Abstract

Synaptic integration is modulated by inhibition onto the dendrites of postsynaptic cells. However, presynaptic inhibition at axonal terminals also plays a critical role in the regulation of neurotransmission. In contrast to the development of inhibitory synapses onto dendrites, GABAergic/glycinergic synaptogenesis onto axon terminals has not been widely studied. Because retinal bipolar cells receive subclass-specific patterns of GABAergic and glycinergic presynaptic inhibition, they are a good model for studying the development of inhibition at axon terminals. Here, using whole cell recording methods and transgenic mice in which subclasses of retinal bipolar cells are labeled, we determined the temporal sequence and patterning of functional GABAergic and glycinergic input onto the major subclasses of bipolar cells. We found that the maturation of GABAergic and glycinergic synapses onto the axons of rod bipolar cells (RBCs), on-cone bipolar cells (on-CBCs) and off-cone bipolar cells (off-CBCs) were temporally distinct: spontaneous chloride-mediated currents are present in RBCs earlier in development compared with on- and off-CBC, and RBCs receive GABAergic and glycinergic input simultaneously, whereas in off-CBCs, glycinergic transmission emerges before GABAergic transmission. Because on-CBCs show little inhibitory activity, GABAergic and glycinergic events could not be pharmacologically distinguished for these bipolar cells. The balance of GABAergic and glycinergic input that is unique to RBCs and off-CBCs is established shortly after the onset of synapse formation and precedes visual experience. Our data suggest that presynaptic modulation of glutamate transmission from bipolar cells matures rapidly and is differentially coordinated for GABAergic and glycinergic synapses onto distinct bipolar cell subclasses.

INTRODUCTION

The development of GABAergic and glycinergic synapses onto dendrites of neurons has been studied extensively at the molecular and cellular levels (Ben-Ari et al. 2007; Huang et al. 2007; Moss and Smart 2001). However, GABAergic and glycinergic neurons also synapse onto the axon initial segment and axonal terminals of many neuronal cell types in the nervous system (Engelman and MacDermott 2004). For example, axo-axonic synapses that modulate presynaptic transmitter release are found on pyramidal neurons in the cortex, mossy fiber terminals in the hippocampus, the calyx of Held in the auditory brain stem, parallel fibers of the cerebellum, and extensor afferents of the spinal cord (Jang et al. 2006; Rudomin and Schmidt 1999; Ruiz et al. 2003; Stell et al. 2007; Szabadics et al. 2006; Turecek and Trussell 2001). Despite the importance of axo-axonic synapses in regulating circuit function, much remains to be understood about the development of these synapses. In particular, although the molecular mechanisms directing GABAergic synaptogenesis at the axon initial segment in pyramidal cells has been investigated (Ango et al. 2004), it is unclear how such synapses are established at axon terminals during development. Thus far, previous studies of the calyx of Held demonstrated that the balance of GABAergic and glycinergic inputs at this afferent terminal alters with maturation: GABAergic inputs are initially dominant, whereas glycinergic inputs appear later as GABAergic inputs are downregulated (Turecek and Trussell 2002). Whether across other systems, the balance of GABAergic and glycinergic inputs is determined early in synaptogenesis or whether the adult axo-axonic innervation patterns are shaped gradually with development has not been addressed.

Here we take advantage of the well-characterized patterns of inhibition onto retinal bipolar cells of the mammalian retina to determine how GABAergic and glycinergic synapses are established at axon terminals during development. The glutamatergic bipolar cell output to ganglion cells is modulated by presynaptic inhibition from GABAergic and glycinergic amacrine cells onto the bipolar cell's axonal terminal (Dong and Werblin 1998; Euler and Wassle 1998; Lukasiewicz and Werblin 1994; Pan and Lipton 1995). Retinal bipolar cells are classified as rod bipolar cells (RBCs), on-cone bipolar cells (on-CBCs), or off-cone bipolar cells (off-CBCs) (Wassle 2004). on-CBCs receive primarily ionotropic GABA receptor-mediated input and little glycinergic input, whereas RBCs receive significant GABAergic and glycinergic input (Eggers and Lukasiewicz 2006b; Eggers et al. 2007). off-CBCs receive a dominant glycinergic input and a relatively small ionotropic GABA receptor-mediated input (Eggers et al. 2007; Ivanova et al. 2006). These contrasting combinations of GABAergic and glycinergic inputs onto different bipolar cell subclasses in the adult retina thus provide a good model for examining how subclass-specific patterns of GABAergic/glycinergic inputs at axon terminals emerge during development.

We thus recorded spontaneous postsynaptic outward currents from the major subclasses of mouse bipolar cells in the mature retina and in the neonatal retina during the period when GABAergic and glycinergic amacrine interneurons contact the bipolar cells. Our findings revealed that the relative contributions of GABAergic and glycinergic drive characteristic of the adult pattern are established shortly after synaptogenesis.

METHODS

Bipolar cell identification in transgenic mice

To readily identify the major bipolar cell subclasses (RBCs, on- and off-CBCs) for whole cell patch-clamp recordings, we used three transgenic mouse lines in which subsets of bipolar cells express fluorescent proteins. The generation of the Grm6-GFP transgenic line (Morgan et al. 2006) and Thy1-mitoCFP-P line (Misgeld et al. 2007) have been described previously. In the Grm6-YFPstop-Kir2.1-CFP transgenic line, the mGluR6 promoter is upstream from a YFP-stop sequence that is flanked by LoxP sites. Kir2.1-CFP (provided by V. Murphy, Harvard University) is expressed on excision of the stop cassette by Cre-recombination (D. Kerschensteiner and R.O.L. Wong, unpublished data). In the absence of Cre-recombinase, YFP is expressed in a subset of on-bipolar cells; for the current study, we refer to this line as Grm6-YFP.

In these transgenic mouse lines, fluorescent and occasionally neighboring nonfluorescent bipolar cells were recorded using patch electrodes that contained sulforhodamine B (0.005%, Sigma). During the recording, bipolar cells were dye-filled, and images of the cells were subsequently captured using a Retiga ExiFast cooled CCD camera and Metamorph (Invitrogen) image acquisition software. Classification of bipolar cells as RBCs, on-CBCs and off-CBCs was carried out based on the morphology and the stratification depth of their axon terminals in the IPL (Supplementary Fig. S11 ).

Preparation of mouse retinal slices

Mice were anesthetized with 4% halothane and killed by decapitation in accordance with the IACUC guidelines and regulations of Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO and University of Washington, Seattle, WA. Retinal slice preparation has been described in detail by Eggers and Lukasiewicz (2006a). In brief, the eyecup was incubated for 20 min in artificial cerebral spinal fluid (ACSF; see Solution and drug) containing 0.5 mg/ml hyaluronidase (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) to remove any remaining vitreous. The retinae were then dissected from the eyecup, cut into half and put onto filter paper (0.22 μm pore size, Millipore) with the photoreceptor layer facing up. Vertical retinal slices of 200 μm thickness were cut using a standard technique (Werblin 1978) and subsequently stored in carbogenated ACSF at room temperature.

Whole cell recordings and data analysis

Whole cell recordings were made from bipolar cells from mouse retinal slices as previously described by Eggers and Lukasiewicz (2006a). The resistance of the electrodes with standard solutions usually ranged between 4 and 6 MΩ. Liquid junction potentials of 15 mV were corrected before the measurement with the pipette offset function. Series resistances ranged from 23 to 65 MΩ (mean: 40.2 ± 3.6 MΩ, n = 13) for bipolar cells and from 22 to 73 MΩ (mean: 42.1 ± 2.6 MΩ, n = 27) for amacrine cells. The series resistance measured in the developing retina was within the range of values in the adult retina (Singer and Diamond 2003; Tamalu and Watanabe 2007). Series resistance and capacitance of pipettes as well as cell capacitance were not compensated. Seal resistances >1 GΩ were routinely obtained. Bipolar cells were voltage-clamped at 0 mV, the reversal potential for currents through nonselective cation receptor channels to record spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents (sIPSCs). As we slowly ramped the holding potential from −75 to 0 mV over several seconds, outward currents were sometimes elicited during the ramp. These currents likely represent feedback from amacrine cells that have been observed in previous studies (Chavez et al. 2006; Hartveit 1999). Their rare occurrence in our recordings precluded comparison of their characteristics across development.

Spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (sEPSCs) in amacrine cells were recorded at a holding potential of −60 mV, the reversal for the sIPSCs. The holding current was monitored during the experiment, and recordings with shifting holding currents were aborted. All experiments were carried out at room temperature (20–22°C).

