Abstract

We investigated the effects of intrathecal application of GABAA- or GABAB-receptor agonists on detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia (DSD) in spinal cord transection (SCT) rats. Adult female Sprague-Dawley rats were used. At 4 wk after Th9-10 SCT, simultaneous recordings of intravesical pressure and urethral pressure were performed under an awake condition to examine the effect of intrathecal application of GABAA and GABAB agonists (muscimol and baclofen, respectively) or GABAA and GABAB antagonists (bicuculline and saclofen, respectively) at the level of L6-S1 spinal cord. In spinal-intact rats, the effects of bicuculline and saclofen on bladder and urethral activity were also examined. During urethral pressure measurements, DSD characterized by urethral pressure increases during isovolumetric bladder contractions were observed in 95% of SCT rats. However, after intrathecal application of muscimol or baclofen, urethral pressure showed urethral relaxation during isovolumetric bladder contractions. The effective dose to induce inhibition of urethral activity was lower compared with the dose that inhibited bladder contractions. The effect of muscimol and baclofen was antagonized by intrathecal bicuculline and saclofen, respectively. In spinal-intact rats, intrathecal application of bicuculline induced DSD-like changes. These results indicate that GABAA- and GABAB-receptor activation in the spinal cord exerts the inhibitory effects on DSD after SCT. Decreased activation of GABAA receptors due to hypofunction of GABAergic mechanisms in the spinal cord might be responsible, at least in part, for the development of DSD after SCT.

Keywords: bladder, urethra, spinal cord, γ-aminobutyric acid, detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia

micturition depends on the coordination between the bladder and external urethral sphincter (8). However, in the chronic phase of spinal cord injury, the bladder exhibits detrusor overactivity, and bladder-sphincter coordination is impaired, leading to detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia (DSD), which is simultaneous contractions of the external urethral sphincter and bladder during the micturition reflex (4). These lower urinary tract dysfunctions then produce various problems, such as urinary incontinence, recurrent urinary tract infection, and vesicoureteral reflux, with or without upper urinary tract deterioration.

It has been reported that glutamate, glycine, and opioids can modulate the activity of the external urethral sphincter in the DSD condition (13, 15, 21). Glutamate is known to be a major excitatory neurotransmitter (18), and both ionotropic N-methyl- d-aspartate and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxasole propionic acid glutamate receptor antagonists inhibit urethral activity in spinal cord injury rats (15). Glycine is a major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system, and intrathecal or dietary glycine also inhibits urethral activity in spinal cord injury rats (13). Opioids are also abundant inhibitory neurotransmitters (7), and activation of spinal κ-opioid receptors selectively depresses the reflex pathways that control external urethral sphincter function in spinal cord injury rats (21).

γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) is another important inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system (18) and is known to have an important role in inhibitory regulation of the micturition reflex in spinal-intact rats (9). In our recent study, intrathecal muscimol and baclofen (GABAA- and GABAB-receptor agonists, respectively) were shown to inhibit detrusor overactivity in spinal cord transection (SCT) rats (14). However, to our knowledge, the role of the GABAergic system in modulating urethral activity after spinal cord injury is relatively unexplored, although the GABAB-receptor agonist baclofen administered intrathecally or intravenously reduces urethral resistance in humans with traumatic paraplegia and severe spasticity (6, 20). Thus, in the present study, we examined the effects of GABAA- or GABAB-receptor activation in the spinal cord on bladder and urethral activity in SCT rats. Furthermore, to explore the mechanisms involved in the genesis of DSD, we also examined the effect of GABAA- and GABAB-receptor antagonists on bladder and urethral activity in spinal-intact rats.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal model.

A total of 31 adult female Sprague-Dawley rats, weighing 236–270 g, were used according to the experimental protocol approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Rats were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane, and Th9 laminectomy was performed. To produce SCT, the dura was opened, complete transection of the Th9-Th10 spinal cord was performed with scissors, and a sterile Surgifoam sponge (Ferrosan, Soeborg, Denmark) was placed between the cut ends of the spinal cord. The overlying muscle and skin were sutured. Postoperatively, the animals were treated with antibiotics (100 mg/kg ampicillin intramuscularly) for 5 days. The bladder of spinalized rats was emptied by the Crede maneuver twice a day until reflex voiding recovered, usually 10–14 days after spinalization.

