Abstract

Voltage-gated K+ (Kv) channels are important in the regulation of pulmonary vascular function having both physiological and pathophysiological implications. The pulmonary vasculature is essential for reoxygenation of the blood, supplying oxygen for cellular respiration. Mitochondria have been proposed as the major oxygen-sensing organelles in the pulmonary vasculature. Using electrophysiological techniques and immunofluorescence, an interaction of the mitochondria with Kv channels was investigated. Inhibitors, blocking the mitochondrial electron transport chain at different complexes, were shown to have a dual effect on Kv currents in freshly isolated rat pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells (PASMCs). These dual effects comprised an enhancement of Kv current in a negative potential range (manifested as a 5- to 14-mV shift in the Kv activation to more negative membrane voltages) with a decrease in current amplitude at positive potentials. Such effects were most prominent as a result of inhibition of Complex III by antimycin A. Investigation of the mechanism of antimycin A-mediated effects on Kv channel currents (IKv) revealed the presence of a mitochondria-mediated Mg2+ and ATP-dependent regulation of Kv channels in PASMCs, which exists in addition to that currently proposed to be caused by changes in intracellular reactive oxygen species.

Keywords: rat, Kv channel currents, antimycin A, magnesium ions, ATP, Kv channel activation

potassium channels, particularly the voltage-dependent potassium channels (Kv), are inherently involved in the physiological maintenance of the pulmonary vasculature. Prominent roles in the maintenance of resting membrane potential, cell migration, proliferation, and contractility have all been well documented (4, 33, 50, 51). Inhibition of Kv channels is widely accepted to occur in response to low oxygen tension in the pulmonary arteries (3, 30, 36, 52) resulting in depolarization and opening of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels leading to calcium influx and elevated intracellular calcium concentrations.

Oxygen-sensing capability of the mitochondria.

Given that the function of the pulmonary vasculature is for reoxygenation of the blood supply to the systemic circulation, the arteries are exposed to a highly oxygenated environment. Pulmonary arteries are sensitive to changes in the oxygen tension and respond uniquely by contracting in response to periods of low oxygen tension (hypoxia) (1, 26). How changes in oxygen tension are detected and translated into such a functional response remains complex and is presently still not fully determined.

The mitochondria are considered to be prominent oxygen-sensing cellular organelles due to their demand on oxygen to generate ATP as a source of cellular chemical energy. There is evidence suggesting that Kv channels may be regulated by mitochondria-dependent changes in intracellular redox state. With respect to the hypoxia-mediated inhibition of Kv channel currents (IKv) in the pulmonary arteries, a role for reactive oxygen species has been demonstrated. Indeed, both oxidizing (31, 37) and reducing (31, 37, 54) agents have been shown to respectively enhance and inhibit Kv channel currents in the pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells (PASMCs). Inhibition of Kv channels by hypoxia would therefore require the intracellular environment to become reduced during hypoxia. This idea is central to the redox hypothesis (28, 49). Evidence, however, suggests that production of reactive oxygen species by mitochondria might be increased during hypoxia (reviewed in Refs. 47 and 48), thus challenging the main concept of the redox hypothesis. This controversy may indicate that, in addition to changes in cellular redox state, other mitochondria-dependent mechanisms may also be involved in the hypoxic inhibition of the Kv channels in PASMCs. For example, incubation of PASMCs with 2-deoxyglucose, which inhibits mitochondrial function, also inhibits IKv (53, 54). Although the inhibition of the whole cell IKv amplitude in PASMCs by some mitochondrial electron transport chain (mETC) inhibitors and uncouplers has been reported previously (3, 27, 53), the precise mode of their action remains to be elucidated.

We (45) have previously demonstrated a potent interaction of increased intracellular magnesium with Kv channels in the vasculature. Magnesium inhibits Kv channel currents at positive potentials (45). It is possible that dysregulation of the mitochondria [an intracellular store of magnesium (10, 21)] may contribute to an elevated intracellular magnesium concentration. Furthermore, ATP production by mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation may be impeded, resulting in changes in potassium currents as ATP can also interact with Kv channels (12, 32).

This is a comprehensive study of the effects of mitochondrial inhibition on Kv channel currents in isolation from other major K+ conductances and establishes a role for mitochondria-dependent ATP and magnesium regulation in the modulation of IKv in PASMCs. Some of this work has been published in a preliminary form (42).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Basic chemicals were purchased from BDH Merck (U. K.) or Fisher (U. K.). Collagenase (type XI) or collagenase P (used in more recent experiments) was obtained from Sigma or Roche, respectively. Papain and dithiothreitol used for cell isolation were purchased from Sigma (U. K.). The mitochondrial uncoupler CCCP, mETC inhibitors, rotenone, myxothiazol, antimycin A (a mixture of antimycins from Streptomyces species), and sodium cyanide (NaCN) were all obtained from Sigma (U. K.). MagFluo-4-AM and BAPTA-AM were purchased from Invitrogen (U. K.).

Cell isolation and electrophysiology.

Male Wistar rats (225–300 g) were killed by cervical dislocation as approved by the local U.K. Home Office inspector, and small intrapulmonary arteries (3rd–5th order) were microdissected. Isolation of PASMCs [using 1 mg/ml collagenase (type XI), 0.5 mg/ml papain, and 1 mM dithiothreitol and 20-min incubation at 37°C] and electrophysiological recordings were performed as previously described (40, 46). Freshly isolated cells were maintained on ice for use on the same day. Cells were placed in a chamber with a volume of 100–200 μl and continually superfused (∼1 ml/min) with a physiological saline solution (PSS) or a test solution via a five-barrel pipette. Experiments with sodium cyanide were performed using an agar bridge (2% agar filled with 3 M KCl) due to the presence of a diffusion potential between the reference and the pipette Ag-AgCl electrodes of more than 10 mV. This is likely to be due to a formation of water-insoluble silver cyanide on the surface of the reference electrode. PSS contained (mM): 140 NaCl, 4 KCl, 1.5 CaCl2, 1.2 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, and 10 glucose, pH 7.2. Control pipette solution contained (mM): 140 KCl, 0.5 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 EGTA, and 0.5 CaCl2, pH 7.2, and was used for recording unless stated otherwise. Cells were dialyzed with pipette solution for 5 min before recording currents. The effects of inhibitors were recorded a minimum of 5 min after addition to the perfusate. All electrophysiological recordings were performed at room temperature.

