Abstract

PURPOSE

This study aimed to determine the association between advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and glaucoma based on the known synergism between oxidative stress with AGEs and the evidence of oxidative stress during glaucomatous neurodegeneration.

METHODS

The extent and cellular localization of immunolabeling for AGEs and their receptor, RAGE, were determined in histologic sections of the retina and optic nerve head obtained from 38 donor eyes with glaucoma and 30 eyes from age-matched donors without glaucoma.

RESULTS

The extent of AGE and RAGE immunolabeling was greater in older than in younger donor eyes. However, compared with age-matched controls, an enhanced accumulation of AGEs and an up-regulation of RAGE were detectable in the glaucomatous retina and optic nerve head. Although some retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) and glia exhibited intracellular immunolabeling for AGEs, increased AGE immunolabeling in glaucomatous eyes was predominantly extracellular and included laminar cribriform plates in the optic nerve head. Some RAGE immunolabeling was detectable on RGCs; however, increased RAGE immunolabeling in glaucomatous eyes was predominant on glial cells, primarily Müller cells.

CONCLUSIONS

Given that the generation of AGEs is an age-dependent event, increased AGE accumulation in glaucomatous tissues supports that an accelerated aging process accompanies neurodegeneration in glaucomatous eyes. One of the potential consequences of AGE accumulation in glaucomatous eyes appears to be its contribution to increased rigidity of the lamina cribrosa. The presence of RAGE on RGCs and glia also makes them susceptible to AGE-mediated events through receptor-mediated signaling, which may promote cell death or dysfunction during glaucomatous neurodegeneration.

Extended exposure of proteins to reducing sugars leads to the nonenzymatic glycation of amino groups by Maillard reaction, which alters the biological activity and degradation processes of proteins. In the early stage of this posttranslational protein modification, the synthesis of intermediates leads to the formation of Amadori compounds. In the late stage, advanced glycation end products (AGEs) irreversibly form through cross-linking after a complex cascade of chemical modifications, including “oxidation.” These reactive products, formed on intracellular and extracellular proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, have complex structures that exhibit pigmentation and fluorescence properties. Several AGEs have been chemically characterized, whereas new compounds remain to be identified. Studies of the contribution of protein glycation to diseases have been primarily focused on its relationship to diabetes and diabetes-related complications, which in the eye include retinopathy, optic neuropathy, and cataract.1 However, it has become clear that glycation-associated damage is not limited to patients with diabetes. Although it does not cause rapid or remarkable cell damage, glycation advances slowly and, in conjunction with oxidation, accompanies every fundamental process of cellular metabolism. Such alterations affect the physiological aging process because AGEs accumulate in various tissues in the course of aging.2,3 Mostly because of their association with oxidative stress, AGEs have also been implicated in many neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and Huntington disease.4,5 As in many other age-dependent neurodegenerative diseases of the brain, oxidative stress-associated age-dependent pathogenic processes are not unexpected in glaucoma because this disease is also more common in the elderly.6

AGEs are commonly thought to exacerbate disease progression through two general mechanisms. First, these modified proteins form detergent-insoluble and protease-resistant non-degradable aggregates and impair normal cellular/tissue functions. In neurons, such aggregates may interfere with axonal transport and intracellular protein traffic.7 Second, AGEs modulate cellular function through binding to specific receptors. AGE-binding receptors, which are mostly found on monocytes, macrophages, endothelial cells, pericytes, microglia, and astrocytes, include receptor for AGE (RAGE). RAGE is a multiligand signal transduction receptor of the immunoglobulin superfamily. 2,8 Binding of AGEs to receptors such as RAGE induces the release of profibrotic cytokines, such as TGF-β, and proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-6. Cell activation in response to AGE-modified proteins has also been associated with increased expression of extracellular matrix proteins, vascular adhesion molecules, and growth factors. However, depending on the cell type and concurrent signaling, RAGE-mediated events result not only in cell activation/proliferation, chemotaxis, and angiogenesis, but also in the generation of reactive oxygen species and apoptotic cell death.2–4,8 Pharmacologic inhibition of RAGE-mediated cell activation with specific antagonists has been proposed as a therapeutic intervention in diseases in which AGE accumulation is a suspected etiological factor for vascular complications of diabetes, renal insufficiency, atherosclerosis, and neurodegeneration.9,10

Thus, AGEs lead to the generation of reactive oxygen species, whereas AGE production is promoted by oxidative stress. Based on such a synergism between AGEs and oxidative stress, along with the growing evidence of oxidative stress during glaucomatous neurodegeneration,11 this study aimed to determine the association of AGEs and their receptor, RAGE, with glaucoma, which is also an age-dependent disease.6 Through immunohistochemical analysis, the extent and cellular localization of AGE and RAGE were determined in the retina and optic nerve head of eyes of donors with glaucoma compared with control eyes from age-matched donors. These revealed an enhanced accumulation of AGEs and an up-regulation of RAGE in the glaucomatous retina and optic nerve head, which support that an accelerated aging process accompanies neurodegeneration in glaucomatous eyes. Findings of this study suggest that one of the consequences of AGE accumulation in glaucomatous eyes may be the contribution of these aggregates to increased rigidity of the lamina cribrosa in the glaucomatous optic nerve head. The presence of RAGE on RGCs and glia, including mainly Müller cells, also makes them susceptible to AGE-mediated events through receptor-mediated signaling, which may promote cell death or dysfunction in patients with glaucoma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human Donor Eyes

Thirty-eight donor eyes with diagnoses of glaucoma (age range, 54–94 years) and 30 eyes from age-matched donors without glaucoma (age range, 44–94 years) were obtained from the Glaucoma Research Foundation (San Francisco, CA), the Mid-America Eye Bank (St. Louis, MO), and the Kentucky Lions Eye Bank (Louisville, KY) and from Drs. Martin B. Wax (Alcon Laboratories, Fort Worth, TX), Deepak P. Edward (University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL), Douglas H. Johnson (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN), Balwantray C. Chauhan, and Raymond P. LeBlanc (Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada). All human donor eyes were handled according to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Clinical findings of glaucomatous donors were well documented and included intraocular pressure readings, optic disk assessments, and visual field tests (Table 1). Control donors had no history of eye disease. No donors had diabetes, collagen vascular disease, infection, or sepsis. The cause of death for all donors included in this study was acute myocardial infarction or cardiopulmonary failure.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and Clinical Data of Donor Eyes

| Age (y) | Sex | Diagnosis | Average IOP | C/D | VF Damage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donors with glaucoma | ||||||

