Abstract

Hydroquinone 1,2-dioxygenase (HQDO), an enzyme involved in the catabolism of 4-hydroxyacetophenone in Pseudomonas fluorescens ACB, was purified to apparent homogeneity. Ligandation with 4-hydroxybenzoate prevented the enzyme from irreversible inactivation. HQDO was activated by iron(II) ions and catalyzed the ring fission of a wide range of hydroquinones to the corresponding 4-hydroxymuconic semialdehydes. HQDO was inactivated by 2,2′-dipyridyl, o-phenanthroline, and hydrogen peroxide and inhibited by phenolic compounds. The inhibition with 4-hydroxybenzoate (Ki = 14 μM) was competitive with hydroquinone. Online size-exclusion chromatography-mass spectrometry revealed that HQDO is an α2β2 heterotetramer of 112.4 kDa, which is composed of an α-subunit of 17.8 kDa and a β-subunit of 38.3 kDa. Each β-subunit binds one molecule of 4-hydroxybenzoate and one iron(II) ion. N-terminal sequencing and peptide mapping and sequencing based on matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization—two-stage time of flight analysis established that the HQDO subunits are encoded by neighboring open reading frames (hapC and hapD) of a gene cluster, implicated to be involved in 4-hydroxyacetophenone degradation. HQDO is a novel member of the family of nonheme-iron(II)-dependent dioxygenases. The enzyme shows insignificant sequence identity with known dioxygenases.

Several aerobic microorganisms are capable of utilizing acetophenones for their growth (16, 17, 30-32). However, relatively little is known about the oxidative enzymes involved in acetophenone mineralization (45, 47). The catabolism of 4-hydroxyacetophenone in Pseudomonas fluorescens ACB proceeds through the initial formation of 4-hydroxyphenyl acetate and hydroquinone (31, 37, 47). The latter compound is further degraded via 4-hydroxymuconic semialdehyde and maleylacetate to β-ketoadipate (46). We have purified HapA, the enzyme responsible for the Baeyer-Villiger oxidation of 4-hydroxyacetophenone, and expressed its gene in Escherichia coli (37). Moreover, we established that this flavin adenine dinucleotide-containing monooxygenase is useful for the production of phenols and catechols, which are valuable intermediates in the synthesis of pharmaceuticals, agricultural chemicals, and material products (36, 38, 48).

In the accompanying paper (46), we showed that the genes encoding 4-hydroxyacetophenone monooxygenase (hapA), 4-hydroxyphenylacetate esterase (hapB), 4-hydroxymuconic semialdehyde dehydrogenase (hapE), and maleylacetate reductase (hapF) belong to a gene cluster (hapCDEFGHIBA) involved in 4-hydroxyacetophenone utilization. Based on biochemical data and sequence analysis, we proposed that the function of the hapC and hapD genes is linked to the conversion of hydroquinone to 4-hydroxymuconic semialdehyde.

Several ring cleavage enzymes acting on substituted hydroquinones have been described. These include intradiol dioxygenases acting on hydroxyhydroquinone (4, 20, 22, 35, 39, 42, 55, 66) and extradiol dioxygenases that are active with (homo-)gentisate (3, 28) or chlorohydroquinone (10, 44, 51). However, enzymes that use hydroquinone as the physiological ring cleavage substrate have not been characterized. Here we report on the purification and properties of hydroquinone dioxygenase (HQDO) from P. fluorescens ACB. It is shown that the heterotetrameric enzyme, encoded by the hapC and hapD genes, is a novel member of the family of nonheme-iron(II)-dependent dioxygenases. The present results confirm that the hapG gene, encoding an intradiol dioxygenase (46), is not involved in 4-hydroxyacetophenone degradation. This finding has important implications for the function of related genes involved in the catabolism of other aromatic compounds.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Phenolic compounds were purchased from Aldrich or Acros. NADPH, NADH, NAD+, dithiothreitol (DTT), DNase, and RNase were from Boehringer. Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride was from Merck. N,N-bis[2-hydroxyethyl]-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid (BES), bis(2-hydroxyethyl)imino-tris(hydroxymethyl)-methane (BisTris), 3-[cyclohexyl amino]-1-propanesulfonic acid (CAPS), bovine serum albumin (BSA), and 2,2′-dipyridyl and protamine sulfate were from Sigma. Phenanthroline was from Fluka. All other chemicals were of analytical grade.

Bacterial strains and enzymes.

P. fluorescens ACB (31) was grown on 4-hydroxyacetophenone as described before (37). p-Hydroxybenzoate 1-hydroxylase from Candida parapsilosis CBS640 (21), p-hydroxybenzoate 3-hydroxylase from P. fluorescens (73), lipoamide dehydrogenase from Azotobacter vinelandii (77), d-amino acid oxidase from pig kidney (18), and 4-hydroxyacetophenone monooxygenase (HAPMO) from P. fluorescens ACB (37) were purified as described previously.

Purification of HQDO from P. fluorescens ACB.

Purification steps were performed at 4°C, unless stated otherwise. P. fluorescens ACB cells (5 g, wet weight) were suspended in 5 ml of 20 mM BisTris chloride, pH 7.0, containing 1 mM 4-hydroxybenzoate, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, and 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (buffer A). Immediately after the addition of 1 mM EDTA, 2 mM MgCl2, and 1 mg of DNase, cells were disrupted three times through a precooled French press at 10,000 lb/in2. After centrifugation (27,000 × g for 30 min), the clarified cell extract was adjusted to 25% ammonium sulfate saturation. The precipitate thus formed was removed by centrifugation (27,000 × g for 30 min), and the supernatant was loaded onto a phenyl-Sepharose column (1.6 by 11 cm) equilibrated in buffer A containing 25% ammonium sulfate. After a washing step with 3 column volumes of starting buffer, the HQDO activity was eluted with a 100-ml linear gradient of 25 to 0% ammonium sulfate in buffer A. Active fractions were pooled and adjusted to 60% saturation with pulverized ammonium sulfate. The precipitate was collected by centrifugation (27,000 × g for 30 min), dissolved in 1 ml of buffer A, and eluted over a Superdex 75 PG column (2.6 by 54 cm) equilibrated with buffer A containing 50 mM NaCl. Active fractions were pooled and applied onto a Source 30Q column (1.6 by 5 cm) equilibrated in buffer A containing 50 mM NaCl. After a washing step with 3 volumes of starting buffer, the HQDO activity was eluted with a 180-ml linear gradient of 50 to 350 mM NaCl in buffer A. Under these conditions, HQDO eluted at 170 mM NaCl whereas the HAPMO activity eluted at 300 mM NaCl. Active HQDO fractions were pooled, concentrated by ultrafiltration (Amicon Ultra-4 10-kDa membrane), and stored at a concentration of 4.6 mg/ml in 20 mM BisTris-Cl, 10% glycerol, and 170 mM NaCl, pH 7, at −20°C. The HAPMO pool served as a reference in matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization—time of flight (MALDI-TOF) peptide mapping (see below).

Enzyme activity.

Enzyme activity measurements were performed at 25°C using air-saturated buffer. The activity of HAPMO was determined as described before (37). For activity studies with HQDO, the stock enzyme solution (1 ml) was freshly incubated for at least 1 min with 100 μM iron(II) sulfate and desalted over a Biogel P-6DG column (1 by 10 cm) running in 20 mM BisTris, pH 7.0, containing 10% glycerol. HQDO activity was routinely determined spectrophotometrically by monitoring the formation of 4-hydroxymuconic semialdehyde at 320 nm (ɛ320 = 11.0 mM−1 cm−1) (63). The assay mixture (1.0 ml) typically contained 50 to 200 nM enzyme and 10% (wt/vol) glycerol in 20 mM BES, pH 7.0. Reactions were started by the addition of 10 μl of 50 mM hydroquinone in dimethylformamide (DMF). One unit of HQDO activity is defined as the amount of enzyme that forms 1 μmol of semialdehyde product per minute.

Potential aromatic substrates (freshly dissolved in DMF) were tested at concentrations ranging from 10 μM to 10 mM with the total amount of DMF never exceeding 1%. Conversion of 2-fluorohydroquinone was studied by 19F nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). For this purpose, 0.3 mM 2-fluoro-4-hydroxybenzaldehyde was incubated with 0.5 mM NADPH and 0.74 nM HAPMO in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, at 30°C. After NADPH consumption had ceased, the reaction mixture was divided in two parts. One part was incubated for 10 min with 1 μM HQDO, whereas the other part was used as a control. Immediately after the incubation, both samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −20°C.

Potential phenolic inhibitors (freshly dissolved in DMF) were tested at a concentration of 200 μM with 50 μM hydroquinone. For estimation of steady-state kinetic parameters and inhibition constants, hydroquinone concentrations were varied, and fixed amounts of inhibitor were used. Experiments with tetrafluorohydroquinone were performed in the presence of 1 mM ascorbate to suppress auto-oxidation.

The metal ion specificity of HQDO was determined by measuring the activity of nonliganded enzyme in the presence of either 0.1 mM FeSO4, 1 mM (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2, 1 mM FeCl3, or 1 mM MnSO4.

Enzyme stability.

The thermal stability of HQDO was studied by incubating a 6 μM concentration of purified enzyme at 30°C in 20 mM BisTris-Cl-10% glycerol, pH 7.0, in the absence or presence of 1 mM 4-hydroxybenzoate. At time intervals, aliquots were withdrawn from the incubation mixtures and assayed for standard HQDO activity.

