Abstract

We previously reported an enhanced tonic dilator impact of ATP-sensitive K+ channels in afferent arterioles of rats with streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetes. The present study explored the hypothesis that other types of K+ channel also contribute to afferent arteriolar dilation in STZ rats. The in vitro blood-perfused juxtamedullary nephron technique was utilized to quantify afferent arteriolar lumen diameter responses to K+ channel blockers: 0.1–3.0 mM 4-aminopyridine (4-AP; KV channels), 10–100 μM barium (KIR channels), 1–100 nM tertiapin-Q (TPQ; Kir1.1 and Kir3.x subfamilies of KIR channels), 100 nM apamin (SKCa channels), and 1 mM tetraethylammonium (TEA; BKCa channels). In kidneys from normal rats, 4-AP, TEA, and Ba2+ reduced afferent diameter by 23 ± 3, 8 ± 4, and 18 ± 2%, respectively, at the highest concentrations employed. Neither TPQ nor apamin significantly altered afferent diameter. In arterioles from STZ rats, a constrictor response to TPQ (22 ± 4% decrease in diameter) emerged, and the response to Ba2+ was exaggerated (28 ± 5% decrease in diameter). Responses to the other K+ channel blockers were similar to those observed in normal rats. Moreover, exposure to either TPQ or Ba2+ reversed the afferent arteriolar dilation characteristic of STZ rats. Acute surgical papillectomy did not alter the response to TPQ in arterioles from normal or STZ rats. We conclude that 1) KV, KIR, and BKCa channels tonically influence normal afferent arteriolar tone, 2) KIR channels (including Kir1.1 and/or Kir3.x) contribute to the afferent arteriolar dilation during diabetes, and 3) the dilator impact of Kir1.1/Kir3.x channels during diabetes is independent of solute delivery to the macula densa.

Keywords: tertiapin-Q, barium, TEA, apamin, 4-aminopyridine

diabetes is the foremost cause of end-stage renal disease in the Western world (17). During the early stage of type 1 diabetes (T1D), there is an increase in glomerular filtration rate (diabetic hyperfiltration) that may contribute to the eventual development of diabetic nephropathy (21). Although renal afferent arteriolar dilation is the major vascular alteration leading to diabetic hyperfiltration (22), the precise mechanism underlying the afferent arteriolar dilation during T1D has not been established.

Preglomerular microvascular resistance is tightly linked to vascular smooth muscle membrane potential and its impact on the open probability of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs). Our laboratory previously showed a defect in the functional responsiveness of VGCCs in afferent arterioles from rats with streptozotocin (STZ)-induced T1D (7). This phenomenon is evident as reduced VGCC-dependent [Ca2+]i and lumen diameter responses to depolarization, suggesting that decreased VGCC responsiveness to membrane depolarization contributes to decreased afferent arteriolar resistance during the hyperfiltration stage of T1D. An increase in the K+ conductance of the afferent arteriolar vascular smooth muscle cell membrane could exacerbate this situation, as the resulting hyperpolarization would also reduce the open probability of VGCCs, thereby decreasing [Ca2+]i and promoting vasodilation. Electrophysiological and pharmacological approaches have revealed several classes of K+ channels in preglomerular microvascular smooth muscle and intact afferent arterioles— ATP-sensitive K+ channels (KATP channels), large- and small/intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels (BKCa channels and SKCa channels, respectively), inward-rectifier K+ channels (KIR channels), and voltage-gated K+ channels (KV channels, such as the delayed rectifier) (12, 15, 16, 18, 24, 27, 40, 58). However, there is not a clear understanding as to which K+ channels contribute substantially to afferent arteriolar tone under normal conditions or during diabetes.

We previously reported that the KATP channels contribute little to afferent arteriolar tone under normal conditions but exert a significant tonic dilator influence on the afferent arteriole during the hyperfiltration stage of STZ-induced T1D (24). KATP channels in vascular smooth muscle are comprised of pore-forming Kir6.1 subunits (members of the KIR channel family) and regulatory sulfonylurea receptor (SUR2B) subunits (56). Thus, it is conceivable that additional members of KIR channel family may also be involved in the afferent arteriolar dilation seen in T1D. The modest tonic dilator impact of BKCa channels on afferent arteriolar tone in the normal kidney (15) might be enhanced in T1D, perhaps via an H2O2-dependent mechanism (20) during this state of oxidative stress. To our knowledge, no information is available regarding the influence of SKCa or KV channels on afferent arteriolar tone in normal or disease states, although KV channels may modestly potentiate myogenic responses of this vessel (33). Thus, the goals of the present study were to survey the tonic impact of the various afferent arteriolar K+ channels on lumen diameter of this vessel in normal rats and to test the hypothesis that increased activation of one or more of these channels is involved in the afferent arteriolar dilation evident in STZ-induced diabetes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Induction of diabetes mellitus.

All studies utilized male Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan, barrier 218A; Prattville, AL), which were treated according to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals using procedures approved by the University of Nebraska Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Rats were housed in pairs and provided ad libitum access to food and water. Rats were anesthetized with 50 mg/kg ip methohexital sodium to facilitate injection of STZ (65 mg/kg iv). The rats were allowed to recover from anesthesia and were housed overnight. The following day, blood glucose levels were measured (Accu-Check III model 766; Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN) and the rats were anesthetized again to allow subcutaneous insertion via a 16-gauge needle of a 2.3 × 2.0-mm sustained-release insulin implant (Linplant; Linshin Canada, Scarborough, Ontario). Rats received ad libitum food and water for the ensuing 3–4 wk, during which blood glucose measurements were made twice weekly. Acute, terminal experiments were performed 22 ± 1 days after STZ injection (range 14–30 days). Approximately age-matched, normal male Sprague-Dawley rats (n = 24) served as nondiabetic controls.

Rat in vitro blood-perfused juxtamedullary nephron technique.

