Abstract

Common hereditary neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia are most likely both genetically multifactorial and heterogeneous. Because of these characteristics traditional methods for genetic analysis fail when applied to such diseases. To address the problem we propose a novel probabilistic framework that combines the standard genetic linkage formalism with whole-genome molecular-interaction data to predict pathways or networks of interacting genes that contribute to common heritable disorders. We apply the model to three large genotype–phenotype data sets, identify a small number of significant candidate genes for autism (24), bipolar disorder (21), and schizophrenia (25), and predict a number of gene targets likely to be shared among the disorders.

Autism, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia are common maladies characterized by moderate to high heritability, such that patterns of DNA sequence variation transmitted from parents to offspring should correlate with susceptibility to (or protection against) disease. Numerous epidemiological and genetic analyses have suggested that none of these disorders can be explained by a single environmental or genetic cause and that all are probably grounded in multiple genetic abnormalities (Veenstra-VanderWeele et al. 2004; Harrison and Weinberger 2005; Craddock and Forty 2006). In contrast to rare hereditary disorders, where the genetic mapping of single-gene disease-causing mutations has been enormously successful (McKusick 2007), the detection of multilocus genetic variation that renders the individual susceptible to development of a common heritable disorder has proved to be much more challenging.

A major obstacle to the detection of heritable patterns of disease susceptibility is the curse of dimensionality (Bellman 1961)—the exponentially expanding search space required to explore all combinations of m genes or m genetic loci. Assuming that we have 25,000 genes in our genome, the number of possible combinations of m genes increases exponentially, from roughly 108 to 1012, to 1016, to 1037 for m = 2, 3, 4, and 10, respectively. Moreover, even the largest human genetics studies are limited to the observation of several thousand meiotic events (the number of instances where we can evaluate transmission of a given genetic variant from parents to offspring). Consequently, an exhaustive combinatorial search of even very small sets of multiple genetic loci would lead to an enormous burden of false-positive signals for every real linkage signal because the number of statistical tests of significance performed on the same data set becomes too large to allow for any useful level of statistical power.

The second obstacle to detecting multigenic inheritance is that, even when a set of genes is identified as related to a disease, how variations within the genes jointly affect the susceptibility to disease remains unknown. Genetic variation across multiple interacting genes may affect phenotype in a linear (additive) manner or in a nonlinear (epistatic) way; the groups of interacting genes are likely to affect the disease phenotypes via an as-yet-unknown mixture of both interaction types. Furthermore, disease susceptibility may increase incrementally with increasing genetic variation or dichotomously via a threshold effect. Finally, there is well-grounded suspicion (Harrison and Weinberger 2005) that the genetic causes of a given disorder can be completely or partially different for different affected families. Although it is tempting to test the whole spectrum of inheritance models, currently it is an impractical task: The total number of possible models of inheritance involving m genetically interacting genes grows exponentially with m, and that increase further exacerbates the exponential growth of the number of distinct gene sets of size m.

To address these practical and theoretical complications, we propose a novel probabilistic method. This method restricts the search space for candidate gene sets by using knowledge about molecular pathways and explicitly incorporates information about within-data set heterogeneity. Our approach extends the well-established multipoint genetic linkage model (Kruglyak et al. 1996). Multipoint linkage analysis is a mathematical model that detects correlations between disease phenotypes within human families and states of multiple polymorphic genetic markers that are experimentally probed in every family member. Our extension of the standard multipoint linkage analysis includes two additional major assumptions. First, unlike in previous work (Krauthammer et al. 2004; Aerts et al. 2006; Franke et al. 2006; Tu et al. 2006; De Bie et al. 2007; Lage et al. 2007), we assume that genetic variation within multiple genes (rather than a single gene that is common to all affected individuals) can influence the disease phenotype and that potential disease-predisposing genes are grouped into a compact gene cluster within a molecular network (“gene cluster” is defined precisely below). We explicitly model biological information about functional relationships between genes as a large molecular network of physical interactions. Using the constraints imposed by the molecular network, we dramatically restrict the search for sets of genes that can predispose a person to a complex disorder and we also formulate gene predictions that are biologically rooted. Second, we explicitly assume that heterogeneity of genetic variations underlie the same phenotype in different affected families. Following Occam’s razor (“All things being equal, choose the simplest theory”), we start by implementing the simplest generative model of a complex disease (single-gene genetic heterogeneity). We apply the extended model to detect significant correlations among three disease phenotypes (autism, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia) and genetic variation in groups of genes that are united by known physical and biochemical interactions (such as “BCL2 binds BAD” and “CDK5/DCTN5 phosphorylates TP53,” see the following section and the Model Definition section for modeling details).

Instead of computationally testing all possible sets of m genes as candidates for harboring disease-predisposing genetic variation, we restrict our analysis to a much smaller collection of m-gene sets that encode physically interacting molecules. Furthermore, we implement a procedure to enhance the linkage signal by computing gene-specific P-values that characterize linkage significance (see Gene-Specific Significance Tests section). The gene-specific significance test measures how likely it is that a particular gene is linked to a phenotype given that the phenotype is unlinked to any position in the genome. We need this test because genes within a large molecular network differ markedly in their topological neighborhoods; the highly connected genes tend to be spuriously implicated in linkage to a phenotype more frequently than the poorly connected genes. We also identify highly nonrandom overlaps among predicted candidate genes for all combinations of the three disorders (see Overlap Significance in the Supplemental material).

In this study, we use a molecular-interaction network generated by the large-scale text-mining project GeneWays (Rzhetsky et al. 2004). Our analysis uses only direct interactions between genes or their products (a total of 47 distinct types, such as binding, phosphorylation, and methylation) as opposed to regulatory interactions between pairs of genes that are indirect (activation or inhibition) and can be mediated by a large number of other molecules. Our molecular network includes nearly 4000 genes (see Molecular Network in the Supplemental material for details).

Gene clusters and gene mixture generative model of a complex disease

When thinking about a complex hereditary disorder, we imagine a set of genes that can contribute to the risk of contracting a given disease phenotype when the sequence of at least one of them is critically modified. Under this assumption we define a gene cluster, C, as a set of genes with members that are grouped by their ability to harbor genetic polymorphisms that predispose the bearer to a specific disease. For every gene within a gene cluster C we define a cluster probability, denoted by pi (for the ith gene, i = 1, . . . , c, where c is the size of the cluster), so that the sum of pi over i = 1, . . . , c is equal to 1. We can think of the cluster probability pi as the share of guilt attributable to variations at the locus of the ith gene for the disease phenotype in a large group of randomly selected disease-affected families. Consider a hypothetical example that illustrates these concepts. Imagine that we have two genes, A and B, that encode directly interacting proteins; according to our definition, we have a gene cluster of size c = 2. Furthermore, imagine that both genes can harbor genetic variation predisposing the bearer to disorder Z, so that, among people affected with disease Z, 60% have harmful polymorphisms in gene A while the remaining 40% of affected individuals bear an aberration in gene B. In our model genes A and B would be associated with cluster probabilities 0.6 and 0.4, respectively.

