Abstract

Cyclic dimeric GMP (c-di-GMP) is an important biofilm regulator that allosterically activates enzymes of exopolysaccharide biosynthesis. Proteobacterial genomes usually encode multiple GGDEF domain-containing diguanylate cyclases responsible for c-di-GMP synthesis. In contrast, only one conserved GGDEF domain protein, GdpS (for GGDEF domain protein from Staphylococcus), and a second protein with a highly modified GGDEF domain, GdpP, are present in the sequenced staphylococcal genomes. Here, we investigated the role of GdpS in biofilm formation in Staphylococcus epidermidis. Inactivation of gdpS impaired biofilm formation in medium supplemented with NaCl under static and flow-cell conditions, whereas gdpS overexpression complemented the mutation and enhanced wild-type biofilm development. GdpS increased production of the icaADBC-encoded exopolysaccharide, poly-N-acetyl-glucosamine, by elevating icaADBC mRNA levels. Unexpectedly, c-di-GMP synthesis was found to be irrelevant for the ability of GdpS to elevate icaADBC expression. Mutagenesis of the GGEEF motif essential for diguanylate cyclase activity did not impair GdpS, and the N-terminal fragment of GdpS lacking the GGDEF domain partially complemented the gdpS mutation. Furthermore, heterologous diguanylate cyclases expressed in trans failed to complement the gdpS mutation, and the purified GGDEF domain from GdpS possessed no diguanylate cyclase activity in vitro. The gdpS gene from Staphylococcus aureus exhibited similar characteristics to its S. epidermidis ortholog, suggesting that the GdpS-mediated signal transduction is conserved in staphylococci. Therefore, GdpS affects biofilm formation through a novel c-di-GMP-independent mechanism involving increased icaADBC mRNA levels and exopolysaccharide biosynthesis. Our data raise the possibility that staphylococci cannot synthesize c-di-GMP and have only remnants of a c-di-GMP signaling pathway.

Studies in the Proteobacteria have revealed that bis-(3′,5′)-cyclic dimeric GMP (c-di-GMP) plays a key role in biofilm formation (16, 34). Benziman and colleagues first identified c-di-GMP as an allosteric activator of cellulose synthase in Gluconacetobacter xylinus (originally Acetobacter xylinum), which excretes copious amounts of this exopolysaccharide (35). The Benziman group subsequently characterized the G. xylinus enzymes involved in c-di-GMP synthesis (diguanylate cyclases) and hydrolysis (c-di-GMP phosphodiesterases), both of which were found to contain GGDEF and EAL protein domains positioned in tandem (42). Since then, the enzymatic activities of the individual GGDEF and EAL domains have been determined to be diguanylate cyclase (31, 38, 40) and c-di-GMP-specific phosphodiesterase, respectively (9, 31, 38, 39). More recently another protein domain, HD-GYP, has also been shown to possess c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase activity (36). Decreased c-di-GMP levels resulting from mutations in GGDEF domain-encoding genes or overexpression of the EAL/HD-GYP domain-encoding genes have been associated with decreased exopolysaccharide production, impaired biofilm-forming capacity, and higher virulence in several proteobacterial species (17, 40).

Genes encoding GGDEF and EAL/HD-GYP domain proteins are usually either abundant or nonexistent in bacterial genomes (16). Using representatives of distant branches of the bacterial phylogenetic tree, Ryjenkov et al. (38) have experimentally demonstrated that randomly selected GGDEF domain proteins encoded in the genomes with multiple GGDEF domain genes possess diguanylate cyclase activities. However, to date no GGDEF proteins from low-GC-content Firmicutes (gram-positive bacteria) bacteria have been tested, and nothing is currently known about c-di-GMP-dependent regulatory pathways in this branch of bacteria. We were intrigued by the fact that the sequenced genomes of some representatives of low-GC-content Firmicutes, e.g., Staphylococcus, encode only one conserved GGDEF domain protein and a second protein with a modified GGDEF domain, which may not be catalytically active. Further, the staphylococcal genomes encode neither EAL or HD-GYP domain proteins encoding c-di-GMP phosphodiesterases nor PilZ domain proteins (1), which function as c-di-GMP receptors (8, 32, 33, 37). These observations suggest that staphylococci contain yet uncharacterized c-di-GMP phosphodiesterases and receptors or that the staphylococcal GGDEF proteins are not involved in c-di-GMP synthesis. In this study we explored the activity and function of the conserved GGDEF domain protein, which we designated GdpS (for GGDEF domain protein from Staphylococcus).

Biofilms formed by these Staphylococcus species are an important virulence determinant, particularly in the context of device-related infections. Biofilm-associated infections are recalcitrant to antimicrobial therapy and often require surgical intervention to treat infected tissues and/or remove colonized implants. In a number of Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus aureus strains, impaired production of the exopolysaccharide termed polysaccharide intercellular adhesin (PIA) or polymeric N-acetyl-glucosamine (PNAG) results in a biofilm-negative phenotype (13, 19). The synthesis of PIA/PNAG is encoded by the icaADBC operon. Among S. epidermidis clinical isolates, carriage of the ica locus strongly correlates with biofilm-forming capacity, whereas both ica-dependent and ica-independent biofilm mechanisms operate in S. aureus (reviewed in reference 29).

Here, we report that, similar to its counterparts in the Proteobacteria, the GGDEF domain protein, GdpS, from S. epidermidis and S. aureus influences biofilm development via production of the icaADBC-encoded biofilm exopolysaccharide. However, our data suggest that GdpS controls biofilm development via a c-di-GMP-independent mechanism in which the GGDEF domain is not essential.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, media, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are shown in Table 1. Staphylococcal strains were grown at 37°C on brain-heart infusion (BHI) broth (Oxoid) supplemented when required with chloramphenicol (Cm; 10 μg/ml), erythromycin (Em; 10 μg/ml), and tetracycline (Tc; 5 μg/ml). BHI broth was supplemented where indicated with 4% NaCl.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus strains | ||

| S. aureus RN4220 | Restriction-deficient derivative of 8325-4 | 25 |

| S. epidermidis CSF41498 | Biofilm-positive, cerebrospinal fluid S. epidermidis isolate (Beaumont Hospital, Dublin) | 10 |

| GDPS1 | CSF41498 derivative; gdpS::ermB | This study |

| RSBV1 | CSF41498 derivative; rsbV::Tcr | This study |

| CSF-2 | CSF41498 derivative; biofilm-negative; icaC::IS256Δtnp | W. Ziebuhr |

| E. coli strains | ||

| TOPO | recA1 endA1 lac [F′ proAB lacIq Tn10 (Tetr)] | Invitrogen |

| DH5α | λ− φ80lacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 recA1 endA1 hsdR17(rK− mK−) supE44 thi-1 gyrA relA1 | Invitrogen |

| BL21(DE3) | F−ompT hsdSB(rB− mB−) gal dcm (DE3) | Invitrogen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pEC5 | pBluescript KS+ derivative; source of ermB gene (Emr); Apr | 6 |

| pBT2 | Temperature-sensitive E. coli-Staphylococcus shuttle vector; Apr (E. coli) Cmr (Staphylococcus) | 6 |

| pMAD | Shuttle vector for allele replacement; Apr (E. coli) Emr (Staphylococcus); contains a bgaB gene encoding a thermostable β-galactosidase | 3 |

| pBT2::bga | 2,803-bp SmaI-SwaI fragment containing the bgaB gene from pMAD cloned into the SmaI site of pBT2 | This study |

| pBlue::tet | pBluescript containing the tetA gene from pT181 on a 2,236-bp HindIII fragment | This study |

| pSEGP1 | 1,594-bp PCR product containing the gdpS gene amplified from CSF41498 using primers SEgmp1 and SEgmp2 in pCR-Blunt II-TOPO (Invitrogen) | This study |

| pSEGP2 | 1,227-bp EcoRI-ClaI (blunted) fragment containing the ermB from pEC5 cloned into the BsgI site (blunted) of pSEGP1 | This study |

| pSEGP3 | 2,821-bp fragment containing gdpS::ermB cloned from pSEGP2 into the BamHI-XbaI sites of pBT2 | This study |

| pSEGP5 | EcoRI fragment from pSEGP1 containing the full-length S. epidermidis gdpS gene cloned into pLI50 | This study |

| pSEGP6 | 922-bp PCR product containing the 5′ end of gdpS (encoding the membrane spanning region) amplified from CSF41498 using primers SEgmp1 and SDMSTOP2 in pCR-Blunt II-TOPO | This study |

| pSEGP7 | EcoRI fragment from pSEGP1 containing the mutated gdpS (ΔE270 ΔE271) allele cloned into pLI50 | This study |

| pSEGP8 | BamHI-XbaI fragment containing the 5′ end of the gdpS gene from pSEGP6 cloned into pLI50 | This study |

| pSESB1 | 1,540-bp PCR product containing the S. epidermidis rsbV gene amplified using primers SEsigB1 and SEsigB2 and cloned into pCR-Blunt II-TOPO | This study |