Data acquisition was performed with an Axopatch 200B amplifier with a frequency of 5 kHz using the Clampex software (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA). Signals were 2 kHz Bessel filtered. We analyzed sIPSCs and sEPSCs with amplitudes >4 pA that could be distinguished from background noise with the MiniAnalysis program (Synaptosoft, Leonia, NJ). The frequency as well as the amplitudes of postsynaptic currents were examined and further processed using Origin software (Microcal, Northampton, MA). To quantify parameters of synaptic events, the mean frequency ±SE, the mean amplitude ±SE (sEPSCs), and the median amplitude ±SE (sIPSCs) were determined. We calculated the median amplitude for sIPSCs instead of the mean amplitude because the sIPSC amplitudes were not normally distributed. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test, signed-rank test, or the paired/unpaired t-test was used to test for statistical significance as indicated.

Solution and drugs

The extracellular solution (ACSF) contained (in mM) 122.5 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, 2 CaCl2, and 20 glucose, adjusted to pH 7.4 with 95% O2-5% CO2. The intracellular solution contained in (mM) 120 cesium gluconate, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 Na-HEPES, 11 EGTA, and 10 TEA-Cl and was adjusted to pH 7.2 with CsOH. Under our experimental conditions, the calculated chloride equilibrium potential was −59.3 mV. To block glycine receptors and GABAA receptors, strychnine hydrochloride (0.5 μM) and bicuculline methobromide (50 μM) or SR-95531 (5 μM) were used, respectively. GABAC receptors were blocked with (1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyridine-4yl) methyphospinic acid (TPMPA, 75 μM). Ionotropic glutamate receptors were blocked with a combination of 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX, 20 μM) and d-2-amino-7-phosphonoheptanoic acid (AP-7, 40 μM). Tetrodotoxin (TTX, 0.5 μM) was used to block voltage-gated sodium channels. In some experiments, kainic acid (KA, 10 μM) was added to the extracellular solution to increase transmitter release from amacrine cells. All drugs were purchased from Sigma. Solutions in the recording chamber were exchanged using a gravity-driven superfusion system previously described (Lukasiewicz and Roeder 1995).

Immunocytochemistry

After enucleation, the lens was removed and the eyecup was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.3, for 20 min. The eyecup was washed in 0.1 M PBS, and the retina was removed and cryoprotected in sucrose solution (15–30% in 0.1 M PBS). Pieces of the retina were sectioned vertically at 30 μm thickness on a cryostat, and the sections were collected on glass slides.

For immunolabeling, the sections were blocked in 10% normal goat serum (NGS, 1h, in 0.1 M PBS) and subsequently incubated with primary antibodies (overnight, in 0.1 M PBS containing 0.1% Triton-X 100 and 5% NGS). The following antibodies were used: Anti-calcium-binding protein 5 (CaBP5, 1:1000, gift of F. Haeseleer and K. Palczewski), anti-glycine (1:1,000, gift of D. Pow), anti-protein kinase C (1:1,000, Sigma), anti-neurokinin 3 receptor (NK3R, 1:500, gift of A. Hirano), anti-recoverin (1:1,000, Chemicon). Yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) and cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) fluorescence signals were amplified with anti-GFP antibodies (1:1,000, Molecular Probes). After sections were washed in 0.1 M PBS, Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:1,000, Molecular Probes) were applied for 90 min. Stained retina sections were imaged on a FV-1000 Olympus laser scanning microscope with an Olympus 60× (1.4 NA) objective. Image processing was performed using Metamorph (Invitrogen) and Photoshop CS (Adobe) software.

RESULTS

RBCs, on-CBCs and off-CBCs are labeled in transgenic mouse lines

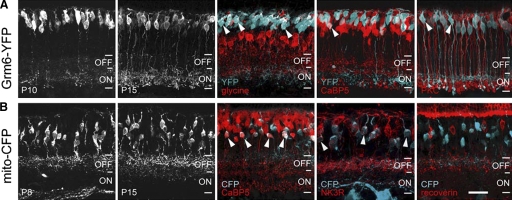

In the mouse retina, there are ≥10 types of bipolar cells: types 1–4 are off-CBCs, types 5–9 are on-CBCs, and there is one type of RBC (Ghosh et al. 2004). In the Grm6-GFP mouse line, virtually all RBCs and on-CBCs express GFP (Morgan et al. 2006). In the Grm6-YFP line, relatively fewer on-bipolar cells express cytosolic YFP, resulting in a less dense distribution of labeled cells. YFP expression was evident in cell bodies in the inner nuclear layer (INL) at P9 (data not shown). From P10 onward, dendrites and axons were labeled (Fig. 1 A). To determine whether the YFP-labeled cells were on-CBCs and/or RBCs, we performed double-immunolabeling experiments for glycine, CaBP5 and PKC at P15 (Fig. 1A). On-CBCs label for glycine, which is known to diffuse from AII amacrine cells to on-CBCs via gap junctions (Vaney et al. 1998). YFP-expressing cell bodies contained glycine, indicating that these were on-CBCs. Three types of bipolar cells in the mouse express CaBP5: off-CBC type 3, on-CBC type 5, and RBCs (Ghosh et al. 2004; Haverkamp et al. 2003). Very few YFP-labeled cells were CaBP5-positive. Some YFP-expressing bipolar cells were co-localized with PKC, indicating that a subset of RBCs expresses YFP in this transgenic line. Thus in the Grm6-YFP mouse line, on-CBCs and some RBCs were fluorescently labeled. Compared with the Grm6-GFP line, the relatively sparse labeling of bipolar cells in the Grm6-YFP line enabled us to more readily target on- CBCs and RBCs.

FIG. 1.

Identification of on- and off-bipolar cells in fluorescently labeled transgenic mice. A: cross-section of retina from Grm6-YFP transgenic mice. Examples of double-labeling for glycine, CaBP5, and protein kinase C at P15 to P31. Examples of co-localized cell bodies are indicated by arrowheads. B: cross-section of retina from Thy1-mitoCFP-P (mito-CFP) transgenic mice. Double-labeling against CaBP5, NK3R, and recoverin; examples of co-localized cell bodies are indicated by arrowheads. OFF, ON: off and on-sublaminae of the IPL. Scale bar, 20 μm.

In the Thy1-mitoCFP-P (mito-CFP) mouse line, CFP is expressed in neuronal mitochondria under the control of the Thy1 promoter. As shown in Fig. 1B, the cell bodies of CFP-expressing bipolar cells were found primarily within the middle of the INL, a location that was unchanged with age. The stratification depth of the CFP-labeled bipolar cell axons was mostly restricted to the off-sublamina of the inner plexiform layer (IPL). To confirm that off-CBCs express CFP, we performed antibody staining against CaBP5, NK3R (marker for off-CBC types 1 and 2) and recoverin (marker for off-CBC type 2; Fig. 1B). We observed numerous cell bodies with CFP and CaBP5 co-localization, suggesting that some CFP-positive bipolar cells are type 3 off-CBCs. To assess whether the remaining off-CBCs belonged to the types 1 and/or 2, we carried out immunolabeling for NK3R and recoverin. We found that CFP-positive off-CBCs also showed labeling for NK3R. In contrast, recoverin, present in type 2 off-CBCs, was absent in the CFP-expressing bipolar cells. Thus in the Thy1-mitoCFP-P mouse line, off-CBCs types 1 and 3 were labeled. Some amacrine cells and ganglion cells also express CFP in the Thy1-mitoCFP-P line; their dendrites contribute to sparse labeling in the IPL (Misgeld et al. 2007).

Because in neonatal retinal slice preparations, identification of bipolar cell types based only on the morphology and stratification depth of the axon terminal was difficult, we limited our classification in the patch-clamp experiments to the three major subclasses of bipolar cells that were readily distinguished across development and in the adult (RBCs, on- and off-CBCs).

RBCs receive inhibitory input before CBCs

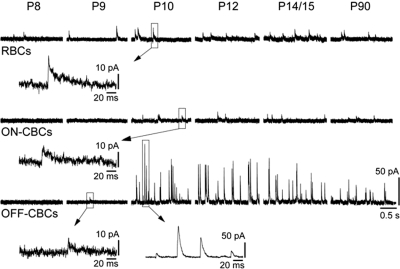

To determine when GABAergic/glycinergic synapses onto each of the bipolar cell subclasses are established, we recorded sIPSCs in RBCs (n = 85), on-CBCs (n = 58), and off-CBCs (n = 88) from P7 to P15 and at P90.

