Abstract

Biofilms are slimy aggregates of microbes that are likely responsible for many chronic infections as well as for contamination of clinical and industrial environments. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a prevalent hospital pathogen that is well known for its ability to form biofilms that are recalcitrant to many different antimicrobial treatments. We have devised a high-throughput method for testing combinations of antimicrobials for synergistic activity against biofilms, including those formed by P. aeruginosa. This approach was used to look for changes in biofilm susceptibility to various biocides when these agents were combined with metal ions. This process identified that Cu2+ works synergistically with quaternary ammonium compounds (QACs; specifically benzalkonium chloride, cetalkonium chloride, cetylpyridinium chloride, myristalkonium chloride, and Polycide) to kill P. aeruginosa biofilms. In some cases, adding Cu2+ to QACs resulted in a 128-fold decrease in the biofilm minimum bactericidal concentration compared to that for single-agent treatments. In combination, these agents retained broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity that also eradicated biofilms of Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella enterica serovar Cholerasuis, and Pseudomonas fluorescens. To investigate the mechanism of action, isothermal titration calorimetry was used to show that Cu2+ and QACs do not interact in aqueous solutions, suggesting that each agent exerts microbiological toxicity through independent biochemical routes. Additionally, Cu2+ and QACs, both alone and in combination, reduced the activity of nitrate reductases, which are enzymes that are important for normal biofilm growth. Collectively, the results of this study indicate that Cu2+ and QACs are effective combinations of antimicrobials that may be used to kill bacterial biofilms.

Biofilms are cell-cell or solid surface-attached assemblages of microbes that are entrenched in a hydrated, self-produced matrix of extracellular polymers. There is increasing recognition among life and environmental scientists that biofilms are a prominent form of microbial life that may cause many different problems, ranging from biofouling and corrosion to plant and animal diseases (13). As a result, there are now numerous studies in the literature describing biofilm susceptibility to single-agent antimicrobial treatments, yet despite this explosion of information, there are relatively few studies that have systematically examined biofilm susceptibility to combinations of antimicrobials. This gap in our knowledge is an important matter to investigate.

Recent findings suggest that the decreased susceptibility of biofilms is linked to a process of phenotypic diversification that is ongoing within the adherent population (4, 8, 16, 22). This means that there are likely multiple cell types in single-species biofilms that ensure population survival in the face of any single adversity. Treating biofilms with combinations of chemically distinct antimicrobials might be an effective strategy to kill some of these different cell types. In light of this emerging perspective, our research group undertook the present study to explore the possibility of using combinations of rationally selected agents, as described below, to treat biofilms of the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa. This microorganism is well studied and suited for biofilm research, as P. aeruginosa biofilms are much more resilient to conventional forms of chemical removal and disinfection than their corresponding populations of planktonic cells (13, 16, 30).

Which antimicrobial agents may be used to treat biofilms of P. aeruginosa? Lately, several inorganic metal species have attracted attention as antibacterials because they exert time-dependent toxicities that kill biofilms in vitro (14-16, 18, 21) as well as P. aeruginosa in vivo (21). It is important that microbicidal concentrations of certain toxic metal species may be poisonous to higher organisms, and therefore, this hazard limits the choices and concentrations of inorganic ions that may be used as part of antimicrobial treatments. However, certain metal ions with relatively lower biological toxicities to humans and to the environment might still be useful in many products—including disinfectants, surface coatings, hard surface treatments, and topical ointments—particularly in combination with detergents or other cleansers. The specific aim of this study, therefore, was to identify metal ions that might synergistically enhance the efficacy of biocides against P. aeruginosa biofilms.

We developed a high-throughput technique for biofilm susceptibility testing and examined antimicrobial arrays representing approximately 4,400 different combinations of metals and biocides (this included variations in concentrations of individual agents as well as different exposure times). By evaluating these combinatorial panels for bactericidal and antibiofilm activity, we identified and subsequently rigorously validated that Cu2+ enhanced the in vitro killing of P. aeruginosa biofilms by quaternary ammonium compounds (QACs).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth media.

All of the microbial strains used in this study are summarized in Table 1, and all were stored at −70°C in Microbank vials (ProLab Diagnostics, Toronto, Canada) according to the manufacturer's directions. These organisms were cultured on tryptic soy agar (TSA; EMD Chemicals Inc.) and incubated at 30°C for 24 to 48 h. Biofilms of all of the organisms used in this study were cultivated in tryptic soy broth (TSB; EMD Chemicals Inc.), and all serial dilutions were performed using 0.9% NaCl. Susceptibility testing was performed in 10% TSB diluted with either 0.9% saline (NaCl) or double-distilled water (ddH2O), as indicated throughout this report. As the exception, Salmonella enterica serovar Cholerasuis ATCC 10708 was cultivated in cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (EMD Chemicals, Inc.) and tested in 25% cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth that had been diluted with 0.9% NaCl. Microaerobic cultures were grown in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (EMD Chemicals Inc.).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant characteristics | Mean biofilm cell densitya (CFU/peg) | n | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli MBEC03 | Isolated from a slaughterhouse | 5.7 ± 0.4 | 60 | This study |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 15442 | Standard strain for biocide susceptibility testing (AOAC guidelines) | 6.8 ± 0.6 | 297 | ATCC |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 | Standard strain for antibiotic susceptibility testing (CLSI guidelines) | 6.7 ± 0.2 | 8 | 6 |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens ATCC 13552 | Environmental organism implicated in food spoilage | 5.7 ± 0.5 | 12 | 38 |

| Salmonella enterica serovar Cholerasuis ATCC 10708 | Standard strain for biocide susceptibility testing (AOAC guidelines) | 4.7 ± 0.4 | 64 | ATCC |

| Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538 | Standard strain for biocide susceptibility testing (AOAC guidelines) | 5.6 ± 0.4 | 60 | ATCC |

Starting cell density measurements were based on the means and standard deviations of the pooled, log-transformed data for the indicated numbers of replicates (n).

Stock solutions of metals and biocides.

Sodium selenite (Na2SeO3; Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis, MO), silver nitrate (AgNO3; Sigma), cupric sulfate (CuSO4·5H2O; Fischer Scientific, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada), zinc sulfate (ZnSO4·7H2O; Fischer Scientific), and aluminum sulfate [Al2(SO4)3·18H2O; Fischer Scientific] were diluted in sterile ddH2O to make stock solutions at twice the maximum concentration used for susceptibility testing. Additional serial twofold dilutions of each of these agents were prepared as required in sterile polypropylene tubes, using ddH2O.

Polycide (Pharmax Limited, Toronto, Ontario, Canada), Virox (Virox Technologies Incorporated, Oakville, Ontario, Canada), and Stabrom 909 (Albemarle Corporation, Richmond, VA) were diluted in ddH2O to four times the working concentration recommended by the manufacturer. Isopropyl alcohol (Sigma) was made up to a 70% (vol/vol) solution in ddH2O. Benzalkonium chloride (alkyldimethylbenzyl ammonium chloride; Sigma), cetalkonium chloride (cetyldimethylbenzyl ammonium chloride; FeF Chemicals, Denmark), cetylpyridinium chloride (cetyldimethylpyridyl ammonium chloride; FeF Chemicals), and myristalkonium chloride (tetradecyldimethylbenzyl ammonium chloride; FeF Chemicals) were made up to a stock concentration of 10,000 ppm in ddH2O. Solutions of QACs were incubated at 37°C to facilitate dissolution.

Biofilm cultivation.