Here we explicitly assume that gene clusters are sets of genes that are joined through direct molecular interactions into a “connected subgraph”. This assumption appears to be well-justified based on our study of the physical-interaction clustering of genes harboring variations responsible for Mendelian and complex phenotypes (Feldman et al. 2008). We have discovered that genes known to participate in the same polygenic disorder tend to be close to each other in a molecular network; this result holds for two independently derived and rather different molecular-network models, including the molecular network used in this study.

A gene that has a zero cluster probability may not be directly involved in the disease etiology even though it is a member of the gene cluster that has the highest likelihood value. These zero-contribution genes can serve as connectors for genes that are strongly linked to the disease. On the other hand, genes with higher cluster probabilities are potentially more attractive putative targets for development of drugs and diagnostic tests because they account for a larger number of individuals affected by the disease and are more likely to bear disease-predisposing polymorphisms at the corresponding loci. A sufficiently large set of genes with appropriate cluster probabilities can be used to represent an arbitrary complex topological arrangement of a set of network-linked genes, albeit at a computational cost that grows rapidly with an increase in gene cluster size. Using the substantial computational resources at our disposal, in this study we analyze clusters up to 10 genes for all three disorders.

The precise formulation of our mathematical model requires two additional assumptions. First, we assume that only those genes that are within a gene cluster, C, harbor a disease-predisposing variation. Second, we assume that, for every family under analysis, exactly one gene from cluster C is a disease-predisposing gene. That is, the phenotype status of every individual is determined by the state (the allele) of the family-specific gene in the individual’s genome. Thus, our disease model is a mixture of probabilistic models, each of which is determined by one disease-predisposing gene in C, with the mixing coefficients being the cluster probabilities. The set of families affected by the same disease under this model is a mixture of families that are predisposed to the disease via mutations at different genes that belong to C.

Under these assumptions, we combine the molecular-interaction network in the GeneWays 6.0 database (Rzhetsky et al. 2004) with whole-genome microsatellite genetic-linkage information to test multigenic patterns of inheritance in three major neurodevelopmental disorders. Specifically, we analyze genotypic and phenotypic data from three of the largest genetic linkage data collections. These data represent 336 multiplex autism families, 414 multiplex bipolar families, and 87 multiplex schizophrenia families (see Supplemental Table S5 for detailed information). A family is dubbed “multiplex” with respect to a specific disease if it includes more than one affected person. Evidence for single-gene contributions (in the context of interactive gene networks) to disease susceptibility is represented as a set of simulation-based empirical P-values (see Tables 1, 2).

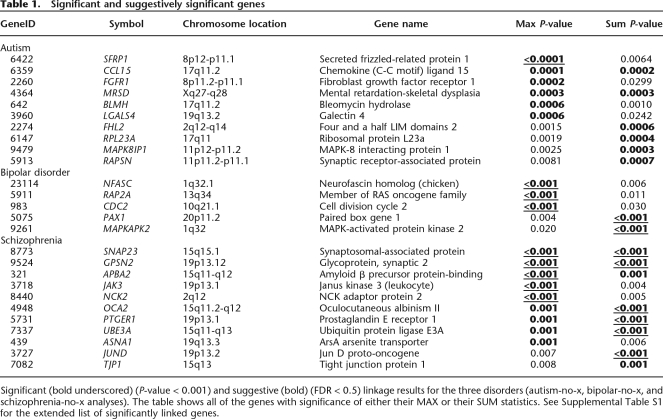

Table 1.

Significant and suggestively significant genes

Significant (bold underscored) (P-value < 0.001) and suggestive (bold) (FDR < 0.5) linkage results for the three disorders (autism-no-x, bipolar-no-x, and schizophrenia-no-x analyses). The table shows all of the genes with significance of either their MAX or their SUM statistics. See Supplemental Table S1 for the extended list of significantly linked genes.

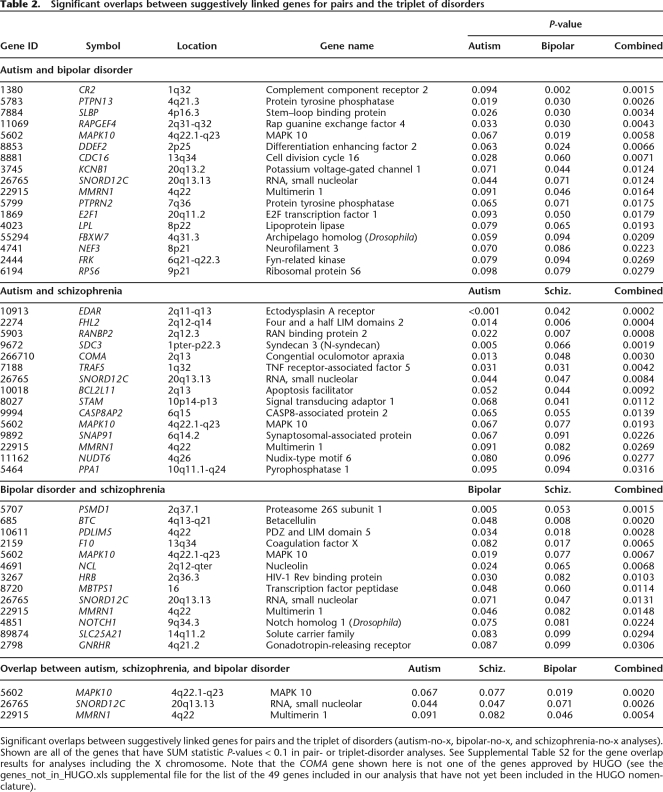

Table 2.

Significant overlaps between suggestively linked genes for pairs and the triplet of disorders

Significant overlaps between suggestively linked genes for pairs and the triplet of disorders (autism-no-x, bipolar-no-x, and schizophrenia-no-x analyses). Shown are all of the genes that have SUM statistic P-values < 0.1 in pair- or triplet-disorder analyses. See Supplemental Table S2 for the gene overlap results for analyses including the X chromosome. Note that the COMA gene shown here is not one of the genes approved by HUGO (see the genes_not_in_HUGO.xls supplemental file for the list of the 49 genes included in our analysis that have not yet been included in the HUGO nomenclature).

We analyzed multiple disorders for several reasons. Most importantly, despite their differences these three disorders share multiple symptoms. Autism, which has been recognized as an independent disorder only in recent years, was originally called “childhood schizophrenia” because of multiple symptom overlap (Akande et al. 2004; Harrison and Weinberger 2005), particularly the presence of negative symptoms of schizophrenia (such as disruption of processing of emotions and social withdrawal). Similarly, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia form a continuum of symptoms (phenotypes), with a phenotypic variant called schizoaffective disorder lying in between (a union of symptoms of both disorders). Several less common symptoms of autism and bipolar disorder (for example, hallucinations, that are only anecdotally reported in autistic patients; see Mukhopadhyay 2003) also overlap (Stahlberg et al. 2004). A significant literature describes the symptomatology shared among these three neuropsychiatric disorders, particularly for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. The organic causes of the three disorders remain mysterious, so in each case diagnosis depends largely on behavioral symptoms. We suggest that shared genetic variations underlie the similar behavioral symptoms in these distinctly defined disorders.