Surgical procedure.

In spinal-intact rats and SCT rats 4 wk after spinalization, laminectomy was performed at the level of the third lumbar vertebra, and a polyethylene catheter (PE-10, Clay-Adams, Parsippany, NJ) was implanted intrathecally at the level of L6-S1 spinal cord under isoflurane anesthesia through a small hole made at the dura. The end of the catheter was heat sealed and placed subcutaneously.

One or two days after intrathecal catheter implantation, the animals were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane, and the abdomen was opened via midline laparotomy. The ureters were transected at the level of the aortic bifurcation, and the distal ends were ligated (10, 17). An especially fabricated double-lumen catheter was inserted from the bladder dome for urethral pressure measurements (10, 17). This catheter consisted of an outer cannula of PE-160 (Clay Adams) and an inner cannula of PE-50 (Clay Adams) tubing, which protruded for 1 mm. The tip was embedded and secured with glue in a cone-shaped plug fashioned from an Eppendorf pipette tip. The double-lumen catheter tip was then seated in the bladder neck to measure urethral pressure, independent of bladder pressure. A PE-90 (Clay Adams) catheter was also inserted through the lateral side of the bladder to record the intravesical pressure. The implanted intrathecal catheter was exteriorized through a skin incision for drug administration. After the abdomen was closed, the SCT rats were placed in a restrainer (Braintree Scientific, Braintree, MA) and were allowed to recover from anesthesia for 1–2 h. In spinal-intact rats, isoflurane anesthesia was turned off and replaced with urethane anesthesia (1.0 g/kg subcutaneously) (Sigma Chemical, St. Lois, MO).

Simultaneous recording of urethral pressure and intravesical pressure before and after intrathecal injection of GABAA (n = 6) or GABAB (n = 6) agonist in SCT rats.

The urethra was perfused with physiological saline via the outer cannula at 0.075 ml/min using an infusion pump. Urethral pressure was recorded via the fluid-filled inner cannula connected to a pressure transducer mounted at the level of the pubic symphysis. The intravesical catheter was connected to a pressure transducer and to an infusion pump through a three-way stopcock. The bladder was infused with physiological saline at a rate of 0.08 ml/min until isovolumetric rhythmic bladder contractions were induced and maintained (bladder volume range: 1.2–2.5 ml), and then saline infusion was stopped. When rhythmic bladder contractions became stable for at least 30 min, the interval and amplitude of isovolumetric bladder contractions and baseline intravesical pressure were measured. Baseline urethral pressure and changes in urethral pressure from the baseline at the peak of bladder contractions were also measured to evaluate urethral activity. Muscimol (GABAA agonist; 0.001–1 μg) or (±)-baclofen (GABAB agonist; 0.001–1 μg) was administered cumulatively through the intrathecal catheter at intervals ranging from 15 to 30 min using a microsyringe (10 μl, Hamilton, Reno, NV). Bladder and urethral pressure parameters obtained after each intrathecal drug injection were averaged and then compared with control values obtained during a 30-min period before drug injection.

Simultaneous recording of urethral pressure and intravesical pressure before and after intrathecal injection of GABAA (n = 4) or GABAB (n = 4) antagonist in SCT rats.

To confirm the receptor subtype mediating the effect of GABA-receptor agonists, (−)-bicuculline methobromide (GABAA antagonist; 0.01 μg) and saclofen (GABAB antagonists; 1 μg) were injected intrathecally 3 min before intrathecal administration of muscimol (0.01 μg) and baclofen (0.01 μg), respectively.

Simultaneous recording of urethral pressure and intravesical pressure before and after intrathecal injection of GABAA (n = 5) or GABAB (n = 4) antagonist in spinal-intact rats.

To clarify the mechanisms inducing DSD, the effect of intrathecal injection of (−)-bicuculline methobromide (0.1 μg) or saclofen (1 μg) on bladder and urethral activity was examined in spinal-intact rats. The dose of drugs was selected based on the results of our previous study (14) and our own preliminary experiments. During simultaneous recordings of intravesical pressure and urethral pressure, the following parameters were measured: the interval and amplitude of isovolumetric contractions, baseline urethral pressure, changes in urethral pressure at the peak of bladder contractions, and the mean rate and amplitude of high-frequency oscillations (HFOs) of urethral striated muscles during bladder contractions (16).

