Abstract

The RNA-dependent RNA polymerase L protein of vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) elicits GTPase and RNA:GDP polyribonucleotidyltransferase (PRNTase) activities to produce a 5′-cap core structure, guanosine(5′)triphospho(5′)adenosine (GpppA), on viral mRNAs. Here, we report that the L protein produces an unusual cap structure, guanosine(5′)tetraphospho(5′)adenosine (GppppA), that is formed by the transfer of the 5′-monophosphorylated viral mRNA start sequence to GTP by the PRNTase activity before the removal of the γ-phosphate from GTP by GTPase. Interestingly, GppppA-capped and polyadenylated full-length mRNAs were also found to be synthesized by an in vitro transcription system with the native VSV RNP.

The 5′-terminal cap structure (m7G[5′]ppp[5′]N-), in which 7-methylguanosine (m7G) is linked to the initiator nucleoside of mRNA through the 5′-5′ triphosphate bridge, is cotranscriptionally formed by a series of enzymatic steps and plays essential roles in various stages of mRNA metabolism, including translation and stability (reviewed in references 3, 6, and 10). For conventional mRNA capping enzymes (CEs) of all known eukaryotes, some DNA viruses (e.g., vaccinia virus), and double-strand RNA viruses (e.g., reovirus and rotavirus), the 5′-triphosphate-ended nascent pre-mRNA (pppN-) is processed into the 5′-diphosphate-end (ppN-) by RNA 5′-triphosphatase (RTPase) and then capped with a GMP moiety of GTP by GTP:RNA guanylyltransferase (GTase) to produce the cap core structure (Gp-ppN-) (6, 10). In striking contrast, for vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) (a prototype nonsegmented negative-strand RNA virus belonging to the Rhabdoviridae family in the order Mononegavirales), the GDP moiety of GTP is incorporated into the cap core structure (Gpp-pA-) formed on in vitro viral mRNAs (1, 2). We have recently discovered that the cap core structure of VSV mRNAs is synthesized by a novel mechanism involving the stepwise activity of GTPase, followed by RNA:GDP polyribonucleotidyltransferase (PRNTase), and both activities are elicited by the multifunctional RNA-dependent RNA polymerase L protein (8). At the first step of VSV mRNA cap formation, the GTPase activity of the VSV L protein removes the γ-phosphate from GTP to yield GDP, which is in turn used as an RNA acceptor (8). At the second step, the PRNTase activity of the L protein transfers the 5′-monophosphorylated RNA moiety of a 5′-triphosphorylated RNA with the conserved VSV mRNA start sequence (AACAG) to GDP via a putative covalent enzyme-RNA intermediate to form a Gpp-pA-capped RNA (8).

During our analyses of this cap structure formed by the recombinant L protein as well as the VSV RNP with [α-32P]GTP and the 5′-triphosphorylated AACAG oligoRNA substrate (8), we routinely observed a distinctly separate nuclease P1 and alkaline phosphatase-resistant radioactive product, albeit of significantly lower intensity, migrating slower than the predominant cap structure on a polyethyleneimine (PEI)-cellulose thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plate. In this study, we analyzed the putative radioactive product and found that the L protein produces yet another unique caplike structure, identified as guanosine(5′)tetraphospho(5′)adenosine (GppppA), on the RNA substrate as a minor product by novel RNA:GTP PRNTase activity. Furthermore, we demonstrate that a fraction of in vitro transcripts synthesized by the VSV RNP also routinely contain the GppppA cap structure.

The in vitro capping assay was carried out (8) at 30°C for 2 h in 10 μl of the VSV capping buffer containing 0.5 mM MnCl2, indicated concentrations of [α-32P]GTP or GDP (100 to 200 cpm/fmol), 5 μM pppApApCpApG, and 50 ng of the purified recombinant VSV L protein (a carboxyl-terminal octahistidine-tagged form purified from baculovirus-infected Sf21 cells similar to that described by Ogino and Banerjee [8]). After treatment of the reaction mixtures with 1 unit of calf intestine alkaline phosphatase (CIAP; Roche Molecular Biochemicals) in the presence of 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5) at 37°C for 15 min, the RNA products were purified as described previously (8). The purified RNA products were digested with 0.3 unit of nuclease P1 (USBiological or Sigma), and then digests were analyzed by PEI-cellulose TLC with 0.4 M ammonium sulfate, followed by autoradiography.

