Abstract

Membrane penetration by reovirus is associated with conversion of a metastable intermediate, the ISVP, to a further-disassembled particle, the ISVP*. Factors that promote this conversion in cells are poorly understood. Here, we report the in vitro characterization of a positive-feedback mechanism for promoting ISVP* conversion. At high particle concentration, conversion approximated second-order kinetics, and products of the reaction operated in trans to promote the conversion of target ISVPs. Pore-forming peptide μ1N, which is released from particles during conversion, was sufficient for promoting activity. A mutant that does not undergo μ1N release failed to exhibit second-order conversion kinetics and also failed to promote conversion of wild-type target ISVPs. Susceptibility of target ISVPs to promotion in trans was temperature dependent and correlated with target stability, suggesting that capsid dynamics are required to expose the interacting epitope. A positive-feedback mechanism of promoting escape from the metastable intermediate has not been reported for other viruses but represents a generalizable device for sensing a confined volume, such as that encountered during cell entry.

Keywords: cell entry, heat inactivation, nonenveloped virus, Reoviridae

Mammalian orthoreovirus (reovirus) is a large, nonenveloped virus with 10 dsRNA genome segments enclosed by a bilayered capsid. The outer capsid includes 200 trimers of the N-terminally myristoylated (1, 2), membrane-penetration protein μ1, each complexed with three copies of the protector protein σ3. The μ13σ33 heterohexamers are arranged with T = 13 icosahedral symmetry, substituted at the fivefold axes by the pentameric turret protein λ2 (3, 4). Protruding from the λ2 turret is the trimeric cell-adhesion fiber σ1 (3, 5, 6).

During cell entry, the reovirus capsid undergoes a series of disassembly steps to activate its membrane-penetration machinery for delivery of particles into the cytoplasm. First, intestinal or endosomal proteases degrade σ3, leaving μ1 exposed on the surface (3, 7, 8). Cleavage of the 76-kDa μ1 protein, generating μ1δ (63 kDa) and the C-terminal fragment φ (13 kDa), accompanies this process (9). The resulting infectious subvirion particle (ISVP) can also be generated by protease digestion in vitro (10, 11).

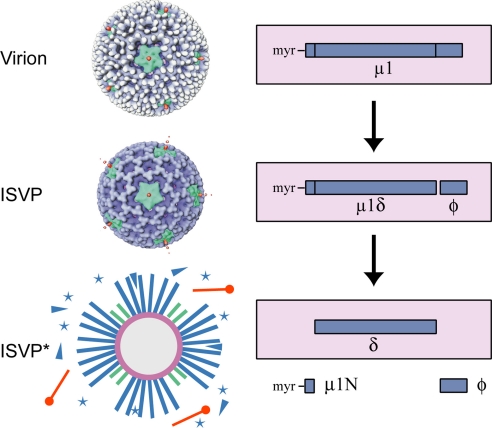

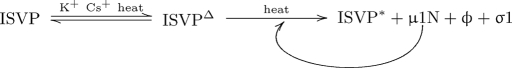

The ISVP is metastable and can be promoted to undergo further disassembly to the ISVP* in association with membrane penetration (12–16). ISVP* conversion is characterized by a major rearrangement of μ1, rendering it sensitive to further proteolysis, derepression of particle-associated transcriptase activity, and release of the σ1 fibers (12, 17). In addition, an autocatalytic cleavage of μ1δ occurs, generating the N-terminal myristoylated peptide μ1N (4 kDa) and the larger fragment δ (59 kDa) (1, 18, 19). In addition to σ1, the terminal μ1 fragments μ1N and φ are both, at least in part, released from the ISVP* (20–22). These steps are diagrammed in Fig. 1. ISVP* conversion and μ1N cleavage are both required for infectivity in cells (14, 20), and released μ1N is sufficient for forming membrane pores in vitro (22).

Fig. 1.

Reovirus particles and μ1 protein. (Left) Electron cryomicroscopy reconstructions of virions and ISVPs (3) and a diagram of ISVP*s. White, σ3; blue, μ1; green, λ2; orange, σ1; stars, released μ1N; triangles, released φ. (Right) Diagram of μ1 status in each particle type. Species inside the box are associated with particles; those outside the box are released. At least 50% of the μ1 copies in virions and ISVPs consist of full-length μ1 and μ1δ, respectively (containing uncleaved μ1), although the exact amount of cleavage is unknown (18, 19). Because standard disruption conditions for SDS/PAGE lead to μ1N cleavage (18), the main μ1 species seen in gels of ISVPs in this study is δ. μ1δ and μ1C (resulting from cleavage of μ1N only) are seen as minor species.

The mechanism promoting ISVP* conversion in cells is poorly understood. In vitro, conversion is facilitated by heat and large monovalent cations (12, 13, 23). Promotion by such nonspecific stimuli has been reported for metastable forms of other viruses (24–30). For reovirus, high particle concentration also promotes conversion (12, 16, 17, 31). More than 30 years ago, before the ISVP* had been fully recognized, Borsa et al. (31) found that in the process of converting ISVPs to cores, a factor is released that facilitates transcriptase derepression. In this report, we identify μ1N as the promoting factor and discuss the biological implications.

Results

ISVP* Conversion Approximates Second-Order Kinetics at High Particle Concentration.

