Abstract

Simultaneous inhibition of the retrotrapezoid nucleus (RTN) and raphe obscurus (ROb) decreased the systemic CO2 response by 51%, an effect greater than inhibition of RTN (−24%) or ROb (0%) alone, suggesting that ROb modulates chemoreception by interaction with the RTN (19). We investigated this interaction further by simultaneous dialysis of artificial cerebrospinal fluid equilibrated with 25% CO2 in two probes located in or adjacent to the RTN and ROb in conscious adult male rats. Ventilation was measured in a whole body plethysmograph at 30°C. There were four groups (n = 5): 1) probes correctly placed in both RTN and ROb (RTN-ROb); 2) one probe correctly placed in RTN and one incorrectly placed in areas adjacent to ROb (RTN-peri-ROb); 3) one probe correctly placed in ROb and one probe incorrectly placed in areas adjacent to RTN (peri-RTN-ROb); and 4) neither probe correctly placed (peri-RTN-peri-ROb). Focal simultaneous acidification of RTN-ROb significantly increased ventilation (V̇e) up to 22% compared with baseline, with significant increases in both breathing frequency and tidal volume. Focal acidification of RTN-peri-ROb increased V̇e significantly by up to 15% compared with baseline. Focal acidification of ROb and peri-RTN had no significant effect. The simultaneous acidification of regions just outside the RTN and ROb actually decreased V̇e by up to 11%. These results support a modulatory role for the ROb with respect to central chemoreception at the RTN.

Keywords: control of breathing, serotonin, brain stem

hypercapnia elicits a number of compensatory responses in a wide variety of animal species, such as an increased ventilatory response and a reduced body temperature (3, 23, 24). Central chemoreceptors that detect changes in CO2/pH and regulate breathing are located in the brain stem close to the surface of the ventral medulla (9, 10, 16, 20, 21, 34) and in other locations widely distributed within the brain stem (6, 9, 10, 18, 23, 24, 26, 33, 34, 36), including the serotonergic neurons of the medullary raphe (MR; raphe magnus, pallidus, and obscurus) (2, 8, 11, 12, 25, 29, 33, 34, 42) and glutamatergic neurons of the retrotrapezoid nucleus (RTN) that express the transcription factor Phox2b (1, 7, 10, 17, 18, 22, 26, 30, 35, 39).

Some studies have demonstrated the effects in vivo of focal tissue acidification into the MR. Bernard et al. (2) have shown that the microinjection of acetazolamide (carbonic anhydrase inhibitor) into the MR of anesthetized rats increases the amplitude of the phrenic nerve discharge. In addition, CO2 microdialysis into MR increases ventilation in conscious rats (25) and goats (11). However, these studies have investigated predominantly the rostral MR (magnus and pallidus), and no data exist about the effects of focal tissue acidification into the raphe obscurus (ROb) in vivo.

Recently, the ROb and RTN were studied simultaneously to investigate the relative importance of the RTN and MR in the central chemoreception (19). To this end, simultaneous inhibition was performed using microdialysis of muscimol (GABAA receptor agonist) into the RTN and the serotonin (5-HT1A) receptor agonist (R)-(+)-8-hydroxy-2(di-n-propylamino)tetralin (8-OH-DPAT) into the ROb. Inhibition of RTN neurons with muscimol caused hypoventilation and reduced the ventilatory response to CO2. Inhibition of caudal MR serotonergic neurons with 8-OH-DPAT had no significant effect on the CO2 response, but simultaneous inhibition of the ROb and the RTN produced an enhanced hypoventilation and a greater reduction of the CO2 response (19). These data suggest that the caudal MR does not by itself contribute to chemoreception directly but may modulate breathing by interaction with RTN.

The goal of the present study was to investigate the interaction between ROb and RTN by studying the responses to focal stimulation of these two sites in conscious rats during wakefulness by using reverse microdialysis of artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) equilibrated with 25% CO2.

METHODS

General methods.

All experimentation procedures and protocols were within the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health for animal use and care and were approved by the Dartmouth College Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee.

Surgery.

Experiments were performed on adult male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 280–350 g. Animals were submitted to general anesthesia by intramuscular administration of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (20 mg/kg). The head and a portion of the abdomen were shaved, and the skin was sterilized with betadine solution and alcohol. Rats were fixed in a Kopf stereotaxic frame, and two dialysis guide cannulas (0.38-mm outer diameter) with a dummy were implanted into the medulla. One of them was placed into the caudal medullary raphe (ROb), and the other one was implanted into the RTN. The coordinates for probe placement into the ROb were 4.5 mm from the lambda, in the midline, and 10.4–10.5 mm below the dorsal surface of the skull. The coordinates for RTN were 2.5 mm caudal and 1.8–2.0 mm lateral from the lambda and 10.6 mm below the dorsal surface (32). The guide cannula was secured with cranioplastic cement. Three electroencephalogram (EEG) electrodes were screwed into the right side of the skull, with the frontal electrode 2 mm anterior to bregma and 2 mm lateral to the midline, the parietal electrode 4 mm anterior to lambda and 2 mm lateral to the midline, and the ground electrode between the frontal and parietal electrodes. For the electromyogram (EMG), a pair of wire electrodes was inserted deep into the neck muscle. The skull wound was sutured. The abdominal surface was shaved, the skin was sterilized, an incision was made through the linea alba, and a sterile telemetry temperature probe (TA-F20; Data Sciences, St. Paul, MN) was placed in the abdominal cavity. The incision was closed, and the animal was allowed to recover for 7 days.

