Abstract

Hair morphogenesis takes place through reciprocal epithelial and mesenchymal signaling; however, the mechanisms controlling signal exchange are poorly understood. Laminins are extracellular proteins that play critical roles in adhesion and signaling. Here we demonstrate the mechanism of how laminin-511 controls hair morphogenesis. Dermal papilla (DP) from laminin-511 mutants showed developmental defects by E16.5, including a failure to maintain expression of the key morphogen noggin. This maintenance was critical as exogenous introduction of noggin or sonic hedgehog (Shh) produced downstream from noggin was sufficient to restore hair follicle development in lama5−/− (laminin-511-null) skin. Hair development required the β1 integrin binding but not the heparin binding domain of laminin-511. Previous studies demonstrated that Shh signaling requires primary cilia, microtubule-based signaling organelles. Laminin-511 mutant DP showed decreased length and structure of primary cilia in vitro and in vivo. Laminin-511, but not laminin-111, restored primary cilia formation in lama5−/− mesenchyme and triggered noggin expression in an Shh- and PDGF-dependent manner. Inhibition of laminin-511 receptor β1 integrin disrupted DP primary cilia formation as well as hair development. These studies show that epithelial-derived laminin-511 is a critical early signal that directs ciliary function and DP maintenance as a requirement for hair follicle downgrowth.

Keywords: Laminin, primary cilium, basement membrane, integrin, hair

Hair morphogenesis occurs through the reciprocal exchange of epithelial and mesenchymal signals (Hardy 1992; Oro and Scott 1998). Epithelia initially form small invaginations termed placodes, which grow progressively downward to ultimately form hair follicles. Wnt signaling is critical for initiation of hair follicle development (Andl et al. 2002; Stark et al. 2007) and early hair follicle downgrowth (Reddy et al. 2001). Mesenchymal factors required for epithelial downgrowth include fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) (Petiot et al. 2003) and the bone morphogenic protein (BMP) inhibiter noggin (Botchkarev et al. 1999). Noggin-induced BMP inhibition and Wnt-mediated cytoplasmic β-catenin accumulation together lead to expression and activation of members of the Lef1/TCF DNA-binding protein family (Jamora et al. 2003). Lef-1 expression/activation down-regulates e-cadherin and increases Sonic hedgehog (Shh) (St-Jacques et al. 1998). Thus, sustained expression of Shh relies on a close association of epithelial cells with the BMP inhibitory environment of the dermal papilla (DP) (Blanpain and Fuchs 2006). Similarly, vertebrate limb outgrowth also relies on a close association between Shh and BMP inhibition and is driven through a feedback loop involving Shh, FGF, and the BMP inhibitor gremlin (Khokha et al. 2003; Scherz et al. 2004).

The mesenchymal condensate later becomes partially surrounded by follicular epithelium to form a mature structure termed the DP (Hardy 1992). After maturation, DP cells retain the capacity to promote hair formation in combination with a variety of epithelial cells (Kamimura et al. 1997; Kishimoto et al. 2000). While Wnt signaling is required for maintenance of hair-inducing properties (Kishimoto et al. 2000; Shimizu and Morgan 2004), the factors that promote earlier DP development during embryogenesis remain poorly understood.

Laminins are a large group of extracellular α, β, and γ chain trimers that localize to the basement membrane zone (BMZ) at the boundaries between tissue compartments. Laminins are expressed starting at the morula stage of development, and the earliest mammalian laminins detected during embryogenesis are laminin-111 and laminin-511 (S. Li et al. 2003). During hair follicle elongation, the BMZ undergoes changes in its laminin composition. Laminin-332, normally a prominent component of the dermal–epidermal BMZ (Rousselle et al. 1991), and laminin-111 are both down-regulated (Nanba et al. 2000; Hayashi et al. 2002), leaving laminin-511 as the primary laminin of the early developing hair follicle. Absence of laminin-511 in transgenic mice led to a number of developmental abnormalities, including an arrest of hair development at the hair peg stage and deficient Shh expression in hair follicles. Purified laminin-511 restored hair development in laminin-511-null skin, which, among other data, clearly supported a specific role for laminin-511 in hair development (J. Li et al. 2003).

Laminin-511 is widely expressed in many epithelial tissues (Miner et al. 1995); however, Shh expression is limited. Thus, we hypothesized that laminin-511’s role in promoting Shh expression could involve other factors such as specialized mesenchymal cells. To investigate this, we tested the effects of laminin-511 on DP maturation and function in a series of in vitro and in vivo studies. As a result, we demonstrate here a requirement for laminin-511 in the production of noggin in the DP, which leads to epithelial LEF-1 expression and amplification of Shh signaling. We further show that laminin-511 promotes the expression of an array of proteins associated with DP maturation. We also demonstrate an association between laminin-511 expression, primary cilia formation, and PDGF-associated signaling in DP cells. Finally, we demonstrate that laminin-511’s primary receptor β1 integrin, like laminin-511, is required for both primary cilia formation in the DP as well as hair development. These results reveal laminin-511 as an important early epithelial message that promotes DP development and ciliary function during hair follicle morphogenesis.

Results

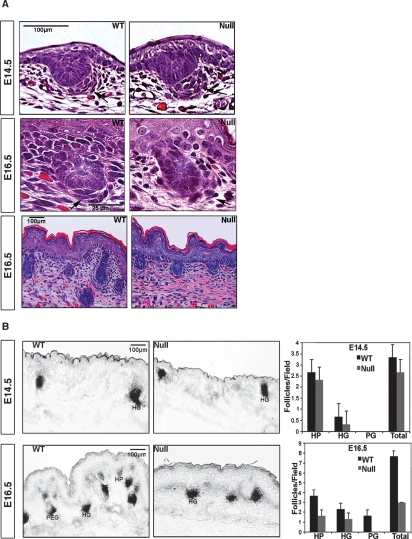

Effects of laminin-511 on dermal organization and epithelial follicular downgrowth

We examined hair follicles in wild-type and laminin-511-null (lama5−/−) mice at different embryonic stages. At both embryonic day 14.5 (E14.5) and E16.5, dermal condensates (as shown by arrows) were consistently more poorly associated with follicular epithelium in lama5−/− mice compared with wild-type controls (Fig. 1A). At E14.5, lama5−/− condensates were more spread out and distant from the follicular epithelium. At E16.5, lama5−/− dermal condensates were even more dispersed and less well organized than those seen in E14.5 control skin. By E16.5, hair follicle development in E16.5 lama5−/− skin appeared stunted, limited to hair placode and hair germ stages, and never progressing to the more advanced hair peg stage. Despite poor organization, lama5−/− dermal condensates demonstrated alkaline phosphatase activity (AP) comparable with wild type, and from this, we compared hair follicle number and elongation in lama5−/− and control skin as shown in Figure 1B. Hair follicle numbers in lama5−/− skin were not significantly abnormal at E14.5, but were <50% of E16.5 wild-type skin. By E16.5, a dramatic defect of follicle downgrowth became evident in lama5−/− skin, where no follicles were able to progress to the hair peg stage. Since lama5−/− animals could not survive beyond E16.5, we demonstrated previously that lama5−/− skin showed a complete regression of recognizable hair follicle appendages by 9 d after xenografting (J. Li et al. 2003). The association of a defective dermal condensate organization with an arrest and ultimately a regression of hair follicle development in lama5−/− skin suggested a possible role for laminin-511 in DP maturation. We explored this further by examining the role of laminin-511 in signaling associated with hair follicle development.

Figure 1.

Arrested hair morphogenesis in lama5−/− mice. (A) Typical morphology of hair placodes and associated developing dermal condensates/papillas (arrows) in E14.5 and E16.5 wild-type (WT) and lama5−/− (null) skin. (B) NBI/BCIP detects alkaline phosphatase (AP) activity in dermal condensates of both null and wild type. Quantification of hair follicles in E14.5, E16.5 wild-type and lama5−/− (null) skin. (HP) Hair placodes; (HG) hair germs; (PEG) hair pegs.

