Preface

10 years ago it was reported that overexpression of the oncogene c-Myc in human epidermal stem cells stimulates differentiation rather than uncontrolled proliferation. This was, understandably, greeted with scepticism by researchers. However, subsequent studies have confirmed that Myc can stimulate epidermal stem cells to differentiate and shed light on the underlying mechanisms. Two cancer relevant concepts emerge. First, Myc regulates similar genes in different cell types, but the biological consequences are context-dependent. Second, Myc activation is not a simple ‘on/off’ switch. The cellular response depends on the strength and duration of Myc activity, which in turn is affected by the multiple cofactors and regulatory pathways with which Myc interacts.

Introduction

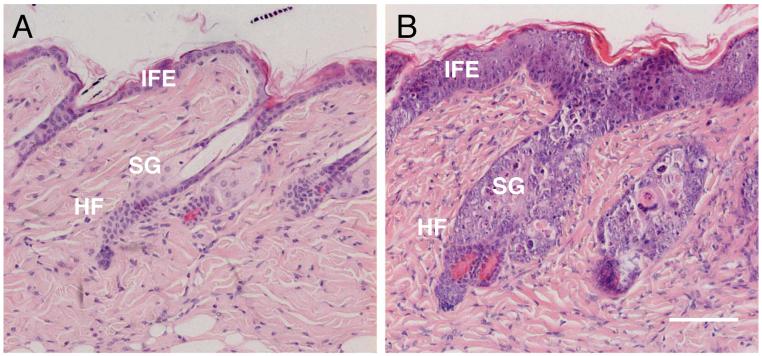

The epidermis constitutes the outer layer of the skin and acts as a protective interface between the body and the environment. Within the epidermis several types of differentiation can be discerned, including formation of the interfollicular epidermis (IFE), hair follicles (HF) and sebaceous glands (SG) (Figure 1A)1. In each of these regions the cells that have completed the process of terminal differentiation are dead cells that are shed from the tissue; they are continually replaced through proliferation of stem cells. There is evidence for the existence of distinct populations of stem cells in the IFE, HF and SG. However, in response to an appropriate stimulus, stem cells in each location can produce daughter cells that differentiate along all the different epidermal lineages2-4.

Figure 1. Effect of Myc activation on murine skin.

H&E stained sections of back skin of K14MycER transgenic mice treated with (A) acetone (control) or (B) 4OHT for 4 days. IFE: interfollicular epidermis; SG: sebaceous gland; HF: hair follicle. (A) shows the normal appearance of the epidermis. (B) shows that activation of Myc results in thickening of the IFE, SG enlargement and HF abnormalities. Scale bar: 100 μm.

While stem cells are ultimately responsible for maintaining the epidermis via combined self-renewal and generation of differentiated progeny, there is evidence that not all dividing cells within the epidermis are stem cells4. One widely accepted model is that the progeny of stem cells that are destined to differentiate undergo a limited number of rounds of division prior to initiation of terminal differentiation. These stem cell progeny are known as transit amplifying cells and can be identified in cultures of human epidermis, because they form small, abortive colonies. Whether transit amplifying cells also exist in vivo has recently been called into question by lineage tracing experiments which demonstrate that mouse IFE is maintained by a single population of cells4.

An understanding of the pathways that regulate epidermal stem cell renewal and differentiation is of considerable importance in cancer research. This is because non-melanoma skin cancer, comprising tumours that arise from epidermal keratinocytes, is the most common type of cancer in the world5 (http://www.cancer.org/docroot/CRI/content/CRI_2_2_1X_How_many_people_get□_no nmelanoma_skin_cancer_51.asp?sitearea=). The two major forms of non-melanoma skin cancer are basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. While mutation of components of the hedgehog pathway is a hallmark of basal cell carcinoma, a wide variety of changes have been observed in squamous cell carcinoma. One of these is Myc amplification, which has been found in 50% of squamous cell carcinomas arising in patients who have undergone long-term immunosuppression following organ transplantation5.

In human interfollicular epidermis, c-Myc protein is predominantly expressed in the basal cell layers, with little detectable immunoreactivity in the terminally differentiating suprabasal layers6. This is consistent with studies of cultured human keratinocytes, which demonstrate downregulation of Myc during suspension induced terminal differentiation7,8. In human hair follicles c-Myc protein is detected in the proliferative zone at the base of the follicle (bulb), the quiescent zone of stem cells in the bulge and in the terminally differentiating matrix cells that lie above the bulb and give rise to the hair fiber6,9. In skin squamous cell carcinomas upregulated expression of Myc is observed throughout the tumour mass10.

Consequences of Myc overexpression in cultured keratinocytes

The effects of Myc on keratinocytes in culture have been studied using a variety of approaches, including knockdown or overexpression in primary human or immortalized mouse cells. One of the tools that has proved very useful is overexpression of MycER, a chimeric protein in which the C-terminus of Myc is fused to the ligand-binding domain of a mutant oestrogen receptor (ER). In cells expressing MycER, Myc is only active when cells are exposed to 4-hydroxy-Tamoxifen (4OHT)11. Thus the timing and duration of activation can be precisely controlled.

Many studies have demonstrated that Myc plays a positive role in keratinocyte proliferation. Epidermal growth factor (EGF), a key keratinocyte mitogen, stimulates Myc expression via increased Myc promoter activity12,13. Reduced proliferation of primary human keratinocytes resulting from overexpression of the EGFR antagonist leucine rich repeats and immunoglobulin like domains containing protein (Lrig1) results in reduced Myc expression13. Furthermore, activation of MycER stimulates DNA synthesis, an effect that is attenuated by overexpression of Lrig113 or knockdown of Myc-induced sun domain containing protein (Misu; also known as NSun2), a Myc target gene encoding an RNA methyltransferase14. Transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) induces keratinocyte growth arrest and this can be blocked by overexpression of Myc12,15. Conversely, knockdown of Myc can inhibit keratinocyte proliferation16.

Flying in the face of these studies is the observation that overexpression of wild type c-Myc or activated MycER via retroviral transduction of primary human keratinocytes stimulates terminal differentiation17. In these experiments stem cells were distinguished from transit amplifying cells on the basis of high β1 integrin expression and high capacity for clonal growth. Myc expression did not completely inhibit proliferation, but over a period of several days there was an increase in the number of cells that expressed low β1 integrin levels and formed abortive colonies of terminally differentiated cells. A marked increase in the proportion of differentiated, involucrin positive, cells was observed 5 days after 4OHT activation of MycER. In normal epidermis involucrin is first expressed in the upper spinous layers; however, in culture expression is initiated during the transition from basal to suprabasal layer17. There was also an increase in the proportion of cells in G2+M of the cell cycle, a feature of keratinocytes undergoing terminal differentiation in culture14,17. When MycER transduced keratinocytes were FACS sorted on the basis of high or low β1 integrin levels and plated at clonal density in the presence or absence of 4OHT, Myc exerted a selective effect in depleting the high β1 (putative stem cell) population.

