL-1β folds slower than other β-trefoil proteins because of this backtracking (29). The first contacts that form after the unfolding of the C-terminal region, i.e., after backtracking, are contacts between the 90s loop and the β-bulge (Figs. 1 D and E and 2A). As stated, these contacts are involved in the B-site binding surface (21, 31).

The C-terminal contacts of HYBβ form early but, unlike in IL-1β, stay folded (Fig. 3D). At intermediate Q values (0.3–0.6), the central trefoil is formed in addition to the C-terminal contacts. There is almost no backtracking present in HYBβ. When we focus on the B-site, we find that the few remaining contacts between the 90s loop and the shorter β-turn form late (Q ≈ 0.8) in the folding transition. Based on these observations, we conclude that the structure of HYBβ is less complex and easier to fold to.

The β-bulge interacts with the cap loop and creates a binding surface for the third domain of the receptor (Fig. 1A). Similar surfaces have been found in other members of the interleukin family (39, 40), and it is clear that the B-site and contacts between the two distal loops are required for function. It is this necessity to conserve function that complicates folding.

Insertion of the Longer IL-1Ra β11–β12 Connecting Loop and Its Contacts with K145 into HYBβ Hinders Folding.

It is easier to analyze and dissect the result of topological complexity in a protein when its folding is compared with that of a less-complex structure. Thus, HYBβ is a better control for the insertion of additional loops because it is a simpler structure and faster folding than IL-1β. We call the protein with both the IL-1Ra β-turn and the IL-1Ra connecting-loop HYBβ,L. Its structure and contact map are given in Fig. 4 A and B.

Unlike HYBβ (Fig. 4C) and wild-type IL-1β (Fig. 3C), the C-terminal region of HYBβ,L forms late. The central trefoil contacts form and stabilize earlier (Fig. 4 C and D: at Q ≈ 0.4, Qcenter (HYBβ) ≈45%, whereas Qcenter (HYBβ,L) ≈70%). A comparison of the free-energy (ΔG) profile shows that this change in folding route is also accompanied by an increase in barrier to folding (Fig. 4E). We find that HYBβ has the lowest barrier, whereas HYBβ,L has a barrier almost identical to that of wild-type IL-1β. This increased barrier is not caused by backtracking. The folding rate decreases even further in a mutant of IL-1β with only the β11–β12 connecting loop replaced (results not shown).

The contacts between the β11–β12 connecting loop and the IL-1Ra residue K145 pins the loop to the barrel and makes the third trefoil of IL-1Ra less flexible than that of IL-1β. This lack of flexibility interferes with signaling and aids inhibition. The stiffer shape is harder to fold to, and we again observe a tradeoff between function and folding.

Discussion

Two Competing “Modes” of Folding in IL-1β.

On further examination of the IL-1β trajectories (26) and B-site contact formation, we find that there are two competing modes of folding. Fig. 5 gives a schematic representation of the two modes. The first, barrel closure, requires that the N- and C-terminal trefoils be partially stable (Fig. 5A). The other, formation of the B-site, stabilizes the central trefoil but induces lateral pinching of the barrel along its axis while forming contacts between the 90s cap loop and the β-bulge. This pinch destabilizes the terminal trefoils (Fig. 5B). The two modes compete with each other.

Fig. 5.

Cartoon of the two modes of folding. (A) Barrel closure. (B) B-site formation pinches the barrel, which impedes the folding of the gray area. (C) IL-1β. The loop residues that cause the pinch are shown in red and orange. The residues marked as gray spheres are from the C-terminal trefoil. The rest of the protein is shown as gray ribbons. This orientation of the protein is obtained from Fig. 2A by a rotation of ≈180° about the barrel axis.

The C-terminal trefoil gets stabilized first because of the arrangement of local contacts (29). This impedes the formation of the B-site, and the trefoil must unfold before further folding. The central trefoil and the B-site can then be stabilized, followed eventually by barrel formation. This folding, unfolding, and refolding is backtracking. Occasionally, the protein proceeds by the first mode and takes the entropically unfavorable route of barrel closure before stabilizing the more local central trefoil. Removing the pinch in the barrel by mutating the β-bulge makes the topology of the protein simpler. The central trefoil can now form in conjunction with the C-terminal trefoil, and backtracking is almost eliminated.

