Abstract

Petals and leaves share common evolutionary origins but perform very different functions. However, few studies have compared leaf and petal senescence within the same species. Wallflower (Erysimum linifolium), an ornamental species closely related to Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), provide a good species in which to study these processes. Physiological parameters were used to define stages of development and senescence in leaves and petals and to align these stages in the two organs. Treatment with silver thiosulfate confirmed that petal senescence in wallflower is ethylene dependent, and treatment with exogenous cytokinin and 6-methyl purine, an inhibitor of cytokinin oxidase, suggests a role for cytokinins in this process. Subtractive libraries were created, enriched for wallflower genes whose expression is up-regulated during leaf or petal senescence, and used to create a microarray, together with 91 senescence-related Arabidopsis probes. Several microarray hybridization classes were observed demonstrating similarities and differences in gene expression profiles of these two organs. Putative functions were ascribed to 170 sequenced DNA fragments from the libraries. Notable similarities between leaf and petal senescence include a large proportion of remobilization-related genes, such as the cysteine protease gene SENESCENCE-ASSOCIATED GENE12 that was up-regulated in both tissues with age. Interesting differences included the up-regulation of chitinase and glutathione S-transferase genes in senescing petals while their expression remained constant or fell with age in leaves. Semiquantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction of selected genes from the suppression subtractive hybridization libraries revealed more complex patterns of expression compared with the array data.

Both leaves and flowers have a finite life span, and since it is thought that all floral organs, including petals, evolved from leaves (Friedman et al., 2004), we might expect commonality in their senescence mechanisms. Both in leaves and petals, a key feature of senescence is remobilization of resources; in both organs, this has been demonstrated experimentally using isotope labeling (Nichols and Ho, 1975; Mae et al., 1985; Bieleski, 1995) or pigment transport (Erdelská and Ovečka, 2004). This is reflected in some of the major classes of genes whose expression is up-regulated in both these tissues during senescence. These include genes encoding proteases, nucleases, and enzymes involved in lipid and carbohydrate metabolism (Buchanan-Wollaston, 1997; Wagstaff et al., 2002). In both organs, remobilization requires a carefully orchestrated dismantling of the cellular machinery to avoid cell death until remobilization is complete. In leaves, senescence-associated genes (SAGs) have been classified into two expression types: those exclusively expressed during senescence (class I) and those whose expression increases during senescence from a basal level (class II; Gan and Amasino, 1997). However, within these classes, there are diverse expression patterns (Smart, 1994; Buchanan-Wollaston, 1997), indicating different regulatory pathways. Levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) rise in both petals and leaves during senescence (Borochov and Woodson, 1989; Merzlyak and Hendry, 1994), maybe as a result of macromolecule degradation. This is accompanied by up-regulation of genes involved in protection against ROS, such as catalase in leaves (Buchanan-Wollaston and Ainsworth, 1997; Zimmermann et al., 2006) and superoxide dismutase in petals (Panavas and Rubinstein, 1998).

The roles of petals and leaves are very different, as are their development and the signaling mechanisms that trigger their senescence. An early step in petal development is the conversion of chloroplasts to chromoplasts (Thomson and Whatley, 1980), and this has been compared with the transformation of chloroplasts into gerontoplasts that occurs during leaf senescence (Thomas et al., 2003), implying similarities between developing (nonsenescent) petals and senescent leaves. This would suggest that senescence-associated events in petals may occur at an earlier stage compared with leaves and that cellular degradation accompanied by the expression of some genes that are highly up-regulated in senescent petals is already evident while the petals are in the early stages of development (Wagstaff et al., 2002, 2003). The primary function of petals is to attract pollinators, so they are frequently highly pigmented and scented and a sink rather than a source of photosynthates. Floral life span is closely linked to pollination in some species, which triggers rapid floral deterioration (Stead and van Doorn, 1994). However, even in the absence of pollination, floral life-span is finite. Although a few environmental factors such as temperature and drought can affect floral longevity, senescence is irreversible in the majority of species and there is tight species-specific control over the maximum duration of a flower (Primack, 1985). In contrast, leaves are sources of photosynthate for most of their life span, and their longevity is strongly influenced by nutrient status, light, and other environmental factors. Fertilization does accelerate leaf senescence in some species (Hayati et al., 1995) but not in others, such as Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana; Hensel et al., 1993). However, as in petals, expression of some genes associated with leaf senescence is also detected before visible signs of deterioration (Buchanan-Wollaston, 1997), indicating that in both petals and leaves senescence processes may be initiated early.

Two classes of plant growth regulators, ethylene and cytokinins, are definitely involved in both petal and leaf senescence in some species. The sensitivity of petal senescence to endogenously produced, or exogenously applied, ethylene is species specific, and species can be broadly divided into those in which petal senescence is ethylene sensitive and those in which it is not (Rogers, 2006). In carnation (Dianthus caryophyllus), an ethylene-sensitive species, ethylene production and ethylene biosynthetic genes are both up-regulated in petals late during the vase life of the flower (ten Have and Woltering 1997). In leaves, as in flowers, ethylene sensitivity is related to the age of the organ; however, in general, the role of ethylene in leaf senescence is less central (Grbić and Bleecker, 1995). Up-regulation of cytokinins delays both leaf (Gan and Amasino, 1995) and petal (Chang et al., 2003) senescence, and it has been suggested that a fall in cytokinins may trigger an increase in ethylene sensitivity during petal senescence in unpollinated ethylene-sensitive species (van Doorn and Woltering, 2008). Other plant growth regulators are probably also involved, but the signaling pathways and their cross talk are poorly understood. Transcriptional regulation of senescence in both leaves and petals is also complex and as yet not fully understood. Transcription factors that are up-regulated during leaf senescence, such as WRKY53 (Hinderhofer and Zentgraf, 2001) and many others, have been identified (Buchanan Wollaston et al., 2005), but as yet their interactions have not been fully elucidated. Similarly, transcription factors up-regulated during petal senescence have been identified in several genera (Alstroemeria [Breeze et al., 2004] and Iris [van Doorn et al., 2003]) but not fully characterized.

Global transcriptomic and EST analyses have probed senescence independently in leaves in Arabidopsis (Gepstein et al., 2003; Buchanan-Wollaston et al., 2005) and petals (in Alstroemeria [Breeze et al., 2004], Iris [van Doorn et al., 2003], and Rosa [Channeliere et al., 2002]); however, to date there is a lack of comparisons of leaf and petal senescence transcriptomes in the same species. Wallflower (Erysimum linifolium) is a useful ornamental species in which to compare leaf and petal senescence. It is closely related taxonomically to Arabidopsis (Stevens, 2001) but has larger pigmented flowers whose development and senescence are easily staged. Thus, in the study presented here, the objectives were (1) to use microarray analysis of subtractive libraries from wallflower leaves and petals to compare the global gene expression changes occurring during senescence in these two tissues and relate these to changes in the physiology of the two organs during senescence and (2) to take advantage of the close taxonomic relationship between wallflower and Arabidopsis to compare and contrast expression patterns between the two species in the two tissues and reveal species-specific or tissue-specific differences in the senescence program.

RESULTS

Physiology of Leaf and Petal Senescence in Wallflower

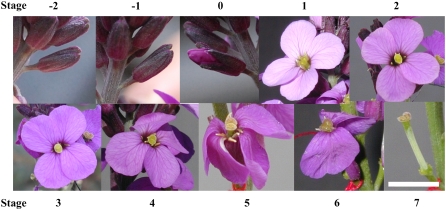

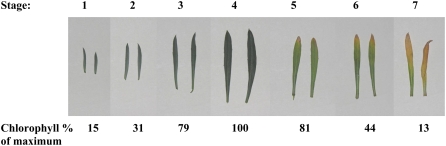

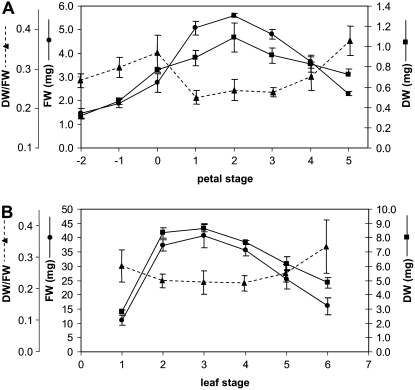

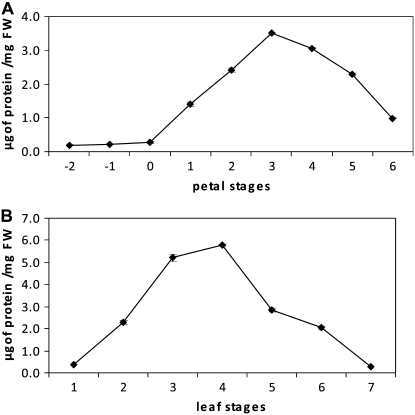

One flower on the wallflower raceme opened each day, taking 7 d to complete its development from bud opening to full abscission of the calyx, corolla, and androecium (Fig. 1). Thus, eight stages of development were assigned based on number of days after opening. Stage 0 was defined as the lowest unopened bud; additional early bud stages were designated stages −1 and −2. No difference in morphology or in rate of development was noted for the flowers at different times of year. Stage 4 was the stage at which the first signs of visible petal deterioration became evident. Leaves could be characterized within one whorl and were assigned to seven developmental groups based on relative size and chlorophyll content (Fig. 2). At stage 5, leaves showed the first signs of yellowing, indicating senescence, and this corresponded with a 20% reduction in chlorophyll levels. Dry weight-fresh weight ratio and total protein content were also determined for each developmental stage of petals and leaves (Figs. 3 and 4). There was a sharp reduction in dry weight-fresh weight ratio between petal stages 0 and 1, coinciding with flower opening, followed by a rise starting from stage 4 as petals lost turgor. Protein loss started after stage 3, coincident with the first signs of petal deterioration. In leaves, the dry weight-fresh weight ratio started to rise after stage 5, while protein loss started after stage 4, again preceding the start of visual signs of senescence.