| pSESB2 | 2,236-bp SwaI-SmaI fragment containing the tetA gene from pBlue::tet cloned into the StuI site of pSESB1 | This study |

| pSESB3 | 4,040-bp BamHI-XbaI fragment containing rsbV::Tcr cloned into BamHI-NheI site of pBT2::bga | This study |

| pSESB5 | 3,979-bp PCR fragment containing the sigB locus amplified using SigB1 and SigB2 and cloned into pCR-Blunt II-TOPO | This study |

| pSESB6 | 3,979-bp PCR fragment containing the sigB locus amplified using SigB1 and SigB2 and cloned into pCR-Blunt II-TOPO BamHI-XbaI fragment containing the sigB locus cloned from pSESB5 into pLI50 | This study |

| pSAGP1 | 1,442-bp PCR product containing the S. aureus 8324-5 gdpS gene amplified using primers SAgmp1 and SAgmp2 and cloned into pCR-Blunt II-TOPO | This study |

| pSAGP2 | EcoRI fragment containing the S. aureus gdpS gene from pSAGP1 cloned into pLI50 | This study |

| pMSA0701 | pMAL-c2x (NEB) expressing the full-length S. aureus gdpS | This study |

| pMSA12 | pMAL-c2x expressin S. aureus gdpS GGDEF domain | This study |

| pMSE3 | pMAL-c2x expressing S. epidermidis gdpS GGDEF domain | This study |

| pCN51 | E. coli-Staphylococcus shuttle vector; Emr (ermR) Apr | 7 |

| pCN38 | E. coli-Staphylococcus shuttle vector; Cmr (cat194) Apr | 7 |

| pCN51cat | pCN51 where ermR is replaced with cat194 from pCN38 | This study |

| pCN51cat:gdpS | pCN51cat expressing S. epidermidis gdpS | This study |

| pCN51cat::yeaP | pCN51cat expressing E. coli yeaP | This study |

| pCN51cat::Syn | pCN51cat expressing Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803 | This study |

Primary attachment assay on polystyrene.

Primary attachment assays were performed based on the method of Lim et al. (27). Briefly, an overnight culture grown at 37°C in BHI or BHI-NaCl broth was diluted in BHI broth to approximately 300 CFU/100 μl. Bacterial concentrations were determined by bacterial plate counts run in parallel to the attachment assay. Aliquots (100 μl) of the adjusted suspension were spread on empty Nunclon tissue culture-treated (ΔSurface) petri dishes. Tissue culture-treated polystyrene petri dishes have a more negatively charged surface than untreated polystyrene and promote cell attachment. After incubation at 37°C for 30 min, the petri dishes were rinsed gently three times with 5 ml of sterile phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.5) and covered with 15 ml of molten 0.8% tryptic soy agar maintained at 48°C. Primary attachment was expressed as a percentage of the number of CFU attached to the base of the petri dishes after washing compared to the total number of CFU. Each experiment was repeated three times.

Biofilm assays.

Semiquantitative measurements of biofilm formation under static conditions were determined using Nunclon tissue culture-treated (ΔSurface) 96-well polystyrene plates (Nunc, Denmark), as described previously (10). Each strain was tested at least three times, and average results are presented. A biofilm-positive phenotype was defined as an A492 of ≥0.17.

Biofilm formation under flow conditions was examined using Biosurface Technologies FC93 flow cells (Bozeman, MT) containing BHI-NaCl medium at a flow rate of 500 μl/min. Overnight cultures were adjusted to an A600 of 1.0 prior to inoculation, and the bacteria were allowed to adhere to the flow cells for 120 min before the flow was turned on and the biofilms were allowed to mature for 24 h.

PIA/PNAG assays.

PIA/PNAG assays were performed as described elsewhere (21). Briefly, 5-ml overnight cultures (approximately 5 × 109 bacteria) were collected by centrifugation, resuspended in 200 to 500 μl of 0.5 M EDTA, and boiled for 5 min. The cell debris was again centrifuged, and the supernatant was treated with 200 μg of proteinase K at 37°C for 1 h. The proteinase K was inactivated by boiling for 5 min, and the samples were diluted as appropriate before being applied onto nitrocellulose (prewetted in Tris-buffered saline [TBS]) using a vacuum blotter. The blots were dried, rewet in TBS, and blocked for 1 h in 1% bovine serum albumin. The primary antibody (1:5,000 dilution of rabbit anti-PIA/PNAG [a kind gift from Tomas Maira Litran and Gerald Pier] in TBS-Tween-0.1% bovine serum albumin) was then applied to the membrane for 1 h. Horseradish peroxidase-linked anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G secondary antibody (1:5,000 dilution in TBS-Tween-0.1% skim milk) was then incubated with the membrane for 1 h. A chemiluminescence kit (Amersham) was used to generate light via the horseradish peroxidase-catalyzed breakdown of lumina and detected using a Bio-Rad Fluor-S Max charge-coupled-device camera system.

Construction of S. epidermidis gdpS::Emr mutant.

The gdpS::Emr mutant strain GDPS1 was constructed using the following procedure. A 1,594-bp fragment containing the gdpS gene from S. epidermidis CSF41498 was amplified by PCR using the primers SEgmp1 and SEgmp2 (Table 2) and cloned into the pCR-Blunt II-TOPO plasmid (Invitrogen) to create pSEGP1. To construct a gdpS mutant allele, a 1,227-bp EcoRI-ClaI fragment from pEC5 (6), which contains the ermB gene, was blunt-ended and cloned into blunt-ended, BsgI-digested pSEGP1. In the resulting plasmid, pSEGP2, the gdpS gene is disrupted by the ermB gene inserted 401 bp downstream of the gdpS start codon. In order to facilitate delivery of the gdpS::ermB allele onto the chromosome of S. epidermidis, a 2,821-bp BamHI-XbaI fragment from pSEGP2 was subcloned into the temperature-sensitive Escherichia coli-Staphylococcus shuttle vector pBT2 (6) that had also been digested with BamHI and XbaI. The resulting plasmid, pSEGP3, was electroporated into S. aureus RN4220 and S. epidermidis CSF41498. Cmr colonies were identified on BHI agar (0.5 M sucrose) plates. Allele replacement of the temperature-sensitive pSEGP3 in CSF41498 was achieved following two rounds of growth at 42°C for 24 h without antibiotic selection and subsequent selection of Emr colonies on BHI agar plates. Replica plating was then used to identify Emr Cms colonies. The presence of the gdpS::Emr allele on the chromosome was confirmed by PCR (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this study

| Target gene (use) | Primer name | Primer sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| gyrB (RT-PCR) | GYRB1 | TTATGGTGCTGGACAGATACA |

| GYRB2 | CACCGTGAAGACCGCCAGATA | |

| 16S rRNA (RT-PCR) | 16Sfor | CATTTCACCGCTACACATGG |

| 16SRev | GAAAGCCACGGCTAACTACG | |

| icaA (RT-PCR) | KCA1 | AACAAGTTGAAGGCATCTCC |

| KCA2 | GATGCTTGTTTGATTCCCT | |

| icaR (RT-PCR) | icaRFor2 | ATCCAAAGCGATGTGCGTAG |

| icaRRev2 | TCCATTGACGGACTTTACCAG | |

| sarA (RT-PCR) | SarAFor | TCAGCTTTGAAGAATTTGCAG |

| SarARev | TCTTTCATCGTGTTCATTACGTTT | |

| asp23 (RT-PCR) | Asp23For | CATGAAAGGTGGCTTCACAG |

| Asp23Rev | CATTACGTCGTCAACTTGCAT | |

| luxS (RT-PCR) | SEluxSFor | TTCGTTTCAAACAGCCCAAT |

| SEluxRev | CTGGGACTTCGCTAGCATTT | |

| gdpS (RT-PCR) | SEdgcSFor | ATCTGTCATGGTGGCAGGTA |

| SEdgcSRev | CGATAAAAGCAGCCGTGAGT | |

| tcaR (RT-PCR) | SetcaRFor | TGGCATATCAGCTGAGCAAT |

| SEtcaRRev | TGGCTCATAATCGCTTTTCTC | |

| S. epidermidis gdpS | SEgmp1 | TGAATAAGTTGTACCTCACGCTATG |

| SEgmp2 | TCTCATCACCTCCGAAGCTA | |

| S. aureus gdpS | SAgmp1 | TGGTGTTATCGTCAAACTGACA |

| SAgmp2 | AACCTCCACTTAACTATACGG | |

| gdpS (ΔE270 and ΔE271 mutagenesis) | SEdgcSdel_1 | TTTAGAAACGGTGGCTTTTCTGTTGTAATA |