| 1 | 54 | M | POAG | 19 | 0.7 | Moderate |

| 2 | 54 | M | POAG | 20 | 0.7 | Moderate |

| 3 | 56 | F | POAG | 18 | 0.9 | Advanced |

| 4 | 59 | M | POAG | 18 | 0.6 | Moderate |

| 5 | 59 | M | POAG | 18 | 0.8 | Moderate |

| 6 | 68 | F | NPG | 16 | 0.8 | Moderate |

| 7 | 69 | F | POAG | 16 | 0.5 | Moderate |

| 8 | 69 | F | POAG | 17 | 0.5 | Moderate |

| 9 | 70 | M | POAG | 19 | 0.6 | Moderate |

| 10 | 70 | M | POAG | 19 | 0.7 | Moderate |

| 11 | 72 | F | POAG | 21 | 0.8 | Moderate |

| 12 | 72 | F | POAG | 18 | 0.7 | Moderate |

| 13 | 74 | F | POAG | 20 | 0.7 | Moderate |

| 14 | 74 | F | NPG | 16 | 0.8 | Moderate |

| 15 | 74 | F | NPG | 17 | 0.9 | Advanced |

| 16 | 75 | F | NPG | 16 | 0.85 | Moderate |

| 17 | 75 | F | NPG | 15 | 0.8 | Mild |

| 18 | 76 | F | POAG | 18 | 0.9 | Advanced |

| 19 | 76 | M | POAG | 18 | 1.0 | Advanced |

| 20 | 76 | M | POAG | 25 | 1.0 | Advanced |

| 21 | 78 | M | POAG | 22 | N/A | N/A |

| 22 | 79 | F | POAG | 20 | 0.7 | Moderate |

| 23 | 79 | F | POAG | 13 | 0.9 | Advanced |

| 24 | 82 | M | POAG | 23 | N/A | N/A |

| 25 | 82 | F | POAG | 24 | 0.8 | Moderate |

| 26 | 82 | F | NPG | 15 | 0.8 | Moderate |

| 27 | 82 | F | NPG | 15 | 0.8 | Moderate |

| 28 | 84 | F | NPG | 13 | 0.95 | Advanced |

| 29 | 84 | F | NPG | 12 | 0.95 | Advanced |

| 30 | 85 | M | POAG | 17 | 1.0 | Advanced |

| 31 | 85 | M | POAG | 22 | 0.5 | Moderate |

| 32 | 91 | F | POAG | 21 | 0.9 | Advanced |

| 33 | 91 | F | POAG | 20 | 0.8 | Moderate |

| 34 | 91 | F | POAG | 16 | 0.7 | Moderate |

| 35 | 91 | F | POAG | 16 | 0.9 | Advanced |

| 36 | 94 | F | POAG | 16 | 0.7 | Moderate |

| 37 | 94 | M | POAG | 22 | 0.8 | Moderate |

| 38 | 94 | M | POAG | 20 | 0.5 | Moderate |

| Control donors | ||||||

| 1 | 44 | M | — | — | — | — |

| 2 | 44 | M | — | — | — | — |

| 3 | 49 | F | — | — | — | — |

| 4 | 49 | F | — | — | — | — |

| 5 | 55 | M | — | — | — | — |

| 6 | 55 | M | — | — | — | — |

| 7 | 56 | M | — | — | — | — |

| 8 | 56 | M | — | — | — | — |

| 9 | 59 | F | — | — | — | — |

| 10 | 59 | F | — | — | — | — |

| 11 | 68 | F | — | — | — | — |

| 12 | 68 | F | — | — | — | — |

| 13 | 70 | M | — | — | — | — |

| 14 | 70 | M | — | — | — | — |

| 15 | 73 | F | — | — | — | — |

| 16 | 73 | F | — | — | — | — |

| 17 | 76 | F | — | — | — | — |

| 18 | 76 | F | — | — | — | — |

| 19 | 79 | M | — | — | — | — |

| 20 | 79 | M | — | — | — | — |

| 21 | 82 | F | — | — | — | — |

| 22 | 82 | F | — | — | — | — |

| 23 | 84 | F | — | — | — | — |

| 24 | 84 | F | — | — | — | — |

| 25 | 85 | M | — | — | — | — |

| 26 | 85 | M | — | — | — | — |

| 27 | 91 | F | — | — | — | — |

| 28 | 91 | F | — | — | — | — |

| 29 | 94 | F | — | — | — | — |

| 30 | 94 | F | — | — | — | — |

IOP, intraocular pressure; C/D, cup-to-disk ratio; NPG, normal pressure glaucoma; POAG, primary open-angle glaucoma; VF, visual field.

Procedures

All donor eyes were fixed within 12 hours of death and were processed for 5-µm paraffin-embedded sagittal tissue sections. To determine the extent and cellular localization of AGEs and RAGE, immunoperoxidase labeling and double-immunofluorescence labeling were performed. All procedures were similar to that previously described.12–15 A brief description of the immunolabeling procedures are given here. For each procedure, at least six histologic sections were used from each eye, including those obtained from the superior and inferior halves of the retina. All slides subjected to immunohistochemical analysis were masked for the identity and diagnosis of the donors and numbered before immunolabeling by a technician unfamiliar with the retinal and optic nerve head abnormalities.

The intensity of immunolabeling was first qualitatively graded as negative (−), faint (+), moderate (++), and strong (+++). To obtain complementary information, quantitative image analysis was performed to determine the extent of immunolabeling, as previously described.14,15 For this purpose, immunolabeling was quantitatively graded on digitized images in a masked fashion by measuring the specific immunolabeling areas using image analysis software (Axiovision; Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY), as recently described.16 A percentage value was expressed for each slide as the average ratio of the measurement to the total area analyzed, multiplied by 100. The mean extent of immunolabeling was calculated for each eye after subtracting the value obtained from the negative control slide.

To determine age-dependent alterations in immunolabeling, two age groups—70 years and older and 60 years and younger—were compared. However, for comparisons of immunolabeling between glaucomatous and control eyes, four control eyes (with a donor age younger than 55 years) were excluded for appropriate age matching.

Immunoperoxidase Labeling

Histologic sections from normal and glaucomatous eyes were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and pretreated with 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol to decrease endogenous peroxidase activity. After washing with phosphate-buffered saline solution containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin, slides were incubated with 20% inactivated serum (Chemicon International Inc., Temecula, CA) for 30 minutes at room temperature to block background staining. Slides were then incubated with a monoclonal mouse antibody against AGEs (1:100; CosmoBio Co., Tokyo, Japan) or a polyclonal goat antibody against RAGE (1:100; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) for 16 hours at 4°C. The AGE antibody used recognizes different epitopes, including N(epsilon)-(carboxymethyl)-lysine, which is a major AGE structure17,18 and a major epitope for RAGE binding.19 After washing, slides were incubated with biotinylated anti-mouse or anti-goat IgG (1:400; Chemicon International Inc.) for 1 hour at room temperature and then with ABC solution (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 1 hour at room temperature. After several washes, color was developed by incubation with 3,3-diamino-benzidine tetrahydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) as cosubstrate for 5 to 7 minutes. Slides were then counterstained with hematoxylin. The primary antibody was eliminated from the incubation medium, or serum (Sigma-Aldrich) was used to replace the primary antibody to serve as the negative control. After washing and mounting, slides were examined through a phase-contrast microscope, and images were recorded by digital photomicrography (Carl Zeiss).

Double-Immunofluorescence Labeling

Histologic sections were incubated with a mixture of anti-mouse and anti-rabbit primary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature. Primary antibodies to AGEs and RAGE were the same as described. In addition, a rabbit antibody against glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) was used as a marker of astrocytes, and an antivimentin antibody (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) was used to recognize Müller cells. To identify RGCs, a rabbit antibody to brn-3 (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used. After incubation with primary antibody and a washing step, slides were incubated with a mixture of Alexa Fluor 488- or 568-conjugated anti-mouse, anti-goat, or anti-rabbit IgGs (1:400; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for another hour at room temperature. Negative controls were performed by replacing the primary antibody with serum, or sections were incubated with each primary antibody followed by the inappropriate secondary antibody to determine that each secondary antibody was specific to the species against which it was made. After washing and mounting, slides were examined and images were recorded under a fluorescence microscope equipped with a digital camera (Carl Zeiss).