Figure 1.

Stages of wallflower flower development. Stage −2 and stage −1, Two sequential buds below the lowest unopened bud on the raceme. Sepals completely cover petals. Stage 0, Lowest unopened bud on raceme. Petals are dark purple in color, tightly curled within sepals. Stage 1, Flower fully opened. Petals are pale purple, with sepals folded back midway along their length. Stigma is yellow and fuzzy in appearance, four of six anthers are visible, all undehisced, positioned close to the stigma with the tips curled over the stigma. Stage 2, As stage 1, but petals are darker in color. All six anthers are visible, two newly emerged anthers are dehisced and curled back from the stigma. Stage 3, The flower is not as tightly held together as previously. Petals are wilting slightly and darker again in color. Fuzz on stigma is not as fine as previously. All six anthers are dehisced and curled back from the stigma. Stage 4, The flower is loosely held together. Petals are limp and curled over at the tips. Flower appearance has deteriorated. Stage 5, As stage 4, but more extreme. Petals are wilted, stigma is discolored with dark purple areas. Stage 6, Sepals, petals, and stamens are beginning to abscise. Remaining petals look withered and dry. Stage 7, All sepals, petals, and stamens are abscised; only the stigma remains. Bar = 10 mm.

Figure 2.

Stages of wallflower leaf development. Stage 1, Very young leaves, less than 50% expanded. Stage 2, Very young leaves, 50% to 75% expanded. Stage 3, Young leaves, 75% to 100% expanded. Stage 4, Mature green leaves. Stage 5, Older mature leaves, green with signs of yellowing on the tip. Stage 6, Old leaves, up to 50% of leaf area yellow. Stage 7, Very old leaves, mostly or all yellow. Below each image is the total chlorophyll for that leaf stage expressed as a percentage of maximum.

Figure 3.

Fresh weight (FW), dry weight (DW), and ratio of dry weight to fresh weight during petal (A) and leaf (B) development and senescence. Dry weight was determined by drying 20 to 100 petals or leaves at 60°C for 5 d. Error bars represent ± se (n = 3).

Figure 4.

Total protein content of petals (A) and leaves (B). Error bars represent ± se (n = 15).

Due to the close taxonomic relationship between wallflower and Arabidopsis, it seemed likely that ethylene would be an important regulator of petal senescence in this species too. In ethylene-sensitive species, treatment with a pulse of an ethylene inhibitor such as silver thiosulfate (STS) delays flower senescence (Serek et al., 1995). In wallflower, detached flowers harvested at stage 1 and held in water senesced over the same period as attached flowers, with full abscission on day 7. However, when pulsed for 1 h with STS on the day of harvest, abscission was delayed by 2 d. STS-pulsed flowers also senesced more slowly, taking 4 d to progress from stage 3 to stage 5, instead of 2 d when held in water. Given that in ethylene-sensitive species, such as carnation, cytokinins are also implicated in petal senescence (Taverner et al., 2000), the role of cytokinins in wallflower was tested. Treatment with either 0.1 or 1.0 mm kinetin or with 0.1 mm 6-methyl purine (an inhibitor of cytokinin oxidase) delayed senescence and abscission of flowers harvested at stage 1 by 2 d (Supplemental Figs. S1 and S2).

Construction of Wallflower Petal and Leaf Subtracted Libraries and Screening by Microarray Analysis

Based on the physiological characterization of leaf and petal senescence, subtracted libraries were constructed for use in transcriptomic analysis to identify genes whose expression is up-regulated during the senescence of these two organs. For this purpose, petals from stages −2, −1, and 0 (early to mature buds) were combined to represent young petals, and petals from stages 3, 4, and 5 (early to late visible signs of petal wilting) were combined to represent old petals. Leaf stage 3 (75%–100% expansion, 80% chlorophyll) was used to represent young leaves that had not yet reached their full photosynthetic capability, and stages 5 and 6 (early to later stages of leaf yellowing, in which chlorophyll levels had fallen to 81% and 44% of maximum, respectively) were combined to represent old leaves. A total of 1,018 and 614 clones for leaves and petals, respectively, were obtained from the subtraction. PCR-amplified inserts from all 1,632 clones from the subtracted libraries were used to generate a cDNA microarray, and 431 probes showed a consistent expression pattern with both pairs of labeled RNA when analyzed using GeneSpring software. The results from the microarray analysis are summarized in Supplemental Table S1. Two fragments representing known genes WLS63 and WPC11A were spotted in three replicate dilutions (36 data points) and showed very similar changes in expression with low variability between replicates (for WLS63, leaves down, 1.1 ± 0.2 [values are mean fold ± se], petals up, 3.8 ± 0.4; for WPC11A, leaves up, 10 ± 1.0, petals up, 136 ± 27), indicating the reproducibility of the array results.

Six of the possible nine classes of expression (i.e. up-regulated in both old petals and old leaves compared with the young tissue, up-regulated in petals but unchanging in leaves, up-regulated in petals but down-regulated in leaves, etc.) were represented in the microarrays (Table I). Of the 427 probes (excluding the replicates described above), expression of 305 probes was up-regulated reproducibly in old petals compared with young petals. Of these, the expression of 232 probes was up-regulated in both old organs, while the expression of 61 probes was up-regulated in old petals but remained stable in leaves, and the expression of a further 12 probes was up-regulated in petals with age but was down-regulated in old leaves. As expected from the enrichment of the genes by suppression subtractive hybridization (SSH), the majority of probes on the array indicated up-regulated expression with senescence in the tissue from which they were derived, confirming that the subtraction of the SSH libraries was effective. Of 164 probes from the petal cDNA library, whose expression could be reliably determined in both tissues, the expression of 98% was up-regulated with age in petals. For 263 probes derived from the leaf cDNA library, 52% showed up-regulated expression with age in leaves, although larger numbers of leaf-derived probes on the array were stable in expression with leaf senescence (47%; Supplemental Table S1).

Table I.

Expression classes from microarray analysis

| Petal Unchanged | Petal Down-Regulated | Petal Up-Regulated | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leaf unchanged | 103 | 0 | 61 |

| Leaf down-regulated | 1 | 0 | 12 |

| Leaf up-regulated | 18 | 0 | 232 |

Sequence Analysis of Wallflower Genes from the SSH Libraries

Following microarray analysis, fragments representing selected probes on the array were chosen for sequencing to represent the different classes of gene expression presented in Table I. In addition, a random selection of clones from the SSH libraries were also sequenced. Once poor and short sequences had been removed, 210 ESTs were obtained (GenBank accession numbers are listed in Supplemental Table S1) and 127 of the sequences clustered into 27 contigs (WC1–WC27), with the largest contig containing 28 sequences (Table II). The remaining 83 sequences were singletons (i.e. represented only once). Thus, the redundancy (number of sequences clustered divided by the total number of sequences; Breeze et al., 2004) of the EST collection was 60% (which means that the chance of finding the same sequence again in any new clones sequenced is 60%). However, there may be further redundancy due to nonoverlapping fragments of the same gene. Genes within contigs were given codes: WLC (Wallflower Leaf Contig) and WPC (Wallflower Petal Contig), and singletons were denoted WLS and WPS. Contigs are hereafter referred to in the form WC1 (Supplemental Table S1). Putative gene functions were assigned based on a BLAST search, and in most cases the closest match was to Arabidopsis genes, as wallflower is of the same subfamily (Brassicoideae; Stevens, 2001). In total, 193 wallflower sequences could be assigned to a closely matching Arabidopsis gene, and 73 Arabidopsis genes were identified as the closest match. Analysis of gene functions revealed that three contigs (WC4, WC5, and WC26, comprising altogether 26 sequences) and four further sequences that did not overlap the contigs, amounting to 14% of the sequences, matched SAG12. Three contigs (WC1, WC2, and WC16, comprising 25 sequences) matched nonoverlapping regions of the same chitinase gene (At2g43570), and a fourth contig (WC3 of three sequences) matched most closely a different chitinase gene (At4g19810). Thus, 13% of the sequences represented chitinase-like genes. A further 7% of the sequences matched glutathione S-transferases (GSTs), 7% matched metallothioneins, and 4% matched a lipid transfer protein.

Table II.