IKv was recorded in the presence of 1 μM paxilline and 10 μM glibenclamide to block Ca2+-activated and ATP-sensitive K+ currents, respectively. This allowed analysis of the changes in the voltage-dependent characteristics of IKv in isolation from other potassium conductances as previously described (40). IKv amplitude was measured with a 200-ms voltage step applied from the holding potential of −80 mV to membrane potentials between −100 and +50 mV in 10-mV increments with frequency of 0.1 Hz. Following membrane depolarization, cells were repolarized to −20 mV for 160 ms to measure tail currents, which were used to assess changes in the steady-state activation of IKv.

Tail currents were measured 2–3 ms after the repolarization to −20 mV. To calculate the kinetic parameters of IKv, the I-V curves plotted from tail currents were fitted with the following equation

|

where Va and ka are the half-activation potential and the e-fold steepness of the activation dependency (the slope factor of activation), respectively. Differences in the voltage dependence of IKv activation were assessed by comparison of the changes in half-activation potentials between control and test conditions. IKv block was calculated as a percentage of the current measured at the end of 200-ms depolarization to +50 mV in control conditions from the same cell. Cell membrane capacitance was measured using a 10 mV hyperpolarizing step and used to correct IKv currents for cell size. Therefore, currents were expressed as current density (pA/pF).

Confocal imaging of [Mg2+]i in single PASMCs.

Changes in free [Mg2+]i in single PASMCs were measured using a membrane-permeable fluorescent indicator MagFluo-4-AM and an Olympus FV300-SU laser scanning confocal microscope. A drop of cell suspension was placed on a glass coverslip and loaded with 5 μM MagFluo-4-AM for 45–60 min in the dark at room temperature. The loading solution also contained 50 μM BAPTA-AM to suppress possible changes in MagFluo-4 fluorescence due to increases in [Ca2+]i. After loading, PASMCs were continually superfused with PSS (2 ml/min) for 10–30 min to allow deesterification of both agents. Integral MagFluo-4 fluorescence was measured by using excitation and emission wave lengths of 488 and 505 nm, respectively. Images (256 × 256 pixels) were acquired at 0.33 Hz using Fluoview software (Olympus). Measurements were performed in Ca2+-free PSS containing 1 mM EGTA to inhibit Ca2+ influx. Data were analyzed offline with MetaMorph v.6.1 (Universal Instruments) and corrected for photobleaching, occurring at this acquisition rate under control conditions, using a monoexponential function. Fluorescence was expressed as F/F0 ratio, where F0 represents background control fluorescence.

Data analysis and statistics.

Data were analyzed and presented using pClamp 8 (Axon Instruments), Microsoft Excel, and Microcal Origin 6.0 software (Microcal Software, Northampton, MA). Activation dependencies were fitted with the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm in Origin 6.0 software. The goodness of fit was evaluated from the coefficient of determination R2 which ranged from 0.96 to 0.999. Data are expressed as means ± SE. The paired two-tail t-test was used to compare parameters obtained in control (which could be either PSS or pretreatment with another inhibitor) and test conditions in the same cell. A nonpaired t-test was used to compare the differences between two groups of data. When normality test failed (Shapiro-Wilk test), the Wilcoxon signed rank test and the Mann-Whitney's test were used for comparison of paired and nonpaired data, respectively. A one-way ANOVA with the Dunnett (equal variance) or Tamhane (nonequal variance) post hoc tests or Kruskal-Wallis for non-parametric data followed by Mann-Whitney's test with a Bonferroni correction were used to compare differences in half-activation potential and the IKv block between more than two groups of data. P < 0.05 was deemed significant.

RESULTS

Properties of IKv in freshly isolated rat PASMCs.

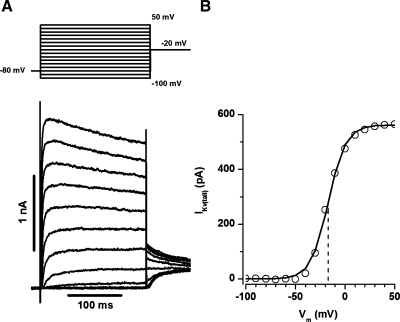

Kv channel currents have previously been characterized in a variety of cell types including PASMCs. IKv currents in the rat resistance PASMC represent a delayed rectifier type current, with fast-activating and slowly inactivation kinetics (40). Figure 1A shows representative traces of IKv recorded with the voltage protocol described in materials and methods. The current-voltage (I-V) curve was constructed from the tail currents measured 2–3 ms after membrane repolarization and clearly demonstrates that IKv in the PASMC activates at membrane potentials positive to −50 mV and is almost fully activated at voltages positive to +20 mV (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Kv channel currents recorded from freshly isolated rat small pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells (PASMC). A: a representative current trace recorded using the activation protocol (top). B: current-voltage (I-V) relationship for activation derived from the tail current measured from the example shown in A. Solid lines represent the fit to the Boltzmann equation with the half-activation potential (dashed line) mV and the slope factor equal to −16.9 and 8.8 mV, respectively. Cell membrane capacitance (Cm) was equal to 14.6 pF.

Mitochondrial inhibition shifts IKv activation to negative potentials and decreases IKv at positive potentials.

