Abstract

Trichoderma spp. are effective biocontrol agents for several soil-borne plant pathogens, and some are also known for their abilities to enhance systemic resistance to plant diseases and overall plant growth. Root colonization with Trichoderma harzianum Rifai strain 22 (T22) induces large changes in the proteome of shoots of maize (Zea mays) seedlings, even though T22 is present only on roots. We chose a proteomic approach to analyze those changes and identify pathways and genes that are involved in these processes. We used two-dimensional gel electrophoresis to identify proteins that are differentially expressed in response to colonization of maize plants with T22. Up- or down-regulated spots were subjected to tryptic digestion followed by identification using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization tandem time-of-flight mass spectrometry and nanospray ion-trap tandem mass spectrometry. We identified 91 out of 114 up-regulated and 30 out of 50 down-regulated proteins in the shoots. Classification of these revealed that a large portion of the up-regulated proteins are involved in carbohydrate metabolism and some were photosynthesis or stress related. Increased photosynthesis should have resulted in increased starch accumulation in seedlings and did indeed occur. In addition, numerous proteins induced in response to Trichoderma were those involved in stress and defense responses. Other processes that were up-regulated were amino acid metabolism, cell wall metabolism, and genetic information processing. Conversely, while the proteins involved in the pathways noted above were generally up-regulated, proteins involved in other processes such as secondary metabolism and protein biosynthesis were generally not affected. Up-regulation of carbohydrate metabolism and resistance responses may correspond to the enhanced growth response and induced resistance, respectively, conferred by the Trichoderma inoculation.

Trichoderma spp. have been known for decades to increase plant growth (both shoot and root biomass and crop yield; Lindsey and Baker, 1967; Chang et al., 1986; Harman, 2000), to increase plant nutrient uptake (Yedidia et al., 2001) and fertilizer utilization (Harman, 2000), to grow more rapidly, and to enhance plant greenness, which might result in higher photosynthetic rates (Harman, 2006). These same organisms also have been known for a very long time to have the ability to control plant pathogenic fungi (Weindling, 1932, 1941).

Recently, these fungi have been shown to be plant symbionts (Harman et al., 2004a). In this symbiotic process, they infect plant roots, but through chemical communication factors they induce the plant to wall off the invading Trichoderma hypha so that the organism is restricted to the outer layers of the root (Yedidia et al., 1999). In so doing, they induce localized resistance to plant pathogen attack, but beyond this, they induce systemic interactions within the plant. Thus, even though the Trichoderma spp. are restricted to roots, the foliage becomes resistant to plant diseases (Yedidia et al., 2000, 2003; Harman et al., 2004a). The basic physiology of the changes in plants introduced by Trichoderma spp. is beginning to be understood. For example, it appears that there are a wide range of chemical communication factors and that the particular response may be altered as these factors change. In many cases, these factors are extracellular proteins, or chemicals produced by action of these proteins, that are produced by Trichoderma spp. within plant cells (Hanson and Howell, 2001, 2004; Harman and Shoresh, 2007). In cucumber (Cucumis sativus), recent studies demonstrated that the main signal transduction pathway through which the Trichoderma-mediated induced systemic resistance is activated uses jasmonic acid and ethylene as signal molecules, and a similar system has been shown in maize (Zea mays; Djonovic et al., 2007). Moreover, Trichoderma interaction with plant roots creates a sensitized state in the plant allowing it to respond more efficiently to subsequent pathogenic attack. This sensitization is apparent from both the reduction in disease symptoms and the systemic potentiation of the expression of defense-related genes (Yedidia et al., 2003; Shoresh et al., 2005). A mitogen-activated protein kinase, necessary for the process, was also potentiated similarly (Shoresh et al., 2006). Recent proteomic studies also demonstrate the involvement of defense-related proteins in plants interacting with Trichoderma (Chen et al., 2005; Marra et al., 2006; Djonovic et al., 2007).

Trichoderma-treated plants were shown to have enhanced nutrient uptake, increased root and shoot growth, and improved plant vigor (Inbar et al., 1994; Yedidia et al., 2001; Harman et al., 2004a). While we are only beginning to reveal some of the mechanisms by which Trichoderma renders plants to be more resistant to pathogen attack, still little is known about the molecular basis underlying the mechanisms of Trichoderma-induced growth enhancement.

We hypothesized that this wide range of systemic phenotypic changes were reflected in very significant changes in the overall physiology and metabolism of the maize plant. If so, these changes should be reflected in a substantial alteration of the proteome of the plant. Finally, we expected that, by using knowledge about the function of the identified up- and down-regulated proteins, we could categorize the changes in the proteome and identify changes in entire metabolic pathways that are induced by Trichoderma harzianum Rifai strain 22 (T22).

This study was conducted to investigate changes in the proteome of seedlings of maize induced by a seed treatment, and subsequent root colonization, by T22. We were interested especially in characterizing the systemic changes in the young plants. Therefore, we determined changes in the proteomic pattern in leaves (T22 was absent in the tissues analyzed), assigned functions, and, in some cases, determined genes encoding the proteins. This information enabled us to study the changes in pathways induced by T22.

RESULTS

Overview of the Maize Proteome Changes Due to the Interaction with T22

Inoculation with T22 enhanced seedling growth. At 7 d after planting, average shoot length of control plants was 5.45 ± 0.36 cm and that of inoculated plants was 8.05 ± 0.28 cm (P = 1.199 × 10−7). T22 applied in this manner was earlier shown to consistently increase plant growth, and when large enough to test, the seedlings exhibited enhanced foliar resistance to Colletotrichum graminicola even though T22 was restricted to roots (Harman et al., 2004b).

To assess systemic changes in the maize proteome during interaction with Trichoderma T22, proteins were extracted from the leaves of 7-d-old maize seedlings grown from seeds treated with Trichoderma or with water as a control and used for two-dimensional SDS-PAGE (2-DE). In a preliminary 2-DE gel analysis with a pI range of 3 to 10, most of the proteins resided between pI 5.0 and 7.5. Therefore, the pI range was narrowed to lower the complexity of the protein spot pattern. Two overlapping pI ranges of 5.3 to 6.5 and 6.3 to 7.5 were used for the first dimension to obtain a better separation of the majority of the proteins (Supplemental Fig. S1).

The number of protein spots up-regulated in maize shoots of Trichoderma-inoculated plants was 117, while the number of down-regulated spots was 50. Most of the spots were picked and subjected to matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization tandem time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) for further identification. Spots producing no match by this method were reanalyzed by nanospray ion-trap tandem MS (nESI-IT MS). A total of 94 of the up-regulated protein spots were identified; only six were proteins of unknown function. Thirty spots of the down-regulated proteins were also identified, and five were proteins of unknown function.

Functional Categories of Identified Proteins

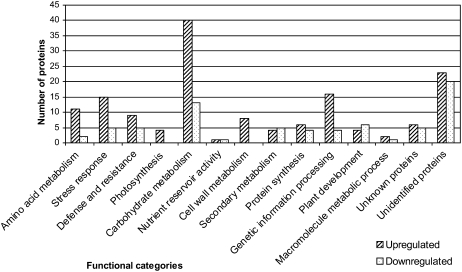

The proteins were divided into functional categories using DAVID Bioinformatics Resources (Dennis et al., 2003), Gene Ontology, and KEGG terms (Fig. 1). Proteins with molecular function involved in more than one biological process were assigned to more than one category. All identified proteins and the categories they were assigned to are listed in Table I (up-regulated proteins) and Table II (down-regulated proteins). The most numerous proteins with significant changes in quantities were those involved in carbohydrate metabolism. Forty proteins involved in carbohydrate or starch metabolism were up-regulated, while only 13 were down-regulated. This demonstrated that carbohydrate metabolism is modulated systemically due to Trichoderma colonization of maize roots. The identified proteins included fructokinase (three spots up-regulated), Fru bisphosphate aldolase (FBA; three spots up- and one down-regulated), glyceraldehyde-3-P dehydrogenase (GAPDH; 17 spots up- and six down-regulated), malate dehydrogenase (MDH; three spots up-regulated), cytosolic 3-phosphoglycerate kinase (one spot up-regulated), NADP-specific isocitrate dehydrogenase (one spot up-regulated), oxalate oxidase (one spot up- and one down-regulated), β-glucosidase (four spots up- and five down-regulated), Suc synthase (SUS; five spots up-regulated), UDP-Glc dehydrogenase (one spot up-regulated), and UDP-GlcUA decarboxylase (one spot up-regulated).

Figure 1.

Functional categories of identified proteins. Identified proteins were categorized into functional groups. Proteins involved in more than one process were assigned to more than one categorical group. The number of proteins in each categorical group is presented here. Up-regulated proteins are in hatched bars and down-regulated proteins are in stippled bars.

Table I.