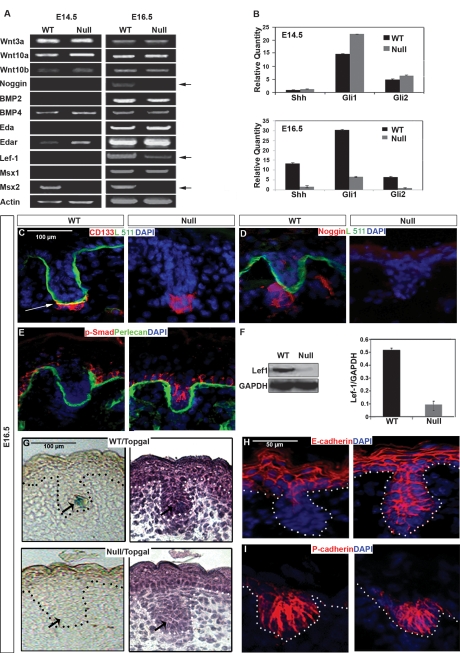

Laminin-511 facilitates epithelial–mesenchymal signaling during hair morphogenesis

In an effort to understand how the absence of laminin-511 led to an alteration of DP morphology and an early arrest of hair follicle downgrowth, we examined expression of early hair signaling molecules including Wnts, Eda/Edar, Noggin/BMPs, and Shh in E14.5 and E16.5 lama5−/− and wild-type skin using semiquantitative and real-time RT–PCR (Fig. 2A,B). While no alterations of Wnt expression were noted in lama5−/− skin, downstream Wnt transcription factor Lef-1 showed decreased expression at E16.5 (Fig. 2A). Also at E16.5, expression of noggin, Shh, and Gli1/2 was significantly decreased (Fig. 2A,B). We also noted a reduction of Msx2 expression in lama5−/− skin starting at E14.5. Laminin α5 chain expression was equivalent at both E14.5 and E16.5 time points, as shown previously (J. Li et al. 2003). Noggin-induced BMP inhibition works in synergy with Wnt signaling to promote Lef-1 expression and activation, respectively, during early follicular downgrowth, leading to Shh expression and activation of the Shh signaling pathway (St-Jacques et al. 1998; Botchkarev et al. 2001). Thus, defects of Lef-1, Shh, and Gli1/2 expression would be expected to arise as a result of a lack of noggin expression in lama5−/− skin.

Figure 2.

lama5−/− skin shows defective hair mesenchymal–epithelial signaling. (A) Semiquantitative RT–PCR analysis of critical signaling molecules involved in early hair morphogenesis, from mRNA isolated from E14.5 and E16.5 wild-type (WT) or lama5−/− dorsal skin. (B) The same mRNA was reviewed for the expression level of Shh, Gli1, and Gli2 by quantitative RT–PCR. (C–E) Dual-label IF microscopy of E16.5 wild-type or lama5−/− (null) dorsal skin, using indicated antibodies to CD133, laminin α5 pAb (Lm10), noggin, phospho-SMAD, and perlecan. The color of the text indicates the secondary antibody conjugates used: (green) fluorescein; (red) Texas Red. All sections were costained with nuclear marker (DAPI, blue). Arrow in C shows colocalization of CD133 staining cells with laminin-511. (F) Western blot-evaluated protein levels of Lef1 in E16.5 dorsal skin of both genotypes. GAPDH was a control for equal protein loadings. (G, left) Topgal activity detected by X-gal staining in E16.5 Topgal/lama5−/− and Topgal/wild-type skin. (Right) Hematoxylin illustrated the hair germ morphology of same skin sections. Dotted lines indicate skin basement membrane (BMZ). (H,I) IF microscopy of E16.5 dorsal wild-type skin on the left, or lama5−/− skin on the right, using antibodies to E-cadherin and P-cadherin, using DAPI nuclear stain.

These results suggested that laminin-511’s function in promoting early hair follicle downgrowth could result from its role in influencing DP development, in particular, noggin expression. Consistent with this, as seen by immunofluorescence (IF) microscopy, we noted a close association of laminin-511 with the DP using a DP-specific marker, CD133 (Fig. 2C; Ito et al. 2007) and a lack of detectable noggin in E16.5 lama5−/− skin (Fig. 2D). Noggin has been previously shown to inhibit BMP-induced SMAD phosphorylation in the follicular epithelium (Botchkarev 2003). We found that SMAD1/5/8 phosphorylation was incompletely repressed in lama5−/− follicular epithelium (Fig. 2E), further confirming the signaling effects following loss of dermal noggin in lama5−/− skin.

In agreement with our mRNA studies above, we noted deficient Lef-1 expression in lama5−/− skin as shown by Western blot (Fig. 2F). To study the relationship of laminin-511 with Lef-1 activation, we crossed lama5−/− mice with mice harboring TOPGAL, a β-galactosidase gene under the control of a Lef/TCF- and β-catenin-inducible promoter (DasGupta and Fuchs 1999). Consistent with the deficient Lef-1 expression seen in lama5−/− skin (Fig. 2A,F), lama5−/−/TOPGAL skin showed a loss of TOPGAL activation (Fig. 2G).

Tissue morphogenesis depends on the activity of adherens junctions proteins during development (Halbleib and Nelson 2006). Selective down-regulation of E-cadherin but not P-cadherin is a crucial step in hair follicle downgrowth (Jamora et al. 2005). Consistent with our observed defect of Lef-1 activity, we found a conspicuous lack of E-cadherin down-regulation in follicular epithelium in lama5−/− skin at E16.5, despite unaffected P-cadherin expression (Fig. 2G,H). From these results, we hypothesized that laminin-511 promoted expression of noggin in the DP, which led to Lef-1 expression, Shh expression, activation of the Shh pathway, and down-regulation of E-cadherin in hair epithelium. We tested this hypothesis using a series of in vivo experiments described below.

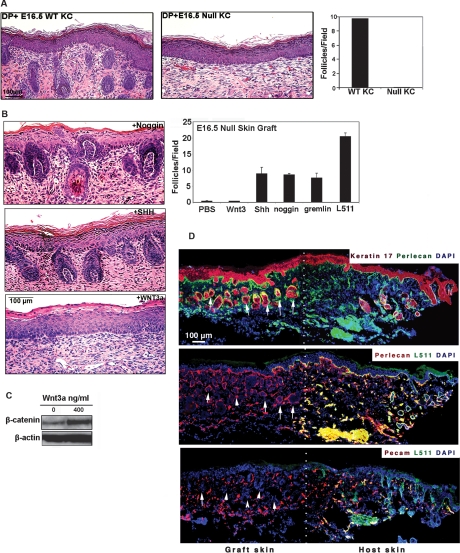

Epithelial laminin-511 drives follicular downgrowth by amplifying noggin–Shh signaling

Laminin-511 is both an epithelial and endothelial derived protein (Miner et al. 1995). In order to determine the cellular origin of the laminin-511 active in hair morphogenesis, we combined freshly isolated wild-type neonatal DP cells with either wild-type or lama5−/− E16.5 keratinocytes and analyzed them 2 wk after grafting to nude mice via hair reconstitution assay (Kishimoto et al. 2000). The lama5−/− keratinocytes, despite the presence of wild-type mesenchyme and endothelium, showed an inability to support hair follicle development (Fig. 3A). These results suggest that any contribution of laminin-511 by dermal endothelium was insufficient and that laminin-511 of epithelial origin was required to drive hair follicle development.

Figure 3.

Exogenous noggin or SHH, but not by Wnt3a, can rescue hair development in the absence of epithelial laminin-511. (A) Hematoxylin-eosin staining of skin harvested 2 wk following hair reconstitution assay using either wild-type (WT) or lama5−/− (null) E16.5 keratinocytes combined with wild-type dermal cells. (Right) Quantification of hair follicles in both conditions. (B) Full thickness E16.5 lama5−/− dorsal skin was incubated overnight with purified Wnt3a protein, Shh adenovirus (SHH), or noggin and analyzed by hematoxylin-eosin staining 9 d after grafting to nude mice. (Top right) Quantification of hair follicles under six different conditions for hair restoration experiments, including PBS control. (C) Level of β-catenin in E16.5 lama5−/− skin after overnight treatment with indicated quantity of purified Wnt3a (in ng/mL) demonstrating the activity of recombinant Wnt3a. (D) Immunofluorescence microscopy of adjacent frozen sections confirming hair follicle formation in absence of laminin-511 in grafted skin treated with noggin. Laminin-511 negative hair follicles (arrows) were identified as clusters of cells (nuclear antibody, DAPI) showing positive keratin 17 and perlecan expression, and negative Pecam expression, distinguishing them from blood vessels. The expression of laminin-511 was visualized by laminin α5 pAb (L511); white dots indicate the border between graft and host skin.

