Abstract

A number of important helminth parasites of humans have incorporated short-term residence in the lungs as an obligate phase of their life cycles. The significance of this transient pulmonary exposure to the infection and immunity is not clear. Employing a rodent model of infection with hookworm (Nippostrongylus brasiliensis), we characterized the long-term changes in the immunological status of the lungs induced by parasite infection. At 36 days after infection, alterations included a sustained increase in the transcription of both Th2 and Th1 cytokines as well as a significant increase in the number and frequency of alveolar macrophages displaying an alternatively activated phenotype. While N. brasiliensis did not induce alternate activation of lung macrophages in STAT6−/− animals, the parasite did induce a robust Th17 response in the pulmonary environment, suggesting that STAT6 signaling plays a role in modulating Th17 immunity and pathology in the lungs. In the context of the cellular and molecular changes induced by N. brasiliensis infection, there was a significant reduction in overall airway responsiveness and lung inflammation in response to allergen. In addition, the N. brasiliensis-altered pulmonary environment showed dramatic alterations in the nature and number of genes that were up- and downregulated in the lung in response to allergen challenge. The results demonstrate that even a transient exposure to a helminth parasite can effect significant and protracted changes in the immunological environment of the lung and that these complex molecular and cellular changes are likely to play a role in modulating a subsequent allergen-induced inflammatory response.

Historically, an infection with one or multiple helminth parasites has been essentially universal for human populations. It is estimated that a majority of living humans have a history of or are currently infected with a helminth parasite, with the highest prevalence of exposure in developing areas (11). A number of important helminth parasites such as hookworm, Ascaris, and Schistosoma have incorporated a short-term residence in the lungs as an obligate phase of their life cycle. The significance of the lung phase to the developmental biology of these parasites has not been clearly defined. Equally unclear is the impact that the pulmonary phase has on the immunobiology and pathogenesis of infection and the nature and extent to which the immunological environment of the lung is altered by these transient exposures. If significant changes to the pulmonary environment do ensue, to what extent do they influence the level and nature of the responses to subsequent challenges from bacteria, fungi, viruses, and allergens?

In recent decades, the incidence and prevalence of allergy and asthma have increased dramatically in industrialized nations, with no comparable increase in developing regions of the world (3, 9, 10, 39). Although a number of factors have been proposed to explain this difference in disease prevalence in developed and developing regions, including vaccination rates, differential exposure to certain environmental and pathogenic microorganisms, antibiotic usage, and general levels of hygiene (63), there is a particularly strong negative correlation between helminth infection and allergy (52, 67). Upon initial inspection, this inverse relationship appears to present a paradox. Helminth infections, like allergens, induce a robust Th2 response characterized by interleukin-4 (IL-4), IL-13, and IL-5 production. However, instead of potentiating allergy, a previous or ongoing helminth infection significantly reduces the level of reactivity to allergen challenge (60, 64, 65). While a role for helminth-induced regulatory T cells has been established as a component of the mechanism that modulates allergic reactivity (64), it is likely that there are additional mechanisms involved in regulating pulmonary immunity.

To study the long-term changes in the lungs that ensue from helminth infection, we employed a mouse model of human hookworm infection. The rodent hookworm Nippostrongylus brasiliensis has been used extensively to study the regulation of immunoglobulin E (IgE) synthesis (21) and Th2 immunity in general, as it is one of the strongest inducers of a polarized Th2 immune response (1, 29, 48). The life cycle of N. brasiliensis parallels that of its human counterparts Necator americanus and Ancyclostoma duodenale. Briefly, infectious third-stage larvae (L3) penetrate the skin, enter the circulation, and within hours arrive in the lungs, where they reside for 18 to 24 h. After molting, larvae migrate from alveoli up the trachea, are swallowed, and develop into adult nematodes in the small intestine, where they attach, feed, and reproduce. Healthy BALB/c mice expel N. brasiliensis at 10 to 11 days postinfection (p.i.) through an IL-13/STAT6-dependent mechanism (56). Almost immediately upon entry into the lungs, the larvae induce a strong innate immune response characterized by the rapid production of IL-4 and IL-13 and the alternative activation of alveolar macrophages (43). Although the structural damage and inflammation quickly resolve, a number of the cellular and molecular changes induced by the transient presence of larvae endure through day 12 p.i. (43). In the work reported here, we characterized the nature of the persistent N. brasiliensis-induced immunological changes that define a permanent change to the immunological status of the lungs. This work represents the first account of the protracted molecular and cellular changes that take place in the lungs as a consequence of a helminth infection and the role that these changes might have in altering responses to environmental antigens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal model. (i) Helminth infection.

Male BALB/cJ and STAT6−/− (on a BALB/cJ background) mice, 6 to 8 weeks of age, were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were serologically negative for 53 bacterial, viral, fungal, and parasitic agents as tested by Jackson Laboratory surveillance and sentinel monitoring through Johns Hopkins University. All experimental procedures described in this paper were performed under the approval of the Johns Hopkins University Animal Care and Use Committee in accordance with the guidelines set out by the Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources 1996 Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Mice were housed in filter top microisolator cages, provided food and water ad libitum, and kept on a 12-hour light/dark cycle. Infectious Nippostrongylus brasiliensis L3 were harvested from a fecal culture via a Baermann apparatus, washed multiple times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and counted. Mice were infected subcutaneously with 500 L3.

(ii) Allergen sensitization and challenge.

Mice were sensitized with two intraperitoneal injections of 75 allergy units of house dust mite (HDM) Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus allergen extract (Greer, Lenoir, NC) bound to 1 mg of Imject aluminum hydroxide (Pierce, Rockford, IL) on days 21 and 25 post-N. brasiliensis infection. Challenge doses of 50 allergy units HDM in 50 μl PBS were administered intranasally on days 35 and 36 post-N. brasiliensis infection to anesthetized (isofluorane; Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL) animals. Control animals received 50 μl of lipopolysaccharide-free, injectable PBS.

(iii) Anesthesia and euthanasia.

Prior to tissue harvest or histological preparation of lungs, mice were anesthetized with 300 mg/kg of Avertin (2,2,2-tribromoethanol) administered intraperitoneally. Euthanasia was performed by an overdose of Avertin.

Histology. (i) Histological preparation.

Lungs, inflated and fixed as outlined previously (43), were embedded in paraffin, and sagittal 5-μm sections were obtained from four different levels of the lung. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or by the periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) method (28) to identify mucus-producing goblet cells. Selected sections were stained with Prussian blue to confirm the presence of Ferric (Fe3+) ion consistent with hemosiderin pigment (28).

(ii) Immunohistochemistry.

YM1 staining was performed using affinity-purified goat anti-mouse YM1 (1 μg/ml; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Anti-YM1 was detected using a biotinylated rabbit anti-goat IgG (Vector Laboratories), peroxidase strepavidin, and 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Vector Laboratories). YM1-positive cells were counted in each of six contiguous lung histological fields (10× magnification; 974 mm2/field), and the mean cell number per field was calculated. For dual-fluorescence staining of macrophages, YM1 was resolved with fluorescein-avidin DCS (Vector Laboratories), and, after an avidin-biotin blocking step (Vector Laboratories), CD11c (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) binding was detected with Texas red-avidin DCS. Stained sections were mounted in Vectashield containing 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Vector Laboratories) and examined using Nikon Eclipse series microscopes (Nikon Inc., Melville, NY) equipped with a Spot Flex charge-coupled device camera (Diagnostic Instruments Inc., Sterling Heights, MI).

(iii) Histological scoring system.

Scoring was performed under blinded conditions for the number of eosinophils, goblet cells, pigmented macrophages, and neutrophils from three sections representative of three different strata of the lung for each of three mice per treatment group. The scoring scale is detailed in the legend to Fig. 5. Statistical significance was determined using a two-tailed paired Student t test.

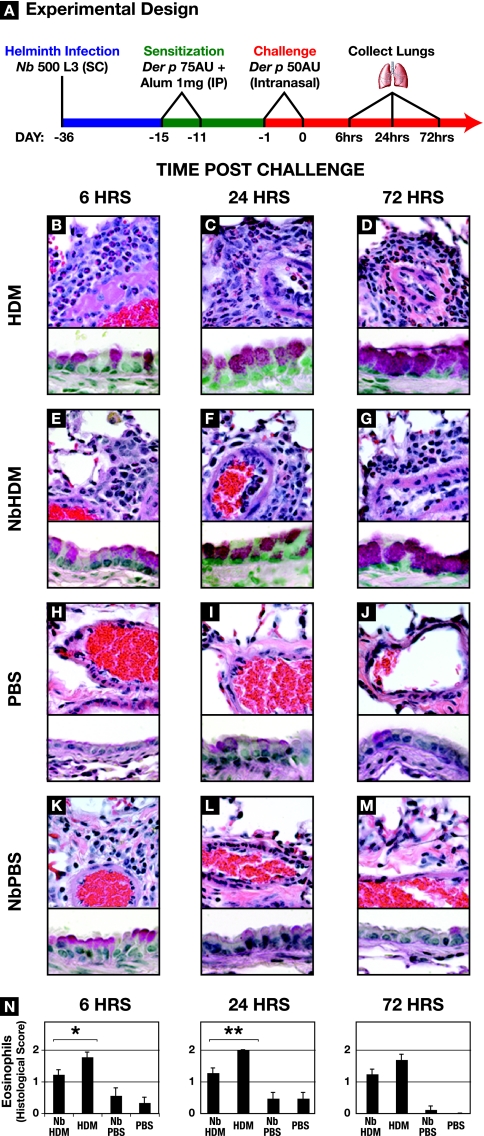

FIG. 5.

N. brasiliensis (Nb) infection dampens allergen-induced inflammation. (A) Schedule for HDM (Der p) sensitization and challenge of uninfected or N. brasiliensis-infected BALB/c mice. (B to M) Lungs were harvested, fixed, and sectioned for histological examination at 6, 24, or 72 h after the second challenge dose of HDM. The upper portions of the panels were stained with H&E, the lower parts were stained with PAS, and both were photographed at a magnification of ×60. HDM, uninfected mice sensitized and challenged with Der p; NbHDM, day 36 p.i. mice sensitized and challenged with Der p;PBS; uninfected mice exposed to PBS; NbPBS, day 36 p.i. mice exposed to PBS. (N) Quantification of the eosinophil infiltrate. Eosinophil scoring was performed under blinded conditions from three sections representative of three different strata of the lung for each of three mice per treatment group. Scoring was as follows: 0, no eosinophils; 0.5, scattered eosinophils throughout the lung; 1.0, 10 to 40% of the perivascular infiltrate; 1.5, 50 to 60% of the perivascular infiltrate; 2.0, >70% of the perivascular infiltrate.

