Abstract

The essential splicing factor human UAP56 (hUAP56) is a DExD/H-box protein known to promote prespliceosome assembly. Here, using a series of hUAP56 mutants that are defective for ATP-binding, ATP hydrolysis, or dsRNA unwindase/helicase activity, we assess the relative contributions of these biochemical functions to pre-mRNA splicing. We show that prespliceosome assembly requires hUAP56’s ATP-binding and ATPase activities, which, unexpectedly, are required for hUAP56 to interact with U2AF65 and be recruited into splicing complexes. Surprisingly, we find that hUAP56 is also required for mature spliceosome assembly, which requires, in addition to the ATP-binding and ATPase activities, hUAP56’s dsRNA unwindase/helicase activity. We demonstrate that hUAP56 directly contacts U4 and U6 snRNAs and can promote unwinding of the U4/U6 duplex, and that both these activities are dependent on U2AF65. Our results indicate that hUAP56 first interacts with U2AF65 in an ATP-dependent manner, and subsequently with U4/U6 snRNAs to facilitate stepwise assembly of the spliceosome.

Keywords: hUAP56, splicing, prespliceosome assembly, spliceosome assembly, ATP binding, ATPase, RNA helicase

Pre-mRNA splicing occurs in a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex called the spliceosome, which comprises a large number of proteins and several U small nuclear RNP particles (snRNPs) termed U1, U2, U4, U5, and U6. Assembly of the spliceosome on the pre-mRNA substrate proceeds in a stepwise manner and involves the recognition of intron-defining splice signals (for review, see Hertel and Graveley 2005). Spliceosome assembly is initiated by the formation of complex E, in which U1 snRNP is stably associated with the 5′ splice site, SF1 is associated with the branchpoint, and U2 snRNP auxiliary factor (U2AF) subunits U2AF65 and U2AF35 are associated with the polypyrimidine (Py)-tract and 3′ splice site, respectively. Subsequently, SF1 is replaced by U2 snRNP at the branchpoint, leading to the formation of complex A (the prespliceosome). Mature spliceosome assembly occurs upon entry of the U4/U6 ⋅ U5 tri-snRNP to form complex B, followed by structural rearrangements to form the catalytically active complex C, in which U2 and U6 snRNAs interact, and U6 replaces U1 at the 5′ splice site.

Many steps in spliceosome assembly require ATP hydrolysis and are mediated by a series of splicing factors that are members of the DExD/H-box protein family, the founding member of which is eIF-4A, a known RNA helicase (for review, see Staley and Guthrie 1998; Silverman et al. 2003; Rocak and Linder 2004). Several of these DExD/H-box splicing factors have been shown to possess an ATP-dependent RNA unwinding/helicase activity (Laggerbauer et al. 1998; Raghunathan and Guthrie 1998; Wagner et al. 1998; Wang et al. 1998) and are thought to use ATP hydrolysis as a driving force to modulate specific RNA structural rearrangements during spliceosome assembly. DExD/H-box proteins typically have a series of conserved sequence motifs; structural, mutational, and biochemical analyses have suggested roles for these motifs in ATP-binding, ATP hydrolysis (ATPase), RNA-binding, and dsRNA unwinding/helicase activities (for review, see Rocak and Linder 2004; Cordin et al. 2006; Linder 2006).

We originally identified a human 56-kDa DExD/H-box protein, U2AF65-Associated Protein (hUAP56), in a two-hybrid screen for proteins that interact with U2AF65 (Fleckner et al. 1997). Subsequent studies in Drosophila, Xenopus, and yeast have shown that UAP56 is also involved in other aspects of RNA metabolism, including general mRNA export from the nucleus (Gatfield et al. 2001; Luo et al. 2001; Herold et al. 2003) and cytoplasmic mRNA localization (Meignin and Davis 2008).

hUAP56 is an essential splicing factor that is required for the U2 snRNP–branchpoint interaction during prespliceosome assembly. Recruitment of hUAP56 to the pre-mRNA is dependent on the Py-tract and U2AF65; the interaction with U2AF65 presumably directs hUAP56 to the vicinity of the branchpoint. The detailed mechanism by which hUAP56 facilitates splicing and complex assembly, however, is not known. Here we study the role of hUAP56 in spliceosome assembly through analysis of hUAP56 derivatives bearing mutations that selectively interfere with DExD/H-box biochemical functions. Our results reveal a new role for ATP hydrolysis in the function of a DExD/H-box protein.

Results

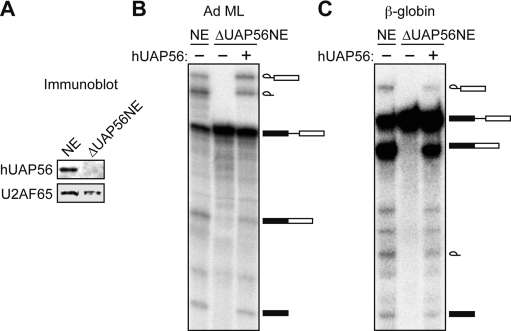

Requirement of the hUAP56 ATP-binding, ATPase, and dsRNA unwindase/helicase activities for in vitro pre-mRNA splicing