Acute experiments were performed using the rat in vitro blood-perfused juxtamedullary nephron technique (8). After anesthetization with pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg ip), a cannula was placed in the carotid artery. A perfusion cannula introduced via the superior mesenteric artery into the right renal artery allowed renal perfusion with Tyrode's solution containing 52 g/l bovine serum albumin and a mixture of l-amino acids (43). The renal vein was incised to drain the perfusate and the animal was exsanguinated via the carotid cannula into a heparinized syringe; however, renal perfusion was maintained throughout the ensuing dissection procedure. The kidney was removed and cut longitudinally to expose the pelvic cavity, leaving the papilla intact within the perfused dorsal two-thirds of the organ. Small incisions were made in the lateral fornices, allowing the papilla to be reflected back and retained in that position by insect pins. The pelvic mucosa, adipose and connective tissues that normally cover the inside cortical surface, were removed and the veins were cut open, thus exposing the tubules and microvasculature of juxtamedullary nephrons. The portions of the vasculature that give rise to arterioles associated with these juxtamedullary nephrons were isolated with tight ligatures. Blood collected from the rat was prepared for perfusion (6, 8) and processed to remove leukocytes and platelets. The reconstituted blood was filtered through a 5-μm nylon mesh, and its pH was measured (ABL5 Blood Gas Analyzer; Radiometer America, Westlake, OH) and adjusted to 7.40 to 7.42 by addition of NaHCO3, as necessary. Thereafter, the blood was stirred continuously in a closed reservoir that was maintained under pressure from a gas tank (95% O2-5% CO2). This arrangement provided both tissue oxygenation and the driving force for perfusion of the kidney. The Tyrode's perfusate was then replaced by the reconstituted blood perfusate. Perfusion pressure at the cannula tip in the renal artery was measured using a P23XL transducer (Gould, Oxnard, CA) connected to a polygraph (Grass Instruments, Quincy, MA) and was maintained at 110 mmHg throughout the experiment. The tissue surface was continuously bathed with Tyrode's solution at 37°C containing 10 g/l bovine serum albumin, approximating the composition of renal interstitial fluid. Stock solutions containing vasoactive agents were stored at −20°C until the day of the experiment, at which time they were diluted with Tyrode's bath to the appropriate final concentrations.

Videometric techniques were used to measure arteriolar lumen diameter. The tissue was transilluminated on the fixed stage of a Nikon Optiphot microscope equipped with a water-immersion objective (×40, numerical aperture 0.55). Enhanced video images of the microvessels were displayed at a magnification of ×1,400 on a high-resolution monitor and recorded simultaneously on a DVD recorder. During the 10- to 15-min equilibration period, an afferent arteriole was selected for study based on visibility and acceptable blood flow. Only arterioles with rapid flow of erythrocytes were studied, and vessels were rejected on the basis of inadequate flow if the passage of single erythrocytes could be discerned. All experimental protocols were designed to assess arteriolar diameter at a single measurement site under several experimental conditions. In kidneys from one normal rat and two STZ rats, two vessels could be visualized within the same field of view, thus allowing images of both vessels to be recorded simultaneously and analyzed separately during playback. Afferent arteriolar lumen diameter was monitored at sites located >100 μm upstream from the glomerulus and >80 μm downstream from the interlobular artery. Diameter was measured at 12-s intervals, with the average diameter (in μm) during the final minutes of each treatment period utilized for statistical analysis. Each experiment followed one of the specific protocols detailed below.

Afferent arteriolar diameter responses to barium.

The effect of Ba2+, a broad-spectrum KIR channel blocker, was used to assess the tonic impact of KIR channels on afferent arteriolar diameter in kidneys from STZ rats (STZ kidneys) and normal rats (normal kidneys). Lumen diameter responses to Ba2+ were measured during exposure of the kidney surface to the following solutions: 1) Tyrode's bath alone (10 min); 2) Tyrode's bath containing 10, 30, and 100 μM BaCl (5 min each); and 3) Tyrode's bath alone (10 min). After full recovery from the Ba2+ treatment, the tissue was exposed to 20 mM KCl to document the absence/presence of a dilator response to the classic stimulus for KIR channel activation. Published reports indicate that 20 mM K+ evokes Ba2+-sensitive arteriolar dilation that is equal to or greater than the response to 15 mM K+ in various vascular beds (3, 38, 48).

Afferent arteriolar diameter responses to tertiapin-Q and tetraethylammonium.

Tertiapin-Q (TPQ) reversibly blocks the Kir1.1 and Kir3.x families of inward rectifier channels (30). The effect of TPQ was measured in afferent arterioles of normal kidneys and STZ kidneys, using a protocol involving sequential exposure to the following solutions: 1) Tyrode's bath alone (10 min); 2) Tyrode's bath containing 1, 10, and 100 nM TPQ (5 min each); and 3) Tyrode's bath alone (10 min). In some kidneys, recovery from the initial TPQ challenge was followed by exposure to Tyrode's solution containing 1 mM tetraethylammonium (TEA; 5 min; a BKCa channel blocker), with a final recovery period at the end of the experiment (Tyrode's bath alone; 10 min). Because Kir1.1 channels are prominently expressed in the thick ascending limb, TPQ might alter solute delivery to the macula densa, thereby influencing arteriolar tone via tubuloglomerular feedback. To address this possibility, in some kidneys recovery from the initial TPQ treatment was followed by acute surgical papillectomy to physically open the tubuloglomerular feedback loop (25, 51). Ten minutes later, the 1–100 nM TPQ challenge was repeated, followed by a final recovery period (Tyrode's bath alone).

Afferent arteriolar diameter responses to 4-aminopyridine and apamin.

Additional experiments were conducted to test the effects of 4-aminopyridine [4-AP; a reversible KV channel blocker (49)] and apamin [a SKCa channel blocker (1)] on afferent arteriolar tone in STZ kidneys and normal kidneys. Afferent arteriolar lumen diameter responses to the following drug solutions were documented: 1) Tyrode's bath alone (10 min); 2) Tyrode's solution containing 0.1, 0.3, 1.0, and 3.0 mM 4-AP (5 min each); 3) Tyrode's bath alone (10 min); 4) Tyrode's solution containing 100 nM apamin (5 min); and 5) Tyrode's bath alone (10 min).

Reagents.