Up-regulated proteins

The identified proteins are listed in the following table. This table lists the spot number (H, high pI range; L, low pI range), the in-gel and predicted pI and Mr, the averaged ratio between normalized quantities in treated (T) versus control (C) plants, P value (Student's t test) for the replicate groups, and the corresponding accession code (NCBI gi identifier). A protein CI percentage (%CI) of ≥95 is considered significant, i.e. there is a 5% or less chance that the match is due to random chance. In cases where liquid chromatography/MS/MS was used to identify the protein, the score and the number of peptides matched (in parentheses) are presented. The significant threshold for Mascot search was set to 0.05. Finally, the function description and the functional category are also presented.

| Spot No. | Mra | pIa | Ratio T/C | P (t Test) | Accession No. | Mrb | pIb | %CI | Function Description | Functional Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H6603 | 38,492 | 6.91 | 3.38 | 0.044 | 50919785 | 44,903 | 8.53 | 100 | Putative phospho-Ser aminotransferase (rice) | Amino acid metabolism |

| H5602 | 46,655 | 6.60 | 3.00 | 0.010 | 11762130 | 51,685 | 6.80 | 99.4 | Hydroxymethyltransferase (Arabidopsis) | Amino acid metabolism |

| L0408 | 25,805 | 5.30 | 2.35 | 0.020 | 17017263 | 84,400 | 5.73 | 100 | Met synthase (maize) | Amino acid metabolism, stress response |

| L2409 | 25,074 | 5.45 | 4.58 | 0.017 | 50897038 | 84,452 | 5.68 | 99.93 | Met synthase (barley) | Amino acid metabolism, stress response |

| L2808 | 42,775 | 5.45 | 2.32 | 0.002 | 17017263 | 84,400 | 5.73 | 100 | Met synthase (maize) | Amino acid metabolism, stress response |

| L3802 | 46,101 | 5.56 | 14.90 | 0.030 | 17017263 | 84,400 | 5.73 | 100 | Met synthase (maize) | Amino acid metabolism, stress response |

| L4410 | 26,893 | 5.61 | 4.65 | 0.013 | 17017263 | 84,400 | 5.73 | 100 | Met synthase (maize) | Amino acid metabolism, stress response |

| L4811 | 44,129 | 5.63 | 3.27 | 0.025 | 17017263 | 84,400 | 5.73 | 182 (5) | Met synthase (maize) | Amino acid metabolism, stress response |

| L0605 | 32,356 | 5.30 | 3.40 | 0.012 | 1814403 | 84,769 | 5.90 | 100 | Met synthase (Mesembryanthemum crystallinum) | Amino acid metabolism, stress response |

| L0804 | 43,500 | 5.30 | 9.44 | 0.030 | 17017263 | 84,400 | 5.73 | 100 | Met synthase (maize) | Amino acid metabolism, stress response |

| L2604 | 33,839 | 5.49 | 2.78 | 0.025 | 50915796 | 53,473 | 6.24 | 100 | Glutathione reductase (rice) | Amino-acid metabolism |

| L0705 | 36,714 | 5.30 | 2.88 | 0.025 | 31652276 | 35,459 | 5.34 | 100 | FRK2 (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| L2708 | 36,291 | 5.41 | 1.89 | 0.018 | 31652276 | 35,459 | 5.34 | 100 | FRK2 (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| L6602 | 31,068 | 5.92 | 3.84 | 0.033 | 31652276 | 35,459 | 5.34 | 99.6 | FRK2 (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| L1104 | 14,726 | 5.35 | 6.65 | 0.030 | 295850 | 38,580 | 7.52 | 100 | FBA (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| L6505 | 29,420 | 5.90 | 2.07 | 0.003 | 295850 | 38,580 | 7.52 | 100 | FBA (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| L5206 | 16,501 | 5.71 | 2.27 | 0.037 | 295850 | 38,580 | 7.52 | 100 | FBA (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| H1503 | 36,436 | 6.32 | 2.33 | 0.013 | 120680 | 36,491 | 6.67 | 99.86 | GADPH, cytosolic: Gpc1 (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| H4512 | 37,325 | 6.56 | 1.50 | 0.029 | 295853 | 36,500 | 6.46 | 100 | GADPH, cytosolic: Gpc1 (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| H5502 | 37,381 | 6.59 | 2.70 | 0.000 | 295853 | 36,500 | 6.46 | 99.97 | GADPH, cytosolic: Gpc1 (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| L4609 | 34,478 | 5.64 | 45.00 | 0.004 | 295853 | 36,500 | 6.46 | 100 | GADPH, cytosolic: Gpc1 (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| L5705 | 35,294 | 5.79 | 1.97 | 0.050 | 295853 | 36,500 | 6.46 | 100 | GADPH, cytosolic: Gpc1 (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| L7701 | 36,277 | 6.00 | 2.71 | 0.006 | 295853 | 36,500 | 6.46 | 100 | GADPH, cytosolic: Gpc1 (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| L8602 | 31,273 | 6.28 | 3.45 | 0.001 | 295853 | 36,500 | 6.46 | 99.13 | GADPH, cytosolic: Gpc1 (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| L9703 | 38,270 | 6.37 | 5.20 | 0.035 | 295853 | 36,500 | 6.46 | 100 | GADPH, cytosolic: Gpc1 (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| L9706 | 39,594 | 6.47 | 5.80 | 0.020 | 295853 | 36,500 | 6.46 | 100 | GADPH, cytosolic: Gpc1 (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| L9701 | 38,501 | 6.34 | 2.40 | 0.035 | 295853 | 36,500 | 6.46 | 100 | GADPH, cytosolic: Gpc1 (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| L2705 | 35,379 | 5.46 | 4.13 | 0.009 | 312179 | 36,519 | 6.41 | 100 | GADPH, cytosolic: Gpc2 (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| L3704 | 36,415 | 5.58 | 2.56 | 0.030 | 312179 | 36,519 | 6.41 | 100 | GADPH, cytosolic: Gpc2 (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| L5701 | 36,464 | 5.71 | 1.89 | 0.000 | 312179 | 36,519 | 6.41 | 99.98 | GADPH, cytosolic: Gpc2 (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| L7702 | 38,401 | 6.05 | 2.53 | 0.029 | 312179 | 36,519 | 6.41 | 100 | GADPH, cytosolic: Gpc2 (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| L8605 | 32,241 | 6.25 | 2.60 | 0.025 | 312179 | 36,519 | 6.41 | 100 | GADPH, cytosolic: Gpc2 (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| L8702 | 39,267 | 6.29 | 2.40 | 0.020 | 312179 | 36,519 | 6.41 | 100 | GADPH, cytosolic: Gpc2 (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| H6307 | 25,215 | 6.74 | 4.83 | 0.036 | 115450493 | 47,081 | 6.22 | 97.55 | GADPH, GapA (rice) | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| H8306 | 25,042 | 7.23 | 1.93 | 0.006 | 18202485 | 35,567 | 5.77 | 100 | MDH, cytoplasmic (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| L8411 | 25,585 | 6.31 | 9.90 | 0.040 | 2286153 | 35,567 | 5.77 | 205 (5) | MDH, cytoplasmic (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| L2606 | 31,129 | 5.45 | 2.28 | 0.009 | 2286153 | 35,567 | 5.77 | 97 | MDH, cytoplasmic (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| L8405 | 26,287 | 6.19 | 2.97 | 0.000 | 28172917 | 31,606 | 5.01 | 100 | Cytosolic 3-phosphoglycerate kinase (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| L8801 | 48,253 | 6.13 | 3.60 | 0.005 | 31339162 | 55,041 | 8.28 | 98.05 | NADP-specific isocitrate dehydrogenase (Lupinus albus) | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| L1902 | 119,408 | 5.34 | 1.86 | 0.047 | 50917907 | 24,288 | 5.93 | 100 | Putative oxalate oxidase (rice) | Carbohydrate metabolism an nutrient reservoir activity and environmental stress response |

| L2907 | 62,271 | 5.49 | 3.00 | 0.018 | 435313 | 64,210 | 6.23 | 100 | β-Glucosidase (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism, defense against pest signaling (hormone activation) |

| L6805 | 53,076 | 5.84 | 10.30 | 0.001 | 435313 | 64,210 | 6.23 | 99.96 | β-Glucosidase (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism, defense against pest signaling (hormone activation) |

| L6304 | 24,240 | 5.88 | 3.80 | 0.001 | 435313 | 64,210 | 6.23 | 100 | β-Glucosidase (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism, defense against pest signaling (hormone activation) |

| L0917 | 65,318 | 5.30 | 1.96 | 0.017 | 435313 | 64,210 | 6.23 | 100 | β-Glucosidase (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism, defense against pest signaling (hormone activation) |

| L1302 | 22,154 | 5.38 | 87.30 | 0.012 | 1351136 | 92,880 | 6.03 | 100 | SUS2 (Suc-UDP glucosyltransferase 2) (sus1 gene product) (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism, cell wall and glycoprotein, and starch biosynthesis |

| L1303 | 20,154 | 5.38 | 3.07 | 0.015 | 741983 | 86,287 | 6.87 | 100 | SUS2 (sus1 gene product) (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism, cell wall and glycoprotein, and starch biosynthesis |

| L1307 | 20,723 | 5.37 | 1.83 | 0.014 | 741983 | 86,287 | 6.87 | 100 | SUS2 (sus1 gene product) (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism, cell wall and glycoprotein, and starch biosynthesis |

| L3301 | 22,141 | 5.53 | 4.12 | 0.004 | 741983 | 86,287 | 6.87 | 100 | SUS2 (sus1 gene product) (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism, cell wall and glycoprotein, and starch biosynthesis |

| L7406 | 25,735 | 6.09 | 5.14 | 0.015 | 459895 | 92,866 | 6.03 | 100 | SUS2 (sus1 gene product) (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism, cell wall and glycoprotein, and starch biosynthesis |

| H7603 | 38,168 | 7.05 | 3.40 | 0.034 | 18447934, 108707479 | 39,284 | 7.16 | 100 | UDP-GlcUA decarboxylase RmlD substrate-binding domain-containing protein (rice) | Carbohydrate metabolism, cell wall metabolism |

| H8504 | 36,143 | 7.30 | 6.30 | 0.040 | 50916735 | 52,264 | 5.75 | 100 | UDP-Glc dehydrogenase (rice) | Carbohydrate metabolism, energy metabolism, cell wall metabolism |

| L6402 | 26,140 | 5.83 | 1.77 | 0.024 | 2218152 | 39,397 | 6.24 | 100 | Type IIIa membrane protein cp-wap-13 (cowpea) | Cell wall biosynthesis |

| L5606 | 31,770 | 5.77 | 2.96 | 0.035 | 31430906 | 58,168 | 8.87 | 99.22 | Putative transposase (rice) | DNA metabolism, recombination |

| L9207 | 17,088 | 6.35 | 3.10 | 0.035 | 31432773 | 77,156 | 8.74 | 99.99 | Putative gag-pol precursor (rice) | DNA metabolism, recombination |

| L4709 | 38,395 | 5.62 | 2.10 | 0.009 | 22654997 | 152,719 | 5.98 | 99.99 | DNA repair-recombination protein (RAD50) (Arabidopsis) | DNA metabolism, response to stress and stimulus |

| L2802 | 47,355 | 5.41 | 1.98 | 0.025 | 32490293 | 37,342 | 9.43 | 99.94 | OSJNBa0057M08.27 probable nuclear protein similar to BRUSHY (rice) | Genetic information processing |