Gene expression analysis. (i) Total RNA extraction.

Lungs were harvested, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Lung RNA was isolated as outlined by Reece et al. (43). RNA quality was determined by RNA Nano LabChip analysis on an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA). An RNeasy total RNA cleanup protocol (Qiagen) was performed, followed by spectrophotometric assessment of RNA concentration. The lungs from three animals were independently processed for each treatment group and each time point.

(ii) Affymetrix GeneChip protocols.

Processing of templates and hybridization for the 430 2.0 array GeneChip (Affymetrix Inc, Santa Clara, CA) were in accordance with methods described in the Affymetrix GeneChip expression analysis technical manual, revision Three, as previously described (20). Following hybridization, the GeneChips were washed and stained in an automated fluidics station (Affymetrix FS450) and then assessed using the GCS3000 laser scanner (Affymetrix) at an emission wavelength of 570 nm at 2.5-μm resolution. The intensity of hybridization for each probe pair was computed by GCOS 1.2 software (Affymetrix). (For more detailed methods, refer to the website of the Malaria Research Institute Gene Array Core Facility at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health [http://jhmmi.jhsph.edu]).

(iii) Data analysis.

Affymetrix CEL file data was preprocessed for use with the probe-level GeneChip robust multiarray analysis (66) option in GeneSpring 7 software (Agilent Technologies). Initial filtering by probe intensity for raw levels above 150 in at least 1 out of 16 conditions resulted in a list of 14,159 genes that were then used as the basis for selecting differentially regulated genes. Raw intensity values ranged from 150 to 51,838.

(iv) Real-time RT-PCR.

From each treatment group and time point, 1 μg of lung RNA was reverse transcribed using the SuperScript first-strand synthesis system for reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) (Invitrogen) with an oligo(dT) primer. The resultant cDNAs were amplified for real-time detection with fluorogenically labeled probes in assays specific for each target gene. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was performed using the Applied Biosystems 7500 real-time PCR system, TaqMan Gene Expression Assays-on-Demand, and TaqMan Universal Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The following assays (Applied Biosystems product numbers) were used: Arg1 (Mm00475988_m1), CD11c (Mm00498698_m1), FIZZ1 (Mm00445109_m1), gamma interferon (IFN-γ) (Mm00801778_m1), IL-10 (Mm00438616_m1), IL-12 (Mm00434165_m1), IL-13 (Mm00434204_m1), IL-17a (Mm00439619_m1), IL-1β (Mm00434228_m1), IL-21 (Mm00517640_m1), IL-4 (Mm00445259_m1), IL-5 (Mm00439646_m1), IL-6 (Mm00446190_m1), inducible nitric oxide synthase (Mm00440485_m1), Mrc1 (Mm00485148_m1), transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) (Mm00441724_m1), Ym1 (Mm00657889_mH), and Ym2 (Mm00840870_m1). Reactions were performed using 1 μl of cDNA in a 25-μl sample volume and the following thermal cycler profile: 10 min of denaturation at 95°C, 50 cycles of 1 min of extension at 60°C, and then 15 seconds of denaturation at 95°C. Analysis was performed using the 7500 system SDS software package (Applied Biosystems).

Lung monocyte preparations.(i) Lung digestions.

Animals were deeply anesthetized by overdose and tracheotomized, followed by a bronchial alveolar lavage three times with 1 ml of room-temperature PBS. Lungs were infused with 10 ml of room-temperature PBS, removed, and suspended in 5 ml of 1-mg/ml collagenase type II (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA) with 30 μg/ml DNase I (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) in RPMI 1640 (Gibco). Tissue was minced thoroughly, incubated at 37°C for 30 min, and then forced through a 3-ml transfer pipette 10 times. A collagenase-DNase solution (3 ml) was added, and samples were incubated for an additional 15 min at 37°C. The resulting suspensions were manually homogenized using a syringe plunger and passed through a 100-μm nylon cell strainer (BD Falcon, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Cell suspensions were spun for 3 min at 1,500 × g (4°C), and pellets were resuspended in 5 ml of ACK lysing buffer (Quality Biological Inc., Gaithersburg, MD) for 5 min at room temperature. Suspensions were then passed through a fresh cell strainer, and cells were washed twice in fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) staining buffer (PBS, 2% heat inactivated fetal calf serum).

(ii) CDllc+ cell isolation.

Lung-derived cells were suspended in 200 μl of staining buffer containing Fc Block (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) and incubated on ice for 5 min. The cells were incubated with allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-CD11c (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) for 30 min on ice and then washed twice with staining buffer. The cells were resuspended 50 μl of BD IMag-DM antiallophycocyanin particle solution (BD Pharmingen) and incubated on ice for 30 min. CD11c isolation was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol using the BD IMag Cell Separation System (BD Pharmingen).

FACS staining and detection: surface phenotyping.

Cell counts were performed on a standard hemacytometer with dead cells excluded by trypan blue stain (Gibco). Cells were incubated with anti-major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II-phycoerythrin (PE) (eBioscience), anti-CD206-PE (Serotec, Raleigh, NC), or anti-F4/80 plus 2° PE (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) in FACS staining buffer for 30 min on ice in the dark. Data were acquired by running samples on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer using Cell Quest software (BD Biosciences, Mountain View, CA). Data were analyzed using FloJo software (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR).

In vivo pulmonary function measurement.

Mice were deeply anesthetized with a mixture of 70 mg/kg Ketamine and 14 mg/kg Xylazine (both from Phoenix Pharm., St. Joseph, MO) delivered intraperitoneally. The trachea was exposed by dissection and cannulated using a 19-gauge blunt needle. Animals were ventilated with a FlexiVent (Scireq, Montreal, Quebec, Canada) at a rate of 150/min with a delivered tidal volume of 8 ml/kg and a positive-end expiratory pressure of 3 cm H2O. To eliminate measurement noise associated with small respiratory efforts, deeply anesthetized mice were paralyzed with 1 mg/kg succinylcholine (Hospira Inc., Lake Forest, IL) intraperitoneally. Respiratory resistance and elastance were calculated during a 2-second sinusoidal oscillation controlled by the FlexiVent 5 software. Measurements were made at baseline and during cumulative aerosolized methacholine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) dose-response curves, continuing until resistance doubled (8). The methacholine doses were delivered into the inspiratory line, each for a 10-s period using an Aeroneb Pro micropump ultrasonic nebulizer (Nektar Therapeutics, Mountain View, CA). Measurements of resistance were expressed in absolute terms (cm H2O/ml/s) and as percentages of the baseline values.

Statistical analyses.

Microarray data, numerical histological data, and real-time RT-PCR data were analyzed using a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with variables of treatment group and time. In vivo pulmonary function measurements of dose responses to methacholine were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA with variables of infection status and methacholine dose. Differences in baseline resistance and doubling dose of methacholine were calculated using one-way ANOVAs. Significant interactions were further analyzed using Bonferroni posttesting for pairwise multiple comparisons. All other data were analyzed using a two-tailed Student t test for pairwise comparisons of infected and uninfected animals. Differences were considered statistically significant if the P value was <0.05.

GEO accession number.

The data discussed in this publication have been deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) and are accessible through GEO series accession number GSE5555.

RESULTS

N. brasiliensis induces persistent changes in the lung.

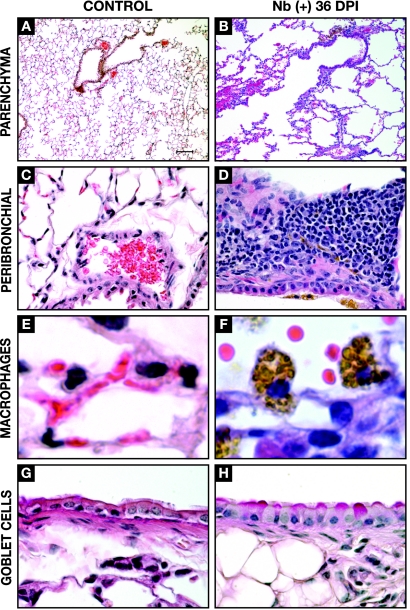

The results of previous studies demonstrated that N. brasiliensis larvae induce molecular and cellular changes in the lung that are still evident days after the parasites have exited the pulmonary environment (30, 43, 65). These observations suggested that the transient presence of N. brasiliensis could result in lasting changes in the immunological status of the lungs. To test this, we evaluated the phenotypic and immunological status of the lungs at 36 days p.i. (34 to 35 days after the larvae exit the lungs and 25 to 26 days after the adults are expelled from the intestine). Histologically, N. brasiliensis larvae caused a disruption of the alveolar architecture of the lungs resulting in focal emphysema-like changes (Fig. 1A and B). Although the perivascular inflammation that was visible in the first 72 h p.i. (reference 43 and data not shown) had resolved, areas of peribronchiolar mononuclear infiltration were still evident at 36 days p.i. (Fig. 1D). In contrast to the lungs from noninfected animals (Fig. 1E), the lungs from N. brasiliensis-infected animals contained a large number of conspicuous, heavily pigmented macrophages (Fig. 1F). Approximately 10 to 20% of the bronchiolar epithelial cells were goblet cells at 36 days p.i. (Fig. 1H), which was significantly more than the 1 to 2% observed in noninfected controls (Fig. 1G) but below the >30% present at 4 days p.i. (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Cellular and structural changes in the lungs at 36 days post-N. brasiliensis (Nb) infection. Light microscopy of the lungs from uninfected (control) and N. brasiliensis-infected (day 36 p.i.) BALB/c mice is shown. Histological analysis illustrates focal emphysema-like lesions resulting from parasite migration (A and B) (magnification, ×10; H&E stain), peribronchial infiltration (Panels C & D, 40x magnification, H&E stain), the presence of large alveolar macrophages containing pigmented granules (E and F) (magnification, ×100; H&E stain), and an increase in the number of goblet cells (H) (magnification, ×60; PAS stain).

