Abstract

One-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis followed by nanocapillary liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry was used to analyze proteins isolated from Staphylococcus aureus UAMS-1 after 3, 6, 12, and 24 h of in vitro growth. Protein abundance was determined using a quantitative value termed normalized peptide number, and overall, proteins known to be associated with the cell wall were more abundant early on in growth, while proteins known to be secreted into the surrounding milieu were more abundant late in growth. In addition, proteins from spent media and cell lysates of strain UAMS-1 and its isogenic sarA, agr, and sarA agr regulatory mutant strains during exponential growth were identified, and their relative abundances were compared. Extracellular proteins known to be regulated by the global regulators sarA and agr displayed protein levels in accordance with what is known regarding the effects of these regulators. For example, cysteine protease (SspB), endopeptidase (SspA), staphopain (ScpA), and aureolysin (Aur) were higher in abundance in the sarA and sarA agr mutants than in strain UAMS-1. The immunoglobulin G (IgG)-binding protein (Sbi), immunodominant staphylococcal antigen A (IsaA), IgG-binding protein A (Spa), and the heme-iron-binding protein (IsdA) were most abundant in the agr mutant background. Proteins whose abundance was decreased in the sarA mutant included fibrinogen-binding protein (Fib [Efb]), IsaA, lipase 1 and 2, and two proteins identified as putative leukocidin F and S subunits of the two-component leukotoxin family. Collectively, this approach identified 1,263 proteins (matches of two peptides or more) and provided a convenient and reliable way of identifying proteins and comparing their relative abundances.

Staphylococcus aureus remains an important bacterial pathogen responsible for numerous disease syndromes in humans and animals worldwide (2, 13). The prominence of this organism in both community- and hospital-acquired diseases accounts for approximately 25% of all bloodstream and lower respiratory tract infections and almost 40% of all skin and soft tissue infections (13). Just as important is the continual rise in the number of methicillin (oxacillin)-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) not only in isolates acquired in hospitals but also in isolates encountered in the community (13). In most cases involving hospital-acquired MRSA, the only remaining drugs of choice with sufficient efficacy are the glycopeptide antibiotics (vancomycin and teicoplanin) of which vancomycin has been used for over 30 years without the advent of resistance (55). Unfortunately, this is no longer the case. Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates with intermediate levels of resistance to vancomycin have been isolated both abroad and in the United States, and their prevalence appears to be on the rise (55). Most ominous is the recent isolation of S. aureus clinical strains that contain the vanA gene and are resistant to high levels of vancomycin (10, 59, 64).

Because of the capacity of S. aureus to cause multiple disease syndromes in both the community and hospital settings along with its ability to become resistant to most, if not all, antibiotics currently approved for use in the United States, it has become increasingly important that alternative approaches for preventing and treating staphylococcal infections be developed. To this cause, recent research efforts have focused on whole-genome sequencing and microarray and proteomic technologies to analyze multiple strains of S. aureus under a variety of conditions in order to generate a more comprehensive knowledge base of this organism (reviewed in references 30 and 37). Many of these have utilized two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (2D-PAGE) to resolve proteins in complex mixtures and while 2D-PAGE is a valuable tool in generating protein profiles, there are limitations in using this approach, e.g., 2D-PAGE is labor-intensive and time-consuming (28). Therefore, in order to compare protein preparations from S. aureus, our approach has involved the use of one-dimensional PAGE (1D-PAGE) followed by high-sensitivity, nanocapillary liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (nanoLC-MS-MS) (22). Using this approach, we have shown that the number of spectra matching a given protein, termed “spectral count” (38) is an indication of protein abundance, and we used spectral counts to compare the relative abundances of proteins isolated from S. aureus UAMS-1 at 3, 6, 12, and 24 h and UAMS-1 and its regulatory mutants during exponential growth.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

The osteomyelitis clinical isolate Staphylococcus aureus UAMS-1 (ATCC 49230) (25) and its isogenic mutants, the sarA::kan mutant (3), the Δagr::tetA(M) mutant (3), and UAMS-1 containing both mutations (sarA agr mutant) (3), were kindly provided by Mark Smeltzer (University of Arkansas for Medical Science, Little Rock, AR). Strains were maintained as frozen (−80°C) stocks procured in brain heart infusion broth containing 25% (wt/vol) glycerol. Frozen strains were streaked for isolation onto tryptic soy agar (TSA) (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) with the following appropriate antibiotics: 50 μg/ml (each) of kanamycin (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) and neomycin (Sigma) for the sarA mutant, 5 μg/ml of tetracycline (Sigma) for the agr mutant, and all three antibiotics for the sarA agr mutant. Flasks containing Tryptic soy broth (TSB; Difco) (a flask-to-broth volumetric ratio of 2.5) with antibiotic were inoculated from plate cultures and incubated overnight (15 to 18 h) at 37°C with rotary aeration (180 rpm). Overnight cultures were harvested by centrifugation (12,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C), washed twice with sterile TSB, and suspended in an equal volume of TSB. Washed cells were used to inoculate 240 ml of sterile TSB without antibiotic to an optical density at 550 nm (OD550) of approximately 0.05 as measured spectrophotometrically. Each culture was aseptically dispensed as 60-ml portions into each of four 125-ml flasks (a flask-to-broth volumetric ratio of 2.1). The flasks were incubated as described above, growth was monitored spectrophotometrically, and after 3, 6, 12, and 24 h of growth, a flask for each strain was removed, and when applicable, cultures were standardized with respect to optical density using sterile TSB.

Spent medium preparation.

Cells from 40-ml portions of cultures were harvested by centrifugation (12,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C), and spent media were filter sterilized through 0.2-μm polyethersulfone filters (Nalge Nunc International, Rochester, NY) and dispensed as four 10-ml portions into four 50-ml polypropylene conical centrifuge tubes with each tube containing 10 ml of ice-cold sterile water. Dilute spent media were vortexed to mix and quick-frozen on dry ice and ethanol. Frozen spent media were stored at −80°C overnight prior to lyophilization. Frozen spent media were lyophilized to dryness (approximately 24 to 48 h) and stored at −80°C. Each lyophilized spent medium was suspended in 1 ml of sterile, ice-cold water, and the four suspensions for each strain were combined. The suspensions were concentrated using ultrafiltration (Amicon Ultra-4 filters with 5,000-molecular-weight cutoff; Millipore Corporation, Bedford, ME) and overnight centrifugation (2,000 × g) at 4°C. The retentate volumes were determined, and proteins were precipitated by adding trichloroacetic acid (final concentration of 10%). The suspensions were stored at 4°C overnight (15 to 18 h). The precipitated proteins were pelleted by centrifugation (14,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C), washed twice with ice-cold acetone, and dried using a Speed-Vac (Thermo Savant, Holbrook, NY). Each protein pellet was suspended in 0.1 ml of 0.0625 M Tris-base (pH 6.8) containing 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and stored at −80°C until needed.

Cell lysate preparation.

Cells from 40-ml cultures were harvested by centrifugation (12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C), washed with an equal portion of TEG buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0] containing 25 mM EGTA [pH 8.0]), and suspended in 400 μl of TEG buffer (3). Cell suspensions were transferred to FastPrep blue tubes (Qbiogene, Irvine, CA) containing acid-washed and RNase-free, 0.1-mm silica beads and lysed using the FP120 reciprocator (Qbiogene) with a setting of 6 m/second for 40 seconds. Cell lysates were immediately cooled on ice for 15 min and then subjected to centrifugation (10,000 × g for 1 min at 4°C). The supernatants were recovered, dispensed as 50-μl portions, and stored at −80°C.

SDS-PAGE and in-gel digestion.

Frozen protein suspensions were thawed, mixed by vortexing for 30 seconds, and kept on ice until used. Seven-microliter aliquots were solubilized in loading buffer and resolved using 4 to 12% gradient gels as recommended by the manufacturer (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Each lane from the dye front to an area corresponding to approximately 160 kDa was manually cut into 40 1- by 5-millimeter gel slices, and each slice was transferred to a well of a 96-well plate. The proteins in each gel slice were robotically (ProGest; Genomic Solutions, Ann Arbor, MI) reduced with 10 mM dithiothreitol, alkylated with 50 mM iodoacetamide, and digested with 160 ng of trypsin. Slices were analyzed following acidification with 0.5% formic acid to a final pH of 3.8. The peptide mixture for each band was approximately 50 μl.

Analysis of proteins by nanoLC-MS-MS. (i) nanoLC-MS-MS parameters.

