Abstract

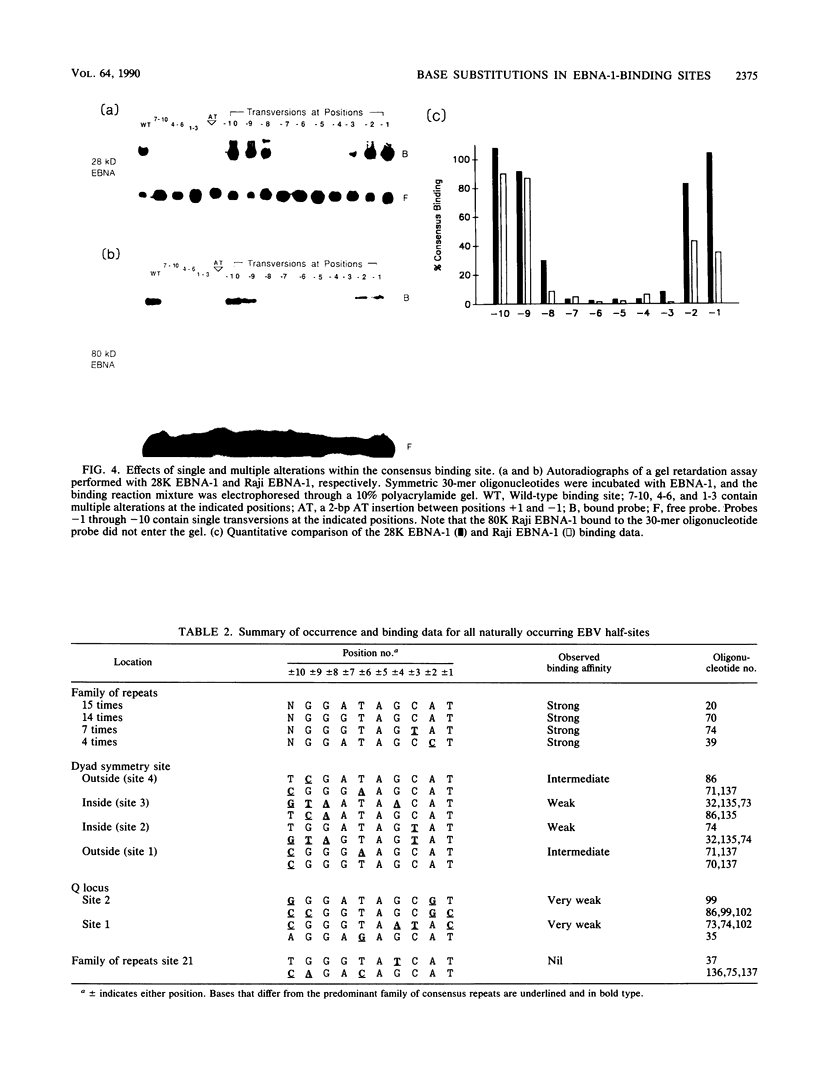

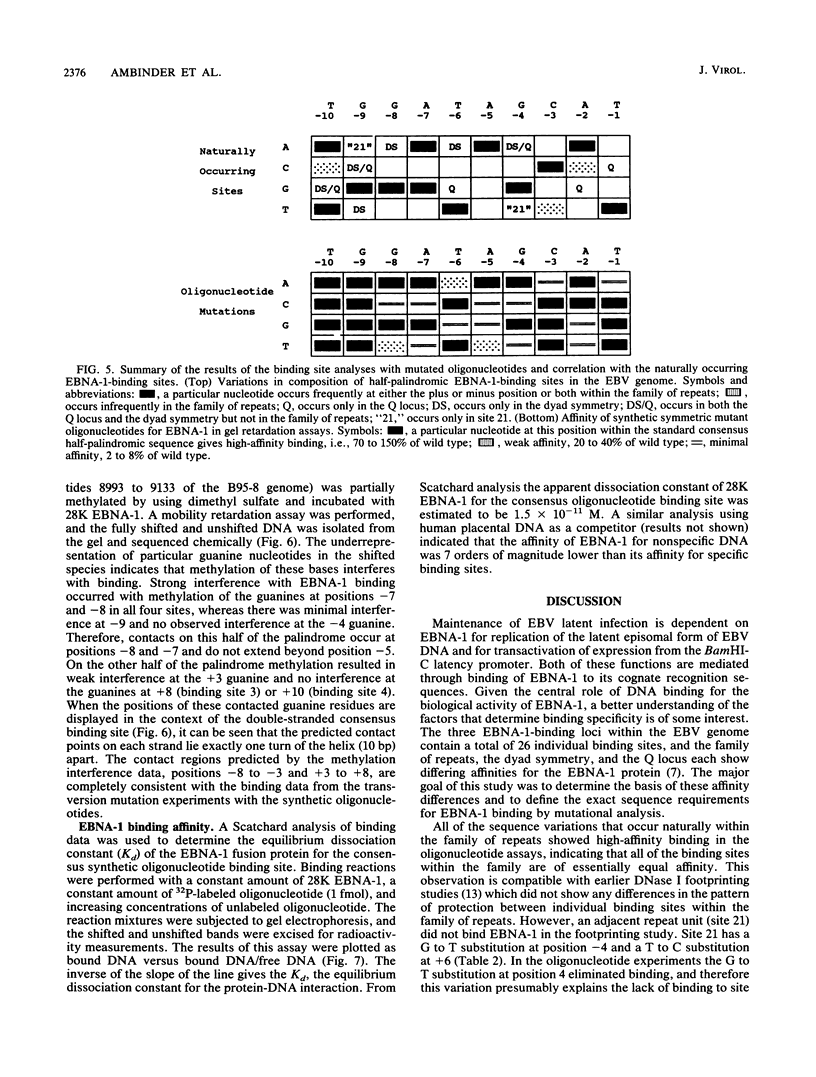

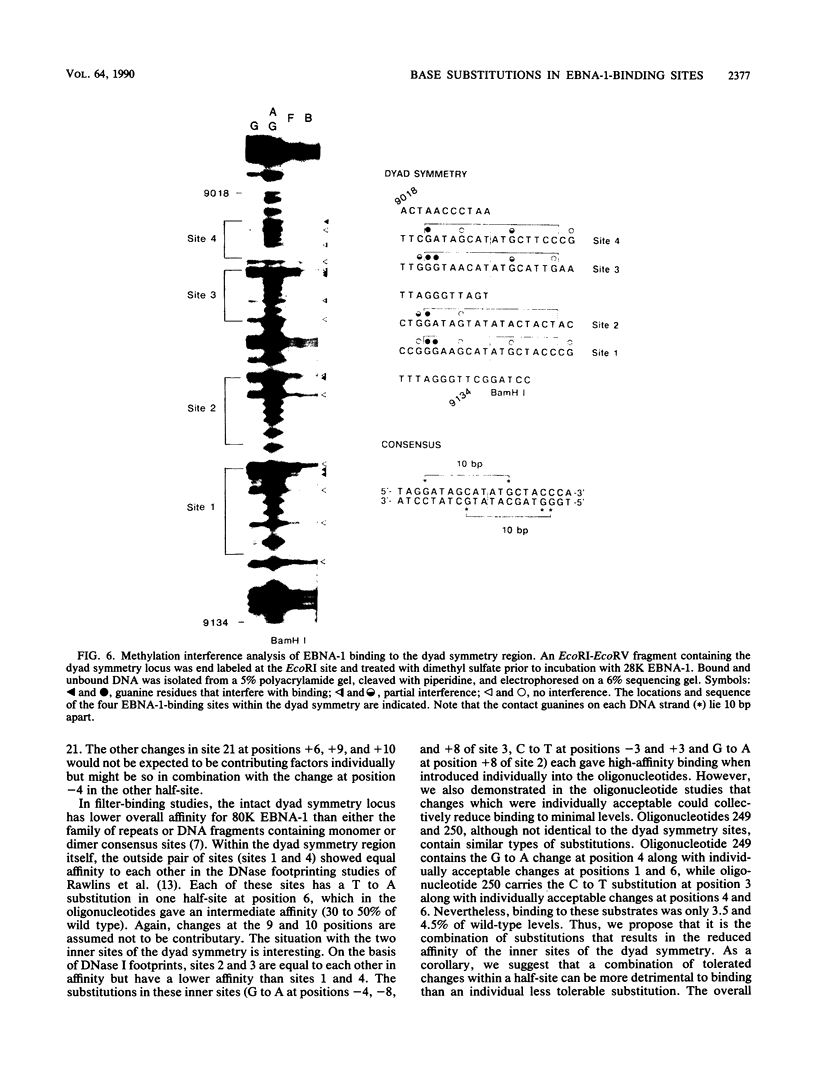

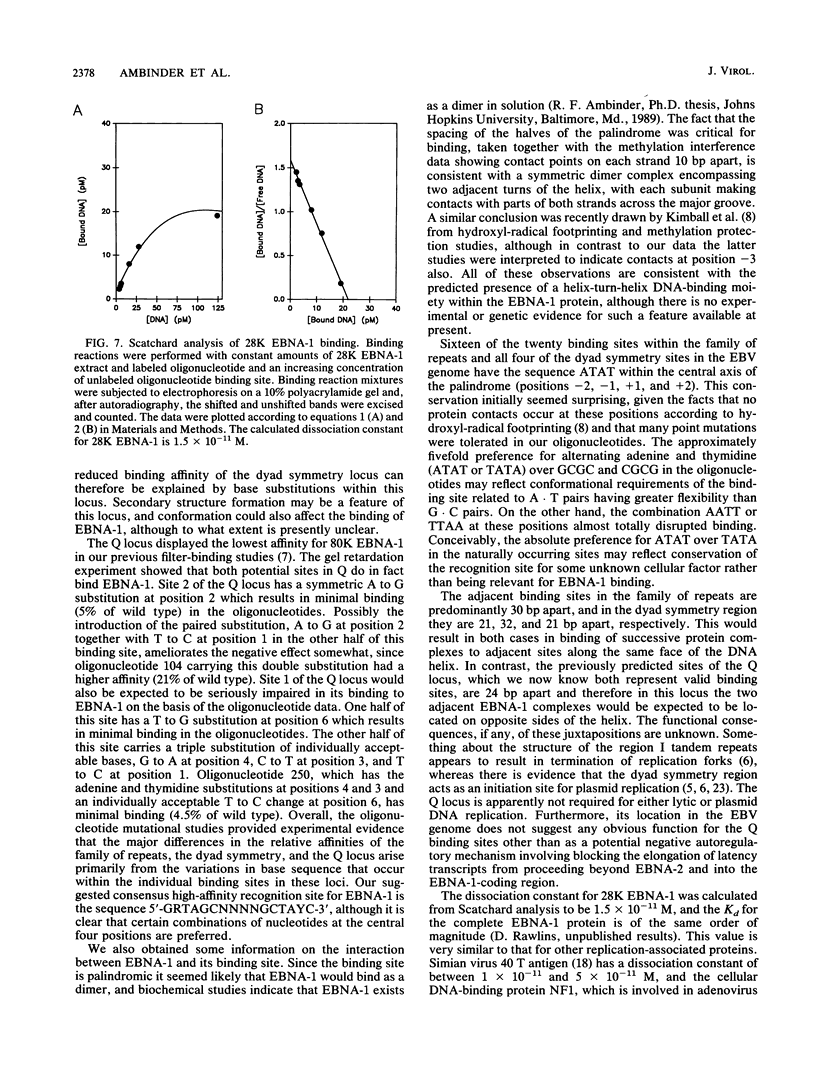

Interaction between the trans-acting DNA-binding protein EBNA-1 and cis-acting sequences in the ori-P region of Epstein-Barr virus DNA is required for maintenance of the viral plasmid state in latently infected B cells and is involved in the regulation of transcription during latency. In the Epstein-Barr virus genome, a total of 26 EBNA-1-binding sites occur within three clustered loci referred to as the family of repeats and dyad symmetry locus of ori-P and the separate BamHI-Q locus. Incubation of a bacterially expressed carboxy-terminal domain of EBNA-1 (28,000-molecular-weight EBNA-1 [28K EBNA-1]) with synthetic monomer and dimer consensus binding sites gave characteristic DNA-protein complexes in a mobility retardation assay. A similar approach with the naturally occurring Q locus confirmed that it contains two distinct but low-affinity binding sites. We then examined the precise sequence requirements for EBNA-1 binding, using a set of 30-base-pair oligonucleotides designed to contain symmetric point mutations within both halves of the palindromic target site. Analysis of all possible single substitutions between positions 1 and 10 in the consensus half-palindrome sequence revealed that positions 9 and 10 did not contribute to EBNA-1 binding and that considerable flexibility could be tolerated at positions 1 and 2. Positions 3 through 8 of the recognition site had the most stringent requirements, with transversions at these positions either reducing or eliminating binding. The relative spacing of the halves of the palindrome was also critical, since the addition or removal of 2 base pairs at the center of the sequence abolished binding. Similar results were obtained when a partially purified preparation of intact Raji EBNA-1 was substituted for the 28K EBNA-1, and the results were further supported by methylation interference studies which indicated contact points