Abstract

Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF), a proinflammatory cytokine, is implicated in many aspects of tumor progression, including cell proliferation, invasion, and angiogenesis. We asked if MIF expression predicts survival and if it is associated with angiogenesis and cell invasion in osteosarcoma. We performed immunohistochemistry for MIF expression in prechemotherapy biopsy specimens of 58 patients with osteosarcoma. To investigate the role of MIF in angiogenesis, microvessel density was measured and compared with MIF expression. We also treated osteosarcoma cell lines (U2-OS and MG63) with MIF and measured vascular endothelial growth factor, a potent proangiogenic factor, by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. To study the role of MIF in cell invasion, Boyden chamber assay was performed after knockdown of MIF by short interfering RNA. MIF independently predicted overall survival and metastasis-free survival. MIF expression correlated with microvessel density and induced a dose-dependent increase in vascular endothelial growth factor. Knockdown of MIF by short interfering RNA resulted in decreased cell invasion. These results suggest MIF could serve as a prognostic marker and a potential therapeutic target for osteosarcoma.

Level of Evidence: Level II, prognostic study. See the Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

Osteosarcoma is the most common malignant tumor of bone characterized by its high metastatic potential. Approximately 80% of patients with osteosarcoma have clinically detectable or micrometastatic disease at the time of diagnosis [15, 27]. Despite the increase in survival rates with advances in combination chemotherapy and surgery, patients presenting with metastatic osteosarcoma still have a poor prognosis with a 5-year survival rate of less than 30% [5, 8]. Understanding the molecular events that drive the osteosarcoma progression and metastatic process would facilitate the development of better treatment and identification of molecular prognostic factors in osteosarcoma [5, 15].

Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) is an proinflammatory cytokine that plays an important role in the immune system [19]. MIF has recently been implicated in carcinogenesis of various types of tumors [6, 18, 22, 28]. MIF contributes to many aspects of tumor progression, including cell proliferation, survival, invasion of normal tissue, and tumor-associated angiogenesis [6, 18, 21, 23, 28]. In hepatocellular carcinoma, MIF stimulates angiogenesis and tumor cell migration [23]. MIF increases cell survival and angiogenesis in colon cancer and glioblastoma [1, 20, 29]. MIF predicts survival in malignancies of the liver, lung, prostate, and colon [9, 16, 22, 23, 28].

We first asked whether the expression of MIF predicts the development of metastasis and survival in osteosarcoma. We then asked whether MIF is associated with the tumor-progressive effect of angiogenesis and cell invasion in osteosarcoma.

Materials and Methods

Of the 135 patients with high-grade osteosarcoma treated at our institution between 1996 and 2002, we retrospectively identified 58 patients whose prechemotherapy incisional biopsy specimens were available for analysis. We reviewed the patients’ medical charts to record age at diagnosis, gender, histologic subtype, and location of primary disease. There were 37 males and 21 females with an average age of 22.4 years (range, 4–81 years). The location of the tumor was the distal femur in 27 patients; proximal tibia in 11; proximal femur in five; pelvis in five; proximal humerus in three; shaft of femur in two; proximal fibula in two; and scapula, distal tibia, and distal radius in one patient each. We collected tumor specimens after obtaining the patient’s informed consent in accordance with the institutional guidelines.

The treatment regimen included open biopsy followed by neoadjuvant chemotherapy and primary resection. The surgical stages of primary bone tumors according to the Musculoskeletal Tumor Society System [4] were Stage IIB in 53 patients and Stage III in five. Histologic types were osteoblastic in 38 patients, chondroblastic in seven, fibroblastic in six, mixed in five, and telangiectatic in two. All patients received neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy. We graded the effect of preoperative chemotherapy according to the criteria of Huvos [24]. Patients with Grade III and IV were considered good responders. There were 30 good responders and 28 poor responders. The operative treatments consisted of 55 limb salvage operations and three amputations. Surgical margins were wide in 49 cases, marginal in five, and intralesional in four. We defined the overall survival as the time from diagnosis to the date of either death or the last visit. The metastasis-free survival was defined as the time from diagnosis until the development of metastasis. If the patients had metastasis at diagnosis, we considered the metastasis at time 0. The minimum followup was 12 months (mean, 42 months; range, 12–110 months). The average followup of the survivors was 50 months. During the followup period, local recurrence occurred in 11 patients and distant metastasis developed in 25 patients. Sixteen of the 58 patients died of disease, 37 patients showed no evidence of disease, and five remained alive with disease at the last followup.