| SEdgcSdel_2 | TATTACAACAGAAAAGCCACCGTTTCTAAA | |

| S. epidermidis gdpS GGDEF domain | SE0528F | GCTCTAGATCAGCAATAACATTCGTTG |

| SE0528R | CCGAAGCTTTTATAATTTGACAATAGGATT | |

| gdpS transmembrane domain only | SEgmp1 | TGAATAAGTTGTACCTCACGCTATG |

| SESDM-STOP2 | TACCTAGACCTGTAAGTCAATCGTATTTATCTT | |

| S. epidermidis rsbV | SEsigB1 | TCTTGAGCTTGGCTATCTTCG |

| SEsigB2 | CGTTTGAACCGTGTTGTTGA | |

| S.epidermidis sigB locus | SEsigBoperon1 | TCACCAGTTCAAGGGTCTGA |

| SEsigBoperon2 | TCTTTGGAGCTTCGTCTGTG | |

| S. epidermidis gdpS GGDEF domain | SE0528F | GCTCTAGATCAGCAATAACATTCGTTG |

| SE0528R | CCGAAGCTTTTATAATTTGACAATAGGATT | |

| S. aureus gdpS GGDEF domain | SA0701F | GCTCTAGATCAGCGATAACATTTGTCG |

| SA0701R | CCGAAGCTTTTATAAATTGATAATAGGG | |

| S. aureus gdpS (full-length) | SA0701FL | GCTCTAGATTCGAAGCATTTATATACAAT |

| SA0701R | CCGAAGCTTTTATAAATTGATAATAGGG | |

| S. epidermidis gdpS (ORF only) | CN-SE0528F | CCTATGCATTTGAAGCTATCATATATAAC |

| CN-SE0528R | CGGGATCCTAGCTTGATTATAATTTGAC | |

| Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803 slr1143 | CN-1143F | CCAATGCATCAGCTAAATTACCGC |

| CN-1143R | CGGGATCCTTATTCTGCCAGTTG | |

| E. coli yeaP | CN-YeaPF | CCAATGCATCGCACTATTTTTATTACATTC |

| CN-YeaPR | CGGGATCCTCAGGAATGTAGCGC |

Construction of S. epidermidis rsbV::Tcr mutant.

The rsbV mutant strain RSBV1 was constructed using the following procedure. A 1,540-bp fragment containing the rsbV gene was amplified by PCR using Phusion high-fidelity DNA polymerase (NEB) from CSF41498 using the primers SEsigB1 and SEsigB2 (Table 2) and cloned into the pCR-Blunt II-TOPO plasmid (Invitrogen) to create pSESB1. The Tcr gene from plasmid pT181 was digested with HindIII on a 2,236-bp fragment, which was subcloned into pBluescript (Stratagene) to create pBlue-tet. The Tcr gene was subsequently subcloned from pBlue-tet on a SwaI-SmaI fragment and ligated into the StuI site in the rsbV gene of pSESB1 to create pSESB2. A 4,040-bp BamHI-XbaI fragment containing the rsbV::Tcr allele from pSESB2 was ligated into pBT2-bga digested with BamHI-NheI to create pSESB3. The plasmid pBT2-bga contains the bgaB gene from pMad (3) cloned on a 2,803-bp SmaI-SwaI fragment into the SmaI site of pBT2. The bgaB gene encodes a thermostable β-galactosidase that can be exploited in blue/white selection during allele replacement mutagenesis. The pSESB3 plasmid was electroporated into RN4220 and CSF41498.

Allele replacement of the temperature-sensitive pSESB3 in CSF41498 was achieved by growth at 30°C in the presence of Cm and Tc followed by repeated growth (three subcultures) at 42°C without antibiotic selection and selection of Tcr colonies on BHI agar plates. Bluo-Gal (200 μg/ml) (Invitrogen) was also included in the medium to facilitate blue/white screening. White, Tcr colonies were then screened for sensitivity to Cm to confirm plasmid loss, and PCR analysis was used to verify the presence of the rsbV::Tcr allele on the chromosome.

DNA constructs.

Plasmid pSEGP5 used in complementation assays was made as follows. From pSEGP1 an EcoRI fragment containing the gdpS gene was cloned into pLI50. A fragment containing the 5′ end of gdpS (encoding the membrane-spanning region only) was amplified from CSF41498 genomic DNA on a 922-bp PCR product using primers SEgmp1 and SDMSTOP2 (Table 2) and cloned into pCR-Blunt II-TOPO (pSEGP6) and ultimately into pLI50 to create pSEGP8.

To complement the rsbV mutation, the entire sigB locus (rsbUVWsigB) was amplified on a 3,979-bp fragment using the primers SEsigBoperon1 and SEsigBoperon2 (Table 2) and cloned into pCR-Blunt II-TOPO to create pSESB5. From pSESB5 a BamHI-XbaI fragment containing the sigB locus was cloned in pLI50 to create pSESB6.

Plasmids expressing heterologous diguanylate cyclases were made as follows. pCN51cat plasmid was generated from pCN51 (7) by replacing ermR (Emr) with cat194 (Cmr) from pCN38 (7) using XhoI and ApaI restriction sites. PCR fragments containing S. epidermidis gdpS, E. coli yeaP, and the Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803 slr1143 gene were PCR-amplified from the genomic DNA of host bacteria using the corresponding primers listed in Table 2. The PCR fragments were gel purified, digested with NsiI and BamHI restriction enzymes, and cloned under the Pcad promoter into pCN51cat, which had been digested with PstI and BamHI.

For GdpS overexpression, we PCR amplified the genomic regions encoding the GGDEF domains of the gdpS genes from S. epidermidis and S. aureus and the full-length S. aureus gene using the primers listed in Table 2. PCR fragments were subsequently gel purified, digested with XbaI and HindIII, and cloned into pMAL-c2x (New England Biolabs). The resulting plasmids, pMSE3 (S. epidermidis GdpS GGDEF domain), pMSA12 (S. aureus GdpS GGDEF domain), and pMSA0701 (S. aureus full-length GdpS) expressed proteins of interest as C-terminal fusions to maltose binding protein (MBP).

gdpS mutagenesis.

Oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis (Quikchange; Stratagene) was employed to mutate the conserved GGEEF motif of the GdpS protein. The plasmid pSEGP1 was used as a template for the reactions. The complementary oligonucleotides (Table 2) used to construct a GAAGAA deletion mutation (GGEEF to GGF) were SEdgcSdel_1 and SEdgcSdel_2. After mutagenesis the DNA sequence of the gdpS gene was determined to verify the presence of the desired mutations. The mutated gdpS gene was subcloned into pLI50 to create pSEGP7 (gdpS allele with GGF motif).

Protein purification and diguanylate cyclase assays.

Plasmids overexpressing the MBP fusion proteins were maintained in E. coli DH5α. Protein purification was performed using amylose resin according to the manufacturer's instructions (pMAL expression system; New England Biolabs) and essentially as described previously (37). To increase solubility of the S. aureus MBP-GdpS fusion, 0.2 mM n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (Sigma) was added in all buffers, and protein purification to homogeneity was not pursued to avoid loss of enzymatic activity. Proteins were analyzed using a Protein 200 Plus LabChip kit (Agilent Technologies). All enzymatic assays were performed at 30°C. The standard reaction mixture contained from 4 μM (MBP-GdpS from S. aureus) to 35 μM (S. aureus and S. epidermidis GdpS GGDEF domains) protein in a reaction buffer with the following composition: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8), 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, and 10% glycerol. The reaction was started by the addition of 200 μM (final concentration) GTP (Sigma). Aliquots (100 μl) were withdrawn at different time points, boiled for 5 min, and centrifuged for 5 min at 16,000 × g. The supernatants were then filtered through a 0.22-μm-pore-size filter and subjected to separation using high-pressure liquid chromatography on a Summit HPLC (Dionex) system as described earlier (37).

RNA purification and analysis.

RNA purification was performed as described previously (10, 12), and the concentration was determined using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer. Real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) was performed on a LightCycler instrument using the RNA amplification kit Sybr Green I (Roche Biochemicals, Switzerland) following the manufacturer's recommended protocol (10, 12). For LightCycler RT-PCRs, RT was performed at 61°C for 20 min, followed by a denaturation step at 95°C for 30 s and 35 amplification cycles of 95°C for 2 s, 50°C for 5 s, and 72°C for 8 s. Melting curve analysis was performed at 45°C to 95°C (temperature transition, 0.1°C per s) with stepwise fluorescence detection. Conventional RT-PCR was performed using a OneStep RT-PCR kit (Qiagen, United Kingdom) as described previously (10, 12). RT was performed at 55°C for 30 min, followed by 12 to 26 amplification cycles of 94°C for 20 s, 50°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 20 s. To analyze icaADBC mRNA, stability cultures were grown to an A600 of 2.0, and rifampin was added to a final concentration of 200 μg/ml to stop transcription initiation. Samples (1 ml) were removed at time points 0, 4, 8, and 15 min and resuspended in RNAlater (Ambion) to preserve RNA integrity, followed by RNA purification.