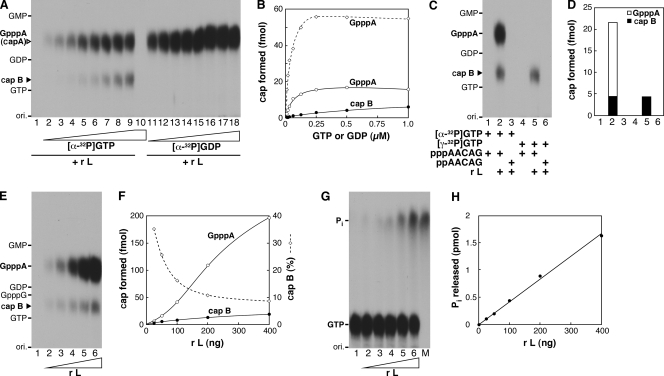

First, we investigated the effects of concentrations of GTP or GDP on cap formation (Fig. 1A and B). As shown in Fig. 1A (lanes 2 to 9), a major product (referred to as cap A) was produced along with a minor caplike structure (referred to as cap B) with GTP in a concentration-dependent manner. The major product (cap A) has been previously identified as guanosine(5′)triphospho(5′)adenosine (GpppA) (8). GpppA production reached a plateau at 0.25 μM GTP, whereas cap B formation was facilitated with increasing concentrations of GTP up to at least 1 μM. When [α-32P]GDP was used as the substrate (Fig. 1A, lanes 11 to 18), the activity of GpppA formation was increased to the maximum level with 0.25 μM GDP, which was 3.6-fold higher than that with 0.25 μM GTP. Interestingly, cap B could not be synthesized with GDP.

FIG. 1.

Formation of a caplike structure by the VSV L protein. (A) The recombinant L protein (r L) (50 ng) was incubated with increasing concentrations (7.8 nM to 1 μM) of [α-32P]GTP (lanes 2 to 9) or [α-32P]GDP (lanes 11 to 18) in the presence of pppApApCpApG. Nuclease P1 and alkaline phosphatase-resistant products were analyzed by PEI-cellulose TLC with 0.4 M ammonium sulfate, followed by autoradiography. The positions of the origin (ori.) and standard marker compounds, visualized under UV light at a wavelength of 254 nm, are indicated on the left. The positions of GpppA (cap A) and cap B are shown by open and filled arrowheads, respectively. Lane 1 indicates no [α-32P]GTP or [α-32P]GDP. Lane 10 shows no enzyme with 1 μM [α-32P]GTP. (B) Amounts of GpppA (open symbols) and cap B (filled symbols) formed in the presence of various concentrations of [α-32P]GTP (circles) or [α-32P]GDP (diamonds) were determined by counting the 32P radioactivities incorporated into the respective bands on the TLC plate as described for panel A. (C) The recombinant L protein (50 ng) was incubated with the 5′-tri (ppp)- or di (pp)-phosphorylated AACAG RNA in the presence of 0.5 μM [α-32P]GTP or [γ-32P]GTP as indicated. The cap structures formed were analyzed as for panel A. Lanes 1 and 4 indicate no enzyme. (D) Amounts of GpppA (open column) and cap B (filled columns) formed as described for panel C are shown. (E) Increasing amounts of the recombinant L protein (25 to 400 ng) (lanes 2 to 6) were incubated with pppApApCpApG and 0.5 μM [α-32P]GTP. The cap structures formed were analyzed as for panel A. Lane 1 indicates no enzyme. (F) Amounts of GpppA (open circles) and cap B (filled circles) formed as described for panel E are shown. The percentages of cap B in total cap structures (GpppA plus cap B) are shown by diamonds. (G) Increasing amounts of the recombinant L protein (25 to 400 ng) (lanes 2 to 6) were incubated with 0.5 μM [γ-32P]GTP. The samples were analyzed as for panel A. Lane M indicates a digest of [γ-32P]GTP with CIAP to denote the position of Pi. (H) Amounts of 32Pi released as described for panel G are shown.

