Abstract

Schizosaccharomyces pombe Crb2 is a checkpoint mediator required for the cellular response to DNA damage. Like human 53BP1 and Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rad9 it contains Tudor2 and BRCT2 domains. Crb2-Tudor2 domain interacts with methylated H4K20 and is required for recruitment to DNA dsDNA breaks. The BRCT2 domain is required for dimerization, but its precise role in DNA damage repair and checkpoint signaling is unclear. The crystal structure of the Crb2–BRCT2 domain, alone and in complex with a phosphorylated H2A.1 peptide, reveals the structural basis for dimerization and direct interaction with γ-H2A.1 in ionizing radiation-induced foci (IRIF). Mutational analysis in vitro confirms the functional role of key residues and allows the generation of mutants in which dimerization and phosphopeptide binding are separately disrupted. Phenotypic analysis of these in vivo reveals distinct roles in the DNA damage response. Dimerization mutants are genotoxin sensitive and defective in checkpoint signaling, Chk1 phosphorylation, and Crb2 IRIF formation, while phosphopeptide-binding mutants are only slightly sensitive to IR, have extended checkpoint delays, phosphorylate Chk1, and form Crb2 IRIF. However, disrupting phosphopeptide binding slows formation of ssDNA-binding protein (Rpa1/Rad11) foci and reduces levels of Rad22(Rad52) recombination foci, indicating a DNA repair defect.

Keywords: Checkpoint mediator, crystal structure, histone code, phosphopeptide binding

The eukaryotic cellular response to DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) depends upon a conserved network of interacting proteins that can be roughly partitioned into three functional layers (Melo and Toczyski 2002; Harrison and Haber 2006; Su 2006). Innermost are the primary DNA damage sensors, which include the PIKK kinases and complexes DNA-PKcs—Ku70–Ku80, ATM/Tel1, and ATR/Rad3/Mec1–ATRIP/Rad26/Ddc2, the Mre11/Rad32–Rad50–Nbs1/Xrs2 complex, and the heterotrimeric checkpoint clamp Rad9–Rad1–Hus1 (Ddc1–Rad17– Mec3 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae) (Sancar et al. 2004). These interact with damaged DNA directly or via cofactors such as the ssDNA-binding protein RPA (Zou and Elledge 2003), activating the PIKK components, which semiredundantly phosphorylate themselves (Bakkenist and Kastan 2003), each other (Stiff et al. 2006), and a plethora of other targets, including the highly conserved SQ motif at the C terminus of the histone variant H2AX (H2A.1 or H2A.2 in Schizosaccharomyces pombe, H2A in S. cerevisiae) (Downs et al. 2000; Stiff et al. 2004).

The outermost “effector” layer is provided by the checkpoint kinases, Chk1 and Chk2/Cds1/Rad53 (Bartek and Lukas 2003), which phosphorylate a broad range of substrates, including Cdc25 phosphatases (Bartek and Lukas 2001; Ahn et al. 2003), Pds1/securin (Wang et al. 2001), p53 (Hirao et al. 2000), BRCA1 (Lee et al. 2000), and E2F1 (Stevens et al. 2003), and thereby communicate with the cellular mechanisms regulating cell cycle and (in multicellular eukaryotes) apoptosis.

Connecting and communicating between the DNA damage sensors and effectors are a group of adaptor or mediator proteins that commonly contain tandem repeats of the BRCT domain, first identified in S. pombe Rad4 (Fenech et al. 1991; Lehmann 1993) and subsequently in the C-terminal region of the breast-cancer-associated DNA damage mediator protein BRCA1 (Bork et al. 1997; Callebaut and Mornon 1997). In several cases tandem BRCT pairs have been shown to bind phosphorylated peptides (Manke et al. 2003), but it is far from clear that this is a general property. Central to the DNA damage checkpoint are the Rad9p/53BP1 proteins: 53BP1 in mammals, Crb2 in S. pombe, and Rad9p in S. cerevisiae, which was the first checkpoint protein to be identified (Weinert and Hartwell 1988).

While they are central to the cell’s ability to respond to DNA damage, the precise role of the 53BP1/Crb2/Rad9p checkpoint mediator proteins is still poorly understood. The N-terminal region, which is the least conserved between the three homologs, variously contains phosphorylation sites for DNA damage signaling PIKK kinases and cyclin-dependent kinases (Emili 1998; Sun et al. 1998; Vialard et al. 1998; Esashi and Yanagida 1999; Caspari et al. 2002; Schwartz et al. 2002; Nakamura et al. 2005). Toward the C terminus, all three possess a Tudor domain, which in the case of 53BP1 and Crb2 has been shown to interact with methylated lysine residues in histone H3 or H4 (Huyen et al. 2004; Sanders et al. 2004). The extreme C terminus in all three consists of a tandem BRCT repeat. The precise function of this BRCT2 domain in DNA damage repair and checkpoint signaling is unclear. Studies of Rad9p and Crb2 suggest that it provides an essential dimerization function (Soulier and Lowndes 1999; Du et al. 2004), but one that can apparently be replaced by a heterologous dimerization domain. The mammalian equivalent provides a binding site for the DNA-binding domain of p53, but does not appear to play a role in the functionally important self-association of 53BP1 (Ward et al. 2006).

To gain some insight into the biological roles of the BRCT domains in these checkpoint mediators, we determined the crystal structure of the C-terminal BRCT repeat region of Crb2, alone and in complex with a phosphorylated H2A.1 peptide. We used the structural information to generate Crb2 mutants that specifically disrupt Crb2 dimerization or γ-H2A.1 interaction in vitro and characterized the effects of these mutations on cellular responses to DNA damage in vivo, revealing distinct and separable functions of the BRCT2 domain in checkpoint signaling and in DNA repair.

Results

Crystal structure of Crb2–BRCT2

A construct comprising the C-terminal tandem BRCT repeat of S. pombe Crb2/Rhp9 (Crb2–BRCT2) (residues 537–778) was expressed and purified as previously described (Hinks et al. 2003). Diffracting crystals of selenomethionine-substituted protein were grown in a high-salt condition in the presence of a lanthanide additive. The structure was phased by single-wavelength anomalous diffraction (SAD) and refined at 2.4 Å resolution. Cocrystals of Crb2–BRCT2 and a phosphopeptide corresponding to the C terminus of S. pombe H2A.1 were grown under a low-salt condition and the complex structure refined at 3.1 Å ((Table 1).

Table 1.

X-ray data collection and refinement statistics

The Crb2–BRCT2 structure consists of two sequentially consecutive α-β-α domains with a topology very similar to previously characterized BRCT domains. The two BRCT domains have a head-to-tail arrangement so that the single α-helix on one face of the N-terminal BRCT domain packs against two α-helices on the opposite face of the C-terminal BRCT domain. The outer face of the C-terminal BRCT domain is devoid of helical structures and consists of two loop segments that lack secondary structure, make few crystal contacts, and are relatively poorly ordered (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Structure of Crb2–BRCT2 domain. (A) The Crb2–BRCT2 domain consists of a tandem repeat of BRCT subdomains connected by a linker. The protein chain is rainbow-colored N (blue) → C (red); disordered loops are shown as dotted lines. All molecular graphics were generated with MacPyMOL (DeLano Scientific LLC). (B) Crb2–BRCT2 forms a head-to-tail dimer, with the main interface provided by residues in the inter-BRCT linker segment. (C) Close-up of one half of the dimer interface, showing extensive polar and hydrophobic interactions. The key interface residues Cys663 and Ser666 from one chain are indicated. (D) Analytical gel filtration chromatography of wild-type Crb2–BRCT2 and mutants of dimer interface residues. The wild type elutes early, consistent with a larger dimension due to dimerization, whereas both mutants run later, as monomers.