Time-dependent inactivation of HQDO was studied by incubating a 34 μM concentration of enzyme at 0°C in 20 mM BisTris-Cl-10% glycerol, pH 7.0, in the presence of, respectively, 0.1 and 1 mM 2,2′-dipyridyl, 0.1 mM o-phenanthroline, and 0.1 and 1 mM hydrogen peroxide. At time intervals, aliquots were withdrawn from the incubation mixtures and assayed for standard HQDO activity.

Analytical methods.

19F NMR measurements were performed as described earlier (46). Absorption spectra were recorded using a Hewlett-Packard 8453 diode array spectrophotometer. Protein content was determined with the microbiuret method (24) using BSA as a standard. Desalting or buffer exchange of protein solutions was performed with Biogel P-6DG columns (Bio-Rad).

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was carried out with 15% Tris-glycine gels (76). An Amersham Pharmacia Biotech low-molecular-mass calibration kit containing phosphorylase b (94 kDa), BSA (67 kDa), ovalbumin (43 kDa), carbonic anhydrase (30 kDa), soybean trypsin inhibitor (20.1 kDa), and α-lactalbumin (14.4 kDa) served as a reference. Proteins were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue G250.

The relative molecular mass of native HQDO was determined by fast protein liquid chromatography gel filtration using a Superdex 200 HR 10/30 column (Amersham Biosciences) running with 20 mM BisTris-Cl, pH 7.0, containing 10% glycerol and 50 mM NaCl. The column was calibrated with catalase (232 kDa), aldolase (158 kDa), lipoamide dehydrogenase (102 kDa), p-hydroxybenzoate 3-hydroxylase (88 kDa), d-amino acid oxidase (80 kDa), BSA (67 kDa), ovalbumin (43 kDa), chymotrypsinogen A (25 kDa), RNase (13.7 kDa), and flavin mononucleotide (480 Da).

MS.

For nanoflow electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) of HQDO, samples were prepared in 50 mM ammonium acetate, pH 6.7. Protein samples were introduced into the nanoflow ESI source of a Micromass LCT mass spectrometer (Waters), modified for high-mass operation and operating in the positive-ion mode. Mass determinations were performed under conditions of increased pressure in the source and intermediate pressure regions in the mass spectrometer (Pirani gauge readback, 700 Pa; Penning gauge readback, 1.2 × 10−4 Pa) (59, 67). HQDO was infused in the mass spectrometer by using in-house pulled and gold-coated borosilicate needles (Kwik-Fil; World Precision Instruments). Borosilicate capillaries were pulled on a P-97 puller (Sutter Instruments) to prepare needles with an orifice of about 5 μm and coated with a thin gold layer (∼500 Å) using an Edwards Scancoat six Pirani 501 sputter coater (Edwards High Vacuum International). Electrospray voltages and source temperature were optimized for transmission of HQDO (capillary voltage, 1,500 V; sample cone voltage, 50 V; extraction cone voltage, 0 V; and capillary temperature, 80°C).

HQDO was also analyzed in the presence of only iron(II) sulfate or 4-hydroxybenzoate by nanoflow-electrospray tandem MS (MS/MS) to determine which subunit binds iron(II) and 4-hydroxybenzoate. The analysis was performed on a modified quadropole TOF instrument with increased pressure in the source of 102 Pa (62, 74). HQDO was subjected to collisions with xenon at pressures of 2 Pa with varied collision energy between 10 V to 100 V to trigger dissociation of the complex. Instrument settings were similar to those described above.

For online size exclusion electrospray MS of HQDO, samples were prepared in 20 mM BisTris-Cl containing 10% glycerol and 50 mM NaCl, pH 7.0. A total of 15 μl of a 20 μM enzyme solution was loaded onto a 10-μl sample loop in a six-port valve. The enzyme was then injected onto a Superdex 200 H/R size exclusion column (3.2 mm by 300 mm; Amersham Biosciences) using a mobile phase of 50 mM ammonium acetate, pH 6.7, at a rate of 50 μl/min, in the presence or absence of 20 μM iron(II) sulfate and 15 μM 4-hydroxybenzoate. The eluent from the column was guided into the electrospray source using a fused silica emitter. In these experiments we did not use the nanoflow source, as the flow was 2 orders of magnitude too high to desolvate the droplets originating from the ionization process. The electrospray source was optimized for transmission of HQDO (capillary voltage, 3,000 V; cone voltage, 125 V; extraction cone voltage, 5 V; and capillary temperature, 250°C). All other settings were similar to the experiments with the borosilicate capillaries. Apparent molecular masses were determined using a calibration curve made with standards from a molecular weight marker kit (Bio-Rad) containing thyroglobulin (670 kDa), bovine gamma globulin (158 kDa), chicken ovalbumin (44 kDa), equine myoglobin (17 kDa), and vitamin B12 (1.35 kDa).

MALDI-TOF peptide mapping and MALDI two-stage TOF (MALDI-TOF-TOF) peptide mapping and sequencing.

Purified HQDO was subjected to SDS-PAGE. Stained protein bands of interest were pierced from the gel with a pipette tip. After a destaining step with 50% acetonitrile in 10 mM NH4HCO3, pH 8.0, the protein-containing gel slices were incubated with 10 mM DTT in 10 mM NH4HCO3 for 1 h at 56°C, followed by a 1-h incubation with 55 mM iodoacetamide at room temperature. The slices were washed three times with 10 mM NH4HCO3 and, after being dried in a vacuum centrifuge, treated with trypsin as described previously (57, 61). The extracted peptides were coprecipitated with α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid using the “dried droplet” method on an Anchorchip plate and measured on an Ultraflex MALDI-TOF instrument (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany). Analysis of mass data was done with Flex Analysis, version 2.0 (Bruker Daltonics). Peak Erazor, version 1.50 (Lighthouse Data, Denmark), was used to eliminate the peaks in the blank and peaks of the matrix, trypsin, and keratin. GPMAW, version 6.10 (Lighthouse Data), was used to compare the peaks with known sequences.

For peptide sequencing an identical approach was followed, but in these experiments the MS and MS/MS measurements were performed on a MALDI-TOF-TOF instrument (AB 4700 Proteomics Analyzer, Applied Biosystems) in a reflectron positive-ion mode using delayed extraction. The instrument is equipped with a 200 Hz neodymium-doped yttrium-aluminum-garnet laser operating at 355 nm. Typically 2,000 shots/spectrum were acquired in the MS mode, and 15,000 shots/spectrum were acquired in the MS/MS mode. During MS/MS analysis air was used as the collision gas. All spectra were calibrated externally using a peptide mixture that consists of 100 fmol of des-Arg bradykinin, angiotensin I, Glu-fibrinopeptide, adrenocorticotropin hormone (ACTH) clip 1 to 17, ACTH clip 7 to 38, and ACTH clip 18 to 39. Mass accuracy is within 50 ppm. The data were analyzed using de novo sequencing by GPS software (Applied Biosystems) and was confirmed by manual examination.

N-terminal sequencing.

The N-terminal sequence of HQDO was determined by Edman degradation. The contents of a 15% SDS-PAGE gel (140 by 120 by 1.5 mm) loaded with 9.2 and 18.4 μg of purified enzyme were blotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride Immobilon-P support (Millipore) in 10 mM CAPS, pH 11.0, containing 10% ethanol. After the membrane was stained with 0.1% Coomassie R-250 in 50% methanol, the main bands corresponding to relative molecular masses of 38, 32, and 18 kDa were excised. Gas phase sequencing of the polypeptide on the Immobilon support was carried out at the sequencing facility of Leiden University, The Netherlands.

Sequence comparison.

As reported in the accompanying paper (46), the nucleotide and amino acid sequences of HQDO have been deposited in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases (accession number AF355751; gi 182374631 and gi 182374632). For sequence alignment studies, a PSI-BLAST (1) search was performed at the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Multiple sequence alignments and an unrooted tree were made with the CLUSTAL W program at the European Bioinformatics Institute (www.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw) (69). BioEdit (26) was used to calculate the pairwise identity and similarity scores (PAM250 matrix) from the aligned sequences and for the display of the alignment. Treeview was used for visualization of the dendrogram (52).

RESULTS

Purification of HQDO from P. fluorescens ACB.

Purification of HQDO was not straightforward. Initial purification attempts, performed either in the absence or presence of 1 mM DTT, resulted in rapid loss of enzyme activity. In these procedures, part of the activity could be restored by incubation of the partially purified enzyme with iron(II) salts. Addition of ascorbate had almost no effect. A dramatic improvement in the yield of active enzyme was obtained after the finding that the enzyme could be stabilized by ligandation with the inhibitor 4-hydroxybenzoate. Table 1 summarizes a typical purification from 5 g of 4-hydroxyacetophenone-grown cells. Purification by four steps resulted in a yield of 38%, a purification factor of 22.5, and a specific activity of 5.9 U mg−1. Purified enzyme, not treated with iron(II) ions, has 10 to 20% of the activity of iron(II)-complexed enzyme.

TABLE 1.