While at first sight the findings of Gandarillas and Watt17 contradict the studies in which Myc stimulates keratinocyte proliferation, it is important to consider the context and time over which keratinocytes have been observed. Different levels of Myc overexpression may result in different outcomes, and there are striking differences in the time course of the assays used to examine proliferation. The growth curves showing reduction of proliferation have an end-point of 25 days17, while stimulation of proliferation is observed over a shorter period14. Furthermore, epidermal reconstitution experiments using Myc activation in keratinocytes cultured at the air-liquid interface on a dermal substrate show consistent results in terms of the effect of Myc on keratinocyte differentiation. Myc induces premature differentiation, as evidenced by increased numbers of cells initiating terminal differentiation in the basal layer, disorganization of the basal layer and abnormal accumulation of cells in the final stages of terminal differentiation14,17,18.

One further aspect of the effects of Myc on keratinocytes in culture is that keratinocytes are highly resistant to Myc-induced apoptosis17,19, although it can be induced in differentiating suprabasal keratinocytes cultured in medium containing a low serum concentration21. This may reflect the fact that there are many similarities between apoptosis and epidermal terminal differentiation, albeit that apoptosis is executed in a matter of hours, whereas terminal differentiation takes place of a period of weeks. Similarities include the induction of transglutaminase, regulation by extracellular matrix and loss of the cell nucleus19.

In attempting to reconcile the findings that Myc can stimulate both proliferation and terminal differentiation, it has been proposed that Myc induced differentiation is a fail-safe device that protects keratinocytes from uncontrolled proliferation (Figure 2)13. The model is that, in vivo, stem cells are frequently in a quiescent, nondividing state4. Downregulation of the stem cell marker Lrig1 is one mechanism by which stem cells can be stimulated to divide, as a result of increased EGFR signalling, extracellular signal regulated kinase (Erk)-mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) activation and Myc expression. Myc induced terminal differentiation would serve to protect the epidermis from the potentially oncogenic effects of sustained Myc activation.

Figure 2. Concept of Myc induced terminal differentiation as a fail-safe mechanism to prevent uncontrolled proliferation of epidermal stem cells.

Stem cells are often in a quiescent (nondividing state). Activation of Myc leads to stem cell proliferation. Sustained or high level Myc activation stimulates proliferating stem cells to enter the transit amplifying compartment and thereby initiate terminal differentiation.

Modulating Myc activity in the epidermis in vivo

While studies of cultured keratinocytes have been valuable in elucidating the pathways that regulate epidermal self-renewal and differentiation, they do have a number of limitations. The first of these is that true homeostasis, that is, a balance between self-renewal and terminal differentiation, cannot be maintained in culture. Secondly, at present it is only possible to examine differentiation along a single lineage, that of the interfollicular epidermis. Finally, it is not possible in culture to examine the complex and dynamic interplay between keratinocytes and other cell types within the skin.

To examine the effects of Myc on the epidermis in vivo several different mouse models have been generated (Table 1). Different promoters have been used to target different subpopulations of keratinocytes, namely basal (which includes the stem cell compartment of IFE, SG and HF) and suprabasal (terminally differentiating) keratinocytes. Both Myc and MycER have been overexpressed and, in addition, the effects of targeted deletion of Myc or the co-repressor Miz-1, which contributes to Myc-dependent repression of gene expression20, have been examined.

Table 1. Summary of mouse models for the study of Myc function in the epidermis.

The transgene expressed or gene deleted is shown, together with the promoter used, target cells within the epidermis and resulting phenotype. IFE: interfollicular epidermis; SG: sebaceous gland

| Transgene or knockout | Promoter | Target cells | Phenotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myc | Loricrin | Basal and differentiating | Epidermal hyperproliferation, hyperkeratosis, reduced sensitivity to UV-B induced apoptosis | Waikel et al., 1999 |

| MycER | Involucrin | Differentiating | Reversible tumour formation | Pelengaris et al., 1999 |

| MycER | K14 | Basal | IFE and SG differentiation | Arnold and Watt, 2001 |

| Myc | K14 | Basal | Stem cell depletion | Waikel et al., 2001 |

| Myc | K5 | Basal | Epidermal hyperproliferation | Russell et al., 2001 |

| c-Myc knockout | K5Cre | Basal | Epidermal thinning, impaired wound healing | Zanet et al., 2005 |

| c-Myc knockout | K5CreER | Basal | Dispensable for epidermal homeostasis | Oskarsson et al., 2006 |

| Miz-1 knockout | K14Cre | Basal | Disturbed hair follicle differentiation, IFE thickening | Gebhardt et al., 2007 |

One of the first transgenic models of Myc overexpression in the epidermis involved targeting MycER to the suprabasal, postmitotic cell layers via the involucrin promoter (Inv)21. This perturbs the differentiation programme, triggers differentiated cells to divide and leads to the development of benign tumours resembling papillomas or pre-malignant lesions that resemble actinic keratosis. The phenotype is entirely reversible on withdrawal of 4OHT. Part of the phenotype is due to increased vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) production by transgene-positive keratinocytes, resulting in stimulation of angiogenesis21,22. Telomerase activation is required to elicit the full hyperplastic response, as the skin lesions induced by InvMycER activation are less severe in telomerase deficient than in wild type mice23. The Myc induced lesions do not convert into malignant tumours because keratinocytes expressing the transgene are still capable of undergoing terminal differentiation, albeit with abnormal retention of nuclei in the cornified cells21,24. Other effects of prolonged activation of MycER expressed under the control of the involucrin promoter are deregulation of the hair follicle growth cycle and sebaceous gland enlargement25.

Myc has also been overexpressed in vivo under the control of a fragment of the loricrin promoter that is functional in proliferating and suprabasal keratinocytes26. Loricrin driven overexpression of Myc induces epidermal thickening (hyperplasia) and accumulation of the anucleate, cornified cells at the final stage of terminal differentiation (hyperkeratosis). As in mice expressing Myc under the control of the involucrin promoter, suprabasal cells are recruited back into the cell cycle. A further finding is that the mice are resistant to UVB induced apoptosis in the skin.

Using the keratin 14 promoter to target the basal layer, constitutive overexpression of wild type Myc or inducible MycER expression has been studied27,28. Adult mice in which Myc is constitutively expressed gradually lose their hair and develop spontaneous wounds; this is associated with reduced expression of β1 integrins28.

