Abstract

Resolving the mechanisms underlying the temporal and spatial profile of zinc transporter expression in response to zinc availability is key to understanding zinc homeostasis. The mRNA expression of seven zinc transporters was studied in zebrafish gills when treated with zinc deficiency/excess over a 14-day period. Of these, ZnT1, ZnT5, ZIP3, and ZIP10 were differentially expressed in response to changed zinc status. The mRNA level of zinc exporter, ZnT1, was upregulated in fish subjected to excess zinc and downregulated by zinc deprivation. This response was similar to that of metallothionein-2 (MT2). Zinc deficiency caused an increased abundance of mRNA for zinc importers ZnT5, ZIP3, and ZIP10. Expression of ZnT5 and ZIP10, but not ZIP3, was inhibited by excess zinc. Zinc influx function of ZIP10 was demonstrated by 65Zn transport assays in Xenopus oocyte expression experiments, suggesting that the inverse relationship between zinc availability and ZIP10 expression serves to maintain zinc homeostasis. Two distinct transcription start sites (TSS) for ZIP10 were found in gill and kidney. Luciferase assays and mutation/deletion analysis of DNA fragments proximal to the respective TSS revealed that ZIP10 has two alternative promoters (P1 and P2) displaying opposite regulatory control in response to zinc status. Positive as well as negative regulation by zinc involves MRE clusters in the respective promoters. These results provide experimental evidence for MREs functioning as repressor elements, implicating MTF1 involvement in the negative regulation of ZIP10. This is in contrast to the well-established positive regulation by MTF1 of other genes, such as MT2 and ZnT1.

Keywords: metallothionein, metal-regulatory transcription factor-1, metal-response element, transcriptional regulation, SLC30, SLC39

zinc is an essential element fulfilling a catalytic or structural role central to the function of many proteins involved in transcriptional regulation, nucleic acid and protein synthesis, protein trafficking and signaling (2, 5). In humans and other animals, zinc deficiency is related to a wide range of physiological defects including impairment of growth, development, immune system, and neural function (15, 16, 38). However, excessive zinc accumulation is also harmful and can cause impaired neural and immune functions, ultimately leading to hemolytic anemia (14). Toxicity from systemic zinc overload is primarily relevant to fish and other aquatic animals due to direct exposure to elevated concentrations of zinc in water through the gill epithelium. However, cellular zinc toxicity may occur in humans as a consequence of local zinc dysregulation during conditions such as postperfusional ischemia (42). Thus, finely tuned regulatory systems are required to maintain an adequate supply of zinc and prevent zinc overload.

Intracellular zinc is strictly regulated by binding to metallothioneins (MTs) and glutathione and by compartmentalization through the activities of zinc transporters (4). MTs have high binding affinity for zinc and play a central role in maintaining stable intracellular zinc availability through sequestration or release of zinc (19). Zinc transporters are transmembrane proteins, controlling the movement of zinc across cellular and intracellular membranes. Transport of zinc into the cytosol is mediated by members of the slc39 (ZIP) transporter family. There are 14 ZIP transporters discovered in mammals, but only ZIP1–8 and ZIP14 have been experimentally verified to have zinc transporter activity (7, 31). ZIP1–6 and ZIP14 have been shown to increase zinc uptake from extracellular fluid, whereas ZIP7 is believed to mediate movement of zinc from the endoplasmic reticulum into the cytosol. Flux of zinc away from the cytosol, either into organelles or out of the cell, is mediated by members of the slc30 (ZnT) transporter family. Ten members of the ZnT family have been identified in mammals; of these the transporting function of ZnT1–8 has been confirmed directly or by inference (7). ZnT1, the first mammalian zinc transporter discovered (37), is expressed throughout the body, but notable in basolateral membranes of tissues involved in zinc acquisition or recycling like intestine, kidney, and placenta (30, 31). A splice variant of ZnT5 is in mammals located to the apical membrane of enterocytes (8, 9, 23). All other ZnT proteins where cellular localization has been characterized are found in the membranes of organelles (7). Conversely, it is believed that of the slc39 members characterized so far, only ZIP7 is operational in intracellular membranes (7). In the mammalian intestine ZIP4 is located at the apical surface while ZIP5 is found at the basolateral membrane (45).

Transcriptional regulation of MTs and the zinc transporter proteins contributes to the cellular zinc homeostasis. It is well known that MTs are highly induced by zinc, a response mediated by metal-regulatory transcription factor 1 (MTF1) (18). By binding to zinc, the DNA-binding region of MTF1 is activated and can specifically bind to metal-response elements (MREs), which contain a conserved motif 5′-TGCRCNC-3′, on target genes. MT1 and MT2 genes of vertebrate species typically have four to seven MREs in the 5′-regulatory region (28, 35). The mRNA expression of several ZnT members is also differentially regulated upon zinc availability. In rat, the intestinal ZnT1 and ZnT2 mRNA expression levels were increased by high dietary zinc and reduced to very low levels when zinc was deficient (30). The induction of ZnT1 mRNA expression by zinc has also been observed in other studies (10, 33, 34) and explained by the binding of MTF1 to MREs in ZnT1 promoter (29). The human ZnT5 promoter was found to be repressed by zinc excess through a mechanism that does not seem to involve MRE (23). Conversely, the mRNA expression of ZnT5 and ZnT7 was induced by zinc depletion in HeLa cells (10). A higher level of ZnT4 mRNA was detected in mammary gland of rats fed with a low zinc diet (27). Regulation of the slc39 family proteins ZIP4 and ZIP5 has received significant attention during recent years. It has been shown that abundance of ZIP4 mRNA in mouse is increased by zinc deficiency, but this is a caused by an increase in transcript stability and not transcription (12, 45). During zinc excess, ZIP4 mRNA stability is reduced and ZIP4 protein is ubiquitinated and degraded (32, 45). Mouse ZIP5 protein is expressed during zinc excess in basolateral membranes of enterocytes, acinar cells, and endoderm cells (45). The mouse ZIP5 gene seems to be constitutively expressed, and increase of ZIP5 protein in response to zinc is mediated by an increased rate of translation. There is evidence that accumulation of ZIP10 mRNA in mouse may be decreased by cadmium and that the basal expression might be negatively controlled by MTF1 (46). This idea is strongly supported by our own research showing that zinc-induced repression of ZIP10 mRNA accumulation in zebrafish ZF4 cells was completely removed by MTF1 knockdown using siRNA (G. P. Feeney, D. Zheng, C. Hogstrand, and P. Kille, unpublished observation). However, the regulatory mechanisms for most ZnT and ZIP genes remain largely unexplored.

In addition to absorbing zinc from the diet, fish take up zinc across the gills directly from water. It is evident from previous studies that zinc regulation in the fish gill is indeed highly dynamic and efficient (20, 21) and that zinc transporters in fish gill play similar functions as in the intestine of mammals (1, 34, 40, 41). The fish gill is therefore an attractive system to investigate regulation of zinc transporters and with the genomic resources available for zebrafish, this is an experimental organism of choice for molecular studies.

At least eight ZnTs and eleven ZIPs are present in the zebrafish genome and expressed in a tissue-specific manner, and several of these transporters are expressed in the zebrafish gills and may respond to changes in zinc availability (13). In the present study, we selected seven zinc transporters of interest to investigate their mRNA expression in zebrafish gills during a 14-day regime of either zinc deficiency or excess. Of these, four genes (ZnT1, ZnT5, ZIP3, and ZIP10) were confirmed to be differentially expressed at the mRNA level in response to changes in zinc status. Expression of the ZIP10 gene was of particular interest because its mRNA level in the gill was decreased by zinc excess and increased by zinc deficiency. Therefore, we functionally characterized the transcriptional regulation of the ZIP10 gene by zinc.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals and zinc exposure.