All conventional RT-PCRs were optimized to ensure that amplification was terminated in the linear range, and densitometry on electrophoresed PCR products was performed using image analysis software to compare relative expression between samples. For LightCycler RT-PCR, RelQuant software (Roche Biochemicals) was used to measure relative expression of target genes. The gyrB or 16S rRNA genes were used as internal standards in all RT-PCR experiments. Each experiment in this study was performed at least three times, and average data with standard deviations are presented. The primers used in RT-PCR experiments are listed in Table 2.

RESULTS

Bioinformatics analysis of the putative c-di-GMP signaling system in staphylococci.

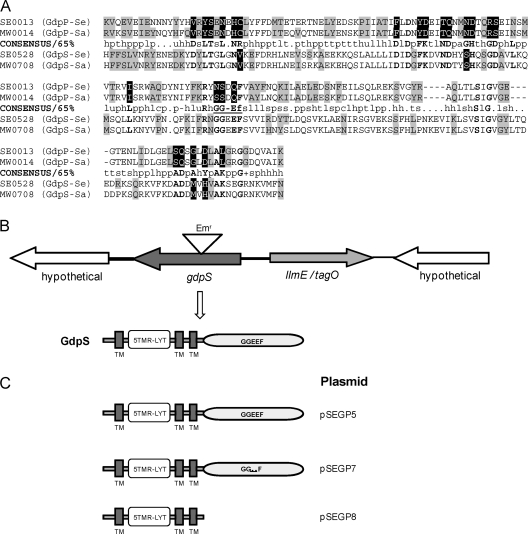

In contrast to most proteobacterial genomes containing numerous GGDEF domain proteins encoding diguanylate cyclases, the sequenced genomes of Staphylococcus encode only one protein with a conserved GGDEF domain, designated GdpS (SE0528 in S. epidermidis RP62A and MW0708 in S. aureus MW2). The N terminus of staphylococcal GdpS contains several membrane-spanning regions, five of which form a 5TMR-LYT domain (Pfam07694) (14) (Fig. 1C). The 5TMR-LYT domain represents the transmembrane region of LytS, the membrane bound sensor for the LytS/LytT two-component regulatory system involved in the regulation of cell wall metabolism (2). The amino acid sequences of the GGDEF domains contain intact GGD/EEF motifs involved in substrate, GTP, binding, and coordination of the Mg2+ ions required for enzymatic activity (Fig. 1A). They also contain most other residues involved in GTP binding, which were identified in the crystal structure of the activated diguanylate cyclase PleD from Caulobacter crescentus (47). However, outside the GTP-binding pocket we found several nonhomologous substitutions between the GdpS GGDEF domains and the invariable residues of the GGDEF domain consensus sequence. Numerous less conserved residues were also different between GdpS and the consensus (Fig. 1A). Therefore, from the sequence analysis, we can predict that the GdpS proteins would bind GTP, but it is unclear whether they would possess diguanylate cyclases activity.

FIG. 1.

(A) Alignment of the GGDEF (DUF1) domains from the GdpS and GdpP proteins from S. epidermidis and S. aureus with a consensus (65%) sequence derived from >8,000 GGDEF domains (SMART database). The most conserved residues are capitalized and bolded; the deviations from the invariable residues of the consensus are shown in white on the black background; the deviations from less conserved consensus residues are shown on a gray background. Abbreviations used in the consensus line: •, any; l, aliphatic (I, L, or V); a, aromatic (F, H, W, or Y); c, charged (D, E, H, K, or R); h, hydrophobic (A, C, F, G, H, I, K, L, M, R, T, V, W, or Y); −, negative (D or E); p, polar (C, D, E, H, K, N, Q, R, S, or T); +, positive (H, K, or R); s, small (A, C, D, G, N, P, S, T, or V); u, tiny (A, G, or S); t, turn-like (A, C, D, E, G, H, K, N, Q, R, S, or T). (B) Chromosomal organization of the gdpS (SE0528) and adjacent genes in S. epidermidis. Allele replacement was used to construct a gdpS::Emr mutant in which the gdpS gene is disrupted by the ermB gene inserted at a BsgI restriction enzyme site 401 bp from the start codon. (C) Predicted domain organization of the GdpS protein and its mutant derivatives. TM, predicted transmembrane domain; 5TMR-LYT, conserved transmembrane domain of the LytS-YhcK type.

The GGDEF domain of the second staphylococcal GGDEF protein, designated GdpP, where P stands for phosphoesterase (SE0013 in S. epidermidis RP62A and MW0014 in S. aureus MW2), is highly modified (Fig. 1A). It may not possess diguanylate cyclase activity because it lacks residues essential for catalysis (47). Interestingly, the domains downstream of the modified GGDEF, i.e., DHH (Pfam01368) and DHHA1 (Pfam02272), are predicted to encode phosphoesterase activity. It is therefore conceivable, albeit highly speculative, that GdpP may function as a novel type of c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase. It is noteworthy that the staphylococcal genomes do not encode either EAL or HD-GYP domain proteins encoding known c-di-GMP phosphodiesterases or PilZ domain proteins, which function as c-di-GMP receptors.

Our bioinformatics analysis suggests one of two possibilities: (i) staphylococci possess a modified version of the c-di-GMP signaling pathway, in which GdpS functions as a diguanylate cyclase, GdpP functions as a c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase, and c-di-GMP targets are unknown, non-PilZ proteins; or (ii) staphylococci contain remnants of the c-di-GMP signaling pathway, whose proteins, GdpS and GdpP, are no longer involved in c-di-GMP metabolism. Below, we explore the in vivo and in vitro activities of the conserved GGDEF domain protein GdpS, which is critical for distinguishing between these two possibilities.

The S. epidermidis GGDEF domain protein GdpS is involved in biofilm regulation.

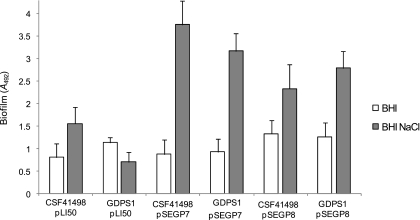

We chose the cerebrospinal fluid isolate S. epidermidis CSF41498 as a model to investigate the function of the GdpS protein because this strain forms robust, exopolysaccharide-mediated biofilms (20) and is amenable to genetic manipulation (10). We replaced the chromosomal gdpS gene, SE0528, from S. epidermidis CSF41498 with a gdpS::Emr allele as described in Materials and Methods. Using static 96-well plate assays, the biofilm-forming capacity of the gdpS mutant, named GDPS1, was found to be similar to that of the wild type when grown in BHI medium (Fig. 2A). However, the GDPS1 mutant formed approximately 50% less biofilm than CSF41498 when grown in BHI-NaCl medium (Fig. 2A). We determined that diminished biofilm-forming capacity by GDPS1 in BHI-NaCl medium was not due to an altered growth rate or a defect in primary cell attachment to Nunclon ΔSurface polystyrene (data not shown), suggesting that the gdpS inactivation interferes with biofilm maturation and not initial interactions between the bacterial cell and the surface.

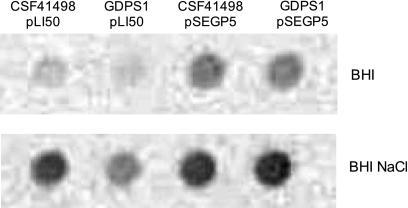

FIG. 2.

Contribution of the gdpS gene to biofilm development in S. epidermidis CSF41498. (A) Biofilm phenotypes of S. epidermidis CSF41498 and GDPS1 (gdpS::Emr) strains complemented with pLI50 (control) or pSEGP5 (S. epidermidis gdpS) in static 96-well plate assays. Strains were grown overnight at 37°C in BHI broth and BHI-NaCl broth supplemented. Biofilm formation was measured at least three times, and standard deviations are indicated. (B) Biofilm development by S. epidermidis CSF41498 pLI50, CSF41498 pSEGP5 (gdpS), GDPS1 (gdpS::Emr) pLI50, and GDPS1 pSEGP5 (gdpS) strains using the Biosurface Technologies flow system. Strains were grown for 24 h at 37°C in BHI-NaCl broth, and the flow cells were photographed after 24 h. 41498, CSF41498.

Biofilm development was also analyzed under flow conditions. Bacteria were grown in Biosurface Technologies FC93 flow cells (Bozeman, MT) containing BHI-NaCl medium. Consistent with the static biofilm assays, the gdpS mutation impaired biofilm formation after 24 h of growth in the flow cells (Fig. 2B).

In order to determine if the biofilm defect of GDPS1 could be complemented, the intact gdpS gene from CSF41498 was cloned into the E. coli-Staphylococcus shuttle vector pLI50, plasmid pSEGP5, and electroporated into CSF4148 and GDPS1. The presence of pSEGP5 in GDPS1 (over)compensated for the biofilm impairment of the gdpS mutant in both static and flow cell environments. Furthermore, carriage of pSEGP5 greatly enhanced biofilm production in CSF41498 (Fig. 2A and B). The knockout and overexpression experiments reveal GdpS as a novel biofilm regulator in S. epidermidis.