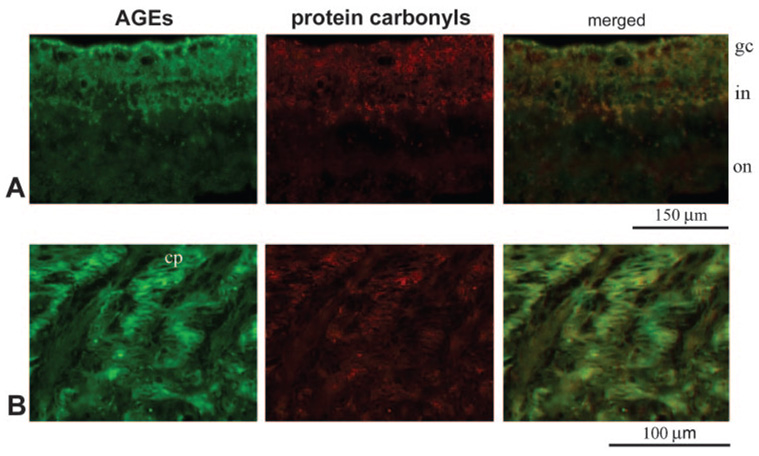

To determine whether AGE generation is associated with protein oxidation in glaucomatous eyes, double-immunofluorescence labeling was also performed for AGEs and protein carbonyls, as previously described.11 Briefly, additional sections were incubated with 0.01% 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH; Sigma-Aldrich) in 2 N HCl for 1 hour at room temperature. After washing and blocking steps, slides were incubated with a polyclonal goat antibody recognizing DNP (1:100; Biomeda, Foster City, CA) and the anti-AGE antibody described. Secondary antibodies included Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated anti- goat IgG and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1:400; Molecular Probes). Anti-DNP antibody or the DNPH treatment was omitted, or the primary antibody was replaced with serum, to confirm the specificity of immunolabeling.

RESULTS

Retinal Immunolabeling for AGEs

Immunoperoxidase labeling of the retina for AGEs was fairly detectable in control donor eyes and limited to the inner limiting membrane and blood vessels. As summarized in Figure 1, the extent of retinal AGE immunolabeling was relatively greater in eyes of donors older than 70 (n = 18) than in eyes of donors younger than 60 (n = 10); however, immunolabeling for AGEs in these two age groups was qualitatively graded as negative to faint (Figs. 2A, 2B).

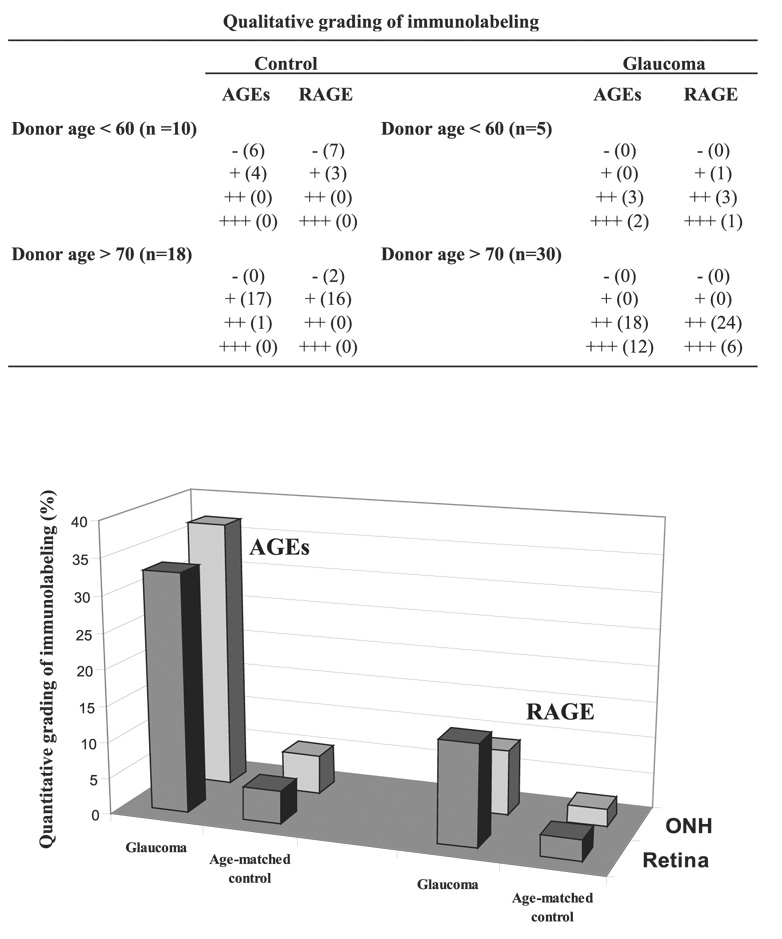

FIGURE 1.

The intensity of immunolabeling for AGEs and RAGE was first qualitatively graded as negative (−), faint (+), moderate (++), and strong (+++). Immunolabeling was then quantitatively graded on digitized images in a masked fashion by measuring the specific immunolabeling areas. A percentage value was expressed for each slide relative to the average ratio of the total area analyzed. Mean values are presented. Immunolabeling for AGEs and RAGE were qualitatively and quantitatively greater in the eyes of donors with glaucoma than in those of age-matched controls. Age-matched control data shown do not include four control eyes of donors younger than 55 years for appropriate age matching (38 glaucomatous vs. 26 control eyes).

In contrast, based on qualitative evaluation, immunoper-oxidase labeling for AGEs was more prominent in histologic slides obtained from older (70 and older; n = 30) and younger (60 and younger; n = 5) donors with glaucoma than from age-matched controls. Although the intensity of retinal AGE immunolabeling exhibited individual differences, it was qualitatively graded as moderate or strong in glaucomatous eyes (Figs. 2C, 2D). Digital image analysis revealed that the extent of AGE immunolabeling (mean ± SD) was 33% ± 4% in the retinas of donors with glaucoma but less than 5% in age-matched controls (Fig. 1). It should be noted that control eyes of donors older than 55 (4 eyes) were not included in these comparisons between control and glaucomatous eyes because none of the donors with glaucoma were younger than 54.

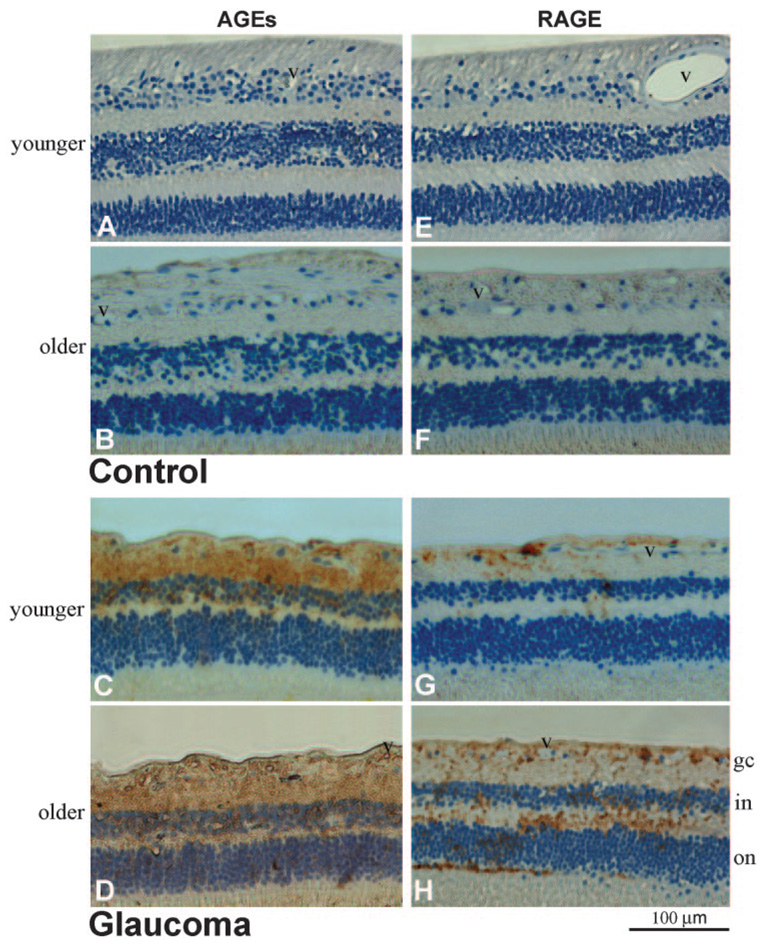

FIGURE 2.