Example recordings of different bipolar cell subclasses are shown in Fig. 2. sIPSCs were first observed in RBCs at P8 (Fig. 2; Supplementary Table S1). Between P8 and P10, 43% of the RBCs had sIPSCs. After P10, sIPSCs were recorded from a larger fraction of RBCs (89%; Supplementary Table S1). In contrast, sIPSCs were present in on-CBCs only from P10 onward. From P10 and P14, only 46% of all recorded on-CBCs revealed spontaneous inhibitory input, whereas 88% of all on-CBCs at P90 showed sIPSCs. A small proportion (12%) of off-CBCs had detectable sIPSCs at P8 and P9. From P10 onwards, we observed sIPSCs in all recorded off-CBCs (Supplementary Table S1).

FIG. 2.

Developmental emergence of spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents (sIPSCs) in bipolar cells. Representative whole cell recordings showing spontaneous synaptic activity of the 3 major bipolar cell subclasses across development. Bipolar cells were voltage-clamped at 0 mV to record chloride-mediated postsynaptic currents.

It is possible that the absence of sIPSCs, particularly in the immature bipolar cells may be because spontaneous amacrine cell transmission onto bipolar cells is weak at the early ages. We thus added the ionotropic glutamate receptor agonist kainic acid (KA, 10 μM) to the extracellular solution to enhance transmitter release from amacrine cells (Eggers and Lukasiewicz 2006b; Frech and Backus 2004). KA evoked chloride-mediated postsynaptic currents in 33% of on-CBCs and 50% of off-CBCs at P9. At P8, KA evoked chloride-mediated postsynaptic currents in 57% of all RBCs but failed to do so for either CBC population (Supplementary Table S2).

In summary, our findings show that inhibitory synapses are functionally established earlier onto RBCs than onto CBCs as a significant fraction of RBCs had sIPSCs by P8, whereas sIPSCs could be routinely detected in off-CBCs only by P10. On-CBCs showed sIPSCs by P10, but the proportion of on-CBCs with sIPSCs was low throughout development and in the adult retina.

sIPSCs of bipolar cells are generated in the IPL

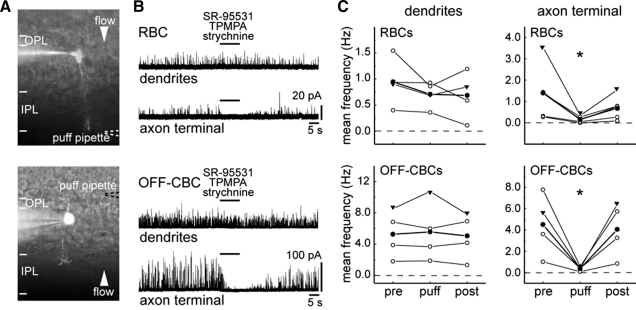

Previous studies suggest that bipolar cells are contacted at their dendrites by GABAergic horizontal cells and at their axon terminals by GABAergic/glycinergic amacrine cells (Cui et al. 2003; Gillette and Dacheux 1995; Pan and Lipton 1995; Suzuki et al. 1990; Varela et al. 2005). To determine whether the recorded sIPSCs were generated at the dendrites and/or axon terminals of the bipolar cells, a cocktail of glycine and GABA receptor antagonists, strychnine, SR-95531, and TPMPA, was focally applied either onto the dendrites or onto the axon terminals during the recording (Fig. 3 A).

FIG. 3.

Bipolar cell sIPSCs are generated in the IPL. A: images showing the location of a puff pipette (- - -) containing GABA and glycine receptor antagonists during focal application of these antagonists at axon terminals (top) or dendrites (bottom) of bipolar cells during whole cell recording. B: representative traces of a rod bipolar cell (RBC) and an off-cone bipolar cell (OFF-CBC) showing effects on the sIPSCs on puffing SR-95531 (5 μM), (1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyridine-4yl) methyphospinic acid (TPMPA, 75 μM), and strychnine (0.5 μM). C: quantification of mean frequencies sampled before (pre; 30-s period before puffing), during (10-s puff), and after (post; 30 s after the puff) the puff (n = 4 and n = 5 for puffs onto RBC dendrites and axons, respectively. Puffs onto off-CBC dendrites and axon terminals: n = 4 for each set of experiments). Mean frequency of each cell is indicated (○). ▾, measures of cells shown in B. The averaged mean frequency of the recorded population is indicated by filled circles. All recordings were performed from P11 to P13. The reduction in mean frequency on puffing antagonists at the axon terminals is statistically significant (*, paired t-test, P < 0.05).

We found that in RBCs and off-CBCs, sIPSCs persisted after a 10-s puff when applied to the dendrites. In contrast, if the puff was directed to axon terminals, postsynaptic currents were eliminated (Fig. 3B). To quantify the data, we determined the mean sIPSC frequency within a 30-s period before the puff, during the period of antagonist action (10-s sampling duration), and 30 s after the termination of the puff.

For RBCs, the mean frequency of sIPSCs after the puff onto the axon terminal (n = 5), but not onto the dendrites (paired t-test, P = 0.22 for dendrites, n = 4), was significantly reduced. Similar results were obtained from off-CBCs (paired t-test, P = 0.68 for dendrites, n = 4, each experiment; Fig. 3C). Pharmacological experiments were more difficult to perform for the on-CBCs because of their relatively low baseline sIPSC rate. However, in four on-CBCs with measurable sIPSCs, we obtained results that were similar to those for RBCs and off-CBCs. Puffing onto two on-CBC axon terminals decreased their mean sIPSC frequency [cell 1: 0.9 Hz (pre), 0 Hz (puff), 0.4 Hz (post); cell 2: 0.1 Hz (pre), 0 Hz (puff), 0.2 Hz (post)]. Locally applying the antagonist cocktail onto the dendrites of two on-CBCs did not alter their mean sIPSC frequency [cell 1: 0.4 Hz (pre), 0.3 Hz (puff), 0.2 Hz (post); cell 2: 0.5 Hz (pre), 0.6 Hz (puff), 0.4 Hz (post)]. Thus our findings suggest that under our recording conditions, bipolar cell sIPSCs originate largely from amacrine cell input onto their axon terminals rather than from horizontal cell input onto their dendrites.

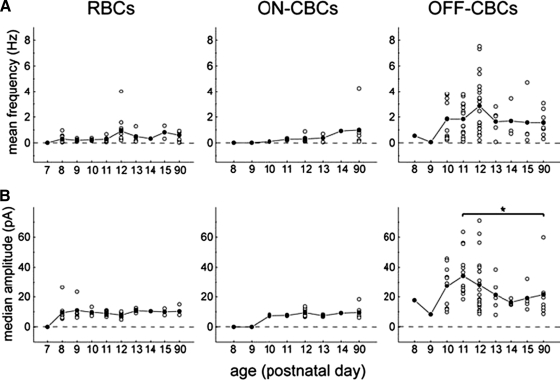

Amplitude and frequency of sIPSCs change during development in off-CBCs but not in on-CBCs and RBCs

To gain a more quantitative understanding of the development of the presynaptic inhibition onto bipolar cells, we determined the mean frequencies and median amplitudes of sIPSCs in the three bipolar cell subclasses at different postnatal days. Changes in amplitudes may reflect a change of postsynaptic receptor number, whereas changes in frequency may reflect changes in the rate of transmitter release. In RBCs, as well as in on-CBCs, the mean frequency was relatively unchanged with age [Wilcoxon rank-sum test, P = 0.14 for RBCs (P8 and P90), P = 0.18 for on-CBCs (P10 and P90)] and generally remained <1 Hz (Fig. 4 A). However, the mean sIPSC frequency of off-CBCs was low prior to P10 but rapidly increased to a maximum at P12 and remained relatively unchanged thereafter [Wilcoxon rank-sum test, P = 0.25 (P12 and P90); Fig. 4A and Supplementary Table S1].

FIG. 4.

Development of inhibitory synaptic activity in different bipolar cell subclasses. sIPSCs were recorded in cells voltage-clamped at 0 mV. Mean frequency (A) and median amplitude (B) for each cell are indicated (○); the mean frequency and median amplitude for the population of cells at each age are represented by • (n = 48 for RBCs, n = 23 for on-CBCs, and n = 67 for off-CBCs). *, significant difference between P11 and P90 (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, P < 0.05).