CO2 dialysis solution.

The aCSF was equilibrated with 5 or 25% CO2. The composition of the aCSF was (in mM) 152 sodium, 3.0 potassium, 2.1 magnesium, 2.2 calcium, 131 chloride, and 26 bicarbonate. The calcium was added after the aCSF was equilibrated with CO2. The dialysis pump was run at a speed of 40 μl/min.

Ventilation measurement.

The plethysmograph chamber used in these experiments is similar to the setup described by Jacky (14) and Pappenheimer (31). The volume of the plethysmograph was 7.6 liters, with a 3.5-liter top to protect the head pedestal. The analog output of the pressure transducer was converted to a digital signal and directly sampled at 150 Hz by a computer using the DataPac 2000 system. The animal chamber operates at atmospheric pressure, with the inflow and outflow of inspired gases balanced to prevent hyper- or hypobaric conditions in the box. The inflow gas was humidified, and the flow rate was controlled by a flowmeter (model 7491T; Matheson). The outflow port was connected to the in-house vacuum system via a flowmeter. A high-resistance “bleed” of the outflow line provided ∼100 ml/min of outflow gas to the O2 and CO2 analyzers (Applied Electrochemistry). The flow rate through the plethysmograph was maintained at or above 1.4 l/min to prevent CO2 rebreathing. The plethysmograph was calibrated with 0.3-ml injections. Tidal volume (Vt) (14, 24–26, 31) and breathing frequency (f) were calculated per breath to estimate ventilation (V̇e) per breath.

Determination of body temperature.

The chamber temperature was measured by a thermometer inside the chamber. Rat body temperature was measured using the analog output via telemetry from the temperature probe in the peritoneal cavity. These values were used for the calculation of Vt in the whole body plethysmograph.

EEG and EMG signals.

The signals from the EEG and EMG electrodes were sampled at 150 Hz, filtered at 0.3–50 and 0.1–100 Hz, respectively, and recorded directly on the computer with backup on tape. Arousal state was determined by analysis of EEG and EMG records as previously described (24–26).

Anatomical analysis.

At the end of the experiment, the rats were killed by injection of barbiturate, and the brain stems were frozen and then sectioned at 50-μm thickness with a Reichert-Jung cryostat. The sections were counterstained with cresyl violet. We identified anatomical landmarks and the site of dialysis probe placement by using a rat brain atlas (32) for reference. The guide tubes were removed postmortem but before brain stem removal and sectioning. Removal of the guide tubes required manipulation and produced tissue disruption. This facilitated the anatomical verification of guide tube and probe tip location but also increased the volume of tissue disruption compared with that produced by simple insertion.

Experimental protocol.

The rats were initially weighed and then gently held while the dummy cannula was removed and the dialysis probe was inserted into the guide tube. The animals were placed into a plethysmograph chamber and allowed 30–40 min to acclimate. All experiments were performed at ambient temperature (Ta) within the rat thermoneutral zone (30°C). To keep the Ta at ∼30°C, we used a heat lamp with a thermostat controller. Dialysis with 5% CO2-equilibrated aCSF began ∼15 min after the rats were placed in to the chamber. They were dialyzed with 5% CO2 during ∼20 min without any measurement, to allow them to acclimate, and then baseline measurements were made at the end of each 5-min period over the next 20 min by analysis of 200–500 breaths each time. The dialysis solution was then changed to 25% CO2 in both probes, and measurements were made at the end of each 5-min period over 35 min. Time 0 is the estimated time at which the test solution reached the exchange membrane, taking into account the dead space of the dialysis tube and cannula. There were four groups, and rats were placed into each group based on post mortem anatomical localization of dialysis probes. The first group had both probes in the “correct” location: one in the RTN and the other in the ROb. The second group had the RTN probe placed correctly but the ROb probe placed incorrectly, outside of the ROb (RTN-peri-ROb). The third group had the ROb probe placed correctly but the RTN probe placed incorrectly, outside of the RTN (peri-RTN-ROb). We use the terms peri-ROb and peri-RTN to describe the location of probe tips that missed the target; we do not imply any specific anatomical locus by this term. The fourth group had both probes placed incorrectly (peri-RTN-peri-ROb). Each rat received only one dialysis experiment.

Statistics.

We applied a repeated-measures ANOVA with V̇e, Vt, or f as the repeated measure, comparing the absolute values obtained at each of seven measurement periods during the high-CO2 dialysis with absolute values from the four baseline periods for that rat. Because the average body weights differed among the four groups, all data are expressed as percentages of baseline for each 5-min period of high-CO2 dialysis compared with the average of the four baseline values. If there was a significant repeated-measures effect, post hoc comparison of individual time periods vs. baseline was made using Dunnett's test.

RESULTS

Anatomy.