Immunoperoxidase labeling of the retina for AGEs and RAGE. (A, B) Histologic retinal sections obtained from a 55-year-old and a 94-year-old donor without glaucoma, respectively (donors 5 and 27). The extent of AGE immunolabeling was greater in older than in younger eyes. (C, D) AGE immunolabeling of retinal sections obtained from moderately damaged glaucomatous eyes (donors 1 and 34). Retinal immunolabeling for AGEs was more prominent in eyes of donors with glaucoma than in age-matched controls. Note the prominent AGE immunolabeling in the inner limiting membrane and around retinal blood vessels (v). Scattered cells in the RGC layer exhibited some immunolabeling for AGEs. Increased AGE immunolabeling in the glaucomatous retina was also determined to be associated with extracellular structures. (E, F) RAGE immunolabeling in the control retinas presented in (A) and (B), respectively. Similar to AGE immunolabeling, retinal immunoperoxidase labeling for RAGE was greater in older than in younger eyes. (G, H) RAGE immunolabeling in the glaucomatous retinas presented in (C) and (D), respectively. Retinal immunolabeling for RAGE was greater in eyes of donors with glaucoma than in those of age-matched controls. Increased RAGE immunolabeling in the glaucomatous retina was predominantly associated with the retinal distribution of Müller cells. Some RAGE immunolabeling was also detectable on scattered cells in the RGC layer and around blood vessels. Chromagen, DAB; nuclear counterstain, Mayer hematoxylin; gc, ganglion cell; in, inner nuclear; on, outer nuclear layers; v, blood vessel).

Increased immunoperoxidase labeling of the glaucomatous retina for AGEs was most prominent in the inner retinal layers. The inner limiting membrane and blood vessels exhibited prominent immunolabeling for AGEs in the glaucomatous retina. Based on morphologic characteristics and retinal distributions of cell types, some AGE immunolabeling in the glaucomatous retina also corresponded to cells in the RGC layer, which include RGCs and astrocytes. In addition, some AGE immunolabeling was detectable in other retinal layers, including inner and outer plexiform and inner and outer nuclear layers (Figs. 2C, 2D). However, microscopic findings were consistent with a prominent extracellular distribution of AGE immunolabeling in these retinal structures. To identify retinal cell types exhibiting increased immunolabeling for AGEs in glaucomatous eyes, double-immunofluorescence labeling was performed and demonstrated that, in addition to RGCs and glia exhibiting granular intracellular immunolabeling for AGEs, increased AGE immunolabeling in the glaucomatous retina was associated with extracellular components (Fig. 3A).

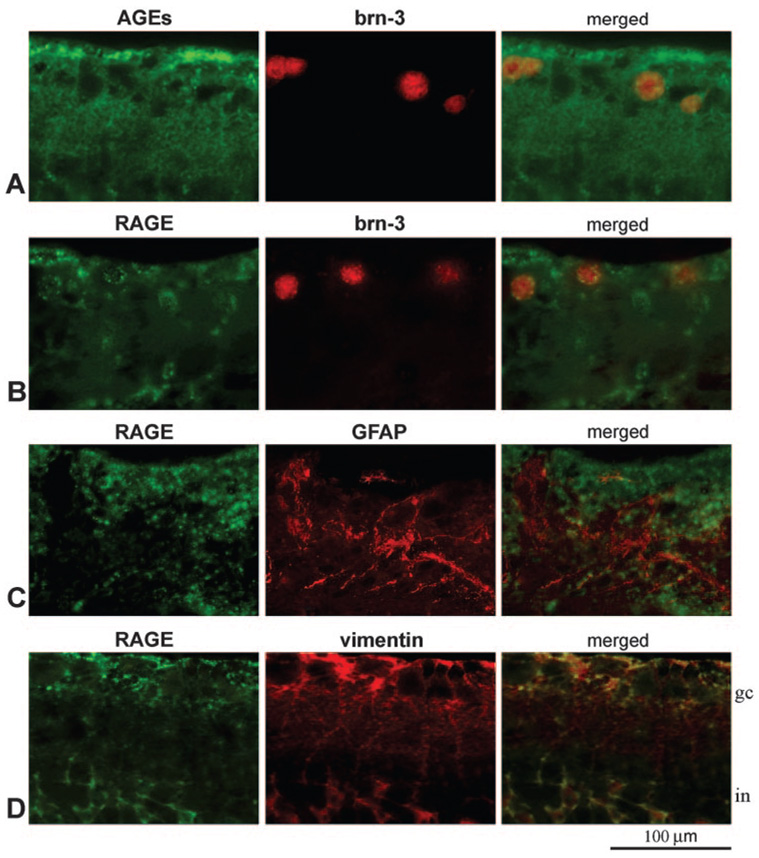

FIGURE 3.

Double-immunofluorescence labeling of the glaucomatous retina. (A) Double-immunofluorescence labeling for AGEs (green) and brn-3 (red). (B–D) Double immunolabeling for RAGE (green) and brn-3, GFAP, and vimentin, respectively (red). Images were obtained from a moderately damaged glaucomatous eye (donor 22). Brn-3-positive RGCs exhibited some granular intracellular immunolabeling for AGEs (A, yellow). However, AGE immunolabeling in the glaucomatous retina was also associated with glial cells and extracellular components. Increased RAGE immunolabeling was detectable on some brn-3-positive RGCs and GFAP-positive astrocytes (B, C, yellow). However, increased RAGE immunolabeling in the glaucomatous retina was predominantly localized to vimentin-positive Müller cells (D, yellow). gc, ganglion cell; in, inner nuclear layer.

Retinal Immunolabeling for RAGE

Similar to AGE immunolabeling, retinal immunoperoxidase labeling for RAGE was faint in histologic slides obtained from control donors in two age groups. The extent of retinal RAGE immunolabeling was relatively greater in the older group than in the younger group. However, retinal RAGE immunolabeling in these control eyes was qualitatively graded as negative to faint (Figs. 2E, 2F). In contrast, RAGE immunolabeling in the retinas of donors with glaucoma was greater than in age-matched controls and was qualitatively graded as moderate to strong (Figs. 2G, 2H). Based on quantitative image analysis, the extent of retinal RAGE immunolabeling (mean ± SD) was 14% ± 2% in the glaucomatous retina but less than 3% in age-matched control retinas (Fig. 1).

Based on the morphologic assessment of retinal cell types, increased RAGE immunolabeling of the glaucomatous retina was predominant on radial oriented cells corresponding to Müller cells, whose cell bodies are located in the inner nuclear layer and whose end feet form the inner limiting membrane. In addition to Müller cells, some RAGE immunolabeling was detectable on scattered cells in the RGC layer, including RGCs and astrocytes, and around retinal blood vessels (Figs. 2G, 2H). Double-immunofluorescence labeling demonstrated that the cellular pattern of RAGE immunolabeling was consistent with the findings of immunoperoxidase labeling. As shown in Figure 3, some RAGE immunolabeling was detectable on brn-3-positive RGCs (Fig. 3B) or GFAP-positive astrocytes (Fig. 3C). However, increased RAGE immunolabeling in glaucomatous retinas was predominantly colocalized with vimentin immunolabeling (Fig. 3D), which marks Müller cells. Müller cells located in the inner nuclear layer and their footplates contributing to the inner limiting membrane exhibited prominent RAGE immunolabeling in the glaucomatous retina.

Immunolabeling of the Optic Nerve Head for AGEs and RAGE

Similar to the control retina, immunolabeling of the optic nerve head for AGEs or RAGE was faint in control eyes (Figs. 4A, 4B). However, optic nerve head sections from glaucomatous eyes exhibited increased immunolabeling for AGEs and RAGE (Figs. 4C, 4D) in all histologic slides examined. AGE and RAGE immunolabeling of the glaucomatous optic nerve head were qualitatively graded as moderate or strong. Digital image analysis revealed that the extent of AGE immunolabeling was 36% ± 5% in the glaucomatous optic nerve head but less than 6% in age-matched controls (Fig. 1). The extent of RAGE immunolabeling in the optic nerve head was similarly greater in glaucomatous eyes (9% ± 1%) than in control eyes (less than 3%).