Dimer formation

Two copies of the Crb2–BRCT2 structure pack against each other to form an intimate symmetric head-to-tail dimer that constitutes the asymmetric unit of the crystal (Fig. 1B). The dimer interface is formed by an extended hairpin loop that acts as an interdomain linker, connecting the C-terminal α-helix of the first BRCT domain and the N-terminal β-strand of the second BRCT domain. The core of the interface is provided by a symmetrical self-complementary network of hydrogen bonding interactions involving the side chain and main chain of Ser666 and the peptide backbones of Leu652, Leu653, Ala654, Thr664, and Gln667. This is reinforced by hydrophobic interactions involving the side chains of Ser649, Pro650, Tyr651, His652, Leu661, Cys663, Thr664, Leu665, and Arg667 (Fig. 1C). Formation of the dimer buries >1800 Å2 of molecular surface.

Previous studies of Crb2 and its budding yeast homolog Rad9p have shown a functional requirement in vivo for dimerization via the C-terminal BRCT2 repeat (Soulier and Lowndes 1999; Du et al. 2004), and we find that the Crb2–BRCT2 construct behaves as a dimer in solution. The large degree of surface area burial in the crystallographic dimer, compared with any other contact observed in the lattice, argues that this is an authentic dimer interaction. However some of the residues involved, especially the polar residues, are not strongly conserved. To verify that the observed interface is indeed required for authentic functional dimerization, we made point mutations in key interfacial residues Cys663 and Ser666 (Fig. 1C), which are designed to completely disrupt the interface, and determined the oligomerization state of the mutant proteins in solution (Fig. 1D). Whereas the wild-type protein migrated as a dimer in a calibrated gel filtration chromatography column, the Ser666Arg and Cys663Arg mutants ran as monomeric species in gel filtration, indicative of disruption of their dimerization. Interestingly mutations in both of these residues, correlating with functional defects, had previously been observed (Willson et al. 1997; Mochida et al. 2004), but the biochemical basis for this was not understood.

Phosphopeptide binding by Crb2

Tandem BRCT domains have been found to act as phosphopeptide binding modules in a range of systems (Manke et al. 2003; Yu et al. 2003). Mdc1, a DNA damage checkpoint mediator in mammalian cells (Stewart et al. 2003), has been conclusively shown to bind specifically to the phosphorylated C-terminal peptide of γ-H2AX (Lee et al. 2005; Stucki et al. 2005). Members of the Rad9p/Crb2/53BP1 family form foci that coincide spatially with and are contingent upon γ-H2AX/H2A focus formation following DNA damage (Schultz et al. 2000; Nakamura et al. 2004; Javaheri et al. 2006; Toh et al. 2006). However it is unclear whether this necessarily involves a direct interaction.

Comparison of the Crb2–BRCT2 crystal structure with that of Mdc1–BRCT2 in complex with a γ-H2AX-derived peptide (Stucki et al. 2005) shows conservation of key residues involved in specific interaction with the phosphorylated H2AX C terminus, suggesting that Crb2–BRCT2 should be competent to bind a similar peptide, derived from the S. pombe ortholog H2A.1.

We tested the ability of Crb2–BRCT2 to interact specifically with γ-H2A by coprecipitation using a biotinylated peptide derived from the C terminus of the S. pombe H2AX ortholog, H2A.1 (identical over the last seven residues to the other S. pombe homolog H2A.2) (Fig. 2A). Streptavidin beads efficiently precipitated Crb2–BRCT2 in the presence of peptide phosphorylated at the equivalent of H2A.1 Ser129. Addition of λ-phosphatase abolished Crb2–BRCT2 precipitation, showing that the interaction was specific to the phosphorylated form of H2A.1. Although a phosphoserine is essential, the interaction is specific to the surrounding sequence, and a related but different phosphopeptide derived from human H2AX was bound far less tightly (Supplemental Fig. 1).

Figure 2.

γ-H2A phosphopeptide binding by Crb2–BRCT2. (A) Coprecipitation of Crb2–BRCT2 by a biotinylated S. pombe histone H2A.1-derived C-terminal peptide phosphorylated on Ser129. Pretreatment with λ phosphatase abolishes the interaction. (I) Crb2–BRCT2 protein 10% input loaded. (B) Crystal structure of Crb2–BRCT2 with γ-H2A peptide bound in a cleft at the junction of the two BRCT subdomains. (C) Interactions between Crb2 (blue carbons) and γ-H2A (orange carbons). γ-H2A makes multiple hydrogen bonding (dashed lines) to main and side chains of Crb2 (see text), with the side chain of the C-terminal residue Leu132 interacting with a hydrophobic recess. (D) Charge complementarity between the acidic γ-H2A phospho-peptide and a basic patch (blue) on the surface of Crb2, generated by Arg558, Arg616, Lys617, and Lys619. (E) Comparison of Crb2–γ-H2A complex with that of the mammalian mediator, Mdc1 bound to γ-H2AX. Although the two proteins are substantially diverged, the bound peptide conformation is similar, and many interacting residues are conserved.

Based on this we sought to determine the structural basis of the interaction. Cocrystals were obtained in a low-salt condition with a phosphopeptide corresponding to the common C-terminal six residues of H2A.1/H2A.2, which showed clear density in difference Fourier maps in which the bound phosphopeptide can be defined (Fig. 2B). The phosphate group attached to γ-H2A.1 pSer129 binds in a small basic pocket and makes polar interactions with the side and main chains of Ser548 and Lys619, the peptide nitrogen of Gly549, and a water bridged interaction with the guanidinium head group of Arg558 (Fig. 2C). The side chain of γ-H2A.1 Glu131 is also well ordered and makes a hydrogen bonding interaction with the side chain of Lys617, which threads between the acidic side chains of γ-H2A.1—Glu131 and pSer129. The peptide carbonyl between γ-H2A.1 pSer129 and Gln130 hydrogen bonds to the peptide nitrogen of Val618, but the side chain of γ-H2A.1 Gln130 is directed out into solvent, makes no contacts, and is poorly ordered. The C-terminal Leu132 is directed into a hydrophobic recess provided by Leu621 and Val767. The acidic α-carboxyl itself makes no evident direct hydrogen bonds, but is close to the head group of Arg616 and would make a favorable ionic interaction. The surface electrostatic potential of Crb2–BRCT2 shows a very basic patch, complementary to the strong negative charge of the γ-H2A.1 C-terminal peptide (Fig. 2D).

Although the detailed structures of Mdc1–BRCT2 and Crb2–BRCT2 are substantially diverged, their interactions with γ-H2AX and γ-H2A.1 C-terminal peptides, respectively, have many similarities. The conformation of the bound peptides is similar (Fig. 2E), and in both cases the predominant interactions with the phosphorylated peptide are furnished by residues in the loop leading in to the final α-helix of the first BRCT domain. Crb2 residues Ser548 and Lys619, which interact with the γ-H2A.1 pSer129 phosphate, have direct functional counterparts in Mdc1 residues Thr898 and Lys936. Similarly Crb2 Arg616, which provides an ionic interaction with the α-carboxyl of the histone, corresponds to Arg933 in Mdc1. However the hydrogen bonding interaction between the side chains of γ-H2A.1 Glu131 and Crb2 Lys617 and the water-bridged ionic interaction between the histone phosphoserine phosphate group and Crb2 Arg558 have no counterparts in Mdc1.

To verify these interactions, we made a series of point mutations of some of the residues involved and determined their ability to be coprecipitated by the biotinylated γ-H2A.1 peptide (see above). Mutation of Arg558 had a general destabilizing effect on the domain, consistent with general loss of function, and in the absence of any positive control for its functional integrity it was not considered in further analyses. Consistent with their observed structural roles, charge reversal mutations Arg616Glu, Lys617Glu, and Lys619Glu all abolished Crb2–BRCT2 interaction with the peptide (Fig. 3A), but had no effect on dimerization of the mutant proteins (Fig. 3B). Conversely, mutations disrupting dimerization did not disrupt γ-H2A.1 binding (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

Targeted disruption of γ-H2A binding by Crb2–BRCT2. (A) Coprecipitation of wild-type and mutant Crb2–BRCT2 by a biotinylated S. pombe histone H2A.1-derived C-terminal peptide phosphorylated on Ser129. (I) 10% input; (+) peptide included; (−) a beads-only negative control using the wild-type protein. Charge-reversal mutation of any of the key basic residues abrogated phosphopeptide binding. (B) Analytical gel filtration chromatography of wild-type Crb2–BRCT2 and charge-reversal mutants. Abrogation of phosphopeptide binding does not disrupt dimerization, and all mutants elute early from the column. Compare with Figure 1D for the dimerization–disruption mutants. (C) Coprecipitation of the dimerization–disruption mutants S666R and C663R by the H2A.1 phosphopeptide. (I) 10% input; (+) peptide included; (−) beads-only negative control. Loss of dimerization in either of these mutants does not disrupt their ability to bind the phosphopeptide.