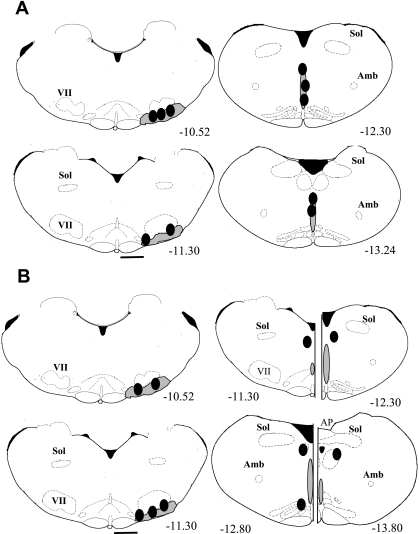

There were 20 (of 49) successful experiments in which all data were obtained and both probe tips were located close to the areas of interest. Figure 1 summarizes the locations of the microdialysis probe tips for the RTN-ROb group (A), with both probe tips correctly placed, and for the RTN-peri-ROb group (B), with probe tips correctly placed in the RTN but incorrectly placed for the ROb. Figure 1A, left, shows schematically that all five probe tips were within the RTN region. The mean distance from bregma for these five probe tips was −10.90 ± 0.19 (SE) mm with a range of −10.52 to −11.5 mm. Figure 1A, right, shows schematically the locations of the probe tips in the ROb. The mean distance from bregma was −12.72 ± 0.30 mm with a range of −12.0 to −13.8 mm.

Fig. 1.

Schematized anatomical cross sections show location of dialysis probe tips (solid ovals) for animals with both tips correctly located in the retrotrapezoid nucleus (RTN; A, left; n = 5) and raphe obscurus (ROb; A, right; n = 5) and for animals with the RTN probe tip correctly located (B, left; n = 5) and the ROb probe tip located incorrectly (peri-ROb; B, right; n = 5). The shaded areas delineate schematically the RTN (below the facial nucleus; left) and the ROb (midline; right). The numbers below the cross sections refer to millimeters caudal to bregma. Scale bar, 1 mm. VII, facial nucleus; Sol, nucleus of the solitary tract; Amb, nucleus ambiguous. The drawings are from the atlas of Paxinos and Watson (32). The actual RTN probe tip locations for A were, relative to bregma: −10.48, −10.52, −10.70, −11.3, −11.5; for ROb: −12.0, −12.3, −12.3, −13.2, −13.8; and the actual RTN probe tip locations for B were, relative to bregma: −10.40, −10.52, −11.00, −11.3, −11.6; for ROb: −11.3, −12.4, −12.8, −13.00, −13.8.

Figure 1B, left, shows schematically that all five probe tips were within the RTN region. The mean distance from bregma for these five probes was −10.96 ± 0.20 mm with a range of −10.40 to −11.6 mm. Figure 1B, right (each panel is split to show 4 levels of probe tip locations), shows schematically the locations of the probe tips incorrectly placed outside of the ROb. The mean distance from bregma was −12.66 ± 0.37 mm with a range of −11.3 to −13.8 mm. These five probe tips were lateral to the midline and dorsal or ventral to the ROb.

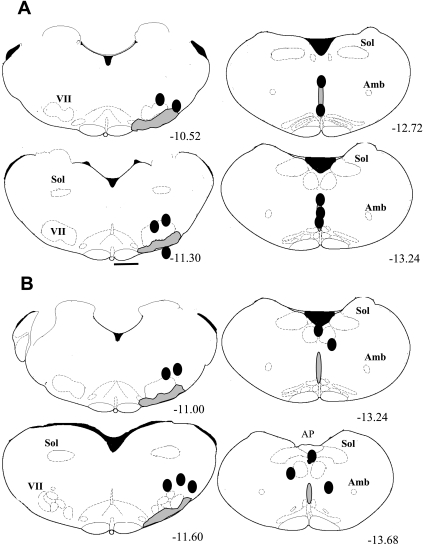

Figure 2 summarizes the locations for the ROb-peri-RTN group (A), with probe tips correctly placed in the ROb but incorrectly placed for the RTN, and for the peri-RTN-peri-ROb group (B), in which probe tips at both sites were incorrectly placed. Figure 2A, left, shows schematically that all five probe tips were outside of the RTN region. Four were well dorsal to the RTN, and one had broken through the ventral medulla. The mean distance from bregma for these probes was −11.07 ± 0.18 mm with a range of −10.58 to −11.46 mm. Figure 2A, right, shows schematically the locations of the probe tips within the ROb. The mean distance from bregma was −13.21 ± 0.17 mm with a range of −12.68 to −13.6 mm. Figure 2B summarizes the locations for the peri-RTN-peri-ROb group, with both sets of probe tips incorrectly placed outside the regions of interest. Figure 2B, left, shows schematically that all five probe tips were outside the RTN region. All were dorsal to the RTN. The mean distance from bregma for these five probes was −11.27 ± 0.14 mm with a range of −10.86 to −11.6 mm. Figure 2B, right, shows schematically the locations of the probe tips outside of the ROb. Three were outside of the midline, and two were dorsal. The mean distance from bregma was −13.5 ± 0.1 mm with a range of −13.24 to −13.7 mm.

Fig. 2.