We used prechemotherapy incisional biopsy specimens to analyze expression of MIF by immunohistochemical analysis. Four-micrometer sections embedded in paraffin were deparaffinized using xylene at room temperature and then gradually rehydrated in alcohol solution. We performed antigen retrieval by pretreatment of the slides in citrate buffer. For quenching of endogenous peroxidase activity, the tissue slides were incubated in 3% hydrogen peroxide solution in methanol and then rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline. To suppress nonspecific antigen-antibody binding, we treated tissues with a blocking solution of 10% nonimmune serum for 1 hour at 4°C. The sections were then incubated overnight at 4°C with mouse monoclonal antibody of MIF (Santa-Cruz Biotechnology, Santa-Cruz, CA) and stained by the avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex method using Vectastain ABC kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). The color reaction was developed for 5 minutes in 3,3-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride and hydrogen peroxide in phosphate-buffered saline followed by counterstaining with Mayer’s hematoxylin (Sigma, St Louis, MO). We interpreted the staining reactions with parallel-processed control slides consisting of hepatocellular carcinoma tissue previously shown to express MIF as the positive control and negative control obtained after replacing primary antibody with Tris-buffered saline [23]. The expression of MIF was evaluated by two investigators (KWN, KCM) without knowledge of the patients’ clinical information. The proportion of positively stained cells among tumor cells was graded into groups of high and low expression with a cutoff value of 50%. We analyzed the degree of angiogenesis by the number of microvessels in the specimen using the method described previously [11, 26]. Of the 58 specimens used for MIF expression by immunohistochemistry, 47 specimens were immunostained with anti-CD34 antibody (Biogenex, San Ramon, CA). Eleven specimens were not available for microvessel density analysis. After scanning at ×40 magnification to find the areas showing the most intense vascularization, we examined areas of greatest vessel density under ×100 magnification and counted them. Microvessel density for each specimen was expressed as the average number of vessels per ×100 field from three nonoverlapping microscopic fields [11].

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is the most representative and potent angiogenic factor in the progression of tumor angiogenesis [10]. To detect whether MIF contributes to the production of VEGF in osteosarcoma cells, we measured VEGF in culture supernatants of U2-OS and MG63 osteosarcoma cell lines by using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (hVEGF ELISA kit; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). The cells were cultured at a density of 5 × 104 cells in 24-well plates in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum for 24 hours and then cultured in medium with recombinant MIF (R&D Systems) concentrations of 0, 10, 20, 40, 80, and 160 ng/mL for 24 hours. We collected the supernatants of cultured cells and centrifuged them at 300 g for 5 minutes to remove debris. The ELISA was performed following the instructions of the manufacturer.