In vivo functions of Crb2–BRCT2 dimerization and γ-H2A.1 binding in DNA damage resistance and checkpoint

The involvement of Crb2 in DNA damage checkpoint signaling is well established (Saka et al. 1997; Willson et al. 1997), with the BRCT2 domain required for homo-oligomerization, colocalization with γ-H2A, hyperphosphorylation, and activation of downstream targets (Du et al. 2004; Nakamura et al. 2004). With the mechanistic insights into dimerization and interaction with γ-H2A.1 provided by the crystal structure, we are now able to begin to dissect the interrelationship of these different functions of Crb2–BRCT2 and how they signal into DNA damage checkpoint and repair pathways.

We engineered the same series of charge-reversal mutations (see above) into the authentic chromosomal location in S. pombe in vivo and determined their effects on sensitivity to a range of genotoxic insults and DNA damage checkpoint signaling. We observed distinct differences in phenotypes elicited by those mutations that disrupt BRCT2 dimerization and those that disrupt γ-H2A.1 binding. The dimerization–disruption mutations rendered cells sensitive to DNA damage by ionizing or UV radiation and to the effects of DNA replication poisons hydroxyurea (HU) and camptothecin (CPT), which cause replication fork collapse (Fig. 4A,B). By contrast, γ-H2A.1-binding mutations conferred little sensitivity to UV, HU, or CPT but rendered the cells slightly sensitive to ionizing radiation (IR) (Fig. 4C,D).

Figure 4.

Differential sensitivity to DNA damage of BRCT2 dimerization and γ-H2A binding mutants. (A) Spot tests of Crb2–BRCT2 dimerization mutant strains. Seven microliters of 10-fold serially diluted exponentially growing cells were plated onto YE agar containing genotoxins as indicated or irradiated with UV (150 J/m2) and incubated at 30°C for 3 d. (B) Response to IR by Crb2-dimerization mutant strains. Exponentially growing cells exposed to a range of doses of IR were plated on YEA agar, and colonies were counted after 3 d at 30°C. (C) As A, but for Crb2–BRCT2 γ-H2A phosphopeptide-binding mutants. The crb2+ and crb2-d controls for these data from the same experiment are shown in A. (D) As in B, but for Crb2–BRCT2 γ-H2A phosphopeptide-binding mutants.

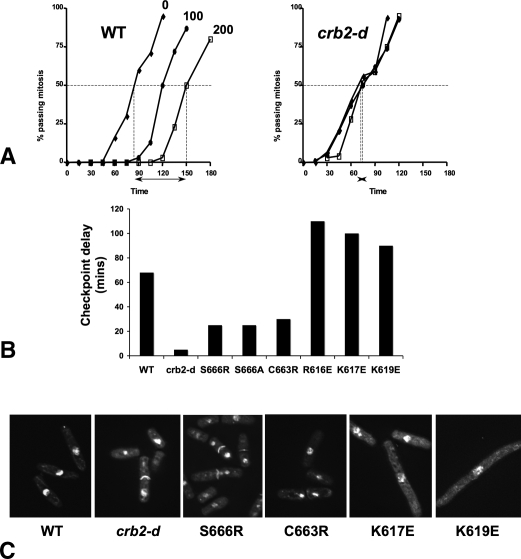

We next determined the effect of the mutations on the checkpoint response to DNA damage by measuring the percentage of cells passing through mitosis in nonirradiated and irradiated synchronous cultures (al-Khodairy and Carr 1992). In this assay, with a radiation dose of 200 Gy, wild-type cells entered mitosis on average 65–70 min later than unirradiated cells, while crb2-d cells entered mitosis with kinetics similar to unirradiated cells (Fig. 5A). As with sensitivity to DNA damage, the two classes of BRCT2 mutations produced quite different effects on the damage checkpoint. Strains with dimerization–disruption mutations displayed substantially reduced cell cycle arrests (∼15–30 min), compared with wild type, although not as severe as the null mutant. In marked contrast, the γ-H2A.1-binding mutants, rather than having defective checkpoint responses, show a substantially extended arrest, ∼1.5 times the wild type (Fig. 5B). This extended mitotic arrest is accompanied by a very elongated cell phenotype not seen in the checkpoint-deficient dimerization mutants, which have a “cut” morphology after irradiation (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

Different DNA damage checkpoint responses of BRCT2 dimerization and γ-H2A binding mutants. (A) DNA damage checkpoint analysis. Synchronously cycling cells were exposed to 0, 100, or 200 Gy IR and the percentage of cells passing mitosis was counted at 15 min intervals. The checkpoint delay is presented as the time interval between 50% of cells passing mitosis in nonirradiated and in 200 Gy irradiated cells (arrows and vertical dashes). Examples are shown for wild-type (left) and a Crb2-deleted (right) strain. (B) Summary of checkpoint delay for wild-type and Crb2-deleted strains and for various Crb2–BRCT2 dimerization and γ-H2A phosphopeptide-binding mutants, which show radically different delays. (C) Phenotype of DAPI-stained cells from B 3 h after exposure to 200 Gy IR. Without irradiation, dimerization mutants are slightly shorter than wild type, while γ-H2A phosphopeptide-binding mutants are a little longer. This is fully consistent with these mutants being deficient in checkpoint and recombination repair, respectively.

As the two mutant classes displayed very different phenotypes, we analyzed the in vivo response of a crb2-S666R,K619E double mutant, disrupted in dimerization and phosphopeptide binding. The double mutant essentially phenocopied the crb2-S666R single mutant, both in its greater IR sensitivity and in its drastically reduced checkpoint delay on irradiation (Supplemental Fig. 2).

Crb2 focus formation and checkpoint kinase activation

In order to gain some insight into where in the downstream responses to DNA damage the Crb2–BRCT2 mutations exerted their effects, we analyzed the ability of the mutants to form Crb2 foci in response to DNA damage and the phosphorylation of the DNA damage signaling protein kinase Chk1 that correlates with its activation. We focused our attention on crb2-S666R and crb2-K619E as representative of the two groups of BRCT mutants. Consistent with results obtained using BRCT-truncation mutants (Du et al. 2004), we observe that Crb2-S666R, defective in BRCT2 dimerization, is unable to form Crb2 foci after exposure of cells to 40 Gy IR (Fig. 6A). As described previously for wild-type cells (Du et al. 2003), a proportion of these Crb2 foci colocalize with Rad22 foci in both wild-type and crb2-K619E cells (Supplemental Fig. 3).

Figure 6.

Ionizing-radiation-induced focus formation. (A) Crb2 focus formation. crb2+ and crb2 mutant cells containing tdTomato-tagged Crb2 irradiated with 40 Gy IR and fixed in methanol after 30 min incubation at 25°C, then stained with DAPI and photographed. Crb2 foci are evident in the wild type and the crb2-K619E γ-H2A phosphopeptide-binding mutant but absent in the Crb2–BRCT2 dimerization mutant, crb2-S666R. (B) Chk1 phosphorylation. Total cell extracts from HA-Chk1-containing cells irradiated with 0, 20, or 100 Gy IR were separated by SDS PAGE and Western blotted with anti-HA antisera. The Crb2-deleted and dimerization disruption strains fail to activate Chk1 regardless of IR dose, whereas Chk1 activation is still observed with the “clean” phosphopeptide-binding mutants R616E and K619E, especially at higher doses. (C) Formation of Rpa1(Rad11) foci. Rpa1(Rad11)-GFP-containing cells were irradiated with 20 Gy IR, and the number of cells containing foci was measured at intervals as indicated. Compared with wild-type and crb2-S666R cells, crb2-K619E mutant cells display a delayed formation of Rpa1 foci, which are formed early in the homologous recombination repair process. (D) Formation of Rad22 foci. Rad22-GFP containing cells were irradiated with 40 Gy IR, and the number of cells containing foci was measured at intervals as indicated. Rad22 foci, which represent active homologous recombination processes, are formed to a lesser degree and are resolved more slowly in the crb2-K619E mutant cells than in the wild type. Statistical analysis (two-tailed t-test) indicates that the differences observed at 30 min, and later at 210 and 240 min are highly significant at the 95% level.