GdpS activates PIA/PNAG synthesis in S. epidermidis CSF41498 via activation of icaADBC operon expression.

To examine if the reduced biofilm-forming capacity in the GDPS1 mutant was related to altered expression of PIA/PNAG, immunoblotting with PIA/PNAG-specific antibodies was performed to semiquantitatively measure PIA/PNAG levels in CSF41498 and GDPS1 cultures grown in BHI or BHI-NaCl medium. Cell extracts of GDPS1 contained reduced PIA/PNAG levels compared to cell extracts of CSF41498 (Fig. 3). In addition, carriage of pSEGP5 increased PIA/PNAG production in CSF41498, and complementation of GDPS1 with pSEGP5 restored PIA/PNAG to wild-type levels in both BHI and BHI-NaCl media (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Contribution of gdpS to PIA/PNAG levels in S. epidermidis CSF41498 and GDPS1 (gdpS::Emr) complemented with pLI50 (control) and pSEGP5 (gdpS). PIA/PNAG immunoreactivity was measured in cell extracts prepared from overnight cultures grown at 37°C in BHI broth and BHI-NaCl broth.

To investigate whether PIA/PNAG synthesis was the principal or even sole target of GdpS-mediated biofilm regulation, we introduced plasmid pSEGP5 and the control vector pLI50 into S. epidermidis CSF-2, in which the ica operon was inactivated by an IS256Δtnp insertion in icaC (20). As expected, immunoblotting demonstrated that strain CSF-2 harboring empty pLI50 and CSF-2 containing pSEGP5 produced no PIA/PNAG (data not shown). Further, the presence of pSEGP5 did not affect biofilm development in this strain grown in BHI or BHI-NaCl medium (Fig. 4A). These data strongly suggest that GdpS-mediated biofilm development involves activation of the icaADBC-encoded PIA/PNAG.

FIG. 4.

Contribution of the ica operon and σB to gdpS-induced biofilm formation. Biofilm development by S. epidermidis CSF41498 and its isogenic mutants CSF-2 (icaC::IS256Δtnp) and RSBV1 (rsbV::Tcr) complemented with multicopy pLI50 (control) and pSEGP5 (gdpS) plasmids grown at 37°C for 24 h in BHI broth and BHI-NaCl broth. Biofilm assays were carried out in 96-well microtiter plates and conducted at least three times. Standard deviations are indicated.

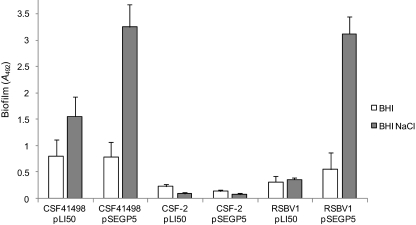

To determine at what level PIA/PNAG synthesis was affected, we investigated the effect of gdpS inactivation and overexpression on ica operon expression using real-time RT-PCR. RNA for these experiments was extracted from cultures grown to an A600 of 2.0 in BHI and BHI-NaCl media. Expression levels of icaA were reduced approximately twofold in GDPS1 compared to CSF41498 in BHI medium and approximately sixfold in BHI-NaCl medium (Fig. 5). The presence of pSEGP5 in GDPS1 resulted in an approximately fourfold increase in icaA expression in BHI medium and an approximately 11-fold increase in BHI-NaCl medium, while the presence of pSEGP5 in CSF41498 resulted in an approximately two- to threefold increase in icaA transcript levels in BHI and BHI-NaCl media (Fig. 5). These findings establish that GdpS influences PIA/PNAG production by controlling ica operon expression.

FIG. 5.

(A) Comparative measurement of icaA transcription by real-time RT-PCR in S. epidermidis CSF41498 and GDPS1 (gdpS::Emr) strains complemented with pLI50 (control) and pSEGP5 (gdpS). Total RNA was extracted from cultures grown at 37°C to an A600 of 2.0 in BHI broth and BHI-NaCl broth. RelQuant software (Roche, Switzerland) was used to measure the relative expression of icaA against the constitutively expressed gyrB gene. icaA transcript levels in all strains grown in BHI and BHI-NaCl media were compared to icaA transcript levels in CSF41498 pLI50 grown in BHI broth, which was assigned a value of 1. The data presented are the average of three separate experiments, and standard deviations are indicated. (B) Comparative measurement of icaA mRNA transcript stability by conventional RT-PCR in S. epidermidis CSF41498 and GDPS1 (gdpS::Emr) strains complemented with pLI50 (control) and pSEGP5 (gdpS). Cultures were grown to an A600 of 2.0, and rifampin was added to a final concentration of 200 μg/ml to terminate transcription initiation. Samples (1 ml) of culture were removed at time points 0, 4, 8, and 15 min and resuspended in RNAlater (Ambion) to ensure maintenance of RNA integrity prior to purification. Equal loading of total RNA in each sample was confirmed by RT-PCR using 16S rRNA as an internal standard before icaA transcript levels were measured.

GdpS does not affect transcript levels of known ica operon regulators.

To gain insights into the mechanism of ica activation by GdpS, we measured the effect of the gdpS mutation or overexpression on the activities of the transcription factors directly involved in icaADBC expression. Our observation that the biofilm defect of the GDPS1 mutant was most prominent in medium supplemented with NaCl prompted us to investigate the role of σB, which is known to be activated by osmotic stress (23, 24). To this end, we first constructed an rsbV::Tcr mutation in CSF41498 as described in Materials and Methods. Consistent with previously described S. epidermidis σB mutants (11, 23, 24), the CSF41498 rsbV::Tcr mutant, RSBV1, displayed a biofilm-negative phenotype in BHI and BHI-NaCl media but could be restored to a biofilm-positive phenotype by the addition of ethanol to the growth medium (data not shown). Importantly, multicopy expression of gdpS in the RSBV1 mutant increased biofilm formation (Fig. 4), strongly suggesting that σB is not required for GdpS-mediated biofilm activation. To further evaluate the effect of GdpS on σB activity, we measured mRNA levels of the σB-dependent gene asp23 (18) using real-time RT-PCR. Consistent with our data showing that σB was not required for gdpS-mediated biofilm formation (Fig. 4), asp23 mRNA levels were not significantly affected by mutation or overexpression of gdpS (data not shown).

IcaR is a key repressor controlling icaADBC operon transcription (10). Our RT-PCR measurements revealed that icaR mRNA levels were unaffected by GdpS (data not shown). IcaR-independent regulation of ica operon expression by several additional regulators has also been reported, including the global regulator SarA (4, 11, 44, 46), the teicoplanin-associated locus regulator TcaR (21), and the LuxS quorum-sensing system (49). We found that the expression levels of sarA, tcaR, and luxS were not significantly affected in the gdpS mutant and overexpressing strains (data not shown).

RT-PCR was used to investigate if GdpS controls the stability of ica operon mRNA in rifampin-treated cultures of CSF41498 (pLI50), CSF41498 (pSEGP5), GDPS1 (pLI50), and GDPS1 (pSEGP5) grown in BHI-NaCl medium (as described in Materials and Methods). The stability of icaADBC transcripts was similar in CSF41498 and GDPS1 (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, overexpression of the gdpS gene was not accompanied by enhanced icaADBC mRNA stability, suggesting that GdpS does not promote PIA/PNAG production by increasing icaADBC mRNA stability (Fig. 5B). Taken together, these results establish that GdpS operates via a new signal transduction cascade or that it regulates activities but not mRNA levels of one of the above-listed icaADBC transcriptional regulators.

Diguanylate cyclase activity is not involved in biofilm regulation.

To investigate whether the observed effects of GdpS on biofilm formation were due to its diguanylate cyclase activity, we attempted to complement the S. epidermidis gdpS mutation with two heterologous diguanylate cyclase genes whose activities have been tested in vitro (38), namely, E. coli yeaP (on plasmid pCN51cat-YeaP) and Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803 slr1143 (on plasmid pCN51cat-Syn). The GC content of these genes is relatively low and comparable to that of staphylococci. To ensure expression in S. epidermidis, yeaP and slr1143 were placed downstream of a strong cadmium-inducible staphylococcal promoter (7). We found that biofilm levels in the GDPS1 mutant containing either pCN51cat-YeaP or pCN51cat-Syn were similar to the levels of GDPS1 control (data not shown). These results suggest that c-di-GMP synthesis was insufficient to complement the gdpS mutation and that, by extension, GdpS may not function as diguanylate cyclase. However, we could not exclude alternative explanations, e.g., inefficient protein levels or improper cellular localization of the heterologous diguanylate cyclases. Therefore, we decided to test the activity of GdpS in vitro.