The resulting 50-μl peptide pools were analyzed using nanoLC-MS-MS on a LCQ Deca XP Plus ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo, San Jose, CA). Forty-two microliters of sample was loaded using an Endurance autosampler (Micro-Tech Scientific, Vista, CA) on an IntegraFrit (New Objective, Woburn, ME) vented 75-μm by 3-cm column packed with 0.5-mm Jupiter C12 material (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) at 14 μl/min. Peptides were eluted with a 50-min gradient (0.1 to 30% solution B in 35 min, 30 to 50% solution B in 10 min, and 50 to 80% solution B in 5 min, where solution A is 99.8% H2O, 0.1% acetonitrile, and 0.1% formic acid and solution B is 80% acetonitrile, 19.9% H2O, and 0.1% formic acid) at 200 nanoliters/min (generated with a split tee) using an Ultra Plus II capillary high-performance liquid chromatography pump (Micro-Tech Scientific) over a 75-μm by 15-cm IntegraFrit analytical column packed also with Jupiter C12 material. The column was coupled to a 30-μm-inner diameter by 3-cm stainless steel emitter (Proxeon, Odense, Denmark). MS-MS was performed on the top four ions in each MS scan using the data-dependent acquisition mode. Normalized collision energy was set at 35%, and three microscans were summed following automatic gain control (enables the trap to fill with ions to the set ion target values) implementation. The target values for MS and MS-MS were 5 × 108 and 6 × 107 counts, respectively. Dynamic exclusion and repeat settings ensured each ion was selected only once and excluded for 30 s thereafter.

(ii) Quantitative determination of proteins.

The relationship between spectral count and amount of protein present was investigated using known amounts of protein standards. Equal portions of spent media in which S. aureus UAMS-1 had been grown for 3 hours containing either 11, 23, 46, 69, 115, 230, 460, or 690 ng of phosphorylase b (97 kDa; Sigma), ovalbumin (45 kDa; Sigma), and carbonic anhydrase (29 kDa; Sigma) were resolved by SDS-PAGE. Bands corresponding to each of the molecular weight markers were excised and digested and analyzed by nanoLC-MS-MS as described above.

(iii) Bioinformatic applications.

Production data were searched against the European Bioinformatics Institute protein databases for S. aureus MW2, Mu50, and Sanger 252 (epidemic methicillin-resistant S. aureus strain 16 [EMRSA-16]) using a locally stored copy of the Mascot search engine (version 2.1.0; Matrix Science, London, United Kingdom) with Mascot Daemon (version 2.1). The search parameters follow: precursor mass tolerance of 2.5 Da, product ion mass tolerance of 0.6 Da, two missed cleavages allowed, fully tryptic peptides only, fixed modification of carbamidomethyl cysteine, variable modifications of oxidized methionine, N-terminal acetylation, and pyro-glutamic acid on N-terminal glutamine. Mascot search result flat files (.DAT) were parsed to an Oracle database using in-house software called ProteinTrack (22); all peptides with a Mascot score of 15 or greater were saved. ProteinTrack allows multifunction querying of Mascot data sets, including the generation of protein summary lists based on user-defined scoring criteria, comparison of multiple experiments, output of peptide sequences matched for each protein, and graphical representation of protein identifications across DAT files (i.e., down a SDS-polyacrylamide gel). Protein summary lists include protein name, accession number, molecular mass, total Mascot protein score, number of unique peptides matched, number of times those peptides were observed (spectral count), and sequence coverage. ProteinTrack removes protein isoforms that do not have at least one significantly scoring peptide to allow distinction as a unique protein.

The criteria for accepting a protein match were determined by calculating the false discovery rate (FDR) through searching a data set (S. aureus UAMS-1) against a reversed database (S. aureus MW2). This resulted in the following cutoff values: for matches of two peptides or more, the total protein score had to be ≥57 with a minimum peptide score of 21; the minimum peptide molecular mass allowed was ≥600 Da and a protein was required to have at least one peptide representing the highest ranking assignment as determined by Mascot. These criteria resulted in a FDR of <0.1% at both the peptide and protein level. Single-peptide matches were not used in this study unless otherwise stated.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Growth and SDS-PAGE analysis.

Staphylococcus aureus UAMS-1 and its regulatory mutants were grown at 37°C with rotary aeration (180 rpm) in TSB without antibiotics. Growth was monitored spectrophotometrically (Fig. 1) and at 3 (OD550 of ≈1.5), 6 (OD550 of ≈3.7), 12 (OD550 of ≈6.5), and 24 (OD550 of ≈8.2) hours of growth, spent media and/or cells were harvested.

FIG. 1.

A representative growth curve as determined spectrophotometrically of S. aureus UAMS-1 and its sarA, agr, and sarA agr regulatory mutants grown in TSB at 37°C with rotary aeration (180 rpm). S. aureus UAMS-1 (•), sarA (○), agr (▾), and sarA agr (▵) mutants are shown.

Because of the differences observed in optical densities for S. aureus UAMS-1 and its regulatory mutants, cultures at the designated time points were standardized using optical density measurements. Protein concentration determinations were not used for culture standardization because of the sarA and agr global effects on total protein amounts. In addition, we noted protein concentration determinations were always misrepresented by a constant background signal which we surmised was due to the presence of a Coomassie blue-stained, intense broad region of low molecular mass observed by SDS-PAGE for all strains (Fig. 2a and b). Mass spectrometric analysis of this region indicated that this material did not come from S. aureus. Subsequent SDS-PAGE of the growth medium (TSB) alone, prepared as for spent media, revealed a similar staining pattern (data not shown). Digestion, nanoLC-MS-MS analysis, and product ion data searching using the nrNCBI database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) showed that α-casein and β-casein peptides were highly abundant in these low-molecular-mass regions (data not shown). This was not surprising, considering that TSB is primarily the product of pancreatic digestion of casein. However, the presence of this material precluded the use of protein concentration determinations as a means of standardization.

FIG. 2.

(a) A representative gel of a 1D SDS-PAGE analysis of spent media isolated from S. aureus UAMS-1 after 3, 6, 12, and 24 h of growth in TSB at 37°C with rotary aeration at 180 rpm. (b) A representative gel of a 1D SDS-PAGE analysis of spent media isolated from S. aureus UAMS-1 and its sarA, agr, and sarA agr regulatory mutants after 3 h of growth in TSB at 37°C with rotary aeration at 180 rpm. (c) A representative gel of a 1D SDS-PAGE analysis of cell lysates isolated from S. aureus UAMS-1 and its sarA, agr, and sarA agr regulatory mutants after 3 h of growth in TSB at 37°C with rotary aeration at 180 rpm. The positions of molecular mass markers in lanes M (in kilodaltons) are shown to the left of the gels.

Utilization of spectral counts detected as an indicator of relative protein abundance.

Because gene regulation in S. aureus is often seen as either an increase or decrease in message levels that subsequently leads to a corresponding increase or decrease in protein levels, we investigated whether spectral counts per protein, as detected by nanoLC-MS-MS, could be used as a measure of protein abundance and relate these values to time in growth and to the regulatory function of the sarA and agr genes. The spectral count was defined as the number of times peptides matching a given protein were observed. This included repeats of the same peptide as well as the same peptide with posttranslational modifications. This is in contrast to the unique peptide count, which excludes the repeats and the posttranslationally modified peptides. As the abundance of a protein increases, the number of peptides that are observable also increases; concurrently, the number of times that the instrument will detect the same peptide will also increase. Several studies have shown the utility of this parameter; however, most have employed solution-based digestion with either a shotgun or MudPIT proteomic analysis (reviewed in reference 65).

In the present study, we used 1D-PAGE combined with nanoLC-MS-MS in an attempt to obtain higher levels of coverage and, therefore, better statistics per protein. To validate this approach, known quantities of purified rabbit phosphorylase b (97 kDa), chicken ovalbumin (45 kDa), and bovine carbonic anhydrase (29 kDa) were “spiked” into spent media in which S. aureus UAMS-1 had grown for 3 hours. Each quantity was processed in triplicate; the reproducibility values of each replicate as measured as the mean deviation across 24 measurements of spectral and unique peptide count per protein were 4.0 and 5.0%, respectively (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). As expected, the utility of unique peptides (see Fig. S1a in the supplemental material) was limited, and with the protein quantities used in these experiments, saturation was reached by approximately 60 ng. The relationship between spectral count and quantity was not linear, as suggested by MacCoss et al. (40) but was logarithmic. For each of the three proteins, the correlation (R2) value was >0.98 (see Fig. S1b in the supplemental material). This could be due to all peptides from a given protein being present in only one or two bands, resulting in spectral count saturation occurring more quickly than in the case when MudPIT analysis is used and peptides are observed to be distributed across multiple fractions generated with strong cation-exchange chromatography (reviewed in reference 65).