Our studies in Figure 2 raised the possibility that laminin-511 promoted hair follicle development by facilitating expression of important DP proteins such as noggin, which in turn promoted Shh expression. We tested this hypothesis with xenografting experiments, which we described previously (J. Li et al. 2003). Briefly, we immersed full-thickness E16.5 lama5−/− dorsal back skin overnight in a solution containing purified Wnt3a, noggin, or gremlin proteins or Shh-expressing adenovirus, then analyzed the treated skin 9 d after grafting to nude mice. Wnt3a showed no ability to restore hair follicle downgrowth in lama5−/− skin (Fig. 3B) even at concentrations shown to promote β-catenin accumulation (Fig. 3C). In contrast, Shh adenoviral supernatant (Sato et al. 1999) and recombinant noggin each showed a striking ability to prevent follicle regression and promote downgrowth, although not as efficiently as purified laminin-511. Interestingly we also noted that ectopic introduction of purified gremlin, a BMP inhibitor involved in limb development, was also able to prevent follicle regression and promote downgrowth in lama5−/− skin (Supplemental Fig. 1). IF microscopy analysis at the edge of noggin-treated lama5−/− skin grafts 9 d after transplantation verified the formation of hair follicles (Fig. 3D, arrows) in the absence of laminin-511 (Fig. 3D). Panels to the left of the dotted line in Figure 3D show noggin-induced hair follicle formation (arrows) occurring in the absence of laminin-511. Laminin-511 negative hair follicles were identified by keratin 17 expression, DAPI nuclear stain, a perlecan-containing basement membrane, and a lack of PECAM expression (distinguishing them from blood vessels). This suggests that laminin-511 was not an adhesive requirement for epithelial downgrowth, but instead, laminin-511 promoted hair growth through morphogenic signaling resulting in Shh and noggin expression.

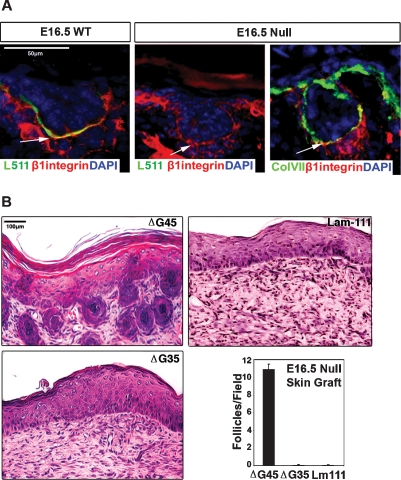

Interaction of laminin-511 and β1 integrin during hair morphogenesis

Laminins exert their effects on cells through interactions with specific cell surface receptors, most notably those of the integrin family (Hynes 2002), and the major integrins known to bind laminin-511 include α3β1, α6β1, and α6β4 (van der Neut et al. 1999; Kikkawa et al. 2000). While no hair defects have been reported with absence of α6β4 integrin in mice (Fassler et al. 1996; Georges-Labouesse et al. 1996) or humans (Vidal et al. 1995; Marinkovich et al. 2003), marked hair defects were noted in α3 (Conti et al. 2003) and β1 (Brakebusch et al. 2000; Raghavan et al. 2000) integrin-null mice or after antibody blockage of β1 integrin in human skin (S. Li et al. 2003). These observations led us to further examine β1 integrin–laminin-511 associations in early hair morphogenesis. β1 integrin colocalized with laminin-511 at the interface between the dermal condensate and the follicular epithelium in developing E16.5 hair follicles (Fig. 4A). Even in the absence of laminin-511, β1 integrin colocalized at the epithelial–mesenchymal interface E16.5 lama5−/− skin with other basement membrane components including collagen VII. These studies suggest that basement membrane localization of β1 integrin by itself is not sufficient to drive hair morphogenesis. Rather, it is the interaction of β1 integrin with laminin-511 in the basement membrane that is required.

Figure 4.

Role of laminin-511 and β1 integrin in hair follicle downgrowth and DP maturation. (A) Wild-type (WT) or lama5−/− (null) E16.5 skin was examined using antibodies to laminin-511 (L511) and activated β1 integrin at the time points indicated. Note colocalization of laminin-511 and β1 integrin at interface between follicular epithelium and DP (arrows). (DP) Dermal papilla; (DC) dermal condensate; (IRS) inner root sheath; (ORS) outer root sheath. (B) Hematoxylin-eosin sections of lama5−/− skin grafts 9 d after treatment with purified laminin proteins. The ΔG45 deletion mutant of laminin-511 contains β1 integrin binding sites but lacks the major heparin binding domain. The ΔG45 deletion mutant of laminin-511 lacks the β1 integrin-binding site and the major heparin binding domain. Lam-111 represents laminin-111. (Bottom right panel) Quantification of hair follicles in each of the conditions in B.

The laminin-511 α5 chain contains five C-terminal EGF-like repeats numbered G1–5. It is known that the integrin binding region lies in the G1–3 domain (Ido et al. 2004; Nishiuchi et al. 2006; Kikkawa et al. 2007), while another region located in the G4–5 domain interacts with heparin sulfate proteoglycans (Yu and Talts 2003) such as perlecan, dystroglycan, or syndecans. To study the role of integrin binding with laminin-511’s role in hair development, two purified recombinant laminin-511 molecules were tested, one with a deletion of the G4–5 domain of the α5 chain, which ablates the heparin binding, termed ΔG4–5, and another termed ΔG3–5, with a deletion of the G3–5 domain of the α5 chain, which removes both integrin and heparin binding. Each of these molecules has been shown to adopt a typical laminin trimeric configuration as previously characterized (Fig. 4B; Ido et al. 2006). Recombinant laminins were incubated in lama5−/− skin overnight and then analyzed for their ability to promote hair follicle formation in treated skin 9 d after grafting to nude mice. While significant hair follicle downgrowth was noted with the use of ΔG4–5 laminin-511, only follicle regression was seen with ΔG3–5 laminin-511 (Fig. 4). These results indicated that while the heparin-binding domain of laminin-511 G domain was not required for hair follicle development, the integrin-binding domain appears to play an important role in this process. We next focused on further exploring the mechanism of laminin-511 interaction with the dermal signaling niche.

Defective hair follicle dermal niche in lama5−/− mice

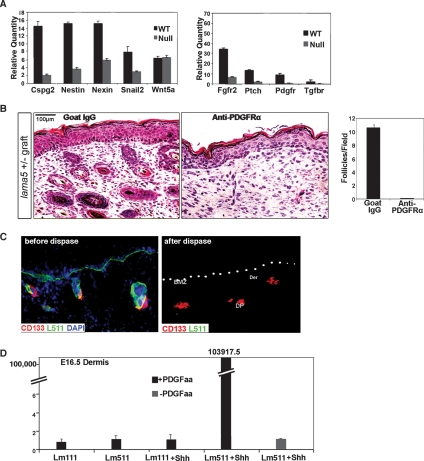

To determine what effects laminin-511 might have on DP development, we compared the expression of several known DP markers including Snail2 (Slug), Nestin, Wnt5a, Nexin 1, and Cspg2 (versican) (Kishimoto et al. 1999; Sonoda et al. 1999; Jensen et al. 2000; Fernandes et al. 2004) in E16.5 wild-type and null skin. Of these representative genes of the developing DP, all but Wnt5a showed significantly reduced mRNA expression in lama5−/− mice (Fig. 5A, left). To probe the signaling pathways involved in the interaction between laminin-511 and the hair dermal signaling niche, we studied growth factor receptors, Fgfr2, PDGFrα, and Tgfbr1, which localize in the dermal compartment and may play roles in hair development (Mandler and Neubuser 2004; Schneider et al. 2005; Grose et al. 2007). Surprisingly, the mRNA expression levels decreased in all of the aforementioned receptors in lama5−/− mice (Fig. 5A, right). We went on to study the relationship between PDGFrα signaling and laminin-511 in further detail.

Figure 5.