Most abundant sequenced transcripts from the SSH libraries

| Arabidopsis Genome Initiative Code for Closest Arabidopsis Match | Wallflower Contig | No. of Clones | Putative Function/Closest Arabidopsis Homolog | Functional Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| At2g43570 | WC1 | 28 | Chitinase class IV | Stress/defense |

| At5g45890 | WC4 | 26 | SAG12 | Remobilization |

| At1g07600 | WC24 | 13 | Metallothionein | Metal binding |

| At2g02930 | WC10 | 10 | ATGSTF3 | Defense |

| At3g22600 | WC6 | 9 | Lipid transfer protein | Remobilization |

| At2g43570 | WC2 | 9 | Chitinase class IV | Stress/defense |

| At1g32450 | WC11 | 5 | Peptide transporter | Remobilization |

| At3g22600 | WC7 | 5 | Lipid transfer protein | Remobilization |

| At5g01600 | WC17 | 4 | Ferretin | Metal binding |

| At2g23790 | WC8 | 3 | Unknown protein | Unknown |

| At2g45570 | WC14 | 3 | Cytochrome P450 | ROS/stress |

| At1g73260 | WC15 | 3 | Endopeptidase inhibitor | Remobilization |

| – | WC18 | 3 | No hits | – |

| At4g19810 | WC3 | 2 | Chitinase | Stress/defense |

| At1g11190 | WC9 | 2 | Bifunctional nuclease | Remobilization |

| At4g02520 | WC10 | 2 | ATGSTF2 | Defense |

| At5g02040 | WC13 | 2 | Rab acceptor | Signaling |

| At5g01220 | WC19 | 2 | Unknown protein | Unknown |

| At1g05560 | WC20 | 2 | UDP glycosyl transferase | ROS/stress |

| At2g02390 | WC21 | 2 | ATGSTZ1 | Defense |

| At5g40690 | WC22 | 2 | Unknown protein | Unknown |

| At2g45220 | WC23 | 2 | Pectin esterase inhibitor | Remobilization |

| At5g45890 | WC5 | 2 | SAG12 | Remobilization |

| – | WC12 | 2 | No hits | – |

| At2g43570 | WC16 | 2 | Chitinase class IV | Stress/defense |

| At1g07600 | WC25 | 2 | Metallothionein | Metal binding |

| At5g45890 | WC26 | 2 | SAG12 | Remobilization |

Representation of the Functional Categories in the Different Expression Classes

There was a striking difference in the representation of putative functional categories between the different gene expression classes on the microarray (Fig. 5). Sequences were obtained for 75% of the probes on the microarray whose expression was up-regulated in senescent petals and was either unchanged or down-regulated in senescent leaves. Over one-third of these sequences (40%) were related to chitinases. The majority of these chitinase-related sequences (20) were most closely related to an Arabidopsis class IV chitinase (At2g43570; contigs WC1 and WC2), while one was more closely related to an Arabidopsis family 18 glycosyl hydrolase (At4g19810; contig WC3); both Arabidopsis genes are putatively involved in cell wall metabolism.

Figure 5.

Putative functional classes of wallflower genes from different microarray expression classes. Comparison of putative functional classes of genes represented in two expression categories from the microarray analysis. A, Up-regulated in senescent petal but either stably expressed or down-regulated in senescent leaf. B, Up-regulated in both senescent petal and senescent leaf. Functional classes were derived from Gene Ontogeny annotations and from putative functions based on sequence homology.

A further 23% of the sequences from this array expression class (up-regulated in old petals, either unchanged or down-regulated in senescent leaves) showed homology to GSTs. All of the 10 sequenced probes that were up-regulated in senescent petals but down-regulated in senescent leaves showed closest homology to the φ class of GSTs (Wagner et al., 2002), and nine were assigned to one contig (WC10). All the WC10 sequences were closest to AtGSTF3, while the singleton sequence was closer to AtGSTF7. However, as all of the clones were partial, it is difficult to assign the sequences unambiguously to an Arabidopsis homolog, as a key diagnostic triplet of amino acids at positions 66 to 68 relative to AtGSTF2 (Wagner et al., 2002) was not included in the wallflower clones and, in addition, AtGSTF3 and AtGSTF2 were 95% identical. All of the GST-related probes in this expression class showed similar expression patterns on the microarray (leaf, 0.35 ± 0.02 [values are mean fold ± se]; petal, 15.3 ± 1.69). The expression of two further probes on the microarray whose sequence showed homology to GSTs was up-regulated in senescent petals but was stable in senescent leaves (leaf, 1.5 ± 0.23; petal, 4.3 ± 0.09). These sequences formed a separate contig (WC21) showing closest homology to AtGSTZ1. The remainder of the sequenced probes on the microarray, for which putative functions could be ascribed and whose expression was up-regulated in senescent petals but stable in senescent leaves, represented metal-binding proteins (one probe), proteins associated with ROS/stress (five probes) or signaling (five probes), proteins involved in remobilization/metabolism (three probes), and one gene involved in mRNA stability. The metal-binding protein was a putative copper chaperone most closely homologous to CCH/ATX1 that is thought to play a role in remobilization of copper from metalloprotein degradation (Himelblau and Amasino, 2000) and was 4-fold up-regulated in petals. ROS/stress-related proteins include a PR5-like protein (petals, up-regulated by 6.3-fold), a cytosolic thioredoxin (petals, up-regulated by 3.0-fold), SAG21 (petals, up-regulated by 5.7-fold), and a cytochrome P450 family protein (petals, up-regulated by 23.3-fold). Signaling proteins include a rhodopsin-like receptor (petals, up-regulated by 2.9-fold), a Rab acceptor (petals, up-regulated by 7.5-fold), and a Rab subfamily GTPase (petals, up-regulated by 2.3-fold). Finding genes encoding proteins involved in remobilization is not surprising, although genes whose role may be specific to remobilization in petals and not leaves may be significant in defining the difference between remobilization in the two organs. The three up-regulated genes identified here were a lipid transfer protein (leaves, 1.59-fold; petals, 5.14-fold), a thiol protease (leaves, 1.41-fold; petals, 2.77-fold), and a AAA-type ATPase family protein (leaves, 1.51-fold; petals, 4.95-fold). Only one gene involved in the regulation of gene expression and up-regulated only in petal senescence was identified, and it showed homology to CCR4-related proteins (WLS63, three replicates on the array; leaf, 0.88 ± 0.15; petal, 3.8 ± 0.43). CCR4-NOT proteins in yeast are involved in the regulation of gene expression via mRNA stability (Chen et al., 2002).

In contrast, of those probes that were up-regulated in both senescent leaves and petals and for which meaningful sequence was obtained, the highest proportion (23%) was represented by SAG12, while chitinase genes represented only 5% and no GST genes were up-regulated in both tissues (Fig. 5). The expression of all of the SAG12 probes was reliably determined from the microarray, and all were up-regulated in both leaves and petals, although more strongly in petals (leaves, 95 ± 17; petals, 216 ± 35). A lower proportion of the sequences in this expression class, compared with those that were only up-regulated in petals with age, related to signaling and included three genes with putative functions in auxin responses, one in cytokinin responses, and one in ethylene synthesis. The expression of all of these genes with putative roles in signaling was more highly up-regulated with age in petals than in leaves. Three sequences were homologous to transcriptional regulators, and the expression of these genes was also more highly up-regulated in aging petals compared with leaves: a WRKY75 transcription factor (At5g13080) and two members of the plant-specific NAC family of transcription factors (At2g33480 and At5g64530).

The expression of only a few probes (18) was up-regulated in senescent leaves while remaining unchanged in petals. Sequences were obtained for seven of these: four were putative ferretin genes (leaf, 3.6 ± 1.7), while the rest were of unknown function (Supplemental Table S1).

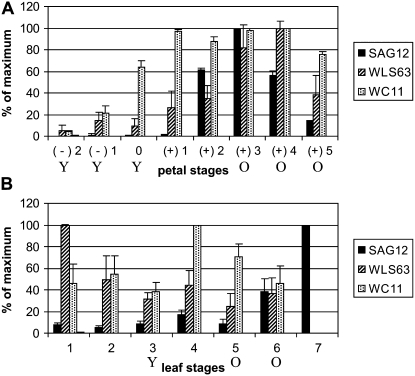

Semiquantitative Reverse Transcription-PCR of Selected Wallflower Genes

Genes were selected for semiquantitative reverse transcription (RT)-PCR based on their putative function and results from the microarray experiments, to confirm the validity of the arrays and also to determine more precise timing of expression for selected genes of interest. SAG12 was selected as it represented a high proportion of probes whose expression was up-regulated in both old leaves and petals (Supplemental Table S1). Semiquantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 6) showed that the expression of SAG12 remained low in leaves until stage 6, at which point chlorophyll levels were reduced to 44% of maximum and protein levels to 35% of maximum. Expression then increased significantly in stage 6 leaves, reaching a maximum at the oldest stage used in the RT-PCR, stage 7. At this stage, both the protein and chlorophyll levels had decreased to less than one-quarter of their maximum. In petals, however, although SAG12 expression was very low in buds and young open flowers, it was already substantially up-regulated in mature, stage 2 flowers, at which time protein levels, fresh weight, and dry weight were at or close to their maximum. Thereafter, SAG12 levels in petals fell until by stage 5 they were less than 20% of the maximum value.