The median amplitudes of sIPSCs in RBCs and on-CBCs did not change after the age that they were first detected [Wilcoxon rank-sum test, P = 0.23 for RBCs (P8 and P90), P = 0.52 for on-CBCs (P10 and P90); Fig. 4B and Supplementary Table S1]. In contrast, the median amplitude of off-CBCs was more variable during development: it was small at P8/9, thereafter it increased and peaked at P11, but subsequently it was significantly decreased by P90. Application of KA appeared to increase the mean frequency of sIPSCs for all three bipolar cell subclasses from P8 to P11 (Supplementary Table S2). The median amplitudes of sIPSCs in the presence of KA did not alter in comparison to median amplitudes recorded without KA (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, P = 0.14 at P8 and P = 0.73 at P9 for RBCs).

Thus on- (on-CBC and RBC) bipolar cells and off-CBCs differ in the developmental characteristics of their sIPSCs.

Differential development of glycinergic and GABAergic inputs onto RBCs and off-CBCs

In the mature retina, presynaptic inhibition modulating glutamatergic transmission from distinct bipolar cell subclasses is differentially mediated by their complement of GABAA, GABAC, and glycine receptors. RBCs receive significant GABAergic and glycinergic input, whereas the majority of inhibitory input onto off-CBCs is glycinergic (Eggers and Lukasiewicz 2006b; Eggers et al. 2007; Ivanova et al. 2006). These subclass-specific combinations of receptors shape the temporal characteristics of transmission from each major bipolar cell subclass to the ganglion cells.

Because on-CBCs have a very low sIPSC baseline frequency, we compared when during development the subclass-specific balance of glycinergic and GABAergic input is established for RBCs and off-CBCs. GABAA receptor-mediated currents were pharmacologically isolated by application of the glycine receptor antagonist, strychnine (0.5 μM). To confirm that strychnine-resistant currents were GABAA receptor-mediated, the GABAA receptor antagonist, bicuculline (50 μM), was subsequently co-applied with strychnine in all experiments. Glycinergic sIPSCs were isolated by using the GABAA receptor antagonist, SR-95531 (5 μM), and the GABAC receptor antagonist, TPMPA (75 μM). sIPSCs that remained in the presence of SR-95531 and TPMPA were judged to be glycinergic if they were abolished by strychnine.

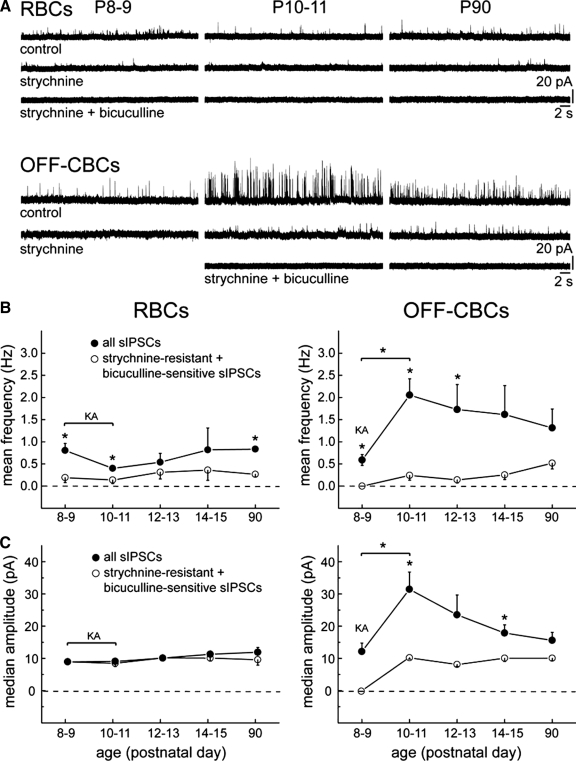

We first addressed whether RBCs receive glycinergic and/or GABAA-receptor mediated input on the first 2 day (P8/9) when sIPSCs were detected in a population of RBCs. Application of strychnine significantly reduced the mean frequency of sIPSCs (Fig. 5, A and B). The few sIPSCs that persisted were abolished by bicuculline, indicating that they were GABAA receptor-mediated currents (Fig. 5A). Because of potential network effects and to confirm that at these early ages (P8/9), RBCs had GABAergic sIPSCs, we applied SR-95531 and TPMPA without strychnine; these antagonists significantly reduced the mean frequency (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, P = 0.017) but not the median amplitude (unpaired t-test, P = 0.59) of sIPSCs (Supplementary Fig. S2, A and C). The mean frequencies of both GABAergic/glycinergic and GABAA-receptor mediated sIPSCs of RBCs did not alter from P8/9 to P90 (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, P = 0.9 for all sIPSCs and P = 1.0 for GABAA-mediated sIPSCs; Fig. 5B). The median amplitudes also remained relatively constant during development, from P8/9 to P90 (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, P = 0.05 for all sIPSCs and P = 1.0 for GABAA-mediated sIPSCs; Fig. 5C). Moreover, the median amplitudes of mixed glycinergic/GABAergic and GABAA-mediated sIPSCs were similar for RBCs (unpaired t-test, P = 1.0 at P8/9 and P = 0.36 at P90; Fig. 5C).

FIG. 5.

Glycinergic and GABAergic synaptic inputs onto RBCs and off-CBCs develop differently across time. A: example traces showing the effects of strychnine (0.5 μM) and bicuculline (50 μM) on the frequency and amplitudes of sIPSCs at various ages for RBCs and off-CBCs. B and C: developmental patterns of the mean frequency (B) and median amplitude (C) of all recorded sIPSCs (•) and strychnine-resistant, bicuculline-sensitive sIPSCs (○) in RBCs (n = 6 for P8/9, n = 7 for P10/11, n = 6 for P12/13, n = 2 for P14/15, n = 3 for P90) and off-CBCs (n = 4 at P8/9, n = 10 for P10/11, n = 8 for P12/13, n = 7 for P14/15, n = 5 for P90) from P8 to P90. Kainic acid (KA; 10 μM) was present throughout the recordings in some experiments (RBCs: P8-10 and off-CBCs: P9) to increase the baseline frequency of sIPSCs. *, significant differences between the baseline condition (all sIPSCs) and in the presence of strychnine. Paired t-test was used for differences in mean frequency, unpaired t-test for differences in median amplitude, P < 0.05. Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used determine significant differences between 2 ages; *, P < 0.05.

At P8 and P9, off-CBC sIPSCs were completely abolished by strychnine (n = 4), whereas GABA receptor agonists failed to reduce sIPSC mean frequency, suggesting that first inhibitory inputs were glycinergic (Fig. 5, A and B,, and Supplementary Fig. S2B). The mean frequency and the median amplitude of sIPSCs in off-CBCs were unchanged after the application of GABA receptor antagonists at P8/9 (unpaired t-test, P = 0.33 for the mean frequency and P = 0.79 for the median amplitude; Supplementary Fig. S2C). From P8/9 to P10/11, the mean frequency as well as the median amplitude of sIPSCs increased significantly (Fig. 5, B and C). The mean frequency and the median amplitude of GABAergic/glycinergic sIPSCs of off-CBCs appeared to decrease, although not significantly, from P10/11 to P90 (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, P = 0.2 for the mean frequency and P = 0.1 for the median amplitude; Fig. 5, B and C). From P10 to P90, both mean frequency and median amplitude were substantially reduced by strychnine indicating that at these ages, off-CBCs receive a large glycinergic input (Fig. 5, B and C). Strychnine-resistant sIPSCs had low mean frequencies and small median amplitudes. Their sensitivity to bicuculline suggested that these remaining sIPSCs were GABAA receptor-mediated (Fig. 5A). The mean frequency and median amplitude of strychnine-resistant GABAergic sIPSCs did not change during development, from P10/11 to P90 (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, P = 0.43 for the mean frequency and P = 0.79 for the median amplitude) (Fig. 5, B and C).

In all experiments shown in Fig. 5, sIPSCs were blocked by strychnine alone or strychnine in combination with bicuculline. Eggers et al. (2007) showed that application of GABAA receptor antagonists alone evoked an increase in light-evoked GABAC receptor activation at bipolar axon terminals, which in turn may reduce glycinergic transmission due to attenuated glutamate release by bipolar cells. However, we did not observe any spontaneous strychnine- and bicuculline-resistant GABAC receptor-mediated currents (Eggers and Lukasiewicz 2006b; Frech and Backus 2004). Nevertheless to exclude disinhibitory effects between amacrine cells (Roska et al. 1998; Zhang et al. 1997), we co-applied TPMPA with SR-95531 in those experiments where we isolated glycinergic sIPSCs.

Taken together, these data suggest that the subclass-specific contributions of GABAergic and glycinergic inputs to presynaptic inhibition onto bipolar cells emerge shortly after onset of amacrine cell neurotransmission onto bipolar cell axon terminals.