Administration of drugs.

For intrathecal administration, 1 μl of drug solution, followed by 10 μl of saline, were injected through the implanted intrathecal catheter. After the experiments, the position of the intrathecal catheter was checked in all animals, and the extent of dye distribution in the subarachnoid space was confirmed by injection of 2 μl Evans blue flushed with 10 μl saline. Muscimol, (−)-bicuculline methobromide, and saclofen (Tocris Cookson, Ellisville, MO) were dissolved in distilled water. (±)-Baclofen (Tocris Cookson) was dissolved in 1 N NaOH. Intrathecal application of 1 N NaOH (1 μl) had no effects on bladder and urethral activity (n = 2).

Statistical analysis.

Data are expressed as means ± SE. Repeated-measures ANOVA, followed by Dunnett posttest, was used to compare changes in bladder and urethral activity before and after cumulative drug injections in SCT rats. Student's t-test for paired data was used to compare changes in bladder and urethral activity before and after single-drug injections in spinal-intact rats. P values <0.05 were considered to be significant.

RESULTS

Changes in bladder and urethral activity after intrathecal injection of muscimol (0.001–1 μg) in SCT rats (n = 6).

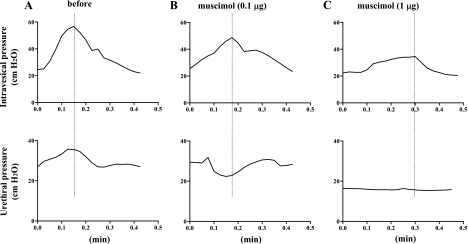

In five of six SCT rats, DSD (i.e., an increase in urethral pressure during bladder contraction) was observed (Fig. 1A). One remaining SCT rat showed incomplete synergistic urethral relaxation during bladder contractions. When muscimol (0.001–1 μg) was injected intrathecally in five SCT rats with DSD, a significant decrease in urethral pressure rises during bladder contractions was detected at 0.01–1 μg of muscimol, and a change to detrusor-sphincter synergy evidence by a negative shift of urethral pressure during bladder contractions was observed at 0.1 μg muscimol (Table 1, Fig. 1B). While 0.01–0.1 μg muscimol did not significantly change bladder contraction amplitude, 1 μg muscimol significantly reduced the amplitude, and, at the same time, urethral pressure changes during isovolumetric bladder contractions almost disappeared (Table 1, Fig. 1C). The interval between bladder contractions and the baseline intravesical or urethral pressures was not affected by intrathecal injection of muscimol (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Isovolumetric cystometry and urethral pressure in a spinal cord transection (SCT) rat before (A) and after intrathecal application of 0.1 μg (B) and 1 μg of muscimol (C). A: increases in urethral pressure during bladder contractions indicative of detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia (DSD) were recorded before drug application. B: after intrathecal muscimol (0.l μg), urethral pressure responses during bladder contraction were changed to a synergic pattern, as evidenced by a negative shift of urethral pressure during bladder contractions. C: after intrathecal muscimol (1 μg), bladder contraction amplitude was decreased, and changes in urethral pressure became negligible.

Table 1.

Effects of intrathecal application of muscimol and baclofen on bladder pressure and urethral pressure in spinal cord transection rats

| Control | 0.001 μg | 0.01 μg | 0.1 μg | 1 μg | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muscimol (n = 5) | ||||||||||

| Bladder contraction interval, min | 0.43±0.08 | 0.50±0.02 | 0.57±0.15 | 0.55±0.12 | 0.68±0.10 | |||||

| Bladder amplitude, cmH2O | 26.8±4.8 | 22.1±5.3 | 19.5±5.5 | 16.6±2.8 | 11.1±1.7* | |||||

| Bladder baseline pressure, cmH2O | 19.0±2.2 | 17.3±2.5 | 17.7±2.2 | 18.2±3.1 | 17.8±2.8 | |||||

| Urethral pressure change, cmH2O | 17.7±4.1 | 8.9±2.6 | 4.2±3.9* | −2.9±3.4† | −0.5±3.0† | |||||