TPQ was purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO), methohexital sodium (Brevital) was from Eli Lilly (Indianapolis, IN), and pentobarbital sodium (Nembutal) was from Ovation Pharmaceuticals (Deerfield, IL). All other chemicals and reagents were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). The Tyrode's solution was composed of (in mM) 1.8 CaCl2·2H2O, 1 MgCl2·6H2O, 2.7 KCl, 137 NaCl, 0.4 Na2HPO4, 12 NaHCO3, and either 5.5 or 20 d-glucose (for tissue from normal and STZ, rats, respectively).

Statistical analyses.

Simple between-group comparisons were made by t-test or the Mann-Whitney rank sum test. Effects of pharmacological agents on arteriolar lumen diameter in normal and STZ rats were evaluated using two-way repeated-measures ANOVA and, when appropriate, the Holm-Sidak multiple comparisons test. These analyses were accomplished using SigmaStat 3.11 software (Systat, San Jose, CA). A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data are presented as means ± SE (n = number of arterioles, unless otherwise stated).

RESULTS

Table 1 provides basic information characterizing normal and STZ rats used in this study. Blood glucose levels were significantly elevated in STZ rats, compared with representative values evident in a random sampling of the normal rats used in this study. Body weight at the time of the terminal experiment was less in STZ rats than in age-matched normal rats. In addition, baseline afferent arteriolar lumen diameter was significantly larger in STZ kidneys compared with normal kidneys. These observations mirror our previous reports comparing STZ rats with rats receiving sham (vehicle) treatments.

Table 1.

General characteristics of STZ-treated rats and normal rats used in the present study

| Normal Rats | STZ Rats | |

|---|---|---|

| Initial body wt, g | 299±3 (n = 26 rats) | |

| Body wt at terminal experiment, g | 361±10 (n = 5 rats) | 331±4* (n = 26 rats) |

| Blood glucose concentration†, mg/dl | 95±5 (n = 6 rats) | 369±13* (n = 26 rats) |

| Baseline afferent arteriolar lumen diameter, μm | 17.8±0.6 (n = 25 arterioles) | 23.5±0.9* (n = 28 arterioles) |

Blood glucose concentrations represent values obtained from normal rats on the day of the terminal experiment, and the average values for streptozotocin (STZ) rats measured over the 3 wk before the terminal experiment.

P < 0.05 vs. normal rats.

Figure 1 compares the afferent arteriolar lumen diameter responses of normal and STZ kidneys to treatment with increasing concentrations of Ba2+. In these experiments, baseline arteriolar lumen diameter averaged 16.3 ± 1.2 μm (n = 6) in normal kidneys and 23.0 ± 1.7 μm (n = 9) in STZ kidneys (P < 0.05). In normal kidneys, afferent diameter tended to progressively decrease in response to increasing bath Ba2+ concentration, but this effect achieved statistical significance only during exposure to 100 μM Ba2+ (18 ± 5% decrease in diameter). In STZ kidneys, afferent diameter was also progressively reduced in response to increasing extracellular concentrations of Ba2+; however, the constrictor response was significant at the lowest concentration of Ba2+ employed (10 μM; 13 ± 5% decrease in diameter) and the responses to 30 and 100 μM Ba2+ were significantly exaggerated relative to normal kidneys. Overall, afferent arteriolar diameter responses to Ba2+ in STZ kidneys were about twice the magnitude of responses evident in normal kidneys. Ultimately, the exaggerated contractile response to Ba2+ in STZ kidneys restored arteriolar lumen diameter to values that did not differ significantly from normal kidneys, even during 100 μM Ba2+ treatment. The effects of Ba2+ were reversible, with arteriolar diameters returning to 98 ± 2 and 95 ± 4% of baseline in normal and STZ kidneys, respectively, during the post-Ba2+ recovery period. Subsequent exposure to 20 mM K+ provoked a 3.1 ± 1.2-μm increase in afferent arteriolar diameter in normal kidneys (n = 6; P < 0.05 vs. post-Ba2+ recovery period), but no significant change in arteriolar diameter in STZ kidneys (Δ = 1.8 ± 2.7 μm; n = 7; P > 0.52 vs. post-Ba2+ recovery period). Thus, afferent arterioles in normal kidneys exhibited constrictor responses to Ba2+ and dilator responses to 20 mM K+, while arterioles in STZ kidneys showed exaggerated responses to Ba2+ and no significant effect of 20 mM K+.

Fig. 1.

Effects of barium on afferent arteriolar diameter in normal kidneys (closed symbols; n = 6 arterioles) and streptozotocin (STZ) kidneys (open symbols; n = 9 arterioles). Actual lumen diameter (left) and change in lumen diameter data (right) show vasoconstrictor responses to 10, 30, and 100 μM Ba2+. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. baseline diameter. †P < 0.05 vs. arterioles from normal kidneys.

Figure 2 shows concentration-dependent responses of afferent arterioles from normal and STZ kidneys to TPQ (blocks Kir1.1 and Kir3.x families of KIR channels). Baseline lumen diameter was significantly greater in STZ kidneys (22.2 ± 0.5 μm; n = 11) than in normal kidneys (18.0 ± 0.7 μm; n = 14). Increasing concentrations of TPQ (1–100 nM) did not alter afferent arteriolar diameter in normal kidneys; in contrast, 100 nM TPQ evoked a 22 ± 4% decrease in afferent arteriolar diameter in STZ kidneys. It is evident from Fig. 2 that 100 nM TPQ alleviated the afferent arteriolar diameter difference between normal and STZ kidneys. Thus, although TPQ did not alter afferent diameter in normal kidneys, it reversed the afferent arteriolar dilation typically evident in STZ kidneys, thereby implicating TPQ-sensitive KIR channels in reduced afferent arteriolar tone during diabetes.

Fig. 2.

Effects of increasing tertiapin-Q (TPQ) concentration on afferent arteriolar diameter in normal kidneys (closed symbols; n = 14 arterioles) and STZ kidneys (open symbols; n = 11 arterioles). Actual lumen diameter (left) and change in lumen diameter data (right) show vasoconstrictor responses to 1, 10, and 100 nM TPQ. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. baseline diameter. †P < 0.05 vs. arterioles from normal kidneys.

