Abstract

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS SUBJECT

Enriched enrolment (the exclusion of non-responders or specific inclusion of responders) is believed to add both to trial sensitivity and to the measured effect of an intervention.

Enriched enrolment lacks specific definition, and the extent of any differences between results with non-enriched recruitment and enriched enrolment is not known.

Enriched enrolment is thought to have influenced neuropathic pain trials.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

The paper suggests definitions for complete and partial enriched enrolment, and applies those definitions to trials of pregabalin and gabapentin in neuropathic pain.

The effect of enrichment was small, and especially in pregabalin trials with the best data, no difference was found between partial enrichment and no enrichment.

The effects of complete enrichment are unknown.

AIMS

Enriched enrolment study designs have been suggested to be useful for proof of concept when only a proportion of the diseased population responds to a treatment intervention. We aim to investigate whether this really is the case in trials of pregabalin and gabapentin in neuropathic pain.

METHODS

We defined ‘complete’, ‘partial’ and ‘non-enriched’ enrolment, and examined pregabalin and gabapentin trials for the extent of enrichment and for effects of enrichment on efficacy and adverse event outcomes.

RESULTS

There were no studies using complete enriched enrolment; seven trials used partial enriched enrolment and 14 non-enriched enrolment. In pregabalin trials the maximum extent of enrichment was estimated at about 12%. Partial enriched enrolment did not change estimates of efficacy or harm. Over 150–600 mg maximum daily dose there was strong dose dependence for pregabalin.

CONCLUSIONS

A benefit of partial over non-enriched enrolment could not be demonstrated because the degree of enrichment was rather small, and possibly because enrichment produced little enhancement of treatment effect. Whether a greater degree of enrichment would result in important differences is unknown. Researchers reporting clinical trials with any enrichment must describe both process and extent of enrichment. As things stand, the effects of enriched enrolment remain unknown for neuropathic pain trials.

Keywords: enriched enrolment, gabapentin, neuropathic pain, pregabalin

Introduction

Enriched enrolment studies aim to increase the proportion of responders in a clinical trial population and to decrease the number of patients withdrawing because of intolerable or unmanageable adverse events. This should enhance the average benefit of study drug over placebo where only a subset of the diseased population responds to the intervention [1]. Enriched enrolment strategies were described as early as 1975 [2], and several have been used in chronic pain trials [3]. Flexible titration of dose to effect in individual patients can also minimise initial adverse event experiences compared with forced titration or fixed-dose schedules.

One approach is to give all enrolled subjects the study drug openly, and identify those who respond; responders are then randomized to either study drug or placebo in a double-blind fashion [4]. Another enrichment strategy is to identify drug responders with a randomized controlled trial (RCT) and then enrol those responders in another RCT of study drug vs. placebo [5]. Responders can also be identified before enrolment as those who take the drug and report benefit [6]. Yet another possible approach (the ‘flare design’) is to take patients already on analgesic and then stop their analgesic. Only those whose pain worsens (‘flares’) are then entered into a RCT of study drug vs. placebo [7], increasing the sensitivity for any subsequent intervention. Exclusion of non-responders is another way of achieving enrichment.

Neuropathic pain is the consequence of lesions in the central nervous system (e.g. cerebrovascular accident, multiple sclerosis or spinal cord injury) or peripheral nervous system (e.g. painful diabetic neuropathy, postherpetic neuralgia). It has a significant negative impact on quality of life [8]. Some patients with neuropathic pain respond well to treatment and others show no obvious response [9–11]. No pharmacological intervention produces meaningful relief for more than half the patients with neuropathic pain [12].

Antiepileptic drugs have been successfully used in pain management for four decades [10]. Their effectiveness in neuropathic pain syndromes is not surprising as both epilepsy and neuropathic pain can arise because of abnormal neuronal activation following an insult to nerve cells. Pregabalin and gabapentin have been shown to be effective in neuropathic pain [13, 14], and are thought to bind to the alpha-2-delta subunit of presynaptic voltage-gated calcium channels and modulate channel activity [15].

Some recent trials of pregabalin and gabapentin in neuropathic pain have used enriched enrolment designs. In this systematic review we aim to analyze the impact of enriched enrolment strategies on efficacy and adverse event outcomes in trials of pregabalin and gabapentin in neuropathic pain.

Methods

Searching

Full publications of trials of pregabalin and gabapentin in neuropathic pain conditions were identified by a MEDLINE (PubMed) search. The date of last search was 26th July 2007. Our search terms were ‘pregabalin’ and ‘gabapentin’ with the ‘limits’ in PubMed set to include randomized controlled trials only. Reference lists of identified papers and review articles were examined for possible additional references. We also searched through a file of papers collected for a Cochrane review of gabapentin [14] and contacted Pfizer Ltd for relevant publications.

Study selection

We identified reports of randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trials published in any language in which pregabalin and gabapentin were given to patients with neuropathic pain. We excluded trials on postoperative pain. For the assessment of withdrawal and adverse event outcomes we also excluded trials using ‘active placebo’ (i.e. an active medication intended to cause adverse effects but no analgesia).

Quality assessment

Trial quality was assessed using a validated three-item scale with a maximum quality score of five [16]. Included studies had to score at least two points, one for randomization and one for blinding. Quality assessments were made independently by at least two reviewers and verified by one other reviewer. Disputes were settled by discussion between all reviewers.

Definitions of enriched enrolment strategies

We used the following definitions to categorize trials, based on the degree of enrichment that various strategies might be expected to attain. These definitions assume that clinically effective doses are used.

Complete enriched enrolment (CEE) would occur in two circumstances. One would be the inclusion criterion of all participants responding to the test drug or a closely related drug with similar mechanism of action, within a clinical trial or with a satisfactory response in clinical practice. Another would be the exclusion criterion of non-response to the test drug or a closely related drug, and when all participants had been exposed to the drug.