Purification scheme for HQDO from P. fluorescens ACB

| Purification step | Volume (ml) | Activity (U) | Protein (mg) | Specific activity (U mg−1) | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell extract | 7 | 141 | 545 | 0.26 | 100 |

| Ammonium sulfate saturation | 8.5 | 130 | 507 | 0.26 | 92 |

| Phenyl-Sepharose column application | 91 | 89 | 146 | 0.61 | 63 |

| Superdex 75 PG column application | 27 | 74 | 36.7 | 2.02 | 52 |

| Source 30Q column application | 23.5 | 54 | 9.2 | 5.89 | 38 |

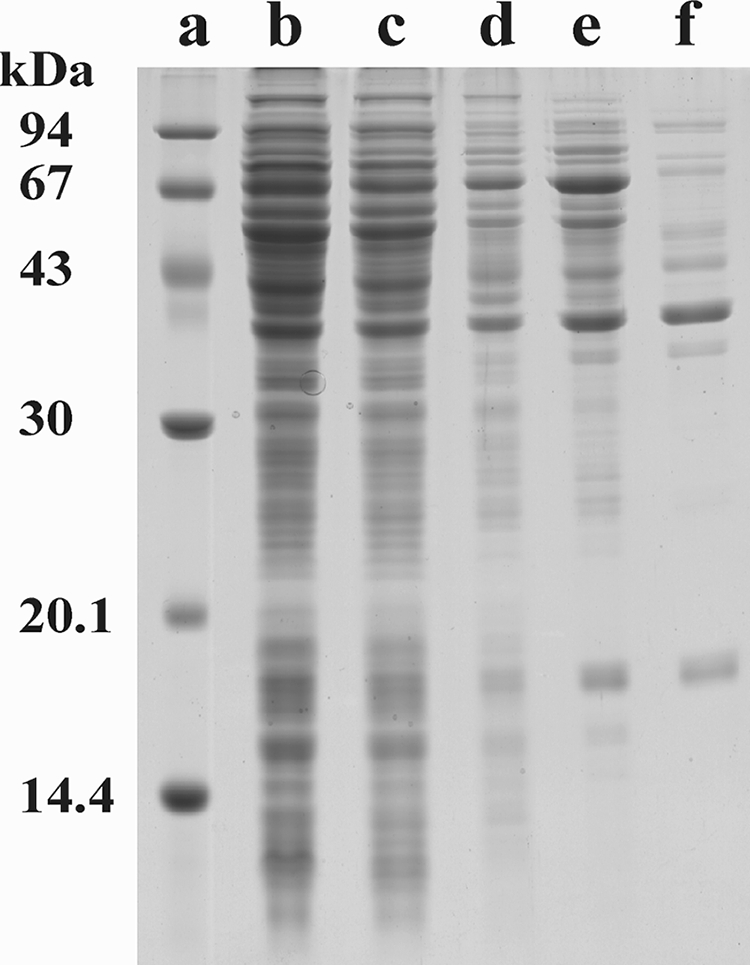

SDS/PAGE analysis of the purified enzyme revealed the presence of one main protein band, corresponding to a molecular mass of about 38 kDa, and several minor bands (Fig. 1). The purified HQDO eluted from an analytical Superdex 200 column in one symmetrical peak with an apparent molecular mass of 105 ± 5 kDa.

FIG. 1.

SDS-PAGE of HQDO from P. fluorescens ACB. Lane a, marker proteins; lane b, cell extract; lane c, ammonium sulfate fractionation supernatant; lane d, phenyl-Sepharose pool; lane e, Superdex 200PG pool; lane f, Source 30Q pool.

Spectral properties.

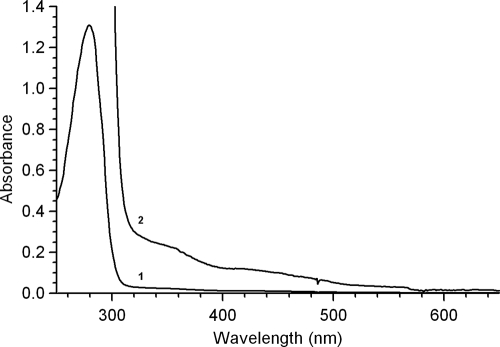

HQDO from P. fluorescens ACB showed an absorption maximum at 279 nm and very weak absorbances around 350 and 420 nm (Fig. 2). A similar feature was described for extradiol dioxygenases (68, 80). For comparison, intradiol dioxygenases display a maximum in the visible region around 450 nm (41, 50) due to tyrosine ligandation (54).

FIG. 2.

Spectral properties of HQDO from P. fluorescens ACB (1). UV-visible light absorption spectrum of 16 μM enzyme as isolated (2). Vertical axis is expanded 10 times.

Catalytic properties.

HQDO from P. fluorescens ACB catalyzed the ring cleavage of hydroquinone to 4-hydroxymuconic semialdehyde with the consumption of stoichiometric amounts of molecular oxygen. The pH optimum for catalysis was between pH 7 and pH 8. At 25°C and pH 7.0, an apparent maximal turnover rate, k′cat, of 2.1 ± 0.1 s−1 and an apparent K′m of 37 ± 3 μM were estimated.

HQDO from P. fluorescens ACB catalyzed the conversion of a wide range of hydroquinones. In addition to the activity of the parent substrate and difluorinated hydroquinones (46), activity was found with methyl-, methoxy-, and chlorohydroquinone and, to a minor extent, with bromohydroquinone (Table 2). Strong substrate inhibition occurred with methoxyhydroquinone and to a lesser extent with chloro- and bromohydroquinone. Tetrafluorohydroquinone, hydroxyhydroquinone (1,2,4-trihydroxybenzene), gentisate (2,5-dihydroxybenzoate), catechol (1,2-dihydroxy-benzene), resorcinol (1,3-dihydroxybenzene), pyrogallol (1,2,3-trihydroxybenzene), and phenol were not converted.

TABLE 2.

Substrate specificity of HQDO from P. fluorescens ACB

| Substrate (200 μM) | Activity (%)a |

|---|---|

| Hydroquinone | 100 |

| Methylhydroquinone | 120 |

| Methoxyhydroquinone | 50 |

| Chlorohydroquinone | 70 |

| Bromohydroquinone | 30 |

| 2,3-Difluorohydroquinone | 80 |

| 2,5-Difluorohydroquinone | 75 |

| 3,5-Difluorohydroquinone | 90 |

Activity expressed as relative absorbance increase at 320 nm.

The activity of HQDO was strongly inhibited by the substrate analog 4-hydroxybenzoate. Kinetic studies revealed that the inhibition was competitive with hydroquinone with an inhibition constant, K′i, of 14 ± 3 μM. Many other phenolic compounds served as HQDO inhibitors. The strongest inhibition was observed with 4-hydroxybenzylic compounds, 4-hydroxycinnamates, tetrafluorohydroquinone, and hydroxyhydroquinone (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Phenolic inhibitors of HQDO

| Inhibitor name | Activity (%) | Inhibitor concn (μM) |

|---|---|---|

| 4-Hydroxybenzoate | 12 | 200 |

| 2,4-Dihydroxybenzoate | 13 | 200 |

| 6 | 400 | |

| 2,3,4-Trihydroxybenzoate | 81 | 200 |

| 2,4,6-Trihydroxybenzoate | 40 | 200 |

| 2-Fluoro-4-hydroxybenzoate | 12 | 200 |

| 3-Fluoro-4-hydroxybenzoate | 19 | 200 |

| 2-Chloro-4-hydroxybenzoate | 23 | 200 |

| 4-Methoxybenzoate | 76 | 200 |

| 4-Hydroxybenzonitrile | 0 | 200 |

| 0 | 40 | |

| 5 | 2 | |

| 4-Hydroxyphenylacetate | 3 | 200 |

| 4-Hydroxybenzylalcohol | 8 | 200 |

| 4-Hydroxybenzaldehyde | 12 | 200 |

| 4-Hydroxybenzylcyanide | 24 | 200 |

| Vanillin | 33 | 200 |

| 61 | 100 | |

| 4-Hydroxyphenethylalcohol | 76 | 200 |

| Vanillyl alcohol | 78 | 200 |

| 4-Hydroxyacetophenone | 83 | 200 |

| Ferulic acid | 24 | 40 |

| 50 | 20 | |

| 4-Hydroxycinnamate | 0 | 200 |

| 0 | 100 | |

| 77 | 20 | |

| Caffeic acid | 59 | 80 |

| 68 | 40 | |

| Tetrafluorohydroquinone | 0 | 200 |

| 9 | 100 | |

| 35 | 40 | |

| 64 | 20 | |

| Hydroxyhydroquinone | 9 | 200 |

| Phenol | 83 | 200 |

| Catechol | 86 | 200 |

| 4-Nitrophenol | 0 | 200 |

| 9 | 100 | |

| 32 | 20 | |

| Isoeugenol | 74 | 200 |

| Chavicol | 82 | 200 |

| Eugenol | 85 | 200 |

Weak or no inhibition was observed with 2-hydroxy-, 3-hydroxy-, 2,3-dihydroxy-, 2,5-dihydroxy-, 2,6-dihydroxy-, 3,4-dihydroxy-, 3,4,5-trihydroxy-, 3-chloro-4-hydroxy-, tetrafluoro-4-hydroxy-, 3-amino-4-hydroxy-, 4-hydroxy-3-methoxy-, 4-amino- and methyl 4-hydroxybenzoate; 6-hydroxynicotinate; 4-hydroxypropiophenone; 4-hydroxymandelate; 4-hydroxyphenylglycine; 4-hydroxybenzenesulfonic acid; and 4-methyl-, 4-methoxy-, and 4-aminophenol.

Enzyme inactivation.