The animal care and procedures were performed in accordance with, and with approval given under, the Animal (Scientific Procedures) Act (UK) 1986. Juvenile zebrafish, Danio rerio (0.44 ± 0.06 g, mean ± SD), were obtained from Neil Hardy Aquatica (Surrey, UK). The fish were divided into three experimental groups with each group held in four identical 10-liter polystyrene tanks (40 fish per tank) and supplied with a continuous flow of aerated reconstituted reverse osmosis water at a rate of 50 ml per min and a temperature of 26–28°C. The reconstituted water was composed of 0.6 mM NaCl, 41 μM Na2SO4, 13.6 μM KCl, 150 μM CaCl2, 3.4 μM NaHCO3, 78 μM MgCl2. In addition, each tank was equipped with a dosing system, which added Zn, as ZnSO4·7H2O (BDH Chemicals), from a stock solution (12.5 μM), at a rate of 1 ml per min, resulting in a nominal zinc concentration in the tanks of 0.25 μM. The fish were fed purified flake diets (Fish Nutrition Unit, University of Plymouth, UK) containing normal zinc level (233 mg/kg) twice daily in a total of 4% of their body mass per day before the experiment began.

After 1 wk acclimation to laboratory conditions, the zinc dosing stock solution for a group of four tanks was changed to 20× concentrate, resulting in a nominal zinc concentration in the tanks of 5 μM (zinc excess group), and that for another group of four tanks was removed (zinc deficiency group, [Zn2+] ≈ 0). The feed was replaced with food containing either higher zinc content (2,023 mg/kg) or low zinc (26 mg/kg), respectively. The conditions for the third group of four tanks were maintained as before (control group, [Zn2+] = 0.25 μM). The feeding ration of 4% of the body mass per day, divided into two meals per day, was maintained throughout the experiment. All experimental feeds were well accepted and consumed within 2 min of administration. The zinc concentrations in water from all tanks were monitored daily using inductively coupled plasma mass spectroscopy (ICP-MS; PerkinElmer Elan DRC, King's College London). The actual water zinc concentrations in zinc deficiency, control, and excess groups were 0.04 ± 0.05, 0.25 ± 0.09, and 4.02 ± 1.2 μM (means ± SD, n = 15), respectively. The experiment continued for 14 days, and no mortalities occurred during the exposure period under any condition.

Zinc concentration in tissue.

At 1, 4, 7, and 14 days into the experiment, three fish from each experimental group and three replicate tanks were killed by overdose of benzocaine (Sigma) and gills were removed by dissection. Each tissue sample (5–20 mg) was digested in 500 μl of 50% HNO3 (wt/wt, BDH Biochemicals) at room temperature overnight. Each digestion was then diluted to 5 ml with deionized water, and the zinc content was measured using ICP-MS.

RNA purification and cDNA synthesis.

Gills from nine fish from each group at 1, 4, 7, and 14 days were dissected and immediately put in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C before RNA extraction. Total RNA was extracted from gill samples using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacture's protocol, and any residual genomic DNA was removed using the DNA-Free kit (Ambion). The integrity of RNA samples was assessed using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyser (Agilent Technologies). The first-strand cDNA was synthesized from 2 μg of total RNA using Powerscript reverse transcriptase (Clontech). In brief, total RNA was mixed with 500 ng of oligo(dT)17 and 500 ng of random hexamer, heated at 70°C for 10 min, and then cooled immediately on ice for 2 min. The content was then mixed thoroughly with 4 μl of 5× first-strand buffer, 2 μl of dNTP (10 mM), 2 μl of DTT (100 mM), and 1 unit of reverse transcriptase. The reaction mixture was incubated at 42°C for at least 90 min and subsequently inactivated by heating at 70°C for 15 min.

Real-time quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction.

The oligonucleotide primers and TaqMan probes (Qiagen) for each gene were designed using Primer Express (Applied Biosystems) and are listed in Table 1. Nomenclature for zebrafish zinc transporters is that of Feeney et al. (13). The expression of gene MT2, ZnT1, ZnT2, ZIP1 and ZIP7 was measured using Taqman assays, and the expression of gene ZnT5, ZIP3, and ZIP10 was measured using SYBR green assays. The TaqMan reaction was performed in a final volume of 20 μl containing 20 mM Tris·HCl, 50 mM KCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 250 nM of dNTP, 1.25 U of Taq polymerase, 1 μM ROX (reference dye, Applied Biosystems) and corresponding primers and probes with optimal concentrations. The SYBR Green assays were set up using the SYBR green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's protocol except that a 20 μl reaction volume was used. The quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) assays were performed on ABI prism 7000 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) with cycling conditions as follows: 5 min of denaturation at 95°C and then 40 cycles of 95°C for 30s, 60°C for 1 min. The standard curve was generated using series of dilution of a concentrated cDNA mixture. The relative copy number was deduced from the corresponding cycle threshold. To correct the input RNA concentration, the relative gene copies were further normalized to the measurement for 18s whose transcript has previously been established to be the least variable over a range of zinc conditions (P. A. Walker, unpublished observation). Data shown are the average of measurements from nine fish per group at each time point and expressed as fold-change relative to the control at the same time point.

Table 1.

Sequence of primers and probes used in real-time PCR assays

| Gene Name | Forward (5′→3′) | Reverse (5′→3′) | Taqman Probe (FAM-5′→3′) | Amplicon Size, bp | Assay Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MT2 | AATGGACCCCTGCGAAT | GGTAGCACCACAGTTGCAA | TGCCAAGACTGGAA | 52 | Taqman |

| ZnT1 | AGTGCCCGAGCAGATCGA | GCTAGAACTCCATCCAGGCTCTT | TGCCCAAGCTGAAAG | 66 | Taqman |

| ZnT2 | AGTGATGGTGGCTGCTATTATAATCT | GTGCAAATGGGATCGGCTAT | TTCAGGCCAGAATACA | 66 | Taqman |

| ZnT5 | ACCAGATGGAAAGCAACAAGGA | GTCTGTGTTGATGTTCGGTGGAT | 156 | SYBR green | |

| ZIP1 | GCTTGCAGACGACGAATGC | TGAACACGATGATGCTCTTGTG | AGGTGTTAGAGATCTGC | 75 | Taqman |

| ZIP3 | GCCCAAATATCTGACGGACATG | GCTCAATCAGCGTCTGCTTCTC | 182 | SYBR green | |

| ZIP7 | GGAGGACATTCACACTCGCATT | TCTTCATCACTATCCTTTGACTTTGG | CCACTCTCCCTCTGC | 65 | Taqman |

| ZIP10 | GAAGAAAGGAGAGCAGGCAAAGA | GAGGCTGCAATTCTGTCATCTGA | 161 | SYBR green | |

| 18S | CGGAGGTTCGAAGACGATCA | CGGGTCGGCATCGTTTAC | ATACCGTCGTAGTTCCG | 59 | Taqman |

Gene nomenclature is that of Feeney et al. (13).

Bioinformatics analysis.