Partial enriched enrolment (PEE) was defined as the exclusion from the study of any previous non-responders to the study drug or a similar drug, but where not all participants were known to have been exposed. This measure leads to an unknown degree of enrichment of responders to the study drug.

We defined all other forms of enrolment as non-enriched enrolment (NEE) when no statement of inclusion or exclusion of patients could be interpreted as enriching the population to drug responders.

Outcomes

We extracted the following outcomes wherever they were reported in terms of a proportion or percentage of trial participants:

At least 50% pain relief

Patient global impression of change (PGIC): ‘much or very much improvement’

Withdrawals due to lack of efficacy

Withdrawals due to adverse events

Somnolence

Dizziness

PGIC was extracted only where the proportion/percentage of subjects considering their pain ‘much or very much improved’ on the seven-point PGIC scale was available. We did not use data for all improved (including ‘minimally improved’) or other scales of impression of change. Somnolence and dizziness are common adverse events reported with pregabalin and gabapentin.

Quantitative data synthesis

We compared efficacy and adverse event outcomes with CEE, PEE and NEE, at all doses combined, and at different drug doses. To produce an intention to treat analysis the number of patients randomized was taken as the basis for calculations. We calculated the number needed to treat or harm (NNT or NNH) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) from the sum of all events and patients for treatment and placebo [17]. Relative benefit and risk estimates with 95% CIs were calculated using the fixed effects model [18], and were considered to be statistically significant when the 95% CI did not include 1.

Heterogeneity tests were not used as they have previously been shown to be unhelpful, though homogeneity was examined visually [19–21]. Publication bias was not assessed using funnel plots as these tests have been shown to be unhelpful [22, 23]. Statistically significant differences between NNTs were established using the z test [24]. QUOROM guidelines were followed [25].

Results

Included and excluded trials

We identified 29 randomized placebo-controlled trials investigating the effect of pregabalin and gabapentin in neuropathic pain syndromes; 21 trials were included in this systematic review, nine using pregabalin [13, 26–33] and 12 using gabapentin [34–45]. Eight trials were excluded. Five trials had no useful data [46–50], one used an active placebo [51], one [52] reported on the same trial as a previous report [30], and one report in Turkish was found on translation to have no placebo group [53].

No trial used CEE. Seven trials used PEE and the remaining 14 used NEE. The characteristics of these studies are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included trials

| Study | Enrolment | Number of patients in trial | Condition | Study design and duration | Quality score | Maximum daily dose of pregabalin or gabapentin | Sponsorship |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pregabalin trials | |||||||

| Dworkin [26] | PEE | 173 | Postherpetic neuralgia | Parallel group design, 8 weeks duration | 5 | 600 mg | Pfizer |

| Lesser [27] | PEE | 337 | Painful diabetic neuropathy | Parallel group design, 5 weeks duration | 5 | 75 mg, 300 mg and 600 mg (three groups)* | Pfizer |

| Rosenstock [13] | PEE | 146 | Painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy | Parallel group design, 8 weeks duration | 4 | 300 mg | Pfizer |

| Sabatowski [28] | PEE | 238 | Postherpetic neuralgia | Parallel group design, 8 weeks duration | 5 | 150 mg and 300 mg (two groups) | Parke-Davis/Pfizer |

| Crofford [29] | PEE | 529 | Fibromyalgia | Parallel group design, 8 weeks duration | 4 | 150 mg, 300 mg and 450 mg (three groups) | Pfizer |

| Freynhagen [30] | NEE | 338 | Postherpetic neuralgia, Painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy | Parallel group design, 12 weeks duration | 3 | 600 mg | Pfizer |

| Richter [31] | NEE | 246 | Painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy | Parallel group design, 6 weeks duration | 5 | 150 mg and 600 mg (two groups) | Pfizer |

| Siddall [32] | NEE | 137 | Neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury | Parallel group design, 12 weeks duration | 5 | 600 mg | Pfizer |

| Van Seventer [33] | NEE | 368 | Postherpetic neuralgia | Parallel group design, 13 weeks duration | 3 | 150 mg, 300 mg and 600 mg (three groups) | Pfizer |

| Gabapentin trials | |||||||

| Backonja [34] | NEE | 165 | Painful diabetic neuropathy | Parallel group design, 8 weeks duration | 5 | 3600 mg | Parke-Davis |

| Rowbotham [35] | NEE | 229 | Postherpetic neuralgia | Parallel group design, 8 weeks duration | 5 | 3600 mg | Parke-Davis |

| Rice [36] | PEE | 334 | Postherpetic neuralgia | Parallel group design, 7 weeks duration | 5 | 1800 mg and 2400 mg (two groups) | Pfizer |

| Simpson [37] | NEE | 60 | Painful diabetic neuropathy | Parallel group design, 8 weeks duration | 4 | 3600 mg | Not mentioned |

| Bone [38] | NEE | 19 | Post-amputation phantom limb pain | Crossover design, 2 × 6 week treatment, 1 week washout | 5 | 2400 mg | Pfizer |

| Serpell [39] | PEE | 305 | Various neuropathic pain syndromes | Parallel group design, 8 weeks duration | 5 | 2400 mg | Parke-Davis |

| Caraceni [40] | NEE | 121 | Neuropathic cancer pain | Parallel group design, 10 days duration | 5 | 1800 mg | Pfizer |

| Hahn [41] | NEE | 26 | Painful HIV-associated sensory neuropathies | Parallel group design, 4 weeks duration | 4 | 2400 mg | Pfizer |

| Levendoglu [42] | NEE | 20 | Neuropathic pain in paraplegic patients | Crossover design, 2 × 8 weeks treatment, 2 weeks washout | 4 | 3600 mg | No funds received in support of study |

| Van de Vusse [43] | NEE | 58 | Complex regional pain syndrome type I | Crossover design, 2 × 3 weeks treatment, 2 weeks washout | 5 | 1800 mg | Parke-Davis |

| Arnold [44] | NEE | 150 | Fibromyalgia | Parallel group design, 12 weeks duration | 3 | 2400 mg | NIH |

| Kimos [45] | NEE | 50 | Chronic masticatory myalgia | Parallel group design, 12 weeks duration | 5 | 4200 mg | University of Alberta Fund for Dentistry, Pharmascience Inc. |

A 75 mg group in this trial was ignored as it is sub-therapeutic. PEE, partial enriched enrolment; NEE, no enriched enrolment; Quality score [16] is a three item score consisting of two points for adequate description of randomization and blinding, and one for withdrawals and dropouts.

