Abstract

Recent advances in immunological and genetic research in coeliac disease provide new and complementary insights into the immune response driving this chronic intestinal inflammatory disorder. Both approaches confirm the central importance of T cell-mediated immune responses to disease pathogenesis and have further begun to highlight other relevant components of the mucosal immune system, including innate immunity and the control of lymphocyte trafficking to the mucosa. In the last year, the first genome wide association study in celiac disease led to the identification of multiple new risk variants. These risk regions implicate genes involved in the immune system. Overlap with autoimmune diseases is striking with several of these regions being shown to confer susceptibility to other chronic immune-mediated diseases, particularly type 1 diabetes.

Keywords: autoimmune, coeliac, genetics, immunogenetics, genome-wide association

Introduction

Coeliac disease is a common intestinal inflammatory condition with prevalence estimates of 0·5–1% in populations of European ancestry [1]. Dietary prolamins (storage proteins in grain) from wheat, rye and barley trigger inflammation in the small intestine in susceptible individuals. Heritable genetic variation is a major determinant of this susceptibility, with a greater genetic contribution than for many common complex diseases. Until very recently, human leucocyte antigen DQ (HLA-DQ) gene variants have dominated our understanding of this genetic susceptibility and their identification has led to an immunological appreciation of how DQ heterodimers present gluten epitopes and drive T cell reactivity in coeliac disease. The identification of non-HLA susceptibility genes has accelerated dramatically in the past year, following the first genome-wide association study (GWAS) in coeliac disease. This study and a follow-up identified at least eight new genomic regions with robust levels of disease association [2,3]. Seven of these regions harbour genes with known immune functions and many are also implicated in conferring susceptibility to other autoimmune diseases.

This review is a synthesis of our current understanding of the genetics and immunology of coeliac disease. Major advances have been achieved in coeliac disease, in part because the antigen is well defined (cereal gluten), target organ (small intestine) samples are readily obtained and a strong genetic component to susceptibility has enabled disease gene identification. These advances have many general relevant findings for other human chronic immune-mediated diseases.

Epidemiology

Serological screening of populations in Europe and regions with a high proportion of European descendents (North and South America, Australasia) suggests a coeliac disease prevalence of approximately 0·5–1% in adults [1,4]. More limited data from North Africa and South-west Asia suggest a similar high prevalence of coeliac disease in these areas [5]. In central Africa and the Far East there have been no large seroprevalence studies, but overt coeliac disease is extremely rare [6–[8]. A study from Burkina Faso screened 600 individuals, all of whom ate wheat, but found no individuals with positive coeliac serology. Furthermore, no individuals carried HLA-DQ2 and only one HLA-DQ8 [9]. The Sawahari population of North Africa have the highest reported prevalence of coeliac disease worldwide (5·4%) mirrored by a very high carriage of the coeliac susceptibility marker HLA DQ2, whereas the prevalence of HLA DQ2 is very low in the Far East [10,11]. Genetic differences across populations (particularly in HLA types) clearly contribute to the different observed population prevalences.

Grain consumption also broadly parallels coeliac prevalence, being low in the Far East and sub-Saharan Africa [11]. Furthermore, there is some evidence that the dose of gluten, particularly in early childhood, may be an important determinant of lifetime susceptibility. Countries in which infant gluten consumption is low (Denmark, Estonia, Finland) report a lower infant (and adult) incidence of coeliac disease than countries with a high infant gluten consumption (Sweden) [12,13].

Adult coeliac disease prevalence has been increasing over the last few decades [1]. Improved clinical ascertainment contributes (especially in the United States), although some studies suggest a true increase in seroprevalence [14]. Similar increases in prevalence have occurred in other chronic immune-mediated diseases, particularly type 1 diabetes, implicating recent changes in shared environmental factors [15]. These factors remain unknown, although interest has focused logically upon exposures occurring in early childhood, which might be critical in determining lifetime autoimmune disease risk. In coeliac disease, onset can occur at any age but the peak incidence is between 9 and 24 months, following the introduction of gluten into the diet [1]. Breast feeding during gluten introduction has been shown to reduce susceptibility, suggesting that tolerance to gluten can be influenced by factors in breast milk [16]. Tolerance to gluten might also be influenced by the context in which it is encountered by the mucosal immune system in early life. Childhood intestinal infections have been proposed as a factor that could promote loss of tolerance to gluten, possibly because of disrupted intestinal epithelial barrier function. Furthermore, inflammation up-regulates tissue transglutaminase (tTG), a key enzyme in coeliac disease required for the generation of immunogenic epitopes from gluten [17]. There are no animal models of coeliac disease to test this hypothesis and direct evidence for the role of intestinal infections is lacking. However, epidemiological studies have shown that coeliac disease is more common in children born in summer months, possibly because of the higher incidence of viral enteritis in winter months when these children start eating gluten [18] Case–control studies have also suggested that increased exposure to infant enteral infections may confer modest increased susceptibility [odds ratios (ORs) of 1·4–1·5] [19,20]. Finally, one prospective study measured episodes of rotavirus infection by serology and found a modest increase in coeliac autoantibody incidence in infants exposed to multiple infections [21].

Although the development of coeliac disease has been considered a permanent gluten-sensitive enteropathy, needing lifelong treatment, recent reports suggest that some children can resolve this intolerance at least partially when kept on a gluten-containing diet [22,23]. These children may have normal small intestinal histology in adulthood, suggesting that coeliac disease can remit or enter a quiescent phase, with immunological tolerance to gluten, following initial clinically overt disease. How frequently this phenomenon occurs is unclear; much more research in this area is necessary – including whether such remission might be induced therapeutically.

Evidence for genetic susceptibility

Closely related individuals with coeliac disease have a higher disease concordance than unrelated individuals (familial clustering). Monozygotic twins have disease concordance rates of 75% compared with 11% in dizygotic twins [24]. Sibling relative risk ratios (λs) provide the best estimates of familial clustering, controlling for population prevalence. For coeliac disease, sibling relative risk ratios of between 20 and 60 have been reported [25–[27]. This is higher than for most other polygenic immune-mediated disorders such as type 1 diabetes (λs = 15), rheumatoid arthritis (λs = 2–8) or Crohn's disease (λs = 27) [28].

Immunogenetics of the HLA

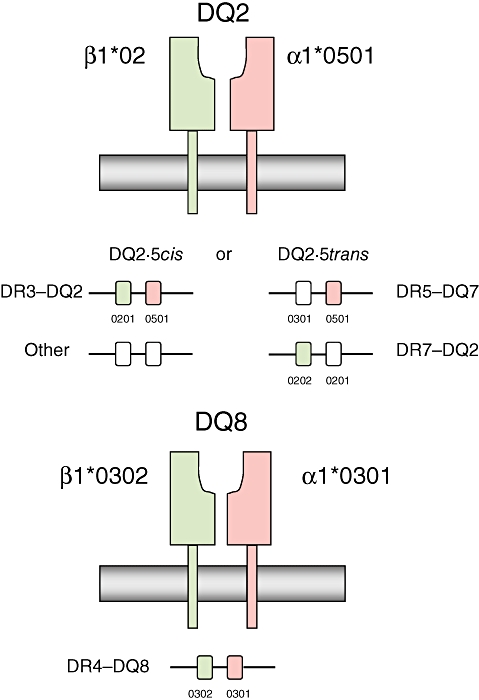

The HLA complex is a highly polymorphic 4 Mb region on chromosome 6p21, containing more than 200 genes and over 3000 known alleles [29]. HLA class II genes (DP, DQ and DR) are involved in exogenous peptide antigen presentation to T cells. The first reports of association with coeliac disease used serological methods to identify B8 and later DR3 as susceptibility variants [30,31]. The B8 and DR3 molecules are encoded by alleles on a 6Mb extended haplotype (A1-B8-DR3-DQ2) present in 10% of northern Europeans [32]. Interestingly, other autoimmune diseases are associated with this haplotype, including type 1 diabetes and autoimmune thyroid disease. Subsequent studies have pinpointed DQ2 and in particular the combination of HLA-DQA1*0501 and DQB1*0201 encoding the HLA-DQ2 (α1*0501,β1*0201) heterodimer as the cause of the coeliac disease association [33]. This heterodimer can be encoded both in cis (by alleles on the same haplotype) or in trans(one subunit each from paternal and maternal haplotypes) (Table 1, Fig. 1). Moreover several studies show that homozygosity for the cishaplotype or possessing a second DQB1*02 allele increases coeliac disease susceptibility further [37,38]. The second B1*02 allele is usually inherited on the DR7-DQ2 haplotype carrying DQB1*0202 and DQA1*0201 (DQ2·2), but possession of this haplotype alone does not confer coeliac susceptibility (Table 1).

