Abstract

Osteosarcoma (OS) is a primary malignant bone tumor with a high propensity for local recurrence and distant metastasis. We previously showed a secreted, dominant-negative LRP5 receptor (DNLRP5) suppressed in vitro migration and invasion of the OS cell line SaOS-2. Therefore, we hypothesized DNLRP5 also has in vivo antitumor activity against OS. We used the 143B cell line as a model to study the effect of DNLRP5 by stable transfection. Inhibition of Wnt signaling by DNLRP5 was verified by a reduction in TOPFLASH luciferase activity. In soft agar, DNLRP5-transfected 143B cells formed fewer and smaller colonies than control transfected cells. DNLRP5 transfection reduced in vivo tumor growth of 143B cells in nude mice. DNLRP5 also decreased in vitro cellular motility in a scratch wound assay. In a spontaneous pulmonary metastasis model, DNLRP5 reduced both the size and number of lung metastatic nodules. The reduction in cellular invasiveness by DNLRP5 was associated with decreased expression of matrix metalloproteinase-2, N-cadherin, and Snail. Our data suggest canonical Wnt/LRP5 signaling reflects an important underlying mechanism of OS progression. Therefore, strategies to suppress LRP5-mediated signaling in OS cells may lead to a reduction in local or systemic disease burden.

Introduction

Osteosarcoma (OS) is the most common primary malignancy of bone in children and the fifth most common malignancy among adolescents and young adults. Currently, despite intensive chemotherapy and adequate surgical resection, 30% to 40% of patients still die of their disease, mainly from distant metastasis to the lung [7]. Detailed mechanisms of tumorigenicity and metastasis need to be elucidated to identify potential targeted treatment strategies.

The canonical Wnt signaling pathway plays important roles during embryonic development and oncogenesis [5, 22]. Binding of Wnt ligands to the membrane receptors Frizzled and low-density lipoprotein receptor related protein 5 (LRP5) leads to inhibition of GSK3β in a cytoplasmic complex comprising adenomatous polyposis coli, Axin, GSK3β, and β-catenin. This inhibition leads to hypophosphorylation and stabilization of β-catenin, resulting in cytosolic accumulation and translocation of β-catenin into the nucleus. After being translocated to the nucleus, β-catenin forms complexes with the T-cell factor (TCF)/lymphocyte-enhancing factor (LEF) family of transcription factors to activate Wnt-responsive genes such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), c-Myc, cyclin D1, and so on [5, 17].

LRP5, a single-pass transmembrane protein, is required as a coreceptor for canonical Wnt-mediated signaling [23]. In addition, LRP5 serves as a major regulator of bone homeostasis [13, 21]. In transgenic mice, loss of LRP5 markedly reduces the formation of mammary tumors, suggesting an oncogenic function for this Wnt receptor [15]. We previously reported expression of LRP5 mRNA in OS tissue correlated with the development of metastatic disease and a worse event-free survival [12]. Recently, dominant-negative LRP5 plasmid (DNLRP5) transfection reportedly decreased tumorigenicity of prostate cancer PC-3 cells and reversed the epithelial to mesenchymal transition in PC-3 and SaOS-2 cells [9, 27]. Because SaOS-2 cells cannot form in vivo tumor and metastasis, in this study, we used the 143B cell line in an orthotopic xenograft model.

We asked whether DNLRP5 has in vivo antitumor and antimetastasis activity in OS. We specifically hypothesized DNLRP5 has in vivo antitumor and antimetastatic activity in OS. Secondarily we hypothesized DNLRP5 decreases in vitro cell growth, cancer cell migration capacity, and invasiveness-associated biomarkers.

Materials and Methods

To test these hypotheses, we established stable 143B cell lines expressing control vector and DNLRP5 expression construct. The antitumor and antimetastatic activity of DNLRP5 measured as tumor growth rate and number of lung metastatic nodules was compared between vector control and DNLRP5 transfection groups. In vitro anchorage-independent cell growth was assessed by soft agar colony formation assay in vector control versus DNLRP5 transfection groups. Cell migration capacity examined by scratch healing assay was compared between control and DNLRP5 transfected 143B cell lines. Cancer invasiveness-associated markers such as MMP-2, N-cadherin, and Snail were evaluated in control and DNLRP5 tranfected cells by Western blot analysis of protein expression.