The nine pregabalin trials included a total of 2512 patients (45% male and 55% female) and were between 5 and 13 weeks in duration; mean age in these trials varied from 49 to 72 years. Trials investigated postherpetic neuralgia (four trials), painful diabetic neuropathy (four trials), fibromyalgia and neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury (one trial each). Quality scores were 5 in five trials, 4 in two trials, and 3 in two trials. Outcomes reported included the proportion of patients with at least 50% pain relief, patient and clinician global impression of change, pain scores, measures of sleep interference, profile of mood states, adverse events and withdrawals from the trials. The six outcome measures were well reported in the pregabalin trials so that a comparison could be made with regard to all of them.

The 12 gabapentin trials included a total of 1537 patients (43% male and 57% female) and were between 10 days and 18 weeks in duration; mean age in these trials varied from 34 to 75 years. Trials investigated various neuropathic pain syndromes (painful diabetic neuropathy (two trials), postherpetic neuralgia (two trials), post-amputation phantom limb pain, multiple neuropathic pain syndromes, neuropathic cancer pain, painful HIV-associated sensory neuropathies, neuropathic pain in paraplegic patients, complex regional pain syndrome type I, fibromyalgia and chronic masticatory myalgia). Quality scores were 5 in eight trials, 4 in three trials, and 3 in one trial. Outcomes reported included the proportion of patients with at least 50% pain relief, patient and clinician global impression of change, visual analogue and verbal rating pain scores, measures of sleep interference, profile of mood states, adverse events and withdrawals from the trials. Only a few gabapentin trials reported data for efficacy, though most reported withdrawal and adverse event outcomes.

Reasons for exclusions after screening were not usually given in detail, and no paper reported the number of exclusions because patients had not responded previously to pregabalin, gabapentin, or a similar drug. For the pregabalin trials we assessed the possible extent of enrichment by examining the percentage of patients excluded after screening. For four trials with NEE, the average rate of exclusion was 27% (range 15% to 38%); for five trials with PEE, the average rate of exclusion was 35% (range 22% to 42%). The average maximum degree of enrichment would therefore be 8% of screened patients, and about 12% of patients randomized.

Pregabalin

At least 50% pain relief

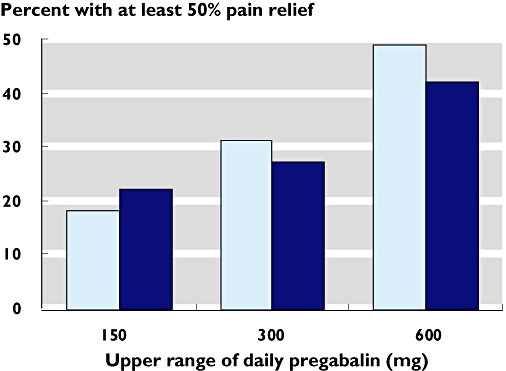

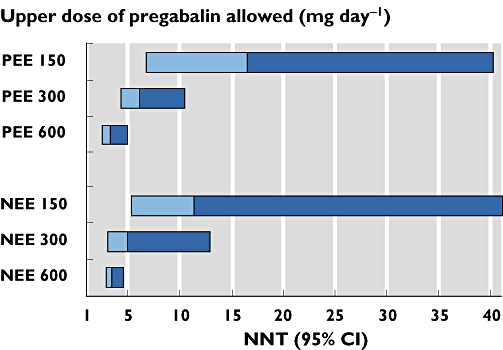

The effect of pregabalin was dose-dependent with higher daily doses of pregabalin resulting in greater pain relief. This was true for trials using PEE and NEE (Table 2), both for percent of patients achieving at least 50% pain relief (Figure 1) and NNT (Figure 2). Comparing the NNTs for all trials taken together, there was a significant benefit of 300 mg pregabalin vs. 150 mg (P = 0.040) and 600 mg vs. 150 mg (P < 0.00006), as well as for 600 mg vs. 300 mg (P = 0.016). Analyzing NEE and PEE separately, there were still significant benefits of 600 mg vs. 150 mg pregabalin daily (P = 0.0014 and P = 0.00032, respectively).

Table 2.

Main results in pregabalin trials

| Efficacy | % with | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subgroup | Number of patients | Relative benefit (95% CI) | NNT (95% CI) | Placebo | Pregabalin |