Biofilms were grown in a Calgary biofilm device (CBD; commercially available as the MBEC physiology and genetics assay [Innovotech Inc., Edmonton, Alberta, Canada]), as originally described by Ceri et al. (6). An overview of this biofilm cultivation technique (as well the high-throughput screening process described below) is illustrated in Fig. 1. CBDs consist of a polystyrene lid, with 96 downward-protruding pegs, that fits into standard 96-well microtiter plates. Starting from cryogenic stocks, the desired bacterial strain was streaked out twice on TSA, and an inoculum was prepared by suspending colonies from the second agar subculture in 0.9% NaCl to match a 1.0 McFarland standard. This standard inoculum was diluted 30-fold in growth medium to get a starting viable cell count of roughly 1.0 × 107 CFU/ml. One hundred fifty microliters of this inoculum was transferred into each well of a 96-well microtiter plate, and the sterile peg lid of the CBD was inserted into the plate. The inoculated device was then placed on a gyrorotary shaker at 125 rpm for 24 h of incubation at 37°C and 95% relative humidity.

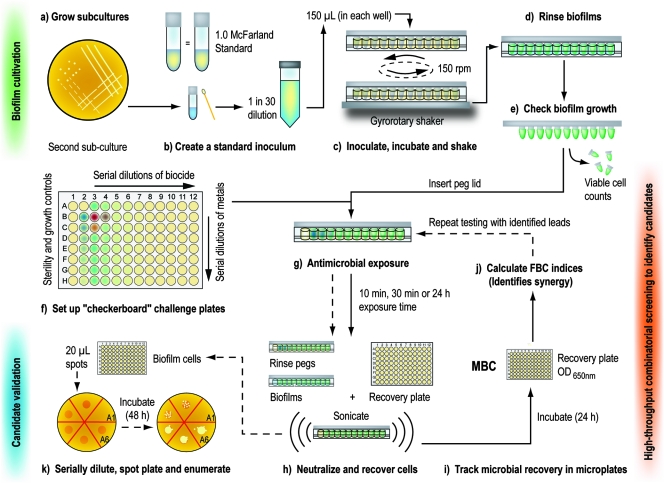

FIG. 1.

High-throughput screening may be used to identify synergistic antimicrobial interactions that kill microbial biofilms. Starting from cryogenic stocks, the desired bacterial strain was streaked out twice on TSA (a), and colonies from the second subcultures were suspended in growth medium to match a 1.0 McFarland optical standard (b). This standardized suspension, diluted 30-fold in TSB, served as the inoculum for the CBDs. The inoculated devices were assembled and incubated on a gyrorotary shaker (c), which facilitated the formation of 96 statistically equivalent biofilms on the peg surfaces (data not shown). Biofilms were rinsed with 0.9% NaCl (d), and surface-adherent growth was verified by viable cell counting (e). Antimicrobials were set up in “checkerboard” arrangements in microtiter plates (f), and the rinsed biofilms were inserted into these challenge plates for the desired exposure time (g). Following antimicrobial exposure, biofilms were rinsed and inserted into recovery plates. Biofilm cells were disrupted into the recovery medium by sonication (h), and the recovery plates were incubated for 24 h before the OD650 values of recovered cultures were read in a microtiter plate reader (i). This allowed the FBC index to be calculated, and this was used to identify “candidate” synergistic interactions (j). Candidates were validated by repeating the testing process (as outlined in steps a to h), but instead of qualitative measurements, biofilm cell survival was quantified by viable cell counting on agar plates (k).

Following this initial period of incubation, biofilms were rinsed once with 0.9% saline (by placing the lid in a microtiter plate containing 200 μl of 0.9% NaCl in each well) to remove loosely adherent planktonic cells. Biofilm formation was evaluated by breaking off four pegs from each device after it had been rinsed. Biofilms were disrupted from pegs into 200 μl of 0.9% NaCl by use of an ultrasonic cleaner on the high setting for a period of 5 min (Aquasonic model 250 HT; VWR Scientific, Mississauga, Canada), as previously described (6). The disrupted biofilms were serially diluted and plated onto agar for viable cell counting. The pooled mean starting viable cell counts for biofilms are summarized in Table 1.

In an additional set of quality control assays, it was ascertained that the strains used in this study formed equivalent biofilms on the pegs of the CBD. To do this, we disrupted biofilms from the lid of the CBD into a microtiter plate containing 200 μl of 0.9% NaCl in each well, serially diluted the recovered cells, and plated these onto TSA for viable cell counting. These agar plates were incubated for 24 h at 37°C, and then the colonies were enumerated. Viable cell counts were grouped by row of the CBD, and these values were compared using one-way analysis of variance as previously described (6). In all cases, biofilms cultivated under the conditions reported here formed statistically equivalent biofilms between the rows of the CBD (P > 0.05) (data not shown).

High-throughput susceptibility testing of microbial biofilms.

“Checkerboard” arrangements of biocides and toxic metal species were made in 96-well microtiter plates as previously described (25). When prepared, each checkerboard microtiter plate had 7 sterility controls, 2 growth controls, 10 different concentrations of biocides alone, 7 different concentrations of toxic metal species alone, and each metal and biocide at 70 different combinations of concentrations. The use of these checkerboard plates in the process of biofilm susceptibility testing is briefly described here (Fig. 1f to j).

Biofilms that had been grown on lids of the CBD were inserted into the checkerboard challenge plates after the biofilms had been rinsed (as described above). Following antimicrobial exposure, biofilms were rinsed again (by placing the lid in a microtiter plate containing 200 μl of 0.9% NaCl in each well) and then placed in a microtiter “recovery” plate that contained 200 μl of neutralizing medium in each well (TSB supplemented with 1% Tween 20, 2.0 g/liter reduced glutathione, 1.0 g/liter l-histidine, and 1.0 g/liter l-cysteine). These steps were carried out to minimize the effects of biocide and metal carryover. Bacterial cells were recovered from biofilms by disrupting the biofilms into the recovery medium, using an ultrasonic cleaner (as described above). These plates were then incubated for 24 h at 37°C. Minimum bactericidal concentrations for the biofilm (MBCb) were determined by reading the optical density at 650 nm (OD650) of the recovery plates, using a Thermomax microtiter plate reader with Softmax Pro data analysis software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). For the purpose of high-throughput screening, we arbitrarily defined an effective MBCb end point as an OD650 of ≤0.300. In contrast, growth controls incubated under identical conditions typically produced OD650 values of ≈0.9 to 1.5.

To validate the “candidate” combinations identified from high-throughput screening (see the section below for the criteria used to evaluate these data), mean viable cell counts were determined for biofilms following exposure to metals and/or biocides (Fig. 1K). This was done by serially diluting (10-fold) 20-μl aliquots from the wells of the recovery plates (prepared as described above) in 0.9% saline and plating these diluted cultures onto TSA. To maximize the recovery of viable but potentially slow-growing bacteria surviving antimicrobial exposure, up to 48 h of incubation at 37°C was allowed before growth on these agar plates was scored.

Criteria for evaluating the antibiofilm activity of combination antimicrobials.

“Candidate” synergistic interactions were identified using rules that were modified from those suggested by the American Society for Microbiology for the testing of planktonic cells (25). Synergy was defined mathematically by calculating the sum (Σ) of the fraction bactericidal concentration (FBC) values (termed the FBC index) for each combination of antimicrobial agents, as follows: FBC of agent A = MBCb of agent A in combination/MBCb of agent A alone; FBC of agent B = MBCb of agent B in combination/MBCb of agent B alone; and ΣFBC = FBC of agent A + FBC of agent B.

For the purpose of evaluating antimicrobial interactions, we used the lowest FBC index method as described by Bonapace et al. (5). In this case, the FBC index was based on the lowest ΣFBC that was calculated for all of the wells along the kill-nonkill interface, using the median MBCb values for single-agent treatments as the reference points (Table 2). Taking into account the error associated with biofilm susceptibility testing using the CBD, which generally produces end points over a 16-fold range (compared to an 8-fold range for planktonic cell susceptibility testing), survival data from the high-throughput susceptibility assays were grouped as follows: (i) if ΣFBC was ≤0.125, then the antimicrobials exhibited synergy; (ii) if 0.125 < ΣFBC < 16, then indifference had occurred; and (iii) if ΣFBC was ≥16, then the antimicrobials exhibited antagonism.

TABLE 2.