| L4704 | 35,725 | 5.66 | 2.93 | 0.001 | 32490293 | 37,342 | 9.43 | 99.93 | OSJNBa0057M08.27 probable nuclear protein similar to BRUSHY (rice) | Genetic information processing |

| L5508 | 30,241 | 5.79 | 2.06 | 0.031 | 32490293 | 37,342 | 9.43 | 99.87 | OSJNBa0057M08.27 probable nuclear protein similar to BRUSHY (rice) | Genetic information processing |

| L6702 | 39,628 | 5.91 | 4.20 | 0.024 | 32490293 | 37,342 | 9.43 | 99.91 | OSJNBa0057M08.27 probable nuclear protein similar to BRUSHY (rice) | Genetic information processing |

| L7501 | 29,190 | 5.95 | 7.30 | 0.008 | 32490293 | 37,342 | 9.43 | 99.91 | OSJNBa0057M08.27 probable nuclear protein similar to BRUSHY (rice) | Genetic information processing |

| L9603 | 33,337 | 6.35 | 3.93 | 0.025 | 32490293 | 37,342 | 9.43 | 100 | OSJNBa0057M08.27 probable nuclear protein similar to BRUSHY (rice) | Genetic information processing |

| L9802 | 42,295 | 6.35 | 1.77 | 0.045 | 32490293 | 37,342 | 9.43 | 99.98 | OSJNBa0057M08.27 probable nuclear protein similar to BRUSHY (rice) | Genetic information processing |

| L2512 | 26,561 | 5.52 | 1.51 | 0.000 | 32490293 | 37,342 | 9.43 | 99.97 | OSJNBa0057M08.27 probable nuclear protein similar to BRUSHY (rice) | Genetic information processing |

| L7508 | 27,501 | 6.05 | 3.50 | 0.030 | 34897382 | 97,309 | 9.34 | 99.93 | Putative RNA-binding protein (rice) | Genetic information processing |

| L4601 | 33,326 | 5.60 | 2.36 | 0.006 | 9843653 | 35,135 | 11.54 | 99.98 | Splicing factor SC35 (Arabidopsis) | Genetic information processing (splicing) |

| L6407 | 26,999 | 5.92 | 3.37 | 0.045 | 9294425 | 36,439 | 9.08 | 99.64 | Unnamed protein similar to FCP1-like phosphatase (Arabidopsis) | Genetic information processing (transcription regulation) |

| L3508 | 28,842 | 5.58 | 2.16 | 0.005 | 21554280 | 24,286 | 9.56 | 99.99 | RNA polymerase I, II, and III 24.3-kD subunit (Arabidopsis) | Genetic information processing (transcription) |

| L2607 | 32,308 | 5.44 | 3.50 | 0.075 | 34905088 | 33,233 | 9.38 | 99.98 | Hypothetical protein (contains BTB/POZ domain) (rice) | Genetic information processing (transcription regulation) |

| L2608 | 32,183 | 5.40 | 15.40 | 0.001 | 3860254 | 42,284 | 9.88 | 99.88 | Hypothetical protein (At) contains 95% similar to Golgi GDP Man transporter (GONST1) (Arabidopsis) | Macromolecule metabolic process (protein and lipid glycosylation) |

| L7703 | 37,290 | 6.11 | 5.70 | 0.009 | 4558668 | 44,436 | 10.01 | 99.77 | Golgi GDP Man transporter (GONST1) (Arabidopsis) | Macromolecule metabolic process (protein and lipid glycosylation) |

| H3202 | 20,416 | 6.46 | 2.36 | 0.039 | 21667030 | 49,228 | 6.23 | 87 (3) | Rubisco large subunit (Schoenocephalium cucullatum) | Photosynthesis |

| H3207 | 19,601 | 6.49 | 4.93 | 0.020 | 30313565 | 17,630 | 6.47 | 138 (2) | Rubisco large (Leptolaena multiflora) | Photosynthesis |

| H4102 | 19,234 | 6.51 | 3.09 | 0.033 | 168137 | 52,098 | 6.22 | 100 | Rubisco large subunit (Chamerion angustifolium) | Photosynthesis |

| H4210 | 23,402 | 6.58 | 27.08 | 0.009 | 20617 | 28,030 | 8.28 | 106 (2) | PSII oxygen-evolving complex protein 2 (Pisum sativum) | Photosynthesis |

| L1308 | 19,567 | 5.32 | 3.40 | 0.035 | 17104643 | 14,222 | 10.92 | 98.34 | Putative 60s ribosomal protein L35 (Arabidopsis) | Protein synthesis |

| L2509 | 27,997 | 5.40 | 3.38 | 0.025 | 3355475 | 17,430 | 10.20 | 99.34 | 60s ribosomal protein L23A (Arabidopsis) | Protein synthesis |

| L7405 | 25,890 | 6.04 | 2.10 | 0.035 | 303853 | 44,436 | 10.10 | 99.62 | Ribosomal protein L3 (rice) | Protein synthesis |

| L9208 | 17,600 | 6.50 | 2.71 | 0.070 | 33589770 | 14,322 | 10.92 | 99.86 | 60s ribosomal L29 protein (Arabidopsis) | Protein synthesis |

| L6507 | 28,160 | 5.93 | 1.87 | 0.019 | 27362885 | 20,425 | 6.93 | 99.98 | HSP70 (Populus alba) | Protein synthesis, stress response |

| H5412 | 27,385 | 6.61 | 11.53 | 0.003 | 15232682 | 71,103 | 4.97 | 99.47 | ATP-binding HSP70 (Arabidopsis) | Protein synthesis, stress response |

| H4211 | 22,708 | 6.60 | 13.00 | 0.008 | 1345583 | 45,986 | 6.12 | 110 (3) | PAL (Vitis vinifera) | Resistance response |

| L4303 | 19,163 | 5.62 | 2.00 | 0.008 | 15487869 | 20,108 | 9.66 | 98.74 | NBS/LRR resistance protein-like protein (Theobroma cacao) | Resistance response |

| L4807 | 60,407 | 5.62 | 2.07 | 0.026 | 15487977 | 19,924 | 9.61 | 99.79 | NSB/LRR resistance protein-like protein (T. cacao) | Resistance response |

| L6502 | 29,854 | 5.85 | 3.04 | 0.011 | 15487869 | 20,108 | 9.66 | 99.79 | NBS/LRR resistance protein-like protein (T. cacao) | Resistance response |

| L6705 | 36,058 | 5.85 | 6.20 | 0.001 | 15487869 | 20,108 | 9.66 | 99.48 | NSB/LRR resistance protein-like protein (T. cacao) | Resistance response |

| H2209 | 22,101 | 6.40 | 8.00 | 0.040 | 1841502 | 40,745 | 6.37 | 104 (2) | Glutathione-dependent FALDH (maize) | Stress response |

| L7601 | 32,793 | 5.96 | 3.27 | 0.008 | 57635155 | 27,534 | 5.75 | 99.99 | Peroxidase 5 (Triticum monococcum) | Stress response |

| L7403 | 25,129 | 5.95 | 5.68 | 0.035 | 4468794 | 23,866 | 5.96 | 100 | Glutathione transferase III(b) (maize) | Stress response |

| H8607 | 48,368 | 7.38 | 30.00 | 0.007 | 49533764 | 50,434 | 6.37 | 99.10 | Putative TPR domain-containing protein (Solanum demissum) | Protein-protein interaction, function unknown |

| L7704 | 35,745 | 6.05 | 2.03 | 0.004 | 53749463 | 61,201 | 8.19 | 100 | Putative TPR domain-containing protein (S. demissum) | Protein-protein interaction, function unknown |

| L7510 | 27,581 | 5.94 | 42.00 | 0.030 | 50943489 | 26,568 | 11.59 | 97.76 | Hypothetical protein (rice) | Unknown |

| L7705 | 38,514 | 5.96 | 2.67 | 0.006 | 53792310 | 32,795 | 11.43 | 99.99 | Hypothetical protein (rice) | Unknown |

| L8705 | 38,841 | 6.12 | 4.80 | 0.020 | 49617779 | 16,493 | 9.96 | 98.09 | Hypothetical protein At3g57440 (Arabidopsis) | Unknown |

| L3702 | 35,887 | 5.57 | 6.20 | 0.085 | 57900012 | 8,376 | 9.49 | 99.98 | Hypothetical protein (rice) | Unknown |

| L1507 | 28,259 | 5.32 | 1.58 | 0.019 | No data | |||||

| L4301 | 19,863 | 5.64 | 3.83 | 0.050 | No data | |||||

| L5706 | 35,462 | 5.72 | 51.00 | 0.002 | No data | |||||

| L0307 | 20,833 | 5.30 | 3.18 | 0.033 | No data | |||||

| L5704 | 38,043 | 5.76 | 2.18 | 0.014 | No data | |||||

| L7309 | 22,858 | 5.96 | 2.33 | 0.012 | No data | |||||

| L7515 | 26,858 | 5.97 | 3.75 | 0.040 | No data |

In-gel pI and Mr.

Predicted pI and Mr.

Table II.