Prior work

Several years ago we (Krauthammer et al. 2004) proposed a method that, given a molecular network and a set of gene-specific genetic linkage signals, identifies network neighborhoods that are significantly enriched with genes with higher-than-average linkage scores. We assumed that a human molecular-interaction network harbors numerous connected subgraphs and that each subgraph is causally linked to a specific disease phenotype. We originally applied our algorithm to analyze Alzheimer’s disease data. A subsequent study (Franke et al. 2006) evaluated this approach within the context of a large molecular network computed by integrating multiple whole-genome data sets; their analysis covered several Mendelian and polygenic disorders. Another group (Tu et al. 2006) applied pathway information to guide their inference of genetic trans-regulators, starting with a genetic analysis of gene expression in yeast. Many groups of researchers have used molecular networks to prioritize their experimentally identified candidate genes by estimating and ranking functional similarity scores of the candidate genes to other molecules involved within the same disorder or pathway (Aerts et al. 2006; De Bie et al. 2007; Lage et al. 2007).

All of these methods have two things in common: a classical (molecular pathway-oblivious) genetic analysis and a procedure for pathway-guided ranking of putative correlations between phenotypes and genomic loci. Our computer simulations (see Simulations in the Supplemental material) indicate that, if the disease phenotype is inherited according to the genetic heterogeneity model (network gene cluster), as implemented in our current approach, the classical single-locus genetic analysis methods tend to perform poorly in identifying disease susceptibility genes.

Results and Discussion

The best candidate genes identified by our analysis (see Tables 1, 2) reside in genomic regions that are also supported, in a “subset” of affected families, by the conventional multipoint linkage analysis applied to the same data. In this sense our results are directly compatible with those from earlier studies. Unlike previous studies, however, our method analyzes “groups” of functionally related genes rather than individual genes and, as a result, the linkage signal is magnified through summation over multiple genes within the same gene cluster, while each individual gene may exhibit only a weak evidence of linkage. From the gene cluster analysis, we obtain a small number of candidate genes for each disorder with significant empirical P-values that are appropriately adjusted for multiple testing (see Gene-Specific Significance Tests section; Benjamini and Hochberg 1995; Benjamini and Yekutieli 2001). In contrast, the results of the traditional linkage methods are large genomic regions that may contain hundreds of genes, only a few of which are directly linked to the disorder. Furthermore, our gene-specific P-values differ from the traditional empirical genetic locus-specific P-values that are computed using strictly local linkage information. Our P-values are based on a simulation of whole-genome data under a no-linkage null model. The null model represents the worst-case scenario in which a phenotype is completely uncorrelated with the states of the genetic markers under study; small P-values indicate that the null model fits the data poorly and that, therefore, a genetic linkage signal is present. Simulations under the null model are followed by a search for the maximum-likelihood gene cluster within a whole-genome molecular-interaction network (see Gene-Specific Significance Tests section; Tables 1, 2).

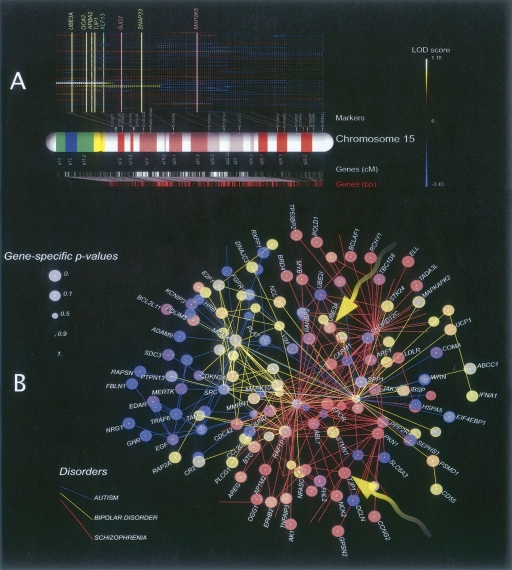

We present the results for chromosome 15 from the autosome-only analysis of the schizophrenia families (Fig. 1A) to provide an intuitive explanation of our methodology. The figure displays the whole-chromosome log-odds (LOD) scores for every family in the data set computed using conventional multipoint-linkage methods. A log-odds score for a specific genomic position is a decimal-base logarithm of the ratio of two probabilities where one of the phenotypes is correlated with the given genomic position and the other is uncorrelated with “any” genomic position (see Equation 2). Large positive values of this score indicate strong evidence of correlation, whereas large negative values indicate strong evidence “against” correlation between a phenotype and this particular genomic position. Superimposed on the figure are the eight genes (UBE3A, OCA2, APBA2, TJP1, KLF13, GJD2, SNAP23, and MP2K5) that have significant gene-specific P-values according to our method. The most significant P-values are <0.001 for UBE3A, OCA2, and SNAP23; 0.001 for ABPA2; 0.001 for TJP1; and 0.004 for KLF13. Note that these genes are located on the genetic map close to the maxima of the LOD score functions for several families in the data set. In the Supplemental materials we show similar figures for each of the 22 autosomes and the X chromosome (where applicable) for all of the analyses that we performed.

Figure 1.

An example of genetic-linkage data used as the input to our analysis and the resulting network of top-scoring genes for the three disorders. (A) Standard multipoint-linkage analysis of human chromosome 15 for 94 schizophrenia families (schizophrenia-no-x analysis). Each line above the chromosome map represents the linkage signal for one family. Also shown are the positions of genetic markers on the chromosome map and the set of top-scoring candidate genes. In this case, four genes (CYFIP1, UBE3A, OCA2, and TJP1) have significant linkage statistics. (B) The molecular network obtained by superimposition of the 70 best 10-gene clusters for each of the three disorders analyzed in this study (autism-no-x, bipolar-no-x, and schizophrenia-no-x analyses). Arrows indicate two genes (UBE3A and TJP1) discussed in the main text. Note that the COMA and TAM genes are not yet approved by HUGO (see the genes_not_in_HUGO.xls supplemental file).