Schematized anatomical cross sections show location of dialysis probe tips (solid ovals) for animals with probe tips correctly located in the ROb (A, right; n = 5) and incorrectly located in the RTN (peri-RTN; A, left; n = 5) and for animals with both probe tips incorrectly located (peri-RTN: B, left; n = 5; peri-Rob: B, right; n = 5). The numbers below the cross sections refer to millimeters caudal to bregma. Abbreviations are as defined in Fig. 1 legend. The drawings are from the atlas of Paxinos and Watson (32). The actual RTN probe tip locations for A were, relative to bregma: −10.58, −10.60, −11.30, −11.40, −11.46; for Rob: −12.68, −13.00, −13.24, −13.54, −13.60, the actual RTN probe tip locations for B were, relative to bregma: −10.86, −11.00, −11.30, −11.60, −11.6; for Rob: −13.24, −13.30, −13.60, −13.68, −13.70.

Responses to dialysis of the RTN and ROb, simultaneously, with 25% CO2.

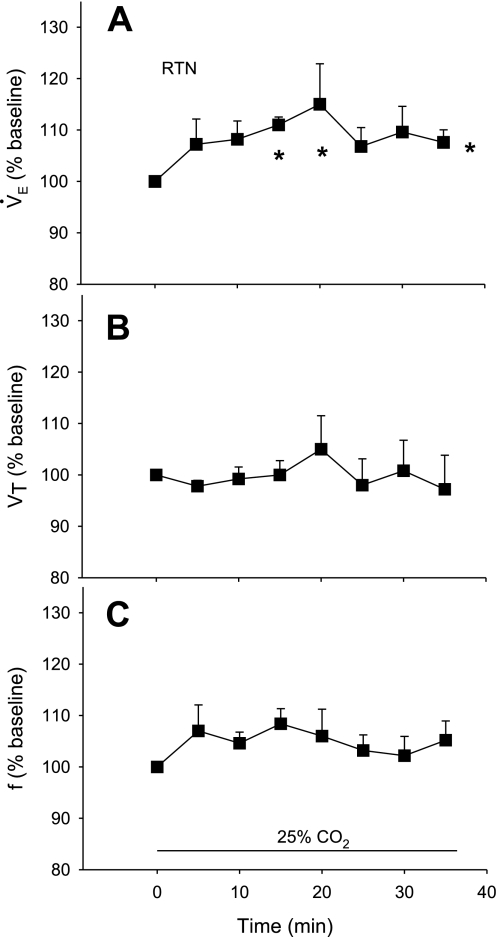

This group (n = 5) had an average body weight of 256 ± 7 g and a body temperature of 37.7 ± 0.1°C. The average values during air breathing were 81 ± 5 min−1 for f, 1.11 ± 0.04 ml/100 g for Vt, and 81 ± 5 ml·min−1·100 g−1 for V̇e. Oxygen consumption was 2.0 ± 0.17 ml·min−1·100 g−1. Figure 3 shows the percent change relative to baseline of V̇e (A), Vt (B), and f (C) resulting from simultaneous 25% CO2 dialysis in the RTN and ROb. V̇e was increased significantly (P < 0.01, repeated-measures ANOVA) with values greater than baseline at 5 (18%), 10 (22%), and 15 min (10%) after onset of dialysis (P < 0.05, post hoc analysis). Vt was increased significantly (P < 0.03, repeated-measures ANOVA) with values greater than baseline at 10 and 15 min after onset of dialysis (P < 0.05, post hoc analysis). Breathing frequency (f) was increased significantly (P < 0.01, repeated-measures ANOVA) with values greater than baseline at 5 and 10 min after onset of dialysis (P < 0.05, post hoc analysis).

Fig. 3.

Ventilatory response to acidification of both the RTN and ROb simultaneously, expressed as a percentage of baseline. Asterisks at far right indicate a significant (P < 0.01) increase as determined by repeated-measures ANOVA on the absolute values for ventilation (A; V̇e), tidal volume (B; Vt), and frequency (C; f). Asterisks at individual time periods indicate a significant (P < 0.05) difference from baseline as determined by post hoc comparison with Dunnett's test.

Responses to dialysis of the RTN region with 25% CO2.

This group (n = 5) had an average body weight of 356 ± 28 g and body temperature of 37.6 ± 0.1°C. The average values during air breathing were 71 ± 4 min−1 for f, 0.89 ± 0.06 ml/100 g for Vt, and 59 ± 4 ml·min−1·100 g−1 for V̇e. Oxygen consumption was 1.9 ± 0.17 ml·min−1·100 g−1. Figure 4 shows the percent change relative to baseline of V̇e, Vt, and f resulting from simultaneous 25% CO2 dialysis in the RTN and peri-ROb. V̇e was increased significantly (P < 0.02, repeated-measures ANOVA) with values greater than baseline at 15 (11%) and 20 min (15%) after onset of dialysis (P < 0.05, post hoc analysis). There was no significant effect on Vt or f.

Fig. 4.

Ventilatory response to acidification of the RTN with simultaneous acidification at sites lying outside the ROb, expressed as a percentage of baseline. The statistics are as in Fig. 3. Asterisk at far right indicates a significant (P < 0.01) increase as determined by repeated-measures ANOVA on the absolute values for V̇e. Asterisks at individual time periods indicate a significant (P < 0.05) difference from baseline as determined by post hoc comparison with Dunnett's test. There was no significant effect on Vt or f.