4OHT treatment of K14MycER mice causes progressive and irreversible changes in adult epidermis. Proliferation is stimulated and there is an increase in the number of differentiated cell layers in the IFE, reflecting increased numbers of spinous, granular and cornified layers (Figure 1B). Sebaceous gland differentiation is increased, both within the hair follicles (Figure 1B) and in the interfollicular epidermis and wound healing is impaired27,29-31. One technique that is used to identify quiescent stem cells is to look for cells that, having incorporated a DNA label such as BrdU soon after birth, retain that label in the adult tissue4. Whereas activation of Myc leads to depletion of label retaining cells in the IFE, as a consequence of cell division28, it does not deplete them in the bulge, at least at the time points examined30.

In K14MycER mice activation of c-Myc by a single application of 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen is as effective as continuous treatment in stimulating proliferation and differentiation along the epidermal and sebaceous lineages27. This is in contrast to the effects of activating Myc in the suprabasal epidermal layers, where the phenotype is completely reversed on cessation of 4OHT treatment21. The observation that transient activation of Myc in the basal layer has long-term effects on the epidermis is consistent with the hypothesis that it triggers irreversible exit from the stem cell compartment.

Constitutive expression of Myc under the control of the keratin 5 promoter, which targets essentially the same basal layer cells as the keratin 14 promoter, also results in increased proliferation and thickness of the interfollicular epidermis32. Apoptosis is reported to be increased in this model; however, the apoptotic markers evaluated, TUNEL staining and caspase activation, are also markers of cells undergoing terminal differentiation and there is general agreement that keratinocytes are highly resistant to Myc induced apoptosis19,33.

One important difference between the K14MycER and the K5Myc mice is that the K5Myc mice develop spontaneous tumours in the skin and oral epithelium32. The time of onset tumour development ranges from 20 to 60 weeks. K14MycER mice have not been examined at such late time points after Myc activation and so it is unclear whether tumour development represents a discrepancy between the models, or whether it is a matter of timing. A further possibility is that acute Myc activation stimulates differentiation while chronic activation triggers tumour formation.

Conditional deletion of Miz1 via expression of K14Cre recombinase results in changes in the hair growth cycle, hair pigmentation and altered hair follicle structure34. Miz1 is a zinc-finger transcription factor, which binds Myc and a number of additional proteins, including Bcl-6, the topoisomerase II binding protein TopBP1, the ubiquitin ligase HectH9, and Smad protein complexes34. The mice also have areas of suprabasal proliferation in the interfollicular epidermis, particularly where the hair follicle and IFE become continuous. The consequences of Miz1 deletion therefore bear some similarities to Myc overexpression, in particular the increase in proliferation and complex effects on terminal differentiation.

So far there have been two reports of c-Myc deletion in the epidermis (Table 1). In one, epidermal deletion of Myc via K5Cre results in impaired wound healing, thinning of the interfollicular epidermis and premature differentiation. Stem cell self-renewal is also impaired, as measured by a reduction in the number of DNA label retaining cells35. The K5 and K14 promoters are active from mid-gestation and thus some of the effects may be attributable to effects of Myc prior to birth. In the second study Myc was selectively deleted in adult epidermis via 4OHT activation of K5CreER36. In this situation there are no abnormalities in the IFE, HF and SG; and there are no changes in proliferation or expression of differentiation markers. However, the mice are resistant to Ras-induced carcinogenesis as a result of upregulation of cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor p21 (Cip1)36. The resistance to tumour formation on deletion of Myc is consistent with the spontaneous tumour development in K5Myc mice32.

What remains to be discovered is whether loss of c-Myc is to some extent compensated for by expression of other Myc genes. N-Myc, in particular, is known to be expressed in the epidermis and drives proliferation in response to Sonic hedgehog37,38.

From this survey of the various mouse models a number of conclusions can be drawn. The effect of overexpressing Myc depends on the cell layer in which Myc is expressed. Nevertheless, wherever Myc is activated there is increased proliferation, which may reflect recruitment of quiescent stem cells into cycle or increased rounds of division within the transit amplifying cell compartment (Figure 2, 3), and disturbed differentiation. The effects of Myc are reversible in differentiated cells but not in the basal layer. Finally, there is a link with tumour formation in some but not all models.

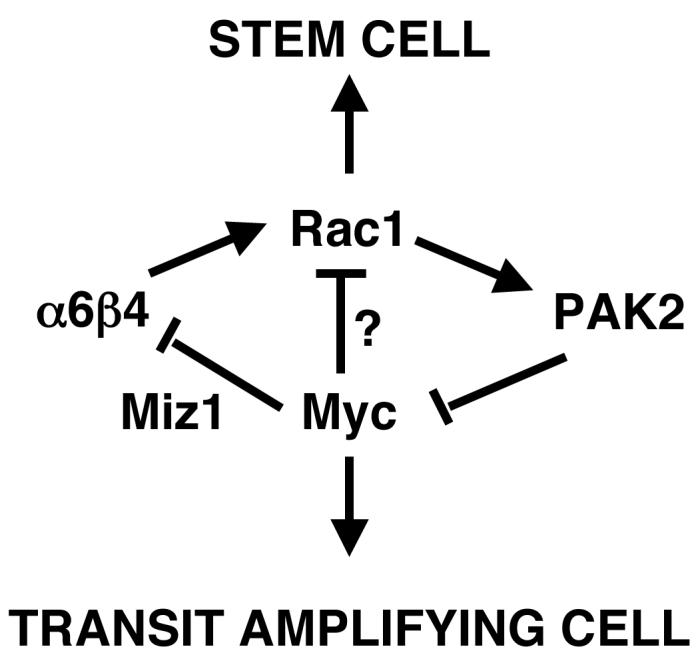

Figure 3. Summary of the different effects of Myc on the epidermal stem cell compartment.

In upper part of Figure red arrows denote events stimulated by Myc: exit from the stem cell compartment, transit amplifying cell proliferation and terminal differentiation along the sebocyte and interfollicular epidermal lineages. Myc antagonism by Rac/PAK240 and Lrig113 is shown in blue and results in inhibition of stem cell proliferation (via Lrig1) and inhibition of both proliferation and terminal differentiation (via Rac/PAK2). SC: stem cell; TA: transit amplifying cell; IFE: interfollicular epidermis; SG: sebaceous gland; HF: hair follicle. The lower part of the Figure illustrates the transcription complexes involved in stimulating Misu/NSun2 expression14 and repressing expression of cell adhesion and cytoskeleton genes18. Myc mediated inhibition of cell adhesion is dependent on repression of gene expression via complex formation with Miz1. In contrast, expression of Misu, which is required for Myc induced stimulation of proliferation, is positively regulated by Myc.

Interpreting Myc using microarrays

One interpretation of the K14MycER and K14Myc phenotypes27-29 is that when Myc is activated in epidermal stem cells proliferation is stimulated as cells exit the stem cell compartment and undergo differentiation along the lineages of the interfollicular epidermis and sebaceous glands (Figure 3)27. In order to investigate the mechanisms by which Myc exerts these effects microarray analysis has been performed on RNA isolated from the skin of K14MycER and control mice treated with 4OHT for 0, 1 or 4 days31.