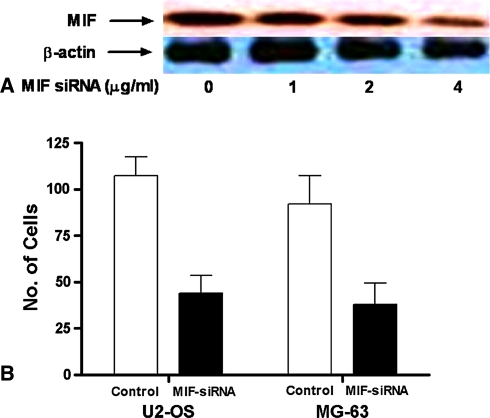

To study the functional role of MIF in osteosarcoma, we used short interfering RNAs (siRNAs) to downregulate the expression of MIF. The siRNA sequences used to target MIF were 5′-ACACCAAGCUGCCCCGCGCdTdT-3′ and 5′-GCGCGGGGCACGUUGGUGUdTdT-3′ [30]. A fluorescein double-stranded RNA (BLOCK-iT Fluorescent Oligo; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was used as a control siRNA. We transfected the U2-OS and SaOS-2 cells in 100-mm culture dishes containing RPMI 1640 with 10% fetal bovine serum with the MIF siRNA or the control siRNA using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). To assess the efficiency of MIF silencing, Western blot analysis was performed. Briefly, we subjected proteins from a total cell extract (10 μg/lane) to Tris-Glycine gel (Invitrogen) electrophoresis and transferred them to nitrocellulose membranes (Hybond; Amersham, Piscataway, NJ). The membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk and incubated with mouse anti-MIF antibody. We used anti-β-actin antibody as a loading control (Sigma). These blots were then reacted with a horseradish peroxidase conjugated antimouse secondary antibody (Pierce, Rockford, IL). We visualized the immunoreactive proteins using ECL detection reagents (Supersignal West Dura, Pierce, IL). The most effective silencing of MIF was achieved at 4 μM of siRNA for a transfection time of 48 hours. Hence, this optimal scheme was used for the Boyden chamber assay.

To study the role of MIF in osteosarcoma cell invasion, we evaluated the invasive properties of osteosarcoma cells in the Boyden chamber cell invasion assay (Neuro Probe Inc, Gaithersburg, MD) [14]. U2-OS and MG-63cells (2 × 106 cells/well) transfected with either MIF siRNA or control siRNA were placed in the upper wells of a transwell chamber in which an 8-μm pore membrane was precoated 1% gelatin overnight. We filled the lower wells with medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, which acted as a chemoattractant. The chamber was incubated for 4 hours at 37°C to allow cells to migrate from the upper chamber toward the lower chamber. After incubation, we removed the noninvading cells from the upper surface of the filter by scrubbing. The number of invading cells, which were stained with Diff-Quik stain solution (Dade Behring Inc, Newark, DE), were counted under a light microscope.

We determined overall survival and metastasis-free survival using the Kaplan-Meier method [12]. We determined differences in survival rate with age at diagnosis, gender, histologic subtype, location of primary disease, and response to chemotherapy with the log-rank test. Factors influencing survival rate were then analyzed in a multivariate Cox regression analysis to determine independent variables predicting survival. Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the microvessel density between the low and high MIF expression groups. We also used Mann-Whitney U test to compare the number of cells migrated in the transwell chamber assay between the MIF siRNA-transfected cells and the control cells. We performed all statistical analysis with SPSS software (version 12.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Results