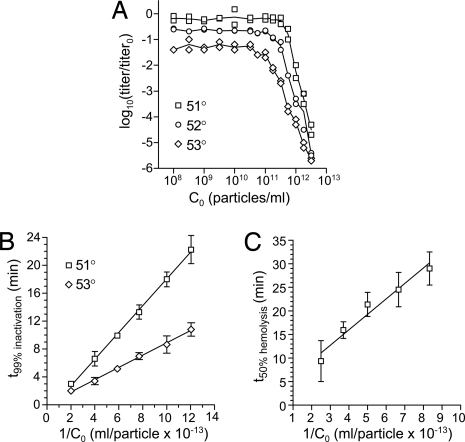

Kinetics of ISVP* conversion at low particle concentration (2 × 109 particles per milliliter), as measured by loss of infectivity upon heating, have been shown to approximate those of a first-order reaction (13). On the other hand, it has been observed that at high particle concentration, the rate of ISVP* conversion is concentration dependent (12, 16, 17, 31), inconsistent with first-order kinetics. To obtain a better understanding of conversion kinetics, we performed 15-min heat inactivations over a range of initial ISVP concentrations (C0) (Fig. 2A). At C0 between 108 and ≈1011 particles per milliliter, the extent of inactivation was unaffected by C0, confirming first-order behavior over this range (13). At C0 above ≈1011 particles per milliliter, however, the behavior transitioned to a regime in which the extent of inactivation depended strongly on C0. Conversion kinetics in the concentration-dependent regime were then measured by performing heat inactivations over short time courses bracketing the time for 99% reduction in infectivity [data not shown, but see examples in supporting information (SI) Fig. S1A]. As expected for a second-order reaction, this time was linear with respect to 1/C0 (Fig. 2B). ISVP* conversion can also be monitored by the onset of hemolytic activity (12). In hemolysis time courses (data not shown, but see Fig. S1B), the time for 50% hemolysis was also linear with respect to 1/C0 (Fig. 2C). Thus, at high particle concentrations (above ≈1011 particles per milliliter), ISVP* conversion approximates a second-order reaction.

Fig. 2.

ISVP* conversion approximates a second-order reaction at high particle concentrations. (A) ISVPs at the indicated C0 were subjected to heat treatment at 51, 52, or 53°C for 15 min, then titered by plaque assay. Titer loss is expressed as log10 change relative to a 0°C sample. Points from duplicate experiments are shown with a line connecting mean values. (B) Short time courses bracketing the time required for a 99% reduction in titer (t99%) were performed over a range of C0. The expected linear relationship for a second-order reaction is plotted. Means ± SD for three or four determinations are shown with a linear-regression fit. (C) Hemolysis reactions containing ISVPs at the indicated C0 were performed at 37°C in buffer containing Cs+, which facilitates conversion. The expected linear relationship between time to half-maximal hemolysis (t50%) and concentration is plotted. Means ± SD for four or five determinations are shown with a linear-regression fit line. Examples of time courses used to generate the points in B and C are shown in Fig. S1.

ISVP* Reaction Products Act in Trans to Promote Conversion of Other ISVPs.

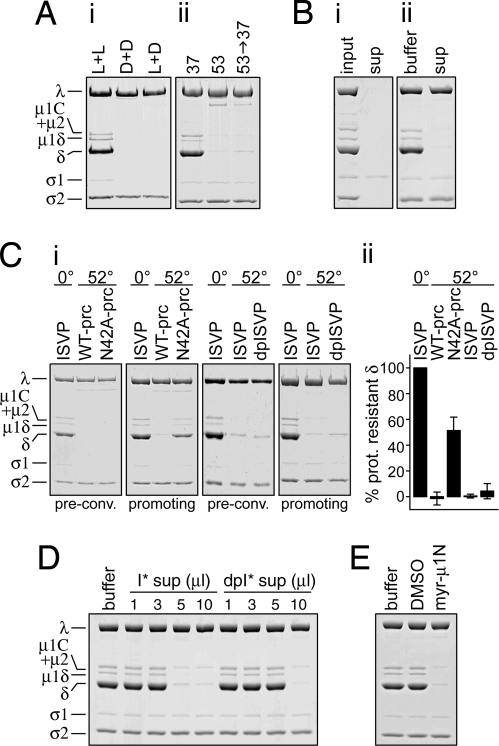

Second-order reaction kinetics implicate a promoting interaction either between input components or between input components and reaction products. To test this idea, we exploited the fact that ISVPs of reovirus strain Type 1 Lang (T1L) are more stable than those of Type 3 Dearing (T3D) (12, 13). ISVPs of either T1L or T3D, or a mixture of both, were incubated at 37°C under conditions that promote ISVP* conversion of T3D, but not T1L (Fig. 3Ai). Conversion was assayed by trypsin (TRY) sensitivity of the particle-associated μ1 cleavage products (μ1C, μ1δ, and δ), which are digested in ISVP*s but not in ISVPs. In the mixture, the ISVPs of both strains converted to ISVP*s, suggesting that converted T3D is able to promote the conversion of T1L. Additionally, when T1L ISVPs were preconverted at 53°C, chilled on ice, and then supplemented with fresh target T1L ISVPs followed by further incubation at 37°C, the target ISVPs also converted (Fig. 3Aii). These results indicate that one or more product of ISVP* conversion is able to promote the conversion of other ISVPs in trans.

Fig. 3.