| Urethral baseline pressure, cmH2O | 24.0±5.4 | 15.3±3.3 | 14.6±2.3 | 17.1±3.7 | 16.4±3.4 | |||||

| Baclofen (n = 6) | ||||||||||

| Bladder contraction interval, min | 0.52±0.12 | 0.69±0.16 | 0.74±0.18 | 0.70±0.16 | 1.03±0.25 | |||||

| Bladder amplitude, cmH2O | 25.1±3.4 | 17.2±2.8 | 17.7±4.7 | 18.2±3.5 | 9.9±1.2† | |||||

| Bladder baseline pressure, cmH2O | 15.1±1.3 | 14.2±2.0 | 13.5±2.1 | 13.5±1.1 | 13.3±1.4 | |||||

| Urethral pressure change, cmH2O | 16.6±3.1 | −2.2±5.3† | −13.4±4.2† | −9.9±4.0† | −5.2±1.4† | |||||

| Urethral baseline pressure, cmH2O | 18.2±1.7 | 18.9±2.4 | 14.4±2.7 | 13.7±0.9 | 11.0±0.6† | |||||

Values are means ± SE; n, no. of animals. Significant differences compared with before application (control):

P < 0.05 and

P < 0.01.

Changes in bladder and urethral activity after intrathecal injection of baclofen (0.001–1 μg) in SCT rats (n = 6).

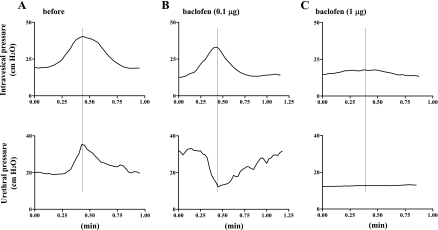

DSD was detected in all of six SCT rats examined (Fig. 2A). Intrathecal injection of baclofen (0.001–1 μg) significantly decreased urethral pressure during isovolumetric bladder contractions, and a change to detrusor-sphincter synergy was detected at 0.001–0.1 μg of baclofen without significantly affecting bladder contraction amplitude (Table 1, Fig. 2B). Intrathecal injection of baclofen at 1 μg then induced a significant reduction in the amplitude of bladder contractions, which was associated with almost complete disappearance of urethral pressure changes during bladder contractions (Table 1, Fig. 2C). The baseline urethral pressure was also significantly decreased by intrathecal injection of 1 μg baclofen, while the interval between isovolumetric bladder contractions or the baseline bladder pressure was not altered by intrathecal injection of baclofen at any doses (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Isovolumetric cystometry and urethral pressure in a SCT rat before (A) and after intrathecal application of 0.1 μg (B) and 1 μg of baclofen (C). A: increases in urethral pressure during bladder contractions indicative of DSD were recorded before drug application. B: after intrathecal baclofen (0.l μg), urethral pressure responses during bladder contractions were changed to a synergic pattern, as evidenced by a negative shift of urethral pressure during bladder contractions. C: after intrathecal baclofen (1 μg), bladder contraction amplitude was decreased, and changes in urethral pressure became negligible.

Changes in bladder and urethral activity after intrathecal application of GABA antagonists in SCT rats.

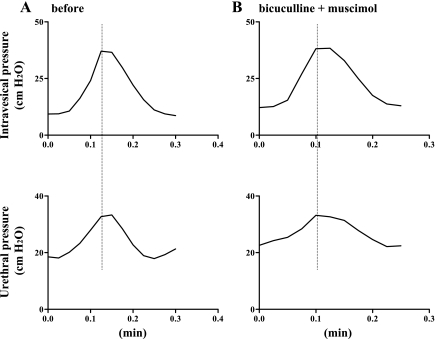

When bicuculline (0.01 μg) was applied intrathecally before muscimol (0.01 μg) in four SCT rats exhibiting DSD (Fig. 3A), bladder or urethral parameters were not altered by bicuculline or subsequent administration of muscimol (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Isovolumetric cystometry and urethral pressure in a SCT rat before (A) and after intrathecal application of bicuculline (0.01 μg) followed by muscimol (0.01 μg) (B). A: increases in urethral pressure during bladder contractions indicative of DSD were recorded before drug application. B: after intrathecal application of bicuculline (0.0l μg) followed by muscimol (0.01 μg), the DSD pattern of urethral pressure during bladder contractions was not changed.