In order to apply this approach to the analysis of actual samples, the disparity needed to be corrected between the slopes (m) of the lines and their y intercepts for each “spiked” protein. To do this, the spectral count for a given protein was adjusted to take into account the molecular mass of that protein and then multiplied by 104 to yield an arbitrary value which we have termed the normalized peptide number (NPN). The NPN plotted against the natural log of the amount of protein loaded yielded a more consistent value for the slope and intercept (see Fig. S1c in the supplemental material). We chose to use an averaged equation to determine relative quantitative values in the analyses of spent media. It is clear from these data that the use of 1D-PAGE and nanoLC-MS-MS yields a reproducible method of generating spectral count and that there is a logarithmic relationship with that number and the amount of a given protein that is present. The dramatic differences observed between lanes (based on spectral count) meant that at least one measure of NPN for the majority of proteins fell outside the quantitation range provided by the calibration curve (∼7.5 to 35), making it difficult to accurately predict changes in spectral counts. The data clearly show when a change in spectral count is detected, it is an indication that the corresponding protein is changing in abundance. Therefore, these values can be used as an indication of change.

Proteins identified from spent media in which S. aureus UAMS-1 had grown for 3, 6, 12, and 24 h.

The numbers of proteins identified from spent media in which S. aureus UAMS-1 had grown for various times using the S. aureus Sanger 252 (EMRSA-16) protein database were 427, 293, 375, and 333 for 3, 6, 12, and 24 h of growth, respectively (Table 1). The combined analysis identified 541 unique proteins with an overall mean and median number of peptides per protein of 9.9 ± 0.2 and 5.5 ± 0.6, respectively (Table 1). Proteins were classified with respect to their location as either extracellular, cell wall associated, membrane, cytoplasmic, or unknown as determined by PSORTb software (23). Of the 541 unique proteins identified, 328 (60.6%) were determined to be cytoplasmically located, while 44 (8.1%) were extracellular or secreted, 19 (3.5%) were cell wall associated, 22 (4.1%) were localized to the membrane, and the location of 128 (23.7%) proteins could not be determined. The accession numbers of those proteins whose location could not be determined using the PSORTb software (23) were manually submitted to the UniProt Knowledgebase System (60), and of the 128 proteins whose location was unknown, we were able to ascribe a probable location for 90 proteins. Utilizing both programs, 387 (71.5%) proteins were cytoplasmic, 60 (11.1%) were extracellular or secreted, 19 (5.7%) were cell wall associated, 37 (6.8%) were membrane, and only 38 (7.0%) remained unknown with respect to their location. It must be pointed out that while PSORTb and UniProt Knowledgebase systems were used to identify a tentative protein location for the proteins identified using this approach, the definitive location of these proteins has not been experimentally determined.

TABLE 1.

Peptide statistics for spent media in which S. aureus UAMS-1 had grown for 3, 6, 12, and 24 h

| Time (h) of growth | No. of proteins | No. of unique peptides | Total no. of peptides | Mean no. of unique peptides/protein | Median no. of unique peptides/protein |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 427 | 4,146 | 10,362 | 9.7 | 6 |

| 6 | 293 | 2,861 | 9,552 | 9.8 | 5 |

| 12 | 375 | 3,834 | 16,273 | 10.2 | 6 |

| 24 | 333 | 3,344 | 14,604 | 10.0 | 5 |

(i) Extracellular (secreted) proteins detected in spent media in which S. aureus UAMS-1 had grown for 3, 6, 12, and 24 h.

Forty-one (68.3%) of the 60 proteins identified as extracellular or secreted possess a putative signal peptide (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Some of the most abundant extracellular proteins detected for S. aureus UAMS-1 included the immunoglobulin G (IgG)-binding protein (sbi [SAR2508]), the immunodominant staphylococcal antigen A (isaA [SAR2650]), two different lipases (lip1 [SAR2753] and lip2 [SAR0317]), and the bifunctional autolysin (atl [SAR1026]) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

Some of the proteins classified as extracellular or secreted and not containing a putative signal peptide included delta-hemolysin (hld; SAR2122), the zinc metalloproteinase, aureolysin (aur; SAR2716), phospholipase c (plc; SAR0105), thermonuclease (nuc; SAR0847), and a hypothetical protein with 100% amino acid identity (data not shown) to the EsxA protein (esxA; SAR0279). The EsxA protein was one of two proteins secreted by a “specialized secretion pathway” found in S. aureus Newman and subsequently shown to be an important virulence factor in a mouse model of septicemia (6). The EsxA protein appears to be somewhat conserved, since it is found in 8 of the 14 sequenced strains of S. aureus and exhibits 100% amino acid identity in all cases (data not shown).

Utilizing the normalized peptide number as a measure of quantity, an expression profile for a number of selected proteins was determined (Fig. 3). Both lipases were expressed at moderate levels after 3 and 6 hours of growth but increased substantially by 12 h of growth (Fig. 3a). By 24 h, quantities of both lipases had increased to levels above that for any other extracellular protein detected. Thermonuclease (nuc; SAR0847), staphopain (scpA; SAR2001), and enterotoxin A (sea; SAR2043) were exhibited in different amounts after 3 hours of growth, but all exhibited a slight to moderate rise in protein quantity as cells went from exponential to postexponential phase (6 and 12 h) of growth and decreased slightly by 24 h of growth (Fig. 3a). The immunodominant staphylococcal antigen A protein showed a rise in protein abundance, but after 6 hours of growth, along with the IgG-binding protein and the staphylocoagulase protein (coa; SAR0222), levels decreased with time (Fig. 3a). Protein abundance for staphylokinase (sak; SAR2039) was low, and other than not being detectable after 6 hours of growth, the protein was detected at all other time points throughout growth with no appreciable increase or decrease in protein quantity (Fig. 3a).

FIG. 3.

Normalized peptide number of a select group of known virulence factors (a), known cytolytic proteins (b), known proteases (c), and putative exported proteins (d) detected in spent media isolated from S. aureus UAMS-1 after 3, 6, 12, and 24 h of growth.

A number of known cytolytic toxins (reviewed in references 4 and 14) were detected and examined for their protein expression profiles (Fig. 3b). Protein levels for all three subunits of the two-component gamma-hemolysin (hlgA [SAR2509], hlgB [SAR2511], and hlgC [SAR2510]) as well as two proteins identified as putative leukocidin S (lukS [SAR2108]) and F (lukF [SAR2107]) subunits of the class S and F categories of the two-component leukocidins (48) were observed to increase once cells entered the postexponential phase of growth (6 h) and continued to increase throughout the stationary phase of growth (12 and 24 h) (Fig. 3b). Previously, Cassat et al. (8, 9) has shown that S. aureus UAMS-1 does not contain genes for either the LukSF-PV or the LukD/E leukocidins, thereby indicating that these two proteins found in UAMS-1 spent media are different members of the leukocidin family. Whether these proteins are important to S. aureus UAMS-1 virulence is not known but it is currently under investigation.

Delta-hemolysin (hld; SAR2122), the 26-amino-acid peptide encoded within the RNAIII transcript of the extracellular protein regulator, agr (32), was detectable at low levels after 3 and 6 hours of growth, and after 12 and 24 h of growth, the abundance of delta-hemolysin was one of the highest of the cytolytic toxins detected (Fig. 3b). The delta-hemolysin protein expression profile is indicative of what is observed with many extracellular proteins secreted in response to RNAIII induction during the late-exponential phase of growth (reviewed in references 5, 11, and 46).