Susceptibility of P. aeruginosa ATCC 15442 biofilms to single-agent treatments, as determined by high-throughput screening (using CBDs)a

| Metal ion or biocide (concn unit) | MBCb

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 min (in ddH2O) | 30 min (in ddH2O) | 24 h (in 10% TSB-ddH2O) | |

| Ag+ (mM) | >19 | >19 | >19 |

| Cu2+ (mM) | >32 | >32 | 32 (16 to 32) |

| Al3+ (mM) | >76 | >76 (38 to >76) | 76 (76 to >76) |

| SeO32− (mM) | >16 | >16 | >16 |

| Zn2+ (mM) | >31 | >31 | >31 |

| Polycide (ppm) | >3,200 (50 to >3,200) | 1,800 (100 to >3,200) | 400 (50 to 800) |

| Stabrom (ppm) | 250 (31 to >500) | 250 (16 to >500) | 94 (63 to >1,600) |

| Isopropyl alcohol (%) | 0.50 (0.25 to 0.50) | 0.50 (0.25 to 0.50) | 0.50 (0.25 to >0.50) |

| Virox (ppm) | 313 (156 to 5,000) | 313 (156 to 2,500) | 625 (313 to 2,500) |

Note that these assays were performed using a high-throughput screening method that judges killing qualitatively. Incomplete killing of microbial populations may still occur with short exposure times, but this is not detected by the high-throughput method employed here.

For the purpose of evaluating time-kill data based on mean viable cell counts, which was used to validate candidates identified by high-throughput screening, we looked for ≥1-log10 decreases in the mean CFU/peg between the metal-biocide combination and the most active comparable single-agent treatment following 10 or 30 min of exposure and for ≥2-log10 decreases at 24 h of exposure. It was also required that the candidate combination produce a ≥2-log10 decrease in the mean CFU/peg relative to the starting biofilm cell count (Table 1) and that one agent be present at a concentration that did not affect the number of surviving cells relative to that for the appropriately treated growth control.

Susceptibility testing of microaerobic planktonic cultures.

An aerobic P. aeruginosa ATCC 15442 starter culture was grown overnight in TSB, and this was diluted 1 in 500 in BHI broth to get a starting cell count of 1 × 107 CFU/ml for microaerobic cultures. This was sealed tightly in 1.0-liter bottles which had been filled completely with the inoculated BHI broth and was grown at 37°C, with or without the addition of 1 mM KNO3, as indicated throughout this report. These microaerobic cultures were incubated for 6 h prior to the addition of 1 mM CuSO4, 25 ppm Polycide, or 1 mM CuSO4 plus 25 ppm Polycide. A viable cell count was determined at 6 h (at the point when the antimicrobials were added) as well as at 54 h, when the cells were harvested for enzyme assays. Serial dilution and agar plating to obtain viable cell counts were carried out in a fashion identical to that described for biofilms.

Protein fractionation and nitrate reduction assays.

Planktonic cells grown under microaerobic conditions were collected by centrifugation (3,000 × g for 20 min), washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.2), and collected by centrifugation again. Cell pellets were suspended in phosphate-buffered saline with 2 mg/ml lysozyme (Sigma) and incubated on ice for 30 min. The enzyme-treated cells were then disrupted with a Microsan ultrasonic cell disruptor (Misonix Inc., Farmingdale, NY), using five 5-s bursts at a 5-W power setting. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation (3,000 × g for 30 min), and the supernatant was additionally fractionated into membrane and cytosolic components by a second centrifugation at 125,000 × g for 90 min. Nitrate reductase (NR) activity was determined spectrophotometrically at 575 nm for cytoplasmic fractions, using methyl viologen as an electron donor, as previously described (19, 23). NR activity calculations were corrected for baseline shifts in spectrophotometric measurements caused by the presence of O2 in water, which reacts with reduced methyl viologen over time.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM).

Pegs were broken from the lid of the CBD by use of needle nose pliers. Cell viability staining of P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 biofilms by use of a Live/Dead BacLight kit (Molecular Probes, Burlington, Ontario, Canada) was carried out according to the method of Harrison et al. (17). Biofilms exposed to metals and/or biocides were rinsed twice with 0.9% saline and then stained with Syto-9 and propidium iodide at 30°C for 30 min.

Fluorescently labeled biofilms were placed in 2 drops of 0.9% saline on the surface of a glass coverslip. These pegs were examined using a Leica DM IRE2 spectral confocal and multiphoton microscope with a Leica TCS SP2 acoustic optical beam splitter (Leica Microsystems, Richmond Hill, Ontario, Canada) as previously described (17). To eliminate artifacts associated with single-wavelength excitation, Live/Dead BacLight-stained samples were sequentially scanned, frame-by-frame, first at 488 nm and then at 543 nm. Fluorescence emission was then sequentially collected in the green and red regions of the spectrum. A 63× water immersion objective was used in all imaging experiments. Image capture and two-dimensional reconstruction of z stacks were performed using Leica confocal software (Leica Microsystems).

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC).

All measurements were made on a Microcal VP-ITC instrument (Microcal LLC, Northampton, MA). Briefly, a time course of injections of CuSO4 to benzalkonium chloride (and vice versa) was made in a reaction cell maintained at a constant temperature. These experiments were performed in both ddH2O and 4 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.1). The VP-ITC instrument measures the heat generated or absorbed by any reaction or interaction that occurs, which is later corrected for heats of dilution. A binding isotherm was fitted to the data, expressed in terms of heat change per mole of CuSO4 (or benzalkonium chloride) plotted against the molar ratio of CuSO4 to benzalkonium chloride. In principle, it is possible to calculate, from the binding isotherm, values for the reaction stoichiometry, association constants (Ka), the change in enthalpies (ΔH°), and the change in entropies (ΔS) for any reaction that has occurred. If no reaction has occurred, then the corrected binding isotherms will be straight lines with a slope that approximates zero (9).

Statistical tests and data analysis.

Analysis of variance was performed using MINITAB, release 14 (Minitab Inc., State College, PA), to analyze log10-transformed raw data. Alternate hypotheses were tested at the 95% level of confidence. Mean and standard deviation calculations were performed using Microsoft Excel 2003 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA), and these data were imported into SigmaPlot 10.0 (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA) for three-dimensional graphical representation.

RESULTS

High-throughput susceptibility testing to identify combinations of antimicrobials with synergistic antibiofilm activity.

To begin, we conducted a high-throughput screen (Fig. 1) with the aim of identifying combinations of antimicrobial agents that might possess antibiofilm activity against P. aeruginosa ATCC 15442 (a strain used for the regulatory testing of hard surface disinfectants). Checkerboard arrangements of antimicrobials in 96-well microtiter plates were used to examine four classes of biocides (QACs, halides, peroxides, and alcohols, at 10 different concentrations of each) alone or in combination with five different metal cations and oxyanions (Cu2+, Ag+, Al3+, SeO32−, and Zn2+, at 7 different concentrations of each). Additionally, we examined three different exposure durations (5 min, 30 min, and 24 h). The susceptibility of P. aeruginosa biofilms to single-agent treatments was determined by pooling susceptibility data from the control wells in checkerboard assays (Table 2), which were used as reference points in ΣFBC calculations. When completed, this high-throughput screening process evaluated a total of 4,425 unique combinations of agents, concentrations, and exposure times. For simplicity, these initial results were categorized by metal-biocide combination, and then the lowest ΣFBC values were calculated using the criteria defined in Materials and Methods (Table 3). This approach identified the following six “candidate” synergistic combinations of antimicrobials: (i) Cu2+ and Virox (“accelerated” hydrogen peroxide), (ii) Ag+ and Stabrom (a halide disinfectant), (iii) Cu2+ and Polycide (a mixture of QACs), (iv) Al3+ and Virox, (v) SeO32− and Stabrom, and (vi) SeO32− and Virox (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Lowest FBC indices for combinations of biocides and metals tested against P. aeruginosa ATCC 15442 biofilms during high-throughput screening to determine synergy (using CBDs)a