Table 1.

Classical human leucocyte antigen (HLA) DQ genotypes associated with coeliac disease and gene dosage effects.

| Serological type | Chromosome copy | DQ2 genotype | DQ type | Coeliac susceptibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DR3–DQ2/ | i | DQA1*0501–DQB1*0201/ | DQ2·5 cishomozygote | High |

| DR3–DQ2 | ii | DQA1*0501–DQB1*0201 | ||

| DR3–DQ2/ | i | DQA1*0501–DQB1*0201/ | DQ2·5 cis + DQ2·2 | High |

| DR7–DQ2 | ii | DQA1*0201–DQB1*0202 | ||

| DR3–DQ2/ | i | DQA1*0501–DQB1*0201/ | DQ2·5 cis heterozygote | Moderate |

| other | ii | other | ||

| DR5–DQ7/ | i | DQA1*0505–DQB1*0301/ | DQ2·5trans | Moderate |

| DR7–DQ2 | ii | DQA1*0201–DQB1*0202 | ||

| DR7–DQ2/ | i | DQA1*0201–DQB1*0202/ | DQ2·2 | Nil |

| other | ii | other | ||

| DR4–DQ8/ | i | DQA1*0301–DQB1*0302/ | DQ8 | Moderate |

| other | ii | other |

Fig. 1.

Classical haplotype combinations encoding the human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-DQ2 and -DQ8 heterodimers. Adapted from Sollid [36]. HLA proteins at the cell surface, and structure of the protein encoding DNA region, are shown.

An explanation for the HLA gene-dosage effect was provided by an in vitrostudy demonstrating that the level of proliferation and cytokine responses of gluten-reactive T cell clones depends on DQ type and gene dose [35]. Vader et al. used allogeneic peripheral blood mononuclear cells to present gluten epitopes to gluten-specific T cell clones and showed that T cell responses were highest for DQ2·5 homozygotes, intermediate for DQ2·5/2·2, lower for DQ2·5/x heterozygotes and lowest for DQ2·2. Thus DQ2·2 in the presence of DQ2·5 can augment T cell stimulation through DQ2-mediated antigen presentation. DQ2·2 alone, which is not associated with coeliac disease, was able to elicit strong T cell responses but only through presentation of a restricted subset of the gluten epitopes tested. This suggests that the DQ2 contribution to coeliac disease depends upon its ability to present multiple closely related gluten epitopes – the ability of DQ2·2 molecules to present a small subset of epitopes exerts effects too weak to cause disease.

The HLA-DQ2·5 molecule encoded either in cisor in trans is present in around 90% of coeliac patients of northern European origin [39]. The majority of the remainder carry HLA-DQ8 (genetically DQA1*03, DQB1*0302) [40,41]. A large European collaborative study found that of those that lack both DQ2 and DQ8, only four of 1008 coeliac patients had neither the alpha nor beta chain of the DQ2 heterodimer [41] This has led to a model of coeliac disease pathogenesis in which HLA DQ2/8 is necessary but not sufficient, as HLA-DQ2 is present in 30% of healthy Caucasian populations [39]. The proportion of sibling relative risk attributable to known HLA variants is estimated to be between 30 and 40%, indicating that non-HLA DQ variants contribute to coeliac disease susceptibility [3,25,26]. Within the HLA complex itself there are many other genes with immune functions which might also contribute to the observed association signal. However, the high linkage disequilibrium (LD) that exists between genetic variants in this region is an obstacle to teasing out the true causal associations [42]. Two studies that have controlled for LD to DQ have not found evidence of additional HLA risk variants, although statistical power was limited [41,43].

The genetic loci harbouring variants that account for the remaining 70% or so of unexplained familial clustering in coeliac disease are the targets of gene finding studies. Two complementary approaches have been used: genetic linkage and association studies (Table 2).

Table 2.

Gene-finding approaches in coeliac disease.

| Study type | Method | Advantages | Disadvantages | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linkage studies | Test co-segregation of genetic markers with disease phenotype in affected relatives to establish broad regions of genome within which causal variants reside | Able to detect rare variants, and structural variants, if highly penetrant | Low power to detect weakly penetrant alleles | 5q31–33 [44,45] 19p13.1 (?MYO9B) [46] |

| Low genomic resolution | ||||

| Require large numbers of affected families | ||||

| Candidate gene association studies | Compare frequencies of variants in candidate genes chosen on biological grounds or from knowledge of linkage regions | May pinpoint genes from regions of linkage | Low power to detect rare variants | CTLA4 [47] |

| Greater power to detect weakly penetrant alleles | Historically generated many false positives | |||

| Genome-wide association studies | Compare frequencies of ∼105 single nucleotide polymorphisms distributed throughout the genome between cases and controls | High resolution: able to pinpoint small region of genome | Low power to detect rare alleles | IL2–IL21 region, RGS1, IL18RAP, SH2B3 [2,3] |

| Power to detect weakly penetrant alleles | Low power to detect structural variants | |||

| Expensive |

In general, findings from linkage and candidate gene studies in coeliac disease, with the exception of the HLA region, have not been replicated consistently. Linkageregions identified include 5q31–33 and 19p13.1, although these remain tentative and lack robust replication [44,46]. MYO9B, encoding the myosin IXB protein, has emerged as a candidate gene from further studies of the 19p13.1 linkage region, although replication of this finding has been inconsistent [48–[51]. A candidate gene approach identified an association in the CTLA4 region, a gene on chromosome 2q encoding cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 [47]. CTLA-4 is expressed on T cells and is a receptor for B7 molecules that inhibit T cell activation. Replication studies of the CTLA4 association have been somewhat inconclusive [34]. Therefore, prior to the first GWAS in 2007, despite intensive efforts, no genetic susceptibility loci other than HLA DQ had been definitively identified.

Human leucocyte antigen-DQ-restricted T cells

Coeliac disease has multi-systemic features, but the predominant lesion mirrors the exposure of the small intestine to dietary gluten. Several lines of evidence implicate a T cell-orchestrated immunopathogenesis. Upon gluten challenge of small intestinal biopsies from treated (i.e. on a gluten-free diet) coeliac disease patients, infiltration of the lamina propria (LP) with (predominantly CD4+ αβ) T cells occurs within hours, followed by crypt hyperplasia and villous atrophy [52]. This temporal sequence alludes to the central importance of T cells in coeliac disease. In untreated disease T helper 1 (Th1) cytokines are highly expressed in the intestinal mucosa, particularly interferon (IFN)-γ, supporting the concept of a Th1-driven T cell-mediated disorder [53]. Analysis of LP infiltrating lymphocytes confirms not only IFN-γ expression in a high proportion, but also expression of the Th1 transcription factor T-bet [54]. The Th1 bias of CD4+ T cells probably depends less on interleukin (IL)-12 in coeliac disease than in other inflammatory conditions. IL-12 is present in very low levels in coeliac disease mucosa [55,56] although other Th1-inducing cytokines (IL-18 and IFN-α) are increased [56–[58]. Dendritic cells isolated from the intestinal mucosa in coeliac disease also express increased levels of IL-18 and IFN-α but lack IL12p40 [55]. Immunophenotyping of DQ2+ antigen-presenting cells in treated versus untreated coeliac disease intestinal biopsies suggest a large increase in CD11+ myeloid dendritic cells in active disease [55,59]. These cells efficiently present gluten peptides to CD4 T cells inducing proliferation and IFN-γ responses [59].