Misu and cell proliferation

The majority of up-regulated genes in the dataset are involved in cell growth and proliferation, as would be expected from the increased proliferation of epidermis in which Myc is activated and in agreement with microarray data on the effects of Myc in a range of cell types31. One of the upregulated genes is Misu, which shows expression in all tissues analysed so far14. In normal epidermis Misu expression is restricted to a subpopulation of cells in the SG and to the proliferative cells at the base of growing hair follicles. On activation of Myc in K14MycER transgenic mice, Misu is upregulated in all cell compartments within the epidermis.

Misu is localised to the nucleolus in G1 cells and knockdown of Misu blocks Myc-induced nucleolar enlargement. Misu expression is upregulated and detected throughout the nucleus in S phase cells; in G2 it is found in a punctate distribution within the cytoplasm; and at mitosis it decorates the spindle. This dynamic redistribution during the cell cycle may hint at additional functions for Misu.

Knockdown of Misu has no effect on keratinocytes that are proliferating at a low rate in reconstituted epidermis. However, Misu is required for Myc induced keratinocyte proliferation in culture (Figure 3). In addition, knockdown of Misu reduces the volume of tumours formed by human squamous cell carcinoma cells in nude mice. Misu is upregulated in a range of human tumours and is a potential therapeutic target in cancers with high Myc activity14.

Decreased cell adhesion

40% of the genes that are downregulated on activation of Myc in the skin of K14MycER transgenic mice encode cell adhesion and cytoskeleton proteins31. These include components of the actomyosin cytoskeleton and α6β4 integrin, the laminin receptor that localizes to hemidesmosomes, which anchor basal keratinocytes to the underlying basement membrane (Figure 4). In striking validation of the microarray results, there is a marked reduction both in the number and size of hemidesmosomes in 4OHT treated K14MycER epidermis (Figure 4)31.

Figure 4. Reduction in epidermal hemidesmosome number and size on activation of Myc.

Transmission electron microscopy of the epidermal basement membrane zone of K14MycER transgenic (tg) and wild-type (WT) mice treated for 9 days with 4OHT. Arrows in WT panels indicate hemidesmosomes. The number and size of hemidesmosomes is reduced in transgenic epidermis (arrows). Scale bars: 200 nm (top 3 panels), 1 μm (bottom panel). Reproduced from reference 31 with permission from the Company of Biologists.

By downregulating expression of genes involved in cell adhesion Myc activation inhibits cell-extracellular matrix adhesion, cell spreading and cell motility in cultured keratinocytes and impairs epidermal wound healing in vivo28,31. In agreement with these observations, cultured keratinocytes in which Myc has been deleted are more migratory than wild type primary mouse keratinocytes35. When K14MycER mice are crossed with mice overexpressing the β1 integrin subunit under the control of the K14 promoter, in order to partially rescue the reduced extracellular matrix adhesiveness resulting from Myc activation, proliferation is still increased and the SG still enlarge; however, there is normalisation of the basal layer and rescue of the Myc induced premature onset of IFE terminal differentiation18.

Keratinocyte differentiation is known to be regulated by extracellular matrix adhesion, with reduced integrin-mediated adhesion being a positive terminal differentiation stimulus39,40. Myc-mediated downregulation of cell adhesion genes therefore provides an explanation for why Myc can stimulate keratinocyte differentiation. There is the direct effect of causing cells to detach from the basement membrane and the indirect effect of preventing cells from moving to a location where they would normally receive hair differentiation stimuli. We therefore hypothesize that Myc stimulates exit from the stem cell compartment by reducing adhesive interactions with the local microenvironment or niche.

How does Myc negatively regulate cell adhesion genes? One important mechanism involves Myc binding to Miz1 (Figure 3)18. Miz1 is a transcription factor that negatively regulates cell proliferation via p15 and p21, and positively regulates cell adhesion20,41. Cell adhesion and cytoskeleton genes that are downregulated in keratinocytes expressing wild type Myc are not downregulated in cells expressing Myc mutant that cannot bind to Miz1 (MycV394D)18. Primary human keratinocytes that express the MycVD mutant still show increased proliferation but their adhesive properties are not decreased and the premature onset of terminal differentiation associated with Myc activation does not occur18. MycVD expressing keratinocytes show enhanced expression of several adhesion factors, such as integrins α6 and β1, and chromatin immunoprecipitation assays have indicated that there is a direct binding of Miz1 to the promoters of these genes18.

A second pathway through which Myc is implicated in epidermal stem cell adhesion is via interaction with PAK2, an effector of the small GTPase Rac1 (Figure 5)40,42. Conditional deletion of Rac1 in mouse epidermis has yielded varying degrees of perturbation of epidermal homeostasis, ranging from massive and widespread depletion of stem cells to milder effects that are selective for the IFE or hair follicles40,43-45. Deletion of Rac1 leads to transient activation of Myc, suggesting that Rac1 may negatively regulate Myc. Downstream of Rac1, PAK2 can directly phosphorylate Myc, preventing E-box binding and heterodimerisation with its partner protein Max40,42. Expression of Rac1 in primary human keratinocytes can overcome the decrease in clonal growth and stimulation of terminal differentiation induced by Myc activation. A Myc mutant that cannot be phosphorylated by PAK2 is insensitive to Rac1 downregulation, and a mutant that mimics constitutive phosphorylation does not induce terminal differentiation40. Thus, PAK2 mediated phosphorylation of Myc prevents Myc-induced downregulation of extracellular matrix adhesion factors that allow exit from the stem cell niche. The interplay between Rac1 and Myc in epidermal stem and transit amplifying cells is illustrated schematically in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Schematic summary of the interplay between Rac1 and Myc in regulating the epidermal stem and transit amplifying cell compartments.

Rac1 is required to maintain the stem cell compartment40, while Myc stimulates stem cells to become transit amplifying cells17,26,27. There is evidence for mutual antagonism between the effects of Rac1 and Myc: Rac1 negatively regulates Myc via PAK2 phosphorylation40; Myc decreases expression of the α6β4 integrin via a Miz1-dependent mechanism18; and α6β4 can activate Rac173.

A further situation in which Myc is negatively regulated by a kinase involved in the control of actin cytoskeleton organisation is expression of the serine-threonine-specific kinase, LIMK18. Inhibition of Myc by LIMK1 is via inhibition of Stat3 phosphorylation. Constitutive activation of cofilin or inhibition of Rho kinase results in Stat3 phosphorylation and increased Myc levels. In the hyperproliferative lesions characteristic of psoriasis, there is down-regulation of LIMK1 and upregulation of Myc in the suprabasal epidermal layers8.

