Abstract

Vascular adhesion protein-1 (VAP-1) is an endothelial cell adhesion molecule involved in leukocyte recruitment. Leukocytes and, in particular, macrophages play an important role in the development of choroidal neovascularization (CNV), an integral component of age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Previously, we showed a role for VAP-1 in ocular inflammation. Here, we investigate the expression of VAP-1 in the choroid and its role in CNV development. VAP-1 was expressed in the choroid, exclusively in the vessels, and colocalized in the vessels of the CNV lesions. VAP-1 blockade with a novel and specific inhibitor significantly decreased CNV size, fluorescent angiographic leakage, and the accumulation of macrophages in the CNV lesions. Furthermore, VAP-1 blockade significantly reduced the expression of inflammation-associated molecules such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) -α, monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP) -1, and intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM) -1. This work provides evidence for an important role of VAP-1 in the recruitment of macrophages to CNV lesions, establishing a novel link between VAP-1 and angiogenesis. Inhibition of VAP-1 may become a new therapeutic strategy in the treatment of AMD.—Noda, K., She, H., Nakazawa, T., Hisatomi, T., Nakao, S., Almulki, L., Zandi, S., Miyahara, S., Ito, Y., Thomas, K. L., Garland, R. C., Miller, J. W., Gragoudas, E. S., Mashima, Y., Hafezi-Moghadam, A. Vascular adhesion protein-1 blockade suppresses choroidal neovascularization.

Keywords: age-related macular degeneration, leukocyte recruitment, macrophage, angiogenesis

Choroidal neovascularization (CNV) is the main cause of severe vision loss in patients with age-related macular degeneration (AMD) (1). Inflammation is critically involved in the formation of CNV lesions (2, 3) and may contribute to the pathogenesis of AMD (2, 3). For example, inflammatory cells are found in surgically excised CNV lesions from AMD patients (4,5,6,7) and in autopsied eyes with CNV (8,9,10). In particular, macrophages have been implicated in the pathogenesis of AMD due to their spatiotemporal distribution in the proximity of the CNV lesions in experimental models and humans (5, 6, 8, 11,12,13,14,15).

Macrophages are a source of proangiogenic and inflammatory cytokines, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (12) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) -α (16), both of which significantly contribute to the pathogenesis of CNV (17, 18). Most of the macrophages found in the proximity of the laser-induced CNV lesions are derived from newly recruited peripheral blood monocytes and not resident macrophages (19). Because macrophages play such a critical role in CNV formation, prevention of monocyte recruitment and infiltration into ocular tissues may ameliorate the development of CNV.

Vascular adhesion protein-1 (VAP-1) is an endothelial adhesion molecule involved in leukocyte recruitment (20, 21). VAP-1 is a homodimeric sialylated glycoprotein expressed on the endothelium of human tissues such as skin, brain, lung, liver, and heart under both normal and inflamed conditions (22,23,24,25). We recently reported the localization of VAP-1 on the endothelium of the retinal vessels and the critical role of this molecule in the recruitment of leukocytes to the eye under inflammatory conditions (26). Inhibition of VAP-1 function with a monoclonal antibody (mAb) suppresses recruitment of cells from the monocyte/macrophage lineage (27), suggesting an important role for VAP-1 in macrophage transmigration under pathological conditions. Because macrophages play a central role in CNV formation, we hypothesized that VAP-1 may regulate macrophage recruitment into ocular tissues under normal and pathological conditions and that its blockade may attenuate CNV formation.

In this study, we investigate the expression and distribution of VAP-1 in the choroidal tissues of normal and laser-injured animals. Furthermore, we examine the role of VAP-1 in CNV formation using a novel and specific inhibitor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals

For reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) detection and immunofluorescence staining of VAP-1 in the choroid, nonpigmented Lewis rats (8–10 wk old, Charles River Laboratories, Inc., Wilmington, MA, USA) were used, whereas laser injury was conducted in pigmented Brown-Norway rats (10–12 wk old, Charles River Laboratories, Inc.) to generate CNV. Rats were housed in plastic cages in a climate-controlled animal facility and were fed laboratory chow and water ad libitum. All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research.