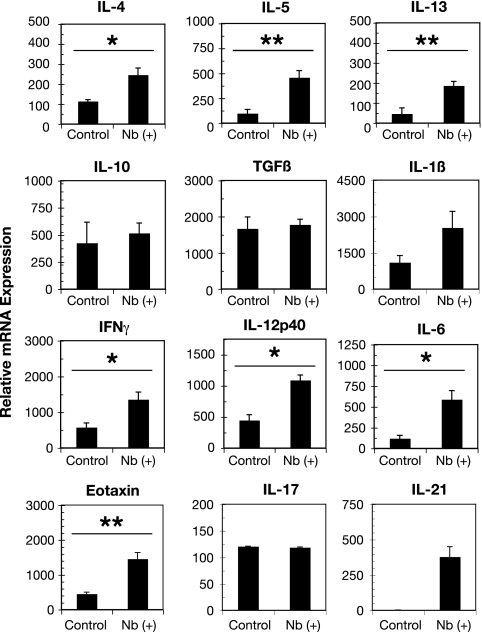

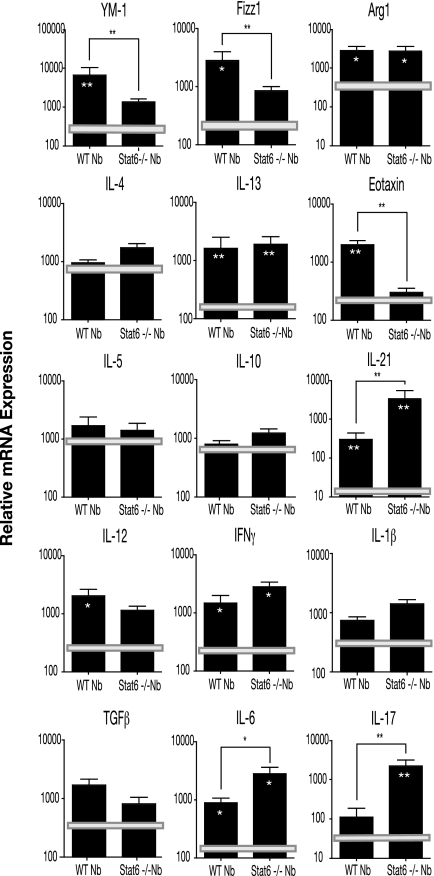

To gain an idea of the type of immunological changes that were induced by N. brasiliensis at 36 days p.i., real-time RT-PCR was used to measure the steady-state expression levels of selected cytokines from infected and noninfected lungs. The constitutive expression levels of the Th2 cytokines IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 were elevated in the lungs from N. brasiliensis-infected animals compared to those of noninfected controls (Fig. 2). By way of comparison, the IL-4 expression level at day 36 p.i. was sixfold lower than the level at day 8 p.i., the peak of the initial larva-induced inflammatory response in the lungs (43, 49, 65). IL-13 and IL-5 expression levels at days 8 and 36 p.i. were comparable (data not shown). Consistent with these observations, eotaxin/CCL11 transcription was also significantly increased compared to that in control lungs. Interestingly, the baseline transcription levels of the Th1 cytokines IFN-γ, IL-12p40, and IL-6 were also elevated in the lungs from N. brasiliensis-infected mice. These expressions levels for IFN-γ and IL-6 at day 36 p.i. were 20-fold and 4-fold higher than those measured at day 8 p.i., respectively (reference 43 and data not shown). The expression levels of IL-12p40 did not significantly differ between days 8 and 36 p.i. Although the expression level of IL-1β was elevated, the increase was not statistically significant. Expression levels of the regulatory cytokines IL-10 and TGF-β and the proinflammatory cytokine IL-17 (47) were not elevated as a consequence of N. brasiliensis infection. In contrast, IL-21 transcription (Fig. 2) was significantly elevated after N. brasiliensis infection compared to that in noninfected control lungs. The histological, cellular, and transcriptional changes demonstrate that the brief exposure to N. brasiliensis larvae effects persistent and substantive changes to the immunological status of the lungs.

FIG. 2.

N. brasiliensis (Nb) induces an altered cytokine environment. Lungs from mice at 36 days p.i. were harvested and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, RNA was extracted using Trizol, and first-strand DNA was synthesized. Real-time RT-PCR analysis of whole lungs for Th1, Th2, and regulatory cytokines, as well as eotaxin (CCL11) and IL-21, is shown. Bars represent the mean levels from five mice ± standard errors of the means. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

N. brasiliensis alters the baseline of gene expression in the lung.

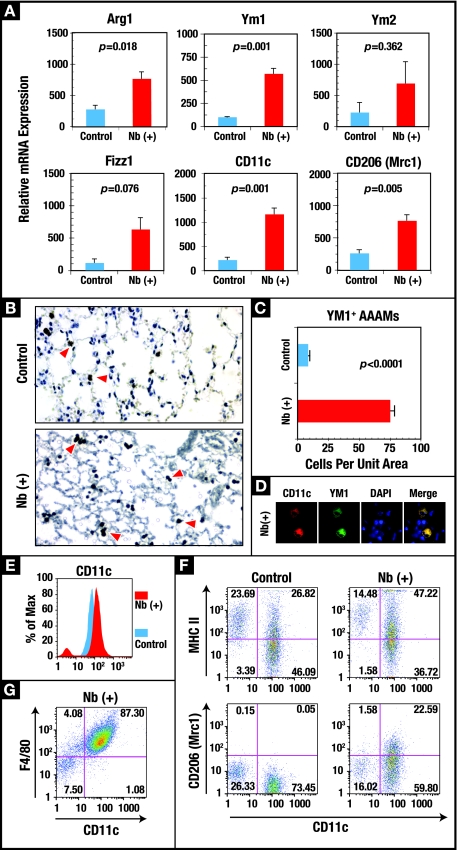

In order to gain a more comprehensive picture of the overall effect of helminth infection on the immunological status of the lung 36 days p.i., microarray technology was employed to characterize expression profiles in the lungs from infected and control animals. Roughly 120 genes were significantly (P < 0.05) differentially expressed in the lungs at day 36 p.i. compared to the lungs from age-matched controls (Table 1; see Table S1 in the supplemental material). There was a significant increase in a number of genes associated with lung remodeling and a persistent increase in the expression of genes that encode molecules important for macrophage function and macrophage regulation, including class II MHC, CD11c, PPAR gamma, MRP-1/ccl6, MCP-2/ccl8 Mac-1, and eosinophil-associated RNase (Ear2). Notably, there was a significant upregulation of genes associated with alternatively activated macrophages (AAMs), i.e., fizz1, ym1, and ym2, which was validated by real-time RT-PCR (Table 1; Fig. 3A). Two additional genes associated with AAMs, those for arginase 1 (arg1) and the mannose receptor 1 (mrc1, CD206), while not significantly elevated in the microarray results, were significantly upregulated in real-time RT-PCR analysis (Fig. 3A).

TABLE 1.

N. brasiliensis alters baseline gene expression in the lung

| Category and Affymetrix probe no. | Common name | GenBank accession no. | Change in gene expression (fold)a | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative macrophages | ||||

| 1449015_at | FIZZ1 | NM_020509 | +++ | Resistin like alpha |

| 1419764_at | YM1 | NM_009892 | ++ | Chitinase 3-like 3 |

| 1425451_s_at | YM2 | NM_145126 | ++ | Chitinase 3-like 4 |

| Macrophage associated | ||||

| 1449401_at | C1qg | NM_007574 | ++ | Complement component 1, q subcomponent |

| 1419128_at | CD11c | NM_021334 | ++ | Itgax, integrin alpha X |

| 1419627_s_at | Dectin 2 | NM_020001 | ++ | Clecsf10, C-type lectin domain fam 4, member n |

| 1449846_at | Ear2 | AF306665 | ++ | Eosinophil-associated, ribonuclease A |

| 1451941_a_at | Fcγr2b | M14216 | ++ | Fc receptor, IgG, low affinity IIb |

| 1427747_a_at | Lcn2 | X14607 | ++ | Lipocalin 2, neutrophil gelatinase-assoc lipocalin |

| 1450678_at | Mac-1 | NM_008404 | ++ | Itgb2, integrin beta 2 |

| 1449164_at | Macrosialin | BC021637 | ++ | CD68, Mac marker; late endosomal |

| 1421044_at | Mrc2 | NM_008626 | ++ | Mannose receptor, C type 2 |

| 1420715_a_at | PPARγ | NM_011146 | ++ | Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma |

| MHC | ||||

| 1451721_a_at | H2-Ab1 | M15848 | ++ | MHC class II, beta chain |

| 1451644_a_at | H2-Q1 | BC010602 | +++ | B2M-associated MHC class I molecule |

| Chemokines | ||||

| 1417266_at | CCL 6 | BC002073 | ++ | MRP-1, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 6 |

| 1419684_at | CCL 8 | NM_021443 | ++++ | MCP-2, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 8 |

| 1417789_at | CCL 11 | NM_011330 | +++ | Eotaxin, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 11 |

| Lung remodeling | ||||

| 1416454_s_at | Acta2 | NM_007392 | ++ | Actin, alpha 2, cytoskeleton biogenesis |

| 1450652_at | Ctsk | NM_007802 | ++ | Cathepsin K, extracellular matrix proteolysis |

| 1428455_at | Col14a1 | BB521934 | ++ | Procollagen, type XIV, alpha 1, extracellular matrix constituent |

| 1438973_x_at | Gja1 | BB043407 | +++ | Gap junction membrane channel protein |

| 1439364_a_at | MMP-2 | BF147716 | ++ | Matrix metalloproteinase 2 |

| 1421618_at | Myo1f | NM_008660 | ++ | Myosin 1f |

++, 2- to 3.9-fold change; +++, 4- to 9.9-fold change; ++++, >10-fold change.

FIG. 3.