between EBNA-1 and the guanine residues at positions -8, -7, and +3 of the binding site. The three naturally occurring EBNA-1-binding loci have previously been shown to differ in their relative affinities for EBNA-1. The present study indicates that the sequence variations occurring within the family of repeats would not affect binding affinity, whereas certain base substitutions within the Q and dyad symmetry sites would be predicted to contribute to the observed lower affinities of these sites. An apparent Kd of 1.5 x 10(-11) M for binding of 28K EBNA-1 to a consensus recognition site was calculated from Scatchard analysis.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Baker R. E., Gabrielsen O., Hall B. D. Effects of tRNATyr point mutations on the binding of yeast RNA polymerase III transcription factor C. J Biol Chem. 1986 Apr 25;261(12):5275–5282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodescot M., Brison O., Perricaudet M. An Epstein-Barr virus transcription unit is at least 84 kilobases long. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986 Mar 25;14(6):2611–2620. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.6.2611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodescot M., Perricaudet M., Farrell P. J. A promoter for the highly spliced EBNA family of RNAs of Epstein-Barr virus. J Virol. 1987 Nov;61(11):3424–3430. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.11.3424-3430.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulanger P. A., Yoshinaga S. K., Berk A. J. DNA-binding properties and characterization of human transcription factor TFIIIC2. J Biol Chem. 1987 Nov 5;262(31):15098–15105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chittenden T., Lupton S., Levine A. J. Functional limits of oriP, the Epstein-Barr virus plasmid origin of replication. J Virol. 1989 Jul;63(7):3016–3025. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.7.3016-3025.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gahn T. A., Schildkraut C. L. The Epstein-Barr virus origin of plasmid replication, oriP, contains both the initiation and termination sites of DNA replication. Cell. 1989 Aug 11;58(3):527–535. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90433-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones C. H., Hayward S. D., Rawlins D. R. Interaction of the lymphocyte-derived Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen EBNA-1 with its DNA-binding sites. J Virol. 1989 Jan;63(1):101–110. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.1.101-110.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimball A. S., Milman G., Tullius T. D. High-resolution footprints of the DNA-binding domain of Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 1. Mol Cell Biol. 1989 Jun;9(6):2738–2742. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.6.2738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl T., Adams A., Bjursell G., Bornkamm G. W., Kaschka-Dierich C., Jehn U. Covalently closed circular duplex DNA of Epstein-Barr virus in a human lymphoid cell line. J Mol Biol. 1976 Apr 15;102(3):511–530. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(76)90331-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milman G., Hwang E. S. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen forms a complex that binds with high concentration dependence to a single DNA-binding site. J Virol. 1987 Feb;61(2):465–471. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.2.465-471.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milman G., Scott A. L., Cho M. S., Hartman S. C., Ades D. K., Hayward G. S., Ki P. F., August J. T., Hayward S. D. Carboxyl-terminal domain of the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen is highly immunogenic in man. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985 Sep;82(18):6300–6304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.18.6300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonoyama M., Pagano J. S. Separation of Epstein-Barr virus DNA from large chromosomal DNA in non-virus-producing cells. Nat New Biol. 1972 Aug 9;238(84):169–171. doi: 10.1038/newbio238169a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlins D. R., Milman G., Hayward S. D., Hayward G. S. Sequence-specific DNA binding of the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen (EBNA-1) to clustered sites in the plasmid maintenance region. Cell. 1985 Oct;42(3):859–868. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90282-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisman D., Sugden B. trans activation of an Epstein-Barr viral transcriptional enhancer by the Epstein-Barr viral nuclear antigen 1. Mol Cell Biol. 1986 Nov;6(11):3838–3846. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.11.3838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisman D., Yates J., Sugden B. A putative origin of replication of plasmids derived from Epstein-Barr virus is composed of two cis-acting components. Mol Cell Biol. 1985 Aug;5(8):1822–1832. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.8.1822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld P. J., Kelly T. J. Purification of nuclear factor I by DNA recognition site affinity chromatography. J Biol Chem. 1986 Jan 25;261(3):1398–1408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sample J., Hummel M., Braun D., Birkenbach M., Kieff E. Nucleotide sequences of mRNAs encoding Epstein-Barr virus nuclear proteins: a probable transcriptional initiation site. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986 Jul;83(14):5096–5100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.14.5096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schirmbeck R., Deppert W. Nuclear subcompartmentalization of simian virus 40 large T antigen: evidence for in vivo regulation of biochemical activities. J Virol. 1989 May;63(5):2308–2316. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.5.2308-2316.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh H., Sen R., Baltimore D., Sharp P. A. A nuclear factor that binds to a conserved sequence motif in transcriptional control elements of immunoglobulin genes. Nature. 