The gluten-responsiveness of CD4 T cells in coeliac disease was first demonstrated in T cell lines and clones isolated from intestinal mucosa [60,61]. These cells are not found in non-coeliac DQ2- or DQ8- controls but in coeliac disease proliferate and secrete IFN-γ when co-cultured with antigen-presenting cells in the presence of a variety of peptides derived from gluten. These studies show that gluten peptides activate T cells in the intestinal mucosa exclusively through presentation by the disease-associated DQ2- or DQ8-αβ heterodimers [60,61].

Gluten epitopes and the role of tTG

While there is heterogeneity between patients with coeliac disease in the gluten epitopes to which their T cells respond, some epitopes are immunodominant and elicit T cell activation in almost all coeliac individuals [62,63]. These responses have been demonstrated both in intestine-derived T cell lines or clones and in primary T cells isolated from peripheral blood following gluten challenge, supporting their contribution to disease in vivo [63,64]. T cell epitopes identified to date are derived from various gluten proteins, including α-gliadins, γ-gliadins and low molecular weight glutenins [62,65–[67]. The peptide-binding groove structure of DQ2 and DQ8 dimers has been characterized and some of the constraints this places on selection of epitopes for binding DQ2 or DQ8 are known [68]. Both DQ2 and DQ8 dimers have preferences for negatively charged residues at key positions in the core peptide-binding groove [69–[71]. Negatively charged residues are uncommon in gluten peptide sequences, but deamidation of glutamine residues to negatively charged glutamate can increase drastically the immunogenicity of gliadin peptides [67]. X-ray crystallographic analysis of DQ2-peptide interactions supports the importance of selective deamidation of glutamine residues in favouring peptide binding for gluten peptides [72,73]. tTG, an enzyme first linked to coeliac disease by the discovery that it is the target of autoantibodies used in diagnosis, can catalyse this deamidation [74,75]. tTG is likely to perform this function in vivo, as it highly expressed in the small intestine, up-regulated in inflammation and favours deamidation of glutamine residues rather than transamidation under the acidic conditions which exist in the proximal small intestine [76]. More recently, a direct pathogenic contribution of tTG antibodies has been proposed, with in vitrostudies suggesting that these antibodies can both activate monocytes by binding Toll-like receptor 4 and inhibit angiogenesis by altering tTG function [77,78]. Such effects, if substantiated, may be a mechanism driving extra-intestinal manifestations in coeliac disease, because tTG autoantibody deposits have been observed in affected organs (e.g. liver, brain) remote from the site of gluten exposure in the intestine [79,80].

A further important characteristic of gluten epitopes is a high proline content [65]. This reflects the inability of human digestive enzymes to break amide bonds between proline residues and adjacent bulky hydrophobic amino acids, such that gluten peptides can reach the intestinal mucosa intact [65,81].

The innate immune system in coeliac disease

Both in vivostudies and studies of gluten challenge of intestinal biopsies have shown that effects on the mucosa begin within a few hours [82–[84]. This rapid onset cannot be accounted for easily by the (presumably slower) mechanism of gluten peptide presentation to CD4+ T lymphocytes and has led to interest in a role for the innate immune system in coeliac disease. Further support for this hypothesis came from the observation that some gliadin peptides (p31–p43 α gliadin) that do not elicit classical DQ-restricted CD4+ T cell responses can exert toxic effects on the epithelium [85]. IL-15, which is highly expressed in LP macrophages and intestinal epithelium, appears to be a crucial intermediary of these effects. IL-15 enhances intra-epithelial lymphocyte (IEL) proliferation, cytotoxicity (versus epithelial cells) and cytokine release, with increases in IFN-γ and granzyme B [86,87] Furthermore, exogenous application of IL-15 partly reproduces the effects of gliadin challenge, whereas anti-IL-15 antibodies abrogate the effects of gliadin [87].

A feature of coeliac disease is expansion of the IEL population, as well as an inflammatory cell infiltrate deeper in the intestinal LP. The IELs in coeliac disease comprise increased populations of both CD8+ TCRαβ lymphocytes as well as γδ (CD4-CD8- or CD8+) T cells that can induce enterocyte apoptosis directly [88]. Some intra-epithelial T cells have been shown to demonstrate aberrant expression of natural killer (NK) lineage receptors and can perform NK-like functions including T cell receptor-independent killing of enterocytes in active coeliac disease [88–[90]. These effects are stimulated by gluten peptides including p31–43 α-gliadin and include the induction of expression of the cell surface stress molecule major histocompatibility complex class I chain related gene A on enterocytes and its receptor NKG2D on IELs [90]. Mechanistic details of the recognition of these apparently ‘innate’ peptides are unclear.

Genome-wide Association Studies in coeliac disease

Current models of complex disease estimate that that the majority of genetic variation contributing to disease susceptibility is carried by multiple variants of weak effect size. Variants with modest effects are below the threshold of detection of even large linkage studies and candidate gene association studies have rarely proved successful as a primary approach to gene finding. GWAS offer major advantages both in power to detect variants with modest effects and in defining smaller genomic regions in which causal variants reside [91]. Nevertheless, the power of GWAS depends upon many variables including sample size, number of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) tested, ORs conferred by associated SNPs, model of inheritance (e.g. dominant, recessive) and the minor allele frequency. The Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium GWAS estimated power of 80% to detect SNPs with minor allele frequencies (MAFs) > 5% and OR = 1·5 using 2000 cases and 3000 controls [92]. Rare alleles with important effects may be missed, even in large studies, particularly as more than half of SNPs in the human genome are estimated to have MAFs < 5% [93]. Furthermore, structural variation, which may also account for a large proportion of human genetic variation, is not well captured by the first generation SNP arrays used in recent GWAS, which tag mainly common haplotypes [94,95].

The first GWAS in coeliac disease tested over 300 000 SNPs in 778 UK coeliac cases and 1422 controls [2]. This study confirmed the known association of coeliac disease with the HLA region, with the strongest association at a SNP tagging HLA DQ2·5 cis. There was weak evidence of association in the previously reported CD28–CTLA4–ICOSregion (P = 0·007), but not the MYO9B region.

New coeliac disease genes

IL2–IL21 region

Outside HLA, the strongest marker from the recent UK coeliac disease GWAS mapped to chromosome 4q27 (P = 2 × 10−7), a finding replicated in further UK, Dutch and Irish cohorts [3]. The associated SNP tags a ∼700 kb LD block encompassing four genes (ADAD1, KIAA1109, IL2and IL21), such that variants in any of these genes could explain the genetic association. This region is emerging from other studies as a common autoimmune disease locus (see below). The most compelling biological candidates within the LD block are IL2and IL21.