| At least 50% pain relief | |||||

| All | 2430 | 2.4 (2.0, 2.8) | 5.2 (4.5, 6.4) | 14 | 33 |

| PEE | 1342 | 2.3 (1.6, 2.9) | 6.3 (4.9, 8.7) | 15 | 31 |

| NEE | 1088 | 2.4 (1.8, 3.3) | 4.4 (3.6, 5.6)a | 13 | 36 |

| 150 mg | 538 | 1.6 (1.0, 2.5) | 14 (7.3, 150) | 13 | 20 |

| 300 mg | 697 | 2.4 (1.7, 3.5) | 6.1 (4.4, 9.5)b | 13 | 30 |

| 600 mg | 1195 | 2.6 (3.0, 3.3) | 3.8 (3.2, 4.7)c | 16 | 42 |

| Patient global impression of change | |||||

| All | 1724 | 2.0 (1.6, 2.3) | 4.7 (3.9, 6.0) | 22 | 43 |

| PEE | 1018 | 2.1 (1.7, 2.6) | 4.3 (3.4, 5.8) | 22 | 45 |

| NEE | 706 | 1.8 (1.3, 2.4) | 5.3 (3.8, 9.1) | 22 | 41 |

| 150 mg | 416 | 1.5 (1.0, 2.2) | 11 (5.5, 350) | 20 | 29 |

| 300 mg | 549 | 2.1 (1.5, 2.9) | 4.8 (3.5, 7.7)d | 20 | 41 |

| 600 mg | 759 | 2.1 (1.6, 2.7) | 3.7 (2.9, 5.1)e | 25 | 52 |

| Lack of efficacy withdrawal | |||||

| All | 2174 | 0.36 (0.27, 0.49) | −12 (−19, −9.0) | 14 | 6 |

| PEE | 1085 | 0.33 (0.20, 0.54) | −18 (−45, −11) | 10 | 4 |

| NEE | 1089 | 0.38 (0.27, 0.53) | −8.4 (−14, −6.0)f | 20 | 8 |

| 150 mg | 538 | 0.55 (0.32, 0.95) | −23 (71, −10) | 12 | 8 |

| 300 mg | 568 | 0.39 (0.22, 0.72) | −20 (−750, −9.9) | 11 | 5 |

| 600 mg | 1068 | 0.28 (0.19, 0.42) | −8.4 (−14, −6.1)g | 18 | 6 |

| Harm | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| with | |||||

| Subgroup | Number of patients | Relative risk (95% CI) | NNH (95% CI) | Placebo | Pregabalin |

| Adverse event withdrawal | |||||

| All | 2431 | 2.2 (1.6, 2.9) | 14 (10, 20) | 6 | 14 |

| PEE | 1343 | 2.2 (1.5, 3.2) | 16 (11, 30) | 6 | 12 |

| NEE | 1089 | 2.1 (1.4, 3.3) | 12 (8.3, 23) | 7 | 16 |

| 150 mg | 538 | 1.0 (0.52, 1.9) | 960 (20, −21) | 8 | 8 |

| 300 mg | 697 | 1.7 (1.0, 3.1) | 21 (11, 150) | 6 | 10 |

| 600 mg | 1197 | 3.0 (2.0, 4.5) | 8.3 (6.3, 12)h | 7 | 19 |

| Somnolence | |||||

| All | 2432 | 4.4 (3.2, 6.1) | 6.7 (5.8, 8.1) | 5 | 20 |

| PEE | 1343 | 4.4 (2.9, 6.7) | 5.6 (4.7, 7.0) | 5 | 23 |

| NEE | 1089 | 4.4 (2.6, 7.6) | 8.6 (6.6, 12)i | 5 | 16 |

| 150 mg | 538 | 2.0 (1.0, 4.1) | 16 (9.0, 73) | 6 | 12 |

| 300 mg | 697 | 4.9 (2.6, 9.2) | 5.8 (4.6, 7.9)j | 4 | 22 |

| 600 mg | 1197 | 5.4 (3.4, 8.7) | 5.7 (4.7, 7.2)k | 5 | 22 |

| Dizziness | |||||

| All | 2432 | 3.2 (2.5, 4.1) | 5.1 (4.4, 6.0) | 9 | 29 |

| PEE | 1343 | 2.9 (2.2, 3.9) | 4.9 (4.1, 6.2) | 11 | 31 |

| NEE | 1089 | 4.0 (2.6, 6.3) | 5.2 (4.3, 6.6) | 6 | 26 |

| 150 mg | 538 | 1.6 (0.96, 2.8) | 14 (7.8, 95) | 9 | 16 |

| 300 mg | 697 | 2.9 (1.9, 4.3) | 5.0 (3.9, 7.0)l | 11 | 31 |

| 600 mg | 1197 | 4.5 (3.1, 6.6) | 4.0 (3.4, 4.8)m | 8 | 33 |

NNT, number needed to treat. NNH, number needed to harm. 150 mg, 300 mg and 600 mg refer to the maximum daily doses of pregabalin allowed in the trials. For patient global impression of change after pregabalin treatment we display the results for subjects reporting ‘much or very much’ improvement, and the 600 mg subgroup contains data from one trial group [29] that used 450 mg as the maximum allowed daily dose of pregabalin. Lack of efficacy withdrawals also includes those described as ‘treatment failure’. Significant differences between treatment groups are labelled in the figure as follows: a) P = 0.044 for the comparison PEE vs. NEE, b) P = 0.040 for 150 mg vs. 300 mg, c) P < 0.00006 for 150 mg vs. 600 mg, d) P = 0.052 for 150 mg vs. 300 mg. e) P < 0.0027 for 150 mg vs. 600 mg. f) P = 0.036 for PEE vs. NEE. g) P = 0.039 for 150 mg vs. 600 mg. h) P < 0.00014 for 150 mg vs. 600 mg. i) P = 0.014 for PEE vs. NEE. j) P = 0.0014 for 150 mg vs. 300 mg. k) P < 0.00032 for 150 mg vs. 600 mg. l) P < 0.0019 for 150 mg vs. 300 mg. m) P < 0.00006 for 150 mg vs. 600 mg.

Figure 1.

Rate of at least 50% pain relief with pregabalin according to the use of partial enriched enrolment (PEE) ( ) or non-enriched enrolment (NEE) (

) or non-enriched enrolment (NEE) ( ). Response to placebo was 12, 14, and 19% in PEE trials, and 14, 6, and 14% in NEE trials, for studies with titration to 150, 300, and 600 mg respectively

). Response to placebo was 12, 14, and 19% in PEE trials, and 14, 6, and 14% in NEE trials, for studies with titration to 150, 300, and 600 mg respectively

Figure 2.

NNT (at least 50% pain relief compared with placebo) for dose response in pregabalin trials according to the use of partial enriched enrolment (PEE) or non-enriched enrolment (NEE)

There was no indication that PEE was associated with a greater response to pregabalin compared with that to placebo. The all-dose NNT for trials with PEE (6.3 (4.9, 8.7)) was higher (worse) than trials with NEE (4.4 (3.6, 5.6)), a statistically significant difference (P = 0.044). To investigate this, we calculated the mean values of the maximum allowed daily pregabalin doses in these two groups of trials. The mean value was higher for the NEE trials (466 mg) than for the PEE trials (344 mg).