To analyze the role of hUAP56 in spliceosome assembly, we developed a biochemical complementation system. We raised a polyclonal α-hUAP56 antibody and used it to immunodeplete hUAP56 from HeLa nuclear extract (NE; ΔUAP56NE) (Fig. 1A). As expected, splicing of an Ad ML pre-mRNA substrate did not occur in the ΔUAP56NE (Fig. 1B, lane 2); however, addition of purified, recombinant wild-type hUAP56 to the ΔUAP56NE restored splicing to levels approaching that observed in HeLa NE (Fig. 1B, cf. lanes 3 and 1). Similarly, splicing of another, unrelated pre-mRNA substrate, human β-globin, did not occur in the ΔUAP56NE, but was restored following addition of hUAP56 (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Development of a biochemical complementation system to analyze the role of hUAP56 in spliceosome assembly. (A) Immunoblot analysis showing protein levels of hUAP56 and, as a specificity control, U2AF65, in mock-depleted HeLa NE and in hUAP56-depleted HeLa NE (ΔUAP56NE). (B) hUAP56 was analyzed for its ability to complement splicing of the Ad ML pre-mRNA substrate in the ΔUAP56NE. Splicing of Ad ML in mock-depleted HeLa NE is shown as a control. The signal corresponding to fully spliced pre-mRNA was quantitated; for NE, the value was arbitrarily set to 100%, and for ΔUAP56NE and ΔUAP56NE+hUAP56 measured 2% and 64%, respectively. (C) Splicing of the β-globin pre-mRNA substrate following addition of hUAP56 to the ΔUAP56NE. Quantitation of the fully spliced pre-mRNA signal was as follows: NE, 100%; ΔUAP56NE, 3%; ΔUAP56NE+hUAP56, 63%.

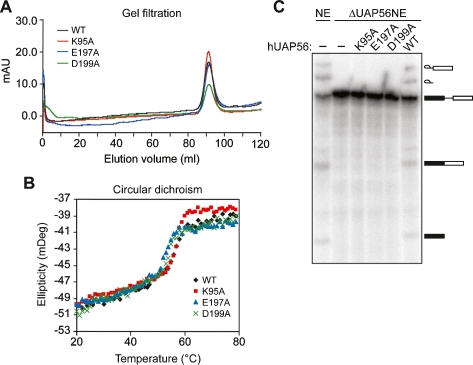

To study the role of hUAP56 in pre-mRNA splicing, we analyzed a previously characterized series of hUAP56 mutant derivatives (Shen et al. 2007). The hUAP56 mutants K95A and E197A are defective for ATPase activity and, consequently, also for dsRNA unwinding/helicase activity. Based on the structures of several DExD/H-box proteins, the K95 residue is proposed to be important for ATP-binding (Benz et al. 1999; Caruthers and McKay 2002; Shi et al. 2004; Sengoku et al. 2006), whereas E197 is thought to be a key catalytic residue involved in ATP hydrolysis (Caruthers and McKay 2002; Cordin et al. 2006; Sengoku et al. 2006). The hUAP56 mutant D199A retains ATPase activity but is defective for dsRNA unwinding/helicase activity (Shen et al. 2007). For convenience, we will refer to these derivatives as an ATP-binding mutant (K95A), ATPase mutant (E197A), and dsRNA unwinding/helicase mutant (D199A).

All three mutant proteins were expressed in and purified from Escherichia coli. The overall structures of the three mutant proteins were intact, as evidenced by gel filtration elution profiles (Fig. 2A) and thermal melting curves (Fig. 2B) that were similar to those of the wild-type hUAP56 protein. We assessed the ability of each mutant to support splicing of the Ad ML pre-mRNA substrate in the ΔUAP56NE. The results of Figure 2C show that following addition to the ΔUAP56NE, all three hUAP56 mutants failed to support splicing.

Figure 2.

Requirement of the hUAP56 ATP-binding, ATPase, and dsRNA unwindase/helicase domains for in vitro pre-mRNA splicing. (A) Gel filtration profiles of wild-type hUAP56 or the ATP-binding (K95A), ATPase (E197A), or dsRNA unwindase/helicase (D199A) mutants. (mAU) milliabsorption unit. (B) Thermal melting curves for wild-type hUAP56 and mutant derivatives, as monitored by circular dichroism spectroscopy. The melting temperatures (Tm) for wild-type, K95A, E197A, and D199A hUAP56 are 55°C, 56°C, 52°C, and 53°C, respectively. (C) Wild-type hUAP56 or mutant derivatives were analyzed for their ability to support splicing of the Ad ML pre-mRNA substrate in the ΔUAP56NE.

hUAP56 functions during both prespliceosome and spliceosome assembly

We next analyzed the ability of the three hUAP56 mutants to support splicing complex assembly. Figure 3A shows that the ΔUAP56NE failed to support formation of the prespliceosome (complex A) or the mature spliceosome (complex B/C). This result is consistent with our original finding that hUAP56 is required for formation of the prespliceosome (Fleckner et al. 1997), a precursor to the mature spliceosome. Figure 3A also shows that the three hUAP56 mutants differentially affected spliceosome assembly. The ATP-binding (K95A) and ATPase (E197A) mutants failed to support assembly of the prespliceosome and mature spliceosome. In contrast, the dsRNA unwinding/helicase mutant (D199A) supported assembly of the prespliceosome but not the mature spliceosome. As expected, formation of complex A in the presence of the dsRNA unwinding/helicase mutant required ATP and did not occur following RNAse H-directed cleavage of U2 snRNA (Fig. 3B). hUAP56 was not required for early complex (complex E) assembly (Fig. 3C), consistent with the fact that formation of complex E is an ATP-independent step (for review, see Hertel and Graveley 2005). Collectively, these results demonstrate that hUAP56 acts during assembly of both the prespliceosome and the mature spliceosome.