The N. brasiliensis (Nb)-altered pulmonary environment is characterized by a sustained increase in CD11c+ AAMs. (A) Real-time RT-PCR was used to measure the transcript levels of the genes encoding the AAM-associated proteins ARG1, YM1, YM2, FIZZ1, CD11c, and CD206 in RNA isolated from whole lungs of uninfected control and day 36 p.i. (Nb+) BALB/c mice. Each bar represents the mean of five mice ± the standard error of the mean. (B) Lung tissue sections were immunostained with anti-YM1, and antibody binding was detected using the chromogen 3,3′-diaminobenzidine and counterstaining with H&E. YM1+ cells are shown with arrowheads. Magnification, ×10. (C) Quantification of YM1-expressing cells was calculated from six contiguous fields for triplicate mice and expressed as the number of cells per unit area. (D) Colocalization of CD11c (Texas red) and YM1 (fluorescein) in alveolar macrophages from N. brasiliensis-infected animals. Nuclei were stained with DAPI, and images were acquired using a SPOT charge-coupled device camera and software. Cells were visualized at a magnification of ×100. (E) FLOW analysis was used to measure the change in the levels of CD11c on the surface of macrophages isolated from whole-lung digests from uninfected and day 36 p.i. mice (see Materials and Methods). (F) FLOW analysis of the changes in MHC class II and CD206 (Mrc1) expression on the surface of CD11c+ cells isolated from the lungs of control and day 36 p.i. mice. (G) FLOW analysis of F4/80 expression on the CD11c+ cells from the lungs of day 36 p.i. mice. The FLOW results are representative of the results from five animals per group.

N. brasiliensis induces a long-term increase in lung AAMs.

The large number of macrophage-associated genes upregulated in day 36 p.i. lungs along with the enhanced expression of the genes encoding YM1, YM2, FIZZ1, and ARG1 predicted an elevation in the number of AAMs. Employing immunohistochemical analysis to identify YM1+ cells, it was confirmed that there was a significant (P < 0.0001) increase in the number of AAMs at 36 days p.i. (Fig. 3C). In uninfected controls, ∼5% of the alveolar macrophages were YM1+, while in day 36 p.i. lungs, >75% were YM1+ (data not shown). The YM1+ cells, which stained positive for CD11c (Fig. 3D) and F4/80+ (Fig. 3G), were distributed evenly throughout the parenchyma of the lung (Fig. 3B). The increase in CD11c mRNA (Table 1; Fig. 3A) correlated with an increase in CD11c protein levels on the surface of lung cells (Fig. 3E). Also consistent with the transcriptional data, N. brasiliensis infection increased the expression of class II MHC and the mannose receptor C type lectin 1 (Mrc1/CD206) (Fig. 3F). The cellular and molecular changes seen at day 36 p.i. show that pulmonary migration by N. brasiliensis induces a persistent population of AAMs in the lung.

STAT6 signaling and the Th1-Th2-Th17 axis.

The persistent production of IL-4 and IL-13 in the pulmonary environment by N. brasiliensis infection (Fig. 2) suggests that sustained STAT6 signaling could play a key role in the maintenance of the altered immunological phenotype of the day 36 p.i. lungs. We compared the expression profile in the lungs from STAT6−/− mice at day 36 p.i. to that in lungs from wild-type (WT) animals to gain an insight into the role of STAT6 signaling in the post-N. brasiliensis lung. In uninfected control STAT6−/− and WT lungs, the expression levels of genes encoding AAM-associated and selected cytokines were equivalent (Fig. 4). Consistent with previous reports, the mechanisms for the induction and maintenance of the AAM phenotype (27, 59) and for expression of eotaxin (31) were dependent on STAT6 signaling. Interestingly, although the expression of ym1 and fizz1 in STAT6−/− lungs was not significantly different from the levels in uninfected control animals, arg1 expression was elevated and essentially identical to the levels induced by N. brasiliensis in WT lungs. The apparent division in the regulation of ym1/fizz1 and arg1 suggests that other signaling pathways are important to the regulation of the full AAM phenotype.

FIG. 4.

N. brasiliensis (Nb)-induced changes in the pulmonary immune environment is mediated partially by STAT6 signaling. RNA was isolated from the lungs of STAT6−/− and WT mice at day 36 post-N. brasiliensis infection, and real-time RT-PCR was used to assess the expression levels of selected cytokines and genes associated with inflammation and alternative activation of macrophages. The results were expressed in relative expression units, and each bar represents the mean threshold cycle value from five animals (± standard error of the mean). Horizontal bars represent the mean values of expression levels obtained from uninfected STAT6−/− and WT lungs. Statistical comparisons were made using a two-tailed Student t test. Significance between STAT6−/− and WT expression is designated by brackets, and significance between expression in infected and uninfected STAT6−/− or WT lungs is designated by asterisks within the bars (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01).

The expression profiles of Th2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-13, and IL-5), Th1 cytokines (IL-12 and IFN-γ), and IL-10 and IL-1β in STAT6−/− and WT lungs at day 36 p.i. were not significantly different (Fig. 4). Importantly, in the absence of STAT6 signaling, the post-N. brasiliensis lungs appeared to mount a strong Th17 response. With the exception of TGF-β (Fig. 4) and IL-23 (data not shown), which were both detectable but not significantly elevated, the expression of genes encoding Th17 effector (IL-17) and regulatory (IL-6 and IL-21) molecules was significantly upregulated in infected STAT6−/− lungs compared to infected WT lungs (Fig. 4). Thus, signaling through STAT6 appears to contribute to the mechanism that regulates expression of Th17 immunity in the post-N. brasiliensis lung.

Histological analysis of lungs from day 36 p.i. STAT6−/− animals revealed levels of alveolar destruction and peribroncular cellular infiltration similar to that observed in day 36 p.i. WT animals (Fig. 1 and data not shown). The cellular infiltrates were composed of lymphocytes, with no evidence of neutrophil accumulation. The STAT6−/− animals had no evidence of bronchial epithelial or goblet cell hyperplasia. Macrophages with the granular morphology were also evident in the day 36 p.i. STAT6−/− lungs, indicating that the development of this phenotype is independent of alternative activation.

Allergen-induced inflammation is reduced in the post-N. brasiliensis lung.

Results of previous studies demonstrated that helminth infection, including infection with N. brasiliensis, resulted in a modulation in the inflammation resulting from a subsequent allergen challenge (65). To determine if the N. brasiliensis-mediated changes in the immunological status of the lungs observed here also correlated with the capacity to modulate responses to a subsequent challenge, day 36 p.i. mice were sensitized and challenged with a clinically relevant allergen, HDM antigen. Lungs were collected at 6, 24, and 72 h after secondary HDM challenge (Fig. 5A) and processed for either histology or RNA extraction. Pulmonary challenge of sensitized BALB/c mice (referred to below as HDM mice) with HDM resulted in a rapid and dramatic increase in eosinophil infiltration (Fig. 5B and N) as previously reported (68). At 6 and 24 h after HDM challenge, the lungs from the HDM-sensitized mice with a history of N. brasiliensis infection (referred to below as N. brasiliensis-HDM mice) had significantly lower levels of eosinophil infiltration in perivascular regions (Fig. 5 B to G and N). At 72 h, although the lungs from the N. brasiliensis-HDM mice maintained lower levels of perivascular eosinophils, the differences between HDM and N. brasiliensis-HDM mice were no longer statistically significantly different (Fig. 5N).

In contrast to the case for eosinophils, at 6 h after allergen challenge, the large airways from the N. brasiliensis-HDM mice had elevated levels of goblet cells compared to the airways from HDM animals (Fig. 5B and E). A comparable increase in goblet cells at 6 h was also seen in the N. brasiliensis-infected animals given PBS (Fig. 5K). This increase in goblet cells was not demonstrable 18 h later (Fig. 5L). Goblet cell numbers increased in both N. brasiliensis-HDM and HDM lungs at 24 h postchallenge to equivalent levels and remained elevated through 72 h (Fig. 5C, D, F, and G). Only the lungs from N. brasiliensis-infected mice contained large pigmented macrophages. Neutrophil infiltration into the lungs was minimal for all of the test and control groups.

Altered gene expression in response to allergen challenge.

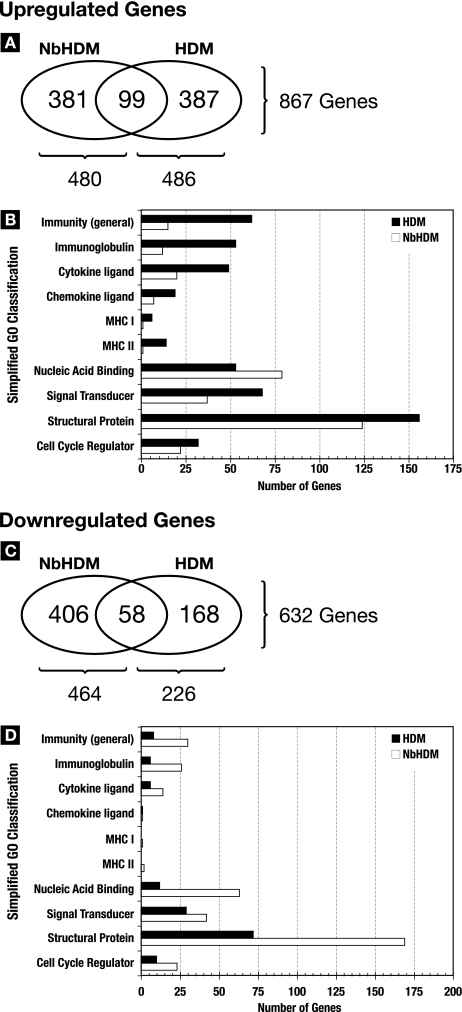

Lungs from mice at 6, 24, and 72 h post-HDM challenge were processed for microarray-based gene expression analysis. When the dynamics of gene expression at all three time points are taken into consideration, the total numbers of genes significantly upregulated in the lungs for at least one time point from HDM and N. brasiliensis-HDM mice were virtually identical (486 versus 480) (Fig. 6A and B). However, examination of the specific genes that were upregulated revealed that only ∼20% (n = 99) were common to both the HDM and the N. brasiliensis-HDM gene lists (Fig. 6A). In contrast, lungs from N. brasiliensis-HDM mice significantly downregulated over twice the number of genes that were downregulated in the lungs of the HDM-only mice (Fig. 6C). While 25% of the 226 genes significantly downregulated in HDM lungs were common to those in N. brasiliensis-HDM lungs, only ∼12% (n = 58) of the 464 genes significantly downregulated in N. brasiliensis-HDM lungs were in common with the HDM expression profile. Thus, N. brasiliensis-induced modulation of the immunological status of the lungs results in a dramatic change in the character of the response to allergen challenge.

FIG. 6.