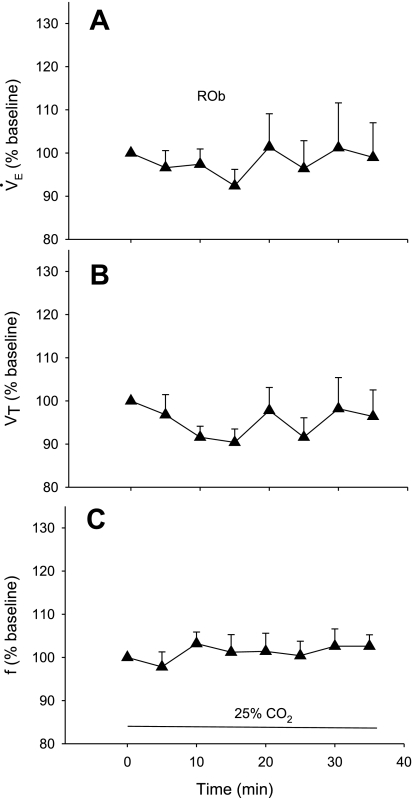

Responses to dialysis of the ROb region with 25% CO2.

This group (n = 5) had an average body weight of 291 ± 19 g and body temperature of 37.7 ± 0.1°C. The average values during air breathing were 71 ± 5 min−1 for f, 1.21 ± 0.09 ml/100 g for Vt, and 83 ± 5 ml·min−1·100 g−1 for V̇e. Oxygen consumption was 2.22 ± 0.17 ml·min−1·100 g−1. Figure 5 shows the percent change relative to baseline of V̇e, Vt, and f resulting from simultaneous 25% CO2 dialysis in the ROb and peri-RTN. There was no significant effect.

Fig. 5.

Ventilatory response to acidification of the ROb with simultaneous acidification at sites lying outside the RTN, expressed as a percentage of baseline. There were no significant effects.

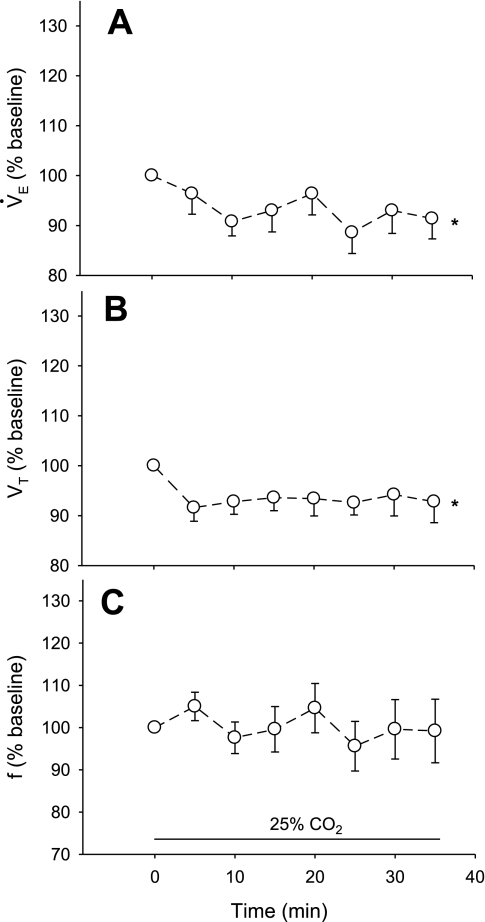

Responses to dialysis with 25% CO2 with both probes incorrectly placed: peri-RTN-peri-ROb.

This group (n = 5) had an average body weight of 269 ± 5 g and body temperature of 37.8 ± 0.1°C. The average values during air breathing were 83 ± 9 min−1 for f, 1.09 ± 0.04 ml/100 g for Vt, and 88 ± 7 ml·min−1·100 g−1 for V̇e. Oxygen consumption was 2.27 ± 0.17 ml·min−1·100 g−1. Figure 6 shows the percent change relative to baseline of V̇e, Vt, and f resulting from simultaneous 25% CO2 dialysis in the peri-RTN and peri-ROb. V̇e and Vt were decreased significantly (P < 0.01, repeated-measures ANOVA). There was no significant effect on f.

Fig. 6.

Ventilatory response to simultaneous acidification at sites lying outside the RTN and the ROb, expressed as a percentage of baseline. Asterisk at far right indicates a significant (P < 0.01) increase as determined by repeated-measures ANOVA on the absolute values for V̇e and Vt. There was no significant effect on f.

DISCUSSION

Experimental design.

In this study we used a chronic, unanesthetized rat model with two preimplanted guide tubes that allowed insertion of dialysis cannulas for subsequent reverse microdialysis in the RTN and ROb using aCSF equilibrated with 25%. The microdialysis cannula (probe) tip has dimensions of 1 mm in length and 0.24 mm in diameter. We perfused the dialysis probe at 40 μl/min, a flow rate necessary to produce the focal acidification as the CO2 that enters the tissue is rapidly cleared by diffusion and blood flow (17). An earlier study evaluated the focal stimulus intensity caused by CO2 dialysis, with a pH electrode adjacent to the dialysis probe located into the RTN. The pH change was relatively small, approximately equivalent to that observed with a 6.6-Torr increase in arterial Pco2 (17).