| Metal | Exposure timeb | FBC index with biocidec

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polycide | Stabrom 909 | 70% (wt/vol) isopropanol | Virox | ||

| Ag+ | 5 min | ND | 0.02 | 1.0 | 4.0 |

| 30 min | 0.36 | 0.04 | ND | 0.53 | |

| 24 h | 1.0 | ND | 0.15 | 0.14 | |

| Cu2+ | 5 min | 1.25 | ND | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| 30 min | 0.03 | ND | 0.72 | 0.51 | |

| 24 h | 0.06 | 0.67 | 1.0 | 0.08 | |

| Al3+ | 5 min | 0.5 | ND | 0.52 | ND |

| 30 min | 0.24 | ND | 0.52 | 0.52 | |

| 24 h | ND | 1.7 | 2.0 | 0.08 | |

| SeO32− | 5 min | 2.0 | ND | 1.0 | 2.0 |

| 30 min | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.53 | 0.53 | |

| 24 h | 0.53 | 1.3 | 0.51 | 0.03 | |

| Zn2+ | 5 min | ND | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.0 |

| 30 min | ND | 0.52 | 2 | 0.52 | |

| 24 h | 0.625 | 1.25 | 0.16 | 0.14 | |

Note that these assays were performed using a high-throughput screening method that judges killing qualitatively. Incomplete killing of microbial populations may still occur synergistically with short exposure times, but this is not detected by the high-throughput method employed here.

Susceptibility testing was performed in ddH2O for exposure times of 5 and 30 min, whereas 10% TSB-0.9% NaCl was used for 24-h exposures.

ND, results could not be determined from the concentration ranges examined experimentally, i.e., the agents did not effectively kill the biofilms. Data shown in bold denote a synergistic interaction, as defined by the criteria outlined in Materials and Methods.

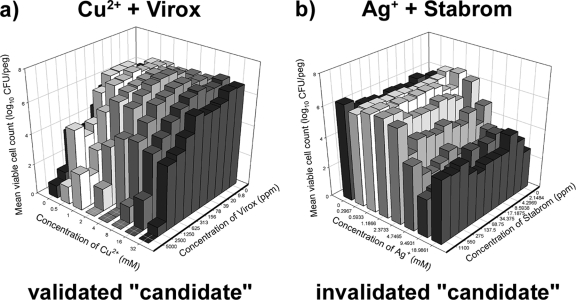

From this initial set of six candidates, combinations of Al3+ or SeO32− with biocides were not examined any further (this decision was made based on the high in vitro concentrations at which the synergy was observed as well as due to the formation of metal precipitates in the culture medium). Next, false-positive results were eliminated from the remaining candidates by counting the number of viable cells in biofilms that had been exposed (for 30 min in ddH2O) to different concentrations of these agents alone and in combination. A combination was considered synergistic if there was a ≥1-log10 decrease in the mean CFU/peg between the combination and the most active comparable single-agent treatment (see Materials and Methods for additional criteria). This process eliminated Ag+ and Stabrom (Fig. 2) as a synergistic antimicrobial combination but validated both Cu2+ and Virox (Fig. 2) and Cu2+ and Polycide (Fig. 3; discussed in the sections that follow) as synergistic antimicrobial combinations with antibiofilm activity.

FIG. 2.

“Candidate” combinations of antimicrobials were validated by viable cell counting. (a) Cu2+ and Virox displayed synergy in several combinations, and there were concentrations at which the combination of the two compounds eradicated biofilms, whereas either agent used alone did not eliminate residual biofilm cell survival. (b) In contrast, combinations of Ag+ and Stabrom did not kill biofilm cells better than either agent did alone; therefore, this candidate combination was invalidated by this process. In these plots, each bar represents the average for three independent replicates.

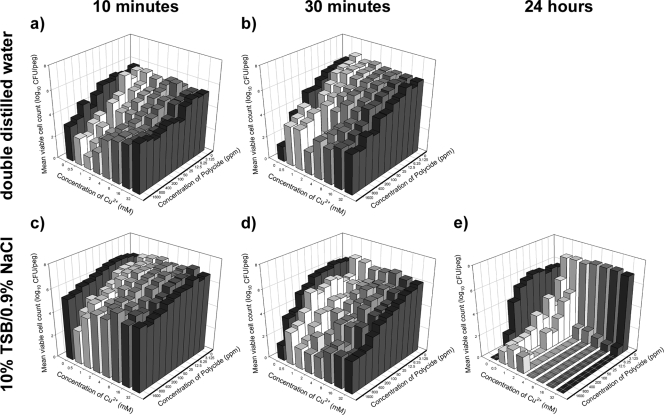

FIG. 3.

P. aeruginosa ATCC 15442 biofilms were killed time dependently by combinations of Cu2+ and Polycide. Viable cell counts were determined after exposure of biofilms to combinations of Cu2+ and Polycide in ddH2O for 10 min (a) or 30 min (b) or after exposure in dilute organics for 10 min (c), 30 min (d), or 24 h (e). In these plots, each bar represents the average for three independent replicates. In every test scenario, it was possible to discern antimicrobial synergy.

The combination of Cu2+ and Virox was also eliminated from further study due to information from the scientific literature indicating that Cu2+ and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, the active compound in Virox) participate in an autocatalytic chemical reaction that produces highly toxic reactive oxygen species (ROS). This is a form of the Fenton reaction (16, 33), which has previously been applied to biofilm disinfection by use of a variety of approaches (37). In this case, P. aeruginosa ATCC 15442 biofilms were killed synergistically by Cu2+ and Virox with as little as 30 min of exposure (Fig. 2a). Although this is an interesting finding, the Fenton reaction rapidly degrades peroxides, and therefore, the activated disinfectant likely has a limited life span. ROS are also highly toxic and would damage all biological systems, which means that the disinfectant might lack specificity to microbes, which would limit its applications. Therefore, this candidate was not characterized any further, and we focused on combinations of Cu2+ with Polycide.

Although there is at least one study that has previously looked at combinations of Cu2+ with QACs as antimicrobials (36), there is no examination of these compounds together as antibiofilm agents. The latter finding caught our attention immediately because previous work, including some of our own, has shown that in contrast to planktonic bacterial cells, biofilms are generally highly resistant and/or tolerant to both QACs (10, 29, 32) and copper cations (7, 18, 33, 34). It is worth noting that QACs might be advantageous compounds to use in antimicrobial formulations because they may function as cleansers or deodorizers (24) and, when used effectively, generally exhibit broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity that may be residually active on surfaces. Our next step, therefore, was to systematically characterize the concentration- and time-dependent killing of P. aeruginosa ATCC 15442 biofilms by these agents.

Time- and concentration-dependent killing of P. aeruginosa biofilms by Cu2+ and Polycide.

The guidelines set by the Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC) suggest that to demonstrate antibacterial efficacy of novel compounds for use as disinfectants, susceptibility testing should be conducted using ddH2O to dissolve the antimicrobials. The AOAC also suggests that cell survival should be evaluated after 10 min and 30 min of exposure. We performed these assays, and these data are presented in Fig. 3a and b, respectively. In addition to these assays, we also examined biofilm cell survival in the presence of rich medium (whose contents may decrease the efficacy of some metal cations and QACs via unwanted chemical reactions). In this case, we dissolved the antimicrobials in 10% TSB-0.9% NaCl and evaluated the number of surviving cells in biofilms after 10 min, 30 min, and 24 h of exposure (Fig. 3c to e, respectively). At many of the combination concentrations tested—both in ddH2O and in organic medium—Cu2+ and Polycide killed 10 to 100 times more biofilm cells than did either antimicrobial alone. Furthermore, at 24 h of exposure, combinations of Cu with Polycide were able to reduce the number of surviving biofilm cells to below the threshold of detection in vitro, indicating that these compounds might sterilize the biofilm at concentrations that were at least 128-fold lower than the sterilizing concentrations of either agent alone (Fig. 3e). These assays rigorously validated Cu and Polycide as a synergistic combination of antibacterials with high antibiofilm activity against P. aeruginosa ATCC 15442. A logical (and necessary) next step was to examine these compounds for activity against other microbial species.