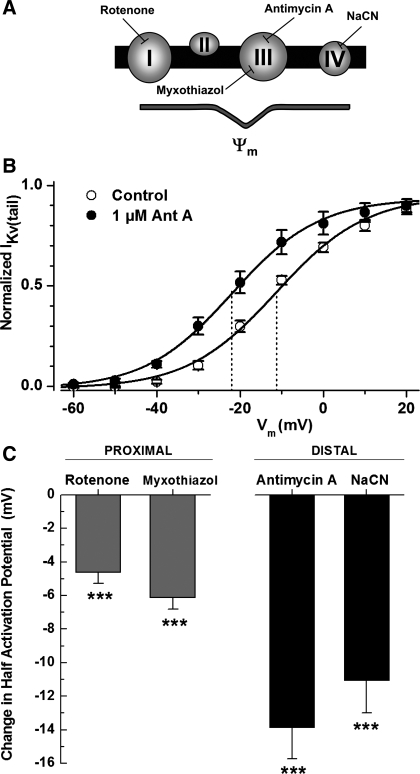

The impact of inhibition of the mETC, and therefore oxidative phosphorylation, on IKv in PAMSC was investigated using specific inhibitors for different sites in the mETC (Fig. 2A). Inhibitors investigated included: rotenone (inhibiting complex I), myxothiazol (inhibiting complex III proximal to the antimycin A site of action), antimycin A (inhibiting at complex III), and NaCN (acting at complex IV). The change in the half-activation potentials (determined from the fit to the Boltzmann equation) between control conditions and test conditions, subsequent to 5-min perfusion with the inhibitor, was compared. The I-V curve shown in Fig. 2B highlights the change in half-activation for inhibition of complex III by antimycin A, resulting in a negative shift of −13.8 ± 2 mV (P < 0.001, n = 9). All these mETC inhibitors caused a significant negative shift in IKv half-activation potentials, reflecting activation of the Kv channel currents at more negative potentials. It is worth noting that inhibiting more distal components of electron transport resulted in the largest negative shift in the half-activation potentials of IKv (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Inhibition of the mitochondrial electron transport chain (mETC) shifts IKv activation to more negative potentials. A: schematic depicting the mETC. Sites of inhibition with specific inhibitors are indicated. B: normalized IKv(tail) activation in control and in the presence of 1 μM antimycin A (n = 9). IKv(tail) was measured at 2–3 ms after a test potential, normalized and fitted to the Boltzmann equation as described in materials and methods. Solid lines were drawn with the half-activation potentials equal to −11.3 and −22 mV (dashed lines) and the slope factors equal to 10.8 and 10.4 mV for control and antimycin A, respectively. C: change in the half-activation potential between control and in the presence of the indicated inhibitor (n = 22, 10, 9, and 14, respectively). ***P < 0.001.

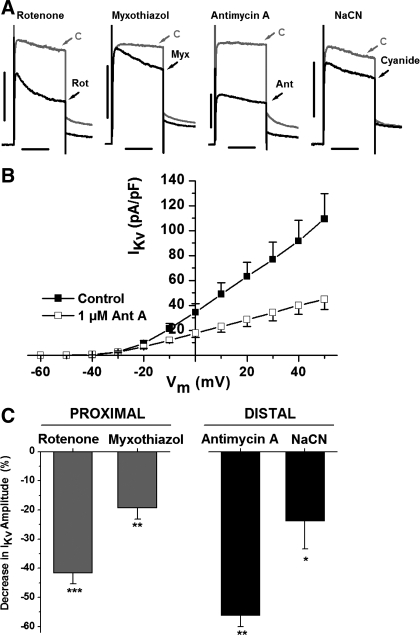

Additionally, all four inhibitors decreased current amplitude at positive potentials. The representative traces shown for each inhibitor in Fig. 3A reflect the decrease in current amplitude observed at +50 mV; the gray represents control, and the black reflects “test” conditions. The effect of inhibitors on the current amplitude was determined by the change in current density at each membrane potential in the absence and presence of the inhibitor. A representative I-V curve showing the effect of antimycin A on IKv current density is shown in Fig. 3B. A significant decrease in current amplitude resulting from closure or inactivation of Kv channels was observed at all potentials positive to −10 mV with 56 ± 4% block observed at +50 mV (P < 0.01, n = 9). The average decrease in IKv current amplitude for all inhibitors at +50 mV is shown in Fig. 3C. Interestingly, antimycin A, which inhibits complex III, had the greatest impact on both the enhanced channel activation and decreased IKv amplitude (Figs. 2 and 3). No significant effect was observed on the current activation kinetics [measured as a time constant from a single exponential fit of the current onset in response to a step membrane depolarization as previously described (40)]. For example, time constants of IKv activation measured at step depolarization to 0 and +50 mV in nine PASMCs were respectively equal to 8.7 ± 1.4 ms and 3.4 ± 0.5 ms in the presence of 1 μM antimycin A and 11.4 ± 1.9 ms and 3.0 ± 0.5 ms in the absence of the inhibitor.

Fig. 3.

Inhibition of the mETC decreases IKv amplitude at positive potentials. A: representative paired current traces at +50 mV for control (gray and marked as C) and in the presence of the indicated mETC inhibitors (black and marked as Rot, Myx, Ant, and cyanide for rotenone, myxothiazol, antimycin A, and NaCN, respectively). Cell capacitance was equal to 11.1 pF (rotenone), 14.2 pF (myxothiazol), 12.6 pF (antimycin A), and 14.7 pF (NaCN). Vertical and horizontal bars are equal to 1 nA and 100 ms, respectively. B: IKv current density in control and in the presence of 1 μM antimycin A (n = 9). C: decrease in the Kv current amplitude at +50 mV after 5-min perfusion with the indicated inhibitor (n = 22, 10, 9, and 14, respectively). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

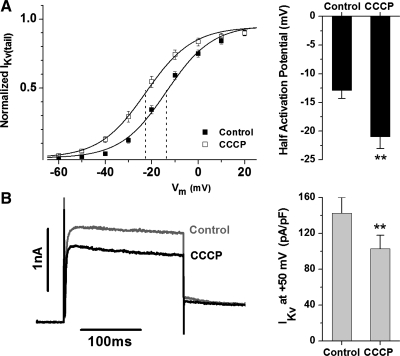

CCCP mimics the effect of the mETC inhibitors.

CCCP uncouples the mitochondrial electron transport by dissociating the proton gradient and thus causing mitochondrial depolarization. CCCP caused a similar change in half-activation potential reflecting a negative shift in Kv channel activation of −7.8 ± 2 mV (P < 0.01, n = 20) (Fig. 4A) and a decrease in current amplitude at +50 mV by 26 ± 5% (P < 0.01) (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Dissociation of the mitochondrial proton gradient with CCCP mimics the dual effect of the mitochondrial inhibitors. CCCP shifts IKv activation to more negative potentials and decreases the current amplitude at positive potentials. A: normalized IKv(tail) in control and in the presence of CCCP (left) and the average negative shift in the half-activation potential (right, n = 20). Solid lines were drawn in accordance with the Boltzmann equation with the half-activation potentials equal to −13.7 and −22.6 mV (dashed lines) and the slope factors equal to 9.9 and 10.0 mV for control and CCCP, respectively. B: representative current trace at +50 mV in control (gray) and in the presence of CCCP (black, left) and the average changes in the current amplitude at +50 mV (right, n = 20). Cm = 8.8 pF. **P < 0.01.

Effects of antimycin A are specific to inhibition of the mETC.