Released μ1N is sufficient for promoting activity. (A) (i) ISVPs of T1L (L+L) or T3D (D+D), or a mixture of equal parts of both (L+D), were incubated at 37°C for 60 min. ISVP* conversion was assayed by TRY sensitivity of the particle-associated μ1 species (μ1C, μ1δ, and δ). (ii) T1L ISVPs were incubated at 37°C for 65 min (lane 1); at 53°C for 5 min (lane 2); or preconverted at 53°C for 5 min, chilled and supplemented with an equal part of fresh ISVPs, and incubated at 37°C for 60 additional min (lane 3). ISVP* conversion was assayed by TRY sensitivity. (B) ISVPs were preconverted at 52°C and centrifuged to pellet particles. (i) Equivalent amounts of input particles and supernatant, demonstrating efficient particle clearance (μ1N and φ are too small to be resolved on this gel). (ii) 10 μl of buffer or supernatant were added to ISVPs, and reactions were incubated at 37°C for 30 min followed by the TRY-sensitivity assay. (C) (i) WT-pRCs, N42A-pRCs, ISVPs, and dpISVPs were preconverted at 52°C. Preconversion of a duplicate sample was confirmed by the TRY-sensitivity assay (“pre-conv.”). Preconverted particles were chilled and supplemented with fresh WT ISVPs, incubated at 37°C for 30 min, and assayed by TRY sensitivity (“promoting”). Samples containing ISVPs incubated at 0°C, instead of 52°C, were analyzed in parallel. (ii) Quantitation of three or more experiments such as shown in i. Two different preparations of each particle type were used. The amount of δ remaining after the TRY-sensitivity assay is expressed relative to the amount in samples containing only unconverted ISVPs (0° lanes in i). The 50% protease-resistant δ in the N42A-pRC lane reflects preconversion of the N42A-pRCs but no promotion of the target ISVPs, which are present in equal numbers. Error bars indicate SD. (D) ISVPs or dpISVPs were preconverted at 52°C and centrifuged to pellet particles. The indicated amounts of supernatant were added to fresh WT ISVPs, and reactions were incubated at 37°C for 30 min followed by TRY-sensitivity assay. (E) ISVPs were incubated with 50 μg/ml synthetic μ1N peptide or vehicle control (1% DMSO) at 37°C for 60 min followed by TRY-sensitivity assay. All reactions contained a total final ISVP concentration of 5 × 1012 particles per milliliter.

Released Components Are Sufficient for Promoting Activity.

To test the promoting activity of components released from particles during ISVP* conversion, ISVPs were preconverted to ISVP*s at 52°C, and particles were removed by pelleting. Efficient clearance of particles from the supernatant by this method has been demonstrated (22), and a representative gel is shown here (Fig. 3Bi). Supernatant was transferred to new tubes containing target ISVPs, and after incubation at 37°C, conversion of the target ISVPs was assayed by TRY sensitivity (Fig. 3Bii). The target ISVPs converted, indicating that particle-depleted supernatant retains promoting activity. Normal conversion kinetics of recoated cores made without σ1 (data not shown, but see Fig. 4) suggest that released σ1 is not important for promoting activity. The results therefore implicate released μ1N and/or φ as factor(s) that promote ISVP* conversion in trans.

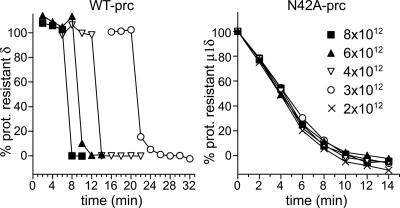

Fig. 4.

μ1N cleavage is required for concentration-dependent ISVP* conversion. WT- or N42A-pRCs at the indicated concentrations were incubated at 37°C in buffer containing Cs+, which facilitates conversion. At each time point, a sample was assayed for TRY sensitivity, and the δ remaining after TRY digestion (or μ1δ, in the case of N42A-pRCs) was quantitated. Representative experiments are shown. Gels used for quantitation are shown in Fig. S2.

μ1N Cleavage, but Not φ Cleavage, Is Required for Promoting Activity.

To test the requirement for μ1N cleavage in promoting ISVP* conversion in trans, recoated cores (32, 33) were made with a mutant form of μ1, N42A, which does not undergo μ1N cleavage (20). ISVP-like, protease-treated recoated cores (pRCs), made by chymotrypsin (CHT) digestion of N42A or wild-type (WT) recoated cores (N42A-pRCs or WT-pRCs), were preconverted at 52°C. Preconversion was confirmed by testing a duplicate sample for TRY sensitivity (Fig. 3C). Reactions were chilled and supplemented with an equal number of fresh target WT ISVPs, incubated at 37°C, and then assayed for TRY sensitivity (Fig. 3C). In this experiment, because preconverted and target ISVPs are present in equal numbers, a complete lack of promoting activity results in 50% protease sensitivity of the sample. The mutant N42A-pRCs failed to promote conversion of the target ISVPs, indicating that μ1N cleavage is required for promoting activity. In contrast, ISVPs made under conditions that prevent φ cleavage (detergent-protected ISVPs, or dpISVPs) (34) retained full promoting activity (Fig. 3C). Thus, φ cleavage is not required for promoting ISVP* conversion in trans.

φ Is Dispensable for Promoting Activity.