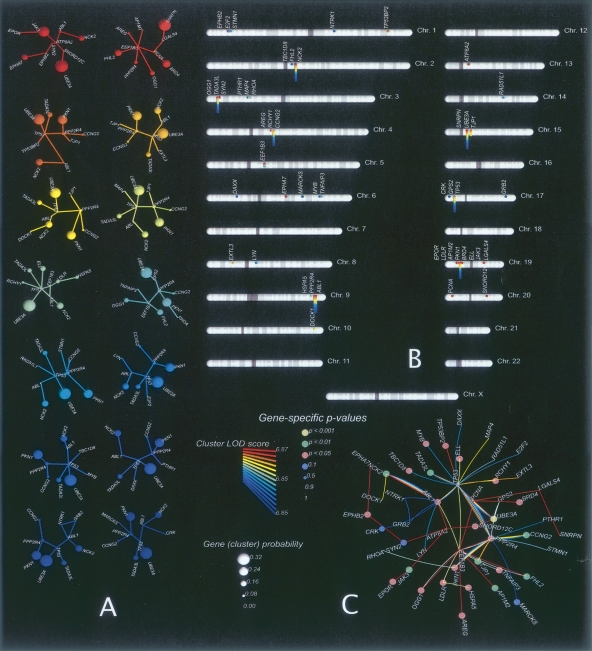

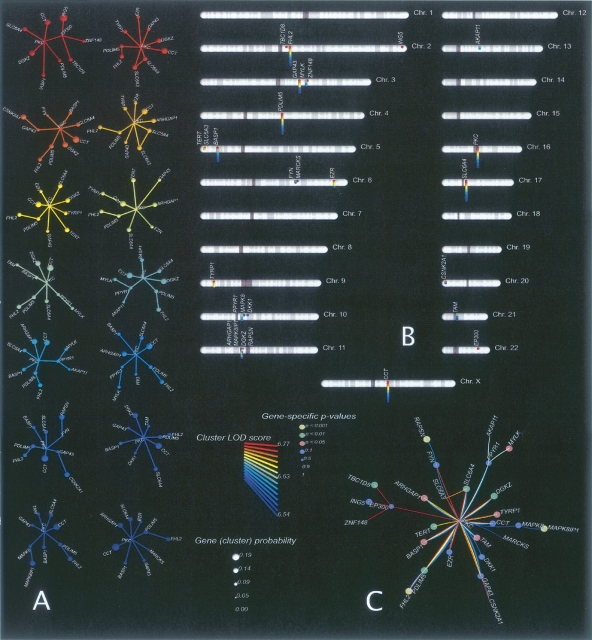

The conventional single-gene linkage signal for TJP1 or UBE3A on its own yields a weak empirical P-value because of the genetic heterogeneity of the families: In addition to families with positive LOD scores there are families that show strong negative signals for both genes. It is only when we consider gene clusters that the linkage signal becomes strong and obvious. Figure 2 shows the typical output for this type of analysis for the schizophrenia data: The 14 top-ranking gene clusters are displayed with their corresponding LOD score statistics (color-coded, see legend) on the left of the figure (Fig. 2A). The estimated gene cluster probability (gene “guilt share” for the phenotype) is indicated by the size of the corresponding gene node, and the chromosomal location of each cluster gene and its cluster composition (color-coded) is displayed to the right (Fig. 2B,C). In contrast to the maximum-likelihood clusters, random clusters of 10 genes yield overwhelmingly negative cluster LOD scores (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Analysis of the 14 top-scoring 10-gene clusters for the schizophrenia data (schizophrenia-no-x). (A) Each cluster is shown separately, where the vertex size represents the cluster probability estimated for the corresponding gene. We used the color of the cluster to encode cluster LOD scores. (B) Position of all genes represented in the 14 clusters on human autosomes. (C) Molecular network combining the 14 clusters in one graph. In this case, the color and size of nodes indicate gene-specific P-values associated with each gene.

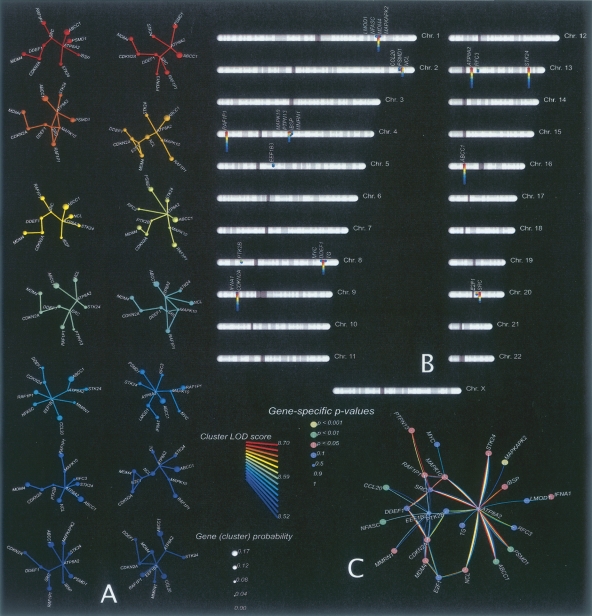

Figures 3 and 4 show results for the 14 top-scoring gene clusters for the corresponding autism and bipolar disorder data sets. The gene clusters shown in Figures 2, 3 and 4 vividly illustrate the uneven contribution of different genes within the same cluster to the overall cluster LOD score. Each group of clusters has heavy contributors: For example, UBE3A, CCT, and ABCC1 (for schizophrenia, autism, and bipolar disorder, respectively) have cluster probabilities of 0.32, 0.15, and 0.16. There are also genes with nearly zero contribution to the cluster LOD score (such as the ubiquitous brain-expressed ATP8A2, a major network hub; Barabasi and Albert 1999), which are nevertheless indispensable as connectors for multiple heavy-duty contributor genes.

Figure 3.

Analysis of the 14 top-scoring 10-gene clusters for the autism data (autism-x-rec); see Figure 2 for explanation of panels A–C. Note that the PKC and TAM genes are not yet approved by HUGO (see the genes_not_in_HUGO.xls supplemental file).

Figure 4.

Analysis of the 14 top-scoring 10-gene clusters for the bipolar disorder data (bipolar-no-x); see Figure 2 for explanation of panels A–C.

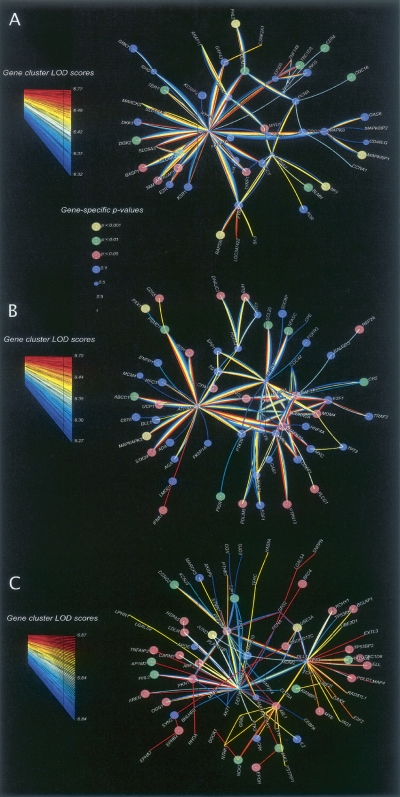

Figure 5 shows a conglomerate of a larger number of top-ranking LOD score clusters for all three disorders, with gene-specific P-values for each involved gene (denoted by the size and color of the corresponding gene nodes). Figure 5A–C displays the top-ranking 100, 100, and 50 10-gene clusters, for autism, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia, respectively. Because the schizophrenia data set is relatively small, the top LOD clusters are less compact within the molecular network compared to those for autism and bipolar disorder. The 50-cluster molecular network for schizophrenia is almost as large as the 100-cluster networks for autism and bipolar disorder. Nevertheless, the graphs indicate that our input data are informative: We can imagine completely uninformative data resulting in most of our 50 top LOD score 10-gene clusters being disconnected and incorporating close to 500 distinct genes, rather than covering a well-defined network neighborhood.

Figure 5.