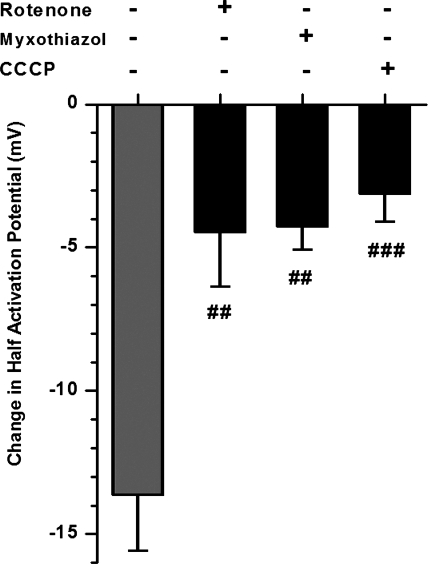

The similarity between the effects of all mETC inhibitors and CCCP strongly suggests that the observed changes in the IKv parameters are mainly due to inhibition of mitochondrial function. However, since antimycin A was subsequently used as the main pharmacological tool to inhibit the mETC due to its profound effects on IKv characteristics, its specificity was further assessed in the presence of rotenone or myxothiazol, which act proximal to the antimycin A inhibitory site at complex III. It would be anticipated that the effects of antimycin A, if associated with inhibition of the mETC complex III, will be attenuated in the presence of proximal inhibitors due to a reduction of electron flow to complex III. Such attenuation of antimycin A-mediated increases in ROS production has been demonstrated in isolated mitochondria (7, 17). Similarly, cell treatment with the mitochondrial uncoupler CCCP, which disrupts the proton gradient and causes mitochondrial depolarization, should also attenuate antimycin A-mediated effects. A significant suppression of the shifts in IKv activation induced by antimycin A was observed following cell pretreatment with either the mETC inhibitors or CCCP; this suggests that the antimycin A-mediated effects are specific to its actions on mitochondrial electron transport (Fig. 5). These results are consistent with the notion that antimycin A-mediated changes in IKv activation are mainly due to its inhibition of the mETC.

Fig. 5.

The effect of antimycin A on the negative shift in IKv activation is specific to its inhibition of the mETC. Proximal mETC inhibitors rotenone and myxothiazol (1 μM) and the mitochondrial uncoupler CCCP (2 μM) inhibit the antimycin A-induced (gray) negative shift in IKv half-activation in 8, 7, and 8 PASMCs, respectively. Cells were preincubated with each inhibitor for 5 min before recording the “control” I-V. Cells were then superfused with 1 μM antimycin A for 5 min before recording the test I-V. Experiments were performed in the whole cell configuration. The significance of the inhibition of the antimycin-induced change in half-activation is represented by the gray bar. ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001.

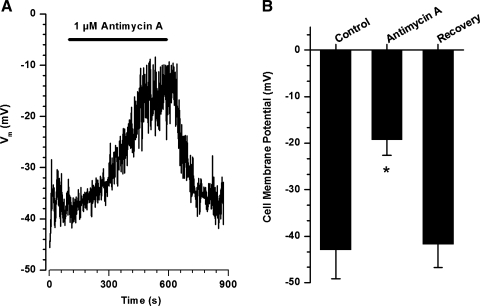

Effect of antimycin A on cell membrane potential.

The effect of antimycin A on the cell membrane potential was assessed in current clamp mode. Figure 6A shows typical changes in the cell membrane potential upon application of 1 μM antimycin A, which caused a slowly developing membrane depolarization from −40 mV to −16 mV. The effect was completely reversible following washout of the mETC inhibitor. Figure 6B summarizes the effect of antimycin A measured in three PASMCs.

Fig. 6.

Antimycin A slowly and reversibly depolarizes PASMCs. A: representative recording of the cell membrane potential in the current clamp mode. Cell capacitance was equal to 12.3 pF. B: summary of the antimycin A-induced changes in the cell membrane potential in 3 PASMCs. *P < 0.05 compared with control.

Changes in cellular ATP concentration block the enhanced IKv at negative potentials.

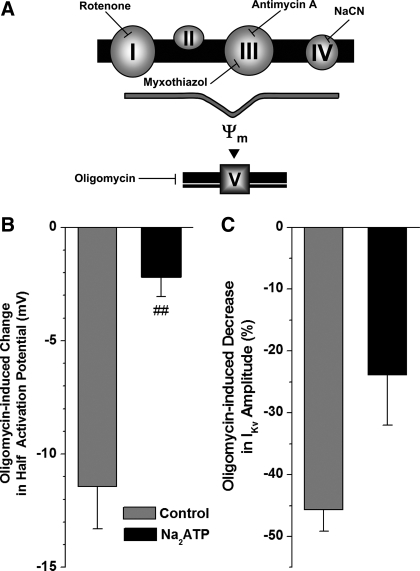

Inhibition of the mETC will impair oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria [which may lead to changes in intracellular metabolic state and subsequent alteration in the IKv properties as previously suggested (54)]. To investigate whether the effects on IKv were due to changes in ATP production, oligomycin, an inhibitor of the ATP synthase that acts by blocking proton transport, was studied (Fig. 7A). Oligomycin had potent effects and caused a significant negative shift in IKv activation (Fig. 7B, gray bar) and a substantial decrease of 46 ± 3% (P < 0.0001, n = 12) in IKv amplitude (Fig. 7C, gray bar). These effects were comparable to those observed with antimycin A. If these oligomycin-induced changes in IKv characteristics are due to its inhibition of ATP production by mitochondria, then addition of 5 mM ATP to the pipette solution should inhibit the effects of oligomycin on IKv. When PASMCs were dialyzed with 5 mM Na2ATP, the effect of oligomycin on IKv half-activation was almost completely inhibited (Fig. 7B, black bar). The oligomycin-induced inhibition of IKv amplitude was also decreased, but to a lesser extent (P < 0.01) (Fig. 7C).

Fig. 7.

Inhibition of the ATP transporter with oligomycin mimics the effects of the inhibition of the mETC on IKv activation and amplitude. A: schematic depicting the mitochondrial electron transport chain including ATP production by complex V. Sites of inhibition with specific inhibitors are indicated. B: effect of oligomycin (gray) on the half-activation (left, n = 12) and IKv amplitude at +50 mV (right, n = 12). Dialysis of the cells with ATP (5 mM Na2ATP in the pipette solution) inhibited the changes in IKv (black) (n = 6). ##P < 0.01, indicating significance of the inhibitory effect of Na2ATP compared with the control (gray bars).

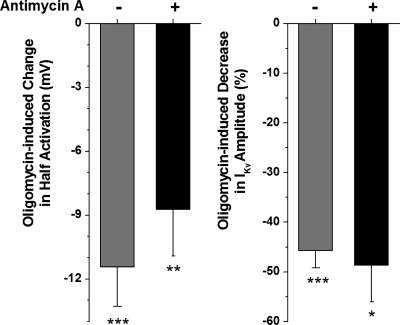

To investigate the possibility that antimycin A and oligomycin are acting via the same mechanism, the effects of oligomycin were studied in cells pretreated with antimycin A. Oligomycin caused an additional negative shift in IKv activation (Fig. 8, left) and a further decrease in IKv amplitude (Fig. 8, right) to that caused by antimycin A alone. These observations suggest that the effects of antimycin A are somewhat independent of oligomycin and may involve more than just an effect on mitochondrial ATP production.

Fig. 8.