Patient global impression of change (PGIC)

There was significant dose dependence to the results for patients rating their pain as ‘much or very much improved’ on the seven-point PGIC scale (Table 2). Comparing the NNTs there was borderline significant benefit for maximum daily dose of 300 mg compared with 150 mg, and a clear significant benefit for 600 mg compared with 150 mg. There was no significant difference between NEE and PEE pooling results from all doses.

Withdrawals

There were significantly fewer withdrawals for lack of efficacy in the 600 mg pregabalin treatment subgroup compared with the 150 mg group (Table 2). The significant difference between NEE and PEE pooling results from all doses was largely due to a much lower rate of lack of efficacy withdrawal in trials with partial enriched enrolment (Table 2).

Adverse events withdrawals were significantly more frequent in the 600 mg subgroup vs. the 150 mg subgroup (Table 2). There was no significant difference between NEE and PEE taking all doses together.

Somnolence and dizziness

For both somnolence and dizziness there was a significant dose-dependence (Table 2). A higher proportion of patients experienced somnolence in the PEE trials than NEE trials with all doses together.

Gabapentin

The efficacy outcomes considered in this review were reported in too few studies to make meaningful comparisons between trials using different enrolment strategies or between different doses of gabapentin.

Withdrawals

There were no significant differences between NEE and PEE trials for either adverse event withdrawals or lack of efficacy withdrawals when using all doses (Table 3). There was no significant dose–response over the range of 1800 mg and 3600 mg maximum allowed daily doses of gabapentin (Table 3).

Table 3.

Main results in gabapentin trials

| Efficacy | % with | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subgroup | Number of patients | Relative benefit (95% CI) | NNT (95% CI) | Placebo | Gabapentin |

| Lack of efficacy withdrawal | |||||

| All | 1425 | 0.41 (0.19, 0.87) | −56 (−510, −30) | 3 | 1 |

| PEE | 639 | 0.41 (0.14, 1.2) | −55 (140, −23) | 3 | 2 |

| NEE | 786 | 0.40 (0.14, 1.1) | −55 (430, −26) | 3 | 1 |

| 1800 mg | 287 | 0.98 (0.21, 4.5) | 250 (25, −31) | 2 | 3 |

| 2400 mg | 644 | 0.30 (0.09, 1.0) | −44 (3000, −22) | 3 | 1 |

| 3600 mg | 494 | 0.33 (0.09, 1.2) | −41 (360, −19) | 4 | 1 |

| Harm | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % with | |||||

| Subgroup | Number of patients | Relative risk (95% CI) | NNH (95% CI) | Placebo | Gabapentin |

| Adverse event withdrawal | |||||

| All | 1546 | 1.4 (1.1, 1.9) | 26 (14, 140) | 9 | 13 |

| PEE | 639 | 1.4 (0.88, 2.1) | 31 (12, −47) | 12 | 15 |

| NEE | 907 | 1.5 (1.0, 2.3) | 27 (13, −2700) | 8 | 11 |

| 1800 mg | 408 | 1.8 (0.82, 3.8) | 21 (10, −810) | 5 | 10 |

| 2400 mg | 644 | 1.4 (0.91, 2.0) | 25 (11, −72) | 12 | 16 |

| 3600 mg | 494 | 1.4 (0.85, 2.4) | 27 (11, −57) | 9 | 12 |

| Somnolence | |||||

| All | 1526 | 3.4 (2.5, 4.7) | 6.4 (5.3, 8.1) | 6 | 22 |

| PEE | 639 | 2.9 (1.7, 5.0) | 8.8 (6.2, 15) | 6 | 17 |

| NEE | 887 | 3.3 (2.6, 5.4) | 5.2 (4.2, 6.8)a | 7 | 26 |

| 1800 mg | 396 | 2.9 (1.6, 5.4) | 7.2 (4.9, 14) | 7 | 21 |

| 2400 mg | 682 | 3.0 (1.9, 4.8) | 7.1 (5.3, 11) | 7 | 21 |

| 3600 mg | 448 | 4.7 (2.6, 8.5) | 5.1 (3.8, 7.6) | 5 | 25 |

| Dizziness | |||||

| All | 1576 | 3.5 (2.7, 4.9) | 5.3 (4.5, 6.5) | 7 | 26 |

| PEE | 639 | 3.2 (2.1, 4.9) | 4.9 (3.9, 6.9) | 9 | 29 |

| NEE | 937 | 3.8 (2.6, 5.6) | 5.7 (4.6, 7.6) | 6 | 24 |

| 1800 mg | 396 | 4.5 (2.3, 8.7) | 5.0 (3.8, 7.5) | 6 | 26 |

| 2400 mg | 682 | 2.8 (1.9, 4.0) | 5.5 (4.2, 7.9) | 10 | 28 |

| 3600 mg | 498 | 4.3 (2.6, 8.2) | 5.3 (4.0, 7.8) | 5 | 24 |

1800 mg, 2400 mg and 3600 mg refer to the maximum available daily doses of gabapentin. For the analysis of dizziness, the 3600 mg subgroup also contains one trial [45] using 4200 mg gabapentin as the maximum available daily dose. a) P = 0.019 for the comparison PEE vs. NEE.

Somnolence and dizziness

For somnolence, there were no differences between different doses of gabapentin. There was significantly more somnolence in NEE trials when using all doses combined (Table 3). For dizziness there were no significant differences between different gabapentin doses or between different types of enrolment strategies (Table 3).

Discussion

As best we know, this paper is the first to present definitions of enriched enrolment strategies in clinical trials. The distinction between CEE, PEE and NEE allows more accurate description, analysis and comparison of enrolment strategies and their effects in this and subsequent studies.