Previous studies using an H2A-AQE mutant (where neither histone H2A homolog can be phosphoryated at the C terminus) and a Crb2 mutant in which the BRCT2 domains were substituted by a heterologous dimerization domain (Du et al. 2004; Nakamura et al. 2004) concluded that focus formation requires both the BRCT domains and an interaction with γ-H2A. However using the crb2-K619E mutant, defective in binding the phosphorylated H2A peptide, we still observe Crb2 focus formation, indicating that γ-H2A binding is not necessary and that Crb2 dimerization and chromatin association via the Tudor domain are sufficient.

In wild-type but not crb2-null cells, Chk1 was phosphorylated after exposure to IR (20 or 200 Gy) (Fig. 6B). In contrast, Chk1 is not phosphorylated in BRCT2 dimerization mutants after exposure to either low or high doses of radiation (Fig. 6B). The γ-H2A.1-binding mutants displayed reduced levels of phosphorylated Chk1 after exposure to IR, particularly at low doses (e.g., at 20 Gy). This is similar to the reduced level of Chk1 phosphorylation observed in the H2A-AQE mutant (Nakamura et al. 2004).

We next sought to identify the nature of the defect leading to reduced Chk1 phosphorylation by analyzing the level of Rpa1 (the S. pombe ortholog of the mammalian ssDNA-binding protein RPA) foci as a measure of ssDNA formation that is required for checkpoint activation (Kornbluth et al. 1992; Lee et al. 1998). We compared the number of Rpa1 foci in wild-type and crb2-K619E cells (Fig. 6C) after exposure of cells to a low dose of radiation (20 Gy). At least 60% of wild-type cells have Rpa1 foci at 7.5–45 min following irradiation. At early time points (7.5 and 15 min) the crb2-K619E mutant has fewer cells with foci compared with wild-type cells, with ∼40% of mutant cells displaying foci. By 30 min the number of cells with foci resemble wild type. Thus the reduced level of ssDNA formation in response to IR DNA damage in crb2-K619E could be responsible for the reduced phosphorylation of Chk1.

γ-H2A.1-binding mutants have altered kinetics of formation of Rad22 foci

The extended checkpoint delay in the γ-H2A.1-binding mutants is in contrast to the observation that the H2A-AQE mutant has a slightly reduced checkpoint delay at high doses (Du et al. 2004). The delay that we observe may be due to a defect in the repair of DNA damage. To investigate this we analyzed the kinetics of formation of foci by Rad22 (homolog of the mammalian Rad52 recombination protein) indicative of DSB repair by homologous recombination. After exposure to 40 Gy IR, the level of Rad22 foci in BRCT2 dimerization mutant crb2-S666R was similar to that observed in wild-type cells (data not shown). However, in the γ-H2A.1-binding mutant crb2-K619E, the number of Rad22 foci is reduced at 30 and 60 min post-irradiation compared with wild-type cells but persists at a slightly higher level at later time points (Fig. 6D), consistent with a defect in DNA repair. These data correlate with the observation of reduced levels of Rpa1 (and hence presumed presence of ssDNA) in these mutants.

Discussion

Separation of BRCT2 domain functions

The structure of the Crb2–BRCT2 domain reveals the structural basis for dimerization and for interaction with γ-H2A, both of which fulfill important functions in the biological role of Crb2 as a DNA damage checkpoint mediator. Using the structure as a guide, we generated mutants in which these functions are biochemically distinguished, and we have used these to demonstrate a clear separation in the biological roles of the BRCT2 domain of Crb2.

Recruitment of Crb2 to chromatin and formation of IR-induced foci (IRIFs) have been shown previously to require the ability to dimerize (Du et al. 2004) and the Tudor and BRCT domains (Du et al. 2006). We show here that, as expected, the dimerization-defective Crb2-S666R protein does not form IRIFs and does not activate Chk1, resulting in a greatly reduced cell cycle arrest. However loss of dimerization had little effect on the ability of the cells to instigate DNA repair, as judged by the formation of Rad22 homologous recombination foci in the crb2-S666R cells.

In contrast, the Crb2-K619E mutation, which disrupted γ-H2A binding, did not prevent Crb2 focus formation after exposure of cells to IR or the ability to mount a checkpoint response but did affect some aspects of DNA repair, as indicated by slower development of Rpa1-coated ssDNA foci and Rad22 recombination foci. This decreased rate of DNA repair is reflected in the extended DNA damage checkpoint and elongated phenotypes we observe in the γ-H2A-binding mutants. The effect of the Crb2-K619E mutation, which prevents Crb2 binding to γ-H2A, is clearly different from the effect of the H2A-AQE mutants, which prevent phosphorylation of H2A and prevent formation of Crb2 foci immediately after exposure to IR (Du et al. 2006). The difference in Crb2 and Rad22 focus formation and DNA repair by the Crb2-K619E and H2A-AQE mutants has two important implications: (1) that the checkpoint signal represented by C-terminal phosphorylation of H2A is probably not mediated solely by binding of γ-H2A to Crb2–BRCT2 and (2) that γ-H2A is not likely to be the sole phosphopeptide ligand of Crb2–BRCT2.

Mechanistically, the impaired formation of Rpa1 foci and the decreased, but not abolished, activation of Chk1 by Crb2-K619E suggest a possible role for Crb2 in facilitating activation of the MRN (Mre11–Rad50–Nbs1 in mammals and budding yeast; Rad32–Rad50–Nbs1 in S. pombe) complex at DSBs. As well as activating ATM (Dupre et al. 2006) MRN resections DNA at DSBs generating segments of ssDNA that provide binding sites for RPA (Jazayeri et al. 2006; Myers and Cortez 2006). These in turn recruit and activate the ATR/Rad3/Mec1–ATRIP/Rad26/Ddc2 complex (Zou and Elledge 2003) among whose downstream targets are Chk1. While a direct connection between Crb2 and MRN has not been described, MRN in yeast and mammalian cells has recently been found to associate with a different adaptor protein, CtIP (Limbo et al. 2007; Sartori et al. 2007), previously shown to bind in a cell cycle-regulated, phosphorylation-specific manner to the BRCT2 domain of BRCA1 in mammalian cells (Yu and Chen 2004; Varma et al. 2005). As Crb2 subsumes the divergent functions of paralogous mediators such as BRCA1 and 53BP1 in mammalian cells, it is quite conceivable that it also interacts with the fission yeast ortholog of CtIP, Ctip1, in a similar phosphorylation-specific interaction, mediated by its BRCT2 domain. Thus, like BRCA1 (Wang et al. 2007), the Crb2 BRCT2 domain may have multiple phosphorylation-specific binding partners, and the DNA repair defect we observe in the phosphopeptide-binding Crb2 mutants may result at least in part from failure to recruit Ctip1 as well as a loss of γ-H2A interaction.

Crb2–BRCT2 dimerization and chromatin association

Deletion studies (Du et al. 2004) and the point-mutational analysis presented here show that the ability to dimerize, mediated by the BRCT2 domains, is essential for Crb2 to function as a checkpoint mediator. Whether dimerization is a constitutive property of Crb2 or is regulated in response to DNA damage and repair has not so far been addressed. Recombinant Crb2–BRCT2 crystallizes as a dimer and behaves as a dimer in solution under all nondenaturing biochemical conditions to which we exposed it, up to and including molar salt. The hydrophobic surface area buried on dimer formation is substantial, suggesting that, in the absence of other factors, this domain would be constitutively dimeric in vivo. However it was possible to produce stable and soluble monomeric species by single-point mutations in the dimerization interface, indicating at least the possibility of a reversible monomer–dimer transition being regulated by post-translational modification. Crb2–BRCT2 has two S/T-Q motifs (666-SQ and 772-SQ) that could in principle be phosphorylated by a DNA damage signaling PIKK kinase such as ATR/Rad3 or ATM/Tel1, although no such phosphorylation has been reported. Both motifs are involved in the dimer interface, and Ser666 in particular is a key interfacial residue whose mutation totally disrupts dimerization—phosphorylation of Ser666 would certainly have the same effect. However, both SQ sites occur in fully structured regions of the molecule that would not be readily accessible to a PIKK kinase, and both are poorly conserved in Crb2 homologs. The possibility of regulated dimerization therefore remains speculative, and further work will be required to test this.