Cu2+ and Polycide have broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity.

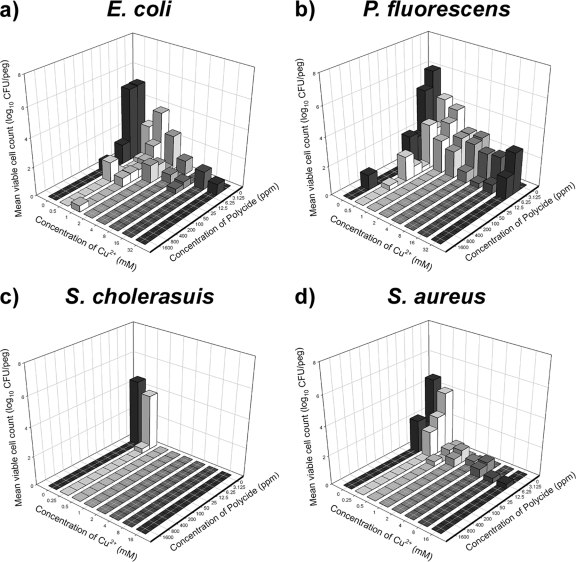

In addition to P. aeruginosa ATCC 15442, the AOAC suggests a standard set of two additional strains, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538 and Salmonella enterica serovar Cholerasuis ATCC 10708, to assess the antibacterial efficacy of novel disinfectants (Fig. 4). In addition to these two strains, we examined Escherichia coli MBEC03, a food-borne strain that we isolated from a slaughterhouse, and Pseudomonas fluorescens ATCC 15325, a microbial species implicated in food spoilage (Fig. 4). The results of these additional biofilm susceptibility assays indicate that combinations of Cu2+ and Polycide have a broad spectrum of antibacterial activity; furthermore, these agents may eradicate biofilms formed by other microbes at concentrations that are much lower than those required to treat P. aeruginosa ATCC 15442 biofilms.

FIG. 4.

Killing of Escherichia coli (a), Pseudomonas fluorescens (b), Salmonella enterica serovar Cholerasuis (c), and Staphylococcus aureus (d) biofilms by combinations of Cu2+ and Polycide. These data are for 24 h of exposure in dilute organics, and each bar represents the average for three independent replicates. These results indicate that Cu2+ and Polycide have broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity that, in general, kills biofilms of other gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria at concentrations that are much lower than those required to treat P. aeruginosa biofilms.

CLSM of bacterial cell survival in biofilms exposed to Cu2+ and Polycide both alone and in combination.

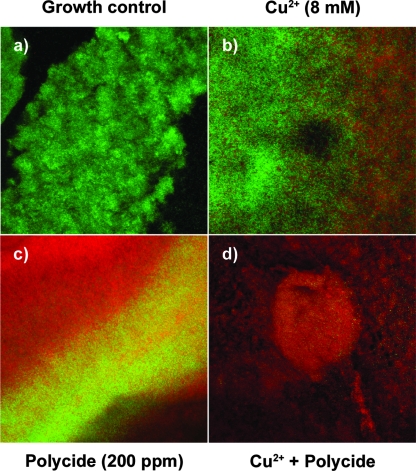

Up to this point, we assessed the antimicrobial action of Cu2+ and Polycide by using viable cell counting; however, there is an alternative method of assessing biofilm cell survival, i.e., CLSM in conjunction with Live/Dead BacLight staining. It may be important to examine biofilm cell survival by using a complementary method, as there are now scattered reports in the literature that Cu2+ may induce a viable but nonculturable state in some bacteria (1, 11, 26). Live/Dead BacLight staining may be used to discriminate the viable but nonculturable phenomenon from cell death. The Live/Dead BacLight stain uses the nucleic acid intercalator Syto-9 (which passes through intact membranes and fluoresces green in viable, or living, cells) and the counterstain propidium iodide (which is expelled from viable cells but fluoresces red when bound to DNA and RNA in dead cells). In other words, by using this technique it is possible to obtain images of biofilms where viable, or living, cells appear green and dead cells appear red (17). We used this qualitative approach to examine P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 biofilms that were treated with Cu2+ and Polycide, both alone and in combination. Our research group has previously identified that this particular strain of P. aeruginosa forms complex three-dimensional structures on the peg surfaces of CBDs (J. J. Harrison and H. Ceri, unpublished data). In each case, the microcolonies examined in the CBD were approximately 5 to 15 μm in height, and the captured images were processed to give a top-down view of the biofilm image stack (Fig. 5). Although the flow dynamics are much more complex in the CBD, a similar approach was previously used to examine spatial patterns of killing in flow cell biofilms (21).

FIG. 5.

Live/Dead BacLight staining of P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 biofilms exposed to Cu2+ and Polycide indicates that these agents are bactericidal. In these pictures, green cells are live bacteria and red cells are dead bacteria. (a) Growth controls. (b) Treatment of biofilms with 8 mM Cu2+. (c) Treatment of biofilms with 200 ppm Polycide. (d) Treatment of biofilms with a combination of 8 mM Cu2+ and 200 ppm Polycide. Each panel is a top-down view of a CLSM image z stack and represents an area of 238 by 238 μm.

In contrast to growth controls, which were comprised chiefly of living bacterial cells (Fig. 5a), treatment with 8 mM Cu2+ killed a significant portion of the bacterial population (Fig. 5b). Similarly, 200 ppm Polycide killed a large portion of the P. aeruginosa biofilms, with many surviving cells localized to interior regions of the surface-adherent community (Fig. 5c). In contrast, the combination of 8 mM Cu2+ with 200 ppm Polycide killed the vast majority of the biofilm bacteria, with few survivors at the surface or in the interior regions of larger microcolonies (Fig. 5d). Cumulatively, these results corroborate the conclusion, based on viable cell counts, that Cu2+ and Polycide are bactericidal and that these agents have antibiofilm activity against P. aeruginosa. The next logical step was to examine the active ingredients of Polycide (benzalkonium chloride and cetyldimethylethylammonium bromide), as well as other QACs, in combination with Cu2+ as novel antibacterial formulations.

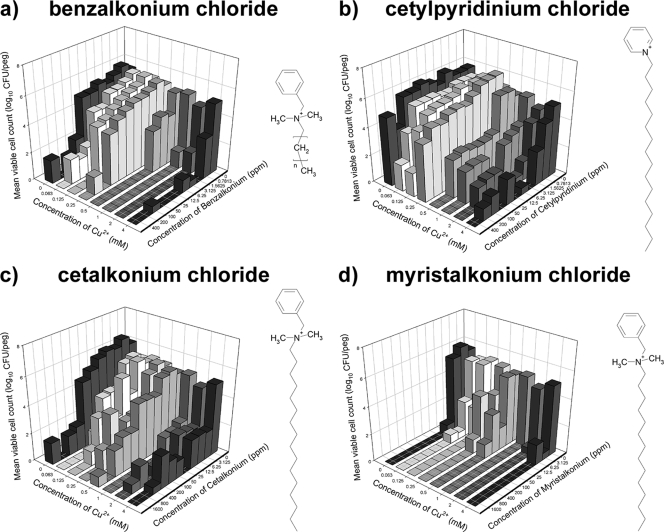

Synergistic killing of P. aeruginosa biofilms by Cu2+ in combination with structurally different QACs.

We tested the following four additional QACs (in 10% TSB-ddH2O with 24 h of exposure) for possible synergistic interactions with Cu2+: benzalkonium chloride, cetylpyridinium chloride, cetalkonium chloride, and myristalkonium chloride (Fig. 6). In all cases, it was possible to identify concentrations at which the combination of QAC with Cu2+ was more effective at killing P. aeruginosa ATCC 15442 biofilms than the most effective single agent used alone. This was particularly true of Cu2+ in combination with either benzalkonium chloride (Fig. 6a) or cetalkonium chloride (Fig. 6c). These results clearly indicate that Cu2+ in combination with other (structurally different) QACs can function synergistically to kill P. aeruginosa ATCC 15442 biofilms. Our next step was to determine if Cu and QACs might interact in solution, which might provide clues about how these agents are toxic to bacteria.