Figure 3.

hUAP56 functions during both prespliceosome and spliceosome assembly. (A) Wild-type hUAP56 and mutant derivatives were analyzed for their ability to support assembly of the prespliceosome (complex A) and mature spliceosome (complexes B and C) in the ΔUAP56NE. Also shown is assembly of the nonspecific complex H. (B) The D199A mutant was analyzed for its ability rescue complex A formation in the presence and absence of U2 snRNA and ATP. (C) Mutant hUAP56 derivatives were analyzed for their ability to support complex E assembly. U2AF-depleted and mock-depleted nuclear extracts were analyzed as negative and positive controls, respectively.

Role of hUAP56 in prespliceosome assembly

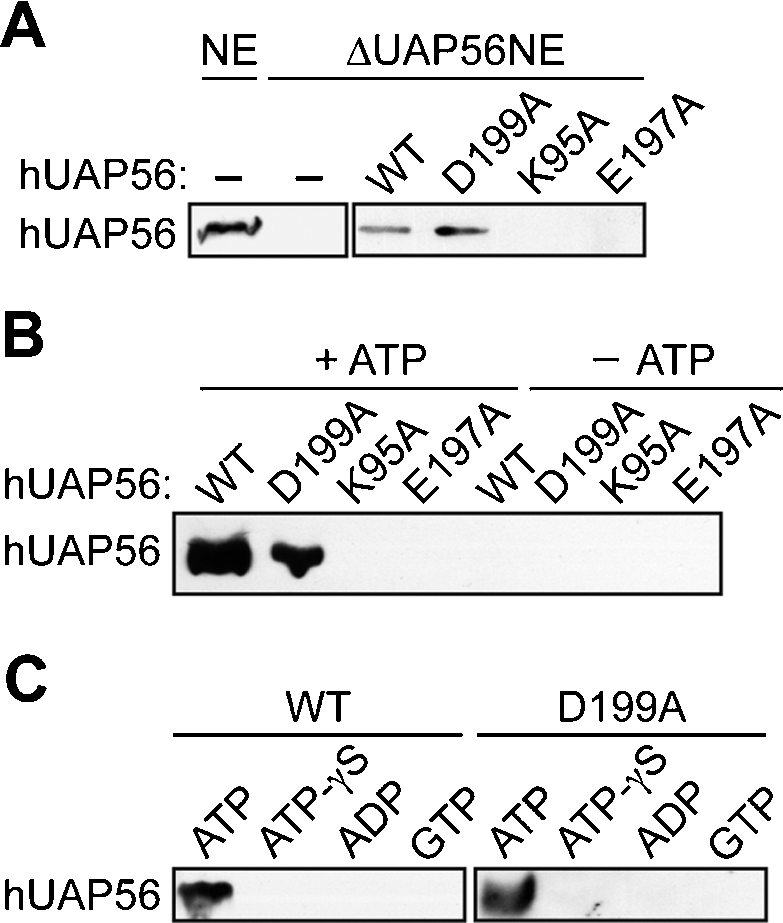

We previously found that hUAP56 is recruited to the pre-mRNA through an interaction with Py-tract-bound U2AF65 (Fleckner et al. 1997). Thus, a possible explanation for the failure of the hUAP56 mutants to support spliceosome assembly was an inability to interact with U2AF65 and thus be recruited into splicing complexes. As a first test of this hypothesis, wild-type hUAP56 or one of the three hUAP56 mutants were added to the ΔUAP56NE in the presence of a biotinylated pre-mRNA substrate, and splicing complexes were then affinity-purified and analyzed by immunoblotting for hUAP56. The results of Figure 4A show that only wild-type hUAP56 and the hUAP56 dsRNA unwinding/helicase mutant were recruited into splicing complexes. Thus, the inability of the ATP-binding and ATPase mutants to support prespliceosome assembly results from a failure to enter into splicing complexes.

Figure 4.

Role of hUAP56 in prespliceosome assembly. (A) hUAP56 recruitment experiments. Wild-type hUAP56 or mutant derivatives were added to the ΔUAP56NE, followed by addition of a biotinylated Ad ML pre-mRNA substrate. Splicing complexes were affinity-purified and analyzed by immunoblotting for hUAP56. (B) GST pull-down experiments. hUAP56 or mutant derivatives were incubated with GST-U2AF65 and, following GST pull-down, bound hUAP56 was detected by immunoblotting. Protein–protein interaction experiments were performed in the presence or absence of ATP, as indicated. (C) GST pull-down experiments were performed as described in B, except that ATP was replaced by either the non-hydrolyzable ATP analog ATP-γS, ADP, or GTP.

We next asked whether the failure of the hUAP56 ATP-binding and ATPase mutants to enter into splicing complexes was due to an inability to interact with U2AF65. Wild-type hUAP56 or an hUAP56 mutant was incubated under splicing conditions with purified GST-U2AF65, and, following purification on glutathione agarose, bound hUAP56 was detected by immunoblotting. The results of Figure 4B show, as predicted from our previous study (Fleckner et al. 1997), that U2AF65 and hUAP56 directly interact. Significantly, neither the ATP-binding nor ATPase mutant interacted with U2AF65, explaining their failure to enter into splicing complexes.

The inability of the hUAP56 ATP-binding and ATPase mutants to interact with U2AF65 suggested that the U2AF65–hUAP56 interaction was ATP-dependent. In support of this prediction, the results of Figure 4B show that hUAP56 failed to interact with GST-U2AF65 in the absence of ATP. Furthermore, Figure 4C shows that the U2AF65–hUAP56 interaction did not occur when ATP was replaced by either the non-hydrolyzable ATP analog adenosine-5′-O-(3-thio)triphosphate (ATP-γS), ADP, or GTP, confirming a requirement for ATP hydrolysis. Collectively, these results indicate that ATP-binding and hydrolysis are required for the U2AF65–hUAP56 interaction and the subsequent recruitment of hUAP56 into splicing complexes.