RNA extraction and RT-PCR

Lewis rats were euthanized by an overdose of anesthesia and perfused with PBS [500 ml/kg body weight (BW)]. Eyes were immediately enucleated, and the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) -choroid complex was obtained from the rat eyes and homogenized in extraction reagent (TRIzol Reagent; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). As a control, the retinal tissues were separately obtained and processed. Total RNA was prepared according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and equal amounts (1 μg) of total RNA were reverse-transcribed with a First-Strand cDNA synthesis kit (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) at 37°C for 1 h in a 15 μl reaction volume. PCR was performed using Platinum PCR SuperMix (Invitrogen) with a thermal controller (GeneAmp PCR System 9700; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The thermal cycle was 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 55°C, and 1 min at 72°C, followed by 5 min at 72°C. The reaction was performed for 35 cycles for amplification of VAP-1 and 30 cycles for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) with previously designed primers. The nucleotide sequences of the PCR primers were 5′-GAC CCT CGG ACA ACT GTG TCT T-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCG TTT GTA GAA GCA ACA GTG A-3′ (reverse) for VAP-1 (28) and 5′-TGG CAC AGT CAA GGC TGA GA-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTT CTG AGT GGC AGT GAT GG-3′ (reverse) for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (29). PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis in a 1.5% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide (0.2 μg/ml). The expected sizes of the amplified cDNA fragments of VAP-1 and GAPDH were 341 and 387 bp, respectively. Band densities were quantified using NIH Image 1.41 software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image; developed by Wayne Rasband, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). The expression level of VAP-1 mRNA was normalized by that of GAPDH.

CNV induction

Brown-Norway rats were anesthetized with 0.2–0.3 ml of a 50:50 mixture of 100 mg/ml ketamine and 20 mg/ml xylazine. Pupils were dilated with 5.0% phenylephrine and 0.8% tropicamide. CNV was induced with a 532 nm laser (Oculight GLx, Iridex, Mountain View, CA, USA). Six laser spots (150 mW, 100 μm, 100 ms) were placed in each eye using a slit-lamp delivery system and a cover glass as a contact lens. Production of a bubble at the time of laser confirmed the rupture of the Bruch’s membrane.

Immunohistochemistry

Seven days after laser injury paraffin sections of the choroidal-scleral complex and optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound-embedded sections of the rat eyes were prepared. The sections were incubated with blocking solution (Invitrogen) and then reacted with either mouse monoclonal antibody against rat VAP-1 (1:200; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) or rabbit polyclonal antibody against rat VAP-1 (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA). For the OCT-embedded sections, biotinylated-isolectin B4 (1:100; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was also used to visualize the structure of the vessels in the CNV lesions. Thereafter, the sections were incubated for 30 min at room temperature with secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor® 546; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) or fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) -conjugated streptavidin (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA, USA) and mounted with Vectashield mounting media with 4′,6-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). Photomicrographs were taken with a digital high-sensitivity camera (ORCA-ER C4742–95; Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan) through an upright fluorescent microscope (DM RXA; Leica, Solms, Germany). As a negative control, the primary antibodies were replaced with nonimmune mouse IgG (Dako North America, Inc., Carpinteria, CA, USA).

VAP-1 inhibition

To block VAP-1, we used the specific VAP-1 inhibitor U-V002, developed and provided by R-tech Ueno, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan (26). U-V002 has an IC50 of 0.007 μM against human and 0.008 μM against rat semicarbazide-sensitive amine oxidase (SSAO), whereas its IC50 against the functionally related monoamine oxidase (MAO) -A and MAO-B is >10 μM (26). SSAO inhibitors are subdivided into the main groups of hydrazine derivatives, arylalkylamines, propenyl- and propargylamines, oxazolidinones, and haloalkylamines (30). U-V002 is a new small molecule and a derivative of 1,3-thiazole. After laser injury, the inhibitor (0.3 mg/kg BW) was administered to the animals by daily i.p. injection. Control animals received the same regimen of the vehicle solution (R-tech Ueno, Ltd).

Fluorescein angiography

Seven days after laser injury, vascular leakage from the CNV lesions was assessed using fluorescein angiography (FA), as described previously (31). Briefly, FA was performed in anesthetized animals from VAP-1 inhibitor- or vehicle-treated groups, using a digital fundus camera (TRC 50 IA; Topcon, Paramus, NJ, USA). Fluorescein injections were performed intraperitoneally (0.2 ml of 2% fluorescein; Akorn, Decatur, IL, USA). FA images were evaluated by two masked retina specialists, as described previously (31). Briefly, the grading criteria were as follows. Grade-0 lesions had no hyperfluorescence. Grade-I lesions exhibited hyperfluorescence without leakage. Grade-IIA lesions exhibited hyperfluorescence in the early or midtransit images and late leakage. Grade-IIB lesions showed bright hyperfluorescence in the transit images and late leakage beyond the treated areas. The Grade-IIB lesions were defined as clinically significant, as described previously (32).

Choroidal flatmount preparation

One or 2 wk after laser injury and treatment with VAP-1 inhibitor or vehicle, the size of CNV lesions was quantified using choroidal flat mounts (33). Briefly, rats were anesthetized and perfused through the left ventricle with 20 ml PBS followed by 20 ml of 5 mg/ml fluorescein-labeled dextran (FITC-dextran; MW=2×106, Sigma) in 1% gelatin. The eyes were enucleated and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 3 h. The anterior segment and retina were removed from the eyecup. About 4 to 6 relaxing radial incisions were made, and the remaining RPE-choroidal-scleral complex was flatmounted with Vectashield Mounting Medium (Vector Laboratories) and coverslipped. Pictures of the choroidal flat mounts were taken, and Openlab software (Improvision, Boston, MA, USA) was used to measure the hyperfluorescent areas corresponding to the CNV lesions. The average size of the CNV lesions was then determined and used for the evaluation.