Interleukin-2 and IL-21 are members of a cytokine family, sharing the same γ chain subunit in their receptors [96]. These cytokines have multiple and diverse roles in the immune response, posing a challenge in identifying the precise biological mechanisms relevant to coeliac disease. IL-2 has a well-defined autocrine function in stimulating T cell activation and proliferation, but can also stimulate NK cell proliferation and immunoglobulin production from B cells. This cytokine has a unique role in activation-induced cell death, a process that eliminates self-reactive T cells, and in maintenance of CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T (Treg) cells [97–[99]. In the non-obese diabetic mouse model the region syntenic to human 4q27 determines susceptibility to multiple autoimmune diseases through an IL2-dependent mechanism [100]. In this model, the murine risk variants were associated with reduced IL2 gene expression, lower proportions of CD4+ CD25+ Treg cells in mesenteric lymph nodes and impaired function of these cells [100]. It is thus possible that the IL2–IL21 region risk variants in human coeliac disease might also exert their susceptibility effects through the CD4+ CD25+ Treg cell subset, for example by impairing tolerance to gluten peptides. However, in humans, there are as yet no comparable data of the effects of variants on gene expression or function. IL21remains a candidate gene in this region and expression is known to be increased in the small intestinal mucosa in untreated coeliac disease [101]. IL-21 is secreted mainly from CD4+ T cells and has proinflammatory effects including enhancement of B, T and NK cell proliferation [102]. Anti-IL-21 antibodies in an ex-vivo intestinal biopsy culture model reduced T-bet and IFN-γ expression, suggesting that IL-21 may be important in sustaining Th1 activity in coeliac disease [101].

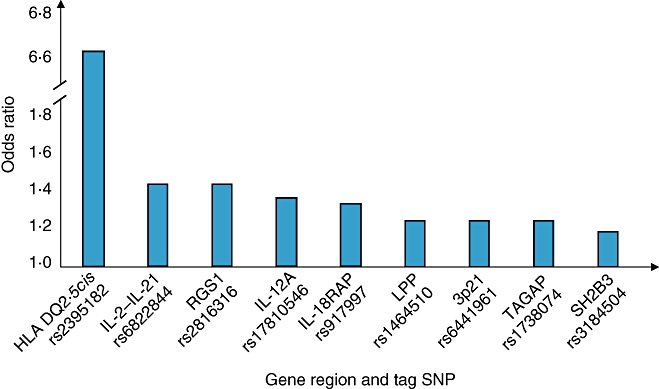

The follow-up study from the first coeliac GWAS was reported recently [3]. This tested over 1000 of the most strongly associated non-HLA SNPs from the original UK GWAS in a large independent cohort (1643 new coeliac cases and 3406 controls). The added power of this study yielded strong, genome-wide significant results (P < 5 × 10−7) for a further seven new genomic regions, six of which harbour genes with immune functions (Table 3, Fig. 2). It was estimated in this follow-up study that the newly identified variants account for only 3–4% of the genetic susceptibility of coeliac disease, suggesting that many other true associations remain undetected. Effect sizes of the SNPs on disease susceptibility are modest, in line with findings from GWAS in other complex diseases (Fig. 3) [103,104]. The allele that is more frequent in cases can confer either protective or risk effects with ORs of all detected variants between 0·7 and 1·4. Given that there are an estimated 8 million SNPs with MAF > 5% in the human genome and only 300 000 SNPs were tested in the original GWAS, in most cases associated SNPs are unlikely to be causal, but instead will show variable levels of correlation with the true causal variants. Identification of the true causal variants is a priority of further research and will depend on fine-mapping and/or deep resequencing of the regions identified. Indications from other diseases suggest that discovery of the true causal variants may lead to a significant upwards revision of both effect sizes and the estimated proportion of genetic susceptibility accounted for [103]. In the interim, the primary significance of the GWAS study findings is in providing new insights into the biological pathways relevant to the pathogenesis of coeliac disease.

Table 3.

Non-human leucocyte antigen (HLA) susceptibility loci for coeliac disease from recent Genome-Wide Association Study [2,3].

| Locus | Tag SNP with strongest association | Odds ratio (CI) | Candidate genes | Other diseases associated with the same region |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4q27 | rs6822844 | 0.71 (0.63–0.80) | IL2, IL21 | Type 1 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, Graves’ disease, psoriasis |

| 1q31 | rs2816316 | 0.71 (0.63–0.80) | RGS1 | |

| 2q11–2q12 | rs917997 | 1.27 (1.15–1.40) | IL1RL1, IL18R1, IL18RAP, SLC9A4 | Crohn's disease |

| 3p21 | rs6441961 | 1.21 (1.10–1.32) | CCR1, CCR2, CCRL2, CCR3, CCR5, XCR1 | Type 1 diabetes |

| 3q25–3q26 | rs17810546 | 1.34(1.19–1.51) | IL12A, SCHIP1 | |

| 3q28 | rs1465150 | 1.21 (1.11–1.31) | LPP | |

| 6q25 | rs1738074 | 1.21 (1.11–1.31) | TAGAP | |

| 12q24 | rs653178 | 1.19 (1.10–1.30) | SH2B3 | Type 1 diabetes |

CI, confidence interval; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

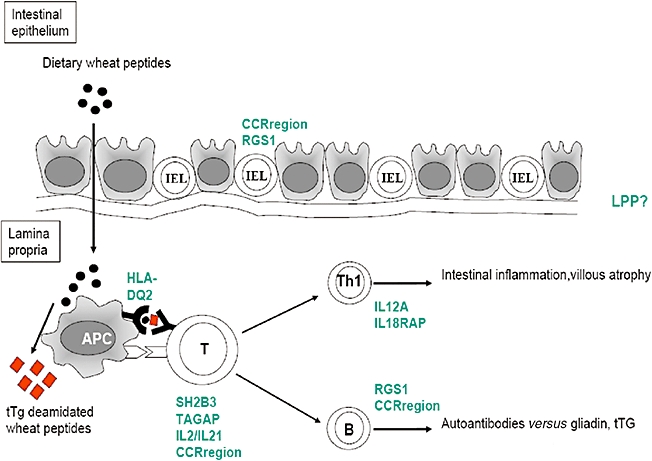

Fig. 2.

Model of gluten induced immune response in coeliac disease, and the sites of action of coeliac susceptibility genes. The most likely gene from each region is shown, although note that causality of a genetic variant in any one gene has not yet been proved.

Fig. 3.

Current estimates of effect size conferred by the coeliac disease-associated risk variants. Allelic odds ratios are shown for the best tag markers from the Genome-Wide Association Study, along with the most likely candidate gene(s) from each region. It is probable that the effect of the true causal variants, once identified, will be larger.

RGS1 region

The strongest association (P = 2·58 × 1011) outside the HLA region and IL2–IL21 was for a SNP 8 kb distal to the 5′ end of RGS1. RGS1 is of particular interest in coeliac disease because of its selective expression in the intestinal IEL compartment, but not conventional splenic or thymic T cells [3,105]. RGS1 regulates G protein signalling activity and is implicated in mice in regulating chemokine receptor signalling and B cell trafficking to lymph nodes [106].

3p21

Another strong association mapped to a chemokine receptor gene cluster on 3p21 including CCR1, CCR2, CCRL2, CCR3, CCR5and XCR1, again hinting at the importance that chemokine receptor signalling and recruitment of effector immune cells to sites of inflammation may have in coeliac disease. The disease associated genetic variants may influence these pathways subtly.

IL12A and IL18RAP

Strong association (P = 10−9) of SNPs in a 70 Kb LD block immediately 5′ of IL12Aimplicate this gene, which encodes IL12p35, the subunit that forms one-half of the IL-12 heterodimer with IL-12p40. IL-12 is expressed by antigen-presenting cells and has a broad range of biological activities, including induction of IFN-γ-secreting Th1 cells. Although coeliac disease is characterized by a strong Th1 response, surprisingly IL12p40 is not expressed in coeliac disease mucosa after gluten challenge and both IL-12p40 and IL-12p35 expression were not found to be increased in dendritic cells isolated from untreated coeliac disease mucosa [53,55]. It might well be in coeliac disease that IL-12 signalling is important at an alternative site (e.g. mesenteric lymph nodes) – attempting to make sense of these findings really highlights our limited knowledge of the primary underlying immunopathogenic mechanisms.