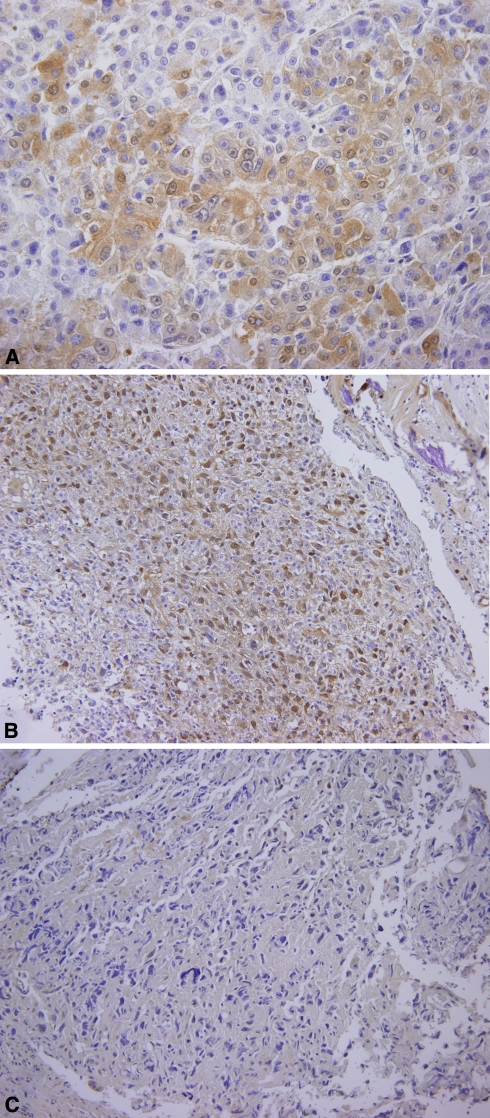

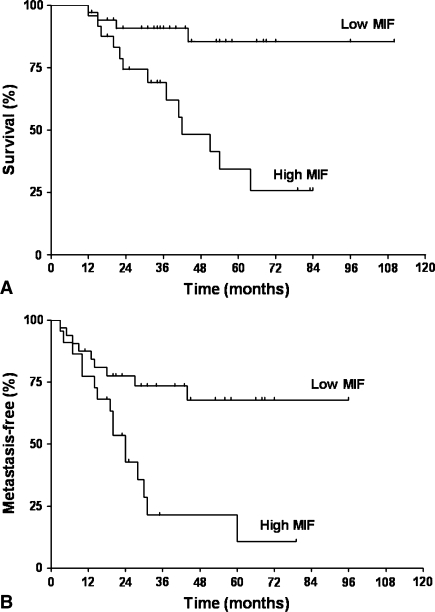

Of the 58 cases examined, 21 cases (36%) showed the MIF expression of more than 50% of the tumor cells (high expression) and 37 cases (64%) showed MIF expression of less than 50% (low expression) (Fig. 1). A high level of MIF expression was associated with worse overall survival (p < 0.001) and metastasis-free survival (p = 0.018) (Table 1; Fig. 2). Poor histologic response to chemotherapy negatively influenced overall survival (p < 0.001) and metastasis-free survival (p < 0.001). The level of MIF expression (overall survival, p = 0.004; metastasis-free survival, p = 0.014) and the histologic response to chemotherapy (overall survival, p = 0.043; metastasis-free survival, p = 0.001) independently predicted survival (Table 2).

Fig. 1A–C.

Representative sections show expression of migration inhibitory factor (MIF) by immunohistochemistry. (A) Positive control (hepatocellular carcinoma) shows strong cytoplasmic expression of MIF (Stain, diaminobenzidine and Meyer’s hematoxylin; original magnification, ×400). (B) A representative case of high MIF expression is shown (Stain, diaminobenzidine and Meyer’s hematoxylin; original magnification, ×200). (C) A representative case of low MIF expression is shown (Stain, diaminobenzidine and Meyer’s hematoxylin; original magnification, ×200).

Table 1.

Five-year survival rate according to MIF expression and histologic response

| Factors | Overall survival (%)* | p value | Metastasis-free survival (%)* | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIF expression | Low | 88.0 ± 6.8 | < 0.001 | 68.0 ± 9.3 | 0.018 |

| High | 35.0 ± 12.0 | 21.0 ± 10.0 | |||

| Histologic response to chemotherapy | Good | 83.8 ± 9.3 | < 0.001 | 78.2 ± 8.8 | < 0.001 |

| Poor | 49.3 ± 10.9 | 22.5 ± 9.0 | |||

* Mean ± standard deviation; MIF = migration inhibitory factor.

Fig. 2A–B.

(A) A Kaplan-Meier overall survival curve is illustrated according to the level of migration inhibitory factor (MIF) expression. Patients with high MIF-expressing tumors had worse (p < 0.0001) overall survival than those with low MIF-expressing tumors. (B) A Kaplan-Meier metastasis-free survival curve is illustrated according to the level of MIF expression. There was a trend (p = 0.018) toward increased metastasis in patients with high MIF expression.

Table 2.