Quantification of the macrophage infiltration

One, 3, and 7 days after laser injury and treatment with either VAP-1 inhibitor or vehicle solution, animals were perfused with 200 ml of PBS/kg BW under deep anesthesia. Subsequently, eyes were enucleated and fixed overnight with 4% PFA, and 10 μm frozen sections of the posterior segment, including the central portion of CNV lesions (6 lesions per eye), were prepared and preblocked (PBS containing 10% goat serum, 0.5% gelatin, 3% BSA, and 0.2% Tween 20). The sections were incubated with mouse monoclonal antibody for ED1, rat homologue of human CD68 (1:100; BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA), and subsequently with the secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488; Molecular Probes). Sections were mounted with Vectashield mounting media (Vector Laboratories). Photographs of the CNV lesions were taken, and the number of ED-1-positive cells was counted. To obtain a quantitative index of macrophage numbers in the CNV lesions, an optical density plot of the selected area was generated by a histogram graphing tool in the Photoshop image-analysis software (version 6.0; Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA), as described previously (14, 34, 35). Image analysis was performed in a masked fashion.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for TNF-α, monocyte chemotactic protein (MCP) -1, and intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM) -1

The RPE-choroid complex was microsurgically isolated from eyes 3 days after photocoagulation. The complex was then placed in 300 μl of lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors and sonicated. The lysate was centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C, and the levels of TNF-α, MCP-1, and ICAM-1 were determined with rat TNF-α (BD Bioscience), MCP-1 (BD Bioscience), and ICAM-1 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits according to the manufacturers’ protocols. Total protein concentration was determined using a Bio-Rad Protein Assay Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) and dilutions of bovine serum albumin (Bio-Rad Laboratories) as standards.

Statistical analysis

All results are expressed as mean ± se with n as indicated. Student’s t test was used for statistical comparison between the groups. The results of the FA gradings were compared using the χ2 test. Differences between the means were considered statistically significant at values of P < 0.05.

RESULTS

VAP-1 expression in the choroid and CNV

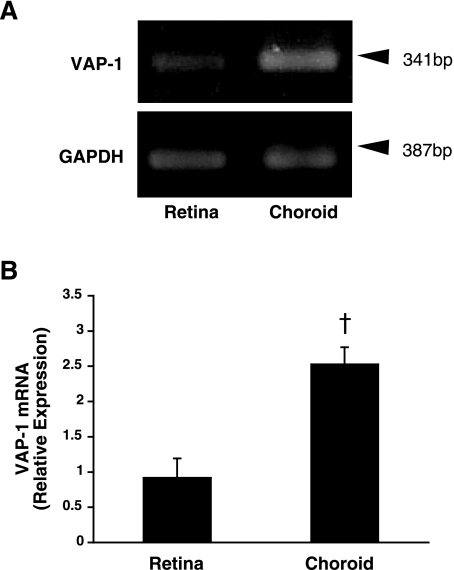

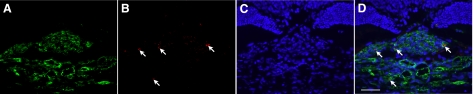

To determine whether VAP-1 is expressed in the choroid, we examined the level of its mRNA expression by RT-PCR and its protein expression by immunofluorescence staining. Because choroidal tissues and RPE cells usually contain melanin (36), which binds to thermostable DNA polymerase and interferes with the PCR amplification (37), we used albino rats that lack melanin. In line with our previous study (26), VAP-1 mRNA was detectable in the retina under normal conditions (Fig. 1). Furthermore, RT-PCR revealed constitutive VAP-1 mRNA expression in the RPE-choroid complex under normal conditions (Fig. 1A). Semiquantitative analysis of the band intensity showed a 2.8-fold higher expression of VAP-1 mRNA in the RPE-choroid complex compared with that in the retinal tissues (n=4 in each group, P<0.01; Fig. 1B). In addition, immunofluorescence staining of sections from the eyes of normal animals showed the expression of VAP-1 protein in the choroid (Fig. 2) and that VAP-1 was exclusively localized in the vessels (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Retinal and choroidal VAP-1 expression. A) RT-PCR amplification of VAP-1 mRNA in the retinal and choroidal tissues obtained from normal rats. B) Averages from densitometric analysis of mRNA bands. Relative VAP-1 mRNA expression values were normalized to the values of GAPDH expression. Values are means ± se (n=4 eyes/group). †P < 0.01.

Figure 2.