In simulations of IL-1β, the two modes are finely balanced and models of IL-1β with a slightly altered ratio of secondary-to-tertiary structure let the protein fold by alternative routes that favor one mode over the other (26, 29).

Functional Sites Cause Topological Traps in Both IL-1β and IL-1Ra.

There has been evidence (18) that functional residues are a hindrance to folding. The reasoning is as follows: A mutation in binding site residues causes reduced function. In order for the protein to function correctly, such residues need to be conserved and cannot be optimized for folding. The rest of the protein can evolve to make folding more efficient by making the energy landscape more funnel-like (19, 41–44). Thus, it is possible that the most hard-to-fold parts of the protein (which cause trapping during folding) are the functional sites. The above argument has been put forth to explain why binding site mutations increase folding rate (17, 18).

Trapping, which causes reduced folding rates, can either be energetic (45) (e.g., nonnative interactions get stabilized while folding) or topological (46) (e.g., the shape of the protein makes it hard to fold to). Larger proteins have folding units (foldons) (47) that cause topological complexity and can lead to multiple possible folding routes (26, 47). The route that a protein folds by is decided by the details of the protein sequence and structure. Thus, functional loops that cause complexity and trapping can modulate folding routes and rates. Loops can increase complexity by increasing local contact order. At other times, functional loops from distant sites within the protein can interact to create a binding surface, as in the B-site of IL-1β. Such interactions make the overall fold topology significantly more complicated. (A cartoon of both these types of functional interactions is given in Fig. S2.)

IL-1β is a signaling protein and functions by binding the third domain of the IL-1 receptor (20, 21, 30, 31) (Fig. 1A). It does this by providing a binding surface that contains the β-bulge (21). The function of IL-1Ra, on the other hand, is to block the receptor and provide signaling control (20, 30, 31). This seems to be achieved in a number of ways, one of which is the reduction in flexibility of the third trefoil cap region. Thus, in both IL-1β and IL-1Ra, structural insertions are functionally significant, make the shape of the protein more complex, and complicate and slow folding.

Function evolves in proteins through the acquisition of surface loops (48), and such loops are believed to not affect protein stability (49) and folding. Our results indicate that protein structure, function, and folding are inextricably related and that the structural differences between structurally similar proteins correlate not only with functional regions but also with topological folding traps. The structurally conserved regions between such proteins may facilitate structural stability and folding.

Are All Structural Differences Functional?

In addition to the two main structural differences treated earlier, three single-residue structural differences exist between IL-1β and IL-1Ra. Two of these, Y24 and S153, are insertions in the IL-1β sequence. The third, K63 in IL-1β, exists in both proteins and has different structures. All three residues lie on the interface between the two binding sites (Fig. 2D). The mutation K63S in IL-1β, affects signaling without affecting binding (31) and thus disrupts cross-talk between the A and B sites of IL-1β. It is possible that the other two residues, Y24 and S153, have a similar role and foster communication between the two binding sites. (S153 may be a false positive because it is the C-terminal residue of IL-1β.)

Methods

Structure Alignment.

To create a structure of IL-1β with the IL-1Ra loops, we begin by aligning the two structures (PDB ID codes 6I1B and 1ILR) using the structural alignment extension (Multiseq) (33) of the program VMD (24) (Fig. 2). We then create HYBβ from this alignment by deleting residues 46–57 of IL-1β and replacing them by residues 50–55 of IL-1Ra. We start and end replacements from residues whose neighboring Cα atoms (not in the loop to be replaced) are within 0.5 Å. To create HYBβ,L, we replace residues 125–136 of HYBβ by residues 130–142 of IL-1Ra. Residues D145 of IL-1β and K145 of IL-1Ra align well. Various views of the aligned structures, and the hybrid proteins are shown in Fig. 2, 3A, and 4A. The resulting proteins have 153 (IL-1β), 145 (IL-1Ra has 152 residues, but the PDB structure has only residues 8:152), 147 (HYBβ), and 148 (HYBβ,L) residues.

The Multiseq (33) extension of VMD (24) uses the measure Qres to determine how similar in structure a given residue is to another. Because we concentrate on structural gaps (Qres = 0) in this article, we do not use this measure to determine subtle structural differences.

Contact Maps.