1986 Jan 9;319(6049):154–158. doi: 10.1038/319154a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speck S. H., Strominger J. L. Analysis of the transcript encoding the latent Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen I: a potentially polycistronic message generated by long-range splicing of several exons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985 Dec;82(24):8305–8309. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.24.8305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm R., Baumruker T., Franza B. R., Jr, Herr W. A 100-kD HeLa cell octamer binding protein (OBP100) interacts differently with two separate octamer-related sequences within the SV40 enhancer. Genes Dev. 1987 Dec;1(10):1147–1160. doi: 10.1101/gad.1.10.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugden B., Warren N. A promoter of Epstein-Barr virus that can function during latent infection can be transactivated by EBNA-1, a viral protein required for viral DNA replication during latent infection. J Virol. 1989 Jun;63(6):2644–2649. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.6.2644-2649.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wysokenski D. A., Yates J. L. Multiple EBNA1-binding sites are required to form an EBNA1-dependent enhancer and to activate a minimal replicative origin within oriP of Epstein-Barr virus. J Virol. 1989 Jun;63(6):2657–2666. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.6.2657-2666.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates J. L., Warren N., Sugden B. Stable replication of plasmids derived from Epstein-Barr virus in various mammalian cells. 1985 Feb 28-Mar 6Nature. 313(6005):812–815. doi: 10.1038/313812a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates J., Warren N., Reisman D., Sugden B. A cis-acting element from the Epstein-Barr viral genome that permits stable replication of recombinant plasmids in latently infected cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984 Jun;81(12):3806–3810. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.12.3806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]