During the post-TPQ recovery period, afferent arteriolar lumen diameter was restored to 96 ± 2 and 98 ± 3% of baseline in normal and STZ kidneys, respectively. In about half of the experiments comprising Fig. 2, the post-TPQ recovery period was followed by acute surgical papillectomy to physically open the tubuloglomerular feedback loop. Subsequently, the TPQ challenge was repeated. Papillectomy caused a modest but statistically significant increase in afferent arteriolar lumen diameter (Δ = 0.7 ± 0.3 μm; n = 7; P = 0.035) in normal kidneys, but did not alter afferent diameter in STZ kidneys (Δ = 0.0 ± 0.5 μm; n = 6). After papillectomy, responses to 1–100 nM TPQ mimicked those evident in the same vessels before papillectomy. Figure 3 summarizes the changes in diameter evoked by 100 nM TPQ before and after papillectomy. In normal kidneys, 100 nM TPQ did not alter arteriolar diameter before or after papillectomy, while TPQ decreased lumen diameter in STZ kidneys by 26 ± 4% with papilla intact and 21 ± 6% after papillectomy. Thus, acute surgical papillectomy did not prevent the ability of TPQ to evoke afferent arteriolar constriction in STZ kidneys, suggesting that the phenomenon arises independent of tubuloglomerular feedback.

Fig. 3.

Afferent arteriolar responses to TPQ measured in normal kidneys (n = 7 arterioles) and STZ kidneys (n = 6 arterioles) before (filled bars) and after (open bars) acute surgical papillectomy. These data were obtained from a subset of the vessels used to generate Fig. 2. Data are shown as the change in lumen diameter in response to 100 nM TPQ. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. baseline diameter. †P < 0.05 vs. response in normal kidneys. No significant effect of papillectomy was evident in either group.

In the remaining experiments comprising Fig. 2, the post-TPQ recovery was followed by subsequent exposure to TEA (papilla intact). Figure 4 illustrates the modest diameter response to 1 mM TEA evident in normal kidneys (9 ± 4% decrease in diameter; n = 6) and STZ kidneys (9 ± 5% decrease in diameter; n = 5). Constrictor responses to TEA were comparable in afferent arterioles of normal and STZ kidneys, despite the differing baseline diameters and responsiveness to TPQ treatment evident in the same arterioles, indicating that the tonic impact of BKCa channels on afferent arteriolar tone is unaltered in diabetes.

Fig. 4.

Effects of tetraethylammonium (TEA) on afferent arteriolar diameter in normal kidneys (closed symbols; n = 6 arterioles) and STZ kidneys (open symbols; n = 5 arterioles). These data were obtained from a subset of the vessels used to generate Fig. 2. Actual lumen diameter (left) and change in lumen diameter data (right) show vasoconstrictor responses to 1 mM TEA. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. baseline diameter. †P < 0.05 vs. arterioles from normal kidneys.

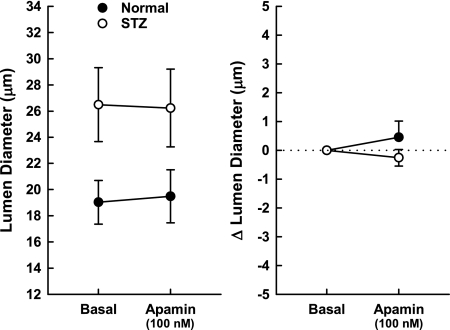

The final set of experiments explored the contribution of KV channels and SKCa channels to afferent arteriole tone in normal and STZ kidneys having baseline diameters of 19.2 ± 1.2 μm (n = 6) and 27.3 ± 3.1 μm (n = 6; P < 0.05), respectively. Exposure of the tissue to increasing concentrations of 4-AP elicited concentration-dependent decreases in afferent lumen diameter in both normal and STZ kidneys (Fig. 5). In normal kidneys, significant decreases in diameter were apparent at 4-AP concentrations ≥0.3 mM, while the response in STZ kidneys only achieved statistical significance during exposure to 3 mM 4-AP. In both normal and STZ kidneys, 3 mM 4-AP decreased afferent diameter by ∼20%. This response was fully reversible upon removal of 4-AP from the bath. Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA revealed no significant interaction (P = 0.33) between treatment group (normal vs. STZ) and the diameter response to 4-AP. Thus, while these experiments revealed a significant tonic dilator impact of 4-AP-sensitive KV channels on afferent arteriolar tone, the data fail to provide evidence that diabetes alters this phenomenon. In most of these arterioles, the post-4-AP recovery period was followed by exposure to 100 nM apamin. As illustrated in Fig. 6, apamin did not change afferent arteriolar lumen diameter in either normal or STZ kidneys. Thus, apamin-sensitive SKCa channels exert no significant tonic dilator impact on afferent arteriolar tone under these conditions.

Fig. 5.

Effects of increasing concentrations of 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) on afferent arteriolar diameter in normal kidneys (closed symbols; n = 6 arterioles) and STZ kidneys (open symbols; n = 6 arterioles). Data expressed as actual lumen diameter (left) and change in lumen diameter (right) show vasoconstrictor responses to 0.1, 0.3, 1, and 3 mM 4-AP. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. baseline diameter. †P < 0.05 vs. arterioles from normal kidneys.

Fig. 6.

Effects of apamin on afferent arteriolar diameter in normal rats (closed symbols; n = 5 arterioles) and STZ rats (open symbols; n = 6 arterioles). Data expressed as actual lumen diameter (left) and change in lumen diameter (right) show the lack of any response to 100 nM apamin. Values are means ± SE.