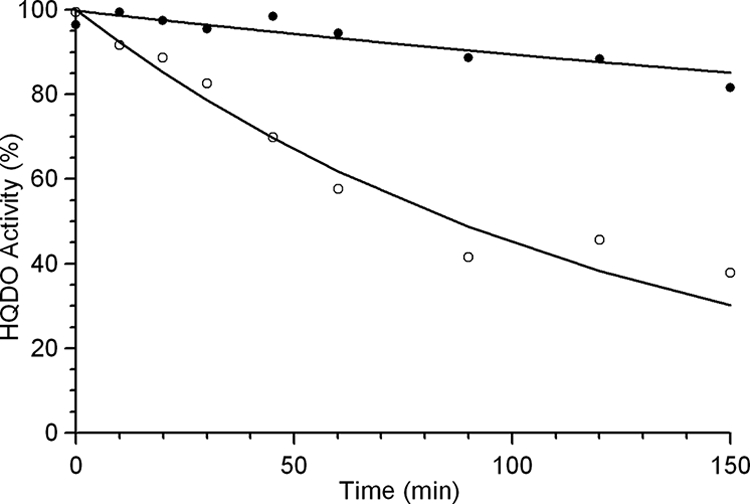

Thermal inactivation studies showed that HQDO was rather unstable. At 30°C and pH 7.0, more than half of the enzyme activity was lost within 2 h (Fig. 3). Binding of the competitive inhibitor 4-hydroxybenzoate strongly increased the thermal stability of HQDO. Using the same incubation conditions as for the free enzyme, about 90% of the activity remained (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Thermal stability of HQDO from P. fluorescens ACB. Time-dependent loss of activity of a 6 μM concentration of purified enzyme at 30°C in 20 mM BisTris-Cl-10% glycerol, pH 7.0, in the absence (○) and presence (•) of 1 mM 4-hydroxybenzoate.

HQDO also lost activity when the enzyme was stored at −20°C in nonliganded form. Most of the activity could be restored by the addition of Fe2+ ions [added as FeSO4 or (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2]. Addition of Fe3+ (FeCl3) or Mn2+ (MnSO4) had no effect. HQDO was inactivated in a time-dependent manner by the iron(II) chelators 2,2′-dipyridyl and ortho-phenanthroline (Table 4). This suggests that the enzyme contains a nonheme iron(II) ion in the active site (13, 14, 27, 63). In line with this, HQDO was inactivated by the oxidizing agent hydrogen peroxide (Table 4). Studies on other dioxygenases have shown that hydrogen peroxide acts on iron(II)-dependent extradiol dioxygenases and not on Mn(II)- and Mg(II)-dependent extradiol dioxygenases (2, 7, 78, 75, 79).

TABLE 4.

Time-dependent inactivation of HQDO by iron(II) modifying agents

| Inactivation agent | Concn (mM) | Half-time of inactivation at 30°C (min) |

|---|---|---|

| 2,2′-Dipyridyl | 0.1 | 60 |

| 1.0 | 20 | |

| o-Phenanthroline | 0.1 | 40 |

| Hydrogen peroxide | 0.1 | 3.5 |

| 1.0 | 1.5 |

Regioselectivity of dioxygenation.

In the accompanying paper we showed that 2,3-difluorohydroquinone and 2,5-difluorohydroqunone undergo ring fission in between C-1 and C-6, yielding the corresponding difluorinated 4-hydroxymuconic semialdehydes (46). Absorption spectral analysis indicated that the regioselectivity of dioxygenation of monohalogenated hydroquinones by HQDO differs with the type and position of the halogen substituents. Activity measurements with chloro- and bromohydroquinone resulted in an increase in absorption at 320 nm, pointing at the formation of a halogenated 4-hydroxymuconic semialdehyde product. In contrast, incubation of fluorohydroquinone with HQDO did not result in an absorption increase at 320 nm. 19F NMR confirmed that in the latter reaction no semialdehyde was formed but that the fluorohydroquinone substrate was enzymatically defluorinated in a time-dependent manner compared to the absence of fluoride anion production in the control experiment. This suggests that the ring cleavage of the fluorinated substrate takes place in between the hydroxyl and fluorine substituent. Such ring cleavage will result in an unstable acyl halide which readily reacts with water, yielding nonfluorinated maleylacetate and halide anion, as described for the conversion of chlorohydroquinones by chlorohydroquinone dioxygenase (9, 51, 81).

N-terminal sequence analysis.

The N-terminal sequence of the protein corresponding to the major band in SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1, lane f) was determined by Edman degradation. The N-terminal sequence of this 38-kDa protein was found to be AMLEAVETEN. Except for the starting methionine, this sequence corresponds with the N-terminal sequence of HapD derived from the DNA sequence (46). The 32- and 18-kDa protein bands observed in lane f of Fig. 1 were also analyzed by Edman degradation. The 32-kDa band was selected because its mass corresponds to that of HapG, a putative hydroxyhydroquinone 1,2-dioxygenase (46). The 18-kDa band was selected because during purification it always coelutes with the 38-kDa protein. The N-terminal sequence of the 32-kDa protein was determined to be AAITAALVKE. This sequence is specific for the translation elongation factor Ts present in many Pseudomonas organisms and suggests that the 32-kDa protein represents an impurity in the HQDO preparation. The N-terminal sequence of the 18-kDa protein was found to be STQPAFKTVF. Except for the starting methionine, this sequence corresponds with the N-terminal sequence of HapC derived from the DNA sequence (46), suggesting that HapC is a distinct subunit of the HQDO protein.

Hydrodynamic properties of HQDO.

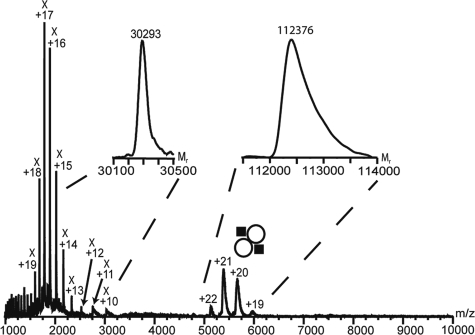

Initial analysis of partially purified HQDO by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) suggested a protein complex with a size corresponding to a molecular mass of about 105 kDa. Electrospray MS analysis of HQDO in the absence of iron(II) sulfate and 4-hydroxybenzoate revealed two series of protein ions having a different number of charges and molecular masses of 30,293 ± 5 Da and 112,376 ± 50 Da (Fig. 4). The 30-kDa protein is likely to be the translation elongation factor Ts impurity already identified by Edman degradation.

FIG. 4.

Nanoelectrospray MS spectrum of HQDO directly infused from capillaries using gentle conditions. This spectrum shows two charge envelopes. The first charge distribution at m/z 1,000 to 3,000 with charges from +10 to +20 corresponds to a protein of 30 kDa, which is likely the translation elongation factor Ts. The second charge distribution at m/z 5,000 to 6,000 with charges between +19 to +22 reveals a mass of 112 kDa and corresponds to the intact HQDO protein complex. The instrument settings were chosen such that no fragmentation of the protein assembly occurs. In the insets, the transformation of the charge envelopes to their molecular masses is shown. , HQDO α2β2 tetramer.

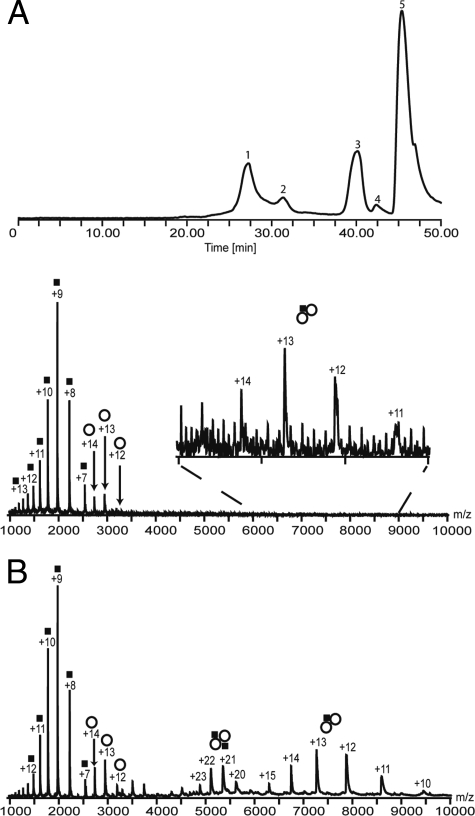

The subunit composition of the HQDO protein assembly was studied in more detail by coupling SEC to MS. The ion chromatography of HQDO in the absence of iron(II) sulfate and 4-hydroxybenzoate showed two protein peaks eluting around 27 and 31 min (Fig. 5A, top). The late-eluting compounds around 41 min are smaller molecules, and the peak around 47 min corresponds with the total volume of the column. Peak 1, eluting after 27 min, resulted in three ion series in the mass spectra in between m/z 1,300 and m/z 8,500 (Fig. 5A, bottom). The corresponding molecular masses for these three ion series were 17,769 ± 1 Da, 38,288 ± 10 Da, and 94,477 ± 45 Da. As the elution volume of this peak suggests a hydrodynamic volume corresponding to a mass of about 100 kDa, the observed proteins in the mass spectrum are likely to be fragments of the larger protein assembly. The masses of these fragments correspond with the subunit molecular masses observed in SDS-PAGE and with the masses calculated from the HapC and HapD sequences, suggesting that they are part of the HQDO assembly. The peak eluting at 31 min contained a protein with a mass of 30.3 kDa, corresponding to the size of the elongation factor (mass spectrum not shown).

FIG. 5.