Figure 6.

RT-PCR of selected genes from the SSH libraries. Semiquantitative RT-PCR over petal (A) and leaf (B), young (Y) and old (O) stages as defined in the text, expressed as percentage of maximum value ± se (n ≥ 3) for SAG12, WLS63, and WC11. Note that data for WLS63 and WC11 expression levels for stage 7 leaves were not determined.

Two additional genes were selected: first, the CCR4-like protein (WLS63), and second, a gene with a putative role in remobilization, a peptide transporter (WC11). On the array, expression of WLS63 was up-regulated only in petals with age, while the expression of WC11 was up-regulated in both, although to a much greater extent in petals. In both cases, the expression pattern from semiquantitative RT-PCR was consistent with the array data, but a better resolution was obtained from the RT-PCR due to the larger number of separate tissue stages used. This revealed a more complex pattern than was evident from the arrays in which pooled tissue stages were used (Fig. 6). Thus, although WLS63 expression was low in stage 3 leaves, selected to represent young tissue, and remained low as leaves aged, the highest levels of expression were early in leaf development at stage 1. In petals, expression reached a maximum before the final stages of petal senescence, at stage 4. WC11 expression fluctuated during leaf age, being already high in young leaves and reaching a peak at stage 4, when fresh weight, dry weight, protein levels, and chlorophyll levels were maximal, falling thereafter. Its expression in petals was very low in young buds (stages −2 and −1) but increased already to 60% of maximum from stage 0, when the buds were not yet open. It reached a maximum expression level at stage 1 (young open flowers) and remained high until it dropped slightly in late senescence (stage 5).

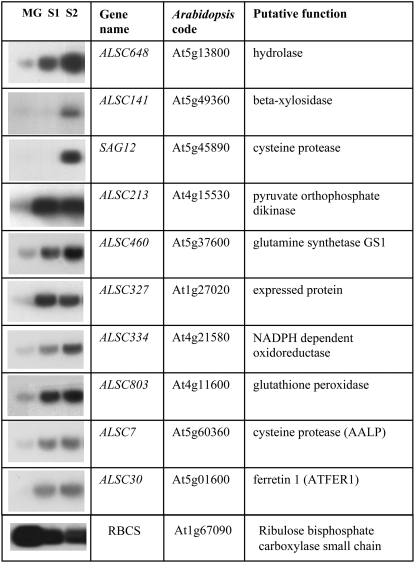

Use of Arabidopsis Gene Probes in Cross-Species Microarray Analysis and Comparisons with Arabidopsis Gene Chip Data

In addition to the wallflower probes, 91 Arabidopsis probes were also printed onto the arrays. Many of these Arabidopsis sequences were selected as genes whose expression was already known to change with leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Expression patterns of 52 of these genes in wallflower petals and leaves were reliably detected on the arrays for both tissues. Gene expression patterns in Arabidopsis mature green leaves (MG, analogous to wallflower stage 4 leaves) and two stages of leaf senescence (S1, between stage 4 and stage 5, and S2, between stage 5 and stage 6 of wallflower leaf senescence) of 10 of these genes were verified by northern analysis (Fig. 7), showing a range of expression patterns. Data on the expression of all of the Arabidopsis genes was also obtained from AtGenExpress (Supplemental Table S2). Leaf and petal stages were chosen to resemble most closely the stages used for the wallflower SSH and arrays. All four data sets for young/old leaves and petals were obtained from the Weigel laboratory experiments (Schmid et al., 2005). Senescing leaves (from 6-week-old Arabidopsis plants), corresponding to stage 5 to 6 wallflower leaves, were compared with leaf 8 (from 4-week-old Arabidopsis plants), which is not fully expanded and thus resembles wallflower leaf stage 3. For petals, petal stage 15 (Smyth et al., 1990), which equates to stage 3 wallflower petals, was compared with stage 12 petals (unopened bud, nondehisced), comparable to stage 0 in wallflower. Comparing the northern expression data with the Weigel laboratory array data indicated that the senescing leaf material used in the arrays included leaves at the same stage as the S2 of the northern blots, since in Arabidopsis, SAG12 expression was only detected late in senescence. Expression patterns of nine of the 10 genes for which northern data are presented here were detected on the Affymetrix Weigel arrays, and eight of them showed increased gene expression in senescent leaves by both methods. In the case of LSC141 (At5g49360), Affymetrix array expression was strong in both leaf stages (means, stage 8, 513; senescing, 799); however, the increase in expression (leaf, 1.6-fold) was below a 2-fold threshold.

Figure 7.

Northern analysis of 10 Arabidopsis genes represented on the microarrays. MG represents mature Arabidopsis green leaf with maximum chlorophyll levels (100%); S1 and S2 are stages of Arabidopsis leaf senescence with 98% and 60% chlorophyll levels, respectively (Buchanan-Wollaston and Ainsworth, 1997).

For 47 Arabidopsis genes, data were available from both the Affymetrix Arabidopsis arrays and the wallflower arrays. Of these, 81% (38 genes) showed the same pattern of expression in at least one tissue in both species and 38% (18 genes) showed the same pattern in both tissues in both species. The expression of five genes, 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) oxidase, catalase, blue copper-binding protein, SAG21, and an unknown protein that is strongly induced by brassinolide (At2g38640), was unchanged in leaves but up-regulated in senescent petals of both species. Ferretin was up-regulated in senescing leaf but not petal tissue of both species, while six genes, histone H1-3, a hydrolase, a Cys protease, an RNase, SAG12, and xyloglucan transferase, were up-regulated in both petals and leaves of both species. The remainder were unchanged with age in both tissues of both species. Ten genes were up-regulated in both petals and leaves with age in Arabidopsis but only in petals in wallflower. These were cytochrome P450, copper homeostasis factor, POP dikinase, NADPH-dependent oxidoreductase, Gln synthetase, two Cys proteases, alcohol dehydrogenases, ERD1, and an unknown protein. Conversely, xylosidase and β-glucosidase were up-regulated in both wallflower tissues with age but only in one of the two tissues in Arabidopsis.

Affymetrix data, from the Weigel data sets (Schmid et al., 2005) described above, were available for 61 of the 73 genes identified as the closest hits to the sequenced wallflower genes on the wallflower array (Supplemental Table S2). Of these, six genes were included in the 52 Arabidopsis genes discussed above. Thus, data were available from all three combinations, enabling a three-way comparison of the expression of the Arabidopsis gene and wallflower gene when probed with the wallflower transcripts and the Arabidopsis gene expression pattern on the Arabidopsis Affymetrix arrays (the At codes for these genes are shown in boldface in Supplemental Table S2). For three genes (SAG12, up-regulated in both petals and leaves; ferretin, up-regulated only in leaf; SAG21, up-regulated only in petals) there was exact correspondence; for another two genes (a cytochrome P450 and a copper homeostasis factor gene) the expression pattern was in broad agreement, although with the wallflower probe the leaf signal was below the threshold for an up-regulated response; finally, a xylosidase gene (At5g49360) was up-regulated only in petals on the Affymetrix array while it was stable in leaves. This result, however, contrasts with the northern analysis for this gene (Fig. 7), which showed a clear up-regulation of expression in the later stages of leaf senescence. The data from the Arabidopsis gene on the wallflower array hybridized to wallflower transcripts, and for the wallflower homolog WLS27, were in better agreement with the northern data, showing up-regulation of expression with age in both tissues.

Of the 61 sequenced wallflower probes that matched Arabidopsis genes and for which Affymetrix expression data were available for senescent leaves and petals from the Weigel data, 85% shared the same expression pattern with their Arabidopsis homolog in at least one of the two tissues and 53% shared the same expression pattern in both tissues. However, there were some notable differences in those genes that were particularly abundant in the wallflower array or that are of interest because of potential roles in signaling or regulation (Supplemental Table S2). Thus, expression of the major class of chitinase genes (WC1/2/16 in Supplemental Table S2, which is the mean of contigs WC1, WC2, and WC16) on the wallflower array was strongly up-regulated with age in wallflower petals (mean, 36-fold) but not in leaves. However, in Arabidopsis, expression of the homolog (At2g43570) on the Affymetrix arrays was strongly up-regulated in both tissues (leaves, 10.1-fold; petals, 4.8-fold). Expression of the largest group of wallflower GST sequences (WC10, mean of contig WC10 on Supplemental Table S2) homologous to Arabidopsis AtGSTF3 (At2g02930) was strongly up-regulated in senescent wallflower petals (16.5-fold) but down-regulated in senescent wallflower leaves. Expression of Arabidopsis AtGSTF3 on the Affymetrix arrays showed a similar pattern, with up-regulation in petals with age (2.7-fold) but no change in leaves. However, two of the wallflower sequences (WC21, mean of contig WC21 in Supplemental Table S2) showed closest homology to AtGSTZ1 (At2g02390). Expression of these wallflower probes was up-regulated strongly in senescent wallflower petals (4.3-fold) but was only very mildly up-regulated in leaves (1.5-fold). Expression of Arabidopsis AtGSTZ1 on the Affymetrix arrays was strongly up-regulated in both leaves (4.9-fold) and petals (6-fold).