Cooperation of laminin-511, Shh, and PDGFrα in mesenchymal development. (A, right) Real-time RT–PCR-evaluated mRNA levels of DP markers Cspg2 (versican), nestin, nexin, snail2, and Wnt5a in E16.5 wild-type (WT) and lama5−/− (null) skin. (Left) Real-time RT–PCR evaluated the mRNA level of major developing DP cell surface receptors, Fgfr2, Pdgfrα, and Tgfrb1. (B) Functional blocking anti-PDGFrα antibody-treated lama5+/− skin. E16.5 lama5+/− skin was incubated overnight in anti-PDGFrα antibody or control goat IgG and analyzed 9 d following grafting to nude mice. Quantification of hair follicle formation is shown in right panel. (C) IF microscopy of E16.5 wild-type skin before (left panel) or after dispase digestion (middle and right panels), using CD133, type VII collagen (ColVII), and laminin-511 (Lm10) antibodies. Note loss of laminin-511 but preservation of CD133-expressing DP cells following dispase digestion. (DP) Developing DP; (BMZ) basement membrane zone marked by white dots; (Epi) epidermis; (Der) dermis. (D) Quantitative-PCR-evaluated induction of noggin mRNA expression in dispase-treated E16.5 mesenchyme under five conditions: laminin-111 + PDGF-AA, laminin-511 + PDGF-AA, laminin-111 + Shh + PDGF-AA, laminin-511 + Shh + PDGF-AA, and laminin-511 + PDGF-AA.

Laminin-511 induces noggin expression in DP cells through PDGF signaling

It is known that PDGF signaling plays a key role in DP maturation and hair development (Karlsson et al. 1999). To study whether laminin-511 promoted DP development through PDGR signaling, we incubated E16.5 lama5+/− skin overnight with PDGFrα blocking antibody. Nine days after grafting, PDGFrα antibody-treated skin showed a complete lack of hair development compared with goat IgG control (Fig. 5B). From these studies, we hypothesized that PDGFrα could function as a co-receptor involved in laminin-511-mediated signaling.

However, what are the signals sent by laminin-511 through PDGFrα during DP development? Do they relate to the induction of noggin in the DP by laminin-511? We used a mesenchymal in situ organ model to address these questions. Briefly, we digested E16.5 wild-type skin with the enzyme dispase, which mechanically removed laminin-511 from the dermis along with overlying epithelium (Fig. 5C). IF with laminin-511 antibody demonstrated that while laminin-511 was absent, DP were preserved as indicated with CD133 antibody (Fig. 5C). Laminin-511-depleted E16.5 mesenchyme was then tested for induction of noggin mRNA expression by treatment with laminin-511 and SHH overnight in serum-free medium, followed by induction with PDGF-AA for 5 h (Fig. 5D). A striking induction of noggin mRNA expression was noted upon addition of PDGF in laminin-511, Shh-treated mesenchyme. In the absence of Shh or PDGF, or if laminin-111 was substituted for laminin-511, the induction failed to occur (Fig. 5D). Interestingly, this showed a dependence on developmental timing as induction in E16.5 mesenchyme was far more pronounced than in E18.5 mesenchyme (Supplemental Fig. 2).

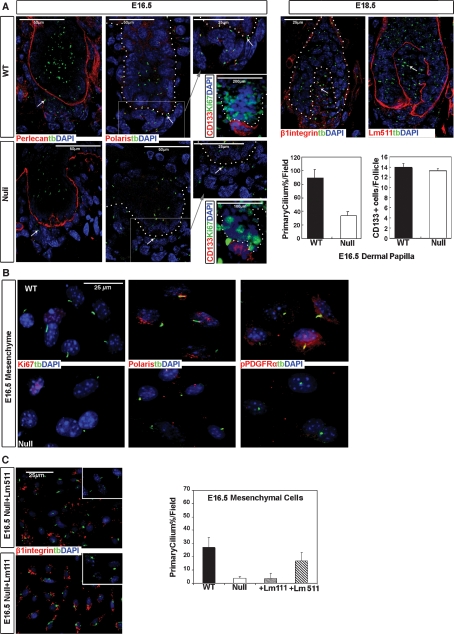

Laminin-511 promotes primary cilium formation in the DP

The primary cilium is a specialized organelle used in transduction of extracellular signals such as Shh. In fibroblasts, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) appears to act directly though PDGFRα located in the primary cilium (Schneider et al. 2005). Thus, our studies linking laminin-511 with PDGF signaling and SHH expression/signaling in DP cells led us to examine whether laminin-511’s function in hair morphogenesis might involve the DP primary cilium.

Toward this end, we examined primary cilium formation in wild-type and lama5−/− skin at E16.5 using confocal microscopy as shown in Figure 6A. The DP, the collection of cells underlying the lower aspect of the follicular epithelial basement membrane, shown in the left panel using perlecan antibody, showed several elongated primary cilia staining positive for acetylated α-tubulin in the wild-type condition. However, primary cilia in the DP were significantly diminished in the absence of laminin-511 in lama5−/− skin. Costaining of structural primary cilia proteins, acetylated α-tubulin and polaris, was readily seen in the DP of wild-type hair follicles, but not in lama5−/− skin. Despite the primary cilia changes, total numbers of CD133 positive cells per DP were not significantly altered in the presence or absence of laminin-511, and no Ki67 staining was seen in CD133-positive cells in either condition, suggesting a lack of proliferation. We were unable to reproducibly demonstrate primary cilia formation in E14.5 mutant or wild-type dermal condensates. This may be a result of the extreme fragility of the tissues at this stage of development or that cilia formation may be developmentally regulated.

Figure 6.

Laminin-511 promotes primary cilia formation in the DP of E16.5 skin and in dermal mesenchymal cells in vitro. (A) Expression of primary cilium structural proteins (acetylated α-tubulin and polaris), basement membrane proteins, perlecan and laminin-511 (Lm511), DP marker CD133, and proliferation marker Ki67 as analyzed by immunofluorescent microscopy at E16.5 and E18.5 time points. The names and corresponding colors of antibodies in combination with blue nuclear stain (DAPI) are indicated on the panels. At the right, the total number of primary cilium in both wild-type (WT) and lama5−/− (null), and the total number of CD133-positive cells per wild type and lama5−/− DP are quantified. (B) Fresh isolated E16.5 lama5−/− (null) and wild-type (WT) primary mouse mesenchymal cells after 12 h of culture were stained with antibodies (names and corresponding colors indicated on the panels) including acytylated tubulin (tb), Ki67, polaris and PDGFRα, and phospho-PDGFRαY754 and nuclear stain (DAPI, blue) and analyzed by IF microscopy. (C) Fresh isolated E16.5 null and wild-type primary mesenchymal cells were cultured with either laminin-511 or laminin-111 for 12 h, then stained with acetylated tubulin (tb) and β1 integrin antibodies. Insets show higher magnification of primary cilia structures. The table on the right shows quantification of primary cilia formation under the different indicated conditions.

We next examined freshly isolated primary mesenchymal cells from E16.5 wild-type and lama5−/− skin. After culture for 12 h, lama5−/− mesenchymal cells displayed significantly decreased numbers of primary cilia compared with wild-type cells as demonstrated by staining with primary cilium structure protein, acetylated α-tubulin and polaris, and anti-phorpho-PDGFRaY754 (Fig. 6B,C; Schneider et al. 2005). Ki67 staining was equivalent in lama5−/− and wild-type cells. To further examine the relationship between laminin-511 and primary cilia, we cultured fresh isolated lama5−/− mesenchymal cells with either purified laminin-511 or laminin-111 for 12 h. IF staining with acetylated α-tubulin and polaris antibodies showed that exogenous laminin-511 protein could restore >30% primary cilia formation in E16.5 lama5−/− cells compared with laminin-111, <5% (Fig. 6C). Differences in primary cilium formation were not associated with differences in focal adhesion formation between laminin-511 and laminin-111 conditions as shown by costaining with α-tubulin and β1 integrin antibodies (Fig. 6C). These studies in total suggest that laminin-511 is an important factor in promoting primary cilia formation in the developing DP.