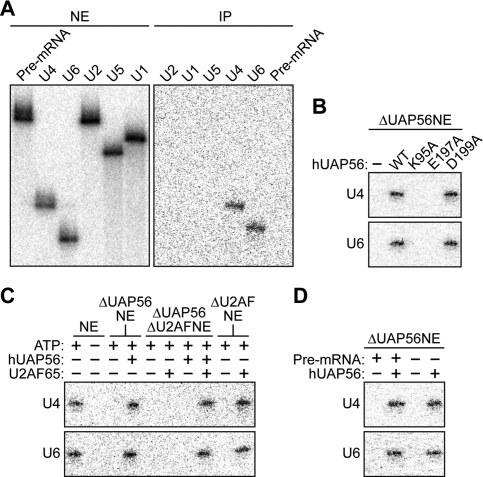

hUAP56 contacts U4 and U6 snRNAs

We next analyzed the role of hUAP56 in mature spliceosome assembly. We considered the possibility that hUAP56 promoted mature spliceosome assembly by directly contacting and recruiting a mature spliceosomal component, such as U4/U6 or U5 snRNP. To test this idea, we analyzed the potential association of various U snRNAs with hUAP56 using a UV cross-linking/immunoprecipitation assay. Following UV irradiation of HeLa NE to induce RNA–protein cross-links, hUAP56 was immunoprecipitated, and snRNAs in the immunoprecipitate were purified and detected by primer-extension analysis. The results of Figure 5A show that hUAP56 specifically contacted U4 and U6 snRNAs. We tested the ability of the three hUAP56 mutants to interact with U4 and U6 snRNAs. The results of Figure 5B show that only the dsRNA unwinding/helicase mutant (D199A) retained the ability to contact U4 and U6 snRNAs.

Figure 5.

hUAP56 contacts U4 and U6 snRNAs. U snRNA cross-linking/immunoprecipitation experiments. (A, left) Primer-extension analysis in untreated HeLa NE shows the positions of U snRNAs. (Right) Following UV irradiation, hUAP56 was immunoprecipitated, and snRNAs in the immunoprecipitate were purified and detected by primer-extension analysis. (B) Wild-type hUAP56 or mutant derivatives were added to the ΔUAP56NE, and association with U4 and U6 snRNAs was analyzed by UV cross-linking/immunoprecipitation. (C) Recombinant hUAP56, U2AF65, or both hUAP56 and U2AF65 were added to HeLa NEs that had been depleted of either hUAP56, U2AF, or both hUAP56 and U2AF, and association of hUAP56 with U4 and U6 snRNAs was analyzed by UV cross-linking/immunoprecipitation. (D) The ability of hUAP56 to bind U4 and U6 shRNAs was tested in the presence and absence of an unlabeled Ad ML pre-mRNA.

The identical behaviors of each of the three hUAP56 mutants in the hUAP56–U2AF65 (Fig. 4B) and hUAP56–U4/U6 snRNA (Fig. 5B) interaction assays raised the possibility that U2AF65 was required for hUAP56 to contact U4/U6 snRNAs. Consistent with this idea, Figure 5C shows that the interaction of hUAP56 with U4 and U6 snRNAs was ATP-dependent. To directly test the role of U2AF65, recombinant hUAP56, U2AF65, or both hUAP56 and U2AF65 were added to HeLa NEs that had been depleted of either hUAP56, U2AF, or both hUAP56 and U2AF, and association of hUAP56 with U4 and U6 snRNAs was analyzed by the UV cross-linking/immunoprecipitation assay. The results of Figure 5C demonstrate that the interaction of hUAP56 with U4 and U6 snRNAs required both hUAP56 and U2AF65. Notably, the hUAP56–U4/U6 snRNA interaction occurred in the absence of added pre-mRNA substrate (Fig. 5D), indicating that the requirement for U2AF65 was independent of its ability to recruit hUAP56 into spliceosomal complexes.

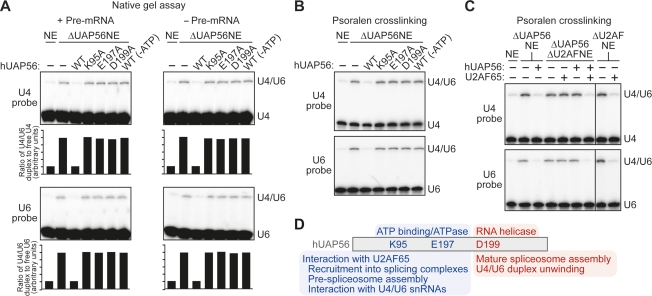

hUAP56 can unwind the U4/U6 duplex

Like other DExD/H-box proteins, hUAP56 can unwind a short, artificial RNA duplex in an ATP-dependent manner (Shen et al. 2007). The finding that hUAP56 contacted U4 and U6 snRNAs raised the possibility that hUAP56 could mediate unwinding of the natural U4/U6 duplex in U4/U6 snRNP. As an initial test of this idea, we used a previously described native gel assay that measures the ratio of free and duplex forms of U4 and U6 snRNAs (Laggerbauer et al. 1998). In brief, total RNA was purified and fractionated on a native gel to separate free U4 and U6 snRNAs from the U4/U6 duplex. The results of Figure 6A show that following incubation of a standard HeLa NE under splicing conditions, very little U4/U6 duplex was detectable. When the experiment was repeated in the ΔUAP56NE, a substantially higher level of U4/U6 duplex was observed. Addition of wild-type hUAP56 to the ΔUAP56NE markedly decreased the amount of U4/U6 duplex, and this effect was ATP-dependent. Significantly, none of the three hUAP56 mutants was able to support the ATP-dependent decrease in the level of U4/U6 duplex. Identical results were obtained in the presence or absence of an unlabeled Ad ML pre-mRNA substrate (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6.