After preconversion of ISVPs or dpISVPs at 52°C, particles were removed from reactions by pelleting. Because φ cleavage does not occur in dpISVPs, it is removed from the supernatant along with the particles, while a substantial amount of μ1N is still released (22). Each supernatant was then tested for conversion-promoting activity against fresh target WT ISVPs (Fig. 3D). Supernatant from the preconverted dpISVPs retained promoting activity, indicating that the φ region of μ1 is not required. However, these supernatants were less efficient, suggesting a possible helper role for φ.

Synthetic μ1N Peptide Promotes ISVP* Conversion.

The observations that supernatants of ISVP* and dpISVP* conversion reactions are sufficient for promoting activity and that μ1N cleavage is required suggested that released μ1N is a promoting factor. To test this interpretation directly, synthetic myristoylated μ1N peptide (22) was assayed for promoting activity (Fig. 3E). Essentially full activity was observed with 50 μg/ml peptide, which is equivalent to the concentration of μ1N in ≈1.2 × 1013 particles per milliliter. Combined, the results demonstrate that cleaved μ1N is sufficient for conversion-promoting activity.

μ1N Cleavage Is Required for Concentration-Dependent ISVP* Conversion.

pRCs containing the N42A-mutant form of μ1 have been previously characterized as undergoing the equivalent of a normal ISVP* conversion, including rearrangement of μ1 to a protease-sensitive form, release of σ1, and derepression of transcriptase activity (20). However, the kinetics of conversion were not analyzed. Because cleaved μ1N is required for promoting activity, we hypothesized that N42A particles would fail to exhibit concentration-dependent conversion, even at high concentrations. To test this hypothesis, time courses were performed at 37°C with either N42A-pRCs or WT-pRCs, in buffer conditions and over a range of particle concentrations such that the WT particles converted with second-order kinetics. Conversion was assayed by TRY sensitivity at each time point (Fig. 4 and Fig. S2). As expected, WT-pRCs converted in a concentration-dependent manner, with lower-concentration reactions having a longer lag phase and with conversions appearing abruptly and proceeding to completion within 2 min. N42A-pRCs, however, converted gradually between 0 and 14 min, with identical kinetics for all particle concentrations. These results suggest that N42A particles do not enter into a second-order regime, up to C0 of at least 8 × 1012 particles per milliliter, which was the highest concentration tested. Nevertheless, unlike with WT-pRCs, conversion of N42A-pRCs in the first-order regime was apparent at 37°C, suggesting that these particles are destabilized. The reason for N42A instability is unknown, but may be due to an altered conformation near the autocleavage site, which could affect the contacts within or between μ1 trimers in the capsid.

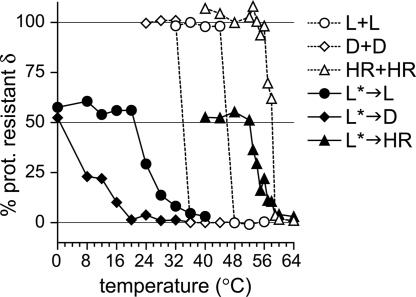

Susceptibility of Target ISVPs to Promotion in Trans Is Temperature Dependent.

The temperature dependence of promoting activity was analyzed by preconverting aliquots of WT T1L ISVPs at 52°C, then chilling on ice, supplementing with fresh target ISVPs, and incubating at different temperatures (Fig. 5). For T1L target ISVPs, no promoting activity was detected at <20°C. Activity began by 24°C and increased between 24 and 40°C. For comparison, parallel samples containing only unconverted T1L ISVPs, at an equivalent total concentration, were also analyzed, and those converted between 44 and 48°C. If, on the other hand, the less stable ISVPs of T3D were used as targets, significant promoting activity was observed at 8°C. Conversely, ISVPs of the heat-resistant mutant IL62–3 (15), which are more stable than those of T1L, required temperatures >50°C for susceptibility to promotion. In all three cases, the presence of preconverted ISVP*s led to a shift in the temperature curve relative to the parallel reaction without preconverted ISVP*s; however, the relative order of stability of the three clones (IL62–3 > T1L > T3D) was maintained. These results suggest that flexibility of the target ISVP is required for susceptibility to promotion.

Fig. 5.

Susceptibility of target ISVPs to promotion in trans is temperature dependent. Aliquots of WT T1L ISVPs were preconverted at 52°C, chilled on ice, and supplemented with an equal part of T1L ISVPs (L*→L), T3D ISVPs (L*→D), or ISVPs of the heat-resistant mutant IL62–3 (L*→HR). Alternatively, reactions contained only T1L ISVPs (L+L), T3D ISVPs (D+D), or IL62–3 ISVPs (HR+HR), without any preconverted particles. Reactions were incubated at the indicated temperature and then assayed for TRY sensitivity, and the δ remaining after TRY digestion was quantitated. For samples containing preconverted ISVPs, 50% protease-resistant δ indicates no promoting activity because the preconverted ISVPs and target ISVPs are present in equal parts. Each point represents the mean of two or three determinations.

Discussion

The metastable entry intermediate of reovirus, the ISVP, can be promoted to undergo ISVP* conversion by increased temperature or increased size of monovalent (group IA) cations. These stimuli are interchangeable and can be covaried to control the rate of conversion. In addition, high particle concentrations can promote ISVP* conversion. At low particle concentrations, ISVP* conversion exhibits first-order, or concentration-independent, kinetics. However, at concentrations above ≈1011 particles per milliliter, the kinetic data for ISVP* conversion fit well to a second-order model. This result implicates an interaction between particles, or between particles and released components, that promotes ISVP* conversion. The reaction kinetics are poorly fit by a third-order model (data not shown).