The ability of Myc to decrease expression of genes that encode proteins mediating cell adhesion and cytoskeletal assembly is observed in many cell types46, but the consequences are context dependent. In the epidermis reduced cell adhesion acts as a terminal differentiation stimulus39, while in the mammary gland Myc-dependent downregulation of E-cadherin stimulates invasion47. Myc-induced differentiation of human embryonic stem (ES) cells occurs via integrin downregulation48 and Myc induces haematopoietic stem cells to exit their niche by downregulation of adhesion factors such as α6 and N-cadherin49.

Myc induced chromatin modifications

In addition to activating or repressing expression of specific genes, Myc has a range of effects on chromatin and basal transcription. Myc influences global chromatin structure47,50,51 and is required for the maintenance of active chromatin52 (Figure 6A). It is therefore of interest to investigate whether epidermal stem cells can be distinguished on the basis of global histone modifications and whether these are altered by activation of Myc53.

Figure 6. Chromatin modification by Myc.

(A) Contribution of Myc to formation of condensed, silent chromatin (left hand box) and open, active chromatin (right hand box)52,74,75. MTase: methyltransferase; HDAC: histone deacetylase; HAT: histone acetyl transferase. Histones are shown as trimethylated (Me) in silent chromatin and acetylation (Ac) in active chromatin. (B) Changes in histone methylation during the transition from stem (SC) to transit amplifying (TA) to terminally differentiation (TD) epidermal cell54. Levels of tri- (Me3), di- (Me2) and mono- (Me1) methylated histones are shown.

By labelling human and mouse epidermis with antibodies to different histone modifications we found that compared to other cells in the basal layer of the epidermis, quiescent, nondividing, stem cells have high levels of tri-methylated histone H3 at lysine 9 and H4 at lysine 20, hypoacteylation of histone H4 and lack mono-methylation of histone H4 at lysine 20 (Figure 6B). This signature indicates that the majority of the chromatin in quiescent epidermal stem cells is silenced. Activation of Myc by 4OHT treatment of K14MycER mice results in profound changes in these histone modifications. Histone H4 acetylation is increased and there is a transient increase in mono-methylation at lysine 20, indicating that activation of Myc induces histone modifications in epidermal stem cells that are associated with active chromatin (Figure 6B). One mechanism by which Myc directly induces an active chromatin state is by negatively regulating H3K4 trimethylation dependent de-methylases54.

As IFE cells undergo terminal differentiation, mono-methylation of histone H4 at lysine 20 is replaced by di-methylation at histone H3 lysine 9 and histone H4 lysine 20, changes that are features of chromatin silencing53. Thus, surprisingly, stem cells and terminally differentiated cells have characteristics of silent heterochromatin, while transit amplifying cells have their chromatin in a more active state53.

Are Myc induced chromatin modifications contributing to the stimulation of terminal differentiation? The Myc-induced switch from mono- to di-methylated H4K20 in epidermis is blocked by the HDAC inhibitor trichostatin A (TSA). TSA treatment of wild type epidermis induces a strikingly similar phenotype to activation of Myc, characterised by increased proliferation, detachment of basal cells from the basement membrane and stimulation of IFE and SG differentiation53. When K14MycER mice are treated with 4OHT and TSA the epidermal phenotype is even more severe than with either treatment alone. These results suggest that Myc-induced chromatin modifications play a major role in Myc-induced exit from the stem cell compartment and subsequent differentiation53. However, one caveat is that the effects of TSA on cultured epidermal cells are somewhat different and do not correlate with the amount of acetylated/deacetylated histones on the promoters of the differentiation-associated genes55.

We conclude that the nuclei of quiescent epidermal stem cells are enriched for chromatin modifications that are largely associated with gene silencing but when Myc is activated, chromatin modifications are induced that correlate with active gene transcription. One possible explanation would be that Myc facilitates an open chromatin state that is permissive for global transcription factor binding. This would explain why Myc can contribute to induction of pluripotency in adult somatic stem cells, even though it is not obligatory for this process56-58.

Intersection of Myc with other regulatory molecules

So far we have focused on the downstream effects of Myc activation. However, it is clear that Myc is itself regulated, both negatively and positively, by a number of other transcription factors. Two negative regulators, Ovol1 and Blimp-1, and one positive regulator, β-catenin, profoundly influence the behaviour of epidermal cells.

Ovol1 is the mammalian homologue of the Drosophila ovo gene, which plays a role in patterning the larval cuticle. Ovol1 is a zinc finger containing transcription factor that binds to the c-myc promoter and represses transcription59,60. Ovol1 is expressed in the suprabasal differentiating cells of the IFE and hair follicle59 and on deletion of Ovol1 c-Myc is up-regulated in the suprabasal epidermal layers60. Ovol1−/− embryonic epidermis is characterised by increased proliferation60. In adult epidermis there is largely normal expression of terminal differentiation markers in the interfollicular epidermis and hair follicle, but the hair shafts develop abnormal kinks and splits59. Ovol1 is induced in response to TGFβ signalling and is a FOXO-dependent TGFβ response gene61. Consistent with this, Ovol1−/− keratinocytes in culture exhibit impaired growth arrest in response to TGFβ60.

B lymphocyte induced maturation protein 1 (Blimp-1) is a key transcriptional regulator of B and T lymphocyte differentiation62 and, like Ovol1, binds to and negatively regulates the Myc promoter63,64. Blimp1 is expressed in the differentiating cells of the IFE, HF and SG64 and also in a population of unipotent SG progenitor cells63. Blimp1 null epidermis is characterised by increased Myc expression, increased proliferation, and SG enlargement63,64. Thus, the downregulation of Myc that occurs during epidermal terminal differentiation correlates with upregulation of two transcriptional repressors of Myc, ovol-1 and Blimp-1.

While the effects of Blimp-1 and Ovol1in the epidermis have only recently been described, β-catenin is well known to play a key role in epidermal stem cell renewal and lineage selection1,3. Myc is a β-catenin target gene that mediates proliferation in response to Wnt activation in intestinal epithelium65. However, in the epidermis the populations that proliferate in response to Myc and β-catenin are different. β-catenin stimulates proliferation of cells at the base of growing hair follicles and causes local increases in proliferation at sites of ectopic hair follicle formation38, whereas Myc stimulates proliferation primarily in the interfollicular epidermis and sebaceous gland30. In addition, the effects on epidermal lineage selection are quite different, with Myc promoting differentiation into IFE and sebaceous gland (Figure 3) and β-catenin stimulating ectopic hair follicle formation38. Even more striking is that overexpression of an N-terminally truncated form of Lef1, which blocks β-catenin signalling, stimulates SG and IFE differentiation66,67, thereby resembling Myc.