Localization of VAP-1 in the choroid. A) Phase-contrast photomicograph of the choroidal-scleral complex. B) Fluorescent micrograph of choroidal tissues immunostained for VAP-1 (Alexa Fluor 546, red). C) Counterstaining for the nuclei with DAPI (blue). D) Merged image. Scale bar = 100 μm.

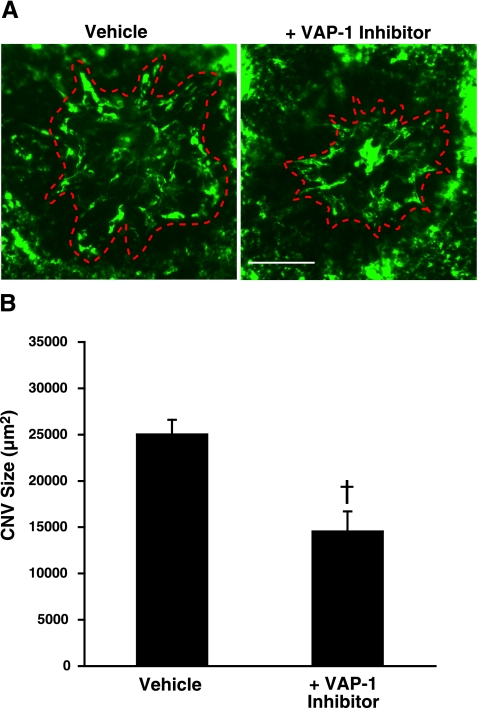

Role of VAP-1 in CNV formation

To examine whether VAP-1 contributes to CNV formation, we photocoagulated the fundus of Brown-Norway rats with and without VAP-1 blockade and quantified the size of the CNV in flat mounts of the RPE-choroid complex. We examined the VAP-1 localization in CNV by immunofluorescence staining. The staining for VAP-1 protein was colocalized with isolectin B4 staining in arborizing CNV (Fig. 3), suggesting that vascular endothelial cells in the CNV lesion also express VAP-1.

Figure 3.

Tissue localization of VAP-1 in a representative CNV lesion. A) Fluorescent micrograph of a laser-induced CNV lesion, immunostained with isolectin B4 (green). B) Fluorescent micrograph of rat choroid, immunostained for VAP-1 (Alexa Fluor 546, red). C) Counterstaining for the nuclei with DAPI (blue). D) Merged image. Arrows indicate the localization of VAP-1 in the CNV and choroidal vessels. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Seven days after laser injury, the animals treated with VAP-1 inhibitor showed a significant decrease in CNV size (14,536±2175 μm2; n=7), compared with vehicle-treated animals (25,026±1586 μm2, n=9, P<0.01) (Fig. 4B). However, 14 days after laser injury, the CNV size in the VAP-1 inhibitor-treated animals was not significantly different compared with the vehicle-treated controls (23,992±1437 vs. 26681±3572 μm2, n=10 and 9 eyes, respectively; P=0.5).

Figure 4.

Effect of VAP-1 blockade on CNV formation. A) Representative micrographs of CNV lesions in the choroidal flat mounts from an animal treated with vehicle or VAP-1 inhibitor. Red dashed line shows the extent of the CNV lesions filled with FITC-dextran in flatmounted choroids. Scale bar = 100 μm. B) Quantitative analysis of CNV size. Bars show the average of CNV size in each group. Values are means ± se (n=7–9 eyes/group). †P < 0.01.

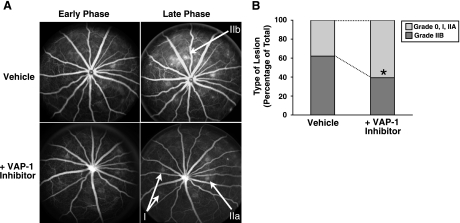

Fluorescent angiography showed that the incidence of the clinically significant CNV lesions, graded as IIB, was significantly decreased in VAP-1 inhibitor-treated animals (41.8%, n=12) in comparison with vehicle-treated animals 7 days post-injury (64.5%, n=11; P<0.05) (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Fluorescein angiography of CNV lesions. A) Representative early phase (1–2 min) and late-phase (6–8 min) fluorescein angiograms of the animals treated with vehicle or VAP-1 inhibitor. Fluorescein angiography was performed at day 7 after laser photocoagulation and the VAP-1 inhibitor treatment. Arrows indicate the respective grades of the various lesions. B) The percentage of lesions graded as 0, I, IIa, defined as no leakage to moderate leakage, and IIb, considered clinically relevant leakage, in vehicle-treated (n=11 eyes) and inhibitor-treated animals (n=12 eyes).