In this study, we identified μ1N, the N-terminal fragment of μ1, as a virus-derived promoting factor. In unconverted ISVPs, μ1N is buried near the base of the μ1 trimer (4, 19); cleavage and release of the peptide occurs during ISVP* conversion (18, 20–22). The activity of μ1N supplied in trans therefore represents a positive-feedback mechanism for promotion.

Cleavage of μ1N was required for promoting activity, as the noncleaving mutant N42A (20) failed to exhibit concentration-dependent conversion and also failed to promote conversion of WT ISVPs. In the mutant, the μ1N region may be sterically hindered, unaccessible, or not presented in the proper conformation. Alternatively, there may be a specific requirement for the free C-terminus of μ1N or for μ1N oligomerization.

The interacting epitope on the target ISVP is unknown. However, the correlation between the temperature dependence of promoting activity and the heat stability of the target ISVP suggests that target flexibility is required, probably to expose or create the interaction site for the promoting factor μ1N. Perhaps μ1N interacts with another intermediate between the ISVP and ISVP*, which is accessed by reversible “breathing.” There is some evidence for such an intermediate. Using circular dichroism, Borsa et al. (35) observed that at low temperature, the presence of Cs+ ions induced a reversible conformational change in ISVPs, which upon heating was followed by a further irreversible change (probably ISVP* conversion).

We propose a model (Fig. 6) in which the ISVP breathes reversibly to the intermediate ISVPΔ. Population of the ISVPΔ state is controlled by temperature and monovalent cations. If sufficient thermal energy is present, the ISVPΔ can spontaneously convert to the ISVP*. In addition, the ISVPΔ presents an interacting epitope for the promoting factor μ1N, allowing positive-feedback promotion of ISVP* conversion.

Fig. 6.

Model of ISVP* conversion. See Discussion for details.

Even at high particle concentrations, there is a lag phase before the onset of detectable conversion (see Fig. 4 and Fig. S1B). The length of this lag is concentration dependent. Although the kinetic-order determinations were made by measuring the time to a point well past the onset of conversion, specifically to 99% titer loss or 50% hemolysis, these times also include the lag phase. Because conversion at high particle concentration is so rapid once it begins, in effect what was measured is the length of the lag. We interpret the lag phase as a slow first-order reaction, which continues until sufficient promoting factor has been accumulated to begin promoting in trans. Addition of the synthetic μ1N peptide is therefore expected to allow bypass of the lag phase.

Accumulation of the promoting factor could be due to conversion of a fraction of particles in the population. At 37°C, ISVP* conversion was not discernible in the lag phase (see Fig. 4); however, using a more sensitive assay, such as transcriptase activity (12), conversion may be detectable. Another notable possibility is that accumulation of the promoting factor may be due to conversion to an as-yet-unidentified intermediate in which only a few of the 600 μ1N copies are initially released from any single particle (see below).

The transition to the regime in which promotion in trans operates is rather abrupt. This is evident both in the extent of inactivation at different concentrations (see Fig. 2A) and in the sharp end of the lag phase in time course experiments (see Fig. 4). This suggests that a certain threshold amount of promoting factor is required, perhaps to occupy a certain number of binding epitopes on the target ISVP. However, estimating the required amount is difficult. In some experiments in which ISVP* supernatant was used to promote conversion, such as in Fig. 3B, as little as 4 μl of supernatant was sufficient to promote conversion, equivalent to 120 copies of μ1N per target ISVP. However, in a similar type of experiment, Ivanovic et al. (22) found that only ≈40% of input μ1N is transferred after conversion and pelleting, and that pore-forming activity is lost rapidly if the preconversion reaction is not stopped shortly after conversion. In this study, we found that the promoting activity of preconverted ISVP*s is sensitive to timing as well; promoting activity was lost within 10 min if the preconversion reaction was allowed to remain at 52°C after conversion (data not shown). The μ1N peptide is hydrophobic and may be quickly removed from aqueous solution by adherence to the tube or aggregation. Thus, the actual amount of μ1N present and available in the promoting reactions is unknown.

It seems likely that the timing of the transition to second-order behavior represents a race between accumulation of released μ1N by initial first-order ISVP* conversion and sequestration by adherence or aggregation. When the initial ISVP concentration is too low, μ1N does not accumulate fast enough to reach the threshold concentration for promoting conversion in trans. However, above ≈1011 particles per milliliter, accumulation outpaces sequestration and in trans promotion proceeds.

Although the μ1N peptide is sufficient for conversion-promoting activity, supernatants from dpISVP* reactions were consistently less efficient than supernatants from ISVP* reactions (see Fig. 3D). In addition, after preconversion at 52°C, dpISVP* reactions lost promoting activity more rapidly than did ISVP* reactions (data not shown). These observations suggest that the C-terminal μ1 fragment φ (see Fig. 1) may contribute to promoting activity and are consistent with the μ1N-chaperoning activity for φ proposed by Ivanovic et al. (22).