Focal acidification has been used in individual sites such as the RTN and the medullary raphe to study the role of each in central chemoreception (11, 17, 18, 25, 26). Acidification of the RTN in its rostral portion (18) and the medullary raphe in its rostral portion (raphe magnus) (11, 25) in vivo stimulates respiratory output, indicating that both sites participate in the CO2 response and that each site contains chemosensitivity. It is difficult to determine the functional importance of chemoreceptor sites by using this approach, since in the intact conscious animal, the control system is functional and responsive such that focal stimulation increases ventilation and the resultant hypocapnia inhibits other chemoreceptor sites, including the carotid body, and minimizes the overall increase in V̇e (17). The time course when focal acidification does produce increased V̇e commonly is like that shown in Fig. 5 with an initial increase, followed by a decrease to a level that is still above baseline or control. This time course could be due to an initial excitation of the chemoreceptors at the site of focal acidification, followed by a slower inhibition as other chemoreceptor sites respond to the hypocapnia.

We limited each rat to a single dialysis test with both probes perfused with aCSF equilibrated with 25% CO2 to minimize the tissue disruption or damage caused by the insertion of the dialysis probe. Because of this constraint, the relatively low success rate of placing both probe tips in the desired locations (5 of 20 rats that successfully completed the entire protocol had both correctly placed), and the unexpected observation of an inhibition of V̇e if both probes were incorrectly placed, we decided to use only aCSF equilibrated with 25% CO2 in both probes in all experiments. We found that simultaneous acidification in two probes interfered with the normal sleep cycling that we observe during this type of experiment, so we have reported only data obtained in wakefulness.

Probe placement.

We studied four groups of rats based on post hoc identification of probe tip location: RTN-ROb, with both probes correctly placed; RTN-peri-ROb, with the RTN probe correctly placed and the ROb probe placed outside of the ROb; peri-RTN-ROb, with the RTN probe placed outside of the RTN and the ROb probe correctly placed; and peri-RTN-peri-ROb, with both probes placed incorrectly. For both groups with correct RTN probe placement, the locations in RTN were almost identical (Fig. 1). For both groups with correct probe placement in ROb, the placements in ROb were almost identical (Figs. 1A and 2A). The probes of the group in which were probes were placed outside the regions of interest (Fig. 2B) as well as the incorrectly placed probes in ROb (Fig. 1B) and RTN (Fig. 2A) were clearly not within the two regions of interest but were within 1–2 mm of them.

Inhibition of the CO2 response with both probes incorrectly placed.

An unexpected result was that with acidification of two sites with probes placed just outside the regions of interest, we observed a decrease in V̇e of up to 11%, on average, compared with the initial baseline value. We are uncertain of the source of this inhibition of V̇e, but its presence supports the specificity of the stimulatory responses observed with microdialysis of aCSF equilibrated with 25% CO2 in probes that were correctly placed within the confines of putative central chemoreceptor locations.

High-CO2 dialysis in ROb did not stimulate breathing.

Prior work that used this approach (CO2 microdialysis) in the MR focused on the more rostral part of MR and did show stimulation of V̇e (25). In the present study, with the focal acidification produced more caudally in ROb, there was no stimulation of V̇e relative to baseline. We conclude that there is a heterogeneity of chemoreceptor function within the medullary raphe. Studies of the effects of focal inhibition or lesions within the medullary raphe on the CO2 response support this concept. Lesions of the raphe magnus have large inhibitory effects on the CO2 response (8). Inhibition of raphe 5-HT neurons by dialysis of the 5-HT1A receptor agonist 8-OH-DPAT rostrally inhibits the CO2 response (41), whereas more caudally there is no inhibition (19, 38). Focal stimulation of the medullary raphe electrically (4) or by glutamate injection (2) can have either excitatory or inhibitory effects. Immunohistochemical data have demonstrated that the dorsal part of the ROb contains glutamic acid decarboxylase-immunopositive neurons (5, 13, 15). If these GABAergic neurons are stimulated by the focal acidification, they could contribute to the reduced V̇e response, perhaps directly at the phrenic nucleus (37).

High-CO2 dialysis in the RTN did stimulate breathing.

The RTN probe location provides access to the neurons within the RTN that lie near the surface in the rostral ventrolateral medulla, just beneath the facial nucleus and extending from the rostral part of the facial nucleus to a few hundred micrometers caudally (7, 10, 22, 35). Many studies have demonstrated the importance of the RTN in the control of breathing. In anesthetized animals, focal inhibition or lesions of the RTN causes apnea and severe reductions in CO2 sensitivity (1, 23, 30, 40). In conscious animals, lesions cause decreased breathing and CO2 sensitivity (1, 24), whereas focal acidification stimulate breathing (18). One type of RTN chemoreceptor neuron has been identified as expressing the transcription factor Phox2b as well as being glutamatergic (39).

In prior work, focal 25% CO2 dialysis in the RTN increased V̇e by 24% of baseline during wakefulness (18). This response was bigger than that obtained in the present study, a 15% increase in V̇e compared with baseline. Three factors may account for this difference. First, the microdialysis probes were located in the more rostral region of RTN in the animals of the previous study compared with the location of the probes in the present study. Second, the present experiments were performed at an ambient temperature within the thermoneutral zone of the rats, whereas the earlier study used room temperature, which is below the normal rat thermoneutral zone. The ambient temperature can affect the CO2 response (41). Third, the excitatory response of focal RTN acidification could have been attenuated by any inhibition arising from the simultaneous acidification in the peri-ROb region.

Simultaneous high-CO2 dialysis in RTN and ROb did produce an enhanced breathing response.