Four genes with potential roles in signaling differed in expression patterns between Arabidopsis and wallflower. Although expression of the three genes relating to auxin signaling (WPS46, WPS103, and WPS53 in Supplemental Table S2) was up-regulated with age in both tissues of both species, expression of a putative cytokinin oxidase (wallflower probe, WPS96; Arabidopsis gene, At1g75450) was strongly up-regulated in Arabidopsis leaf (8.5-fold) but only very weakly in petals (1.5-fold) on the Affymetrix arrays. In contrast, the wallflower homolog (WPS96 in Supplemental Table S2) was strongly up-regulated in both wallflower tissues (leaves, 5.8-fold; petals, 8.9-fold). Two sequences relating to Rab signaling were identified from the wallflower libraries. Expression of a wallflower Rab acceptor homolog, WLC13A (Supplemental Table S2), was strongly up-regulated in old wallflower petals (7.5-fold) but only very weakly in old wallflower leaves (1.6-fold). In contrast, expression of the closest Arabidopsis homolog, At5g02040, was up-regulated in old leaves (2.3-fold) but was stable with age in petals on the Affymetrix arrays. Expression of the second Rab-related wallflower sequence (WPS55 in Supplemental Table S2), a putative member of the Rab small GTPases, was weakly up-regulated in old wallflower petals (2.3-fold) but was stable in wallflower leaves. However, the Arabidopsis homolog (At1g49300) was stable with age in both Arabidopsis petals and leaves on the Affymetrix arrays. Finally, a putative rhodopsin-like receptor gene also differed in expression pattern in the two species. Expression of the Arabidopsis gene (At1g12810) was up-regulated in both tissues (leaves, 2.8-fold; petals, 2.1-fold) on the Affymetrix arrays, while the wallflower homolog (WPS95 in Supplemental Table S2) was only up-regulated in old wallflower petals (2.9-fold) but not in old leaves.

Four transcription factors were also identified on the wallflower arrays. Expression of a WRKY75 homolog (WLS67) and two members of the No Apical Meristem (NAM) family (WPS52 and WLS62) was up-regulated in both tissues in both species (Supplemental Table S2). Expression of the Arabidopsis homolog of the WRKY75 transcription factor (At5g13080) was up-regulated much more strongly in old leaves compared with old petals (leaves, 202-fold; petals, 13.8-fold) on the Affymetrix arrays, whereas the expression pattern of its wallflower homolog, WLS67, was reversed, with much stronger up-regulation in old wallflower petals (67-fold) compared with old wallflower leaves (7-fold). There was a similar contrast in pattern for one of the NAM family transcription factors (At5g64530/WLS62 in Supplemental Table S2). Expression of this gene was much more highly up-regulated in old petals compared with old leaves in wallflower (leaves, 2.2-fold; petals, 22-fold), while on the Arabidopsis Affymetrix arrays the pattern was reversed (leaves, 4.3-fold; petals, 2-fold). Finally, expression of a CCR4 family protein (WLS63 in Supplemental Table S2) was up-regulated in both aging Arabidopsis leaves and petals (leaves, 2.8-fold; petals, 4.0-fold) on the Affymetrix arrays, while in wallflower it was only up-regulated in petals with age (3.7-fold) and stable in leaves.

DISCUSSION

Remobilization during Petal and Leaf Senescence in Wallflower

Species can be broadly divided into those in which petals wilt before abscission and those in which petals abscise at full turgor (van Doorn and Stead, 1997). Generally, the longer the petals persist, the more remobilization of nutrients is likely to occur. Patterns of dry weight-fresh weight ratio changes during wallflower petal senescence are consistent with data from other genera, such as Alstroemeria and Tulipa (Collier, 1997), Hemerocallis (Lay Yee et al., 1992), Digitalis (Stead and Moore, 1977), and Sandersonia (Eason and Webster, 1995), in which some wilting occurs before abscission. However, in wallflower, the magnitude of change between the maximal values of open flowers and heavily wilted flowers is quite low (at stage 5, fresh weight and dry weight are 41% and 67%, respectively, of the maximum) compared with Hemerocallis, in which fresh weight decreases to 2% of maximum and dry weight decreases to 33% of maximum. The change, however, is greater than in Digitalis (dry weight remains at 88% of maximum) or Alstroemeria (dry weight remains at 80% and fresh weight at 40% of maximum). Thus, wallflower petals appear to be more similar to Alstroemeria in their loss of fresh weight (40% of maximum in Alstroemeria) but closer to Tulipa in the loss of dry weight (60% of maximum in Tulipa). This indicates a flower in which there is substantial, but not extreme, wilting before petal abscission and in which some remobilization is probably taking place. This is supported by the array results: a large proportion of the sequenced genes that were up-regulated in senescent wallflower petals related to remobilization (38% overall). This is in agreement with transcriptomic studies of petals from other species in which wilting occurs (Alstroemeria [Breeze et al., 2004] and Iris [van Doorn et al., 2003]). The vast majority of genes related to remobilization were up-regulated in both senescent petals and leaves, and the largest proportion of the genes whose expression was up-regulated with age in both tissues were putatively involved in remobilization. Including SAG12, these represent just over half of the genes in this category. Again, this agrees with other transcriptomic studies of leaves (Guo et al., 2004; Buchanan-Wollaston et al., 2005) and petals (van Doorn et al., 2003; Breeze et al., 2004). All of the SAG12 targets belonged to this expression class as expected, and metal-binding proteins were also well represented, again reflecting other studies discussed above. However, three genes related to remobilization were specifically up-regulated in wallflower petals and not leaves, a AAA-type ATPase family protein, a lipid transferase, and a thiol protease. These may be interesting genes to study further.

While the process of remobilization, and many of the genes involved, are shared between petals and leaves in wallflower, the timing of both physiological events and gene expression in the two organs differs. Whereas in petals the dry weight-fresh weight ratio was rising well before any visible signs of wilting, in leaves the first signs of visible senescence, and the drop from maximal chlorophyll levels, coincided with the start of the rise in dry weight-fresh weight ratio. The loss of both fresh weight and dry weight was comparable between petals and leaves; however, the extent of protein breakdown differed, with 65% of the maximal level of protein remaining in petals by stage 5 compared with only 5% in stage 7 leaves. The fall in leaf protein coincided with chlorophyll degradation, reflecting the fact that the majority of remobilized protein from leaves is from chloroplasts (Thomas and Donnison, 2000). The precise timing of SAG12 expression also differed between the two organs when examined more closely by RT-PCR. The leaf data are in agreement with data from Arabidopsis (Lohman et al., 1994), with up-regulation of SAG12 late in senescence. However, in petals, SAG12 is already substantially up-regulated in mature nonsenescent flowers and falls to less than 20% of maximal levels by late senescence. SAG12 encodes a papain-like Cys protease located in senescence-associated vacuoles. It is presumed to play a role in proteolysis; however, sag12 knockouts are not perturbed in their leaf senescence (Otegui et al., 2005). Assuming that the role of SAG12 is equivalent in petals and leaves, the different expression programs could reflect different patterns of cellular degradation. Electron microscopy of petals reveals very early cellular death in much of the mesophyll while the epidermal cells remain intact (Weston and Pyke, 1999; Wagstaff et al., 2003). Hence, perhaps the majority of SAG12 activity is already complete in many petal cells at a relatively earlier stage of organ senescence. The temporal difference in expression patterns in different cell types is something that array experiments often overlook, and it is only with laser dissection microscopy, or other single cell-based PCR techniques, that these differences will be elucidated.

The expression of another gene with a presumed role in remobilization, WC11, encoding a putative peptide transporter, was also examined by RT-PCR, and the expression pattern of this gene also differs between the two organs. Although WC11 expression is strongly up-regulated according to the array during both petal and leaf senescence, RT-PCR shows that the pattern is more complex. It was expressed from young leaves through to mature leaves, with increased expression early in senescence. In contrast in petals, there is a clear up-regulation that precedes other signs of senescence, and expression remains high. Peptide transporters form a superfamily of structurally related membrane proteins (Chiang et al., 2004). Different members of the Arabidopsis gene family show tissue-specific expression. The closest Arabidopsis gene to WC11, At1g32450, is part of the PTR family, transporting dipeptides and tripeptides (Waterworth and Bray, 2006), although it does not fall into one of the major subfamilies. The Arabidopsis gene is expressed in mature tissues and is strongly up-regulated in leaf senescence (Affymetrix data from Genevestigator). Hence, this gene may have a function both during leaf development and during the remobilization occurring during leaf senescence. In petals, the role may be different, in that expression during early development is very low and there is a far greater up-regulation during senescence, indicating a more specific role in senescence-associated remobilization.

Regulation of Wallflower Petal and Leaf Senescence

Pulse treatment of cut flowers with STS indicated that ethylene is involved in both petal senescence and abscission in this species. It was a surprise, therefore, not to find more genes related to ethylene biosynthesis or responses in the petal SSH library. In fact, only one ACC oxidase-like gene was found. This gene, however, was strongly up-regulated in both senescent leaves and petals, as expected. In addition, Arabidopsis ACC oxidase on the array was up-regulated 3-fold when hybridized to messages from wallflower petals. Many of the SSH library genes represented 3′ untranslated region sequences and were thus difficult to annotate; therefore, it seems likely that further ethylene-related genes are up-regulated in both leaf and petal wallflower senescence but were not identified as such.