To analyze the roles of the 5′-terminal phosphate groups of the RNA substrate in cap B formation, we performed in vitro capping reactions with the 5′-triphosphorylated (ppp-) or 5′-diphosphorylated (pp-) AACAG oligoRNA in the presence of 0.5 μM [α-32P]GTP or [γ-32P]GTP (Fig. 1C and D). As in the case of GpppA formation (8), the recombinant L protein used pppApApCpApG (Fig. 1C, lane 2) but not ppApApCpApG (lane 3) as the substrate to produce cap B with [α-32P]GTP. When [γ-32P]GTP and pppApApCpApG were used as substrates, as shown in Fig. 1C (lane 5), only cap B was seen, indicating that GTP and the 5′-triphosphorylated RNA are required to produce cap B, which appears to contain the α- to γ-phosphate groups of GTP. Under the standard conditions using 0.5 μM GTP and 50 μM pppApApCpApG, 50 ng of the recombinant L protein produced 16.6 ± 0.5 fmol of GpppA and 5.1 ± 0.7 fmol of cap B (the mean ± the standard deviation of four independent determinations). Interestingly, the percentages of cap B in total cap structures varied from 35% (0.8 fmol) to 9% (4.6 fmol) with increasing amounts (25 to 400 ng) of the recombinant L protein (Fig. 1E and F). Next, in order to know how much GTP is hydrolyzed by the GTPase activity of the recombinant L protein, 0.5 μM [γ-32P]GTP (5 pmol, 2 × 103 cpm/pmol) was incubated with increasing amounts of the recombinant L protein under the same conditions as those for in vitro RNA capping (Fig. 1G and H). Amounts of [γ-32P]GTP were proportionally decreased along with the release of 32P as Pi by the increasing enzyme amounts. There remained a large portion (66%; 3.3 pmol) of [γ-32P]GTP even in the presence of 400 ng of the L protein.