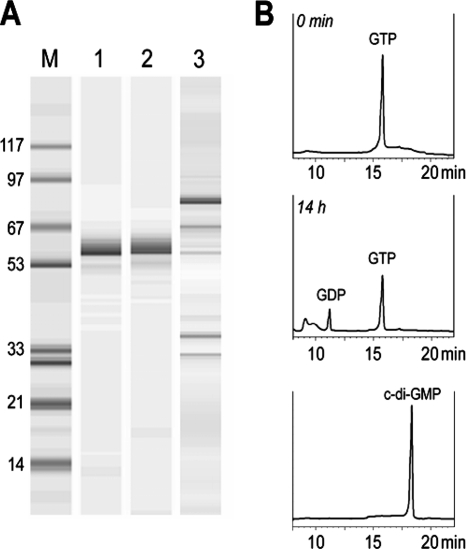

We overexpressed and purified the GGDEF domain from S. epidermidis GdpS in E. coli (as an MBP fusion) (Fig. 6A, lane 1). We chose to test the activity of the GGDEF domain alone as opposed to the full-length protein because we do not know the conditions that may be needed for GdpS activation. Importantly, we have previously demonstrated that GGDEF domains from several unrelated diguanylate cyclases display low-level diguanylate cyclase activity (38). This activity results from spontaneous formation of active GGDEF domain dimers, when high protein concentrations are employed. We detected no c-di-GMP even after prolonged incubation of the highly concentrated (35 μM, final concentration) purified GGDEF domain from GdpS with GTP, which suggests that GdpS is enzymatically inactive. We did, however, detect residual GTPase activity, suggesting that the GGDEF domain of GdpS is capable of GTP binding, which agrees with our bioinformatics analysis (Fig. 6B). Note that the lack of detectable diguanylate cyclase activity in GdpS is consistent with the inability of the heterologous diguanylate cyclase genes to complement the S. epidermidis gdpS mutation.

FIG. 6.

Biochemical analysis of diguanylate cyclase activity of MBP-GdpS fusion proteins. (A) Protein purification (Bioanalyzer; Agilent Technologies). Lane M, molecular mass markers (kDa); lane 1, purified S. epidermidis GdpS GGDEF domain; lane 2, purified S. aureus GdpS GGDEF domain; lane 3, partially purified S. aureus GdpS protein (major band at approximately 80 kDa). (B) Diguanylate cyclase activity assays on the S. epidermidis GdpS GGDEF domain. A representative profile is shown (final concentration, 4 μM GGDEF domain). Substrate (top panel) at 0 min of incubation and products (middle panel) of 14-h incubation separated by reverse-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography. c-di-GMP (lower panel) is shown as a reference.

The GGDEF domain of GdpS is not essential for biofilm activation.

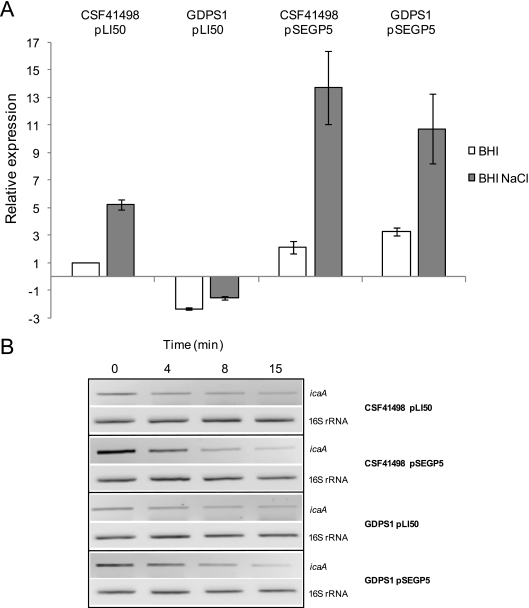

We further investigated the role of the GGDEF domain in GdpS-mediated biofilm activation. Using site-directed mutagenesis, we deleted two glutamic acid residues in the GGEEF motif (Fig. 1) involved in GTP binding and coordination of Mg2+ ions (47). We examined the ability of the resulting plasmid pSEGP7 (Fig. 7) to complement the GDPS1 mutant. We found that the mutated gdpS (GGDEF→GGF) gene complemented the GDPS1 mutant and enhanced the biofilm-forming capacity in CSF41498 similar to the wild-type gene (Fig. 7). This finding strongly indicates that biofilm activation by GdpS is independent of c-di-GMP synthesis or an intact GGDEF domain.

FIG. 7.

Role of GGEEF domain mutations on biofilm regulation by GdpS. Biofilm phenotypes of S. epidermidis CSF41498 and GDPS1 (gdpS::Emr) strains complemented with pLI50 (control), pSEGP7 (GdpS allele with GGF motif), and pSEGP8 (5′ end of gdpS encoding the predicted membrane-spanning region only). Strains were grown overnight at 37°C in BHI broth and BHI-NaCl broth. Biofilm formation was measured in 96-well microtiter plate assays at least three times, and standard deviations are indicated.

To further examine this possibility, we tested the ability of the transmembrane N terminus of GdpS alone (plasmid pSEGP8) to complement GDPS1 in trans. Significantly, the N-terminal fragment was capable of complementing GDPS1, albeit to a somewhat lesser extent than the full-length GdpS (plasmid pSEGP5) or GdpS GGEEF→GGF (plasmid pSEGP7) (Fig. 7). Taken together, these data strongly indicate that biofilm activation is independent of c-di-GMP synthetic activity of GdpS and further suggest that biofilm activation is primarily a function of the membrane-localized N terminus of GdpS.

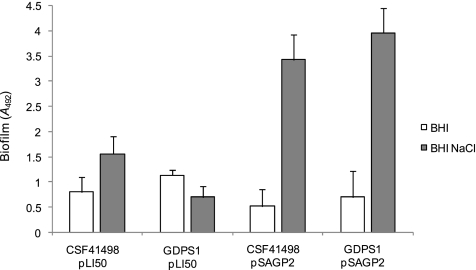

The mechanism of GdpS action on biofilm development is conserved in staphylococci.

The S. epidermidis GdpS orthologs from other staphylococci whose genomes have been sequenced are highly similar; e.g., the GdpS orthologs from S. aureus and S. epidermidis are approximately 83% identical (Fig. 1A). To investigate whether the role of GdpS in biofilm regulation is conserved in staphylococci, we cloned the S. aureus MW2 gdpS gene and examined its capacity to complement the S. epidermidis GDPS1 mutant. The S. aureus gdpS gene did complement the S. epidermidis GDPS1 mutant, and multicopy expression of this gene substantially activated biofilm formation in wild-type S. epidermidis CSF41498 (Fig. 8).

FIG. 8.

Biofilm phenotypes of S. epidermidis CSF41498 and GDPS1 (gdpS::Emr) strains complemented with pLI50 (control) and pSAGP2 (S. aureus gdpS). Strains were grown overnight at 37°C in BHI broth and BHI-NaCl medium. Biofilm formation was measured at least three times, and standard deviations are indicated.

To investigate whether the S. aureus protein is capable of c-di-GMP synthesis, we overexpressed its GGDEF domain as an MBP fusion in E. coli (Fig. 6A, lane 2). The purified protein showed no diguanylate cyclase activity but did show residual GTPase activity (Fig. 6B), similar to its S. epidermidis counterpart. We subsequently partially purified the full-length S. aureus GdpS protein to approximately 70% purity (Fig. 6A, lane 3). Partial purification was used to minimize the possible loss of enzymatic activity during final purification steps. However, none of several independent preparations of the full-length S. aureus GdpS had detectable diguanylate cyclase activity. These results are consistent with the lack of enzymatic activity of the GGDEF domains. Further, constructs overexpressing S. aureus GdpS or its GGDEF domain displayed no toxicity in E. coli BL21(DE3), and nucleotide extracts from the E. coli DH5α strains carrying these constructs produced no measurable increases in c-di-GMP levels compared to empty vector pMAL-c2x (data not shown). This is in contrast to the constructs overexpressing active diguanylate cyclases YeaP and Slr1143 (38).

Taken together, these data suggest that GdpS proteins from different staphylococcal species are functionally conserved and that their effect on icaADBC operon expression is independent of c-di-GMP. We found no evidence of diguanylate cyclase activity of GdpS and therefore suggest that this protein represents a remnant of an extinct diguanylate cyclase. Our data are consistent with the hypothesis that staphylococci lack a functional c-di-GMP signaling pathway. However, further experimentation is clearly needed to confirm this possibility.

DISCUSSION

In recent years, c-di-GMP-dependent signaling has emerged as an important regulatory system controlling bacterial transitions from motile to sessile lifestyles. c-di-GMP regulates motility, biofilm formation, and virulence in various species of the Proteobacteria (34, 38, 43). Some nonproteobacterial representatives of diverse branches of the bacterial phylogenetic tree also appear to utilize c-di-GMP signaling pathways because their GGDEF domain proteins possess diguanylate cyclase activity in vitro (38). While the mechanisms of c-di-GMP action are generally poorly characterized, its effect on exopolysaccharide synthesis is better understood. c-di-GMP binds to the PilZ domain and allosterically activates type 2 glycosyl transferases present in cellulose synthases of G. xylinus, E. coli, and Salmonella enterica (8, 35, 37). Alternatively, it binds to the proteins that are likely to interact with glycosyl transferases as was recently shown for the alginate and Pel polysaccharide synthase systems of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (26, 28).