Emergence of a large glycinergic input onto off-CBCs may be due to maturation of contact from AII amacrine cells

The sIPSCs of off-CBCs showed a developmental increase in both amplitude and frequency by P10. To ascertain whether this increase is due to developmental changes in GABAergic and/or glycinergic transmission, we isolated glycinergic currents by applying SR-95531 and TPMPA to the recording bath and isolated GABAA-mediated currents by applying strychnine.

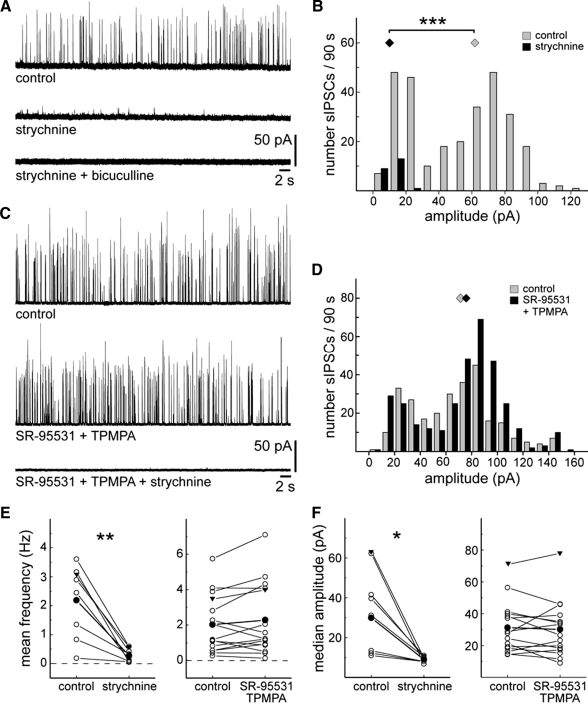

Figure 6 A shows a typical recording from an off-CBC at P11 in the presence of strychnine and then bicuculline. It is apparent that sIPSCs with large amplitudes disappeared, whereas a few sIPSCs with small amplitudes persisted in strychnine (Fig. 6, A and B). The small strychnine-resistant currents were abolished by bicuculline. A quantitative analysis of off-CBCs from P11 to P13 revealed that application of strychnine significantly reduced the mean frequency and median amplitude (Fig. 6, E and F). In contrast, the GABA receptor antagonists, SR-95531 and TPMPA, did not have any significant effect on sIPSC mean frequency and median amplitude (Fig. 6, C–F). Our observations indicate that in P11 to P13 off-CBCs, sIPSCs with large amplitudes are glycine-receptor mediated, whereas small-amplitude currents are both glycine receptor- and GABAA receptor-mediated.

FIG. 6.

Glycinergic and GABAergic sIPSCs in OFF-CBCs have different frequencies and amplitudes at P11 to P13. A: effects of strychnine (0.5 μM) and bicuculline (50 μM) on sIPSCs of an off-CBC. B: the corresponding amplitude histogram of sIPSCs recorded within a 90-s period of the cell displayed in A. ⧫, median amplitudes. Wilcoxon rank-sum test, ***, P < 0.001. C: example recording of another off-CBC in which application of SR-95531 (5 μM) and TPMPA (75 μM) was followed by strychnine (0.5 μM). D: corresponding amplitude histogram of the cell shown in C. E: summary of the effects of strychnine (left; n = 8) and SR-95531 and TPMPA (right; n = 15) on the mean frequency of sIPSCs of the recorded population. F: summary of the effects of strychnine (left) and SR-95531 and TPMPA (right) on the median amplitude. ▾, data from cells shown in A–D. Paired t-test, *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

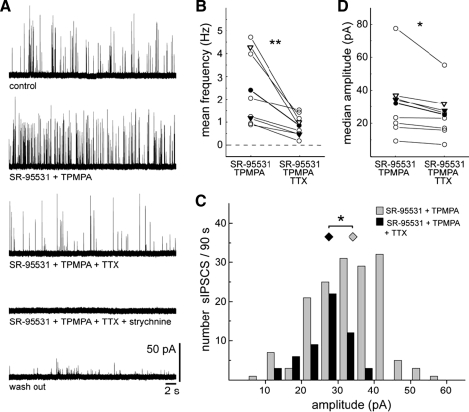

The relatively large-amplitude glycinergic sIPSCs may be due to transmission from AII amacrine cells that are known to provide the major inhibitory input onto off-CBCs. AII amacrine cells express functional TTX-sensitive sodium channels (Boos et al. 1993; Tamalu and Watanabe 2007; Veruki and Hartveit 2002). If AII amacrine cell input contributes to the large glycinergic sIPSCs in off-CBCs, then TTX should reduce the occurrence of these large sIPSCs. Indeed TTX significantly reduced the mean frequency of glycinergic sIPSCs at P12 and P13 (Fig. 7, A and B). Additionally, it is apparent from a recording from another P12 off-CBC (Fig. 7C) that in the presence of TTX, the large-amplitude glycinergic sIPSCs (>20 pA) are reduced. TTX was found, on average, to significantly diminish the median amplitude of glycinergic sIPSCs in off-CBCs (Fig. 7D).

FIG. 7.

TTX reduces the frequency of glycinergic sIPSCs of off-CBCs. A: recording showing the effect of TTX (0.5 μM) on glycinergic sIPSCs of an off-CBC. Glycinergic sIPSCs were isolated with SR-95531 (5 μM) and TPMPA (75 μM). B: summary diagram showing the effect of TTX on the mean frequency of glycinergic sIPSCs. ○ — ○, measures from a single cell. The averaged measures of the population are indicated (•, n = 8). Signed-rank test, **, P < 0.01. C: amplitude histogram of another off-CBC recorded within a 90-s period before and after application of TTX. Wilcoxon rank-sum test, *, P < 0.05. D: summary diagram showing the effect of TTX on the median amplitude. ○, measures of a single cell. The averaged measures of the population are indicated (•, n = 8). (Paired t-test, *, P < 0.05). ▿, measures from the cell shown in A. ▾, measures of the cell shown in C. All experiments were performed at P12 or P13.

However, we found that glycinergic sIPSCs in off-CBCs showed some variability in regard to frequency and amplitude (Fig. 6, E and F). A recent study showed that puffing glycine at the off-CBCs did not reveal a subtype-specific response, i.e., all four off-CBC subtypes responded with similar current amplitudes (Ivanova et al. 2006). However, it remains possible that endogenous glycinergic transmission onto the various subtypes of off cone bipolar cells differ to some degree.

Taken together, these data suggest that off-CBCs receive a large TTX-sensitive glycinergic input, some of which may arise from AII amacrine cells by P12-13, a few days prior to eye-opening.

Glutamatergic input to amacrine cells is present prior spontaneous transmission onto bipolar cells

Bipolar cells also synapse onto amacrine cells and in many cases, form reciprocal synapses with the amacrine cells (Sterling and Lampson 1986). We thus determined the temporal relationship between the formation of bipolar cell inputs onto amacrine cells and the emergence of functional input from amacrine cells onto bipolar cell axon terminals.

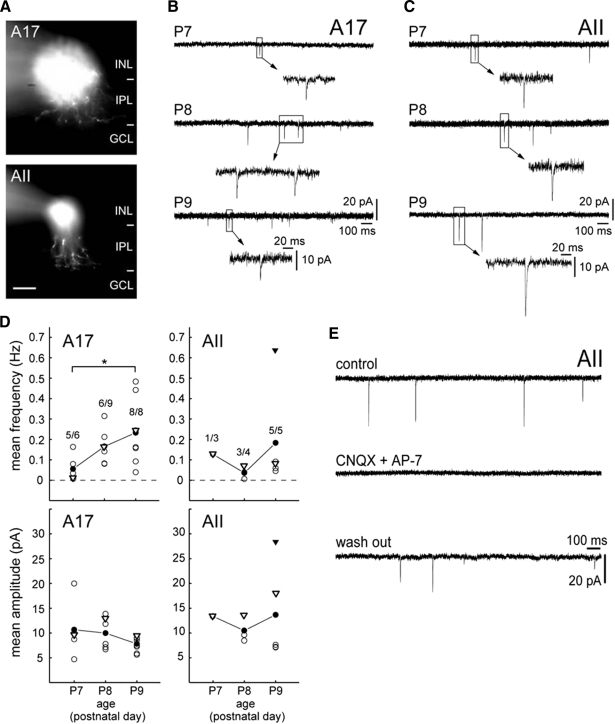

In the mature retina, A17 amacrine cells form GABAergic synapses with RBCs (Chavez et al. 2006; Raviola and Dacheux 1987), whereas AII amacrine cells receive glutamatergic input from RBCs and provide glycinergic transmission to off-CBCs (Bloomfield and Dacheux 2001). To determine when bipolar cells form functional glutamatergic synapses onto these well-characterized subtypes of amacrine cells, we recorded sEPSCs from cells with somata located in the INL from P7 to P9. Amacrine cells were voltage-clamped at −60 mV, the reversal potential for chloride-mediated currents, and filled with sulforhodamine B during the recording. Of a total of 60 recorded amacrine cells, 23 were classified as A17 amacrine cells (Eggers and Lukasiewicz 2006a; Menger and Wassle 2000; Singer and Diamond 2003) and 12 as putative AII amacrine cells (Famiglietti and Kolb 1975; Strettoi et al. 1992) (Fig. 8 A). Twenty-five amacrine cells were not further classified or analyzed.