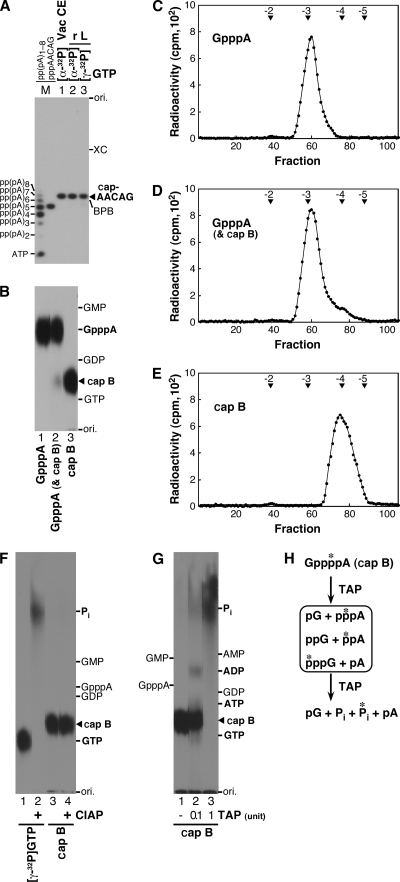

In order to characterize the cap B structure formed by the recombinant L protein, 32P-labeled capped RNAs were synthesized from pppApApCpApG and [α-32P]GTP or [γ-32P]GTP. The recombinant L protein (0.3 μg) was incubated with 10 μM pppApApCpApG and 0.5 μM [α-32P]GTP (1 × 103 cpm/fmol) in 10 μl of the VSV capping buffer as described above. Similarly, a capping reaction was carried out with the recombinant L protein (0.6 μg) and 0.5 μM [γ-32P]GTP (2 × 103 cpm/fmol) in 20 μl of the VSV capping buffer to prepare the 32P-labeled cap B-RNA. Gp*ppApApCpApG (* indicates 32P) was synthesized as a marker by using the vaccinia virus CE (guanylyltransferase; Ambion), as previously described (8). The capped RNAs, synthesized by the L protein in the presence of [α-32P]GTP (Fig. 2A, lane 2) or [γ-32P]GTP (lane 3), comigrated with the marker Gp*ppApApCpApG (lane 1) in a 20% polyacrylamide gel containing 7 M urea. However, when their nuclease P1 digests were analyzed by PEI-cellulose TLC (Fig. 2B), liberated cap B (lanes 2 and 3) migrated slower than GpppA (lanes 1 and 2) on the PEI-cellulose TLC plate, suggesting that cap B is more tightly associated with the PEI anion-exchange resin (probably more negatively charged) than GpppA.

FIG. 2.

Identification of the caplike structure as GppppA. (A) Capped AACAG RNAs were synthesized by the incubation of pppApApCpApG with the vaccinia virus CE (Vac CE) in the presence of [α-32P]GTP (lane 1) or the recombinant L protein (r L) in the presence of [α-32P]GTP (lane 2) or [γ-32P]GTP (lane 3). Aliquots (5 × 102 cpm) of the 32P-labeled capped RNAs were analyzed by urea-20% PAGE, followed by autoradiography. Lane M indicates 32P-labeled poly(A) RNAs [p*p(pA)1-8] and p*ppApApCpApG (8). The positions of the origin (ori.), xylene cyanol FF (XC), bromophenol blue (BPB), and the capped AACAG RNA are shown on the right. (B) Indicated 32P-labeled cap structures (3 × 103 cpm) (lanes 1 to 3) in nuclease P1 digests of the capped AACAG RNAs, corresponding to lanes 1 to 3 in panel A, were analyzed by PEI-cellulose TLC with 0.4 M ammonium sulfate, followed by autoradiography. (C to E) Indicated 32P-labeled cap structures (0.7 × 104 to 1.1 × 104 cpm) as described for panel B, lanes 1 to 3, were analyzed by DEAE Sephacel column chromatography. Radioactivities of the column fractions are shown. Arrowheads indicate the elution positions of marker oligonucleotides with indicated net negative charges. (F) [γ-32P]GTP or 32P-labeled cap B as described for panel B, lane 3, was incubated with or without CIAP. The samples were analyzed by PEI-cellulose TLC with 0.7 M ammonium sulfate. (G) 32P-labeled cap B, as described for panel B, lane 3, was partially (lane 2) or completely (lane 3) digested with TAP. The digests were analyzed as for panel F. (H) Proposed structures of cap B and its degradation products with TAP.

To investigate the negative net charges of the cap structures, aliquots of the 32P-labeled capped RNAs (Fig. 2A, lanes 1 to 3) were subjected to nuclease P1 digestion, and the liberated cap structures were analyzed by DEAE Sephacel (GE Healthcare, Amersham Biosciences) column chromatography. The 32P-labeled cap structures (0.7 × 104 to 1.1 × 104 cpm) in TU buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5 at 25°C], 7 M urea) were applied with unlabeled oligoRNAs, which were made by the digestion of yeast tRNA (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) with RNase A (USB), to a DEAE Sephacel column (inner diameter, 0.28 by 7.5 cm) preequilibrated with TU buffer. After the column was washed with 0.5 ml of the same buffer, the cap structures and oligoRNAs were eluted with a 10 ml-linear gradient of 0 to 220 mM NaCl in TU buffer, and fractions of 0.1 ml were collected. Marker oligoRNAs were detected by measuring the UV absorbance at a wavelength of 260 nm. Radioactivities of the fractions were measured in a liquid scintillation counter. As expected, GpppA, synthesized in the presence of [α-32P]GTP by the vaccinia virus CE, was eluted as a single peak with a −3 charge (Fig. 2C), since it contains three phosphate groups. GpppA and cap B, synthesized in the presence of [α-32P]GTP by the L protein, were eluted at −3 and −4 positions as a major peak and a discernible small peak, respectively, which could not be separated from the tail of the −3 peak (Fig. 2D). Cap B, synthesized in the presence of [γ-32P]GTP by the L protein, however, was eluted as a single peak with a −4 net charge (Fig. 2E), suggesting that the compound contains four phosphate groups.