The mechanistic role that dimerization plays in the biology of Crb2 is unclear. One possibility stems from the fact that the two copies of histone H2A, to whose phosphorylated C termini the Crb2–BRCT2 domain binds, and the two copies of histone H4 to whose dimethylated Lys20 (H4K20me2) the Crb2–Tudor2 domain binds (Sanders et al. 2004) are themselves arranged with dimer symmetry within the nucleosome core. Using the structures of Crb2–BRCT2, the tandem repeat Tudor domain of Crb2 (Botuyan et al. 2006) and the nucleosome core (Luger et al. 1997; Davey et al. 2002), we were able to assemble a model of a dimeric Crb2 complex with a single nucleosome in which all H4K20me2 and γ-H2A interactions could be satisfied, with no significant changes in the conformation or position of the histone core. In this model, the Crb2–BRCT2 dimer is positioned with its diad coincident with the diad of the nucleosome (Fig. 7), with each BRCT2 domain binding the phosphorylated C terminus of one of the two histone H2A tails and the Tudor2 domains disposed on opposite faces of the nucleosome, binding to the the dimethylated side chain of Lys20 of histone H4. In these positions, the structurally visible N terminus of Crb2 BRCT2 (residue 537) and the C terminus of the upstream Tudor2 domain (residue 504) are separated by ∼47 Å, a distance that could be readily traversed by the 34 residues that separate the Tudor2 and BRCT2 domains. Flexibility of the Tudor2–BRCT2 linker segment could potentially allow either or both Tudor2 domains in a Crb2 dimer to access H4K20me2 residues on adjacent nucleosomes in a bridging interaction. However, this would be much less likely for the BRCT2 domains, as the distance between the two γ-H2A-binding sites (∼38 Å) is significantly less than the “thickness” of a nucleosome. Where the necessary modifications are present on the H2A and H3 histone of the same nucleosome, the favorable entropy of a dimer–dimer interaction, together with the avidity effect of multiple binding sites, would favor a complex of this type. The ability of the Crb2 dimer to preferentially interact with nucleosomes bearing dual γ-H2A modifications might provide a mechanism for measuring the effective “density” of γ-H2A in a region of chromatin and establishing a threshold for the damage response. Thus, sporadic formation of γ-H2A is unlikely to occur twice on the same nucleosome, whereas dense formation due to damage amplification would have a high probability of generating a dually modified nucleosome and providing a favored binding site for a Crb2 dimer.

Figure 7.

Crb2 interaction with chromatin. (A) Molecular model of Crb2 dimer docked onto a nucleosome such that the BRCT2 domains can access the C terminus of histone H2A, and the Tudor2 domains can access Lys20 of histone H4. The diad axis of the Crb2–BRCT2 dimer coincides with the diad axis of the nucleosome (red arrow). (B) Perpendicular view, showing the disposition of the two Tudor2 domains from a Crb2 dimer on either face of the nucleosome. The C terminus of the Tudor2 domain (residue 504) and the N terminus of the BRCT2 domain (residue 537) are separated by ∼47 Å (dashed line).

Functional conservation among checkpoint mediators

Despite the fundamental nature of the eukaryotic cell response to DNA damage, Crb2 and its budding yeast and metazoan orthologs Rad9p and 53BP1 show only a low level of sequence conservation. Dimerization of the BRCT domains have been shown to be essential to the biological function of Rad9p and Crb2 (Soulier and Lowndes 1999; Du et al. 2004), and the residues involved in Crb2–BRCT2 dimerization are functionally conserved in Rad9p, albeit with few invariant residues, suggesting that Rad9p dimerizes the same way. The equivalent surface is also conserved to a degree in 53BP1, whose biological function also depends upon oligomerization, but in a BRCT-independent manner (Ward et al. 2006). The structurally aligned sequences (Fig. 8A) show that the topological equivalent to Crb2-Cys663, whose mutation to arginine prevents dimerization, is Arg1858 in 53BP1—an evolutionary change sufficient to abolish constitutive dimerization of 53BP1–BRCT2. Consistent with this, we find the isolated 53BP1–BRCT2 domain is monomeric in solution (Fig. 8C). Although this surface in 53BP1 has evolved away from a homotypic interaction, it provides the binding site for the DNA-binding domain of p53 (Fig. 8B; Derbyshire et al. 2002), which itself homodimerizes and indeed homotetramerizes (Kitayner et al. 2006). A functional requirement for dimerization of the checkpoint mediator may thus have been conserved in the metazoan systems but delivered via the agency of a second protein, reflecting the more complex regulatory requirement of multicellular organisms compared with the unicellular yeasts.

Figure 8.

Comparison of Crb2 and 53BP1. (A) Amino acid sequence alignment of BRCT2 domains from Crb2, human 53BP1, and S. cerevisiae Rad9p. The major functional blocks are highlighted in yellow, with Crb2 residues implicated in dimerization shown in green bold, residues implicated in polar interactions with the phosphopeptide in red bold, and residues involved in hydrophobic interaction with the C-terminal leucine of histone H2A in blue bold. Topologically equivalent residues conserved in 53BP1 and Rad9p are colored accordingly. Arg1858 in 53BP1, which would prevent dimerization of the 53BP1–BRCT2 domain, is bold and underlined. (B) Structural comparison of the Crb2–BRCT2 homodimer (left) with the 53BP1–BRCT2–p53 DNA-binding domain heterodimer (right). The same face of the BRCT2 domain is used for protein–protein interactions in both cases. (C) Analytical gel filtration chromatography of Crb2–BRCT2 and 53BP1–BRCT2 domains. Crb2 runs as a dimer, 53BP1 as a monomer. (D) Coprecipitation of 53BP1–BRCT2 by a biotinylated human histone H2AX-derived C-terminal peptide phosphorylated on Ser140. Pretreatment of the phosphorylated peptide with λ phosphatase abolishes the interaction. (M) Molecular weight markers; (I) 53BP1–BRCT2 protein 10% input loaded.

The interaction between the γ-H2A peptide and Crb2–BRCT2 correspond closely to the interaction previously seen between human Mdc1–BRCT2 and a γ-H2AX peptide (Lee et al. 2005; Stucki et al. 2005), with most of the polar and charged residues involved being conserved. Most of these residues are also conserved in the sequence of budding yeast Rad9p and in the structure of the 53BP1–BRCT2 region, where the equivalent surface patch shows the same strong basic character as in Crb2 (Fig. 8A). It seems likely therefore that the ability to interact with the phosphorylated C terminus of their corresponding H2A orthologs should be a common feature of the Rad9p/Crb2/53BP1 mediator protein family. Indeed while this article was in preparation, Hammet et al. (2007) demonstrated this property in S. cerevisiae Rad9p.

γ-H2AX binding by mammalian 53BP1 remains controversial (Stewart et al. 2003; Ward et al. 2003; Stucki et al. 2005; Xie et al. 2007). In our hands, recombinant 53BP1 can be coprecipitated by a human γ-H2AX peptide in a phosphorylation-dependent manner (Fig. 8D), but at least qualitatively the affinity of the interaction appears weaker than between Crb2 and a γ-H2A peptide. What is not in doubt is that 53BP1–BRCT2 is competent to bind phosphopeptides and conserves the residues required for that ability. It may well prove that a phosphorylated protein other than γ-H2AX is the main target for such an interaction.