Effect of VAP-1 blockade on macrophage infiltration

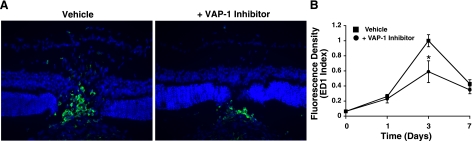

To investigate whether VAP-1 inhibition affects macrophage infiltration into the CNV lesion, we performed immunostaining for ED-1, a macrophage-specific marker, and quantified the number of ED-1 positive cells in the CNV lesions of animals with or without VAP-1 inhibition. Consistent with our previous report (33), we found that macrophages were recruited to the CNV lesion with a peak 3 days after laser injury (Fig. 6). In comparison, the number of accumulated macrophages 3 days after laser injury was significantly reduced by 41% with the blockade of VAP-1 (n=4, P<0.05; Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Effect of VAP-1 blockade on macrophage infiltration in CNV Lesions. A) Representative micrographs of CNV lesions, immunostained for ED-1, in the animals treated with vehicle or VAP-1 inhibitor. B) ED1-positive cells (macrophages) were detected in the RPE-choroid laser lesions day 1 through day 7 after laser injury, with a peak at day 3. The index was normalized to peak response (day 3) of vehicle-treated animals. Values are means ± se (n=4 eyes/time point). *P < 0.05.

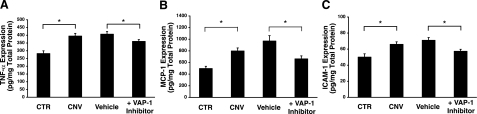

Reduction of inflammatory molecules by VAP-1 blockade

To investigate the mechanisms by which VAP-1 blockade suppresses CNV formation, we measured by ELISA the levels of the inflammation-associated molecules TNF-α, MCP-1, and ICAM-1 in the RPE-choroid complex with or without CNV lesions 3 days after laser injury. Protein levels of TNF-α (282±18 pg/mg), MCP-1 (496±38 pg/mg) and ICAM-1 (50±4 ng/mg) in the RPE-choroid complex of normal rats were significantly increased in the rats with CNV (TNF-α, 395±17 pg/mg, P<0.01; MCP-1, 797±53 pg/mg, P<0.01; ICAM-1, 66±3 ng/mg, P<0.01, respectively) 3 days after laser injury (Fig. 7). The protein levels of TNF-α, MCP-1, and ICAM-1 were significantly reduced in the RPE-choroid complex of the laser-treated animals that received the inhibitor compared with the vehicle controls (TNF-α, 407±17 vs. 360±12 pg/mg, P<0.05; MCP-1, 969±93 vs. 662±52 pg/mg, P<0.01; ICAM-1, 71±4 vs. 57±2 ng/mg, P<0.01, respectively). No statistical difference was found in the protein levels between vehicle-treated and vehicle-untreated CNV animals (TNF-α, P=0.6; MCP-1, P=0.1; ICAM-1, P=0.3, respectively).

Figure 7.

Effect of VAP-1 blockade on inflammation-associated molecules. Bars indicate the average protein levels of TNF-α (A), MCP-1 (B), and ICAM-1 (C) in the RPE-choroidal complex obtained from laser-induced CNV animals treated with vehicle or VAP-1 inhibitor 3 days after laser photocoagulation measured by ELISA. Values are means ± se (n=8–12 eyes). *P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Recently, we showed a critical role for VAP-1 during acute ocular inflammation (26). However, whether VAP-1 contributes to the pathogenesis of AMD is unknown. Because inflammatory processes are involved in the development of AMD, we investigated the role of VAP-1 in the formation of CNV, an integral component of AMD. This work shows a novel link between VAP-1 and angiogenesis.

We found constitutive expression of VAP-1 in the choroid and the retina, suggesting a role for VAP-1 in leukocyte extravasation in both vascular beds. The higher expression of VAP-1 in the choroid compared to the retina may in part be due to the higher vascular density of the choroid compared to the retina. Our histological findings led us to hypothesize that VAP-1 may be involved in CNV by contributing to the inflammatory leukocyte accumulation. Indeed, VAP-1 blockade significantly reduces the CNV size 7 days after laser injury and macrophage accumulation at the peak of CNV growth, 3 days after laser injury. This finding suggests that the reduction of the CNV formation by VAP-1 blockade may primarily be due to suppression of macrophage recruitment (13,14,15). However, 14 days after laser injury, VAP-1 inhibition did not reduce CNV size, suggesting the existence of other VAP-1 independent angiogenic mechanisms that may compensate for the antiangiogenic effect of VAP-1 inhibition 7 days after laser injury. Indeed, emerging evidence suggests that inhibition of a single angiogenic factor may lead to up-regulation of other factors with functional overlap (38).