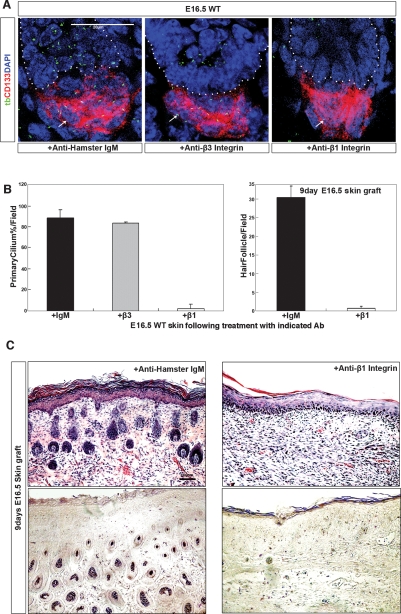

Finally, we examined the role of β1 integrin, the primary receptor for laminin-511, in DP function and primary cilia formation. Toward this end, we compared the effects of β1 or β3 integrin blocking antibody on primary cilia formation in the DP of E16.5 skin (Fig. 7A). Following overnight β1 (but not β3) integrin antibody incubation, we found a dramatic decrease of primary cilia, identified by acetylated tubulin staining, throughout the DP (shown through CD133 expression). This was quantified as shown in Figure 7B (left panel). We next tested the ability of antibody-treated E16.5 skin to support hair follicle development. As shown in Figure 7, B (right panel) and C, disruption of primary cilia formation by a single overnight incubation with β1 integrin blocking antibody led to a profound disruption of hair formation in grafted skin shown 9 d after grafting.

Figure 7.

Blockade of a major laminin-511 receptor, β1 integrin, inhibits primary cilia formation in the DP leading to an arrest of hair follicle development. (A) Freshly isolated E16.5 wild-type skin, following overnight incubation with either β1 or β3 integrin blocking antibodies or control antibody as indicated (2C9.G2; BD Biosciences) at 4°C, was analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy using antibodies to the DP marker CD133, the primary cilia marker α-acetylated tubulin (tb), and nuclear stain (DAPI). (B, left) Quantification of primary cilia formation as seen by α-acetylated tubulin staining in CD133-positive DP; each graph is the average of multiple high-power fields. (Right) Quantification of hair follicles in the skin of 9-d grafts following overnight treatment with control of β1 integrin antibodies. Each graph represents the average of multiple low-power fields. Error bars represent the standard deviation. (C, top panel) Hematoxylin and eosin staining shows hair formation in 9-d skin grafts of E16.5 wild-type skin, after overnight treatment with either β1 integrin blocking or control hamster IgM. (Bottom panel) NBT/BCIP staining shows AP activity in 9-d skin grafts. Conditions are as indicated in images.

Discussion

Early studies of hair follicle development using epithelial–mesenchymal tissue chimeras suggested that early epithelial messages pass extracellularly from the developing placode to organize the mesenchyme into a DP (Dhouailly 1973; Hardy 1992). This, in turn, leads to a second proposed dermal message that triggers follicular epithelial downgrowth. While many of the dermal signals, including the early appearance of FGFs (Petiot et al. 2003) and the later induction of expression of the BMP inhibitory factor noggin (Botchkarev et al. 1999), have been identified, the identity of early epithelial messages is incomplete. This study identifies a molecule, laminin-511, that fits the criteria of one such early epithelial signal.

Consistent with these criteria, laminin-511 is an extracellular, epithelial-derived molecule that, as we showed through hair reconstitution studies, must be secreted from the associated follicular epithelium to effectively promote hair morphogenesis. While a diversity of epithelial tissues, including cornea and amnion, have been shown to support hair morphogenesis in combination with embryonic dermis (Ferraris et al. 2000; Fliniaux et al. 2004; Pearton et al. 2005), our present studies suggest that one requirement limiting the diversity of epithelial tissues capable of participating in hair morphogenesis would be the capacity to express laminin-511. Our studies suggest that laminin-521, like laminin-511, could also facilitate hair follicle development. However, as laminin α2-deficient mice have no hair defects (Noakes et al. 1995) and we previously showed a down-regulation of the laminin 2 chain during mouse hair germ elongation (S. Li et al. 2003), it is not likely that laminin-521 plays a major role in hair follicle development in the skin.

The first epithelial signal in hair morphogenesis was proposed to promote cell adhesion (Hardy 1992) and, consistent with this, mesenchymal cells in the early developing DP closely associated with laminin-511 to promote a tighter, more organized cellular DP organization. However, laminin-511’s role in hair morphogenesis extends beyond facilitating cell adhesion. Our studies indicate that laminin-511 plays a critical role in supporting the developmental maturation of the DP. This is evidenced by the requirement of laminin-511 for the expression of several markers of DP development, including Cspg2 (versican), nestin, nexin, Snail2 (Slug), fgfr2, ptch, PDGFrα, and noggin, although continued expression of other DP-associated molecules such as CD133 and Wnt5a suggest that laminin-511’s effects on DP gene expression are selective. Also, it appears that the mesenchyme’s response to laminin-511 may be developmentally timed. For example, noggin expression by mesenchyme in response to laminin-511 was much greater at E16.5 as opposed to E18.5 time points.

The observation that exogenous noggin or Shh (neither of which are adhesion molecules) can reinitiate follicle downgrowth in the absence of laminin-511 protein suggests that laminin-511 is not required to support epithelial attachment and migration during early hair follicle downgrowth. Instead, it is laminin-511-driven noggin expression in the dermis that provides the required BMP inhibition to the follicular epithelium to enable early follicular downgrowth. The finding of normal levels of Wnt3a in lama5−/− skin and an inability of Wnt3a to rescue hair formation in lama5−/− skin suggests that despite its critical role in promoting β-catenin cytoplasmic accumulation and Lef-1 activation, the Wnt3a pathway is highly dependent on dermal input for the progression of hair morphogenesis during the early follicular downgrowth phase. As suggested previously (Jamora et al. 2003), regulation of Lef-1 activation may be driven by Wnt3a expression and β-catenin accumulation, which our data suggest may be independent of laminin-511. On the other hand, regulation of Lef-1 expression requires the input of noggin, which in turn appears to be controlled by laminin-511. Thus, laminin-511’s main contribution to follicular epithelial downgrowth is not support of adhesion or migration, but instead, by promoting noggin expression, it indirectly supports follicular epithelial signaling, providing needed input into the Wnt pathway.

Through deletion studies, we showed here that the heparin-binding site on the laminin-511 G domain is not required for hair development but that the integrin-binding site located in the G1–3 region is essential for this process. Laminin-511 is known to be a major ligand for α3β1 integrin (Kikkawa et al. 1998), and previous studies of the deletion of α3 integrin (Conti et al. 2003) have shown severe defects of hair morphogenesis, including altered hair follicle downgrowth. β1 integrin has been previously linked to Shh expression in both neural and intestinal tissues (Blaess et al. 2004; Jones et al. 2006). While prior studies examining the role of β1 integrin in hair have focused only on follicular epithelium, not the dermis (Brakebusch et al. 2000; Raghavan et al. 2000), our present studies suggest that integrins located on dermal cells may play an important role in laminin-511’s promotion of hair morphogenesis. Our previous studies showed that continuous blockage of β1 integrin in both dermis as well as follicular epithelium disrupts hair morphogenesis in vivo (Li et al. 2003). Our present studies show that even an overnight incubation of E16.5 skin with β1 integrin inhibitory antibody will disrupt any subsequent hair development. β1 subunit containing integrin receptors for laminins include α2β1, α3β1, and α6β1. While no hair abnormalities have been reported in α2 or α6 integrin-null mice (Georges-Labouesse et al. 1996; Holtkotter et al. 2002) or α6 integrin-null humans (Ruzzi et al. 1997), severe hair follicle abnormalities have been noted in α3 integrin-deficient mice including hair follicle elongation defects (Conti et al. 2003). Thus, of all the transgenic deletion models of α integrin subunits known to associate with β1 integrin, only the deletion of α3 integrin produces a defect of hair follicle elongation similar to that of lama5−/− and β1 integrin conditional null mice. These results suggest that α3β1 is the likely integrin mediating laminin-511’s effects on hair follicle development.

Laminin-511 supported primary cilia formation both in vivo in developing DP, and in cells isolated from embryonic mesenchyme in vitro. As inhibition of laminin-511’s receptor β1 integrin completely disrupted primary cilia formation in the DP, it is likely that laminin-511 exerted its effects on both primary cilia formation as well as hair development through β1 integrin. While primary cilia are known to be dependent on the cell cycle, we found that the presence or absence of laminin-511 had no effect on cell proliferation in the DP at E16.5. Primary cilia serve a critical function in mediating PDGF signaling in mesenchymal cells. Thus, primary cilia seen in the presence of laminin-511 likely explains how laminin-511 can induce PDGF-dependent noggin expression in DP cells. As primary cilia are known mediators of Shh signaling, the requirement for Shh in laminin-511’s induction of noggin expression is consistent with laminin-511’s function in promoting primary cilia formation and function. Laminin-511’s dual role in promoting Shh expression in the follicular epithelium through noggin induction, and augmenting the response to Shh in the DP through primary cilia formation, helps to explain the critical reliance of hair follicle downgrowth on laminin-511.