FIG. 6.

Combinations of Cu2+ with other QACs show synergistic killing of P. aeruginosa ATCC 15442 biofilms. Viable cell counts were determined after exposure of biofilms to combinations of Cu2+ and benzalkonium chloride (a), cetylpyridinium chloride (b), cetalkonium chloride (c), or myristalkonium chloride (d). In these plots, each bar represents the average for two independent replicates. The chemical structure for each of these cations is shown, where n denotes a side chain of variable length, with 8 to 25 carbon atoms.

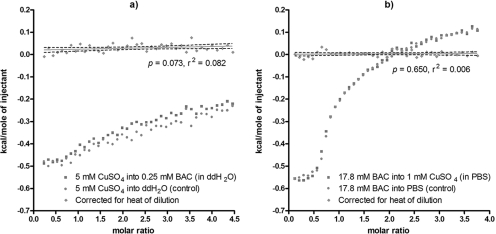

Cu2+ and benzalkonium chloride do not interact directly in aqueous solutions.

Using ITC, a sensitive biophysical technique used to measure the heat released or absorbed during the binding of a ligand to another molecule, we investigated the possibility that copper might form a complex with benzalkonium chloride. This QAC was examined here because it exhibited synergistic killing of biofilms in conjunction with Cu2+ (used alone or as a component of Polycide). We observed no evidence for binding of Cu2+ to benzalkonium chloride when the titration was carried out in ddH2O (Fig. 7a). We also looked for binding of Cu2+ to benzalkonium chloride in 4 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.1), as it is possible, under aqueous conditions, for PO43− to coordinate Cu2+ to ammonium groups (R-NH3+) similar to synthetic metalloreceptors (35). Again, there was no evidence that, together, these compounds formed a tertiary complex (Fig. 7b). We concluded from these data that under the tested aqueous conditions, Cu2+ and benzalkonium chloride neither formed complexes nor underwent chemical reactions, as the latter possibility would have also resulted in the release or absorption of heat. This suggests that Cu2+ and QACs are likely toxic to bacterial biofilms through independent but complementary biochemical mechanisms (i.e., these compounds are truly synergistic in terms of biological toxicity).

FIG. 7.

ITC of CuSO4 and benzalkonium chloride suggests that these compounds do not chemically interact. Titration was carried out in ddH2O (a) or in phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.1) (b). In these plots, the squares represent the titration of CuSO4 into the QAC (or vice versa), whereas the circles represent the heat of dilution released from dissolution of the titrant into the appropriate buffer. The diamonds and the regression line of best fit represent the net amount of heat released during the titration, corrected for the heat of dilution. In all cases, the slope of the line of best fit did not significantly deviate from zero. Each panel shows a representative data set from two independent replicates.

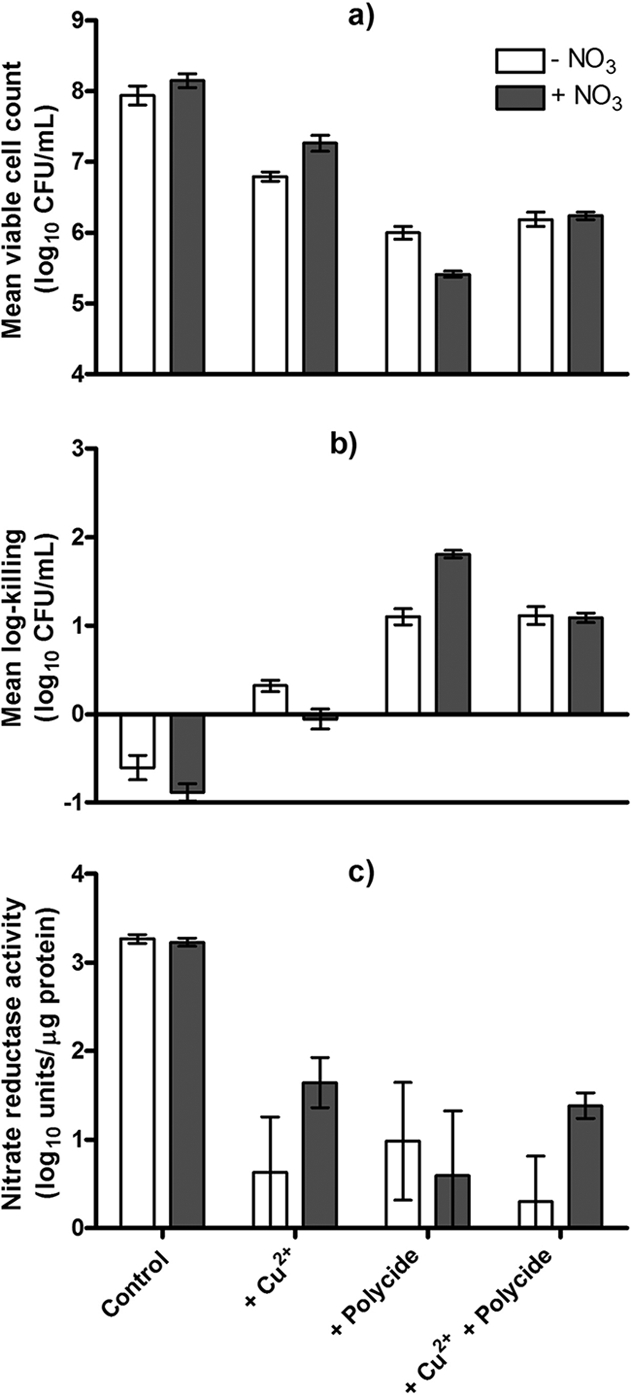

Effects of Cu2+ and QACs on microaerobic growth and P. aeruginosa nitrate reduction.

Membrane-bound enzymes may be targets for Cu2+ and QAC toxicity, and it has been suggested that these agents might also inhibit the activity of periplasmic or membrane-bound NRs in P. aeruginosa (36). In this study, this was investigated as a mechanism of toxicity, as microaerobic growth that involves both oxygen (2) and nitrate reduction is part of normal P. aeruginosa biofilm development (2, 27, 28, 39).

At the lowest concentrations exhibiting synergistic killing of biofilms, CuSO4 (1 mM) and Polycide (25 ppm) were bacteriostatic and bactericidal to microaerobic cultures of P. aeruginosa ATCC 15442, respectively (Fig. 8a and b). Interestingly, cell lysates from P. aeruginosa grown in the presence of either of these compounds also had a significantly reduced capacity for nitrate reduction (Fig. 8c). Under these microaerobic conditions, a combination of CuSO4 (1 mM) plus Polycide (25 ppm) was bactericidal and showed approximately the same level of killing as Polycide used alone (Fig. 8a and b), as well as comparably reduced levels of NR activity. It is also worth noting that the addition of 1 mM KNO3 to the microaerobic growth medium (BHI broth, which contains an undefined amount of nitrates) partially alleviated toxicity and NR inhibition by CuSO4. Nonetheless, these results show that both Cu2+ and QACs, used alone and in combination, are able to reduce nitrate reduction activity by P. aeruginosa.

FIG. 8.

Cu2+ and Polycide, alone and in combination, negatively affect cell survival and nitrate (NO3) reduction in microaerobic P. aeruginosa ATCC 15442 cultures. Mean viable cell counts (a) and log killing of planktonic cell populations (b) were determined after exposure of cultures to these compounds. (c) NR activities of cytosolic components of microaerobically grown cells. In this figure, each bar represents the mean and standard deviation for three to eight independent replicates.