DISCUSSION

In our hands, rats with moderately hyperglycemic STZ-induced T1D exhibit polyuria, polydipsia, polyphagia, renal hypertrophy, and glomerular hyperfiltration (37, 50). The hyperfiltration results from decreased afferent arteriolar tone (44), the mechanism of which remains largely speculative. Therefore, the present study employed a pharmacological approach to determine the role of various K+ channels in determining afferent arteriolar tone in normal rat kidney and in rats with STZ-induced T1D. The data reveal that Ba2+-, TEA-, and 4-AP-sensitive mechanisms exert a tonic vasodilator influence on the normal afferent arteriole, with no discernible impact of TPQ- and apamin-sensitive processes under these conditions. In the diabetic animals, however, Ba2+-sensitive regulation of afferent arteriolar tone is augmented and a TPQ-sensitive tonic dilator influence emerges. Because these pharmacological agents target various K+ channel families, our observations suggest that T1D alters the relative impact of specific K+ channels on membrane potential in the afferent arteriole–presumably in the resident vascular smooth muscle cells.

Although millimolar concentrations of Ba2+ can inhibit some KV channel subtypes (19), the specific blockade of KIR channels achieved by micromolar concentrations of Ba2+ has been exploited in countless physiological studies. An afferent arteriolar constrictor impact of Ba2+ has been demonstrated by Loutzenhiser and colleagues (11, 12) in studies utilizing the rat isolated, perfused hydronephrotic kidney. Results of the present study confirm that the afferent arteriole contracts in a concentration-dependent manner in response to Ba2+, although the contractile responses to Ba2+ in the present study were of smaller magnitude than those evident in the hydronephrotic kidney (12). This disparity may reflect quantitative differences in responsiveness of midouter cortical nephrons vs. juxtamedullary nephrons, or the fact that the hydronephrotic kidney studies were performed at low perfusion pressure (80 mmHg) to maximally dilate the vessel, thereby facilitating investigation of KIR involvement in the myogenic response. The higher perfusion pressure (110 mmHg) utilized in the present study, together with the impact of circulating constrictor agents in the perfusate blood (5), would provoke partial depolarization of the vascular smooth muscle and greater active tone. This situation may reduce the tonic contribution of KIR channels on vascular tone under our experimental conditions, compared with the isolated, perfused hydronephrotic kidney. Nevertheless, it is clear that Ba2+-sensitive mechanisms (presumably KIR channels) exert a tonic vasodilator influence on the afferent arteriole. Importantly, the exaggerated contractile response to Ba2+ evident in arterioles of STZ kidneys suggests that an increased tonic influence of KIR channels contributes to afferent arteriolar dilation during this stage of diabetes.

A long-recognized limitation of attempts to investigate the role of KIR channels in vascular control is the lack of pharmacological tools that distinguish between the seven KIR subfamilies, each of which has different electrophysiological characteristics, tissue distributions, and regulatory mechanisms (35). Ba2+-sensitive Kir2.1 channels are expressed in rat afferent and efferent arterioles (11) and are widely considered to be the primary KIR channel in vascular smooth muscle (29). Kir2.1 channels are necessary to evoke the vasodilator response to increases in extracellular [K+] (57), such as those evident in afferent arterioles of the hydronephrotic rat kidney (11, 12) and the normal kidneys of the present study. In some vascular beds (especially skeletal muscle), elevation of extracellular [K+] can elicit hyperpolarization and vasodilation by stimulating the electrogenic Na+-K+-ATPase (3, 39). However, Chilton and Loutzenhiser (12) found K+-induced dilation of the rat renal afferent arteriole to be ouabain-insensitive but blocked by Ba2+, suggesting a predominant role of Kir2.1 in this response. Noting that afferent arterioles from STZ kidneys failed to exhibit significant K+-induced dilation, while showing exaggerated contractile responses to Ba2+, it is possible that the available Kir2.1 channels are tonically open in the afferent arteriole during T1D, perhaps due to a shift in inward rectification. However, it should be noted that other KIR channel subtypes with varying Ba2+ sensitivities also reside in the kidney and may contribute to the exaggerated afferent arteriolar contractile response to Ba2+ in T1D. For example, Kir2.2 and Kir2.3 are present in descending vasa recta (4), while Kir1.1 (the ROMK channel) is highly expressed in the thick ascending limb and cortical collecting duct (54). Neither these nor other KIR channel subtypes (except Kir2.1) have been reported to reside in the afferent arteriole, but we note that no studies have addressed this possibility.

As an initial attempt to identify KIR channel subtypes that contribute to reduced afferent arteriolar tone during T1D, experiments were performed using TPQ, a bee venom toxin that inhibits Kir1.1 and Kir3.x channels (9, 30). Our observation that 100 nM TPQ decreases afferent arteriolar diameter in STZ kidneys, but not in normal kidneys, suggests a role for TPQ-sensitive KIR channels in the vasodilation seen during the hyperfiltration stage of T1D. The literature provides few studies implicating TPQ-sensitive events in the control of vascular function under any conditions. Specifically, 1 μM TPQ attenuates urocortin-induced relaxation of coronary artery rings and 17β-estradiol-induced relaxation of mesenteric artery rings (23, 52). In addition, 10 μM TPQ attenuates relaxant responses of mesenteric resistance arteries to endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor and C-type natriuretic peptide (10). Our results extend these observations to suggest that TPQ-sensitive channels can influence vascular function at the microvascular level, evident as the emergence of a tonic vasodilator influence of these channels on the afferent arteriole during T1D; however, the mechanism underlying this phenomenon remains to be determined.