Online SEC-MS analysis of HQDO in the absence and presence of iron(II) sulfate and 4-hydroxybenzoate. (A) Elution ion chromatogram of HQDO without iron(II) sulfate and 4-hydroxybenzoate and subsequent analysis by ESI-MS (top). Peak 1 corresponds to HQDO; peak 2 corresponds to a 30-kDa protein, possibly the translation elongation factor Ts; and peaks 3 and 4 correspond to small molecules. Peak 5 is consistent with the void volume of the column. The ion chromatogram of HQDO with iron(II) sulfate and 4-hydroxybenzoate yielded a similar trace. ESI mass spectrum composed by combining scans from peak 1 of the ion elution chromatogram (bottom). This spectrum shows mainly two charge distributions between m/z 1,000 and 3,500. The first charge envelope (▪) corresponds to the α-monomer of HQDO with a mass of 17.8 kDa, the second charge distribution (○), corresponds to the β-monomer with a mass of 38.3 kDa, and the third charge state series corresponds with a molecular mass of 94.4 kDa (α1β2). (B) ESI mass spectrum of peak 1 in the presence of iron(II) sulfate and 4-hydroxybenzoate. This spectrum shows four major charge distributions. The first charge envelope (▪) ranging from +7 to +14 at m/z 1,000 to 2,600, corresponds with the α-monomer of HQDO with a mass of 17.8 kDa. The second charge distribution (○) ranging from +12 to +14 at m/z 2,700 to 3,200, refers to the β-monomer with a mass of 38.3 kDa. The third charge envelope from +20 to +23 at m/z 4,800 to 5,700, corresponds to the tetramer of HQDO (α2β2) with a mass of 112.4 kDa. The fourth charge distribution from +10 to +15 at m/z 6,300 to 9,500 refers to the trimer (α1β2) with a mass of 94.4 kDa. , α1β2 trimer; , α2β2 tetramer.

In a subsequent online SEC-MS experiment, we added iron(II) sulfate and 4-hydroxybenzoate to the protein sample before injection onto the column. This protein sample yielded a similar elution chromatogram as the experiment without iron(II) sulfate and 4-hydroxybenzoate (data not shown). However, the accumulated mass spectra of the peak around 27 min were clearly different (Fig. 5B). Mass determination of the ion series centered around 5,400 m/z revealed a mass of 112,387 ± 50 Da. This mass spectrum also showed ion series in which the determined protein mass was 17,769 ± 5 Da and 38,283 ± 10 Da and mass of the trimeric subcomplex was 94,488 ± 45 Da (Fig. 5B). These fragments were generated from the 112-kDa protein assembly by gas phase dissociation.

The calculated mass based on the primary sequence is 38,268.98 without the methionine at position 1. The observed mass by online SEC-MS is 38,283 ± 10 Da in the absence of iron(II) sulfate and 4-hydroxybenzoate.

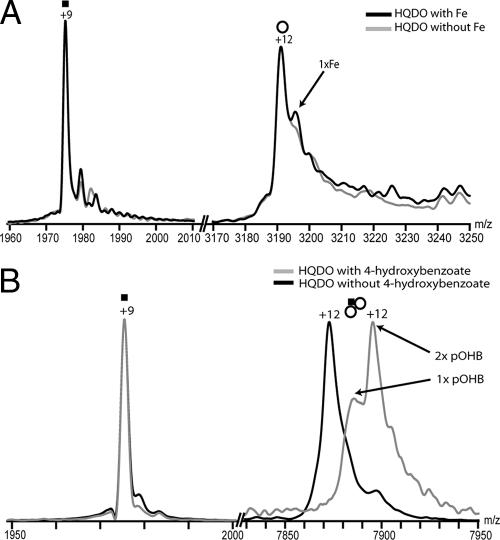

These results unambiguously show that native HQDO has a mass of 112 kDa and is composed of two α-subunits of 17.8 kDa and two β-subunits of 38.3 kDa. The addition of iron(II) sulfate resulted in a new ion peak near the original ion peaks of the monomeric β-subunit at m/z 3,190, but not near the ion peaks of the monomeric α-subunit at m/z 1,975 (Fig. 6A). Mass determination revealed a mass difference of 55 Da, strongly indicating the interaction between the β-subunit with one molecule of iron(II). This interaction was likely to be specific, as we did not observe any interaction between the α-subunit and iron(II). In dissociation experiments the HQDO heterotetramer was fragmented into an α-monomer and a αβ2-trimer. Upon the addition of 4-hydroxybenzoate to HQDO, a peak shift in the trimeric ions of HQDO (αβ2) corresponding to a mass shift of 270 Da was observed (Fig. 6B), which may suggest that, under the experimental conditions applied, one 4-hydroxybenzoate molecule (molecular mass of 138 Da) binds to one β-subunit. Again, no changes were observed in the α-subunit ions.

FIG. 6.

MS analysis of HQDO monomers. (A) HQDO monomer after the addition of iron(II)sulfate. Overlay and zoom in to the +9 charge state of the α-subunit and of the +12 charge state of the β-subunit. In gray the trace of HQDO without iron(II) sulfate is seen whereas the black trace represents HQDO after the addition of iron(II) sulfate. The +12 charge state of the β-subunit shows one additional adduct peak after the addition of iron(II) sulfate, whereas the +9 charge state of the α-subunit remains unchanged. The adduct peaks in the β-subunit correspond to a mass of 55 units, strongly indicating that one iron molecule binds to the β-monomer. (B) HQDO monomer after the addition of 4-hydroxybenzoate. Overlay and zoom views of the +9 charge state of the α-subunit and of the +12 charge state of the trimeric subcomplex. Traces represent HQDO with and without 4-hydroxybenzoate. The +12 charge state of the trimeric subcomplex shows a considerable mass shift to higher m/z after the addition of 4-hydroxybenzoate, whereas the +9 charge state of the α-subunit remains unchanged. The mass shift corresponds to a mass of 270 units, strongly indicating that two molecules of 4-hydroxybenzoate are bound to the trimeric subcomplex. pOHB, 4-hydroxybenzoate. , α1β2 trimer.

Peptide mapping and sequencing.

In-gel tryptic digestion of HapA (Fig. 1, 67-kDa band in lane e) and subsequent MALDI-TOF analysis yielded 56 peptides. Comparison of these peptides with the known sequence of HapA (37) gave 66% sequence overlap with 42 out of 56 peptides.

MALDI-TOF analysis of the tryptic digests of the 38-kDa band of HQDO (Fig. 1, lane f) revealed 22 peptide fragments (m/z: 1,239.6, 1,557.7, 1,868.7, 1,884.8, 1,979.8, 1,985.8, 2,007.2, 2,021.8, 2,033.9, 2,135.9, 2,231.9, 2,247.9, 2,296.9, 2,326.9, 2,424.9, 2,476.9, 2,750.6, 2,756.3, 3,209.0, 3,248.1, 3,368.1, and 3,408.1). Database mass analysis of these peptides yielded no significant mapping with any protein in the Swissprot database. However, 14 peptides corresponded with the sequence of HapD (46) and covered 55% of the protein sequence (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

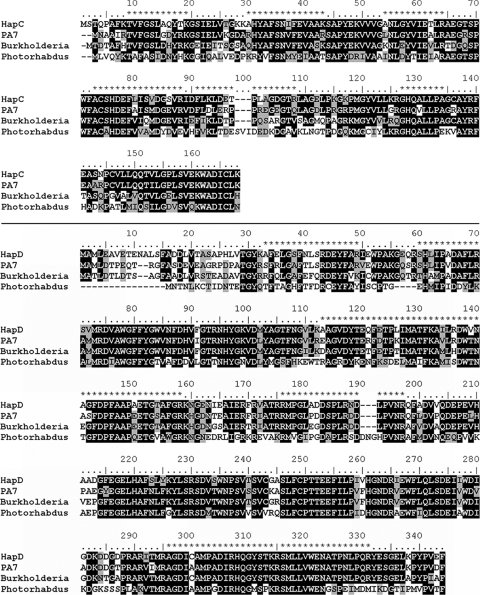

Multiple sequence alignment of the α- and β-subunits of HQDO from P. fluorescens ACB. CLUSTAL W alignment of the amino acid sequences of HapC and HapD from P. fluorescens ACB and hypothetical proteins from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA7 (gi 152988009 and gi 152987326), Burkholderia sp. strain 383 (gi 78063587 and gi 78063586), and Photorhabdus luminescens subsp. laumondii TTO1 (gi 37524165 and gi 37524166). Conserved residues are in dark boxes, and similar residues are in gray boxes. The amino acid sequences predicted by MALDI-TOF-TOF peptide mapping and sequencing are depicted on top of the CLUSTAL W alignment by asterisks. Related sequences of other Burkholderia species (B. cepacia AMMD [gi 115359956 and gi 115359957], Burkholderia ambifaria MC40-6 [gi 11869769 and gi 118697689], Burkholderia cenocepacia PC184 [gi 84353671 and gi 84353670], Burkholderia multivorans ATCC 17616[gi 118718179 and gi 118718178], Burkholderia phymatum STM815 [gi 118032827 and gi 118032828], and Burkholderia cenocepacia HI2424 [gi 116691528 and gi 116691529]) are not shown in the alignment but are very similar to the Burkholderia sp. strain 383 sequences.

Analysis of the 18-kDa band (Fig. 1, lane f) showed that this band corresponds to the HapC protein (46). MALDI-TOF-TOF analysis of tryptic fragments yielded 59% of the total amino acid sequence (Fig. 7) by mapping 7 of 16 expected peptides (m/z: 1,214.7, 1,413.8, 1,583.9, 1,645.1, 1,712.0, 1,861.1, and 2667.3).