DISCUSSION

Biofilms of P. aeruginosa are very resilient to antimicrobials, and therefore, this organism serves as an excellent model for testing novel antibacterial agents. Since this microorganism is generally resistant to many biocides that are lethal to fungal pathogens (e.g., Candida spp.) as well as to other gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria (24), agents effective against P. aeruginosa are likely to be effective against biofilms of other organisms as well. Therefore, we systematically tested combinations of rationally selected metals and biocides against P. aeruginosa biofilms, looking for synergistic interactions. From a preliminary data set that identified several candidates, this process discerned that CuSO4 and various QACs exhibit synergy when used in combination to kill biofilms of P. aeruginosa ATCC 15442.

By definition, synergy occurs when two or more discrete agents act together to create an effect greater than the sum of the effects of the individual agents. In principle, synergy allows for a reduction in the quantity of agents used in combination yet might still allow for greater antimicrobial activity. Interestingly, we observed antagonism between Cu2+ and Polycide, particularly at higher concentrations of these agents, while at the same time, many combinations of lower concentrations exhibited a striking degree of synergy. This is strong evidence against using a “more is better” approach to formulating disinfectants and is the crux of these experiments, as combining the correct agents at the appropriate ratios may enhance the killing of microbial biofilms. Other advantages to using multiple, compatible agents in combination include lowering the probability that resistance will emerge and increasing the spectrum of microbicidal activity. We suggest that the latter advantage may be a useful principle in tailoring combinations of agents for use against bacterial biofilms, as adherent microbial populations produce phenotypic variants that reduce biofilm susceptibility to single-agent treatments (4, 8, 16, 30).

In this report, several sets of established rules for planktonic cell susceptibility testing (5, 25) were evaluated and adapted to mathematically define synergy, indifference, and antagonism for biofilm susceptibility testing. There are many different sets of rules in this field for susceptibility testing, such as those set by the AOAC or CLSI, and therefore, the experimental approach here was to test many different standard exposure conditions and to look for trends in the data to establish guidelines. In this manner, the final sets of rules in Materials and Methods were guided by the data generated in the course of this study. For instance, compared to the commonly observed eightfold range in MIC end points seen in planktonic cell broth microdilution assays, the MBCb end points discerned through the CBD biofilm susceptibility testing method had a relatively larger range (Table 2). For this reason, a 16-fold end-point range was used in setting the criteria to identify synergy or antagonism between combinations of antimicrobials against biofilms. The criteria used here for identifying antimicrobial synergy against biofilms thus were more stringent than those used in planktonic cell susceptibility testing. This is a reasonable cutoff, since one of the six identified candidate synergistic combinations of metals and biocides (Table 3) was shown to be falsely positive when it was tested more rigorously (Fig. 2).

A final challenge was setting criteria to identify synergy from viable cell counts. For 24 h of exposure, the 100-fold rule for synergy, which looks for a 2-log10 increase in the killing of biofilms by two agents in combination compared to that by single-agent treatments, was taken directly from Instructions to Authors (2008) for the journal Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. However, this rule cannot be applied to shorter exposure times, such as those required by the AOAC for the testing of hard surface disinfectants. The data here (Tables 2 and 3; Fig. 3) illustrate that biofilms are killed time dependently by antimicrobial agents, so a 10-fold rule for synergy was applied in cases with a 5-, 10-, or 30-min exposure time. In other words, a combination was considered synergistic if there was a 1-log10 increase in killing of the biofilms by two agents in combination compared to that by single-agent treatments with 30 min of exposure or less.

Although the explicit focus of this report is biofilm susceptibility testing, combinations of Cu2+ and QACs also killed planktonic cells of P. aeruginosa ATCC 15442 at concentrations that were at least 10-fold less than the concentrations required to treat biofilms (J. J. Harrison, D. J. Joo, R. J. Turner, and H. Ceri, unpublished data). This is consistent with a previous study by Bjarnsholt et al. (3), who found that Ag+ was effective at treating P. aeruginosa biofilms but that 10- to 100-fold higher concentrations were required to eradicate the surface-adherent populations than those required for planktonic cells. This is also consistent with previous reports from our research group showing that metal cations and oxyanions may eradicate biofilms in both a concentration- and time-dependent manner (14, 15, 18).

The ITC data presented in this study, which show that Cu2+ and QACs do not interact in aqueous milieus, suggest that the mechanisms of Cu2+ and QAC toxicities are (bio)chemically independent of one another. To date, we have not successfully identified a biochemical mechanism that accounts for the synergistic toxicity of Cu2+ and QACs to P. aeruginosa. However, there is quite a bit of information concerning the chemical mechanisms of Cu2+ and QAC toxicities when these agents are used alone, as well as information about the (chromosomally mediated) mechanisms of bacterial resistance.

Bacterial cell membranes are sites of QAC toxicity (24), and it is thought that these cationic agents generally have a target site at the cytosolic membrane. QACs likely act on the phospholipid components of the membrane, causing membrane deformation, leakage of low-molecular-weight intracellular material, and disruption of the proton motive force (24). This model of toxicity is supported by evidence that P. aeruginosa may change the composition of its membrane fatty acids in response to QAC exposure (12). In contrast, Cu2+ is an electrophile that likely exerts microbiological toxicity through several biochemical routes simultaneously. This includes autocatalytic formation of ROS via Fenton-type chemistry, oxidation of cellular protein thiols, and the displacement of similar transition metal ions (e.g., Fe3+) from the binding sites of other biomolecules (16, 31). In all of these cases, Cu2+ alters the normal biological function of cellular macromolecules in a detrimental fashion. The present study also suggests that both Cu2+ and QACs negatively affect P. aeruginosa nitrate reduction, and this too could be a mechanism of toxicity to biofilms. Determining whether this effect is due to alterations in gene expression or to direct inhibition of cytosolic or membrane-bound NRs is a logical direction for future investigation.

Although the discovery of synergy between Cu2+ and QACs is a novel means for biofilm disinfection, these compounds have been used in combination in the forest industry for more than 15 years. Ammoniacal copper quaternary (ACQ) is a combination of copper oxide (CuO) with the QAC didecyldimethylammonium chloride (DDAC) that has been used as a fungicidal and insecticidal wood preservative since the early 1990s. ACQ is considered environmentally friendly, and it is estimated that in 1996, 454,000 kg of DDAC was released into the environment in British Columbia, Canada, for this purpose alone (20). The synergy between Cu2+ and QACs described in this study may be an explanation for the effectiveness of ACQ as a wood preservative. Furthermore, this indicates that ACQ as well as other Cu-QAC combinations might be applied successfully to treat biofilms in a wide range of additional environments where surface-associated microbial growth is unwanted or damaging.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported through discovery grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada to R.J.T. and H.C. The Canadian Institute for Health Research supported this research through a grant to R.J.T. The Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research (AHFMR) also supported this research through Forefront Block grant funds administered by University Technologies International and awarded to J.J.H., H.C., and R.J.T. The NSERC also provided an Industrial Postgraduate Scholarship and a Canada Graduate Scholarship doctoral award to J.J.H., who was additionally supported by a Ph.D. studentship from the AHFMR. M.A.S. was supported by a studentship from the University of Calgary Undergraduate Student Research Program in Health and Wellness. CLSM was made possible through a Canadian Foundation for Innovation (CFI) Bone and Joint Disease Network grant to H.C. The Alberta Science and Research Investments Program also supported this project through a grant to H.C. Corporate funding was provided by Innovotech Inc.