Normal human osteoblasts (NHOst) were obtained from the Clonetics® collection (Cambrex Corp, East Rutherford, NJ) and maintained in the OGM-Osteoblast Growth Medium (Cambrex Corp). OS cell lines Saos-2, 143B, MNNG/HOS, U2-OS, and MG-63 were from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA). OS cell lines 143.98.2 and OS160 were provided by Dr Richard Gorlick (Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, Bronx, NY). All OS cell lines were maintained in MEMα medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. PcDNA3.1 expression vector was obtained from Invitrogen. The Myc-tagged, secreted DNLRP5 (a generous gift from Dr Matthew Warman, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA) encoded the extracellular, ligand-binding domain of LRP5 (ΔTM) [8]. The TCF4 luciferase reporter (pTOPFLASH) plasmid was provided by Dr Marian Waterman (University of California, Irvine, CA). β-galactosidase plasmid was obtained from Invitrogen. We have not been successful in establishing an orthotopic model using the SaOS-2 cell line following the reported method by Dass et al. [6]. We speculate the growth and metastatic potential of SaOS-2 cells used by Dass et al. [6] may be different from our SaOS-2 cell line freshly obtained from ATCC. It may be important to compare the SaOS-2 cell line from Choong’s laboratory with our SaOS-2 line. In this study, we used the 143B cell line in an orthotopic xenograft model [16] of OS to evaluate the antitumor and antimetastatic effects of blocking LRP5 using the Myc-tagged DNLRP5 construct.

For stable transfection, 143B cells were plated at 3 × 105 cells per well in six-well plates and maintained in 37°C overnight. Cells were then transfected with DNLRP5 construct using lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. As a control, 143B cells were also transfected with PcDNA3.1 vector (Invitrogen). Transfected cells were then selected with G418 (800 μg/mL) starting 24 hours after transfection. All stable transfectants were pooled to avoid cloning artifacts.

Total RNA was isolated from OS cell lines using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time RT-PCR was performed and the fold change in LRP5 mRNA level in OS cell lines relative to NHOst cells was calculated as previously described [27]. PCR condition was as follows: 95°C for 5 minutes, 40 cycles of 30 seconds at 95°C, 30 seconds at 58°C, and 60 seconds at 72°C. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Western blot assay was performed as previously described [9]. Primary antibodies include anti-MMP-2 (Lab Vision, Fremont, CA), anti-N-cadherin (BD Bioscience, Bedford, MA), and anti-Snail and anti-β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). N-cadherin is a mesenchymal marker [4, 11] and Snail [1] is a transcription factor that promotes cancer metastasis.

Conditioned medium was collected in serum-free medium for 48 hours and concentrated x20 using Centricon filters (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Samples were applied to Bio-Rad zymogram gel containing 0.1% gelatin (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). After electrophoresis, gels were placed in 2.5% Triton X-100 buffer for 30 minutes at room temperature, incubated overnight at 37°C in zymography development buffer, and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue for 1 hour [27]. Gelatinolytic activity was visualized as clear bands against a blue background.

143B cells stably expressing PcDNA3.1 or DNLRP5 were seeded in six-well plates and incubated overnight at 37°C. Cells were transiently cotransfected with 4 μg pTOPFLASH reporter plasmid and 0.1 μg cytomegalovirus-β-galactosidase plasmid (Invitrogen) using lipofectamine 2000. Beta-galactosidase activity was used as a control for transfection efficiency in each sample. After 48 hours, cells were harvested and the luciferase and β-galactosidase activities were measured using the Bright-Glo luciferase assay system and β-galactosidase enzyme assay system, respectively (Promega, Madison, WI). The relative luciferase unit for each transfection was adjusted by β-galactosidase activity in the same sample.

Briefly, transfected cells were cultured in six-well plates at the density of 4 × 105 cells per well. After confluency, a wound was made across the well with a 200-μL pipette tip. The wound was photographed immediately and again at 24 hours using an inverted microscope (×10 magnification) to document cellular migration across the gap wound. The width of the gap was measured in five different fields and the average width was calculated. Each experiment was performed in duplicate with similar results.