FIG. 8.

Amacrine cells receive glutamatergic input prior to the emergence of sIPSCs on bipolar cells. A: examples of a recorded A17 amacrine cell at P7 (top) and a putative AII amacrine cell at P9 (bottom). At P7, a bistratified arbor, a characteristic for adult AII amacrine cells, is not yet apparent (see Rice and Curran 2000). GCL, ganglion cell layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer. Scale bar, 20 μm. B and C: representative recordings showing excitatory synaptic activity from P7 to P9 in A17 amacrine cells (B) and AII amacrine cells (C) voltage-clamped at −60 mV. D: mean frequency and mean amplitude of spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (sEPSCs) in A17 and AII amacrine cells from P7 to P9. ○, measures of a single cell. The averaged measures of the population are (•). ▿, measures of cells shown in B and C. ▾, data from the AII amacrine cell shown in E. Numbers above each data set at each age represent the number of amacrine cells with sEPSCs vs. the total number of recorded cells for the indicated subtype of amacrine cell. Wilcoxon rank-sum test, *, P < 0.05. E: effects of 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxalene-2,3-dione (20 μM) and d-2-amino-7-phosphonoheptanoic acid (40 μM) on sEPSCs of an AII amacrine cell at P9.

Figure 8 shows examples of recordings from A17 and AII amacrine cells and the proportion of cells within each amacrine subtype recorded at each age that had sEPSCs. The disappearance of sEPSCs following the application of the glutamatergic receptor agonists, CNQX and AP-7, confirmed that these currents were glutamatergic (n = 3; P8/9; Fig. 8E). sEPSCs were present in a fraction of A17 and AII amacrine cells at P7, but at P9, sEPSCs were found in all recorded cells. The mean frequency of sEPSCs in A17 amacrine cells increased significantly from P7 to P9 (P = 0.03), whereas the mean amplitude did not change significantly with age (P = 0.22; Fig. 8, B and D). For AII amacrine cells, neither the mean frequency (P = 0.14) nor the mean amplitude (P = 0.79) changed significantly from P8 to P9 (Fig. 8, C and D).

Thus bipolar cells form functional glutamatergic synapses with amacrine cells at least by the time, if not before, robust GABAergic/glycinergic transmission was observed in the recorded populations of rod and cone bipolar cells.

DISCUSSION

GABAergic and glycinergic synaptogenesis onto bipolar cell axon terminals

In the adult retina, GABAergic and glycinergic interneurons provide inhibition to bipolar cells, thus shaping glutamatergic transmission onto retinal ganglion cells. It is still debated to what extent horizontal cells at the outer plexiform layer and amacrine cells at the level of the IPL contribute to this inhibition. Based on focal application of receptor agonists, previous electrophysiological studies showed that functional GABA and glycine receptors are expressed on both the dendrites and axonal terminals of bipolar cells (Cui et al. 2003; Gillette and Dacheux 1995; Suzuki et al. 1990; Varela et al. 2005). Immunostaining of the mature retina for GABA and glycine receptors, however, indicated that these receptors are highly expressed on the axon terminals of bipolar cells compared with their dendrites (Fletcher et al. 1998; Greferath et al. 1993; Sassoe-Pognetto et al. 1994). Similarly, in the developing rat retina, glycine and GABA receptor immunolabeling is apparent from P9 onward in the IPL and to a lesser extent in the OPL (Sassoe-Pognetto and Wassle 1997). Here we directly measured synaptically evoked spontaneous currents in bipolar cells while focally blocking endogenous GABAergic/glycinergic transmission. This approach revealed that sIPSCs in bipolar cells have their origin largely in the IPL, most likely due to transmission from amacrine cells. Because our current recordings are in the whole cell mode, the outward currents we observed reflect the driving force for chloride that is set by the intracellular solution. It thus remains to be determined for retinal bipolar cells, whether the early GABAergic/glycinergic drive is inhibitory or excitatory.

To increase amacrine cell activity and to enhance weak inhibitory neurotransmission onto bipolar cell axon terminals during early development (P8 to P11), KA was added the extracellular solution in some experiments. Our observations are congruent with previous findings that showed that activation of kainate receptors on inhibitory interneurons resulted in an increase in frequency but not amplitude of sIPSCs recorded in pyramidal cells in rat prefrontal neocortex (Mathew et al. 2008). Spontaneous GABAC receptor-mediated events are very rarely observed in the adult mammalian retina but could be revealed by addition of KA (Eggers and Lukasiewicz 2006b; Frech and Backus 2004). We only applied KA to the developing retinae from P8 to P11 at a stage when GABAC receptor-mediated currents have been previously observed in acutely isolated RBCs by application of GABA but were a small fraction of the total GABA-evoked current (Greka et al. 2000). Thus the lack of a GABAC receptor-mediated component in our recordings is likely to be due to the low expression of GABAC receptors in the early neonates and because we did not stimulate with KA beyond P11.

Our recordings of bipolar cells at various ages revealed that functional GABAergic and glycinergic inputs onto their axonal terminals appear after the first postnatal week. At the earliest age, around P8–9, when spontaneous synaptic GABAergic/glycinergic activity in bipolar cells emerges, both on-bipolar cell (Morgan et al. 2006) and off-bipolar cell (Fig. 1B) axonal arbors are already confined to their respective on- or off-sublamina of the IPL. Amacrine cells are stratified by the first postnatal week (Hinds and Hinds 1978; Stacy and Wong 2003), and thus it is likely that the GABAergic/glycinergic inputs formed onto on- and off-bipolar cell terminals at the earliest stages are from the appropriate complement of amacrine cells. Indeed, amacrine cells that we recorded between P7 and P9 showed an adult-like morphology, and some cells could be classified as A17 or AII amacrine cells. Additionally, AII amacrine cells have been identified previously by P8 by immunolabeling for disabled-1 (Hansen et al. 2005).

Bipolar cell transmission onto retinal ganglion cells is apparent by P7 at which time ganglion cells exhibit spontaneous glutamatergic EPSCs but are not yet light-responsive (Johnson et al. 2003). Our experiments also suggest that the glutamatergic transmission onto amacrine cell neurites is already functional by P7 and therefore precedes the establishment of robust GABAergic/glycinergic input onto bipolar cell axon terminals, particularly onto CBCs (P10). Thus it appears that as a population, bipolar cells begin to form functional contact with their postsynaptic targets before their axon terminals receive detectable input from GABAergic/glycinergic amacrine cells. However, future experiments that follow the development and synaptogenesis of individual bipolar axon terminals are needed to determine whether each bipolar cell axon terminal first synapses with their targets prior to receiving functional input from GABAergic or glycinergic amacrine cells. It would also be interesting to compare such findings with the development of synapses at the calyx of Held, a well-studied glutamatergic terminal that receives presynaptic GABAergic and glycinergic input (Hoffpauir et al. 2006; Turecek and Trussell 2002), in the future.

Developmental emergence of the balance of GABAergic and glycinergic inputs onto bipolar cells is subclass-specific

Our whole cell recordings showed that sIPSCs were present in RBCs by P8, 2 day before they are detected in the vast majority of CBCs. In addition, we found that the temporal order in which glycinergic versus GABAergic inputs is established on the major bipolar cell subclasses differs: RBCs received both glycinergic and GABAergic input at P8–9, whereas in off-CBCs, small glycinergic sIPSCs were present at P8–9, subsequently followed by GABAergic sIPSCs at P10. Therefore the establishment of GABAergic inputs seems to be independently regulated for RBCs and off-CBCs. Cell type-specific temporal sequence in the formation of functional GABAergic and glycinergic synapses has previously been found onto dendrites of distinct interneuronal cell types in the spinal cord (Gonzalez-Forero and Alvarez 2005).