Endosomal proteases are required for the generation of ISVPs in cells. However, low pH is not required for ISVP* conversion. The location of ISVP* conversion is not known, although the recently reported observation that released components mediate membrane-pore formation (22) suggests that an endosome or other bounded compartment may be required to maintain a sufficiently high concentration of released components. Factors that promote ISVP* conversion during cell entry are poorly understood, although temperature and K+ ions may play a role (12, 13, 23). Given the confined volume of an endocytic vesicle or a constricted membrane invagination, a single ISVP may be able to take advantage of the positive-feedback mechanism described here. This would require an initial, partial conversion of the single particle such that only a few of the 600 μ1N copies are slowly released. These peptides, being at a high concentration due to the confined volume, would then go on to promote full conversion and release of the remaining μ1N copies in a burst. The μ1N in this burst would then mediate membrane-pore formation (21, 22). To date, however, direct evidence for such partial conversion of single particles is lacking.

Another possibility is that conversion-promoting activity is not biologically relevant per se, but is the side effect of an interaction between μ1N and particles that serves another relevant purpose. For example, it has been recently shown that ISVP* particles can dock to pores formed by μ1N peptides (22), and it is possible that in trans promotion is an unintended consequence of this interaction, which is proposed to precede particle translocation across the membrane.

Many animal viruses, both enveloped and nonenveloped, follow a similar pathway for activation of the membrane-fusion or -penetration function of the capsid (36–39). First, a priming or deprotection step results in a metastable intermediate (e.g., proteolytic cleavage of influenza virus hemagglutinin, proteolytic removal of reovirus σ3). Second, a promoted conformational rearrangement leads to the exposure of membrane-interacting sequences. Many promoting factors have been reported, including receptor binding, low pH, cations, and heat. To our knowledge, however, a positive-feedback mechanism of promoting escape from the metastable intermediate has not been reported. The mechanism described here represents a generalizable device for sensing a confined volume, such as that encountered during cell entry.

Materials and Methods

Cells and Viruses.

Spinner-adapted mouse L929 cells and Spodoptera frugiperda clone 21 and Trichoplusia ni TN-BTI-564 (High Five) insect cells (Invitrogen) were grown as described (16). Virions of reovirus T1L or T3D were grown in spinner cultures of L929 cells, purified according to the standard protocol (5), and stored in virion buffer (VB) (150 mM NaCl, 20 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5) at 4°C. Purified cores for use in recoating were prepared as described (32), except that virions were digested with 250 μg/ml TLCK-treated α-CHT (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2–4 h. Nonpurified (21) and purified (22) ISVPs were made with CHT as described and used interchangeably. dpISVPs were made as described (34) or with a slightly modified protocol (22). T1L ISVPs were used in all experiments unless indicated otherwise. Recoated cores were made without σ1 (16), using baculovirus-expressed WT T1L σ3 and either WT T1L μ1 (32) or N42A T1L μ1 (20). ISVP-like particles (pRCs) were generated from recoated cores as described above for nonpurified ISVPs. All virus particles were dialyzed against VB before use, and particle concentrations were determined by A260 or SDS/PAGE.

Heat Inactivations.

ISVPs were diluted in VB, and samples were treated by immersing tubes in a preequilibrated water bath. For concentration curves as in Fig. 2A, 30-μl aliquots were treated for 15 min. Samples were titered by CHT-overlay plaque assay (15). Titers are expressed relative to an untreated sample held on ice. For time courses such as for Fig. 2B, 5-μl aliquots in thin-walled tubes were treated for the indicated times, then removed to an ice bath. Samples were titered by CHT-overlay plaque assay. Time to 99% reduction in titer (t99%) was determined from a line between two points (t, 1/titer) bracketing 1/titer = 100/titer0 (see the legend for Fig. S1), because these are expected to be linear according to the rate equation for second-order reactions, −d[C]/dt = k[C]2, where t is time, [C] is concentration, and k is the rate constant. Essentially identical results were obtained by using a line between two points (t,log[titer]) bracketing log[titer] = log[titer0] − 2 (data not shown).

Hemolysis and ISVP*–Conversion Time Courses.

Bovine red blood cells (RBCs) (Colorado Serum) were washed in PBS containing 2 mM MgCl2 (PBS-Mg). Hemolysis time courses were performed with ISVPs in 70% VB, 10% PBS-Mg, 400 mM CsCl, and 3% (vol/vol) RBCs. Reactions (140-μl) were incubated at 37°C, and at each time point, 7-μl aliquots were removed and placed into 63 μl of cold PBS-Mg. Samples were centrifuged at 380 × g for 10 min to pellet unlysed cells, and hemoglobin release was measured by A405 of the supernatant. For time courses such as in Fig. 4 and Fig. S2, reactions contained ISVPs or pRCs in VB with 400 mM CsCl. Five-microliter aliquots in thin-walled tubes were incubated at 37°C for the indicated times, then removed to an ice bath and assayed for TRY sensitivity of μ1 as described below.

Assays for Promoting Activity.