Focal acidosis at both the RTN and ROb increased V̇e by 22% compared with baseline, an effect that included increases in both Vt and f. This was greater than observed with focal acidification of either RTN or ROb alone. There are anatomical data that support the interaction between RTN and ROb. Retrograde tracing with neurobiotin injected into the RTN has shown that neurons of ROb were labeled, indicating that RTN has afferent input from ROb (7, 35). Recent data show that the Phox2b-positive putative chemoreceptor neurons in the RTN possess 5-HT receptors and can be excited by local 5-HT application (21). Thus connectivity and receptor presence indicate that ROb 5-HT neurons can affect RTN neurons.

In a previous study, inhibition of RTN neurons with muscimol, with simultaneous dialysis of aCSF (control) in or near the caudal MR (ROb), caused hypoventilation and reduced the V̇e response to 7% CO2 by 24% (19). Inhibition of caudal MR (ROb) serotonergic neurons with the 5-HT1A receptor agonist 8-OH-DPAT, with simultaneous dialysis of aCSF in or near the RTN, caused hypoventilation but had no significant effect on the CO2 response. Inhibition of both the RTN and the caudal MR (ROb) simultaneously produced enhanced hypoventilation and a substantial 51% decrease in the CO2 response (19). These results suggest a modulatory role of caudal medullary raphe, and our present results corroborate this hypothesis.

We conclude that simultaneous focal acidification of both RTN and ROb potentiates the effects of focal acidification of either RTN or ROb alone. This conclusion is apparent despite the unexpected inhibition of the CO2 response observed if both probes were incorrectly located just outside the regions of interest. The mechanism for the potentiation of the response is not known. It possibly occurs as a result of 5-HT-mediated excitation of RTN Phox2b-chemosensitive neurons. As shown by the in vitro data of Mulkey et al. (21), increased 5-HT input to these RTN neurons could enhance their CO2-stimulated output. Such a mechanism could help to explain our results. Corelease of substance P by these 5-HT neurons could also stimulate RTN chemoreceptor neurons as well as other respiratory neurons that possess neurokinin-1 receptors (NK1Rs). Lesions of NK1R-immunoreactive cells in the ventral medulla substantially decreased the CO2 response, indicating their importance in this function (27). Lesions of both NK1R-expressing neurons and processes and 5-HT neurons together in the medullary raphe inhibit the systemic CO2 response to a greater extent than either lesion alone, also suggesting an interaction of 5-HT, substance P, and NK1Rs in central chemoreception (29). In addition, 5-HT neurons in ROb could directly affect respiratory neurons in the pre-Bötzinger complex and the ventral respiratory group via 5-HT and or substance P.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant R37 HL-28066 (to E. Nattie). M. B. Dias was supported by a grant from the Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akilesh MR, Kamper M, Li A, Nattie EE. Effects of unilateral lesions of retrotrapezoid nucleus on breathing in awake rats. J Appl Physiol 82: 469–479, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernard DG, Li A, Nattie EE. Evidence for central chemoreception in the midline raphé. J Appl Physiol 80: 108–115, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Branco LG, Wood SC. Role of central chemoreceptors in behavioral thermoregulation of the toad Bufo marinus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 266: R1483–R1487, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cao Y, Fujito Y, Matsuyama K, Aoki M. Effects of electrical stimulation of the medullary raphe nuclei on respiratory movement in rats. J Comp Physiol A Neuroethol Sens Neural Behav Physiol 192: 497–505, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao Y, Matsuyama K, Fujito Y, Aoki M. Involvement of medullary GABAergic and serotonergic raphe neurons in respiratory control: electrophysiological and immunohistochemical studies in rats. Neurosci Res 56: 322–331, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coates EL, Li A, Nattie EE. Widespread sites of brainstem ventilatory chemoreceptors. J Appl Physiol 75: 5–14, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cream C, Li A, Nattie E. The retrotrapezoid nucleus (RTN): local cytoarchitecture and afferent connections. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 130: 121–137, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dias MB, Nucci TB, Margatho LO, Antunes-Rodrigues J, Gargaglioni LH, Branco LG. Raphe magnus nucleus is involved in ventilatory but not hypothermic response to CO2. J Appl Physiol 103: 1780–1788, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feldman JR, Mitchell GS, Nattie EE. Breathing: rhythmicity, plasticity, chemosensitivity. Annu Rev Neurosci 26: 239–266, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guyenet PG, Stornetta RL, Bayliss DA, Mulkey DK. Retrotrapezoid nucleus: a litmus test for the identification of central chemoreceptors. Exp Physiol 90: 247–253, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hodges MR, Martino P, Davis S, Opansky C, Pan LG, Forster HV. Effects on breathing of focal acidosis at multiple medullary raphe sites in awake goats. J Appl Physiol 97: 2303–2309, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hodges MR, Tattersall GT, Harris MB, McEvoy SD, Richerson DN, Deneris ES, Johnson RL, Chen ZF, Richerson GB. Defects in breathing and thermoregulation in mice with near complete absence of central serotonin neurons. J Neurosci 28: 2495–2505, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holmes CJ, Mainville LS, Jones BE. Distribution of cholinergic, GABAergic and serotonergic neurons in the medial medullary reticular formation and their projections studied by cytotoxic lesions in the cat. Neuroscience 62: 1155–1178, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacky JP A plethysmograph for long-term measurements of ventilation in unrestrained animals. J Appl Physiol 45: 644–647, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kachidian P, Poulat P, Marlier L, Privat A. Immunohistochemical evidence for the coexistence of substance P, thyrotropin-releasing hormone, GABA, methionine-enkephalin, and leucin-enkephalin in the serotonergic neurons of the caudal raphe nuclei: a dual labeling in the rat. J Neurosci Res 30: 521–530, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loeschcke HH Central chemosensitivity and the reaction theory. J Physiol 332: 1–24, 1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li A, Nattie E. CO2 dialysis in one chemoreceptor site, the RTN: stimulus intensity and sensitivity in the awake rat. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 133: 11–22, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li A, Randall M, Nattie EE. CO2 microdialysis in retrotrapezoid nucleus of the rat increases breathing in wakefulness but not in sleep. J Appl Physiol 87: 910–919, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li A, Zhou S, Nattie E. Simultaneous inhibition of caudal medullary raphe and retrotrapezoid nucleus decreases breathing and the CO2 response in conscious rats. J Physiol 577: 307–318, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitchell RA, Loeschcke HH, Massion WH, Severinghaus JW. Respiratory responses mediated through superficial chemosensitive areas on the medulla. J Appl Physiol 18: 523–533, 1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mulkey DK, Rosin DL, West G, Takakura AC, Moreira TS, Bayliss DA, Guyenet PG. Serotonergic neurons activate chemosensitive retrotrapezoid nucleus neurons by a pH-independent mechanism. J Neurosci 27: 14128–14138, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mulkey DK, Stornetta RL, Weston MC, Simmons JR, Parker A, Bayliss DA, Guyenet PG. Respiratory control by ventral surface chemoreceptor neurons in rats. Nat Neurosci 7: 1360–1369, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nattie EE CO2, brainstem chemoreceptors and breathing. Prog Neurobiol 59: 299–331, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nattie EE, Li A. Central chemoreception 2005: a brief review. Auton Neurosci 126–127: 332–338, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nattie EE, Li A. CO2 dialysis in the medullary raphe of the rat increases ventilation in sleep. J Appl Physiol 90: 1247–1257, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nattie EE, Li A. CO2 dialysis in nucleus tractus solitarius region of rat increases ventilation in sleep and wakefulness. J Appl Physiol 92: 2119–2130, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nattie E, Li A. Neurokinin-1 receptor-expressing neurons in the ventral medulla are essential for normal central and peripheral chemoreception in the conscious rat. J Appl Physiol 101: 1596–1606, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nattie EE, Li A. Substance P-saporin lesion of neurons with NK1 receptors in one chemoreceptor site in rats decreases ventilation and chemosensitivity. J Physiol 544: 603–616, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nattie EE, Li A, Richerson G, Lappi DA. Medullary serotonergic neurons and adjacent neurons that express neurokinin-1 receptors are both involved in chemoreception in vivo. J Physiol 556: 235–253, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nattie EE, Li AH, St John WM. Lesions in retrotrapezoid nucleus decrease ventilatory output in anesthetized or decerebrate cats. J Appl Physiol 71: 1364–1375, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pappenheimer J Sleep and respiration of rats during hypoxia. J Physiol 266: 191–207, 1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paxinos G, Watson C. The Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates (4th ed.). San Diego, CA: Academic, 1998.