Enriched enrolment in gabapentin and pregabalin studies has been described as a ‘flaw’[12], and in lidocaine plaster studies enriched enrolment should be ‘interpreted with caution’[54]. Pregabalin and gabapentin trials in neuropathic pain did not allow evaluation of CEE, since none of the trials had this design. While some pregabalin trials had a PEE design, the extent of enrichment was small. Only two gabapentin trials used PEE, and most trials did not report efficacy in a useful way. Uncertainty about the effects of a degree of PEE is not restricted to neuropathic pain; indirect comparison of PDE-5 inhibitors for erectile dysfunction was compromized by PEE for some drugs, but not another [55]. It is unlikely that any extant data set will unequivocally resolve the issue.

There was no consistent difference between NEE and PEE with regard to the trial outcomes analyzed in this review. The lack of any consistent difference may be explained by the relatively low degree of enrichment found in the pregabalin trials, and/or poor reporting of efficacy outcomes in gabapentin trials. Moreover, we have no explicit knowledge of the likelihood of response or non-response to gabapentin predicting response or non-response to pregabalin.

One example [56] of the use of pregabalin in a CEE design in fibromyalgia used a randomized withdrawal design [57], but is published only in abstract. In that trial 46% of the 1051 screened and treated population found pregabalin titrated to a maximum of 600 mg daily either ineffective or intolerable, and were excluded from the randomized withdrawal phase; this compares with an estimated 8% exclusion in the PEE trials in neuropathic pain in this review. The main result [56] was that 61% of patients continued to benefit from treatment with pregabalin compared with 32% with placebo, giving an NNT of 3.5 (2.7, 4.8). Despite the much larger degree of enrichment, the result was almost identical to the NNT of 3.8 (3.2, 4.7) for at least 50% pain relief found in our analysis in neuropathic pain, also titrating to 600 mg daily. While direct comparison is limited by different conditions and different outcomes, the implication is that even CEE makes little difference to the magnitude of the treatment effect, making any effect of PEE even more difficult to detect.

Only for the outcome of somnolence in gabapentin trials was PEE superior to classic NEE in that a smaller proportion of patients in the enriched enrolment trials experienced this adverse event compared with the patients in the NEE trials. However, in the pregabalin trials, somnolence was significantly more common with PEE compared with NEE.

With regard to the other outcomes in the pregabalin trials, the difference between all studies using PEE and NEE reached statistical significance for the outcomes of at least 50% pain relief and lack of efficacy withdrawals. In both cases NEE seemed advantageous. This was unexpected and it is not obvious why PEE should be worse than NEE. It is probably explained by having more trials with higher doses for NEE, together with a strong dose response.

The strong dose–response was seen for all efficacy and adverse event outcomes in the pregabalin trials. Higher doses were associated with more pain relief, and higher rates of adverse events. This has two important implications. Firstly it shows that titrating pregabalin to the maximum tolerated dose can be very worthwhile clinically as long as adverse events are tolerable. Secondly, it illustrates the importance of comparing like with like. With such dose dependence, the comparison between different enrolment strategies was made difficult by the fact that the trials used different drug doses. For the pregabalin trials, a comparison of like with like for the pain outcomes was possible after stratifying the trial groups according to dose. For the gabapentin trials such a comparison of like with like could not be undertaken for the pain outcomes because too few trials reported consistently defined efficacy outcomes. This is a limitation of this review.

The importance of the concept of comparing like with like when comparing treatment groups in trials and meta-analyses has been discussed elsewhere [58, 59]. For a comparison of different enrolment methods this concept should include the same dose of drug, especially when a dose–response is apparent. A pregabalin dose–response has been demonstrated over the range of 150–600 mg daily for treatment of partial seizures [60] and of generalized anxiety disorder [61]. We now have evidence for a dose–response with pregabalin in the relief of neuropathic pain over the clinical dose range.

Enriched enrolment strategies have to be assessed rigorously for their usefulness, as they have potential limitations. There are concerns about blinding in a randomized controlled trial when patients are known to (and know themselves that they) show a strong response to the study drug. Furthermore, there is a certain circularity of argument in demonstrating a response in people who have previously responded. Finally, carryover effects can be a problem when a drug given to subjects initially is then subsequently withdrawn. A therapeutically ineffective but pharmacologically active drug can appear superior to placebo because of pharmacological dependency induced during the open label treatment period that then becomes clinically symptomatic when the drug is withdrawn [62]. With this review we present a rigorous assessment of PEE in the case of pregabalin in neuropathic pain, but limitations of trials preclude any definite conclusion, especially as the example of CEE in fibromyalgia yielded a similar treatment effect to the same dose titration regimen of pregabalin for both PEE and NEE in neuropathic pain.

In conclusion, a benefit of PEE over NEE in terms of demonstrating the effect of the study drug compared with placebo could not be demonstrated, possibly because the degree of enrichment was rather small, and possibly because enrichment produced little enhancement of treatment effect. Whether a greater degree of enrichment would result in important differences is unknown. It is incumbent on researchers reporting clinical trials where there has been any enrichment process to describe both the process and extent of enrichment. As things stand, the effects of enriched enrolment remain unknown for neuropathic pain trials.