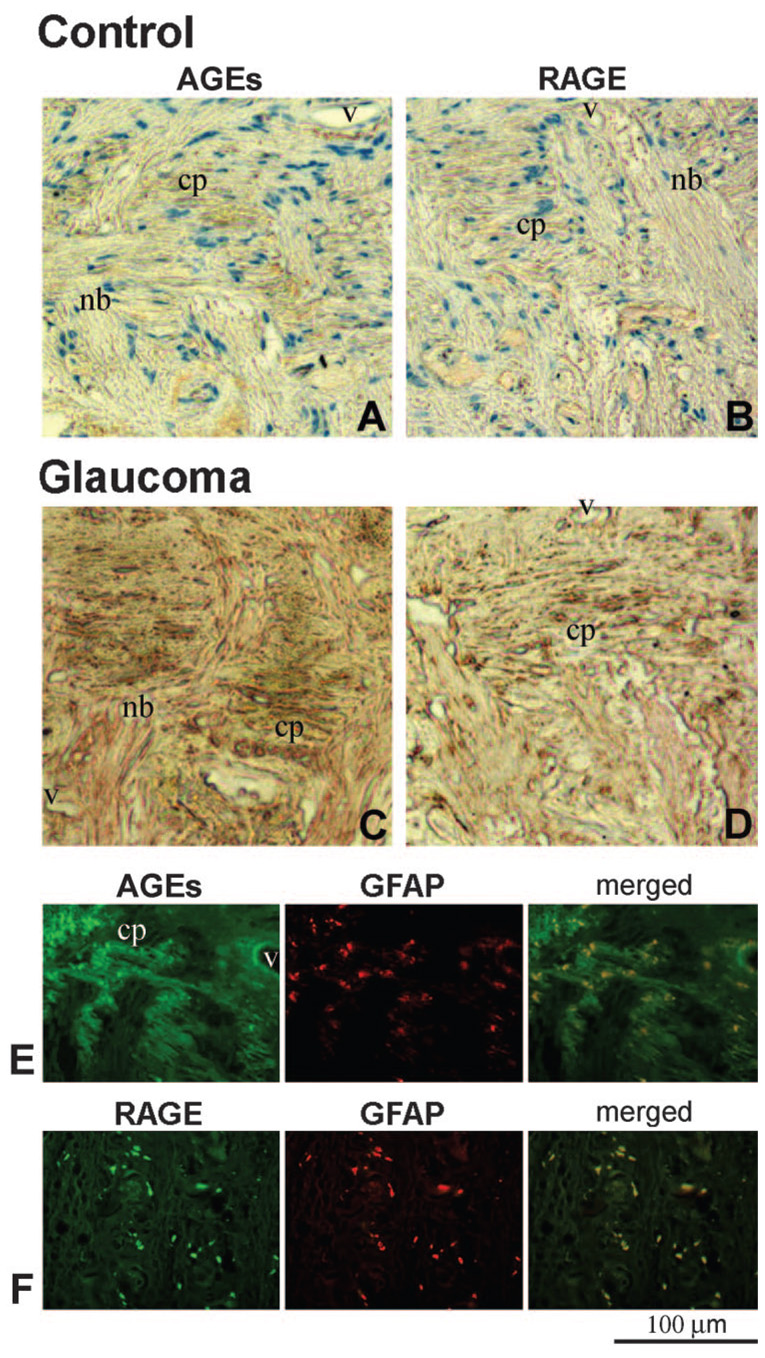

FIGURE 4.

Optic nerve head immunolabeling for AGEs and RAGE. (A, B) Immunoperoxidase labeling of the control optic nerve head (donor 21) for AGEs and RAGE, respectively. (C, D) Immunoperoxidase labeling of the glaucomatous optic nerve head (donor 25) for AGEs and RAGE, respectively. AGE and RAGE immunolabeling were greater in the eyes of donors with glaucoma than in those of age-matched controls (chromagen, DAB; nuclear counterstain, Mayer hematoxylin). Note the prominent immunolabeling of nerve bundles (nb) for AGEs in panel C. (E) Double-immunofluorescence labeling of the glaucomatous optic nerve head for AGEs (green) and GFAP (red). (F) Double-immunofluorescence labeling of the glaucomatous optic nerve head for RAGE (green) and GFAP (red). Increased AGE immunolabeling in the glaucomatous optic nerve head was mostly extracellular in the cribriform plates (cp) of the lamina cribrosa. Some GFAP-positive astrocytes (E, yellow) and nerve bundles were also positive for AGE immunolabeling. However, increased RAGE immunolabeling was mainly localized to GFAP-positive astrocytes in the glaucomatous optic nerve head (F, yellow). A Blood vessel (v) also exhibits immunolabeling for AGEs in panel E.

Based on double-immunofluorescence labeling, increased AGE immunolabeling in the glaucomatous optic nerve head was most detectable extracellularly in cribriform plates of the lamina cribrosa. Some GFAP-positive astrocytes and nerve bundles were also positive for AGE immunolabeling in these tissues (Fig. 4E). Although AGE immunolabeling of the optic nerve head was predominantly extracellular, increased RAGE immunolabeling in glaucomatous eyes was mainly localized to GFAP-positive astrocytes located at the prelaminar and laminar regions of the optic nerve head (Fig. 4F). Blood vessels also exhibited immunolabeling for AGEs and RAGE in the glaucomatous optic nerve head.

Control slides in which the primary antibody was omitted or replaced with serum were all negative for specific immunolabeling for AGEs or RAGE. Although the intensity and extent of immunolabeling and the number of immunolabeled cells exhibited individual or regional differences, increased immunolabeling of glaucomatous tissues for AGEs and RAGE was widespread and detectable in all slides examined. To determine the retinal orientation of histologic sections, 12 freshly obtained donor eyes were marked for nasal, temporal, superior, and inferior quadrants before processing. The correlation between immunolabeling and functional damage was estimated in these glaucomatous eyes. However, no correlation was detected between the location of visual field defects and AGE or RAGE immunolabeling in corresponding retinal quadrants of these individual eyes. In addition, it was considered that, because of the retrospective nature of data collection, assessment of a relationship between AGE or RAGE immunolabeling with other clinical variables would not be precisely informative.

Immunolabeling for Protein Carbonyls

Immunohistochemistry was also used to determine the distribution of protein carbonyls, markers for protein oxidation. The glaucomatous retina (mainly its inner layers) and the optic nerve head exhibited prominent immunolabeling for protein carbonyls using a specific anti-DNP antibody. Despite individual differences (moderate or strong immunolabeling), DNP immunoreactivity was detectable in all the glaucomatous eyes examined, but only control eyes of donors older than 70 exhibited faint immunolabeling for protein carbonyls. Thus, age-dependent and glaucoma-dependent characteristics of AGE and protein carbonyl immunolabeling exhibited similarities. Most important, double-immunofluorescence labeling of glaucomatous tissues for protein carbonyls and AGEs demonstrated their colocalization (Fig. 5). This finding further supports the association of AGEs with oxidative stress in glaucomatous eyes.

FIGURE 5.

Double-immunofluorescence labeling of the glaucomatous retina. (A) Double-immunofluorescence labeling of the glaucomatous retina for AGEs (green) and DNP (red). (B) Double-immunofluorescence labeling of the glaucomatous optic nerve head for AGEs (green) and DNP (red). Images were obtained from a moderately damaged glaucomatous donor eye (donor 12). DNP immunolabeling for protein carbonyls was predominant in the inner retinal layers and colocalized (yellow) with immunolabeling for AGEs. gc, ganglion cell; in, inner nuclear; on, outer nuclear layers; cp, cribriform plates of the lamina cribrosa.