There is evidence for the importance of IFN-α and IL-18 in promoting a Th1 phenotype in CD4 T cells in coeliac disease (see above). IL18 transcripts are expressed very strongly in the human small intestine. In this regard, another candidate gene identified from the GWAS (IL18RAP) encodes the β chain of the IL-18 receptor. Hunt et al. showed that the coeliac disease associated SNPs correlated with IL18RAPgene expression in peripheral blood. The risk alleles, found more commonly in individuals with coeliac disease, correlated with lower levels of IL18RAPmRNA suggesting that variants reduce gene expression. This might suggest a loss of function of IL-18 receptor signalling, a puzzling finding given the up-regulation of IL-18 and strong Th1 bias in coeliac disease. Again, these findings underline the limitations of current immunological models of coeliac and other immune-mediated diseases, but also provide clues to inform the design of new functional studies.

SH2B3 region

SH2B3 is expressed in immune cells, up-regulated in coeliac mucosa and thought to function in regulation of T cell receptor, growth factor and cytokine receptor-mediated signalling [107,108]. A non-synonymous SNP (rs3184504) in SH2B3 was associated with coeliac disease in the follow-up study. The same SNP is associated with type 1 diabetes, accounting entirely for the association in the latter disease [104]. This SNP, in exon 3 of SH2B3, leads to an amino acid substitution (R262W) in the pleckstrin homology (PH) domain of the SH2B3 protein. PH domains are involved in targeting proteins to plasma membranes through binding phosphoinositides [109]. Mutations in PH domains in other proteins have been associated with disease by impairing phosphoinositide binding and membrane localization (X-linked agammaglobulinaemia) or through causing constitutive membrane association (breast, colorectal and ovarian cancers) [110,111]. Functional studies of the effects of the R262W variant are needed to determine how this impacts on the biology of coeliac disease.

TAGAP and LPP

T cell activation GTPase activating protein-TAGAP is a gene expressed in activated T cells, whose function in immune cells is not well characterized but may modulate cytoskeletal changes [112]. LPP is strongly expressed in the small intestine but the significance in relation to coeliac disease is unknown.

Some coeliac disease-associated regions also influence susceptibility to other chronic immune-mediated conditions

An unexpected finding from the recent coeliac disease genetic studies was the identification of gene regions that have been associated with other chronic immune-mediated conditions (Table 3). Coeliac disease is associated with an increased prevalence of several autoimmune conditions, including type 1 diabetes, autoimmune thyroid disease and rheumatoid arthritis [113]. Comparison of GWAS data sets of coeliac disease and autoimmune diseases implicate a novel shared disease association between coeliac disease and type 1 diabetes in the SH2B3gene, 3p21 CCRgene region and IL2–IL21 region, whereas variants in the IL18RAPregion have also been identified in Crohn's disease [92,104]. IL2–IL21variants have been associated with Graves’ disease, rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis in addition to type 1 diabetes, suggesting that this may be a common autoimmune disease locus [104,114,115]. The association of at least four independent gene regions with both type 1 diabetes and coeliac disease (HLA DQ, IL2–IL21, SH2B3and CCRregion) is particularly striking and points to shared mechanisms in the immunopathogenesis of these two conditions. These genes all have putative roles in CD4+ T cell activation or recruitment, reinforcing the central importance of this cell in both diseases. Type 1 diabetes and coeliac disease have both shown rising incidence in recent years, with tantalizing, although still inconclusive, evidence for the role of early childhood intestinal infections, particularly rotavirus [19–21,116]. Thus a model emerges in which common genetic and environmental factors might drive a shared type 1 diabetes/coeliac predisposition, with further disease-specific genes or environmental factors biasing individuals towards one or both diseases.

Therapeutic prospects arising from coeliac gene discovery

Human leucocyte antigen-DQ remains the only coeliac disease locus in which the causal variants are known and their contribution to disease pathogenesis is understood (Box 1). Identification of causal variants within the new coeliac disease regions and functional investigation of these new candidate genes is a priority for future research. Therapeutic manipulation of the pathways identified in these studies may also prove fruitful. Despite modest effect sizes of the genes identified, more profound modulation of function can have important clinical benefits. In type 2 diabetes, where genetic variants in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARG) confer modest susceptibility (OR 1·1), thiazoledinediones, which act as agonists of PPAR-γ, have significant clinical benefit [117]. A variant in the ATP-sensitive potassium channel (KCNJ11), which is the pharmacological target of another class of type 2 diabetes medication (sulphonylureas), again shows a modest susceptibility effect, with a heterozygote versus homozygote ORs of only 1·1 [118]. Perhaps the most exciting prospect, given that a safe and effective treatment for coeliac disease already exists, is the possibility that these genes may reveal pathways that can be exploited for long-lasting immunomodulation in the prevention of coeliac and other related immune-mediated conditions such as type 1 diabetes. Any such strategies must be safe, with minimal toxicity.

Box 1.

Potential immunopathogenic functions of newly identified coeliac susceptibility genes

Newly identified coeliac susceptibility gene regions implicate pathways involved in both innate and adaptive immune responses

Chemokine signalling – two gene regions (CCR region and RGS1) have known roles in chemokine signalling, suggesting that mechanisms of immune cell recruitment to the intestinal epithelium/mucosa have a significance that has not been emphasized previously in immunological models. RGS1 is expressed selectively in intra-epithelial lymphocytes, and can influence lymphocyte trafficking, possibly providing insight into why the intra-epithelial lymphocyte population is expanded in coeliac disease

T cell activation and differentiation – gluten peptide presentation via DQ2/8 activates a clinically significant CD4+ T cell response in coeliac disease, but not in non-coeliac DQ2/8+ individuals. Several of the new susceptibility genes have roles in T cell activation (IL2–IL21, TAGAP, SH2B3), Treg function (IL2) and Th1 differentiation (IL18RAP, IL12A). These gene variants may subtly influence the outcome of antigen presenting cell–T cell gluten peptide interactions, shifting the balance towards gluten-specific effector Th1 cells (as in coeliac disease) rather than tolerance to gluten (non-coeliac DQ2/8 controls)

Concluding remarks

Our understanding of the immunogenetic pathogenesis of coeliac disease is well advanced in comparison with most other chronic immune-mediated conditions. The antigen (gluten) and many of the immunodominant epitopes that drive T cell responses in coeliac disease have been identified. The role of tTG in enhancing the immunogenicity of gluten peptides by deamidation of glutamine residues is known. The major causal variants in the HLA region are identified and this has led to functional understanding of how these molecules select and present immunogenic gluten peptides. Other aspects of the mucosal immune response in coeliac disease have been characterized, including the roles of IEL and non-T cell receptor-dependent mechanisms of gluten toxicity.

Genome-wide association studies are now rapidly adding information on primary genetic predisposing factors in coeliac disease, with eight new loci now identified, seven of which contain genes influencing immune function. Thus the genetic factors are directly relevant to, and may guide further, our immunological understanding of the disease (Box 2). Several of the coeliac risk loci are also implicated in type 1 diabetes, suggesting far greater similarity in the immunopathogenesis of these conditions than suspected previously. These new loci promise to provide insights into why not all individuals with HLA-DQ2 or DQ8 develop coeliac disease and point to factors that subtly modulate T cell activation and effector cell (Th1) differentiation. The precise causal variants remain to be determined, but their identification and functional studies will, in time, provide further insights into the pathogenesis of coeliac disease and related immune-mediated conditions.

Box 2.