hUAP56 can unwind the U4/U6 duplex. (A) Native gel assay. Total RNA was purified from extracts, incubated in the presence or absence of Ad ML pre-mRNA, and fractionated on a native gel to separate free U4 and U6 snRNAs from the U4/U6 duplex. Gels were probed with either a U4 (top) or U6 (bottom) probe. The ratio of U4/U6 duplex to free U4 or U6 was quantitated and is shown. (B) Psoralen cross-linking analysis. Assays were performed in the ΔUAP56NE following addition of wild-type hUAP56 or mutant derivates. (C) hUAP56 was depleted from U2AF-depleted extracts, and psoralen cross-linking experiments were performed following addition of hUAP56, U2AF65, or a combination of hUAP56 and U2AF65. (D) Schematic diagram of the hUAP56 protein, showing the residues required for ATP-binding, ATPase, and dsRNA unwindase/helicase activities and their role in prespliceosome and mature spliceosome assembly.

To verify that hUAP56 promoted unwinding of the U4/U6 duplex, we also performed a series of psoralen cross-linking experiments (Wassarman and Steitz 1992; Eperon et al. 2000; Zhu et al. 2003). In brief, HeLa NEs containing psoralen were irradiated with UV light to induce RNA–RNA cross-links, and the RNA products were purified and fractionated on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel. The identities of the U4/U6 snRNA cross-links were confirmed by Northern blot analysis. Consistent with the results of the native gel assay, the psoralen cross-linking results of Figure 6B show that a substantially higher level of U4/U6 duplex was observed in the ΔUAP56NE compared to HeLa NE. Moreover, addition of wild-type hUAP56, but not any of the three hUAP56 mutants, to the ΔUAP56NE markedly decreased the level of U4/U6 duplex. Collectively, the results of Figures 5 and 6 show that hUAP56 contacts U4 and U6 snRNAs, and promotes unwinding of the U4/U6 duplex, which requires all three hUAP56 biochemical functions.

Finally, we asked whether U2AF65 affected the ability of hUAP56 to unwind the U4/U6 duplex. Recombinant hUAP56, U2AF65, or both hUAP56 and U2AF65 were added to HeLa NEs that had been depleted of either hUAP56, U2AF, or both hUAP56 and U2AF, and unwinding of the U4/U6 duplex was analyzed by the psoralen cross-linking assay. Consistent with the results of the hUAP56–U4/U6 snRNA interaction assay (Fig. 5C), Figure 6C shows that unwinding of the U4/U6 duplex by hUAP56 requires U2AF65.

Discussion

In this study, we show that hUAP56 has multiple and surprisingly diverse roles in splicing complex assembly. Our major conclusions are summarized in Figure 6D and discussed below. We had previously found that hUAP56 was required for prespliceosome assembly (Fleckner et al. 1997). Here we confirm this result and find, unexpectedly, that hUAP56 is also required for the conversion of the prespliceosome to the mature spliceosome. Prespliceosome assembly is dependent on the hUAP56 ATP-binding and ATPase activities, which are required for interaction with U2AF65 and recruitment into splicing complexes. Mature spliceosome assembly requires, in addition to the ATP-binding and ATPase activities, the dsRNA unwindase/helicase activity. We show that hUAP56 directly contacts U4 and U6 snRNAs and promotes unwinding of the U4/U6 duplex, and that both of these activities require U2AF65. Thus, U2AF65 is required to confer essential specificity to hUAP56 during both prespliceosome assembly, in which it recruits hUAP56 to the pre-mRNA branchpoint, and spliceosome assembly, in which it directs hUAP56 to contact U4/U6 snRNAs. Collectively, our results indicate that hUAP56 facilitates multiple steps of spliceosome assembly through distinct mechanisms.

hUAP56 mediates unwinding of the U4/U6 duplex

We found that during mature spliceosome assembly hUAP56 directly contacts U4 and U6 snRNAs, and provide evidence that hUAP56 can promote unwinding of the U4/U6 duplex. We note that previous studies have implicated other DExD/H-box proteins, in particular Brr2 (Laggerbauer et al. 1998; Raghunathan and Guthrie 1998; Kim and Rossi 1999), as candidates for mediating unwinding of the U4/U6 duplex. It is possible that during splicing more than one DExD/H-box protein participates in unwinding of the U4/U6 duplex. In this regard, U2AF65-mediated recruitment of hUAP56 to the branchpoint region may be particularly important for the rearrangement of U2–U6 snRNA interactions in the region during the prespliceosome to spliceosome transition.