- 33.Richerson GB Serotonergic neurons as carbon dioxide sensors that maintain pH homeostasis. Nat Rev Neurosci 5: 449–461, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richerson GB, Wang W, Hodges MR, Dohle CI, Diez-Samprado A. Homing in on the specific phenotype(s) of central respiratory chemoreceptors. Exp Physiol 90: 259–266, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosin DL, Chang DA, Guyenet PG. Afferent and efferent connections of the rat retrotrapezoid nucleus. J Comp Neurol 499: 64–89, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Solomon IC, Edelman NH, O'Neal MH 3rd. CO2/H+ chemoreception in the cat pre-Botzinger complex in vivo. J Appl Physiol 88: 1996–2007, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Song G, Aoki M. Projections from brainstem GABAergic neurons to the phrenic nucleus. Adv Exp Med Biol 499: 107–111, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sandeep S, Raddatz E, Liu X, Liu H, Horner RL. Inhibition of serotonergic medullary raphe obscurus neurons suppresses genioglossus and diaphragm activities in anesthetized but not conscious rats. J Appl Physiol 100: 1807–1821, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stornetta RL, Moreira TS, Takakura AC, Kang BJ, Chang DA, West GH, Brunet JF, Mulkey DK, Bayliss DA, Guyenet PG. Expression of Phox2b by brainstem neurons involved in chemosensory integration in the adult rat. J Neurosci 26: 10305–10314, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takakura AC, Moreira TS, Colombari E, West GH, Stornetta RL, Guyenet PG. Peripheral chemoreceptor inputs to retrotrapezoid nucleus (RTN) CO2-sensitive neurons in rats. J Physiol 572: 503–523, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taylor NC, Li A, Nattie EE. Medullary serotonergic neurones modulate the ventilatory response to hypercapnia, but not hypoxia in conscious rats. J Physiol 566: 543–557, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang W, Tiwari JK, Bradley SR, Zaykin AV, Richerson GB. Acidosis-stimulated neurons of the medullary raphe are serotonergic. J Neurophysiol 85: 2224–2235, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]