A second, less-abundant, small (44-amino-acid), low-molecular-mass (4.5-kDa) protein (antibacterial protein; Q6GHR1) that exhibited an expression profile similar to the profile of delta-hemolysin was detected (Fig. 3b). The amino acid sequence of this peptide was found to be similar (54 to 76% amino acid identity) to three highly related peptides (63) originally identified in Staphylococcus haemolyticus as a “gonococcal growth inhibitor” (1). Since that time, these peptides have been found in a number of coagulase-negative staphylococci that exhibit a synergistic zone of complete hemolysis with beta-hemolysin-producing strains on sheep blood, much like the delta-hemolysin of S. aureus (15, 16, 29). In Staphylococcus lugdunensis, these peptides, known as SLUSH-A, SLUSH-B, and SLUSH-C (slush for S. lugdunensis synergistic hemolysin), are encoded within a single operon and exhibit similarity (ranging from 43 to 73% amino acid identity) to those peptides originally found in S. haemolyticus (15, 16). Similar low-molecular-mass peptides have been found in Staphylococcus epidermidis as well, as peptides that partitioned in hot aqueous phenol (42). These peptides, phenol-soluble modulin α (PSMα), PSMβ, and PSMγ, were shown to activate the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 long terminal repeat and induce cytokine release in macrophages, most likely through the interaction of these peptides with the host cell transcriptional factor NF-κB (42). Most recently, Wang et al. (62) have found similar low-molecular-mass peptides in several strains of S. aureus in an effort to characterize virulence factors in community-acquired MRSA. Two groups of peptides were found to be related to the PSMα and PSMβ groups of S. epidermidis, and the genes for these peptides were shown to be present in all of the sequenced strains of S. aureus, although production of the peptides in community-acquired MRSA strains was more prevalent than in hospital-acquired MRSA strains (62). Utilizing murine models of bacteremia and abscess formation, Wang et al. (62) further demonstrated that these peptides are important in virulence, the PSMα group peptides more so than the PSMβ group peptides. The amino acid sequence of the antibacterial protein in S. aureus Sanger 252 (Q6GHR1; SAR1150) that was detected in S. aureus UAMS-1 is identical to the PSMβ1 peptide identified in S. aureus MW2 (Q8NX40; MW1056) (62).

One further point of interest regarding delta-hemolysin is that while this peptide exists as a 26-amino-acid peptide secreted without the assistance of a signal peptide (21, 36), it contains an N-terminal formylmethionine (21), and the peptide resides within a 45-codon open reading frame designated Hld-45 (32). The Hld-45 peptide was not detected in our present study, but nanoLC-MS-MS did detect a tryptic peptide of the first 14 amino acids of delta-hemolysin after 3, 6, 12, and 24 h of growth (data not shown). With the exception of the 3-h time point, the predominant form of this tryptic peptide contained a formylated N-terminal methionine that accounted for either all (6-h time point) or approximately half of the total number of 14-amino-acid peptides detected (data not shown). The remaining portion of this tryptic peptide contained either an acetylated N-terminal methionine or was deformylated (data not shown). The presence of the deformylated form of delta-hemolysin is probably due to the posttranslational removal of the formyl group by peptide deformylase (reviewed in reference 24) and not the result of proteolytic cleavage of the Hld-45 peptide (54). It is interesting to point out that peptides containing N-terminal formylmethonine are potent chemoattractants for neutrophils (53, 62), and Somerville et al. (54) have shown that formylated delta-hemolysin from S. aureus was significantly more attractive to neutrophils than the deformylated delta-hemolysin was.

Several known extracellular proteases were detected (Fig. 3c). The protein profiles of both staphopain (scpA; lSAR2001) and the cysteine protease (sspB; SAR1021) were similar, with quantities of protein increasing after 6 and 12 h of growth and decreasing by 24 h of growth (Fig. 3c). The protein levels for the glutamyl endopeptidase (sspA; SAR1022), also known as the V8 serine protease, and the zinc metalloproteinase aureolysin (aur; SAR2716) were moderate throughout growth with a slight to moderate decrease by 24 h (Fig. 3c). A number of other proteases were detected (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), including three (splC [SAR1906], splD [SAR1905], and splE [SAR1902]) of the six serine protease-like (Spl) proteins whose genes were originally found in the spl operon of S. aureus RN6390 (50). The protein databases for S. aureus (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/integr8/) show that one or more gene members of the spl operon are present in all of the sequenced S. aureus strains. Only S. aureus COL, USA300, Newman, and NCTC 8325 contain all six genes (data not shown).

Other known extracellular proteins detected in spent media of S. aureus UAMS-1 included two proteins identified as having phosphodiesterase function (glpQ [SAR0921] and plc [SAR0105]), the extracellular fibrinogen-binding protein (efb [SAR1130]), the peptidoglycan hydrolase (lytM [SAR0273]), and two alleles for hyaluronate lyase (hysA1 and hysA2 [SAR1892 and SAR2292, respectively]) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

Fifteen proteins ranging from 10.4 to 69.2 kDa were identified as putative exported proteins (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). One (Q6GJK9, aaa [sle1]) of these proteins has been identified as an N-acetylmuramyl-l-alanine amidase and is involved with cell-to-cell separation (33) and adherence to the extracellular matrix proteins, fibrinogen, fibronectin, and vitronectin (31). A second protein (Q6GED5) was originally identified as an immunodominant staphylococcal antigen (IsaA) reactive with antisera taken from patients with MRSA sepsis (39). This protein was later shown to have a C-terminal domain with sequence similarity to the soluble lytic transglycosylase (Slt70) of Escherichia coli and found in spent media but also in the cell wall, primarily within the septal region of the cell (52).

All but two of these putative exported proteins contain a putative signal peptide supporting their identification as a secreted protein (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The protein expression profiles for 10 of the most abundant of these proteins detected demonstrate a wide variety of expression profiles, which includes the expression profiles for Q6GEM4 and Q6GIA6 (Fig. 3d) whose expression by 24 h ranked them among some of the most abundant extracellular proteins detected (Fig. 3d).

(ii) Cell wall-associated proteins detected in spent media isolated from S. aureus UAMS-1 after 3, 6, 12, and 24 h of growth.

A number of proteins detected in spent media and classified as cell wall-associated proteins by PSORTb did not contain a recognizable putative cell wall anchor motif and substrate for either sortase A or sortase B (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). These included a precursor of the foldase protein (prsA; SAR1932), a cell surface elastin-binding protein (ebpS; SAR1489), a putative cell wall hydrolase (lytN; SAR1223), and the very large surface-anchored protein known as the extracellular matrix-binding protein homolog (ebh; SAR1447). EbpS contains two membrane-spanning domains and has been shown to be associated with the membrane by using PhoA and LacZ fusions (17). It is the only known S. aureus adhesion protein associated with the cytoplasmic membrane. Ebh has both a membrane-spanning domain and a putative peptidoglycan-binding repeat, indicating an association with either the cytoplasmic membrane or the cell wall or both (12).

There are 23 known S. aureus proteins covalently attached to the cell wall by sortase A (57) and one protein (IsdC) attached by sortase B (41). Twelve of these proteins were detected in this study (see Table S2 in the supplemental material), and the genes for five (FnBPB, Pls, SasG/Aap, SasK, and SasL) of the remaining covalently attached proteins known to exist among the sequenced strains of S. aureus are not on the S. aureus Sanger 252 genome (57) and thus, cannot be identified in S. aureus UAMS-1 using the protein database for Sanger 252. The remaining covalently attached proteins (SdrD, SdrE, SasB, SasC, SasI/HarA/IsdH, and IsdC) whose genes were on the S. aureus Sanger 25 2genome were not detected in S. aureus UAMS-1. The expression profiles, with respect to growth phase, of five cell wall-associated proteins containing a signal sequence and a cell wall anchor motif are displayed in Fig. 4. Four out of five of these proteins were observed to increase in abundance after 6 and 12 h of growth but decrease precipitously by 24 h. Protein levels for the collagen-binding protein (cna; Q6GDB2) were essentially the same throughout growth (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Normalized peptide number of a select group of cell wall-associated proteins detected in spent media isolated from S. aureus UAMS-1 after 3, 6, 12, and 24 h of growth.

The expression profiles observed for extracellular (Fig. 3) and cell wall-associated (Fig. 4) proteins are indicative of what is known regarding in vitro, growth phase-dependent regulation of virulence factors in S. aureus (reviewed in references 11, 46, and 49). This growth phase-dependent, coordinated regulation is primarily attributed to the agr quorum-sensing system; as cell density increases, expression of cell wall-associated proteins decreases with a subsequent increase in expression of extracellular proteins (reviewed in references 11, 46, and 49).

(iii) Cell membrane-associated proteins detected in spent media isolated from S. aureus UAMS-1 after 3, 6, 12, and 24 h of growth.