Acknowledgments

The authors were responsible completely for the original concept for the study, its analysis, and for writing of the manuscript. Pain Research is supported in part by the Oxford Pain Research Trust, and this work was also supported by an unrestricted educational grant from Pfizer Ltd. Neither organisation had any role in design, planning, execution of the study, or in writing the manuscript. The terms of the financial support from Pfizer included freedom for authors to reach their own conclusions, and an absolute right to publish the results of their research, irrespective of any conclusions reached. RAM and HJM have received speaking fees, consulting fees, and research grants from a number of organisations with interests in neuropathic pain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Freidlin B, Simon R. Evaluation of randomized discontinuation design. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5094–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amery W, Dony J. A clinical trial design avoiding undue placebo treatment. J Clin Pharmacol. 1975;15:674–9. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1975.tb05919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katz N. Methodological issues in clinical trials of opioids for chronic pain. Neurology. 2005;65:S32–49. doi: 10.1212/wnl.65.12_suppl_4.s32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lynch ME, Clark AJ, Sawynok J. Intravenous adenosine alleviates neuropathic pain: a double blind placebo controlled crossover trial using an enriched enrolment design. Pain. 2003;103:111–7. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00419-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byas-Smith MG, Max MB, Muir J, Kingman A. Transdermal clonidine compared to placebo in painful diabetic neuropathy using a two-stage ‘enriched enrollment’ design. Pain. 1995;60:267–74. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)00121-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galer BS, Rowbotham MC, Perander J, Friedman E. Topical lidocaine patch relieves postherpetic neuralgia more effectively than a vehicle topical patch: results of an enriched enrollment study. Pain. 1999;80:533–8. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00244-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peloso PM, Bellamy N, Bensen W, Thomson GT, Harsanyi Z, Babul N, Darke AC. Double blind randomized placebo control trial of controlled release codeine in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:764–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jensen MP, Chodroff MJ, Dworkin RH. The impact of neuropathic pain on health-related quality of life: review and implications. Neurology. 2007;68:1178–82. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000259085.61898.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jadad AR, Carroll D, Glynn CJ, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Morphine responsiveness of chronic pain: double-blind randomised crossover study with patient-controlled analgesia. Lancet. 1992;339:1367–71. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91194-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McQuay H, Carroll D, Jadad AR, Wiffen P, Moore A. Anticonvulsant drugs for management of pain: a systematic review. BMJ. 1995;311:1047–52. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7012.1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McQuay HJ, Tramer M, Nye BA, Carroll D, Wiffen PJ, Moore RA. A systematic review of antidepressants in neuropathic pain. Pain. 1996;68:217–27. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(96)03140-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Attal N, Cruccu G, Haanpaa M, Hansson P, Jensen TS, Nurmikko T, Sampaio C, Sindrup S, Wiffen P, EFNS Task Force EFNS guidelines on pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain. Eur J Neurol. 2006;13:1153–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenstock J, Tuchman M, LaMoreaux L, Sharma U. Pregabalin for the treatment of painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Pain. 2004;110:628–38. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiffen PJ, McQuay HJ, Edwards JE, Moore RA. Gabapentin for acute and chronic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005452. CD005452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stahl SM. Mechanism of action of alpha2delta ligands: voltage sensitive calcium channel (VSCC) modulators. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:1033–4. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cook RJ, Sackett DL. The number needed to treat: a clinically useful measure of treatment effect. BMJ. 1995;310:452–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6977.452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morris JA, Gardner MJ. Calculating confidence intervals for relative risk, odds ratios and standardised ratios and rates. In: Gardner MJ, Altman DG, editors. Statistics with confidence – Confidence intervals and statistical guidelines. London: British Medical Journal; 1995. pp. 50–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gavaghan DJ, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. An evaluation of homogeneity tests in meta-analyses in pain using simulations of individual patient data. Pain. 2000;85:415–24. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00302-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins J, Thompson S, Deeks J, Altman D. Statistical heterogeneity in systematic reviews of clinical trials: a critical appraisal of guidelines and practice. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2002;7:51–61. doi: 10.1258/1355819021927674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.L'Abbe KA, Detsky AS, O'Rourke K. Meta-analysis in clinical research. Ann Intern Med. 1987;107:224–33. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-107-2-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sterne JA, Gavaghan D, Egger M. Publication and related bias in meta-analysis: power of statistical tests and prevalence in the literature. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:1119–29. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00242-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tang J-L, Liu JL. Misleading funnel plot for detection of bias in meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:477–84. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00204-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tramer MR, Reynolds DJ, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Impact of covert duplicate publication on meta-analysis: a case study. BMJ. 1997;315:635–40. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moher D, Cook DJ, Eastwood S, Olkin I, Rennie D, Stroup DF. Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUOROM statement. Quality of reporting of meta-analyses. Lancet. 1999;354:1896–900. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)04149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dworkin RH, Corbin AE, Young JP, Jr, Sharma U, LaMoreaux L, Bockbrader H, Garofalo EA, Poole RM. Pregabalin for the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia: a randomized, placebo- controlled trial. Neurology. 2003;60:1274–83. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000055433.55136.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lesser H, Sharma U, LaMoreaux L, Poole RM. Pregabalin relieves symptoms of painful diabetic neuropathy: a randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 2004;63:2104–10. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000145767.36287.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sabatowski R, Galvez R, Cherry DA, Jacquot F, Vincent E, Maisonobe P, Versavel M, 1008-045 Study Group Pregabalin reduces pain and improves sleep and mood disturbances in patients with post-herpetic neuralgia: results of a randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Pain. 2004;109:26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crofford LJ, Rowbotham MC, Mease PJ, Russell IJ, Dworkin RH, Corbin AE, Young JP, Jr, LaMoreaux LK, Martin SA, Sharma U, Pregabalin 1008-105 Study Group Pregabalin for the treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1264–73. doi: 10.1002/art.20983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Freynhagen R, Strojek K, Griesing T, Whalen E, Balkenohl M. Efficacy of pregabalin in neuropathic pain evaluated in a 12-week, randomised, double-blind, multicentre, placebo- controlled trial of flexible- and fixed-dose regimens. Pain. 2005;115:254–63. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richter RW, Portenoy R, Sharma U, Lamoreaux L, Bockbrader H, Knapp LE. Relief of painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy with pregabalin: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Pain. 2005;6:253–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siddall PJ, Cousins MJ, Otte A, Griesing T, Chambers R, Murphy TK. Pregabalin in central neuropathic pain associated with spinal cord injury: a placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 2006;67:1792–800. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000244422.45278.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Seventer R, Feister HA, Young JP, Jr, Stoker M, Versavel M, Rigaudy L. Efficacy and tolerability of twice-daily pregabalin for treating pain and related sleep interference in postherpetic neuralgia: a 13-week, randomized trial. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22:375–84. doi: 10.1185/030079906x80404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Backonja M, Beydoun A, Edwards KR, Schwartz SL, Fonseca V, Hes M, LaMoreaux L, Garofalo E. Gabapentin for the symptomatic treatment of painful neuropathy in patients with diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280:1831–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.21.1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rowbotham M, Harden N, Stacey B, Bernstein P, Magnus-Miller L. Gabapentin for the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280:1837–42. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.21.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rice AS, Maton S, Postherpetic Neuralgia Study Group Gabapentin in postherpetic neuralgia: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled study. Pain. 2001;94:215–24. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00407-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simpson DA. Gabapentin and Venlafaxine for the treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis. 2001;3:53–62. doi: 10.1097/00131402-200112000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bone M, Critchley P, Buggy DJ. Gabapentin in postamputation phantom limb pain: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2002;27:481–6. doi: 10.1053/rapm.2002.35169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Serpel MG, Neuropathic Pain Study Group Gabapentin in neuropathic pain syndromes: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Pain. 2002;99:557–66. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00255-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Caraceni A, Zecca E, Bonezzi C, Arcuri E, Yaya Tur R, Maltoni M, Visentin M, Gorni G, Martini C, Tirelli W, Barbieri M, De Conno F. Gabapentin for neuropathic cancer pain: a randomized controlled trial from the Gabapentin Cancer Pain Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2909–17. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hahn K, Arendt G, Braun JS, von Giesen HJ, Husstedt IW, Maschke M, Straube ME, Schielke E, German Neuro-AIDS Working Group A placebo-controlled trial of gabapentin for painful HIV-associated sensory neuropathies. J Neurol. 2004;251:1260–6. doi: 10.1007/s00415-004-0529-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Levendoglu F, Ogun CO, Ozerbil O, Ogun TC, Ugurlu H. Gabapentin is a first line drug for the treatment of neuropathic pain in spinal cord injury. Spine. 2004;29:743–51. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000112068.16108.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van de Vusse AC, Stomp-van den Berg SG, Kessels AH, Weber WE. Randomised controlled trial of gabapentin in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome type 1 [ISRCTN84121379. BMC Neurol. 2004;4:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-4-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arnold LM, Goldenberg DL, Stanford SB, Lalonde JK, Sandhu HS, Keck PE, Jr, Welge JA, Bishop F, Stanford KE, Hess EV, Hudson JI. Gabapentin in the treatment of fibromyalgia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:1336–44. doi: 10.1002/art.22457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kimos P, Biggs C, Mah J, Heo G, Rashiq S, Thie NM, Major PW. Analgesic action of gabapentin on chronic pain in the masticatory muscles: a randomized controlled trial. Pain. 2007;127:151–60. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gorson KC, Schott C, Herman R, Ropper AH, Rand WM. Gabapentin in the treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy: a placebo controlled, double blind, crossover trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;66:251–2. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.66.2.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pandey CK, Bose N, Garg G, Singh N, Baronia A, Agarwal A, Singh PK, Singh U. Gabapentin for the treatment of pain in guillain-barre syndrome: a double-blinded, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Anesth Analg. 2002;95:1719–23. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200212000-00046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pandey CK, Raza M, Tripathi M, Navkar DV, Kumar A, Singh UK. The comparative evaluation of gabapentin and carbamazepine for pain management in Guillain-Barre syndrome patients in the intensive care unit. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:220–5. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000152186.89020.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Perez HET, Sanchez GF. Gabapentin therapy for diabetic neuropathic pain (letter) Am J Med. 2000;108:689. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00398-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tai Q, Kirshblum S, Chen B, Millis S, Johnston M, DeLisa JA. Gabapentin in the treatment of neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, crossover trial. J Spinal Cord Med. 2002;25:100–5. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2002.11753609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gilron I, Bailey JM, Tu D, Holden RR, Weaver DF, Houlden RL. Morphine, gabapentin, or their combination for neuropathic pain. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1324–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Freynhagen R, Busche P, Konrad C, Balkenohl M. Effectiveness and time to onset of pregabalin in patients with neuropathic pain. Schmerz. 2006;20:285–92. doi: 10.1007/s00482-005-0449-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Keskinbora K, Pekel AF, Aydinli I. Comparison of efficacy of gabapentin and amitriptyline in the management of peripheral neuropathic pain. Agri. 2006;18:34–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Anon. Lidocaine 5% plaster (Versatis) Scottish Medicines Consortium, December 2006. No (334/06.