For colony formation assay, soft agar assays were performed as previously described [27]. Cells were plated at 4000 cells per well in six-well plates in MEMα medium plus 10% FBS in 0.35% (w/v) agar on the top of a 0.8% agar bottom layer. Cells were fed weekly by the addition of 1.5 mL per well growth medium. After 2 weeks, colonies were imaged and counted under an inverted microscope (×100 magnification). Each colony contains more than 10 cells. The data represents means ± standard error of four independent wells.

For in vivo tumor growth and metastasis, 4-week-old NCR-nu/nu (nude) mice were obtained from Taconic (Germantown, NY). 143B cells stably transfected with control PcDNA3.1 or DNLRP5 expression constructs were injected subcutaneously into the right flank (1 × 106 cells/200 μL phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]). Tumor size was measured every 3 days with a caliper. On Day 21, all the mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation and flank tumors harvested. The tumor volume was calculated by the formula 1/6 π ab2 (π = 3.14, a = long axis and b = short axis of the tumor) [27]. Growth curves were plotted from the mean tumor volume ± standard error from 10 animals in each group.

For lung metastasis, PcDNA3.1 and DNLRP5 transfected 143B cells (3 × 105 cells/30 μL PBS) were injected percutaneously into left proximal tibia. Animals were euthanized 30 days after tibial injection. Lungs were then harvested, fixed in Bouin’s solution, and surface lung nodules were counted under a dissecting microscope. After fixation, sectioning of the lung, and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, the number of microscopic pulmonary nodules was determined by counting five low-powered fields (×10 magnification) from each slide and calculated as mean number of nodules per field.

We compared number of agar colonies, levels of mRNA expression, luciferase activity, and number of lung nodules between the two different transfection groups using Student’s t test. To determine significant tumor growth, we used a repeated-measures analysis of variance at the different time points. An additional posttest was performed to examine the difference in tumor size between PcDNA3.1 vector control and DNLRP5 transfection at each time point by using a Bonferroni method. All tests were two-sided.

Results

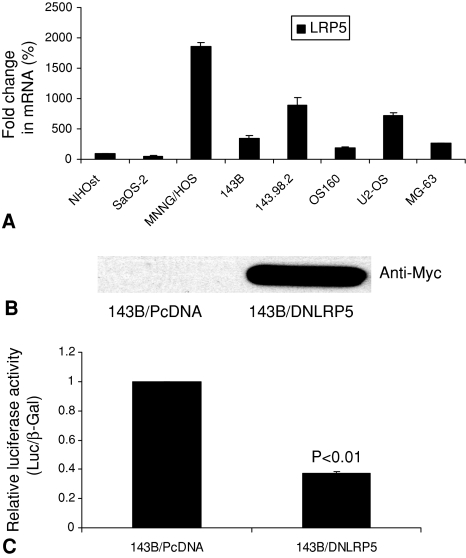

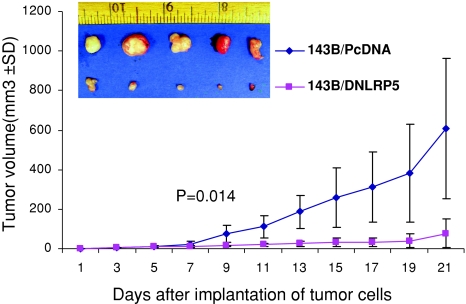

Our animal models supported the hypothesis that DNLRP5 has in vivo antitumor and antimetastatic activity in OS. We first compared endogenous mRNA level of the Wnt receptor LRP5 in normal osteoblast versus human OS cell lines. LRP5 mRNA expression was upregulated in six of seven human OS cell lines (MNNG/HOS, 143B, 143.98.2, OS160, U2OS, MG63) (all p < 0.05) (Fig. 1A). This result provides the rationale for using DNLRP5 to inhibit LRP5-mediated Wnt signaling in OS and to examine the in vivo antitumor and antimetastatic activity. DNLRP5 was successfully transfected into 143B cells to establish the stable cell line expressing DNLRP5 (Fig. 1B). DNLRP5 decreased TCF/LEF transcriptional activity (a hallmark of Wnt signaling) in 143B cells by 63% compared with that in control cells by TOPFLASH reporter assays (p = 0.0039) (Fig. 1C). Tumors formed by DNLRP5 transfected cells grew slower (p = 0.014) than those from control transfected cells, suggesting an inhibitory effect for DNLRP5 on OS tumorigenesis (Fig. 2). DNLRP5 transfected cells formed fewer (p = 0.0048) lung surface metastatic nodules than control cells (Fig. 3A). When examined by H&E staining under light microscopy, DNLRP5 transfected cells formed 81% fewer (p = 0.01) microscopic lung foci than vector control transfected cells (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 1A–C.