Thirty-seven proteins were classified as cell membrane-associated proteins using both PSORTb (23) and UniProt Knowledgebase (60) assessments (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). All but seven contain at least one transmembrane internal helix and 13 proteins contain three or more transmembrane internal helices, a prerequisite for identification as a cell membrane-associated protein by PSORTb analysis (23). It is known that the positively charged amino acids lysine and arginine are typically found in the hydrophilic regions of membrane-associated proteins and are not found in proteins with transmembrane helices (35). Therefore, the limited number of cell membrane-associated proteins detected in this study is most likely due to a lack of efficient trypsin digestion of many of these proteins that would result in peptides suitable for mass spectrometric detection (20). No solubilization techniques, such as techniques using detergents and/or organic solvents, were employed in this study to specifically isolate membrane proteins.

Proteins identified from spent media isolated from early exponential growth of S. aureus UAMS-1 and its regulatory mutants.

In order to generate extracellular protein profiles for S. aureus UAMS-1 and its sarA, agr, and sarA agr, regulatory mutants, spent media isolated after 3 hours of growth (Fig. 1) were concentrated and proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE prior to trypsin digestion and subsequent analysis by nanoLC-MS-MS. Initially, product ion data were searched against the S. aureus MW2, Mu50, and Sanger 252 (EMRSA-16) protein databases (data not shown). The search against the S. aureus Sanger 252 protein database gave the highest (albeit modest) number of identified proteins, 357, 403, 413, and 415 for S. aureus UAMS-1, the sarA mutant, the agr mutant, and the sarA agr mutant, respectively (Table 2). The overall mean and median numbers of peptides per protein were 9.6 ± 1.1 and 6.2 ± 0.5, respectively (Table 2). These data are consistent with the data of Cassat et al. (9) who used a comprehensive microarray-based analysis that included the presence or absence of 2,224 genes to show that, among the sequenced strains of S. aureus, strain UAMS-1 was most closely related to S. aureus Sanger 252 (EMRSA-16). Because of the relatedness of UAMS-1 to Sanger 252 (9), product ion data generated for the remaining experiments were searched only against the S. aureus Sanger 252 database.

TABLE 2.

Peptide statistics for spent media in which S. aureus UAMS-1 and its sarA, agr, and sarA agr regulatory mutants had grown for 3 h

| Strain | No. of proteins | No. of unique peptides | Total no. of peptides | Mean no. of unique peptides/protein | Median no. of unique peptides/protein |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UAMS-1 | 357 | 2,955 | 5,953 | 8.3 | 6 |

| sarA mutant | 403 | 4,412 | 10,190 | 10.9 | 7 |

| agr mutant | 413 | 3,789 | 8,745 | 9.2 | 6 |

| sarA agr mutant | 415 | 4,101 | 9,383 | 9.9 | 6 |

The NPN was used successfully to assess the relative abundance of proteins found in spent media isolated from S. aureus UAMS-1 after 3, 6, 12, and 24 h of growth. We next wanted to determine whether the NPN could also be used to determine relative protein abundance between strains, in this case, between UAMS-1 and its sarA, agr, and sarA agr regulatory mutants. To do so, we identified proteins from spent media isolated from S. aureus UAMS-1 and its regulatory mutants after 3 h of growth. Proteins were classified with respect to their location, and as for S. aureus UAMS-1, the majority of proteins isolated from the mutants were cytoplasmic. Collectively, 565 unique proteins were identified, and 382 (68%) were determined to be cytoplasmically located, 43 (8%) were extracellular or secreted proteins, 16 (3%) were cell wall associated, 17 (3%) were localized to the membrane, and the locations of 107 (19%) proteins could not be determined. Manual submission of the accession numbers to the UniProt Knowledgebase system (60) for the locations of proteins that could not be determined using the PSORTb software (23) resulted in identifying a probable location for 77 proteins. A combination of both programs showed 442 (78%) proteins were cytoplasmic, 55 (10%) were extracellular or secreted, 15 (3%) were cell wall associated, and 23 (4%) were localized to the membrane, and the locations of only 30 (5%) remained unknown.

(i) Extracellular proteins detected in spent media isolated from S. aureus UAMS-1 and its regulatory mutants after 3 hours of growth.

Proteins classified as extracellular are listed in Table S4 in the supplemental material. A select number of known proteins that were classified as extracellular and detected from spent media isolated from S. aureus UAMS-1 and its regulatory mutants after 3 hours of growth is displayed in Fig. 5. In all strains, the most abundant proteins were bifunctional autolysin (atl; SAR1026), IgG-binding protein (sbi; SAR2508), immunodominant staphylococcal antigen A precursor (isaA; SAR2650), staphopain protease (scpA; SAR2001), thermonuclease (nuc; SAR0847), and the zinc metalloproteinase aureolysin (aur; SAR2717) (Fig. 5) (see Table S4 in the supplemental material). Several extracellular proteins were in low abundance. Examples follow: 1-phosphatidylinositol phosphodiesterase (plc; SAR0105); fibrinogen-binding protein (fib [efb]; SAR1130); components A (hlgA; SAR2509), B (hlgB; SAR2511), and C (hlgC; SAR2510) of gamma-hemolysin; glutamyl endopeptidase (sspA; SAR1022); hyaluronate lyase 1 (hysA1; SAR1892); lipase 1 (geh [lip1]; SAR2753) and 2 (geh [lip2]; SAR0317); the putative leukocidin F (luk; SAR2107) and S (luk; SAR2108) subunits; and staphylokinase (sak; SAR2039) (Fig. 5). The low abundance of these proteins is most likely due to their expression being elevated only when cells reach the postexponential phase of growth (46). The effect of sarA and/or agr on protein abundance was observed by the increase in cysteine protease (sspB; Q6GI35), glutamyl endopeptidase (sspA; Q6GI34), staphopain (scpA; Q6GFE8), and the zinc metalloproteinase aureolysin (aur; Q6GDG5) in the sarA and sarA agr mutants compared to the wild type, UAMS-1 (Fig. 5). This is in agreement with earlier reports that demonstrated that proteolytic activity on azocasein (3) and steady-state message levels for cysteine protease, glutamyl endopeptidase, and aureolysin (8) were significantly increased in the sarA mutant than in the UAMS-1 parent and the agr mutant. While it could not be determined directly for the agr mutant with respect to proteolytic activity, the reduced activity seen on azocasein for the sarA agr mutant compared to the sarA mutant is an indication of the positive effect of agr on proteases (3). A similar effect was observed in this study except that only protein abundance was measured (Fig. 5). Other proteins that were negatively affected by sarA compared to the UAMS-1 parent in this study included 1-phosphatidylinositol phosphodiesterase (plc; Q6GKK3), bifunctional autolysin (atl; Q6GI31), hyaluronate lyase 1 (hysA1; Q6GFP8) and 2 (hysA2; Q6GEM7), and thermonuclease (nuc; Q6GIK1), an effect that was also observed in the sarA agr mutant (Fig. 5). These data are in agreement with Cassat et al. (8) who demonstrated that steady-state message levels for 1-phosphatidylinositol phosphodiesterase (plc), hyaluronate lyase 1 (hysA1) and 2 (hysA2), and thermonuclease (nuc) were elevated in the sarA mutant than in UAMS-1.

FIG. 5.

NPN of a select group of known extracellular proteins detected in spent media isolated from S. aureus UAMS-1 and its sarA, agr, and sarA agr regulatory mutants after 3 h of growth.

A number of extracellular proteins showed decreased abundance in the sarA mutant compared to UAMS-1 (Fig. 5). These included fibrinogen-binding protein (fib[efb]; Q6GHS9), gamma-hemolysin component B (hlgB; Q6GE12), IgG-binding protein (sbi; Q6GE15), immunodominant staphylococcal antigen A (isaA; Q6GDN1), lipase 1 (geh [lip1]; Q6GDD3) and 2 (geh [lip2]; Q6GJZ6), the putative leukocidin F (lukF; Q6GF50) and S (lukF; Q6GF49) subunits, and staphylocoagulase (coa; Q6GK85). A few of these proteins showed only marginal differences, which may not reflect regulation. One exception was the immunodominant staphylococcal antigen A (isaA; Q6GDN1). Protein abundance for this protein and that of the IgG-binding protein (sbi; Q6GE15) decreased in the sarA mutant (Fig. 5). The immunodominant staphylococcal antigen A protein was barely detectable in the sarA mutant compared to the wild type, UAMS-1 (Fig. 5). Two independent studies have indicated a regulatory role for sarA in expression of the immunodominant staphylococcal antigen A protein (51, 67). One study demonstrated by 2D-PAGE analysis of spent media isolated from S. aureus RN6390 that the protein was drastically reduced in the sarA mutant (67). The second study (51) has identified a potential SarA binding region (56) upstream of the −35 promoter region and downstream of a potential binding site for the YycF regulatory protein, a member of the two-component regulatory system, YycG/YycF (18).