Molecular networks combining the 100 best 10-gene clusters for autism (A) and bipolar (B) disorder and the 50 best 10-gene clusters for schizophrenia (C). The color and size of nodes in all three networks indicate gene-specific P-values (autism-no-x, bipolar-no-x, and schizophrenia-no-x analyses). Note that the LOC347422, PKC, TAM genes are not yet approved by HUGO (see the genes_not_in_ HUGO.xls supplemental file).

Table 1 displays the top-ranking candidate genes for each of the three disease-gene analyses, rank-ordered based on their gene-specific P-values. Following Lander and Kruglyak’s guidelines (Lander and Kruglyak 1995), we classified all candidate genes for each of the three disorders represented in our molecular network into significant (genes with apparent P-values < 0.001) and suggestively significant (genes that appear statistically significant at the false-discovery rate of 0.5; Benjamini and Hochberg 1995; Benjamini and Yekutieli 2001) (see FDR Procedure section). Table 2 displays the top-ranking candidate genes detected in combinations of two- or three-disease analyses.

Figure 1 provides a pictorial summary of the data in Tables 1 and 2, from which we make the following observations. First, the top-ranking clusters from each of the three data sets lie within tightly clustered neighborhoods of the molecular-interaction network. The within-network proximity of the high-ranking gene candidates is higher for the larger data sets (autism and bipolar disorder). Second, the molecular-network neighborhoods for the three disorders are different, even though they partially overlap. The figure suggests somewhat greater overlap among susceptibility genes related to schizophrenia and bipolar disorder relative to autism. Finally, there are multiple genes with strong P-values (<0.005) for more than one of the three disorders, as reflected by the color and size of the spheres (the color of each transparent sphere is associated with one of the three disorders; when the same node has strong P-values for more than one disorder, two or more spheres are nested and the resulting color is a mixture).

A closer look at the candidate genes reveals that many are regulators of cell cycle and cell death (e.g., EDAR, BCL2L11, NEK6, SFRP1, and MAPK7). Another smaller subset of genes is responsible for forming intercellular contacts (tight junction protein 1 [TJP1], LGALS4, MMRN1, IBSP, and NPHP1). A few genes are brain-specific growth and signal-transduction receptors and small-molecule transporters (RAPSN, APBA2, UBE3A, ALK, and KCNB1), and a few others are related to the immune response (e.g., CCL15, CSF2, CD55, IL10).

In their recent study of positive selection patterns in the human genome, Bustamante et al. (2005) discovered that many genes involved in cell-cycle and cell-death regulation appear to have undergone recent positive selection in the lineage leading to hominid primates. Thus, it is plausible that phenotypic effects that we classify as neurological disorders are artifacts of a mosaic of small genetic changes that occurred during evolutionary optimization of multiple physiological systems involved in the unusually prolonged individual development of a human brain. (A pathway-level natural selection was examined recently using bacterial molecular networks; Wolf and Arkin 2003.) Development of the human brain involves a precisely orchestrated sequence of decisions that determine cellular fate, and both genetics and environmental stimuli contribute to the live-or-die verdict for individual neurons. In retrospect, it is not surprising that our top disease-predisposing candidate loci are enriched with these cell-death (P-value of 0.03) and cell-cycle (P-value of 0.001) related genes as computed by a test of randomized gene sampling using gene ontology (Ashburner et al. 2000; Harris et al. 2004) categories (P-values 0.03 and 0.001, respectively; see, for example, Rivals et al. 2007, for a description of the tests). However, this significance of enrichment is likely to be a mere reflection of the overall abundance of cell-cycle and cell-death related genes in our text-mined network (P < 10−10).

Although it is not feasible to describe our entire disease-specific candidate gene set, a few genes merit comment. Researchers have previously considered several of our top-ranking candidate genes in genetic analyses of complex neurodevelopmental disorders. For example, Lovlie and colleagues already implicated our bipolar candidate, PLCG1, in bipolar disorder (Lovlie et al. 2001). The ion-transporter MLC1, one of our top-ranked genes for autism, has been associated with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (Verma et al. 2005). The UBE3A gene is implicated in autism when inherited as a maternal interstitial duplication, which suggests both genetic and epigenetic causation; our finding of strong gene cluster contribution for UBE3A in schizophrenia is intriguing in view of multiple reports that genomic imprinting may play a role in disease etiology (Veenstra-VanderWeele et al. 1999; Nurmi et al. 2001; Jiang et al. 2004). Gene expression and association analyses of PDLIM5 (which for us lies in the overlap between bipolar disorder and schizophrenia) suggest its involvement in the etiology of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia (Kato et al. 2005), and RAPGEF4 (in the bipolar disorder and autism overlap genes) has been related to the autistic phenotype (Bacchelli et al. 2003). Intriguingly, many of our candidate genes have been analyzed in relation to Alzheimer’s disease: BLMH (Nivet-Antoine et al. 2003); MAPK8IP1 (Helbecque et al. 2003); MAPKAPK2 (Culbert et al. 2006); LPL (Blain et al. 2006); NEFM (Wang et al. 2002); FRK (Watanabe et al. 2004); and KCNIP3 (Jin et al. 2005). We also find interesting candidates in the genes that barely missed meeting our statistical significance criteria. For example, NRG1 (with a gene-specific P-value of 0.001 in one of our autism analyses) has been long considered by experts to be the top schizophrenia candidate gene (Harrison and Weinberger 2005), and NF1 (P-value of 0.0009 in our autism analysis) is known to be genetically linked to neurofibromatosis (Ars et al. 2000), a Mendelian genetic disorder with pronounced cognitive symptoms.

All 14 top-ranking autism clusters include the serotonin transporter gene SLC6A4 (P-value of 0.0016 in our autism analysis). The SLC6A4 gene has long been implicated in the genetic etiology of autism based on both genetic and physiological evidence (Cook and Leventhal 1996; Cook et al. 1997; Klauck et al. 1997; Yirmiya et al. 2001; Hariri et al. 2002; Kim et al. 2002). Moreover, conventional genetic linkage studies of this data set identified SLC6A4 as the single top-ranking candidate gene (Yonan et al. 2003).

Note that our analysis does not identify as significant any of the 16 genes that were previously suggested to be most likely related to schizophrenia susceptibility (Harrison and Weinberger 2005). To verify our results, we superimpose the positions of these 16 genes with chromosome-specific linkage signals for the 94 families described in our schizophrenia data set (see Supplemental materials). Consistent with the hypothesis of genetic heterogeneity, we find that our 94 families provide no or very weak linkage support for the majority of the 16 genes (e.g., RGS4 and DISC1 [chr 1]; GAD1 [chr 2]; and GRM3 [chr 7]). A subset of the 94 families provides good linkage support for MUTED, DTNBP1, and OFCC1 (chr 6), but, unfortunately, these genes have few known direct physical interactions and are either disconnected or poorly connected within our molecular-interaction network. If the hypothesis of genetic heterogeneity of the schizophrenia phenotype is correct, we should be able to find additional support for some of these 16 genes when analyzing a greater number of affected families and a larger molecular network.