A variety of cytokines, chemokines, and endothelial adhesion molecules play important roles in the pathogenesis of CNV (16, 39, 40). In the current study, we investigated the impact of VAP-1 blockade on the production levels of selected members of these inflammation-associated molecules. VAP-1 blockade significantly decreases the protein levels of the inflammatory cytokine TNF-α in the RPE-choroid complexes with CNV. Because macrophages in CNV lesions are a source of TNF-α (16), it is possible that the inhibition of macrophage infiltration by VAP-1 blockade may underlie the decreased level of TNF-α in the CNV lesions (17, 18). TNF-α inhibition reduces experimentally induced CNV (18). Furthermore, anti-TNF-α therapy in patients with inflammatory arthritis, who also had AMD, resulted in partial CNV regression and visual acuity improvement (17). Our FA data show fewer lesions with clinically relevant leakage after VAP-1 blockade, suggesting that TNF-α reduction through VAP-1 blockade could be an alternate strategy for treatment of AMD.

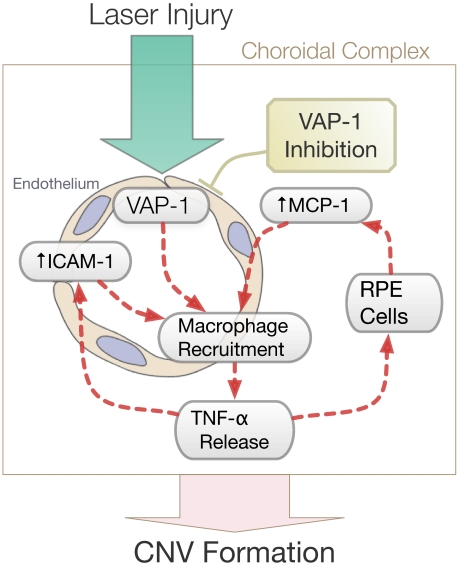

In addition to TNF-α, VAP-1 blockade also significantly reduces the expression of the potent macrophage-recruiting chemokine MCP-1 in the RPE-choroid complex after laser injury. In vitro, TNF-α stimulates the expression of MCP-1 in RPE cells (41,42,43). Our data support a model in which reduced levels of MCP-1 lead to decreased macrophage infiltration. This would cause further reduction of TNF-α release, which in turn would lead to a diminished secretion of MCP-1 in RPE cells (Fig. 8). VAP-1 blockade may thus interrupt this perpetual cascade of inflammatory events that exacerbate CNV formation at the stage of macrophage transmigration.

Figure 8.

Schematic of the role of VAP-1 in laser-induced CNV formation. VAP-1 blockade effectively suppresses key molecular and cellular components in a cascade leading to CNV formation in a laser-induced model of AMD. These elements include expression of inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and adhesion molecules, as well as macrophage infiltration.

We also found that VAP-1 blockade significantly reduces the expression of ICAM-1 in choroidal tissues with CNV. ICAM-1, an endothelial adhesion molecule that regulates leukocyte recruitment, is up-regulated in the RPE-choroid complex during CNV formation (40, 44). Mice deficient for ICAM-1 or its counter receptor, CD18, develop significantly smaller CNV lesions compared with wild-type (45), suggesting a key role for ICAM-1 in CNV formation. The reduction of ICAM-1 expression after VAP-1 blockade in laser-injured eyes may result in lower macrophage infiltration and smaller CNV lesions. Overall, VAP-1 blockade appears to effectively suppress key molecular and cellular components in a cascade leading to CNV formation (Fig. 8). This may be achieved through inhibition of macrophage infiltration and through reduction of the levels of inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and adhesion molecules.

In summary, we show that VAP-1 blockade with a novel and specific inhibitor effectively suppresses CNV development in a laser-induced animal model. VAP-1 inhibition reduces macrophage recruitment to the CNV lesions and secretion of inflammatory factors such as MCP-1 and TNF-α in the choroidal tissues. The current results suggest VAP-1 as an attractive molecular target in the prevention and treatment of AMD.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by U.S. National Institute of Health grants HL086933 and AI050775 (A.H.-M.), research funds from R-tech Ueno, Bausch & Lomb fellowships (K.N., T.N., and S.N.), a Fellowship Award from the Japan Eye Bank Association (K.N. and S.N.), and National Eye Institute core grant EY14104. We are indebted to the Massachusetts Lions Eye Research Fund Inc. for generous funds provided for laboratory equipment used in this project. We thank Research to Prevent Blindness for unrestricted funds awarded to the Department of Ophthalmology at Harvard Medical School. We are grateful to the Marion W. and Edward F. Knight AMD Fund and the American Health Assistance Foundation for support of A.H.-M.’s research. We thank Alexander Schering for his help with the preparation of the manuscript.