Prior to our study essentially nothing was known about c-di-GMP-dependent pathways in Firmicutes. However, two recent studies analyzed the effect of exogenously added c-di-GMP on S. aureus. These studies revealed that biofilm formation by human clinical and bovine mastitis isolates of S. aureus was reduced by >50% in a 200 μM solution of c-di-GMP compared to untreated controls (5, 22). The range of concentrations of extracellular c-di-GMP used in these studies was significantly higher than the intracellular c-di-GMP levels reported in the proteobacteria, which are in the sub- to low-micromolar range (31, 40, 48). Since c-di-GMP permeability across the Staphylococcus cytoplasmic membrane is unknown, it is impossible to predict whether extracellular c-di-GMP affected intracellular c-di-GMP signaling pathways or acted at the cell surface. Importantly, the observation that c-di-GMP inhibited, as opposed to activated, biofilm in S. aureus suggests a different mechanism of action from mechanisms described in the Proteobacteria.

In this work, we investigated the potential role of c-di-GMP signaling in S. epidermidis and S. aureus biofilm regulation. The development of biofilms by these two staphylococcal species on surgically implanted biomaterials is the most common cause of device-related infections. We found that inactivation of the S. epidermidis gdpS gene encoding a conserved GGDEF domain protein resulted in significantly impaired biofilm formation under static and flow-cell conditions. Consistent with our observations in S. epidermidis, a recent screen of an S. aureus transposon mutant library (45) revealed that inactivation of the gdpS locus also impaired biofilm formation. Furthermore, the S. aureus gene, whose product is highly similar to that of S. epidermidis, fully complemented the S. epidermidis gdpS mutation. Taken together, these data strongly suggest that the mechanism of GdpS action is conserved in staphylococci.

We revealed that an impaired biofilm-forming capacity was caused by reduced PIA/PNAG production, which in turn resulted from decreased icaADBC expression. Therefore, the staphylococcal GdpS protein influences biofilm development at the level of icaADBC transcript. This is different from the mode of action of GGDEF domain diguanylate cyclases from the Proteobacteria, whose product, c-di-GMP, allosterically affects activities of exopolysaccharide synthases.

Sequence analysis of the GGDEF domain of GdpS does not establish whether this domain is enzymatically active or inactive. In this study we found no evidence that GdpS possesses diguanylate cyclase activity or that c-di-GMP plays any role in staphylococcal biofilm regulation. In contrast, several pieces of evidence show that GdpS activates biofilms in a c-di-GMP-independent manner: (i) the gdpS mutation is not complemented by heterologous diguanylate cyclases, (ii) the purified GdpS protein and its GGDEF domain are inactive in vitro, (iii) mutations in the GGEEF loop essential for diguanylate cyclase activity do not impair GdpS activity, and (iv) deletion of the entire GGDEF domain does not substantially interfere with GdpS-mediated biofilm activation.

While we cannot rule out that GdpS possesses diguanylate cyclase activity under some conditions, our data unambiguously establish that GdpS activates biofilm development independently of diguanylate cyclase activity. Interestingly, a diguanylate cyclase-independent function of a GGDEF domain protein has recently been described in a proteobacterial system. The E. coli GGDEF-EAL domain protein, CsrD, has been shown to affect biofilm formation by sequestering small regulatory RNAs for degradation (41). The mechanism of GdpS action appears to differ from that of CsrD because, unlike CsrD, the GGDEF domain of GdpS is not essential for biofilm regulation.

How GdpS activates icaADBC expression remains unclear. Our data show that ica mRNA stability is not affected by GdpS. We demonstrated that GdpS does not act through σB, which is known to regulate ica operon expression. σB was considered a likely target for GdpS action because σB is activated by osmotic stress (24) and because the contribution of GdpS to biofilm regulation was most evident in medium supplemented with NaCl. Similarly, GdpS does not appear to affect transcription of the ica operon transcription factors IcaR, SarA, TcaR, and LuxS. However, GdpS may control the activity of one or more of these regulators at a posttranscriptional level. Because expression of the ica operon regulator, IcaR, was found to be GdpS independent, our data suggest that GdpS may not influence the ethanol-inducible (10, 23) and ClpXP-Spx-dependent (15, 30) icaADBC regulatory pathways, both of which act through icaR. Additional experiments are under way to further investigate these possibilities and to elucidate the signal transduction pathway downstream of GdpS.

The lack of detectable diguanylate cyclase activity in GdpS suggests, but does not establish, that staphylococci may not synthesize c-di-GMP. This is consistent with the absence of a predicted genetic network of c-di-GMP signaling in the staphylococcal genomes sequenced to date. Therefore, at this point we favor the hypothesis that GdpS and GdpP represent remnants of a c-di-GMP pathway that no longer employs c-di-GMP. Interestingly, while c-di-GMP signaling is present only in Bacteria, GGDEF domain remnants have been described in some archaean genomes (38). It is remarkable that GdpS retains its involvement in biofilm regulation, albeit via a novel mechanism. It is interesting that the genomes of other Firmicutes, e.g., Bacillus or Listeria, contain several GGDEF and EAL domain genes, suggesting that they employ functional c-di-GMP signaling networks. The underlying reasons that make c-di-GMP-dependent signaling pathways more important for some bacterial lineages than others remain to be explored.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Irish Health Research Board and Irish Research Council for Science Engineering and Technology grants to (J. P. O'Gara), National Science Foundation grant MCB 0645876 (M. Gomelsky) and Public Health Service grant AI49311 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (P. D. Fey).