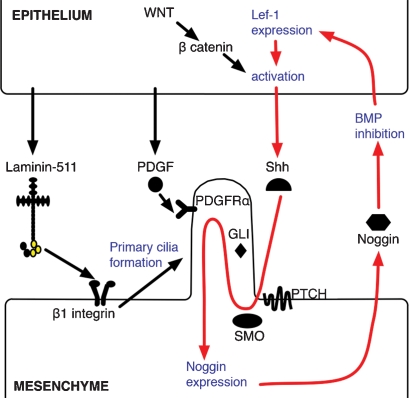

These findings suggest a feedback amplification loop between noggin and Shh that laminin-511 and primary cilium may help to maintain (shown schematically in Fig. 8). According to this model, epithelial-derived laminin-511 interacts with mesenchymal β1 integrin via the G1–3 (integrin-binding) domains of laminin-511’s α5 chain (shown in yellow). β1 integrin–laminin-511 binding promotes mesenchymal primary cilia formation, which in turn amplifies the mesenchymal response to epithelial-derived Shh, through activation of downstream Shh effectors including patched, smoothened, and Gli. PDGFRα in mesenchymal primary cilia is activated by epithelial PDGF, and this, combined with Shh signaling, leads to activation of noggin expression in mesenchymal cells. Noggin secreted by mesenchymal cells serves to inhibit BMP signaling in epithelial cells, leading to expression of LEF1. Activation of LEF1 by WNT-induced β-catenin accumulation (Jamora et al. 2003) leads to increased expression of Shh, which serves to further amplify the signaling loop. In this model, laminin-511 both amplifies the Shh signal in the mesenchyme by promoting primary cilia formation and also increases Shh expression in the epithelium by noggin-induced BMP inhibition. In this way, laminin-511 plays a key role in facilitating communication between epithelial and mesenchymal compartments during skin morphogenesis. Whether laminin-511 has similar effects in other organs such as the kidney (Shannon et al. 2006) or other known Shh-dependent developmental processes, such as limb or CNS morphogenesis, remains to be determined.

Figure 8.

Schematic of laminin-511’s role in hair development. Laminin-511 is secreted by the follicular epithelium into basement membrane separating follicular epithelium and DP, where it interacts with β1 integrin receptors on the DP cell surface. This leads to primary cilia development, which in turn amplifies Shh signaling, through Shh effector proteins including patched (PTCH), smoothened (SMO), and Gli. Epithelilal derived PDGF interacts with PDGFRα on DP primary cilia, which, together with Shh, promotes the expression and secretion of noggin in mesenchymal cells. Noggin promotes epithelial BMP inhibition leading to Lef-1 expression, which, coupled with Wnt/β-catenin-induced activation, drives further Shh expression. Red arrows indicate a Shh-noggin-positive amplification loop that laminin-511 facilitates.

Materials and methods

Primary antibodies

The following antibodies were used: anti-laminin α5 chain rabbit pAb (Patton et al. 1999); rat anti-e-cadherin and p-cadherin mAbs (Zymed); rabbit anti-collagen VII pAb (Ortiz-Urda et al. 2005); rabbit anti-β-catenin, PECAM, PDGFRα, and p-PDGFRα Tyr720/754 and goat anti-Lef-1 pAbs (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies); rat anti-noggin mAb RP57-16 (Regeneron); rat anti-perlecan mAb (Chemicon); rabbit anti-smad 1/5/8 pAb (Cell Signaling); hamster anti-integrin β1 blocking IgM mAb (Mendrick and Kelly 1993) (Ha2/5; BD Pharmingen); hamster IgM (G235-1; BD Biosciences); β3 integrin blocking antibody (Ashkar et al. 2000) (2C9.G2; BD Biosciences); rat anti-CD133 mAb (eBioscience); rabbit anti-keratin 17 pAb (DAKO); rabbit anti-Ki67 pAb (Neomarkers); mouse anti-acetylated α-tubulin mAb and rabbit anti-β-actin pAb (Sigma); and rabbit anti-polaris pAb (Taulman et al. 2001).

Animals

Laminin-511-null mice were genotyped as described (Miner et al. 1998) and were crossed with Topgal mice, a generous gift of Dr. R. Nusse (Stanford University, CA). Embryonic ages were determined by VisualSonics Vevo 660 ultrasound. Nude (nu/nu) mice were used for grafting.

Primary mouse mesenchymal cell isolation

Fresh E16.5 or E18.5 skin from lama5−/− or lama5+/− mice was treated with 50% Dispase (BD bioscience) for 1 h at 37°C. Epidermis was removed and dermis was either used for in situ noggin expression assays using purified Shh and PDGF (R&D Systems), or was minced and further digested with 0.25% purified collagenase type I (Worthington) for 1 h at 37°C and neutralized with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone). After washing, the cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (GIBCO-BRL) for 6 to 16 h before analysis.

Semiquantitative RT–PCR and QRT–PCR

Total RNA was extracted from the dorsal skin of lama5−/− or lama5+/−, wild-type embryos with the RNeasy Mini-kit (Qiagen). One-hundred nanograms of RNA was used for RT–PCR with the SuperScript One-Step kit (Invitrogen) and QRT–PCR with the QuanTect SYBR green kit (Qiagen). Samples were run in triplicate and normalized to GAPDH. At least three samples were used for each analysis. QuantiTect Primer Assays Kits (http://www1.qiagen.com/GeneGlobe) were used for all primers.

Immunohistochemistry

For IF, frozen tissue (7–10 μm) was blocked in 10% goat serum and incubated with primary antibodies. Cy3 and Cy2 conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson Laboratory) were used at 1:200 dilutions. V4-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was applied to visualize nuclei. Images were photographed using a Zeiss Axiovert 100 inverted microscope. For imaging primary cilium, 15–20-μm skin sections or primary mesenchymal cells from lama5−/−-null or lama5+/− wild-type mice were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 2 h at 4°C. Sections were blocked in 4% BSA in PBS with 0.5% Triton X-100 and incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-acetylated tubulin (Invitrogen). A Lieca SP2 AOBS Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope and BLENDER 3D modeling image analysis software were used for image analysis. X-gal staining on lama5−/−/Topgal mice was done as described (DasGupta and Fuchs 1999). Serial sections were stained with hematoxylin and/or alkaline phosphatase (AP) using AP substrate (NBT/BCIP; Roche).

Western blot and in vivo Wnt3a activity assay

E16.5 lama5−/−-null or lama5+/− wild-type sibling skins were lysed with RIPA lysis buffer (1% NP-40, 150 nM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-Cl at pH 7.5, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS). To determine Wnt3a activity in embryonic skin, E16.5 lama5−/−-null skin was treated with a gradient of purified Wnt3a protein (0, 20, 100, 200, and 400 ng) overnight and lysed with RIPA lysis buffer. Expression of β-catenin was detected with β-catenin antibodies as described above. NIH ImageJ software was used for the quantification of protein expression.

Hair reconstitution assay

This was performed as described (Kishimoto et al. 1999). Briefly, E16.5 primary mouse keratinocytes (7× 106 to 10 × 106) were isolated from lama5−/−-null or lama5+/− wild-type dorsal skins, combined with versican-GFP sorted DP cells (1 × 106) (Kishimoto et al. 1999), grafted with silicon graft chambers, and implanted on the back of nude mice. After 2 wk, the grafts were removed for analysis.