As described above, the ability of hUAP56 to contact U4/U6 snRNAs and unwind the U4/U6 duplex is dependent on U2AF65. We note that a previous study reported that U2AF65 did not affect the ability of purified, recombinant hUAP56 to mediate unwinding of an artificial, short RNA duplex in the absence of other splicing factors (Shen et al. 2007). There are several plausible explanations for the differential requirement of U2AF65 in the two studies. In particular, U2AF65 may be dispensable for unwinding short, artificial dsRNA substrates but required for unwinding the natural U4/U6 snRNA duplex in the context of the authentic U4/U6 snRNP. Alternatively, the difference may be attributable to the presence or absence of NE; for example, other splicing factors in the NE may establish a requirement for U2AF65 in U4/U6 duplex unwinding. Relatedly, the unwinding activity observed by Shen et al. (2007) required a high concentration of recombinant hUAP56, which likely far exceeds that in HeLa NE. Finally, it may be relevant that Shen et al. (2007) used a U2AF65 derivative lacking 63 N-terminal amino acids, whereas we used full-length U2AF65.

A new role for ATP hydrolysis in the function of a DExD/H-box protein

It has been previously shown that DExD/H-box proteins can use ATP hydrolysis to promote two reactions: RNA–RNA unwinding (Laggerbauer et al. 1998; Raghunathan and Guthrie 1998; Wagner et al. 1998; Wang et al. 1998) and RNA–protein dissociation (Fairman et al. 2004). Here we show that hUAP56 uses ATP hydrolysis to promote a protein–protein interaction, which to our knowledge is unprecedented. For several DExD/H-box proteins, including hUAP56 (Shen et al. 2007), ATPase activity is stimulated by RNA. Thus, an attractive possibility is that during spliceosome assembly, contacts between hUAP56 and an RNA would stimulate ATP hydrolysis, enhancing the hUAP5–U2AF65 interaction and thereby stabilizing the association of hUAP56 with the splicing complex. The mechanistic basis for the ATP dependence of the hUAP56–U2AF65 interaction remains to be determined. One possibility is that ATP hydrolysis changes the conformation of hUAP56 to a form that can interact with U2AF65. Although such a role for ATP hydrolysis has not been previously observed, we speculate that it may represent a more general paradigm for regulating interactions between DExD/H-box proteins and their RNA or protein targets.

Materials and methods

Immunodepletion of hUAP56

hUAP56-depleted nuclear extract was prepared by incubating 150 μL of HeLa nuclear extract at 4°C with 50 pg of affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal α-hUAP56 antibody (generated by AnaSpec against purified human UAP56 protein) cross-linked to 25 μL of protein A beads (Pierce). After 2 h of incubation, the beads were separated from the extract by centrifugation. The degree and specificity of hUAP56 depletion were monitored by immunoblot analysis for hUAP56 and U2AF65. For immunodepletion of hUAP56 from U2AF-depleted extract, U2AF-depleted nuclear extract was first generated by chromatography on oligo(dT)-cellulose as described previously (Valcarcel et al. 1997).

hUAP56 expression and purification by gel filtration

hUAP56 was expressed as a GST fusion protein in E. coli strain BL21(DE3) and purified as described previously (Shen et al. 2007). Briefly, GST-hUAP56 was first purified on glutathione resin and, after thrombin-mediated cleavage of the GST tag, hUAP56 was further purified using a Superdex 200 size exclusion column. Mutant hUAP56 derivatives were generated by the QuikChange Site Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene).

Circular dichroism spectroscopy

Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy was performed on a Jasco-810 spectrometer using 0.6 mg/mL protein in 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and 100 mM NaCl. Temperature-induced denaturation was monitored by CD at a wavelength of 222 nm using 0.6 mg/mL protein from 20°C to 80°C. CD data points were taken at 1°C intervals at a scan rate of 60°C per hour.

In vitro splicing assays and spliceosome assembly reactions

For splicing reactions, 2 μL of hUAP56-depleted or mock-depleted nuclear extract was used per splicing reaction in a final volume of 10 μL, and splicing reactions were performed essentially as described previously (Fleckner et al. 1997) using a plasmid-encoded Minx (Ad ML) (Zillmann et al. 1988) or β-globin (Krainer et al. 1984) substrate and hUAP56 at a protein concentration of 0.1 μM.

Spliceosome assembly reactions were performed essentially as described previously (Kan and Green 1999). Spliceosomal complexes H, A, B, and C were resolved on nondenaturing 4% acrylamide:bisacrylamide (80:1)/0.5% low-melting agarose (LMA) in 50 mM Tris base/50 mM glycine buffer (Wu and Green 1997); spliceosomal complexes H and E were separated on a 1.5% LMA gel in 0.5× TBE (Das and Reed 1999). Signals were visualized by PhosphorImager (FujiFilm FLA-5000 imaging system). U2AF-depleted nuclear extract was generated by chromatography on oligo(dT)-cellulose as described previously (Valcarcel et al. 1997). Inactivation of U2 snRNA in the ΔUAP56NE by RNase H-directed cleavage was performed as described previously (Shen et al. 2004). To deplete ATP, the ΔUAP56NE was preincubated for 30 min at 30°C.

Affinity purification of splicing complexes

For affinity purification of RNA–protein complexes, a biotinylated Ad ML pre-mRNA substrate (100 fmol) was incubated with HeLa nuclear extract (64 μL in a total volume of 100 μL) and 0.1 μM purified hUAP56 protein for 20 min under conditions that allow spliceosome formation, after which heparin (200 ng/μL; Sigma) was added to stop the splicing reaction. The reaction mixture was then incubated with streptavidin-agarose beads (Pierce) and washed five times (for 10 min each) in buffer R (20 mM Tris-HC1 at pH 7.8, 0.1% Triton X-100, 150 mM KC1, 2.5 mM EDTA). Affinity-purified complexes were then digested with RNase A (Roche) to release the bound proteins, which were analyzed for the presence of hUAP56 by immunoblotting using a polyclonal α-hUAP56 antibody (Fleckner et al. 1997).