Materials and methods

Protein expression and purification

S. pombe Crb2–BRCT2 (residues 537–778) was expressed as an N-terminal His6-tagged protein from the pRSETB vector and purified as described in Hinks et al. (2003). SeMet-substituted Crb2–BRCT2 (Se-Crb2–BRCT2) was expressed in Escherichia coli strain B834(DE3) (Novagen) using the SelenoMet Medium Base plus Nutrient Mix (Molecular Dimensions Limited) and purified as the native protein. Mutants were generated using the QuikChange method (Stratagene) and expressed and purified as wild type. The 53BP1 full-length cDNA (a kind gift from Dr. K. Iwabuchi, Kanazawa Medical University, Japan) was used as a template to PCR the 53BP1 C-terminal tandem BRCT repeat region (Primer 1, 5′-CGAGTCCATATGGCCCTGGAAGAG CAGAGAGGG-3′; Primer 2, 5′-CGTCAGCTCGAGTTAGT GAGAAACATAATCGTG-3′), which was cloned into the NdeI/XhoI sites of vector pTWO-E (Dr. A. Oliver, ICR). 53BP1–BRCT2 (residues 1714–1972) was expressed from E. coli strain Rosetta 2(DE3)pLysS as an N-terminal His6-tagged protein and purified as Crb2–BRCT2.

Dimerization of wild-type and mutant Crb2–BRCT2 was assessed using a calibrated Superdex 75 16/60 gel filtration column (GE Healthcare), pre-equilibrated in 0.05 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), 1.0 M NaCl, and 5 mM DTT. The high-salt concentration of the buffer was required to increase the solubility of Crb2–BRCT2. 53BP1–BRCT2, however, was not susceptible to aggregation at lower salt concentrations, and this protein was additionally analyzed by gel filtration in a buffer containing only 0.2 M NaCl. Similar elution profiles were obtained in both cases.

Crystallization and structure determination

Native and Se-Crb2–BRCT2 (7 mg ⋅ mL−1 in 0.05 M Tris-HCl at pH 7.0, 1 M NaCl, 5 mM DTT) were crystallized by hanging drop vapor diffusion at 20°C. Plate clusters grew from 2 μL of protein, 2 μL of well solution (0.1 M Na-cacodylate at pH 6.5, 7.0% PEG8000, and 0.2 M Ca-acetate) and 0.5 μL of 0.1 M Pr(III) acetate. This high-salt condition was modified to obtain cocrystals of Crb2–BRCT2 and the H2A.1 C-terminal phosphopeptide, KP-pS129-QEL (synthesized by J. Metcalfe, ICR). In this case, Crb2–BRCT2 (3.5 mg × mL−1 in 0.05 M Tris-HCl at pH 7.0, 0.6 M NaCl, 5 mM DTT) was mixed with an equal volume of peptide (0.05 M Tris-HCl at pH 7.0, 0.1 M NaCl, 5 mM DTT) to give a 1:30 molar ratio of protein:peptide. Cocrystals were grown as for the native protein. All crystals were cryoprotected using well solution plus 30% ethylene glycol.

The Crb2–BRCT2 structure was phased using SAD. SAD data for Se-Crb2–BRCT2 crystals were collected on ID14.2 at ESRF. Data were processed and scaled using Mosflm (Leslie 1995) and Scala (Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 1994). The positions of 10 Se atoms + 3 Pr3+ ions were determined using ShelX (Sheldrick 2008) and refined using SHARP (Vonrhein et al. 2007) to give an interpretable electron density map at 2.7 Å resolution. Automated model building was carried out using Resolve (Adams et al. 2004). Manual model building and crystallographic refinement used Coot (Emsley and Cowtan 2004), CNS (Brunger 2007), and Refmac (Murshudov et al. 1997) with native data to 2.3 Å collected on ID23.1 at ESRF. The refined atomic model was used to solve a Crb2–BRCT2: H2A.1 phospho-peptide cocrystal data set to 3.1 Å resolution by molecular replacement using PHASER (McCoy 2007). Crb2–BRCT2:H2A.1 cocrystal data were collected on I03 at Diamond, Oxford. Refined coordinates have been deposited in the PDB with accession codes 2vxb and 2vxc.

Coprecipitation

Coprecipitations were performed with biotinylated phosphopeptide (Biotin-GSGYSGSRTGKP-pS129-QEL) corresponding to the C terminus of S. pombe H2A.1 (University of Bristol Peptide Synthesis Facility). Excess of peptide was incubated for 90 min at 4°C with 100 μL Streptavidin Sepharose HP beads (GE Healthcare), pre-equilibrated in 0.025 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), 0.2 M NaCl, and 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol. Beads were equilibrated overnight at 4°C with purified wild-type or mutant Crb2–BRCT2 (0.1 mg × mL−1 in 0.025 M Tris-HCl at pH 7.0, 0.2 M NaCl, 0.2% BSA, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol), washed, resuspended in SDS loading buffer, run on SDS-PAGE gels, and visualized by Western blot, using an α-His6 Ab. To determine phospho-dependence of the interaction, the same peptide was treated overnight with λ-phosphatase and the experiment repeated. Coprecipitation studies of 53BP1_BRCT2 used a biotinylated phosphopeptide (Biotin-GSGYSGSKATQA-pS140-QEY; University of Bristol Peptide Synthesis Facility) corresponding to the C-terminal tail of human γ-H2AX.

Strains

The crb2 mutant strains were created using recombinase-mediated cassette exchange (Watson et al. 2008). Wild-type S. pombe (sp.011) was used to construct the crb2 base strain in which the ura4 gene flanked by LoxP and LoxM sites replaced the crb2 coding sequence (CDS) plus 300 bp immediately 5′ to the CDS. The crb2 CDS plus 300 bp upstream of the ATG were amplified and cloned into pAW6 so that it was flanked by LoxP and LoxM sites. Site-directed mutagenesis was carried out using the QuikChange system. Mutated sequences were then cloned into pAW7IN (LEU2+) and transformed into the base strain. ura+, leu+ transformants were selected in the presence of thiamine, grown in nonselective medium for 24 h, and plated onto medium containing 5-fluoroorotic acid. Colonies appearing after 2–3 d were used for further analysis. tdTomato-Crb2 (T-Crb2) was created by cloning a tdTomato tag (Shaner et al. 2004) upstream of the Crb2 coding sequence but separated from it with a (G)3(TGS)4 linker. tdTomato-tagged strains were checked for genotoxin sensitivity to ensure that the tag did not interfere with protein function (data not shown). chk1-HA was from N. Walworth (Walworth and Bernards 1996) and rad22-GFP was from J. Cooper (CRUK, London); rpa1-GFP was from M. Ferreira (Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência, Portugal).

Microscopy

For visualization of Rad22-GFP and Rpa1-GFP foci, cells were grown in rich medium (YEA) overnight at 30°C and irradiated with 20 or 40 Gy IR as indicated using a [137Cs] γ source with a dose rate of 8 Gy per minute. For T-Crb2 foci, cells were grown in minimal medium plus the necessary supplements overnight at 25°C and irradiated with 40 Gy IR. Rad22-GFP foci were observed in live cells while Rpa1 and Crb2 foci were observed in methanol-fixed cells, using an Applied Precision Deltavision Spectris microscope with deconvolution software.

For colocalization studies of Rad22-GFP and T-Crb2 foci, cells were grown in minimal medium plus the necessary supplements overnight at 25°C, irradiated with 40 Gy IR, and incubated for 10 min at 25°C before harvesting. Cell were fixed in methanol and observed immediately on a Deltavision Spectris microscope.

Analysis of checkpoint function and DNA damage sensitivities

The DNA integrity checkpoint was analyzed as described (al-Khodairy and Carr 1992). UV irradiation was carried out on freshly plated cells using a Stratagene Stratalinker. γ-Irradiation was carried out as described above. Sensitivities to HU and CPT were analyzed on YE agar at the doses stated.

Chk1 activation

Exponentially growing cultures containing HA-Chk1 were exposed to 0, 20, or 200 Gy IR and then incubated for 30 min at 30°C. Total protein was extracted using TCA (Caspari et al. 2002) and separated by SDS PAGE. Proteins were transferred to Immobilon P and Western blotted using anti-HA monoclonal antibody (Roche) followed by HRP-conjugated anti-mouse antibodies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jacky Metcalfe for peptide synthesis, Sally Glockling for help with microscopy, and Tony Carr for helpful discussions. We are grateful to the ESRF Grenoble and Diamond (Oxford) for access to synchrotron beam time. This work was supported by a Cancer Research UK Programme Grant (L.H.P.) and Project Grant (F.Z.W.).