The effect of agr on the abundance of known proteins was somewhat surprising. While the protein abundance of a number of extracellular proteins (gamma-hemolysin components A, B, and C, and lipase 1 and 2) was lower in the agr mutant than in UAMS-1, the overall protein levels for all four strains were low (Fig. 5). However, this is most likely due to the time in growth (3 h), when RNAIII expression is minimal (61). In contrast, protein abundance for bifunctional autolysin (atl; Q6GI31), enterotoxin type A (sea; Q6GFA8), IgG-binding protein (sbi; Q6GE15), immunodominant staphylococcal antigen A (isaA; Q6GDN1), and staphylocoagulase (coa; Q6GK85) was higher in the agr mutant than in the wild type, UAMS-1 (Fig. 5). This is particularly apparent with the IgG-binding protein and the immunodominant staphylococcal antigen A protein where the abundance of these proteins is some of the highest detected from spent media isolated after 3 hours of growth (Fig. 5). In the case of the IsaA protein, three independent studies have shown either transcriptionally (19) or proteomically (34, 66) that isaA (IsaA) expression is significantly increased in an agr mutant background. These data suggest that even among extracellular proteins that are secreted into the environment, certain proteins are more tightly controlled by the agr regulon than others.

(ii) Cell wall-associated proteins detected in spent media isolated from S. aureus UAMS-1 and its regulatory mutants after 3 hours of growth.

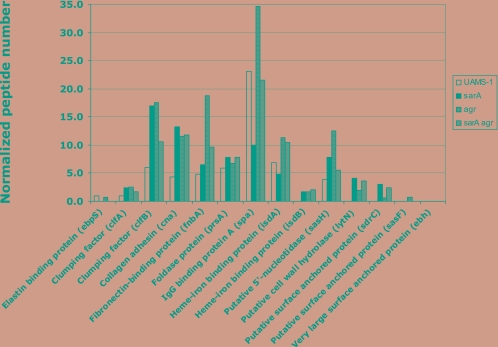

Most of the cell wall-associated proteins found in spent media isolated from strain UAMS-1 and its regulatory mutants after 3 hours of growth were shown to be more abundant in both the sarA and agr mutants than in UAMS-1 (Fig. 6) (see Table S5 in the supplemental material). These included clumping factor A (clfA; Q6GIK4) and B (clfB; Q6GDH2), collagen adhesion (cna; Q6GDB2), fibronectin-binding protein (fnbA; Q6GDU5), foldase protein (prsA; Q6GFL5), heme-iron-binding protein (isdB; Q6GHV7), putative 5′-nucleotidase (sasH; Q6GKS2), putative cell wall hydrolase (lytN; Q6GHI8), and a putative surface-anchored protein (sdrC; Q6GJA7) (Fig. 6). The sarA agr mutant exhibited an increase in protein abundance as well (Fig. 6). However, the effect of the double mutation was not additive. A similar increase in protein abundance was also observed for the IgG-binding protein A (spa; Q6GKJ4) in the agr mutant and for the heme-iron-binding protein (isdA; Q6GHV6) in the sarA mutant; the levels for these two proteins were reduced (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

NPN of known cell wall-associated proteins detected in spent media isolated from S. aureus UAMS-1 and its sarA, agr, and sarA agr regulatory mutants after 3 h of growth.

(iii) Cytoplasmic membrane proteins detected in spent media isolated from S. aureus UAMS-1 and its regulatory mutants after 3 hours of growth.

While several differences in protein abundance were detected for S. aureus UAMS-1 and its regulatory mutants after 3 hours of growth, the levels of proteins identified as cytoplasmic membrane proteins were quite low, with the exception of β-lactamase (blaZ; Q6GFV5) and sulfatase (Q6GIS3) (see Table S6 in the supplemental material). This was also the case with UAMS-1 when cytoplasmic membrane proteins were identified from spent media isolated after 3, 6, 12, and 24 h of growth (see Table S3 in the supplemental material).

Proteins identified from cell lysates prepared from exponentially growing S. aureus UAMS-1 and its regulatory mutants.

The majority (∼75%) of proteins identified from spent media isolated from S. aureus UAMS-1 at various points in growth, as well as spent media isolated from S. aureus UAMS-1 and its regulatory mutants at 3 h of growth were cytoplasmic (see Table S7 in the supplemental material). To investigate the nature of the presence of a large percentage of cytoplasmic proteins in spent media, we isolated spent media and the corresponding cell lysates from S. aureus UAMS-1 and its regulatory mutants after 3 hours of growth. We reasoned that the presence of cytoplasmic proteins in spent media was most likely due to an undetectable (Fig. 1) number of cells undergoing lysis. If cell lysis were occurring, then the most abundant cytoplasmic proteins found in cell lysates should be among those that are the most abundant in spent media.

Proteins in cell lysates and their corresponding spent media were resolved by SDS-PAGE. The SDS-PAGE cell lysate protein profiles for parent and mutant strains were similar by visual examination (Fig. 2c). Gels were processed, and proteins were digested and analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. Product ion data (no single peptides included) allowed for the identification of 1,016, 797, 979, and 946 proteins for S. aureus UAMS-1 lysates and lysates from the sarA, agr, and sarA agr mutants, respectively. Utilizing the NPN for each protein, the 50 most abundant cytoplasmic proteins from cell lysates were compared to the 50 most abundant cytoplasmic proteins from spent media (data not shown). Only 64% (32/50) of the proteins detected in cell lysates were common to all four strains, while only an average of 7% (4.2/62 ± 0.96/62) of proteins were unique to any one strain (data not shown). Likewise, only 44% (22/50) of the cytoplasmic proteins detected in spent media were common to all four strains, while only an average of 11% (7.8/72 ± 0.96/72) of proteins were unique to any one strain (data not shown). When cytoplasmic proteins detected in cell lysates for each strain were compared to their corresponding spent media, an average of only 54.5% (27.2/50 ± 1.7/50) of the proteins detected in cell lysates were also detected in spent media (data not shown). We would expect a much higher percentage of cytoplasmic proteins to be detected in spent media if cell lysis were actually the contributing factor. While we believe the presence of so many cytoplasmically located proteins in spent media is probably due to cell lysis, it is difficult to use this comparison in support of such a conclusion when only half of the most abundant proteins detected in cell lysates were detected in spent media.

Fourteen cytoplasmic proteins were consistently present in cell lysates and spent media for all strains, and their abundance in spent media consistently ranked them as some of the most abundant proteins of the cytoplasmically located proteins found in spent media (data not shown). Of these, elongation factor Tu (EF-Tu; Q6GJC0), glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) 1 (Q6GIL8), inosine-5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMDH; Q6GJQ7), and enolase (En; Q6GIL4) have been shown to be associated with the cell surfaces of certain gram-positive bacteria and to bind the extracellular matrix proteins, plasminogen/plasmin and laminin, and the serum iron-binding protein, transferrin (reviewed in reference 47). For example, in S. aureus, the GAPDH protein was shown to be expressed on the cell surface and to bind transferrin and plasmin (43, 44). More recently, Taylor and Heinrichs (58) used purified GAPDH and were unable to demonstrate transferrin binding by GAPDH although the protein retained GAPDH activity. Whether these differences between two independent laboratories are related to strain differences is not known. However, Goji et al. (26) isolated two proteins from the cell surface of a bovine clinical mastitis isolate of S. aureus that exhibited GAPDH activity and amino acid similarities to the GapB and GapC proteins in human strains of S. aureus. The proteins in the mastitis isolate were distinguishable by both their GAPDH activities and their abilities to bind transferrin and plasmin. The genes for GapB and GapC were conserved among 11 other mastitis isolates, and the GapC protein was found on the surfaces of all strains (26).

It has also been shown that activation of plasminogen to plasmin by staphylokinase is not only protected from the inhibitor, α2-antiplasmin, but the activation is enhanced in the presence of S. aureus cells and solubilized staphylococcal cell walls (45). It was shown that these putative plasminogen-binding proteins were IMP dehydrogenase, α-enolase, and ribonucleotide reductase subunit 2 (45). α-Enolase has also been shown to bind laminin on the surface of S. aureus (7). In Lactobacillus johnsonii, elongation factor Tu was shown to be associated with the cell wall and to facilitate attachment of this bacterium to human intestinal cells and mucin (27). Whether or not the detection of certain cytoplasmically located proteins in spent media in the present study is an indication of proteins with a secondary function associated with the cell surface will require further study. This is particularly true, given the increase in the number of reports of proteins known to have dual function (47).