In the present study, the full ZIP10 gene sequence was based on the ZIP10 gene (ENSDARG00000005823) collected from the Ensembl zebrafish assembly version, Zv6 (www.ensembl.org/index.html). The genomic sequences of ZIP10 genes from human (ENSG00000196950), mouse (ENSMUSG00000025986), and fugu (SINFRUG00000120982) were also obtained from Ensembl. The MRE core consensus, 5′-TGCRCNC-3′, was searched within 2 kb upstream of both the transcriptional start site (TSS) and the translational start site using the “find pattern” routine in the GCG Wisconsin package. Comparative genomics analysis was carried out with tools available at www.dcode.org. Evolutionary conserved regions (ECR) in ZIP10 were identified using the ECR browser with zebrafish as base organism and the chromosomal location of ZIP10 provided according to Ensembl Zv6. Identified ECR were searched for conserved transcription factor binding sites using the rVISTA 2.0 program.

5′-RNA ligase-mediated rapid amplification of cDNA 5′-ends.

To determine the TSS of ZIP10 gene, the 5′-cDNA end of ZIP10 was amplified using the FirstChoice RLM-RACE kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Briefly, the total RNA obtained from gill and kidney samples was treated by calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase, which removes free 5′-phosphates from fragmented mRNA, rRNA, tRNA, and genomic DNA. After being purified by phenol-chloroform extraction and alcohol precipitation, the RNA was then treated with tobacco acid pyrophosphatase to remove the cap structure from full-length mRNA. A 45-base RNA adaptor oligonucleotide was then ligated to the RNA using T4 RNA ligase and RNA reverse transcribed into cDNA using random primer. The 5′-end of ZIP10 was amplified by two-round nested PCR with gene-specific primers (GSP1, 5′-TCGATGGGCTTTGACCTTAG-3′ and GSP2, 5′-CTGTCTTGCTTGTGACTGTGTG-3′) and two adaptor-specific primers [5′-rapid amplification of cDNA 5′-ends (RACE) outer primer and inner primer provided in the kit]. The cDNA fragment sequence was confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Plasmid construction and site-directed mutagenesis.

The promoter fragments P1, P1F1, and P1F2 were amplified from zebrafish genomic DNA using a forward primer, 5′-TGCTACAACTCTCTGCAATAGGC-3′ and a reverse primer, 5′-CCATGTTGTGGGAGTGTG TG-3′ (P1), 5′-AAAACACTCACGCTGCGCA C-3′ (P1F1) or 5′-CAAAACTCAGAGCCCACTG C-3′ (P1F2), respectively. The promoter fragment P2, immediately upstream of ZIP10 exon 2, was amplified using primers 5′-CATCCTATTTTTAG AAGTCTCCTAGT-3′ and 5′-CTCCTCTCTTAGACACCTCTGC-3′. The PCR fragments were then cloned into the pCRII plasmid using TOPO cloning kit (Invitrogen) and further inserted into pGL3-basic plasmid (Promega), immediately upstream of a luciferase gene. The correct plasmid constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing. The plasmid constructs used are listed in Table 2 and illustrated in Fig. 3.

Table 2.

Plasmid constructs used in this study and their descriptions

| Plasmid Name | Description |

|---|---|

| pGL3-basic | vector lacking eukaryotic promoter & enhancer sequences upstream of a firefly luciferase gene (Promega) |

| pRL-TK | vector containing herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase promoter providing low to moderate levels of Renilla luciferase expression (Promega) |

| pGL3-P1 | pGL3-basic vector inserted with ZIP10 promoter P1 containing a full 5′-UTR |

| pGL3-P1F1 | pGL3-basic vector inserted with ZIP10 promoter P1 lacking MRE2 from 3′-end |

| pGL3-P1F2 | pGL3-basic vector inserted with ZIP10 promoter P1 lacking both MRE1 and MRE2 from 3′-end |

| pGL3-P2 | pGL3-basic vector inserted with ZIP10 wild-type promoter P1 |

| pGL3-P2m1 | pGL3-basic vector inserted with ZIP10 promoter P2 carrying mutations in the MRE1′ site |

| pGL3-P2m2 | pGL3-basic vector inserted with ZIP10 promoter P2 carrying mutations in the MRE2′ site |

| pGL3-P2m3 | pGL3-basic vector inserted with ZIP10 promoter P2 carrying mutations in the MRE3′ site |

| pGL3-P2m12 | pGL3-basic vector inserted with ZIP10 promoter P2 carrying mutations in both MRE1′ and MRE2′ sites |

| pGL3-P2m13 | pGL3-basic vector inserted with ZIP10 promoter P2 carrying mutations in both MRE1′ and MRE3′ sites |

| pGL3-P2m23 | pGL3-basic vector inserted with ZIP10 promoter P2 carrying mutations in both MRE2′ and MRE3′ sites |

| pGL3-P2mall | pGL3-basic vector inserted with ZIP10 promoter P2 carrying mutations in all three MRE′ sites |

UTR, untranslated region; MRE, metal-response element.

The pGL3 containing P2 derivatives were created using site-directed mutagenesis. The oligonucleotides used to generate mutations in each MRE site are listed in Table 3. The individual MRE mutations (P2M1, P2M2, and P2M3) were generated using pGL3-P2 as template DNA, and the combination MRE mutations (P2M12, P2M23, P2M13, and P2Mall) were generated with mutated plasmids as template DNA. Presence of the mutations and integrity of promoter fragments was confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Table 3.

Sequence of primers used in site-directed mutagenesis

| Target | Forward (5′→3′) | Reverse (5′→3′) |

|---|---|---|

| MRE1′ | GGCAATATATTCCTTTGGTTTcatACTCTACTGCACATCAATCTC | GAGATTGATGTGCAGTAGAGTatcAAACCAAAGGAATATATTGCC |

| MRE2′ | CATTTTTACAGGCTGGAGCatgcGCTGTCGTAAGTACTGCTAAC | GTTAGCAGTACTTACGACAGCgcatGCTCCAGCCTGTAAAAATG |

| MRE3′ | GCAGGATTATCTTCATACAGTCgcatCTCCTGCCCCATCC | GGATGGGGCAGGAGatgcGACTGTATGAAGATAATCCTGC |

*Bases that are lower case bold are designed point mutations for the underlined MRE sites.

Cell culture, transfection, and luciferase assay.

HepG2 cells were routinely grown in minimum essential medium Eagle (Sigma) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 100 units/ml penicillin-streptomycin, and 1% MEM nonessential amino acid in a 37°C humidified incubator with 5% CO2.

For luciferase assay, HepG2 cells were seeded on six-well plates and transfected with 1 μg pGL3 plasmid and 0.1 μg pRL-TK plasmid (Promega), as an internal control, using FuGene 6 reagent (Roche). After overnight incubation, the cell media were replaced by serum- and antibiotics-free medium and, 4 h later, replaced by serum-free medium with or without 100 μM ZnSO4. After 24 h incubation, cells were washed with PBS and lysed by 500 μl Passive Lysis Buffer (Promega) per well. Luciferase activities were measured with a Dual-Glo Luciferase Assay System (Promega) in a GloMax 20/20 Luminometry System (Promega) by following the manufacturer's protocol. The raw values of firefly luciferase were normalized to Renilla luciferase that transfected concurrently in all the assays to correct for differences in transfection efficiency. The promoter activity assays were measured in triplicate in each experiment and shown as fold change relative to pGL3-Basic under either condition. At least three sets of independent experiments were performed for each set of constructs.