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available at http://www.genesdev.org.

Article is online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.472808.

References

- Adams P.D., Gopal K., Grosse-Kunstleve R.W., Hung L.W., Ioerger T.R., McCoy A.J., Moriarty N.W., Pai R.K., Read R.J., Romo T.D., et al. Recent developments in the PHENIX software for automated crystallographic structure determination. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 2004;11:53–55. doi: 10.1107/s0909049503024130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn J., Urist M., Prives C. Questioning the role of checkpoint kinase 2 in the p53 DNA damage response. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:20480–20489. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213185200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- al-Khodairy F., Carr A.M. DNA repair mutants defining G2 checkpoint pathways in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. EMBO J. 1992;11:1343–1350. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05179.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakkenist C.J., Kastan M.B. DNA damage activates ATM through intermolecular autophosphorylation and dimer dissociation. Nature. 2003;421:499–506. doi: 10.1038/nature01368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartek J., Lukas J. Mammalian G1- and S-phase checkpoints in response to DNA damage. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2001;13:738–747. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00280-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartek J., Lukas J. Chk1 and Chk2 kinases in checkpoint control and cancer. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:421–429. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00110-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bork P., Hofmann K., Bucher P., Neuwald A.F., Altschul S.F., Koonin E.V. A superfamily of conserved domains in DNA damage responsive cell cycle checkpoint proteins. FASEB J. 1997;11:68–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botuyan M.V., Lee J., Ward I.M., Kim J.E., Thompson J.R., Chen J., Mer G. Structural basis for the methylation state-specific recognition of histone H4-K20 by 53BP1 and Crb2 in DNA repair. Cell. 2006;127:1361–1373. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunger A.T. Version 1.2 of the crystallography and NMR system. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:2728–2733. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callebaut I., Mornon J.P. From BRCA1 to RAP1: A widespread BRCT module closely associated with DNA repair. FEBS Lett. 1997;400:25–30. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01312-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspari T., Murray J.M., Carr A.M. Cdc2–cyclin B kinase activity links Crb2 and Rqh1-topoisomerase III. Genes & Dev. 2002;16:1195–1208. doi: 10.1101/gad.221402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 Programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Bio.l Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. [Google Scholar]