Down-regulated proteins

The identified proteins are listed in the following table. This table lists the spot number (H, high pI range; L, low pI range), the in-gel and predicted pI and Mr, the averaged ratio between normalized quantities in treated (T) versus control (C) plants, P value (Student's t test) for the replicate groups, and the corresponding accession code (NCBI gi identifier). A protein %CI of ≥95 is considered statistically significant, i.e. there is a 5% or less chance that the match is due to random chance. In cases where liquid chromatography/MS/MS was used to identify the protein, the score and the number of peptides matched (in parentheses) are presented. The significant threshold for Mascot search was set to 0.05. Finally, the function description and the functional category are also presented.

| Spot No. | Mra | pIa | Ratio T/C | P (t Test) | Accession No. | Mrb | pIb | %CI | Function Description | Functional Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L4413 | 26,834 | 5.60 | 0.58 | 0.043 | 17017263 | 84,400 | 5.73 | 99.99 | Met synthase (maize) | Amino acid metabolism, stress response |

| L1107 | 14,231 | 5.35 | 0.28 | 0.000 | 34911874 | 62,777 | 6.22 | 100.00 | Putative ketol-acid reductoisomerase (rice) | Amino acid metabolism |

| H5504 | 36,258 | 6.65 | 0.27 | 0.022 | 22238, 295853 | 36,500 | 6.46 | 100.00 | GADPH, cytosolic: Gpc1 (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| H3501 | 35,360 | 6.43 | 0.38 | 0.013 | 312179 | 36,519 | 6.41 | 100.00 | GADPH, cytosolic: Gpc2 (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| H3606 | 40,371 | 6.51 | 0.15 | 0.040 | 6016075 | 36,519 | 6.41 | 100.00 | GADPH, cytosolic: Gpc2 (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| H5506 | 35,966 | 6.71 | 0.34 | 0.000 | 6166167 | 36,426 | 7.01 | 94.76 | GADPH, cytosolic: Gpc3 (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| L5510 | 27,312 | 5.75 | 0.49 | 0.001 | 293887 | 24,930 | 8.44 | 99.93 | GADPH, cytosolic: Gpc3 (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| H4514 | 34,980 | 6.56 | 0.48 | 0.028 | 1184776 | 36,428 | 6.61 | 96.94 | GADPH, cytosolic: Gpc4 (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| L7105 | 14,967 | 5.96 | 0.57 | 0.024 | 295850 | 38,580 | 7.52 | 97.86 | FBA (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| L2905 | 103,294 | 5.44 | 0.15 | 0.000 | 8118443Zm.66876 | 24,288 | 5.93 | 77 (3) | Germin-like protein 2, oxalate oxidase (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism and nutrient reservoir activity and environmental stress response |

| L0908 | 66,070 | 5.30 | 0.37 | 0.000 | 435313 | 64,210 | 6.23 | 900 (32) | β-Glucosidase (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism, defense against pest signaling (hormone activation) |

| L3308 | 21,803 | 5.49 | 0.38 | 0.001 | 13399869 | 58,371 | 5.52 | 372 (10) | β-Glucosidase, chain B(Zmglu1) (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism, defense against pest signaling (hormone activation) |

| L3701 | 38,882 | 5.52 | 0.15 | 0.000 | 13399869 | 58,371 | 5.52 | 579 (21) | β-Glucosidase, chain B(Zmglu1) (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism, defense against pest signaling (hormone activation) |

| L6301 | 22,914 | 5.82 | 0.27 | 0.036 | 435313 | 64,210 | 6.23 | 100.00 | β-Glucosidase (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism, defense against pest signaling (hormone activation) |

| L6307 | 22,002 | 5.82 | 0.40 | 0.016 | 13399869 | 58,371 | 5.52 | 100.00 | β-Glucosidase, chain B(Zmglu1) (maize) | Carbohydrate metabolism, defense against pest signaling (hormone activation) |

| L2203 | 16,944 | 5.44 | 0.24 | 0.002 | 32490293 | 37,342 | 9.43 | 100.00 | OSJNBa0057M08.27 probable nuclear protein similar to BRUSHY (rice) | Genetic information processing |

| L6806 | 50,267 | 5.85 | 0.42 | 0.001 | 32490293 | 37,342 | 9.43 | 99.97 | OSJNBa0057M08.27 probable nuclear protein similar to BRUSHY (rice) | Genetic information processing |

| L7407 | 26,797 | 6.00 | 0.47 | 0.022 | 32490293 | 37,342 | 9.43 | 97.71 | OSJNBa0057M08.27 probable nuclear protein similar to BRUSHY (rice) | Genetic information processing |

| L7411 | 24,946 | 6.05 | 0.47 | 0.014 | 32490293 | 37,342 | 9.43 | 97.37 | OSJNBa0057M08.27 probable nuclear protein similar to BRUSHY (rice) | Genetic information processing |

| L7514 | 29,992 | 5.95 | 0.57 | 0.026 | 3860254 | 42,284 | 9.88 | 98.59 | Hypothetical protein (At), 95% similar to Golgi GDP Man transporter (GONST1) (Arabidopsis) | Macromolecule metabolic process (protein and lipid glycosylation) |

| L8202 | 17,467 | 6.16 | 0.05 | 0.000 | 56784250 | 8,591 | 10.06 | 99.15 | Unknown protein, DVL-like (rice) | Plant development |

| L7413 | 25,521 | 5.99 | 0.34 | 0.004 | 50948123 | 28,968 | 10.05 | 99.21 | Putative 60s ribosomal protein L7 (rice) | Protein synthesis |

| H6301 | 27,368 | 6.78 | 0.03 | 0.019 | 92868673 | 22,803 | 6.62 | 100.00 | HSP70 (Medicago truncatula) | Protein synthesis, stress response |

| L4105 | 14,909 | 5.63 | 0.41 | 0.039 | 2642648 | 71,448 | 5.09 | 100.00 | Cytosolic heat shock 70 protein HSC70-3 (Spinacia oleracea) | Protein synthesis, stress response |

| L3307 | 22,696 | 5.56 | 0.28 | 0.001 | 1181673 | 22,480 | 7.77 | 100.00 | HSP cognate 70 (Sorghum bicolor) | Protein synthesis, stress response |

| L8505 | 28,059 | 6.32 | 0.46 | 0.000 | 53749463 | 61,201 | 8.19 | 99.95 | Putative TPR domain-containing protein (Solanum demissum) | Protein-protein interaction, function unknown |

| H6601 | 38,334 | 6.82 | 0.10 | 0.045 | 15234171 | 87,056 | 5.06 | 98.42 | Unknown protein (Arabidopsis) | Unknown |

| L1508 | 28,745 | 5.34 | 0.50 | 0.032 | 8809640 | 48,283 | 9.17 | 100.00 | Unnamed protein product (Arabidopsis) | Unknown |

| L3803 | 40,865 | 5.51 | 0.16 | 0.001 | 34897322 | 14,410 | 12.13 | 98.59 | Hypothetical protein (rice) | Unknown |

| L8207 | 16,999 | 6.24 | 0.52 | 0.014 | 20197672 | 49,600 | 8.96 | 99.67 | Unknown protein (Arabidopsis) | Unknown |

| H1615 | 46,120 | 6.35 | 0.57 | 0.025 | No data | |||||

| H2508 | 34,312 | 6.42 | 0.43 | 0.018 | No data | |||||

| H3305 | 27,172 | 6.49 | 0.00 | 0.029 | No data | |||||

| H3401 | 31,731 | 6.44 | 0.36 | 0.016 | No data | |||||

| H3604 | 38,559 | 6.50 | 0.00 | 0.000 | No data | |||||

| H4307 | 25,043 | 6.55 | 0.50 | 0.010 | No data | |||||

| H4604 | 37,200 | 6.54 | 0.19 | 0.023 | No data | |||||

| H5301 | 27,368 | 6.59 | 0.01 | 0.015 | No data | |||||

| H5314 | 27,261 | 6.65 | 0.41 | 0.023 | No data | |||||

| H5317 | 25,694 | 6.65 | 0.13 | 0.006 | No data | |||||

| H6101 | 18,465 | 6.88 | 0.26 | 0.003 | No data | |||||

| H6404 | 31,649 | 6.92 | 0.46 | 0.023 | No data | |||||

| H8301 | 24,610 | 7.22 | 0.44 | 0.021 | No data | |||||

| L2906 | 64,839 | 5.49 | 0.19 | 0.001 | No data | |||||

| L3303 | 23,062 | 5.55 | 0.51 | 0.000 | No data | |||||

| L5809 | 44,055 | 5.71 | 0.30 | 0.008 | No data | |||||

| L4511 | 27,492 | 5.65 | 0.43 | 0.003 | No data | |||||

| L7308 | 21,675 | 6.02 | 0.19 | 0.003 | No data | |||||

| L8407 | 25,529 | 6.28 | 0.44 | 0.000 | No data | |||||

| L8704 | 37,918 | 6.19 | 0.27 | 0.000 | No data |

In-gel pI and Mr.

Predicted pI and Mr.

Four up-regulated spots were related to photosynthetic carbohydrate synthesis. Three of them were identified as ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase large subunit and one spot as PSII oxygen-evolving complex protein 2 (Fig. 1).

Eight up-regulated spots are proteins involved in cell wall metabolism (Fig. 1). These included type IIIa membrane protein cp-wap-13, UDP-Glc dehydrogenase, and UDP-GlcUA decarboxylase. SUS were also included in this group because of their known role in cell wall biosynthesis (Baroja-Fernandez et al., 2003).

Three spots were identified as Golgi GDP Man transporter. Two of these spots were up-regulated and one was down-regulated. Transport of nucleotide sugars across the Golgi apparatus membrane is required for the luminal synthesis of a variety of plant cell surface components, such as cell wall polysaccharides (Baldwin et al., 2001).

Amino acid metabolism was also up-regulated. Of these, eight up-regulated proteins and one down-regulated protein were Met synthases. Other up-regulated proteins in this category were glutathione reductase (one spot), phospho-Ser aminotransferase (one spot), and hydroxymethyltransferase (one spot). The down-regulated spots included one ketol-acid reductoisomerase.

Proteins involved in defense and stress responses included 24 up-regulated proteins and 10 down-regulated proteins. Among the stress proteins identified were glutathione S-transferase (GST; one up-regulated spot), glutathione-dependent formaldehyde dehydrogenase (FALDH; one up-regulated spot), peroxidase (one up-regulated spot), and different heat shock proteins (HSPs; two up- and three down-regulated spots). Five up-regulated protein spots were identified as nucleotide-binding site (NBS)/Leu-rich repeat (LRR) resistance protein-like proteins. These proteins are known to have a major role in plant defense responses. Phe ammonium lyase (PAL; one spot), another defense-related protein, was found to be up-regulated. The proteins oxalate oxidase, β-glucosidase, and Met synthases, which were described above, are also implicated in stress responses.