The effects of antimycin and oligomycin on IKv are additive. Effect of preincubation with antimycin A on the oligomycin-induced changes in half-activation potential and the decrease in current amplitude (black columns, n = 7). For successive treatment, cells were perfused with antimycin A for 5 min and a control I-V was recorded. Cells were then perfused with antimycin A and oligomycin for 5 min before recording a “test” I-V. Oligomycin-induced changes in the presence of antimycin A was measured as the difference between the test and control recordings. Gray columns show the effects of oligomycin alone for comparison (n = 12). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Changes in cellular magnesium concentration contribute to the mitochondria-dependent dual effects on IKv.

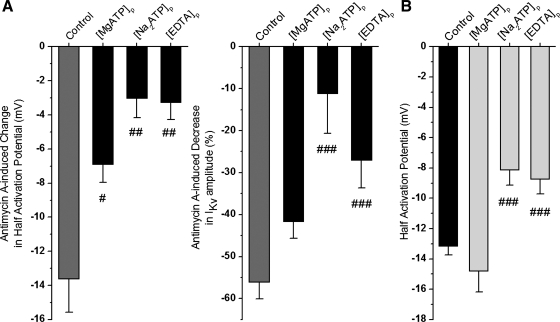

To verify that antimycin is having an effect in addition to its attenuation of ATP production, the dialysis of the cells with ATP was also investigated on the antimycin A-induced changes in IKv characteristics. Dialysis of the cells with either the magnesium salt of ATP (MgATP) or the disodium salt of ATP (Na2ATP) significantly attenuated the effects of antimycin A on the negative shift in IKv activation and the decrease in current amplitude (Fig. 9, A and B). However, it is interesting to notice that the effects of the magnesium-conjugated ATP salt were much less effective at attenuating the effects of antimycin A. Indeed, in the presence of the magnesium salt, antimycin A still caused a 42 ± 4% (n = 9) decrease in current amplitude compared with 56 ± 4% (n = 9) in the absence of ATP and 11 ± 9% (n = 8) in the presence of the disodium salt.

Fig. 9.

Changes in intracellular magnesium concentration also contribute to the effects of the mETC inhibition on IKv. Effect of intracellular Na2ATP (n = 8), MgATP (n = 9), and EDTA (n = 8) (no MgCl2 was added to the pipette solutions) on antimycin A induced changes in half-activation potential and a decrease in IKv amplitude at +50 mV (A). The effect of antimycin A under control conditions is shown in gray for comparison. B: absolute half-activation potential values due to change in each pipette solution as indicated (n = 184, 9, 22, and 25, respectively). #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, and ###P < 0.001. #Significance of the inhibitory effect in each pipette solution compared with the control.

Since ATP is a potent Mg2+ chelator, significant differences in the effect of the two ATP salts on the antimycin A-induced changes in IKv characteristics may be due to Na2ATP acting as a better Mg2+ buffer than MgATP. To investigate this, 5 mM EGTA was replaced with 5 mM EDTA, a more potent chelator of Mg2+ than EGTA, in the pipette solution. Under this condition, the antimycin A-mediated effects on the negative shift in IKv activation and the decreased current amplitude were significantly attenuated (Fig. 9, A and B, left, black bars), reflecting the changes observed by dialysis of the cells with Na2ATP. In addition, the effect of cell dialysis with the ATP salts and the exchange of EGTA for EDTA alone shifted the half-activation potentials to more positive potentials compared with control conditions while MgATP has a half-activation potential similar to the control pipette solution (Fig. 9B, right), again consistent with the idea that the changes in IKv activation may be due to the buffering capacity for magnesium.

In addition, an increase in [MgCl2] from 0.5 mM (control) to 10 mM in the pipette solution in seven PASMCs mimicked both effects of antimycin A on IKv, demonstrating a significant shift to more negative potentials in the steady-state activation dependency with the mean half-activation potentials equal to −13.2 ± 0.6 mV (n = 184) and −23 ± 3.1 mV (n = 7, P < 0.01) and a decreased current density from 133 ± 6 pA/pF (n = 184) to 68 ± 11 pA/pF in the control and increased pipette [MgCl2], respectively. These observations therefore support the possibility that the antimycin A-mediated modulation of IKv also depends on increased levels of [Mg2+]i.

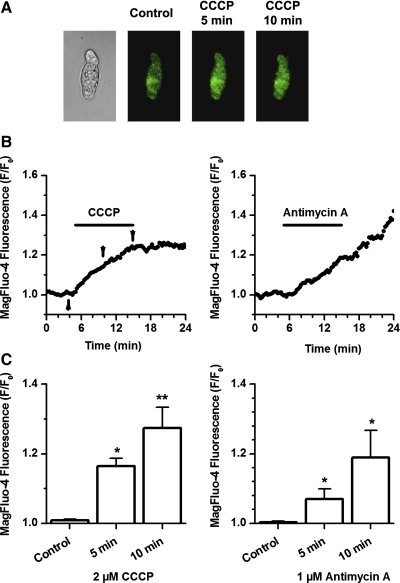

An increase in [Mg2+]i, in addition to [Ca2+]i in response to mitochondrial depolarization caused by mitochondrial uncouplers, has previously been demonstrated in cardiac myocytes (22) and in PC12 cells (21). However, there is no evidence that this process also occurs in PASMCs. Therefore, the effect of the mitochondrial uncoupler CCCP (2 μM) and the complex III inhibitor antimycin A (1 μM) was investigated in isolated PASMCs loaded with Mg2+-sensitive dye, MagFluo-4-AM, and in the presence of BAPTA-AM (to minimize [Ca2+]i-dependent contamination of the fluorescent signal, data not shown). Experiments were also performed in a Ca2+-free solution containing 1 mM EGTA. Figure 10A illustrates the effect of CCCP on MagFluo-4 fluorescence in a representative experiment. Time dependence of changes in MagFluo-4 signal observed in the presence of CCCP and antimycin A are shown in Fig. 10B. The effect was statistically compared 5 and 10 min after addition of the mitochondrial inhibitors (Fig. 10C). As shown in this figure, both agents caused significant increases in [Mg2+]i, supporting a role of [Mg2+]i in the mitochondria-mediated modulation of IKv. Interestingly, the basal level of [Mg2+]i did not recover after the removal of CCCP and antimycin A. This effect was also observed in cardiac myocytes (22).

Fig. 10.