N. brasiliensis (Nb) modifies global gene responses to allergen challenge. Affymetrix chip-based whole-genome expression analysis was used to analyze the transcriptional responses of lungs at 6, 24, and 72 h post-allergen challenge. Changes above or below twofold were considered significant. Fold changes for the HDM and N. brasiliensis-HDM groups were calculated based on the transcriptional levels measured in age-matched uninfected and N. brasiliensis-infected (day 36 p.i.) control lungs. Expression levels are represented by the means for three mice/group/time point. (A and C) Venn diagrams showing the total numbers of genes upregulated (A) and downregulated (C) at 6, 24, and 72 h post-allergen challenge in the lungs from N. brasiliensis-HDM and HDM mice. (B and D) A simplified gene ontology breakdown of the upregulated genes (B) and downregulated genes (D) in the lungs from N. brasiliensis-HDM and HDM mice. The graphs in panels B and D include only the subset of up- and downregulated genes that were clearly classifiable into the 10 GO terms used.

Utilizing a simplified gene ontology classification system, the genes differentially expressed in HDM- and N. brasiliensis-HDM-challenged lungs were grouped into functional categories (Fig. 6B and D). Approximately 30% of the genes significantly upregulated in the HDM lungs encoded proteins associated with immune activity including genes encoding proteins expressed by granulocytes, B cells, and T cells (Table 2; see Table S2 in the supplemental material). In contrast, only ∼10% of the genes upregulated in the N. brasiliensis-HDM lungs were immunity associated. Conversely, significantly more immunity-associated genes were downregulated in the N. brasiliensis-HDM lungs compared to the HDM lungs (Fig. 6D). This pattern seen for the immunity-associated genes of upregulation in HDM lungs and downregulation in N. brasiliensis-HDM lungs was maintained for the other functional categories except for genes encoding proteins predicted to bind to nucleic acids (Fig. 6B and D).

TABLE 2.

Gene expression in HDM-challenged uninfected and N. brasiliensis-infected mice

| Category and Affymetrix probe no. | Common name | GenBank accession no. | Change in gene expression (fold)a at the indicated time (h) postchallenge

|

Description | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

N. brasiliensis-HDM

|

HDM

|

||||||||

| 6 | 24 | 72 | 6 | 24 | 72 | ||||

| Granulocyte associated | |||||||||

| 1449401_at | C1qγ | NM_007574 | NC | + | NC | + | ++ | ++ | Complement component 1q gamma |

| 1449846_at | Ear2 | AF306665 | − | NC | NC | − | + | ++ | Eosinophil-associated, RNase 2 |

| 1422411_s_at | Ear3 | NM_017388 | −− | NC | NC | − | NC | ++ | Eosinophil-associated, RNase 3 |

| 1417314_at | Cfb | NM_008198 | NC | + | NC | ++ | +++ | ++ | Complement factor B; C3/C5 convertase |

| 1417898_a_at | Gzma | NM_010370 | −− | NC | −− | NC | ++ | NC | Granzyme A; serine-type endopeptidase |

| 1419394_s_at | S100a8 | NM_013650 | NC | −− | −− | +++ | ++ | + | Calgranulin A |

| 1448756_at | S100a9 | NM_009114 | NC | − | −− | +++ | ++ | ++ | Calgranulin B |

| Surface markers and receptors | |||||||||

| 1460218_at | Cd52 | NM_013706 | − | NC | NC | ++ | ++ | +++ | B7; CAMPATH-1 |

| 1449164_at | Cd68 | BC021637 | −− | NC | NC | ++ | +++ | +++ | Macrosialin, Mac marker; late endosomal |

| 1417640_at | Cd79b | NM_008339 | × | NC | − | +++ | × | +++ | B-cell marker; antigen binding transmem receptor |

| 1416111_at | Cd83 | NM_009856 | × | × | × | ++ | × | +++ | DC marker; CD4 T-cell stimulator |

| 1419627_s_at | Clecsf10 | NM_020001 | − | NC | × | ++ | ++ | + | Dectin 2, C-type lectin domain |

| 1425407_s_at | Clecsf6 | BC006623 | × | × | × | × | +++ | ++ | Immunoreceptor with ITIM |

| 1419872_at | Csf1r | AI323359 | NC | NC | NC | NC | ++ | ++ | CD115; macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor |

| 1455660_at | Csf2rβ1 | BB769628 | NC | NC | NC | ++ | ++ | ++ | Low-affinity granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor (IL-3R) |

| 1418806_at | Csf3r | NM_007782 | × | × | × | +++ | ++ | × | CD114; granulocyte colony-stimulating factor receptor |

| 1418340_at | Fcer1γ | NM_010185 | × | NC | NC | + | ++ | ++ | High-affinity IgE receptor |

| 1426808_at | Lgals3 | X16834 | NC | + | NC | ++ | ++ | ++ | Mac-2; IgE binding surface lectin |

| 1450430_at | Mrc1 | NM_008625 | NC | + | NC | + | ++ | ++ | Mannose binding receptor 1 |

| Cytokine and chemokine | |||||||||

| 1418126_at | CCL5 | NM_013653 | × | NC | × | × | ++ | ++ | RANTES; cytokine, chemokine activity |

| 1419135_at | Ltβ | NM_008518 | NC | NC | NC | ++ | ++ | ++ | Lymphotoxin B |

| 1419699_at | Scgb3a1 | NM_054037 | −− | NC | NC | ++ | ++ | ++ | Secretoglobin; cytokine activity |

| 1455899_x_at | Socs3 | BB241535 | NC | NC | NC | +++ | + | NC | Suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 |

| Immunoglobulin related | |||||||||

| 1425324_x_at | Igh-4 | AF466769 | −− | − | NC | × | × | ++++ | IgG1 heavy chain |

| 1427351_s_at | Igh-6 | BB226392 | NC | − | NC | +++ | ++ | ++++ | IgM heavy chain |

| 1424305_at | Igj | BC006026 | NC | −− | NC | NC | × | +++ | Immunoglobulin joining chain |

| 1430523_s_at | Igλ-V1 | AK008145 | −− | × | − | × | × | +++ | Immunoglobulin lambda chain, variable 1 |

| 1427994_at | Pigr3 | BM230330 | NC | + | NC | ++ | ++ | + | CD300lf; polymeric immunoglobulin receptor 3 |

| T-cell related | |||||||||

| 1449254_at | Spp1 | NM_009263 | −− | NC | NC | ++ | ++ | ++ | Secreted phosphoprotein 1, T-cell activator |

| 1427102_at | Slfn4 | AF099975 | × | × | × | ++++ | +++ | × | Schlafen 4; thymocyte regulatory gene |

| 1426113_x_at | Tcrα | U07662 | − | × | × | × | × | ++ | T-cell receptor alpha chain |

| 1426772_x_at | Tcrβ-J | M11456 | × | × | × | × | × | ++ | T-cell receptor beta, joining region |

| 1452205_x_at | Tcrβ-V13 | X67128 | × | NC | NC | × | × | ++ | T-cell receptor beta, variable 13 |

| 1423135_at | Thy1 | AV028402 | × | × | × | × | × | ++ | CD90, thymus cell antigen 1, theta |

++++, >10-fold change; +++, 4- to 9.9-fold change; ++, 2- to 3.9-fold change; +, 1.5- to 1.9-fold change; NC, no change (0.6- to 1.4-fold change); −, 0.5- to 0.66-fold change; −−, 0.25- to 0.49-fold change; ×, fluorescence signal of <150.

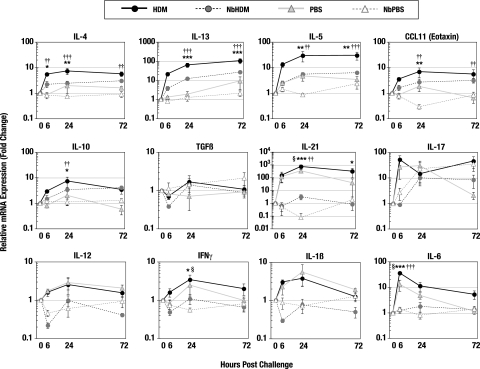

A real-time RT-PCR approach was used to validate the relative increases in the transcription of genes encoding cytokines and chemokines (Fig. 7) identified in the array results from HDM challenge and control animals. At 6 and 24 h post-allergen challenge, the fold increases in the transcription of the genes encoding the Th2 cytokines IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 and the chemokine CCL11 (eotaxin) were significantly higher in HDM lungs than in the lungs from N. brasiliensis-HDM mice. The differences in the expression of these cytokines in the HDM and N. brasiliensis-HDM lungs were maintained through 72 h postchallenge, but the differences were no longer statistically significant. N. brasiliensis-HDM mice significantly downregulated the expression of IL-12, IFN-γ, and IL-1β (Fig. 7), whereas HDM mice showed two- to fourfold increases in these Th1 proinflammatory molecules. IL-10 expression was modestly elevated in the lungs of HDM animals compared to the N. brasiliensis-HDM animals. There was no significant change in the expression levels of TGF-β in any of the test or control groups. IL-21 transcription was significantly increased in the lungs from both uninfected and N. brasiliensis-infected animals at all time points after allergen challenge. In contrast to the nearly undetectable levels of IL-17 expression in the lungs of the N. brasiliensis-HDM group at 6 h postchallenge, there was a rapid, >50-fold induction of IL-17 transcription in the lungs of the HDM mice (Fig. 7). By 24 h post-HDM challenge, the IL-17 expression levels for both groups were essentially equal.

FIG. 7.

N. brasiliensis (Nb) alters immune responses to allergen challenge and reduces airway resistance. Real-time RT-PCR was used to measure gene expression in the whole lungs removed from control or N. brasiliensis-infected mice at 6, 24, or 72 h postchallenge with either HDM or PBS. Fold change calculations for the N. brasiliensis-HDM and N. brasiliensis-PBS groups were made based on the gene expression levels of N. brasiliensis-infected lungs at day 36 p.i. Fold change calculations for the HDM and PBS groups were based on expression levels of age-matched uninfected controls. Points represent the mean expression levels for five mice/group/time point. Error bars represent the standard errors of the means. Statistical comparisons were generated by a two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni posttesting. Comparison of HDM versus N. brasiliensis-HDM: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Comparison of HDM versus PBS: †, P < 0.05; ††, P < 0.01; †††, P < 0.001. Comparison of PBS versus N. brasiliensis-PBS: §, P < 0.05.