TPQ inhibits K+ currents with Ki values of ∼1 nM for Kir1.1 channels and 10 nM for Kir3.x channels, with no effects of 1 μM TPQ on Kir2.1, KATP, KV, or L-type VGCCs (31, 34). Some evidence indicates that 100 nM TPQ can inhibit BKCa channels expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes (32); however, the irreversibility of TPQ-induced BKCa channel blockade (even 90 min after TPQ washout) is in striking contrast to the rapidly reversible effects of TPQ on Kir1.1 currents (9). Thus, the rapidly reversible afferent arteriolar contractile response to TPQ evident in the present study likely reflects the impact of this agent on Kir1.1 and/or Kir3.x channels, rather than on BKCa channels. TPQ-sensitive Kir3.x channels are expressed in neurons, atrial myocytes, and neuroendocrine cells, with tetrameric assemblies of Kir3.x subunits comprising the G protein-coupled inwardly rectifying K channels (GIRKs) that regulate neuronal excitability and heart rate (35). Kir3.1 mRNA has been detected in aortic vascular smooth muscle, where it is unaltered during T1D (47), but we are unaware of any evidence indicating protein expression or functional Kir3.x channels in the vasculature or in the kidney. On the other hand, Kir1.1 channels are expressed at the mRNA and protein levels in the renal cortical collecting duct, connecting tubule, distal convoluted tubule, macula densa, and thick ascending limb (54). In the thick ascending limb, K+ recycling across the apical membrane via Kir1.1 channels is essential for maintaining function of the Na-K-2Cl cotransporter and, hence, Na+ reabsorption. One can envision a demand for increased apical K+ recycling in the thick ascending limb to sustain the increased Na+ reabsorption by this nephron segment during T1D, thereby decreasing solute concentration in early distal tubular fluid and presumably at the macula densa (45, 53). In this manner, Kir1.1-dependent mechanisms in the thick ascending limb could contribute to tubuloglomerular feedback-mediated afferent arteriolar dilation during T1D. However, results of the present study failed to reveal any impact of acute surgical papillectomy on the vasoconstrictor response to TPQ in STZ kidneys, thus making it unlikely that TPQ-sensitive Kir1.1 channels in the thick ascending limb influence afferent arteriolar diameter during T1D by evoking a tubuloglomerular feedback response. As papillectomy would also abolish flow of tubular fluid through the connecting tubule, it is also unlikely that changes in Kir1.1 expression/function in that nephron segment underlie afferent arteriolar dilation during T1D via the connecting tubule-glomerular feedback system (46). We cannot rule out the possibility that Kir1.1 channels in macula densa or the connecting tubule tonically influence afferent arteriolar tone during T1D independent of solute delivery. Alternatively, expression of TPQ-sensitive channels in afferent arteriolar smooth muscle or endothelial cells may be induced or gain functional relevance during T1D, thereby contributing to the preglomerular vasodilation underlying diabetic hyperfiltration. Extensive further investigation is necessary to evaluate the validity of these scenarios that may underlie emergence of a tonic afferent arteriolar dilator impact of TPQ-sensitive channels in T1D.

In addition to evaluating the impact of KIR channels on afferent arteriolar tone in kidneys from normal and STZ rats, the present study also explored the impact of other K+ channels known to be expressed in the vasculature. At the concentration used in the present study (1 mM), TEA is widely employed as a potent blocker of BKCa channels (2, 28, 36), although some KV channel subclasses expressed in the vasculature may also be influenced (KV1.1 and KV3.x) (13, 19). To date, the only KV channel detected by patch clamp study of renal microvascular smooth muscle is a 46-pS channel, probably a delayed rectifier, that is insensitive to TEA (58). Intrarenal arterial administration of TEA evokes modest vasoconstriction that is not mimicked by iberiotoxin (a highly selective BKCa channel blocker), suggesting that TEA has in vivo renal vascular effects that arise independent of BKCa channel blockade (41). However, in studies of afferent arteriolar function using the in vitro blood-perfused juxtamedullary nephron technique, the effects of 1 mM TEA and 100 nM iberiotoxin are virtually indistinguishable (15, 26). Thus, it is likely that the effect of TEA on afferent arteriolar diameter in this experimental setting largely reflects the impact of BKCa channels in maintenance of arteriolar tone. This effect was of modest magnitude in arterioles of normal kidneys, in accord with our previous observations (15), indicating that these channels do not play a major role in the control of basal juxtamedullary afferent arteriolar tone. Moreover, quantitatively similar effects of TEA were observed in normal and STZ kidneys, suggesting that increased BKCa channel activity does not significantly contribute to the tonic afferent arteriolar dilation during T1D.

The involvement of KV channels as determinants of afferent arteriolar tone was explored through use of 4-AP, which blocks KV channels with Ki values in the range of 0.2-l.5 mM (19). In renal microvascular smooth muscle cells, 4-AP blocks the 46-pS KV channel and transient outward current attributed to KV channels, but has no effect on BKCa channels (18, 58). As previous studies showed that 4-AP modestly potentiates the afferent arteriolar myogenic response (33), it is not surprising to find that 4-AP constricts afferent arterioles of in vitro blood-perfused juxtamedullary nephrons studied at a perfusion pressure above the autoregulatory threshold; however, the contractile response to 4-AP did not differ significantly between normal and STZ kidneys. Thus, although these data confirm that KV channels contribute significantly to afferent arteriolar tone in the normal kidney, they provide no evidence that these channels are responsible for the dilation that occurs during T1D.

Published evidence indicates that 50 nM apamin, a selective blocker of SKCa channels (1), inhibits a 68-pS Ca2+-activated K+ channel but not the BKCa channel in preglomerular microvascular smooth muscle cells (16). Although these 68-pS channels have a higher conductance than generally attributed to SKCa channels (55), 50 nM apamin also reduced macroscopic K+ current recorded from voltage-clamped renal arteriolar muscle cells by 25–30% (16), suggesting that apamin-sensitive channels may play a significant role in setting membrane potential and baseline tone in the afferent arteriole. However, results of the present study failed to reveal any impact of 100 nM apamin on juxtamedullary afferent arteriolar tone in either normal or STZ kidneys. Thus, the role of apamin-sensitive SKCa channels in control of the renal microvasculature remains speculative.