Concluding perspectives.

Proteins in spent media and cell lysates were resolved by 1D-PAGE and identified using tryptic peptides analyzed by nanoLC-MS-MS. Total spectral count data were an indication of protein abundance and were used to generate a protein profile for S. aureus UAMS-1 after 3, 6, 12, and 24 h of growth as well as for UAMS-1 and its regulatory mutants during exponential growth. Generally, proteins known to be cell wall associated were more abundant early in growth, while proteins known to be secreted into the surrounding milieu were more abundant late in growth. The detection of extracellular proteins known to be regulated by the global regulators (sarA and agr) displayed levels in accordance with what is known regarding these regulators. Surprisingly, a large percentage of proteins detected in spent media during early exponential phase of growth were cytoplasmically located. In all likelihood, the presence of these proteins in spent media is due to cell lysis, although a number of these proteins were some of the most abundant of the cytoplasmically located proteins detected in spent media and have been shown by others to be associated with the cell surface where they exhibit a secondary function.

Collectively, the analysis yielded a total of 1,263 unique proteins identified with at least two unique peptides. Based on reversed database searching, single-peptide matches scoring greater than or equal to 45 yield a FDR of <0.1%, and if we include those that were identified with only one peptide, we obtain a total of 1,341 proteins. This represents approximately 50% of the coding capacity of S. aureus Sanger 252 and the highest reported number of proteins in S. aureus so far using 1D-PAGE and nanoLC-MS-MS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant awarded to M.E.H., R.D.E., and R.C.J. by the National Center for Toxicological Research of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

We are indebted to Carl Cerniglia, Huizhong Chen, Chris Elkins, John Iandolo, Seong-Jae Kim, and Mark Smeltzer for careful evaluation of the manuscript.

The views presented in this article do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 6 June 2008.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beaudet, R., J. G. Bisaillon, S. A. Saheb, and M. Sylvestre. 1982. Production, purification, and preliminary characterization of a gonococcal growth inhibitor produced by a coagulase-negative staphylococcus isolated from the urogenital flora. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 22277-283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergonier, D., R. de Crémoux, R. Rupp, G. Lagriffouk, and X. Berthelot. 2003. Mastitis of dairy small ruminants. Vet. Res. 34689-716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blevins, J. S., K. E. Beenken, M. O. Elasri, B. K. Hurlburt, and M. S. Smeltzer. 2002. Strain-dependent differences in the regulatory roles of sarA and agr in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 70470-480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bohach, G. A., M. M. Dinges, D. T. Mitchell, D. H. Ohlendorf, and P. M. Schlievert. 1997. Exotoxins, p. 83-111. In K. B. Crossley and G. L. Archer (ed.), The staphylococci in human disease. Churchill Livingstone, New York, NY.

- 5.Bronner, S., H. Monteil, and G. Prévost. 2004. Regulation of virulence determinants in Staphylococcus aureus: complexity and applications. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 28183-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burts, M. L., W. A. Williams, K. DeBord, and D. M. Missiakas. 2005. EsxA and EsxB are secreted by an ESAT-6-like system that is required for the pathogenesis of Staphylococcus aureus infections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1021169-1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carneiro, C. R. W., E. Postol, R. Nomizo, L. F. L. Reis, and R. R. Brentani. 2004. Identification of enolase as a laminin-binding protein on the surface of Staphylococcus aureus. Microbes Infect. 6604-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cassat, J., P. M. Dunman, E. J. Murphy, S. J. Projan, K. E. Beenken, K. J. Palm, S.-J. Yang, K. C. Rice, K. W. Bayles, and M. S. Smeltzer. 2006. Transcriptional profiling of a Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolate and its isogenic sarA and agr mutants reveals global differences in comparison to the laboratory strain RN6390. Microbiology 1523075-3090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cassat, J. E., P. M. Dunman, F. McAleese, E. Murphy, S. J. Projan, and M. S. Smeltzer. 2005. Comparative genomics of Staphylococcus aureus musculoskeletal isolates. J. Bacteriol. 187576-592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang, S., D. M. Sievert, J. C. Hageman, M. L. Boulton, F. C. Tenover, F. P. Downes, S. Shah, J. T. Rudrik, G. R. Pupp, W. J. Brown, D. Cardo, and S. K. Fridkin for the Vancomycin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Investigative Team. 2003. Infection with vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus containing the vanA resistance gene. N. Engl. J. Med. 3481342-1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheung, A. L., A. S. Bayer, G. Zhang, H. Gresham, and Y.-Q. Xiong. 2004. Regulation of virulence determinants in vitro and in vivo in Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 401-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clarke, S. R., L. G. Harris, R. G. Richards, and S. J. Foster. 2002. Analysis of Ebh, a 1.1-megadalton cell wall-associated fibronectin-binding protein of Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 706680-6687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diekema, D. J., M. A. Pfaller, F. J. Schnitz, J. Smayevsky, J. Bell, R. N. Jones, M. Beach, and the SENTRY Participants Group. 2001. Survey of infections due to Staphylococcus species: frequency of occurrence and antimicrobial susceptibility of isolates collected in the United States, Canada, Latin America, Europe, and the western Pacific region for the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program, 1997-1999. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32(Suppl. 2)S114-S132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dinges, M. M., P. M. Orwin, and P. M. Schlievert. 2000. Exotoxins of Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1316-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donvito, B., J. Etienne, L. Denoroy, T. Greenland, Y. Benito, and F. Vandenesch. 1997. Synergistic hemolytic activity of Staphylococcus lugdunensis is mediated by three peptides encoded by a non-agr genetic locus. Infect. Immun. 6595-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donvito, B., J. Etienne, T. Greenland, C. Mouren, V. Delorme, and F. Vandenesch. 1997. Distribution of the synergistic haemolysin genes hld and slush with respect to agr in human staphylococci. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 151139-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Downer, R., F. Roche, P. W. Park, R. P. Mecham, and T. J. Foster. 2002. The elastin-binding protein of Staphylococcus aureus (EbpS) is expressed at the cell surface as an integral membrane protein and not as a cell wall-associated protein. J. Biol. Chem. 277243-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dubrac, S., and T. Msadek. 2004. Identification of genes controlled by the essential yycG/yycF two-component system of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 1861175-1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dunman, P. M., E. Murphy, S. Haney, D. Palacios, G. Tucker-Kellogg, S. Wu, E. L. Brown, R. J. Zagursky, D. Shlaes, and S. J. Projan. 2001. Transcriptional profiling-based identification of Staphylococcus aureus genes regulated by the agr and/or sarA loci. J. Bacteriol. 1837341-7353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fischer, F., and A. Poetsch. 2006. Protein cleavage strategies for an improved analysis of the membrane proteome. Proteome Sci. 42. http://www.proteomesci.com/content/4/1/2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fitton, J. E., A. Dell, and W. V. Shaw. 1980. The amino acid sequence of the delta haemolysin of Staphylococcus aureus. FEBS Lett. 115209-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gambus, A., R. C. Jones, A. Sanchez-Diaz, M. Kanemaki, F. van Deursen, R. D. Edmondson, and K. Labib. 2006. GINS maintains association of Cdc45 with MCM in replisome progression complexes at eukaryotic DNA replication forks. Nat. Cell Biol. 8358-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gardy, J. L., M. R. Laird, F. Chen, S. Rey, C. J. Walsh, M. Ester, and F. S. L. Brinkman. 2005. PSORTb v. 2.0: expanded prediction of bacterial protein subcellular localization and insights gained from comparative proteome analysis. Bioinformatics 21617-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giglione, C., M. Pierre, and T. Meinnel. 2000. Peptide deformylase as a target for new generation, broad spectrum antimicrobial agents. Mol. Microbiol. 361197-1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gillaspy, A. F., S. G. Hickmon, R. A. Skinner, J. R. Thomas, C. L. Nelson, and M. S. Smeltzer. 1995. Role of the accessory gene regulator (agr) in pathogenesis of staphylococcal osteomyelitis. Infect. Immun. 633373-3380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goji, N., A. A. Potter, and J. Perez-Casal. 2004. Characterization of two proteins of Staphylococcus aureus isolated bovine clinical mastitis with homology to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Vet. Microbiol. 99269-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Granato, D., G. E. Bergonzelli, R. D. Pridmore, L. Marvin, M. Rouvet, and I. E. Corthésy-Theulaz. 2004. Cell surface-associated elongation factor Tu mediates the attachment of Lactobacillus johnsonii NCC533 (La1) to human intestinal cells and mucins. Infect. Immun. 722160-2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Graves, P. R., and T. A. J. Haystead. 2002. Molecular biologist's guide to proteomics. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 6639-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hébert, G. A., C. G. Crowder, G. A. Hancock, W. R. Jarvis, and C. Thornsberry. 1988. Characteristics of coagulase-negative staphylococci that help differentiate these species and other members of the family Micrococcaceae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 261939-1949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hecker, M., S. Engelmann, and S. J. Cordwell. 2003. Proteomics of Staphylococcus aureus--current state and future challenges. J. Chromatogr. B 787179-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heilmann, C., J. Hartleib, M. S. Hussain, and G. Peters. 2005. The multifunctional Staphylococcus aureus autolysin Aaa mediates adherence to immobilized fibrinogen and fibronectin. Infect. Immun. 734793-4802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Janzon, L., S. Löfdahl, and S. Arvidson. 1989. Identification and nucleotide sequence of the delta-lysin gene, hld, adjacent to the accessory gene regulator (agr) of Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Gen. Genet. 219480-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kajimura, J., T. Fujiwara, S. Yamada, Y. Suzawa, T. Nishida, Y. Oyamada, I. Hayashi, J.-I. Yamagishi, H. Komatsuzawa, and M. Sugai. 2005. Identification and molecular characterization of an N-acetylmuramyl-L-alanine amidase Sle1 involved in cell separation of Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 581087-1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kohler, C., C. von Eiff, G. Peters, R. A. Proctor, M. Hecker, and S. Engelmann. 2003. Physiological characterization of a heme-deficient mutant of Staphylococcus aureus by a proteomic approach. J. Bacteriol. 1856928-6937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kyte, J., and R. F. Doolittle. 1982. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J. Mol. Biol. 157105-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee, K. Y., and T. H. Birkbeck. 1984. In vitro synthesis of the delta-lysin of Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 44434-438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lindsay, J. A., and M. T. G. Holden. 2004. Staphylococcus aureus: superbug, super genome? Trends Microbiol. 112378-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu, H., R. G. Sadygov, and J. R. Yates III. 2004. A model for random sampling and estimation of relative protein abundance in shotgun proteomics. Anal. Chem. 764193-4201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lorenz, U., K. Ohlsen, H. Karch, M. Hecker, A. Thiede, and J. Hacker. 2000. Human antibody response during sepsis against targets expressed by methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 29145-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.MacCoss, M. J., C. C. Wu, H. Liu, R. Sadygov, and J. R. Yates III. 2003. A correlation algorithm for the automated quantitative analysis of shotgun proteomics data. Anal. Chem. 756912-6921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mazmanian, S. K., H. Ton-That, K. Su, and O. Schneewind. 2002. An iron-regulated sortase anchors a class of surface protein during Staphylococcus aureus pathogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 992293-2298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mehlin, C., C. M. Headley, and S. J. Klebanoff. 1999. An inflammatory polypeptide complex from Staphylococcus epidermidis: isolation and characterization. J. Exp. Med. 189907-917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Modun, B., J. Morrissey, and P. Williams. 2000. The staphylococcal transferring receptor: a glycolytic enzyme with novel functions. Trends Microbiol. 8231-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Modun, B., and P. Williams. 1999. The staphylococcal transferring-binding protein is a cell wall glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Infect. Immun. 671086-1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mölkänen, T., J. Tyynelä, J. Helin, N. Kalkkinen, and P. Kuusela. 2002. Enhanced activation of bound plasminogen on Staphylococcus aureus by staphylokinase. FEBS Lett. 51772-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Novick, R. P. 2003. Autoinduction and signal transduction in the regulation of staphylococcal virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 481429-1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pancholi, V., and G. S. Chhatwal. 2003. Housekeeping enzymes as virulence factors for pathogens. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 293391-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Prévost, G., L. Mourey, D. A. Colin, and G. Menestrina. 2001. Staphylococcal pore-forming toxins. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 25753-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Projan, S. J., and R. P. Novick. 1997. The molecular basis of pathogenicity, p. 55-81. In K. B. Crossley and G. L. Archer (ed.), The staphylococci in human disease. Churchill Livingstone, New York, NY.