In contrast to RBCs, recordings from off-CBCs suggested that the glycinergic input onto this bipolar cell subclass changes in its characteristics during development. Mean frequency and median amplitude of strychnine-sensitive currents were small before P10 but increased considerably at P10. These currents are likely to reflect a later maturation of a specific type of glycinergic input onto the off-CBCs. We propose that at least some of these inputs are from AII amacrine cells for the following reasons: first, previous immunocytochemical studies have shown that off-CBC axon terminals receive a prominent glycinergic input from AII amacrine cells through large glycinergic synapses (Chun et al. 1993; Grunert and Wassle 1993; Sassoe-Pognetto et al. 1994). Second, application of TTX significantly reduced the mean frequency and median amplitude of glycinergic postsynaptic currents. AII amacrine cells are described to express functional TTX-sensitive sodium channels (Boos et al. 1993; Tamalu and Watanabe 2007; Veruki and Hartveit 2002). Taken together with previous findings showing that electrical synapses between AII amacrine cells and on-CBCs become functional by P10 (Hansen et al. 2005; Pow and Hendrickson 2000), our current data suggest that the circuitry linking the rod bipolar and cone bipolar pathways is functional prior to the emergence of robust light responses.

A developmental shift from GABAergic to glycinergic transmission within the first two postnatal weeks has been described for the auditory brain stem and the spinal cord (Awatramani et al. 2005; Gao and Ziskind-Conhaim 1995; Gao et al. 1998; Kotak et al. 1998; Turecek and Trussell 2002). Chloride-mediated currents were initially largely GABA receptor-mediated but were later mostly mediated by glycine receptors. In the retinal bipolar cells, we did not find such a developmental shift in the balance of GABAergic and glycinergic drive. Instead our recordings showed that mean frequency and median amplitude of GABAergic and glycinergic postsynaptic currents in RBCs and off-CBCs remain relatively constant once they were established. Thus the relative contribution of glycinergic and GABAergic transmission onto bipolar cell axons is established shortly after the onset of synapse formation. Maturation of GABAergic/glycinergic synapses at bipolar cell axons in the retina and in the auditory brain or the spinal cord stem may differ because inhibitory neurotransmitters in developing auditory nuclei and spinal cord are co-released from mixed GABAergic-glycinergic presynaptic terminals (Jonas et al. 1998; Nabekura et al. 2004). In the mammalian retina, glycine and GABA have distinct roles in the inner plexiform layer. Gycinergic transmission mediates vertical inhibition, and GABAergic signals mediate lateral inhibition (Wassle 2004). Therefore GABA and glycine are released by different amacrine cells during development (Crook and Pow 1997). The mechanism by which distinct sets of GABAergic and glycinergic amacrine cells contact each bipolar axonal terminal to provide the appropriate contribution of their respective drive remains to be explored. It will be interesting in the future to ascertain whether presynaptic inhibition onto bipolar cell axons requires neurite outgrowth from amacrine cells that have already formed circuits at that stage or whether such inhibition is provided by new populations of amacrine cells generated just prior to bipolar cell differentiation.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (R.O.L. Wong), Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (T. Schubert and D. Kerschensteiner). T. Migeld is supported by grants of the Alexander-von-Humboldt foundation and the Center of Integrated Protein Science Munich.

Acknowledgments

We thank F. Soto for thoughtful reading of this manuscript.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains supplemental data.