The reasons why activating Myc and blocking β-catenin via expression of ΔNLef1 produce similar results have yet to emerge. However, there are several observations that hint at complexity in the interaction between Myc and β-catenin. One is that plakoglobin, which like β-catenin is an Armadillo containing protein involved both in cell-cell adhesion and nuclear signalling, suppresses c-Myc expression in the skin68. Another is that the DNA helicases Pontin and Reptin physically interact with c-Myc and are antagonistic regulators of Wnt signalling69. The effects of overexpressing these proteins in Xenopus embryos are similar to the effects of overexpressing Myc and embryonic lethality resulting from knockdown of Pontin or Reptin can be rescued by overexpressing Myc. They exert their mitogenic effect through the c-Myc-Miz-1 pathway70.

The identification of factors that negatively regulate Myc in specific cells of the epidermis serves to illustrate the complexity of Myc function in the epidermis and provides a possible explanation for why Myc expression has different effects in different cell types.

Myc: dose, timing and context

When is an oncogene not an oncogene? When it stimulates cells to differentiate. Studies of Myc function in the epidermis have revealed some of the ways in which Myc can stimulate differentiation but more remain to be discovered. Just as epidermal cells respond differently to different levels of β-catenin activation38, it is likely that the level and duration of Myc activation within the epidermis will have different effects. A further consideration is that the repertoire of Myc binding partners varies between cells; this may explain, for example, why the artificial Myc repressor, Omomyc, which competes with Max for binding to Myc, but does not block Myc dependent repression of gene expression, inhibits Myc-induced epidermal tumour formation while potentiating Myc dependent apoptosis33. Studies in Drosophila have revealed that cells expressing different levels of Myc communicate with one another by releasing soluble factors71, suggesting a cooperative mechanism that could contribute to growth regulation within the epidermis and other tissues. It will be clearly be of great interest to examine how these issues impact on Myc function in the epidermis.

For now, it seems reasonable to conclude that within the epidermis Myc can act both as an agent that promotes differentiation of stem cells27,28 and as an oncogene21,32. Squamous cell carcinomas are characterised by multiple genetic and epigenetic changes5. We favour the idea that within a malignant epidermal cell the ability of Myc to promote differentiation may be abrogated by some of those changes. A specific example is that if a tumour has acquired an activating integrin mutation72 some of the inhibitory effects of Myc on cell adhesion may be prevented, thereby over-riding the ‘fail-safe’ differentiation response. A better understanding of these issues will lead to new approaches to targeting Myc in squamous cell carcinoma.

References

- 1.Fuchs E. Scratching the surface of skin development. Nature. 2007;445:834–842. doi: 10.1038/nature05659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Owens DM, Watt FM. Contribution of stem cells and differentiated cells to epidermal tumours. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2003;3:444–451. doi: 10.1038/nrc1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watt FM, Lo Celso C, Silva-Vargas V. Epidermal stem cells: an update. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2006;16:518–524. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones PH, Simons BD, Watt FM. Sic transit Gloria. Farewell to the epidermal transit amplifying cell? Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:371–381. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boukamp P. Non-melanoma skin cancer: what drives tumor development and progression? Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:1657–1667. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bull JJ, Muller-Rover S, Patel SV, Chronnell CM, McKay IA, Philpott MP. Contrasting localization of c-Myc with other Myc superfamily transcription factors in the human hair follicle and during the hair growth cycle. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2001;116:617–622. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2001.12771234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gandarillas A, Watt FM. Changes in expression of members of the fos and jun families and myc network during terminal differentiation of human keratinocytes. Oncogene. 1995;11:1403–1407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Honma M, Benitah SA, Watt FM. Role of LIM kinases in normal and psoriatic human epidermis. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2006;17:1888–1896. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-12-1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barajon I, Rumio C, Donetti E, Imberti A, Brivio M, Castano P. Pattern of expression of c-Myc, Max and Bin1 in human anagen hair follicles. Br. J. Dermatol. 2001;144:1193–1203. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garte SJ. The c-myc oncogene in tumor progression. Crit. Rev. Oncog. 1993;4:435–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Littlewood TD, Hancock DC, Danielian PS, Parker MG, Evan GI. A modified oestrogen receptor ligand-binding domain as an improved switch for the regulation of heterologous proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:1686–1690. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.10.1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coffey RJ, Jr., Bascom CC, Sipes NJ, Graves-Deal R, Weissman BE, Moses HL. Selective inhibition of growth-related gene expression in murine keratinocytes by transforming growth factor beta. Mol. Cell Biol. 1988;8:3088–3093. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.8.3088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jensen KB, Watt FM. Single-cell expression profiling of human epidermal stem and transit-amplifying cells: Lrig1 is a regulator of stem cell quiescence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 103:11958–11963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601886103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knockdown of the EGF receptor antagonist Lrig1 stimulates epidermal cell proliferation and increases c-Myc expression.

- 14.Frye M, Watt FM. The RNA methyltransferase Misu (NSun2) mediates Myc-induced proliferation and is upregulated in tumors. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:971–981. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misu is a Myc target gene that is required for Myc-induced proliferation of epidermal cells and is a potential therapeutic target in squamous cell carcinomas.

- 15.Alexandrow MG, Kawabata M, Aakre M, Moses HL. Overexpression of the c-Myc oncoprotein blocks the growth-inhibitory response but is required for the mitogenic effects of transforming growth factor β1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:3239–3243. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hashiro M, Matsumoto K, Okumura H, Hashimoto K, Yoshikawa K. Growth inhibition of human keratinocytes by antisense c-Myc oligomer is not coupled to induction of differentiation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 1991;174:287–292. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)90518-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gandarillas A, Watt FM. c-Myc promotes differentiation of human epidermal stem cells. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2869–2882. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.21.2869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gebhardt A, Frye M, Herold S, Benitah SA, Braun K, Samans B, Watt FM, Elsasser HP, Eilers M. Myc regulates keratinocyte adhesion and differentiation via complex formation with Miz1. J. Cell Biol. 2006;172:139–149. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200506057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- In contrast to wild type Myc, a mutant that cannot bind Miz1 is unable to decrease epidermal cell adhesion.

- 19.Gandarillas A, Goldsmith LA, Gschmeissner S, Leigh IM, Watt FM. Evidence that apoptosis and terminal differentiation of epidermal keratinocytes are distinct processes. Exp. Dermatol. 1999;8:71–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.1999.tb00350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wanzel M, Herold S, Eilers M. Transcriptional repression by Myc. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:146–150. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(03)00003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pelengaris S, Littlewood T, Khan M, Elia G, Evan G. Reversible activation of c-Myc in skin: induction of a complex neoplastic phenotype by a single oncogenic lesion. Mol. Cell. 1999;3:565–577. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80350-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knies-Bamforth UE, Fox SB, Poulsom R, Evan GI, Harris AL. c-Myc interacts with hypoxia to induce angiogenesis in vivo by a vascular endothelial growth factor-dependent mechanism. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6563–6567. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flores I, Evan G, Blasco MA. Genetic analysis of myc and telomerase interactions in vivo. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;26:6130–6138. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00543-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myc activates telomerase in the epidermis and telomerase is required for the full phenotype of mice in which Myc is expressed under the control of the involucrin promoter.