Within the categories of secondary metabolism and protein biosynthesis, the sum of up- and down-regulated proteins did not seem to differ significantly. The category of protein biosynthesis included different isomeric forms of 60s ribosomal protein, HSP70, and heat shock cognate protein, both in the up- and down-regulated groups (Tables I and II). The secondary metabolism category was comprised of β-glucosidase.

Proteins involved with DNA metabolism and genetic information processing included 16 up-regulated spots and four down-regulated spots (Fig. 1). The up-regulated spots included transcription factors and nuclear proteins such as RNA polymerase I, II, and III 24.3-kD subunit (one spot), RNA-binding protein (one spot), putative nuclear protein that is similar to BRUSHY1 nuclear protein from Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana; eight up- and four down-regulated spots), BTB/POZ domain-containing protein (one spot), splicing factor SC35 (one spot), FCP1-like phosphatase (one spot), and a DNA repair-recombination protein, RAD50 (one spot). This suggests that the differences we see in plant proteome complexity after Trichoderma colonization require the involvement of regulatory proteins. Thus, colonization of roots by Trichoderma induces major proteome changes in the shoots. The plant development category included β-glucosidase. The β-glucosidase of maize was shown to hydrolyze cytokinin-conjugate and release free cytokinin during plant growth and development (Brzobohaty et al., 1993). Another down-regulated spot was identified as a DVL protein (one spot). This class of small polypeptides was found to affect Arabidopsis development (Wen et al., 2004).

The 109 protein spots identified with a known molecular function corresponded to 42 different molecular functions, which means that 61.5% of the identified proteins had functions similar to that of at least one other protein. It is possible that these multiple forms corresponded to products of different genes or to posttranslational modifications of the same gene product. We retrieved maize sequences from different databanks (NCNInr, The Institute for Genomic Research [TIGR] maize, and Unigene) to determine the different genes encoding for different proteins for each molecular function we identified. We then further compared peptides identified from the MS analysis to determine whether the proteins from each molecular function correspond to the same gene product or to different gene products. For example, we had identified 17 up-regulated spots as GAPDH (Table I). Ten of them were identified as products of gpc1 and six as gpc2 gene products. Another one was identified as encoded by gapA, which is expressed in chloroplasts. Of the down-regulated spots identified as GAPDH (Table II), one spot each of gpc1 and gpc4 gene products and two spots each of gpc2 and gpc3 gene products were identified.

Another example is the numerous spots identified as Met synthase (Tables I and II). Sequence similarity searches for Met synthase combined with contig building of the sequences gave several different genes. Three were gene products of known cDNA accessions 54651562, 21207871, and 17017262 and two partial protein fragments predicted from sequences retrieved from TIGR maize (AZM5_44038 and AZM5_47064). These two partial sequences had 77% and 80% similarity to the gene product of accession 17017262. Comparison of the peptides of the identified spots indicated that seven spots corresponded to the gene product of 17017262. The spot L2406 was more similar to the gene product of 21207871, but it was not identical to any of the sequences (six identical peptides and four with more than 87% identity). The spot L0605 was more similar to the gene product of 17017262 but not identical to any of the sequences (four identical peptides and three with more than 87% identity). It could be that these two spots are identical to another yet-unknown maize Met synthase protein. The partial sequences we identified as similar to the known Met synthases suggest that unknown Met synthases may exist.

In another case, five spots were identified as SUS (Table I). All of their peptide sequences were consistent with them being a gene product of sus1, suggesting the involvement of posttranslational modifications.

Validation of Selected Genes and Processes

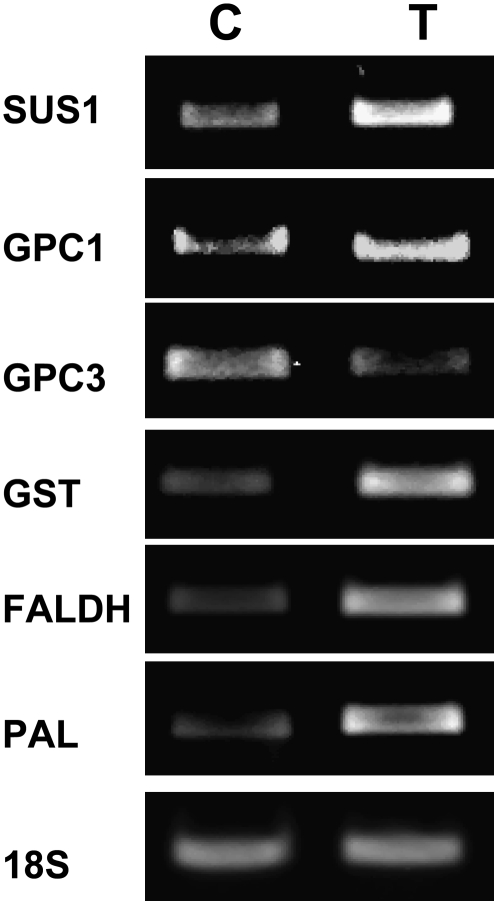

RNA extracted from 7-d-old seedlings treated with either Trichoderma or control treatment was used to validate the expression of selected genes by semiquantitative reverse transcription (RT)-PCR (Fig. 2). While SUS1 and GPC1 were up-regulated, GPC3 was down-regulated. The defense- and stress-related genes, GST, FALDH, and PAL, were also up-regulated.

Figure 2.

Validation of selected genes. Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis was performed for selected genes using RNA of shoots from control (C) and Trichoderma-treated (T) plants. PCR was conducted for 20 cycles for all genes. 18S was used as a reference gene and 18 cycles were performed on a 10-fold dilution of the RT reaction.

In addition, the starch content of the shoots was determined and found to be 23.95 (±0.23, n = 10) mg/plant and 34.27 (±0.34, n = 10) mg/plant for control and Trichoderma-treated plants, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Trichoderma spp. induce a wide variety of responses in plants. T22 has been shown in maize to increase seed germination (Bjorkman et al., 1998), increase growth of seedlings that continues to provide increased yields in field-grown plants, enhance nitrogen fertilizer use efficiency and increase plant greenness (Harman, 2000, 2001; Harman and Donzelli, 2001; Harman et al., 2004b), and induce systemic resistance (Harman et al., 2004a, 2004b). Thus, while T22 is restricted to roots, there are numerous changes in the phenotypic responses of shoots, indicating that the effects of this plant symbiotic fungus are systemic. Because there are so many system-wide changes in maize induced by T22, it would appear that there must be numerous changes in the physiology of the plant.

To study the hypothesized wide diversity of changes that T22 and, by extension, other Trichoderma species induce in maize and other plants, we investigated changes in the proteome of maize seedlings. The total changes in the proteome were large: 117 proteins were detected whose expression was enhanced and 50 that were significantly down-regulated by root colonization by T22. However, proteins in some metabolic processes were affected more than proteins involved in other processes.

Proteins involved in carbohydrate metabolism were strongly affected. Seventeen proteins present in higher concentrations in T22 colonized plants were GAPDHs. Ten were derived from the gpc1 gene product and six from gpc2, which demonstrates that there are substantial posttranslational changes in at least some of the members of this gene family. Several spots of gpc1 and gpc2 were up-regulated, while spots of gpc3 and gpc4 were only down-regulated. Plants contain three forms of GAPDH: a cytosolic form that participates in glycolysis and two chloroplast forms that participate in photosynthesis. Maize cytosolic GAPDH is encoded by a small multi-gene family. One group of this gene family, gpc1 and gpc2, are 97% identical, while gpc3 and gpc4 are 99.4% identical (Manjunath and Sachs, 1997). Transcript levels of gpc3 and gpc4 are increased by anaerobic conditions, while transcript levels of gpc1 and gpc2 remain constant or decrease under anoxic conditions (Manjunath and Sachs, 1997). The gapA gene product is localized in chloroplasts (Brinkmann et al., 1989). These data suggest that gene products of this enzyme family that are functional in efficient aerobic respiration are enhanced in quantity by T22, along with chloroplast forms, while forms that function in suboptimal (anaerobic) conditions are repressed.

FBA, an enzyme that, like GAPDH, is involved in glycolysis, was also up-regulated. Up-regulation of FBA was also observed in proteome analysis of germinating maize embryos infected with fungal pathogen (Campo et al., 2004). Another up-regulated enzyme was fructokinase 2 (FRK2). FRK2 from tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) was shown to be expressed in leaves and to play a specific role in contributing to stem and root growth, while suppression of this gene resulted in much shorter plants (Odanaka et al., 2002). Strong expression of maize FRK2 in stems suggests a similar role (Zhang et al., 2003); enhanced expression of the analogous gene in maize may have a similar role in greater growth of this plant. MDH was also up-regulated. As a member of the tricarboxylic acid cycle, MDH is involved in providing reducing power and in C4 plants, such as maize, is involved in photosynthetic fixation of CO2. Other enzymes involved in carbohydrate metabolism up-regulated in shoots by the interaction of plant roots with T22 are β-glucosidases, 3-phosphoglycerate kinase, and oxalate oxidases. Finally, five up-regulated spots were identified as SUS isozymes, one of which was highly up-regulated. The different spots of SUS could be posttranslational modifications such as phosphorylation as shown by Duncan et al. (2006). SUS is a key enzyme in Suc utilization in plants. The pathway of Suc degradation by SUS is favored particularly under energy-limiting conditions because of the overall low energy costs. Several studies demonstrate the involvement of SUS enzymes in starch biosynthesis (Chourey et al., 1998; Barratt et al., 2001; Munoz et al., 2005). Shoots of Trichoderma-treated plants had higher starch contents. All of these data are consistent with the concept that, in the presence of T22, energy metabolism via both glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid cycle is up-regulated. This would be, of course, consistent with the more rapid growth in the presence of T22.

In addition, four genes associated with photosynthesis, including two forms of Rubisco large subunit, Rubisco, and PSII oxygen-evolving complex protein 2, were also present in higher quantities in spots from T22-treated than from control plants. This, together with the increased levels of gap1, is suggestive of a higher photosynthetic rate from T22-treated than control plants. It has been demonstrated that T22 enhances leaf greenness in maize by measuring with a chlorophyll meter (Minolta SPAD 502 m; Harman, 2000). The data therein is on mature plants demonstrating the long-term effect of the Trichoderma on the plants. Our results are consistent with these observations and are suggestive of an increased photosynthetic rate. However, because our study was done with relatively small seedlings that grow more rapidly from T22-treated seeds, this suggestion must be tentative, because the smaller seedlings without T22 may be less advanced in development of photosynthetic machinery.