In conclusion, the main findings of this study are 1) KV, KIR, and BKCa channels exert tonic dilator influences on the normal afferent arteriole, while SKCa channels have no discernible tonic impact; 2) tonic activation of KIR channels (likely Kir2.1, as well as Kir1.1 and/or Kir3.x) contributes to the afferent arteriolar dilation during T1D; and 3) the dilator impact of Kir1.1/Kir3.x channels during T1D is evident regardless of solute delivery to the macula densa. Further investigation is necessary to establish whether these phenomena involve changes in channel activity in the endothelium and/or vascular smooth muscle. In one scenario, K+ efflux through endothelial K+ channels might elevate K+ concentration near the vascular smooth muscle, increasing the current carried by KIR channels in the vascular smooth muscle to elicit hyperpolarization (14). It is not clear how T1D might trigger changes in K+ channel regulation of afferent arteriolar tone. These changes may reflect effects of hyperglycemia per se, renin-angiotensin system activation, oxidative stress, protein kinase C activation, or other downstream events. It is also interesting to note that K+ channel regulation of vascular tone in the renal afferent arteriole contrasts with events occurring in the basilar artery and pial arterioles studied under normal conditions, as well as after a longer duration of T1D (42), suggesting that these events are not uniform across different vascular beds. In the renal afferent arteriole, increased tonic K channel activity [KATP, as previously reported (24); and KIR channel family members, per the present study] should favor vascular smooth muscle hyperpolarization that, together with concomitant changes in Ca2+ channel responsiveness to membrane potential (7), can be envisioned to act synergistically to promote afferent arteriolar dilation during the hyperfiltration stage of T1D.