Also of interest are the responses in the uninfected and previously N. brasiliensis-infected groups challenged with PBS. While the control PBS challenges caused no change in transcription levels of a majority of the cytokines and chemokines tested, the transcription of genes encoding IL-17, IL-21, and IL-6 was significantly increased at 6 and 24 h after administering PBS (Fig. 7). For the most part, this increase in gene transcription was observed only in the uninfected mice. Those mice previously infected with N. brasiliensis demonstrated no significant increase in transcription of these cytokines. This trend for a rapid upregulation of Th17-associated cytokines in the lungs of uninfected animals suggests that a Th17 response may be an important component of the immediate reaction to lung damage or antigen exposure. An antecedent N. brasiliensis infection appears to significantly modulate the immediate Th17 response.

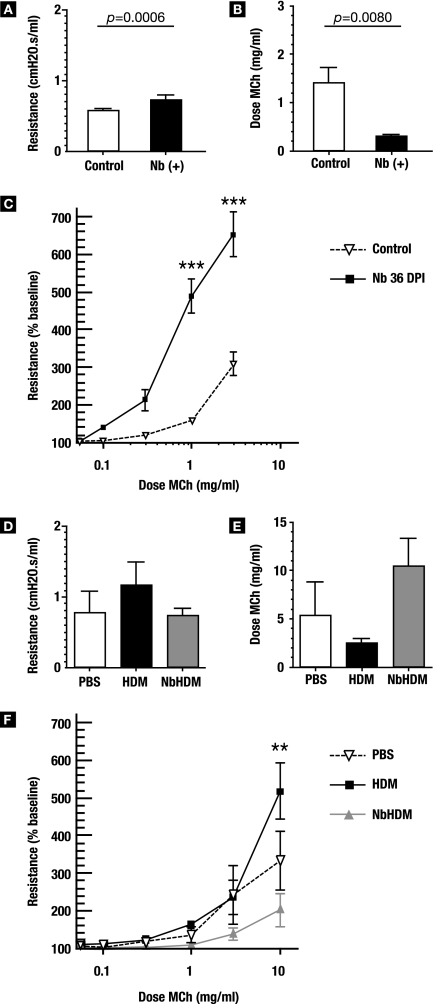

N. brasiliensis alters airway responsiveness.

In vivo assessment of the differences in pulmonary function between infected and uninfected lungs was performed using anesthetized, paralyzed, and intubated mice on a ventilator. At 36 days p.i., N. brasiliensis-infected animals showed a statistically significantly higher baseline resistance (P = 0.0006) (Fig. 8A), and the amount of methacholine necessary to double the baseline resistance in N. brasiliensis-infected mice was ∼4-fold lower than that required for the airways of uninfected control mice (P = 0.008) (Fig. 8B). Correspondingly, dose responses to methacholine were significantly higher in parasitized lungs (Fig. 8C). Thus, N. brasiliensis infection resulted in a significant increase in airway hyperresponsiveness.

FIG. 8.

N. brasiliensis (Nb) infection alters airway responsiveness. (A to C) Groups of six day 36 p.i. and age-matched control mice were intubated and placed on a ventilator to assess their pulmonary function in vivo. (A) Baseline resistance was calculated and expressed as cm H2O·s/ml. (B) Methacholine (MCh) was then added for 10 seconds by nebulizer, and corresponding airway resistance was measured. The amount of MCh required to double the baseline resistance is shown. (C) Dose responses to MCh were normalized to a baseline resistance of 100. (D to E) N. brasiliensis-infected and control mice were sensitized and challenged with HDM as outlined in Materials and Methods. At 24 h after the second challenge, mice were sedated, intubated, and placed on a ventilator to test their responsiveness to MCh. (D) Baseline resistance in the lung before MCh challenge, expressed as cm H2O·s/ml. (E) Dose of MCh required to double the baseline resistance in the lungs. (F) Dose response to MCh challenge. Error bars represent standard errors of the means. Two-way ANOVA analysis followed by Bonferroni posttesting showed that there was a significant difference (**, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

Paradoxically, N. brasiliensis infection resulted in a reduction in airway responsiveness after challenge with an allergen (Fig. 8D to F). Baseline resistance (no methacholine) in the lungs of N. brasiliensis-HDM mice was essentially identical to that in controls, whereas HDM mice had an elevated baseline resistance (Fig. 8D). The mean dose of methacholine necessary for doubling airway resistance in HDM mice was about half that of control animals and only ∼25% the dose needed for N. brasiliensis-HDM mice (Fig. 8E). While N. brasiliensis-HDM mice clearly maintained lower airway resistance to methacholine throughout the dose-response window compared to the HDM and control mice (Fig. 8F), the differences were statistically different only at the 10-mg/ml dose of methacholine. Thus, although N. brasiliensis infection resulted in heightened baseline airway reactivity, there was a dramatic reduction in the level of airway responsiveness in N. brasiliensis-infected animals after a secondary challenge with HDM.

DISCUSSION

The N. brasiliensis-induced alterations at 36 days p.i. included an increase in the constitutive transcription of both Th2 (IL-4, IL-13, and IL-5) and Th1 (IFN-γ and IL-12) cytokines but not that of the traditional regulatory cytokines IL-10 and TGF-β. The idea that this alteration in cytokine levels might be a permanent feature in the lungs is supported by the fact that it is still detectable at 100 days p.i. (data not shown). The exact significance of this altered balance between Th2 and Th1 cytokines in the lungs is not clear. Aspects of the persistent changes in cytokine production appear to be an extension of the strong Th2-biased innate and early adaptive responses to the presence of the larvae in the lungs (43). The constitutive elevation of Th1 cytokine expression might be in response to the presence of elevated levels of Th2 cytokines and reflect efforts to control the extent of the Th2 reactivity or other pathogenic mechanisms in the lung.

The results from infections in STAT6−/− animals suggest that there is a mechanistic connection between persistent IL-4 and IL-13 expression and at least some aspects of the altered immunological environment in the day 36 p.i. lung. In the absence of STAT6 signaling, there was a significant decrease in the transcription of ym1 and fizz1 (Fig. 4), signature molecules of alterative macrophage activation. The development of the alternatively activated phenotype has been shown previously to be dependent on STAT6 (27, 59), and the genes encoding YM1 and FIZZ1 have STAT6 response elements in their promoter regions that combine with other transcription factors to promote efficient expression (25, 53, 62, 69). Although the results of studies indicate that arg1 transcription is also controlled by a STAT6 response element (15, 69), arg1 expression was significantly elevated in the day 36 p.i. STAT6−/− lungs to a level comparable to that measured in the day 36 p.i. WT lungs. The results presented here suggest that there is at least one STAT6-independent pathway capable of regulating arg1 transcription in the lungs. The presence of IL-4 and IL-13 in STAT6-deficient animals still allows for the possibility of signaling through the IL-4 receptor (IL-4R) utilizing the STAT6-independent insulin receptor substrate 1 and 2 pathway (37). It is possible that insulin receptor substrate 1 and 2 signaling alone or in conjunction with other dominant signals in the infectious environment is sufficient to induce increased arg-1 expression in STAT6-deficient animals.

In the absence of STAT6 signaling, the post-N. brasiliensis lung had a dramatic increase in the transcription of IL-6, IL-21, and IL-17, an expression pattern consistent with the development of a Th17 response (23, 38). Th17 differentiation from naïve precursors is initiated by IL-6, TGF-β and IL-21 and reinforced by IL-23 (38, 57), and transcripts for all four of these cytokines were present in the day 36 p.i. STAT6−/− lungs (Fig. 4 and data not shown). In the lungs from WT animals, only low levels of IL-17 could be detected (Fig. 2). This suppression of Th17 development in WT mice was presumably due to the elevated production of IL-4 and IFN-γ (Fig. 2 and 4). The presence of both IL-4 and IFN-γ is required to suppress the development of Th17 cells from naïve precursor cells and may represent a key mechanism by which N. brasiliensis infection modulates allergic responsiveness in the pulmonary environment. (41). The development of a Th17 response in the N. brasiliensis-infected STAT6−/− lungs despite elevated IFN-γ transcription is likely due to the inability to send the necessary second, IL-4-mediated signal to T cells. Thus, it is possible that the functional significance of the increase in both Th1 and Th2 cytokines in the post-N. brasiliensis lung is to regulate the level of Th17 development and thus minimize tissue damage during subsequent pulmonary responses.

IL-17 transcription was robustly induced by challenge with HDM allergen. In model systems, IL-17 is strongly associated with tissue damage in the brain, heart, synovium, skin, and intestines (reviewed in reference 51). The role that IL-17 plays in the lungs during allergic responses is still not clear. While constitutive overexpression of IL-17 in lung endothelial cells result in a peribronchiolar cellular infiltration and mucus production (41), IL-17 administered during the chronic phase of an allergic response results in a reduction in eosinophilia and a drop in the reactivity of the large airways (46). The over-50-fold induction of IL-17 at 6 h post-HDM challenge suggests that IL-17 can also play a significant role during the immediate/early response after allergen challenge. However, it is still unclear whether the HDM-induced Th17 response contributes to the pathology or if it is part of the mechanism to control the level of damage. This IL-17 induction appears to occur independent of discernible increases in IL-23 transcription (data not shown). Th17 cells induced in the absence of IL-23 have been shown to express IL-10 and to restrain cell-mediated pathology in the central nervous system (33). It is possible that the IL-17-producing cells were also the source of the elevation in IL-10 transcription in the HDM-challenged animals (Fig. 7). IL-10/IL-17-expressing cells could also account for the limited pathology observed in day 36 p.i. STAT6−/− lungs.

The specific cellular source(s) of the transcripts encoding Th2 and Th1 cytokines at day 36 p.i. remains to be defined. The results for day 36 p.i. lungs from the bicistronic IL-4 reporter (4get [35]) mice indicate that the IL-4 was produced primarily by T cells with some contribution from granulocytic cells (data not shown). Infection with N. brasiliensis is known to recruit IL-4- and IL-13-producing cells into the lungs, including eosinophils, basophils, and CD4+ Th2 cells (13, 32, 34, 58), and these cells are the most logical sources of the elevated transcription of Th2 cytokine genes. The demonstrable elevation in the constitutive transcription of both eotaxin and IL-5 at day 36 p.i. compared to that in uninfected, age-matched controls suggested that eosinophils might be a major source of IL-4 and IL-13. However, histological analysis of day 36 p.i. lungs indicated no obvious increase in the number of eosinophils. It has been reported previously that several days after N. brasiliensis larvae exit the lungs there is significant population of IL-4-producing, partially degranulated eosinophils (49). It is possible that these partially degranulated cells persist through to day 36 p.i. but were not readily identifiable in the histological analysis.