Inhibition of the mETC increases [Mg2+]i in single PASMCs. A: representative transmitted light (left) and fluorescence images of a PASMC loaded with MagFluo-4 in response to 2 μM CCCP at the time of application indicated above. B: time dependence of changes in the intensity of the MagFluo-4 fluorescence expressed as F/F0. Arrows indicate time points where images shown in A were taken. C: averaged effect of CCCP and antimycin A on [Mg2+]i at 5- and 10-min period (n = 7 and 7, respectively). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

The use of paxilline (a BKCa inhibitor) and glibenclamide (a KATP channel blocker) allows effective isolation of the major voltage-dependent 4-aminopyridine-sensitive IKv in PASMCs, as we have previously demonstrated (40). Glibenclamide was necessary because our standard pipette solutions did not include ATP, which would minimize KATP currents. Contribution from other K+ channels, such as TASK or KCNQ, recently described in PASMCs (13, 14, 16, 19), is likely to be relatively small in proportion to the dominant whole cell IKv. Also, TASK currents are voltage independent, whereas KCNQ-mediated currents do not inactivate, both properties that are completely different from characteristics of IKv.

Inhibition of mitochondrial function causes a negative shift in IKv activation and decreases IKv amplitude.

A close functional relationship between Kv channels and mitochondria is supported by experiments in dialyzed PASMCs where inhibition of mitochondrial function was impaired by several inhibitors, each targeting a different point in the electron transport chain (Fig. 2A). All these inhibitors had a dual effect on IKv. A hyperpolarizing (or negative) shift in the steady-state activation dependency, reflecting an increase in Kv channel activation at negative membrane voltages, was observed, as demonstrated in Fig. 2. A significantly decreased current amplitude occurring at membrane potentials positive to 0 mV, i.e., in the voltage range where the current activation is mostly completed, was also prominent. These effects were most potent due to inhibition of complex III by antimycin A, blocking the flow of electrons from semiquinone to ubiquinone in the Q cycle in complex III, and to oligomycin inhibiting ATP synthase by blocking its proton channel, essential for the oxidative phosphorylation of ADP to ATP.

As each inhibitor acts on a different part of mitochondrial electron transport chain and was used in the experiment at a relatively low concentration, it is highly unlikely that the observed effects were nonspecific. Furthermore, significant attenuation of the antimycin A-mediated shifts in the IKv activation in the presence of more proximal mETC inhibitors and CCCP (Fig. 5) and significant attenuation of antimycin A-induced changes in both IKv activation and amplitude by intracellular ATP or EDTA (Fig. 9), strongly supports this conclusion.

ATP and [Mg2+]i are mitochondria-dependent effectors targeting Kv channels.

Inhibition of the mETC ultimately disrupts the proton gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane. This disruption of the proton gradient prevents the ATP production due to a lack of protons to flow through and activate the ATP synthase (18). The addition of ATP to the intracellular solution significantly attenuated the effects of both oligomycin and antimycin A on IKv characteristics. As oligomycin is a specific inhibitor of the ATP synthase, intracellular ATP concentrations would be significantly decreased. Addition of ATP to the pipette solution significantly attenuated the effects of oligomycin and antimycin A on IKv half-activation potentials. The lack of inhibition of the effect of oligomycin by preincubation with antimycin A potentially suggests that either these agents are affecting IKv via different mechanisms or that they act via the same mechanism with additive potency at the concentrations used in our experiments. Higher concentrations were not evaluated due to the likelihood of nonspecific actions occurring. As ATP did not completely inhibit the changes in IKv characteristics and due to the significant difference between the antimycin A-dependent negative shift in IKv half-activation in the presence of intracellular MgATP and Na2ATP, a significant attenuation of its effect in cells dialyzed with EDTA, and the ability of increased [Mg2+]i to cause a negative shift in the IKv activation, an involvement of [Mg2+]i is strongly indicated. Our, and other, laboratories have previously demonstrated a [Mg2+]i-dependent shift to more negative potentials in the steady-state activation of Kv1.5 and Kv2.1 channels (8, 44). Both Kv channel subtypes are proposed as molecular candidates for IKv in native PASMCs (reviewed in Ref. 9). Confirmation of an involvement of [Mg2+]i in the regulation of IKv is provided by a significant elevation of [Mg2+]i in response to CCCP and antimycin A in single PASMCs. Increases in [Mg2+]i in response to mitochondrial inhibition and to hypoxia have previously been reported in cardiac myocytes (5, 22, 39); this is the first report of such phenomenon in the pulmonary vasculature. Contribution of [Ca2+]i [previously suggested to play a role in the modulation of IKv (35)] to the observed effects is unlikely because: 1) data were obtained from cells where free [Ca2+]i (∼10 nM) was strongly buffered with 10 mM EGTA; and 2) cell dialysis with 220 nM Ca2+ alone caused a significant rightward shift in IKv activation (unpublished observations), an effect opposite to that described in this paper.

Elevation of [Mg2+]i as a result of inhibition of the mETC may be explained by decreased oxidative phosphorylation leading to a reduced level of ATP and resulting in an increased ADP-to-ATP ratio. Since ADP is a less potent Mg2+ chelator than ATP, [Mg2+]i would increase. The ability of the mitochondrial inhibitors used and CCCP to cause a hyperpolarizing shift in the IKv activation supports this suggestion. Also, [Mg2+]i may be additionally increased when mitochondria are depolarized as mitochondrial uptake of Mg2+ is directly linked to the proton motive force (20). Based on evidence obtained in isolated mitochondria, Mg2+ efflux can be increased in depolarized mitochondria (21) or the rate of ATP hydrolysis by the ATP synthase (working in the reverse mode to restore the mitochondrial membrane potential) could also be increased (11). It is currently difficult to accurately evaluate changes in ATP or Mg2+ concentration in submembrane compartments in intact cells. Nevertheless, changes in the Kv channel parameters can serve as useful markers to evaluate changes in the subplasmalemmal environment in the close vicinity to the channel in PASMCs. Indeed, KATP channels and BKCa channels have been similarly used as probes to assess changes in ATP and [Ca2+]i concentrations, respectively, directly beneath the plasma membrane (15, 43).

Mitochondria-mediated decrease in IKv amplitude.

In contrast to the changes in IKv activation, the decrease in IKv amplitude was significantly attenuated only by buffering Mg2+ (Fig. 9A). Such observations suggest that an increase in [Mg2+]i could also be responsible for the IKv block at positive membrane potentials and is also supported by the observation that the current density was significantly reduced when cells were dialyzed with 10 mM Mg2+ compared with control. The ability of [Mg2+]i to inhibit of variety of ion channels, including Kv channels, is well recognized (reviewed in Ref. 2). The mechanism of the block of Kv channels by [Mg2+]i is thought to be a result of the direct occlusion of the channel pore and interference with K+ efflux and is therefore most prominent at positive potentials (8, 24, 25). Interestingly, [Mg2+]i was shown to have a greater inhibitory effect on the delayed rectifier Kv channel, like the one expressed in PASMCs, than rapidly inactivating A-type Kv currents (25). This may contribute to specificity of [Mg2+]i-dependent effects in different preparations.