ZIP10 protein expression and 65Zn2+ flux in X. laevis oocyte.

The full-length ZIP10 open reading frame (ORF) was amplified using a primer pair, 5′-CGGAATTCACCATGATGAGAG TTCACACACATACC-3′ and 5′-AGCGGATCCT AGAAGCCAAAATCGAGCAC-3′. After digestion with EcoRI and HindIII, the ZIP10 ORF was inserted into pSPT-18 plasmid (Roche) to generate pSPT-18-ZIP10, in which transcription of ZIP10 is under the control of the T7 promoter. The capped ZIP10 mRNA was synthesized by in vitro transcription using mMACHINE T7 Ultra kit (Ambion).

The zinc influx assay of ectopically expressed zebrafish ZIP10 in X. laevis oocytes was performed as described previously (41). A set of X. laevis oocytes at developmental stage IV were isolated and injected with ∼30 ng/oocyte of the capped ZIP10 mRNA or nuclease-free water. After incubation at 18°C for 72 h, 15 oocytes in each group were incubated in 500 μl of influx buffer (73 mM NaCl, 1 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM NaHCO3, and 15 mM HEPES, pH 7.0) containing 125 μM 65Zn2+ (2 μCi/ml, PerkinElmer, specific activity = 0.246 mCi/mg) at 18°C for 4 h. The oocytes were then washed thoroughly six times with ice-cold stop buffer (influx buffer supplemented with 100 μM ZnCl2 to displace surface-bound zinc) and dispersed into individual 0.5 ml tubes. The radioactivity of each oocyte was counted in an LKB1282 CompuGamma counter.

Statistical analysis.

One-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's honestly significant difference multiple-comparison test, was used to determine the significance of differences between experimental groups. Two-way ANOVA was applied to qPCR data across time points. The level of significance was set as P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Levels of MT2 mRNA and zinc in gill tissue.

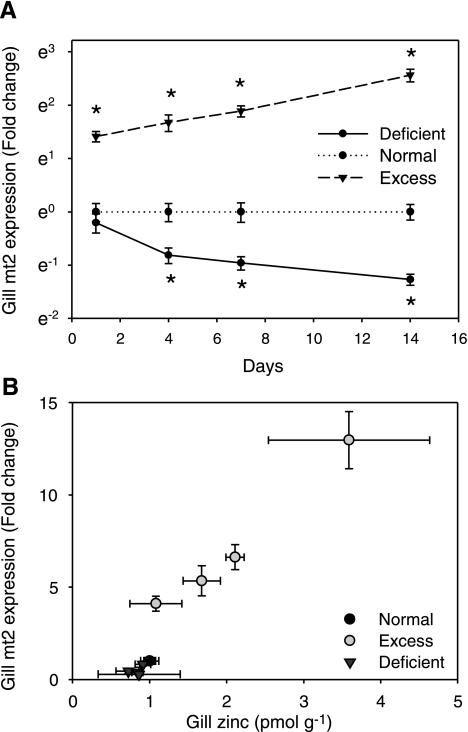

The efficiency of the zinc limiting and excess conditions in changing zinc status in zebrafish was gauged by measurements of zinc concentration and MT2 mRNA levels in fish gills. In the group treated with excess zinc in their water and diet, zinc was progressively accumulated in gills from 1 pmol per gram of tissue to 2.54 pmol at the end of 14 days. In contrast, fish treated by reduced zinc levels in the aquarium water and diet demonstrated persistently decreased levels of zinc in gills compared with the control and zinc excess groups (Fig. 1B). As expected, the MT2 mRNA level in gills was significantly elevated by treatment with increased zinc and progressively increased up to 12-fold, relative to the simultaneous control, after 14 days (P < 0.05); conversely, gills of zinc-deficient fish showed a significant decline of 2.3-fold in MT2 expression at 4 days (P < 0.05), but the degree of downregulation only reached to 3.6-fold by the end of 14 days (Fig. 1A). Overall, the MT2 expression in gills of all fish analyzed showed strong correlation with zinc concentration in gills (r2 = 0.91).

Fig. 1.

Zinc concentrations and relative mRNA expression of metallothionein (MT) 2 in gill tissue. A: relative levels of MT2 mRNA, as determined by qPCR, in response to treatment with zinc excess or deficiency over a 14-day period. Values are the average ± SD of measurements from 9 individual samples and normalized to the corresponding control group (=1.0) at each time point. *Values significantly different from those for control group at P < 0.05. B: scatter plot of the average ± SD values for MT2 expression vs. zinc concentrations in gills of fish treated with zinc-deficient, normal, or excess conditions for 1, 4, 7, or 14 days. Zinc concentrations in gills were determined by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Data for zinc are presented as pmol per gram of tissue, and error bars are the SD of measurements from 2−3 individual fish.

Expression of ZnT1, ZnT2, and ZnT5 transporters.

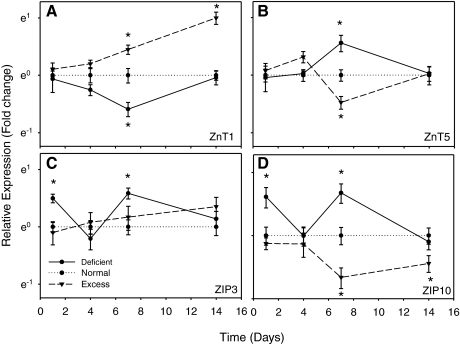

Similarly to MT2, the expression of ZnT1 was consistently induced by zinc excess, but only significantly after 7 days of treatment, reaching a moderate 2.7-fold after 14 days, while zinc deprivation resulted in significantly repressed mRNA levels at 7 days (Fig. 2A). Therefore, MT2 and ZnT1 may act in concert in fish gill to maintain intracellular free zinc at a safe level. Parallel analysis of the expression of ZnT2 revealed it to be a low-abundance transcript in gill, and its expression did not respond to changes in zinc status (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Influence of zinc excess and deficiency on mRNA levels of zinc transporters. The relative mRNA expression levels of ZnT1 (A), ZnT5 (B), ZIP3 (C), and ZIP10 (D) upon zinc excess and deficiency conditions were measured using real-time quantitative PCR. Values are the average of measurements from 9 individual fish, normalized to the time-paired control group (=1.0). *Values significantly different from those of control group at P < 0.05.

Another ZnT member, ZnT5, was also significantly expressed in gill. However, in contrast to the zinc regulation of ZnT1, the mRNA expression of ZnT5 was inhibited by zinc excess and upregulated by zinc deficiency at day 7 (Fig. 2B). This result is similar to that observed for the zinc importers ZIP3 and ZIP10 (see below). In human studies, a splice variant of ZnT5, expressed in the intestine, is localized on the enterocyte apical membrane and mediates dietary zinc uptake (8). We therefore propose that ZnT5 may play a similar role in the fish gill, facilitating zinc uptake from the water.

Expression of ZIP1, ZIP3, ZIP7, and ZIP10 transporters.