GST pull-down assays

The GST-U2AF65 fusion protein was expressed in E. coli strain BL21 and purified as described previously (Valcarcel et al. 1996). For the pull-down assay, 1 μg of GST-U2AF65 fusion protein and 0.5 μg of purified hUAP56 protein were incubated in 100 μL of Buffer D (25 mM HEPES at pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 0.05% Nonidet NP-40, 5 mM DTT, 10% glycerol, 50 μg/mL bovine serum albumin) supplemented with 2 mM MgCl2 for 20 min at 30°C in the presence of 0.5 mM ATP (Promega), ATP-γS (Sigma), ADP (Sigma), or GTP (Promega). Following incubation, 10 μL of glutathione agarose (Pierce) was added to the reaction mixture, and the beads were washed five times in Buffer D. Bound proteins were eluted by boiling in protein loading buffer, separated by SDS-PAGE, and analyzed by immunoblotting using a polyclonal α-hUAP56 antibody (Fleckner et al. 1997).

UV cross-linking/immunoprecipitation assays

Purified hUAP56, hUAP56 mutant derivatives, or GST-U2AF65 were added to nuclear extract depleted of hUAP56 and/or U2AF at a final concentration of 0.8 μM. Where indicated, Ad ML pre-mRNA substrate was added to the NE, and ATP was depleted by pre-incubating the nuclear extract for 30 min at 30°C. The splicing reaction mixture was then irradiated with UV light (254 nm) and incubated with 10 μL of α-hUAP56 polyclonal antibody (generated by Anaspec) for 2 h at 4°C, followed by addition of 15 μL of anti-rabbit IgG agarose beads (Pierce) and incubation for an additional 2 to 3 h at 4°C with continuous mixing on a rotator device. The beads were washed four times with high salt buffer (500 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 50 mM Tris-Cl at pH 8.0), and, following Protease K treatment and phenol extraction, RNA was precipitated by ethanol. The precipitated RNAs were detected by primer extension analysis as described previously (Valcarcel et al. 1996).

Native gel hybridization assays

Splicing reactions were performed as described above in the presence or absence of Ad ML pre-mRNA, and total RNA was purified from the reaction mixture by phenol extraction and ethanol precipitation. To generate U4 and U6 probes, oligonucleotides (U6, AAAATATAACTCTTCACGAATTTGCGTG; U4, AGAGACTGTCTCAAAAATTGCCAA) were kinase-labeled with 32P-ATP and gel purified before use. Native gel hybridization assays were carried out as previously described (Kim and Rossi 1999). Briefly, 2.5 μg of total RNA was incubated with 5 nM 32P-labeled probe and vacuum-dried without heat. The dried RNA and probe mixture was then dissolved in 6 μL of hybridization buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.4, and 1 mM EDTA) and incubated with total RNA for 15 min at 37°C. The annealing reactions were stopped by chilling in ice, and then mixed with 6 μL of loading dye and electrophoresed on a 9% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel with 1× TBE buffer at 175 V in a cold room.

Psoralen cross-linking

Psoralen cross-linking reactions were carried out in 40% nuclear extract in the presence of unlabeled Ad ML pre-mRNA under conditions that promote splicing as described previously (Wassarman and Steitz 1992). At 20 min following the start of the splicing reaction, 4′-aminomethyl-4,5′,8-trimethyl psoralen (Sigma) was added to a final concentration of 20 μg/mL. The reaction mixture was UV-irradiated (365 nm) for 10 min on ice to generate RNA–RNA cross-links, and then deproteinized with proteinase K treatment followed by phenol-chloroform (1:1) extraction and ethanol precipitation to isolate RNA. To identify the snRNA involved in potential RNA–RNA cross-links, isolated RNA was analyzed on a 4% denaturing polyacrylamide gel and subjected to Northern blot analysis using the U4 and U6 probes mentioned above.

Acknowledgments

We thank Woo Keun Song, Jang-Soo Chun, Hyon E. Choy, and their laboratory members for providing laboratory space and technical support, and Sara Evans for editorial assistance. This work was supported in part by a Dasan Young Faculty Grant from Gwangju Institute of Science and Technology, and the Brain Korea 21 Project Research Foundation to H.S. and X.Z.; an American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant and an American Cancer Society Research Scholar Grant to R.Z.; and a National Institutes of Health Grant to M.R.G. R.Z. is a V Scholar and a Kimmel Scholar, and M.R.G. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Article is online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.1657308.