Unlike our earlier predominantly heuristic approach (Krauthammer et al. 2004), our current work unifies molecular networks and the parametric genetic-linkage formalism within a coherent mathematical model whose parameters (cluster probabilities) are estimated from data and are readily interpreted biologically. We analyzed data under multiple models of genetic penetrance and found that our results are remarkably robust with regard to penetrance model variation (see Analysis Settings and Important Observations in the Supplemental material). Because we based our mathematical model on conventional linkage approaches, it is applicable to the study of any of the common heritable disorders. The appropriate genotype–phenotype data are already available for many such disorders. As with our earlier algorithm, our current analysis depends largely on the quality and size of the molecular-interaction network used as input. Here, we use a molecular network that contains ∼4000 human genes and omit from our analysis the Y chromosome and the mitochondrial genome. Based on our current work, we believe that it is feasible to collect molecular-interaction information on 12,000 or more human genes in the near future using the literature-mining approach.

Similar to all other computationally tractable mathematical models, ours is associated with certain simplifying assumptions and limitations. Specifically, our genetic model (heterogeneity) is the simplest representative of a large family of multigenic inheritance models. Furthermore, in our current implementation of the model we perform our analysis with a predefined gene cluster size rather than searching through all possible gene cluster sizes. Our current model is limited to genetic linkage analysis, although it can be naturally transformed for application to genetic association and gene expression data. All of these limitations can be addressed in the future with more complicated modeling and significantly better computational resources.

Our framework is well suited to modeling complex inheritance so that we can efficiently evaluate a range of linear and nonlinear multilocus inheritance models. A unique feature of our model is that it employs genetic linkage data to identify “genes” rather than genetic linkage “intervals”. Thus, in addition to circumventing the search-space problem, the method also avoids the daunting positional cloning typically required in the study of common heritable disorders. We are optimistic that increasingly more sophisticated genetic models can and will be developed despite the large model search-space limitation. We also expect that, in the near future, we and other groups will perform experimental validation studies that will verify our approach.

Methods

Model definition

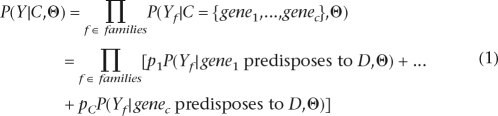

We use the symbol D to represent a specific phenotype (disease) whose genetic component we wish to identify. For gene cluster C, the two major model assumptions discussed in the main text lead to the following likelihood equation:

|

where C is the D-predisposing gene cluster comprising gene1, gene2, . . . , genec, with the corresponding cluster probabilities p1, p2, . . . , pc. Variable Y represents a union of the genotypic and phenotypic data; Yf is the portion of these data associated with the fth family (pedigree). Vector Θ represents all of the linkage-related parameters, including genetic penetrance, background frequencies of marker alleles, and genetic distances between the markers. We assume here that every gene in C has only one healthy and one disease-predisposing allele and that the expected frequencies of these alleles are the same for all genes in the cluster. We also assume that the genetic-penetrance parameters are the same for every gene in C.

Under this model, given the state of the chosen gene, the disease-phenotype state of the individual is independent of the rest of the individual’s genome and of the genotypes and phenotypes of her/his family members. This assumption of independence leads to a “gene mixture generative model” of the data: The ith disease-predisposing gene is assigned to a family by a random draw from C with probability pi. Once a gene is assigned to a family, the disease-related phenotype variation in this family is probabilistically dependent on the state of the ith gene and is independent of the states of all other genes in C and in the rest of the genome. Supplemental Figure S3 shows a graphical representation of the model, and Supplemental Figures S4 and S5 clarify the pedigree structure and its relation to the graphical model.

Gene log-odds score

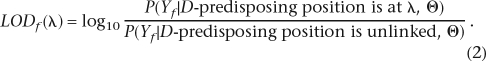

Using standard tools of statistical genetics, we can compute a log-odds (LOD) score for every gene and for every family (f) represented in our data. Assuming that there is exactly one D-predisposing genetic locus per family, we can compute the LOD score for any individual position (λ) in the genome:

|

Assuming that we know the beginning and the end of the ith gene, we can compute a gene-specific LOD LODf (genei); this represents the LOD score in the middle of the gene or at a uniformly sampled position within the gene.

Gene cluster log-odds score

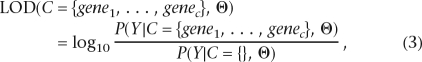

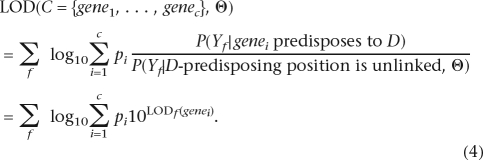

We define a “gene cluster LOD score” as follows:

|

where P(Y|C ={}, Θ) is the familiar probability P(Yf|D-predisposing position is unlinked, Θ), renamed to emphasize its relation to gene clusters.

We can calculate the cluster LOD score using the following equation:

|

In the case of a single-gene cluster (c = 1 and p1 = 1), Equation 4 translates to the sum of the gene-wise LOD scores for all individual families.

Gene-specific significance tests

We define the optimum gene cluster of size c as the cluster of c genes that achieves the maximum cluster LOD score as defined by Equation 4, where the gene cluster probabilities (pis) are estimated using the maximum-likelihood method for each cluster. We identify the optimum c-gene cluster by using a version of the simulated annealing procedure (Kirkpatrick et al. 1983) (see Simulated Annealing in the Supplemental material for details of the implementation). Because a simulated annealing-based search for the optimum in the discrete space of a molecular-network graph clearly has an element of stochastic instability, we use a bootstrap-aggregation (bagging) technique to “push a good but unstable procedure a significant step towards optimality” (Breiman 1996). To implement the bagging technique, for each data set we perform bootstrapping (Efron 1982) over all families represented in the data set to generate B bootstrap replicates (we use B = 100). We obtain each bootstrap replicate data set by drawing pedigrees from the original data set, at random but with replacement. As a result, each pedigree from the original simulated data set may appear several times or not at all in any bootstrap replicate. For each replicate, we identify the optimum (maximum-likelihood) cluster of size c with the corresponding maximum-likelihood estimates of cluster probabilities, pis. All genes not included in the optimum cluster are assigned cluster probability values of zero. The test statistic for each gene over B bootstrap replicates is merely a sum of estimates of cluster probability pi over individual replicates (see Supplemental Fig. S6 for details). For a given gene, the statistic measures the relative strength of this gene's linkage signal compared to all genes under study. Because the cluster probability for the ith gene, pi, is derived by searching for the maximum-likelihood cluster in a whole-genome molecular-interaction network, it explicitly takes into account information about the whole genome through analysis of the gene clusters.

We evaluate the significance of each gene-specific test statistic using simulated data under the null hypothesis that the disease phenotype is completely unlinked to any part of the genome (Terwilliger et al. 1993), preserving the real pedigree topologies encoded in our data sets and the real frequencies of genetic markers. To compute the null distribution, we generate K simulated data sets (we use K = 1000). For each simulated data set, we repeat the bagged analysis on the original observed data, then derive gene-specific sums of estimated pis. The estimated P-value for a given gene is then the proportion of the simulated replicates for which this gene’s test statistic is higher than the test statistic of the original real data. A given individual P-value shows how likely it is for the corresponding gene to have a share of “susceptibility guilt” as high (or higher) than that observed in the real data simply by chance.