Cox multivariate analysis

| Factors | Overall survival | Metastasis-free survival | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative risk | 95% CI | p value | Relative risk | 95% CI | p value | ||

| MIF expression | Low | 1 | 0.004 | 1 | 0.014 | ||

| High | 6.3 | 1.8–22.2 | 2.9 | 1.2–6.6 | |||

| Histologic response to chemotherapy | Good | 1 | 0.043 | 1 | 0.001 | ||

| Poor | 3.7 | 1.0–13.1 | 5.3 | 2.0–14.3 | |||

CI = confidence interval; MIF = migration inhibitory factor.

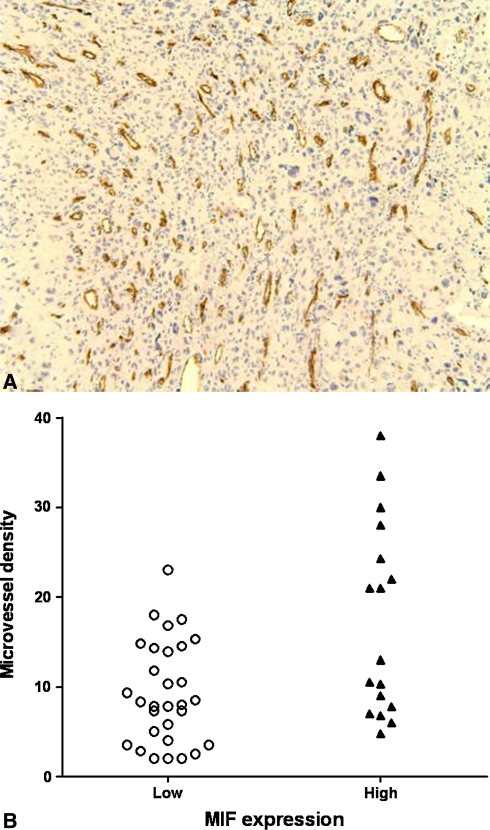

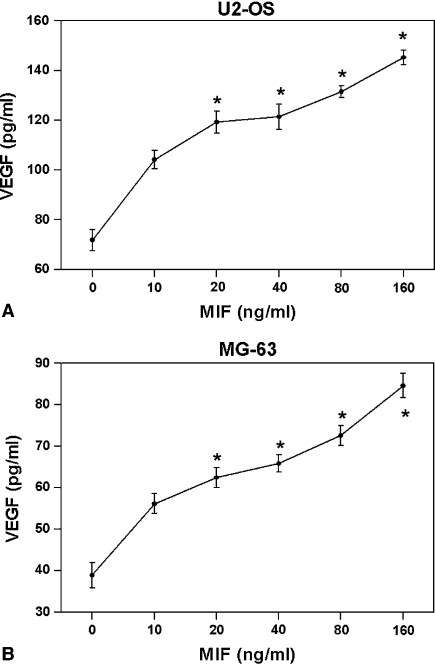

Microvessel density was higher in specimens with high MIF expression (p = 0.016) (Fig. 3). VEGF concentration in the supernatants of U2-OS and MG-63 cells tended (not significantly so) increase after stimulation with MIF in a dose-dependent manner in both cell lines (Fig. 4). By Western blot the expression of MIF qualitatively appeared suppressed by MIF siRNA in a dose-dependent manner in U2-OS and SaOS-2 cell lines (Fig. 5A). The invasive ability of U2-OS and MG-63 cells decreased (p = 0.03 and p = 0.04, respectively) in MIF siRNA transfected cells (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 3A–B.

(A) A representative immunohistochemical staining of osteosarcoma specimen with anti-CD34 antibodies for microvessel density (MVD) quantification is shown (Stain, diaminobenzidine and Meyer’s hematoxylin; original magnification, ×100). (B) Specimens with high migration inhibitory factor (MIF) expression had higher (p = 0.016) MVD than those with low MIF expression.

Fig. 4A–B.

Migration inhibitory factor (MIF) induced the secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) by U2-OS (A) and MG63 (B) cells in a dose-dependent manner. *p < 0.05 when compared with 0 ng/mL of MIF.

Fig. 5A–B.