In another group of SCT rats with DSD (n = 4) (Fig. 4A), intrathecal application of saclofen (1 μg) followed by baclofen (0.01 μg) did not affect any bladder or urethral parameters (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Isovolumetric cystometry and urethral pressure in a SCT rat before (A) and after intrathecal application of saclofen (1 μg) followed by baclofen (0.01 μg) (B). A: increases in urethral pressure during bladder contractions indicative of DSD were recorded during isovolumetric bladder contractions. B: after intrathecal application of 1 μg of saclofen followed by baclofen (0.0l μg), the DSD pattern of urethral pressure during bladder contractions was still observed.

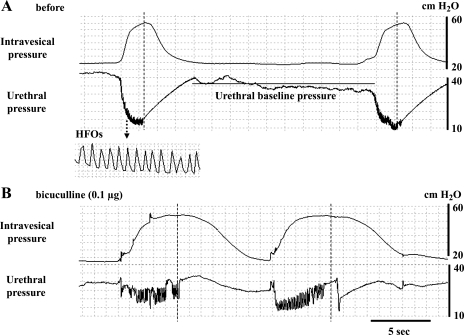

Changes in bladder and urethral activity after intrathecal application of GABAA or GABAB antagonists in spinal-intact rats.

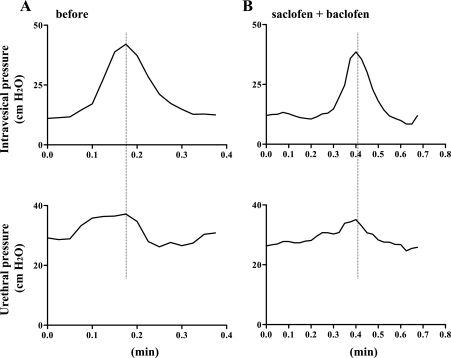

Intrathecal injection of bicuculline (0.1 μg) significantly shortened the interval of isovolumetric bladder contractions, but did not affect the amplitude of bladder contractions (Table 2). Synergic urethral relaxation with HFOs was observed during isovolumetric bladder contractions before drug application (Fig. 5A). However, urethral relaxation during isovolumetric bladder contractions was significantly reduced after intrathecal injection of bicuculline (0.1 μg), as demonstrated by a reduction in urethral relaxation at the peak of bladder contractions from −18.4 ± 3.5 to −9.2 ± 2.8 cmH2O (Table 2, Fig. 5B). The amplitude of HFOs was also significantly increased, but the baseline urethral pressure or the mean rate of HFOs was not affected by intrathecal injection of bicuculline (0.1 μg) (Table 2). In contrast, intrathecal injection of saclofen (1 μg) did not affect any parameters of bladder or urethral activity (Table 2). The mean value of baseline bladder contraction intervals was greater in the bicuculline-treated group compared with the saclofen-treated group (1.72 vs. 0.99 min), because they varied among spinal-intact rats (Table 2). Thus one might argue that the negative effects of saclofen on bladder contraction intervals might be due to the shorter predrug value in the saclofen group. However, the range of baseline bladder contraction intervals was 1.10–2.58 and 0.80–1.16 min in the bicuculline and saclofen groups, respectively, and, in the bicuculline-treated group, the reduction in bladder contraction intervals was consistently observed in all rats, including those (n = 2) with short baseline intervals (1.10 and 1.14 min). Thus it seems unlikely that the difference in the mean value of predrug bladder contraction intervals contributed to the negative results in the saclofen group.

Table 2.

Changes in bladder pressure and urethral pressure after intrathecal administration of bicuculline and saclofen in spinal-intact rats

|

Bicuculline (n = 5) |

Saclofen (n = 4)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After (0.1 μg) | Before | After (1 μg) | |

| Bladder contraction interval, min | 1.72±0.36 | 0.94±0.14* | 0.99±0.07 | 0.87±0.11 |

| Bladder amplitude, cmH2O | 35.0±2.9 | 36.7±2.5 | 32.2±3.2 | 33.5±3.5 |

| Bladder baseline pressure, cmH2O | 21.6±0.8 | 21.6±1.7 | 24.1±2.7 | 26.9±1.9 |

| Urethral baseline pressure, cmH2O | 28.1±1.9 | 29.0±2.8 | 29.9±2.8 | 29.2±3.3 |