The contact map gives all of the possible interactions between a given residue and the other residues in a given structure of the protein. These maps are calculated from the IL-1β and hybrid folded structures by using contacts of structural units (CSU) analysis (35). The interactions of each residue are then projected onto its Cα atom. The contact maps of native IL-1β and the hybrids are given in Figs. 1D, 3B, and 4B. The proteins have 422 (IL-1β), 400 (IL-1Ra), 384 (HYBβ), and 398 (HYBβ,L) contacts. (Also see Fig. S1.)

We also add the contacts of Asp 145 from IL-1Ra into our model for HYBβ,L. The residues that are part of the contacts are shown in Fig. 4A. The residues whose interactions are added are numbered 98, 100, and 133 in HYBβ,L. The residue whose interaction is deleted is numbered 118. K/D 145 align with residues 139 and 140 in HYBβ and HYBβ,L, respectively.

Native Structure-Based (Gō) Model and Molecular Dynamics.

We use a coarse-grained and energetically unfrustrated model (38) of the proteins in our MD simulations. Our model contains only the Cα atom of each residue, and the interactions between the Cα atoms are only those given by the contact map. Nonnative interactions are not included. Because the native-state contact map specifies all of the interactions present, the model protein has a global energy minimum at its native state. Details of the model are given in refs. 29 and 38. The model is summarized in Fig. S3. Simulations are performed at folding temperature, which is the temperature at which the unfolded and folded states are equally populated at equilibrium. This ensures that we have adequate sampling of not only the folded and the unfolded states but also the transition region. Proteins that have similar stabilities have similar folding temperatures. We use the sander_classic program of the AMBER5 (50) package to perform all simulations.

To ensure that the change in folding routes are not the result of a change in the balance of the energy between the contacts and dihedrals (because of a change in the number of residues and contacts in the three proteins) we also performed control simulations where the contact strengths in the two hybrids are tuned such that the balance of energies is the same as in wild-type IL-1β (153 residues, 422 contacts) (26). We find that this does not significantly alter folding routes or barriers.

IL-1Ra has a disulfide bond (22). These “chemical” bonds are stronger than the usual “physical” contact interactions and are not well represented in “vanilla” Cα models of proteins. Thus, results from simulations of IL-1Ra might not have significant experimental relevance unless the disulfide bond is mutated. The experiments that we cite have been done with the disulfide bond mutated out. Also, the “cut and paste” technique that we use to create hybrid structures is not useful to recreate structural regions like the B-site, where the 90s loop is structured differently in both proteins. For these reasons, we do not present any IL-1Ra-based hybrid simulations in this article.

Enhanced Sampling.

The β-trefoil fold is a topologically difficult structure to fold to. It is slow folding and not easily accessible in normal constant-temperature MD simulations. Thus, to acquire adequate sampling of the whole energy landscape, we use a modified multicanonical method (29). The sampling is enhanced in the transition region between the folded and the unfolded states by rescaling the usual MD force by a Gaussian weight. The resulting sample is then reweighted (51) to acquire the usual canonical distribution. Further details of the method are given in Gosavi et al. (29)

Reaction Coordinate.