Treatment with cytokinin (kinetin) delayed both petal senescence and abscission, as did treatment with the inhibitor of cytokinin oxidase, 6-methyl purine. A cytokinin oxidase gene (At1g75450, WPS96), was strongly up-regulated in old petals in wallflower (9-fold). Thus, part of the mechanism for the regulation of petal senescence in wallflower may be a reduction in cytokinin levels via cytokinin oxidase. In carnation (Dianthus caryophyllus) petals, sensitivity to ethylene of excised petals was reduced by exogenous application of cytokinin (Taverner et al., 2000), indicating cross talk between these two growth regulators, which is worthy of further investigation in wallflower. The Arabidopsis cytokinin oxidase gene, At1g75450, was only very weakly up-regulated in petals (1.5-fold) on the Affymetrix arrays, whereas up-regulation in leaves was much more significant (8.5-fold). This could indicate either temporal or species-specific differences in the role of this enzyme in petal senescence.

One aim of this study was to identify genes that might indicate differences in the regulation of petal and leaf senescence. Only one wallflower sequence related to transcriptional regulation was identified in the class of probes from the wallflower microarray that were up-regulated in petals but not in leaves; this was WLS63, a CCR4-related gene. In yeast, the CCR4 protein forms part of the CCR4-NOT complex, which acts as an RNA deadenylase, and is involved in nutrient and stress sensing (Collart, 2003). The role of these genes in plants has not been fully investigated. RT-PCR showed that expression patterns of WLS63 in wallflower are very different between leaves and petals. WLS63 peaks in expression in petals relatively late, at stage 4, when petals are already showing visible signs of senescence, after the peak in SAG12 expression. This suggests that it may be important in mRNA stability late in senescence, perhaps targeting specific transcripts for degradation. In leaves, WLS63 transcripts are at their highest levels in young leaves and fall thereafter to lower levels of expression. This could imply either that it is not involved in leaf senescence in this species or, alternatively, that its down-regulation stabilizes specific transcripts.

Shared and Petal-Specific Gene Expression

The high prevalence of SAG12 clones (14% overall; 8% of petal clones and 21% of leaf clones) is expected due to the close taxonomic relationship to Arabidopsis and Brassica, in which SAG12 is a highly abundant transcript in senescent leaves (Lohman et al., 1994; Guo et al., 2004). Although metallothioneins were represented in both libraries (6% in petal and 7% in leaf), the levels were not as high as those found in other EST studies of petal senescence, in which they were present at levels of 19% in Alstroemeria (Breeze et al., 2004) and 11% in Rosa (Channeliere et al., 2002), indicating species-specific differences in the expression of these genes and perhaps in their role in petal senescence. Metallothioneins have been found in other studies of leaf ESTs, although not at such high levels as in wallflower (e.g. rice [Oryza sativa] mature leaves, 3% [Gibbings et al., 2003]; senescent Arabidopsis leaves, 3% [Guo et al., 2004]).

Two genes were found at unexpectedly high frequency in the array class up-regulated in senescent petals but not leaves: chitinases and GSTs. The very high abundance of chitinase genes in the wallflower petal libraries (23%) was a surprise, and there was a clear interorgan difference, with only 2% of the genes found in the leaf library identified as chitinase. Although chitinase transcripts have been reported as senescence enhanced in other species in leaves in Brassica (Guerrero et al., 1990; Hanfrey et al., 1996) and petals in Alstroemeria (Breeze et al., 2004), EST studies of senescent petals or leaves have not revealed the high abundance found here. The major role of chitinases was usually thought to be in pathogen defense, and they are classed as pathogenesis-related proteins. However, it is becoming clear that chitinases may also have roles in signaling and programmed cell death (Kasprzewska, 2003).

GSTs are up-regulated in petal senescence in other species, such as carnation (Meyer et al., 1991). Although the role of most plant GSTs is unclear (Wagner et al., 2002), some, including those of the Arabidopsis φ class, may act as glutathione peroxidises, protecting cells from ROS damage, while others may have roles in hormone metabolism. Two wallflower targets were most closely homologous to AtGSTZ1, which is involved in Tyr metabolism (Dixon et al., 2000). The other wallflower clones were closest in amino acid sequence to φ class GSTs from Arabidopsis: AtGSTF2 and AtGSTF3. AtGSTF2 is membrane associated (Zettl et al., 1994) and ethylene responsive; both AtGSTF2 and AtGSTF3 have a putative ethylene-responsive enhancer element in their promoter sequences similar to that found in the petal senescence-enhanced carnation GST (Itzhaki et al., 1994) and are also up-regulated by salicylic acid (Wagner et al., 2002). AtGSTZ1 transcription is not induced by ethylene but is induced by methyl jasmonate, and both AtGSTF2 and AtGSTZ1 are induced by the auxin analog 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (Wagner et al., 2002). Thus, GSTs are clearly involved in processes related to senescence, and their up-regulation in wallflower petals but not in leaves may reflect important differences in the regulation of senescence by plant growth regulators or in the fine control of senescence progression in these two tissues. Clearly, the role of GSTs in wallflower petal senescence is also worthy of further investigation.

Cross-Species and Cross-Tissue Comparisons of Expression Patterns

Overall, 57% of the Arabidopsis genes on the array gave consistent results when hybridized to the wallflower transcripts. This compares favorably with other studies using species taxonomically related to Arabidopsis (e.g. in Thlaspi arvense arrays, only 31% of probes cross-hybridized to Arabidopsis [Sharma et al., 2007]). Likewise, for the six wallflower genes on the array, for which the closest Arabidopsis homolog was also included on the array and data were available from the Affymetrix experiments, there was a very high level of agreement. Thus, although caution must be exercised in the interpretation of data from cross-species experiments, due to the complications of gene families and inherent difficulties in precisely assigning stages of development, these data strongly support the use of this approach here.

Due to the close taxonomic relationship between the two species, floral architecture in wallflower and Arabidopsis is similar, and in both species leaves form sequentially in a spiral. However, wallflower petals differ from Arabidopsis petals in their purple pigmentation and much slower development and senescence. Differences in leaf senescence strategy might also occur due to the diverse life cycles in the two species: perennial in wallflower and ephemeral Arabidopsis. Genes that share expression patterns between the two species thus reflect perhaps the underlying evolutionary conservation, while those with differing patterns may reflect species-specific strategies. Over one-third (38%) of the Arabidopsis genes on the array and 53% of the wallflower genes shared gene expression patterns in the two species, indicating a conservation of a significant portion of the gene expression profile. However, a number of genes differed in expression pattern between the two species. These include both the AtGSTZ1 gene and the Arabidopsis chitinase gene (At2g43570), which were up-regulated with senescence in Arabidopsis leaves while the wallflower homologues were not. These differences may reflect a divergence of senescence strategies in the two species and, again, would be interesting for future studies.

CONCLUSION

This study has revealed considerable differences in gene expression during senescence both between petals and leaves and between two closely related species. Further work to understand petal and leaf senescence in these species will exploit the advantages of wallflower for biochemical studies and the myriad resources for forward and reverse genetics available for Arabidopsis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material

Leaves and petals were collected from wallflower (Erysimum linifolium ‘Bowles Mauve’) and staged (Figs. 1 and 2). Material for RNA extraction was immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until required.

Cut Flower Treatments

Individual flowers were detached from the raceme at stage 1, and the pedicel was immediately submerged in water. Flowers were held at 20°C and 16 h of light either in water or in solutions of kinetin (1.0 or 0.1 mm) or 6-methyl purine (0.1 mm; Sigma-Aldrich). For ethylene inhibitor treatment, flowers were held in STS (4 mm AgNO3:32 mm NaS2O3) for 1 h and then transferred to water. Each experiment consisted of 10 replicate flowers, which were monitored daily to record senescence stage and day of petal abscission.

Chlorophyll Extraction

Chlorophyll was extracted from leaves using 70% acetone, and absorbance was measured at 645, 652, and 663 nm using a Cecil Instruments Visible/UV spectrophotometer. Chlorophyll concentrations (in micrograms of chlorophyll per milliliter of extract) were calculated according to Bruinsma (1963) and normalized to fresh weight.

Protein Content

Proteins were extracted by grinding 16 petals or one leaf from each developmental stage in 200 μL of 100 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 20% glycerol, and 30 mm dithiothreitol at 4°C. Following centrifugation for 30 min at 12,000g and 4°C, supernatants were stored at −80°C until required. Protein content was quantified using the method described by Bradford (1976) using Bradford reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) and bovine serum albumin as a standard, quantified spectrophotometrically at 590 nm in a Molecular Devices Emax precision microplate reader, using the Molecular Devices SOFTmax Pro software (version 3; Molecular Devices). Each sample and standard was in triplicate on each plate, and each assay was repeated on five different extracts made from independently harvested material.