The expression of several members of ZIP family, ZIP1, ZIP3, ZIP7, and ZIP10 in response to zinc availability was also investigated using real-time PCR. The results indicate that neither ZIP1 nor ZIP7 responded significantly to changes of zinc status at mRNA level (data not shown). However, contrary to the regulation of MT2 and ZnT1, zinc deprivation increased the expression of both ZIP3 and ZIP10 after 1 and 7 days of zinc depletion, and the ZIP10 mRNA was also significantly downregulated by zinc excess (Fig. 2, C and D). Fish ZIP1 and ZIP3 are structurally similar and have previously been characterized as high- and low-affinity zinc importers, respectively (13, 40, 41). Here we investigated the function of zebrafish ZIP10 using the Xenopus oocyte expression system, and the result showed a 2.06 ± 0.39-fold (mean ± SD, n = 15) increase in 65Zn2+ influx compared with water-injected controls, which illustrated that zebrafish ZIP10 functions as a zinc importer. Therefore, the negative regulation of ZIP3 and ZIP10 by zinc excess can be explained in terms of zinc homeostasis as these transporters may act to protect cells from zinc overaccumulation by reducing zinc influx when the extracellular concentration of zinc is high.

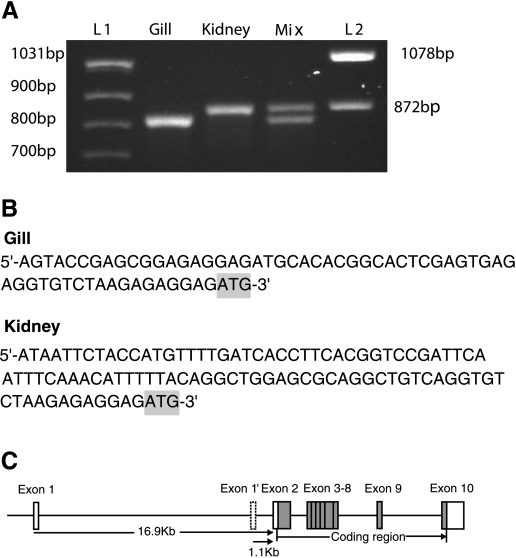

Identification of the TSSs for the ZIP10 gene.

We have demonstrated that the ZIP10 mRNA in zebrafish gills responded to zinc availability in a manner opposite to that of MT2 and ZnT1. In the zebrafish ZF4 cell line, the expression of ZIP10 was also repressed by 80% under zinc excess, confirming our observation in vivo (data not shown). We wished to investigate the transcriptional control of ZIP10 and, therefore, needed to determine the promoter region. To do this, we employed the 5′-RACE-PCR technique to identify the transcription start site for ZIP10 expressed in two tissues, gill and kidney. The 5′-RACE result revealed the existence of two distinct TSS for the ZIP10 gene in gill and kidney (Fig. 3). The 5′-sequence of the gill ZIP10 is located at 16,891 bp upstream of the exon 2 and that of the kidney ZIP10 located much closer to exon 2, at only 1,077 bp upstream (Fig. 3C). This suggested that two promoters may exist. Therefore, two promoter fragments, P1 and P2, containing up to 1.4 kb upstream of the corresponding TSS and the first exon, were amplified and linked upstream of a firefly luciferase reporter gene in the pGL3-basic plasmid (Fig. 4A). When expressed in HepG2 cells, both promoters drove strong luciferase activity, which implies that either ZIP10 transcript is initiated by a functional promoter (Fig. 5).

Fig. 3.

The distinct ZIP10 transcripts identified by 5′-rapid amplification of cDNA 5′-ends (RACE). A: ZIP10 5′-RACE fragments generated using gill and kidney cDNA templates. Fragments resolved include: L1 and L2 are DNA markers (lanes 1 & 5), 5′-RACE for gill ZIP10 (lane 3), 5′-RACE for kidney ZIP10 (lane 4), 5′-RACE for mixture of gill and kidney ZIP1. B: the sequences derived for 5′-untranslated region (UTR) of gill and kidney ZIP10 transcripts showing the start codon shaded in gray. C: schematic illustrating the structure of the alternative ZIP10 transcripts mapped onto its genomic loci. The exons are presented as boxes with coding regions as gray boxes. The alternative first exon for kidney ZIP10 is shown as Exon 1′.

Fig. 4.

Diagram of the structure of the zebrafish ZIP10 gene and alignment of the 5′-UTR sequence from different species. A: structure of the ZIP10 gene and the 2 potential alternative promoters, P1 and P2. Exons are presented as boxes with coding regions in gray. The potential promoter regions are magnified, along with their mutated derivatives used in reporter gene assays. The start site of exon 1 is designated as +1 and that of exon 2 as +1′. Each metal-response element (MRE) motif is marked as a black arrow, indicating the direction of the MRE sequence. The locations and sequences of MREs and their mutation are also given. B: sequence alignment by BlastZ of ZIP10 5′-UTR (Exon 1) in zebrafish, human, mouse, and fugu. *Complete homology between all species; the MRE sites are shaded.

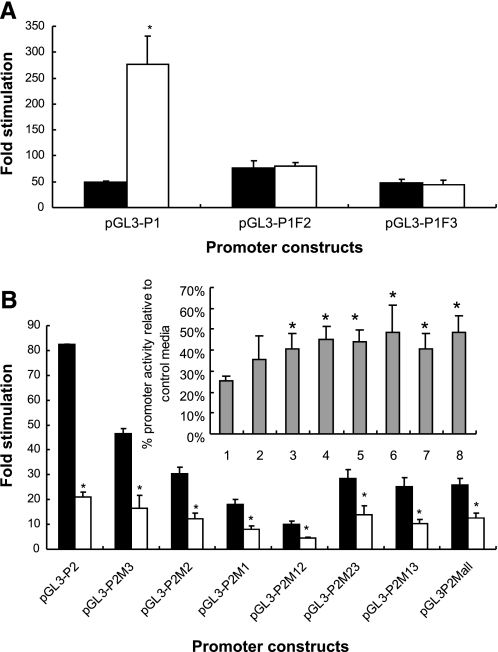

Fig. 5.

Relative luciferase activities of the 2 zebrafish ZIP10 promoter constructs and their derivatives. A: relative luciferase activities of the ZIP10 P1 promoter and its derivatives. B: relative luciferase activities of the ZIP10 P2 promoter and its derivatives. The promoter constructs are listed in Table 2 and illustrated in Fig. 4. The ZIP10 promoter activities were assayed in HepG2 cells incubated for 24 h in serum-free media with (white bars) or without (black bars) addition of 100 μM ZnSO4. The promoter activity assays were measured in triplicate in each experiment and are shown as fold stimulation with respect to pGL3-Basic under either condition. The values represent the average ± SD of at least 3 replicate experiments. The activity of P2 was 1.3-fold higher than that of P1 in the control condition (no zinc added). *Values significantly different between 100 μM zinc and control conditions at P < 0.05. The inset graph in B shows the activity of each promoter construct under zinc treatment as percentage of that under the control condition (no zinc added). *Values significantly different from that of the wild-type promoter at P < 0.05.

MRE mediated zinc regulation of ZIP10.

MTF-1 is the principal transcriptional factor related to zinc homeostasis, and it regulates the expression of MTs and ZnT1. To investigate the possible function of MTF1 in the downregulation of ZIP10 by zinc, we searched for MTF1 binding sites, MREs, within ZIP10 gene and characterized their role in transcriptional regulation using reporter gene assays.