| Urethral pressure change, cmH2O | −18.4±3.5 | −9.2±2.8* | −12.4±0.7 | −13.1±1.3 |

| Amplitude of HFOs, cmH2O | 4.1±1.5 | 8.6±1.9* | 5.4±0.6 | 5.6±0.7 |

| Frequency of HFOs, Hz | 5.25±0.25 | 4.75±0.48 | 4.80±0.49 | 5.60±0.25 |

Values are means ± SE; n, no. of animals. HFOs, high-frequency oscillations. Significant differences compared with before application:

P < 0.05.

Fig. 5.

Simultaneous recordings of isovolumetric bladder contractions and urethral pressure before (A) and after intrathecal injection of bicuculline (B) in a spinal-intact rat. A: urethral relaxation during bladder contractions also exhibits small amplitude of high-frequency oscillations (HFOs). B: after intrathecal application of 0.l μg of bicuculline, urethral relaxation at the peak of bladder contractions was decreased. During incomplete urethral relaxation, the amplitude of HFOs was also increased.

DISCUSSION

The results of the present study indicate that intrathecal application of muscimol or baclofen decreases urethral pressure elevation during bladder contractions and changes a pattern from DSD to detrusor-sphincter synergy in SCT rats. These effects were apparently mediated by GABAA and GABAB receptors, since the actions of muscimol and baclofen were completely suppressed by the selective antagonists bicuculline and saclofen, respectively.

The lowest effective dose to inhibit urethral activity in SCT rats was 0.01 μg for muscimol and 0.001 μg for baclofen, and the reversal from DSD to a synergistic pattern (i.e., urethral relaxation during bladder contractions) was 0.1 μg muscimol and 0.001–0.1 μg baclofen. These doses of muscimol and baclofen did not significantly affect bladder contraction pressure. However, when the highest dose (1 μg) of muscimol or baclofen was injected, bladder contraction pressure was significantly decreased, and at the same time urethral pressure changes during isovolumetric bladder contractions almost disappeared. Thus it is assumed that muscimol and baclofen, which activate GABAA and GABAB receptors, respectively, in the spinal cord, initially suppress reflex urethral activity at low doses and then reflex bladder activity at higher doses in SCT rats. In cats, neurons in the pontine micturition center (PMC) directly project to glycine/GABA immunoreactive interneurons in the sacral cord, whereas motoneurons in the Onuf's nucleus that innervate the external urethral or anal sphincters receive GABAergic innervation (1, 19). Therefore, it is assumed that activation of PMC neurons during micturition can suppress urethral sphincter contractions via stimulation of GABAergic interneurons, and that a loss of this PMC-induced activation of the inhibitory GABA system after spinal cord injury can lead to DSD. Thus, in this study, GABA-receptor-mediated suppression of urethral activity and DSD after SCT, especially at low doses of the agonists, is likely to be due to direct inhibition of lumbosacral motoneurons innervating the external urethral sphincter. It has also been reported that a parasympathetic nitric oxide-mediated urethral smooth muscle relaxation is preserved in chronic spinalized female rats (10). Therefore, urethral relaxation of SCT rats after GABA-receptor activation in the present study may have been due to reemergence of masked nitric oxide-mediated urethral smooth muscle relaxation by inhibiting the tonic motor outflow to the striated muscle of the external urethral sphincter following spinal cord injury. In addition, in the present study, intrathecal application of baclofen, but not muscimol, decreased urethral baseline pressure, suggesting that GABAB-receptor activation also affects baseline urethral activity after spinal cord injury.