DISCUSSION

This immunohistochemical study detected that in comparison with control eyes from age-matched donors, there was an increase in immunolabeling of the glaucomatous retina and optic nerve head for different AGE structures, including N(epsilon)-(carboxymethyl)lysine. Because the generation of AGEs is an age-dependent event, findings of this study support that an accelerated aging process accompanies neurodegeneration in glaucomatous eyes. Findings of this study also demonstrate that enhanced accumulation of AGEs in glaucomatous eyes is associated with oxidative stress, as assessed by protein carbonyl immunoreactivity. Protein carbonyl formation is an important marker for protein oxidation, which can arise from direct free radical attack on amino acid side chains. The distribution of protein carbonyls in the glaucomatous human retina was similar to that detected in the eyes of rats with ocular hypertension, which exhibit oxidative modification of important proteins present in RGCs and glia, including Müller cells.11 The colocalization of AGEs and protein carbonyls in the glaucomatous retina and optic nerve head supports the known synergism between AGEs and oxidative stress, in which AGEs lead to the generation of reactive oxygen species and AGE production is promoted by oxidation.20

AGEs can initiate a wide range of abnormal responses with serious consequences for macromolecular function. These include inappropriate expression of important structural proteins, enzymes, and growth factors, induction of TNF-α and nitric oxide synthase, alterations in cellular growth dynamics and migration, glial activation, accumulation of extracellular matrix molecules, promotion of vasoregulatory dysfunction, induction of oxidative cascades, and initiation of cell death pathways. Many of these are receptor-mediated events through the binding of RAGE and can be significantly reversed by pharmacologic inhibitors.21 It is now clear that AGEs are neurotoxic, 22 and they may act as mediators not only of diabetic complications but also of many age-related abnormalities, including age-related neurodegenerative diseases.1

Increasing numbers of reports confirm widespread AGE accumulation at sites of different ocular abnormalities, and various in vitro and in vivo studies highlight the putative pathophysiological role of AGEs in retinal cell dysfunction. For example, AGEs have been shown to accumulate in the diabetic retina23 and optic nerve head24 and have been associated with retinopathy.25,26 Because of the colocalization of AGEs with RAGE at sites of diabetic microvascular injury, it has also been suggested that this ligand-receptor interaction represents an important mechanism in the pathogenesis of diabetic complications. 27,28 Furthermore, inhibitors of AGE formation29–32 or RAGE28 have ameliorated neuronal dysfunction and vascular disease in diabetic eyes. In addition, it has been suggested that the accumulation of AGEs contributes to the progression of age-related macular degeneration in human eyes because they induce receptor-mediated activation of retinal pigment epithelial cells.33

Similar to other diseases, AGEs detected in glaucomatous tissues may be directly cytotoxic or may initiate receptor-mediated signaling. Increased AGE immunolabeling in glaucomatous eyes was detectable in RGCs, their axons, and glia. These intracellular aggregates may interfere with normal cellular functions, including axonal transport and intracellular protein traffic.7 However, accelerated accumulation of AGEs in glaucomatous tissues was predominant in the extracellular matrix of the retina and optic nerve head. Because AGEs accumulate with age on many long-lived macromolecules such as collagen, it is not surprising that these products were prominently detectable within the extracellular matrix. Accumulation of AGEs in the extracellular matrix may elicit several alterations, including decreased solubility, decreased susceptibility to enzymes, and changes in thermal stability, mechanical strength, and stiffness. It has been suggested that such alterations in the physicochemical properties of the extracellular matrix contribute to the development of various age-related abnormalities.34–38 Extracellular accumulation of AGEs in the glaucomatous optic nerve head may be particularly important because extracellular matrix sheets of the lamina cribrosa provide mechanical support for RGC axons.

The ability of the optic nerve head to withstand elevations in intraocular pressure decreases with increasing age because of age-related alterations in the proportion of various components of the extracellular matrix in the lamina cribrosa.39,40 In addition to these alterations, a linear increase in AGE accumulation has been observed in the aging lamina cribrosa, possibly associated with decreased elasticity of the lamina cribrosa in the elderly.41 Extensive evidence supports that the content and distribution of age-dependent alterations of the extracellular matrix are even more severe in the glaucomatous optic nerve head.42,43 Clinical observations are consistent with histopathologic findings in glaucomatous eyes.44 Current findings support that the accelerated accumulation of AGEs in laminar cribriform plates accompanies other extracellular matrix alterations in the glaucomatous optic nerve head, which influence the susceptibility of stressed axons to sustain neuronal damage in glaucomatous eyes.45,46 Increased accumulation of AGEs in laminar cribriform plates and blood vessels of the glaucomatous optic nerve head may facilitate axonal damage by compromising the ability of lamina cribrosa to bear the strain caused by elevated intraocular pressure or by impairing the microcirculation.

The AGE receptor RAGE was also up-regulated in the glaucomatous retina and optic nerve head. Some astrocytes and RGCs exhibited immunolabeling for RAGE in glaucomatous tissues; however, increased RAGE immunolabeling was predominantly localized to Müller cells in the glaucomatous retina. The up-regulation of RAGE in neurons and glia is consistent with observations in patients with brain injury.4,5,47,48 RAGE up-regulation in glaucomatous eyes suggests that in addition to direct cytotoxic effects of intracellular or extracellular AGEs, these reactive products may initiate specific receptor-mediated signaling that can promote cell death and dysfunction. The presence of RAGE on RGCs makes them susceptible targets of AGE-mediated events. Increased RAGE immunolabeling of glial cells in glaucomatous tissues similarly indicates that AGEs can modulate glial functions through receptor-mediated signaling.

A predominant up-regulation of RAGE on glial cells raises exciting possibilities. First, based on known outcomes of RAGE-mediated signaling, glial up-regulation of RAGE in glaucomatous eyes may be associated with glial activation14 and activated glial migration.49 Despite the preferential susceptibility of RGCs and their axons to primary or secondary degeneration, glial cells survive the widespread and chronic tissue stress present in the glaucomatous optic nerve head and retina.12,15 Although glial cells are relatively protected against glaucomatous injury,50 they significantly respond to glaucomatous stressors by persistently exhibiting an activated phenotype in glaucomatous human eyes.14 Chronic signaling through RAGE may explain, in part, how glial cells persistently remain activated in these eyes, even after elevated intraocular pressure is lowered.

Second, RAGE-mediated signaling in glial cells may be associated with alterations in their neurosupportive functions during glaucomatous neurodegeneration. Despite the well-known role of glial cells in supporting RGCs, considerable evidence suggests that under glaucomatous stress conditions, their neurosupportive ability may diminish and glial cells may become neurodestructive by the release of increased amounts of neurotoxic substances50 or by the activation of an aberrant immune response.51 This is supported by increased glial production of TNF-α,13 nitric oxide synthase,52 and antigen-presenting ability of glial cells53 in glaucomatous human eyes. Based on known consequences of AGE/RAGE signaling, it seems reasonable to hypothesize that age-dependent and oxidative stress-induced events mediated through AGE/RAGE signaling play a role in the decreased ability of glial cells to protect RGCs from glaucomatous injury. For example, one of the numerous neurosupportive functions of glial cells is associated with their ability to control extracellular levels of excitotoxic amino acids such as glutamate. Müller cells are known to be the primary cell type responsible for the removal of excess glutamate from the extracellular space in the retina.54–56 However, not only are glutamate transporters significantly reduced in human and experimental glaucoma,57,58 glutamine synthetase, which modulates the glutamate- glutamine cycle, is oxidatively modified during glaucomatous neurodegeneration.11 These findings lend support to the notion that besides other dysfunctions, depression of the glutamate balancing function of Müller cells caused by oxidative inactivation can facilitate RGC death in glaucoma. However, whether a specific RAGE-dependent mechanism is associated with glial cell activation or oxidative stress-associated glial dysfunction in glaucoma must be proven in future studies. It is also tempting to determine whether AGE/RAGE signaling in glial cells could be associated with their immune regulatory function during aberrant activation of the immune system in patients with glaucoma.51,59