(A) Migration inhibitory factor (MIF) short interfering RNA (siRNA) suppressed MIF expression in a dose-dependent manner. Representative result of three experiments is shown. (B) Knockdown by MIF siRNA decreased the migration of U2-OS (p = 0.03) and MG63 cells (p = 0.04).

Discussion

MIF predicts survival in some tumors and contributes to multiple aspects of tumor progression in several types of malignancies. We therefore asked whether the level of MIF expression could predict survival outcome in patients with osteosarcoma. We also intended to determine the role of MIF tumor progression; namely, angiogenesis and cell invasion in osteosarcoma.

We note several limitations in our study. First, the survival analyses in this study were performed in a nonrandomized, retrospectively selected group of patients. Although the relatively low incidence of osteosarcoma compared with that of common carcinomas makes such a study difficult, a prospective and possibly randomized study would further clarify the prognostic role of MIF in predicting survival in osteosarcoma. Another limitation is the lack of in vivo studies with regard to identifying the role of MIF in osteosarcoma. Immortalized osteosarcoma cell lines were used in the cell experiments of this study. Osteosarcoma cells isolated from patient tissues could have reflected a more in vivo situation. Comparison of MIF expression between matched primary and metastatic tumor specimens would have made the association of MIF expression with metastasis clearer. Moreover, in vivo metastasis assays using mouse models would further verify the role of MIF in metastasis of osteosarcoma. The use of only high-grade osteosarcoma samples might have skewed the association of MIF expression and metastasis. The addition of low-grade osteosarcoma samples in the experiments would have further strengthened the association of MIF expression and metastasis.

MIF, one of the earliest cytokines described, plays a major role in the control of host inflammatory and immune response. MIF is overexpressed in a large variety of human malignancies such as melanoma, breast carcinoma, colon carcinoma, glioblastoma, nonsmall cell lung carcinoma, and hepatocellular carcinoma [6, 16, 17, 23, 28, 29]. Several of these studies [6, 16, 23, 28] demonstrated MIF expression correlated with tumor aggressiveness and metastatic potential. In hepatocellular carcinoma, a high level of MIF expression correlated with worse disease-free survival [6] and MIF stimulated angiogenesis and metastasis by promoting angiogenic factors and tumor cell migration [23]. Increased expression of MIF is associated with prostate cancer metastasis [16]. MIF expression is increased and correlates with VEGF expression in glioblastoma [1]. Our findings correspond with those in previous studies on various carcinomas, suggesting an important role of MIF in osteosarcoma progression. To improve the choice of therapeutic strategy, the mechanism by which MIF promotes angiogenesis and invasion needs to be clarified. In an experiment using murine colon cancer cell lines, MIF promoted invasion and metastasis through the Rho-dependent pathway [25]. Moreover, further studies are necessary to elucidate if MIF contributes to other steps of the multistep tumorigenic process.

Few factors seem to predict survival from osteosarcoma [3, 5, 15]. The most commonly cited is the degree of histologic response to preoperative chemotherapy [2, 7, 15]. However, poor responders to chemotherapy cannot be determined until surgery, which takes 2 to 3 months. Our experience suggests development of metastasis is not uncommon even among good responders. Intensifying chemotherapy increases in histologic response but not survival [13]. Our data from prechemotherapy biopsy specimens suggests MIF, along with histologic response to chemotherapy, independently predicts survival.

Our data suggest increased MIF expression predicts increased risk of metastasis and MIF correlates with angiogenesis and cell invasion in osteosarcoma. MIF could therefore be explored as a prognostic marker for osteosarcoma and may serve as a potential therapeutic target.

Footnotes

One or more of the authors (JHO, HSK) have received funding from a grant (No 02-2006-020) from the Seoul National University Hospital Research Fund, Korea.