Expression of endogenous LRP5 in osteosarcoma (OS) cell lines and Wnt inhibitory effect of DNLRP5 are shown. (A) This graph shows LRP5 mRNA levels by real-time RT-PCR in NHOst compared with OS cell lines. (B) This Western blot shows expression of DNLRP5 protein in stably transfected 143 cells using an antibody against the Myc tag. (C) This graph shows reduced TOPFLASH TCF/LEF reporter activity in DNLRP5 versus control transfected cells.

Fig. 2.

DNLRP5-mediated inhibition of tumor growth is shown. A representative photograph of tumors harvested at 3 weeks after cell implantation (inset) and in vivo tumor growth curves for DNLRP5 transfection group versus vector control group (n = 10 mice in each group) show reduced tumorigenicity.

Fig. 3A–B.

DNLRP5-mediated antimetastatic activity is shown. (A) This graph shows reduced number of pulmonary nodules in the DNLRP5 transfected group compared with the vector control group (n = 10 mice in each group). A representative photograph of lungs harvested from each group (inset). (B) This graph shows a reduced number of microscopic pulmonary nodules in the DNLRP5 transfected group compared with the vector control group (n = 10 mice in each group). A representative photomicrograph of lungs harvested from the DNLRP5 and vector control transfection group (inset) (Stain, hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification, ×10).

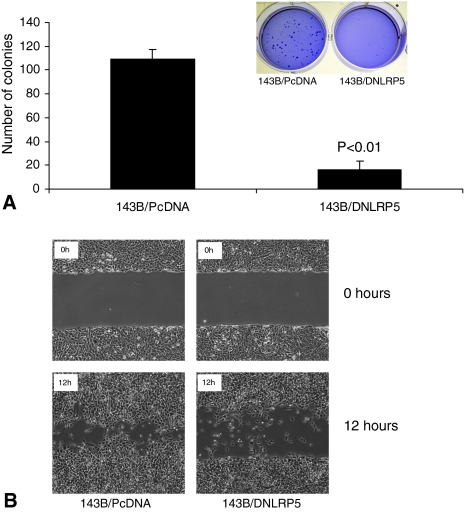

Reflecting decreased anchorage-independent growth of 143B cells in soft agar, DNLRP5 transfected 143B cells formed 85% fewer colonies (p = 0.007) than control transfected cells (Fig. 4A). In addition, colonies formed by DNLRP5-transfected cells were qualitatively smaller than those by control cells (Fig. 4A, inset).

Fig. 4A–B.

Inhibition of in vitro cell growth in soft agar and cell migration capacity by DNLRP5 is shown. (A) This graph shows the number of anchorage-independent colonies of DNLRP5 transfected versus vector control transfected 143B cells formed in soft agar. A representative photograph of soft agar colonies 2 weeks after cell seeding is shown (inset). (B) A photomicrograph of scratch wounds made in the transfected 143B cell layer shows reduced cellular motility in the DNLRP5 transfection group compared with the vector control group 24 hours after cell seeding.

DNLRP5 decreased the migration capacity of 143B cells. Twenty-four hours after a scratch wound was made in the monolayer, DNLRP5 transfected 143B cells exhibited less migration (p = 0.000001) into the wounded area when compared with control transfected cells (Fig. 4B).

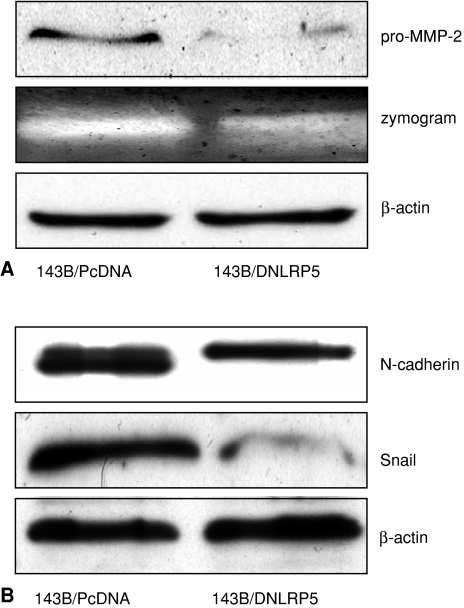

DNLRP5 decreased the expression of several cancer cell invasiveness markers in 143B cells. Pro-MMP-2 protein expression and proteolytic activity were qualitatively suppressed by DNLRP5 in 143B cells (Fig. 5A). Protein levels of N-cadherin and Snail were qualitatively downregulated by DNLRP5 transfection (Fig. 5B). We were unable to detect E-cadherin expression in 143B cells by Western blot analysis (data not shown).