Future priorities for coeliac disease immunogenetic research

-

Identification of additional susceptibility loci

Extending current GWAS with larger sample sizes and study meta-analysis

Development of high throughput methods to detect structural variants

-

Identification of causal variants in susceptibility regions

Fine-mapping of associations with high-density SNPs

Resequencing of involved areas to identify rare and causal variants

Use of biological information to implicate causality (e.g. SNP/gene expression correlation studies, gene knockdown studies)

Detailed functional studies of new coeliac gene variants to understand molecular and physiological roles in disease pathogenesis

Development of an animal model to test immunological hypotheses, including initial responses to gluten and factors determining tolerance

Development of new diagnostic tests

Use of newly defined targets to develop therapeutic strategies

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Cisca Wijmenga for the concept of Figure 2. Dr P. C. Dubois holds an MRC Clinical Research Training Fellowship.

References

- 1.van Heel DA, West J. Recent advances in coeliac disease. Gut. 2006;55:1037–46. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.075119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Heel DA, Franke L, Hunt KA, et al. A genome-wide association study for celiac disease identifies risk variants in the region harboring IL2 and IL21. Nat Genet. 2007;39:827–9. doi: 10.1038/ng2058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hunt KA, Zhernakova A, Turner G, et al. Newly identified genetic risk variants for celiac disease related to the immune response. Nat Genet. 2008 doi: 10.1038/ng.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.West J, Logan RF, Hill PG, et al. Seroprevalence, correlates, and characteristics of undetected coeliac disease in England. Gut. 2003;52:960–5. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.7.960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Accomando S, Cataldo F. The global village of celiac disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2004;36:492–8. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2004.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freeman HJ. Biopsy-defined adult celiac disease in Asian-Canadians. Can J Gastroenterol. 2003;17:433–6. doi: 10.1155/2003/789139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonamico M, Mariani P, Triglione P, et al. Celiac disease in two sisters with a mother from Cape Verde Island, Africa: a clinical and genetic study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1994;18:96–9. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199401000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fasano A, Berti I, Gerarduzzi T, et al. Prevalence of celiac disease in at-risk and not-at-risk groups in the United States: a large multicenter study. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:286–92. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.3.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cataldo F, Lio D, Simpore J, Musumeci S. Consumption of wheat foodstuffs not a risk for celiac disease occurrence in Burkina Faso. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002;35:233–4. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200208000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Catassi C, Doloretta Macis M, Ratsch IM, De Virgiliis S, Cucca F. The distribution of DQ genes in the Saharawi population provides only a partial explanation for the high celiac disease prevalence. Tissue Antigens. 2001;58:402–6. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2001.580609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fasano A, Catassi C. Current approaches to diagnosis and treatment of celiac disease: an evolving spectrum. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:636–51. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.22123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weile B, Cavell B, Nivenius K, Krasilnikoff PA. Striking differences in the incidence of childhood celiac disease between Denmark and Sweden: a plausible explanation. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1995;21:64–8. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199507000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitt K, Uibo O. Low cereal intake in Estonian infants: the possible explanation for the low frequency of coeliac disease in Estonia. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1998;52:85–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lohi S, Mustalahti K, Kaukinen K, et al. Increasing prevalence of coeliac disease over time. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1217–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.EURODIAB ACE Study Group. Variation and trends in incidence of childhood diabetes in Europe. Lancet. 2000;355:873–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ivarsson A, Hernell O, Stenlund H, Persson LA. Breast-feeding protects against celiac disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75:914–21. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/75.5.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ientile R, Caccamo D, Griffin M. Tissue transglutaminase and the stress response. Amino Acids. 2007;33:385–94. doi: 10.1007/s00726-007-0517-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ivarsson A, Hernell O, Nystrom L, Persson LA. Children born in the summer have increased risk for coeliac disease. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2003;57:36–9. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.1.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ivarsson A. The Swedish epidemic of coeliac disease explored using an epidemiological approach – some lessons to be learnt. Best Pract Res. 2005;19:425–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sandberg-Bennich S, Dahlquist G, Kallen B. Coeliac disease is associated with intrauterine growth and neonatal infections. Acta Paediatr. 2002;91:30–3. doi: 10.1080/080352502753457905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stene LC, Honeyman MC, Hoffenberg EJ, et al. Rotavirus infection frequency and risk of celiac disease autoimmunity in early childhood: a longitudinal study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2333–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matysiak-Budnik T, Malamut G, de Serre NP, et al. Long-term follow-up of 61 coeliac patients diagnosed in childhood: evolution toward latency is possible on a normal diet. Gut. 2007;56:1379–86. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.100511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simell S, Hoppu S, Hekkala A, et al. Fate of five celiac disease-associated antibodies during normal diet in genetically at-risk children observed from birth in a natural history study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2026–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greco L, Romino R, Coto I, et al. The first large population based twin study of coeliac disease. Gut. 2002;50:624–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.5.624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petronzelli F, Bonamico M, Ferrante P, et al. Genetic contribution of the HLA region to the familial clustering of coeliac disease. Ann Hum Genet. 1997;61:307–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-1809.1997.6140307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bevan S, Popat S, Braegger CP, et al. Contribution of the MHC region to the familial risk of coeliac disease. J Med Genet. 1999;36:687–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Risch N. Assessing the role of HLA-linked and unlinked determinants of disease. Am J Hum Genet. 1987;40:1–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewis CM, Whitwell SC, Forbes A, Sanderson J, Mathew CG, Marteau TM. Estimating risks of common complex diseases across genetic and environmental factors: the example of Crohn disease. J Med Genet. 2007;44:689–94. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.051672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robinson J, Waller MJ, Parham P, et al. IMGT/HLA and IMGT/MHC: sequence databases for the study of the major histocompatibility complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:311–14. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Falchuk ZM, Rogentine GN, Strober W. Predominance of histocompatibility antigen HL-A8 in patients with gluten-sensitive enteropathy. J Clin Invest. 1972;51:1602–5. doi: 10.1172/JCI106958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keuning JJ, Pena AS, van Leeuwen A, van Hooff JP, van Rood JJ. HLA-DW3 associated with coeliac disease. Lancet. 1976;1:506–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(76)90294-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Price P, Witt C, Allcock R, et al. The genetic basis for the association of the 8.1 ancestral haplotype (A1, B8, DR3) with multiple immunopathological diseases. Immunol Rev. 1999;167:257–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1999.tb01398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tosi R, Vismara D, Tanigaki N, et al. Evidence that celiac disease is primarily associated with a DC locus allelic specificity. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1983;28:395–404. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(83)90106-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Heel DA, Hunt K, Greco L, Wijmenga C. Genetics in coeliac disease. Best Pract Res. 2005;19:323–39. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vader W, Stepniak D, Kooy Y, et al. The HLA-DQ2 gene dose effect in celiac disease is directly related to the magnitude and breadth of gluten-specific T cell responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:12390–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2135229100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sollid LM. Molecular basis of celiac disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:53–81. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Louka AS, Nilsson S, Olsson M, et al. HLA in coeliac disease families: a novel test of risk modification by the ‘other’ haplotype when at least one DQA1*05-DQB1*02 haplotype is carried. Tissue Antigens. 2002;60:147–54. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2002.600205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Belzen MJ, Koeleman BP, Crusius JB, et al. Defining the contribution of the HLA region to cis DQ2-positive coeliac disease patients. Genes Immun. 