In most plants, Suc is both the primary product of photosynthesis and the transported form of assimilated carbon. It is synthesized in mesophyll cells of photosynthetically active parts of the plant, such as mature leaves, and translocated via the phloem to the sink tissues, such as young leaves and seeds. In a study of the maize protein PRms, which localizes to plasmodesmata, an enhancement of Suc efflux from photosynthetically active leaves resulted in enhanced growth response. It appeared that in the transgenic PRms-overexpressing plants, most of the photoassimilates produced in source leaves were rapidly transported via the phloem to supply more energy and carbon resources to the growing parts of the plant (Murillo et al., 2003). Moreover, soluble sugars, in addition to playing a central role in energy metabolism, can act as signaling molecules that control gene expression in plants in a manner similar to that of classical plants hormones (Sheen et al., 1999; Smeekens, 2000). PRms-overproducing plants also overexpressed PR1a, PR5, and chitinase genes. These plants were also resistant to plant pathogens, suggesting that increased sugar levels in leaf tissue correlate with increased resistance (Murillo et al., 2003). In T22-inoculated plants, we observed both plant growth enhancement and induced plant resistance to subsequent pathogen attack (Harman et al., 2004b). It could be that in our system, activation of carbohydrate metabolism contributed to both enhanced growth response and induced resistance of plants treated with Trichoderma.

Given the increased levels of enzymes involved in respiratory pathways, together with increased levels of proteins involved in photosynthesis and Suc regulation, and the general increase in plant growth induced by T22 in maize, we hypothesized that proteins and enzymes associated with cell wall expansion will be affected. SUS has a dual role in producing both ADP-Glc, necessary for starch biosynthesis, and UDP-Glc, necessary for cell wall and glycoprotein biosynthesis. A significant amount of maize SUS1 protein was found to be membrane bound (Duncan et al., 2006), and this membrane-bound form has an important role in synthesis of cell wall material (Amor et al., 1995; Hardin et al., 2004). UDP-Xyl is a nucleotide sugar involved in the synthesis of diverse plant cell wall hemicelluloses (xyloglucan, xylan). The biosynthesis of UDP-Xyl occurs both in the cytosol and in membrane-bound compartments. The major biosynthetic route occurs through the conversion of UDP-Glc. This conversion involves two enzymatic steps: the oxidation of UDP-Glc to UDP-glucuronate by a UDP-Glc dehydrogenase and the subsequent decarboxylation to UDP-Xyl by a UDP-glucuronate decarboxylase. Regulation of these enzymes is important in understanding the partitioning of carbon into hemicellulose away from starch, Suc, and cellulose, which are irreversible processes. Biochemical evidence suggests that the timing of expression of UDP-Glc dehydrogenase and of UDP-glucuronate decarboxylase may control the flux of carbon into hemicellulose in differentiating vascular tissues (Harper and Bar-Peled, 2002; Bindschedler et al., 2005). Both UDP-Glc dehydrogenase and UDP-GlcUA decarboxylase were up-regulated, indicating that this biochemical pathway leading to cell wall synthesis is increased in leaves of Trichoderma-inoculated plants.

Another up-regulated spot from shoots was identified as type IIIa membrane protein cp-wap13, which belongs to the RGP family. The protein cp-wap13 from cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) is homologous to se-wap41, a maize protein associated with the Golgi apparatus. The maize protein, a 41-kD protein isolated from maize mesocotyl cell walls, immunolocalizes to plasmodesmata. This enzyme has a possible role in the synthesis of cell wall polysaccharides (cellulose biosynthesis) in plants (Delgado et al., 1998). It is found associated with the cell wall, with the highest concentrations in the plasmodesmata (Epel et al., 1996). Another RGP family up-regulated protein, which has a possible role in the synthesis of cell wall polysaccharides in plants and was identified from roots, is α-1,4-glucan-protein synthase 1 (UDP forming; data not shown). Trichoderma inoculation of roots results in cell wall deposits in the roots that confine the fungi to the outer root layer (Yedidia et al., 2000). Moreover, here we describe that cell wall metabolism is also up-regulated in the shoots. We suggest that this benefits the plants' resistance by strengthening physical barriers in the shoots.

Golgi GDP Man transporter isoform was mainly up-regulated. Domain analysis of this protein identified a TFIIS signature; hence, automatic annotation of this protein indicates it is involved in transcriptional regulation. However, the function of the protein as a GDP Man transporter has been demonstrated (Baldwin et al., 2001). Transport of nucleotide sugars across the Golgi apparatus membrane is required for the luminal synthesis of a variety of plant cell surface components, such as cell wall polysaccharides (Baldwin et al., 2001). This probably contributes to cell wall metabolism.

Amino acid synthesis enzymes also were up-regulated; however, most of this group was composed of Met synthase. The strong up-regulation of Met synthase, especially in the absence of most other amino acid synthases, suggests that the Met may be involved in a function other than protein synthesis. Met synthases catalyze the formation of Met, which is further transformed into S-adenosyl-l-Met (SAM). SAM is a precursor for the phytohormone ethylene, a hormone affecting stress responses (Broekaert et al., 2006). It was found, for example, that the protein level of Met synthase is also significantly increased in barley (Hordeum vulgare) leaves under salt stress (Narita et al., 2004). Met synthase and SAM synthase were also up-regulated in maize plants treated with potassium dichromate (Labra et al., 2006). Moreover, ethylene is an essential signaling molecule in induced resistance responses (Bostock et al., 2001). The jasmonate/ethylene pathway of induced resistance was shown to be induced in cucumbers inoculated by Trichoderma asperellum (Shoresh et al., 2005). Evidence for the involvement of ethylene in plant systemic responses to Trichoderma inoculation was also demonstrated by Seggara et al. (2007) and by Djonovic et al. (2007). The strong increase in Met synthase in maize whose roots are colonized by T22 and the induced systemic resistance that is generated in this system (Harman et al., 2004b) are consistent with the concept that ethylene is involved in the response of maize to Trichoderma inoculation.

Numerous other proteins involved in stress- and defense-related systems were found to be up-regulated in maize colonized by T22. For example, forms of both PAL and peroxidase were up-regulated. The gene encoding for PAL is believed to be activated by the jasmonic acid/ethylene signaling pathway of induced plant resistance (Diallinas and Kanellis, 1994; Mitchell and Walters, 1995; Kato et al., 2000). PAL is the first enzyme in the phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathway, which provides precursors for lignin and phenols, as well as for salicylic acid (Mauch-Mani and Slusarenko, 1996). Other enzymes of the phenylpropanoid pathway, including peroxidases, are also induced in resistant reactions. Peroxidases are also known for their role in the production of phytoalexins, reactive oxygen species (ROS), and formation of structural barriers (Kawano, 2003; Passardi et al., 2005). In another study, we also discovered that chitinolytic enzymes also are up-regulated (Shoresh and Harman, 2008). Proteins with abilities to degrade chitin usually have acidic or basic isoelectric points and so were not detected in this study. These results are consistent with the observation that transcription of genes encoding these enzymes, and activity of these enzymes, also were enhanced in the cucumber-T. asperellum system (Yedidia et al., 2000, 2003; Shoresh et al., 2005). This provides further evidence of the similarities in resistance processes in the two different Trichoderma plant systems.

Another potentially important up-regulated protein in defense systems is oxalate oxidase. The size of an up-regulated protein is in agreement with the size of the enzymatically active homohexameric form (Woo et al., 2000). A down-regulated spot of the enzyme was also detected, but it was smaller than the active form. Oxalate oxidase degrades oxalate to carbonate and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and is probably involved in producing an oxidative burst of H2O2, which is expected to be involved in plant resistance systems. Evidence for the role of this protein is provided by the fact that wounding of ryegrass (Lolium perenne) induced up-expression of several oxalate oxidases coincidental with a burst of H2O2. In this system, expression of oxalate oxidase encoding genes was enhanced by an exogenous supply of H2O2 or methyl jasmonate (Le Deunff et al., 2004). Resistance to Sclerotinia minor in peanut (Arachis hypogaea; Livingstone et al., 2005) and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in sunflower (Helianthus annuus) was enhanced by expressing oxalate oxidase genes (Hu et al., 2003). In sunflower, overexpression of oxalate oxidase evoked defense responses, such as elevated levels of H2O2 and salicylic acid, and induction of defense-related gene expression (Hu et al., 2003). The increase in both oxalate oxidase and peroxidase suggests the involvement of ROS production in maize plants colonized with Trichoderma.

In dicots, the enhanced presence of enzymes that produce ROS such as H2O2 might be considered an indicator of induction of the salicylate pathway. However, there are differences between resistance responses in monocots and dicots; for example, rice (Oryza sativa) contains high levels of endogenous salicylic acid, and application of this chemical is less active in inducing resistance than functional synthetic analogues (Kogel and Langen, 2005). Further, there are lessened effects of salicylate on accumulation of pathogenesis-related proteins, although induced resistance still seems to require the rice homolog of NPR1 (Kogel and Langen, 2005). Mei et al. (2006) suggest a role for the ethylene/jasmonate pathway in monocot defense response, while the role of the salicylate pathway is less clear, especially in light of the constitutive production of this signaling molecule in rice and other monocots.

Other stress-related proteins that were up-regulated included GST and glutathione-dependent FALDH. Plants detoxify some contaminants by conjugating them, or their metabolites, to glutathione. These reactions are catalyzed by enzymes such as GST and FALDH (Fliegmann and Sandermann, 1997; Dixon et al., 2002). In addition, under conditions of environmental stress, when ROS such as H2O2 are produced, these detoxifying proteins act as scavenging enzymes and play a central role in protecting the cell from oxidative damage. For example, GST proteins were also found to be up-regulated in both compatible and noncompatible interactions with pathogens in Arabidopsis (Jones et al., 2004). One of these, GSTF8, showed particularly dynamic responses to pathogen challenge (Jones et al., 2004) and was also induced by H2O2 through the activation of MPK3/MPK6 (Kovtun et al., 2000). The homolog of MPK3 from cucumber was shown to be crucial for plant response to Trichoderma inoculation (Shoresh et al., 2006). It will be interesting, therefore, to determine whether the GST up-regulation in maize post Trichoderma colonization is via this MPK3 homolog.