- 24.Flores I, Murphy DJ, Swigart LB, Knies U, Evan GI. Defining the temporal requirements for Myc in the progression and maintenance of skin neoplasia. Oncogene. 2004;23:5923–5930. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bull JJ, Pelengaris S, Hendrix S, Chronnell CM, Khan M, Philpott MP. Ectopic expression of c-Myc in the skin affects the hair growth cycle and causes an enlargement of the sebaceous gland. Br. J. Dermatol. 2005;152:1125–1123. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waikel RL, Wang XJ, Roop DR. Targeted expression of c-Myc in the epidermis alters normal proliferation, differentiation and UV-B induced apoptosis. Oncogene. 1999;18:4870–4878. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arnold I, Watt FM. c-Myc activation in transgenic mouse epidermis results in mobilization of stem cells and differentiation of their progeny. Curr. Biol. 2001;11:558–568. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00154-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Waikel RL, Kawachi Y, Waikel PA, Wang XJ, Roop DR. Deregulated expression of c-Myc depletes epidermal stem cells. Nat. Genet. 2001;28:165–168. doi: 10.1038/88889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koster MI, Huntzinger KA, Roop DR. Epidermal differentiation: transgenic/knockout mouse models reveal genes involved in stem cell fate decisions and commitment to differentiation. J. Investig. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 2002;7:41–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.19639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braun KM, Niemann C, Jensen UB, Sundberg JP, Silva-Vargas V, Watt FM. Manipulation of stem cell proliferation and lineage commitment: visualisation of label-retaining cells in wholemounts of mouse epidermis. Development. 2003;130:5241–5255. doi: 10.1242/dev.00703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frye M, Gardner C, Li ER, Arnold I, Watt FM. Evidence that Myc activation depletes the epidermal stem cell compartment by modulating adhesive interactions with the local microenvironment. Development. 2003;130:2793–2780. doi: 10.1242/dev.00462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rounbehler RJ, Schneider-Broussard R, Conti CJ, Johnson DG. Myc lacks E2F1’s ability to suppress skin carcinogenesis. Oncogene. 2001;20:5341–5349. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soucek L, Nasi S, Evan GI. Omomyc expression in skin prevents Myc-induced papillomatosis. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:1038–1045. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gebhardt A, Kosan C, Herkert B, Moroy T, Lutz W, Eilers M, Elsasser HP. Miz1 is required for hair follicle structure and hair morphogenesis. J. Cell Sci. 2007;120:2586–2593. doi: 10.1242/jcs.007104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of Miz1 deficient epidermis reveals a role for Miz1 in regulating epidermal proliferation and differentiation, particularly within the hair follicle.

- 35.Zanet J, Pibre S, Jacquet C, Ramirez A, de Alboran IM, Gandarillas A. Endogenous Myc controls mammalian epidermal cell size, hyperproliferation, endoreplication and stem cell amplification. J. Cell Sci. 2005;118:1693–1704. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An epidermal-specific knockout mouse reveals a requirement for c-Myc in epidermal homeostasis.

- 36.Oskarsson T, Essers MA, Dubois N, Offner S, Dubey C, Roger C, Metzger D, Chambon P, Hummler E, Beard P, Trumpp A. Skin epidermis lacking the c-Myc gene is resistant to Ras-driven tumorigenesis but can reacquire sensitivity upon additional loss of the p21Cip1 gene. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2024–2029. doi: 10.1101/gad.381206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- This report suggests that Myc is not required for normal epidermal homeostasis, but is required for tumour formation in response to activated Ras.

- 37.Mill P, Mo R, Hu MC, Dagnino L, Rosenblum ND, Hui CC. Shh controls epithelial proliferation via independent pathways that converge on N-Myc. Dev Cell. 2005;9:293–303. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silva-Vargas V, Lo Celso C, Giangreco A, Ofstad T, Prowse DM, Braun KM, Watt FM. β-catenin and Hedgehog signal strength can specify number and location of hair follicles in adult epidermis without recruitment of bulge stem cells. Dev. Cell. 2005;9:121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Watt FM. Role of integrins in regulating epidermal adhesion, growth and differentiation. EMBO J. 2002;21:3919–3926. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Benitah SA, Frye M, Glogauer M, Watt FM. Stem cell depletion through epidermal deletion of Rac1. Science. 2005;309:933–935. doi: 10.1126/science.1113579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu S, Cetinkaya C, Munoz-Alonso MJ, von der Lehr N, Bahram F, Beuger V, Eilers M, Leon J, Larsson LG. Myc represses differentiation-induced p21CIP1 expression via Miz-1-dependent interaction with the p21 core promoter. Oncogene. 2003;22:351–360. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang Z, Traugh JA, Bishop JM. Negative control of the Myc protein by the stress-responsive kinase Pak2. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;24:1582–1594. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.4.1582-1594.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Benitah SA, Watt FM. Epidermal deletion of Rac1 causes stem cell depletion, irrespective of whether deletion occurs during embryogenesis or adulthood. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2007;127:1555–1557. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chrostek A, Wu X, Quondamatteo F, Hu R, Sanecka A, Niemann C, Langbein L, Haase I, Brakebusch C. Rac1 is crucial for hair follicle integrity but is not essential for maintenance of the epidermis. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;26:6957–6970. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00075-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Castilho RM, Squarize CH, Patel V, Millar SE, Zheng Y, Molinolo A, Gutkind JS. Requirement of Rac1 distinguishes follicular from interfollicular epithelial stem cells. Oncogene. 2007;26:5078–5085. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murphy MJ, Wilson A, Trumpp A. More than just proliferation: Myc function in stem cells. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:128–137. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cowling VH, Cole MD. E-cadherin repression contributes to c-Myc-induced epithelial cell transformation. Oncogene. 2007;26:3582–3586. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sumi T, Tsuneyoshi N, Nakatsuji N, Suemori H. Apoptosis and differentiation of human embryonic stem cells induced by sustained activation of c-Myc. Oncogene. 2007;26:5564–5576. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilson A, Murphy MJ, Oskarsson T, Kaloulis K, Bettess MD, Oser GM, Pasche AC, Knabenhans C, Macdonald HR, trump A. c-Myc controls the balance between hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2747–2763. doi: 10.1101/gad.313104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Amati B, Frank SR, Donjerkovic D, Taubert S. Function of the c-Myc oncoprotein in chromatin remodeling and transcription. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2001;1471:M135–145. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(01)00020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Frank SR, Parisi T, Taubert S, Fernandez P, Fuchs M, Chan HM, Livingston DM, Amati B. MYC recruits the TIP60 histone acetyltransferase complex to chromatin. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:575–580. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Knoepfler PS, Zhang XY, Cheng PF, Gafken PR, McMahon SB, Eisenman RN. Myc influences global chromatin structure. EMBO J. 2006;25:2723–2734. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evidence that Myc proteins are required for the widespread maintenance of active chromatin

- 53.Frye M, Fisher AG, Watt FM. Epidermal stem cells are defined by global histone modifications that are altered by Myc-induced differentiation. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e763. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demonstration that the histone modifications of stem cells differ from those of other cells in the basal layer and evidence that chromatin modifications induced by c-Myc contribute to the effects of Myc on epidermal differentiation.