S. epidermidis strain CSF-2 was a kind gift from W. Ziebuhr, plasmid pLI50 was from C. Y. Lee, plasmids pCN51 and pCN38 were from R. Novick, and rabbit anti-PIA/PNAG serum was from T. Maira Litran and G. B. Pier. We are grateful to X.-F. Li and X. Fang (University of Wyoming) for making some of the gdpS constructs used in this work; to J. Cotter and E. Casey for assistance with flow cell biofilm analysis; and to K. Conlon, H. Humphreys, C. Pozzi, E. O'Neill, and P. Houston for their support and advice over the course of this study.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 23 May 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amikam, D., and M. Y. Galperin. 2006. PilZ domain is part of the bacterial c-di-GMP binding protein. Bioinformatics 223-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anantharaman, V., and L. Aravind. 2003. Application of comparative genomics in the identification and analysis of novel families of membrane-associated receptors in bacteria. BMC Genomics 434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnaud, M., A. Chastanet, and M. Debarbouille. 2004. New vector for efficient allelic replacement in naturally nontransformable, low-GC-content, gram-positive bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 706887-6891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beenken, K. E., J. S. Blevins, and M. S. Smeltzer. 2003. Mutation of sarA in Staphylococcus aureus limits biofilm formation. Infect. Immun. 714206-4211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brouillette, E., M. Hyodo, Y. Hayakawa, D. K. Karaolis, and F. Malouin. 2005. 3′,5′-Cyclic diguanylic acid reduces the virulence of biofilm-forming Staphylococcus aureus strains in a mouse model of mastitis infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 493109-3113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruckner, R. 1997. Gene replacement in Staphylococcus carnosus and Staphylococcus xylosus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1511-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charpentier, E., A. I. Anton, P. Barry, B. Alfonso, Y. Fang, and R. P. Novick. 2004. Novel cassette-based shuttle vector system for gram-positive bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 706076-6085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christen, M., B. Christen, M. G. Allan, M. Folcher, P. Jeno, S. Grzesiek, and U. Jenal. 2007. DgrA is a member of a new family of cyclic diguanosine monophosphate receptors and controls flagellar motor function in Caulobacter crescentus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1044112-4117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christen, M., B. Christen, M. Folcher, A. Schauerte, and U. Jenal. 2005. Identification and characterization of a cyclic di-GMP-specific phosphodiesterase and its allosteric control by GTP. J. Biol. Chem. 28030829-30837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conlon, K. M., H. Humphreys, and J. P. O'Gara. 2002. icaR encodes a transcriptional repressor involved in environmental regulation of ica operon expression and biofilm formation in Staphylococcus epidermidis. J. Bacteriol. 1844400-4408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conlon, K. M., H. Humphreys, and J. P. O'Gara. 2004. Inactivations of rsbU and sarA by IS256 represent novel mechanisms of biofilm phenotypic variation in Staphylococcus epidermidis. J. Bacteriol. 1866208-6219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conlon, K. M., H. Humphreys, and J. P. O'Gara. 2002. Regulation of icaR gene expression in Staphylococcus epidermidis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 216173-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cramton, S. E., C. Gerke, N. F. Schnell, W. W. Nichols, and F. Gotz. 1999. The intercellular adhesion (ica) locus is present in Staphylococcus aureus and is required for biofilm formation. Infect. Immun. 675427-5433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finn, R. D., J. Mistry, B. Schuster-Bockler, S. Griffiths-Jones, V. Hollich, T. Lassmann, S. Moxon, M. Marshall, A. Khanna, R. Durbin, S. R. Eddy, E. L. Sonnhammer, and A. Bateman. 2006. Pfam: clans, web tools and services. Nucleic Acids Res. 34D247-D251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frees, D., A. Chastanet, S. Qazi, K. Sorensen, P. Hill, T. Msadek, and H. Ingmer. 2004. Clp ATPases are required for stress tolerance, intracellular replication and biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 541445-1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galperin, M. Y. 2004. Bacterial signal transduction network in a genomic perspective. Environ. Microbiol. 6552-567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia, B., C. Latasa, C. Solano, F. G. Portillo, C. Gamazo, and I. Lasa. 2004. Role of the GGDEF protein family in Salmonella cellulose biosynthesis and biofilm formation. Mol. Microbiol. 54264-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gertz, S., S. Engelmann, R. Schmid, K. Ohlsen, J. Hacker, and M. Hecker. 1999. Regulation of sigmaB-dependent transcription of sigB and asp23 in two different Staphylococcus aureus strains. Mol. Gen. Genet. 261558-566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heilmann, C., O. Schweitzer, C. Gerke, N. Vanittanakom, D. Mack, and F. Gotz. 1996. Molecular basis of intercellular adhesion in the biofilm-forming Staphylococcus epidermidis. Mol. Microbiol. 201083-1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hennig, S., S. Nyunt Wai, and W. Ziebuhr. 2007. Spontaneous switch to PIA-independent biofilm formation in an ica-positive Staphylococcus epidermidis isolate. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 297117-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jefferson, K. K., D. B. Pier, D. A. Goldmann, and G. B. Pier. 2004. The teicoplanin-associated locus regulator (TcaR) and the intercellular adhesin locus regulator (IcaR) are transcriptional inhibitors of the ica locus in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 1862449-2456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karaolis, D. K., M. H. Rashid, R. Chythanya, W. Luo, M. Hyodo, and Y. Hayakawa. 2005. c-di-GMP (3′-5′-cyclic diguanylic acid) inhibits Staphylococcus aureus cell-cell interactions and biofilm formation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 491029-1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knobloch, J. K., K. Bartscht, A. Sabottke, H. Rohde, H. H. Feucht, and D. Mack. 2001. Biofilm formation by Staphylococcus epidermidis depends on functional RsbU, an activator of the sigB operon: differential activation mechanisms due to ethanol and salt stress. J. Bacteriol. 1832624-2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knobloch, J. K., S. Jager, M. A. Horstkotte, H. Rohde, and D. Mack. 2004. RsbU-dependent regulation of Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilm formation is mediated via the alternative sigma factor sigmaB by repression of the negative regulator gene icaR. Infect. Immun. 723838-3848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kreiswirth, B. N., S. Lofdahl, M. J. Betley, M. O'Reilly, P. M. Schlievert, M. S. Bergdoll, and R. P. Novick. 1983. The toxic shock syndrome exotoxin structural gene is not detectably transmitted by a prophage. Nature 305709-712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee, V. T., J. M. Matewish, J. L. Kessler, M. Hyodo, Y. Hayakawa, and S. Lory. 2007. A cyclic-di-GMP receptor required for bacterial exopolysaccharide production. Mol. Microbiol. 651474-1484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lim, Y., M. Jana, T. T. Luong, and C. Y. Lee. 2004. Control of glucose- and NaCl-induced biofilm formation by rbf in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 186722-729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merighi, M., V. T. Lee, M. Hyodo, Y. Hayakawa, and S. Lory. 2007. The second messenger bis-(3′-5′)-cyclic-GMP and its PilZ domain-containing receptor Alg44 are required for alginate biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 65876-895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Gara, J. P. 2007. ica and beyond: biofilm mechanisms and regulation in Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 270179-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pamp, S. J., D. Frees, S. Engelmann, M. Hecker, and H. Ingmer. 2006. Spx is a global effector impacting stress tolerance and biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 1884861-4870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paul, R., S. Weiser, N. C. Amiot, C. Chan, T. Schirmer, B. Giese, and U. Jenal. 2004. Cell cycle-dependent dynamic localization of a bacterial response regulator with a novel di-guanylate cyclase output domain. Genes Dev. 18715-727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pratt, J. T., R. Tamayo, A. D. Tischler, and A. Camilli. 2007. PilZ domain proteins bind cyclic diguanylate and regulate diverse processes in Vibrio cholerae. J. Biol. Chem. 28212860-12870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramelot, T. A., A. Yee, J. R. Cort, A. Semesi, C. H. Arrowsmith, and M. A. Kennedy. 2007. NMR structure and binding studies confirm that PA4608 from Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a PilZ domain and a c-di-GMP binding protein. Proteins 66266-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Romling, U., M. Gomelsky, and M. Y. Galperin. 2005. c-di-GMP: the dawning of a novel bacterial signaling system. Mol. Microbiol. 57629-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ross, P., H. Weinhouse, Y. Aloni, D. Michaeli, P. Weinberger-Ohana, R. Mayer, S. Braun, E. de Vroom, G. A. van der Marel, J. H. van Boom, and M. Benziman. 1987. Regulation of cellulose synthesis in Acetobacter xylinum by cyclic diguanylic acid. Nature 325279-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ryan, R. P., Y. Fouhy, J. F. Lucey, L. C. Crossman, S. Spiro, Y. W. He, L. H. Zhang, S. Heeb, M. Camara, P. Williams, and J. M. Dow. 2006. Cell-cell signaling in Xanthomonas campestris involves an HD-GYP domain protein that functions in cyclic di-GMP turnover. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1036712-6717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 37.Ryjenkov, D. A., R. Simm, U. Romling, and M. Gomelsky. 2006. The PilZ domain is a receptor for the second messenger c-di-GMP: the PilZ domain protein YcgR controls motility in enterobacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 28130310-30314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ryjenkov, D. A., M. Tarutina, O. V. Moskvin, and M. Gomelsky. 2005. Cyclic diguanylate is a ubiquitous signaling molecule in bacteria: insights into biochemistry of the GGDEF protein domain. J. Bacteriol. 1871792-1798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmidt, A. J., D. A. Ryjenkov, and M. Gomelsky. 2005. The ubiquitous protein domain EAL is a cyclic diguanylate-specific phosphodiesterase: enzymatically active and inactive EAL domains. J. Bacteriol. 1874774-4781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simm, R., M. Morr, A. Kader, M. Nimtz, and U. Romling. 2004. GGDEF and EAL domains inversely regulate cyclic di-GMP levels and transition from sessility to motility. Mol. Microbiol. 531123-1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suzuki, K., P. Babitzke, S. R. Kushner, and T. Romeo. 2006. Identification of a novel regulatory protein (CsrD) that targets the global regulatory RNAs CsrB and CsrC for degradation by RNase E. Genes Dev. 202605-2617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tal, R., H. C. Wong, R. Calhoon, D. Gelfand, A. L. Fear, G. Volman, R. Mayer, P. Ross, D. Amikam, H. Weinhouse, A. Cohen, S. Sapir, P. Ohana, and M. Benziman. 1998. Three cdg operons control cellular turnover of cyclic di-GMP in Acetobacter xylinum: genetic organization and occurrence of conserved domains in isoenzymes. J. Bacteriol. 1804416-4425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tamayo, R., J. T. Pratt, and A. Camilli. 2007. Roles of cyclic diguanylate in the regulation of bacterial pathogenesis. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 61131-148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tormo, M. A., M. Marti, J. Valle, A. C. Manna, A. L. Cheung, I. Lasa, and J. R. Penades. 2005. SarA is an essential positive regulator of Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilm development. J. Bacteriol. 1872348-2356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tu Quoc, P. H., P. Genevaux, M. Pajunen, H. Savilahti, C. Georgopoulos, J. Schrenzel, and W. L. Kelley. 2007. Isolation and characterization of biofilm formation-defective mutants of Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 751079-1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Valle, J., A. Toledo-Arana, C. Berasain, J. M. Ghigo, B. Amorena, J. R. Penades, and I. Lasa. 2003. SarA and not sigmaB is essential for biofilm development by Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 481075-1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wassmann, P., C. Chan, R. Paul, A. Beck, H. Heerklotz, U. Jenal, and T. Schirmer. 2007. Structure of BeF3-modified response regulator PleD: implications for diguanylate cyclase activation, catalysis, and feedback inhibition. Structure 15915-927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weinhouse, H., S. Sapir, D. Amikam, Y. Shilo, G. Volman, P. Ohana, and M. Benziman. 1997. c-di-GMP-binding protein, a new factor regulating cellulose synthesis in Acetobacter xylinum. FEBS Lett. 416207-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu, L., H. Li, C. Vuong, V. Vadyvaloo, J. Wang, Y. Yao, M. Otto, and Q. Gao. 2006. Role of the luxS quorum-sensing system in biofilm formation and virulence of Staphylococcus epidermidis. Infect. Immun. 74488-496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]