Several other mechanisms may contribute to the dual effects of mitochondrial inhibition on IKv reported in this paper; investigation of these was beyond the scope of this manuscript. Antimycin itself binds to the Qi site of complex III (the cytochrome c oxidoreductase enzyme); cytochrome c is thus known to be activated by antimycin A, released from the mitochondria, and has recently been shown to activate Kv channels in PASMCs, increasing IKv (34). This process is, however, unlikely to occur within the time frame used in our experiments as in isolated mitochondria neither rotenone, antimycin A, cyanide, nor FCCP were able to induce cytochrome c release or mitochondrial swelling following 10-min pretreatment (23). Furthermore, complex III is a major site for the free radical, superoxide to be produced, and antimycin A is known to increase production of reactive oxygen species (6). Such reactive oxygen species of mitochondrial origin have been suggested to be the effectors mediating the effects of hypoxia on Kv channels (reviewed in Ref. 28). It is worth noting that due to changes in the proton motive force and a nonlinear link between the mitochondrial membrane potential and mitochondrial superoxide production (29), a potential interaction between mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and [Mg2+]i is likely to occur, and further studies are necessary to establish the role reactive oxygen species could play in Mg2+-mediated regulation of Kv channels in PASMCs.

The depolarizing effect of antimycin A on the cell membrane potential (Fig. 6) suggests that mitochondria-dependent inhibition of IKv could play an important role in the regulation of the cell membrane potential in PASMCs. A slow time course of antimycin A-dependent depolarization is different from the relatively rapid depolarizing effect of the nonselective inhibitor of Kv channels 4-aminopyridine reported previously by several groups (38, 41, 54). It is possible that such differences in the onset of membrane depolarization in response to mETC inhibition and the direct inhibition of Kv currents with 4-aminopyridine are due to mitochondria-mediated changes in the steady-state activation of IKv, which would oppose membrane depolarization.

In conclusion, our data comprehensively demonstrate a close functional association between the Kv channels and the putative oxygen sensor mitochondria in PASMCs. Mitochondria-dependent changes in intracellular ATP and Mg2+ concentrations significantly contribute as functional effectors in this process. A potential role for these mechanisms in the unique response of PASMC to hypoxia may exist and requires further experimentation.

GRANTS

This work was supported by British Heart Foundation Grants PG03/059 and PG04/069 (to K. H. Yuill).