While it has been demonstrated that transcription of Th2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-13 can be uncoupled from protein production (13), for Th1 cytokines, including IFN-γ (32), transcription appears to be a more reliable surrogate of protein synthesis. Thus, it is possible that the increases in Th2 cytokine transcription measured in the post-N. brasiliensis lungs do not reflect a commensurate increase in the production of the active cytokine. Attempts to measure differences in the protein levels of the Th1 and Th2 cytokines in lung homogenates and in bronchial alveolar lavage fluids from control and day 36 p.i. animals proved to be problematic. The maintenance of the AAM phenotype, a phenotype that is dependent on Th2 cytokines (14), suggests that biologically active IL-4 and/or IL-13 is being produced. It has been shown that mature mast cells, eosinophils, and basophils are programmed for IL-4 and IL-13 transcription early in development, but these cells do not produce protein until they are properly activated (13). It is possible that the elevated transcription described here represents, in part, a heightened capacity for the lung to rapidly respond to antigen challenge.

N. brasiliensis infection resulted in a significant and persistent upregulation of the gene encoding IL-21 (in the absence of IL-17 and IL-23) in the lungs at day 36 p.i. IL-21 is a member of the IL-2/IL-4/IL-15 family of cytokines (16), which bind to a class 1 cytokine receptor that utilizes the common γ chain for functional signaling (40). IL-21 is produced mainly by antigen-activated CD4+ T cells and the IL-21R; while found on a broad spectrum of cell types, is preferentially expressed on T cells, B cells, NK cells, keratinocytes, and cells of the myeloid lineage (reviewed in reference 24). Although IL-21 is known to contribute to the induction of Th17 responses, the specific role that IL-21 plays in the post-N. brasiliensis lung remains unclear. However, IL-21 has been reported to have several functions that are independent of Th17 development, and these suggest that it might contribute to the regulation of allergic responsivenss in the post-N. brasiliensis lung. IL-21 has been shown to modulate the levels of IgE produced by B cells (54) and also appears to have a direct effect on the development of AAMs. There was a marked reduction in the AAM-associated genes encoding YM1, FIZZ1, and acidic mammalian chitinase in the lungs and lung-associated lymph nodes in IL-21R−/− mice (42). Mechanistically, it appears that signaling through the IL-21R is required to upregulate IL-4Rα and IL-13Rα1 so that macrophages can efficiently take on the AAM phenotype. The constitutive upregulation of IL-4, IL-13, and IL-21 in post-N. brasiliensis lungs could explain the persistently elevated levels of AAMs. The cellular source of IL-21 in the post-N. brasiliensis lung is yet to be defined.

At day 36 p.i., approximately 75% of the CD11c+, F4/80+ alveolar macrophages displayed an alternatively activated phenotype characterized by transcription of ym1, ym2, fizz1, and arg1 and increased expression of mrc1 and the genes encoding class II MHC. A previous report documented a nearly total conversion of the alveolar macrophage population to the alternatively activated phenotype within hours of the larvae entering the lungs, which was maintained through day 12 p.i. (43). The demonstration that the AAM phenotype remains dominant at day 36 p.i. and that it is still readily detectable through to day 100 p.i. (reference 30 and data not shown) suggests that this phenotypic skewing is a fixed consequence of N. brasiliensis infection.

It is likely that the AAMs resulting from N. brasiliensis infection contribute to the regulatory environment in the lungs. AAMs outside the lung have been assigned roles in debris scavenging, tissue remodeling during wound healing, and the promotion of Th2 immune responses (14, 36, 50). The results of several studies indicate that AAMs play both direct and indirect roles in the pathogenesis of infectious diseases. The presence of AAMs in the lungs of Cryptococcus neoformans-infected mice was accompanied by a switch from a chronic to a progressive pulmonary fungal infection (4). In the Leishmania major-mouse model of cutaneous leishmanisis, where Th1 responses are required for effective immunity, AAMs contribute to parasite persistence and disease progression (19). The functional significance of the AAMs induced during schistosomiasis is complex. On one hand, the development of AAMs appears to be critical to dampen the destructive potential of the acute egg-induced inflammation that leads to oxidative damage to liver tissue (17, 18). On the other hand, the Arg1 produced by the granuloma-associated AAMs mediates the fibrosis that is characteristic of the chronic pathology in schistosomiasis (18, 42, 44). AAMs induced in the peritoneal cavity by the filarial nematode Brugia malayi are capable of inhibiting T cell proliferation through a contact-mediated mechanism (27). Another filarial species, Litomosoides sigmodontis, induced F4/80+ AAMs in the pericardial cavity that potently inhibit antigen-specific CD4+ T-cell proliferation (55). AAMs have been shown to function as key effector cells in the protective memory response to the elimination of Heligmosomoides polygyrus from the gut (2). Collectively, the data strongly suggests that AAMs play an important role in regulating Th2-biased inflammation.

Recently, Loke and colleagues showed that mechanical damage was capable of inducing alternative activation of macrophages without the presence of an infectious agent (26). The level of larval challenge used in this study (500 L3s) results in obvious mechanical damage to the lungs (30, 43). Pulmonary damage inflicted by helminth migration through the parenchyma is thus likely to be a contributor to the generation and maintenance of AAMs in the lung.

A number of important helminth parasites of humans have incorporated a short-term residence in the lungs as an obligate phase of their life cycle. While the significance of the lung phase to the developmental biology of the parasite is not clear, this short-term exposure has a long-lasting impact on the immunobiology of the lung. Given this direct contact, it is perhaps not surprising that helminths induce cellular and/or molecular changes that include regulatory responses in the lungs. Interestingly, the strictly enteric helminth H. polygyrus, which has no apparent direct impact on the lung (22), also induces regulatory responses that are capable of modulating allergen-induced pulmonary inflammation (64). A major mediator of this downregulation of pulmonary inflammation was shown to be H. polygyrus-induced CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. The CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ phenotype and its ability to work in an organ that presumably has not seen H. polygyrus antigen suggests that the regulatory T cells induced by H. polygyrus are natural Tregs that recognize self antigen (6). If H. polygyrus does indeed have the ability to induce a population of natural Tregs (possibly a population that is focused on mucosa-associated self antigens), this would provide a mechanism for bridging the gap between the gut and the lung. An important common element in the cellular responses induced by both H. polygyrus and N. brasiliensis is the strong induction of AAMs (2, 43). It is possible that AAMs have a direct role in the induction and maintenance of a Treg-mediated regulatory environment. Given the proven capacity of AAM as effector cells and homeostatic regulators in both mucosal and nonmucosal sites, the substantial and persistent increase of AAMs in the lungs might represent a heretofore-unappreciated cellular component in the overall mechanism that modulates inflammation in the post-N. brasiliensis lung.

The infection-mediated elevation in airway responsiveness to methacholine challenge reported here (Fig. 8) was also observed by Marsland and colleagues (30). This N. brasiliensis-induced chronic hyperresponsiveness was shown to persist beyond 100 days p.i. (30). In stark contrast, the reactivity of the large airways from N. brasiliensis-HDM animals was significantly below that of the controls (Fig. 8). The mechanistic basis for this dramatic transition in the level of airway reactivity in N. brasiliensis-infected animals has yet to be fully defined. It is possible that the 48-hour window between the first intranasal HDM antigen exposure and the methacholine challenge provided a sufficient amount of time to activate the N. brasiliensis-induced regulatory mechanisms that control airway reactivity. It is likely that the mechanisms that function to rapidly repress the reactivity of the large airways in the post-N. brasiliensis lung are reflected in the distinctive expression profile observed post-allergen challenge.

A number of studies have used animal models to address the mechanistic issues that underlie the inverse relationship between the epidemiologies of helminth infection and allergic disease in human populations (5, 61, 64, 65) and the immunological observations that preexisting helminth infection alters the magnitude and character of the immune responses to subsequent pathogen or antigen challenges (7, 12, 45). Results from studies where infection with the nematode N. brasiliensis, H. polygyrus, or Strongyloides stercoralis was superimposed upon the ovalbumin allergy model demonstrated that reductions in the responses to allergen challenge were characterized by downregulation of eotaxin production, a commensurate decrease in eosinophil infiltration, and a decrease in lung-associated IgE levels (60, 64, 65). In addition to confirming this helminth-induced decrement in responsiveness to subsequent antigen challenge, the work presented here defines the persistent molecular and cellular alterations that accompany this reduction in response in the post-N. brasiliensis lung. These long-term pulmonary changes provide an immunological context to understand the mechanisms involved in the modulated immune responses observed post-helminth infection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Anne Jedlicka and Meg Mintz (Johns Hopkins Malaria Research Institute Genearray Core Facility) for assistance in the microarray experiments. For their assistance in the pulmonary function testing, we thank Andrea Keane-Myers (NIH, Rockville, MD) and Wayne Mitzner and Jon Fallica (JH BSPH, Baltimore, MD).

This work was supported by grants from NIH NHLBI (U01 HL66623) and NIH training grant T32AI007417.