It seems confusing that advanced glycation processes occur in nondiabetic glaucomatous eyes. However, based on the known process of AGE generation, glucose and its degradation products can participate in the aberrant glycation of proteins60,61 and the generation of AGEs.62 Energy supply for neurons in the retina is generated from glucose through the glycolytic pathway. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) is a major glycolytic enzyme in this pathway. If GAPDH activity were to decline, the two glycolytic intermediates, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate and dihydroxyacetone phosphate, would likely accumulate, leading to the production of methylglyoxal. Methylglyoxal has been identified as a precursor of AGEs in the lens63 and retina64 and has been associated with increased stiffness of the human lamina cribrosa and peripapillary sclera during the physiological aging process.65 What links such alternative metabolic routes to AGE generation in glaucoma is the evidence of oxidative modification of GAPDH in ocular hypertensive retinas.11 In fact, GAPDH is easily affected by oxidants, resulting in the loss of dehydrogenase activity.66 Therefore, it seems highly possible that a similar oxidation-induced decline in GAPDH activity during glaucomatous neurodegeneration may be associated with accelerated AGE formation in glaucomatous tissues, even in the presence of normal blood glucose levels. Such facilitated AGE formation by oxidative stress is consistent with the known synergism between reactive oxygen species and AGEs. Our more recent in vivo study using a proteomic approach has demonstrated aberrant protein glycation in ocular hypertensive and diabetic retinas and has identified common targets of this posttranslational protein modification in two different disease models (Atmaca-Sonmez P, et al. IOVS 2006;47:ARVO E-Abstract 197). Increased retinal protein glycation in rats with ocular hypertension and AGE accumulation by physiological aging through lifelong exposure to normoglycemia are consistent with the findings of increased AGE accumulation in ocular tissues of nondiabetic donors with glaucoma in the present study.

In summary, findings of this study demonstrate an enhanced accumulation of AGEs and an up-regulation of RAGE in the glaucomatous retina and optic nerve head. Known consequences of AGE/RAGE signaling suggest that key cellular events associated with glaucomatous neurodegeneration, such as oxidative stress, glial activation and dysfunction (including activated glial migration, increased glial production of TNF-α and nitric oxide synthase, and activated immunoregulatory function), inappropriate activation of signaling molecules (including mitogen-activated protein kinases and nuclear factor-κB), activated immune response, and neuronal apoptosis, may all have important links to advanced glycation processes in glaucoma. These warrant further study for a better understanding of the pathogenic importance of AGE/RAGE-mediated cytotoxicity in glaucomatous neurodegeneration.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by National Eye Institute Grants R01 EY013813 and R24 EY015636 and by an unrestricted grant to the University of Louisville Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences from Research to Prevent Blindness Inc. GT is a recipient of the Research to Prevent Blindness Sybil B. Harrington Special Scholar Award.