Exogenous proteins and hair rescuing assay

Recombinant laminin-511 lacking LG4-5 or LG3-5 domains was produced using the Free StyleTM 293 Expression system (Invitrogen) and immunoaffinity purified from conditioned media as described (Ido et al. 2004). As described (Li et al. 2003), freshly isolated E16.5 lama5−/−-null dorsal skin was incubated with one of the following: 1 × 1010 particle units of Shh adenovirus supernatant (Sato et al. 1999); 10 μg/mL purified noggin (gift of Richard Harlan); 10 μg/mL purified gremlin (R&D systems); 200 ng/mL Wnt3a (gift of Roel Nuuse); 30 μg/mL purified laminin-511 (Li et al. 2003); 30 μg/mL laminin α5LG3-5 and laminin α5LG4-5 (Ido et al. 2006); 30 μg/mL laminin-111 (Invitrogen); or 40 μg/mL anti-PDGFRα (R&D systems); anti-β1 integrin or anti-β3 integrin (BD biosciences) overnight at 4°C, with PBS, hamster IgM, or goat serum as controls. Treated skin was transplanted onto the backs of nude mice, and grafts were harvested at 9 d (five mice per condition) for microscopic analysis.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge gifts of purified noggin from Richard Harlan, University of California at Berkeley; Shh adenoviral supernatant from Ronald Crystal, Weil Cornell Medical College; purified Wnt3a protein from Roel Nusse, Stanford University; polaris pAb from Bradley Yoder, University of Alabama; and noggin mAb from Aris Economides, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. These studies were supported by the Office of Research and Development at Palo Alto VA Medical Center and NIH grants AR44012 and AR47223 (to M.P.M.).

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available at http://www.genesdev.org.

Article is online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.1689908.

References

- Andl T., Reddy S.T., Gaddapara T., Millar S.E. WNT signals are required for the initiation of hair follicle development. Dev. Cell. 2002;2:643–653. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashkar S., Weber G.F., Panoutsakopoulou V., Sanchirico M.E., Jansson M., Zawaideh S., Rittling S.R., Denhardt D.T., Glimcher M.J., Cantor H. Eta-1 (osteopontin): An early component of type-1 (cell-mediated) immunity. Science. 2000;287:860–864. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5454.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaess S., Graus-Porta D., Belvindrah R., Radakovits R., Pons S., Littlewood-Evans A., Senften M., Guo H., Li Y., Miner J.H., et al. β1-integrins are critical for cerebellar granule cell precursor proliferation. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:3402–3412. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5241-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanpain C., Fuchs E. Epidermal stem cells of the skin. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2006;22:339–373. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botchkarev V.A. Bone morphogenetic proteins and their antagonists in skin and hair follicle biology. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2003;120:36–47. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botchkarev V.A., Botchkareva N.V., Roth W., Nakamura M., Chen L.H., Herzog W., Lindner G., McMahon J.A., Peters C., Lauster R., et al. Noggin is a mesenchymally derived stimulator of hair-follicle induction. Nat. Cell Biol. 1999;1:158–164. doi: 10.1038/11078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botchkarev V.A., Botchkareva N.V., Nakamura M., Huber O., Funa K., Lauster R., Paus R., Gilchrest B.A. Noggin is required for induction of the hair follicle growth phase in postnatal skin. FASEB J. 2001;15:2205–2214. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0207com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brakebusch C., Grose R., Quondamatteo F., Ramirez A., Jorcano J.L., Pirro A., Svensson M., Herken R., Sasaki T., Timpl R., et al. Skin and hair follicle integrity is crucially dependent on β1 integrin expression on keratinocytes. EMBO J. 2000;19:3990–4003. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.15.3990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti F.J., Rudling R.J., Robson A., Hodivala-Dilke K.M. α3β1-integrin regulates hair follicle but not interfollicular morphogenesis in adult epidermis. J. Cell Sci. 2003;116:2737–2747. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DasGupta R., Fuchs E. Multiple roles for activated LEF/TCF transcription complexes during hair follicle development and differentiation. Development. 1999;126:4557–4568. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.20.4557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhouailly D. Dermo-epidermal interactions between birds and mammals: Differentiation of cutaneous appendages. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 1973;30:587–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassler R., Georges-Labouesse E., Hirsch E. Genetic analyses of integrin function in mice. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1996;8:641–646. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80105-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes K.J., McKenzie I.A., Mill P., Smith K.M., Akhavan M., Barnabe-Heider F., Biernaskie J., Junek A., Kobayashi N.R., Toma J.G., et al. A dermal niche for multipotent adult skin-derived precursor cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004;6:1082–1093. doi: 10.1038/ncb1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraris C., Chevalier G., Favier B., Jahoda C.A., Dhouailly D. Adult corneal epithelium basal cells possess the capacity to activate epidermal, pilosebaceous and sweat gland genetic programs in response to embryonic dermal stimuli. Development. 2000;127:5487–5495. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.24.5487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fliniaux I., Viallet J.P., Dhouailly D., Jahoda C.A. Transformation of amnion epithelium into skin and hair follicles. Differentiation. 2004;72:558–565. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2004.07209009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georges-Labouesse E., Messaddeq N., Yehia G., Cadalbert L., Dierich A., Le Meur M. Absence of integrin α6 leads to epidermolysis bullosa and neonatal death in mice. Nat. Genet. 1996;13:370–373. doi: 10.1038/ng0796-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grose R., Fantl V., Werner S., Chioni A.M., Jarosz M., Rudling R., Cross B., Hart I.R., Dickson C. The role of fibroblast growth factor receptor 2b in skin homeostasis and cancer development. EMBO J. 2007;26:1268–1278. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbleib J.M., Nelson W.J. Cadherins in development: Cell adhesion, sorting, and tissue morphogenesis. Genes & Dev. 2006;20:3199–3214. doi: 10.1101/gad.1486806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy M.H. The secret life of the hair follicle. Trends Genet. 1992;8:55–61. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(92)90350-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi K., Mochizuki M., Nomizu M., Uchinuma E., Yamashina S., Kadoya Y. Inhibition of hair follicle growth by a laminin-1 G-domain peptide, RKRLQVQLSIRT, in an organ culture of isolated vibrissa rudiment. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2002;118:712–718. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.01730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtkotter O., Nieswandt B., Smyth N., Muller W., Hafner M., Schulte V., Krieg T., Eckes B. Integrin α2-deficient mice develop normally, are fertile, but display partially defective platelet interaction with collagen. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:10789–10794. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112307200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes R.O. Integrins: Bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 2002;110:673–687. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ido H., Harada K., Futaki S., Hayashi Y., Nishiuchi R., Natsuka Y., Li S., Wada Y., Combs A.C., Ervasti J.M., et al. Molecular dissection of the α-dystroglycan- and integrin-binding sites within the globular domain of human laminin-10. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:10946–10954. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313626200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ido H., Harada K., Yagi Y., Sekiguchi K. Probing the integrin-binding site within the globular domain of laminin-511 with the function-blocking monoclonal antibody 4C7. Matrix Biol. 2006;25:112–117. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y., Hamazaki T.S., Ohnuma K., Tamaki K., Asashima M., Okochi H. Isolation of murine hair-inducing cells using the cell surface marker prominin-1/CD133. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2007;127:1052–1060. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamora C., DasGupta R., Kocieniewski P., Fuchs E. Links between signal transduction, transcription and adhesion in epithelial bud development. Nature. 2003;422:317–322. doi: 10.1038/nature01458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamora C., Lee P., Kocieniewski P., Azhar M., Hosokawa R., Chai Y., Fuchs E. A signaling pathway involving TGF-β2 and snail in hair follicle morphogenesis. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen P.J., Yang T., Yu D.W., Baker M.S., Risse B., Sun T.T., Lavker R.M. Serpins in the human hair follicle. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2000;114:917–922. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R.G., Li X., Gray P.D., Kuang J., Clayton F., Samowitz W.S., Madison B.B., Gumucio D.L., Kuwada S.K. Conditional deletion of β1 integrins in the intestinal epithelium causes a loss of Hedgehog expression, intestinal hyperplasia, and early postnatal lethality. J. Cell Biol. 2006;175:505–514. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200602160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamimura J., Lee D., Baden H.P., Brissette J., Dotto G.P. Primary mouse keratinocyte cultures contain hair follicle progenitor cells with multiple differentiation potential. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1997;109:534–540. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12336704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson L., Bondjers C., Betsholtz C. Roles for PDGF-A and sonic hedgehog in development of mesenchymal components of the hair follicle. Development. 1999;126:2611–2621. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.12.2611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khokha M.K., Hsu D., Brunet L.J., Dionne M.S., Harland R.M. Gremlin is the BMP antagonist required for maintenance of Shh and Fgf signals during limb patterning. Nat. Genet. 2003;34:303–307. doi: 10.1038/ng1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikkawa Y., Sanzen N., Sekiguchi K. Isolation and characterization of laminin-10/11 secreted by human lung carcinoma cells. Laminin-10/11 mediates cell adhesion through integrin α3 β1. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:15854–15859. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikkawa Y., Sanzen N., Fujiwara H., Sonnenberg A., Sekiguchi K. Integrin binding specificity of laminin-10/11: Laminin-10/11 are recognized by α3 β1, α6 β1 and α6 β4 integrins. J. Cell Sci. 2000;113:869–876. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.5.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikkawa Y., Sasaki T., Nguyen M.T., Nomizu M., Mitaka T., Miner J.H. The LG1-3 tandem of laminin α5 harbors the binding sites of Lutheran/basal cell adhesion molecule and α3β1/α6β1 integrins. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:14853–14860. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611706200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishimoto J., Ehama R., Wu L., Jiang S., Jiang N., Burgeson R.E. Selective activation of the versican promoter by epithelial–mesenchymal interactions during hair follicle development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1999;96:7336–7341. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishimoto J., Burgeson R.E., Morgan B.A. Wnt signaling maintains the hair-inducing activity of the dermal papilla. Genes & Dev. 2000;14:1181–1185. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Tzu J., Chen Y., Zhang Y.P., Nguyen N.T., Gao J., Bradley M., Keene D.R., Oro A.E., Miner J.H., et al. Laminin-10 is crucial for hair morphogenesis. EMBO J. 2003;22:2400–2410. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Edgar D., Fassler R., Wadsworth W., Yurchenco P.D. The role of laminin in embryonic cell polarization and tissue organization. Dev. Cell. 2003;4:613–624. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00128-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandler M., Neubuser A. FGF signaling is required for initiation of feather placode development. Development. 2004;131:3333–3343. doi: 10.1242/dev.01203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinkovich M.P., Herron G.S., Khavari P.A., Bauer E.A. Inherited epidermolysis bullosa. In: Freedberg I.M., et al., editors. Fitzpatrick’s dermatology in general medicine. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2003. pp. 596–609. [Google Scholar]