To further characterize cap B, it was enzymatically digested and the digests were analyzed by PEI-cellulose TLC with 0.7 M ammonium sulfate (Fig. 2F and G). First, to confirm that phosphate groups in cap B are blocked, cap B labeled with [γ-32P]GTP (1.4 × 103 cpm) was retreated with 0.5 unit of CIAP at 37°C for 10 min (Fig. 2F). Under the conditions where [γ-32P]GTP was completely digested with CIAP (lane 2), cap B was resistant to CIAP (lane 4), suggesting that cap B has a blocked 5′-5′ tetraphosphate linkage. Next, to cleave the putative pyrophosphate bonds in cap B, it was treated with tobacco acid pyrophosphatase (TAP) at 37°C for 10 min (Fig. 2G). Limited digestion of cap B with 0.1 unit of TAP produced 32Pi- and 32P-labeled products, comigrating with ADP, ATP, and GTP on the TLC plate (Fig. 2G, lane 2), while its complete digestion with 1 unit of TAP resulted in the generation of 32Pi only (lane 3) (see Fig. 2H). The detection of putative [β-32P]ADP in the partial digest of cap B with TAP suggests that the γ-phosphate of [γ-32P]GTP is linked to the α-phosphate of AMP, derived from the 5′-ATP residue of the substrate RNA, in cap B via a pyrophosphate linkage. Taken together, these results (Fig. 1 and 2) indicate that cap B is GppppA.

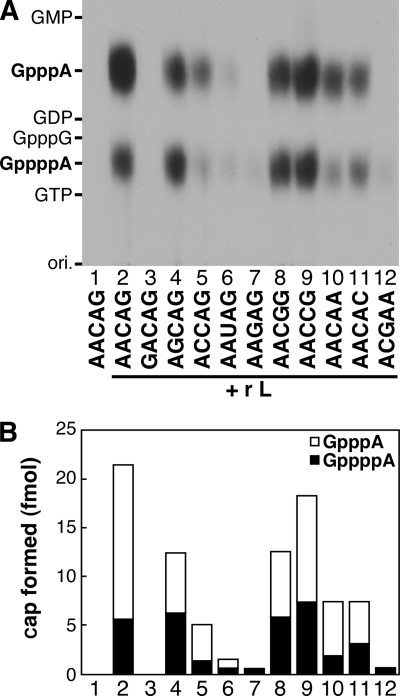

We have previously shown that 5′-triphosphorylated RNAs with the ARCNG (R = A/G) sequence are efficiently capped with [α-32P]GDP by the L protein (8). Furthermore, the first A and third pyrimidine residues have been found to be essential for the RNA substrate activity to generate the GpppA cap structure with GDP (8). In order to examine the RNA sequence specificity of the L protein in GppppN formation, 5′-triphosphorylated RNAs with various sequences were incubated with [α-32P]GTP and the recombinant L protein (Fig. 3A and B). As reported for GpppA formation with GDP (8), GppppA was efficiently formed on RNAs containing the ARCNG sequence (Fig. 3A, lanes 2, 4, 8, and 9). When the GACAG RNA was used, no possible cap structures, such as GpppG and GppppG, were formed (lane 3), suggesting that the first A is essential for GppppN formation. The AAGAG and ACGAA (the leader RNA start sequence) RNAs were obviously inert as substrates for GpppA formation with GTP (lanes 7 and 12) as well as GDP (8), but a very small amount of GppppA appeared to be formed on these RNAs (Fig. 3B, columns 7 and 12). Thus, it seems that the RNA sequence specificity of the L protein in GppppA formation is slightly lower than that in GpppA formation. Interestingly, percentages of GppppA in total cap structures varied among the RNA substrates from 26% (column 2, AACAG) to 100% (column 7, AAGAG; column 12, ACGAA). Among these sequences, the wild-type mRNA start sequence, AACAG, was the best for the formation of the GpppA cap structure on the RNA with GTP.