Editor: W. A. Petri, Jr.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 27 May 2008.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://iai.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen, J. E., and R. M. Maizels. 1996. Immunology of human helminth infection. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 1093-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anthony, R. M., J. F. Urban, Jr., F. Alem, H. A. Hamed, C. T. Rozo, J. L. Boucher, N. Van Rooijen, and W. C. Gause. 2006. Memory T(H)2 cells induce alternatively activated macrophages to mediate protection against nematode parasites. Nat. Med. 12955-960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Araujo, M. I., A. A. Lopes, M. Medeiros, A. A. Cruz, L. Sousa-Atta, D. Sole, and E. M. Carvalho. 2000. Inverse association between skin response to aeroallergens and Schistosoma mansoni infection. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 123145-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arora, S., Y. Hernandez, J. R. Erb-Downward, R. A. McDonald, G. B. Toews, and G. B. Huffnagle. 2005. Role of IFN-gamma in regulating T2 immunity and the development of alternatively activated macrophages during allergic bronchopulmonary mycosis. J. Immunol. 1746346-6356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bashir, M. E., P. Andersen, I. J. Fuss, H. N. Shi, and C. Nagler-Anderson. 2002. An enteric helminth infection protects against an allergic response to dietary antigen. J. Immunol. 1693284-3292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belkaid, Y., and B. T. Rouse. 2005. Natural regulatory T cells in infectious disease. Nat. Immunol. 6353-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brutus, L., L. Watier, V. Briand, V. Hanitrasoamampionona, H. Razanatsoarilala, and M. Cot. 2006. Parasitic co-infections: does Ascaris lumbricoides protect against Plasmodium falciparum infection? Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 75194-198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Card, J. W., M. A. Carey, J. A. Bradbury, L. M. DeGraff, D. L. Morgan, M. P. Moorman, G. P. Flake, and D. C. Zeldin. 2006. Gender differences in murine airway responsiveness and lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation. J. Immunol. 177621-630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper, P. J., M. E. Chico, L. C. Rodrigues, M. Ordonez, D. Strachan, G. E. Griffin, and T. B. Nutman. 2003. Reduced risk of atopy among school-age children infected with geohelminth parasites in a rural area of the tropics. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 111995-1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dagoye, D., Z. Bekele, K. Woldemichael, H. Nida, M. Yimam, A. Hall, A. J. Venn, J. R. Britton, R. Hubbard, and S. A. Lewis. 2003. Wheezing, allergy, and parasite infection in children in urban and rural Ethiopia. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1671369-1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Silva, N. R., S. Brooker, P. J. Hotez, A. Montresor, D. Engels, and L. Savioli. 2003. Soil-transmitted helminth infections: updating the global picture. Trends Parasitol. 19547-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elias, D., H. Akuffo, and S. Britton. 2006. Helminthes could influence the outcome of vaccines against TB in the tropics. Parasite Immunol. 28507-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gessner, A., K. Mohrs, and M. Mohrs. 2005. Mast cells, basophils, and eosinophils acquire constitutive IL-4 and IL-13 transcripts during lineage differentiation that are sufficient for rapid cytokine production. J. Immunol. 1741063-1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gordon, S. 2003. Alternative activation of macrophages. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 323-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gray, M. J., M. Poljakovic, D. Kepka-Lenhart, and S. M. Morris, Jr. 2005. Induction of arginase I transcription by IL-4 requires a composite DNA response element for STAT6 and C/EBPbeta. Gene 35398-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Habib, T., A. Nelson, and K. Kaushansky. 2003. IL-21: a novel IL-2-family lymphokine that modulates B, T, and natural killer cell responses. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1121033-1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herbert, D. R., C. Holscher, M. Mohrs, B. Arendse, A. Schwegmann, M. Radwanska, M. Leeto, R. Kirsch, P. Hall, H. Mossmann, B. Claussen, I. Forster, and F. Brombacher. 2004. Alternative macrophage activation is essential for survival during schistosomiasis and downmodulates T helper 1 responses and immunopathology. Immunity 20623-635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hesse, M., M. Modolell, A. C. La Flamme, M. Schito, J. M. Fuentes, A. W. Cheever, E. J. Pearce, and T. A. Wynn. 2001. Differential regulation of nitric oxide synthase-2 and arginase-1 by type 1/type 2 cytokines in vivo: granulomatous pathology is shaped by the pattern of l-arginine metabolism. J. Immunol. 1676533-6544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holscher, C., B. Arendse, A. Schwegmann, E. Myburgh, and F. Brombacher. 2006. Impairment of alternative macrophage activation delays cutaneous leishmaniasis in nonhealing BALB/c mice. J. Immunol. 1761115-1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Irizarry, R. A., D. Warren, F. Spencer, I. F. Kim, S. Biswal, B. C. Frank, E. Gabrielson, J. G. Garcia, J. Geoghegan, G. Germino, C. Griffin, S. C. Hilmer, E. Hoffman, A. E. Jedlicka, E. Kawasaki, F. Martinez-Murillo, L. Morsberger, H. Lee, D. Petersen, J. Quackenbush, A. Scott, M. Wilson, Y. Yang, S. Q. Ye, and W. Yu. 2005. Multiple-laboratory comparison of microarray platforms. Nat. Methods 2345-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishizaka, T., J. F. Urban, Jr., and K. Ishizaka. 1976. IgE formation in the rat following infection with Nippostrongylus brasiliensis. I. Proliferation and differentiation of IgE-bearing cells. Cell. Immunol. 22248-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kitagaki, K., T. R. Businga, D. Racila, D. E. Elliott, J. V. Weinstock, and J. N. Kline. 2006. Intestinal helminths protect in a murine model of asthma. J. Immunol. 1771628-1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Korn, T., E. Bettelli, W. Gao, A. Awasthi, A. Jager, T. B. Strom, M. Oukka, and V. K. Kuchroo. 2007. IL-21 initiates an alternative pathway to induce proinflammatory T(H)17 cells. Nature 448484-487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leonard, W. J., and R. Spolski. 2005. Interleukin-21: a modulator of lymphoid proliferation, apoptosis and differentiation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5688-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu, T., H. Jin, M. Ullenbruch, B. Hu, N. Hashimoto, B. Moore, A. McKenzie, N. W. Lukacs, and S. H. Phan. 2004. Regulation of found in inflammatory zone 1 expression in bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis: role of IL-4/IL-13 and mediation via STAT-6. J. Immunol. 1733425-3431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loke, P., I. Gallagher, M. G. Nair, X. Zang, F. Brombacher, M. Mohrs, J. P. Allison, and J. E. Allen. 2007. Alternative activation is an innate response to injury that requires CD4+ T cells to be sustained during chronic infection. J. Immunol. 1793926-3936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loke, P., A. S. MacDonald, A. Robb, R. M. Maizels, and J. E. Allen. 2000. Alternatively activated macrophages induced by nematode infection inhibit proliferation via cell-to-cell contact. Eur. J. Immunol. 302669-2678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luna, L. G. (ed.). 1968. Manual of histologic staining methods of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, 3rd ed. Blakiston Division, New York, NY.

- 29.MacDonald, A. S., M. I. Araujo, and E. J. Pearce. 2002. Immunology of parasitic helminth infections. Infect. Immun. 70427-433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marsland, B. J., M. Kurrer, R. Reissmann, N. L. Harris, and M. Kopf. 2008. Nippostrongylus brasiliensis infection leads to the development of emphysema associated with the induction of alternatively activated macrophages. Eur. J. Immunol. 38479-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsukura, S., C. Stellato, S. N. Georas, V. Casolaro, J. R. Plitt, K. Miura, S. Kurosawa, U. Schindler, and R. P. Schleimer. 2001. Interleukin-13 upregulates eotaxin expression in airway epithelial cells by a STAT6-dependent mechanism. Am. J. Respir. Cell. Mol. Biol. 24755-761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mayer, K. D., K. Mohrs, S. R. Crowe, L. L. Johnson, P. Rhyne, D. L. Woodland, and M. Mohrs. 2005. The functional heterogeneity of type 1 effector T cells in response to infection is related to the potential for IFN-gamma production. J. Immunol. 1747732-7739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGeachy, M. J., K. S. Bak-Jensen, Y. Chen, C. M. Tato, W. Blumenschein, T. McClanahan, and D. J. Cua. 2007. TGF-beta and IL-6 drive the production of IL-17 and IL-10 by T cells and restrain T(H)-17 cell-mediated pathology. Nat. Immunol. 81390-1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Min, B., M. Prout, J. Hu-Li, J. Zhu, D. Jankovic, E. S. Morgan, J. F. Urban, Jr., A. M. Dvorak, F. D. Finkelman, G. LeGros, and W. E. Paul. 2004. Basophils produce IL-4 and accumulate in tissues after infection with a Th2-inducing parasite. J. Exp. Med. 200507-517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mohrs, M., K. Shinkai, K. Mohrs, and R. M. Locksley. 2001. Analysis of type 2 immunity in vivo with a bicistronic IL-4 reporter. Immunity 15303-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mosser, D. M. 2003. The many faces of macrophage activation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 73209-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nelms, K., A. D. Keegan, J. Zamorano, J. J. Ryan, and W. E. Paul. 1999. The IL-4 receptor: signaling mechanisms and biologic functions. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 17701-738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nurieva, R., X. O. Yang, G. Martinez, Y. Zhang, A. D. Panopoulos, L. Ma, K. Schluns, Q. Tian, S. S. Watowich, A. M. Jetten, and C. Dong. 2007. Essential autocrine regulation by IL-21 in the generation of inflammatory T cells. Nature 448480-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nyan, O. A., G. E. Walraven, W. A. Banya, P. Milligan, M. Van Der Sande, S. M. Ceesay, G. Del Prete, and K. P. McAdam. 2001. Atopy, intestinal helminth infection and total serum IgE in rural and urban adult Gambian communities. Clin. Exp. Allergy 311672-1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ozaki, K., K. Kikly, D. Michalovich, P. R. Young, and W. J. Leonard. 2000. Cloning of a type I cytokine receptor most related to the IL-2 receptor beta chain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9711439-11444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park, H., Z. Li, X. O. Yang, S. H. Chang, R. Nurieva, Y. H. Wang, Y. Wang, L. Hood, Z. Zhu, Q. Tian, and C. Dong. 2005. A distinct lineage of CD4 T cells regulates tissue inflammation by producing interleukin 17. Nat. Immunol. 61133-1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pesce, J., M. Kaviratne, T. R. Ramalingam, R. W. Thompson, J. F. Urban, Jr., A. W. Cheever, D. A. Young, M. Collins, M. J. Grusby, and T. A. Wynn. 2006. The IL-21 receptor augments Th2 effector function and alternative macrophage activation. J. Clin. Investig. 1162044-2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reece, J. J., M. C. Siracusa, and A. L. Scott. 2006. Innate immune responses to lung-stage helminth infection induce alternatively activated alveolar macrophages. Infect. Immun. 744970-4981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reiman, R. M., R. W. Thompson, C. G. Feng, D. Hari, R. Knight, A. W. Cheever, H. F. Rosenberg, and T. A. Wynn. 2006. Interleukin-5 (IL-5) augments the progression of liver fibrosis by regulating IL-13 activity. Infect. Immun. 741471-1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Resende Co, T., C. S. Hirsch, Z. Toossi, R. Dietze, and R. Ribeiro-Rodrigues. 2007. Intestinal helminth co-infection has a negative impact on both anti-Mycobacterium tuberculosis immunity and clinical response to tuberculosis therapy. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 14745-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]