All reactions were performed in VB. Promoting activity of ISVP* conversion products was tested by incubating a 1:1 mixture of T1L and T3D ISVPs in 10 μl at 37°C for 65 min. Reactions contained a final total ISVP concentration of 5 × 1012 particles per milliliter. Alternatively, 5 μl of ISVPs at 5 × 1012 particles per milliliter were preconverted at either 52 or 53°C and chilled on ice for ≈1 min. Five microliters of target ISVPs at 5 × 1012 particles per milliliter were added to the same tube, and the reaction was incubated at 37°C for an additional 60 min. Under these conditions, conversion of the target ISVPs was essentially complete by 5 min (data not shown). Duration of the preconversion step varied between particle preparations. Promoting activity is acquired with the onset of ISVP* conversion, but is rapidly lost if the preconversion step is too long (data not shown). Duration of the preconversion was determined empirically for each preparation and was typically 2–5 min. Temperature curves as in Fig. 5 were performed as above, except that after the addition of target ISVPs, reactions were incubated at the indicated temperature for 15 min. The percentage of protease-resistant δ was calculated relative to a sample containing identical components but incubated on ice.

Promoting activity of released components was tested by preconverting 20–25 μl of ISVPs at 5 × 1012 particles per milliliter at 52°C, centrifuging at 16,000 × g for 10 min to pellet particles, and transferring the indicated volume of supernatant to a tube containing target ISVPs. This tube was then incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Reactions contained 1 × 1011 target ISVPs in a total volume of 20 μl. In these experiments, preconversion was stopped within 30 sec of conversion, and supernatant was transferred immediately after centrifugation. In addition, siliconized low-retention microtubes (Fisher Scientific) were used for all steps.

Experiments with Synthetic μ1N.

A peptide comprising amino acid 2–42 of T1L μ1 and an N-terminal N-myristoyl group was synthesized in vitro as will be described (L. Zhang, D. King, and S. C. Harrison, personal communication). Purified peptide was dissolved in 100% DMSO, and an intermediate dilution in 25% DMSO was made immediately before use. Promoting reactions contained 4 × 1012 ISVPs per milliliter and 50 μg/ml peptide in VB with 1% DMSO, and were assembled in siliconized, low-retention microtubes. Reactions were incubated at 37°C for 60 min.

TRY-Sensitivity Assay.