Fig. 5A–B.

Reduction of expression of invasiveness-associated biomarkers by DNLRP5 is shown. (A) This Western blot shows reduced protein expression and proteolytic activity (zymogram) of pro-MMP-2 in DNLRP5 transfected 143B cells compared with vector control cells. Beta-actin was used as a loading control. (B) This Western blot shows reduced N-cadherin and Snail protein expression in DNLRP5 transfected cells compared with vector control cells. Beta-actin was used as a loading control.

Discussion

Our previous work demonstrated LRP5 receptor is commonly expressed in human OS and correlated with a worse disease-free survival in patients. Here we investigated whether targeting LRP5 receptor signaling in OS by using a dominant-negative form of this receptor could be a new strategy for OS therapy. Based on our results that DNLRP5 considerably inhibited tumor growth and metastasis in animal models and decreased the expression of cancer cell invasiveness-associated markers, targeting the LRP5 receptor deserves further investigation for the development of novel therapy in OS.

One of the limitations of this study is only one OS cell line (143B) is used as a result of a scarcity of tumorigenic OS cell lines. The other tumorigenic OS cell line (MNNG/HOS) is chemically transformed and therefore may be etiologically less relevant. The 143B cell line used in this study is a K-Ras-transformed derivative of TE85 cells with more metastatic and growth potential in vivo than the parental TE85 line [16, 18]. 143B cells have been used successfully to create a xenograft animal model for human OS with various stages of local tumor growth as well as rapid spontaneous metastasis from an orthotopic injection site [16]. However, given 143B cells are K-Ras transformed and Ras mutation is rare in human OS [20], one must be cautious in generalizing the current in vitro and in vivo data to all clinical OS cases. Nevertheless, given DNLRP5 exhibited antiinvasive effects in both nontransformed SaOS-2 cells [9] as well as in 143B cells, canonical Wnt signaling may play an important oncogenic role and thus deserves further investigation as a potential therapeutic target in human OS.

The first step in the transduction of Wnt signaling involves the binding of Wnt ligands to their membrane receptors. The seven-pass transmembrane, G-coupled Frizzled (Fz) proteins were first identified as high-affinity receptors that bind Wnt proteins [3]. Later, LRP5 was also identified as a coreceptor required for transducing extracellular Wnt signal into intracellular response [23]. Several lines of evidence suggest LRP5 plays an important role in human OS [9, 12]. We previously showed DNLRP5 decreased in vitro cellular invasiveness of SaOS-2 cells [9]. Our data demonstrate the inhibitory effect of DNLRP5 on OS tumor growth using the cell line 143B. Using an orthotopic OS metastasis model in nude mice, we showed DNLRP5 reduced lung metastasis, further suggesting a key role for LRP5 in OS progression.

The epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) has been extensively studied as a result of its critical role in regulating cell migration during embryogenesis and neoplastic invasion [4]. The Snail superfamily of zinc-finger transcription factors is essential for the induction of EMT and the invasive process [24]. Wnt signaling promotes tumor invasion by stabilizing Snail in breast cancer cells [26]. In the current study, DNLRP5 transfection suppressed Snail with associated decrease in cell motility and lung metastasis of 143B cells. This is consistent with reports of increased levels of Snail correlating with a higher metastatic potential of many cancers [1, 2, 24]. In addition to its function as a regulator of EMT, the Snail family of transcription factors can affect MMP activities. Overexpression of Snail in liver cancer cells promotes MMP-2, MMP-7, and MT1-MMP expression [19]. Transfection of melanoma cells with Snail antisense decreases MMP-2 expression [14]. Our data suggest downregulation of Snail after DNLRP5 transfection paralleled a reduction in pro-MMP-2 (Fig. 4). In addition, MMP-2 is a direct transcriptional target of Wnt signaling [25]. Thus, it is possible DNLRP5 can modulate MMP-2 directly by blocking TCF/LEF or indirectly by reducing Snail and its transcriptional activity. However, little is known at this time about how LRP5 activates these mechanisms.