Present address for A. L. Firth: Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aaronson PI, Robertson TP, Knock GA, Becker S, Lewis TH, Snetkov V, Ward JP. Hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction: mechanisms and controversies. J Physiol 570: 53–58, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agus ZS, Morad M. Modulation of cardiac ion channels by magnesium. Annu Rev Physiol 53: 299–307, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Archer SL, Huang J, Henry T, Peterson D, Weir EK. A redox-based O2 sensor in rat pulmonary vasculature. Circ Res 73: 1100–1112, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Archer SL, Wu XC, Thébaud B, Nsair A, Bonnet S, Tyrrell B, McMurtry MS, Hashimoto K, Harry G, Michelakis ED. Preferential expression and function of voltage-gated, O2-sensitive K+ channels in resistance pulmonary arteries explains regional heterogeneity in hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction: ionic diversity in smooth muscle cells. Circ Res 95: 308–318, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Budinger GR, Duranteau J, Chandel NS, Schumacker PT. Hibernation during hypoxia in cardiomyocytes. Role of mitochondria as the O2 sensor. J Biol Chem 273: 3320–3326, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chandel NS, Maltepe E, Goldwasser E, Mathieu CE, Simon MC, Schumacker PT. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species trigger hypoxia-induced transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 11715–11720, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Q, Vazquez EJ, Moghaddas S, Hoppel CL, Lesnefsky EJ. Production of reactive oxygen species by mitochondria: central role of complex III. J Biol Chem 278: 36027–36031, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Claydon TW, Kwan DC, Fedida D, Kehl SJ. Block by internal Mg2+ causes voltage-dependent inactivation of Kv1.5. Eur Biophys J 36: 23–34, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coppock EA, Martens JR, Tamkun MM. Molecular basis of hypoxia-induced pulmonary vasoconstriction: role of voltage-gated K+ channels. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 281: L1–L12, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corkey BE, Duszynski J, Rich TL, Matschinsky B, Williamson JR. Regulation of free and bound magnesium in rat hepatocytes and isolated mitochondria. J Biol Chem 261: 2567–2574, 1986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Lisa F, Blank PS, Colonna R, Gambassi G, Silverman HS, Stern MD, Hansford RG. Mitochondrial membrane potential in single living adult rat cardiac myocytes exposed to anoxia or metabolic inhibition. J Physiol 486: 1–13, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evans AM, Clapp LH, Gurney AM. Augmentation by intracellular ATP of the delayed rectifier current independently of the glibenclamide-sensitive K-current in rabbit arterial myocytes. Br J Pharmacol 111: 972–974, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gardener MJ, Johnson IT, Burnham MP, Edwards G, Heagerty AM, Weston AH. Functional evidence of a role for two-pore domain potassium channels in rat mesenteric and pulmonary arteries. Br J Pharmacol 142: 192–202, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gönczi M, Szentandrássy N, Johnson IT, Heagerty AM, Weston AH. Investigation of the role of TASK-2 channels in rat pulmonary arteries; pharmacological and functional studies following RNA interference procedures. Br J Pharmacol 147: 496–505, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gribble FM, Loussouarn G, Tucker SJ, Zhao C, Nichols CG, Ashcroft FM. A novel method for measurement of sub-membrane ATP concentration. J Biol Chem 275: 30046–30049, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gurney AM, Osipenko ON, MacMillan D, McFarlane KM, Tate RJ, Kempsill FE. Two-pore domain K channel, TASK-1, in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Circ Res 93: 957–964, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han D, Canali R, Rettori D, Kaplowitz N. Effect of glutathione depletion on sites and topology of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide production in mitochondria. Mol Pharmacol 64: 1136–1144, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jezek P, Hlavatá L. Mitochondria in homeostasis of reactive oxygen species in cell, tissues, and organism. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 37: 2478–2503, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joshi S, Balan P, Gurney AM. Pulmonary vasoconstrictor action of KCNQ potassium channel blockers. Respir Res 7: 31, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jung DW, Panzeter E, Baysal K, Brierley GP. On the relationship between matrix free Mg2+ concentration and total Mg2+ in heart mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta 1320: 310–320, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kubota T, Shindo Y, Tokuno K, Komatsu H, Ogawa H, Kudo S, Kitamura Y, Suzuki K, Oka K. Mitochondria are intracellular magnesium stores: investigation by simultaneous fluorescent imagings in PC12 cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 1744: 19–28, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leyssens A, Nowicky AV, Patterson L, Crompton M, Duchen MR. The relationship between mitochondrial state, ATP hydrolysis, [Mg2+]i and [Ca2+]i studied in isolated rat cardiomyocytes. J Physiol 496: 111–128, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Q, Sato EF, Kira Y, Nishikawa M, Utsumi K, Inoue M. A possible cooperation of SOD1 and cytochrome c in mitochondria-dependent apoptosis. Free Radic Biol Med 40: 173–181, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lopatin AN, Nichols CG. Internal Na+ and Mg2+ blockade of DRK1 (Kv2.1) potassium channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Inward rectification of a delayed rectifier. J Gen Physiol 103: 203–216, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ludewig U, Lorra C, Pongs O, Heinemann SH. A site accessible to extracellular TEA+ and K+ influences intracellular Mg2+ block of cloned potassium channels. Eur Biophys J 22: 237–247, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mauban JR, Remillard CV, Yuan JX. Hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction: role of ion channels. J Appl Physiol 98: 415–420, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Michelakis ED, Rebeyka I, Wu X, Nsair A, Thébaud B, Hashimoto K, Dyck JR, Haromy A, Harry G, Barr A, Archer SL. O2 sensing in the human ductus arteriosus: regulation of voltage-gated K+ channels in smooth muscle cells by a mitochondrial redox sensor. Circ Res 91: 478–486, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Michelakis ED, Thébaud B, Weir EK, Archer SL. Hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction: redox regulation of O2-sensitive K+ channels by a mitochondrial O2-sensor in resistance artery smooth muscle cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol 37: 1119–1136, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nicholls DG Mitochondrial membrane potential and aging. Aging Cell 3: 35–40, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olschewski A, Hong Z, Nelson DP, Weir EK. Graded response of K+ current, membrane potential, and [Ca2+]i to hypoxia in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 283: L1143–L1150, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park MK, Bae YM, Lee SH, Ho WK, Earm YE. Modulation of voltage-dependent K+ channel by redox potential in pulmonary and ear arterial smooth muscle cells of the rabbit. Pflügers Arch 434: 764–771, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patel AJ, Lazdunski M, Honoré E. Kv2.1/Kv9.3, a novel ATP-dependent delayed-rectifier K+ channel in oxygen-sensitive pulmonary artery myocytes. EMBO J 16: 6615–6625, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Platoshyn O, Golovina VA, Bailey CL, Limsuwan A, Krick S, Juhaszova M, Seiden JE, Rubin LJ, Yuan JX. Sustained membrane depolarization and pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell proliferation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 279: C1540–C1549, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Platoshyn O, Zhang S, McDaniel SS, Yuan JX. Cytochrome c activates K+ channels before inducing apoptosis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 283: C1298–C1305, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Post JM, Gelband CH, Hume JR. [Ca2+]i inhibition of K+ channels in canine pulmonary artery. Novel mechanism for hypoxia-induced membrane depolarization. Circ Res 77: 131–139, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Post JM, Hume JR, Archer SL, Weir EK. Direct role for potassium channel inhibition in hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 262: C882–C890, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reeve HL, Weir EK, Nelson DP, Peterson DA, Archer SL. Opposing effects of oxidants and antioxidants on K+ channel activity and tone in rat vascular tissue. Exp Physiol 80: 825–834, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shimoda LA, Sylvester JT, Sham JS. Chronic hypoxia alters effects of endothelin and angiotensin on K+ currents in pulmonary arterial myocytes. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 277: L431–L439, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Silverman HS, Di Lisa F, Hui RC, Miyata H, Sollott SJ, Hanford RG, Lakatta EG, Stern MD. Regulation of intracellular free Mg2+ and contraction in single adult mammalian cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 266: C222–C233, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smirnov SV, Beck R, Tammaro P, Ishii T, Aaronson PI. Electrophysiologically distinct smooth muscle cell subtypes in rat conduit and resistance pulmonary arteries. J Physiol 538: 867–878, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smirnov SV, Robertson TP, Ward JPT, Aaronson PI. Chronic hypoxia is associated with reduced delayed rectifier K+ current in rat pulmonary artery muscle cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 266: H365–H370, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith AL, Yuill KH, Smirnov SV. The effect of mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC) inhibitors on voltage-dependent K+ (Kv) currents in rat small pulmonary arterial myocytes (PAMs). J Physiol 567P: PC159, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stehno-Bittel L, Sturek M. Spontaneous sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release and extrusion from bovine, not porcine, coronary artery smooth muscle. J Physiol 451: 49–78, 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tammaro P, Smirnov SV, Moran O. Effects of intracellular magnesium on Kv1.5 and Kv2.1 potassium channels. Eur Biophys J 34: 42–51, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tammaro P, Smith AL, Crowley BL, Smirnov SV. Modulation of the voltage-dependent K+ current by intracellular Mg2+ in rat aortic smooth muscle cells. Cardiovasc Res 65: 387–396, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tammaro P, Smith AL, Hutchings SR, Smirnov SV. Pharmacological evidence for a key role of voltage-gated K+ channels in the function of rat aortic smooth muscle cells. Br J Pharmacol 143: 303–317, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ward JP, Snetkov VA, Aaronson PI. Calcium, mitochondria and oxygen sensing in the pulmonary circulation. Cell Calcium 36: 209–220, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Waypa GB, Schumacker PT. Hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction: redox events in oxygen sensing. J Appl Physiol 98: 404–414, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weir EK, Archer SL. The mechanism of acute hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction: the tale of two channels. FASEB J 9: 183–189, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yu Y, Platoshyn O, Zhang J, Krick S, Zhao Y, Rubin LJ, Rothman A, Yuan JX. c-Jun decreases voltage-gated K+ channel activity in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Circulation 104: 1557–1563, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yuan XJ Voltage-gated K+ currents regulate resting membrane potential and [Ca2+]i in pulmonary arterial myocytes. Circ Res 77: 370–378, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yuan XJ, Goldman WF, Tod ML, Rubin LJ, Blaustein MP. Hypoxia reduces potassium currents in cultured rat pulmonary but not mesenteric arterial myocytes. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 264: L116–L123, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yuan XJ, Tod ML, Rubin LJ, Blaustein MP. Hypoxic and metabolic regulation of voltage-gated K+ channels in rat pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Exp Physiol 80: 803–813, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yuan XJ, Tod ML, Rubin LJ, Blaustein MP. Deoxyglucose and reduced glutathione mimic effects of hypoxia on K+ and Ca2+ conductances in pulmonary artery cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 267: L52–L63, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]