In plants, the β-glucosidases are associated with a variety of functions that include chemical defense against pathogens and pests through the production of hydroxamic acids from hydroxamic acid glucosides (Czjzek et al., 2001). Although four spots were up-regulated versus five down-regulated spots of the identified β-glucosidase, one of the up-regulated spots was increased by 10-fold. This substantial increase may suggest a potential role for this enzyme in the Trichoderma-induced defense response.

Other stress proteins identified to be up-regulated are HSPs from the HSP70 family. The 70-kD stress proteins comprise a ubiquitous set of highly conserved molecular chaperones. Some family members are constitutively expressed, while others are expressed only when the organism is challenged by environmental stresses, such as temperature extremes, anoxia, heavy metals, and predation (Miernyk, 1999). Interestingly, in this study, three HSP isoforms were down-regulated, while one was up-regulated. This suggests that different isoforms have different functions.

Many spots categorized as stress proteins were also included in other categories. The same occurs for the cell wall metabolism category. However, these categories also include spots that belong solely to the stress- and cell wall-related processes, thus supporting the interpretation that these processes are indeed up-regulated. In support of our findings, several stress-related proteins were found to be up-regulated in another proteomic study of cucumber plants inoculated with T. asperellum (Seggara et al., 2007).

Several up-regulated protein spots were identified as NBS/LRR resistance protein-like proteins. A recent study also showed that the level of NBS/LRR proteins increased in leaves interacting with Trichoderma (Marra et al., 2006). These disease resistance genes (R) are the specificity determinants of plant immune responses. When these proteins identify a specific pathogen avr protein (presumably through another partner protein), a cascade of signal transduction is triggered, which results in a resistance response known as the hypersensitive response (Belkhadir et al., 2004). The NBS-LRR proteins contain a series of LRRs, an NBS, and a putative amino-terminal signaling domain. The LRRs of the R proteins are determinants of response specificity. The amino terminus is required for protein-protein interactions with an adaptor protein, whereas the NBS domain is responsible for ATP hydrolysis and release of the signal.

Proteins with a role in plant growth and development, through a mechanism different than energy and sugar metabolism, were identified in this study. The β-glucosidases identified in this study were gene products of ZmGLU1. In maize, ZmGLU1 is one of the β-glucosidases that has been suggested to hydrolyze cytokinin-O-glucosides to liberate free cytokinins (Brzobohaty et al., 1993). Although inactive cytokinin conjugate is abundant in plants, only a small amount of free cytokinins are available to stimulate and control plant growth (Sakakibara, 2006). The O-glucosides are the major mobilizable conjugated form of cytokinin from which active cytokinin can be released by ZmGLU1. As such, ZmGLU1 is one of the key enzymes controlling cytokinin homeostasis in maize. Thus, involvement of ZmGLU1 in plants interacting with Trichoderma suggests this interaction affects plant development through plant growth hormones.

Another interesting protein identified in shoots is a DVL homolog. Arabidopsis plants overexpressing DVL were about 70% of the height of wild-type plants under the same growth conditions (Wen et al., 2004). In our study, we found one DVL member that was down-regulated in maize by root colonization by T22. Because activation of DVL seems to have a negative effect on plant growth, if DVL has similar activities in maize as in Arabidopsis, down-regulation may limit its growth inhibition effect, perhaps contributing to the enhanced growth response.

Finally, all of these changes would suggest that there must also be alterations in genetic processing systems and this is indeed the case. Among the up-regulated proteins were the transcription factors and nuclear proteins RNA polymerase I, II, and III 24.3-kD subunit, RNA-binding protein, and the splicing factor SC35. Another spot was identified as a putative nuclear protein that is 74% similar to BRUSHY1 nuclear protein from Arabidopsis that may be implicated in chromatin dynamics and genome maintenance (Guyomarc'h et al., 2006). BTB/POZ domain-containing protein was also identified. The BTB/POZ domain is found in many animal transcriptional regulators (Collins et al., 2001). Although BTB/POZ domain proteins are numerous in plants, very few are yet characterized. One spot was identified as FCP1-like phosphatase. In yeast FCP1 is an essential protein Ser phosphatase that dephosphorylates the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II, thus controlling its activity (Majello and Napolitano, 2001). RAD50 was implicated in DNA recombination and replication, meiosis, telomere maintenance, and cellular DNA damage responses (Daoudal-Cotterell et al., 2002).

In support of our findings, in tomato plants inoculated with Trichoderma hamatum, the expression of stress-, cell wall-, and RNA metabolism-related genes was also up-regulated, demonstrating similarities of plant responses to Trichoderma (Alfano et al., 2007). In this tomato-Trichoderma system, no positive growth response was recorded. Interestingly, in this system, there were also no carbohydrate metabolism-related genes up-regulated. This suggests that there may be a direct connection between the ability of Trichoderma to induce carbohydrate metabolism and its ability to induce growth response.

CONCLUSION

We present here a detailed analysis of proteome differences between maize plants colonized with the biocontrol agent T22. Comprehensive dissection of the information into biochemical pathways strongly suggested that Trichoderma interaction with plant roots results in controlled activation of carbohydrate metabolic processes as well as enhancement of photosynthesis, providing the growing plant with more energy and carbon source for their growth. Other growth signals may also be induced. Stress- and defense-related pathways are also induced, probably involving ethylene signal transduction. Induction of cell wall metabolism may serve to strengthen cell barriers, adding to the resistance of the plants. Knowing the molecular mechanism that underlies the plant response to Trichoderma inoculation could be useful in designing new generations of more efficient biocontrol and growth enhancement strategies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant and Fungal Material

Seeds of maize (Zea mays) inbred Mo17 were treated with T22 in a cellulose-dextran formulation (1–2 × 109 cfu/g; Harman and Custis, 2006) or were treated with water. Application of the cellulose-dextran powder without T22 gave no observable change in plant growth (data not shown). The cellulose-Trichoderma powder was suspended in water (38.5 mg/5 mL) and 100 μL was applied to 5 g of seeds. Treated seeds were planted in sandy loam field soil in boxes (10.5 × 10.5 × 6 cm), five seeds per box and 10 boxes per treatment in each experiment. The experiments were done independently four times. Boxes were incubated in a growth chamber with diurnal fluorescent lighting with a 16-h-light/8-h-dark cycle at 22°C ± 4°C, and watered as needed. Seven-day-old seedlings were harvested: the shoots were first measured and then excised at the soil level, frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −70°C until use.

Protein Extraction

Root and shoot tissue samples were ground with liquid nitrogen followed by further grinding in 1.5 mL of ice-cold 2% dithiothreitol (DTT) per 0.5 g of tissue powder in Ten Broeck homogenizers. The homogenate was then centrifuged for 20 min at 15,000 rpm at 4°C. Proteins were precipitated from the supernatant by adding 8 volumes of ice-cold acetone and incubating 2 to 16 h at −20°C. After similar centrifugation, the precipitated proteins were washed twice with 2 mL of ice-cold acetone followed by drying under a flow of N2. Powder was then dissolved in sample solubilization buffer (8 m urea, 4% CHAPS, 50 mm DTT). A small aliquot was diluted 50-fold with water, and the protein content was determined using Coomassie Plus Protein Assay (Pierce) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2-DE and In-Gel Digestion

Samples of 650 μg were separated in the first dimension by isoelectric focusing and in the second dimension by SDS-PAGE. Immobilized pH gradient strips (13 cm long, pH 5.3–6.5 or 6.3–7.5; GE Healthcare) were used to perform the first-dimension electrophoresis. Isoelectric focusing was carried out following the manufacturer's recommended protocol using a Multiphore II isoelectric focusing system (Pharmacia Biotech). Before performing the second dimension, the strips were first equilibrated in DTT containing equilibration buffer followed by a second equilibration in iodoacetamide containing equilibration buffer. The second-dimension electrophoresis was performed in a 12% homogeneous Tris-SDS polyacrylamide gel (15 × 16 × 0.15 cm) and was run at 32 mA for 4.5 h in a Multiphore II apparatus (Pharmacia Biotech). Proteins were stained with Colloidal Coomassie Blue (Invitrogen). The resulting patterns were scanned at 633 nm (Typhoon 9410 Laser scanner; GE Healthcare) and gel images were analyzed using PDQuest software (Bio-Rad). The experiment was conducted four times and each experiment was comprised of its own set of plants and 2-DE gels. Proteins from each biological repeat were separated using both pI ranges of 5.3 to 6.5 and 6.3 to 7.5. Analyzed spots met the following criteria: their “quality” scores assigned by the software were over 25 and each spot was present in at least three of the four replicate gels. We picked spots that had at least a 2-fold difference in intensity between treated and control plants. Spot intensities were normalized to the total intensities of valid spots. Spots that had higher intensity in the T22-treated plants were picked from their resulting protein gel, while those having higher intensities in the control plants were picked from the protein gels of the control. Spots were excised manually, and in-gel digestion with trypsin was performed at 37°C overnight in 25 mm ammonium bicarbonate/10% acetonitrile.

MS Analysis and Protein Identification

Proteins were identified by peptide mass fingerprinting (PMF) using MALDI-TOF MS or by peptide sequencing using nESI-IT MS/MS). The MALDI-TOF MS analysis was performed using a model 4700 Proteomics Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) in positive ion reflector mode for MS acquisition and 1-kV collision energy mode for MS/MS (PSD) acquisition. The nESI-IT MS/MS experiments were performed on an LC Packings (Dionex)/4000 Q Trap (Applied Biosystems) in positive ion mode. Protein identification by PMF or nanospray sequencing was carried out using the PMF-GPS Explorer, ESI-Analyst (Applied Biosystems) software. Nonredundant National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) and SwissProt (European Bioinformatics Institute) databases were used for the search. Searches were performed in the full range of Mr and pI. When an identity search had no matches, the homology mode was used. For samples that were not identified when species restriction was applied, a search without species restriction was conducted. The maximum number of missed cleavages was set at two. Variable modifications selected for searching were carbamidomethyl-Cys and oxidation of Met. Only candidates that appeared at the top of the list and had protein confidence interval (CI) percentage over 99.5 were considered positive identifications.