Two MRE clusters were identified in the ZIP10 gene. The first cluster was found in promoter P1, with MRE1 located 20 bp upstream of the TSS (+1) and MRE2 at 27 bp downstream (within exon 1) (Fig. 4A). By aligning the ZIP10 sequence from several species, we discovered that the MRE2 site is well conserved among vertebrates, while in contrast the MRE1, located on the opposite strand, seems to be unique to zebrafish (Fig. 4B). The inductive potential of the wild-type P1 was ninefold in the presence of 100 μM Zn2+ (Fig. 5A), which is opposite to the effect of zinc on ZIP10 in the gill where this promoter was presumed to be active. The truncated promoters, P1F1 and P1F2, showed no response to elevated zinc, confirming that the two MREs were responsible for zinc-induced transcription. However, deletion of MRE2 or both MREs resulted in higher basal promoter activities compared with the unmanipulated promoter (Fig. 5A). The results suggest that the two MRE sites are important for zinc regulation of the P1 promoter, likely through MTF1/MRE interaction.

A second MRE cluster was identified associated with promoter P2, with MRE1′ situated at 89 bp upstream of the second TSS (+1′), MRE2′ at 64 bp downstream of the TSS (within exon 1′) and MRE3′ located further downstream within the first intron (Fig. 4A). Thus, like in P1, the MREs are straddling the TSS. Although the relatively large first intron, ∼16 kb in zebrafish, is also present in human, mouse, and rat, the precise arrangement of MREs is not conserved. However, MREs are present elsewhere in the first intron of ZIP10 from other vertebrates. In reporter gene assays with the P2 promoter, 100 μM Zn2+ strongly reduced its luciferase activity (Fig. 5B), similarly to the effect of zinc on ZIP10 expression in the gill. Interestingly, the P2 promoter is located 16 kb downstream of the TSS for ZIP10 in the gill and coinciding with the position of the TSS for ZIP10 in kidney. Mutation of the three MRE sites individually or in combination markedly reduced the basal promoter activity and decreased the potency of zinc to further repress expression (Fig. 5B). Of the three MREs, MRE3′ mutation alone had the least effect on both the basal promoter activity and the degree of zinc inhibition (P > 0.05), which suggests that the MRE1′ and MRE2′ sites play more significant roles in transcriptional regulation by zinc.

DISCUSSION

The fish gill is a route to acquire minerals directly from water and therefore provides a convenient model to study zinc absorption in vertebrates. Zinc uptake via gill from aquatic zinc sources is a complex process that requires zinc transporters operating across zinc concentrations ranging several orders of magnitude (13, 39–41). Clarification of the expression and regulation of zinc transporters in gills helps to elucidate their functions and regulatory mechanisms as they pertain to zinc homeostasis. In this study, we have utilized real-time PCR to show the role zinc plays in the regulation of mRNA levels of seven zinc transporters expressed in zebrafish gills. The expression of ZnT1 was upregulated by zinc excess and downregulated by zinc deficiency emulating, albeit at a lower amplitude, the impact of zinc on the expression of MT2 and in agreement with the established role of ZnT1 as a major zinc exporter in fish (1, 34) and mammals (36, 37). In contrast, zinc deprivation induced ZnT5, ZIP3, and ZIP10 mRNA accumulation, and zinc excess downregulated expression of ZnT5 and ZIP10 genes. This regulatory pattern would be consistent with functions of the corresponding proteins in zinc import at the apical membrane. Of all genes investigated, ZIP10 was the most consistently and markedly downregulated in response to elevated zinc. Zebrafish ZIP10 is orthologous to human SLC39A10 (13). The functionality of this gene in terms of zinc transporting ability has been little studied. It was recently shown that 65Zn uptake was reduced by 20% in the invasive (MDA-MB-231) and metastatic (MDA-MB-435S) breast cancer cell lines, when the expression of ZIP10 was knocked down using siRNA (24). A rat ZIP protein, historically assigned rZIP10, has been functionally characterized (25) but does not appear to be an ortholog to human or zebrafish slc39a10 and displays a higher sequence homology to human SLC39A4. We, therefore, utilized oocyte expression and 65Zn2+ transport assays to confirm that zebrafish ZIP10 truly functions as a zinc importer. The 5′-RACE and reporter gene assays allowed us to identify two alternative promoters driving transcription for two distinct ZIP10 transcripts in gill and kidney and demonstrate the possible involvement of MTF1-dependent zinc regulation in the promoters.

It is well known that induction of MTs, which bind zinc and several other metals with high affinity, is a universal mechanism to buffer intracellular zinc (17). In addition, the zinc exporter, ZnT1, acts as a safeguard to protect cells against zinc toxicity (36). The regulation of both MT2 and ZnT1 by zinc is mediated by MTF1 (18, 29). In zebrafish, the MT2 promoter contains seven putative MRE sites (3), whereas the ZnT1 promoter has only three. This may explain the observation in the present study that the response of MT2 to zinc excess was rapid (day 1) while ZnT1 mRNA levels were significantly increased only from day 7 onward and were moderate (up to 3-fold) compared with that of MT2 (up to 13-fold). We propose that the abundant MRE sites might make MT2 more sensitive to MTF1 activation, resulting in immediate buffering of small zinc variations; when incoming zinc is beyond the binding capability of MTs and MTF1 is highly activated, ZnT1 is induced and efficiently lowers total cellular zinc content by facilitating zinc efflux. Therefore, MTs and ZnT1 work in concert to provide maximum protection when cells exposed to high level of zinc. The expression and rapid regulation of MT2 and ZnT1 in gill are consistent with the strong ability of the zebrafish gill in maintaining zinc homeostasis even when the concentration of zinc in the water is very high. Conversely, when zinc supply is scarce, MTF1 may be inactivated resulting in less synthesis of both genes. However, our data suggest that this downregulation as a result of MTF1 inactivation is limited as only a maximum two- and threefold reduction was observed from ZnT1 and MT2, respectively. The resulting reduction in chelation by MT2 and basolateral extrusion of zinc by ZnT1 may be moderated by the concomitant upregulation of zinc importers, which would increase apical influx.

Another member of ZnT family, ZnT5, was also regulated at the level of mRNA abundance in response to changes in zinc availability. However, ZnT5 responded in the opposite direction to ZnT1. Thus, ZnT5 was induced by zinc deficiency and inhibited under zinc excess condition at day 7. This pattern of regulation was similar to that of the zinc importers, ZIP3 and ZIP10, in the present study. In mammals, ZnT5 is required for zinc uptake into Golgi-enriched vesicles while a splice variant is expressed at the brush-border membrane and was suggested to be involved in dietary zinc absorption (8, 9, 22, 26, 43). The expression of ZnT5 was reported to be induced by zinc deficiency in HeLa cells (10). However, its mRNA level increased twofold when Caco-2 cells were cultured in the medium with 100 μM Zn2+ but inhibited when zinc concentration increased to 200 μM (8, 9). Oral zinc supplement in human resulted in a reduced protein level of ZnT5 but not mRNA level in ileal mucosa. A more recent study showed that the two major ZnT5 splice variants appear to have distinct regulation, and this may contribute to its diverse regulation observed in the above studies (23). Based on the regulatory pattern observed in the present study and previous implication of ZnT5 in intestinal zinc uptake, we suggest that ZnT5 may contribute to apical zinc uptake into the gill cells. Further studies on its location and transcript variants are necessary to determine its function in zinc homeostasis in gill.