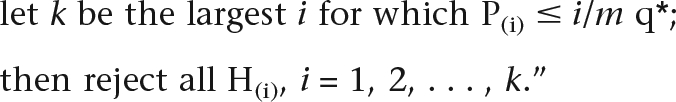

FDR procedure

We used the false discovery rate (FDR) controlling procedure, closely following its description provided by its authors (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995):

“Consider testing H1, H2, . . . , Hm based on the corresponding P-values P1, P2, . . . , Pm.

Let P(1) ≤ P(2) ≤ . . . ≤ P(m) be the ordered P-values, and denote by H(i) the null hypothesis corresponding to P(i). Define the following Bonferroni-type multiple-testing procedure:

|

In our case the null hypothesis Hi for the ith gene is that the gene does not belong to the cluster of genes predisposed to the phenotype under study. We compute “raw” P-values as described in the Gene-Specific Significance Tests section in the main text. Then we use a FDR of q* = 0.5 (or 50%) to identify our suggestive genes.

We compute our P-values by using empirical background distributions of our per-gene statistics (Sum or Max) based on 1000 (or 10,000 in the case of autism-x-rec analysis) simulated data sets under the null hypothesis of unlinked phenotype. For some of the genes it happens that the background distribution of the statistic never achieves a score bigger or equal to the gene’s real-data statistic value. We call such genes “significant” and we assign them P-values equal to half of the minimum possible positive P-value: 0.0005 for the 1000-simulation analysis and 0.00005 for the 10,000-simulation analysis. It is interesting to compute the minimum FDR rate under which such genes will be selected as suggestive, and this can easily be done by reversing the equation above (q* = P(i) × m/k, where k here is the number of genes with P-value of 0.0005 [or 0.00005]). If we assume a network with 4000 genes (about the size of our networks), a single gene with P-value of 0.00005 would survive at a FDR level of 0.2 (20%); unfortunately a single gene with P-value of 0.0005 would not be considered significant by itself (its minimum FDR level is 200%!), but five of them (i.e., in the case of Max statistic for the Schizophrenia [schizophrenia-no-x] reported in Table 1) would survive a FDR level of 0.4 (40%).

See Supplemental material for additional details of the methods.

Acknowledgments

We thank Murat Cokol, Nancy J. Cox, Paul J. Harrison, Lyn Dupré Oppenheim, Mary Sara McPeek, Ani Nenkova, Rita Rzhetsky, and Chani Weinreb for comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM61372 to A.R., GM070789 to T.Z.), the National Science Foundation (0438291 and 0121687 to A.R.), and the Cure Autism Now Foundation (grant to A.R.). We thank the University of Chicago/Argonne National Laboratory Computation Institute for access to their Teraport facility, which is funded by the National Science Foundation under grant MRI-0321297.

Footnotes

[Supplemental material is available online at www.genome.org.]

Article published online before print. Article and publication date are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.075622.107.

References

- Aerts S., Lambrechts D., Maity S., Van Loo P., Coessens B., De Smet F., Tranchevent L.C., De Moor B., Marynen P., Hassan B., et al. Gene prioritization through genomic data fusion. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24:537–544. doi: 10.1038/nbt1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akande E., Xenitidis K., Roberston M.D., Gorman J.M. Autism or schizophrenia: A diagnostic dilemma in adults with intellectual disabilities. J. Psychiatr. Pract. 2004;10:190–195. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200405000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ars E., Serra E., Garcia J., Kruyer H., Gaona A., Lazaro C., Estivill X. Mutations affecting mRNA splicing are the most common molecular defects in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000;9:237–247. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M., Ball C.A., Blake J.A., Botstein D., Butler H., Cherry J.M., Davis A.P., Dolinski K., Dwight S.S., Eppig J.T., et al. Gene Ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacchelli E., Blasi F., Biondolillo M., Lamb J.A., Bonora E., Barnby G., Parr J., Beyer K.S., Klauck S.M., Poustka A., et al. Screening of nine candidate genes for autism on chromosome 2q reveals rare nonsynonymous variants in the cAMP-GEFII gene. Mol. Psychiatry. 2003;8:916–924. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barabasi A.L., Albert R. Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science. 1999;286:509–512. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellman R.E. Adaptive control processes: A guided tour. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y., Yekutieli D. The control of the false discovery rate in multiple testing under dependency. Ann. Statist. 2001;29:1165–1188. [Google Scholar]