GRANTS

This work was supported by funding from the Nebraska Tobacco Settlement Biomedical Research Development Fund (NTSBRDF) and the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant DK-071152.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blatz AL, Magleby KL. Single apamin-blocked Ca-activated K+ channels of small conductance in cultured rat skeletal muscle. Nature 323: 718–720, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brayden JE, Nelson MT. Regulation of arterial tone by activation of calcium-dependent potassium channels. Science 256: 532–535, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burns WR, Cohen KD, Jackson WF. K+-induced dilation of hamster cremasteric arterioles involves both the Na+/K+-ATPase and inward-rectifier K+ channels. Microcirculation 11: 279–293, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cao C, Lee-Kwon W, Payne K, Edwards A, Pallone TL. Descending vasa recta endothelia express inward rectifier potassium channels. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F1248–F1255, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carmines PK, Inscho EW. Perfusate composition modulates in vitro renal microvascular pressure responsiveness in a segment-specific manner. Microvasc Res 43: 347–351, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carmines PK, Navar LG. Disparate effects of Ca channel blockade on afferent and efferent arteriolar responses to ANG II. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 256: F1015–F1020, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carmines PK, Ohishi K, Ikenaga H. Functional impairment of renal afferent arteriolar voltage-gated calcium channels in rats with diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest 98: 2564–2571, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casellas D, Navar LG. In vitro perfusion of juxtamedullary nephrons in rats. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 246: F349–F358, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cha TJ, Ehrlich JR, Chartier D, Qi XY, Xio L, Nattel S. Kir3-based inward rectified potassium current: potential role in atrial tachycardia remodeling effects on atrial repolarization and arrhythmias. Circulation 113: 1730–1737, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chauhan SD, Nilsson H, Ahluwalia A, Hobbs AJ. Release of C-type natriuretic peptide accounts for the biological activity of endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 1426–1431, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chilton L, Loutzenhiser K, Morales E, Breaks J, Kargacin GJ, Loutzenhiser R. Inward rectifier K+ currents and Kir2.1 expression in renal afferent and efferent arterioles. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 69–76, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chilton L, Loutzenhiser R. Functional evidence for an inward rectifier potassium current in rat renal afferent arterioles. Circ Res 88: 152–158, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cox RH Molecular determinants of voltage-gated potassium channels in vascular smooth muscle. Cell Biochem Biophys 42: 167–195, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edwards G, Dora KA, Gardener MJ, Garland CJ, Weston AH. K+ is an endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor in rat arteries. Nature 396: 269–272, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fallet RW, Bast JP, Fujiwara K, Ishii N, Sansom SC, Carmines PK. Influence of Ca2+-activated K+ channels on rat renal arteriolar responses to depolarizing agonists. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 280: F583–F591, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gebremedhin D, Kaldunski M, Jacobs ER, Harder DR, Roman RJ. Coexistence of two types of Ca2+-activated K+ channels in rat renal arterioles. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 270: F69–F81, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giunti S, Barit D, Cooper ME. Diabetic nephropathy: from mechanisms to rational therapies. Minerva Med 97: 241–262, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordienko DV, Clausen C, Goligorsky MS. Ionic currents and endothelin signaling in smooth muscle cells from rat renal resistance arteries. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 266: F325–F341, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gutman GA, Chandy KG, Grissmer S, Lazdunski M, Mckinnon D, Pardo LA, Robertson GA, Rudy B, Sanguinetti MC, Stuhmer W, Wang X. International Union of Pharmacology. LIII. Nomenclature and molecular relationships of voltage-gated potassium channels. Pharmacol Rev 57: 473–508, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayabuchi Y, Nakaya Y, Matsuoka S, Kuroda Y. Hydrogen peroxide-induced vascular relaxation in porcine coronary arteries is mediated by Ca2+-activated K+ channels. Heart Vessels 13: 9–17, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hostetter TH Diabetic nephropathy: metabolic versus hemodynamic considerations. Diabetes Care 15: 1205–1215, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hostetter TH, Troy JL, Brenner BM. Glomerular hemodynamics in experimental diabetes mellitus. Kidney Int 19: 410–415, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang Y, Chan FL, Lau CW, Tsang SY, He GW, Chen ZY, Yao X. Urocortin-induced endothelium-dependent relaxation of rat coronary artery: role of nitric oxide and K+ channels. Br J Pharmacol 135: 1467–1476, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ikenaga H, Bast JP, Fallet RW, Carmines PK. Exaggerated impact of ATP-sensitive K+ channels on afferent arteriolar diameter in diabetes mellitus. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 1199–1207, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ikenaga H, Fallet RW, Carmines PK. Contribution of tubuloglomerular feedback to renal arteriolar angiotensin II responsiveness. Kidney Int 49: 34–39, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Imig JD, Dimitropoulou C, Reddy DS, White RE, Falck JR. Afferent arteriolar dilation to 11,12-EET analogs involves PP2A activity and Ca2+-activated K+ channels. Microcirculation 15: 137–150, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Imig JD, Zou AP, Stec DE, Harder DR, Falck JR, Roman RJ. Formation and actions of 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid in rat renal arterioles. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 270: R217–R227, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iwatsuki N, Petersen OH. Action of tetraethylammonium on calcium-activated potassium channels in pig pancreatic acinar cells studied by patch-clamp single-channel and whole-cell current recording. J Membr Biol 86: 139–144, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jackson WF Potassium channels in the peripheral microcirculation. Microcirculation 12: 113–127, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jin W, Klem AM, Lewis JH, Lu Z. Mechanisms of inward-rectifier K+ channel inhibition by Tertiapin-Q. Biochemistry 38: 14294–14301, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jin W, Lu Z. Synthesis of a stable form of tertiapin: a high-affinity inhibitor for inward-rectifier K+ channels. Biochemistry 38: 14286–14293, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kanjhan R, Coulson EJ, Adams DJ, Bellingham MC. Tertiapin-Q blocks recombinant and native large conductance K+ channels in a use-dependent manner. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 314: 1353–1361, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kirton CA, Loutzenhiser R. Alterations in basal protein kinase C activity modulate renal afferent arteriolar myogenic reactivity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 275: H467–H475, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kitamura H, Yokoyama M, Akita H, Matsushita K, Kurachi Y, Yamada M. Tertiapin potently and selectively blocks muscarinic K+ channels in rabbit cardiac myocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 293: 196–205, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kubo Y, Adelman JP, Clapham DE, Jan LY, Karschin A, Kurachi Y, Lazdunski M, Nichols CG, Seino S, Vandenberg CA. International Union of Pharmacology. LIV. Nomenclature and molecular relationships of inwardly rectifying potassium channels. Pharmacol Rev 57: 509–526, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Langton PD, Nelson MT, Huang Y, Standen NB. Block of calcium-activated potassium channels in mammalian arteriolar myocytes by tetraethylammonium ions. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 260: H927–H934, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee DL, Sasser JM, Hobbs JL, Boriskie A, Pollock DM, Carmines PK, Pollock JS. Posttranslational regulation of NO synthase activity in the renal medulla of diabetic rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 288: F82–F90, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Loeb AL, Gödény I, Longnecker DE. Functional evidence for inward-rectifier potassium channels in rat cremaster muscle arterioles. Microvasc Res 59: 1–6, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lombard JH, Stekiel WJ. Responses of cremasteric arterioles of spontaneously hypertensive rats to changes in extracellular K+ concentration. Microcirculation 2: 355–362, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lorenz JN, Schnermann J, Brosius FC, Briggs JP, Furspan PB. Intracellular ATP can regulate afferent arteriolar tone via ATP-sensitive K+ channels in the rabbit. J Clin Invest 90: 733–740, 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Magnusson L, Sorensen CM, Braunstein TH, Holstein-Rathlou NH, Salomonsson M. Renovascular BKCa channels are not activated in vivo under resting conditions and during agonist stimulation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 292: R345–R353, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mayhan WG, Mayhan JF, Sun H, Patel KP. In vivo properties of potassium channels in cerebral blood vessels during diabetes mellitus. Microcirculation 11: 605–613, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ohishi K, Carmines PK, Inscho EW, Navar LG. EDRF-angiotensin II interactions in rat juxtamedullary afferent and efferent arterioles. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 263: F900–F906, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ohishi K, Okwueze MI, Vari RC, Carmines PK. Juxtamedullary microvascular dysfunction during the hyperfiltration stage of diabetes mellitus. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 267: F99–F105, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pollock CA, Lawrence JR, Field MJ. Tubular sodium handling and tubuloglomerular feedback in experimental diabetes mellitus. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 260: F946–F952, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ren Y, Garvin JL, Liu R, Carretero OA. Crosstalk between the connecting tubule and the afferent arteriole regulates renal microcirculation. Kidney Int 71: 1116–1121, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ren Y, Xu X, Wang X. Altered mRNA expression of ATP-sensitive and inward rectifier potassium channel subunits in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat heart and aorta. J Pharm Sci 93: 478–483, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rivers RJ, Hein TW, Zhang C, Kuo L. Activation of barium-sensitive inward rectifier potassium channels mediates remote dilation of coronary arterioles. Circulation 104: 1749–1753, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Robertson BE, Nelson MT. Aminopyridine inhibition and voltage dependence of K+ currents in smooth muscle cells from cerebral arteries. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 267: C1589–C1597, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sasser JM, Sullivan JC, Hobbs JL, Yamamoto T, Pollock DM, Carmines PK, Pollock JS. Endothelin A receptor blockade reduces diabetic renal injury via an anti-inflammatory mechanism. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 143–154, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takenaka T, Harrison-Bernard LM, Inscho EW, Carmines PK, Navar LG. Autoregulation of afferent arteriolar blood flow in juxtamedullary nephrons. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 267: F879–F887, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsang SY, Yao X, Chan HY, Wong CM, Chen ZY, Au CL, Huang Y. Contribution of K+ channels to relaxation induced by 17β-estradiol but not by progesterone in isolated rat mesenteric artery rings. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 41: 4–13, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vallon V, Richter K, Blantz RC, Thomson S, Osswald H. Glomerular hyperfiltration in experimental diabetes mellitus: potential role of tubular reabsorption. J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 2569–2576, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang W Renal potassium channels: recent developments. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 13: 549–555, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wei AD, Gutman GA, Aldrich R, Chandy KG, Grissmer S, Wulff H. International Union of Pharmacology. LII. Nomenclature and molecular relationships of calcium-activated potassium channels. Pharmacol Rev 57: 463–472, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yokoshiki H, Sunagawa M, Seki T, Sperelakis N. ATP-sensitive K+ channels in pancreatic, cardiac, and vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 274: C25–C37, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zaritsky JJ, Eckman DM, Wellman GC, Nelson MT, Schwarz TL. Targeted disruption of Kir2.1 and Kir2.2 genes reveals the essential role of the inwardly rectifying K+ current in K+-mediated vasodilation. Circ Res 87: 160–166, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zou AP, Fleming JT, Falck JR, Jacobs ER, Gebremedhin D, Harder DR, Roman RJ. 20-HETE is an endogenous inhibitor of the large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel in renal arterioles. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 270: R228–R237, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]