DISCUSSION

This paper describes the purification and initial characterization of HQDO, an unusual ring cleavage enzyme involved in the catabolism of 4-hydroxyacetophenone in P. fluorescens ACB. HQDOs have been described in degradation pathways of Sphingobium chlorophenolicum (9), Pseudomonas sp. strain HH35 (60), Arthrobacter protophormiae (14), Burkholderia cepacia (15), Pseudomonas putida JD1 (19), and Moraxella (63). However, purification procedures or amino acid sequence data were not reported for any of these enzymes.

Binding of the competitive inhibitor 4-hydroxybenzoate increased the stability of HQDO and allowed, for the first time, purification of this enzyme in its active form. Hydrogen peroxide and the iron chelators 2,2′-dipyridyl and o-phenanthroline inactivated HQDO. From this and its catalytic features, we concluded that HQDO belongs to the family of nonheme-iron(II)-dependent dioxygenases.

HQDO from P. fluorescens ACB catalyzed the ring fission of a wide range of hydroquinones to the corresponding 4-hydroxymuconic semialdehydes. Substrate profiling showed that both para-hydroxyl groups of hydroquinone are crucial for enzyme activity. Hydroquinones with an electron-donating methyl or methoxy group were readily converted. Hydroquinones containing electron-withdrawing substituents were also converted, albeit at lower rates. The number and position of fluorine substituents determined both the reaction rate and the regioselectivity of dioxygenation. With 2-fluorohydroquinone, ring splitting occurred in between C-1 (bonded to an OH) and C-2 (bonded to a F). 2,3-Difluorohydroquinone was cleaved in between C-1 (bonded to an OH) and C-6 (bonded to a H) (46), and tetrafluorohydroquinone turned out to be a strong inhibitor. Introduction of a hydroxyl (hydroxyhydroquinone) or carboxyl (gentisate) group at the ortho-position resulted in strong or weak enzyme inhibition, respectively. These results suggest that the activity of HQDO is determined by both electronic and steric constraints and that substrates may become differently oriented in the active site.

HQDO was reversibly inhibited by a large number of phenolic compounds. 4-Hydroxybenzylic compounds and 4-hydroxycinnamates were strong inhibitors. From this and the fact that the inhibition by 4-hydroxybenzoate was found to be competitive with hydroquinone, it is concluded that the 4-hydroxyl group serves as the iron ligand and that the para-substituent of the phenol is an important determinant for discriminating between weak and tight binding.

HQDO from P. fluorescens ACB appeared to be a heterotetramer built up by subunits of 18 and 38 kDa. Online SEC-MS was used to elucidate the components and stoichiometry of the protein assembly. This is one of the first examples in which SEC-MS was used to elucidate the stoichiometry and oligomeric state of a protein complex. Cavanagh et al. (12) used the coupling of SEC to establish the oligomeric state of the transition state regulator AbrB and the stoichiometry of its interaction with DNA. Moreover SEC-MS has been shown to be a valuable method for online separation of products in a reaction mixture with subsequent MS analysis (72) The mass of the β-subunit agrees well with the theoretical mass based on the primary sequence of protein HapD encoded by the hapD gene (46).

Using MS/MS analysis 7 peptides of the HQDO α-subunit and 14 peptides of the HQDO β-subunit were sequenced. These data confirmed that HQDO is encoded by the hapC and hapD genes. Except for nine noncharacterized orthologous hapCD clusters present in the sequenced genomes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA7, P. luminescens subsp. laumondii TTO1, and seven Burkholderia strains, HQDO showed no significant sequence similarity with any other protein. The heterotetrameric character of HQDO clearly discriminates the enzyme from most other nonheme-iron(II)-dependent dioxygenases. Except for protocatechuate 4,5-dioxygenase and 2-aminophenol 1,6-dioxygenase, they all consist of one type of subunit (6, 68). From the sequence alignment it appears that HQDO is to some extent related to 3-hydroxyanthranilate 3,4-dioxygenase but that HQDO constitutes a new type of enzyme in the iron(II)-dependent dioxygenase family.

The size and subunit composition of HQDO suggest that the enzyme contains two active sites per heterotetramer. As for protocatechuate 4,5-dioxygenase (65) and 2-aminophenol 1,6-dioxygenase (40), these active sites are likely positioned in the larger subunits. Our MS analysis showed that each β-subunit binds one molecule of the competitive inhibitor 4-hydroxybenzoate. Moreover, the binding of one iron atom to the monomeric β-subunit was observed. This is reminiscent of other heteromeric extradiol dioxygenases that have one iron atom per α2β2 tetramer (2, 68), although protocatechuate 4,5-dioxygenase from Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes JS45 was shown to contain two iron atoms per α2β2 tetramer (40). Whether native HQDO contains one or two iron atoms per heterotetramer cannot be deduced from the charge envelope of the complex as the peak resolution decreases compared to the monomeric species.

The active site of iron(II)-dependent dioxygenases generally harbors two histidines and a glutamate that are involved in binding the iron (58, 70). Most of these enzymes use a catechol as a substrate. When a catecholic substrate binds, the two hydroxyl groups of the substrate replace two water molecules in iron ligandation (58). The strong iron-chelating properties of a catecholic compound are nicely illustrated by the action of enterochelin, a catecholate siderophore that scavenges iron during bacterial infections (23). In the case of HQDO, the question arises as to how the interaction between the phenolic substrate and the iron cofactor occurs. Here, the situation has to be different because the hydroquinone substrate does not contain an ortho-hydroxyl group. The same is true for (homo)gentisate dioxygenases. Based on the crystal structure of substrate-free human homogentisate dioxygenase (70) and electron paramagnetic resonance studies (29), it was proposed that in this enzyme the carboxylate anion of (homo)gentisate serves as an iron ligand as does the phenolate group of catechol in catechol dioxygenases. For HQDO, the active-site residues involved in binding the iron could not simply be predicted from sequence alignments. Based on the sequence similarity with 3-hydroxyanthranilate 3,4-dioxygenases, His258 and His305 could serve as iron ligands in HapD. In addition to the two histidines and an acidic residue, another residue might be involved in binding the metal cofactor (8, 43, 54, 56, 64). Another possibility is that upon hydroquinone binding, the iron atom remains bound to one or more water molecules.

The identification of the two subunits of HQDO confirms our earlier proposal (46) that the HQDO encoding the hapC and hapD genes is part of the hapCDEFGHIBA gene cluster. The HapC sequence shows significant homology with only nine other protein sequences (49 to 78% sequence identity) that are present in the microbial genome database (Fig. 7). All of these bacterial genes are neighbored by a hapD ortholog (Fig. 7). This conserved gene clustering is in line with the tight interaction between HapC and HapD. We suspect that HapC is also homologous to the open reading frame found downstream of pnpS in P. fluorescens ENV2030 (5, 82). Unfortunately, the genome sequence of the latter organism has not yet been published (5, 82). The α- and β-subunits of the (putative) HQDOs mutually have little sequence similarity, suggesting that they have a different ancestor. Furthermore, HapD has no significant sequence identity with known nonheme-iron(II)-dependent dioxygenases.

Interestingly, amino acids 258 to 323 of HapD show 25% sequence identity with amino acids 50 to 116 of 3-hydroxyanthranilate 3,4-dioxygenase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. This monomeric enzyme, involved in the kynurenine pathway (11), is also an iron(II)-dependent dioxygenase. Hydroxyanthranilate 3,4-dioxygenases contain two conserved histidines, which are thought to be involved in iron ligandation (49). Selective replacement of these residues by alanine resulted in no detectable activity (49). The conserved histidines of 3-hydroxyanthranilate 3,4-dioxygenases correspond to His258 and His305 in HapD. Therefore, these histidines might serve as iron ligands in HapD.

With the elucidation of the function of the hapC and hapD genes and the observed instability of the HQDO protein, it is tempting to speculate on the function of the ferredoxin encoded by the hapI gene (46). For catechol 2,3-dioxygenases it was reported that in some degradation pathways, these proteins are needed for the reductive reactivation of the iron cofactor (25, 33, 34, 53, 71). A similar in vivo protection of HQDO can be envisioned for HapI.

In summary, this paper describes the first purification and characterization of an HQDO. The enzyme is a heterotetramer composed of 18- and 38-kDa subunits and is the prototype of a novel subclass of the family of iron(II)-dependent dioxygenases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sjef Boeren and Olga Militsyna for help with some of the experiments and Maurice Franssen for discussion.