FIG. 3.

RNA sequence specificity of the VSV L protein in GppppA formation. (A) The recombinant L protein (r L) (50 ng) was incubated with 5′-triphosphorylated RNAs with indicated sequences and 0.5 μM [α-32P]GTP. The cap structures formed were analyzed as for Fig. 1A. Lane 1 indicates no enzyme. (B) Amounts of GpppA (open columns) and GppppA (filled columns) formed as described for panel A are shown.

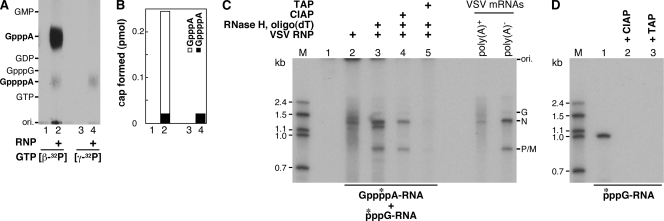

To analyze whether GppppA is cotranscriptionally formed on transcripts with the native L protein, in vitro transcription was performed with the purified VSV RNP (3 μg) in the presence of [β-32P]GTP or [γ-32P]GTP and three other nucleoside triphosphates (NTPs), as described previously (8). Purified transcripts were treated with CIAP, followed by nuclease P1, and then released cap structures were analyzed by PEI-cellulose TLC, followed by autoradiography (Fig. 4A). Because in our previous study (8) we could not clearly detect the GppppA cap structure formed on in vitro-synthesized VSV mRNAs due to its lower signal than that of GpppA, the TLC plate was exposed to an X-ray film for a longer time than in the previous study. When [β-32P]GTP was used, both Gpp*pA and Gpp*ppA formed on the transcripts could be detected (lane 2). The percentage of GppppA in total cap structures was 9% (Fig. 4B, column 2). Furthermore, by using [γ-32P]GTP, Gppp*pA was specifically detected (Fig. 4A, lane 4, and B, column 4). These results indicate that the VSV RNP-synthesized mRNAs contain the GppppA cap structure, although to a significantly lesser extent than GpppA.

FIG. 4.

Synthesis of GppppA-capped and polyadenylated transcripts with the VSV RNP. (A) The VSV RNP (3 μg of protein) was subjected to in vitro transcription with [β-32P]GTP or [γ-32P]GTP and three other NTPs. After the treatment of purified transcripts with CIAP, followed by nuclease P1, the liberated cap structures were analyzed as for Fig. 1A. Lanes 1 and 3 indicate no RNP. (B) Amounts of GpppA (open column) and GppppA (filled columns) formed as described for panel A are shown. (C) In vitro transcription was performed with (lanes 2 to 5) or without (lane 1) the VSV RNP in the presence of [γ-32P]GTP and three other NTPs. In vitro transcripts labeled with [γ-32P]GTP (lane 2) were incubated with RNase H and oligo(dT) to remove poly(A) tails (lanes 3 to 5). The poly(A)− transcripts were further treated with CIAP (lane 4) or TAP (lane 5). RNAs were analyzed by urea-5% PAGE, followed by autoradiography. Lane M shows [α-32P]GMP-labeled marker RNAs with indicated lengths. Poly(A)+ and poly(A)− VSV mRNAs indicate [α-32P]GMP-labeled in vitro transcripts before and after RNase H digestion in the presence of oligo(dT), respectively. The positions of the origin (ori.) and viral mRNAs are indicated on the right. (D) A [γ-32P]GTP-initiated RNA synthesized by SP6 RNA polymerase (lane 1) was treated with CIAP (lane 2) or TAP (lane 3). The samples were analyzed as for panel C. Lane M shows [α-32P]GMP-labeled marker RNAs with indicated lengths.