We use the fraction of native contacts (Q) formed in a given snapshot of the protein as the reaction coordinate (38). To examine the progress and the mechanism of folding, we plot the free energy (ΔG), the number of contacts made in a given part of the protein (Qpart), etc., as functions of Q.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Dr. Leslie Chavez for valuable discussions and support especially during the initial part of the project, Kendra Hailey and Dominique Capraro for providing us with unpublished results, and Nikolaos Sgourakis for suggestions during the preparation of the manuscript. This work was supported in part by the National Science Foundation-sponsored Center for Theoretical Biological Physics (Grants PHY-0216576 and -0225630) by Grant MCB-0543906. P.C.W. was supported by National Institutes of Health Molecular Biophysics Training Grant T32 GM08326 at the University of California at San Diego.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0801343105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Schug A, Whitford PC, Levy Y, Onuchic JN. Mutations as trapdoors to two competing native conformations of the Rop-dimer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:17674–17679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706077104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kloczkowski A, Sen TZ, Jernigan RL. Promiscuous vs. native protein function. Insights from studying collective motions in proteins with elastic network models. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2005;22:621–624. and references therein. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang J, Lu Q, Lu HP. Single-molecule dynamics reveals cooperative binding-folding in protein recognition. PLoS Comp Biol. 2006;2:e78–842. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsai CJ, Kumar S, Ma B, Nussinov R. Folding funnels, binding funnels, and protein function. Protein Sci. 1999;8:1181–1190. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.6.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frauenfelder H, Sligar SG, Wolynes PG. The energy landscapes and motions of proteins. Science. 1991;254:1598–1603. doi: 10.1126/science.1749933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Itoh K, Sasai M. Coupling of functioning and folding: Photoactive yellow protein as an example system. Chem Phys. 2004;307:121–127. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krishna MMG, Lin Y, Rumbley JN, Englander SW. Cooperative omega loops in cytochrome c: Role in folding and function. J Mol Biol. 2003;331:29–36. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00697-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abkevich VI, Shakhnovich EI. What can disulfide bonds tell us about protein energetics, function and folding: Simulations and bioinformatics analysis. J Mol Biol. 2000;300:975–985. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dubey VK, Jihun Lee J, Somasundaram T, Blaber S, Blaber M. Spackling the crack: Stabilizing human fibroblast growth factor-1 by targeting the N and C terminus β-strand interactions. J Mol Biol. 2007;371:256–268. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arico-Muendel CC, Patera A, Pochapsky TC, Kuti M, Wolfson AJ. Solution structure and dynamics of a serpin reactive site loop using interleukin-1β as a presentation scaffold. Prot Eng. 1999;12:189–202. doi: 10.1093/protein/12.3.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shoichet BK, Baase WA, Kuroki R, Matthews BW. A relationship between protein stability and protein function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:452–456. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.2.452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schreiber G, Buckle AM, Fersht AR. Stability and function: Two constraints in the evolution of barstar and other proteins. Structure (London) 1994;2:945–951. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(94)00096-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plaxco KW, Simons KT, Baker D. Contact order, transition state placement and the refolding rates of single domain proteins. J Mol Biol. 1998;277:985–994. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Socolich M, et al. Evolutionary information for specifying a protein fold. Nature. 2005;437:512–518. doi: 10.1038/nature03991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Russ W, Lowery DM, Mishra P, Yaffe MB, Ranganathan R. Natural-like function in artificial WW domains. Nature. 2005;437:579–583. doi: 10.1038/nature03990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karanicolas J, Brooks CL., III Integrating folding kinetics and protein function: Biphasic kinetics and dual binding specificity in a WW domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:3432–3437. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0304825101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gruebele M. Fast protein folding: Evolution meets physics. C R Biol. 2005;328:701–712. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jäger M, et al. Structure–function–folding relationship in a WW domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:10648–10653. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600511103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Onuchic JN, Wolynes PG. Theory of protein folding. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14:70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dinarello CA. Blocking IL-1 in systemic inflammation. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1355–1359. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vigers GPA, Anderson LJ, Caffes P, Brandhuber BJ. Crystal structure of type-I interleukin-1 receptor complexed with interleukin-1β. Nature. 1997;386:190–194. doi: 10.1038/386190a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schreuder H, et al. A new cytokine-receptor binding mode revealed by the crystal structure of the IL-1 receptor with an antagonist. Nature. 1997;386:194–200. doi: 10.1038/386194a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Latypov RF, et al. Biophysical characterization of structural properties and folding of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist. J Mol Biol. 2007;368:1187–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD visual molecular dynamics. J Mol Graphics. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murzin AG, Lesk AM, Chothia C. β-Trefoil fold. Patterns of structure and sequence in the Kunitz inhibitors interleukin-1β and 1α and fibroblast growth factors. J Mol Biol. 1992;223:531–543. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90668-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chavez LL, Gosavi S, Jennings PA, Onuchic JN. In the energy landscape of the β-trefoil family, multiple routes lead to the folded state. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:10254–10258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510110103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Makhatadze GI, Clore GM, Gronenborn AM, Privalov PL. Thermodynamics of unfolding of the all-β sheet protein interleukin-1β. Biochemistry. 1994;33:9327–9332. doi: 10.1021/bi00197a037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heidary DK, Gross LA, Roy M, Jennings PA. Evidence for an obligatory intermediate in the folding of interleukin-1β. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:1–583. doi: 10.1038/nsb0997-725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gosavi S, Chavez LL, Jennings PA, Onuchic JN. Topological frustration and the folding of interleukin-1β. J Mol Biol. 2006;357:986. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.11.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Auron PE. The interleukin-1 receptor: Ligand interactions and signal transduction. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1998;9:221–237. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(98)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koussounadis AI, Ritchie DW, Kemp GJL, Secombes CJ. Analysis of fish IL-1β and derived peptide sequences indicates conserved structures with species-specific IL-1 receptor binding: Implications for pharmacological design. Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10:3857–3871. doi: 10.2174/1381612043382585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Russell RB, Barton GJ. Multiple protein sequence alignment from tertiary structure comparison. Proteins Struct Funct Genet. 1992;14:309–323. doi: 10.1002/prot.340140216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roberts E, Eargle J, Wright D, Luthey-Schulten Z. MultiSeq: Unifying sequence and structure data for evolutionary analysis. TBMC BioinformaticsT T. 2006;7T:382–392. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richardson JS, Getzoff ED, Richardson DC. The β bulge: A common small unit of nonrepetitive protein structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:2574–2578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.6.2574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sobolev V, Sorokine A, Prilusky J, Abola EE, Edelman M. Automated analysis of interatomic contacts in proteins. Bioinformatics. 1999;15:327–332. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/15.4.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Greenfeder SA, et al. Insertion of a structural domain of interleukin (IL)-1β confers agonist activity to the IL-1 receptor antagonist. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:22460–22466. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.38.22460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ju G, et al. TConversion of the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist into an agonist by site-specific mutagenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:2658–2662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.7.2658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clementi C, Nymeyer H, Onuchic JN. Topological and energetic factors: What determines the structural details of the transition state ensemble and “en-route” intermediates for protein folding? An investigation for small globular proteins. J Mol Biol. 2000;298:937–953. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dunn EF, et al. High-resolution structure of murine interleukin 1 homologue IL-1F5 reveals unique loop conformations for receptor binding specificity. Biochemistry. 2003;42:10938–10944. doi: 10.1021/bi0341197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kato Z, et al. The structure and binding mode of interleukin-18. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:966–971. doi: 10.1038/nsb993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thirumalai D, Klimov DK. Deciphering the timescales and mechanisms of protein folding using minimal off-lattice models. Curr Op Struct Biol. 1999;9:197–207. doi: 10.1016/S0959-440X(99)80028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Onuchic JN, Nymeyer H, Garcia AE, Chahine J, Socci ND. The energy landscape theory of protein folding: Insights into folding mechanisms and scenarios. Adv Prot Chem. 2000;53:87–152. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(00)53003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dill KA. Polymer principles and protein folding. Prot Sci. 1999;8:1166–1180. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.6.1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wolynes PG, Onuchic JN, Thirumalai D. Navigating the folding routes. Science. 1995;267:1619–1620. doi: 10.1126/science.7886447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferreiro DU, Hegler JA, Komives EA, Wolynes PG. Localizing frustration in native proteins and protein assemblies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19819–19824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709915104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shea JE, Onuchic JN, Brooks CL. Exploring the origins of topological frustration: Design of a minimally frustrated model of fragment B of protein A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12512–12517. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lindberg MO, Oliveberg M. Malleability of protein folding pathways: a simple reason for complex behaviour. Curr Op Struct Biol. 2007;17:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Orengo CA, Sillitoe I, Reeves G, Pearl FMG. What can structural classifications reveal about protein evolution? J Struct Biol. 2001;134:145–165. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2001.4398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Watson E, Matousek WM, Irimies EL, Alexandrescu AT. Partially folded states of staphylococcal nuclease highlight the conserved structural hierarchy of OB-fold proteins. Biochemistry. 2007;46:9484–9494. doi: 10.1021/bi700532j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pearlman DA, et al. AMBER, a computer program for applying molecular mechanics, normal mode analysis, molecular dynamics and free energy calculations to elucidate the structures and energies of molecules. Comput Phys Comm. 1995;91:1–41. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kumar S, Bouzida D, Swendsen RH, Kollman PA, Rosenberg JM. The weighted histogram analysis method for free-energy calculations on biomolecules. I. The method. J Comp Chem. 1992;13:1011–1021. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.