This work was supported by the Council for Chemical Sciences of The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research through the division Procesvernieuwing voor een Schoner Milieu. We thank The Netherlands Proteomics Center for financial support.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 23 May 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaeffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 253389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arciero, D. M., J. D. Lipscomb, B. H. Huynh, T. A. Kent, and E. Munck. 1983. EPR and Mossbauer studies of protocatechuate 4,5-dioxygenase. Characterization of a new Fe2+ environment. J. Biol. Chem. 25814981-14991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arias-Barrau, E., E. R. Olivera, J. M. Luengo, C. Fernandez, B. Galan, J. L. Garcia, E. Diaz, and B. Minambres. 2004. The homogentisate pathway: a central catabolic pathway involved in the degradation of l-phenylalanine, l-tyrosine, and 3-hydroxyphenylacetate in Pseudomonas putida. J. Bacteriol. 1865062-5077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armengaud, J., K. N. Timmis, and R. M. Wittich. 1999. A functional 4-hydroxysalicylate/hydroxyquinol degradative pathway gene cluster is linked to the initial dibenzo-p-dioxin pathway genes in Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1. J. Bacteriol. 1813452-3461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bang, S.-W., and G. J. Zylstra. 1997. Cloning and sequencing of the hydroquinone 1,2-dioxygenase, γ-hydroxymuconic semialdehyde dehydrogenase, maleylacetate reductase genes from Pseudomonas fluorescens ENV2030, abstr. Q-383, p.519. Abstr. 97th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- 6.Bertini, I., F. Briganti, S. Mangani, H. F. Nolting, and A. Scozzafava. 1995. Biophysical investigation of bacterial aromatic extradiol dioxygenases involved in biodegradation processes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 144321-345. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boldt, Y. R., M. J. Sadowsky, L. B. Ellis, L. Que, Jr., and L. P. Wackett. 1995. A manganese-dependent dioxygenase from Arthrobacter globiformis CM-2 belongs to the major extradiol dioxygenase family. J. Bacteriol. 1771225-1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyington, J. C., B. J. Gaffney, and L. M. Amzel. 1993. The three-dimensional structure of an arachidonic acid 15-lipoxygenase. Science 2601482-1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cai, M., and L. Xun. 2002. Organization and regulation of pentachlorophenol-degrading genes in Sphingobium chlorophenolicum ATCC 39723. J. Bacteriol. 1844672-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cain, R. B., P. Fortnagel, S. Hebenbrock, G. W. Kirby, H. J. McLenaghan, G. V. Rao, and S. Schmidt. 1997. Biosynthesis of a cyclic tautomer of (3-methylmaleyl)acetone from 4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethylbenzoate by Pseudomonas sp. HH35 but not by Rhodococcus rhodochrous N75. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 238197-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calderone, V., M. Trabucco, V. Menin, A. Negro, and G. Zanotti. 2002. Cloning of human 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid dioxygenase in Escherichia coli: characterisation of the purified enzyme and its in vitro inhibition by Zn2+. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1596283-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cavanagh, J., R. Thompson, B. Bobay, L. M. Benson, and S. Naylor. 2002. Stoichiometries of protein-protein/DNA binding and conformational changes for the transition-state regulator AbrB measured by pseudo cell-size exclusion chromatography-mass spectrometry. Biochemistry 417859-7865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chapman, P. J., and D. J. Hopper. 1968. The bacterial metabolism of 2,4-xylenol. Biochem. J. 110491-498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chauhan, A., A. K. Chakraborti, and R. K. Jain. 2000. Plasmid-encoded degradation of p-nitrophenol and 4-nitrocatechol by Arthrobacter protophormiae. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 270733-740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chauhan, A., S. K. Samanta, and R. K. Jain. 2000. Degradation of 4-nitrocatechol by Burkholderia cepacia: a plasmid-encoded novel pathway. J. Appl. Microbiol. 88764-772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cripps, R. E. 1975. The microbial metabolism of acetophenone. Metabolism of acetophenone and some chloroacetophenones by an Arthrobacter species. Biochem. J. 152233-241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cripps, R. E., P. W. Trudgill, and J. G. Whateley. 1978. The metabolism of 1-phenylethanol and acetophenone by Nocardia T5 and an Arthrobacter species. Eur. J. Biochem. 86175-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Curti, B., S. Ronchi, U. Branzoli, G. Ferri, and C. H. Williams, Jr. 1973. Improved purification, amino acid analysis and molecular weight of homogenous d-amino acid oxidase from pig kidney. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 327266-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Darby, J. M., D. G. Taylor, and D. J. Hopper. 1987. Hydroquinone as the ring-fission substrate in the catabolism of 4-ethylphenol and 4-hydroxyacetophenone by Pseudomonas putida JD1. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1332137-2146. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daubaras, D. L., K. Saido, and A. M. Chakrabarty. 1996. Purification of hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase and maleylacetate reductase: the lower pathway of 2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acid metabolism by Burkholderia cepacia AC1100. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 624276-4279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eppink, M. H. M., S. A. Boeren, J. Vervoort, and W. J. H. van Berkel. 1997. Purification and properties of 4-hydroxybenzoate 1-hydroxylase (decarboxylating), a novel flavin adenine dinucleotide-dependent monooxygenase from Candida parapsilosis CBS604. J. Bacteriol. 1796680-6687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferraroni, M., J. Seifert, V. M. Travkin, M. Thiel, S. Kaschabek, A. Scozzafava, L. Golovleva, M. Schlömann, and F. Briganti. 2005. Crystal structure of the hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase from Nocardioides simplex 3E, a key enzyme involved in polychlorinated aromatics biodegradation. J. Biol. Chem. 28021144-21154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flo, T. H., K. D. Smith, S. Sato, D. J. Rodriguez, M. A. Holmes, R. K. Strong, S. Akira, and A. Aderem. 2004. Lipocalin 2 mediates an innate immune response to bacterial infection by sequestrating iron. Nature 432917-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goa, J. 1953. A micro biuret method for protein determination. Determination of total protein in cerebrospinal fluid. Scan. J. Clin. Lab. Investig. 5218-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Göbel, M., O. H. Kranz, S. R. Kaschabek, E. Schmidt, D. H. Pieper, and W. Reineke. 2004. Microorganisms degrading chlorobenzene via a meta-cleavage pathway harbor highly similar chlorocatechol 2,3-dioxygenase-encoding gene clusters. Arch. Microbiol. 182147-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hall, T. A. 1999. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 4195-98. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanne, L. F., L. L. Kirk, S. M. Appel, A. D. Narayan, and K. K. Bains. 1993. Degradation and induction specificity in Actinomycetes that degrade p-nitrophenol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 593505-3508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harpel, M. R., and J. D. Lipscomb. 1990. Gentisate 1,2-dioxygenase from Pseudomonas. Purification, characterization, and comparison of the enzymes from Pseudomonas testosteroni and Pseudomonas acidovorans. J. Biol. Chem. 2656301-6311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harpel, M. R., and J. D. Lipscomb. 1990. Gentisate 1,2-dioxygenase from Pseudomonas. Substrate coordination to active site Fe2+ and mechanism of turnover. J. Biol. Chem. 26522187-22196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Havel, J., and W. Reineke. 1993. Microbial degradation of chlorinated acetophenones. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 592706-2712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Higson, F. K., and D. D. Focht. 1990. Bacterial degradation of ring-chlorinated acetophenones. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 563678-3685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hopper, D. J., H. G. Jones, E. A. Elmorsi, and M. E. Rhodes-Roberts. 1985. The catabolism of 4-hydroxyacetophenone by an Alcaligenes sp. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1311807-1814. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hugo, N., J. Armengaud, J. Gaillard, K. N. Timmis, and Y. Jouanneau. 1998. A novel [2Fe-2S] ferredoxin from Pseudomonas putida mt2 promotes the reductive reactivation of catechol 2,3-dioxygenase. J. Biol. Chem. 2739622-9629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hugo, N., C. Meyer, J. Armengaud, J. Gaillard, K. N. Timmis, and Y. Jouanneau. 2000. Characterization of three XylT-like [2Fe-2S] ferredoxins associated with catabolism of cresols or naphthalene: evidence for their involvement in catechol dioxygenase reactivation. J. Bacteriol. 1825580-5585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jain, R. K., J. H. Dreisbach, and J. C. Spain. 1994. Biodegradation of p-nitrophenol via 1,2,4-benzenetriol by an Arthrobacter sp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 603030-3032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kamerbeek, N. M., D. B. Janssen, W. J. H. van Berkel, and M. W. Fraaije. 2003. Baeyer-Villiger monooxygenases, an emerging family of flavin-dependent biocatalysts. Adv. Synth. Catal. 345667-678. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kamerbeek, N. M., M. J. H. Moonen, J. G. M. van der Ven, W. J. H. van Berkel, M. W. Fraaije, and D. B. Janssen. 2001. 4-Hydroxyacetophenone monooxygenase from Pseudomonas fluorescens ACB. A novel flavoprotein catalyzing Baeyer-Villiger oxidation of aromatic compounds. Eur. J. Biochem. 2682547-2557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kamerbeek, N. M., A. J. Olsthoorn, M. W. Fraaije, and D. B. Janssen. 2003. Substrate specificity and enantioselectivity of 4-hydroxyacetophenone monooxygenase. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69419-426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Latus, M., H. Seitz, J. Eberspacher, and F. Lingens. 1995. Purification and characterization of hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase from Azotobacter sp. strain GP1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 612453-2460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lendenmann, U., and J. C. Spain. 1996. 2-aminophenol 1,6-dioxygenase: a novel aromatic ring cleavage enzyme purified from Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes JS45. J. Bacteriol. 1786227-6232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lipscomb, J. D., and A. M. Orville. 