Footnotes

Disclosure: G. Tezel, None; C. Luo, None; X. Yang, None

References

- 1.Ahmed N. Advanced glycation end products—role in pathology of diabetic complications. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2005;67:3–21. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thornalley PJ. Cell activation by glycated proteins: AGE receptors, receptor recognition factors and functional classification of AGEs. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 1998;44:1013–1023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmidt AM, Yan SD, Yan SF, Stern DM. The biology of the receptor for advanced glycation end products and its ligands. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1498:99–111. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(00)00087-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yan SD, Chen X, Fu J, et al. RAGE and amyloid-beta peptide neurotoxicity in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 1996;382:685–691. doi: 10.1038/382685a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma L, Nicholson LF. Expression of the receptor for advanced glycation end products in Huntington’s disease caudate nucleus. Brain Res. 2004;1018:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quigley HA, Vitale S. Models of open-angle glaucoma prevalence and incidence in the United States. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38:83–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cullum NA, Mahon J, Stringer K, McLean WG. Glycation of rat sciatic nerve tubulin in experimental diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 1991;34:387–389. doi: 10.1007/BF00403175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neeper M, Schmidt AM, Brett J, et al. Cloning and expression of a cell surface receptor for advanced glycosylation end products of proteins. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:14998–15004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamagishi S, Nakamura K, Takeuchi M. Potential therapeutic implication of nifedipine, a dihydropyridine-based calcium antagonist, in advanced glycation end product (AGE)-related disorders. Med Hypotheses. 2005;65:392–394. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2004.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nitti M, d’Abramo C, Traverso N, et al. Central role of PKCä in glycoxidation-dependent apoptosis of human neurons. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;38:846–856. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tezel G, Yang X, Cai J. Proteomic identification of oxidatively modified retinal proteins in a chronic pressure-induced rat model of glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:3177–3187. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tezel G, Hernandez MR, Wax MB. Immunostaining of heat shock proteins in the retina and optic nerve head of normal and glaucomatous eyes. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:511–518. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.4.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tezel G, Li LY, Patil RV, Wax MB. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha and its receptor-1 in the retina of normal and glaucomatous eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:1787–1794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tezel G, Chauhan BC, LeBlanc RP, Wax MB. Immunohistochemical assessment of the glial mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:3025–3033. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tezel G, Wax MB. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1α in the glaucomatous retina and optic nerve head. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:1348–1356. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.9.1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tezel G, Yang X, Yang J, Wax MB. Role of tumor necrosis factor receptor-1 in the death of retinal ganglion cells following optic nerve crush injury in mice. Brain Res. 2004;996:202–212. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ikeda K, Higashi T, Sano H, et al. N (epsilon)-(carboxymethyl)lysine protein adduct is a major immunological epitope in proteins modified with advanced glycation end products of the Maillard reaction. Biochemistry. 1996;35:8075–8083. doi: 10.1021/bi9530550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wells-Knecht KJ, Brinkmann E, Wells-Knecht MC, et al. New biomarkers of Maillard reaction damage to proteins. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 96(11 suppl 5):41–47. doi: 10.1093/ndt/11.supp5.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kislinger T, Fu C, Huber B, et al. N(epsilon)-(carboxymethyl)lysine adducts of proteins are ligands for receptor for advanced glycation end products that activate cell signaling pathways and modulate gene expression. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:31740–31749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.44.31740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kikuchi S, Shinpo K, Takeuchi M, et al. Glycation—a sweet tempter for neuronal death. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2003;41:306–323. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(02)00273-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stitt AW. Advanced glycation: an important pathological event in diabetic and age related ocular disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:746–753. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.6.746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takeuchi M, Bucala R, Suzuki T, et al. Neurotoxicity of advanced glycation end-products for cultured cortical neurons. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2000;59:1094–1105. doi: 10.1093/jnen/59.12.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hammes HP, Alt A, Niwa T, et al. Differential accumulation of advanced glycation end products in the course of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetologia. 1999;42:728–736. doi: 10.1007/s001250051221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amano S, Kaji Y, Oshika T, et al. Advanced glycation end products in human optic nerve head. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:52–55. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stitt AW, Bhaduri T, McMullen CB, Gardiner TA, Archer DB. Advanced glycation end products induce blood-retinal barrier dysfunction in normoglycemic rats. Mol Cell Biol Res Commun. 2000;3:380–388. doi: 10.1006/mcbr.2000.0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Treins C, Giorgetti-Peraldi S, Murdaca J, Van Obberghen E. Regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor expression by advanced glycation end products. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:43836–43841. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106534200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soulis T, Thallas V, Youssef S, et al. Advanced glycation end products and their receptors co-localise in rat organs susceptible to diabetic microvascular injury. Diabetologia. 1997;40:619–628. doi: 10.1007/s001250050725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barile GR, Pachydaki SI, Tari SR, et al. The RAGE axis in early diabetic retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:2916–2924. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ino-ue M, Ohgiya N, Yamamoto M. Effect of aminoguanidine on optic nerve involvement in experimental diabetic rats. Brain Res. 1998;800:319–322. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00512-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stitt A, Gardiner TA, Alderson NL, et al. The AGE inhibitor pyridoxamine inhibits development of retinopathy in experimental diabetes. Diabetes. 2002;51:2826–2832. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.9.2826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gardiner TA, Anderson HR, Stitt AW. Inhibition of advanced glycation end-products protects against retinal capillary basement membrane expansion during long-term diabetes. J Pathol. 2003;201:328–333. doi: 10.1002/path.1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hammes HP, Du X, Edelstein D, et al. Benfotiamine blocks three major pathways of hyperglycemic damage and prevents experimental diabetic retinopathy. Nat Med. 2003;9:294–299. doi: 10.1038/nm834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Howes KA, Liu Y, Dunaief JL, et al. Receptor for advanced glycation end products and age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:3713–3720. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andreassen TT, Seyer-Hansen K, Bailey AJ. Thermal stability, mechanical properties and reducible cross-links of rat tail tendon in experimental diabetes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1981;677:313–317. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(81)90101-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vlassara H, Bucala R, Striker L. Pathogenic effects of advanced glycosylation: biochemical, biologic, and clinical implications for diabetes and aging. Lab Invest. 1994;70:138–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Winlove CP, Parker KH, Avery NC, Bailey AJ. Interactions of elastin and aorta with sugars in vitro and their effects on biochemical and physical properties. Diabetologia. 1996;39:1131–1139. doi: 10.1007/BF02658498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bruel A, Oxlund H. Changes in biomechanical properties, composition of collagen and elastin, and advanced glycation end products of the rat aorta in relation to age. Atherosclerosis. 1996;127:155–165. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(96)05947-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reiser KM. Nonenzymatic glycation of collagen in aging and diabetes. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1998;218:23–37. doi: 10.3181/00379727-218-44264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hernandez MR, Luo XX, Andrzejewska W, Neufeld AH. Age-related changes in the extracellular matrix of the human optic nerve head. Am J Ophthalmol. 1989;107:476–484. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(89)90491-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Albon J, Purslow PP, Karwatowski WS, Easty DL. Age related compliance of the lamina cribrosa in human eyes. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:318–323. doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.3.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Albon J, Karwatowski WS, Avery N, Easty DL, Duance VC. Changes in the collagenous matrix of the aging human lamina cribrosa. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995;79:368–375. doi: 10.1136/bjo.79.4.368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnson EC, Morrison JC, Farrell S, Deppmeier L, Moore CG, McGinty MR. The effect of chronically elevated intraocular pressure on the rat optic nerve head extracellular matrix. Exp Eye Res. 1996;62:663–674. doi: 10.1006/exer.1996.0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hernandez MR. The optic nerve head in glaucoma: role of astrocytes in tissue remodeling. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2000;19:297–321. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(99)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tezel G, Trinkaus K, Wax MB. Alterations in the morphology of lamina cribrosa pores in glaucomatous eyes. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88:251–256. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2003.019281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Quigley HA, Hohman RM, Addicks EM, Massof RW, Green WR. Morphologic changes in the lamina cribrosa correlated with neural loss in open-angle glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1983;95:673–691. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(83)90389-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burgoyne CF, Downs JC, Bellezza AJ, Suh JK, Hart RT. The optic nerve head as a biomechanical structure: a new paradigm for understanding the role of IOP-related stress and strain in the pathophysiology of glaucomatous optic nerve head damage. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2005;24:39–73. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sasaki N, Toki S, Chowei H, et al. Immunohistochemical distribution of the receptor for advanced glycation end products in neurons and astrocytes in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. 2001;888:256–262. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ma L, Carter RJ, Morton AJ, Nicholson LF. RAGE is expressed in pyramidal cells of the hippocampus following moderate hypoxicischemic brain injury in rats. Brain Res. 2003;966:167–174. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)04149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tezel G, Hernandez MR, Wax MB. In vitro evaluation of reactive astrocyte migration, a component of tissue remodeling in glaucomatous optic nerve head. Glia. 2001;34:178–189. doi: 10.1002/glia.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tezel G, Wax MB. Increased production of tumor necrosis factor-alpha by glial cells exposed to simulated ischemia or elevated hydrostatic pressure induces apoptosis in cocultured retinal ganglion cells. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8693–8700. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-23-08693.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tezel G, Wax MB. Glial modulation of retinal ganglion cell death in glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2003;12:63–68. doi: 10.1097/00061198-200302000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Neufeld AH, Hernandez MR, Gonzalez M. Nitric oxide synthase in the human glaucomatous optic nerve head. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115:497–503. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1997.01100150499009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang J, Yang P, Tezel G, Patil RV, Hernandez MR, Wax MB. Induction of HLA-DR expression in human lamina cribrosa astrocytes by cytokines and simulated ischemia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:365–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reichelt W, Pannicke T, Biedermann B, Francke M, Faude F. Comparison between functional characteristics of healthy and pathological human retinal Muller glial cells. Surv Ophthalmol. 1997;42 suppl 1:S105–S117. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(97)80033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harada T, Harada C, Watanabe M, et al. Functions of the two glutamate transporters GLAST and GLT-1 in the retina. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:4663–4666. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kawasaki A, Otori Y, Barnstable CJ. Muller cell protection of rat retinal ganglion cells from glutamate and nitric oxide neurotoxicity. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:3444–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Naskar R, Vorwerk CK, Dreyer EB. Concurrent downregulation of a glutamate transporter and receptor in glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:1940–1944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martin KR, Levkovitch-Verbin H, Valenta D, Baumrind L, Pease ME, Quigley HA. Retinal glutamate transporter changes in experimental glaucoma and after optic nerve transection in the rat. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:2236–2243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tezel G, Wax MB. The immune system and glaucoma. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2004;15:80–84. doi: 10.1097/00055735-200404000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Glomb MA, Monnier VM. Mechanism of protein modification by glyoxal and glycolaldehyde, reactive intermediates of the Maillard reaction. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:10017–10026. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.17.10017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Takeuchi M, Makita Z, Bucala R, Suzuki T, Koike T, Kameda Y. Immunological evidence that non-carboxymethyllysine advanced glycation end-products are produced from short chain sugars and dicarbonyl compounds in vivo. Mol Med. 2000;6:114–125. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Choei H, Sasaki N, Takeuchi M, et al. Glyceraldehyde-derived advanced glycation end products in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2004;108:189–193. doi: 10.1007/s00401-004-0871-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ahmed N, Thornalley PJ, Dawczynski J, et al. Methylglyoxal-derived hydroimidazolone advanced glycation end-products of human lens proteins. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:5287–5292. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yao D, Taguchi T, Matsumura T, et al. Methylglyoxal modification of mSin3A links glycolysis to angiopoietin-2 transcription. Cell. 2006;124:275–286. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Spoerl E, Boehm AG, Pillunat LE. The influence of various substances on the biomechanical behavior of lamina cribrosa and peripapillary sclera. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:1286–1290. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hyslop PA, Hinshaw DB, Halsey WA, Jr, et al. Mechanisms of oxidant-mediated cell injury: the glycolytic and mitochondrial pathways of ADP phosphorylation are major intracellular targets inactivated by hydrogen peroxide. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:1665–1675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]