References

- Benz J., Trachsel H., Baumann U. Crystal structure of the ATPase domain of translation initiation factor 4A from Saccharomyces cerevisiae—The prototype of the DEAD box protein family. Structure. 1999;7:671–679. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(99)80088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caruthers J.M., McKay D.B. Helicase structure and mechanism. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2002;12:123–133. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00298-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordin O., Banroques J., Tanner N.K., Linder P. The DEAD-box protein family of RNA helicases. Gene. 2006;367:17–37. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das R., Reed R. Resolution of the mammalian E complex and the ATP-dependent spliceosomal complexes on native agarose mini-gels. RNA. 1999;5:1504–1508. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299991501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eperon I.C., Makarova O.V., Mayeda A., Munroe S.H., Caceres J.F., Hayward D.G., Krainer A.R. Selection of alternative 5′ splice sites: Role of U1 snRNP and models for the antagonistic effects of SF2/ASF and hnRNP A1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:8303–8318. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.22.8303-8318.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairman M.E., Maroney P.A., Wang W., Bowers H.A., Gollnick P., Nilsen T.W., Jankowsky E. Protein displacement by DExH/D “RNA helicases” without duplex unwinding. Science. 2004;304:730–734. doi: 10.1126/science.1095596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleckner J., Zhang M., Valcarcel J., Green M.R. U2AF65 recruits a novel human DEAD box protein required for the U2 snRNP–branchpoint interaction. Genes & Dev. 1997;11:1864–1872. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.14.1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatfield D., Le Hir H., Schmitt C., Braun I.C., Kocher T., Wilm M., Izaurralde E. The DExH/D box protein HEL/UAP56 is essential for mRNA nuclear export in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 2001;11:1716–1721. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00532-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herold A., Teixeira L., Izaurralde E. Genome-wide analysis of nuclear mRNA export pathways in Drosophila. EMBO J. 2003;22:2472–2483. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertel K.J., Graveley B.R. RS domains contact the pre-mRNA throughout spliceosome assembly. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2005;30:115–118. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan J.L., Green M.R. Pre-mRNA splicing of IgM exons M1 and M2 is directed by a juxtaposed splicing enhancer and inhibitor. Genes & Dev. 1999;13:462–471. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.4.462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D.H., Rossi J.J. The first ATPase domain of the yeast 246-kDa protein is required for in vivo unwinding of the U4/U6 duplex. RNA. 1999;5:959–971. doi: 10.1017/s135583829999012x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krainer A.R., Maniatis T., Ruskin B., Green M.R. Normal and mutant human β-globin pre-mRNAs are faithfully and efficiently spliced in vitro. Cell. 1984;36:993–1005. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laggerbauer B., Achsel T., Luhrmann R. The human U5-200kD DEXH-box protein unwinds U4/U6 RNA duplices in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1998;95:4188–4192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder P. Dead-box proteins: A family affair–active and passive players in RNP-remodeling. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:4168–4180. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo M.L., Zhou Z., Magni K., Christoforides C., Rappsilber J., Mann M., Reed R. Pre-mRNA splicing and mRNA export linked by direct interactions between UAP56 and Aly. Nature. 2001;413:644–647. doi: 10.1038/35098106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meignin C., Davis I. UAP56 RNA helicase is required for axis specification and cytoplasmic mRNA localization in Drosophila. Dev. Biol. 2008;315:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghunathan P.L., Guthrie C. RNA unwinding in U4/U6 snRNPs requires ATP hydrolysis and the DEIH-box splicing factor Brr2. Curr. Biol. 1998;8:847–855. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(07)00345-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocak S., Linder P. DEAD-box proteins: The driving forces behind RNA metabolism. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;5:232–241. doi: 10.1038/nrm1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengoku T., Nureki O., Nakamura A., Kobayashi S., Yokoyama S. Structural basis for RNA unwinding by the DEAD-box protein Drosophila Vasa. Cell. 2006;125:287–300. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen H., Kan J.L., Green M.R. Arginine-serine-rich domains bound at splicing enhancers contact the branchpoint to promote prespliceosome assembly. Mol. Cell. 2004;13:367–376. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00025-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J., Zhang L., Zhao R. Biochemical characterization of the ATPase and helicase activity of UAP56, an essential pre-mRNA splicing and mRNA export factor. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:22544–22550. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702304200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H., Cordin O., Minder C.M., Linder P., Xu R.M. Crystal structure of the human ATP-dependent splicing and export factor UAP56. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2004;101:17628–17633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408172101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman E., Edwalds-Gilbert G., Lin R.J. DExD/H-box proteins and their partners: Helping RNA helicases unwind. Gene. 2003;312:1–16. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(03)00626-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staley J.P., Guthrie C. Mechanical devices of the spliceosome: Motors, clocks, springs, and things. Cell. 1998;92:315–326. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80925-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valcarcel J., Gaur R.K., Singh R., Green M.R. Interaction of U2AF65 RS region with pre-mRNA branch point and promotion of base pairing with U2 snRNA. Science. 1996;273:1706–1709. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5282.1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valcarcel J., Martinez C., Green M.R. Functional analysis of splicing factors and regulators. In: Richter J.D., et al., editors. mRNA formation and function. Academic Press; New York: 1997. pp. 31–53. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner J.D., Jankowsky E., Company M., Pyle A.M., Abelson J.N. The DEAH-box protein PRP22 is an ATPase that mediates ATP-dependent mRNA release from the spliceosome and unwinds RNA duplexes. EMBO J. 1998;17:2926–2937. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.10.2926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Wagner J.D., Guthrie C. The DEAH-box splicing factor Prp16 unwinds RNA duplexes in vitro. Curr. Biol. 1998;8:441–451. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70178-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassarman D.A., Steitz J.A. Interactions of small nuclear RNA’s with precursor messenger RNA during in vitro splicing. Science. 1992;257:1918–1925. doi: 10.1126/science.1411506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S., Green M.R. Identification of a human protein that recognizes the 3′ splice site during the second step of pre-mRNA splicing. EMBO J. 1997;16:4421–4432. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.14.4421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H., Hasman R.A., Young K.M., Kedersha N.L., Lou H. U1 snRNP-dependent function of TIAR in the regulation of alternative RNA processing of the human calcitonin/CGRP pre-mRNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:5959–5971. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.17.5959-5971.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zillmann M., Zapp M.L., Berget S.M. Gel electrophoretic isolation of splicing complexes containing U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1988;8:814–821. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.2.814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]