- 55.Moore RA, Derry S, McQuay HJ. Indirect comparison of interventions using published randomised trials: systematic review of PDE-5 inhibitors for erectile dysfunction. BMC Urol. 2005;5:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2490-5-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Crofford L, Simpson S, Young J, Haig G, Barrett J. Fibromyalgia relapse evaluation and efficacy for durability of meaningful relief (FREEDOM) trial: A 6-month, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of treatment with pregabalin. J Pain. 2007;8:S24. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McQuay HJ, Derry S, Moore RA, Poulain P, Legout V. Enriched enrolment with randomised withdrawal (EERW): time for a new look at clinical trial design in chronic pain. Pain. 2008;135:217–20. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.01.014. February 5 Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chalmers I. Comparing like with like: some historical milestones in the evolution of methods to create unbiased comparison groups in therapeutic experiments. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:1156–64. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.5.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shafer S. The importance of dose-response in study design. Anesth Analg. 1999;89:805. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199909000-00064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.French JA, Kugler AR, Robbins JL, Knapp LE, Garofalo EA. Dose-response trial of pregabalin adjunctive therapy in patients with partial seizures. Neurology. 2003;60:1631–7. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000068024.20285.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bech P. Dose-response relationship of pregabalin in patients with Generalized Anxiety Disorder. A pooled analysis of four Placebo-controlled Trials. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2007;40:163–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-984400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Leber PD, Davis CS. Threats to the validity of clinical trials employing enrichment strategies for sample selection. Control Clin Trials. 1998;19:178–87. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(97)00118-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]