RNA Extraction

Extractions from 0.2 g of both leaves and petals were performed using 2 mL of TRI reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer's protocol, following grinding to a powder in liquid nitrogen using a mortar and pestle. For larger scale extractions, 10 mL of TRI reagent was added to 1 g of ground tissue and homogenized using an IKA Labortechnik T25 basic polytron motorized homogenizer. Extractions followed the manufacturer's protocol for TRI reagent except that the chloroform phase was back-extracted with 1 mL of sterile, distilled water and RNA was isopropanol precipitated before extraction with isoamyl alcohol:phenol:chloroform (1:25:24) until the interface was clear. Finally, the extracts were chloroform extracted, ethanol precipitated, ethanol washed, and resuspended in sterile distilled water. RNA was treated with RQ1 DNase (Promega) and, for use in making probes, was further purified using an RNeasy purification column (Qiagen).

Subtracted Library Construction

Two subtracted libraries were made to enrich for genes that are up-regulated during senescence: one from petals and one from leaves. Equal amounts of RNA were combined to make cDNA from young petals (stages −2, −1, and 0), which was subtracted from that from old petals (stages 3, 4, and 5). The leaf library was constructed from young leaves (stage 3) subtracted from old leaves (combined stages 5 and 6). First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using the Smart cDNA synthesis kit (Clontech). PCR cycle number was optimized for second-strand synthesis to ensure that amplification was in the exponential phase. Old leaf template required 19 cycles, while 17 cycles were used for the other templates. Ligation efficiency was tested using degenerate primers designed to the SAG12 gene from Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) and Brassica napus: SAG12F, 5′-TTGCCGGTTTCTGTTGAYTGG-3′; SAG12R, 5′-TGGTGTGCCACTGCYTTCAT-3′, where Y = C/T. Subtraction of the Smart double-stranded cDNA was performed using PCR-Select cDNA subtraction (Clontech) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The final amplification step was carried out over 12 cycles. The SAG12 primers were also used to test the efficiency of the subtraction. PCR products were cleaned using the Qiaquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen), concentrated by ethanol precipitation, and cloned into pGEM-T easy (Promega). Individual colonies were grown as liquid cultures on 96-well plates and stored as glycerol stocks at −80°C.

For sequencing, inserts were PCR amplified using M13 forward and reverse primers from the glycerol stocks or isolated using a Qiaprep Miniprep kit (Qiagen). PCR products were purified using Millipore MANU 03050 plates or Qiaquick PCR cleanup kits (Qiagen). All sequencing was performed using M13 forward and reverse primers with BigDye version 2 (Applied Biosystems) and analyzed on an Applied Biosystems 3100 sequencer. Database searches were carried out using the BLAST network service (National Center for Biotechnology Information), The Arabidopsis Information Resource, and AtGenExpress. A match was assessed using a combination of low E value and the length of the homology in tBLASTx. Alignments of proteins and sequences were performed using BIOEDIT version 7.0.1 (Hall, 1999) and Seqman (DNAstar; Lasergene). Contig assembly was performed using DNAstar (Lasergene), setting a threshold match of 80%.

Microarrays

PCR products were cleaned using the Whatman 96-well PCR cleanup kit and checked by gel electrophoresis. Fifty to 100 ng of each PCR product in 2.5 μL was added to 2.5 μL of dimethyl sulfoxide on 384-well plates using a Perkin-Elmer multiprobe liquid-handling robot, then spotted as a 4 × 12 metagrid of 12 × 12 subgrids onto UltraGAPS II (Gamma Amino Propyl Silane; Corning)-coated slides using 150-μm solid pins on a Genomic Solutions Flexys workstation. Each slide carried three replicates of each target DNA. Slides were air dried for 12 h, baked at 80°C for 2 h, and UV cross-linked with an Autocrosslink cross linker (Stratagene). They were stored with desiccant in the dark at room temperature until required.

Labeling of RNA for Hybridization to the Arrays

mRNA was amplified using the MessageAmp aRNA kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer's protocol from 5 μg of extracted total RNA from the same combined tissue stages used to generate the SSH libraries (petals stages −2, −1, and 0 representing young petals; stages 3, 4, and 5 representing old petals; leaf stage 3 representing young leaves; and leaf stages 5 and 6 representing old leaves). Material was derived from six clonal plants, and RNA used for labeling was combined from different batches of petals and leaves collected on different dates to ensure the randomization of any possible bias in the material or in the RNA extraction. Different RNA extracts were used in the construction of the SSH libraries and for labeling the RNA to be hybridized to the arrays. The CyScribe Post-Labeling kit (Amersham Biosciences) was used to label the aRNA, with either Cy3 or Cy5 according to the manufacturers' instructions, using 1 μg of aRNA.

Each labeled RNA pair was lyophilized using an Edwards Freeze Dryer Modulyo Pirani 501 and resuspended in 50 μL of hybridization buffer containing 25% formamide, 5× SSC, 0.1% SDS, 0.5 mg mL−1 poly(dA), and 0.5 mg mL−1 yeast tRNA.

Slides were prehybridized for 45 min in a 5× SSC, 0.1% SDS, 1% bovine serum albumin solution preheated to 42°C, washed five times in milliQ water and twice in isopropanol, and air dried. For hybridization, the labeled RNA was heated to 95°C for 5 min and applied to the microarray slide surface. A second microarray slide was lowered over the labeled RNA and the slides were hybridized back to back overnight in a humid chamber at 42°C. Hybridizations were carried out four times with dye swapping. Following hybridization, the slides were separated by immersion in 2× SSC, 0.1% SDS at 42°C and washed in the same solution for 5 min. The slides were further washed in a solution of 0.1× SSC, 0.1% SDS for 10 min at room temperature, followed by four changes of 0.1× SSC for 1 min each at room temperature. The slides were rinsed in isopropanol and dried by centrifugation for 1 min at 2,000g in a MSE Mistral 2000 centrifuge.

Analysis of Microarray Slides

The slides were scanned using an Affymetrix 428 array scanner with the supplied software (Affymetrix) at 532 nm (Cy3) and 633 nm (Cy5). Scanned images were quantified using Imagene version 5 software (Biodiscovery). Spot quality labeling (flags) was defined for empty spots with a signal strength threshold of 1 and for shape regularity with a threshold of 0.4. The median signal intensity across each spot and the median background intensity were calculated in both channels, and these data were exported into GeneSpring version 6 (Agilent). Background intensity was subtracted from spot intensity for both channels, giving the background-corrected spot intensity. Each slide carried three replicates of each gene, and four slides were used in the experiment, including a dye swap for each probe pair. The scores for the 12 data points per spot were averaged in GeneSpring, and threshold ratios of 2 and 0.5 were set. Genes with a P value of >0.05 and not passing the Benjamini and Hochberg false discovery rate were excluded. A list was generated containing all genes whose expression changed in at least one tissue and whose expression could be reliably determined in both tissues.

Northern Hybridization

Northern blotting and hybridization were performed using RNA extracted from Arabidopsis leaves as described by Buchanan-Wollaston and Ainsworth (1997). For making probes, inserts from Arabidopsis cDNA clones were PCR amplified and labeled with [32P]dCTP using the RediPrime random priming labeling kit (Amersham Biosciences). Ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase small chain was included as a probe to verify the loading.

Semiquantitative RT-PCR

Specific PCR primers were designed to the EST sequences obtained from the wallflower SSH libraries to SAG12 as detailed above, clone WLS63 (LP H9 F, 5′-GTTTGGACCGGGTTGCTC-3′; LP H9 R, 5′-ACTCCGGCGTGTTTCACC-3′), which amplify a 130-bp fragment of the gene, and clone WC11A (P1 F4 F, 5′-AGAGCTTCGGAAGCGCTCTG-3′; P1 F4 R, 5′-AGGTACCACTTTGCACATGC-3′), which amplify a 219-bp gene fragment. Normalization controls were performed using primers PUV2 (5′-TTCCATGCTAATGTATTCAGAG-3′) and PUV4 (5′-ATGGTGGTGACGGGTGAC-3′; Dempster et al., 1999), which amplify a 488-bp fragment of 18S rRNA. Reactions were cycled in a Perkin-Elmer 2700 thermocycler or an MJ Research PTC100, using 15 min at 95°C for Hotstar Taq polymerase (Qiagen), 1 min at 95°C for standard Taq polymerase, followed by cycles of 95°C for 10 s, 65°C for 30 s, and 68°C for 2.5 min for the SAG12, WLS63, and WC11 primers on the Perkin-Elmer 2700 and 95°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min on the PTC100. Replicates for each primer set were all amplified on the same machine to avoid any variability due to the machine parameters. Annealing temperature for the PUV and GST primers was 50°C on both machines. Products were analyzed by agarose gels, and PCR products were quantified using the Gene Genius bioimaging system and GeneSnap software (Syngene, Synoptics). Product quantitation from the 18S target was used to normalize results for all other primer sets. To ensure that the reactions were in the exponential phase and therefore product quantitation could be considered semiquantitative in relation to message abundance, cycles were optimized and limited for each primer set and cDNA synthesis batch combination. Specific cycle number is not reported here, as it was optimized independently for each batch of cDNA. Dilution series of the cDNA were included in every PCR run, and results were only accepted when a linear response was obtained. This methodology has been used successfully to obtain semiquantitative RT-PCR data for a range of experimental systems (Wagstaff et al., 2002, 2003, 2005; Parfitt et al., 2004; Orchard et al., 2005).