It is well known that two types of afferent fibers, namely Aδ and C fibers, carry sensory information from the bladder to the spinal cord (11, 12). In cats and rats, Aδ-fiber bladder afferents trigger the normal micturition reflex via a long latency supraspinal reflex pathway passing through the PMC (4, 12). In chronic spinalized rats, C-fiber afferents appear to contribute to bladder hyperreflexia during filling, although Aδ bladder afferents still trigger the voiding reflex, because C-fiber desensitization induced by systemic capsaicin pretreatment reportedly suppresses nonvoiding bladder contractions induced by bladder distention without affecting voiding bladder contractions in spinalized rats (2, 3). Our laboratory's previous study has shown that hyperexcitability of C-fiber bladder afferents is involved, at least in part, in the emergence of DSD during voiding in spinal cord injury, because C-fiber desensitization by capsaicin pretreatment significantly reduced urethral contraction pressure during bladder contractions in SCT rats (17). Our recent study also demonstrated that GABAB-receptor activation by intrathecal application of low doses of baclofen (0.01–0.1 μg) preferentially inhibited C-fiber-mediated nonvoiding bladder contractions before suppressing Aδ-fiber-mediated voiding contractions in SCT rats (14), which is similar to that seen when desensitizing C-fiber afferents by systemic capsaicin treatment in chronic spinalized rats (2, 3). Thus it seems reasonable to assume that GABAB-receptor activation initially inhibits detrusor overactivity by suppressing C-fiber bladder afferents before affecting the efferent limb of the micturition reflex (i.e., reduction in maximal voiding pressure). Taken together, these findings suggest that inhibition of DSD by GABAB-receptor activation might be attributable, not only to direct suppression of Onuf's nucleus motoneurons, but also to inhibition of C-fiber bladder afferent activity, which is enhanced and triggers DSD after spinal cord injury (4, 17).

Our previous study also revealed that chronic spinalized rats exhibiting detrusor overactivity during continuous cystometry had lower levels of glutamate acid decarboxylase, the GABA synthesis enzyme, in the L6-S1 dorsal root ganglia and lumbosacral spinal cord compared with spinal-intact rats, suggesting decreased activity of spinal GABAergic inhibitory mechanisms after spinal cord injury (14). In the present study, bicuculline, a GABAA-receptor antagonist, increased the frequency of isovolumetric bladder contraction and reduced urethral relaxation during bladder contractions in spinal-intact rats, suggesting that, under the normal condition, GABAA-receptor activation during the micturition reflex inhibits bladder contraction frequency and maintains synergic urethral relaxation. In addition, intrathecal bicuculline increased the amplitude of HFOs in spinal-intact rats. HFOs are induced by rhythmic contractions of the striated urethral sphincter that contribute to pumping activity of the urethra, which facilitates urinary flow and increases voiding efficiency in some species, such as rats and dogs (5). Following spinal cord injury, this external urethral sphincter bursting activity during voiding is converted to a tonic activity (10). Increased amplitude of urethral HFOs by bicuculline in spinal-intact rats implies increased activation of striated urethral sphincter muscles during bladder contractions after GABAA-receptor inhibition. Therefore, exciting external urethral sphincter activity during voiding may be tonically inhibited by GABAA mechanisms. Thus decreased activation of GABAA receptors due to hypofunction of spinal GABAergic inhibitory mechanisms might contribute to the emergence of DSD (i.e., decreased urethral relaxation and increased urethral striated muscle activity) after spinal cord injury. In contrast, intrathecal saclofen did not affect bladder or urethral activity in spinal-intact rats, suggesting that GABAB receptors are not tonically active to modulate the micturition reflex under normal conditions.

Previous clinical studies have demonstrated that the GABAB-receptor agonist baclofen administered intrathecally or intravenously reduces urethral resistance in humans with traumatic paraplegia and severe spasticity (6, 20). In the present study, GABA receptor activation in the spinal cord inhibited both bladder and urethral activity in SCT animals. Therefore, GABA-receptor activation could be effective for the treatment of voiding disorders, such as urinary frequency, incontinence, and DSD in spinal cord injury.

Perspectives and significance.