1992. Mechanistic aspects of dihydroxybenzoate dioxygenases, p. 243-298. In H. Sigel and A. Sigel (ed.), Degradation of environmental pollutants by microorganisms and their metalloenzymes. Metal ions in biological systems, vol. 28. Dekker, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Middelhoven, W. J., A. Coenen, B. Kraakman, and M. D. Sollewijn Gelpke. 1992. Degradation of some phenols and hydroxybenzoates by the imperfect ascomycetous yeasts Candida parapsilosis and Arxula adeninivorans: evidence for an operative gentisate pathway. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 62181-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Minor, W., J. Steczko, J. T. Bolin, Z. Otwinowski, and B. Axelrod. 1993. Crystallographic determination of the active site iron and its ligands in soybean lipoxygenase L-1. Biochemistry 326320-6323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miyauchi, K., Y. Adachi, Y. Nagata, and M. Takagi. 1999. Cloning and sequencing of a novel meta-cleavage dioxygenase gene whose product is involved in degradation of γ-hexachlorocyclohexane in Sphingomonas paucimobilis. J. Bacteriol. 1816712-6719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moonen, M. J. H., M. W. Fraaije, I. M. C. M. Rietjens, C. Laane, and W. J. H. Van Berkel. 2002. Flavoenzyme-catalyzed oxygenations and oxidations of phenolic compounds. Adv. Synth. Catal. 3441023-1035. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moonen, M. J. H., N. M. Kamerbeek, A. H. Westphal, S. A. Boeren, D. B. Janssen, M. W. Fraaije, and W. J. H. Van Berkel. 2008. Elucidation of the 4-hydroxyacetophenone catabolic pathway in Pseudomonas fluorescens ACB. J. Bacteriol. 1905190-5198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moonen, M. J. H., I. M. C. M. Rietjens, and W. J. H. van Berkel. 2001. 19F NMR study on the biological Baeyer-Villiger oxidation of acetophenones. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2635-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moonen, M. J. H., A. H. Westphal, I. M. C. M. Rietjens, and W. J. H. Van Berkel. 2005. Enzymatic Baeyer-Villiger oxidation of benzaldehydes. Adv. Synth. Catal. 3471027-1034. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Muraki, T., M. Taki, Y. Hasegawa, H. Iwaki, and P. C. Lau. 2003. Prokaryotic homologs of the eukaryotic 3-hydroxyanthranilate 3,4-dioxygenase and 2-amino-3-carboxymuconate-6-semialdehyde decarboxylase in the 2-nitrobenzoate degradation pathway of Pseudomonas fluorescens strain KU-7. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 691564-1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nakai, C., T. Nakazawa, and M. Nozaki. 1988. Purification and properties of catechol 1,2-dioxygenase (pyrocatechase) from Pseudomonas putida mt-2 in comparison with that from Pseudomonas arvilla C-1. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 267701-713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ohtsubo, Y., K. Miyauchi, K. Kanda, T. Hatta, H. Kiyohara, T. Senda, Y. Nagata, Y. Mitsui, and M. Takagi. 1999. PcpA, which is involved in the degradation of pentachlorophenol in Sphingomonas chlorophenolica ATCC 39723, is a novel type of ring-cleavage dioxygenase. FEBS Lett. 459395-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Page, R. D. M. 1996. TREEVIEW: An application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 12357-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Polissi, A., and S. Harayama. 1993. In vivo reactivation of catechol 2,3-dioxygenase mediated by a chloroplast-type ferredoxin: a bacterial strategy to expand the substrate specificity of aromatic degradative pathways. EMBO J. 123339-3347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Que, L. J., and R. Y. N. Ho. 1996. Dioxygen activation by enzymes with mononuclear non-heme iron active sites. Chem. Rev. 962607-2624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rieble, S., D. K. Joshi, and M. H. Gold. 1994. Purification and characterization of a 1,2,4-trihydroxybenzene 1,2-dioxygenase from the basidiomycete Phanerochaete chrysosporium. J. Bacteriol. 1764838-4844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Roach, P. L., I. J. Clifton, V. Fulop, K. Harlos, G. J. Barton, J. Hajdu, I. Andersson, C. J. Schofield, and J. E. Baldwin. 1995. Crystal structure of isopenicillin N synthase is the first from a new structural family of enzymes. Nature 375700-704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rosenfeld, J., J. Capdevielle, J. C. Guillemot, and P. Ferrara. 1992. In-gel digestion of proteins for internal sequence analysis after one- or two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Anal. Biochem. 203173-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sato, N., Y. Uragami, T. Nishizaki, Y. Takahashi, G. Sazaki, K. Sugimoto, T. Nonaka, E. Masai, M. Fukuda, and T. Senda. 2002. Crystal structures of the reaction intermediate and its homologue of an extradiol-cleaving catecholic dioxygenase. J. Mol. Biol. 321621-636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schmidt, A., U. Bahr, and M. Karas. 2001. Influence of pressure in the first pumping stage on analyte desolvation and fragmentation in nano-ESI MS. Anal. Chem. 736040-6046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schmidt, S., and G. W. Kirby. 2001. Dioxygenative cleavage of C-methylated hydroquinones and 2,6-dichlorohydroquinone by Pseudomonas sp. HH35. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 156883-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shevchenko, A., M. Wilm, O. Vorm, and M. Mann. 1996. Mass spectrometric sequencing of proteins from silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Chem. 68850-858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sobott, F., H. Hernandez, M. G. McCammon, M. A. Tito, and C. V. Robinson. 2002. A tandem mass spectrometer for improved transmission and analysis of large macromolecular assemblies. Anal. Chem. 741402-1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Spain, J. C., and D. T. Gibson. 1991. Pathway for biodegradation of p-nitrophenol in a Moraxella sp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57812-819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Steiner, R. A., K. H. Kalk, and B. W. Dijkstra. 2002. Anaerobic enzyme·substrate structures provide insight into the reaction mechanism of the copper-dependent quercetin 2,3-dioxygenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9916625-16630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sugimoto, K., T. Senda, H. Aoshima, E. Masai, M. Fukuda, and Y. Mitsui. 1999. Crystal structure of an aromatic ring opening dioxygenase LigAB, a protocatechuate 4,5-dioxygenase, under aerobic conditions. Structure 7953-965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sze, I. S., and S. Dagley. 1984. Properties of salicylate hydroxylase and hydroxyquinol 1,2-dioxygenase purified from Trichosporon cutaneum. J. Bacteriol. 159353-359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tahallah, N., M. Pinkse, C. S. Maier, and A. J. Heck. 2001. The effect of the source pressure on the abundance of ions of noncovalent protein assemblies in an electrospray ionization orthogonal time-of-flight instrument. Rapid. Commun. Mass Spectrom. 15596-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Takenaka, S., S. Murakami, R. Shinke, K. Hatakeyama, H. Yukawa, and K. Aoki. 1997. Novel genes encoding 2-aminophenol 1,6-dioxygenase from Pseudomonas species AP-3 growing on 2-aminophenol and catalytic properties of the purified enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 27214727-14732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 224673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Titus, G. P., H. A. Mueller, J. Burgner, S. Rodriguez De Cordoba, M. A. Penalva, and D. E. Timm. 2000. Crystal structure of human homogentisate dioxygenase. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7542-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tropel, D., C. Meyer, J. Armengaud, and Y. Jouanneau. 2002. Ferredoxin-mediated reactivation of the chlorocatechol 2,3-dioxygenase from Pseudomonas putida GJ31. Arch. Microbiol. 177345-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.van Baal, I., H. Malda, S. A. Synowsky, J. L. van Dongen, T. M. Hackeng, M. Merkx, and E. W. Meijer. 2005. Multivalent peptide and protein dendrimers using native chemical ligation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 445052-5057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.van Berkel, W. J. H., A. H. Westphal, K. Eschrich, M. H. M. Eppink, and A. de Kok. 1992. Substitution of Arg214 at the substrate-binding site of p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase from Pseudomonas fluorescens. Eur. J. Biochem. 210411-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.van den Heuvel, R. H., E. van Duijn, H. Mazon, S. A. Synowsky, K. Lorenzen, C. Versluis, S. J. Brouns, D. Langridge, J. van der Oost, J. Hoyes, and A. J. Heck. 2006. Improving the performance of a quadrupole time-of-flight instrument for macromolecular mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 787473-7483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vetting, M. W., L. P. Wackett, L. Que, Jr., J. D. Lipscomb, and D. H. Ohlendorf. 2004. Crystallographic comparison of manganese- and iron-dependent homoprotocatechuate 2,3-dioxygenases. J. Bacteriol. 1861945-1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Weber, K., and M. Osborn. 1969. The reliability of molecular weight determinations by dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. J. Biol. Chem. 2444406-4412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Westphal, A. H., and A. de Kok. 1988. Lipoamide dehydrogenase from Azotobacter vinelandii. Molecular cloning, organization and sequence analysis of the gene. Eur. J. Biochem. 172299-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Whiting, A. K., Y. R. Boldt, M. P. Hendrich, L. P. Wackett, and L. Que, Jr. 1996. Manganese(II)-dependent extradiol-cleaving catechol dioxygenase from Arthrobacter globiformis CM-2. Biochemistry 35160-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wolgel, S. A., J. E. Dege, P. E. Perkins-Olson, C. H. Jaurez-Garcia, R. L. Crawford, E. Munck, and J. D. Lipscomb. 1993. Purification and characterization of protocatechuate 2,3-dioxygenase from Bacillus macerans: a new extradiol catecholic dioxygenase. J. Bacteriol. 1754414-4426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Xu, L., K. Resing, S. L. Lawson, P. C. Babbitt, and S. D. Copley. 1999. Evidence that pcpA encodes 2,6-dichlorohydroquinone dioxygenase, the ring cleavage enzyme required for pentachlorophenol degradation in Sphingomonas chlorophenolica strain ATCC 39723. Biochemistry 387659-7669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Xun, L., J. Bohuslavek, and M. Cai. 1999. Characterization of 2,6-dichloro-p-hydroquinone 1,2-dioxygenase (PcpA) of Sphingomonas chlorophenolica ATCC 39723. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 266322-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zylstra, G. J., S.-W. Bang, L. M. Newman, and L. L. Perry. 2000. Microbial degradation of mononitrophenols and mononitrobenzoates, p. 145-160. In J. C. Spain, J. B. Hughes, and H.-J. Knackmuss (ed.), Biodegradation of nitroaromatic compounds and explosives. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.