Next, purified transcripts synthesized in vitro in the presence of [γ-32P]GTP with the VSV RNP were separated by electrophoresis in a 5% polyacrylamide gel containing 7 M urea and were detected by autoradiography, where the sample was exposed to an X-ray film for a longer time. As shown in Fig. 4C (lane 2), 32P-labeled transcripts migrated as a broad smear in the gel. After the treatment of the transcripts with 0.3 unit of RNase H (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) in the presence of oligo(dT), three discrete bands with approximately 1.3, 1.2, and 0.8 kb were detected (lane 3), suggesting that these RNA species were polyadenylated. When these poly(A)− RNAs were further treated with 1 unit of CIAP at 37°C for 30 min to remove free phosphate groups (lane 4), some 32P radioactivities in the 1.3- and 0.8-kb RNAs were found to be resistant to CIAP. Interestingly, the 1.2-kb RNA disappeared completely after CIAP treatment. Furthermore, virtually all 32P radioactivities in the 1.3-, 1.2-, and 0.8-kb RNAs could be removed by treatment with 1 unit of TAP at 37°C for 30 min (lane 5). In a control experiment, when a [γ-32P]GTP-started RNA (994 nt), synthesized by SP6 RNA polymerase (Promega) from pGEM-3Z (Promega) digested with ScaI, was treated with CIAP or TAP under the same conditions as those for the VSV transcripts (Fig. 4D), 32P could be completely released from the RNA by either CIAP (lane 2) or TAP (lane 3). Thus, it seems that the CIAP-resistant transcripts (e.g., 1.3- and 0.8-kb RNAs, representative N and P/M mRNAs) start with the Gppp*pA cap structure and the CIAP-sensitive transcripts (e.g., 1.2-kb RNA) start with GTP (p*ppG-), indicating that the native VSV L protein in the RNP synthesized GppppA-capped and polyadenylated transcripts in vitro. In addition, some transcripts appeared to be initiated with GTP. The origins of these GTP-started transcripts remain unclear at present. Interestingly, internally initiated GTP-started small transcripts were reported to be present during transcription in vitro (7, 9).

We have thus demonstrated that in addition to the formation of GpppA (cap A), GppppA (cap B) is formed on the AACAG RNA substrate by the recombinant L protein, although in much smaller quantities. Similar GppppA-containing transcripts are also synthesized during the in vitro transcription reaction with the purified RNP. As shown in Fig. 1, GppppA was formed only when GTP and pppApApCpApG were used as substrates; neither GDP nor ppApApCpApG was able to support its formation. Furthermore, all the phosphate groups of GTP were incorporated into GppppA (Fig. 1) (8). From these results, we propose the following mechanism of GppppA formation:

|

|

At the first step, the putative PRNTase domain in the VSV L protein reacts with pppApApCpApG- to form a putative enzyme-RNA intermediate (L-pApApCpApG-), where the 5′-monophosphate end of RNA is probably linked to the L protein via a phosphoamide bond (8). For GpppA formation, the enzyme-bound 5′-monophosphorylated RNA is thought to be transferred to GDP generated from GTP (8). However, under the standard conditions for the in vitro capping assay, large portions of input GTP could not be hydrolyzed by the GTPase activity of the L protein (Fig. 1G and H) (8). Therefore, for GppppA formation, PRNTase seems to transfer the 5′-monophosphorylated RNA from the enzyme-RNA intermediate to GTP prior to removal of the γ-phosphate from GTP.