Categorizing, Clustering, and Gene Family Study

Categorization of proteins was done using DAVID Bioinformatics Resources (Dennis et al., 2003), Gene Ontology (http://www.geneontology.org/GO.tools.shtml, http://www.gramene.org/plant_ontology/index.html), Gramene ontologies (http://www.gramene.org/plant_ontology/index.html), KEGG terms (http://www.genome.ad.jp/kegg/), and MetaCyc (Caspi et al., 2006). For gene family study and domain analysis, data mining tools from NCBI, EBI, ExPASy, and Softberry were used. Inter-Pro Scan and NPS@ (Combet et al., 2000) were used to examine the position of specific domains and identified peptides within the protein. Other software used were CAP3 Sequence Assembly Program and ClustalX.

Semiquantitative RT-PCR

For RNA analysis, shoots were harvested and pooled from several plants and placed immediately in liquid nitrogen and then stored at −70°C until use (maximum 1–2 weeks). Total RNA was extracted using the Tri Reagent (Sigma). RNA was treated with RNase-Free DNase Set (Qiagen) and cleaned using columns of RNeasy Plant Mini kit (Qiagen). After treatment with DNase, 1 μg of total RNA was used for a RT reaction using Superscript II (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Primers were designed according to unique sequences of the following genes: GST (gi|4468793): forward 5′-CTGCTCTACCTCAGCAAGAC-3′, reverse 5′-CAGCAGCAAATGCAAGACAG-3′; FALDH (gi|1841501): forward 5′-CTGACATCAACGACGCCTTC-3′, reverse; 5′-GCAACACAGCGGTAACCATC-3′; SUS1 (gi|514945): forward 5′-GAGCCCTCCAGCAAGTGATG-3′, reverse 5′-CGACACCCGGATCAATGATG-3′; GPC1 (gi|22237): forward 5′-GTCGTCCTCCTAGCTCCTCTAC-3′, reverse 5′-TGTCGCTGTGCTTCCAGTG-3′; GPC3 (gi|1184773): forward 5′-ACCGATTTCCAGGGTGACAG-3′, reverse 5′-CCGGGGAAGAAACACAACTC-3′; PAL (gi|17467273): forward 5′-CATGGAGCACATCCTGGATG-3′, reverse 5′-ATGACCGGGTTGTCGTTCAC-3′; and 18S (gi|1777706): forward 5′-GCGAATGGCTCATTAAATCAGTT-3′, reverse 5′-CCGTGCGATCCGTCAAGT-3′. A standard PCR was done for 20 cycles (for specific genes) or 18 cycles (for 18S). Template RT was diluted 10-fold for 18S PCR analysis. A total of 15 μL of PCR reaction was analyzed on gel and visualized and photographed on UV light. The PCR amplification was within the linear range as verified by calibration curves with template dilution series. The same procedure was repeated for four to five RNA pools to verify consistency of results.

Starch Analysis

Starch content of plant shoots was determined using starch assay kit (STA20, Sigma) according to the manufacturer's instructions but scaled for use in microtiter plates.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. A set of gels with the indication of spots that were analyzed in this study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Kristen Ondik and Thomas Bjorkman for editorial assistance and Sheng Zheng, Robert Sherwood (Cornell Proteomics Center), and Theodore Thannhauser (USDA, Ithaca) for assistance and help with proteomic analyses.

This work was supported in part by the U.S.-Israel Agricultural Research and Development fund (grant no. US–3507–04 R) and by Advanced Biological Marketing (Van Wert, Ohio). It is part of the regional project W–1147.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantphysiol.org) is: Michal Shoresh (michalsho@volcani.agri.gov.il).

The online version of this article contains Web-only data.

References

- Alfano G, Ivey MLL, Cakir C, Bos JIB, Miller SA, Madden LV, Kamoun S, Hoitink HAJ (2007) Systemic modulation of gene expression in tomato by Trichoderma hamatum 382. Phytopathology 97 429–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amor Y, Haigler CH, Johnson S, Wainscott M, Delmer DP (1995) A membrane-associated form of sucrose synthase and its potential role in synthesis of cellulose and callose in plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92 9353–9357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin TC, Handford MG, Yuseff M-I, Orellana A, Dupree P (2001) Identification and characterization of GONST1, a Golgi-localized GDP-mannose transporter in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 13 2283–2295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baroja-Fernandez E, Munoz FJ, Saikusa T, Rodriguez-Lopez M, Akazawa T, Pozueta-Romero J (2003) Sucrose synthase catalyzes the de novo production of ADPglucose linked to starch biosynthesis in heterotrophic tissues of plants. Plant Cell Physiol 44 500–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barratt DHP, Barber L, Kruger NJ, Smith AM, Wang TL, Martin C (2001) Multiple, distinct isoforms of sucrose synthase in pea. Plant Physiol 127 655–664 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belkhadir Y, Subramaniam R, Dangl JL (2004) Plant disease resistance protein signaling: NBS-LRR proteins and their partners. Curr Opin Plant Biol 7 391–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bindschedler LV, Wheatley E, Gay E, Cole J, Cottage A, Bolwell GP (2005) Characterisation and expression of the pathway from UDP-glucose to UDP-xylose in differentiating tobacco tissue. Plant Mol Biol 57 285–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorkman T, Blanchard LM, Harman GE (1998) Growth enhancement of shrunken-2 sweet corn with Trichoderma harzianum 1295-22: effect of environmental stress. J Am Soc Hortic Sci 123 35–40 [Google Scholar]

- Bostock RM, Karban R, Thaler JS, Weyman PD, Gilchrist D (2001) Signal interactions in induced resistance to pathogens and insect herbivores. Eur J Plant Pathol 107 103–111 [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmann H, Cerff R, Salomon M, Soll J (1989) Cloning and sequence analysis of cDNAs encoding the cytosolic precursors of subunits GapA and GapB of chloroplast glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase from pea and spinach. Plant Mol Biol 13 81–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broekaert WF, Delaure SL, De Bolle MFC, Cammue BPA (2006) The role of ethylene in host-pathogen interactions. Annu Rev Phytopathol 44 393–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzobohaty B, Moore I, Kristoffersen P, Bako L, Campos N, Schell J, Palme K (1993) Release of active cytokinin by a beta-glucosidase localized to the maize root meristem. Science 262 1051–1054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campo S, Carrascal M, Coca M, Abián J, San Segundo B (2004) The defense response of germinating maize embryos against fungal infection: a proteomics approach. Proteomics 4 383–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi R, Foerster H, Fulcher C, Hopkinson R, Ingraham J, Kaipa P, Krummenacker M, Paley S, Pick J, Rhee SY, et al (2006) MetaCyc: a multiorganism database of metabolic pathways and enzymes. Nucleic Acids Res 34 D511–D516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y-C, Chang Y-C, Baker R, Kleifeld O, Chet I (1986) Increased growth of plants in the presence of the biological control agent Trichoderma harzianum. Plant Dis 70 145–148 [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Harman GE, Comis A, Cheng G-W (2005) Proteins related to the biocontrol of Pythium damping-off in maize with Trichoderma harzianum Rifai. J Integr Plant Biol 47 988–997 [Google Scholar]

- Chourey P, Taliercio E, Carlson S, Ruan Y (1998) Genetic evidence that the two isozymes of sucrose synthase present in developing maize endosperm are critical, one for cell wall integrity and the other for starch biosynthesis. Mol Gen Genet 259 88–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins T, Stone JR, Williams AJ (2001) All in the family: the BTB/POZ, KRAB, and SCAN domains. Mol Cell Biol 21 3609–3615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combet C, Blanchet C, Geourjon C, Deléage G (2000) NPS@: network protein sequence analysis. Trends Biochem Sci 25 147–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czjzek M, Cicek M, Zamboni V, Burmeister WP, Bevan DR, Henrissat B, Esen A (2001) Crystal structure of a monocotyledon (maize ZMGlu1) beta-glucosidase and a model of its complex with p-nitrophenyl beta-D-thioglucoside. Biochem J 354 37–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daoudal-Cotterell S, Gallego ME, White CI (2002) The plant Rad50–Mre11 protein complex. FEBS Lett 516 164–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado IJ, Wang Z, de Rocher A, Keegstra K, Raikhel NV (1998) Cloning and characterization of AtRGP1. A reversibly autoglycosylated Arabidopsis protein implicated in cell wall biosynthesis. Plant Physiol 116 1339–1350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis G, Sherman B, Hosack D, Yang J, Gao W, Lane HC, Lempicki R (2003) DAVID: Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery. Genome Biol 4 3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diallinas G, Kanellis AK (1994) A phenylalanine ammonia-lyase gene from melon fruit: cDNA cloning, sequence and expression in response to development and wounding. Plant Mol Biol 26 473–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon D, Lapthorn A, Edwards R (2002) Plant glutathione transferases. Genome Biol 3 reviews3004.3001–reviews3004.3010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djonovic S, Vargas WA, Kolomiets MV, Horndeski M, Weist A, Kenerley CM (2007) A proteinaceous elicitor Sm1 from the beneficial fungus Trichoderma virens is required for systemic resistance in maize. Plant Physiol 145 875–889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan KA, Hardin SC, Huber SC (2006) The three maize sucrose synthase isoforms differ in distribution, localization, and phosphorylation. Plant Cell Physiol 47 959–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epel BL, Van Lent JWM, Cohen L, Kotlizky G, Katz A, Yahalom A (1996) A 41kDa protein isolated from maize mesocotyl cell walls immunolocalizes to plasmodesmata. Protoplasma 191 70–78 [Google Scholar]