REFERENCES

- Ango et al. 2004.Ango F, di Cristo G, Higashiyama H, Bennett V, Wu P, Huang ZJ. Ankyrin-based subcellular gradient of neurofascin, an immunoglobulin family protein, directs GABAergic innervation at purkinje axon initial segment. Cell 119: 257–272, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awatramani et al. 2005.Awatramani GB, Turecek R, Trussell LO. Staggered development of GABAergic and glycinergic transmission in the MNTB. J Neurophysiol 93: 819–828, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari et al. 2007.Ben-Ari Y, Gaiarsa JL, Tyzio R, Khazipov R. GABA: a pioneer transmitter that excites immature neurons and generates primitive oscillations. Physiol Rev 87: 1215–1284, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield and Dacheux 2001.Bloomfield SA Dacheux RF. Rod vision: pathways and processing in the mammalian retina. Prog Retin Eye Res 20: 351–384, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boos et al. 1993.Boos R, Schneider H, Wassle H. Voltage- and transmitter-gated currents of all-amacrine cells in a slice preparation of the rat retina. J Neurosci 13: 2874–2888, 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez et al. 2006.Chavez AE, Singer JH, Diamond JS. Fast neurotransmitter release triggered by Ca influx through AMPA-type glutamate receptors. Nature 443: 705–708, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun et al. 1993.Chun MH, Han SH, Chung JW, Wassle H. Electron microscopic analysis of the rod pathway of the rat retina. J Comp Neurol 332: 421–432, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crook and Pow 1997.Crook DK Pow DV. Analysis of the distribution of glycine and GABA in amacrine cells of the developing rabbit retina: a comparison with the ontogeny of a functional GABA transport system in retinal neurons. Vis Neurosci 14: 751–763, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui et al. 2003.Cui J, Ma YP, Lipton SA, Pan ZH. Glycine receptors and glycinergic synaptic input at the axon terminals of mammalian retinal rod bipolar cells. J Physiol 553: 895–909, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong and Werblin 1998.Dong CJ Werblin FS. Temporal contrast enhancement via GABAC feedback at bipolar terminals in the tiger salamander retina. J Neurophysiol 79: 2171–2180, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggers and Lukasiewicz 2006a.Eggers ED Lukasiewicz PD. GABA(A), GABA(C) and glycine receptor-mediated inhibition differentially affects light-evoked signalling from mouse retinal rod bipolar cells. J Physiol 572: 215–225, 2006a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggers and Lukasiewicz 2006b.Eggers ED Lukasiewicz PD. Receptor and transmitter release properties set the time course of retinal inhibition. J Neurosci 26: 9413–9425, 2006b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggers et al. 2007.Eggers ED, McCall MA, Lukasiewicz PD. Presynaptic inhibition differentially shapes transmission in distinct circuits in the mouse retina. J Physiol 582: 569–582, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelman and MacDermott 2004.Engelman HS MacDermott AB. Presynaptic ionotropic receptors and control of transmitter release. Nat Rev Neurosci 5: 135–145, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Euler and Wassle 1998.Euler T Wassle H. Different contributions of GABAA and GABAC receptors to rod and cone bipolar cells in a rat retinal slice preparation. J Neurophysiol 79: 1384–1395, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Famiglietti and Kolb 1975.Famiglietti EV Kolb H. A bistratified amacrine cell and synaptic cirucitry in the inner plexiform layer of the retina. Brain Res 84: 293–300, 1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher et al. 1998.Fletcher EL, Koulen P, Wassle H. GABAA and GABAC receptors on mammalian rod bipolar cells. J Comp Neurol 396: 351–365, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frech and Backus 2004.Frech MJ Backus KH. Characterization of inhibitory postsynaptic currents in rod bipolar cells of the mouse retina. Vis Neurosci 21: 645–652, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao et al. 1998.Gao BX, Cheng G, Ziskind-Conhaim L. Development of spontaneous synaptic transmission in the rat spinal cord. J Neurophysiol 79: 2277–2287, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao and Ziskind-Conhaim 1995.Gao BX Ziskind-Conhaim L. Development of glycine- and GABA-gated currents in rat spinal motoneurons. J Neurophysiol 74: 113–121, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh et al. 2004.Ghosh KK, Bujan S, Haverkamp S, Feigenspan A, Wassle H. Types of bipolar cells in the mouse retina. J Comp Neurol 469: 70–82, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillette and Dacheux 1995.Gillette MA Dacheux RF. GABA- and glycine-activated currents in the rod bipolar cell of the rabbit retina. J Neurophysiol 74: 856–875, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Forero and Alvarez 2005.Gonzalez-Forero D Alvarez FJ. Differential postnatal maturation of GABAA, glycine receptor, and mixed synaptic currents in Renshaw cells and ventral spinal interneurons. J Neurosci 25: 2010–2023, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greferath et al. 1993.Greferath U, Muller F, Wassle H, Shivers B, Seeburg P. Localization of GABAA receptors in the rat retina. Vis Neurosci 10: 551–561, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greka et al. 2000.Greka A, Lipton SA, Zhang D. Expression of GABA(C) receptor rho1 and rho2 subunits during development of the mouse retina. Eur J Neurosci 12: 3575–3582, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunert and Wassle 1993.Grunert U Wassle H. Immunocytochemical localization of glycine receptors in the mammalian retina. J Comp Neurol 335: 523–537, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen et al. 2005.Hansen KA, Torborg CL, Elstrott J, Feller MB. Expression and function of the neuronal gap junction protein connexin 36 in developing mammalian retina. J Comp Neurol 493: 309–320, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartveit 1999.Hartveit E Reciprocal synaptic interactions between rod bipolar cells and amacrine cells in the rat retina. J Neurophysiol 81: 2923–2936, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haverkamp et al. 2003.Haverkamp S, Ghosh KK, Hirano AA, Wassle H. Immunocytochemical description of five bipolar cell types of the mouse retina. J Comp Neurol 455: 463–476, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinds and Hinds 1978.Hinds JW Hinds PL. Early development of amacrine cells in the mouse retina: an electron microscopic, serial section analysis. J Comp Neurol 179: 277–300, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffpauir et al. 2006.Hoffpauir BK, Grimes JL, Mathers PH, Spirou GA. Synaptogenesis of the calyx of Held: rapid onset of function and one-to-one morphological innervation. J Neurosci 26: 5511–5523, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang et al. 2007.Huang ZJ, Di Cristo G, Ango F. Development of GABA innervation in the cerebral and cerebellar cortices. Nat Rev Neurosci 8: 673–686, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova et al. 2006.Ivanova E, Muller U, Wassle H. Characterization of the glycinergic input to bipolar cells of the mouse retina. Eur J Neurosci 23: 350–364, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang et al. 2006.Jang IS, Nakamura M, Ito Y, Akaike N. Presynaptic GABAA receptors facilitate spontaneous glutamate release from presynaptic terminals on mechanically dissociated rat CA3 pyramidal neurons. Neuroscience 138: 25–35, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson et al. 2003.Johnson J, Tian N, Caywood MS, Reimer RJ, Edwards RH, Copenhagen DR. Vesicular neurotransmitter transporter expression in developing postnatal rodent retina: GABA and glycine precede glutamate. J Neurosci 23: 518–529, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas et al. 1998.Jonas P, Bischofberger J, Sandkuhler J. Corelease of two fast neurotransmitters at a central synapse. Science 281: 419–424, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotak et al. 1998.Kotak VC, Korada S, Schwartz IR, Sanes DH. A developmental shift from GABAergic to glycinergic transmission in the central auditory system. J Neurosci 18: 4646–4655, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukasiewicz and Roeder 1995.Lukasiewicz PD Roeder RC. Evidence for glycine modulation of excitatory synaptic inputs to retinal ganglion cells. J Neurosci 15: 4592–4601, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukasiewicz and Werblin 1994.Lukasiewicz PD Werblin FS. A novel GABA receptor modulates synaptic transmission from bipolar to ganglion and amacrine cells in the tiger salamander retina. J Neurosci 14: 1213–1223, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew et al. 2008.Mathew SS, Pozzo-Miller L, Hablitz JJ. Kainate modulates presynaptic GABA release from two vesicle pools. J Neurosci 28: 725–731, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menger and Wassle 2000.Menger N Wassle H. Morphological and physiological properties of the A17 amacrine cell of the rat retina. Vis Neurosci 17: 769–780, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misgeld et al. 2007.Misgeld T, Kerschensteiner M, Bareyre FM, Burgess RW, Lichtman JW. Imaging axonal transport of mitochondria in vivo. Nat Methods 4: 559–561, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan et al. 2006.Morgan JL, Dhingra A, Vardi N, Wong RO. Axons and dendrites originate from neuroepithelial-like processes of retinal bipolar cells. Nat Neurosci 9: 85–92, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss and Smart 2001.Moss SJ Smart TG. Constructing inhibitory synapses. Nat Rev Neurosci 2: 240–250, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabekura et al. 2004.Nabekura J, Katsurabayashi S, Kakazu Y, Shibata S, Matsubara A, Jinno S, Mizoguchi Y, Sasaki A, Ishibashi H. Developmental switch from GABA to glycine release in single central synaptic terminals. Nat Neurosci 7: 17–23, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan and Lipton 1995.Pan ZH Lipton SA. Multiple GABA receptor subtypes mediate inhibition of calcium influx at rat retinal bipolar cell terminals. J Neurosci 15: 2668–2679, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pow and Hendrickson 2000.Pow DV Hendrickson AE. Expression of glycine and the glycine transporter glyt-1 in the developing rat retina. Vis Neurosci 17: 1–9, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raviola and Dacheux 1987.Raviola E Dacheux RF. Excitatory dyad synapse in rabbit retina. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 84: 7324–7328, 1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice and Curran 2000.Rice DS Curran T. Disabled-1 is expressed in type AII amacrine cells in the mouse retina. J Comp Neurol 424: 327–338, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roska et al. 1998.Roska B, Nemeth E, Werblin FS. Response to change is facilitated by a three-neuron disinhibitory pathway in the tiger salamander retina. J Neurosci 18: 3451–3459, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudomin and Schmidt 1999.Rudomin P Schmidt RF. Presynaptic inhibition in the vertebrate spinal cord revisited. Exp Brain Res 129: 1–37, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz et al. 2003.Ruiz A, Fabian-Fine R, Scott R, Walker MC, Rusakov DA, Kullmann DM. GABAA receptors at hippocampal mossy fibers. Neuron 39: 961–973, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassoe-Pognetto and Wassle 1997.Sassoe-Pognetto M Wassle H. Synaptogenesis in the rat retina: subcellular localization of glycine receptors, GABA(A) receptors, and the anchoring protein gephyrin. J Comp Neurol 381: 158–174, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassoe-Pognetto et al. 1994.Sassoe-Pognetto M, Wassle H, Grunert U. Glycinergic synapses in the rod pathway of the rat retina: cone bipolar cells express the alpha 1 subunit of the glycine receptor. J Neurosci 14: 5131–5146, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer and Diamond 2003.Singer JH Diamond JS. Sustained Ca2+ entry elicits transient postsynaptic currents at a retinal ribbon synapse. J Neurosci 23: 10923–10933, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacy and Wong 2003.Stacy RC Wong RO. Developmental relationship between cholinergic amacrine cell processes and ganglion cell dendrites of the mouse retina. J Comp Neurol 456: 154–166, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stell et al. 2007.Stell BM, Rostaing P, Triller A, Marty A. Activation of presynaptic GABA(A) receptors induces glutamate release from parallel fiber synapses. J Neurosci 27: 9022–9031, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling and Lampson 1986.Sterling P Lampson LA. Molecular specificity of defined types of amacrine synapse in cat retina. J Neurosci 6: 1314–1324, 1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strettoi et al. 1992.Strettoi E, Raviola E, Dacheux RF. Synaptic connections of the narrow-field, bistratified rod amacrine cell (AII) in the rabbit retina. J Comp Neurol 325: 152–168, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki et al. 1990.Suzuki S, Tachibana M, Kaneko A. Effects of glycine and GABA on isolated bipolar cells of the mouse retina. J Physiol 421: 645–662, 1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabadics et al. 2006.Szabadics J, Varga C, Molnar G, Olah S, Barzo P, Tamas G. Excitatory effect of GABAergic axo-axonic cells in cortical microcircuits. Science 311: 233–235, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamalu and Watanabe 2007.Tamalu F Watanabe S. Glutamatergic input is coded by spike frequency at the soma and proximal dendrite of AII amacrine cells in the mouse retina. Eur J Neurosci 25: 3243–3252, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turecek and Trussell 2001.Turecek R Trussell LO. Presynaptic glycine receptors enhance transmitter release at a mammalian central synapse. Nature 411: 587–590, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turecek and Trussell 2002.Turecek R Trussell LO. Reciprocal developmental regulation of presynaptic ionotropic receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 13884–13889, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaney et al. 1998.Vaney DI, Nelson JC, Pow DV. Neurotransmitter coupling through gap junctions in the retina. J Neurosci 18: 10594–10602, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varela et al. 2005.Varela C, Blanco R, De la Villa P. Depolarizing effect of GABA in rod bipolar cells of the mouse retina. Vision Res 45: 2659–2667, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veruki and Hartveit 2002.Veruki ML Hartveit E. AII (Rod) amacrine cells form a network of electrically coupled interneurons in the mammalian retina. Neuron 33: 935–946, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassle 2004.Wassle H Parallel processing in the mammalian retina. Nat Rev Neurosci 5: 747–757, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werblin 1978.Werblin FS Transmission along and between rods in the tiger salamander retina. J Physiol 280: 449–470, 1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang et al. 1997.Zhang J, Jung CS, Slaughter MM. Serial inhibitory synapses in retina. Vis Neurosci 14: 553–563, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]