Each author certifies that his or her institution has approved the human protocol for this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

References

- 1.Bacher M, Schrader J, Thompson N, Kuschela K, Gemsa D, Waeber G, Schlegel J. Up-regulation of macrophage migration inhibitory factor gene and protein expression in glial tumor cells during hypoxic and hypoglycemic stress indicates a critical role for angiogenesis in glioblastoma multiforme. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:11–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Davis AM, Bell RS, Goodwin PJ. Prognostic factors in osteosarcoma: a critical review. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:423–431. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Ek ET, Dass CR, Contreras KG, Choong PF. Pigment epithelium-derived factor overexpression inhibits orthotopic osteosarcoma growth, angiogenesis and metastasis. Cancer Gene Ther. 2007;14:616–626. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Enneking W. Staging musculoskeletal tumors. In: Enneking W, ed. Musculoskeletal Tumor Surgery. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1983:69–88.

- 5.Gorlick R, Anderson P, Andrulis I, Arndt C, Beardsley GP, Bernstein M, Bridge J, Cheung NK, Dome JS, Ebb D, Gardner T, Gebhardt M, Grier H, Hansen M, Healey J, Helman L, Hock J, Houghton J, Houghton P, Huvos A, Khanna C, Kieran M, Kleinerman E, Ladanyi M, Lau C, Malkin D, Marina N, Meltzer P, Meyers P, Schofield D, Schwartz C, Smith MA, Toretsky J, Tsokos M, Wexler L, Wigginton J, Withrow S, Schoenfeldt M, Anderson B. Biology of childhood osteogenic sarcoma and potential targets for therapeutic development: meeting summary. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:5442–5453. [PubMed]

- 6.Hira E, Ono T, Dhar DK, El-Assal ON, Hishikawa Y, Yamanoi A, Nagasue N. Overexpression of macrophage migration inhibitory factor induces angiogenesis and deteriorates prognosis after radical resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;103:588–598. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Hoang BH, Kubo T, Healey JH, Sowers R, Mazza B, Yang R, Huvos AG, Meyers PA, Gorlick R. Expression of LDL receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) as a novel marker for disease progression in high-grade osteosarcoma. Int J Cancer. 2004;109:106–111. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Kager L, Zoubek A, Potschger U, Kastner U, Flege S, Kempf-Bielack B, Branscheid D, Kotz R, Salzer-Kuntschik M, Winkelmann W, Jundt G, Kabisch H, Reichardt P, Jurgens H, Gadner H, Bielack SS. Primary metastatic osteosarcoma: presentation and outcome of patients treated on neoadjuvant Cooperative Osteosarcoma Study Group protocols. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2011–2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Kamimura A, Kamachi M, Nishihira J, Ogura S, Isobe H, Dosaka-Akita H, Ogata A, Shindoh M, Ohbuchi T, Kawakami Y. Intracellular distribution of macrophage migration inhibitory factor predicts the prognosis of patients with adenocarcinoma of the lung. Cancer. 2000;89:334–341. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Kaya M, Wada T, Akatsuka T, Kawaguchi S, Nagoya S, Shindoh M, Higashino F, Mezawa F, Okada F, Ishii S. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression in untreated osteosarcoma is predictive of pulmonary metastasis and poor prognosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:572–577. [PubMed]