This study provides evidence that activation of GABAA and GABAB receptors in the spinal cord inhibits DSD in SCT rats. Blockade of GABAA receptor induced DSD-like changes in spinal-intact rats, suggesting that hypofunction of GABAergic mechanisms in the spinal cord is partly involved in the genesis of DSD. Therefore, activation of GABAergic mechanisms in the spinal cord may be a promising approach for the treatment of DSD in spinal cord injury.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK57267, DK68557, HD39768, and P01 DK44935.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blok BF, de Weerd H, Holstege G. The pontine micturition center projects to sacral cord GABA immunoreactive neurons in the cat. Neurosci Lett 233: 109–112, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng CL, Ma CP, de Groat WC. Effect of capsaicin on micturition and associated reflexes in chronic spinal rats. Brain Res 678: 40–48, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng CL, Liu JC, Chang SY, Ma CP, de Groat WC. Effect of capsaicin on the micturition reflex in normal and chronic spinal cord-injured cats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 277: R786–R794, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Groat WC, Yoshimura N. Mechanisms underlying the recovery of lower urinary tract function following spinal cord injury. Prog Brain Res 152: 59–84, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Groat WC, Booth AM, Yoshimura N. Neurophysiology of micturition and its modification in animal models of human disease. In: The Autonomic Nervous System, Nervous Control of the Urogenital System, edited by Maggi CA. London: Hartwood Academic, 1993, vol. 3, p. 227–290.

- 6.Hachen HJ, Krucker V. Clinical and laboratory assessment of the efficacy of baclofen (Lioresal) on urethral sphincter spasticity in patients with traumatic paraplegia. Eur Urol 3: 237–240, 1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hisamitsu T, de Groat WC. The inhibitory effect of opioid peptides and morphine applied intrathecally and intracerebroventricularly on the micturition reflex in the cat. Brain Res 298: 51–65, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holstege G, Griffiths D, de Wall H, Dalm E. Anatomical and physiological observations on supraspinal control of bladder and urethral sphincter muscles in the cat. J Comp Neurol 250: 449–461, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Igawa Y, Mattiasson A, Andersson KE. Effects of GABA-receptor stimulation and blockade on micturition in normal rats and rats with bladder outflow obstruction. J Urol 150: 537–542, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kakizaki H, de Groat WC. Reorganization of somato-urethral reflexes following spinal cord injury in the rat. J Urol 158: 1562–1567, 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keast JR, de Groat WC. Segmental distribution and peptide content of primary afferent neurons innervating the urogenital organs and colon of male rats. J Comp Neurol 319: 615–623, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mallory B, Steers WD, de Groat WC. Electrophysiological study of micturition reflexes in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 257: R410–R421, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyazato M, Sugaya K, Nishijima S, Kadekawa K, Ashimine S, Ogawa Y. Intrathecal or dietary glycine inhibits bladder and urethral activity in rats with spinal cord injury. J Urol 174: 2397–2400, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miyazato M, Sasatomi K, Hiragata S, Sugaya K, Chancellor MB, de Groat WC, Yoshimura N. GABA receptor activation in the lumbosacral spinal cord decreases detrusor overactivity in spinal cord injured rats. J Urol 179: 1178–1183, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishizawa O, Igawa Y, Satoh T, Yamashiro S, Sugaya K. Effects of glutamate receptor antagonists on lower urinary tract function in conscious unanesthetized rats. Adv Exp Med Biol 462: 275–281, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogawa T, Seki S, Masuda H, Igawa Y, Nishizawa O, Kuno S, Chancellor MB, de Groat WC, Yoshimura N. Dopaminergic mechanisms controlling urethral function in rats. Neurourol Urodyn 25: 480–489, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seki S, Sasaki K, Igawa Y, Nishizawa O, Chancellor MB, de Groat WC, Yoshimura N. Suppression of detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia by immunoneutralization of nerve growth factor in lumbosacral spinal cord in spinal cord injured rats. J Urol 171: 478–482, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shapiro S Neurotransmission by neurons that use serotonin, noradrenaline, glutamate, glycine, and γ-aminobutyric acid in the normal and injured spinal cord. Neurosurgery 40: 168–176, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sie JA, Blok BF, de Weerd H, Holstege G. Ultrastructural evidence for direct projections from the pontine micturition center to glycine-immunoreactive neurons in the sacral dorsal gray commissure in the cat. J Comp Neurol 429: 631–637, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steers WD, Meythaler JM, Haworth C, Herrell D, Park TS. Effects of acute bolus and chronic continuous intrathecal baclofen on genitourinary dysfunction due to spinal cord pathology. J Urol 148: 1849–1855, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yokoyama O, Mita E, Akino H, Tanase K, Ishida H, Namiki M. Roles of opiate in lower urinary tract dysfunction associated with spinal cord injury in rats. J Urol 171: 963–967, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]