Conventional CEs (GTP:RNA GTases) of double-strand RNA viruses (5, 11), vaccinia virus (11), and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (12) have also been shown to synthesize similar guanosine(5′)triphospho(5′)nucleosides (GppppN) by guanylyl transfer to NTP via covalent enzyme-GMP intermediates. The wild-type vaccinia virus CE is known to produce only GpppN-capped RNAs from 5′-triphosphorylated RNAs and GTP, whereas its mutants, which exhibited less RTPase activiy, were found to make a GppppA-capped RNA as well (13). Furthermore, the open core of rotavirus, which had the GTase activity but not the RTPase activity, was shown to catalyze guanylyl transfer to 5′-triphosphorylated RNAs to generate GppppG-capped RNAs (4). Therefore, 5′-triphosphorylated RNAs serve as guanylyl acceptors for the above-mentioned CEs to form GppppN if there is little or no RTPase activity that usually converts almost all triphosphate ends of RNAs to the diphosphate ends before guanylylation. In contrast, for VSV PRNTase, GTP acts as an RNA acceptor to yield GppppA-capped RNAs. Although the biological significance of GppppA formation remains unclear, it appears to be formed in the same manner with VSV PRNTase by the transfer of the 5′-monophosphorylated RNA to residual GTP, which cannot be hydrolyzed by GTPase. This is to our knowledge the first example of GppppN formation with the RNA transfer mechanism. Our findings concerning the previously unknown substrate (RNA acceptor) specificity of the unconventional CE may provide a clue for future development of specific antiviral agents.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (AI26585 to A.K.B.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 21 May 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abraham, G., D. P. Rhodes, and A. K. Banerjee. 1975. Novel initiation of RNA synthesis in vitro by vesicular stomatitis virus. Nature 25537-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abraham, G., D. P. Rhodes, and A. K. Banerjee. 1975. The 5′ terminal structure of the methylated mRNA synthesized in vitro by vesicular stomatitis virus. Cell 551-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banerjee, A. K. 1980. 5′-Terminal cap structure in eucaryotic messenger ribonucleic acids. Microbiol. Rev. 44175-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, D., C. L. Luongo, M. L. Nibert, and J. T. Patton. 1999. Rotavirus open cores catalyze 5′-capping and methylation of exogenous RNA: evidence that VP3 is a methyltransferase. Virology 265120-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cleveland, D. R., H. Zarbl, and S. Millward. 1986. Reovirus guanylyltransferase is L2 gene product lambda 2. J. Virol. 60307-311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furuichi, Y., and A. J. Shatkin. 2000. Viral and cellular mRNA capping: past and prospects. Adv. Virus Res. 55135-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hefti, E., and D. H. Bishop. 1976. The 5′ sequences of VSV in vitro transcription product RNA (+/−SAM). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 68393-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogino, T., and A. K. Banerjee. 2007. Unconventional mechanism of mRNA capping by the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of vesicular stomatitis virus. Mol. Cell 2585-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schubert, M., G. G. Harmison, J. Sprague, C. S. Condra, and R. A. Lazzarini. 1982. In vitro transcription of vesicular stomatitis virus: initiation with GTP at a specific site within the N cistron. J. Virol. 43166-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shuman, S. 2001. Structure, mechanism, and evolution of the mRNA capping apparatus. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 661-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith, R. E., and Y. Furuichi. 1982. A unique class of compound, guanosine-nucleoside tetraphosphate G(5′)pppp(5′)N, synthesized during the in vitro transcription of cytoplasmic polyhedrosis virus of Bombyx mori. Structural determination and mechanism of formation. J. Biol. Chem. 257485-494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang, D., and A. J. Shatkin. 1984. Synthesis of Gp4N and Gp3N compounds by guanylyltransferase purified from yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 122303-2315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu, L., and S. Shuman. 1996. Mutational analysis of the RNA triphosphatase component of vaccinia virus mRNA capping enzyme. J. Virol. 706162-6168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]