Regulation of members of the ZIP family by zinc is complex and involves control at transcriptional, posttranscriptional, translational, and posttranslational levels (11, 12, 32, 45). Some studies have provided evidence that zinc deficiency can increase abundance of mRNA for ZIP2 and ZIP4 in specific tissues (6, 11), but at least in the case of ZIP4 this has been attributed to an increased stability of ZIP4 mRNA during zinc depletion (45). In the present study, the gill levels of mRNA for both ZIP3 and ZIP10 were increased after 1 and 7 days of zinc depletion in water and diet. Moreover, ZIP10 mRNA showed substantial downregulation by zinc excess both in vivo and in vitro. In yeast, zinc-dependent transcriptional regulation of ZIP family is mediated by the transcription factor, ZAP1 (47–49). However, little is known about mechanisms involved in transcriptional regulation of vertebrate slc39 genes in response to changes in zinc status. Knockout of MTF1 in mouse liver cells was associated with upregulation of ZIP10 during zinc adequate conditions, indicating a possible tonic repression of ZIP10 expression by MTF1 (46). This is strongly supported by our observation in ZF4 cells that excess zinc decreased abundance of ZIP10 mRNA, and this effect was completely absent when treated with siRNA to MTF1 (G. P. Feeney, D. Zheng, C. Hogstrand, and P. Kille, unpublished observation). Thus, there is compelling evidence that MTF1 is a negative regulator of ZIP10 expression in both fish and mammals; the question is how this regulation is achieved.

In the present study, we provide evidence for the existence of two promoter regions separated by 16 kb in the ZIP10 gene. The two promoter regions, P1 and P2, correspond in their proximity to the TSS of the two alternative ZIP10 transcripts present in gill and kidney, respectively (Figs. 3 and 4). Furthermore, the two promoters provoke opposing responses to zinc excess in vitro. This led us to speculate that P1 could be negatively controlled by zinc. However, the regulatory mechanisms involved are more complex than originally thought. Contrary to the zinc inhibition of ZIP10 expression observed in the gill in vivo, P1 promoter was activated by zinc in reporter gene assays, and this response was dependent on an 88 bp DNA sequence that contained the proximal MRE motif of the pair of MREs flanking the TSS for the ZIP10 transcript found in gills. Interestingly, the P2 promoter, which corresponds to the ZIP10 transcript present in kidney, was negatively regulated in response to an increased zinc concentration. P2 contains three MRE motifs clustered around the TSS for the kidney ZIP10 transcript. These MREs overlap SP1 sites, which may be important for recruitment of the transcription initiation complex. Site-directed mutagenesis of the MREs in this region showed that they are essential for both basal and zinc-inhibition of promoter activity, implying that MTF1 may function as a repressor of P2. It is tempting to speculate that binding of MTF1 to these MREs may sterically hinder assembly of the transcription initiation complex and therefore inhibit transcription of ZIP10. However, it is entirely possible that other regions of the 2 kb P2 promoter are involved in the zinc-dependent transcriptional repression. It is not clear how MTF1 in P2 could impart negative responsiveness to zinc on the gill ZIP10 transcript, which starts 16 kb upstream. One possibility is that the DNA forms a loop bringing the MRE clusters in P1 and P2 in close proximity, allowing the MTF1 binding to these motifs to interact. Such a function would not be observed in reporter gene assays where the two promoters are physically separated. Although we did not investigate this in the present study, it can be speculated that the presence of two alternative promoters might enable ZIP10 to be regulated distinctively at different locations. Support for this hypothesis comes from a study where semiquantitative RT-PCR was used to create an indicative map of distribution of ZIP and ZnT transcripts among tissues in zebrafish treated with zinc-deficient, adequate, or excess conditions (13). Tissue-specific regulation of genes through promoter switching is not uncommon and adds another layer of complexity to define the proteome of any given cell (44).

The present study identified a set of genes important for zinc homeostasis in zebrafish gills and their regulation under both zinc excess and deficient conditions. For fish, zinc responsiveness of both zinc transporter families at the transcriptional level may be important for survival in waters with different zinc concentrations. We conclude that when zinc is in excess of requirements, ZnT1, along with MT2, plays a major role in preventing fish from zinc overaccumulation in the sensitive gill cells, and at the same time, expression of the zinc importers ZIP10 and ZnT5 is reduced to limit apical zinc entry into the gill cells. Intriguingly, after 14 days it is only the expression of ZnT1, ZIP10, and MT2 that remains altered, suggestive of their roles in maintaining sustained zinc homeostasis. Conversely, when zinc availability is suboptimal, ZnT1 and MT2 are downregulated while ZIP3, ZIP10, and ZnT5 are induced. Considering the similarity in zinc transporter complement and gene sequence between zebrafish and other vertebrates, our results may also help understanding the regulation of zinc transporters in mammals. The mechanistic analysis of ZIP10 transcription provides evidence of MRE functioning as transcription repressor elements, indirectly implicating a repressor function of MTF1. Our finding that ZIP10 has two promoter regions with opposing responsiveness to zinc suggests a high level of complexity in cellular zinc homeostasis that goes beyond the presence of multiple zinc transporters in various tissues.

GRANTS

This study was supported by Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council Grant S19512.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Dr. R. Handy, University of Plymouth, for producing and analyzing fish feeds, Drs. T. Kyriakou and M. Shayeghi, King's College London, for donating pGL3-basic and HepG2 cells and helping X. laevis oocyte expression assays, respectively.

Current address for D. Zheng: Div. of Clinical Developmental Sciences, St. George's Univ. of London, Cranmer Terrace, London SW17 0RE, UK.

Address for reprint requests and other correspondence: D. Zheng, Div. of Clinical Developmental Sciences, St. George's Univ. of London, Cranmer Terrace, London SW17 0RE, UK (e-mail: dzheng@sgul.ac.uk).