- Davey C.A., Sargent D.F., Luger K., Maeder A.W., Richmond T.J. Solvent mediated interactions in the structure of the nucleosome core particle at 1.9 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;319:1097–1113. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00386-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derbyshire D.J., Basu B.P., Serpell L.C., Joo W.S., Date T., Iwabuchi K., Doherty A.J. Crystal structure of human 53BP1 BRCT domains bound to p53 tumour suppressor. EMBO J. 2002;21:3863–3872. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downs J.A., Lowndes N.F., Jackson S.P. A role for Saccharomyces cerevisiae histone H2A in DNA repair. Nature. 2000;408:1001–1004. doi: 10.1038/35050000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du L.L., Nakamura T.M., Moser B.A., Russell P. Retention but not recruitment of Crb2 at double-strand breaks requires Rad1 and Rad3 complexes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:6150–6158. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.17.6150-6158.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du L.L., Moser B.A., Russell P. Homo-oligomerization is the essential function of the tandem BRCT domains in the checkpoint protein Crb2. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:38409–38414. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403326200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du L.L., Nakamura T.M., Russell P. Histone modification-dependent and -independent pathways for recruitment of checkpoint protein Crb2 to double-strand breaks. Genes & Dev. 2006;20:1583–1596. doi: 10.1101/gad.1422606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupre A., Boyer-Chatenet L., Gautier J. Two-step activation of ATM by DNA and the Mre11–Rad50–Nbs1 complex. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006;13:451–457. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emili A. MEC1-dependent phosphorylation of Rad9p in response to DNA damage. Mol. Cell. 1998;2:183–189. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80128-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P., Cowtan K. Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esashi F., Yanagida M. Cdc2 phosphorylation of Crb2 is required for reestablishing cell cycle progression after the damage checkpoint. Mol. Cell. 1999;4:167–174. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80364-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenech M., Carr A.M., Murray J., Watts F.Z., Lehmann A.R. Cloning and characterization of the rad4 gene of Schizosaccharomyces pombe; a gene showing short regions of sequence similarity to the human XRCC1 gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:6737–6741. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.24.6737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammet A., Magill C., Heierhorst J., Jackson S.P. Rad9 BRCT domain interaction with phosphorylated H2AX regulates the G1 checkpoint in budding yeast. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:851–857. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison J.C., Haber J.E. Surviving the breakup: The DNA damage checkpoint. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2006;40:209–235. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.40.051206.105231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinks J.A., Roe M., Ho J.C., Watts F.Z., Phelan J., McAllister M., Pearl L.H. Expression, purification and preliminary X-ray analysis of the BRCT domain from Rhp9/Crb2. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2003;59:1230–1233. doi: 10.1107/s0907444903007054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirao A., Kong Y.Y., Matsuoka S., Wakeham A., Ruland J., Yoshida H., Liu D., Elledge S.J., Mak T.W. DNA damage-induced activation of p53 by the checkpoint kinase Chk2. Science. 2000;287:1824–1827. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huyen Y., Zgheib O., Ditullio R.A., Gorgoulis V.G., Zacharatos P., Petty T.J., Sheston E.A., Mellert H.S., Stavridi E.S., Halazonetis T.D. Methylated lysine 79 of histone H3 targets 53BP1 to DNA double-strand breaks. Nature. 2004;432:406–411. doi: 10.1038/nature03114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javaheri A., Wysocki R., Jobin-Robitaille O., Altaf M., Cote J., Kron S.J. Yeast G1 DNA damage checkpoint regulation by H2A phosphorylation is independent of chromatin remodeling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2006;103:13771–13776. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511192103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jazayeri A., Falck J., Lukas C., Bartek J., Smith G.C., Lukas J., Jackson S.P. ATM- and cell cycle-dependent regulation of ATR in response to DNA double-strand breaks. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006;8:37–45. doi: 10.1038/ncb1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitayner M., Rozenberg H., Kessler N., Rabinovich D., Shaulov L., Haran T.E., Shakked Z. Structural basis of DNA recognition by p53 tetramers. Mol. Cell. 2006;22:741–753. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornbluth S., Smythe C., Newport J.W. In vitro cell cycle arrest induced by using artificial DNA templates. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1992;12:3216–3223. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.7.3216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.E., Moore J.K., Holmes A., Umezu K., Kolodner R.D., Haber J.E. Saccharomyces Ku70, mre11/rad50 and RPA proteins regulate adaptation to G2/M arrest after DNA damage. Cell. 1998;94:399–409. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81482-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.S., Collins K.M., Brown A.L., Lee C.H., Chung J.H. hCds1-mediated phosphorylation of BRCA1 regulates the DNA damage response. Nature. 2000;404:201–204. doi: 10.1038/35004614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M.S., Edwards R.A., Thede G.L., Glover J.N. Structure of the BRCT repeat domain of MDC1 and its specificity for the free COOH-terminal end of the γ-H2AX histone tail. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:32053–32056. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500273200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann A.R. Duplicated region of sequence similarity to the human XRCC1 DNA repair gene in the Schizosaccharomyces pombe rad4/cut5 gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:5274. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.22.5274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie A.G.W. MOSFLM users guide. MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology; Cambridge, UK: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Limbo O., Chahwan C., Yamada Y., de Bruin R.A., Wittenberg C., Russell P. Ctp1 is a cell-cycle-regulated protein that functions with Mre11 complex to control double-strand break repair by homologous recombination. Mol. Cell. 2007;28:134–146. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luger K., Mader A.W., Richmond R.K., Sargent D.F., Richmond T.J. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 A resolution. Nature. 1997;389:251–260. doi: 10.1038/38444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manke I.A., Lowery D.M., Nguyen A., Yaffe M.B. BRCT repeats as phosphopeptide-binding modules involved in protein targeting. Science. 2003;302:636–639. doi: 10.1126/science.1088877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy A.J. Solving structures of protein complexes by molecular replacement with Phaser. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2007;63:32–41. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906045975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo J., Toczyski D. A unified view of the DNA-damage checkpoint. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2002;14:237–245. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00312-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochida S., Esashi F., Aono N., Tamai K., O’Connell M.J., Yanagida M. Regulation of checkpoint kinases through dynamic interaction with Crb2. EMBO J. 2004;23:418–428. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov G.N., Vagin A.A., Dodson E.J. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers J.S., Cortez D. Rapid activation of ATR by ionizing radiation requires ATM and Mre11. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9346–9350. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513265200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T.M., Du L.L., Redon C., Russell P. Histone H2A phosphorylation controls Crb2 recruitment at DNA breaks, maintains checkpoint arrest, and influences DNA repair in fission yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:6215–6230. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.14.6215-6230.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T.M., Moser B.A., Du L.L., Russell P. Cooperative control of Crb2 by ATM family and Cdc2 kinases is essential for the DNA damage checkpoint in fission yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:10721–10730. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.24.10721-10730.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saka Y., Esashi F., Matsusaka T., Mochida S., Yanagida M. Damage and replication checkpoint control in fission yeast is ensured by interactions of Crb2, a protein with BRCT motif, with Cut5 and Chk1. Genes & Dev. 1997;11:3387–3400. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.24.3387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancar A., Lindsey-Boltz L.A., Unsal-Kacmaz K., Linn S. Molecular mechanisms of mammalian DNA repair and the DNA damage checkpoints. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2004;73:39–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders S.L., Portoso M., Mata J., Bahler J., Allshire R.C., Kouzarides T. Methylation of histone H4 lysine 20 controls recruitment of Crb2 to sites of DNA damage. Cell. 2004;119:603–614. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartori A.A., Lukas C., Coates J., Mistrik M., Fu S., Bartek J., Baer R., Lukas J., Jackson S.P. Human CtIP promotes DNA end resection. Nature. 2007;450:509–514. doi: 10.1038/nature06337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz L.B., Chehab N.H., Malikzay A., Halazonetis T.D. p53 binding protein 1 (53BP1) is an early participant in the cellular response to DNA double-strand breaks. J. Cell Biol. 2000;151:1381–1390. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.7.1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz M.F., Duong J.K., Sun Z., Morrow J.S., Pradhan D., Stern D.F. Rad9 phosphorylation sites couple Rad53 to the Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA damage checkpoint. Mol. Cell. 2002;9:1055–1065. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00532-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaner N.C., Campbell R.E., Steinbach P.A., Giepmans B.N., Palmer A.E., Tsien R.Y. Improved monomeric red, orange and yellow fluorescent proteins derived from Discosoma sp. red fluorescent protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004;22:1567–1572. doi: 10.1038/nbt1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G.M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. A. 2008;64:112–122. doi: 10.1107/S0108767307043930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soulier J., Lowndes N.F. The BRCT domain of the S. cerevisiae checkpoint protein Rad9 mediates a Rad9–Rad9 interaction after DNA damage. Curr. Biol. 1999;9:551–554. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80242-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens C., Smith L., La Thangue N.B. Chk2 activates E2F-1 in response to DNA damage. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003;5:401–409. doi: 10.1038/ncb974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart G.S., Wang B., Bignell C.R., Taylor A.M., Elledge S.J. MDC1 is a mediator of the mammalian DNA damage checkpoint. Nature. 2003;421:961–966. doi: 10.1038/nature01446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiff T., O’Driscoll M., Rief N., Iwabuchi K., Lobrich M., Jeggo P.A. ATM and DNA-PK function redundantly to phosphorylate H2AX after exposure to ionizing radiation. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2390–2396. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiff T., Walker S.A., Cerosaletti K., Goodarzi A.A., Petermann E., Concannon P., O’Driscoll M., Jeggo P.A. ATR-dependent phosphorylation and activation of ATM in response to UV treatment or replication fork stalling. EMBO J. 2006;25:5775–5782. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stucki M., Clapperton J.A., Mohammad D., Yaffe M.B., Smerdon S.J., Jackson S.P. MDC1 directly binds phosphorylated histone H2AX to regulate cellular responses to DNA double-strand breaks. Cell. 2005;123:1213–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su T.T. Cellular responses to DNA damage: One signal, multiple choices. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2006;40:187–208. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.40.110405.090428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z., Hsiao J., Fay D.S., Stern D.F. Rad53 FHA domain associated with phosphorylated Rad9 in the DNA damage checkpoint. Science. 1998;281:272–274. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5374.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toh G.W., O’Shaughnessy A.M., Jimeno S., Dobbie I.M., Grenon M., Maffini S., O’Rorke A., Lowndes N.F. Histone H2A phosphorylation and H3 methylation are required for a novel Rad9 DSB repair function following checkpoint activation. DNA Repair (Amst.) 2006;5:693–703. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varma A.K., Brown R.S., Birrane G., Ladias J.A. Structural basis for cell cycle checkpoint control by the BRCA1-CtIP complex. Biochemistry. 2005;44:10941–10946. doi: 10.1021/bi0509651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vialard J.E., Gilbert C.S., Green C.M., Lowndes N.F. The budding yeast Rad9 checkpoint protein is subjected to Mec1/Tel1-dependent hyperphosphorylation and interacts with Rad53 after DNA damage. EMBO J. 1998;17:5679–5688. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.19.5679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vonrhein C., Blanc E., Roversi P., Bricogne G. Automated structure solution with autoSHARP. Methods Mol. Biol. 2007;364:215–230. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-266-1:215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walworth N.C., Bernards R. rad-dependent response of the chk1-encoded protein kinase at the DNA damage checkpoint. Science. 1996;271:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5247.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Liu D., Wang Y., Qin J., Elledge S.J. Pds1 phosphorylation in response to DNA damage is essential for its DNA damage checkpoint function. Genes & Dev. 2001;15:1361–1372. doi: 10.1101/gad.893201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Matsuoka S., Ballif B.A., Zhang D., Smogorzewska A., Gygi S.P., Elledge S.J. Abraxas and RAP80 form a BRCA1 protein complex required for the DNA damage response. Science. 2007;316:1194–1198. doi: 10.1126/science.1139476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward I.M., Minn K., van Deursen J., Chen J. p53 Binding protein 53BP1 is required for DNA damage responses and tumor suppression in mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:2556–2563. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.7.2556-2563.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward I., Kim J.E., Minn K., Chini C.C., Mer G., Chen J. The tandem BRCT domain of 53BP1 is not required for its repair function. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:38472–38477. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607577200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson A.T., Garcia V., Bone N., Carr A.M., Armstrong J. Gene tagging and gene replacement using recombinase-mediated cassette exchange in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Gene. 2008;407:63–74. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinert T.A., Hartwell L.H. The RAD9 gene controls the cell cycle response to DNA damage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science. 1988;241:317–322. doi: 10.1126/science.3291120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willson J., Wilson S., Warr N., Watts F.Z. Isolation and characterization of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe rhp9 gene: A gene required for the DNA damage checkpoint but not the replication checkpoint. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:2138–2146. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.11.2138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie A., Hartlerode A., Stucki M., Odate S., Puget N., Kwok A., Nagaraju G., Yan C., Alt F.W., Chen J., et al. Distinct roles of chromatin-associated proteins MDC1 and 53BP1 in mammalian double-strand break repair. Mol. Cell. 2007;28:1045–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X., Chen J. DNA damage-induced cell cycle checkpoint control requires CtIP, a phosphorylation-dependent binding partner of BRCA1 C-terminal domains. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:9478–9486. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.21.9478-9486.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X., Chini C.C., He M., Mer G., Chen J. The BRCT domain is a phospho-protein binding domain. Science. 2003;302:639–642. doi: 10.1126/science.1088753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou L., Elledge S.J. Sensing DNA damage through ATRIP recognition of RPA–ssDNA complexes. Science. 2003;300:1542–1548. doi: 10.1126/science.1083430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]