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under the accession numbers provided in the text and in Supplemental Table S1.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Effects on abscission time of cut wallflowers treated with cytokinin (A; 1.0 or 0.1 mm kinetin), 6-methyl purine (B; 0.1 mm), and STS (C), compared with water control (n = 10 flowers per treatment).

Supplemental Figure S2. Effects on progression of petal development and senescence in cut wallflowers treated with water (A), 1.0 mm kinetin (B), 0.1 mm kinetin (C), 0.1 mm 6-methyl purine (D), and STS (E; n = 10 flowers per treatment).

Supplemental Table S1. List of wallflower and Arabidopsis microarray probes for which reliable data from both wallflower petal and leaf hybridizations could be obtained.

Supplemental Table S2. Comparison between expression of genes represented by probes on the wallflower array, hybridized to senescent and young wallflower petal and leaf transcripts, and the expression of the nearest Arabidopsis homolog in Arabidopsis senescent and young petal and leaf from Affymetrix data.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Gareth Lewis, Steven Hope (School of Biosciences Cardiff), and Rachel Edwards and Jeanette Selby (Warwick) for sequencing and to Lyndon Tuck (Cardiff) for plant maintenance.

This work was supported by grants from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (to A.M.P.), the Chilean Government, Ministry of Agriculture (to D.F.A.O.), and the Malaysian Government (to F.M.S.).

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantphysiol.org) is: Hilary J. Rogers (rogershj@cf.ac.uk).

The online version of this article contains Web-only data.

References

- Bieleski RL (1995) Onset of phloem export from senescent petals of daylily. Plant Physiol 109 557–565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borochov A, Woodson W (1989) Physiology and biochemistry of flower petal senescence. Hortic Rev (Am Soc Hortic Sci) 11 15–43 [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72 248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breeze E, Wagstaff C, Harrison E, Bramke I, Rogers H, Stead A, Thomas B, Buchanan-Wollaston V (2004) Gene expression patterns to define stages of post-harvest senescence in Alstroemeria petals. Plant Biotechnol J 2 155–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruinsma J (1963) The quantitative analysis of chlorophyll a and b in plant extracts. Photochem Photobiol 2 241–249 [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan-Wollaston V (1997) The molecular biology of leaf senescence. J Exp Bot 48 181–199 [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan-Wollaston V, Ainsworth C (1997) Leaf senescence in Brassica napus: cloning of senescence related genes by subtractive hybridisation. Plant Mol Biol 33 821–834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan-Wollaston V, Page T, Harrison E, Breeze E, Lim PO, Nam HG, Lin JF, Wu SH, Swidzinski J, Ishizaki K, et al (2005) Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals significant differences in gene expression and signalling pathways between developmental and dark/starvation-induced senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant J 42 567–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang HS, Jones ML, Banowetz GM, Clark DG (2003) Overproduction of cytokinins in petunia flowers transformed with P-SAG12-IPT delays corolla senescence and decreases sensitivity to ethylene. Plant Physiol 132 2174–2183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Channeliere S, Riviere S, Scalliet G, Szecsi J, Jullien F, Dolle C, Vergne P, Dumas C, Bendahmane M, Hugueney P, et al (2002) Analysis of gene expression in rose petals using expressed sequence tags. FEBS Lett 515 35–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Chiang YC, Denis CL (2002) CCR4, a 3′–5′ poly(A) RNA and ssDNA exonuclease, is the catalytic component of the cytoplasmic deadenylase. EMBO J 21 1414–1426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang CS, Stacey G, Tsay YF (2004) Mechanisms and functional properties of two peptide transporters, AtPTR2 and fPTR2. J Biol Chem 279 30150–30157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collart MA (2003) Global control of gene expression in yeast by the Ccr4-Not complex. Gene 313 1–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier DE (1997) Changes in respiration, protein and carbohydrates of tulip tepals and Alstroemeria petals during development. J Plant Physiol 150 446–451 [Google Scholar]

- Dempster E, Pryor K, Francis D, Young J, Rogers H (1999) Rapid DNA extraction from ferns for PCR based analyses. Biotechniques 27 66–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon DP, Cole DJ, Edwards R (2000) Characterisation of a zeta class glutathione transferase from Arabidopsis thaliana with a putative role in tyrosine catabolism. Arch Biochem Biophys 384 407–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eason JR, Webster D (1995) Development and senescence of Sandersonia aurantiaca (Hook.) flowers. Scientia Hort 63 113–121 [Google Scholar]

- Erdelská O, Ovečka M (2004) Senescence of unfertilised flowers in Epiphyllum hybrids. Biol Plant 48 381–388 [Google Scholar]

- Friedman WE, Moore RC, Purugganan MD (2004) The evolution of plant development. Am J Bot 91 1726–1741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan SS, Amasino RM (1995) Inhibition of leaf senescence by autoregulated production of cytokinin. Science 270 1986–1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan SS, Amasino RM (1997) Making sense of senescence: molecular genetic regulation and manipulation of leaf senescence. Plant Physiol 113 313–319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gepstein S, Sabehi G, Carp MJ, Hajouj T, Nesher MFO, Yariv I, Dor C, Bassani M (2003) Large-scale identification of leaf senescence associated genes. Plant J 36 629–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbings J, Cook B, Dufault M, Madden S, Khuri S, Turnbull C, Dunwell J (2003) Global transcript analysis of rice leaf and seed using SAGE technology. Plant Biotechnol J 1 271–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grbić V, Bleecker AB (1995) Ethylene regulates the timing of leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant J 8 595–602 [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero FD, Jones JT, Mullet JE (1990) Turgor-responsive gene transcription and RNA levels increase rapidly when pea shoots are wilted: sequence and expression of three inducible genes. Plant Mol Biol 15 11–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Cai Z, Gan S (2004) Transcriptome of Arabidopsis leaf senescence. Plant Cell Environ 27 521–549 [Google Scholar]

- Hall TA (1999) BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser 41 95–98 [Google Scholar]

- Hanfrey C, Fife M, Buchanan-Wollaston V (1996) Leaf senescence in Brassica napus: expression of genes encoding pathogenesis-related proteins. Plant Mol Biol 30 597–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayati R, Egli DB, Crafts-Brandner SJ (1995) Carbon and nitrogen supply during seed filling and leaf senescence in soybean. Crop Sci 35 1063–1069 [Google Scholar]

- Hensel LL, Grbic V, Baumgarten DA, Bleecker AB (1993) Developmental and age-related processes that influence the longevity and senescence of photosynthetic tissues in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 5 553–564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himelblau E, Amasino RM (2000) Delivering copper within plant cells. Curr Opin Plant Biol 3 205–210 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinderhofer K, Zentgraf U (2001) Identification of a transcription factor specifically expressed at the onset of leaf senescence. Planta 213 469–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itzhaki H, Maxson JM, Woodson WR (1994) An ethylene-responsive enhancer element is involved in the senescence-related expression of the carnation glutathione-S-transferase (GST1) gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91 8925–8929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasprzewska A (2003) Plant chitinases: regulation and function. Cell Mol Biol Lett 8 809–824 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lay Yee M, Stead AD, Reid MS (1992) Flower senescence in daylily (Hemerocallis). Physiol Plant 86 308–314 [Google Scholar]

- Lohman KN, Gan S, John MC, Amasino RM (1994) Molecular analysis of natural leaf senescence in Arabidopsis thaliana. Physiol Plant 92 322–328 [Google Scholar]

- Mae T, Hoshino T, Ohira K (1985) Protease activities and loss of nitrogen in the senescing leaves of field-grown rice (Oryza sativa L.). Soil Sci Plant Nutr 31 589–600 [Google Scholar]

- Merzlyak MN, Hendry GAF (1994) Free-radical metabolism, pigment degradation and lipid peroxidation in leaves during senescence. Proc R Soc Edinburgh B 102 459–471

- Meyer RC Jr, Goldsbrough PB, Woodson WR (1991) An ethylene-responsive flower senescence-related gene from carnation encodes a protein homologous to glutathione S-transferases. Plant Mol Biol 17 277–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols R, Ho LC (1975) Effect of ethylene on distribution of sucrose-C-14 from petals to other flower parts in senescent cut inflorescence of Dianthus caryophyllus. Ann Bot (Lond) 39 433–438 [Google Scholar]

- Orchard CB, Siciliano I, Sorrel DA, Marchbank A, Rogers HJ, Francis D, Herbert RJ, Suchomelova P, Lipavska H, Azmi A, et al (2005) Tobacco BY-2 cells expressing fission yeast cdc25 bypass a G2/M block on the cell cycle. Plant J 44 290–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otegui MS, Noh YS, Martýnez DE, Vila Petroff MG, Staehelin LA, Amasino RM, Guiamet JJ (2005) Senescence-associated vacuoles with intense proteolytic activity develop in leaves of Arabidopsis and soybean. Plant J 41 831–844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panavas T, Rubinstein B (1998) Oxidative events during programmed cell death of daylily (Hemerocallis hybrid) petals. Plant Sci 133 125–138 [Google Scholar]