- Mendrick D.L., Kelly D.M. Temporal expression of VLA-2 and modulation of its ligand specificity by rat glomerular epithelial cells in vitro. Lab. Invest. 1993;69:690–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miner J., Lewis R., Sanes J. Molecular cloning of a novel laminin chain, α5, and widespread expression in adult mouse tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:28523–28526. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.48.28523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miner J.H., Cunningham J., Sanes J.R. Roles for laminin in embryogenesis: Exencephaly, syndactyly, and placentopathy in mice lacking the laminin α5 chain. J. Cell Biol. 1998;143:1713–1723. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.6.1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanba D., Hieda Y., Nakanishi Y. Remodeling of desmosomal and hemidesmosomal adhesion systems during early morphogenesis of mouse pelage hair follicles. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2000;114:171–177. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiuchi R., Takagi J., Hayashi M., Ido H., Yagi Y., Sanzen N., Tsuji T., Yamada M., Sekiguchi K. Ligand-binding specificities of laminin-binding integrins: A comprehensive survey of laminin–integrin interactions using recombinant α3β1, α6β1, α7β1 and α6β4 integrins. Matrix Biol. 2006;25:189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noakes P.G., Gautam M., Mudd J., Sanes J.R., Merlie J.P. Aberrant differentiation of neuromuscular junctions in mice lacking s-laminin/laminin β2. Nature. 1995;374:258–262. doi: 10.1038/374258a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oro A.E., Scott M.P. Splitting hairs: Dissecting roles of signaling systems in epidermal development. Cell. 1998;95:575–578. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81624-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Urda S., Garcia J., Green C.L., Chen L., Lin Q., Veitch D.P., Sakai L.Y., Lee H., Marinkovich M.P., Khavari P.A. Type VII collagen is required for Ras-driven human epidermal tumorigenesis. Science. 2005;307:1773–1776. doi: 10.1126/science.1106209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton B.L., Connoll A.M., Martin P.T., Cunningham J.M., Mehta S., Pestronk A., Miner J.H., Sanes J.R. Distribution of ten laminin chains in dystrophic and regenerating muscles. Neuromuscul. Disord. 1999;9:423–433. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(99)00033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearton D.J., Yang Y., Dhouailly D. Transdifferentiation of corneal epithelium into epidermis occurs by means of a multistep process triggered by dermal developmental signals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2005;102:3714–3739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500344102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petiot A., Conti F.J., Grose R., Revest J.M., Hodivala-Dilke K.M., Dickson C. A crucial role for Fgfr2-IIIb signalling in epidermal development and hair follicle patterning. Development. 2003;130:5493–5501. doi: 10.1242/dev.00788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavan S., Bauer C., Mundschau G., Li Q., Fuchs E. Conditional ablation of β1 integrin in skin. Severe defects in epidermal proliferation, basement membrane formation, and hair follicle invagination. J. Cell Biol. 2000;150:1149–1160. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.5.1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy S., Andl T., Bagasra A., Lu M.M., Epstein D.J., Morrisey E.E., Millar S.E. Characterization of Wnt gene expression in developing and postnatal hair follicles and identification of Wnt5a as a target of Sonic hedgehog in hair follicle morphogenesis. Mech. Dev. 2001;107:69–82. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00452-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousselle P., Lunstrum G.P., Keene D.R., Burgeson R.E. Kalinin: An epithelium-specific basement membrane adhesion molecule that is a component of anchoring filaments. J. Cell Biol. 1991;114:567–576. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.3.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruzzi L., Gagnoux-Palacios L., Pinola M., Belli S., Meneguzzi G., D’Alessio M., Zambruno G. A homozygous mutation in the integrin α6 gene in junctional epidermolysis bullosa with pyloric atresia. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;99:2826–2831. doi: 10.1172/JCI119474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato N., Leopold P.L., Crystal R.G. Induction of the hair growth phase in postnatal mice by localized transient expression of Sonic hedgehog. J. Clin. Invest. 1999;104:855–864. doi: 10.1172/JCI7691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherz P.J., Harfe B.D., McMahon A.P., Tabin C.J. The limb bud Shh-Fgf feedback loop is terminated by expansion of former ZPA cells. Science. 2004;305:396–399. doi: 10.1126/science.1096966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider L., Clement C.A., Teilmann S.C., Pazour G.J., Hoffmann E.K., Satir P., Christensen S.T.2005. .PDGFRαα signaling is regulated through the primary cilium in fibroblasts Curr. Biol. 151861–1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon M.B., Patton B.L., Harvey S.J., Miner J.H. A hypomorphic mutation in the mouse laminin α5 gene causes polycystic kidney disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2006;17:1913–1922. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005121298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu H., Morgan B.A. Wnt signaling through the β-catenin pathway is sufficient to maintain, but not restore, anagen-phase characteristics of dermal papilla cells. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2004;122:239–245. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202X.2004.22224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonoda T., Asada Y., Kurata S., Takayasu S. The mRNA for protease nexin-1 is expressed in human dermal papilla cells and its level is affected by androgen. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1999;113:308–313. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark J., Andl T., Millar S.E. Hairy math: Insights into hair-follicle spacing and orientation. Cell. 2007;128:17–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St-Jacques B., Dassule H.R., Karavanova I., Botchkarev V.A., Li J., Danielian P.S., McMahon J.A., Lewis P.M., Paus R., McMahon A.P. Sonic hedgehog signaling is essential for hair development. Curr. Biol. 1998;8:1058–1068. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70443-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taulman P.D., Haycraft C.J., Balkovetz D.F., Yoder B.K. Polaris, a protein involved in left–right axis patterning, localizes to basal bodies and cilia. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001;12:589–599. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.3.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Neut R., Cachaço A.S., Thorsteinsdóttir S., Janssen H., Prins D., Bulthuis J., van der Valk M., Calafat J., Sonnenberg A. Partial rescue of epithelial phenotype in integrin β4 null mice by a keratin-5 promoter driven human integrin β4 transgene. J. Cell Sci. 1999;112:3911–3922. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.22.3911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal F., Aberdam D., Miquel C., Christiano A.M., Pulkkinen L., Uitto J., Ortonne J.P., Meneguzzi G. Integrin β4 mutations associated with junctional epidermolysis bullosa with pyloric atresia. Nat. Genet. 1995;10:229–234. doi: 10.1038/ng0695-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H., Talts J.F. β1 integrin and α-dystroglycan binding sites are localized to different laminin-G-domain-like (LG) modules within the laminin α5 chain G domain. Biochem. J. 2003;371:289–299. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]