- 50.Reed, S. B., C. A. Wesson, L. E. Liou, W. R. Trumble, P. M. Schlievert, G. A. Bohach, and K. W. Bayles. 2001. Molecular characterization of a novel Staphylococcus aureus serine protease operon. Infect. Immun. 691521-1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sakata, N., and T. Mukai. 2007. Production profile of the soluble lytic transglycosylase homologue in Staphylococcus aureus during bacterial proliferation. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 49288-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sakata, N., S. Terakubo, and T. Mukai. 2005. Subcellular location of the soluble lytic transglycosylase homologue in Staphylococcus aureus. Curr. Microbiol. 5047-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schiffmann, E., B. A. Corcoran, and S. M. Wahl. 1975. N-formylmethionyl peptides as chemoattractants for leucocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 721059-1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Somerville, G. A., A. Cockayne, M. Dürr, A. Peschel, M. Otto, and J. M. Musser. 2003. Synthesis and deformylation of Staphylococcus aureus δ-toxin are linked to tricarboxylic acid cycle activity. J. Bacteriol. 1856686-6694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Srinivasan, A., J. D. Dick, and T. M. Perl. 2002. Vancomycin resistance in staphylococci. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15430-438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sterba, K. M., S. Mackintosh, J. S. Blevins, B. K. Hurlburt, and M. S. Smeltzer. 2003. Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus SarA binding sites. J. Bacteriol. 1854410-4417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stranger-Jones, Y. K., T. Bae, and O. Schneewind. 2006. Vaccine assembly from surface proteins of Staphylococcus aureus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10316942-16947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Taylor, J. M., and D. E. Heinrichs. 2002. Transferrin binding in Staphylococcus aureus: involvement of a cell wall-anchored protein. Mol. Microbiol. 431603-1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tenover, F. C., L. M. Weigel, P. C. Appelbaum, L. K McDougal, J. Chaitram, S. McAllister, N. Clark, G. Killgore, C. M. O'Hara, L. Jevitt, J. B. Patel, and B. Bozdogan. 2004. Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolate from a patient in Pennsylvania. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48275-280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.The UniProt Consortium. 2007. The universal protein resource (UniProt). Nucleic Acids Res. 35D193-D197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vandenesch, F., J. Kornblum, and R. P. Novick. 1991. A temporal signal, independent of agr, is required for hla but not spa transcription in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 1736313-6320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang, R., K. R. Braughton, D. Kretschmer, T.-H. L. Bach, S. Y. Queck, M. Li, A. D. Kennedy, D. W. Dorward, S. J. Klebanoff, A. Peschel, F. R. DeLeo, and M. Otto. 2007. Identification of novel cytolytic peptides as key virulence determinants for community-associated MRSA. Nat. Med. 131510-1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Watson, D. C., M. Yaguchi, J.-G. Bisaillon, R. Beaudet, and R. Morosoli. 1988. The amino acid sequence of a gonococcal growth inhibitor from Staphylococcus haemolyticus. Biochem. J. 25287-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Whitener, C. J., S. Y. Park, F. A. Browne, L. J. Parent, K. Julian, B. Bozdogan, P. C. Appelbaum, J. Chaitram, L. M. Weigel, J. Jernigan, L. K. McDougal, F. C. Tenover, and S. K. Fridkin. 2004. Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the absence of vancomycin exposure. Clin. Infect. Dis. 381049-1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yates, J. R. 2004. Mass spectral analysis in proteomics. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 33297-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ziebandt, A.-K., H. Weber, J. Rudolph, R. Schmid, D. Höper, S. Engelmann, and M. Hecker. 2001. Extracellular proteins of Staphylococcus aureus and the role of SarA and σB. Proteomics 1480-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ziebandt, A.-K., D. Becher, K. Ohlsen, J. Hacker, M. Hecker, and S. Engelmann. 2004. The influence of agr and σB in growth phase dependent regulation of virulence factors in Staphylococcus aureus. Proteomics 43034-3047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.