Recent evidence indicates gain of expression of N-cadherin in tumor cells confers an increased metastatic potential. Hazan et al. [10] reported N-cadherin is upregulated in less differentiated and more invasive breast cancer cell lines that lacked E-cadherin. Transfection of N-cadherin into breast cancer MCF-7 cells increased in vitro cell motility and led to widespread metastasis to the lung, liver, pancreas, and lymph nodes when injected into nude mice [11]. Transfection of DNLRP5 downregulated N-cadherin expression in SaOS-2 cells [9] and in 143B cells associated with a less invasive phenotype. Taken together, these findings suggest Wnt-mediated signaling can modulate the invasive program in OS cells through multiple mechanisms.

Blocking Wnt signaling using DNLRP5 led to downregulation of several proteins involved in tumor progression (ie, N-cadherin, Snail, MMP-2). More importantly, DNLRP5 effectively inhibited in vivo tumor growth and spontaneous pulmonary metastasis in an orthotopic xenograft model of OS. Given the pronounced antitumor and antimetastasis effects of DNLRP5, we believe strategies to block canonical Wnt signaling deserve further investigation as an adjuvant therapy for OS.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Matthew Warman for the DNLRP5 construct, Dr Marian Waterman for the TCF luciferase constructs, and Dr Randall F. Holcombe for technical advice.

Footnotes

One or more of the authors has received funding from the Aircast Foundation, the Orthopaedic Research and Education Foundation, and National Institutes of Health CA116003 (BHH); and the Neil Chamberlain Research Fund and National Institutes of Health CA109428 (XZ).

Each author certifies that his or her institution has approved the human and animal protocols for this investigation for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