- 54.Secombe J, Li L, Carlos L, Eisenman RN. The Trithorax group protein Lid is a trimethyl histone H3K4 demethylase required for dMyc-induced cell growth. Genes Dev. 2007;21:537–551. doi: 10.1101/gad.1523007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Markova NG, Karaman-Jurukovska N, Pinkas-Sarafova A, Marekov LN, Simon M. Inhibition of histone deacetylation promotes abnormal epidermal differentiation and specifically suppresses the expression of the late differentiation marker profilaggrin. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2007;127:1126–1139. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wernig M, Meissner A, Foreman R, Brambrink T, Ku M, Hochedlinger K, Bernstein BE, Jaenisch R. In vitro reprogramming of fibroblasts into a pluripotent ES-cell-like state. Nature. 2007;448:318–324. doi: 10.1038/nature05944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nakagawa M, Koyanagi M, Tanabe K, Takahashi K, Ichisaka T, Aoi T, Okita K, Mochiduki Y, Takizawa N, Yamanaka S. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells without Myc from mouse and human fibroblasts. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007 doi: 10.1038/nbt1374. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Although Myc can contribute to the induction of pluripotency in adult cells, it is not obligatory; circumventing the use of Myc reduces tumour formation by reprogrammed cells.

- 59.Dai X, Schonbaum C, Degenstein L, Bai W, Mahowald A, Fuchs E. The ovo gene required for cuticle formation and oogenesis in flies is involved in hair formation and spermatogenesis in mice. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3452–3463. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.21.3452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nair M, Teng A, Bilanchone V, Agrawal A, Li B, Dai X. Ovol1 regulates the growth arrest of embryonic epidermal progenitor cells and represses c-myc transcription. J. Cell Biol. 2006;173:253–264. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200508196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demonstrates a requirement for Ovol1 in TGFβ-induced growth arrest of epidermal cells.

- 61.Gomis RR, Alarcón C, He W, Wang Q, Seoane J, Lash A, Massagué J. A FoxO-Smad synexpression group in human keratinocytes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:12747–12752. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605333103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kallies A, Nutt SL. Terminal differentiation of lymphocytes depends on Blimp-1. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2007;19:156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Horsley V, O’Carroll D, Tooze R, Ohinata Y, Saitou M, Obukhanych T, Nussenzweig M, Tarakhovsky A, Fuchs E. Blimp1 defines a progenitor population that governs cellular input to the sebaceous gland. Cell. 2006;126:597–609. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Identification of unipotent progenitor cells in the sebaceous gland and express the Myc transcriptional repressor Blimp1.

- 64.Magnúsdóttir E, Kalachikov S, Mizukoshi K, Savitsky D, Ishida-Yamamoto A, Panteleyev AA, Calame K. Epidermal terminal differentiation depends on B lymphocyte-induced maturation protein-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2007;104:14988–14993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707323104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Documents the expression of Blimp-1 in differentiated epidermal cells and demonstrates that Blimp-1 is required for the final stages of terminal differentiation in the interfollicular epidermis.

- 65.van de Wetering M, Sancho E, Verweij C, et al. The β-catenin/TCF-4 complex imposes a crypt progenitor phenotype on colorectal cancer cells. Cell. 2002;111:241–250. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Niemann C, Owens DM, Hülsken J, Birchmeier W, Watt FM. Expression of ΔNLef1 in mouse epidermis results in differentiation of hair follicles into squamous epidermal cysts and formation of skin tumours. Development. 2002;129:95–109. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Niemann C, Owens DM, Schettina P, Watt FM. Dual role of inactivating Lef1 mutations in epidermis: tumor promotion and specification of tumor type. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2916–2921. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overexpression of N-terminally truncated Lef1, which cannot bind β-catenin, acts as an epidermal tumour promoter.

- 68.Williamson L, Raess NA, Caldelari R, Zakher A, de Bruin A, Posthaus H, Bolli R, Hunziker T, Suter MM, Müller EJ. Pemphigus vulgaris identifies plakoglobin as key suppressor of c-Myc in the skin. EMBO J. 2006;25:3298–3309. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plakoglobin modulates epidermal homeostasis by suppressing c-Myc.

- 69.Gallant P. Control of transcription by Pontin and Reptin. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:187–192. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Etard C, Gradl D, Kunz M, Wedlich D. Pontin and Reptin regulate cell proliferation in early Xenopus embryos in collaboration with c-Myc and Miz-1. Mech. Dev. 2005;122:545–556. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Senoo-Matsuda N, Johnston LA. Soluble factors mediate competitive and cooperative interactions between cells expressing different levels of Drosophila Myc. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:18543–18548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709021104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- It is proposed that the ability of cells to perceive and respond to local differences in Myc activity contributes to growth regulation in tissues.

- 72.Evans RD, Perkins VC, Henry A, Stephens PE, Robinson MK, Watt FM. A tumor-associated β1 integrin mutation that abrogates epithelial differentiation control. J. Cell Biol. 2003;160:589–596. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200209016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zahir N, Lakins JN, Russell A, Ming W, Chatterjee C, Rozenberg GI, Marinkovich MP, Weaver VM. Autocrine laminin-5 ligates α6β4 integrin and activates RAC and NFκB to mediate anchorage-independent survival of mammary tumors. J. Cell Biol. 2003;163:1397–1407. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brenner C, Deplus R, Didelot C, Loriot A, Viré E, De Smet C, Gutierrez A, Danovi D, Bernard D, Boon T, Pelicci PG, Amati B, Kouzarides T, de Launoit Y, Di Croce L, Fuks F. Myc represses transcription through recruitment of DNA methyltransferase corepressor. EMBO J. 2005;24:336–346. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Satou A, Taira T, Iguchi-Ariga SM, Ariga H. A novel transrepression pathway of c-Myc. Recruitment of a transcriptional corepressor complex to c-Myc by MM-1, a c-Myc-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:46562–46567. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104937200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]