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Balesaria S, Hogstrand C. Identification, cloning and characterization of a plasma membrane zinc efflux transporter, TrZnT-1, from fugu pufferfish (Takifugu rubripes). Biochem J 394: 485–493, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beyersmann D, Haase H. Functions of zinc in signaling, proliferation and differentiation of mammalian cells. Biometals 14: 331–341, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen WY, John JA, Lin CH, Lin HF, Wu SC, Lin CH, Chang CY. Expression of metallothionein gene during embryonic and early larval development in zebrafish. Aquat Toxicol 69: 215–227, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chimienti F, Aouffen M, Favier A, Seve M. Zinc homeostasis-regulating proteins: new drug targets for triggering cell fate. Curr Drug Targets 4: 323–338, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coleman JE Zinc proteins: enzymes, storage proteins, transcription factors, and replication proteins. Annu Rev Biochem 61: 897–946, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cousins RJ, Blanchard RK, Popp MP, Liu L, Cao J, Moore JB, Green CL. A global view of the selectivity of zinc deprivation and excess on genes expressed in human THP-1 mononuclear cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 6952–6957, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cousins RJ, Liuzzi JP, Lichten LA. Mammalian zinc transport, trafficking, and signals. J Biol Chem 281: 24085–24089, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cragg RA, Christie GR, Phillips SR, Russi RM, Kury S, Mathers JC, Taylor PM, Ford D. A novel zinc-regulated human zinc transporter, hZTL1, is localized to the enterocyte apical membrane. J Biol Chem 277: 22789–22797, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cragg RA, Phillips SR, Piper JM, Varma JS, Campbell FC, Mathers JC, Ford D. Homeostatic regulation of zinc transporters in the human small intestine by dietary zinc supplementation. Gut 54: 469–478, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devergnas S, Chimienti F, Naud N, Pennequin A, Coquerel Y, Chantegrel J, Favier A, Seve M. Differential regulation of zinc efflux transporters ZnT-1, ZnT-5 and ZnT-7 gene expression by zinc levels: a real-time RT-PCR study. Biochem Pharmacol 68: 699–709, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dufner-Beattie J, Langmade SJ, Wang F, Eide D, Andrews GK. Structure, function, and regulation of a subfamily of mouse zinc transporter genes. J Biol Chem 278: 50142–50150, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dufner-Beattie J, Wang F, Kuo YM, Gitschier J, Eide D, Andrews GK. The acrodermatitis enteropathica gene ZIP4 encodes a tissue-specific, zinc-regulated zinc transporter in mice. J Biol Chem 278: 33474–33481, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feeney GP, Zheng D, Kille P, Hogstrand C. The phylogeny of teleost ZIP and ZnT zinc transporters and their tissue specific expression and response to zinc in zebrafish. Biochim Biophys Acta 1732: 88–95, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fosmire GJ Zinc toxicity. Am J Clin Nutr 51: 225–227, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fraker PJ, King LE, Laakko T, Vollmer TL. The dynamic link between the integrity of the immune system and zinc status. J Nutr 130: 1399S-1406S, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hambidge M Human zinc deficiency. J Nutr 130: 1344S–1349S, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamer DH Metallothionein. Annu Rev Biochem 55: 913–951, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heuchel R, Radtke F, Georgiev O, Stark G, Aguet M, Schaffner W. The transcription factor MTF-1 is essential for basal and heavy metal-induced metallothionein gene expression. EMBO J 13: 2870–2875, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hijova E Metallothioneins and zinc: their functions and interactions. Bratisl Lek Listy 105: 230–234, 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hogstrand C, Reid S, Wood C. Ca2+ versus Zn2+ transport in the gills of freshwater rainbow trout and the cost of adaptation to waterborne Zn2+. J Exp Biol 198: 337–348, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hogstrand C, Webb N, Wood CM. Covariation in regulation of affinity for branchial zinc and calcium uptake in freshwater rainbow trout. J Exp Biol 201: 1809–1815, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ishihara K, Yamazaki T, Ishida Y, Suzuki T, Oda K, Nagao M, Yamaguchi-Iwai Y, Kambe T. Zinc transport complexes contribute to the homeostatic maintenance of secretory pathway function in vertebrate cells. J Biol Chem 281: 17743–17750, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jackson KA, Helston RM, McKay JA, O'Neill ED, Mathers JC, Ford D. Splice variants of the human zinc transporter ZnT5 (SLC30A5) are differentially localised and regulated by zinc through transcription and mRNA stability. J Biol Chem 282: 10423–10431, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kagara N, Tanaka N, Noguchi S, Hirano T. Zinc and its transporter ZIP10 are involved in invasive behavior of breast cancer cells. Cancer Sci 98: 692–697, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaler P, Prasad R. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of novel zinc transporter rZip10 (Slc39a10) involved in zinc uptake across rat renal brush-border membrane. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F217–F229, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kambe T, Narita H, Yamaguchi-Iwai Y, Hirose J, Amano T, Sugiura N, Sasaki R, Mori K, Iwanaga T, Nagao M. Cloning and characterization of a novel mammalian zinc transporter, zinc transporter 5, abundantly expressed in pancreatic beta cells. J Biol Chem 277: 19049–19055, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kelleher SL, Lonnerdal B. Zinc transporters in the rat mammary gland respond to marginal zinc and vitamin A intakes during lactation. J Nutr 132: 3280–3285, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koizumi S, Suzuki K, Ogra Y, Yamada H, Otsuka F. Transcriptional activity and regulatory protein binding of metal-responsive elements of the human metallothionein-IIA gene. Eur J Biochem 259: 635–642, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Langmade SJ, Ravindra R, Daniels PJ, Andrews GK. The transcription factor MTF-1 mediates metal regulation of the mouse ZnT1 gene. J Biol Chem 275: 34803–34809, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liuzzi JP, Blanchard RK, Cousins RJ. Differential regulation of zinc transporter 1, 2, and 4 mRNA expression by dietary zinc in rats. J Nutr 131: 46–52, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liuzzi JP, Cousins RJ. Mammalian zinc transporters. Annu Rev Nutr 24: 151–172, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mao X, Kim BE, Wang F, Eide DJ, Petris MJ. A histidine-rich cluster mediates the ubiquitination and degradation of the human zinc transporter, hZIP4, and protects against zinc cytotoxicity. J Biol Chem 282: 6992–7000, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McMahon RJ, Cousins RJ. Regulation of the zinc transporter ZnT-1 by dietary zinc. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 4841–4846, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muylle F, Robbens J, De CW, Timmermans JP, Blust R. Cadmium and zinc induction of ZnT-1 mRNA in an established carp cell line. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol 143: 242–251, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olsson PE, Kille P. Functional comparison of the metal-regulated transcriptional control regions of metallothionein genes from cadmium-sensitive and tolerant fish species. Biochim Biophys Acta 1350: 325–334, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palmiter RD Protection against zinc toxicity by metallothionein and zinc transporter 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 4918–4923, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palmiter RD, Findley SD. Cloning and functional characterization of a mammalian zinc transporter that confers resistance to zinc. EMBO J 14: 639–649, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prasad AS Recognition of zinc-deficiency syndrome. Nutrition 17: 67–69, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qiu A, Hogstrand C. Functional characterisation and genomic analysis of an epithelial calcium channel (ECaC) from pufferfish, Fugu rubripes. Gene 342: 113–123, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qiu A, Hogstrand C. Functional expression of a low-affinity zinc uptake transporter (FrZIP2) from pufferfish (Takifugu rubripes) in MDCK cells. Biochem J 390: 777–786, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qiu A, Shayeghi M, Hogstrand C. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of a high-affinity zinc importer (DrZIP1) from zebrafish (Danio rerio). Biochem J 388: 745–754, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suh SW, Chen JW, Motamedi M, Bell B, Listiak K, Pons NF, Danscher G, Frederickson CJ. Evidence that synaptically-released zinc contributes to neuronal injury after traumatic brain injury. Brain Res 852: 268–273, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suzuki T, Ishihara K, Migaki H, Ishihara K, Nagao M, Yamaguchi-Iwai Y, Kambe T. Two different zinc transport complexes of cation diffusion facilitator proteins localized in the secretory pathway operate to activate alkaline phosphatases in vertebrate cells. J Biol Chem 280: 30956–30962, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Umenishi F, Verkman AS. Isolation and functional analysis of alternative promoters in the human aquaporin-4 water channel gene. Genomics 50: 373–377, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weaver BP, Dufner-Beattie J, Kambe T, Andrews GK. Novel zinc-responsive post-transcriptional mechanisms reciprocally regulate expression of the mouse Slc39a4 and Slc39a5 zinc transporters (Zip4 and Zip5). Biol Chem 388: 1301–1312, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wimmer U, Wang Y, Georgiev O, Schaffner W. Two major branches of anti-cadmium defense in the mouse: MTF-1/metallothioneins and glutathione. Nucleic Acids Res 33: 5715–5727, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao H, Butler E, Rodgers J, Spizzo T, Duesterhoeft S, Eide D. Regulation of zinc homeostasis in yeast by binding of the ZAP1 transcriptional activator to zinc-responsive promoter elements. J Biol Chem 273: 28713–28720, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhao H, Eide D. The yeast ZRT1 gene encodes the zinc transporter protein of a high-affinity uptake system induced by zinc limitation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 2454–2458, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhao H, Eide D. The ZRT2 gene encodes the low affinity zinc transporter in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem 271: 23203–23210, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]