- 11.Kreuter M, Bieker R, Bielack SS, Auras T, Buerger H, Gosheger G, Jurgens H, Berdel WE, Mesters RM. Prognostic relevance of increased angiogenesis in osteosarcoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:8531–8537. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Laverdiere C, Hoang BH, Yang R, Sowers R, Qin J, Meyers PA, Huvos AG, Healey JH, Gorlick R. Messenger RNA expression levels of CXCR4 correlate with metastatic behavior and outcome in patients with osteosarcoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:2561–2567. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Lewis IJ, Nooij MA, Whelan J, Sydes MR, Grimer R, Hogendoorn PC, Memon MA, Weeden S, Uscinska BM, van Glabbeke M, Kirkpatrick A, Hauben EI, Craft AW, Taminiau AH. Improvement in histologic response but not survival in osteosarcoma patients treated with intensified chemotherapy: a randomized phase III trial of the European Osteosarcoma Intergroup. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:112–128. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Luu HH, Zhou L, Haydon RC, Deyrup AT, Montag AG, Huo D, Heck R, Heizmann CW, Peabody TD, Simon MA, He TC. Increased expression of S100A6 is associated with decreased metastasis and inhibition of cell migration and anchorage independent growth in human osteosarcoma. Cancer Lett. 2005;229:135–148. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Marina N, Gebhardt M, Teot L, Gorlick R. Biology and therapeutic advances for pediatric osteosarcoma. Oncologist. 2004;9:422–441. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Meyer-Siegler K, Hudson PB. Enhanced expression of macrophage migration inhibitory factor in prostatic adenocarcinoma metastases. Urology. 1996;48:448–452. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Meyer-Siegler KL, Iczkowski KA, Vera PL. Further evidence for increased macrophage migration inhibitory factor expression in prostate cancer. BMC Cancer. 2005;5:73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Meyer-Siegler KL, Leifheit EC, Vera PL. Inhibition of macrophage migration inhibitory factor decreases proliferation and cytokine expression in bladder cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2004;4:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Mitchell RA. Mechanisms and effectors of MIF-dependent promotion of tumourigenesis. Cell Signal. 2004;16:13–19. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Munaut C, Boniver J, Foidart JM, Deprez M. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) expression in human glioblastomas correlates with vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2002;28:452–460. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Nishihira J, Ishibashi T, Fukushima T, Sun B, Sato Y, Todo S. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF): its potential role in tumor growth and tumor-associated angiogenesis. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2003;995:171–182. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Ren Y, Law S, Huang X, Lee PY, Bacher M, Srivastava G, Wong J. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor stimulates angiogenic factor expression and correlates with differentiation and lymph node status in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2005;242:55–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Ren Y, Tsui HT, Poon RT, Ng IO, Li Z, Chen Y, Jiang G, Lau C, Yu WC, Bacher M, Fan ST. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor: roles in regulating tumor cell migration and expression of angiogenic factors in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2003;107:22–29. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Rosen G, Caparros B, Huvos AG, Kosloff C, Nirenberg A, Cacavio A, Marcove RC, Lane JM, Mehta B, Urban C. Preoperative chemotherapy for osteogenic sarcoma: selection of postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy based on the response of the primary tumor to preoperative chemotherapy. Cancer. 1982;49:1221–1230. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Sun B, Nishihira J, Yoshiki T, Kondo M, Sato Y, Sasaki F, Todo S. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor promotes tumor invasion and metastasis via the Rho-dependent pathway. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:1050–1058. [PubMed]

- 26.Vermeulen PB, Gasparini G, Fox SB, Colpaert C, Marson LP, Gion M, Belien JA, de Waal RM, Van Marck E, Magnani E, Weidner N, Harris AL, Dirix LY. Second international consensus on the methodology and criteria of evaluation of angiogenesis quantification in solid human tumours. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:1564–1579. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Ward WG, Mikaelian K, Dorey F, Mirra JM, Sassoon A, Holmes EC, Eilber FR, Eckardt JJ. Pulmonary metastases of stage IIB extremity osteosarcoma and subsequent pulmonary metastases. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:1849–1858. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.White ES, Flaherty KR, Carskadon S, Brant A, Iannettoni MD, Yee J, Orringer MB, Arenberg DA. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor and CXC chemokine expression in non-small cell lung cancer: role in angiogenesis and prognosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:853–860. [PubMed]

- 29.Wilson JM, Coletta PL, Cuthbert RJ, Scott N, MacLennan K, Hawcroft G, Leng L, Lubetsky JB, Jin KK, Lolis E, Medina F, Brieva JA, Poulsom R, Markham AF, Bucala R, Hull MA. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor promotes intestinal tumorigenesis. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1485–1503. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Yao K, Shida S, Selvakumaran M, Zimmerman R, Simon E, Schick J, Haas NB, Balke M, Ross H, Johnson SW, O’Dwyer PJ. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor is a determinant of hypoxia-induced apoptosis in colon cancer cell lines. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:7264–7272. [DOI] [PubMed]