- Blain J.F., Aumont N., Theroux L., Dea D., Poirier J. A polymorphism in lipoprotein lipase affects the severity of Alzheimer's disease pathophysiology. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2006;24:1245–1251. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breiman L. Bagging predictors. Mach. Learn. 1996;24:123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante C.D., Fledel-Alon A., Williamson S., Nielsen R., Hubisz M.T., Glanowski S., Tanenbaum D.M., White T.J., Sninsky J.J., Hernandez R.D., et al. Natural selection on protein-coding genes in the human genome. Nature. 2005;437:1153–1157. doi: 10.1038/nature04240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook E.H., Leventhal B.L. The serotonin system in autism. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 1996;8:348–354. doi: 10.1097/00008480-199608000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook E.H., Jr., Courchesne R., Lord C., Cox N.J., Yan S., Lincoln A., Haas R., Courchesne E., Leventhal B.L. Evidence of linkage between the serotonin transporter and autistic disorder. Mol. Psychiatry. 1997;2:247–250. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craddock N., Forty L. Genetics of affective (mood) disorders. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2006;14:660–668. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culbert A.A., Skaper S.D., Howlett D.R., Evans N.A., Facci L., Soden P.E., Seymour Z.M., Guillot F., Gaestel M., Richardson J.C. MAPK-activated protein kinase 2 deficiency in microglia inhibits pro-inflammatory mediator release and resultant neurotoxicity. Relevance to neuroinflammation in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:23658–23667. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513646200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bie T., Tranchevent L.C., van Oeffelen L.M., Moreau Y. Kernel-based data fusion for gene prioritization. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:i125–i132. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B. The jackknife, the bootstrap, and other resampling plans. Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics; Philadelphia, PA: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman I., Rzhetsky A., Vitkup D. Network properties of genes harboring inherited disease mutations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008;105:4323–4328. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701722105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke L., Bakel H., Fokkens L., de Jong E.D., Egmont-Petersen M., Wijmenga C. Reconstruction of a functional human gene network, with an application for prioritizing positional candidate genes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2006;78:1011–1025. doi: 10.1086/504300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri A.R., Mattay V.S., Tessitore A., Kolachana B., Fera F., Goldman D., Egan M.F., Weinberger D.R. Serotonin transporter genetic variation and the response of the human amygdala. Science. 2002;297:400–403. doi: 10.1126/science.1071829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris M.A., Clark J., Ireland A., Lomax J., Ashburner M., Foulger R., Eilbeck K., Lewis S., Marshall B., Mungall C., et al. The Gene Ontology (GO) database and informatics resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D258–D261. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison P.J., Weinberger D.R. Schizophrenia genes, gene expression, and neuropathology: On the matter of their convergence. Mol. Psychiatry. 2005;10:40–68. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helbecque N., Abderrahamani A., Meylan L., Riederer B., Mooser V., Miklossy J., Delplanque J., Boutin P., Nicod P., Haefliger J.A., et al. Islet-brain1/C-Jun N-terminal kinase interacting protein-1 (IB1/JIP-1) promoter variant is associated with Alzheimer's disease. Mol. Psychiatry. 2003;8:413–422. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y.H., Sahoo T., Michaelis R.C., Bercovich D., Bressler J., Kashork C.D., Liu Q., Shaffer L.G., Schroer R.J., Stockton D.W., et al. A mixed epigenetic/genetic model for oligogenic inheritance of autism with a limited role for UBE3A. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2004;131:1–10. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin J.K., Choi J.K., Wasco W., Buxbaum J.D., Kozlowski P.B., Carp R.I., Kim Y.S., Choi E.K. Expression of calsenilin in neurons and astrocytes in the Alzheimer's disease brain. Neuroreport. 2005;16:451–455. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200504040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato T., Iwayama Y., Kakiuchi C., Iwamoto K., Yamada K., Minabe Y., Nakamura K., Mori N., Fujii K., Nanko S., et al. Gene expression and association analyses of LIM (PDLIM5) in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Mol. Psychiatry. 2005;10:1045–1055. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.J., Cox N., Courchesne R., Lord C., Corsello C., Akshoomoff N., Guter S., Leventhal B.L., Courchesne E., Cook E.H., Jr. Transmission disequilibrium mapping at the serotonin transporter gene (SLC6A4) region in autistic disorder. Mol. Psychiatry. 2002;7:278–288. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick S., Gelatt C.D., Jr., Vecchi M.P. Optimization by simulated annealing. Science. 1983;220:671–680. doi: 10.1126/science.220.4598.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klauck S.M., Poustka F., Benner A., Lesch K.P., Poustka A. Serotonin transporter (5-HTT) gene variants associated with autism? Hum. Mol. Genet. 1997;6:2233–2238. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.13.2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauthammer M., Kaufmann C.A., Gilliam T.C., Rzhetsky A. Molecular triangulation: Bridging linkage and molecular-network information for identifying candidate genes in Alzheimer's disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2004;101:15148–15153. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404315101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruglyak L., Daly M.J., Reeve-Daly M.P., Lander E.S. Parametric and nonparametric linkage analysis: A unified multipoint approach. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1996;58:1347–1363. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lage K., Karlberg E.O., Storling Z.M., Olason P.I., Pedersen A.G., Rigina O., Hinsby A.M., Tumer Z., Pociot F., Tommerup N., et al. A human phenome-interactome network of protein complexes implicated in genetic disorders. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007;25:309–316. doi: 10.1038/nbt1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander E., Kruglyak L. Genetic dissection of complex traits: Guidelines for interpreting and reporting linkage results. Nat. Genet. 1995;11:241–247. doi: 10.1038/ng1195-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovlie R., Berle J.O., Stordal E., Steen V.M. The phospholipase C-gamma1 gene (PLCG1) and lithium-responsive bipolar disorder: Re-examination of an intronic dinucleotide repeat polymorphism. Psychiatr. Genet. 2001;11:41–43. doi: 10.1097/00041444-200103000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKusick V.A. Mendelian inheritance in man and its online version, OMIM. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;80:588–604. doi: 10.1086/514346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay T.R. The mind tree: A miraculous child breaks the silence of autism. Arcade; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Nivet-Antoine V., Coulhon M.P., Le Denmat C., Hamon B., Dulcire X., Lefebvre M., Piette F., Davous P., Durand D., Duchassaing D. Apolipoprotein E and bleomycin hydrolase. Polymorphisms: Association with neurodegenerative diseases. Ann. Biol. Clin. (Paris) 2003;61:61–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurmi E.L., Bradford Y., Chen Y., Hall J., Arnone B., Gardiner M.B., Hutcheson H.B., Gilbert J.R., Pericak-Vance M.A., Copeland-Yates S.A., et al. Linkage disequilibrium at the Angelman syndrome gene UBE3A in autism families. Genomics. 2001;77:105–113. doi: 10.1006/geno.2001.6617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivals I., Personnaz L., Taing L., Potier M.C. Enrichment or depletion of a GO category within a class of genes: Which test? Bioinformatics. 2007;23:401–407. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rzhetsky A., Iossifov I., Koike T., Krauthammer M., Kra P., Morris M., Yu H., Duboue P.A., Weng W., Wilbur W.J., et al. GeneWays: A system for extracting, analyzing, visualizing, and integrating molecular pathway data. J. Biomed. Inform. 2004;37:43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahlberg O., Soderstrom H., Rastam M., Gillberg C. Bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and other psychotic disorders in adults with childhood onset AD/HD and/or autism spectrum disorders. J. Neural Transm. 2004;111:891–902. doi: 10.1007/s00702-004-0115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwilliger J.D., Speer M., Ott J. Chromosome-based method for rapid computer simulation in human genetic linkage analysis. Genet. Epidemiol. 1993;10:217–224. doi: 10.1002/gepi.1370100402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu Z., Wang L., Arbeitman M.N., Chen T., Sun F. An integrative approach for causal gene identification and gene regulatory pathway inference. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:e489–e496. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veenstra-VanderWeele J., Gonen D., Leventhal B.L., Cook E.H., Jr. Mutation screening of the UBE3A/E6-AP gene in autistic disorder. Mol. Psychiatry. 1999;4:64–67. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veenstra-VanderWeele J., Christian S.L., Cook E.H., Jr. Autism as a paradigmatic complex genetic disorder. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2004;5:379–405. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.5.061903.180050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma R., Mukerji M., Grover D., B-Rao C., Das S.K., Kubendran S., Jain S., Brahmachari S.K. MLC1 gene is associated with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in Southern India. Biol. Psychiatry. 2005;58:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Wang Q., Wang J. Detection of level and mutation of neurofilament mRNA in Alzheimer's disease. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2002;82:519–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T., Ohnuma T., Shibata N., Ohtsuka M., Ueki A., Nagao M., Arai H. No genetic association between Fyn kinase gene polymorphisms (-93A/G, IVS10+37T/C and Ex12+894T/G) and Japanese sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci. Lett. 2004;360:109–111. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf D.M., Arkin A.P. Motifs, modules and games in bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2003;6:125–134. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(03)00033-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yirmiya N., Pilowsky T., Nemanov L., Arbelle S., Feinsilver T., Fried I., Ebstein R.P. Evidence for an association with the serotonin transporter promoter region polymorphism and autism. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2001;105:381–386. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonan A.L., Alarcon M., Cheng R., Magnusson P.K., Spence S.J., Palmer A.A., Grunn A., Juo S.H., Terwilliger J.D., Liu J., et al. A genomewide screen of 345 families for autism-susceptibility loci. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;73:886–897. doi: 10.1086/378778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]