2004;5:215–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sollid LM, Markussen G, Ek J, Gjerde H, Vartdal F, Thorsby E. Evidence for a primary association of celiac disease to a particular HLA-DQ alpha/beta heterodimer. J Exp Med. 1989;169:345–50. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.1.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spurkland A, Sollid LM, Polanco I, Vartdal F, Thorsby E. HLA-DR and -DQ genotypes of celiac disease patients serologically typed to be non DR3 or non-DR5/7. Hum Immunol. 1992;35:188–92. doi: 10.1016/0198-8859(92)90104-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Karell K, Louka AS, Moodie SJ, et al. HLA types in celiac disease patients not carrying the DQA1*05–DQB1*02 (DQ2) heterodimer: results from the European Genetics Cluster on Celiac Disease. Hum Immunol. 2003;64:469–77. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(03)00027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Louka AS, Sollid LM. HLA in coeliac disease: unravelling the complex genetics of a complex disorder. Tissue Antigens. 2003;61:105–17. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2003.00017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Louka AS, Moodie SJ, Karell K, et al. A collaborative European search for non-DQA1*05–DQB1*02 celiac disease loci on HLA-DR3 haplotypes: analysis of transmission from homozygous parents. Hum Immunol. 2003;64:350–8. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(02)00822-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Greco L, Babron MC, Corazza GR, et al. Existence of a genetic risk factor on chromosome 5q in Italian coeliac disease families. Ann Hum Genet. 2001;65:35–41. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-1809.2001.6510035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Greco L, Corazza G, Babron MC, et al. Genome search in celiac disease. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:669–75. doi: 10.1086/301754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van Belzen MJ, Meijer JW, Sandkuijl LA, et al. A major non-HLA locus in celiac disease maps to chromosome 19. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1032–41. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)01205-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Djilali-Saiah I, Schmitz J, Harfouch-Hammoud E. CTLA-4 gene polymorphism is associated with predisposition to coeliac disease. Gut. 1998;43:187–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.2.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Monsuur AJ, de Bakker PI, Alizadeh BZ, et al. Myosin IXB variant increases the risk of celiac disease and points toward a primary intestinal barrier defect. Nat Genet. 2005;37:1341–4. doi: 10.1038/ng1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hunt KA, Monsuur AJ, McArdle WL, et al. Lack of association of MYO9B genetic variants with coeliac disease in a British cohort. Gut. 2006;55:969–72. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.086769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Amundsen SS, Monsuur AJ, Wapenaar MC, et al. Association analysis of MYO9B gene polymorphisms with celiac disease in a Swedish/Norwegian cohort. Hum Immunol. 2006;67:341–5. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2006.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sanchez E, Alizadeh BZ, Valdigem G, et al. MYO9B gene polymorphisms are associated with autoimmune diseases in Spanish population. Hum Immunol. 2007;68:610–15. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Anand BS, Piris J, Jerrome DW, Offord RE, Truelove SC. The timing of histological damage following a single challenge with gluten in treated coeliac disease. Q J Med. 1981;50:83–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nilsen EM, Jahnsen FL, Lundin KE, et al. Gluten induces an intestinal cytokine response strongly dominated by interferon gamma in patients with celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:551–63. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70134-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Monteleone I, Monteleone G, Vecchio Blanco DG, et al. Regulation of the T helper cell type 1 transcription factor T-bet in coeliac disease mucosa. Gut. 2004;53:1090–5. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.030551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Di Sabatino A, Pickard KM, Gordon JN, et al. Evidence for the role of interferon-alfa production by dendritic cells in the Th1 response in celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1175–87. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Salvati VM, MacDonald TT, Bajaj-Elliott M, et al. Interleukin 18 and associated markers of T helper cell type 1 activity in coeliac disease. Gut. 2002;50:186–90. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.2.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Monteleone G, Pender SL, Alstead E, et al. Role of interferon alpha in promoting T helper cell type 1 responses in the small intestine in coeliac disease. Gut. 2001;48:425–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.3.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Leon AJ, Garrote JA, Blanco-Quiros A, et al. Interleukin 18 maintains a long-standing inflammation in coeliac disease patients. Clin Exp Immunol. 2006;146:479–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03239.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Raki M, Tollefsen S, Molberg O, Lundin KE, Sollid LM, Jahnsen FL. A unique dendritic cell subset accumulates in the celiac lesion and efficiently activates gluten-reactive T cells. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:428–38. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lundin KE, Scott H, Hansen T, et al. Gliadin-specific, HLA-DQ (alpha 1*0501,beta 1*0201) restricted T cells isolated from the small intestinal mucosa of celiac disease patients. J Exp Med. 1993;178:187–96. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.1.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lundin KE, Scott H, Fausa O, Thorsby E, Sollid LM. T cells from the small intestinal mucosa of a DR4, DQ7/DR4, DQ8 celiac disease patient preferentially recognize gliadin when presented by DQ8. Hum Immunol. 1994;41:285–91. doi: 10.1016/0198-8859(94)90047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Arentz-Hansen H, Korner R, Molberg O, et al. The intestinal T cell response to alpha-gliadin in adult celiac disease is focused on a single deamidated glutamine targeted by tissue transglutaminase. J Exp Med. 2000;191:603–12. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.4.603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Anderson RP, Degano P, Godkin AJ, Jewell DP, Hill AV. In vivo antigen challenge in celiac disease identifies a single transglutaminase-modified peptide as the dominant A-gliadin T-cell epitope. Nat Med. 2000;6:337–42. doi: 10.1038/73200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Anderson RP, van Heel DA, Tye-Din JA, et al. T cells in peripheral blood after gluten challenge in coeliac disease. Gut. 2005;54:1217–23. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.059998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Arentz-Hansen H, McAdam SN, Molberg O, et al. Celiac lesion T cells recognize epitopes that cluster in regions of gliadins rich in proline residues. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:803–9. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.35381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vader W, Kooy Y, Van Veelen P, et al. The gluten response in children with celiac disease is directed toward multiple gliadin and glutenin peptides. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1729–37. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sjostrom H, Lundin KE, Molberg O, et al. Identification of a gliadin T-cell epitope in coeliac disease: general importance of gliadin deamidation for intestinal T-cell recognition. Scand J Immunol. 1998;48:111–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1998.00397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tollefsen S, Arentz-Hansen H, Fleckenstein B, et al. HLA-DQ2 and -DQ8 signatures of gluten T cell epitopes in celiac disease. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2226–36. doi: 10.1172/JCI27620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vartdal F, Johansen BH, Friede T, et al. The peptide binding motif of the disease associated HLA-DQ (alpha 1*0501, beta 1*0201) molecule. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:2764–72. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830261132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.van de Wal Y, Kooy YM, Drijfhout JW, et al. alpha 1*0201, beta 1*0202) molecule. Immunogenetics. 1997;46:484–92. doi: 10.1007/s002510050309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Godkin A, Friede T, Davenport M, et al. Use of eluted peptide sequence data to identify the binding characteristics of peptides to the insulin-dependent diabetes susceptibility allele HLA-DQ8 (DQ 3.2) Int Immunol. 1997;9:905–11. doi: 10.1093/intimm/9.6.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kim CY, Quarsten H, Bergseng E, Khosla C, Sollid LM. Structural basis for HLA-DQ2-mediated presentation of gluten epitopes in celiac disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:4175–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306885101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.van de Wal Y, Kooy Y, van Veelen P, et al. Selective deamidation by tissue transglutaminase strongly enhances gliadin-specific T cell reactivity. J Immunol. 1998;161:1585–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dieterich W, Ehnis T, Bauer M, et al. Identification of tissue transglutaminase as the autoantigen of celiac disease. Nat Med. 1997;3:797–801. doi: 10.1038/nm0797-797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Molberg O, McAdam SN, Korner R, et al. Tissue transglutaminase selectively modifies gliadin peptides that are recognized by gut-derived T cells in celiac disease. Nat Med. 1998;4:713–17. doi: 10.1038/nm0698-713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fleckenstein B, Molberg O, Qiao SW, et al. Gliadin T cell epitope selection by tissue transglutaminase in celiac disease. Role of enzyme specificity and pH influence on the transamidation versus deamidation process. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:34109–16. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204521200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zanoni G, Navone R, Lunardi C, et al. In celiac disease, a subset of autoantibodies against transglutaminase binds Toll-like receptor 4 and induces activation of monocytes. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e358. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Myrsky E, Kaukinen K, Syrjanen M, Korponay-Szabo IR, Maki M, Lindfors K. Coeliac disease-specific autoantibodies targeted against transglutaminase 2 disturb angiogenesis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;152:111–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03600.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Korponay-Szabo IR, Halttunen T, Szalai Z, et al. In vivo targeting of intestinal and extraintestinal transglutaminase 2 by coeliac autoantibodies. Gut. 2004;53:641–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.024836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hadjivassiliou M, Maki M, Sanders DS, et al. Autoantibody targeting of brain and intestinal transglutaminase in gluten ataxia. Neurology. 2006;66:373–7. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000196480.55601.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hausch F, Shan L, Santiago NA, Gray GM, Khosla C. Intestinal digestive resistance of immunodominant gliadin peptides. Am J Physiol. 2002;283:G996, G1003. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00136.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sturgess R, Day P, Ellis HJ, et al. Wheat peptide challenge in coeliac disease. Lancet. 1994;343:758–61. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91837-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fraser JS, Engel W, Ellis HJ, et al. Coeliac disease: in vivo toxicity of the putative immunodominant epitope. Gut. 2003;52:1698–702. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.12.1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Maiuri L, Picarelli A, Boirivant M, et al. Definition of the initial immunologic modifications upon in vitro gliadin challenge in the small intestine of celiac patients. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1368–78. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8613040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Maiuri L, Ciacci C, Ricciardelli I, et al. Association between innate response to gliadin and activation of pathogenic T cells in coeliac disease. Lancet. 2003;362:30–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13803-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Di Sabatino A, Ciccocioppo R, Cupelli F, et al. Epithelium derived interleukin 15 regulates intraepithelial lymphocyte Th1 cytokine production, cytotoxicity, and survival in coeliac disease. Gut. 2006;55:469–77. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.068684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mention JJ, Ben Ahmed M, Begue B, et al. Interleukin 15: a key to disrupted intraepithelial lymphocyte homeostasis and lymphomagenesis in celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:730–45. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)01047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jabri B, de Serre NP, Cellier C, et al. Selective expansion of intraepithelial lymphocytes expressing the HLA-E-specific natural killer receptor CD94 in celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:867–79. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(00)70173-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Meresse B, Curran SA, Ciszewski C, et al. Reprogramming of CTLs into natural killer-like cells in celiac disease. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1343–55. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hue S, Mention JJ, Monteiro RC, et al. A direct role for NKG2D/MICA interaction in villous atrophy during celiac disease. Immunity. 2004;21:367–77. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hirschhorn JN, Daly MJ. Genome-wide association studies for common diseases and complex traits. Nat Rev. 2005;6:95–108. doi: 10.1038/nrg1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2007;447:661–78. doi: 10.1038/nature05911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gorlov IP, Gorlova OY, Sunyaev SR, Spitz MR, Amos CI. Shifting paradigm of association studies: value of rare single-nucleotide polymorphisms. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:100–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Korbel JO, Urban AE, Affourtit JP, et al. Paired-end mapping reveals extensive structural variation in the human genome. Science. 2007;318:420–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1149504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Estivill X, Armengol L. Copy number variants and common disorders: filling the gaps and exploring complexity in genome-wide association studies. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:1787–99. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Waldmann TA. The biology of interleukin-2 and interleukin-15: implications for cancer therapy and vaccine design. Nat Rev. 2006;6:595–601. doi: 10.1038/nri1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lenardo MJ. Fas and the art of lymphocyte maintenance. J Exp Med. 1996;183:721–4. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Fontenot JD, Rasmussen JP, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. A function for interleukin 2 in Foxp3-expressing regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1142–51. doi: 10.1038/ni1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Maloy KJ, Powrie F. Fueling regulation: IL-2 keeps CD4+ Treg cells fit. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1071–2. doi: 10.1038/ni1105-1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yamanouchi J, Rainbow D, Serra P, et al. Interleukin-2 gene variation impairs regulatory T cell function and causes autoimmunity. Nat Genet. 2007;39:329–37. doi: 10.1038/ng1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Fina D, Sarra M, Caruso R, et al. Interleukin-21 contributes to the mucosal T helper cell type 1 response in celiac disease. Gut. 2007 doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.129882. online early. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Leonard WJ, Spolski R. Interleukin-21: a modulator of lymphoid proliferation, apoptosis and differentiation. Nat Rev. 2005;5:688–98. doi: 10.1038/nri1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mathew CG. New links to the pathogenesis of Crohn disease provided by genome-wide association scans. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;9:9–14. doi: 10.1038/nrg2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Todd JA, Walker NM, Cooper JD, et al. Robust associations of four new chromosome regions from genome-wide analyses of type 1 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2007;39:857–64. doi: 10.1038/ng2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Pennington DJ, Silva-Santos B, Shires J, et al. The inter-relatedness and interdependence of mouse T cell receptor gammadelta+ and alphabeta+ cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:991–8. doi: 10.1038/ni979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Han SB, Moratz C, Huang NN, et al. Rgs1 and Gnai2 regulate the entrance of B lymphocytes into lymph nodes and B cell motility within lymph node follicles. Immunity. 2005;22:343–54. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Li Y, He X, Schembri-King J, Jakes S, Hayashi J. Cloning and characterization of human Lnk, an adaptor protein with pleckstrin homology and Src homology 2 domains that can inhibit T cell activation. J Immunol. 2000;164:5199–206. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.10.5199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Velazquez L, Cheng AM, Fleming HE, et al. Cytokine signaling and hematopoietic homeostasis are disrupted in Lnk-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1599–611. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lemmon MA. Membrane recognition by phospholipid-binding domains. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:99–111. doi: 10.1038/nrm2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lindvall JM, Blomberg KE, Valiaho J, et al. Bruton's tyrosine kinase: cell biology, sequence conservation, mutation spectrum, siRNA modifications, and expression profiling. Immunol Rev. 2005;203:200–15. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Carpten JD, Faber AL, Horn C, et al. A transforming mutation in the pleckstrin homology domain of AKT1 in cancer. Nature. 2007;448:439–44. doi: 10.1038/nature05933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Mao M, Biery MC, Kobayashi SV, et al. T lymphocyte activation gene identification by coregulated expression on DNA microarrays. Genomics. 2004;83:989–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2003.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Farrell RJ, Kelly CP. Celiac sprue. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:180–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra010852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zhernakova A, Alizadeh BZ, Bevova M, et al. Novel association in chromosome 4q27 region with rheumatoid arthritis and confirmation of type 1 diabetes point to a general risk locus for autoimmune diseases. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:1284–8. doi: 10.1086/522037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Liu Y, Helms C, Liao W, et al. A genome-wide association study of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis identifies new disease loci. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000041. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ballotti S, de Martino M. Rotavirus infections and development of type 1 diabetes: an evasive conundrum. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;45:147–56. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31805fc256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Altshuler D, Hirschhorn JN, Klannemark M, et al. The common PPARgamma Pro12Ala polymorphism is associated with decreased risk of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2000;26:76–80. doi: 10.1038/79216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.van Dam RM, Hoebee B, Seidell JC, Schaap MM, de Bruin TW, Feskens EJ. Common variants in the ATP-sensitive K+ channel genes KCNJ11 (Kir6.2) and ABCC8 (SUR1) in relation to glucose intolerance: population-based studies and meta-analyses. Diabet Med. 2005;22:590–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]