References

- 1.Batlle E, Sancho E, Francí C, Domínguez D, Monfar M, Baulida J, García De Herreros A. The transcription factor snail is a repressor of E-cadherin gene expression in epithelial tumour cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:84–89. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Beach S, Tang H, Park S, Dhillon AS, Keller ET, Kolch W, Yeung KC. Snail is a repressor of RKIP transcription in metastatic prostate cancer cells. Oncogene. 2008;27(15):2243–2248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Bhanot P, Brink M, Samos CH, Hsieh JC, Wang Y, Macke JP, Andrew D, Nathans J, Nusse R. A new member of the frizzled family from Drosophila functions as a Wingless receptor. Nature. 1996;382:225–230. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Boyer B, Valles AM, Edme N. Induction and regulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transitions. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;60:1091–1099. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Clevers H. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell. 2006;127:469–480. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Dass CR, Ek ET, Contreras KG, Choong PF. A novel orthotopic murine model provides insights into cellular and molecular characteristics contributing to human osteosarcoma. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2006;23:367–380. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Ferguson WS, Goorin AM. Current treatment of osteosarcoma. Cancer Invest. 2001;19:292–315. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Gong Y, Slee RB, Fukai N, Rawadi G, Roman-Roman S, Reginato AM, Wang H, Cundy T, Glorieux FH, Lev D, Zacharin M, Oexle K, Marcelino J, Suwairi W, Heeger S, Sabatakos G, Apte S, Adkins WN, Allgrove J, Arslan-Kirchner M, Batch JA, Beighton P, Black GC, Boles RG, Boon LM, Borrone C, Brunner HG, Carle GF, Dallapiccola B, De Paepe A, Floege B, Halfhide ML, Hall B, Hennekam RC, Hirose T, Jans A, Jüppner H, Kim CA, Keppler-Noreuil K, Kohlschuetter A, LaCombe D, Lambert M, Lemyre E, Letteboer T, Peltonen L, Ramesar RS, Romanengo M, Somer H, Steichen-Gersdorf E, Steinmann B, Sullivan B, Superti-Furga A, Swoboda W, van den Boogaard MJ, Van Hul W, Vikkula M, Votruba M, Zabel B, Garcia T, Baron R, Olsen BR, Warman ML, Osteoporosis-Pseudoglioma Syndrome Collaborative Group. LDL receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) affects bone accrual and eye development. Cell. 2001;107:513–523. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Guo Y, Zi X, Koontz Z, Kim A, Xie J, Gorlick R, Holcombe RF, Hoang BH. Blocking Wnt/LRP5 signaling by a soluble receptor modulates the epithelial to mesenchymal transition and suppresses met and metalloproteinases in osteosarcoma Saos-2 cells. J Orthop Res. 2007;25:964–971. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Hazan RB, Kang L, Whooley BP, Borgen PI. N-cadherin promotes adhesion between invasive breast cancer cells and the stroma. Cell Adhes Commun. 1997;4:399–411. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Hazan RB, Phillips GR, Qiao RF, Norton L, Aaronson SA. Exogenous expression of N-cadherin in breast cancer cells induces cell migration, invasion, and metastasis. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:779–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Hoang BH, Kubo T, Healey JH, Sowers R, Mazza B, Yang R, Huvos AG, Meyers PA, Gorlick R. Expression of LDL receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) as a novel marker for disease progression in high-grade osteosarcoma. Int J Cancer. 2004;109:106–111. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Kato M, Patel MS, Levasseur R, Lobov I, Chang BH, Glass DA 2nd, Hartmann C, Li L, Hwang TH, Brayton CF, Lang RA, Karsenty G, Chan L. Cbfa1-independent decrease in osteoblast proliferation, osteopenia, and persistent embryonic eye vascularization in mice deficient in Lrp5, a Wnt coreceptor. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:303–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Kuphal S, Palm HG, Poser I, Bosserhoff AK. Snail-regulated genes in malignant melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2005;15:305–313. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Lindvall C, Evans NC, Zylstra CR, Li Y, Alexander CM, Williams BO. The Wnt signaling receptor Lrp5 is required for mammary ductal stem cell activity and Wnt1-induced tumorigenesis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:35081–35087. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Luu HH, Kang Q, Park JK, Si W, Luo Q, Jiang W, Yin H, Montag AG, Simon MA, Peabody TD, Haydon RC, Rinker-Schaeffer CW, He TC. An orthotopic model of human osteosarcoma growth and spontaneous pulmonary metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2005;22:319–329. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Luu HH, Zhang R, Haydon RC, Rayburn E, Kang Q, Si W, Park JK, Wang H, Peng Y, Jiang W, He TC. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway as a novel cancer drug target. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2004;14:653–671. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.McAllister RM, Gardner MB, Greene AE, Bradt C, Nichols WW, Landing BH. Cultivation in vitro of cells derived from a human osteosarcoma. Cancer. 1971;27:397–402. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Miyoshi A, Kitajima Y, Sumi K, Sato K, Hagiwara A, Koga Y, Miyazaki K. Snail and SIP1 increase cancer invasion by upregulating MMP family in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:1265–1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Pompetti F, Rizzo P, Simon RM, Freidlin B, Mew DJ, Pass HI, Picci P, Levine AS, Carbone M. Oncogene alterations in primary, recurrent, and metastatic human bone tumors. J Cell Biochem. 1996;63:37–50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Semenov MV, He X. LRP5 mutations linked to high bone mass diseases cause reduced LRP5 binding and inhibition by SOST. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:38276–38284. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Staal FJT, Clevers HC. WNT signalling and haematopoiesis: a WNT-WNT situation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:21–30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Tamai K, Semenov M, Kato Y, Spokony R, Liu C, Katsuyama Y, Hess F, Saint-Jeannet JP, He X. LDL-receptor-related proteins in Wnt signal transduction. Nature. 2000;407:530–535. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Thiery JP. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:442–454. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Wu B, Crampton SP, Hughes CC. Wnt signaling induces matrix metalloproteinase expression and regulates T cell transmigration. Immunity. 2007;26:227–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Yook JI, Li XY, Ota I, Hu C, Kim HS, Kim NH, Cha SY, Ryu JK, Choi YJ, Kim J, Fearon ER, Weiss SJ. A Wnt-Axin2-GSK3beta cascade regulates Snail1 activity in breast cancer cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1398–1406. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Zi X, Guo Y, Simoneau AR, Hope C, Xie J, Holcombe RF, Hoang BH. Expression of Frzb/secreted Frizzled-related protein 3, a secreted Wnt antagonist, in human androgen-independent prostate cancer PC-3 cells suppresses tumor growth and cellular invasiveness. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9762–9770. [DOI] [PubMed]