Samples were assayed for μ1 conformational change by incubation with 100 μg/ml TRY (Sigma-Aldrich) on ice for 45 min, then boiling in Laemmli sample buffer and subjection to SDS/PAGE as described (34). Proteins were visualized by staining with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 (Sigma–Aldrich).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank S. C. Harrison and L. Zhang (Harvard Medical School, Boston) for the gift of synthetic μ1N peptide; E. C. Freimont for technical assistance; and K. Chandran, S. C. Harrison, and L. Zhang for discussions and comments on the manuscript. The research was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 AI46440 (to M.L.N.) and F31 AI064142 (to M.A.A.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0802039105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Nibert ML, Schiff LA, Fields BN. Mammalian reoviruses contain a myristoylated structural protein. J Virol. 1991;65:1960–1967. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.4.1960-1967.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tillotson L, Shatkin AJ. Reovirus polypeptide σ3 and N-terminal myristoylation of polypeptide μ1 are required for site-specific cleavage to μ1C in transfected cells. J Virol. 1992;66:2180–2186. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.2180-2186.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dryden KA, et al. Early steps in reovirus infection are associated with dramatic changes in supramolecular structure and protein conformation: Analysis of virions and subviral particles by cryoelectron microscopy and image reconstruction. J Cell Biol. 1993;122:1023–1041. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.5.1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liemann S, Chandran K, Baker TS, Nibert ML, Harrison SC. Structure of the reovirus membrane-penetration protein, μ1, in a complex with is protector protein, σ3. Cell. 2002;108:283–295. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00612-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Furlong DB, Nibert ML, Fields BN. Sigma 1 protein of mammalian reoviruses extends from the surfaces of viral particles. J Virol. 1988;62:246–256. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.1.246-256.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chappell JD, Prota AE, Dermody TS, Stehle T. Crystal structure of reovirus attachment protein σ1 reveals evolutionary relationship to adenovirus fiber. EMBO J. 2002;21:1–11. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sturzenbecker LJ, Nibert M, Furlong D, Fields BN. Intracellular digestion of reovirus particles requires a low pH and is an essential step in the viral infectious cycle. J Virol. 1987;61:2351–2361. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.8.2351-2361.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bodkin DK, Nibert ML, Fields BN. Proteolytic digestion of reovirus in the intestinal lumens of neonatal mice. J Virol. 1989;63:4676–4681. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.11.4676-4681.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nibert ML, Fields BN. A carboxy-terminal fragment of protein μ1/μ1C is present in infectious subvirion particles of mammalian reoviruses and is proposed to have a role in penetration. J Virol. 1992;66:6408–6418. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.11.6408-6418.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joklik WK. Studies on the effect of chymotrypsin on reovirions. Virology. 1972;49:700–715. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(72)90527-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borsa J, Copps TP, Sargent MD, Long DG, Chapman JD. New intermediate subviral particles in the in vitro uncoating of reovirus virions by chymotrypsin. J Virol. 1973;11:552–564. doi: 10.1128/jvi.11.4.552-564.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chandran K, Farsetta DL, Nibert ML. Strategy for nonenveloped virus entry: A hydrophobic conformer of the reovirus membrane penetration protein μ1 mediates membrane disruption. J Virol. 2002;76:9920–9933. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.19.9920-9933.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Middleton JK, Severson TF, Chandran K, Gillian AL, Yin J, Nibert ML. Thermostability of reovirus disassembly intermediates (ISVPs) correlates with genetic, biochemical, and thermodynamic properties of major surface protein μ1. J Virol. 2002;76:1051–1061. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.3.1051-1061.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chandran K, Parker JSL, Ehrlich M, Kirchhausen T, Nibert ML. The δ region of outer-capsid protein μ1 undergoes conformational change and release from reovirus particles during cell entry. J Virol. 2003;77:13361–13375. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.24.13361-13375.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Middleton JK, Agosto MA, Severson TF, Yin J, Nibert ML. Thermostabilizing mutations in reovirus outer-capsid protein μ1 selected by heat inactivation of infectious subvirion particles. Virology. 2007;361:412–425. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agosto MA, Middleton JK, Freimont EC, Yin J, Nibert ML. Thermolabilizing pseudoreversions in reovirus outer-capsid protein μ1 rescue the entry defect conferred by a thermostabilizing mutation. J Virol. 2007;81:7400–7409. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02720-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borsa J, Long DG, Sargent MD, Copps TP, Chapman JD. Reovirus transcriptase activation in vitro: Involvement of an endogenous uncoating activity in the second stage of the process. Intervirology. 1974;4:171–188. doi: 10.1159/000149856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nibert ML, Odegard AL, Agosto MA, Chandran K, Schiff LA. Putative autocleavage of reovirus μ1 protein in concert with outer-capsid disassembly and activation for membrane permeabilization. J Mol Biol. 2005;345:461–474. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang X, et al. Features of reovirus outer capsid protein μ1 revealed by electron cryomicroscopy and image reconstruction of the virion at 7.0-Å resolution. Structure. 2005;13:1545–1557. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Odegard AL, Chandran K, Zhang X, Parker JSL, Baker TS, Nibert ML. Putative autocleavage of outer capsid protein μ1, allowing release of myristoylated peptide μ1N during particle uncoating, is critical for cell entry by reovirus. J Virol. 2004;78:8732–8745. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.16.8732-8745.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agosto MA, Ivanovic T, Nibert ML. Mammalian reovirus, a nonfusogenic nonenveloped virus, forms size-selective pores in a model membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:16496–16501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605835103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ivanovic T, Agosto MA, Zhang L, Chandran K, Harrison SC, Nibert ML. Peptides released from reovirus outer capsid form membrane pores. EMBO J. 2008;27:1289–1298. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Borsa J, Sargent MD, Long DG, Chapman JD. Extraordinary effects of specific monovalent cations on activation of reovirus transcriptase by chymotrypsin in vitro. J Virol. 1973;11:207–217. doi: 10.1128/jvi.11.2.207-217.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lonberg-Holm K, Gosser LB, Shimshick EJ. Interaction of liposomes with subviral particles of poliovirus type 2 and rhinovirus type 2. J Virol. 1976;19:746–749. doi: 10.1128/jvi.19.2.746-749.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wharton SA, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Studies of influenza haemagglutinin-mediated membrane fusion. Virology. 1986;149:27–35. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(86)90083-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wetz K, Kucinski T. Influence of different ionic and pH environments on structural alterations of poliovirus and their possible relation to virus uncoating. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:2541–2544. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-10-2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Curry S, Chow M, Hogle JM. The poliovirus 135S particle is infectious. J Virol. 1996;70:7125–7131. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.7125-7131.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carr CM, Chaudhry C, Kim PS. Influenza hemagglutinin is spring-loaded by a metastable native conformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14306–14313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wharton SA, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Temperature dependence of fusion by sendai virus. Virology. 2000;271:71–78. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wiethoff CM, Wodrich H, Gerace L, Nemerow GR. Adenovirus protein VI mediates membrane disruption following capsid disassembly. J Virol. 2005;79:1992–2000. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.4.1992-2000.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borsa J, Long DG, Copps TP, Sargent MD, Chapman JD. Reovirus transcriptase activation in vitro: Further studies on the facilitation phenomenon. Intervirology. 1974;3:15–35. doi: 10.1159/000149739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chandran K, et al. In vitro recoating of reovirus cores with baculovirus-expressed outer-capsid proteins μ1 and σ3. J Virol. 1999;73:3941–3950. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.3941-3950.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chandran K, et al. Complete in vitro assembly of the reovirus outer capsid produces highly infectious particles suitable for genetic studies of the receptor-binding protein. J Virol. 2001;75:5335–5342. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.11.5335-5342.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chandran K, Nibert ML. Protease cleavage of reovirus capsid protein μ1/μ1C is blocked by alkyl sulfate detergents, yielding a new type of infectious subvirion particle. J Virol. 1998;72:467–475. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.467-475.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Borsa J, Sargent MD, Oikawa K. Circular dichroism of intermediate subviral particles of reovirus. Elucidation of the mechanism underlying the specific monovalent cation effects on uncoating. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1976;451:619–627. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(76)90157-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Receptor binding and membrane fusion in virus entry: The influenza hemagglutinin. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:531–569. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hogle JM. Poliovirus cell entry: Common structural themes in viral cell entry pathways. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2002;56:677–702. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.56.012302.160757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chandran K, Nibert ML. Animal cell invasion by a large nonenveloped virus: Reovirus delivers the goods. Trends Microbiol. 2003;11:374–382. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(03)00178-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harrison SC. Mechanism of membrane fusion by viral envelope proteins. Adv Virus Res. 2005;64:231–261. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(05)64007-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.