We thank FeF Chemicals for donating the quaternary ammonium compounds used in this study. Thanks go to Aaron Yamniuk for expert assistance with ITC and to the CFI CyberCell initiative for funding access to the biophysics laboratory in the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Calgary.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 2 June 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander, E., D. Pham, and T. R. Steck. 1999. The viable-but-nonculturable condition is induced by copper in Agrobacterium tumefaciens and Rhizobium leguminosarum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3754-3756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez-Ortega, C., and C. S. Harwood. 2007. Responses of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to low oxygen indicate that growth in the cystic fibrosis lung is by aerobic respiration. Mol. Microbiol. 65:153-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bjarnsholt, T., K. Kirketerp-Moller, S. Kristiansen, R. Phipps, A. K. Neilsen, P. O. Jensen, N. Hoiby, and M. Givskov. 2007. Silver against Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. APMIS 115:921-928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boles, B. B., M. Theondel, and P. K. Singh. 2004. Self-generated diversity produces “insurance effects” in biofilm communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:16630-16635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonapace, C. R., J. A. Bosso, L. V. Friedrich, and R. L. White. 2002. Comparison of methods of interpretation of checkerboard synergy testing. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 44:363-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ceri, H., M. E. Olson, C. Stremick, R. R. Read, D. W. Morck, and A. G. Buret. 1999. The Calgary biofilm device: new technology for rapid determination of antibiotic susceptibilities in bacterial biofilms. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1771-1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies, J. A., J. J. Harrison, L. L. R. Marques, G. R. Foglia, C. A. Stremick, D. G. Storey, R. J. Turner, M. E. Olson, and H. Ceri. 2007. The GacS sensor kinase controls phenotypic reversion of small colony variants isolated from biofilms of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 59:32-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drenkard, E., and F. M. Ausubel. 2002. Pseudomonas biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance are linked to phenotypic variation. Nature 416:740-743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freyer, M. W., and E. A. Lewis. 2008. Isothermal titration calorimetry: experimental design, data analysis, and probing macromolecule/ligand binding and kinetic interactions. Methods Cell Biol. 84:79-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilbert, P., J. R. Das, M. V. Jones, and D. G. Allison. 2001. Assessment of resistance towards biocides following the attachment of microorganisms to, and growth on, surfaces. J. Appl. Microbiol. 91:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grey, B., and T. R. Steck. 2001. Concentrations of copper thought to be toxic to Escherichia coli can induce the viable but nonculturable condition. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:5325-5327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guerin-Mechin, L., F. Dubois-Brissonnet, B. Heyd, and J. Y. Leveau. 1999. Specific variations of fatty acid composition of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 15442 induced by quaternary ammonium compounds and relation to resistance to bactericidal activity. J. Appl. Microbiol. 87:735-742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall-Stoodley, L., J. W. Costerton, and P. Stoodley. 2004. Bacterial biofilms: from the natural environment to infectious diseases. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2:95-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harrison, J. J., H. Ceri, N. J. Roper, E. A. Badry, K. M. Sproule, and R. J. Turner. 2005. Persister cells mediate tolerance to metal oxyanions in Escherichia coli. Microbiology 151:3181-3195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harrison, J. J., H. Ceri, C. Stremick, and R. J. Turner. 2004. Biofilm susceptibility to metal toxicity. Environ. Microbiol. 6:1220-1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harrison, J. J., H. Ceri, and R. J. Turner. 2007. Multimetal resistance and tolerance in microbial biofilms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5:928-938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harrison, J. J., H. Ceri, J. Yerly, M. Rabiei, Y. Hu, R. Martinuzzi, and R. J. Turner. 2007. Metal ions may suppress or enhance cellular differentiation in Candida albicans and Candida tropicalis biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:4940-4949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harrison, J. J., R. J. Turner, and H. Ceri. 2005. Persister cells, the biofilm matrix and tolerance to metal cations in biofilm and planktonic Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Environ. Microbiol. 7:981-994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones, R. W., and P. B. Garland. 1977. Sites and specificity of the reaction of bipyridylium compounds with anaerobic respiratory enzymes of Escherichia coli: effects of permeability barriers imposed by the cytoplasmic membrane. Biochem. J. 164:199-211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Juergensen, L., J. Busnarda, P.-Y. Caux, and R. A. Kent. 2000. Fate, behaviour, and aquatic toxicity of the fungicide DDAC in the Canadian environment. Environ. Toxicol. 15:174-200. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaneko, Y., M. Theondel, O. Olakanmi, B. E. Britigan, and P. K. Singh. 2007. The transition metal gallium disrupts Pseudomonas aeruginosa iron metabolism and has antimicrobial and antibiofilm activity. J. Clin. Investig. 117:877-888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewis, K. 2007. Persister cells, dormancy and infectious disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5:48-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Magalon, A., R. A. Rothery, D. Lemesle, C. Frixon, J. H. Weiner, and F. Blasco. 1998. Inhibitor binding within the NarI subunit (cytochrome bnr) of Escherichia coli nitrate reductase A. J. Biol. Chem. 273:10851-10856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McDonnell, G., and A. D. Russell. 1999. Antiseptics and disinfectants: activity, action and resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 12:147-179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moody, J. A. 1995. Synergism testing: broth microdilution checkerboard and broth macrodilution methods, p. 5.18.1-5.18. 28. In H. D. Isenberg and J. Hindler (ed.), Clinical microbiology procedures handbook, vol. 1. ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ordax, M., E. Marco-Noales, M. M. López, and E. G. Biosca. 2006. Survival strategy of Erwinia amylovora against copper: induction of the viable-but-nonculturable state. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:3482-3488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palmer, K. L., L. M. Aye, and M. Whiteley. 2007. Nutritional cues control Pseudomonas aeruginosa behaviour in cystic fibrosis sputum. J. Bacteriol. 189:8079-8087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palmer, K. L., S. A. Brown, and M. Whiteley. 2007. Membrane-bound nitrate reductase is required for anaerobic growth in cystic fibrosis sputum. J. Bacteriol. 189:4449-4455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sandt, C., J. Barbeau, M.-A. Gagnon, and M. Lafleur. 2007. Role of the ammonium group in the diffusion of quaternary ammonium compounds in Streptococcus mutans biofilms. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 60:1281-1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spoering, A., and K. Lewis. 2001. Biofilm and planktonic cells of Pseudomonas aeruginosa have similar resistance to killing by antimicrobials. J. Bacteriol. 183:6746-6751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stohs, S. J., and D. Bagchi. 1995. Oxidative mechanisms in the toxicity of metal ions. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 18:321-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takeo, Y., S. Oie, A. Kamiya, H. Konishi, and T. Nakazawa. 1994. Efficacy of disinfectants against biofilm cells of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbios 79:19-26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Teitzel, G. M., A. Geddie, S. K. De Long, M. J. Kirisits, M. Whiteley, and M. R. Parsek. 2006. Survival and growth in the presence of elevated copper: transcriptional profiling of copper-stressed Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 188:7242-7256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Teitzel, G. M., and M. R. Parsek. 2003. Heavy metal resistance of biofilm and planktonic Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:2313-2320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tobey, S. L., and E. V. Anslyn. 2003. Energetics of phosphate binding to ammonium and guanidinium containing metallo-receptors in water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125:14807-14815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vievskii, A. N. 1994. The synergistic action of quaternary ammonium derivatives and inhibitors of nitrate reduction in respect to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mikrobiol. Zh. 56:16-20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wood, P., D. E. Caldwell, E. Evans, M. Jones, D. R. Korber, G. M. Wolfhaardt, M. Wilson, and P. Gilbert. 1998. Surface-catalysed disinfection of thick Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. J. Appl. Microbiol. 84:1092-1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Workentine, M. L., J. J. Harrison, P. U. Stenroos, H. Ceri, and R. J. Turner. 2008. Pseudomonas fluorescens view of the periodic table. Environ. Microbiol. 10:238-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoon, S. S., R. F. Hennigan, G. M. Hilliard, U. A. Ochsner, K. Parvatiyar, M. C. Kamani, H. L. Allen, T. R. DeKievit, P. R. Gardner, U. Schwab, J. J. Rowe, B. H. Iglewski, T. R. McDermott, R. P. Mason, D. J. Wozniak, R. E. Hancock, M. R. Parsek, T. L. Noah, R. C. Boucher, and D. J. Hassett. 2002. Pseudomonas aeruginosa anaerobic respiration in biofilms: relationships to cystic fibrosis pathogenesis. Dev. Cell 3:593-603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]