References

- Gragoudas E S, Adamis A P, Cunningham E T, Jr, Feinsod M, Guyer D R. Pegaptanib for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2805–2816. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson D H, Mullins R F, Hageman G S, Johnson L V. A role for local inflammation in the formation of drusen in the aging eye. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;134:411–431. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)01624-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donoso L A, Kim D, Frost A, Callahan A, Hageman G. The role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Surv Ophthalmol. 2006;51:137–152. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dastgheib K, Green W R. Granulomatous reaction to Bruch’s membrane in age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994;112:813–818. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1994.01090180111045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killingsworth M C, Sarks J P, Sarks S H. Macrophages related to Bruch’s membrane in age-related macular degeneration. Eye. 1990;4:613–621. doi: 10.1038/eye.1990.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penfold P L, Killingsworth M C, Sarks S H. Senile macular degeneration: the involvement of immunocompetent cells. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1985;223:69–76. doi: 10.1007/BF02150948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarbin M A. Current concepts in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:598–614. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossniklaus H E, Miskala P H, Green W R, Bressler S B, Hawkins B S, Toth C, Wilson D J, Bressler N M. Histopathologic and ultrastructural features of surgically excised subfoveal choroidal neovascular lesions: submacular surgery trials report no. 7. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:914–921. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.7.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson A K, Grossniklaus H E, Capone A Z. Giant-cell reaction in surgically excised subretinal neovascular membrane. Arch Ophthalmol. 1993;111:734–735. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1993.01090060020010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seregard S, Algvere P V, Berglin L. Immunohistochemical characterization of surgically removed subfoveal fibrovascular membranes. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1994;232:325–329. doi: 10.1007/BF00175983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossniklaus H E, Cingle K A, Yoon Y D, Ketkar N, L'Hernault N, Brown S. Correlation of histologic 2-dimensional reconstruction and confocal scanning laser microscopic imaging of choroidal neovascularization in eyes with age-related maculopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:625–629. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.5.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossniklaus H E, Ling J X, Wallace T M, Dithmar S, Lawson D H, Cohen C, Elner V M, Elner S G, Sternberg P., Jr Macrophage and retinal pigment epithelium expression of angiogenic cytokines in choroidal neovascularization. Mol Vis. 2002;8:119–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa-Heidmann D G, Suner I J, Hernandez E P, Monroy D, Csaky K G, Cousins S W. Macrophage depletion diminishes lesion size and severity in experimental choroidal neovascularization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:3586–3592. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai E, Anand A, Ambati B K, van Rooijen N, Ambati J. Macrophage depletion inhibits experimental choroidal neovascularization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:3578–3585. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsumi C, Sonoda K H, Egashira K, Qiao H, Hisatomi T, Nakao S, Ishibashi M, Charo I F, Sakamoto T, Murata T, Ishibashi T. The critical role of ocular-infiltrating macrophages in the development of choroidal neovascularization. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;74:25–32. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0902436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh H, Takagi H, Takagi C, Suzuma K, Otani A, Ishida K, Matsumura M, Ogura Y, Honda Y. The potential angiogenic role of macrophages in the formation of choroidal neovascular membranes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:1891–1898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markomichelakis N N, Theodossiadis P G, Sfikakis P P. Regression of neovascular age-related macular degeneration following infliximab therapy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139:537–540. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.09.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X, Semkova I, Muther P S, Dell S, Kociok N, Joussen A M. Inhibition of TNF-alpha reduces laser-induced choroidal neovascularization. Exp Eye Res. 2006;83:1325–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caicedo A, Espinosa-Heidmann D G, Pina Y, Hernandez E P, Cousins S W. Blood-derived macrophages infiltrate the retina and activate Muller glial cells under experimental choroidal neovascularization. Exp Eye Res. 2005;81:38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koskinen K, Vainio P J, Smith D J, Pihlavisto M, Yla-Herttuala S, Jalkanen S, Salmi M. Granulocyte transmigration through the endothelium is regulated by the oxidase activity of vascular adhesion protein-1 (VAP-1) Blood. 2004;103:3388–3395. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmi M, Jalkanen S. A 90-kilodalton endothelial cell molecule mediating lymphocyte binding in humans. Science. 1992;257:1407–1409. doi: 10.1126/science.1529341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akin E, Aversa J, Steere A C. Expression of adhesion molecules in synovia of patients with treatment-resistant lyme arthritis. Infect Immun. 2001;69:1774–1780. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1774-1780.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaakkola K, Jalkanen S, Kaunismaki K, Vanttinen E, Saukko P, Alanen K, Kallajoki M, Voipio-Pulkki L M, Salmi M. Vascular adhesion protein-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and P-selectin mediate leukocyte binding to ischemic heart in humans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:122–129. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00706-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmi M, Kalimo K, Jalkanen S. Induction and function of vascular adhesion protein-1 at sites of inflammation. J Exp Med. 1993;178:2255–2260. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh B, Tschernig T, van Griensven M, Fieguth A, Pabst R. Expression of vascular adhesion protein-1 in normal and inflamed mice lungs and normal human lungs. Virchows Arch. 2003;442:491–495. doi: 10.1007/s00428-003-0802-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda K, Miyahara S, Nakazawa T, Almulki L, Nakao S, Hisatomi T, She H, Thomas K L, Garland R C, Miller J W, Gragoudas E S, Kawai Y, Mashima Y, Hafezi-Moghadam A. Inhibition of vascular adhesion protein-1 suppresses endotoxin-induced uveitis. FASEB J. 2007;22:1094–1103. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9377com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merinen M, Irjala H, Salmi M, Jaakkola I, Hanninen A, Jalkanen S. Vascular adhesion protein-1 is involved in both acute and chronic inflammation in the mouse. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:793–800. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62300-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martelius T, Salmi M, Wu H, Bruggeman C, Hockerstedt K, Jalkanen S, Lautenschlager I. Induction of vascular adhesion protein-1 during liver allograft rejection and concomitant cytomegalovirus infection in rats. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:1229–1237. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64638-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashiro K, Kiryu J, Tsujikawa A, Honjo M, Nonaka A, Miyamoto K, Honda Y, Tanihara H, Ogura Y. Inhibitory effects of antithrombin III against leukocyte rolling and infiltration during endotoxin-induced uveitis in rats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:1553–1560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matyus P, Dajka-Halasz B, Foldi A, Haider N. Semicarbazide-sensitive amine oxidase: current status and perspectives. Curr Med Chem. 2004;11:1285–1298. doi: 10.2174/0929867043365305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zambarakji H J, Nakazawa T, Connolly E, Lane A M, Mallemadugula S, Kaplan M, Michaud N, Hafezi-Moghadam A, Gragoudas E S, Miller J W. Dose-dependent effect of pitavastatin on VEGF and angiogenesis in a mouse model of choroidal neovascularization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:2623–2631. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krzystolik M G, Afshari M A, Adamis A P, Gaudreault J, Gragoudas E S, Michaud N A, Li W, Connolly E, O'Neill C A, Miller J W. Prevention of experimental choroidal neovascularization with intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody fragment. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:338–346. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.3.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- She H, Nakazawa T, Matsubara A, Hisatomi T, Young T A, Michaud N, Connolly E, Hafezi-Moghadam A, Gragoudas E S, Miller J W. Reduced photoreceptor damage after photodynamic therapy through blockade of nitric oxide synthase in a model of choroidal neovascularization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:2268–2277. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehr H A, Mankoff D A, Corwin D, Santeusanio G, Gown A M. Application of Photoshop-based image analysis to quantification of hormone receptor expression in breast cancer. J Histochem Cytochem. 1997;45:1559–1565. doi: 10.1177/002215549704501112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehr H A, van der Loos C M, Teeling P, Gown A M. Complete chromogen separation and analysis in double immunohistochemical stains using Photoshop-based image analysis. J Histochem Cytochem. 1999;47:119–126. doi: 10.1177/002215549904700113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiter J J, Delori F C, Wing G L, Fitch K A. Retinal pigment epithelial lipofuscin and melanin and choroidal melanin in human eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1986;27:145–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhart L, Bach J, Ban J, Tschachler E. Melanin binds reversibly to thermostable DNA polymerase and inhibits its activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;271:726–730. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P. Angiogenesis in life, disease and medicine. Nature. 2005;438:932–936. doi: 10.1038/nature04478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousins S W, Espinosa-Heidmann D G, Csaky K G. Monocyte activation in patients with age-related macular degeneration: a biomarker of risk for choroidal neovascularization? Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:1013–1018. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.7.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai N, Oike Y, Izumi-Nagai K, Urano T, Kubota Y, Noda K, Ozawa Y, Inoue M, Tsubota K, Suda T, Ishida S. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor-mediated inflammation is required for choroidal neovascularization. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2252–2259. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000240050.15321.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian Z M, Elner S G, Strieter R M, Kunkel S L, Lukacs N W, Elner V M. IL-4 potentiates IL-1beta- and TNF-alpha-stimulated IL-8 and MCP-1 protein production in human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Curr Eye Res. 1999;18:349–357. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.18.5.349.5353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elner S G, Strieter R M, Elner V M, Rollins B J, Del Monte M A, Kunkel S L. Monocyte chemotactic protein gene expression by cytokine-treated human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Lab Invest. 1991;64:819–825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elner V M, Strieter R M, Elner S G, Baggiolini M, Lindley I, Kunkel S L. Neutrophil chemotactic factor (IL-8) gene expression by cytokine-treated retinal pigment epithelial cells. Am J Pathol. 1990;136:745–750. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen W Y, Yu M J, Barry C J, Constable I J, Rakoczy P E. Expression of cell adhesion molecules and vascular endothelial growth factor in experimental choroidal neovascularisation in the rat. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998;82:1063–1071. doi: 10.1136/bjo.82.9.1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai E, Taguchi H, Anand A, Ambati B K, Gragoudas E S, Miller J W, Adamis A P, Ambati J. Targeted disruption of the CD18 or ICAM-1 gene inhibits choroidal neovascularization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:2743–2749. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]